Summary

Bacterial secretion systems play a central role in interfering with host inflammatory responses to promote replication in tissue sites. Many intracellular bacteria utilize secretion systems to promote their uptake and survival within host cells. An intracellular niche can help bacteria avoid killing by phagocytic cells, and may limit host sensing of bacterial components. Secretion systems can also play an important role in limiting host sensing of bacteria, by translocating proteins that disrupt host immune signaling pathways. Extracellular bacteria, on the other hand, utilize secretion systems to prevent uptake by host cells and maintain an extracellular niche. Secretion systems, in this case, limit sensing and inflammatory signaling which can occur as bacteria replicate and release bacterial products in the extracellular space. In this review, we will cover the common mechanisms used by intracellular and extracellular bacteria to modulate innate immune and inflammatory signaling pathways, with a focus on translocated proteins of the type III and type IV secretion systems.

Introduction

Pathogens constantly evolve mechanisms to overcome host restriction. A major virulence strategy used by Gram-negative bacterial pathogens to overcome host defenses is the assembly of specialized secretion systems in the cell envelope. Secretion systems (Type I-VIII) enable bacteria to translocate proteins, DNA and anti-microbial molecules directly into recipient cells. Although some secretion systems allow bacteria to translocate substrates into other bacteria, this review will focus on type III and type IV secretion systems, that translocate substrates directly into eukaryotic hosts. Translocated proteins manipulate various host cell processes such as phagocytosis, host cell sensing and inflammatory signaling as well as host transcription and translation, which ultimately promote a successful bacterial infection.

Type III secretion systems (T3SS) are composed of needle-like protein polymer structures that form a conduit to transfer proteins from the bacterium into the host cell. The tip of the needle aids in the delivery of the translocon components, or the pore complex into the host cell membrane (Cornelis, 2006). Type IV secretion systems are also large macromolecular complexes that span the inner and outer membrane of bacteria without a clear division between complex and pore forming components. T4SS are evolutionarily related to bacterial conjugation systems and may function by direct penetration of complex components into the host cell membrane (Kubori et al., 2014).

Some bacterial pathogens flourish in the presence of a host immune response, and may trigger host inflammatory pathways to promote their own growth. Other pathogens are cleared by the host response, and take great measures to limit host inflammation. Proteins translocated by secretion systems play a major role in modulating the host immune response in a way that is beneficial to the bacterial pathogen. This review will focus on the mechanisms that Type III and Type IV translocated proteins utilize to modulate host inflammation, at the levels of sensing, signaling, and interference with host transcription and translation (Table 1).

| Pathogen | Translocated Substrate | Host proteins/pathways targeted | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | YopK | - | Interacts with YopB/D and limits T3SS translocation |

Dewoody et al., 2013

Thorslund et al., 2011 Brodsky et al., 2010 |

| YopP/J | IKK, MAPK, TRAF2/TRAF6, IκB | Acetylates the IKK complex and MAPK kinases, deubiquitylates TRAF2/TRAF6 and IκB |

Mukherjee et al., 2006

Mittal et al., 2006 Sweet et al., 2007 Zhou et al., 2005 |

|

| YopM | Caspase-1 IQGAP1 |

Prevents caspase-1 processing and cell death |

LaRock and Cookson, 2012

Chung et al., 2014 |

|

| Shigella flexneri | IpaH9.8 | NEMO (component of the IKK complex) | E3 ubiquitin ligase, ubiquitylates NEMO and targets it for degradation | Ashida et al., 2010 |

| IpaH4.5 | p65 subunit of the NF-κB complex | Ubiquitylates the p65 subunit of NF-κB to limit NF-κB transcription | Wang et al., 2013 | |

| OspG | Ubiquitin pathway | Serine/theronine kinase that interacts with E2 enzymes, uses ubiquitin as a co-factor to promote kinase activity |

Kim et al., 2005

Pruneda et al., 2014 |

|

| IpaH7.8 | NLRC4 inflammasome | Ubiquitylates GLMN and targets it for degradation to promote inflammasome activation | Suzuki et al., 2014 | |

| EHEC and EPEC | NleF | NF-κB and caspases 4, 8, and 9 | Promotes nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65, promotes caspase-dependent cell death pathways |

Pallett et al., 2014

Blasche et al., 2013 |

| NleH1 | human ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3) | Prevents phosphorylation and activation of RPS3 | Wan et al., 2011 | |

| NleC | NF-κB | Zinc metalloprotease that cleaves p65 to inhibit NF-κB function |

Yen et al., 2010

Baruch et al., 2011 Pearson et al., 2011 Muhlen et al., 2011 Sham et al., 2011 |

|

| NleE | TAB2 and TAB3 (NF-κB pathway) | Methyltransferase that modifies TAB2 and TAB3 to prevent downstream degradation of IκB |

Zhang et al., 2011

Newton et al., 2010 Nadler et al., 2010 |

|

| NleB | FADD, TRADD, RIPK1 | N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase that disrupts death domains to prevent protein-protein interactions |

Li et al., 2013a

Pearson et al., 2013 |

|

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | SspH2 | Nod1 | E3 ubiquitin ligase that monoubiquitylates Nod1 | Bhavsar et al., 2013 |

| Legionella pneumophila | Leg U1 | Ubiquitin pathway | Associates with host SCF complex, E3 Ubiquitin ligase activity | Ensminger and Isberg, 2010 |

| LegAU13/AnkB | Ubiquitin pathway | Associates with host SCF complex, E3 Ubiquitin ligase activity |

Ensminger and Isberg, 2010

Price et al., 2009 |

|

| LicA | Ubiquitin pathway | Associates with host SCF complex | Ensminger and Isberg, 2010 | |

| LubX | Ubiquitin pathway | Polyubiquitination of host Clk1 | Kubori et al., 2008 | |

| LegK1 | IκB | Ser/Thr kinase that phosphorylates IκB and leads to NF-κB activation | Ge et al., 2009 | |

| LnaB | NF-κB | Induces NF-κB activation | Losick et al., 2010 | |

| RomA | Host transcription | SET domain trimethylates histone H3 (H3K14) to repress transcription | Rolando et al., 2013 | |

| Lgt1/Lgt2/Lgt3 | Host protein translation | Glycosyltransferases that modify host elongation factors | Shen et al., 2009 | |

| SidI/SidL | Host protein translation | Inteferes with translation elongation | Shen et al., 2009 | |

| Helicobacter pylori | CagA | NF-κB, Apoptosis | Activates NF-κB, degrades p53 and prevents apoptosis |

Brandt et al., 2005

Buti et al., 2011 Lamb et al., 2009 |

| Coxiella burnetii | AnkG | Apoptosis | Interacts with host protein gC1qR(p32) and prevents apoptosis | Luhrmann et al., 2010 |

| CaeA/CaeB | Apoptosis | Inhibits host apoptotic pathways | Klingenbeck et al., 2013 | |

