Abstract

Objective

Ovarian clear cell carcinomas (OCCC) are rare, and uncertainty exists as to the optimal treatment paradigm and validity of the FIGO staging system, especially in early-stage disease.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all OCCC patients diagnosed and treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between January 1996 and December 2013. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were calculated by stage and race, and comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Type and duration of treatment were also recorded.

Results

There were 177 evaluable patients. The majority of patients were stage I at diagnosis (110/177, 62.2%). Of these, 60/110 (54.6%) were stage IA, 31/110 (28.2%) were stage IC on the basis of rupture-only, and 19/110 (17.3%) were stage IC on the basis of surface involvement and/or positive cytology of ascites or washings. Patients with stage IA and IC based on rupture-only had similar PFS/OS outcomes. Patients with stage IC based on surface involvement and/or positive cytology had a statistically significant decrement in PFS/OS. Stage was an important indicator of PFS/OS, while race was not.

Conclusions

OCCC often presents in early stage. Women with stage IA OCCC have excellent prognosis, and future studies should explore whether they benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Women with IC OCCC need further staging clarification, as surgical rupture alone affords better prognosis than surface involvement and/or positive cytology. Women with advanced OCCC have poor survival and are often chemotherapy resistant/refractory. New treatment paradigms are needed.

Keywords: clear cell, ovarian cancer, overall survival, progression-free survival, FIGO staging

INTRODUCTION

The histologic subtypes of ovarian cancer include high grade serous, clear cell, endometrioid, mucinous, and low grade serous. Each subtype is a distinct disease with a different biology [1]. Ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC) is rare, accounting for approximately 5–10% of all ovarian carcinomas in North America, and a higher percentage in East Asia [2,3]. It typically occurs at a younger age, is diagnosed at an earlier stage, and often is associated with endometriosis [3–5]. Because it is often discovered at an early stage, the overall prognosis is good, as women with stage I disease have an excellent outcome [6]; however, women with advanced OCCC tend to have a much worse prognosis than those with high grade serous carcinomas (HGSC) of equivalent stage [7, 8].

The difference in prognosis has been attributed primarily to the chemoresistant nature of OCCC. Although the standard treatment remains debulking surgery followed by chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin, controversy exists as to the role of chemotherapy for stage IA disease, the most effective chemotherapy regimen, the number of cycles, and the role of radiation therapy. Several trials have attempted to address these questions.

The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) conducted a randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin in early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) [9]. While there was no statistically significant difference in recurrence rate between the two groups, an exploratory analysis broken down by histology showed a significant risk reduction for receiving six cycles in the serous subtype [10]. On the other hand, this difference was not observed for OCCC, raising the question of the efficacy and optimal number of cycles of upfront chemotherapy.

The Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG) performed a randomized phase III trial (JGOG3017) of paclitaxel/carboplatin versus irinotecan/cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with stage IC-IV OCCC. No differences in 2-year progression-free (PFS) or overall survival (OS) were seen [11]. Of note, 66.4% of patients enrolled on this study had stage I disease and, accordingly, the event rate was low.

A retrospective Canadian study examined women with stage I and II OCCC treated with paclitaxel and carboplatin for three cycles, followed by abdominopelvic irradiation or observation [6]. They found that the addition of radiotherapy did not offer any benefit for patients with stage IA and IC (rupture-only). However, for stage IC patients with surface involvement or positive cytology and stage II patients, the addition of radiotherapy improved disease-free survival by 20% at 5 years.

Given the fundamental questions remaining in OCCC, more information about this rare subtype is needed. We conducted a retrospective systematic review of all OCCC cases diagnosed and treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) over an 18-year period.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board permission was obtained for this study. Patients were identified through the institutional database. The medical records of all women treated for ovarian or pelvic clear cell carcinoma at MSK between January 1996 and December 2013 were reviewed. Data collected included demographic information; clinical, surgical, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy information; and dates and nature of follow-up. All patients were restaged using the FIGO 2014 staging system, and women with stage IC disease were further broken down into intraoperative rupture vs. surface involvement and/or positive cytology and/or ascites (hereafter referred to as surface involvement). Women with both surgical rupture and surface involvement were counted in the surface involvement subgroup. Racial information was captured through both the patient registration system and the Cancer Database, a tumor registry run by MSK.

