Abstract

Objective

While the last three decades have seen numerous advances in the treatment of cervical cancer, it remains unclear if population level survival has improved. We examined relative survival, the ratio of survival in cervical cancer patients to matched controls over time.

Study Design

Patients with cervical cancer diagnosed from 1983–2009 and recorded in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database were examined. Survival models were adjusted for age, race, stage, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. Changes in stage-specific relative survival for patients with cervical cancer compared to the general population matched by age, race, and calendar year were examined over time.

Results

A total of 46,932 patients were identified.. For women with stage I tumors, the excess hazard ratio for women diagnosed in 2009 was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.86–0.95) compared to 2000, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.73–0.91) compared to 1990, and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.64–0.88) in comparison to 1983. For patients with stage III tumors, the excess hazard ratio’s for patients diagnosed in 2009 (relative to those diagnosed in 2000, 1990, and 1983) were 0.83 (95% CI, 0.80–0.87), 0.68 (95% CI, 0.62–0.75), and 0.59 (95% CI, 0.52–0.68). Similar trends in improved survival over time were noted for women with stage II tumors. There were no statistically significant improvements in relative survival over time for women with stage IV tumors.

Conclusion

Relative survival has improved over time for women with stage I–III cervical cancer, but has changed little for those with metastatic disease.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, survival, relative survival, trends, cervical carcinoma

Introduction

Cervical cancer remains a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Over the last three decades, a number of treatment advances for cervical cancer have been demonstrated in clinical trials. For women with early stage disease, newer surgical options are available and techniques for the delivery of radiation have improved. For advanced stage disease, improved survival for the use of combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy resulted in a paradigm shift for patients with stage II–IV disease in 1999.2–5 However, data describing how survival has changed over time remains limited.6–11

Quantifying changes in survival for cancer patients is of great importance as therapeutic advances that have shown efficacy in clinical trials are of little practical value if these treatments cannot be translated into clinical practice. However, examining secular trends in survival for cancer is methodologically challenging. First, as general medical care has improved over time, it is difficult to ascertain if improved survival for cancer patients is due to improved cancer treatment or due to greater longevity in the population as a whole.12 Second, measuring cancer-specific survival is inherently difficult as data from death certificates is often inaccurate and may not reflect cancer-associated mortality in patients who die from complications and the sequelae of cancer.13,14

To quantify secular trends in survival for cancer patients, relative survival, the ratio of the observed survival rate for cancer patients to the expected survival rate of matched patients from the general population has been described.15–17 Relative survival is a useful metric that controls for changes in survival in the general population and describes excess mortality in cancer patients over time.18,19 We performed a population-based analysis to examine secular changes in survival for women with cervical cancer treated in the United States from 1983 to 2009.

Methods

Data Source

Data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database was used for analysis.20 The SEER program comprehensively collects data on all newly diagnosed cancer patients from a number of registries located throughout the U.S. We included patients with invasive cervical cancer diagnosed between January 1983 and December 2009 with follow-up through December 31, 2011.

Data from the SEER 18 registries including San Francisco-Oakland, Connecticut, Detroit (metropolitan), Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah, Seattle (Puget Sound), Atlanta (metropolitan), San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Alaska Natives, rural Georgia, greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Greater Georgia. Louisiana cases diagnosed for July to December 2005 were excluded due to the impact of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on the registry’s ability to report data. Non-white and non-black women were excluded from the analyses since reliable population-level estimates of survival were required. Patients with unknown stage were excluded. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt.