Interference with host sensing

Bacterial components are sensed by several distinct families of proteins, called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which include Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and Nod-like receptors (NLRs) (Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002, Kawai and Akira, 2010, Fritz et al., 2006). PRRs sense bacterial components that are conserved between pathogens and non-pathogens, which means that host cells must distinguish between a pathogen that is capable of causing disease, and harmless microbes (Vance et al., 2009). One indication that a microbe may have pathogenic capabilities is the presence of specialized secretion systems, such as the type-III or type-IV secretion systems (T3SS, T4SS), which can be sensed either directly or as a consequence of products translocated by these systems (Auerbuch et al., 2009, Shin et al., 2008, Bergsbaken and Cookson, 2007, Brodsky et al., 2010). Bacterial secretion systems insert into host cell membranes to deliver proteins directly into the host cytoplasm, and host membrane perturbation can be sensed in the case of the T3SS (Auerbuch et al., 2009). The presence of bacterial proteins and other bacterial components, such as LPS, cell wall material, and nucleic acids within the host cytoplasm can also trigger pro-inflammatory responses (Fontana and Vance, 2011, Vance et al., 2009, Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2009, Fontana et al., 2011). Sensing triggers signaling cascades, which can lead to pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and the recruitment of immune cells to the site of infection (Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002).

While some pathogens have mechanisms to limit host immune responses, other pathogens flourish in the presence of host inflammation, and in some cases, absolutely require inflammatory responses to establish infection. One example of this is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, as host inflammation allows the microorganism to outcompete other bacterial species in the small intestine (Winter et al., 2010). Salmonella can replicate in the intestine by utilizing the terminal electron acceptor, tetrathionate, which is converted from H2S in the presence of neutrophils. Salmonella encode two T3SS, SPI-1 and SPI-2, both of which promote Salmonella-induced host inflammation (Coombes et al., 2005, Geddes et al., 2010). SPI-2 translocates several proteins that directly impact host inflammatory signaling. One example is SspH2, a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase (NEL) that activates the NLR, Nod1. Nod1 senses meso- diaminopimelic (meso-DAP) containing peptidoglycan, which is typically found in Gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan (Chamaillard et al., 2003, Girardin et al., 2003). Nod1 sensing results in NF-κB activation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that recruit phagocytes to sites of infection. Salmonella SspH2 can mono-ubiquitylate Nod1 during formation of a ternary complex with SGT1, a host cell cycle protein and NLR co-chaperone, which stabilizes the SspH2/Nod1 interaction (Bhavsar et al., 2013). Mono-ubiquitylation of Nod1 promotes ligand-independent signaling, and results in NF-κB activation (Bhavsar et al., 2013).

Many pathogens interfere with their own sensing by limiting the release of bacterial products. The regulation of translocation via the T3SS is a case in point for how pathogens can modulate the host response. In Yersinia species, the translocated YopK protein can directly interact with the YopB/D translocon, to control and limit the amount of protein translocation through the pore (Thorslund et al., 2011, Brodsky et al., 2010, Dewoody et al., 2013). The YopE protein similarly limits T3SS translocation by interfering with Rho family member function, with the consequence that the YopB/D translocon insertion is blocked as YopE accumulates in the host cell (Mejía et al., 2008). Additional Yersinia proteins also regulate translocation from the bacterial cytosol, by regulating loading of proteins into the needle complex (Marenne et al., 2003).

Interference with signaling pathways: Ubiquitylation and NF-κB signaling

Bacterial proteins commonly target host ubiquitylation and ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation to modulate signaling pathways. Proteasomal degradation in eukaryotic cells involves polyubiquitylation of a target substrate and delivery of the ubiquitylated substrate to the 26S proteasome. The first step of this pathway involves activation of an ubiquitin molecule by the host enzyme E1, which forms a thioester bond to ubiquitin and activates it for transfer in an ATP-dependent manner. Ubiquitin is then moved to E2, which are a family of ubiquitinconjugation enzymes. Finally, the thioesterified ubiquitin is transferred to a target substrate directly or with the help of E3 ubiquitin ligases (Deshaies, 1999). The SCF complex (Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex) is one type of E3 ubiquitin ligase that facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target substrate. There are a large number of F box proteins that are able to integrate into SCF complexes (also called Cullin-RING ubiquitin Ligases), with the F box proteins interacting with substrates and determining specificity. Skp1 functions as an adaptor protein and Cullin 1(Cul1) serves as a scaffold that interacts with SKP1 and RING-box-1 (RBX1) protein (Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2008).

A common mechanism that pathogens use to hijack the host ubiquitin pathway is through mimicry of host E3 ubiquitin ligases (Hicks and Galan, 2010). Various bacterial proteins contain an F-box that allows them to interact with the host ubiquitylation machinery to find specific targets for proteasomal degradation. Legionella pneumophila has a number of T4SS translocated proteins with predicted F-box motifs. Some of these F-box proteins, including LegU1, LegAU13/AnkB, and LicA, have been shown to associate with the SCF component Skp1 (Lomma et al., 2010, Price et al., 2009, Ensminger and Isberg, 2010). LegU1 and LegAU13/AnkB can also associate with Cullin 1 and show E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro (Ensminger and Isberg, 2010). The association with the SCF complex leads to polyubiquitylation of host proteins, although the consequence of this strategy is currently not known.

Another substrate of the Legionella type IV system that ubiquitylates a host protein is LubX, a member of the RING/U-box family of E3 ligases. LubX has two U-box domains that work together in order to induce ubiquitylation of their target protein (Kubori et al., 2010, Kubori et al., 2008). U-box 1 has a ligase activity while U-box 2 binds host Cdc2-like kinase 1 (Clk1) and brings it to U-box 1 to facilitate ubiquitylation (Kubori et al., 2008). The consequence of Clk1 polyubiquitylation is currently unclear.

In addition, Legionella also has unique non-F-Box containing E3 ubiquitin ligases such as the translocated protein SidC (Hsu et al., 2014). The N-terminal domain of SidC (the SidC N-terminal ubiquitin ligase, or SNL, domain) has been shown to possess a cysteine-based ubiquitin ligase activity that is required for recruitment of ubiquitin and ER proteins to the Legionella containing vacuole (Hsu et al., 2014).