Only primary patients treated at MSK were included. For inclusion, a gynecologic pathologist at MSK must have confirmed the histologic diagnosis of ovarian or pelvic clear cell carcinoma. Initial debulking surgery may have been at MSK or elsewhere, as long as women had their upfront chemotherapy at MSK within three months of diagnosis. Women who presented to MSK at time of recurrence were excluded. Women with a concurrent advanced malignancy were also excluded, as were women with only pathology review or lack of sufficient follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

The associations between the type/response of chemotherapy treatment and stage were tested using the Fisher-Exact test. The endpoints selected for analysis included PFS and OS. PFS was defined as the time from histologic diagnosis to the date of progression or recurrence, death, or last follow-up. OS was defined as the time from histologic diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Comparisons were performed using the Log-Rank test.

Response to chemotherapy was broken down into refractory (progression within 1 month of chemotherapy), resistant (progression between 1–6 months of chemotherapy), and sensitive (progression after 6 months of chemotherapy).

RESULTS

Patient and Disease Demographics

There were 227 women with a diagnosis of OCCC at MSK between January 1996 and December 2013 (Table 1). Thirty-nine patients presented at time of disease recurrence; 3 patients had no follow-up; 2 patients had pathological review only; 5 patients had a concurrent advanced stage malignancy; and 1 patient had mixed mucinous/clear cell histology, leaving 177 women for this analysis.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variable | All | % |

|---|---|---|

| All | 177 | |

|

| ||

| Age at Diagnosis | ||

| Median (Mean) | 53 (52.4) | |

| Range | 30–82 | |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 150 | 84.7 |

| East Asian | 14 | 7.9 |

| Indian | 8 | 4.5 |

| Black/Other | 5 | 2.8 |

|

| ||

| FIGO 2014 Stage | ||

| I | 110 | 62.2 |

| II | 17 | 9.6 |

| III | 39 | 22.0 |

| IV | 11 | 6.2 |

|

| ||

| Within the 110 stage I pts | ||

| IA | 60 | 54.6 |

| IC with rupture only | 31 | 28.2 |

| IC with surface involvement, positive washings, or ascites | 19 | 17.3 |

The median age at diagnosis was 53 (range, 30 – 82). As expected, early-stage disease predominated: 110 (62.2%) patients had stage I disease, 17 (9.6%) had stage II disease, 39 (22.0%) had stage III disease, and 11 (6.2%) had stage IV disease. Among the stage I patients, 60 (54.6%) had stage IA disease, and 50 (45.4%) had stage IC disease. Within the IC patients, 31 (62.0%) patients were staged as IC due to rupture-only, while 19 (38.0%) patients had surface involvement or positive cytology.

The majority (84.7%) of women were white, 14 (7.9%) were East Asian, 8 (4.5%) were Indian, and 5 (2.8%) were black. Race was self-reported.

Upfront Chemotherapy Treatment

Of the 176 women with available chemotherapy data, 170 (96.6%) underwent upfront chemotherapy, mostly with a platinum-agent and taxane, and 157 (89.2%) underwent more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy (Table 2A). There was no statistically significant difference between the stage and the number of cycles of chemotherapy received, although 11 (100.0%) women with stage IV disease underwent more than 3 cycles. When broken down by stage IA vs. IC, 51/60 (85.0%) of women with stage IA disease underwent more than 3 cycles, as compared to 46/49 (93.9%) of women with stage IC disease (Table 2B). Of the 157 women with more than 6 months of post-chemotherapy follow-up, 17 (10.8%) had refractory disease, 16 (10.2%) had resistant disease, and 124 (79.0%) met the criteria for sensitive disease. The true rate of platinum resistance is better represented by measuring the rate in advanced disease patients: 22/44 (50.0%) women with stage III/IV disease had chemotherapy-refractory or resistant disease, compared to 11/113 (9.7%) women with stage I/II disease (p<0.001), largely reflecting the high cure rate in early-stage disease.

Table 2A.

Cross table between stage and chemotherapy

| Chemo cycle # (1 missing) | Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | p-value* | |

| No chemo (0) | 4(3.7%) | 0(0%) | 2(5.1%) | 0(0%) | 0.933 |

| Chemo cycle #<3* | 8(7.3%) | 2(11.8%) | 3(7.7%)* | 0(0%) | |

| Chemo cycle #>3 | 97(89%) | 15(88.2%) | 34(87.2%) | 11(100%) | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy Treatment Status§ | |||||

| Refractory | 2(2.1%) | 2(12.5%) | 8(22.9%) | 5(55.6%) | <0.001 |

| Resistant | 5(5.2%) | 2(12.5%) | 7(20%) | 2(22.2%) | |

| Sensitive | 90(92.8%) | 12(75.0%) | 20(57.1%) | 2(22.2%) | |

p-values are obtained using Fisher-Exact test

Excluded are 7 with missing data and 13 with <6 months follow-up after end of chemotherapy

Table 2B.

