Abstract

Late-onset neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by neurological symptoms and progressive neuronal death. Accumulating evidence suggests that neuronal dysfunction, rather than neuronal death, causes the symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases. However, the mechanisms underlying the dysfunction that occurs prior to cell death remain unclear. To investigate the synaptic basis of this dysfunction, we employed in vivo two-photon imaging to analyse excitatory postsynaptic dendritic protrusions. We used Sca1154Q/2Q mice, an established knock-in mouse model of the polyglutamine disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), which replicates human SCA1 features including ataxia, cognitive impairment, and neuronal death. We found that Sca1154Q/2Q mice exhibited greater synaptic instability than controls, without synaptic loss, in the cerebral cortex, where obvious neuronal death is not observed, even before the onset of distinct symptoms. Interestingly, this abnormal synaptic instability was evident in Sca1154Q/2Q mice from the synaptic developmental stage, and persisted into adulthood. Expression of synaptic scaffolding proteins was also lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than controls before synaptic maturation. As symptoms progressed, synaptic loss became evident. These results indicate that aberrant synaptic instability, accompanied by decreased expression of scaffolding proteins during synaptic development, is a very early pathology that precedes distinct neurological symptoms and neuronal cell death in SCA1.

Many late-onset neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and prion and polyglutamine diseases, share common features, such as the aggregation of toxic proteins in neurons, and progressive neuronal cell death1,2. Accumulating evidence from patients and animal models suggests that the initial symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases are a result of neuronal dysfunction rather than cell death3. However, the nature of this dysfunction that occurs prior to cell death remains unknown.

Many neurodegenerative diseases are attributed to multiple factors, including genetic and environmental predispositions. On the other hand, spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), a polyglutamine disease, is a monogenic disorder caused by the expansion of an unstable CAG trinucleotide repeat tract encoding a polyglutamine stretch in the ATXN1 gene4. The Sca1154Q/2Q knock-in mouse model, harbouring 154 CAG repeats within the endogenous ATXN1 locus, closely reproduces the features of human SCA15, including neuronal cell death, ataxia, motor incoordination, and cognitive impairment6,7. Although the number of CAG repeats in Sca1154Q/2Q mice is much higher than that in human patients, another knock-in SCA1 mouse model harbouring 78 CAG repeats, similar to the number in patients, displays only mild behavioural deficits late in life8. Thus, Sca1154Q/2Q mice are suitable for studying symptom progression. Sca1154Q/2Q mice develop motor learning impairment before any obvious Purkinje cell death occurs or nuclear inclusions form in the cerebellum5. In the limbic area, Sca1154Q/2Q mice show nuclear inclusions in pyramidal neurons, and cognitive deficits are observed without evident neuronal loss5. Clinical studies have demonstrated that neuronal death is most prominent in the cerebellum, whereas little occurs in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, despite the presence of cognitive impairments in patients with SCA16. These lines of evidence suggest that neuronal dysfunction, preceding cell death, causes subsequent behavioural impairments in the pathogenesis of SCA1; however, the mechanisms underlying the dysfunction remain unclear.

In the present study, we focused on SCA1 as a genetic model of neurodegenerative disease, and used Sca1154Q/2Q knock-in mice to elucidate the synaptic basis of neuronal dysfunction. We analysed the dynamics, morphology, and density of dendritic protrusions, which are excitatory postsynaptic structures classified into mature ‘spines’ and immature ‘filopodia’. These features are strongly associated with synaptic development9, plasticity10, and various pathologies11. Using two-photon laser-scanning microscopy, we investigated the synaptic pathologies of Sca1154Q/2Q knock-in mice in vivo, maintaining contributions from peripheral tissues and non-neuronal cells expressing mutant ataxin-1, as well as neurons. To evaluate neuronal dysfunction while excluding the effects of neuronal death, we focused on the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, in which apparent neuronal death does not occur despite the presence of cognitive dysfunction in both Sca1154Q/2Q mice and human SCA1 patients5,7. Our findings demonstrate that aberrant synaptic instability accompanied by a reduction in the expression of scaffolding proteins in affected neurons appears during synaptic development in SCA1 mice. These results suggest that deficits in neuronal circuitry development may underlie subsequent behavioural and neurological impairments in late-onset neurodegenerative diseases.

Results

SCA1 mice show aberrant instability of dendritic protrusions before the onset of distinct symptoms