Staging

Staging was based on the derived 6h edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging for patients diagnosed from 2004–2009, and the SEER modified third edition of AJCC staging for those women diagnosed from1988–2003.20 Prior to 1988, AJCC staging was not recorded in SEER. For those women diagnosed prior to 1988, we constructed AJCC staging through the use of 4-digit extent of disease (EOD) codes for patients treated in1983–1987.20

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis focused on overall survival defined as the time from diagnosis of cervical cancer until death from any cause. Relative survival, the ratio of the observed survival rate for cancer patients to the expected survival rate of matched patients from the general population was then estimated. Patients in the general population were matched to those with cervical cancer based on age, race and calendar year using the Ederer II method calculated using SEER*Stat software.21,22 Expected survival life tables were used to derive survival estimates for the controls. The expected life tables provide survival by age, race, and calendar year. Estimates were derived from interpolating the U.S. Decennial Life Tables from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) into individual years for the years 1970–2000 and from the U.S. Annual Life Tables from NCHS for the years 2001–2009. Although the effect of deaths due to cervical cancer is also included in the life tables, this does not affect the estimated survival of the populations.23,24 After matching, relative survival models were developed using annual intervals in the framework of generalized linear models with a Poisson error structure.25–27 When modeling relative survival, the model is an additive hazards model where the total hazard is the sum of the baseline hazard from the control and the excess hazard associated with a diagnosis of cervical cancer. The exponentiated parameter estimates are interpreted as excess hazard ratios.28

We fit separate models for patients with stage I, II, III, and IV neoplasms. Each of the models included age at the time of diagnosis, race, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. Age at diagnosis was defined as a categorical variable, <50 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, and ≥80 years and older, consistent with SEER reporting methodology. Year of diagnosis was included as a linear function. Time since diagnosis was a time-varying covariate updated in 1-year increments at the end of the yearly interval. Time since diagnosis was included as a piecewise linear function of year allowing changes in slope at 2, 5, and 10 years after the time of diagnosis to allow rapid change in excess hazards. Data on each covariate was updated with each new interval. Goodness of fit of the relative survival models was examined using deviance statistics.26

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 46,932 women with invasive cervical cancer diagnosed between 1983 and 2009 were identified. Within the cohort, 26,337 (56.1%) women had stage I tumors, 7091 (15.1%) stage II, 8090 (17.2%) stage III, and 5414 (11.5%) stage IV malignancies (Table 1). For all stages, women <50 years of age made up the greatest percentage of patients. Women with higher stage tumors were older, with 36.3% of stage IV patients <50 years of age compared to 68.4% for patients with stage I neoplasms. The percentage of black women increased with stage from 13.2% of patients with stage I tumors to 17.9% of stage III and 18.3% of stage IV patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with cervical cancer reported to the SEER registry, 1983–2009

| Characteristic | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| No. | 26,337 | (56.1) | 7,091 | (15.1) | 8,090 | (17.2) | 5,414 | (11.5) |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||

| <50 | 18,023 | (68.4) | 3,045 | (42.9) | 3,943 | (48.7) | 1,965 | (36.3) |

| 50–59 | 3,770 | (14.3) | 1,579 | (22.3) | 1,747 | (21.6) | 1,276 | (23.6) |

| 60–69 | 2,534 | (9.6) | 1,194 | (16.8) | 1,135 | (14.0) | 1,044 | (19.3) |

| 70–79 | 1,388 | (5.3) | 797 | (11.2) | 799 | (9.9) | 709 | (13.1) |

| ≥80 | 622 | (2.4) | 476 | (6.7) | 466 | (5.8) | 420 | (7.8) |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 3,485 | (13.2) | 1,262 | (17.8) | 1,448 | (17.9) | 990 | (18.3) |

| White | 22,852 | (86.8) | 5,829 | (82.2) | 6,642 | (82.1) | 4,424 | (81.7) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1983–1990 | 4,671 | (17.7) | 1,272 | (17.9) | 840 | (10.4) | 669 | (12.4) |

| 1991–2000 | 8,982 | (34.1) | 2,214 | (31.2) | 2,418 | (29.9) | 1,564 | (28.9) |

| 2001–2009 | 12,684 | (48.2) | 3,605 | (50.8) | 4,832 | (59.7) | 3,181 | (58.8) |

For all stages of disease, black women had higher excess hazard ratios than white women (Table 2). The excess hazard ratio for black women relative to white women was 1.70 (95% CI, 1.53–1.88) for stage I, 1.22 (95% CI, 1.11–1.34) for stage II, 1.31 (95% CI, 1.20–1.43) for stage III, and 1.23 (95% CI, 1.10–1.37) for stage IV tumors (P<0.0001). For all stages we noted reductions in excess mortality over time. For women with stage I tumors (HR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.98–1.00), the excess hazard ratio for women diagnosed in 2009 was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.86–0.95) compared to those diagnosed in 2000, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.73–0.91) compared to women diagnosed in 1990, and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.64–0.88) in comparison to patients diagnosed in 1983.

