Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths and commonly develops in inflammatory environments. The IGF2 mRNA-binding protein IMP2-2/IGF2BP2-2/p62 was originally identified as an autoantigen in HCC. Aim of this study was to investigate a potential pathophysiological role of p62 in hepatocarcinogenesis. Human HCC tissue showed overexpression of IMP2, which strongly correlated with the fetal markers AFP and DLK1/Pref-1/FA-1 and was particularly elevated in tumors with stem-like features and hypervascularization. Molecular classification of IMP2-overexpressing tumors revealed an aggressive phenotype. Livers of mice overexpressing the IMP2 splice variant p62 highly expressed the stem cell marker DLK1 and secreted DLK1 into the blood. p62 was oncogenic: diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-treated p62 transgenic mice exhibited a higher tumor incidence and multiplicity than wild types. Tumors of transgenics showed a more aggressive and stem-like phenotype and displayed more oncogenic chromosomal aberrations determined with aCGH analysis. DEN-treated p62 transgenic mice exhibited distinct signs of inflammation, such as inflammatory cytokine expression and oxidative stress markers, that is, thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS) levels. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was elevated in HepG2 cells, which either overexpressed p62 or were treated with DLK1. p62 induced this ROS production by a DLK1-dependent induction and activation of the small Rho-GTPase RAC1, activating NADPH oxidase and being overexpressed in human HCC. Our data indicate that p62/IMP2 promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by an amplification of inflammation.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death.1 In most cases, HCC develops based on an inflammatory etiology, namely chronic hepatitis provoked by either viruses, or alcoholic, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation represents a hallmark of inflammation and promotes carcinogenesis.2

The insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) mRNA-binding protein p62/IMP2-2/IGF2BP2-2 represents a shortened splice variant of IMP2, but harboring the identical mRNA-binding domain.3 Although p62 was originally identified as an autoantigen in an HCC patient,4 a functional impact of p62 or IMP2 on hepatocarcinogenesis has not been described in detail as yet. Still, other members of the IMP family, that is, IMP1 and IMP3, were reported to promote HCC5, 6 and other tumors.7, 8

p62 transgenic mice expressing the transgene exclusively in the liver develop steatosis9, 10 and are more prone to develop steatohepatitis.11 The animals express elevated levels of the imprinted genes H19 and Igf2,10 suggesting an effect of p62 on a specific cluster of imprinted genes.12 IGF2 displays a key regulator in mammalian growth through metabolic and growth-promoting effects. Whereas p62 was recently reported to exert its lipogenic actions via IGF2,9 its anti-apoptotic actions are independent of IGF2.13 In addition, IMP2 was suggested to promote HCC cell survival.14

Employing transgenic animals and hepatoma cells we here show that p62 induces an aggressive HCC phenotype, which is linked to inflammatory and oxidant actions of p62. Analyses of publicly available human HCC gene expression data further support p62 as a marker of human HCC with poor prognosis.

Results

p62 expression correlates with DLK1 and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis

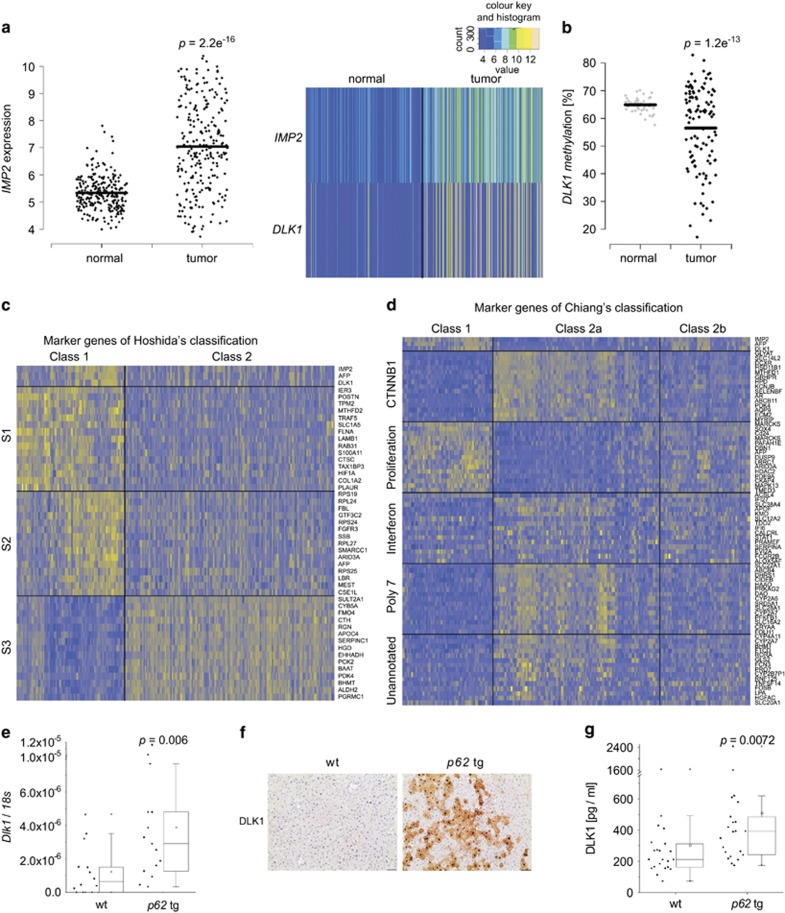

We investigated IMP2 expression in a large patient cohort (GSE14520) of almost 250 predominantly hepatitis B virus (HBV)-positive HCC cases. IMP2 was distinctly overexpressed in tumor compared with normal tissue (Figure 1a). IMP2 strongly correlated with α-fetoprotein (AFP) as a marker of poor prognosis (R2=0.63; P<2.2e−16), which was also differentially expressed compared with normal tissue (P<2.2e−16). p62 was previously shown to induce the expression of the imprinted gene IGF2.10, 13 Another gene of the same imprinted gene cluster,12 DLK1, represents a marker of hepatic stem cells.15 DLK1 was significantly overexpressed and its promoter was hypomethylated in human tumor tissue compared with normal samples (P=1.3e−7; Figure 1a and b) and strongly correlated with IMP2 (R2=0.548; P<2.2e−16) and AFP (R2=0.535; P<2.2e−16).

Figure 1.

p62 and DLK1 expression in p62 transgenic mice and human HCC. (a) Expression analysis of IMP2 (left, right) and DLK1 (right) in human HCC tumor (n=247) and normal liver (n=239) samples (GSE14520). (b) DLK1 promoter methylation in human HCC tumor (n=109) and normal liver (n=50) samples (TCGA). (c and d) Heatmaps of clustering analyses according to Hoshida's (c) and Chiang's (d) HCC subsets.17, 18 The top 15 most differentially expressed genes are indicated for each class. (e) DLK1 mRNA levels in livers of untreated animals 5 weeks of age: wt (n=14), p62 transgenic (p62 tg; n=15). Error bars show the interquartile range. (f) Representative immunohistochemical staining for DLK1 in untreated 5-week-old mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. (g) Serum DLK1 protein levels in 5-week-old wt (n=22) and p62 tg (n=22) mice. Error bars show the interquartile range

In order to connect IMP2, AFP, and DLK1 overexpression to already known molecular subsets of HCC,16 we performed hierarchical clustering of data set GSE14520 according to the marker genes identified by Hoshida et al.17 for three HCC subtypes in mouse and by Chiang et al.18 for five HCC subtypes in human (Supplementary Figure S1). Subsequent signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) analysis revealed that IMP2, DLK1, and AFP show similar expression patterns as marker genes of class 1, in which 84% of S1 and 65% of S2 marker genes were found (Supplementary Table S3). Class 2 can be described by subclass S3 presented by Hoshida et al. (Figure 1c, Supplementary Figure S3). Clustering by Chiang's marker genes resulted in three major classes (Supplementary Figure S2). Here, class 1, which included IMP2, DLK1, and AFP, was well related to Chiang's proliferation class. Class 2a can be described by elevated CTNNB1, Interferon, and Poly7 subclasses. Class 2b, however, was not related to any of Chiang's subclasses (Figure 1d, Supplementary Table S4,Supplementary Figure S3).