Cross table between Stage I and chemotherapy (descriptive only)

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| IA | IC | |

| Chemo cycle # (1 missing) | ||

| No chemo (0) | 3(5%) | 1(2%) |

| Chemo cycle #=3 | 6(10%) | 2(4.1%) |

| Chemo cycle #>3 | 51(85%) | 46(93.9%) |

|

| ||

| Chemotherapy Treatment Status* | ||

| Refractory | 1(1.9%) | 1(2.3%) |

| Resistant | 1(1.9%) | 4(9.3%) |

| Sensitive | 52(96.3%) | 38(88.4%) |

Excluded are 5 with missing data and 8 with <6 months follow-up after end of chemotherapy

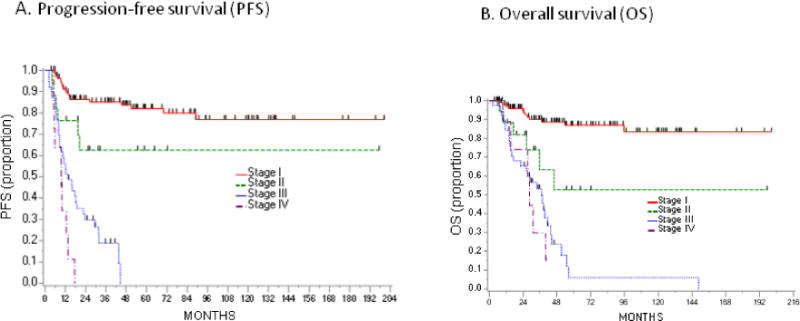

The overall 3-year PFS rate was 62.7% (95% CI: 54.7–69.7%), and 67 (37.9%) women progressed or died (Figure 1A). Median PFS was 9.7 months for stage IV, 13.8 months for stage III, and the median was not reached for stage I–II (Figure 2A). The median follow-up time for the non-progressed survivors was 47.9 months (range, 3.7–200.5 months).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis stratified by stage.

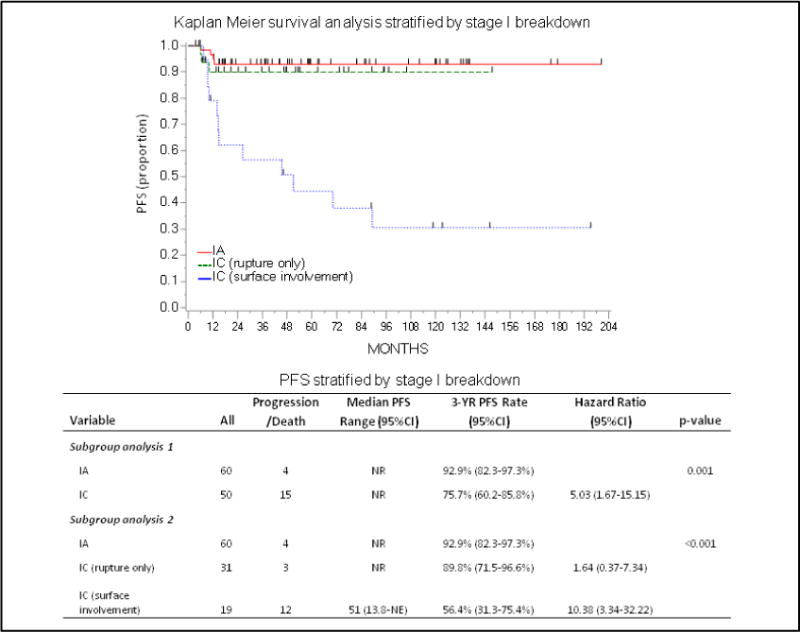

The 3-year PFS difference between IA (92.9%) and IC (75.7%) disease was statistically significant (HR 5.03, 95% CI: 1.67–15.15, p=0.001). The difference was further explored by subgroup analysis of stage I patients (Figure 4A), with a HR of 1.64 (95% CI: 0.37–7.34) for IC with surgical rupture-only, but a HR of 10.38 (95% CI: 3.34–32.2) for IC with surface involvement, compared to the IA group. Subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size. While some IA and IC rupture-only patients received 3 or fewer cycles of chemotherapy, all IC surface involvement patients received more than 3 cycles of chemotherapy.

Figure 4.