Similar to SidC, many novel E3 ubiquitin ligase (NEL) proteins are substrates of T3SSs. NEL proteins contain a unique C-terminal E3 ligase domain, unrelated to previously characterized HECT and RING-finger type E3 ligases (Quezada et al., 2009). The N-terminus of NEL proteins typically contains a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain important for modulating E3 activity. Among their targets, NEL proteins can mono-ubiquitylate host NF-κB signaling proteins to alter protein interactions, and target signaling proteins for degradation (Ashida et al., 2014). Host sensing of bacterial products triggers signaling cascades that results in NF-κB activation and translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB into the nucleus, where it activates transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes. The NF-κB signaling pathway involves the addition of ubiquitin and phosphate residues to downstream adaptor proteins, first by ubiquitylation of proteins recruited to sensing molecules to form complexes, such as TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), RIP1, and RIP2 (Kawai and Akira, 2010). Polyubiquitin chains recruit the TGFß-activating kinase 1 (TAK1) binding protein 1 (TAB1) complex to activate TAK1, which phosphorylates IKKß of the IKK (IκB kinase) complex. The IKK complex phosphorylates IκB, and the E3 ligase complex SCF then ubiquitylates IκB, which targets IκB for proteasomal degradation. Degradation of IκB releases the p50/p65 NF-κB heterodimer, which translocates into the nucleus and activates transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009, Hayden and Ghosh, 2012, Ashida et al., 2014).

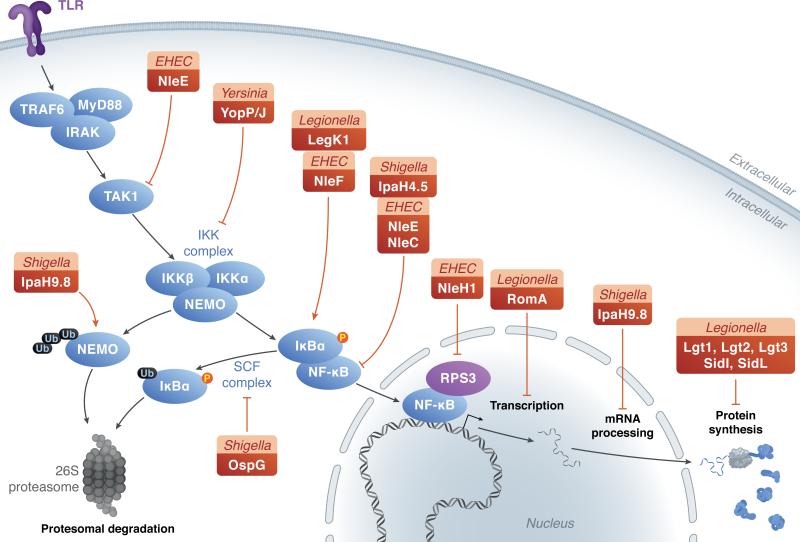

Shigella flexneri utilizes the E3 ligase IpaH9.8 to ubiquitylate NEMO and target the signaling molecule for degradation (Ashida et al., 2010) (Figure 1). NEMO is a component of the IKK complex, which is required to phosphorylate IκB. By degrading NEMO and preventing IκB phosphorylation, NF-κB activation is effectively limited. An additional Shigella translocated protein, the E3 ligase IpaH4.5, can ubiquitylate the p65 subunit of the NF-κB complex, to limit NF-κB transcription (Wang et al., 2013). OspG, in contrast, utilizes a different mechanism to inhibit NF-κB. OspG interacts with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5c, which is a member of the SCF complex, to co-opt ubiquitin as a co-factor to alter its conformation and promote kinase activity (Pruneda et al., 2014) (Figure 1). The kinase activity of OspG has been shown to inhibit NF-κB (Kim et al., 2005) and could also impact signaling either via phosphorylation, or by binding and sequestering E2 conjugating enzymes to prevent the transfer of ubiquitin to signaling molecules (Pruneda et al., 2014, Zhou et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Translocated proteins target signal transduction pathways to limit host responses.

TLR-dependent signaling and downstream gene expression can be modulated at several levels. Multiple bacterial proteins (green boxes: species, bacterial protein), are able to stimulate (dotted arrows) or inhibit (dotted --|) host innate immune responses. P: phosphorylation, Ub: ubiquitylation.

Interestingly, enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli translocate T3SS substrates that can both promote and inhibit NF-κB activation. NleF is translocated into tissue culture cells early during infection, and can promote nuclear localization of NF-κB p65 (Pallett et al., 2014). NleF can also bind to caspase 8 to inhibit apoptosis (Blasche et al., 2013). Although these activities seem distinct, there is some evidence that caspase 8 can activate NF-kB signaling (Chaudhary et al., 2000), indicating that NleF binding to caspase 8 could promote interactions with additional host signaling proteins. Following NleF translocation, NleH1, NleE and NleC are injected into host cells (Pallett et al., 2014, Mills et al., 2008), all of which inhibit NF-κB signaling. NleH1 prevents phosphorylation and activation of ribosomal protein S3 (RPS3), which can function as a non-Rel NF-κB subunit (Wan et al., 2011, Wan et al., 2007). NleC is a zinc metalloprotease that cleaves the p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-κB to block function and prevent NF-kB-dependent gene expression (Yen et al., 2010, Baruch et al., 2011, Pearson et al., 2013). NleE is a methyltransferase that inhibits TGF-ß-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) activity by methylating TAB2 and TAB3, which prevents downstream degradation of IκBα (Pearson et al., 2013, Newton et al., 2010, Nadler et al., 2010, Pallett et al., 2014). Together, these proteins can inhibit movement of NF-κB from the host cell cytoplasm into the nucleus to prevent transcription of target genes (Figure 1).

When overexpressed in mammalian cells, the Legionella eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr kinase LegK1 activates NF-κB by phosphorylating its inhibitor IκB (Ge et al., 2009). This phosphorylation is independent of the host kinase IKK, as well as the upstream signaling proteins TRAF2/TRAF6, TAK1 and MEKK3 (Ge et al., 2009). Ectopic expression of Legionella LnaB also strongly induces NF-κB activation, and mutants lacking this protein show lowered ability to activate NF-κB (Losick et al., 2010). A small putative coiled-coil domain of LnaB is required for NF-κB activation but it is not known if LnaB directly acts on NF-κB or if the activation is the consequence of the protein being sensed by host receptors (Losick et al., 2010). Helicobacter pylori CagA also shows a similar activation of NF-κB when expressed ectopically in mammalian cells (Brandt et al., 2005). CagA associates with and ubiquitylates the host protein TAK1 (Lys63-linked ubiquitylation), resulting in the activation of its kinase activity (Lamb et al., 2009). This ubiquitilation has been shown to enhance TAK-1 dependent activation of NF-κB in host cells (Lamb et al., 2009).

Pathogenic Yersinia translocate proteins (Yops) into host cells, some of which directly target host inflammatory signaling pathways. Yersinia species translocate the YopP/J acetyltransferase into host cells, to acetylate the IKK complex and MAPK kinases (MKKs), thus preventing phosphorylation and subsequent signaling (Mukherjee et al., 2006, Mittal et al., 2006) (Figure 1). Structurally, YopJ contains a domain showing sequence similarity to a cysteine protease, which has been described to have deubiquitinating and deSUMOlation activity (Orth et al., 2000, Zhou et al., 2005, Sweet et al., 2007). Mutation of the predicted critical cysteine residue in the protease domain of YopJ was sufficient to restore poly-ubiquitylation to IκBα, indicating that YopJ may inhibit ubiquitylation of IκBα, and also additional signaling molecules such as TRAF3 and TRAF6 (Zhou et al., 2005, Sweet et al., 2007). Although in vitro assays showed that purified YopJ could cleave ubiquitin (Zhou et al., 2005), it remained unclear if this occurred during infection. More recent studies have showed the same cysteine residue of YopJ is responsible for acetylation of TAK-1 and RICK (Paquette et al., 2012, Meinzer et al., 2012), two signaling adaptors upstream of IκBα. Upstream acetylation of signaling molecules could prevent downstream ubiquitylation of IκBα, and may help explain the conflicting results regarding YopJ function.