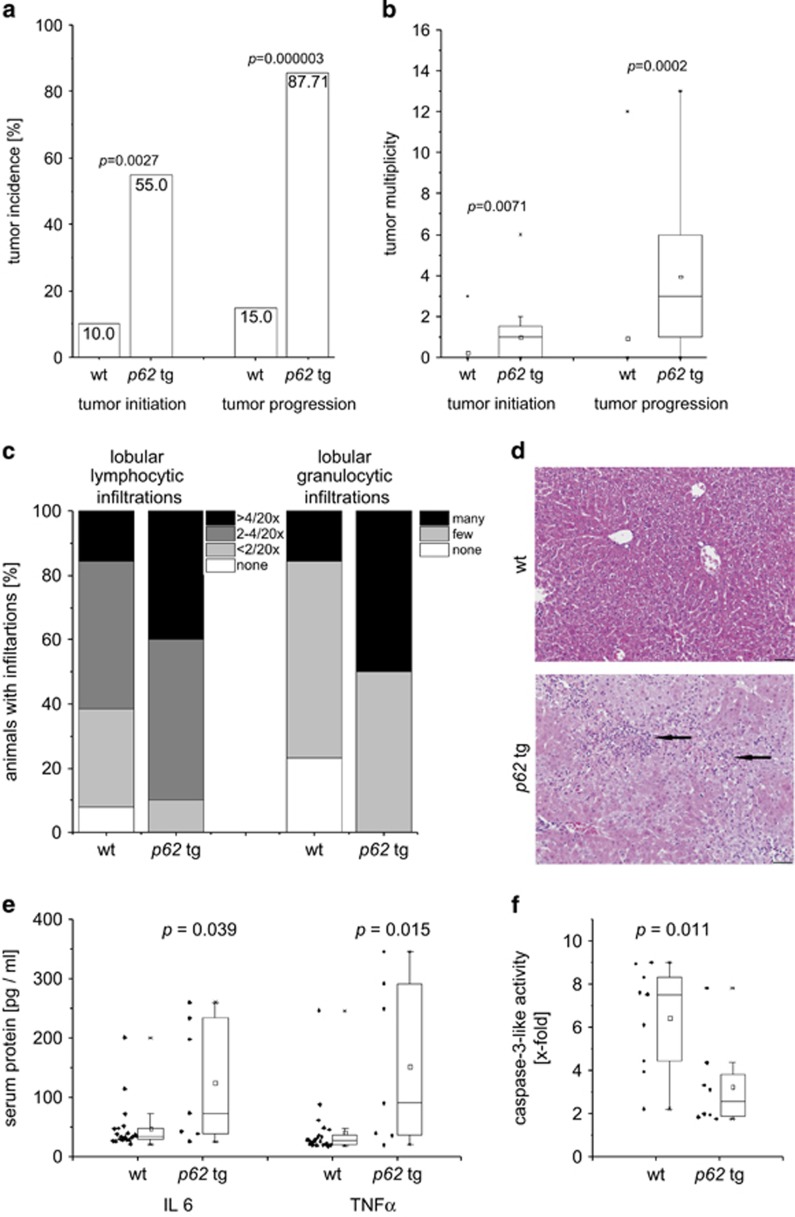

A causal link of DLK1 expression to IMP2 was given by the fact that DLK1 mRNA and protein were increased in livers overexpressing the IMP2 splice variant p62 compared with wild types (wt; Figure 1e and f). Interestingly, also secreted DLK1 was elevated in the serum of p62 transgenic animals (Figure 1g). As p62 induced the stem cell marker DLK1, we aimed to investigate the role of p62 in hepatocarcinogenesis employing the diethylnitrosamine (DEN) model. Both tumor incidence and tumor multiplicity were increased in DEN-treated p62 transgenic animals during the early and late stages of tumor development (Figure 2a and b).

Figure 2.

Susceptibility of p62 transgenic mice to hepatocarcinogenesis. (a and b) Tumor incidence (a) and tumor multiplicity (b) in early stage (6 months: wt: n=20; p62 tg: n=20; tumor initiation) and late stage (8 months: wt: n=20; p62 tg: n=20; tumor progression) of DEN-treated mice. Error bars show the interquartile range. (c and d) Histological scoring of HE stainings and representative picture for lobular lymphocytic and granulocytic infiltrations 48 h after DEN application. Arrows denote mixed lymphocytic and granulocytic infiltrations. Scale bar: 50 μm. (e) Serum protein levels of IL6 (left) and TNFα (right) of 5-week-old wt (n=22) and p62 tg (n=7) mice 48 h after DEN application. (f) Caspase-3-like activity in DEN-treated 5-week-old wt (n=9) and p62 tg (n=8) mice 48 h after DEN injection normalized to untreated wt. Error bars show the interquartile range

After 48 h of DEN treatment, which models early liver cell damage,19 p62 transgenic mice revealed a more pronounced inflammatory response as shown by increased lobular lymphocytic as well as granulocytic infiltrations (Figure 2c and d) and by elevated serum levels of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα; Figure 2e). Neither AST nor ALT levels were different in p62 transgenic animals compared with DEN-treated wt mice (Supplementary Table S5). Still, apoptosis was reduced in DEN-treated p62 transgenic animals (Figure 2f).