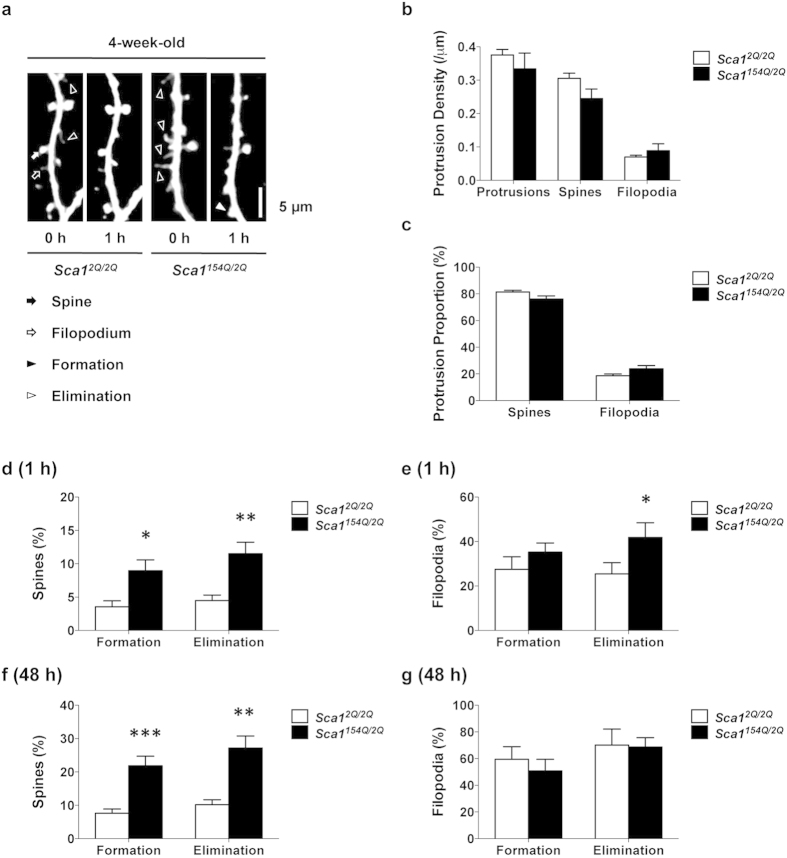

Motor learning impairments in Sca1154Q/2Q mice are observed by 5 weeks of age, and spatial and fear memory deficits by 8 weeks. Although nuclear inclusions of mutant ataxin-1 are observed by 6 weeks, there is no neuronal death in the limbic area during such early stages of the disease5. We therefore investigated synaptic abnormalities in 4-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice as a possible early SCA1 phenotype. We performed in vivo two-photon imaging in layer 1 dendrites of the primary somatosensory cortex in Sca1154Q/2Q and control Sca12Q/2Q mice, and analysed the morphology, formation, and elimination of dendritic protrusions over a 1 h period under anaesthesia (Fig. 1a). Dendritic protrusions were classified into spines and filopodia according to their morphology, because filopodia are less stable than spines, and their density decreases with development9. We did not observe any clear differences between Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice in the morphology of dendritic protrusions. Furthermore, we found no significant differences in the density of protrusions between Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age (Fig. 1b) [total protrusions: Sca12Q/2Q (0.38 ± 0.02/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.33 ± 0.05/μm), p = 0.4532; spines: Sca12Q/2Q (0.31 ± 0.02/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.24 ± 0.03/μm), p = 0.0909; filopodia: Sca12Q/2Q (0.070 ± 0.005/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.09 ± 0.02/μm), p = 0.4159; unpaired t-test]. There were also no significant differences between 4-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice in the number of spines or filopodia as a percentage of the total protrusions (Fig. 1c) [spines: Sca12Q/2Q (81 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (76 ± 2%), p = 0.0747; filopodia: Sca12Q/2Q (19 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (24 ± 2%), p = 0.0747; unpaired t-test]. Next, we analysed the dynamics of the protrusions in order to estimate synaptic stability. Notably, we found that the rates of formation and elimination of spines over 1 h were significantly higher in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 1d) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (3.6 ± 0.9%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (9 ± 2%), p = 0.0101; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (4.5 ± 0.8%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (12 ± 2%), p = 0.0017; unpaired t-test]. The elimination rate of filopodia over 1 h was also significantly higher in Sca1154Q/2Q mice, but the difference in their formation rate did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1e) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (27 ± 6%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (35 ± 4%), p = 0.2711; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (23 ± 4%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (42 ± 7%), p = 0.0341; unpaired t-test]. Anaesthetics can increase the formation of filopodia within a 1 h period12; therefore, to eliminate the effects of anaesthesia on synaptic dynamics, we performed in vivo imaging over 48 h, during which time the mice were allowed to recover from the anaesthesia after the first imaging session and were returned to their home cages until the next session. We confirmed that both formation and elimination rates of spines in Sca1154Q/2Q mice were also significantly higher than those in Sca12Q/2Q mice over a 48 h period (Fig. 1f) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (8 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (23 ± 3%), p < 0.0001; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (10 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (28 ± 4%), p = 0.0003; unpaired t-test]. Neither the formation nor elimination rates of filopodia over 48 h were significantly different between groups, probably owing to the very high rates measured over 48 h even in control mice (Fig. 1g) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (59 ± 9%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (52 ± 9%), p = 0.5763; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (70 ± 10%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (72 ± 7%), p = 0.8919; unpaired t-test]. These data indicate that Sca1154Q/2Q mice show abnormal synaptic instability during synaptic development, before the onset of obvious symptoms, and that these altered dynamics are detectable by imaging under anaesthesia during a 1 h period.

Figure 1. SCA1 mice show abnormal synaptic instability before the onset of distinct symptoms.

(a) In vivo two-photon imaging of layer 1 dendrites of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in 4-week-old Sca12Q/2Q mice (n = 14 dendrites from five animals) and Sca1154Q/2Q mice (n = 17 dendrites from five animals). Repeated imaging of the same dendrites in each group over 1 h enables visualization of the formation (filled arrowhead) and elimination (open arrowheads) of dendritic protrusions in Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age. Dendritic protrusions were classified into two groups: spines (filled arrow) and filopodia (open arrow). Images are best projections (3–7 optical sections, 0.75 μm apart). (b) Dendritic protrusion density in 4-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. (c) Spines and filopodia as a percentage of total protrusions in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. (d) Percentage of total spines formed and eliminated over 1 h. Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age showed higher formation and elimination rates of spines than Sca12Q/2Q mice. (e) Percentage of total filopodia formed and eliminated over 1 h. In 4-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice, the elimination rate of filopodia was higher than that in Sca12Q/2Q mice, whereas the rate of formation was not different from Sca12Q/2Q mice. (f) Percentage of total spines formed and eliminated over 48 h. Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age (n = 12 dendrites from six mice) exhibited higher formation and elimination rates of spines than Sca12Q/2Q mice (n = 18 dendrites from eight mice). (g) Percentage of total filopodia formed and eliminated over 48 h. No differences were observed in the rates of formation or elimination of filopodia between 4-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Student t-test. Scale bar, 5 μm.

SCA1 mice develop abnormal protrusion morphology with persisting synaptic instability

