Abstract

Purpose of the review

We review and offer our clinical perspectives on the emergence of echinocandin-resistant Candida.

Recent findings

Candida FKS gene mutations attenuate echinocandin activity, but overall mutation rates among clinical isolates remain low (C. glabrata, ∼4%; other species, <1%). Rates are higher with prior echinocandin exposure, exceeding 50% among C. glabrata or C. albicans isolates causing breakthrough invasive candidiasis. The median duration of prior echinocandin exposure among FKS mutant isolates is ∼100 days. The clinical usefulness of echinocandin susceptibility testing is limited by the low overall prevalence of resistance, and uncertainties surrounding testing methods and interpretation of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). In single-center studies, caspofungin resistance (defined using institution-specific MIC breakpoints) was 32-53% sensitive and 75-95% specific for predicting treatment outcomes of C. glabrata invasive candidiasis; corresponding values for the presence of an FKS mutation were 35-41% and 90-98%. Results were similar using anidulafungin and micafungin MICs. Clinical data are scarce for non-C. glabrata species.

Summary

Echinocandins remain preferred agents against invasive Candida infections. Susceptibility testing and FKS genotypic testing do not have roles in routine clinical practice, but may be useful in newly-diagnosed patients who are echinocandin-experienced or those who have not responded to echinocandin treatment.

Keywords: Echinocandin, Candida, FKS mutation, resistance, susceptibility testing

Introduction

Echinocandin antifungals (anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin) are agents of choice for the treatment of invasive candidiasis [1-3]. The drugs exert fungicidal activity against Candida species in vitro by inhibiting the synthesis of β-1,3-Dglucan, a major cell wall constituent [4]. Although there are some pharmacokinetic differences among the agents, practice guidelines consider the echinocandins to be interchangeable [1,2].

Widespread echinocandin usage has been accompanied by reports of emerging drug resistance among clinical Candida isolates, particularly among the haploid species C. glabrata [5,6]. While these reports are worrisome, uncertainty surrounds the extent and clinical significance of echinocandin-resistant Candida. Moreover, methods for detecting resistance, the roles of resistance testing in clinical practice, and the impact of emerging resistance on the management of invasive candidiasis are unclear. In this article, we review echinocandin resistance among Candida species and offer our clinical perspectives on the phenomenon.

FKS mutations among Candida species

The catalytic subunit of the echinocandin target enzyme, β-1,3-D-glucan synthase, is encoded by FKS1, FKS2 and FKS3 genes. Mutations in hot spot regions of FKS1 (all Candida species) or FKS2 (C. glabrata) result in amino acid substitutions that attenuate echinocandin activity [7]. Echinocandin inhibition of β-1,3-D-glucan synthase is reduced by 30- to several thousand-fold in isolates harboring FKS mutations [8-10]. Readers interested in the impact of specific FKS mutations on echinocandin susceptibility are referred to a recent review [7].

Five Candida species account for >95% of invasive candidiasis. Among these species, C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis and C. krusei can acquire FKS mutations under selection pressure. Certain acquired FKS mutations result in highly-attenuated susceptibility in vitro, which correlates with poor treatment responses in mouse models of disseminated candidiasis [7-9,11-14]. C. parapsilosis, in contrast, harbors a naturally-occurring FKS1 polymorphism that confers diminished echinocandin susceptibility [10], the clinical significance of which is not established [15-17].

The prevalence of FKS mutant Candida is not precisely defined (Table 1) [5,18-28]. Reported rates of 8–18% among C. glabrata isolates at certain high-risk centers may overstate prevalence since studies have been limited by incomplete access to medical records and/or a lack of systematic testing across consecutive isolates [5,19,20]. In a more recent study of 453 consecutive Candida bloodstream isolates from a single center, FKS mutations were detected in only 4% and <1% of C. glabrata and C. albicans, respectively [29]. These low rates are in general agreement with data from international repositories [18,30,31]. FKS mutant C. tropicalis and C. krusei been described in case reports [22,24-28], but rates among repository strains are low [18].