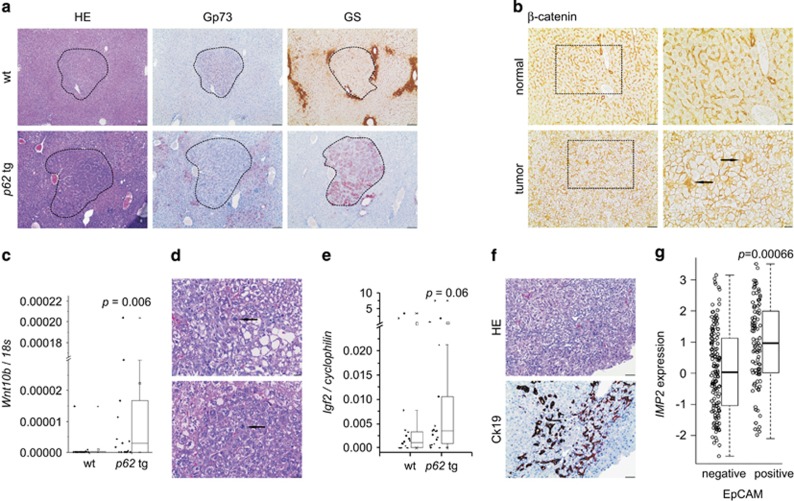

Tumors of p62 transgenic mice show a more aggressive phenotype

In order to characterize the DEN-induced tumors, paraffin sections were stained for the tumor markers Golgi membrane protein 73 (Gp73) and glutamine synthetase (GS). All wt tumors were Gp73-positive, whereas in transgenics only 70.31% were Gp73-positive. Interestingly, whereas none of the wt tumors stained positive for GS, 29.69% of p62 tumors were GS-positive and half of them were positive for both markers (Figure 3a). GS positivity is regarded as a marker of β-catenin activation,20 which can be regulated by activation of the canonical wingless-int (WNT) pathway. Concordantly, β-catenin staining confirmed its activation by nuclear and cytoplasmatic localization in tumor tissue, whereas normal tissue showed a membranous pattern (Figure 3b). Wnt10b, a canonical WNT pathway member, which is highly expressed in fetal, but shut down in adult liver, was increased in p62 transgenic animals (Figure 3c). Tumors of transgenic animals were more mitotically active (P=0.0477) by irregular mitosis (Figure 3d) and were rather pleomorphic (0% in wt versus 15.6% in tg, P=0.014). mRNA levels of the pro-proliferative growth factor Igf2 tended to be increased in p62 transgenic animals (Figure 3e). CK19-positive oval cell compartments were solely observed in tumors of transgenics (Figure 3f). Concordantly, human HCCs positive for the oval cell marker EpCAM exhibited higher expression levels of IMP2 compared with EpCAM-negative HCCs in an HBV-positive HCC cohort (238 samples; GSE5975; Figure 3g).

Figure 3.

p62 transgenic mice develop a more aggressive tumor phenotype. (a) Representative HE and immunostainings against Golgi membrane protein 73 (Gp73) and GS in wt and p62 tg mice in late-stage tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. (b) Representative β-catenin immunostaining in adjacent normal and tumor tissue of livers bearing GS-positive tumors. Scale bars: 50 μm (left), inset (right): 20 μm. (c) WNT10B mRNA levels in wt (n=18) and p62 tg (n=18) in the late tumor stage. Error bars show the interquartile range. (d) Arrows show irregular mitosis in representative HE stainings in tumors of p62 tg mice. Scale bars: 20 μm. (e) Igf2 mRNA levels in wt (n=18) and p62 tg (n=18) in the late tumor stage. Error bars show the interquartile range. (f) Representative HE and corresponding oval cell marker CK19 immunostaining in p62 tg tumors. Scale bars: 50 μm. (g) IMP2 expression in human HCCs grouped into EpCAM-positive and -negative tumors (238 samples; GSE5975)

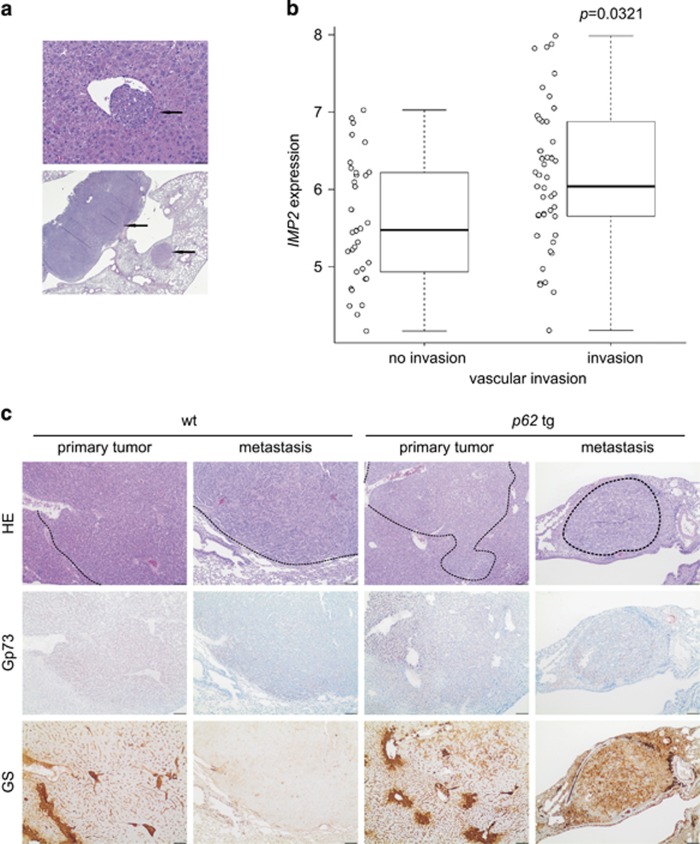

Vascular invasion as well as lung metastases developed in both wt as well as in transgenic animals without statistically significant difference (Figure 4a). Analysis of a GEO data set of 226 predominantly viral hepatitis-related HCC cases (GSE20238) categorized by the presence or absence of vascular invasion revealed increased IMP2 expression in patients with vascular invasion (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Metastasis in DEN-induced tumors. (a) Representative HE sections showing vascular invasion (upper panel, scale bar: 50 μm) and lung metastases (lower panel, scale bar: 500 μm). Arrows designate metastatic foci. (b) IMP2 expression in human HCCs grouped into tumors positive or negative regarding vascular invasion (91 samples; GSE20238). (c) Representative HE and Gp73 and GS immunohistochemistry (IHC) of primary liver tumor and lung metastasis in wt (n=21) and p62 tg (n=18) mice in the metastatic phase. Scale bars: liver: 200 μm; lung: 100 μm

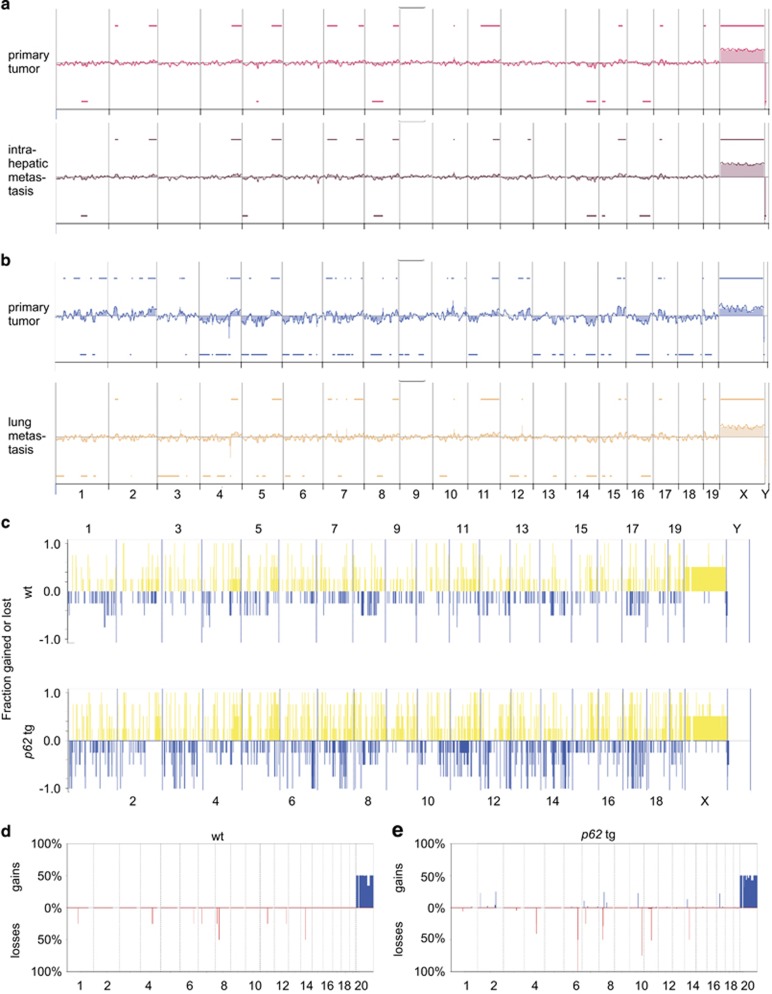

Murine lung metastases showed the same staining pattern for the HCC markers GS and Gp73 as the primary liver tumors of wt and p62 transgenic mice (Figure 4c). In the metastatic phase, also some wt tumors showed positive GS staining (data not shown). aCGH analysis confirmed clonality of primary tumors and both intrahepatic (P<10−5) as well as lung metastases (P<10−5; Figure 5a and b, Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 5.