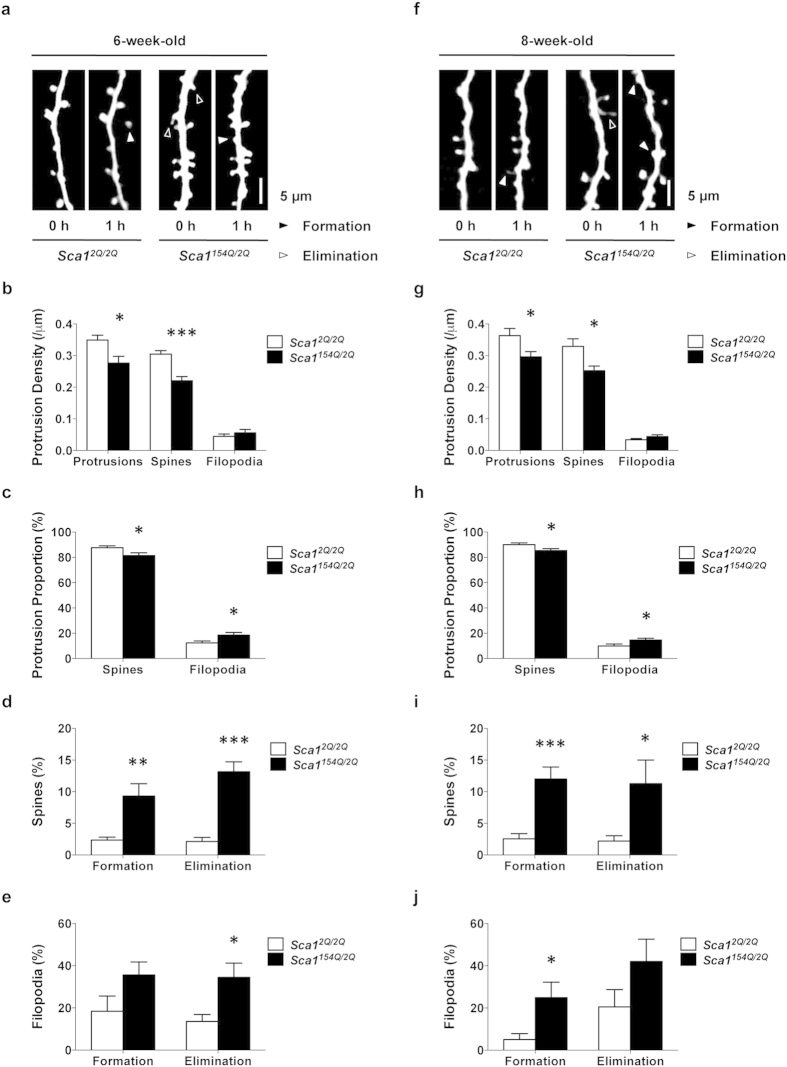

We demonstrated that synaptic instability occurs in SCA1 mice before the onset of distinct symptoms at 4 weeks of age. Next, we evaluated the progression of synaptic pathology in SCA1 mice until 8 weeks of age, by which time dendritic spines have normally stabilised and the density of filopodia has reached a minimum9. Sca1154Q/2Q mice develop motor learning impairment and nuclear inclusions by 6 weeks of age, and memory deficits by 8 weeks5. We investigated the dynamics and morphology of dendritic protrusions in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 6 (Fig. 2a) and 8 weeks of age (Fig. 2f). In 6-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice, the density of dendritic spines and protrusions was significantly lower than that in age-matched Sca12Q/2Q mice, whereas the density of filopodia did not differ between the groups (Fig. 2b) [protrusions: Sca12Q/2Q (0.35 ± 0.02/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.28 ± 0.02/μm), p = 0.0101; spines: Sca12Q/2Q (0.30 ± 0.01/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.22 ± 0.01/μm), p < 0.0001; filopodia: Sca12Q/2Q (0.04 ± 0.01/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.06 ± 0.01/μm), p = 0.3871; unpaired t-test]. The number of spines as a percentage of total protrusions was significantly lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice at 6 weeks (Fig. 2c) [Sca12Q/2Q (88 ± 2%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (81 ± 2%), p = 0.0284; unpaired t-test], whereas that of filopodia was higher (Fig. 2c) [Sca12Q/2Q (12 ± 2% vs Sca1154Q/2Q (19 ± 2%), p = 0.0284; unpaired t-test]. Spine dynamics were significantly greater in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice at 6 weeks of age (Fig. 2d) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (2.3 ± 0.5%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (9 ± 2%), p = 0.0018; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (2.1 ± 0.6%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (13 ± 2%), p < 0.0001; unpaired t-test]. Regarding the filopodium dynamics of 6-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice, the elimination rate was significantly higher, but the formation rate was not different from that in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 2e) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (18 ± 7%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (36 ± 6%), p = 0.0785; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (14 ± 3%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (35 ± 7%), p = 0.0100; unpaired t-test]. In 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice, total protrusion and spine densities were significantly lower than those in age-matched Sca12Q/2Q mice, whereas filopodium density was not different between the two groups (Fig. 2g) [protrusions: Sca12Q/2Q (0.36 ± 0.02/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.30 ± 0.02/μm), p = 0.0343; spines: Sca12Q/2Q (0.33 ± 0.02/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.25 ± 0.01/μm), p = 0.0175; filopodia: Sca12Q/2Q (0.033 ± 0.004/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (0.044 ± 0.006/μm), p = 0.1621; unpaired t-test]. The number of spines as a percentage of the total protrusions was significantly lower in 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 2h) [Sca12Q/2Q (90 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (85 ± 2%), p = 0.0403; unpaired t-test], whereas that of filopodia was higher in 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 2h) [Sca12Q/2Q (10 ± 1%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (15 ± 2%), p = 0.0403; unpaired t-test]. Both formation and elimination rates of spines in 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice were significantly higher than those in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 2i) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (2.7 ± 0.7%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (13 ± 2%), p < 0.0001; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (2.0 ± 0.8%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (12 ± 4%), p = 0.0176; unpaired t-test]. The formation rate of filopodia in 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice was higher than that in Sca12Q/2Q, whereas the elimination rate was not significantly different (Fig. 2j) [formation rate: Sca12Q/2Q (5 ± 3%) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (25 ± 8%), p = 0.0134; elimination rate: Sca12Q/2Q (21 ± 8% vs Sca1154Q/2Q (42 ± 11%), p = 0.1166; unpaired t-test]. These data indicate that SCA1 mice have immature dendritic morphology and a loss of dendritic protrusions associated with persisting synaptic instability and the progression of SCA1 symptoms.

Figure 2. SCA1 mice develop immature protrusion morphology and loss of dendritic protrusions, associated with persisting synaptic instability after symptom onset.

(a,f) In vivo two-photon imaging of dendrites in 6- and 8-week-old Sca12Q/2Q mice (n = 14 dendrites from five mice and n = 12 dendrites from four mice, respectively) and Sca1154Q/2Q mice (n = 14 dendrites from five mice and n = 10 dendrites from five mice, respectively). Repeated imaging of the same dendrites over 1 h in each group showed increased formation (filled arrowhead) and elimination (open arrowheads) of dendritic protrusions in Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 6 and 8 weeks of age. (b,g) Dendritic protrusion density in 6- and 8-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. Sca1154Q/2Q mice exhibited decreased spine density at both 6 (b) and 8 (g) weeks of age. (c,h) Spines and filopodia as a percentage of total protrusions in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 6 (c) and 8 (h) weeks of age. The percentage of spines was lower, and filopodia higher, in 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice, whereas no differences were observed in 6-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice. (d,i) Percentage of total spines formed and eliminated. Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed higher formation and elimination rates of spines than Sca12Q/2Q mice at 6 (d) and 8 (i) weeks of age. (e,j) Percentage of total filopodia formed and eliminated. Formation and elimination rates were greater in 6- (f) and 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice (k). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student t-test. Scale bar, 5 μm.

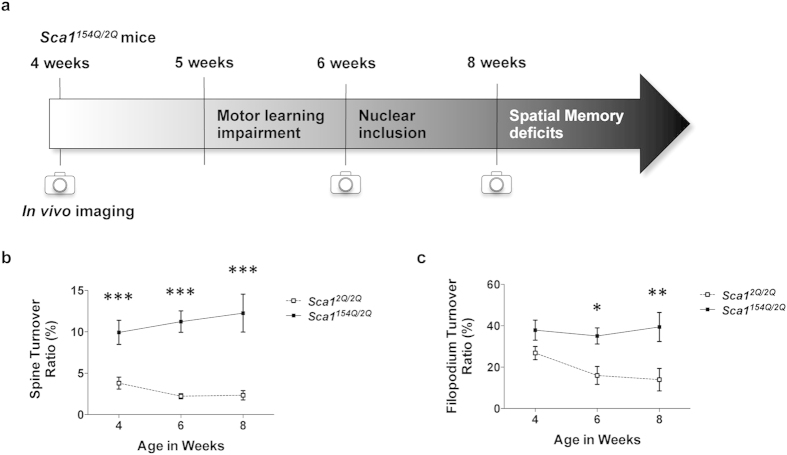

To evaluate protrusion stabilization that occurs with neuronal circuitry development and its disruption in SCA1 mice, we investigated the 1 h turnover rate of spines and filopodia in SCA1 mice at various ages during development (Fig. 3a). In Sca1154Q/2Q mice, the spine turnover rate was significantly higher than that in Sca12Q/2Q mice throughout synaptic maturation (Fig. 3b; 4 wks: p = 0.0009; 6 wks: p < 0.0001; 8 wks: p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test), whereas filopodium turnover rate was higher in 6- and 8-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice (Fig. 3c; 4 wks: p = 0.2299; 6 wks: p = 0.0123; 8 wks: p = 0.0042; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test). No significant difference was observed in filopodium turnover rate at 4 weeks of age. This may be because of the high turnover rate of filopodia during early synaptic development, even in the control group. These results indicate that the normal development of dendritic protrusions, particularly filopodium stabilisation, is disrupted in Sca1154Q/2Q mice.