Table 2.

Stage-specific excess hazard ratios for death among patients diagnosed with cervical cancer

| Characteristic | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excess HR | P-value | Excess HR | P -value | Excess HR | P -value | Excess HR | P -value | |

| Black, relative to white | 1.70 (1.53–1.88) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.11–1.34) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.20–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.10–1.37) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||

| <50, relative to 50–59 | 0.54 (0.49–0.61) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) | 0.88 | 0.74 (0.68–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.007 |

| 60–69, relative to 50–59 | 1.27 (1.09–1.48) | 0.002 | 1.03 (0.91–1.17) | 0.67 | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 0.48 | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 0.12 |

| 70–79, relative to 50–59 | 1.42 (1.16–1.75) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.10–1.47) | 0.001 | 1.40 (1.23–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.16–1.55) | <0.001 |

| ≥80, relative to 50–59 | 2.65 (2.00–3.51) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.42–2.11) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.31–1.88) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.11–1.66) | 0.003 |

| Year of diagnosis † | ||||||||

| 2009, relative to 2005 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.90–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.24 |

| 2009, relative to 2000 | 0.91 (0.86–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.80–0.87) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.91–1.02) | 0.24 |

| 2009, relative to 1995 | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.68–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.70–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 0.24 |

| 2009, relative to 1990 | 0.81 (0.73–0.91) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.59–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.62–0.75) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.83–1.05) | 0.24 |

| 2009, relative to 1983 | 0.75 (0.64–0.88) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.49–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.52–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.77–1.07) | 0.24 |

| Time since diagnosisⱡ | ||||||||

| 1 year | 3.56 (3.20–3.97) | <0.001 | 3.39 (3.13–3.68) | <0.001 | 2.67 (2.52–2.82) | <0.001 | 2.60 (2.45–2.76) | <0.001 |

| 5 years | 4.32 (3.46–5.38) | <0.001 | 3.00 (2.52–3.57) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.08–1.44) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | <0.001 |

| 10 years | 2.49 (1.93–3.22) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.35–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.13–0.41) | <0.001 |

Estimates are based on models that adjust for race, age, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis.

P-values for year of diagnosis are the same since year of diagnosis is included as continuous.

P -values for time since diagnosis are for changes in slope at 2, 5, and 10 years after the time of diagnosis.

Similar trends were noted for women with both stage II and III tumors; there was a consistent decline in the excess hazard of death over time: stage II (HR=0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.98), stage III (HR=0.98; 95% CI, 0.98–0.99). For patients with stage III tumors, this translated to an excess hazard ratio of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.80–0.87) for patients diagnosed in 2009 relative to 2000 and 0.59 (95% CI, 0.52–0.68) relative to women diagnosed in 1983. We noted modest reductions in excess mortality over time, although these reductions did not reach statistical significance for women with stage IV neoplasms (HR=1.00; 95% CI, 0.99–1.00).

Table 3 displays the cumulative relative survival over time stratified by age and years since diagnosis. For most age groups, we noted that the decrease in relative survival was more pronounced over time. These absolute reductions in relative survival were greater for women with more advanced stage tumors. For example, among women <50 years of age with stage I tumors, relative survival was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.96–0.99) at 1 year and decreased to 0.93 (95% CI, 0.89–0.95) at 10 years. The corresponding relative survival values for women <50 years of age with stage IV neoplasms were 0.43 (95% CI, 0.22–0.62) at 1 year and 0.05 (95% CI, 0–0.20) at 10 years.

Table 3.

