Abstract

Introduction

The relationship between persistent postoperative cognitive decline and the more common acute variety remains unknown; using data acquired in preclinical studies of postoperative cognitive decline we attempted to characterize this relationship.

Methods

Low capacity runner (LCR) rats, which have all the features of the metabolic syndrome, were compared postoperatively with high capacity runner (HCR) rats for memory, assessed by trace fear conditioning (TFC) on the 7th postoperative day, and learning and memory (probe trial [PT]) assessed by the Morris water-maze (MWM) at three months postoperatively. Rate of learning (AL) data from the MWM test, were estimated by non-linear mixed effects modeling. The individual rat's TFC result at postoperative day (POD) 7 was correlated with its AL and PT from the MWM data sets at postoperative day POD 90.

Results

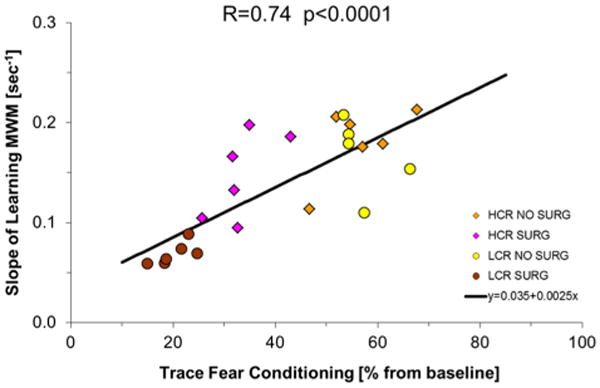

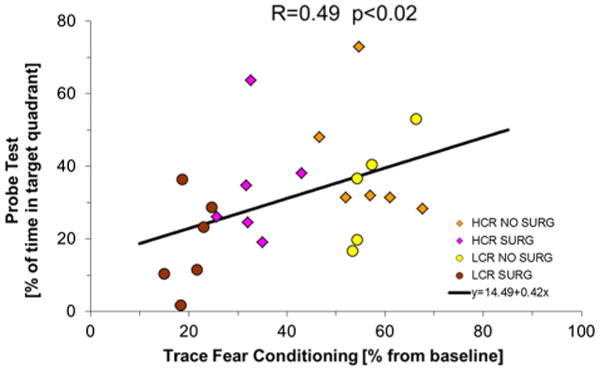

A single exponential decay model best described AL in the MWM with LCR and surgery (LCR–SURG) being the only significant covariates; first order AL rate constant was 0.07 s−1 in LCR–SURG and 0.16 s−1 in the remaining groups (p<0.05). TFC was significantly correlated with both AL (R = 0.74; p < 0.0001) and PT (R = 0.49; p < 0.01).

Conclusion

Severity of memory decline at 1 week after surgery presaged long-lasting deteriorations in learning and memory.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, Postsurgical, Acute, Long term, Memory, Learning, Metabolic syndrome

1. Introduction

Aseptic surgical trauma generates a cascade of inflammatory responses designed to repair the organism. Counteracting the inflammation are homeostatic feedback mechanisms, both neural and humoral, designed to restore the organism to its pre-injury state. Under normal conditions, initiation and resolution of inflammation are appropriately balanced to facilitate wound healing while minimizing damage to the body from exaggerated or persistent inflammation. One of the consequences of a perioperative imbalance between initiation and resolution of inflammation is enhancement and prolongation of cognitive decline. Failure to resolve postoperative inflammation in the setting of the metabolic syndrome (Su et al., 2012) is associated with an exaggerated and prolonged cognitive decline (Feng et al., 2013). The relationship between acute delirium and long term cognitive dysfunction has recently been explored for patients (both medical and surgical) in the intensive care unit; the longer the period of delirium the worse the global cognition and executive function at three and 12 months after discharge from the ICU (Pandharipande et al., 2013).

The study of the complex relationships between drug doses and drug effects has advanced significantly due to the use of mathematical approaches enabling the estimation of population models, integration of variability, and application of Bayesian methods to re-estimate individual responses from the population model and the data collected from each individual. Several examples in the anesthetic (Gambus and Troconiz, 2015) and non-anesthetic (Troconiz et al., 2012) (Sheiner, 1994; Soto et al., 2011) literature have shown the utility of these approaches; the use of the population approach for mathematical modeling extends beyond clinical pharmacology (Owen and Fiedler-Kelly, 2014; Pinheiro and Bates, 2000).