Figure 3. Dendritic protrusions do not stabilize with maturation in SCA1 mice.

(a) Schematic of symptom progression in Sca1154Q/2Q mice. (b) Compiled turnover rates of spines (ratio of spines formed and eliminated to twice the total number of spines) in 4-, 6-, and 8-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. Sca1154Q/2Q mice demonstrated higher spine turnover rates throughout synaptic development than Sca12Q/2Q mice. (c) Compiled turnover rates of filopodia at different ages (in weeks). Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed higher filopodium turnover rates than Sca12Q/2Q mice from 6 weeks of age. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student t-test (b) or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (c).

SCA1 mice exhibit progressive impairments in the density and morphology of dendritic protrusions in the hippocampus

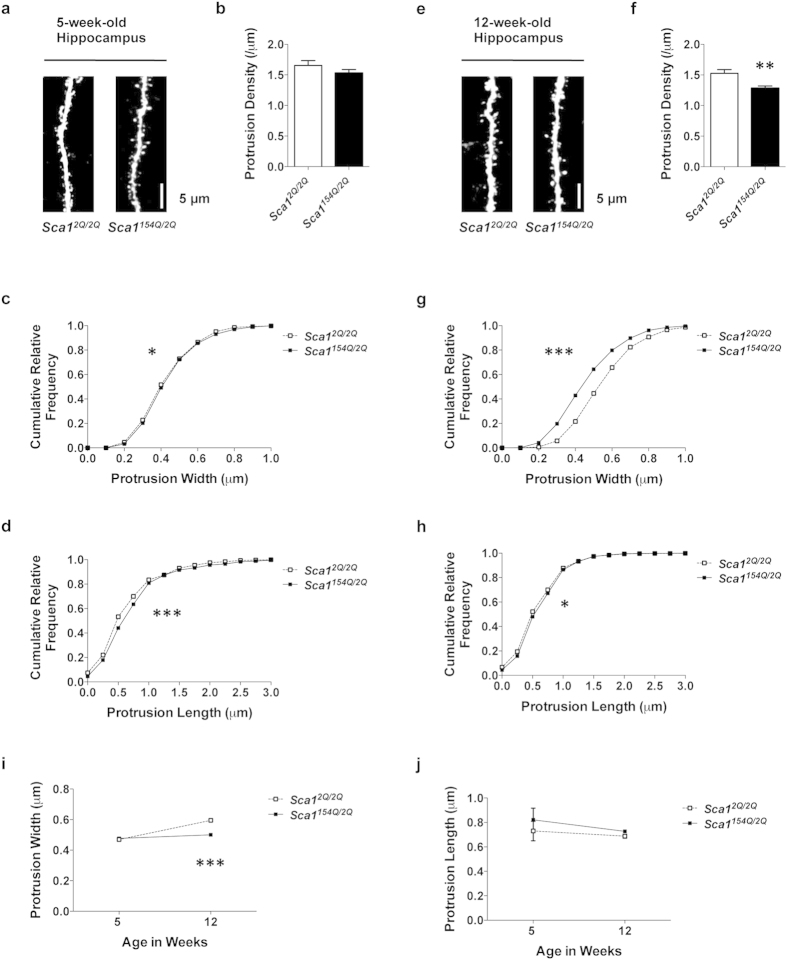

Sca1154Q/2Q mice show spatial memory deficits at 8 weeks of age5, but there is little neuronal death in the hippocampus, a region associated with spatial learning6. To elucidate the neuronal dysfunction associated with cognitive deficit in the absence of neuronal loss, we focused on hippocampal CA1 dendrites and investigated the density and morphology of dendritic protrusions in SCA1 mice. We performed confocal laser-scanning microscopy on slices of fixed brain samples from 5- and 12-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice (Fig. 4a,e). We chose this technique because the hippocampus is deep within the brain, precluding the non-invasive use of in vivo two-photon imaging. No difference in protrusion density was observed between Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 5 weeks of age (Fig. 4b) [Sca12Q/2Q (1.66 ± 0.08/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (1.53 ± 0.06/μm), p = 0.2135; unpaired t-test], whereas at 12 weeks, dendritic protrusion density was significantly lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 4f) [Sca12Q/2Q (1.53 ± 0.06/μm) vs Sca1154Q/2Q (1.28 ± 0.04/μm), p = 0.0011; unpaired t-test]. An abnormal frequency distribution of dendritic protrusion width was observed in Sca1154Q/2Q mice, particularly at 12 weeks of age, when the distribution curve shifted to the left (Fig. 4c,g; 5 wks: p = 0.0107; 12 wks: p < 0.0001; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). The mean dendritic protrusion width in 12-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice was lower than that in Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 4i; 5 wks: p = 0.8637; 12 wks: p < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test). These results show that the dendritic protrusion width in Sca1154Q/2Q mice decreased as SCA1 symptoms developed. An abnormal frequency distribution of protrusion length in Sca1154Q/2Q mice was evident at 5 weeks of age, and the frequency distribution curve was shifted to the right (Fig. 4d,h; 5 wks: p < 0.0001; 12 wks: p = 0.0441; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). No difference was observed in the mean length of dendritic protrusions between Sca1154Q/2Q and Sca12Q/2Q mice at either age (Fig. 4j; 5 wks: p = 0.5210; 12 wks: p > 0.9999; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test). These results indicate that the protrusion lengths in Sca1154Q/2Q mice differ little from those in Sca12Q/2Q mice from early life through to adulthood. In summary, SCA1 mice demonstrated progressive deficits in dendritic protrusions in the hippocampus from adult ages.

Figure 4. SCA1 mice show progressive deficits in the density and morphology of hippocampal dendritic protrusions.