Cumulative relative survival for white women diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1990

| Time | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Observed Survival | Relative Survival | Observed Survival | Relative Survival | Observed Survival | Relative Survival | Observed Survival | Relative Survival | |

| Diagnosed at age <50 years | ||||||||

| Years since Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.91 (0.80–0.96) | 0.91 (0.80–0.96) | 0.81 (0.68–0.89) | 0.81 (0.68–0.89) | 0.43 (0.22–0.62) | 0.43 (0.22–0.62) |

| 5 | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 0.60 (0.46–0.71) | 0.60 (0.46–0.72) | 0.53 (0.39–0.65) | 0.53 (0.39–0.65) | 0.14 (0.04–0.32) | 0.14 (0.04–0.32) |

| 10 | 0.92 (0.88–0.94) | 0.93 (0.89–0.95) | 0.50 (0.37–0.63) | 0.51 (0.37–0.64) | 0.42 (0.29–0.54) | 0.43 (0.30–0.55) | 0.05 (0.00–0.20) | 0.05 (0.00–0.20) |

| Diagnosed at age 50–59 years | ||||||||

| Years since Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 (− †) | 1.00* (− †) | 0.87 (0.65–0.96) | 0.87 (0.65–0.96) | 0.73 (0.49–0.87) | 0.73 (0.49–0.87) | 0.40 (0.12–0.67) | 0.40 (0.12–0.67) |

| 5 | 0.89 (0.80–0.94) | 0.92 (0.81–0.97) | 0.61 (0.38–0.77) | 0.63 (0.39–0.79) | 0.32 (0.14–0.51) | 0.33 (0.15–0.52) | 0.30 (0.07–0.58) | 0.30 (0.07–0.59) |

| 10 | 0.78 (0.67–0.86) | 0.85 (0.71–0.92) | 0.39 (0.20–0.58) | 0.42 (0.21–0.62) | 0.14 (0.03–0.31) | 0.15 (0.04–0.33) | 0.10 (0.01–0.36) | 0.11 (0.01–0.37) |

| Diagnosed at age 60–69 years | ||||||||

| Years since Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.93 (0.84–0.98) | 0.95 (0.83–0.98) | 0.80 (0.50–0.93) | 0.81 (0.50–0.94) | 0.57 (0.34–0.75) | 0.58 (0.34–0.76) | 0.44 (0.22–0.65) | 0.45 (0.22–0.66) |

| 5 | 0.85 (0.74–0.92) | 0.90 (0.75–0.96) | 0.33 (0.12–0.56) | 0.35 (0.13–0.59) | 0.29 (0.12–0.48) | 0.31 (0.12–0.52) | 0.06 (0.00–0.22) | 0.06 (0.00–0.24) |

| 10 | 0.65 (0.52–0.76) | 0.79 (0.61–0.89) | 0.27 (0.08–0.50) | 0.30 (0.09–0.55) | 0.19 (0.06–0.38) | 0.23 (0.07–0.45) | 0.06 (0.00–0.22) | 0.06 (0.00–0.24) |

| Diagnosed at age 70–79 years | ||||||||

| Years since Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.00 (− †) | 1.00* (− †) | 0.89 (0.62–0.97) | 0.92 (0.56–0.99) | 0.53 (0.18–0.79) | 0.55 (0.18–0.81) | 0.07 (0.01–0.28) | 0.07 (0.01–0.28) |

| 5 | 0.83 (0.60–0.93) | 0.96 (0.11–1.00) | 0.22 (0.07–0.43) | 0.27 (0.08–0.51) | 0.27 (0.04–0.58) | 0.28 (0.04–0.61) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) |

| 10 | 0.52 (0.31–0.70) | 0.86 (0.15–0.99) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.13 (0.01–0.44) | 0.21 (0.01–0.61) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) |

| Diagnosed at age 80+ years | ||||||||

| Years since Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 1 | 0.90 (0.47–0.99) | 1.00* (− †) | 0.90 (0.45–0.98) | 0.96 (0.00–1.00) | 0.67 (0.28–0.88) | 0.71 (0.27–0.92) | 0.33 (0.05–0.68) | 0.37 (0.05–0.73) |

| 5 | 0.50 (0.18–0.75) | 0.82 (0.01–0.99) | 0.34 (0.08–0.63) | 0.52 (0.07–0.85) | 0.11 (0.01–0.39) | 0.13 (0.01–0.43) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) |

| 10 | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.11 (0.01–0.39) | 0.25 (0.01–0.69) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) | 0.00 (− †) |

The cumulative relative survival is over 1.00 and has been adjusted.