Clonality of primary tumors and metastases and genomic instability in tumors of p62 transgenic mice. (a and b) Representative aCGH plots of primary HCC and corresponding intrahepatic metastasis (a) and of primary HCC and corresponding lung metastasis (b) of p62 transgenic mice. (c) Frequency plot of fractions gained or lost along the genome of primary tumors in wt (n=4; upper panel) and p62 tg (n=4; lower panel) mice in the late tumor stage. (d and e) Most significant alterations in primary tumors of wt (d) and p62 tg (e) animals during the late tumor stage. Shown are percentages of gains and losses for individual altered segments obtained with the CGHcall package

p62 transgenic mice are more susceptible to chromosomal aberrations

aCGH analysis (Figure 5c) revealed increased alterations in tumors of transgenic (lower panel) compared with wt animals (upper panel). Significant gains were only observed in transgenic tumors, and significant losses were stronger in transgenic compared with wt tumors (Figure 5d and e). Some loci only showed aberrations in p62 transgenic mice: their corresponding loci on the human genome are given in Supplementary Table S7. Gene Ontology analysis revealed that the affected loci harbor genes, which are involved in growth, proliferation, negative apoptosis signaling, and angiogenesis (Supplementary Table S8). Interestingly, the distal mouse 15B3.1-C region, amplified only in p62 transgenics and corresponding to the human distal chromosome 8q23.1-23.3, is the second most frequently amplified region in human HCC: aCGH results from 848 HCC samples show an amplification in ~45% of cases (www.progenetix.net). This region comprises genes commonly mutated in cancer (Supplementary Table S7).

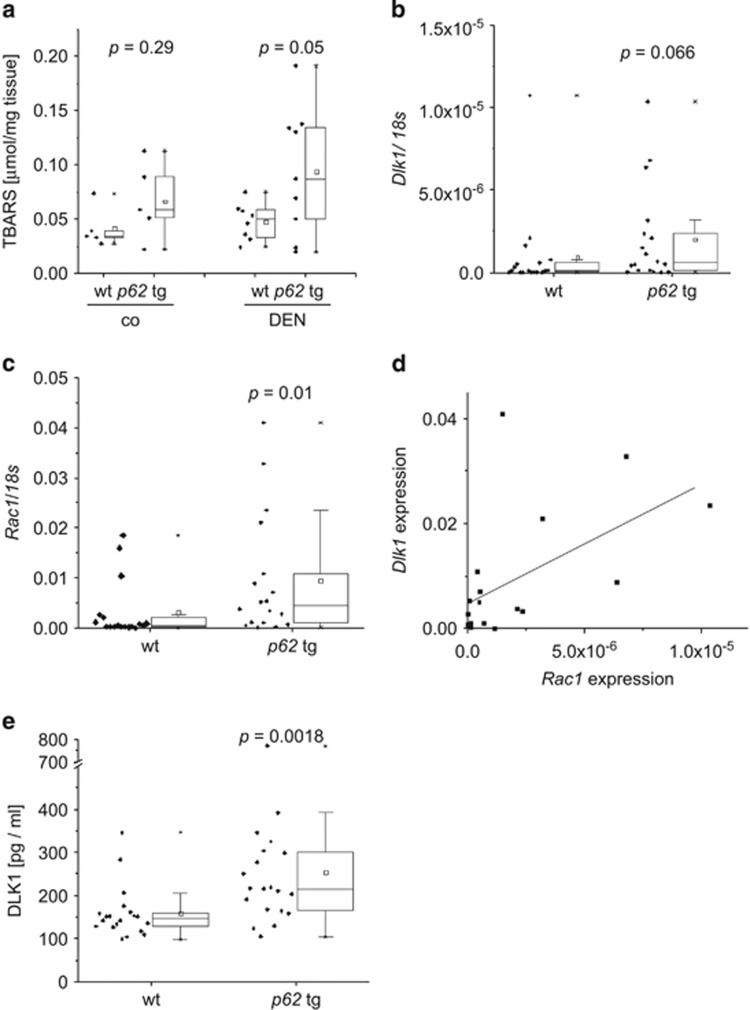

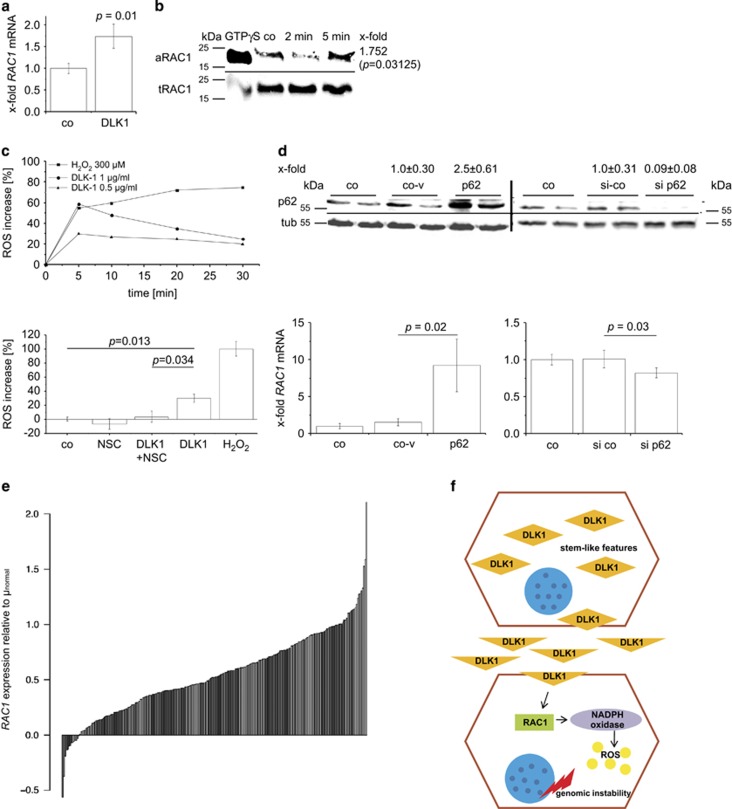

Tumor-promoting DLK1 drives RAC1-induced ROS formation

We sought to identify the reason for p62-induced increased genomic instability and found significantly elevated levels of TBARS as indicators of oxidant stress in p62 transgenic animals after short-term treatment with DEN (Figure 6a). ROS are important inducers of DNA damage and chromosomal instability.2 NADPH oxidase represents an ROS-generating enzyme complex that contributes to DEN-induced carcinogenesis.21 NADPH oxidase is activated by the small GTPase RAC1,22 and DLK1 was previously shown to induce RAC1.23 We observed increased levels of both Dlk1 and Rac1 mRNA in p62 transgenic livers and a strong correlation between each other (Pearson R2=0.56, P=0.015; Figure 6b–d). The secreted form of DLK1 was elevated in p62 transgenic mice (Figure 6e). In order to test the causal effect of p62 and DLK1 on RAC1, in vitro experiments were performed. DLK1 treatment increased RAC1 mRNA levels as well as activated RAC1 protein as detected by pull-down assay in HepG2 cells (Figure 7a and b). Furthermore, DLK1 treatment increased ROS levels, which was completely abrogated by pre-incubation with the RAC1 inhibitor NSC23766 (Figure 7c). In addition, p62 overexpression increased RAC1 expression (Figure 7d). Vice versa, knockdown of p62 led to decreased RAC1 mRNA levels (Figure 7d). ROS levels were elevated after p62 overexpression by 9.46±1.24% (P=0.045) 48 h after transfection, which was abrogated by the RAC1 inhibitor (P=0.0046). Finally, the human HCC cohort, which showed differential expression of IMP2 and DLK1 (Figure 1a), significantly overexpressed RAC1 (Figure 7e; P<2.2e−16). SNR analysis revealed RAC1 overexpression in class 1 (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4), which was characterized by IGF2BP2, AFP, and DLK1 overexpression (Figure 1b).