(a–h) Analysis of dendrites in the hippocampal CA1 stratum radiatum of 5- (a–d) and 12-week-old (e–h) Sca12Q/2Q mice (n = 15 dendrites from three animals and n = 20 dendrites from four animals, respectively) and Sca1154Q/2Q mice (n = 15 dendrites from three animals and n = 25 dendrites from five animals, respectively). (a,e) Confocal images of dendrites in 5- and 12-week-old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. Images are best projections (3–7 optical sections, 0.43 μm apart). (b,f) Dendritic protrusion density in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed a lower protrusion density than Sca12Q/2Q mice at 12 weeks of age. (c,g) Cumulative frequency distribution of protrusion width in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. The distribution of protrusion width was abnormal in Sca1154Q/2Q mice, particularly at 12 weeks of age. (d,h) Cumulative frequency distribution of protrusion length in Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. The distribution of protrusion length was abnormal in Sca1154Q/2Q mice at both ages. (i) Mean protrusion width at 5 and 12 weeks of age. Sca1154Q/2Q mice had narrower protrusions than Sca12Q/2Q mice at 12 weeks of age. (j) Mean protrusion length at 5 and 12 weeks of age. Sca1154Q/2Q mice had normal protrusion lengths at both ages. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (b,f,i,j). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, Student t-test (b,f), Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (c,d,g,h), or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test (i,j). Scale bar, 5 μm.

Decreased expression of synaptic scaffolding proteins in SCA1 mice

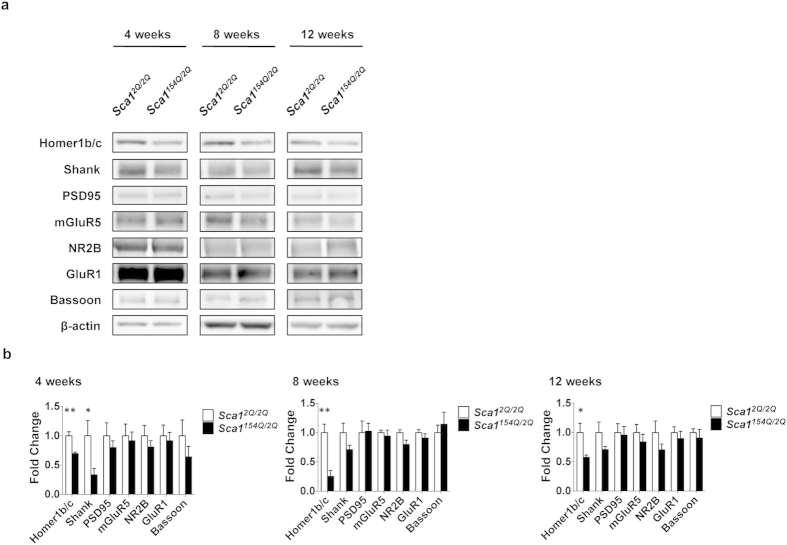

To investigate the molecular mechanism causing synaptic instability and subsequent SCA1 pathology, we measured the expression levels of synaptic proteins in the cerebral cortex by immunoblotting (Fig. 5a). Homer1b/c protein expression in Sca1154Q/2Q mice was significantly lower at 4 (0.70 ± 0.07-fold; p = 0.0032; unpaired t-test), 8 (0.3 ± 0.2-fold; p = 0.0055; unpaired t test), and 12 weeks of age (0.6 ± 0.2-fold; p = 0.0330; unpaired t-test) than in age-matched Sca12Q/2Q mice (Fig. 5b). Shank protein levels were also lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice compared with Sca12Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age (0.3 ± 0.3-fold; p = 0.0466; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 5b). These results provide evidence that reduced expression of the synaptic scaffolding proteins Homer and Shank is associated with early synaptic pathology in SCA1 mice.

Figure 5. Low synaptic scaffolding protein expression in SCA1 mice.

(a) Immunoblotting of the cerebral cortex in 4-, 8-, and 12-week old Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice. (b) Protein expression levels of Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 (left), 8 (middle), and 12 (right) weeks of age (n = 5 mice in all analyses). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Student t-test.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms of the neuronal dysfunction that precedes behavioural impairments and neuronal death is a longstanding challenge in neurodegenerative diseases such as SCA1. We found that Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed abnormal synaptic instability in the cerebral cortex during the development of neuronal circuitry, when apparent nuclear inclusions, neuronal death, or behavioural impairments are not yet observed. Synaptic instability in the cerebral cortex of Sca1154Q/2Q mice persisted into adulthood in the cerebral cortex, and subsequent deficits in the number and morphology of dendritic protrusions became evident as symptoms developed. We also observed progressive deficits of dendritic protrusions in Sca1154Q/2Q hippocampus, a region implicated in cognitive dysfunction in SCA1. Furthermore, compared with Sca12Q/2Q mice, Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed lower expression levels of the postsynaptic scaffolding proteins Homer and Shank, even before synaptic maturation, when increased synaptic instability was observed. These results suggest that one of the mechanisms underlying neuronal dysfunction in SCA1 involves the association of synaptic instability, abnormal protrusion morphology during synaptic development, and a decline in scaffolding protein expression. We therefore hypothesized that impaired synaptic development triggers subsequent neurological symptoms and pathological abnormalities.

We used an established knock-in mouse model of SCA1, which expresses mutant ataxin-1 at endogenous levels in the normal spatial and temporal pattern, and accurately replicates pathological features observed in the human disease5,13. Sca1154Q/2Q mice show motor learning impairment by approximately 5 weeks of age, which is followed by the development of nuclear inclusions, cognitive deficits, and Purkinje cell death. Other studies have also demonstrated motor learning impairment in 5-week-old mice, before neuronal death in the cerebellum, which occurs only in the late stages of the disease, using Sca1 transgenic mice expressing full-length human ATXN1 cDNAs with 82 CAG repeats specific to Purkinje cells14,15. Therefore, the abnormal synaptic instability detected in 4-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice in the present study is one of the earliest pathological signs observed in SCA1 mouse models.

We performed in vivo imaging to rigorously evaluate the synaptic pathology of SCA1, because non-neuronal cells expressing mutant ataxin-1 are also involved in the pathogenesis of SCA1 models16,17,18. Furthermore, we believe that analysis of protrusion dynamics in living animals, in addition to morphology, enabled us to detect potential synaptic lesions. There have been cases in which changes in protrusion dynamics were observed, without any alterations in protrusion density, upon changes in synaptic plasticity and pathology10,19. Indeed, we also demonstrated a higher turnover rate of dendritic protrusions in 4-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice, in the absence of any differences in protrusion density. We applied the thinned-skull method for in vivo imaging, which allows excitation and emission lights to penetrate the skull without eliciting any microglial inflammatory responses20, because many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with inflammation of the brain21,22.