PFS and OS Stratified by Stage I Breakdown. Figure 4A. Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis (PFS) stratified by stage I breakdown. Figure 4B. Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis (OS) stratified by stage I breakdown.

Radiation Therapy

Two women underwent upfront radiation therapy. One of these women with stage IIIA1 disease (pelvic confined, with positive lymph nodes) underwent 5040 cGy to the pelvis with concurrent cisplatin (50 mg/m2 on days 1 and 29), followed by paclitaxel and carboplatin for 4 cycles. She has been disease-free since 2012. The second woman with stage IC (positive cytology) disease underwent the same regimen and recurred 4 months after completion of the chemotherapy.

There were four women who were treated with radiation for recurrent disease. Two of these women have no evidence of disease with 0.3 and 1.6 years of follow-up time. One patient who underwent pelvic RT had local control of her disease, but ultimately succumbed to distant metastases in the lung and mediastinum. The remaining patient received radiation therapy with palliative intent and went on to receive other lines of systemic chemotherapy and ultimately died of disease.

Overall Survival

For the entire cohort, the 3-year OS was 75.9% (95% CI: 68.1–82.1%), and 52 (29.4%) women died (Figure 1B). The prognosis for stage I was excellent, with a 3-year OS of 90.1%. The 3-year OS was 93.5% for IA and 85.9% for IC (HR 4.05, 95% CI: 1.09–14.96, p=0.02). Further subdivision of IC patients mirrored the PFS analysis (Figure 4B). Among patients with rupture-only, the 3-year OS was 96.2% (HR 1.53, 95% CI: 0.25–9.16), as compared to surface involvement, with a 3-year OS of 71.9% (HR 7.56, 95% CI: 1.95–29.3). The OS for advanced-stage disease was much poorer, with a 3-year OS rate of 53.3% (95% CI: 35.8–68.0%) for stage III patients, and 29.6% (95% CI: 4.3–62.5%) for stage IV patients (Figure 2B).

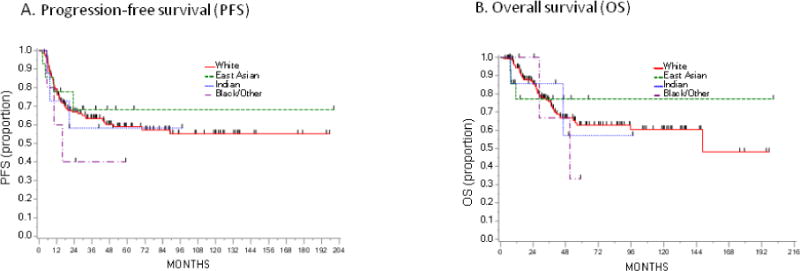

There was no difference in OS between whites and other races (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis stratified by race.

DISCUSSION

OCCC is a distinct disease entity from high grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC). We now know that most, if not all, HGSC originate in the fallopian tube from a lesion called ‘serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma,’ or STIC [12–15]. OCCCs, on the other hand, likely derive from endometriosis [16], and a study by Wiegand et al. [17] further confirmed this belief. They identified mutations in the tumor suppressor gene ARID1A in 55 of 119 OCCCs sequenced, and none in the 76 HGSC specimens analyzed. ARID1A has been implicated in the early transformation of endometriosis to cancer.

Of our 177 patients, 127 (71.8%) had stage I or II disease. This is in line with prior studies [4,18,19] but very different from HGSC, in which the majority of women present with advanced stage disease. Part of the difference may be due to the propensity of OCCC to present as a large unilateral pelvic mass, while early peritoneal dissemination is common in HGSC.

The treatment paradigm for OCCC remains unclear. In this large retrospective study, we showed that there is significant variation in prognosis for women with stage I disease. The 3-year OS rate of 90.1% for stage I patients is consistent with previous studies, and similarly, the worse prognosis for stage IC (3-year OS rate 85.9% vs. 93.5% for stage IA) has also been described [3,7,20,21]. There is debate as to whether or not intraoperative rupture confers a worse prognosis than that seen in stage IA patients [22,23]. In our cohort, rupture-only patients had a better survival compared to those with stage IC for other reasons, and the survival for stage IA and IC rupture-only was statistically similar. The prognostic implications of intraoperative rupture remain unclear. We suggest maintaining sound surgical principles and making all efforts to remove highly suspicious adnexal masses intact, whether these cases are performed through laparotomy or minimally invasive approaches.