Establishing the nature of the relationship between acute and chronic changes of postoperative cognitive function is likely to provide insights into the mechanisms and processes responsible for cognitive alterations both early and late after surgical insult. Mathematical models can help by integrating all available information from the data, analyzing these contemporaneously, extracting the common pattern of behavior into a population model, and identifying possible sources of inter-individual variability (Mould and Upton, 2012).

To address the hypothesis that chronic cognitive consequences of surgery are directly related to acute decline of cognitive function, we used a population modeling approach to explore this relationship in a model of metabolic syndrome (“low capacity runner rats” (Koch and Britton, 2001)) in which cognitive decline was shown to be exaggerated acutely and to be persistent, chronically, in different postoperative cohorts (Feng et al., 2013).

2. Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and the protocol conformed to National Institute of Health guidelines. Animals were handled in strict accordance with good laboratory practice.

Cognitive function was assessed 1 week and 3 months after tibia surgery. Twenty four animals were included in the study and randomly assigned to the surgery or sham groups. Sample size was calculated according to our previous studies (Cibelli et al., 2010; Terrando et al., 2010). In each of the surgery and sham groups six animals were low capacity runners (LCR) and six were high capacity runners (HCR) as previously defined elsewhere (Koch and Britton, 2001). LCR animals have a tendency to minimal physical activity and a phenotype comparable to metabolic syndrome without the need to genetically modify the organism. All rats studied were between four and seven months at which age they are considered to be adult. One week after surgery the rats had the trace fear conditioning (TFC) test and three months after the surgical intervention the same animals had two different tests of cognitive function performed in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) paradigm.

2.1. Description of surgical procedure

Under general anesthetic with 2.1% isoflurane, rats underwent an open tibia fracture of the left hind paw with an intramedullary fixation under aseptic surgical conditions as previously described (Feng et al., 2013). Buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) was given subcutaneously to provide analgesia after induction of anesthesia and before skin incision. Sham rats were exposed to anesthesia and analgesia as above but no surgical procedure was performed.

2.2. Cognitive performance tests

TFC was performed seven days after surgery or sham procedure. Fear conditioning is used to assess learning and memory in rodents, which are trained to associate a conditional stimulus, such as a tone, with an aversive, unconditional stimulus, such as a foot-shock. Contextual freezing behavior is an indicator of aversive memory that is measured when subjects are re-exposed to the context, in this case placed in the same cage. The chamber or cage (Med Associates Inc., St Albans, VT) is 32 cm long, 25 cm wide and 25 cm high and is constructed of clear acrylic with a floor composed of 19 stainless steel bars, each 4 mm in diameter and spaced 16 mm on center that is connected to a shock delivery system (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). The chamber was wiped with a pine-scented cleaner (5% Pine Scented Disinfectant; Midland, Inc., Sweetwater, TN) before and after each session and training and assessment was performed in a room illuminated with overhead fluorescent bulbs with a ventilation fan providing background noise (65 db). During the training, rats were allowed to explore this context for 3 min after which they were presented with an auditory cue (75–80 dB, 5 kHz, conditional stimulus for 20 s). The unconditional stimulus, a 2 s foot shock (0.8 mAmp) was administered 20 s after termination of the auditory tone. Rats were removed from the chamber after an additional 30 s. Freezing, the absence of all movement except for respiration, is an innate defensive fear response in rodents and a reliable measure of learned fear that can be recalled when placed in the same context on a subsequent occasion.

MWM test was assessed three months after surgery. There were three sessions daily for every animal for ten days. During each session the time taken for the animal to find a hidden platform was measured. The MWM paradigm contains a platform (diameter, 10.3 cm) that was submerged in a circular pool (diameter, 180 cm; depth, 50 cm) filled with warm (24 °C) opaque water. Surrounding the pool were a set of remote visual cues. In the first trial of three training sessions, the platform was rendered visible from the surface by raising it one inch above the fluid surface and by marking its edge with bright yellow tape; between each session the platform was relocated.

The MWM test reflects the learning ability of the animal; latency should decrease daily until a plateau is reached (Shih et al., 2012).

The probe trial (PT) is a spatial memory test used to evaluate memory retention. For PT the erstwhile platform is removed from the tank where the training took place; PT was performed immediately after the last training session of the MWM test. During the PT, the proportion of time spent in the quadrant in which the platform previously resided (“target quadrant”), as well as each of the other quadrants, was determined for a 60-s interval. A Student t-test was used to compare the measurements of TFC between surgery and no surgery groups.