The statistic could not be calculated.

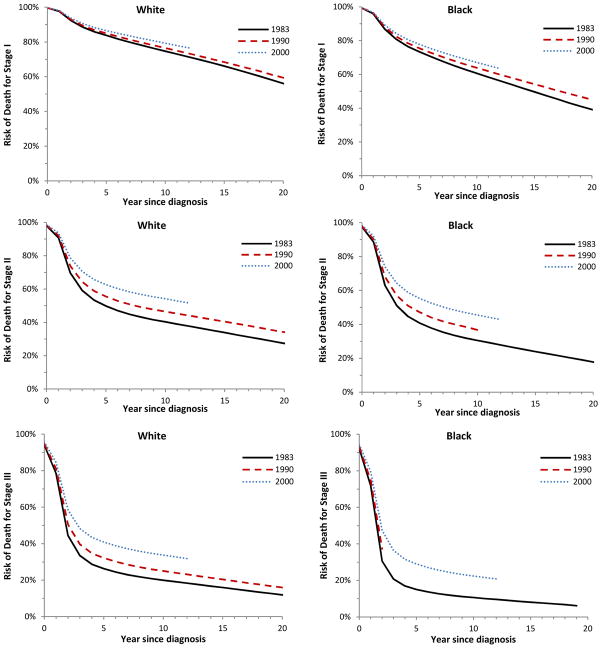

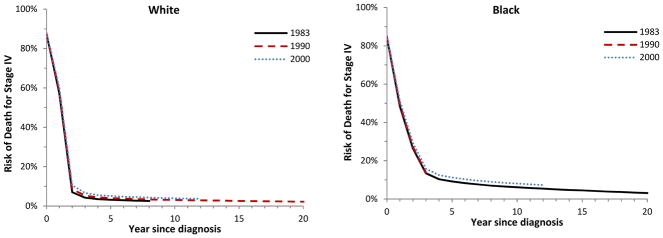

Figure 1 depicts cumulative relative survival stratified by stage, year of diagnosis, and race. For both black and white women, there was an improvement in relative survival over time. The improved survival was most pronounced for patients with stage II and III tumors.

Figure 1.

Cumulative relative survival among women aged 50 to 59 years diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1983 (solid lines), 1990 (dashed lines) and 2000 (dotted lines), based on models that adjust for age, race, year of diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. Stage I white (P=0.0007), black (P=0.0006); stage II white (P<0.0001), black (P<0.0001); stage III white (P<0.0001), black (P=0.0002); stage IV white (P=0.0041), black (P=0.0003).

Comment

Our findings suggest that survival has improved over time for women with early-stage and locally advanced cervical cancer. The most pronounced improvement in survival was noted for women with stage II–III tumors, while there have been no statistically significant improvements in survival for women with metastatic (stage IV) cervical cancer since 1983. For all stages of disease, the risk of death is greater for black than white women.

Prior work has suggested that survival for cervical cancer has increased over time.6,7,9–11,29,30 Population-based data from Canada noted that the relative survival of patients with cervical cancer diagnosed from 2005–2007 was 2.2% higher than women diagnosed in 1992–1994. However, the improvements in relative survival for cervical cancer lagged behind survival gains for other cancers including prostate, liver, colorectal, and kidney cancer which all registered 8–10% increases in relative survival over the same time period.6 An analysis of relative survival in Sweden from the 1960’s to 1984 explored the impact of the introduction of cytologic screening on cervical cancer survival. The authors noted improved relative survival in women less than 50 years of age with the most impressive gains in the youngest women.11 We noted that relative survival increased for all stages of cervical cancer. The most pronounced improvement in survival was for women with stage II and III neoplasms.