Table 1. Rates of acquired FKS mutations among Candida isolates causing invasive infections.

| Species | Overall | Any prior echinocandin exposure1 | Echinocandin breakthrough candidiasis | Echinocandin resistance among FKS mutants2 | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 1 – 3% | 5% | 50% | Approaching 100% | [18] |

| C. glabrata | 4 – 18% | 15 - 32% | 67 - 75% | 46 - 81% | [5, 18-23] |

| C. krusei | Case reports* | NA | NA | NA | [22, 24, 25] |

| C. tropicalis | Case reports* | NA | NA | NA | [22, 26-28] |

Insufficient data to determine rates; NA = Not available

Includes remote exposure and ongoing exposure at time of breakthrough infections

As defined by echinocandin-specific CLSI breakpoints

It is important to understand that FKS mutations arise in specific clinical settings, within which echinocandin resistance rates are significantly higher than in the broader population with invasive candidiasis. Most notably, FKS mutant C. glabrata and C. albicans are recovered almost exclusively from patients with prior echinocandin exposure [5,19-21]. The greatest risk is among patients who develop breakthrough infections during treatment, in whom ≥50% of C. glabrata or C. albicans isolates harbor mutations (Table 1) [22,32]. In contrast, FKS mutant isolates account for <10% of C. glabrata or C. albicans infections among patients with remote echinocandin exposure [29]; risk is greatest for exposure within the preceding month [19].

In both breakthrough and remote settings, prolonged echinocandin exposure is typically required for emergence of mutations (median: ∼100 days; range: 7–450 days) [20,21,29,32]. By the same token, infections by wild-type C. glabrata have been reported after as many as 84 treatment days [21,22,29,32]. Other risk factors for FKS mutant C. glabrata include underlying gastrointestinal disorders, solid organ transplantation and recurrent invasive candidiasis [5,19,20,32]. Of note, ≥25% of FKS mutant C. glabrata may also exhibit fluconazole and/or amphotericin B resistance [5,23,29,33,34], in keeping with past exposure to multiple antifungal drug classes. Less is known about the emergence of FKS mutations among non-C. glabrata species, but it is likely that risk factors are similar. Breakthrough infections with C. parapsilosis are well-recognized [22,29], but acquired FKS hot spot mutations are not described.

Some FKS mutations may confer differential resistance to individual echinocandins [7,12], but agent-specific mutants are extremely rare [29]. The extent to which echinocandin resistance in Candida is mediated by FKS mutations versus other, less well-characterized mechanisms is not established. In a recent study, 25% of C. glabrata isolates that were resistant to multiple echinocandins did not harbor an FKS mutation [29].

Echinocandin susceptibility testing

At present, most hospital microbiology laboratories do not have the capacity to detect FKS mutations [35-37]. Echinocandin susceptibility is typically assessed by measuring minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), and comparing results to interpretive clinical breakpoints. Reference broth microdilution methods for testing echinocandins against Candida species have been developed by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [38] and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [39]. Drug- and species-specific breakpoints have been derived from data on MIC distributions, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) parameters, epidemiological cut-off values (ECVs), and, to a lesser extent, patient responses to echinocandin treatment (Table 2) [40,41]. MICs and clinical breakpoints are higher for C. parapsilosis than other species, in keeping with intrinsic FKS polymorphisms. A prominent limitation of echinocandin susceptibility testing is that CLSI and EUCAST clinical breakpoints often differ. Discrepancies in clinical breakpoints are one of several major issues that make the interpretation of echinocandin MICs difficult in the clinic.

Table 2. Clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cut-off values for echinocandins against Candida1.

| Agent | Species | MIC breakpoint (μg/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSI | EUCAST2 | ECV3 | |||||

| S | I | R | S | R | |||

| Anidulafungin | C. albicans | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | ≤ 0.03 | ≥ 0.06 | 0.12 |

| C. glabrata | ≤ 0.12 | 0.25 | ≥ 0.5 | ≤ 0.06 | ≥ 0.12 | 0.25 | |

| C. krusei | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | ≤ 0.06 | ≥ 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| C. parapsilosis | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | ≤ 0.002 | > 4 | 4 | |

| C. tropicalis | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | ≤ 0.06 | ≥ 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Caspofungin | C. albicans | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | Breakpoints have not been established due to significant inter-laboratory variation in MIC ranges for caspofungin | 0.12 | |

| C. glabrata | ≤ 0.12 | 0.25 | ≥ 0.5 | 0.12 | |||

| C. krusei | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | 0.25 | |||

| C. parapsilosis | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | 1 | |||

| C. tropicalis | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | 0.12 | |||

| Micafungin | C. albicans | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | ≤ 0.016 | ≥ 0.03 | 0.03 |

| C. glabrata | ≤ 0.06 | 0.12 | ≥ 0.25 | ≤ 0.03 | ≥ 0.06 | 0.03 | |

| C. krusei | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | IE | IE | 0.12 | |

| C. parapsilosis | ≤ 2 | 4 | ≥ 8 | ≤ 0.002 | > 2 | 4 | |

| C. tropicalis | ≤ 0.25 | 0.5 | ≥ 1 | IE | IE | 0.12 | |

S = Susceptible, I = Intermediate, R = Resistant, IE = Insufficient evidence

Data are presented for five Candida species that account for >95% of invasive candidiasis.