2.3. Mathematical modeling

Data from the MWM test were analyzed using a population approach based on nonlinear mixed effects modeling with the software NONMEM 7 and the First Order Conditional Estimates with the interaction option (Beal and Sheiner, 2006). Nonlinear mixed effects modeling allows the analysis of the data from all animals at the same time; no transformation of the data is required. From this analysis a common mathematical model of behavior is generated and the parameters defining it can be estimated. Thereafter, the effect of known covariate factors (surgery, metabolic syndrome) can be integrated into the model to explain the inter-individual differences. The statistical significance of the inclusion of such factors in the model is assessed and forms the basis for its inclusion in the final model.

Based on visual exploration of the collected data, the proposed initial model was:

| (1) |

where E refers to the time in seconds it would take the rat to reach the platform at any given day. A0 refers to the basal effect parameter which explains the time it would take the rat to find the platform in the MWM on the first occasion, and AL, the first order rate constant, indicates the speed of learning how to reach the platform at different times up to ten days after the initial test. “Time” is the independent variable expressing days after first MWM test. From the estimate of AL, the derived parameter t½AL can be calculated as:

| (2) |

where t1/2AL indicates the time to reduce E, defined in Eq. (1), by a half.

Inter-animal variability was included in the model for each parameter as:

| (3) |

where θi is the estimate of a certain parameter (A0 or AL) for the ith individual, θTV is the estimate in the typical individual, the representative individual of all those studied, and η represents the discrepancy between θi and θTV. The set of ηs forms a random variable assumed to be symmetrically distributed around zero with variance ω2. From the population model and given the individual data, individual estimates of either A0 or AL can be estimated allowing further comparisons on an individual basis.

Two different covariate factors were tested: the influence of surgery (SURG), and the presence of the LCR phenotype. In both cases the covariate factors were incorporated as an ordered categorical non-continuous factor in the model.

The decision to include a new parameter in the model was based on statistical criteria. NONMEM uses an objective function that approximately equals −2 Log Likelihood (−2LL) as a converging criterion. Inclusion of a new parameter in the model was considered, for a significance level p < 0.05, when the decrease in the minimum value of −2LL was greater than 3.84 units.

2.4. Correlations

From the population model of learning ability based on the results of the MWM test and using a Bayesian approach with the same software package NONMEM 7, it was possible to estimate the individual AL parameter for every animal studied. Individual values of TFC measured 7 days after surgery, expressed as percentage of baseline, were correlated to AL the individual first order rate constant of decay of the learning curve on the MWM test. TFC values were also correlated to the values of PT. The Spearman correlation test was used as a measure of correlation and its statistical significance was also calculated.

3. Results

Data from 23 rats were included in the analysis; one rat belonging to the “LCR no SURG” group died prior to collection of all the data; therefore data from this rat was not included in the analysis. The swimming speed, measured by the video tracking system, did not detect differences amongst the four groups; therefore, a potential confounder related to the fracture and healing processes did not affect assessment of cognition.

One measurement of TFC from every animal was collected on the seventh day after surgery. One measurement of PT per animal was recorded at the end of the ten days of training in the MWM. With regards to the MWM data, there were three measurements per day for each one of the 23 rats during a 10-day period starting three months after surgery. For building the model of learning abilities based on the results of the MWM test a total of 690 data points were used.

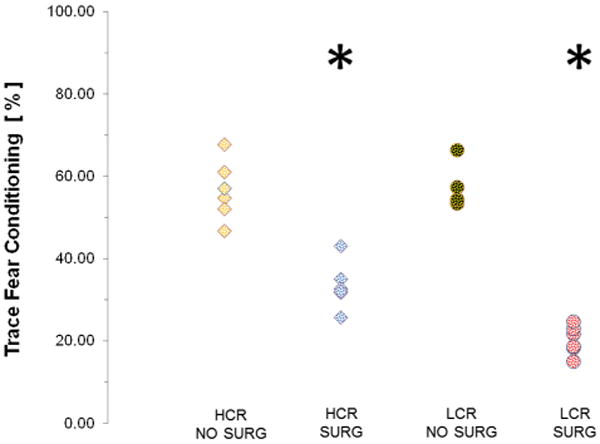

Fig. 1 shows the distribution of TFC measurements in the different subgroups of surgery, non-surgery, LCR and HCR. As can be seen TFC values were significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the animals undergoing surgery as compared to non-surgery.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of TFC values for every individual 1 week after surgery. The circles represent the individuals of the LCR group while the squares represent the HCR group. Mean (SD) are 20.2 (3.5), 57.1 (5.3), 33.3 (5.6), 56.5 (7.3) for the LCR surgery, LCR no surgery, HCR surgery and HCR no surgery respectively. Asterisk marks the significantly different behavior of the LCR and HCR surgery as compared to non-surgery subgroups.