Hijacking host transcription and translation

It has become increasingly evident that a number of pathogens interfere with host transcription directly by acting on RNA polymerase (Lutay et al., 2013) or through manipulation of host epigenetic regulatory factors (Bierne and Cossart, 2012). Some bacteria achieve this by encoding enzymes that modify the host chromatin, and are termed ‘nucleomodulins’(Bierne and Cossart, 2012).

Various pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Listeria monocytogenes, Shigella flexneri and Helicobacter pylori induce histone modifications and alter expression of innate immune genes. Modification of histones, specifically histone methylation, is mediated by proteins that contain SET domains (suppressor of variegation, enhancer of zest, and trithorax domain). SET domains, typically found in eukaryotic methyltransferases, consist of a 130 amino acid sequence and have enzymatic activities that methylate histone lysine residues (Xiao et al., 2003). Chlamydia pneumonia and Chlamydia trachomatis encode proteins that have SET-domains that methylate histones H2A, H3 and H4 (Pennini et al., 2010).

Legionella pneumophila also uses a similar strategy to modify the host transcriptional machinery. The translocated protein LegAS4 (in L. pneumophila Philadelphia strain), which contains a SET domain, localizes to host nucleolus during infection (Li et al., 2013b). The SET domain of LegAS4 is catalytically active and has been shown to specifically activate rDNA transcription (Li et al., 2013b). Interestingly, RomA, the equivalent protein in the L. pneumophila Paris strain, localizes to the nucleus during infection and tri-methylates histone H3 at lysine 14 (H3K14) (Rolando et al., 2013). H3K14 is typically a site for acetylation, which is a marker for transcriptional activation. RomA induced methylation at H3K14 thus prevents this acetylation from taking place and leads to genome wide transcriptional repression. The study showed that this repression mainly affected innate immune genes, including pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF and IL-6) and pattern-recognition receptors such as TLR5 and the Nod-like receptor Nalp3 (Rolando et al., 2013). This observation however, contradicts observation by other groups, who demonstrated that the presence of Legionella translocated proteins significantly induces the transcription of various pro-inflammatory cytokines to levels significantly higher than avirulent mutants that lack the T4SS (Shin et al., 2008, Fontana et al., 2011, Barry et al., 2013, Asrat et al., 2014).

In addition to modifying host transcription, Legionella also hijacks the host translation machinery and efficiently interferes with protein synthesis. This is the result of a bacterial-driven mechanism, which targets eukaryotic elongation factors (Shen et al., 2009, Belyi et al., 2006) as well as a host-driven mechanism, which targets cap-dependent translation initiation (Ivanov and Roy, 2013). The bacterial-driven translation inhibition is mediated by at least 5 translocated proteins that target host elongation factors eEF1A and eEF1Bγ. Three of these proteins, Lgt1, Lgt2, Lgt3, are glycosyltransferases that modify eEF1A in vitro and in vivo (Shen et al., 2009, Fontana et al., 2011), while the mechanisms of the other proteins are not fully understood. A recent study identified two additional proteins, Lpg0208 and Lpg1489 predicted to block protein synthesis. Deletion of the genes for these proteins in a background that lacks the 5 elongation inhibitors showed no additional effect on protein synthesis (Barry et al., 2013).

In addition to elongation inhibition induced by Legionella-translocated proteins, host cells down-regulate cap-dependent translation initiation following Legionella infection by targeting the mTOR pathway (Ivanov and Roy, 2013). This mechanism of translation inhibition is not dependent on a particular Legionella protein but is a host response to damage, dependent on the presence of the bacterial T4SS (Ivanov and Roy, 2013). In resting cells, the translation initiation factor eIF4E is bound by its inhibitor 4E-BP. Activation of mTOR leads to phosphorylation of 4E-BP, which frees eIF4E from its inhibitor, allowing it to associate with mRNA cap to initiate translation. Upon detection of ‘pathogen-signatures’, macrophages stimulate ubiquitylation and degradation of proteins in the mTOR pathway, including mTOR and AKT. During Legionella infection, suppression of the mTOR pathway prevents 4E-BP phosphorylation leading to a reduction in cap-dependent translation initiation (Ivanov and Roy, 2013).

An additional mechanism of interfering with cytokine production can occur by blocking post-transcriptional processing of cytokine mRNA. The Shigella protein IpaH9.8, which has E3 ligase activity and can bind NEMO to inhibit NF–κB signaling, has also been shown to ubiquitylate an essential splicing factor U2AF35 (Okuda et al., 2005, Seyedarabi et al., 2010, Ashida et al., 2010) resulting in U2AF35 degradation. U2AF35 splicing contributes to the processing of pre-mRNA encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, which means that IpaH9.8-mediated degradation of U2AF35 can reduce the levels of cytokine translation.

Interference with inflammasome activation

Upon infection, host cells assemble cytosolic multiprotein complexes called inflammasomes that activate inflammatory caspases, resulting in proteolytic cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Martinon et al., 2002). Recent studies have highlighted the diversity of inflammasomes, many of which consist of a complex of an NLR family member, an adaptor protein (ASC) and an inflammatory caspase. The activation of an inflammasome is followed by pyroptosis, a rapid form of host cell death (detailed review on this topic can be found in von Moltke et al., 2013, (Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2014) Chen and Nunez, 2010). One of the most studied inflammasome complexes is the NLRC4/NAIP5 inflammasome, which senses the presence of cytosolic flagellin and related proteins (Kofoed and Vance, 2011). The NLRC4 inflammasome is assembled in response to various pathogens, such as Salmonella, Shigella, Legionella and Pseudomonas. In addition to flagellin, detection of the inner rod proteins of the T3SS by NLRC4 can trigger assembly of this inflammasome, leading to Caspase 1 activation and cell death (Miao et al., 2010, Kofoed and Vance, 2011, Yang et al., 2013).

Pathogens have evolved various mechanisms to overcome restriction induced by inflammasome activation. Shigella flexneri utilizes the E3 ligase IpaH7.8 to ubiquitylate glomulin/flagellar-associated protein 68 (GLMN), which is involved in inhibiting NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasome activation by an unclear mechanism (Suzuki et al., 2014). Ubiquitylation of GLMN targets the protein for degradation, which promotes inflammasome activation and host cell death. Expression of IpaH7.8 heightened bacterial CFUs, indicating inflammation and possibly a host cell death pathway promote bacterial growth.