Figure 6.

Increased levels of ROS and ROS-inducer RAC1 in p62 transgenic mice. (a) Hepatic TBARS levels in wt (n=5) and p62 tg (n=5) livers of untreated (co) and 48-h DEN-treated (DEN) animals (wt: n=8; tg: n=9). Error bars show the interquartile range. (b–d) Dlk1 (b) and Rac1 (c) mRNA expression as well as correlation of both d was investigated after 8 months (wt: n=18; tg:n=18). Error bars show the interquartile range. (e) Secreted DLK1 protein serum levels were measured by ELISA. Error bars show the interquartile range

Figure 7.

p62 promotes DLK1-RAC1-driven ROS generation. (a and b) Levels of RAC1 mRNA presented as mean±S.E.M. (a) and activated RAC1 protein levels determined by pull-down assay (b) in HepG2 cells after treatment with 1 μg/ml DLK1 protein (n=3 in duplicate). (b) Representative pull-down assay with activated RAC1 (aRAC1) and total RAC1 (tRAC1) is shown. X-fold signal intensities of 5-min treatment with DLK1 were normalized to untreated control (co). (c) ROS levels: representative experiment (quintuplicates) of HepG2 cells treated with 0.5 or 1 μg/ml DLK1 or H2O2 as positive control for 0–30 min (upper part). Data are normalized to untreated HepG2 cells. ROS levels in HepG2 cells treated with either DLK1 or RAC1 inhibitor NSC23766 alone or in combination (lower part). Untreated HepG2 cells served as control. H2O2-induced ROS formation was set to 100% (n=2, quintuplicate). Data are presented as mean±S.E.M. (d) RAC1 expression in HepG2 cells overexpressing (left) p62 sense plasmid (p62) compared with antisense-plasmid (co-v), untreated control (co), and siRNA knockdown (right) of p62 (si p62) compared with random siRNA (si co; n=3 triplicate/quadruplicate). Data show mean±S.E.M. Western blot knockdown/overexpression control was densitometrically quantified (n=4 triplicate/quadruplicate; upper part). (e) RAC1 expression in human HCC (GSE14520) normalized to the mean of normal samples. (f) Overview of p62-promoted DLK1-RAC1-induced genomic instability. DLK1-overexpressing cells with stem-cell-like features secrete DLK1 protein, which activates RAC1 in a paracrine manner, in turn leading to ROS generation via NADPH oxidase. Elevated ROS levels finally result in genomic instability

Discussion

The IMP p62 was originally identified as a tumor-associated autoantigen with autoantibodies against p62 detected in HCC patients4 and in several other types of cancer.24, 25 Interestingly, despite several investigations of p62 autoantibodies as a potential tumor marker and a recently suggested resistance of IMP2 knockout mice toward malignancy,26 functional implications of the p62 protein in carcinogenesis are widely unknown. Our analysis of a large homogenous human HCC cohort with ~250 viral HCC samples showed strongly increased expression of IMP2 in the majority of HCC patients. These data are supported by other reports suggesting elevated levels of p62 in HCC tissue in rather small patient cohorts.13, 27 According to the classification performed in this study, overexpression of AFP and IGF2, both correlating with IMP2 expression in HCC (present findings and Kessler et al.13), marks Hoshida's S2 class of aggressive HCC.28 Positivity of the stem cell surface antigen EpCAM and vascular invasion, which we observed to be linked to IMP2 overexpression, was used as a classification system by others.29, 30 In fact, EpCAM expression is associated with early recurrence and short survival time.31

Regarding the classification from Boyault et al.,32 IMP2-overexpressing samples probably belong to the G1 subset, which is characterized by an increased expression of AFP and the imprinted gene products IGF2 and H19. p62 transgenic mice were shown to overexpress both imprinted genes.10 Finally, IMP2-overexpressing samples match the molecular pattern of Cairo's aggressive hepatoblastoma, in which AFP, Krt19, and EpCAM are elevated. In the same study the authors provide data from Myc-induced murine tumors highly expressing DLK1, IGF2, and AFP.33 A summary of assignments of class 1 and class 2 HCCs to known molecular HCC subsets is given in Supplementary Figure S4.

Interestingly, we observed a correlation of IMP2 expression with the oval/stem cell marker DLK1.15 DLK1 was previously shown to correspond with poor survival in HCC.34 Oval cells share phenotypic markers with embryonic hepatoblasts, in which DLK1 is also highly expressed.35 The cytoplasmatic appearance of DLK1 in p62 transgenic mice reveals a fetal phenotype as previously reported for HCC and hepatoblastoma tissue.36 Secreted DLK1, suggested as a serum marker for hepatoblastoma,37 was elevated in sera of p62 transgenic mice.

Secreted DLK1 was suggested to have paracrine functions, that is, inducing the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL6 in monocytes and adipocytes.38 Recently, p62 expression was shown to promote liver disease by amplifying inflammatory processes.9, 11, 39, 40, 41 HCC mostly develops within an inflammatory environment, such as viral hepatitis, ASH and NASH, and inflammatory mediators promote hepatocarcinogenesis.19 We here present a transgenic mouse model, which develops HCC out of an inflammatory state involving elevated IL6 and TNFα productions. We observed an early onset and an accelerated progression of HCC in p62 transgenic mice.

There are two different models using the carcinogen DEN to induce liver tumors. DEN is either given as a single dose by itself or in combination with the tumor-promoting agent phenobarbital to induce tumors with β-catenin mutations, which are linked to GS positivity.20 Interestingly, employing p62 transgenic mice, we observed GS-positive tumors in the DEN model without using phenobarbital.

The expression of DLK1 is closely linked to WNT10B, a member of the canonical WNT pathway, leading to β-catenin accumulation in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, which can be altered by DLK1.42 Both elevated Wnt10b and cytoplasmatic/nuclear localization can be found in p62 transgenic tumors.