An intermediate classification is not provided, but it is designated for values between the susceptible and resistant breakpoints.

Epidemiological cut-off value (ECV), as defined using CLSI reference broth microdilution methods. ECV is the highest endpoint of the MIC distribution of the wild type population, as established using MIC distributions from multiple laboratories. Epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs) also have been proposed for anidulafungin by EUCAST [41], but they are not presented here to maintain clarity.

Shortly after CLSI proposed interpretive criteria, it became apparent that caspofungin MICs varied significantly among laboratories using broth microdilution methods. Results of a large international study showed that modal caspofungin MICs generated in individual laboratories by either of the reference methods differed by ≥4 two-fold dilutions against C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis and C. krusei [42]. In contrast, modal anidulafungin and micafungin MICs were distributed within narrow ranges. Given these data, EUCAST has not proposed caspofungin breakpoints, and recommends against testing this agent [41,43]. Variability in caspofungin MICs is most relevant for C. glabrata, as rates of non-susceptibility approach 100% at some centers applying CLSI breakpoints [20,44].

The overall clinical impact of caspofungin MIC variability is somewhat mitigated by the fact that an overwhelming majority of hospitals do not use reference broth microdilution methods, but rather commercialized assays such as Sensititre YeastOne (SYO, Trek Diagnostics, Cleveland, United States) and Etest (Biomerieux, Marcy-I'Etoile, France), or automated systems like Vitek 2 (Biomerieux) [45,46]. Echinocandin MICs generated by these methods and reference methods demonstrate good essential agreement (MICs within a two-fold dilution), but categorical agreement (defining isolates as susceptible, intermediate or resistant) using reference breakpoints may be lower [47,48]. In a recent study of hospitals that routinely perform susceptibility testing, inter-laboratory modal echinocandin MICs obtained by SYO (including those of caspofungin) were within a single two-fold dilution against each Candida species [45]. However, the use of CLSI breakpoints resulted in disproportionately high rates of caspofungin nonsusceptibility among C. glabrata and C. krusei, compared to other agents. In a follow-up study at one of the hospitals, FKS mutations were not detected among isolates that were non-susceptible to caspofungin but susceptible to other agents [29]. Therefore, commercialized assays like SYO may reduce the inter-laboratory variation in caspofungin MICs seen with reference methods; at the same time, CLSI and EUCAST interpretive criteria may not be valid in classifying MICs generated by these assays, particularly for caspofungin.

The distinction between clinical breakpoints and ECVs is another issue of confusion for many clinicians. Clinical breakpoints assign MICs at which the likelihood of treatment failure is increased, and thus they are designed to predict patient outcomes. An ECV, on the other hand, distinguishes between a population of wild-type, drug-susceptible isolates and a population that includes non-wild-type isolates with acquired resistance mechanisms. To this end, the ECV is designed to be a sensitive surveillance tool for detecting emergence of resistance. As in the case of the echinocandins, clinical breakpoint MICs and ECVs may not agree (Table 2) [49,50]. In prioritizing sensitivity to detect resistant mutants, ECVs may sacrifice the specificity needed to be useful clinically; at the same time, some mutations confer low-level resistance that does not impact treatment responses. Echinocandin ECVs are sensitive at detecting FKS mutant Candida [50,51], but it does not necessarily follow that they are useful in guiding treatment.

In fact, correlations between echinocandin MICs and treatment responses remain uncertain. In a comprehensive investigation of 746 Candida isolates from 6 caspofungin treatment studies for esophageal (4 trials; 515 isolates) or invasive candidiasis (2 trials; 231 isolates), there was no correlation between caspofungin MICs (as determined by broth microdilution) and patient outcomes [44]. Upon closer consideration, these results are not necessarily surprising since studies did not include patients with prior echinocandin exposure. Indeed, the absence of associations between MICs and outcomes in patients at low-risk for resistance highlights that microbiologic resistance is not the sole determinant of treatment response. For invasive candidiasis, factors like underlying disease, host immune function, severity of illness, source control, time to initiation of treatment, PK-PD parameters and isolate fitness may play more significant roles in a given patient than antifungal susceptibility [52]. Studies seeking to demonstrate correlations between echinocandin MICs and outcomes should include patients from high-risk populations in which resistance is most likely to emerge.