3.1. Model selection, diagnosis and validation

The proposed model with a baseline level and single exponential term was sufficient to describe the decay in learning time for the rats for the ten days during which the animals were tested daily in the MWM (Table 1). The data also supported the inclusion of estimates of inter-animal variability for A0 and AL. Surgery and the LCR phenotype together were found to have significant effects on the AL parameter (p < 0.05) and provided a better description of the data and its inter-individual variability. The objective function at inclusion of AL-LCR,SURG was 29.56 units (p < 0.05); this decrease in the minimum value of −2LL exceeds the predefined change required by nearly 10-fold.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the initial and final models tested and their respective value of objective function. A decrease in 3.84 point in objective function is required to consider a statistically significant change for the addition of another parameter.

| Parameters | Objective function | |

|---|---|---|

| Base model | A0, AL, ω2A0, ω2AL | 10080.595 |

| LCR–SURG + variability | A0, AL, AL-LCR,SURG ω2A0, ω2AL | 10051.031 |

A0: baseline parameter.

AL: slope parameter.

AL-LCR,SURG: slope parameter in the group of low capacity runner animals undergoing surgery.

ω2A0: estimation of interindividual variability for A0 baseline parameter.

ω2AL: estimation of interindividual variability for AL, slope parameter.

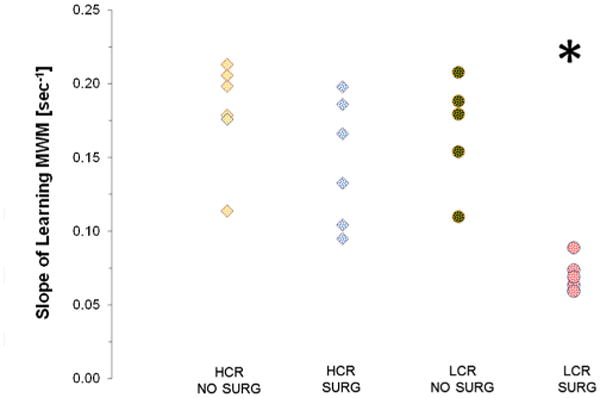

The combination of the LCR phenotype and surgery, statistically significant reduced AL, the first order rate constant of decay of the learning curve, yielding values of 0.07 (AL-LCR,SURG) vs 0.16 s−1. Transforming this value into t1/2AL results in a value of 9.83 s in the LCR–SURG group as compared to 4.31 s in the other groups; thus the LCR–SURG rats were more than two times slower in learning to find the platform in the MWM test. The estimates of the parameters of the final model as well as the estimates of inter-animal variability are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates of the selected model. Population estimate and Standard Error.

| Population estimate | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|

| A0 (s) | 59.80 | 2.87 |

| AL (s−1) | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| AL-LCR,SURG (s−1) | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Eta 1 (Variability A0) | 0.03 | |