In tumors positive for the stem cell marker EpCAM, co-expression of DLK1 and AFP was defined by poor prognosis.43 Tumors of p62 transgenic livers were more susceptible to chromosomal aberrations than tumors of wt animals and showed more pronounced alterations. Increasing levels of chromosomal instability correlate with progression of HCC, suggesting that marked genomic instability characterizes more advanced stages of the disease. The homolog of human 8q23, amplified specifically in p62 transgenic animals, is frequently gained in human HCC tissues.44 Interestingly, amplification of the homolog of human chromosome 3q, which was gained in p62 transgenic tumors, is correlated with advanced-stage disease in cervical carcinomas.45 The losses specifically observed in p62 transgenics on the homologs of human chromosomes 9q33.3-34.3, 11q23.1-24.1, 16q42.13-42.2, and 21q22.11-3 were reported to be deleted in different types of cancer including HCC.46, 47

Genomic instability can be induced through ROS production.2 A major ROS-generating enzyme complex, the NADPH oxidase, is activated by the small GTPase RAC1.22 We found RAC1 to be highly overexpressed in a large proportion of HCC tissues. RAC1 itself has been described to have a role in HCC48 and might act at least partly via ROS production.49 In addition, Ras-induced ROS production and DNA damage has been linked to RAC1 activation.50 Our data functionally link the aggressive and dedifferentiated phenotype of the tumors in p62 transgenic livers to DLK1-facilitated induction of RAC1. The stem cell marker and paracrine factor DLK1 was previously reported to induce RAC1 activation in 3T3-L1 cells.23 We here report that DLK1-induced RAC1 activation leads to elevated ROS levels (Figure 7f). We suggest that the DLK1/RAC1-induced increase in ROS is the cause of chromosomal instability,2 which in turn leads to more undifferentiated tumors.51 Interestingly, RAC1 activation was shown to drive proliferation of intestinal stem cells52 and targeting RAC1 suppresses cancer cell viability,53 cancer stem cell activities,54 and metastasis.55 Wang et al.56 reported that RAC GTPase-activating protein 1 is associated with early recurrence in HCC.

Taken together, our in vivo, in vitro, and in silico analyses show that IMP2/p62 has an important role in HCC initiation and progression and characterizes human HCC prognosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the local animal welfare committee. Mice were kept under controlled conditions regarding temperature, humidity, 12 h day/night rhythm, and food access. p62 transgenic mice expressing the transgene exclusively in the liver were established as previously described.10 For the short-term experiment, p62 transgenic (p62 tg) mice and matched wt littermates were treated with 100 mg/kg body weight (BW) DEN i.p. at the age of 2.5 or 5 weeks and were killed 48 h later.19, 39 For tumor induction, p62 transgenic mice and wt littermates were injected with 5 mg/kg BW at the age of 2 weeks. In long-term experiments, mice were killed at an age of 6 and 8 months modeling an early (tumor initiation) and late (tumor progression) tumor stage, respectively.57 Metastases were investigated in animals older than 10 months (metastatic phase; wt: n=21, tg: n=18).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Experiments and quantification were performed as described in detail previously.9 Sequences and conditions are given in Supplementary Table S1.

ELISA

Serum levels of IL6 (#m6000b, R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany), TNFα (#mta00b, R&D Systems), and DLK1 (#CSB-EL006945MO, Cusabio Biotech, Wuhan, China) were performed with ELISA according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Demasking, antibody dilutions, and detection reagents are given in Supplementary Table S2. Primary antibodies used were specific to GS, Golgi membrane protein 73 (Gp73), β-catenin, and p62.13 Samples were examined by two independent investigators blinded to experimental conditions.

Western blot

Western blot analysis of p62 protein levels was performed according to Kessler et al.13

Quantification of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

Products of lipid peroxidation were measured as previously described.40

Cell culture

Knockdown and overexpression experiments for p62 in HepG2 were performed as previously described.13 p62 sense and antisense constructs are available at Addgene (#42174 and #42175, Cambridge, MA, USA). Recombinant DLK1 was used for treatment (#1144-PR-025, R&D Systems).

Caspase-3-like activity assay

Caspase-3-like activity assay was perfomed as previously described.13 The extraction buffer was slightly modified: 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, pepstatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin (1 μg/ml each).

ROS assay

ROS assay was performed as previously described.22 HepG2 cells were loaded with either 20 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate alone or with the RAC1 inhibitor NSC23766 (#2161/10, R&D Systems) in PBS 60 min before DLK1 treatment for 48 h after transfection and 50 min before measurement, respectively. Combined DLK1 and NSC23766 treatment was performed for 5 min. DLK1/H2O2 (positive control) treatment over time (5–30 min) was performed in quintuplicates.

RAC1 pull-down assay

Activated RAC1 levels were measured by pull-down assay as previously described.22, 58

The affinity precipitation assay detects the binding of active RAC1 to a fusion protein consisting of the RAC1 target p21-activated kinase 1 and glutathione S-transferase (GST). GST-PBD was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified, and bound to glutathione Sepharose beads (#17-0756-01, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Freiburg, Germany). For RAC1 pull-down assays, HepG2 cells were treated with 1 μg/ml recombinant DLK1 (#1144-PR-025, R&D Systems), cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and were lysed with PBD-buffer (Tris pH 8.0 25 mM, DTT 1 mM, MgCl2 20 mM, NaCl 100 mM, EDTA 0.5 mM, Triton X-100 1%, Aproptinin 0.1%, Leupeptin 0.1%, and PMSF 0.1%). As a positive control, one sample was lysed with GTPγS-PBD-buffer (Tris pH 8.0 25 mM, DTT 1 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, NaCl 100 mM, EDTA 1 mM, Triton X-100 1%, Aprotinin 0.1%, Leupeptin 0.1%, and PMSF 0.1%). After scraping cells off, cells were incubated for complete lysis for 15 min at 4 °C under vigorous shaking. The positive control was incubated for 10 min with GTPγS (10 mM), leading to an exchange of RAC-GDP to RAC-GTP, which was stopped by adding MgCl2 (1 M). After centrifugation, the supernatants of cell lysates and positive control were incubated with 30 μl GST-PBD beads for 2 h at 4 °C under vigorous shaking. After centrifugation and one wash step with PBD-/GTPγS-PBD-buffer, the pellet was frozen at −80 °C.

Pull-down supernatants and pellets with loading buffer were boiled for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were separated using SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and are transferred onto Immobilon-FLPVDF membranes (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA). The membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with IRDye-conjugated secondary antibody. After washing, blots were scanned with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology, Bad Homburg, Germany) and signal intensities were determined using the Odyssey software.

aCGH analysis

Paraffin-embedded liver tumors were microdissected and hybridized against 3-month-old wt liver tissues. Labeling was performed following the BioPrime aCGH Genomic Labeling Module protocol (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher, Dreieich, Germany). The samples were hybridized on an 8x60-k CGH Array under the conditions of the Agilent protocol (Version 7.2). The arrays were analyzed with an Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner G2505C (Agilent, Böblingen, Germany) and the extraction software Agilent Feature Extraction 11.0.1.1. The data were analyzed using the statistical software R Bioconductor packages aCGH59 and CGHcall.60 In order to compute the similarity of aberrations in the primary tumor and the corresponding metastasis, permutation tests were used to calculate the pair-wise statistical significance similar to the method described in Haybaeck et al.61 Aberrations were labeled using the bioconductor package aCGH with standard log ratio threshold of |0.25|.59 The number of matching positions was calculated in the two samples. The aberration positions of the sample containing fewer aberrations were randomly reordered, matched to a random set of aberration positions of the other sample, and the new number of matching positions (ri) was calculated. This step was repeated n=100 000 times and the number of times r that showed a higher number of matching aberrations of the randomly reshuffled samples compared with the original samples was counted as r=sum (ri> o). The P-value for the statistical significance of matching positions of gains or losses was estimated as P=r/n. Overlap of aberrations and P-values of similarity are provided in Supplementary Table S6. Locations of aberrations specifically observed in the p62 transgenic animals were detected using the Golden Helix software: analysis was conducted using SNP an Variation Suite v8. These loci were compared with the aberrant loci of human HCC samples on www.progenetix.org. GOSim was used to identify enriched Gene Ontology terms.62 The mutation data were obtained from the Sanger Institute COSMIC website, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic. In addition, the CGHcall package60 was used to search for significant alterations. CGHcall employs DNAcopy methods63 to normalize and smoothen the data and defines equal copy number segments for further analysis.