Echinocandin MICs, FKS mutations and treatment outcomes

Several single-center studies have investigated MICs and FKS mutations as potential risk factors for echinocandin treatment failures among patients with invasive candidiasis. At three centers using various testing methods and either CLSI or institution-specific, receiver operator characteristic (ROC)-derived breakpoints, treatment failure rates among patients with invasive infections due to caspofungin-resistant or FKS mutant C. glabrata were 47%-79% and 60-90%, respectively (Table 3) [5,19-21,53]. Caspofungin resistance was 32-53% sensitive (percentage of patients in whom treatment failed who were infected with resistant isolates) and 75-95% specific (percentage of patients in whom treatment was successful who were infected with non-resistant isolates). The corresponding sensitivity and specificity for the presence of an FKS mutation were 35–41% and 90–98%, respectively [5,19-21]. In a study of cancer patients with C. glabrata candidemia that did not assess FKS mutations, caspofungin MICs determined by CLSI broth microdilution were inversely related to 28-day all-cause mortality (P=0.001); mortality rates among patients infected with resistant and non-resistant C. glabrata isolates by CLSI breakpoints were 57% (8/14) and 28% (22/79), respectively [34]. Caspofungin resistance or the presence of an FKS mutation was an independent risk factor for treatment failure in some, but not all of these studies [5,19-21,34,54].

Table 3. Factors associated with echinocandin treatment failure for C. glabrata invasive candidiasis.

| Study (reference) | Variable associated with echinocandin treatment failure | Rate of failure | P-value | Multivariate P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Shields et al. 2012 [20] | Caspofungin MIC > 0.5 μg/mL (BMD) | 60% (6/10) | 0.009 | NS |

|

|

||||

| Presence of FKS mutation | 86% (6/7) | 0.0004 | 0.002 | |

|

|

||||

| Prior echinocandin exposure | 54% (7/13) | 0.008 | NS | |

|

|

||||

| GI surgery within 30 days | 42% (8/19) | 0.031 | NS | |

|

|

||||

| Shields et al. 2013 [21] | Caspofungin MIC > 0.25 μg/mL (Etest) | 79% (11/14) | 0.0001 | -- |

|

|

||||

| Presence of FKS mutation | 90% (9/10) | 0.0001 | -- | |

|

|

||||

| Prior echinocandin exposure | 62% (13/21) | 0.002 | -- | |

|

|

||||

| Shields et al. 2013 [53] | Anidulafungin MIC > 0.12 μg/mL (BMD) | 83% (5/6) | 0.014 | -- |

|

|

||||

| Micafungin MIC > 0.06 μg/mL (BMD) | 55% (6/11) | NS | -- | |

|

|

||||

| Alexander et al. 2013 [5] | Caspofungin MIC ≥ 0.5 μg/mL (BMD) | 73% (8/11) | NS | NS |

|

|

||||

| Micafungin MIC ≥ 0.25 μg/mL (BMD) | 75% (6/8) | NS | NS | |

|

|

||||

| Presence of FKS mutation | 62% (8/13) | 0.039 | NS | |

|

|

||||

| Beyda et al. 2014 [19] | Caspofungin MIC ≥ 0.25 μg/mL (SYO) | 47% (9/19) | 0.04 | NS |

|

|

||||

| Presence of FKS mutation | 60% (6/10) | 0.02 | NS | |

|

|

||||

| Echinocandin exposure within 60d | 73% (8/11) | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

|

|

||||

| Underlying GI disorder | 45% (14/31) | <0.01 | 0.04 | |

BMD = Broth microdilution; GI = Gastrointestinal; NS = Not significant; SYO = Sensititre YeastOne

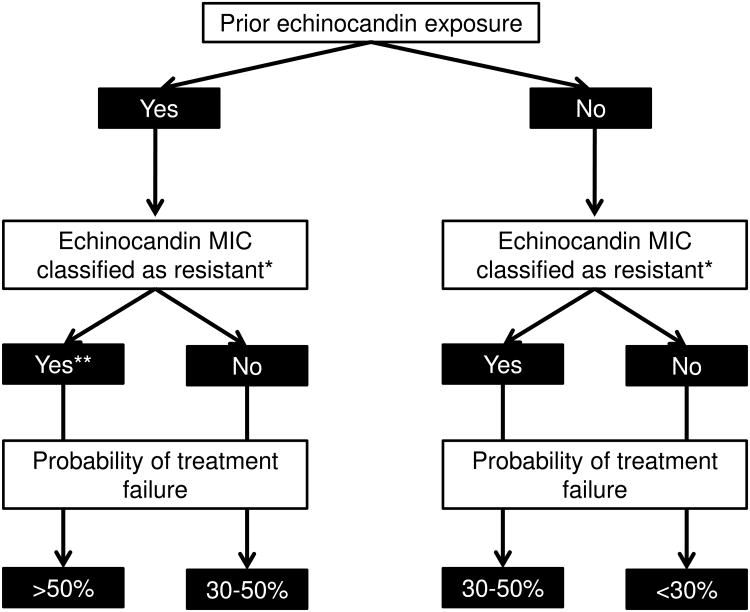

Prior echinocandin exposure likewise was associated with unsuccessful treatment of invasive C. glabrata infections in several studies [5,20], and implicated as an independent risk factor in one study [19]. Echinocandin exposure, FKS mutations and phenotypic resistance are inter-related factors, which complicates assessment of their relative contributions to outcomes. An elevated MIC in the setting of prior echinocandin exposure was a useful surrogate for the detection of FKS mutations among C. glabrata isolates at one center, and an algorithm that considered these factors accurately predicted treatment responses (Figure) [21,53].