A recent study using the rotarod test demonstrated that motor skill acquisition and coordination require the activation of neurons in the secondary motor cortex, which receives inputs from the somatosensory cortex23. Here, we demonstrated synaptic instability and dendritic spine loss in the somatosensory cortex of Sca1154Q/2Q mice, which also show impaired rotarod performance5. These results suggest that Sca1154Q/2Q mice have deficits in somatosensory and sensorimotor function. In the cerebellum of Sca1154Q/2Q mice, however, no synaptic dysfunction, neuronal cell death or nuclear inclusions of ataxin-1 protein are observed when motor incoordination develops at 5 weeks of age5. Sca1154Q/2Q mice do not show cerebellar neurodegeneration until 16 weeks and nuclear inclusions until 21 weeks. Therefore, the involvement of cerebellar dysfunction in the early symptomatic stage in Sca1154Q/2Q mice remains unclear.

Previous studies, using conditional Sca1 transgenic mice that stage-specifically express a full-length human ATXN1 cDNA with 82 CAG repeats in the cerebellum, have demonstrated that the suppression of mutant ataxin-1 expression during the first 14 postnatal weeks inhibits subsequent motor dysfunction and dendritic atrophy24,25. Suppressing the expression of mutant ataxin-1, even for the first 5 postnatal weeks, can also inhibit impairments in synaptic transmission in the adult cerebellum26. Neuronal circuitry development occurs during the first few postnatal weeks, with a decrease in the turnover of dendritic protrusions and in the ratio of filopodia to total protrusions9. We identified enhanced synaptic instability in Sca1154Q/2Q mice at 4 weeks of age compared with controls. These results suggest that the stage at which synaptic development occurs is a critical period in SCA1 pathogenesis, and that dendritic protrusions are excessively unstable in SCA1 mice and do not stabilise with maturation. Our present findings can be interpreted as developmental impairment in the synapses of SCA1 mice. This is a conceptually novel finding that implies that it is not only neurodevelopmental disorders, such as fragile X syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia that involve deficits in synaptic development, but also SCA1, a late-onset neurodegenerative disease. It should be noted that synaptic instability in SCA1 mice is commonly observed in animal models of these neurodevelopmental disorders19,27,28,29. Interestingly, Shank genes, associated with autism, were also downregulated in SCA1 mice, and Shank is required for the maintenance of the density and morphology of dendritic spines30,31. Other studies using mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s have also demonstrated instability and progressive loss of dendritic protrusions similar to that observed in Sca1154Q/2Q mice32,33; however, these studies did not investigate the dynamics of dendritic protrusions at 4 weeks of age, i.e., during synaptic development. In contrast, we detected abnormal synaptic instability in 4-week-old Sca1154Q/2Q mice. It is possible that the Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease models both show synaptic instability during development of neuronal circuitry, due to the similarities in synapse pathologies and subsequent progression of symptoms among these neurodegenerative disease models34,35. In Huntington’s disease models in particular, there are many similarities to Sca1154Q/2Q mice: both Huntington’s and SCA1 are polyglutamine diseases; Huntington’s mouse models (R6/1 and R6/2) and Sca1154Q/2Q mice have the same extent of expanded CAG repeats; and both models show synaptopathy36,37,38,39,40. We can therefore hypothesize that many neurodegenerative diseases share latent deficits in neuronal circuitry development, which precede the onset of symptoms.

The hippocampus of Sca1154Q/2Q mice show impaired CA1 synaptic plasticity and dendritic arborization by 24 weeks of age, but no differences from control mice are observed until 8 weeks of age5,13. Our present results indicate that an evident decrease in the density of dendritic protrusions in the hippocampus of Sca1154Q/2Q mice occurs between 5 and 12 weeks of age. This suggests that synaptic deficits in the hippocampus of Sca1154Q/2Q mice develop by 12 weeks, and that they are mainly due to postsynaptic impairments. In the cerebral cortex, however, Sca1154Q/2Q mice showed synaptic instability by 4 weeks of age and a decrease in synaptic number by 6 weeks. It is possible that in the hippocampus, Sca1154Q/2Q mice also develop deficits in dendritic protrusion dynamics during the early stages of development. Sca1154Q/2Q knock-in mice demonstrate cerebellar abnormalities, manifesting as motor learning impairment, at 5 weeks of age, although there is little difference from controls in the electrophysiological properties of Purkinje cells at this age5. The association between motor behavioural impairment and synaptic dysfunction in the cerebellum of Sca1154Q/2Q mice remains unknown, and in vivo imaging studies of the synapses of Purkinje cells in Sca1154Q/2Q mice are warranted.

In the present study, we found that expression levels of Homer and Shank proteins were lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice than in Sca12Q/2Q mice. This decline in the expression of postsynaptic scaffolding proteins occurred before synaptic maturation. Interestingly, Shank proteins were lower in Sca1154Q/2Q mice exclusively at 4 weeks of age. Shank1 and Shank2 mRNA expression are higher during postnatal brain development than after maturation41, and their temporal expression patterns are similar to that of ATXN1 mRNA42. Therefore, the effect of mutant ataxin-1 on the expression of Shank proteins may be strongest during postnatal development. These lines of evidence provide an insight into the molecular mechanisms of developmental impairments in the synapses of Sca1154Q/2Q mice. It is interesting that Shank1 knock-out mice show impaired rotarod performance and decreased spine width, similarly to Sca1154Q/2Q mice43. Homer and Shank, which form a polymeric network structure at postsynaptic sites, interact with glutamate receptors and regulate their downstream signalling, inducing the accumulation of inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptors in protrusions44,45,46. Moreover, Homer and Shank proteins regulate the morphology and function of dendritic protrusions31,45. Because the morphology of dendritic protrusions correlates with the dynamics of these proteins47, Homer and Shank proteins may be involved in protrusion turnover. Our results are supported by previous studies that demonstrated a reduction in the levels of Homer3 and IP3 receptors in the Purkinje cells of Sca1 transgenic mice48,49. Taken together, this evidence suggests that Sca1154Q/2Q mice have deficits in Homer- and Shank-mediated intracellular calcium release from IP3 receptors, and the deficits may cause synaptic instability and abnormal synaptic maturation.

Materials and Methods

All experimental protocols were approved by an Animal Ethics Committee at the National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan, and performed in strict accordance with institutional guidelines.

Experimental animals

Thy1-YFP H-line mice, expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) predominantly in layer 5 pyramidal neurons, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory50. Sca1154Q/2Q mice were kindly provided by Dr. K. Watase at Tokyo Medical and Dental University5. Both mouse strains were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice. Heterozygous Thy1-YFP mice were crossed with Sca1154Q/2Q mice to yield double transgenic animals heterozygous for Thy1-YFP and the knock-in mutation of the Sca1 allele (Thy1-YFP+/−; Sca1154Q/2Q). As a control, age-matched littermates heterozygous for Thy1-YFP (Thy1-YFP+/−; Sca12Q/2Q) were used. Only male offspring heterozygous for YFP were used because the density of dendritic spines in female mice fluctuates daily due to the oestrus cycle51. Thy1-YFP+/−; Sca12Q/2Q mice are described as Sca12Q/2Q mice, and Thy1-YFP+/−; Sca1154Q/2Q mice are described as Sca1154Q/2Q mice throughout the manuscript. Mice were housed four per cage under controlled temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and lighting (12 h light/dark cycle), and were provided with food and water ad libitum.