Certainly, having surface involvement, ascites, or positive cytology appears to confer a less favorable outcome for stage IC patients. This is consistent with prior reports [6,20,21] showing that survival rates for IC rupture-only were similar to stage IA/IB patients, whereas the remaining IC patients had much lower survival rates. This difference in survival could point towards a shift in treatment paradigm based on the IC stratification.

While GOG 157 did not demonstrate a difference between 3 vs. 6 cycles of chemotherapy for early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer as a whole, a subgroup analysis by histology did show a difference for the serous histologies [10]. We now know that the different histologic types of ovarian cancer (high grade serous, clear cell, endometrioid, mucinous, and low grade serous), should ideally be considered separately. Our data add to the existing body of literature showing that patients with stage IA (no rupture, no surface involvement, and negative cytology) OCCC have a greater than 90% disease-free survival after surgery and chemotherapy. What we do not know is whether this can be achieved with surgery alone. Of the 110 patients with stage I disease in our study, only 3 did not receive chemotherapy, limiting our ability to analyze this question. In a small cohort, Mizuno et al. [21] noted a 95.2% 5-year disease-free survival in stage IA patients who did not receive chemotherapy. Further study is needed to define the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage OCCC.

We did not observe enough women treated with radiation to form conclusions about its efficacy. However, the report by Hoskins et al. [6] demonstrated an apparent benefit from radiation in women with stage IC surface involvement and stage II OCCC, with a 20% improvement in disease-free survival at 5 years. These data, along with the adverse survival for these women shown in this report, suggest that radiation should be considered in high-risk early-stage disease. Whole abdominal radiation therapy is no longer in broad use, although concurrent chemoradiation therapy (as is being used in PORTEC3 and GOG 158) is more tolerable and remains a viable, and potentially more efficacious, option.

The median OS for advanced stage disease is quite poor. Stage III and IV patients have OS of 37.0 and 28.7 months, respectively. In GOG 172 [24], the OS for women with stage III disease receiving intravenous chemotherapy was 49.7 months. Chan et al. showed in their large SEER analysis that the 5-year disease-specific survival of OCCC patients was worse compared to HGSC, stage for stage, but most pronounced in the advanced stages [7].

Because OCCC occurs more commonly in the East Asian population, we were interested in seeing whether or not race plays a role in survival. No particular race (East Asian, Indian, Black/Other) conferred a survival advantage or disadvantage, but these estimates are limited by small numbers. Furthermore, ethnicity was not taken into account, and therefore Hispanic patients, for example, may have self-reported as Black/Other or White.

There are limitations to this study. Because MSK is a large referral center, many of the patients received their primary debulking surgery elsewhere, and although charts were carefully reviewed, some treatment details had to be extrapolated from physician notes. By only including primary MSK patients, and not patients who presented at time of recurrence, we reduced ascertainment and referral bias. Furthermore, although the majority of patients underwent treatment with paclitaxel and carboplatin at standard doses, many underwent alternative regimens and dosing schedules, making it difficult to determine the optimal regimen.

Given its inherent chemoresistant nature, perhaps the answer for OCCC lies in targeted therapies. At MSK, we are performing broad, hybrid capture-based next-generation sequencing on cancers that recur, in hopes of finding actionable mutations. Kuo et al. published a series of 97 OCCCs [25] that were sequenced for KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, TP53, PTEN, and CTNNB1, and found a mutation rate of 33% in PIK3CA but only 15% in TP53. This is in contrast to HGSCs, which are characterized by frequent mutations of TP53 – up to 96% as reported in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [26]. A trial of NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, showed promise in OCCC cell lines [27], and may warrant further investigation. There is an ongoing phase II GOG trial for dasatinib (GOG 283) in recurrent/persistent OCCC and endometrial CCC characterized for retention or loss of BAF250a expression, a protein encoded by ARID1A. Finally, immunotherapy is another frontier that warrants exploration. At the ASCO 2015 conference, several studies explored the role of PD-1 and PD-L1 in OCCC, with a study of avelumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) demonstrating response in 2 of 2 clear cell patients [28].

In this retrospective analysis, we confirmed that early-stage OCCC has a favorable prognosis, but also that there is wide variation not only among stage I subdivisions, but even within stage IC disease. One should be conscious about specifying the reason for upstaging to IC, whether it is from rupture-only, or due to surface involvement and/or positive washings, as the latter confers a significant adverse effect on prognosis. For more locally advanced disease, the use of radiation therapy should be considered more regularly. Given the poor prognosis of advanced stage disease, we are in need of new therapies, and hope that with further molecular characterization of this disease, and rational development of novel targeted therapeutics, we will be able to make progress on that front.