Figure. An algorithm for predicting echinocandin treatment responses among patients with C. glabrata invasive candidiasis based on prior drug exposure and MICs.

The algorithm is based upon single-center data published for each of the echinocandins [21, 53]. Note that failure rates include unsuccessful treatment of newly-diagnosed invasive candidiasis and breakthrough infections. Rates are lower if only treatment of newly-diagnosed infections is considered.

* Resistance is classified according to institution-specific clinical breakpoints.

** Over 80% of FKS mutations are encountered in this arm.

Data are limited for infections due to species other than C. glabrata, and for associations between anidulafungin and micafungin MICs and treatment responses. Elevated echinocandin MICs and FKS mutations among C. albicans, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis isolates have been linked to unsuccessful therapy in individual cases [22,24,55-58]. In clinical trials, outcomes among patients treated with echinocandins for C. parapsilosis candidemia have not been impaired, despite higher MICs and intrinsic FKS polymorphisms [15-17]; conclusive data on deep-seated C. parapsilosis infections such as endocarditis are lacking. An association was demonstrated between caspofungin resistance, as determined by broth microdilution and CLSI breakpoints, and excess mortality among cancer patients with candidemia due to non-C. albicans species [54]; however, these findings were based largely on resistant C. glabrata. In another study that used CLSI broth microdilution methods and clinical breakpoints, anidulafungin and micafungin MICs were superior to caspofungin MICs in predicting caspofungin treatment outcomes among patients with invasive C. glabrata infections [53]. Of note, ROC-derived breakpoints for anidulafungin and micafungin performed better than CLSI breakpoints. Moreover, ROC-derived caspofungin breakpoints performed comparably to ROC-derived anidulafungin and micafungin breakpoints. For each of the agents, SYO or Etest MICs and ROC-derived breakpoints correlated with caspofungin treatment responses at least as well as broth microdilution MICs [21,53].

Perspectives on echinocandin resistance in clinical practice

Several conclusions from the published data on echinocandin resistance serve as a foundation for rational management strategies against invasive candidiasis: 1) FKS mutations remain rare among clinical Candida isolates; 2) Mutations are encountered almost exclusively among C. glabrata or C. albicans recovered from echinocandin treatment-experienced patients, most commonly during breakthrough infections; 3) Mutations are generally difficult to induce in clinical settings and typically require weeks to months of echinocandin exposure; 4) Most echinocandin treatment failures are not due to microbiologic resistance. Given these facts, we propose that echinocandins remain the preferred agents against the vast majority of invasive Candida infections, and susceptibility testing and/or screening for FKS mutations does not have a role in routine clinical practice.

For the subset of patients with echinocandin-breakthrough invasive candidiasis or infections following prolonged, remote drug exposure, a practical approach is to treat with an agent from an antifungal class for which the patient is treatment-naïve. This strategy is infeasible in a growing minority of echinocandin-experienced patients who have prior exposure to multiple antifungals. In such patients or in those with invasive candidiasis who do not respond to echinocandin treatment, susceptibility testing or FKS genotyping may be useful. At present, it is unclear if echinocandin MICs or FKS genotypes correlate more closely with treatment responses. Given uncertainties about susceptibility testing methods and precise clinical breakpoints, FKS mutations are easier to interpret; however, most hospital labs are not equipped to perform genotypic testing. An elevated echinocandin MIC in the context of prior drug exposure may be a useful proxy for the presence of an FKS mutation. Although MICs or FKS genotypes are not needed to manage most cases of invasive candidiasis, centers should test isolates for epidemiologic purposes and as surveillance for resistance.

Clinicians need to be aware of the susceptibility testing method employed in their hospital, and understand MIC distributions of individual echinocandins against common Candida species. Caspofungin MICs determined by broth microdilution and corresponding CLSI clinical breakpoints, in particular, may not be reliable. To place MIC results in some context, institutional MIC and resistance patterns for all agents should be compared to those published in the literature. Caspofungin MICs may be reliable at centers using SYO or other commercial assays, but local MIC distributions must be validated. If caspofungin MICs are skewed, anidulafungin or micafungin MICs may be used as surrogates for the class. This strategy is not satisfactory for the field in the long-term, however, as accurate caspofungin MICs are essential for determining differences in efficacy between agents, and for meaningful epidemiologic and PK-PD studies.