The Yersinia translocated protein YopK can inhibit pyroptosis and Caspase 1 activation following translocation into the host cytosol, in a manner dependent on the presence of the T3SS translocon (Brodsky et al., 2010). YopK can associate with YopB and YopD, the Yersinia proteins that oligomerize to form the translocon in host cells, indicating that YopK could play some role in regulating secretion through the T3SS pore (Dewoody et al., 2013, Zwack et al., 2015). It remains unclear if YopK binds to the translocon following insertion in the host plasma membrane, or if there are host cytosolic interactions between YopK, YopB, and YopD (Zwack et al., 2015, Brodsky et al., 2010, Kwuan et al., 2013). The essential Yersinia virulence protein YopM can also interfere with Caspase 1 function, by directly binding to the protein to inhibit its processing and subsequent cell death (LaRock and Cookson, 2012). Multiple YopM isoforms exist in Yersinia, and the IQGAP1 large scaffolding protein is also required for YopM/caspase-1 interactions in some strains, such as the Y. pestis KIM strain (Chung et al., 2014).

During EHEC infection, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated through a unique mechanism that involves detection of bacterial RNA:DNA hybrids in the host cytosol (Kailasan Vanaja et al., 2014). Consistent with this, E. coli mutants that lack RNase H, the enzyme that degrades such hybrids, show elevated levels of NLRP3 inflammasomes (Kailasan Vanaja et al., 2014). Cytoplasmic delivery of the T3SS needle protein from EHEC (Eprl) has also been shown to activate the NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome, similar to what is seen for S. typhimurim (PrgI) and S. flexneri (MxiH) needle proteins (Yang et al., 2013).

Challenge of macrophages with Legionella pneumophila triggers inflammasome activation via multiple mechanisms (von Moltke et al., 2013). Translocation of flagellin, possibly through the type IV secretion system, leads to activation of the Naip5 inflammasome, which in turn triggers pyroptosis (Case et al., 2009, Molofsky et al., 2006, Ren et al., 2006). Virulent strains of Legionella that contain a functional type IV secretion system also induce a rapid, flagellin-independent Caspase-11 inflammasome activation, followed by IL-1α release and pyroptotic cell death (Case et al., 2013, Casson et al., 2013, Kayagaki et al., 2011, Kayagaki et al., 2013). To date, there are no known Legionella proteins that directly inhibit or overcome inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis, possibly due to the fact that the bacterium was selected for growth in amoebae, which lacks the pressure necessary to select for bypass of this pathway.

Interfering with apoptotic cell death

Bacterial translocated proteins can target cell death pathways directly or indirectly. The Gram-negative human pathogen Coxiella burnetti interferes with host apoptotic pathways and promotes its survival via multiple mechanisms (Voth et al., 2007, Vazquez and Colombo, 2010). The type IV translocated protein AnkG interacts with a host cytoplasmic protein gC1qR (p32) and prevents apoptosis (Luhrmann et al., 2010). Two additional Coxiella proteins, CaeA and CaeB (C. burnetii anti-apoptotic effectors), have also been shown to inhibit host apoptotic pathways. CaeB regulates this pathway through its interaction with mitochondria. The mechanism by which CaeA inhibits apoptosis has not been determined (Klingenbeck et al., 2013).

Helicobacter pylori CagA has also been implicated in modulating various host cell death pathways. CagA targets apoptosis-stimulation protein p53 (ASPP2) and subverts its tumor suppressor function, preventing apoptosis (Buti et al., 2011). CagA directly interacts with ASPP2 leading to recruitment and degradation of p53. Recent reports suggested that degradation of p53 by Helicobacter is controlled by another tumor suppressor p14ARF, and this degradation depends on the efficiency of the Helicobacter type IV secretion system that delivers CagA. The regulation of p53 stability also depends on the host E3 ubiquitin ligases HDM2 and ARF-BP1 in Helicobacter-infected cells (Wei et al., 2014).

Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic E. coli translocate several substrates that can inhibit apoptotic cell death. NleB can bind to the death domain of several host proteins, such as FADD, TRADD, and RIPK1, and transfer N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to a conserved arginine residue (Li et al., 2013a, Pearson et al., 2013). This novel GlcNAcylation of death domains prevented protein-protein interactions, thereby disrupting signaling cascades to prevent apoptosis. Additional signaling cascades, such as NF-kB were also disrupted by the inactivation of death domain-containing proteins (Li et al., 2013a). There is also evidence that NleH1 can interfere with cell death pathways, through interactions with Bax inhibitor-1 (BI-1) (Hemrajani et al., 2010). NleH1 expression inhibited caspase-3 activation and apoptosis, leading to survival of EPEC infected cells.