Surgical procedure for in vivo imaging

The thinned-skull cranial window technique52 was used because it is less invasive than the open-skull method20. Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice expressing YFP were deeply anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine and xylazine (0.1 and 0.015 mg/g body weight, respectively). Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C with a heating pad during surgery and imaging. Eyes were lubricated with ointment to prevent dryness. After scalp incision, the primary somatosensory area (1.1 mm posterior to bregma and 3.4 mm lateral from the midline) was identified with stereotactic coordinates. A small metal plate with a round hole was glued onto the skull with cyanoacrylate glue and acrylic resin dental cement (Unifast; GC, Tokyo, Japan), and mice were fixed to a custom-made skull immobilization stage via the metal plate. The skull above the imaging area, located in the center of the hole in the metal plate, was thinned to approximately 20 μm with a high-speed microdrill (UG23A/UC210C; Urawa, Saitama, Japan) and microsurgical blade (USM-6400; Sable Industries, Vista, CA, USA). The hole in the metal plate was filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid during surgery and imaging.

In vivo transcranial two-photon imaging

Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice were imaged under anaesthesia using a two-photon laser-scanning microscope (FV1000-MPE; Olympus, Japan) with a water-immersion objective lens (25×, NA 1.05) at 8× digital zoom, yielding high-magnification images suitable for the quantification of dendritic spines. A Ti-sapphire laser (MaiTai HP DeepSee-OL; Spectra-Physics, Mountain View, CA, USA) was tuned to 950 nm. To minimize phototoxicity, laser intensity was maintained between 10 and 30 mW at the focus. Image stacks (512 × 512 pixels; 0.124 μm/pixels; 0.75 μm z-step) were taken at approximately 70 μm below the pial surface, where layer 1 dendrites of layer 5 pyramidal neurons are located. Dendrites were imaged for each experiment at time 0, and again after an interval of either 1 or 48 h. Image acquisition time in each imaging session was approximately 5 minutes. In the 1 h interval experiment, mice were maintained under anaesthesia between the two imaging sessions. In the 48 h interval experiments, mice were allowed to recover from anaesthesia after the first imaging session and were returned to their home cages until the next session.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy for ex vivo fixed samples

YFP-labelled Sca12Q/2Q and Sca1154Q/2Q mice were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and 50 μm sections were cut with a Vibratome 3000 (Vibratome Company, St Louis, MO, USA). Image stacks (1024 × 1024 pixels; 0.069 μm/pixel; 0.43 μm z-step) were taken of the secondary dendrites of CA1 neurons in the dorsal hippocampus, using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus, Japan) with a silicone-immersion objective lens (60×, NA 1.3) at a digital zoom of 3. For YFP, the excitation and emission wavelengths were 488 nm and 515 nm, respectively.

Image analysis

The turnover rate, density, head width, and neck length of the postsynaptic dendritic protrusions were analysed with Neurolucida neuron tracing software (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT, USA) from three-dimensional two-photon or confocal z-stacks. Morphometric analysis of dendritic protrusions was performed in accordance with a previous report9. Filopodia were identified as long, thin structures (head width to neck width ratio <1.2:1; protrusion length to neck width ratio >3:1). Other protrusions were classified as spines. Protrusions were identified as being identical between two successive frames by their spatial relationship to adjacent landmarks (e.g., axonal and dendritic orientations) and their relative position to immediately adjacent protrusions. Protrusions were considered different between two successive frames if they were located >0.7 μm from their expected positions based on the first image. The formation and elimination rates of the protrusions were defined as the percentage of protrusions that appeared and disappeared, respectively, between two successive frames, relative to the total protrusion number. Protrusion turnover rate was defined as the sum of the protrusions formed and eliminated, divided by twice the total number of protrusions. Data were collected from 10–18 dendrites and 460–1,162 protrusions in four to eight mice for in vivo studies, and from 15–25 dendrites and 1,676–2,350 protrusions in three to five mice for ex vivo studies.

Immunoblotting

Tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA] with EDTA-free complete protease inhibitors and PhosSTOP (Roche Applied Science). Immunoblotting was performed using the following antibodies: anti-Homer1b/c (~47 kDa; Cat. #160 023, Synaptic Systems), anti-pan-Shank (~159 kDa; MABN24, EMD Millipore), anti-PSD95 (~100 kDa; ab13552, Abcam), anti-mGluR5 (~132 kDa; AB5675, EMD Millipore), anti-NR2B (~166 kDa; MAB5220, EMD Millipore), anti-GluR1 (~106 kDa; 06-306-MN; Upstate), anti-Bassoon (~420 kDa; 6897S; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-β-actin (~42 kDa; A5441; Sigma-Aldrich). Total protein (10 μg/lane) was separated on sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to immunoblot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), incubated with 3% BSA in TBST [50 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20] for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with each primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed in TBST and further incubated with anti-mouse/rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Cat. #31430 and 31460, respectively; Thermo Scientific Pierce Antibodies). After washing in TBST, the membranes were developed with Super Signal West Dura or Femto extended duration substrate (Pierce) and analysed using a ChemiImager (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Proteins were identified by band position relative to a molecular weight marker.

Statistical analysis

To determine statistical significance, we used the Student t-test, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple-comparison test, two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple-comparison test, or the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hatanaka, Y. et al. Abnormalities in synaptic dynamics during development in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Sci. Rep. 5, 16102; doi: 10.1038/srep16102 (2015).

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiromi Fujita, Yoshiko Hara, Masako Shikama, Tomoko Okada, and Hisae Kikuchi (NCNP) for their technical assistance, and Dr. H. Akiko Popiel (Tokyo Medical University) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Synapse and Neurocircuit Pathology) [23110528, 25110741 to Y. N., 23110527, 25110739 to K. Wada] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan; Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) [23390237 to Y. N.] and for Young Scientists (B) [25871174 to Y. H.] from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan; a Grant-in-Aid for the Research Committee for Ataxic Diseases [201307025A to Y. N.] from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan; and a grant from Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) [to Y. N. and K. Wada].