Conclusions

Echinocandin resistance among Candida species has emerged, and the challenges it poses to clinicians are likely to become more pronounced. As clinicians grapple with the issue, several questions merit immediate research investigation (Table 4). The emergence of echinocandin resistance has stemmed directly from the extensive use of these agents. Therefore, strict antifungal stewardship is the most powerful weapon for preserving echinocandin susceptibility.

Table 4. Pressing questions for research on echinocandin resistance among Candida species.

| Questions |

|---|

|

Key Points.

Mutations in hot spot regions of FKS genes lead to decreased echinocandin susceptibility among Candida species, but they remain uncommon outside of C. glabrata or C. albicans isolates recovered from patients with breakthrough infections or extensive drug exposure in the recent past.

The clinical utility of echinocandin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) measurements is limited by the low overall prevalence of resistant Candida isolates, and uncertainties about optimal testing methods, inter-laboratory reproducibility (particularly for caspofungin), resistance breakpoints, and correlations with responses to echinocandin treatment among patients with invasive candidiasis.

Most echinocandin treatment failures for invasive candidiasis are not due to drug resistance, but rather a combination of factors such as underlying disease, host immune function, severity of illness, source control, time to initiation of treatment, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters, and isolate fitness.

Either an elevated echinocandin MIC or the detection of an FKS mutation may predict treatment failures among patients with invasive candidiasis due to C. glabrata, but the roles of genotypic or phenotypic testing in clinical practice are undefined.

Echinocandins remain preferred agents against the vast majority of invasive Candida infections, and susceptibility testing and/or screening for FKS mutations is best reserved for echinocandin-experienced patients with newly diagnosed infections or those who have not responded to echinocandin treatment.

Acknowledgments

None

Financial support and sponsorship: Ryan K. Shields is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grant number K08AI114883, and through research grants from Astellas and Merck.

M. Hong Nguyen is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grant number R21AI107290, and through research grants from Astellas, Merck and Pfizer.