Conclusions

For both intracellular and extracellular pathogens, bacterial proteins have adapted to target host cell signaling pathways to modulate the host immune response. In the context of some infections, bacteria may benefit from host inflammation, either because bacteria can replicate within inflammatory cells, or because inflammation can alter the environment in a way that promotes bacterial growth. One example of this occurs during S. typhimurium intestinal infections, where inflammation generates the compound tetrathionate, which the bacterium utilizes to outcompete the microbiota (Winter et al., 2010, Thiennimitr et al., 2011). In some cases, a single bacterium may secrete proteins that are capable of both inhibiting and inducing host responses, and the inflammatory outcome may depend on the abundance of one effector relative to another. Kinetics of secretion, and injection into different cell types, can also tip the balance between a pro- or anti-inflammatory response.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Isberg laboratory for advice with this submission. Work from our laboratory was supported by NIAID awards AI10684 and AI113211 and by HHMI. SA is an HHMI International Graduate Scholar. KMD is an American Cancer Society-Ellison Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow (PF-13-360-01-MPC).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- ASHIDA H, KIM M, SASAKAWA C. Exploitation of the host ubiquitin system by human bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:399–413. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASHIDA H, KIM M, SCHMIDT-SUPPRIAN M, MA A, OGAWA M, SASAKAWA C. A bacterial E3 ubiquitin ligase IpaH9.8 targets NEMO/IKKgamma to dampen the host NF-kappaB-mediated inflammatory response. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:66–73. doi: 10.1038/ncb2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASRAT S, DUGAN AS, ISBERG RR. The frustrated host response to Legionella pneumophila is bypassed by MyD88-dependent translation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004229. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUERBUCH V, GOLENBOCK D, ISBERG R. Innate immune recognition of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III secretion. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000686. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRY KC, FONTANA MF, PORTMAN JL, DUGAN AS, VANCE RE. IL-1alpha Signaling Initiates the Inflammatory Response to Virulent Legionella pneumophila In Vivo. J Immunol. 2013;190:6329–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARUCH K, GUR-ARIE L, NADLER C, KOBY S, YERUSHALMI G, BEN-NERIAH Y, YOGEV O, SHAULIAN E, GUTTMAN C, ZARIVACH R, ROSENSHINE I. Metalloprotease type III effectors that specfically cleave JNK and NF-κB. EMBO J. 2011;30:221–31. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELYI Y, NIGGEWEG R, OPITZ B, VOGELSGESANG M, HIPPENSTIEL S, WILM M, AKTORIES K. Legionella pneumophila glucosyltransferase inhibits host elongation factor 1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16953–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601562103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGSBAKEN T, COOKSON B. Macrophage activation redirects yersinia-infected host cell death from apoptosis to caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e161. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHAVSAR A, BROWN N, STOEPEL J, WIERMER M, MARTIN D, HSU K, IMAMI K, ROSS C, HAYDEN M, FOSTER L, LI X, HIETER P, FINLAY B. The Salmonella type III effector SspH2 specifically exploits the NLR co-chaperone activity of SGT1 to subvert immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003518. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIERNE H, COSSART P. When bacteria target the nucleus: the emerging family of nucleomodulins. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:622–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLASCHE S, MÖRTI M, STEUBER H, SISZLER G, NISA S, SCHWARZ F, LAVRIK I, GRONEWOLD T, MASKOS K, DONNENBERG M, ULLMANN D, UETZ P, KÖGL M. The E. coli effector protein NleF is a caspase inhibitor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANDT S, KWOK T, HARTIG R, KONIG W, BACKERT S. NF-kappaB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRODSKY I, PALM N, SADANAND S, RYNDAK M, SUTTERWALA F, FLAVELL R, BLISKA J, MEDZHITOV R. A Yersinia effector protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:376–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTI L, SPOONER E, VAN DER VEEN AG, RAPPUOLI R, COVACCI A, PLOEGH HL. Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) subverts the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP2) tumor suppressor pathway of the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106200108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASE CL, KOHLER LJ, LIMA JB, STROWIG T, DE ZOETE MR, FLAVELL RA, ZAMBONI DS, ROY CR. Caspase-11 stimulates rapid flagellin-independent pyroptosis in response to Legionella pneumophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1851–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211521110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASE CL, SHIN S, ROY CR. Asc and Ipaf Inflammasomes direct distinct pathways for caspase-1 activation in response to Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1981–91. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01382-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASSON CN, COPENHAVER AM, ZWACK EE, NGUYEN HT, STROWIG T, JAVDAN B, BRADLEY WP, FUNG TC, FLAVELL RA, BRODSKY IE, SHIN S. Caspase-11 activation in response to bacterial secretion systems that access the host cytosol. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003400. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMAILLARD M, HASHIMOTO M, HORIE Y, MASUMOTO J, QIU S. An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:702–707. doi: 10.1038/ni945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAUDHARY P, EBY M, JASMIN A, KUMAR A, LIU L, HOOD L. Activation of the NF-kappaB pathway by caspase 8 and its homologs. Oncogene. 2000;19:4451–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN GY, NUNEZ G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–37. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHUNG L, PHILIP N, SCHMIDT V, KOLLER A, STROWIG T, FLAVELL R, BRODSKY I, BLISKA J. IQGAP1 is important for activation of caspase-1 in macrophages and is targeted by Yersinia pestis type III effector YopM. MBio. 2014;5:e01402–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01402-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOMBES B, COBURN B, POTTER A, GOMIS S, MIRAKHUR K, LI Y, FINLAY B. Analysis of the contribution of Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 to enteric disease progression using a novel bovine ileal loop model and a murine model of infectious enterocolitis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7161–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7161-7169.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORNELIS G. The type III secretion injectisome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:811–25. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNHA LD, ZAMBONI DS. Subversion of inflammasome activation and pyroptosis by pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:76. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DESHAIES RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEWOODY R, MERRITT P, MARKETON M. YopK controls both rate and fidelity of Yop translocation. Mol Microbiol. 2013;87:301–17. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENSMINGER AW, ISBERG RR. E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and targeting of BAT3 by multiple Legionella pneumophila translocated substrates. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3905–19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00344-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FONTANA M, VANCE R. Two signal models in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:26–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FONTANA MF, BANGA S, BARRY KC, SHEN X, TAN Y, LUO ZQ, VANCE RE. Secreted bacterial effectors that inhibit host protein synthesis are critical for induction of the innate immune response to virulent Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001289. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRITZ J, FERRERO R, PHILPOTT D, GIRARDIN S. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GE J, XU H, LI T, ZHOU Y, ZHANG Z, LI S, LIU L, SHAO F. A Legionella type IV effector activates the NF-kappaB pathway by phosphorylating the IkappaB family of inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13725–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEDDES K, RUBINO S, STREUTKER C, CHO J, MAGALHAES J, LE BOURHIS L, SELVANANTHAM T, GIRARDIN S, PHILPOTT D. Nod1 and Nod2 regulation of inflammation in the Salmonella colitis model. Infect Immun. 2010;78:5107–15. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00759-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIRARDIN S, BONECA I, CARNEIRO L, ANTIGNAC A, JÉHANNO M. NOD1 detects a unique muropeptide from Gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science. 