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.H., K.W. and Y.N. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.H. performed the experiments and analysed the data. K.W. provided Sca1154Q/2Q mice. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Taylor J. P., Hardy J. & Fischbeck K. H. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science 296, 1991–1995 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredesen D. E., Rao R. V. & Mehlen P. Cell death in the nervous system. Nature 443, 796–802 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop J. J., Chin J. & Mucke L. A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443, 768–773 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. T. et al. Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet 4, 221–226 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watase K. et al. A long CAG repeat in the mouse Sca1 locus replicates SCA1 features and reveals the impact of protein solubility on selective neurodegeneration. Neuron 34, 905–919 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi H. Y. & Orr H. T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Semin Cell Biol 6, 29–35 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr H. T. & Zoghbi H. Y. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 30, 575–621 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzetti D. et al. Repeat instability and motor incoordination in mice with a targeted expanded CAG repeat in the Sca1 locus. Hum Mol Genet 9, 779–785 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutzendler J., Kasthuri N. & Gan W. B. Long-term dendritic spine stability in the adult cortex. Nature 420, 812–816 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg J. T. et al. Long-term in vivo imaging of experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in adult cortex. Nature 420, 788–794 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P., Cahill M. E., Jones K. A., VanLeeuwen J. E. & Woolfrey K. M. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci 14, 285–293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Chang P. C., Bekker A., Blanck T. J. & Gan W. B. Transient effects of anesthetics on dendritic spines and filopodia in the living mouse cortex. Anesthesiology 115, 718–726 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watase K. et al. Lithium therapy improves neurological function and hippocampal dendritic arborization in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 mouse model. PLoS Med 4, e182 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burright E. N. et al. SCA1 transgenic mice: a model for neurodegeneration caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat. Cell 82, 937–948 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark H. B. et al. Purkinje cell expression of a mutant allele of SCA1 in transgenic mice leads to disparate effects on motor behaviors, followed by a progressive cerebellar dysfunction and histological alterations. J Neurosci 17, 7385–7395 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig P. J. et al. Glial S100B Positive Vacuoles In Purkinje Cells: Earliest Morphological Abnormality In SCA1 Transgenic Mice. J Neurol Sci Turk 23, 166–174 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni R. et al. Reactive astrocytosis and glial glutamate transporter clustering are early changes in a spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 transgenic mouse model. Neuron Glia Biol 3, 335–351 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiwaku H. et al. Suppression of the novel ER protein Maxer by mutant ataxin-1 in Bergman glia contributes to non-cell-autonomous toxicity. EMBO J 29, 2446–2460 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Martin A., Crespo M. & Portera-Cailliau C. Delayed stabilization of dendritic spines in fragile X mice. J Neurosci 30, 7793–7803 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. T., Pan F., Yang G. & Gan W. B. Choice of cranial window type for in vivo imaging affects dendritic spine turnover in the cortex. Nat Neurosci 10, 549–551 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. P., Clark I. A., Zinn R. & Vissel B. Microglia: a new frontier for synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, and neurodegenerative disease research. Neurobiol Learn Mem 105, 40–53 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammation. Glia 61, 71–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao V. Y. et al. Motor Learning Consolidates Arc-Expressing Neuronal Ensembles in Secondary Motor Cortex. Neuron 86, 1385–1392 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra H. G. et al. RORalpha-mediated Purkinje cell development determines disease severity in adult SCA1 mice. Cell 127, 697–708 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu T. et al. Recovery from polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration in conditional SCA1 transgenic mice. J Neurosci 24, 8853–8861 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J. A. et al. Abnormalities in the climbing fiber-Purkinje cell circuitry contribute to neuronal dysfunction in ATXN1[82Q] mice. J Neurosci 31, 12778–12789 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan F., Aldridge G. M., Greenough W. T. & Gan W. B. Dendritic spine instability and insensitivity to modulation by sensory experience in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 17768–17773 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki M. et al. Enhanced synapse remodelling as a common phenotype in mouse models of autism. Nature communications 5, 4742 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takagi A. et al. PAKs inhibitors ameliorate schizophrenia-associated dendritic spine deterioration in vitro and in vivo during late adolescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 6461–6466 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J., Bakes J., Bradley C., Collingridge G. L. & Kaang B. K. Shank mutant mice as an animal model of autism. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 369, 20130143 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussignol G. et al. Shank expression is sufficient to induce functional dendritic spine synapses in aspiny neurons. J Neurosci 25, 3560–3570 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J., Grutzendler J., Duff K. & Gan W. B. Fibrillar amyloid deposition leads to local synaptic abnormalities and breakage of neuronal branches. Nat Neurosci 7, 1181–1183 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murmu R. P., Li W., Holtmaat A. & Li J. Y. Dendritic spine instability leads to progressive neocortical spine loss in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci 33, 12997–13009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. & Lu B. Synapses and dendritic spines as pathogenic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Plast 2012, 247150 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithianantharajah J. & Hannan A. J. Dysregulation of synaptic proteins, dendritic spine abnormalities and pathological plasticity of synapses as experience-dependent mediators of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Neuroscience 251, 66–74 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Popovic N. & Brundin P. The use of the R6 transgenic mouse models of Huntington’s disease in attempts to develop novel therapeutic strategies. NeuroRx: the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics 2, 447–464 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulley S. J., Drew C. J. & Morton A. J. Direct Visualisation of Abnormal Dendritic Spine Morphology in the Hippocampus of the R6/2 Transgenic Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Journal of Huntington’s disease 1, 267–273 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapstein G. J. et al. Electrophysiological and morphological changes in striatal spiny neurons in R6/2 Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Journal of neurophysiology 86, 2667–2677 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires T. L. et al. Dendritic spine pathology and deficits in experience-dependent dendritic plasticity in R6/1 Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci 19, 2799–2807 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithianantharajah J., Barkus C., Vijiaratnam N., Clement O. & Hannan A. J. Modeling brain reserve: experience-dependent neuronal plasticity in healthy and Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry 17, 196–209 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockers T. M. et al. Differential expression and dendritic transcript localization of Shank family members: identification of a dendritic targeting element in the 3' untranslated region of Shank1 mRNA. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 26, 182–190 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfi S. et al. Cloning and developmental expression analysis of the murine homolog of the spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 gene (Sca1). Hum Mol Genet 5, 33–40 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung A. Y. et al. Smaller dendritic spines, weaker synaptic transmission, but enhanced spatial learning in mice lacking Shank1. J Neurosci 28, 1697–1708 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M. K. et al. The postsynaptic density proteins Homer and Shank form a polymeric network structure. Cell 137, 159–171 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C. et al. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology and synaptic function by Shank and Homer. Neuron 31, 115–130 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J. C. et al. Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron 23, 583–592 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumatsu N., Matsuzaki M., Miyazaki T., Noguchi J. & Kasai H. Principles of long-term dynamics of dendritic spines. J Neurosci 28, 13592–13608 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Antalffy B., Kang D., Orr H. T. & Zoghbi H. Y. Polyglutamine expansion down-regulates specific neuronal genes before pathologic changes in SCA1. Nat Neurosci 3, 157–163 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra H. G. et al. Gene profiling links SCA1 pathophysiology to glutamate signaling in Purkinje cells of transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet 13, 2535–2543 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G. et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 28, 41–51 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley C. S. & McEwen B. S. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci 12, 2549–2554 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Pan F., Parkhurst C. N., Grutzendler J. & Gan W. B. Thinned-skull cranial window technique for long-term imaging of the cortex in live mice. Nat Protoc 5, 201–208 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]