For early-stage cervical cancer, treatment relies on either radical surgery or primary radiotherapy. A randomized controlled trial comparing radical hysterectomy versus radiation for women with stage IB–IIA tumor noted equivalent survival.31 For these patients, treatment allocation is based on patient preference and potential toxicity.32 For patients with microinvasive cervical cancer, prognosis is excellent.33 We noted a consistent improvement in outcomes for women with stage I cervical cancer over time. For women diagnosed in 2009, survival was nearly 10% greater than for patients diagnosed in 2000 and 25% higher than for those treated in 1983.

The most substantial gains in relative survival were noted for patients with stage II–III cervical tumors. The paradigm for the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer changed in the late 1990’s when a series of reports noted improved survival in women treated with combination chemotherapy and radiation as opposed to radiation alone.2–5 These studies led to a clinical alert from the National Cancer Institute recommending the incorporation of radiation-sensitizing chemotherapy into the treatment of patients with advanced stage disease.34 For patients with stage II–III tumors treated in 2009, relative survival was improved by 30–35% compared to women in 1990 and by nearly 40–45% over those diagnosed in the early-1980s.

Despite improvements in survival for primary treatments for cervical cancer, outcomes for women with recurrent disease remain poor.35–38 For women with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer, treatment generally consists of platinum-based chemotherapy. A recent phase III trial by the Gynecologic Oncology Group demonstrated that the addition of bevacizumab to combination chemotherapy significantly improved survival.37 There has also been great interest in the prevention of cervical cancer, and, a number of prophylactic vaccines directed against human papillomavirus (HPV) are now available.39–42 In addition to prevention, there is a clear need for therapeutic advances for women with recurrent cervical cancer.

We acknowledge a number of important limitations. First, although cervical cancer is staged clinically, the increased use of advanced imaging modalities over time may have altered treatment strategies. While imaging findings should not have altered stage or led to “stage migration” given the way cervical cancer is staged, findings from imaging studies undoubtedly altered treatment patterns and it is difficult to determine how this may have influenced survival. Second, as the staging of cervical cancer changed over time, we used historic extent of disease codes to classify patients based on current staging nomenclature. We cannot exclude the possibility that a small number of patients were misclassified.15 Third, the number of registries participating in the SEER program increased over time. We performed a series of sensitivity analyses in which the cohort from the original 9 registries were compared to all patients and our findings were largely unchanged. Fourth, although the analysis was stratified by stage, the occurrence of intermediate risk factors may have changed over time. Lastly, using administrative data we are unable to account for individual preferences of patients and caregivers that influenced treatment allocation and outcomes.

Despite these limitations, these data provide important estimates of how survival has changed over time for women with cervical cancer. Survival has improved for women with stage I–III tumors suggesting that therapeutic advances demonstrated in clinical trials have had a meaningful impact on practice. Novel therapeutic approaches for metastatic cervical cancer are clearly needed, as there has been little change in survival over the last 25 years.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121-01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01 CA166084) are recipients of grants and Dr. Tergas is the recipient of a fellowship (NCI R25 CA094061-11) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1137–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1154–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1144–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitney CW, Sause W, Bundy BN, et al. Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation therapy in stage IIB–IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1339–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachuri L, De P, Ellison LF, Semenciw R. Cancer incidence, mortality and survival trends in Canada, 1970–2007. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2013;33:69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen T, Jansen L, Gondos A, et al. Survival of cervical cancer patients in Germany in the early 21st century: a period analysis by age, histology, and stage. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:915–21. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.708105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhtar-Danesh N, Elit L, Lytwyn A. Temporal trends in the relative survival among patients diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Canada 1992–2005: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:192–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klint A, Tryggvadottir L, Bray F, et al. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with cancer in female genital organs in the Nordic countries 1964–2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:632–43. doi: 10.3109/02841861003691945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhtar-Danesh N, Elit L, Lytwyn A. Temporal trends in the relative survival among women with cervical cancer in Canada: a population-based study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22:1208–13. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318263f014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adami HO, Ponten J, Sparen P, Bergstrom R, Gustafsson L, Friberg LG. Survival trend after invasive cervical cancer diagnosis in Sweden before and after cytologic screening. 1960–1984. Cancer. 1994;73:140–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940101)73:1<140::aid-cncr2820730124>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed October 13, 2014];Life Expectancy, United States of America. at https://www.google.com/webhp?sourceid=chrome-instant&rlz=1C5ACMJ_enUS518US558&ion=1&espv=2&ie=UTF-8-q=life%20expectancy%20in%20the%20united%20states.