2003;300:1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYDEN M, GHOSH S. NF-κB, the first quarter-century: remarkable progress and outstanding questions. Genes Dev. 2012;26:203–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.183434.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEMRAJANI C, BERGER C, ROBINSON K, MARCHÉS O, MOUSNIER A, FRANKEL G. NleH effectors interact with Bax inhibitor-1 to block apoptosis during enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:3129–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911609106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HICKS SW, GALAN JE. Hijacking the host ubiquitin pathway: structural strategies of bacterial E3 ubiquitin ligases. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSU F, LUO X, QIU J, TENG YB, JIN J, SMOLKA MB, LUO ZQ, MAO Y. The Legionella effector SidC defines a unique family of ubiquitin ligases important for bacterial phagosomal remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10538–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402605111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IVANOV SS, ROY CR. Pathogen signatures activate a ubiquitination pathway that modulates the function of the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR. Nat Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ni.2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANEWAY C, MEDZHITOV R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAILASAN VANAJA S, RATHINAM VA, ATIANAND MK, KALANTARI P, SKEHAN B, FITZGERALD KA, LEONG JM. Bacterial RNA:DNA hybrids are activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7765–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400075111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWAI T, AKIRA S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAYAGAKI N, WARMING S, LAMKANFI M, VANDE WALLE L, LOUIE S, DONG J, NEWTON K, QU Y, LIU J, HELDENS S, ZHANG J, LEE WP, ROOSE-GIRMA M, DIXIT VM. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–21. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAYAGAKI N, WONG MT, STOWE IB, RAMANI SR, GONZALEZ LC, AKASHITAKAMURA S, MIYAKE K, ZHANG J, LEE WP, MUSZYNSKI A, FORSBERG LS, CARLSON RW, DIXIT VM. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science. 2013;341:1246–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1240248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM D, LENZEN G, PAGE A, LEGRAIN P, SANSONETTI P, PARSOT C. The Shigella flexneri effector OspG interferes with innate immune responses by targeting ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:14046–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504466102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLINGENBECK L, ECKART RA, BERENS C, LUHRMANN A. The Coxiella burnetii type IV secretion system substrate CaeB inhibits intrinsic apoptosis at the mitochondrial level. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:675–87. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOFOED EM, VANCE RE. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature. 2011;477:592–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUBORI T, HYAKUTAKE A, NAGAI H. Legionella translocates an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has multiple U-boxes with distinct functions. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1307–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUBORI T, KOIKE M, BUI X, HIGAKI S, AIZAWA S, NAGAI H. Native structure of a type IV secretion system core complex essential for Legionella pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:11804–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404506111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUBORI T, SHINZAWA N, KANUKA H, NAGAI H. Legionella metaeffector exploits host proteasome to temporally regulate cognate effector. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWUAN L, ADAMS W, AUERBUCH V. Impact of host membrane pore formation by the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III secretion system on the macrophage innate immune response. Infect Immun. 2013;81:905–14. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01014-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMB A, YANG XD, TSANG YH, LI JD, HIGASHI H, HATAKEYAMA M, PEEK RM, BLANKE SR, CHEN LF. Helicobacter pylori CagA activates NF-kappaB by targeting TAK1 for TRAF6-mediated Lys 63 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1242–9. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMKANFI M, DIXIT V. Inflammasomes: guardians of cytosolic sanctity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMKANFI M, DIXIT VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157:1013–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAROCK C, COOKSON B. The Yersinia virulence effector YopM binds caspase-1 to arrest inflammasome assembly and processing. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI S, ZHANG L, YAO Q, LI L, DONG N, RONG J, GAO W, DING X, SUN L, CHEN X, CHEN S, SHAO F. Pathogen blocks host death receptor signalling by arginine GlcNAcylation of death domains. Nature. 2013a;501:242–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI T, LU Q, WANG G, XU H, HUANG H, CAI T, KAN B, GE J, SHAO F. SETdomain bacterial effectors target heterochromatin protein 1 to activate host rDNA transcription. EMBO Rep. 2013b;14:733–40. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOMMA M, DERVINS-RAVAULT D, ROLANDO M, NORA T, NEWTON HJ, SANSOM FM, SAHR T, GOMEZ-VALERO L, JULES M, HARTLAND EL, BUCHRIESER C. The Legionella pneumophila F-box protein Lpp2082 (AnkB) modulates ubiquitination of the host protein parvin B and promotes intracellular replication. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1272–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOSICK VP, HAENSSLER E, MOY MY, ISBERG RR. LnaB: a Legionella pneumophila activator of NF-kappaB. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1083–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUHRMANN A, NOGUEIRA CV, CAREY KL, ROY CR. Inhibition of pathogeninduced apoptosis by a Coxiella burnetii type IV effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18997–9001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004380107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUTAY N, AMBITE I, GRONBERG HERNANDEZ J, RYDSTROM G, RAGNARSDOTTIR B, PUTHIA M, NADEEM A, ZHANG J, STORM P, DOBRINDT U, WULLT B, SVANBORG C. Bacterial control of host gene expression through RNA polymerase II. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2366–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI66451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARENNE M, JOURNET L, MOTA L, CORNELIS G. Genetic analysis of the formation of the Ysc-Yop translocation pore in macrophages by Yersinia enterocolitica: role of LcrV, YscF and YopN. Microb Pathog. 2003;35:243–58. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTINON F, BURNS K, TSCHOPP J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEINZER U, BARREAU F, ESMIOL-WELTERLIN S, JUNG C, VILLARD C, LÉGER T, BENMKADDEM S, BERREBI D, DUSSAILLANT M, ALNABHANI Z, ROY M, BONACORSI S, WOLF-WATZ H, PERROY J, OLLENDORFF V, HUGOT J. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis effector YopJ subverts the Nod2/RICK/TAK1 pathway and activates caspase-1 to induce intestinal barrier dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:337–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEJÍA E, BLISKA J, VIBOUD G. Yersinia controls type III effector delivery into host cells by modulating Rho activity. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIAO EA, MAO DP, YUDKOVSKY N, BONNEAU R, LORANG CG, WARREN SE, LEAF IA, ADEREM A. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3076–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLS E, BARUCH K, CHARPENTIER X, KOBI S, ROSENSHINE I. Real-time analysis of effector translocation by the type III secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherchia coli. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITTAL R, PEAK-CHEW S, MCMAHON H. Acetylation of MEK2 an I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:18574–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLOFSKY AB, BYRNE BG, WHITFIELD NN, MADIGAN CA, FUSE ET, TATEDA K, SWANSON MS. Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1093–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUKHERJEE S, KEITANY G, LI Y, WANG Y, BALL H, GOLDSMITH E, ORTH K. Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science. 2006;312:1211–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1126867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NADLER C, BARUCH K, KOBI S, MILLS E, HAVIV G, FARAGO M, ALKALAY I, BARTFELD S, MEYER T, BEN-NERIAH Y, ROSENSHINE I. The type III secretion effector NleE inhibits NF-kappaB activation. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000743. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON H, PEARSON J, BADEA L, KELLY M, LUCAS M, HOLLOWAY G, WAGSTAFF K, DUNSTONE M, SLOAN J, WHISSTOCK J, KAPER J, ROBINS-BROWNE R, JANS D, FRANKEL G, PHILLIPS A, COULSON B, HARTLAND E. The type III effectors NleE and NleB from enteropathogenic E. coli and OspZ from Shigella block nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB p65. 