Research Highlights.

Clear cell ovarian carcinoma frequently presents at an early stage.

Women with stage IA disease have an excellent prognosis.

Survival for IC disease varies based on surgical rupture vs. surface involvement

Acknowledgments

Financial Support:

This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center’s core grant P30 CA008748. The core grant provides funding to institutional cores such as Biostatistics, which was used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Bookman MA, Gilks CB, Kohn EC, Kaplan KO, Huntsman D, Aghajanian C, et al. Better therapeutic trials in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(4):dju029. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan DS, Kaye S. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma: a continuing enigma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:355–60. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugiyama T, Kamura T, Kigawa J, Terakawa N, Kikuchi Y, Kita T, et al. Clinical characteristics of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a distinct histologic type with poor prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer. 2000;88:2584–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behbakht K, Randall TC, Benjamin I, Morgan MA, King S, Rubin SC. Clinical characteristics of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:255–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crozier MA, Copeland LJ, Silva EG, Gershenson DM, Stringer CA. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a study of 59 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoskins PJ, Le N, Gilks B, Tinker A, Santos J, Wong F, et al. Low-stage ovarian clear cell carcinoma: population-based outcomes in British Columbia, Canada, with evidence for a survival benefit as a result of irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1656–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JK, Teoh D, Hu JM, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. Do clear cell ovarian carcinomas have poorer prognosis compared to other epithelial cell types? A study of 1411 clear cell ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tammela J, Geisler JP, Eskew PN, Jr, Geisler HE. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: poor prognosis compared to serous carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1998;19:438–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, Lage J, Walker JL, Look KY, et al. Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan JK, Tian C, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kapp DS, et al. The potential benefit of 6 vs. 3 cycles of chemotherapy in subsets of women with early-stage high-risk epithelial ovarian cancer: an exploratory analysis of a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:301–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okamoto A, Sugiyama T, Hamano T, Kim JW, Kim BG, Enomoto T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel/carboplatin (PC) versus cisplatin/irinotecan (CPT-P) as first-line chemotherapy in patients with clear cell carcinoma (CCC) of the ovary: A Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG)/GCIG study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:5s. (suppl; abstr 5507) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R, Sehdev AS, Han G, Soslow R, et al. TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma–evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol. 2012;226:421–6. doi: 10.1002/path.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, Jansen JW, Poort-Keesom RJ, Menko FH, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed Fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195:451–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, Kindelberger DW, Elvin JA, Garber JE, et al. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3985–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, Hirsch MS, Feltmate C, Medeiros F, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:161–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ness RB. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: thoughts on shared pathophysiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:280–94. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, Zhao Y, Tse K, Zeng T, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1532–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Huntsman DG, Santos JL, Swenerton KD, Seidman JD, et al. Differences in tumor type in low-stage versus high-stage ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:203–11. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181c042b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skirnisdottir I, Seidal T, Karlsson MG, Sorbe B. Clinical and biological characteristics of clear cell carcinomas of the ovary in FIGO stages I–II. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takano M, Kikuchi Y, Yaegashi N, Kuzuya K, Ueki M, Tsuda H, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a retrospective multicentre experience of 254 patients with complete surgical staging. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1369–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizuno M, Kikkawa F, Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Suzuki T, Ino K, et al. Long-term prognosis of stage I ovarian carcinoma. Prognostic importance of intraoperative rupture. Oncology. 2003;65:29–36. doi: 10.1159/000071202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajiyama H, Mizuno M, Shibata K, Umezu T, Suzuki S, Yamamoto E, et al. A recurrence-predicting prognostic factor for patients with ovarian clear-cell adenocarcinoma at reproductive age. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19(5):921–7. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashi M, Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Mizuno M, Mizuno K, Hosono S, et al. Survival impact of capsule rupture in stage I clear cell carcinoma of the ovary in comparison with other histological types. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:474–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, Lele S, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo KT, Mao TL, Jones S, Veras E, Ayhan A, Wang TL, et al. Frequent activating mutations of PIK3CA in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1597–601. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Cancer Genome Research Group. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oishi T, Itamochi H, Kudoh A, Nonaka M, Kato M, Nishimura M, et al. The PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 reduces the growth of ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:553–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Disis ML, Patel MR, Pant S, Infante JR, Lockhart AC, Kelly K, et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C), an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with previously treated, recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: A phase Ib, open-label expansion trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33 (15 suppl; abstr 5509) [Google Scholar]