| Eta 2 (Variability AL) | 0.09 |

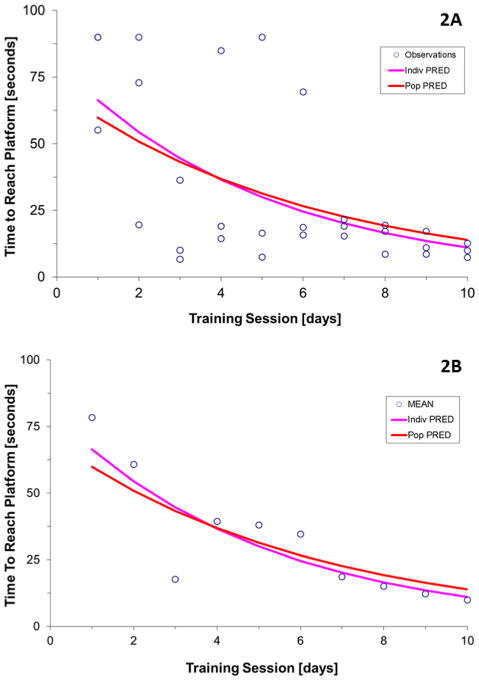

Nonlinear mixed effects modeling with NONMEM uses a Bayesian approach to estimate individual values of the parameters from the population estimate and the individual data. An individual animal exemplifies the population fit and the individual post hoc fit compared to the raw observations (30 data points) of every session (Fig. 2A) as well as to the average (10 data points) of each day's observations (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Population and individual fit of the model to the observations in one representative individual. The dots correspond to the individual observations in Fig. 2A and to the average of the three daily observations in Fig. 2B. The red line is the population prediction and the blue line is the estimation of the model based on Bayesian analysis (Bayesian post hoc individual fit) for this particular individual. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

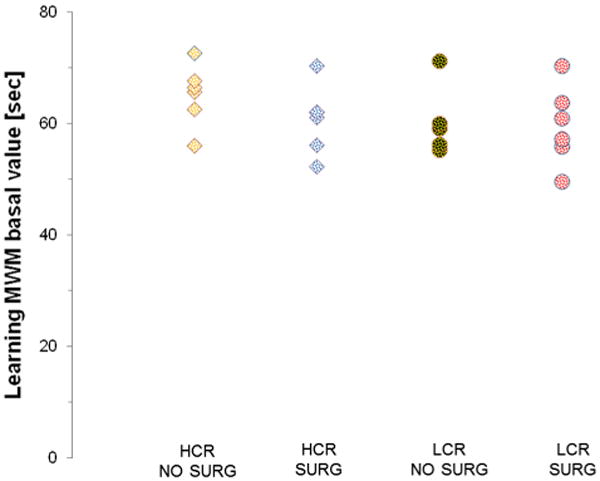

Fig. 3 shows the distribution of the estimates of A0, the basal time to reach the platform in the MWM test, for the animals of all four groups of rats. As can be appreciated from the distribution of the parameters, no difference in baseline performance was noted between the four groups.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of baseline parameter for every individual. Circles represent the individuals of the HCR phenotype while squares represent LCR.

Fig. 4 shows the distribution of the estimates of AL; the value is significantly smaller in the LCR–SURG group as compared to the other three groups.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of slope parameter for every individual. Circles represent the individuals of the HCR phenotype while squares represent LCR.

3.2. Correlation between acute and chronic changes

Fig. 5 shows the correlation between the change in TFC time expressed as percentage from baseline value in each animal, and its corresponding value of AL slope in the MWM tests. As can be observed there is a statistically significant positive correlation meaning that the alterations in TFC 1 week after surgery, predict performance in the MWM 3 months after surgery. The value of R was 0.74 (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Correlation between trace fear conditioning and learning. As can be seen there is a positive correlation with lower values of TFC associated to slow speed of learning. Correlation is performed with all values. Animals of different groups are represented by different symbols for clarity SURG 1 means tibial surgery SURG 0 sham surgery.

The correlation between TFC and memory expressed as the PT was also explored and is shown in Fig. 6. There was a positive (R: 0.49) and statistically significant (p < 0.02) correlation between these variables.

Fig. 6.

Correlation between trace fear conditioning and memory. As can be seen there is a positive correlation with lower values of TFC associated to low memory especially evident for LCR animals that underwent surgery. Correlation is performed with all values. Animals of different groups are represented by different symbols for clarity SURG 1 means tibial surgery SURG 0 sham surgery.

4. Discussion

When surgery is performed in rats with Metabolic Syndrome both acute and chronic forms of cognitive decline are worse (Figs. 1 and 4) and are highly correlated (Figs. 5 and 6). To explore this relation we have used a mathematical model that has been able to define the ability of the animals to learn, as a function of time, expressed as a single parameter, AL. The results demonstrate a significant correlation between cognitive function measured shortly after surgery, by TFC, and long term altered learning (Fig. 5) and memory (Fig. 6) by MWM. Therefore, an early sign of dysfunction, such as TFC performed seven days postoperatively may be expected to predict future cognitive behavior.