- 13.Yin D, Morris CR, Bates JH, German RR. Effect of misclassified underlying cause of death on survival estimates of colon and rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1130–3. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Percy C, Stanek E, 3rd, Gloeckler L. Accuracy of cancer death certificates and its effect on cancer mortality statistics. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:242–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter CM, Johnson EA, Feuer EJ, Knudsen AB, Kuntz KM, Schrag D. Secular trends in colon and rectal cancer relative survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1806–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinchliffe SR, Rutherford MJ, Crowther MJ, Nelson CP, Lambert PC. Should relative survival be used with lung cancer data? Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1854–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Ngo L, Li D, Silliman RA, McCarthy EP. Causes of death and relative survival of older women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1570–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henson DE, Ries LA. On the estimation of survival. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:2–6. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamel JW, Vogel RL. Non-parametric comparison of relative versus cause-specific survival in Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) programme breast cancer patients. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10:339–52. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed July 28, 2014];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2013 Sub (1973–2011 varying) - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2012 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch. released April 2014 (updated 5/7/2014), based on the November 2013 submission. at http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 21.Ederer F, Heise H. Technical, End Results Evaluation Section. National Cancer Institute; 1959. Instructions to Ibm 650 Programmers in Processing Survival Computations. [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed July 28, 2014];Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software version 8.1.5. at http://www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat.

- 23.Ederer F, Axtell LM, Cutler SJ. The relative survival rate: a statistical methodology. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1961;6:101–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esteve J, Benhamou E, Raymond L. Descriptive epidemiology. IV. IARC Sci Publ; 1994. Statistical methods in cancer research; pp. 1–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed August 13, 2014];Estimating and modeling relative survival using SAS. at http://www.pauldickman.com/survival/sas/relative_survival_using_sas.pdf.

- 26.Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23:51–64. doi: 10.1002/sim.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakulinen T, Tenkanen L. Regression analysis of relative survival rates. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1987;36:309–17. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suissa S. Relative excess risk: an alternative measure of comparative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:279–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bielska-Lasota M, Inghelmann R, van de Poll-Franse L, Capocaccia R. Trends in cervical cancer survival in Europe, 1983–1994: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:609–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Hakulinen T, et al. Variations in survival for invasive cervical cancer among European women, 1978–89. EUROCARE Working Group. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:575–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1008959211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A, et al. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib–IIa cervical cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:535–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George EM, Tergas AI, Ananth CV, et al. Safety and tolerance of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in the elderly. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spoozak L, Lewin SN, Burke WM, et al. Microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:80, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NCI Issues Clinical Announcement on Cervical Cancer. [Accessed October, 12, 2014];Chemotherapy Plus Radiation Improves Survival. at http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/feb99/nci-22.htm.

- 35.Long HJ, 3rd, Bundy BN, Grendys EC, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4626–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore DH, Blessing JA, McQuellon RP, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin with or without paclitaxel in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3113–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, 3rd, et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:734–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monk BJ, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, et al. Phase III trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4649–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romanowski B, de Borba PC, Naud PS, et al. Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial up to 6. 4 years. Lancet. 2009;374:1975–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munoz N, Manalastas R, Jr, Pitisuttithum P, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in women aged 24–45 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1949–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]