Human GEO data sets

For differential gene expression between tumor (n=247) and non-tumor (n=239) samples, the log2 of an RMA-normalized data set (GSE14520)64 of an AffymetrixGeneChip HG-U133A 2.0 was analyzed. Similarly, differential gene expression was analyzed in data set GSE5975 between positive (n=95) and negative (n=143) EpCAM samples and in data set GSE20238 between vascular invasive (n=45) and non-invasive (n=34) HCC samples. Differential expression analysis was based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Pearson correlation was applied to detect correlations between genes of interest.

Identification of common molecular HCC subclasses

Complete hierarchical clustering of data set GSE1452064 was performed using the marker genes presented by Hoshida et al.17 and Chiang et al.18 The cluster dendograms are provided below Supplementary Figure S1. To test the affiliation of genes with HCC subtypes, the SNR was calculated for each marker gene as described in Hoshida et al.17 and Golub et al.65

Methylation analysis using a TCGA data set

TCGA analysis of DNA methylation in HCC was performed using an Illumina Infinium Human Methylation 450 platform. The data set contains 50 normal and 109 tumor samples. We considered methylation only in the promoter regions (defined within 2000 bp from the transcription start site provided in the EPD promoter DB.66 Averages were considered for regions covered by multiple probes.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and statistics of experimental data were performed using the Origin software (OriginPro 8.1G; OriginLabs, Northampton, MA, USA). All data are displayed either as columns with mean values±S.D. or as individual values and boxplots±interquartile range with mean and median. Statistical differences were estimated by independent two-sample t-test or Wilcoxon-rank-sum test depending on normal distribution, which was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk method, or Fisher-exact test for categorical data. Normally distributed data comparing multiple groups were analyzed using ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. All tests are two-sided, and differences were considered statistically significant when P-values were less than 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Gogg-Kammerer for excellent technical assistance and Eva Dilly for help in animal care. The project was funded, in part, by an EASL Dame Sheila Sherlock Fellowship (to SMK), a Bank Austria Visiting Scientists Programme Fellowship (to SMK), the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2012_A250 to AKK and SMK), the Deutsche Krebshilfe (107751 to AKK), the research committee of Saarland University (61-cl/Anschub2012/bew-ansch_bew_kessler to SMK), and the Graduiertenförderung of Saarland University (to SL).

Author contributions

SMK, SL, JH and AKK designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. AKK initiated and directed the study. The others designed experiments and participated in data acquisition.

Glossary

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IGF2

insulin-like growth factor 2

- IMP2-2/IGF2BP2-2

insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein

- BW

body weight

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- TBARS

thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances

- GS

glutamine synthetase

- Gp73

Golgi membrane protein 73

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factorα

- IL6

interleukin 6

- DLK1

delta-like 1 homolog

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

- WNT

wingless-int

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- EpCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by T Kaufmann