Cornelius J. Clancy is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs through VA Merit Award 1IO1BX001955, and through research grants from Astellas, Merck and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest and published within the past twelve months have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, et al. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 7):19–37. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley JW, et al. Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: a patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1110–1122. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eschenauer G, Depestel DD, Carver PL. Comparison of echinocandin antifungals. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:71–97. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD, et al. Increasing Echinocandin Resistance in Candida glabrata: Clinical Failure Correlates With Presence of FKS Mutations and Elevated Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1724–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fekkar A, Dannaoui E, Meyer I, et al. Emergence of echinocandin-resistant Candida spp. in a hospital setting: a consequence of 10 years of increasing use of antifungal therapy? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1489–1496. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Arendrup MC, Perlin DS. Echinocandin resistance: an emerging clinical problem? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:484–492. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000111. An elegant review of the epidemiology of echinocandin resistance, mechanisms of resistance, and detection of resistance. Characteristics of specific FKS mutations are provided as well as the potential clinical implications of emerging resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Effron G, Park S, Perlin DS. Correlating echinocandin MIC and kinetic inhibition of fks1 mutant glucan synthases for Candida albicans: implications for interpretive breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:112–122. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01162-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Effron G, Lee S, Park S, et al. Effect of Candida glabrata FKS1 and FKS2 mutations on echinocandin sensitivity and kinetics of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase: implication for the existing susceptibility breakpoint. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3690–3699. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00443-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Effron G, Katiyar SK, Park S, et al. A naturally occurring proline-to-alanine amino acid change in Fks1p in Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis accounts for reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2305–2312. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00262-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slater JL, Howard SJ, Sharp A, et al. Disseminated Candidiasis caused by Candida albicans with amino acid substitutions in Fks1 at position Ser645 cannot be successfully treated with micafungin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3075–3083. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01686-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Jensen RH, et al. Differential in vivo activities of anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin against Candida glabrata isolates with and without FKS resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2435–2442. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06369-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepak A, Castanheira M, Diekema D, et al. Optimizing Echinocandin dosing and susceptibility breakpoint determination via in vivo pharmacodynamic evaluation against Candida glabrata with and without fks mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5875–5882. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01102-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Lackner M, Tscherner M, Schaller M, et al. Positions and numbers of FKS mutations in Candida albicans selectively influence in vitro and in vivo susceptibilities to echinocandin treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3626–3635. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00123-14. Serial C. albicans isolates from a patient were collected and the first report of an in vivo selected FKS1 double mutant following prolonged caspofungin therapy is provided. Using a set of isogenic mutant strains and a hematogenous murine model, hetero- and homozygous double mutants were shown to significantly enhance in vivo resistance compared to single mutants. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuse ER, Chetchotisakd P, da Cunha CA, et al. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and invasive candidosis: a phase III randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mora-Duarte J, Betts R, Rotstein C, et al. Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2020–2029. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reboli AC, Rotstein C, Pappas PG, et al. Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2472–2482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castanheira M, Woosley LN, Diekema DJ, et al. Low prevalence of fks1 hot spot 1 mutations in a worldwide collection of Candida strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2655–2659. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01711-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Beyda ND, John J, Kilic A, et al. FKS Mutant Candida glabrata: Risk Factors and Outcomes in Patients With Candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:819–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu407. Comprehensive study of C. glabrata fungemia that identified prior echinocandin exposure as the predominant risk factor for FKS mutant C. glabrata. Underlying gastrointestinal disorders and prior echinocandin exposure were independent predictors of echinocandin treatment failures. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Presence of an FKS mutation rather than minimum inhibitory concentration is an independent risk factor for failure of echinocandin therapy among patients with invasive candidiasis due to Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4862–4869. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00027-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Caspofungin MICs correlate with treatment outcomes among patients with Candida glabrata invasive candidiasis and prior echinocandin exposure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3528–35. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00136-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer CD, Garcia-Effron G, Zaas AK, et al. Breakthrough invasive candidiasis in patients on micafungin. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2373–2380. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02390-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Pham CD, Iqbal N, Bolden CB, et al. Role of FKS Mutations in Candida glabrata: MIC values, echinocandin resistance, and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4690–4696. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03255-14. Comprehensive study of echinocandin resistance and FKS mutations among C. glabrata collected from population-based studies in four cities in the United States. Specific and detailed information is provided for each of the FKS genotypes and the corresponding echinocandin susceptibility. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Jensen RH, Justesen US, Rewes A, et al. Echinocandin failure case due to a previously unreported FKS1 mutation in Candida krusei. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3550–3552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02367-14. First description of a D660Y mutation in FKS1 of C. krusei, which demonstrated different MICs when compared to the corresponding mutation in C. albicans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prigitano A, Esposito MC, Cogliati M, et al. Acquired echinocandin resistance in a Candida krusei blood isolate confirmed by mutations in the fks1 gene. New Microbiol. 2014;37:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Effron G, Chua DJ, Tomada JR, et al. Novel FKS mutations associated with echinocandin resistance in Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2225–2227. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00998-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen RH, Johansen HK, Arendrup MC. Stepwise development of a homozygous S80P substitution in Fks1p, conferring echinocandin resistance in Candida tropicalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:614–617. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01193-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Effron G, Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE, et al. Caspofungin-resistant Candida tropicalis strains causing breakthrough fungemia in patients at high risk for hematologic malignancies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:4181–4183. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00802-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Rate of FKS mutations among consecutive Candida isolates causing bloodstream infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (Accepted) 2015 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01973-15. First study to evaluate consecutive bloodstream Candida isolates for the presence of FKS mutations using systematic screening. Results demonstrated an overall prevalence of 4% in C. glabrata and <1% in C. albicans. Mutations were absent among other species. Among Candida with discrepant echinocandin susceptibility, no evidence of agent-specific FKS mutations was identified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Guinea J, Zaragoza O, Escribano P, et al. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility of yeast isolates causing fungemia collected in a population-based study in Spain in 2010 and 2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1529–1537. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02155-13. Population-based survey across 29 Spanish hospitals showed that susceptibility testing results according to CLSI and EUCAST criteria were comparable. Using species-specific breakpoints and epidemiologic cutoff values, reistance to the echinocandins was <2%. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castanheira M, Woosley LN, Messer SA, et al. Frequency of fks mutations among Candida glabrata isolates from a 10-year global collection of bloodstream infection isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;58:577–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01674-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Abdominal candidiasis is a hidden reservoir of echinocandin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:7601–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Lockhart SR, et al. Frequency of decreased susceptibility and resistance to echinocandins among fluconazole-resistant bloodstream isolates of Candida glabrata. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1199–1203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06112-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34**.Farmakiotis D, Tarrand JJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Drug-resistant Candida glabrata infection in cancer patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1833–1840. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140685. First study to demonstrate an association between increasing caspofungin MICs and mortality among patients with C. glabrata fungemia. High rates of multi-drug resistant C. glabrata, and risk factors for fluconazole and caspofungin resistant isolates are provided. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dudiuk C, Gamarra S, Leonardeli F, et al. Set of classical PCRs for detection of mutations in Candida glabrata FKS genes linked with echinocandin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2609–2614. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01038-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham CD, Bolden CB, Kuykendall RJ, et al. Development of a Luminex-based multiplex assay for detection of mutations conferring resistance to Echinocandins in Candida glabrata. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:790–795. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03378-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vella A, De Carolis E, Vaccaro L, et al. Rapid antifungal susceptibility testing by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2964–2969. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00903-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Fourth informational supplement M27-S4. 4th. Wayne, PA: 2012. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leclercq R, Canton R, Brown DF, et al. EUCAST expert rules in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:141–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Andes D, et al. Clinical breakpoints for the echinocandins and Candida revisited: integration of molecular, clinical, and microbiological data to arrive at species-specific interpretive criteria. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arendrup MC, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lass-Florl C, et al. Breakpoints for antifungal agents: an update from EUCAST focussing on echinocandins against Candida spp. and triazoles against Aspergillus spp. Drug Resist Updat. 2013;16:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Espinel-Ingroff A, Arendrup MC, Pfaller MA, et al. Interlaboratory variability of caspofungin MICs for Candida spp. using CLSI and EUCAST methods: Should the clinical laboratory be testing this agent? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5836–42. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01519-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arendrup MC, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Lass-Florl C, et al. EUCAST technical note on anidulafungin. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:E18–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kartsonis N, Killar J, Mixson L, et al. Caspofungin susceptibility testing of isolates from patients with esophageal candidiasis or invasive candidiasis: relationship of MIC to treatment outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3616–3623. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3616-3623.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45**.Eschenauer GA, Nguyen MH, Shoham S, et al. Real-world experience with echinocandin MICs against Candida species in a multicenter study of hospitals that routinely perform susceptibility testing of bloodstream isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1897–1906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02163-13. Multicenter study demonstrating the interlaboratory agreement of echinocandin MICs derived from Sensititre YeastOne assays. Adoption of CLSI breakpoints, however, resulted in high rates of echinocandin discordant susceptibility for C. glabrata and C. krusei. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Procop GW, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the new Vitek 2 yeast susceptibility test using new CLSI clinical breakpoints for fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2126–2130. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00658-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arendrup MC, Pfaller MA. Caspofungin Etest Susceptibility Testing of Candida Species: Risk of Misclassification of Susceptible Isolates of C. glabrata and C. krusei when Adopting the Revised CLSI Caspofungin Breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3965–3968. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00355-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaller MA, Chaturvedi V, Diekema DJ, et al. Comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric antifungal panel with CLSI microdilution for antifungal susceptibility testing of the echinocandins against Candida spp., using new clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, et al. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the echinocandins and Candida spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:52–56. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01590-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Andes D, et al. Clinical breakpoints for the echinocandins and Candida revisited: Integration of molecular, clinical, and microbiological data to arrive at species-specific interpretive criteria. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:164–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51**.Espinel-Ingroff A, Alvarez-Fernandez M, Canton E, et al. A multi-center study of epidemiological cutoff values and detection of resistance in Candida spp. to anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin using the Sensititre(R) YeastOne colorimetric method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01250-15. in press. The first study to calculate echinocandin epidemiologic cutoff values for the major Candida species using MICs determined by Sensititre YeastOne. Cutoff values for each echinocandin correctlly classified a high percentage of FKS mutant isolates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rex JH, Pfaller MA. Has antifungal susceptibility testing come of age? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:982–989. doi: 10.1086/342384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Anidulafungin and micafungin minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoints are superior to caspofungin for identifying FKS mutant Candida glabrata and echinocandin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:6361–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01451-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54**.Wang E, Farmakiotis D, Yang D, et al. The ever-evolving landscape of candidaemia in patients with acute leukaemia: non-susceptibility to caspofungin and multidrug resistance are associated with increased mortality. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2362–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv087. Among 65 leukemic patients with candidemia, non-susceptibility to caspofungin and multidrug resistance were associated with increased mortality. One-half of caspofungin non-susceptible isolates were C. glabrata. Caspofungin non-susceptibility was associated with fluconazole resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laverdiere M, Lalonde RG, Baril JG, et al. Progressive lost of echinocandin activity following prolonged use for treatment of Candida albicans oesophagitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:705–708. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller CD, Lomaestro BW, Park S, et al. Progressive esophagitis caused by Candida albicans with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:877–880. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baixench MT, Aoun N, Desnos-Ollivier M, et al. Acquired resistance to echinocandins in Candida albicans: case report and review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1076–1083. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kahn JN, Garcia-Effron G, Hsu MJ, et al. Acquired echinocandin resistance in a Candida krusei isolate due to modification of glucan synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1876–1878. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00067-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]