Surgery induces changes in TFC suggesting an acute alteration of cognitive function that is not obvious in the sham group irrespective of being LCR or HCR (Fig. 1). While HCR animals show a similar slope of learning 3 months after surgery than the non-surgery HCR or LCR, animals in the LCR and surgery continue to have altered cognitive function (Fig. 4). This long-lasting deterioration may be due to the persistence of inflammation due to a failure in the inflammation-resolving mechanisms that were noted soon after surgery (Su et al., 2013); in a different cohort, the white adipose tissue of LCR rats expressed a persistent hyperinflammatory state as long as five months postoperatively (Feng et al., 2013).

The mathematical model estimated AL, a first order rate constant that could be transformed in a “t1/2 of learning” (t1/2 AL), to represent how fast the animal is able to find the platform at each session of the MWM; as such AL represents a single parameter, reflecting the ability to learn and can be used to correlate cognitive decline measured acutely (POD 7) and chronically (POD 90). To the best of our knowledge no such an attempt to correlate acute vs long term postoperative changes have been done and it may have some clinical implications as recently demonstrated in patients discharged from medical and surgical critical care units (Pandharipande et al., 2013).

A strength of nonlinear mixed effects modeling to describe the learning process in the MWM paradigm lies in the ability to analyze data from all animals contemporaneously; in this manner the characteristics of each individual subject can contribute to the model because data are not pooled. For each animal the direct effect of individual factors like surgery versus sham or LCR versus HCR can be obtained; onto this “common” pattern are added contributions from other sources of explained and unexplained inter-individual variability. Furthermore, the individual parameters that define the mathematical model can be directly compared. Also, the correlations exposed by the model may provide insights into its underlying mechanisms.

The present study was not designed to assess the contribution of inflammatory changes to the correlation. Previous work from our group as well as from other investigators has demonstrated that surgery induces alterations in cognitive tests by changing circulating levels of HMGB1 (Vacas et al., 2013), TNF α (Terrando et al., 2010), IL-6, IL-1b (Cibelli et al., 2010), Bone Marrow derived Macrophages (Degos et al., 2013), that induces an inflammatory response in the hippocampus (Fidalgo et al., 2011). While, our studies do not directly address whether the relationship between acute and long term cognitive change is governed by neuroinflam-matory changes we have previously reported that the LCR animals exhibit a non-resolving pro-inflammatory phenotype (polarization of tissue macrophages to M1) as long as 5 months after the surgical intervention (Feng et al., 2013); when considered in the light of a similar lack of inflammation-resolution acutely after surgery (Su et al., 2012), it seems likely that the more pronounced neuroinflammation that obtain in the exaggerated acute cognitive decline continues to the chronic stages.

These results introduce a possible parallelism between animal and human responses after surgery that may be important not only as a diagnostic tool but also to understand pathogenesis and to develop treatments. It may be especially useful when combining mechanistic explanations linking behavioral changes to molecular and cellular alterations. An acute form of cognitive dysfunction such as delirium in humans postoperatively may be able to predict the future development of chronic cognitive decline in the form of delayed learning and altered memory as some authors have shown (Monk et al., 2008) and a possible link to neuroinflammation (Terrando et al., 2010).

A plausible hypothesis in the light of the current analysis and other reports (Feng et al., 2013; Su et al., 2012) would be to consider postoperative cognitive decline as a continuum, beginning acutely soon after surgery. The triggering event is surgery or aseptic trauma, and the pathogenesis may well be a disequilibrium between the appropriate trauma-induced inflammation and its resolution that is affected by factors such as metabolic syndrome and life-style choices like obesity. Given that acute and chronic postoperative decline are positively correlated (Figs. 5 and 6), strategies designed to minimize acute decline may pre-empt the onset of chronic postoperative decline.

To conclude we observed a high correlation between an acute form of cognitive decline after surgery as measured in TFC test to long-term learning (MWM) and memory changes (PT). We have been able to generate a mathematical model of the time course of the learning abilities of the rat undergoing tibia surgery that has been fundamental for establishing such correlations. These correlations might have implications in surgical patients with regard to the relation between delirium and long-term cognitive decline.

Highlights.

Surgical trauma generates a postoperative learning deficit.

Severity of memory decline at 1 week after surgery presages long-lasting deteriorations in learning and memory.

Acute and chronic changes in cognition are exaggerated in animals with metabolic syndrome.

Footnotes

Supported by: FIS(Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Health Department, Government of Spain) grants n° PS09/01209 and BAE 2012/00069 (P.L. Gambús) and National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland grant R01GM104194 (M. Maze).