Supplementary Material

References

- 1Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Block K, Gorin Y. Aiding and abetting roles of NOX oxidases in cellular transformation. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12: 627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Christiansen J, Kolte AM, Hansen TVO, Nielsen FC. IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 2: biological function and putative role in type 2 diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol 2009; 43: 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Zhang J-Y, Chan EKL, Peng X-X, Tan EM. A novel cytoplasmic protein with RNA-binding motifs is an autoantigen in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Med 1999; 189: 1101–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Pazaitis N, Bley N, Fiskin E, Uckelmann H et al. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) is an important protumorigenic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2014; 59: 1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Jeng YM, Chang CC, Hu FC, Chou HY, Kao HL, Wang TH et al. RNA-binding protein insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein 3 expression promotes tumor invasion and predicts early recurrence and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008; 48: 1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Rivera Vargas T, Boudoukha S, Simon A, Souidi M, Cuvellier S, Pinna G et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of cyclins D1, D3 and G1 and proliferation of human cancer cells depend on IMP-3 nuclear localization. Oncogene 2014; 33: 2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Elcheva I, Tarapore RS, Bhatia N, Spiegelman VS. Overexpression of mRNA-binding protein CRD-BP in malignant melanomas. Oncogene 2008; 27: 5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Laggai S, Kessler SM, Boettcher S, Lebrun V, Gemperlein K, Lederer E et al. The IGF2 mRNA binding protein p62/IGF2BP2-2 induces fatty acid elongation as a critical feature of steatosis. J Lipid Res 2014; 55: 1087–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Tybl E, Shi F-D, Kessler SM, Tierling S, Walter J, Bohle RM et al. Overexpression of the IGF2-mRNA binding protein p62 in transgenic mice induces a steatotic phenotype. J Hepatol 2011; 54: 994–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Simon Y, Kessler SM, Bohle RM, Haybaeck J, Kiemer AK. The insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) mRNA-binding protein p62/IGF2BP2-2 as a promoter of NAFLD and HCC? Gut 2014; 63: 861–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Gabory A, Jammes H, Dandolo L. The H19 locus: role of an imprinted non-coding RNA in growth and development. Bioessays 2010; 32: 473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13Kessler SM, Pokorny J, Zimmer V, Laggai S, Lammert F, Bohle RM et al. IGF2 mRNA binding protein p62/IMP2-2 in hepatocellular carcinoma: antiapoptotic action is independent of IGF2/PI3K signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2013; 304: G328–G336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Fawzy IO, Hamza MT, Hosny KA, Esmat G, El Tayebi HM, Abdelaziz AI. miR-1275: A single microRNA that targets the three IGF2-mRNA-binding proteins hindering tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. FEBS Lett 2015; 589: 2257–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15Schievenbusch S, Sauer E, Curth HM, Schulte S, Demir M, Toex U et al. Neighbor of punc e 11: expression pattern of the new hepatic stem/progenitor cell marker during murine liver development. Stem Cells Dev 2012; 21: 2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS. Comparative and integrative functional genomics of HCC. Oncogene 2006; 25: 3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Hoshida Y, Nijman SMB, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, Peix J, Newell P, Minguez B et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 6779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 2010; 140: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Loeppen S, Schneider D, Gaunitz F, Gebhardt R, Kurek R, Buchmann A et al. Overexpression of glutamine synthetase is associated with beta-catenin-mutations in mouse liver tumors during promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis by phenobarbital. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 5685–5688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Teufelhofer O, Parzefall W, Kainzbauer E, Ferk F, Freiler C, Knasmüller S et al. Superoxide generation from Kupffer cells contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis: studies on NADPH oxidase knockout mice. Carcinogenesis 2005; 26: 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Fürst R, Brueckl C, Kuebler WM, Zahler S, Krötz F, Görlach A et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide induces mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in human endothelial cells via Rac1 and NAD(P)H oxidase/Nox2-activation. Circ Res 2005; 96: 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Wang Y, Zhao L, Smas C, Sul HS. Pref-1 interacts with fibronectin to inhibit adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30: 3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Liu W, Li Z, Xu W, Wang Q, Yang S. Humoral autoimmune response to IGF2 mRNA-Binding protein (IMP2/p62) and its tissue-specific expression in colon cancer. Scand J Immunol 2013; 77: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Rom WN, Goldberg JD, Addrizzo-Harris D, Watson HN, Khilkin M, Greenberg AK et al. Identification of an autoantibody panel to separate lung cancer from smokers and nonsmokers. BMC Cancer 2010; 10: 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Dai N, Zhao L, Wrighting D, Krämer D, Majithia A, Wang Y et al. IGF2BP2/IMP2-deficient mice resist obesity through enhanced translation of Ucp1 mRNA and other mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins. Cell Metab 2015; 21: 609–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Lu M, Nakamura RM, Dent ED, Zhang J-Y, Nielsen FC, Christiansen J et al. Aberrant expression of fetal RNA-binding protein p62 in liver cancer and liver cirrhosis. Am J Pathol 2001; 159: 945–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Hoshida Y, Toffanin S, Lachenmayer A, Villanueva A, Minguez B, Llovet JM. Molecular classification and novel targets in hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advancements. Semin Liver Dis 2010; 30: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Mínguez B, Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Toffanin S, Cabellos L, Thung S et al. Gene-expression signature of vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2011; 55: 1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, Forgues M, Yang W, Wang HY et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Guo Z, Li LQ, Jiang JH, Ou C, Zeng LX, Xiang BD. Cancer stem cell markers correlate with early recurrence and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Boyault S, Rickman DS, De Reyniès A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology 2007; 45: 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Cairo S, Armengol C, Reynies De A, Wei Y, Thomas E, Renard C-Al et al. Hepatic stem-like phenotype and interplay of Wnt/beta-catenin and Myc signaling in aggressive childhood liver cancer. Cancer Cell 2008; 14: 471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34Jin ZH, Yang RJ, Dong B, Xing BC. Progenitor gene DLK1 might be an independent prognostic factor of liver cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2008; 8: 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Floridon C, Jensen CH, Thorsen P, Nielsen O, Sunde L, Westergaard JG et al. Does fetal antigen 1 (FA1) identify cells with regenerative, endocrine and neuroendocrine potentials? A study of FA1 in embryonic, fetal, and placental tissue and in maternal circulation. Differentiation 2000; 66: 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Yanai H, Nakamura K, Hijioka S, Kamei A, Ikari T, Ishikawa Y et al. Dlk-1, a cell surface antigen on foetal hepatic stem/progenitor cells, is expressed in hepatocellular, colon, pancreas and breast carcinomas at a high frequency. J Biochem 2010; 148: 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37Falix FA, Aronson DC, Lamers WH, Hiralall JK, Seppen J. DLK1, a serum marker for hepatoblastoma in young infants. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012; 59: 743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Chacón MR, Miranda M, Jensen CH, Fernández-Real JM, Vilarrasa N, Gutiérrez C et al. Human serum levels of fetal antigen 1 (FA1/Dlk1) increase with obesity, are negatively associated with insulin sensitivity and modulate inflammation in vitro. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1122–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Kessler S, Simon Y, Gemperlein K, Gianmoena K, Cadenas C, Zimmer V et al. Fatty acid elongation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2014; 15: 5762–5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Simon Y, Kessler S.M, Gemperlein K, Bohle R.M, Müller R, Haybaeck J, Kiemer A.K. Elevated free cholesterol as a hallmark of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in p62/insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2-2 transgenic animals. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 17839–17850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Laggai S, Simon Y, Ranssweiler T, Kiemer AK, Kessler SM. Rapid chromatographic method to decipher distinct alterations in lipid classes in NAFLD/NASH. World J Hepatol 2013; 5: 558–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Zhu NL, Asahina K, Wang J, Ueno A, Lazaro R, Miyaoka Y et al. Hepatic stellate cell-derived delta-like homolog 1 (DLK1) protein in liver regeneration. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, Jin WK, Ye Q, Jia H et al. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Okamoto H, Yasui K, Zhao C, Arii S, Inazawa J. PTK2 and EIF3S3 genes may be amplification targets at 8q23-q24 and are associated with large hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology 2003; 38: 1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Heselmeyer K, Macville M, Schröck E, Blegen H, Hellström A-C, Shah K et al. Advanced-stage cervical carcinomas are defined by a recurrent pattern of chromosomal aberrations revealing high genetic instability and a consistent gain of chromosome arm 3q. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1997; 19: 233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Ahn S-M, Jang SJ, Shim JH, Kim D, Hong S-M, Sung CO et al. Genomic portrait of resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: Implications of RB1 and FGF19 aberrations for patient stratification. Hepatology 2014; 60: 1972–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Sinha S, Singh RK, Bhattacharya N, Mukherjee N, Ghosh S, Alam N et al. Frequent alterations of LOH11CR2A, PIG8 and CHEK1 genes at chromosomal 11q24.1-24.2 region in breast carcinoma: clinical and prognostic implications. Mol Oncol 2011; 5: 454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48Lee TK, Poon RTP, Yuen AP, Man K, Yang ZF, Guan XY et al. Rac activation is associated with hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 5082–5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Rassool FV, Gaymes TJ, Omidvar N, Brady N, Beurlet S, Pla M et al. Reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and error-prone repair: a model for genomic instability with progression in myeloid leukemia? Cancer Res 2007; 67: 8762–8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Ogrunc M, Di Micco R, Liontos M, Bombardelli L, Mione M, Fumagalli M et al. Oncogene-induced reactive oxygen species fuel hyperproliferation and DNA damage response activation. Cell Death Differ 2014; 21: 998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Pasi CE, Dereli-Öz A, Negrini S, Friedli M, Fragola G, Lombardo A et al. Genomic instability in induced stem cells. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18: 745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Myant KB, Scopelliti A, Haque S, Vidal M, Sansom OJ, Cordero JB. Rac1 drives intestinal stem cell proliferation and regeneration. Cell Cycle 2013; 12: 2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Gonzalez-Santiago L, Suarez Y, Zarich N, Muaoz-Alonso MJ, Cuadrado A, Martinez T et al. Aplidin® induces JNK-dependent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells via alteration of glutathione homeostasis, Rac1 GTPase activation, and MKP-1 phosphatase downregulation. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Akunuru S, Palumbo J, Zhai QJ, Zheng Y. Rac1 targeting suppresses human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cancer stem cell activity. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e16951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Wang P, Chen L, Zhang J, Chen H, Fan J, Wang K et al. Methylation-mediated silencing of the miR-124 genes facilitates pancreatic cancer progression and metastasis by targeting Rac1. Oncogene 2014; 33: 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Wang SM, Ooi LLPJ, Hui KM. Upregulation of Rac GTPase-activating protein 1 Is significantly associated with the early recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 6040–6051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Kessler SM, Laggai S, Barghash A, Helms V, Kiemer AK. Lipid metabolism signatures in NASH-Associated HCC-letter. Cancer Res 2014; 74: 2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Diesel B, Hoppstädter J, Hachenthal N, Zarbock R, Cavelius C, Wahl B et al. Activation of Rac1 GTPase by nanoparticulate structures in human macrophages. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2013; 84: 315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Fridlyand J, Dimitrov P. aCGH: classes and functions for array comparative genomic hybridization data. R package version 2010; 1. [Google Scholar]

- 60van de Wiel MA, Kim KI, Vosse SJ, van Wieringen WN, Wilting SM, Ylstra B. CGHcall: calling aberrations for array CGH tumor profiles. Bioinformatics 2007; 23: 892–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Haybaeck J, Zeller N, Wolf MJ, Weber A, Wagner U, Kurrer MO et al. A lymphotoxin-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2009; 16: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Fröhlich H, Speer N, Poustka A, Beißbarth T. GOSim - an R-package for computation of information theoretic GO similarities between terms and gene products. BMC Bioinformatics 2007; 8: 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics 2004; 5: 557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Roessler S, Jia H-L, Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye Q-H, Lee J-S et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 10202–10212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP et al. Molecular classification of cancer: Class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science 1999; 286: 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Dreos R, Ambrosini G, Périer RC, Bucher P. The eukaryotic promoter database: expansion of EPDnew and new promoter analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: D92–D96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.