References

- Beal SL, Sheiner LB. 2006 NONMEM User's Guides Ellicott City, Maryland, USA. Icon Development Solutions; Ellicott City, Maryland, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cibelli M, Fidalgo AR, Terrando N, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Takata M, Lever IJ, Nanchahal J, Fanselow MS, Maze M. Role of interleukin- 1beta in postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:360–368. doi: 10.1002/ana.22082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degos V, Vacas S, Han Z, van RN, Gressens P, Su H, Young WL, Maze M. Depletion of bone marrow-derived macrophages perturbs the innate immune response to surgery and reduces postoperative memory dysfunction. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:527–536. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182834d94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Degos V, Koch LG, Britton SL, Zhu Y, Vacas S, Terrando N, Nelson J, Su X, Maze M. Surgery results in exaggerated and persistent cognitive decline in a rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2013a;118:1098–1105. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318286d0c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Zhu Y, Koliwad SK, Koch LG, Britton SL, Maze M. Persistent postoperative cognitive decline is associated with dysregulation of macrophage activation in the white adipose tissue in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. American Society of Anesthesiologists; San Francisco, California: 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo AR, Cibelli M, White JP, Nagy I, Noormohamed F, Benzonana L, Maze M, Ma D. Peripheral orthopaedic surgery down-regulates hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor and impairs remote memory in mouse. Neuroscience. 2011;190:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambus PL, Troconiz IF. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling in anaesthesia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:72–84. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch LG, Britton SL. Artificial selection for intrinsic aerobic endurance running capacity in rats. Physiol Genomics. 2001;5:45–52. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.5.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TG, Weldon BC, Garvan CW, Dede DE, van der Aa MT, Heilman KM, Gravenstein JS. Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:18–30. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000296071.19434.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould DR, Upton RN. Basic concepts in population modeling, simulation, and model-based drug development. CPT Pharmacometric Syst Pharmacol. 2012;1:e6. doi: 10.1038/psp.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JL, Fiedler-Kelly J. Introduction to Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analysis with Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. Wiley; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, Moons KG, Geevarghese SK, Canonico A, Hopkins RO, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-Plus. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sheiner LB. A new approach to the analysis of analgesic drug trials, illustrated with bromfenac data. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56:309–322. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih J, May LD, Gonzalez HE, Lee EW, Alvi RS, Sall JW, Rau V, Bickler PE, Lalchandani GR, Yusupova M, Woodward E, Kang H, Wilk AJ, Carlston CM, Mendoza MV, Guggenheim JN, Schaefer M, Rowe AM, Stratmann G. Delayed environmental enrichment reverses sevoflurane-induced memory impairment in rats. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:586–602. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318247564d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto E, Staab A, Doege C, Freiwald M, Munzert G, Troconiz IF. Comparison of different semi-mechanistic models for chemotherapy-related neutropenia: application to BI 2536 a Plk-1 inhibitor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1517–1527. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Feng X, Terrando N, Yan Y, Chawla A, Koch LG, Britton SL, Matthay MA, Maze M. Dysfunction of inflammation-resolving pathways is associated with exaggerated postoperative cognitive decline in a rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Med. 2012;18:1481–1490. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Feng X, Terrando N, Yan Y, Chawla A, Koch LG, Britton SL, Matthay MA, Maze M. Dysfunction of inflammation-resolving pathways is associated with exaggerated postoperative cognitive decline in a rat model of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Med. 2013;18:1481–1490. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrando N, Monaco C, Ma D, Foxwell BM, Feldmann M, Maze M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha triggers a cytokine cascade yielding postoperative cognitive decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010a;107:20518–20522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014557107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrando N, Rei FA, Vizcaychipi M, Cibelli M, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Maze M. The impact of IL-1 modulation on the development of lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive dysfunction. Crit Care. 2010b;14:R88. doi: 10.1186/cc9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troconiz IF, Cendros JM, Soto E, Prunonosa J, Perez-Mayoral A, Peraire C, Principe P, Delavault P, Cvitkovic F, Lesimple T, Obach R. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of drug-induced adverse effects of a novel homocamptothecin analog, elomotecan (BN80927), in a Phase I dose finding study in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1906-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacas S, Degos V, Tracey KJ, Maze M. High-mobility group box 1 protein initiates postoperative cognitive decline by engaging bone marrow-derived macrophages. Anesthesiology. 2013 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]