2010;6:e1000898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKUDA J, TOYOTOME T, KATAOKA N, OHNO M, ABE H, SHIMURA Y, SEYEDARABI A, PICKERSGILL R, SASAKAWA C. Shigella effector IpaH9.8 binds to splicing factor U2AF(35) to modulate host immune responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:531–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORTH K, XU Z, MUDGETT M, BAO Z, PALMER L, BLISKA J, MANGEL W, STASKAWICZ B, DIXON J. Disruption of signaling by Yersinia effector YopJ, a ubiquitinlike protein protease. Science. 2000;290:1594–7. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALLETT M, BERGER C, PEARSON J, HARTLAND E, FRANKEL G. The type III secretion effector NleF of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli activates NF-kB early during infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4878–88. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02131-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAQUETTE N, CONLON J, SWEET C, RUS F, WILSON L, PEREIRA A, ROSADINI C, GOUTAGNY N, WEBER A, LANE W, SHAFFER S, MANIATIS S, FITZGERALD K, STUART L, SILVERMAN N. Serine/threonine acetylation of TGFß-activated kinase (TAK1_ by Yersinia pestis YopJ inhibits innate immune signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12710–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008203109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON J, GIOGHA C, ONG S, KENNEDY C, KELLY M, ROBINSON K, LUNG T, MANSELL A, RIEDMAIER P, OATES C, ZAID A, MÜHLEN S, CREPIN V, MARCHES O, ANG C, WILLIAMSON N, O'REILLY L, BANKOVACKI A, NACHBUR U, INFUSINI G, WEBB A, SILKE J, STRASSER A, FRANKEL G, HARTLAND E. A type III effector antagonizes death receptor signalling during bacterial gut infection. Nature. 2013;501:247–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENNINI ME, PERRINET S, DAUTRY-VARSAT A, SUBTIL A. Histone methylation by NUE, a novel nuclear effector of the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000995. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRICE CT, AL-KHODOR S, AL-QUADAN T, SANTIC M, HABYARIMANA F, KALIA A, KWAIK YA. Molecular mimicry by an F-box effector of Legionella pneumophila hijacks a conserved polyubiquitination machinery within macrophages and protozoa. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000704. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRUNEDA J, SMITH F, DAURLE A, SWANEY D, VILLÉN J, SCOTT J, STADNYK A, LE TRONG I, STENKAMP R, KLEVIT R, ROHDE J, BRZOVIC P. E2-Ub conjugates regulate the kinase activity of Shigella effector OspG during pathogenesis. EMBO J. 2014;33:437–49. doi: 10.1002/embj.201386386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUEZADA C, HICKS S, GALÁN J, STEBBINS C. A family of Salmonella virulence factors functions as a distinct class of autoregulated E3 ubiquitin ligases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:4864–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811058106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAVID T, HOCHSTRASSER M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitinproteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–90. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REN T, ZAMBONI DS, ROY CR, DIETRICH WF, VANCE RE. Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and Naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROLANDO M, SANULLI S, RUSNIOK C, GOMEZ-VALERO L, BERTHOLET C, SAHR T, MARGUERON R, BUCHRIESER C. Legionella pneumophila effector RomA uniquely modifies host chromatin to repress gene expression and promote intracellular bacterial replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEYEDARABI A, SULLIVAN J, SASAKAWA C, PICKERSGILL R. A disulfide driven domain swap switches off the activity of Shigella IpaH9.8 E3 ligase. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:4163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN X, BANGA S, LIU Y, XU L, GAO P, SHAMOVSKY I, NUDLER E, LUO ZQ. Targeting eEF1A by a Legionella pneumophila effector leads to inhibition of protein synthesis and induction of host stress response. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:911–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIN S, CASE CL, ARCHER KA, NOGUEIRA CV, KOBAYASHI KS, FLAVELL RA, ROY CR, ZAMBONI DS. Type IV secretion-dependent activation of host MAP kinases induces an increased proinflammatory cytokine response to Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000220. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUKI S, MIMURO H, KIM M, OGAWA M, ASHIDA H, TOYOTOME T, FRANCHI L, SUZUKI M, SANADA T, SUZUKI T, TSUTSUI H, NÚN̈EZ G, SASAKAWA C. Shigella IpaH7.8 E3 ubiquitin ligase targets glomulin and activates inflammasomes to demolish macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:E4254–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324021111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWEET C, CONLON J, GOLENBOCK D, GOGUEN J, SILVERMAN N. YopJ targets TRAF proteins to inhibit TLR-mediated NF-kappaB, MAPK and IRF3 signal transduction. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2700–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIENNIMITR P, WINTER S, WINTER M, XAVIER M, TOLSTIKOV V, HUSEBY D, STERZENBACH T, TSOLIS R, ROTH J, BÄUMLER A. Intestinal inflammation allows Salmonella to use ethanolamine to compete with the microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:17480–17485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107857108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORSLUND S, EDGREN T, PETTERSSON J, NORDFEITH R, SELLIN M, IVANOVA E, FRANCIS M, ISAKSSON E, WOLF-WATZ H, FÄLLMAN M. The RACK1 signalling scaffold protein selectively interacts with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis virulence function. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALLABHAPURAPU S, KARIN M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANCE R, ISBERG R, PORTNOY D. Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAZQUEZ CL, COLOMBO MI. Coxiella burnetii modulates Beclin 1 and Bcl-2, preventing host cell apoptosis to generate a persistent bacterial infection. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:421–38. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON MOLTKE J, AYRES JS, KOFOED EM, CHAVARRIA-SMITH J, VANCE RE. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:73–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOTH DE, HOWE D, HEINZEN RA. Coxiella burnetii inhibits apoptosis in human THP-1 cells and monkey primary alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4263–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00594-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAN F, ANDERSON D, BARNITZ R, SNOW A, BIDERE N, ZHENG L, HEGDE V, LAM L, STAUDT L, LEVENS D, DEUTSCH W, LENARDO M. Ribosomal protein S3: a KH domain subunit in NF-kappaB complexes that mediates selective gene regulation. Cell. 2007;131:927–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAN F, WEAVER A, GAO X, BERN M, HARDWIDGE P, LENARDO M. IKKß phosphorylation regulates RPS3 nuclear translocation and NF-kB function during infection with Escherichia coli strain O157:H7. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:335–43. doi: 10.1038/ni.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG F, JIANG Z, LI Y, HE X, ZHAO J, YANG X, ZHU L, YIN Z, LI X, WANG X, LIU W, SHANG W, YANG Z, WANG S, ZHEN Q, ZHANG Z, YU Y, ZHONG H, YE Q, HUANG L, YUAN J. Shigella flexneri T3SS effector IpaH4.5 modulates the host inflammatory response via interaction with NF-kB p65 protein. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:474–85. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEI J, NOTO JM, ZAIKA E, ROMERO-GALLO J, PIAZUELO MB, SCHNEIDER B, ELRIFAI W, CORREA P, PEEK RM, ZAIKA AI. Bacterial CagA protein induces degradation of p53 protein in a p14ARF-dependent manner. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTER S, THIENNIMITR P, WINTER M, BUTLER B, HUSEBY D, CRAWFORD R, RUSSELL J, BEVINS C, ADAMS L, TSOLIS R, ROTH J, BÄUMLER A. Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature. 2010;467:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature09415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XIAO B, WILSON J, GAMBLIN S. SET domains and histone methylation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:699–705. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG J, ZHAO Y, SHI J, SHAO F. Human NAIP and mouse NAIP1 recognize bacterial type III secretion needle protein for inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14408–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306376110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YEN H, OOKA T, IGUCHI A, HAYASHI T, SUGIMOTO N, TOBE T. NleC, a type III secretion protease, compromises NF-kB activation by targeting p65/RelA. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001231. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU H, MONACK D, KAYAGAKI N, WERTZ I, YIN J, WOLF B, DIXIT V. Yersinia virulence factor YopJ acts as a deubiquitinase to inhibit NF-kappa B activation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1327–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Y, DONG N, HU L, SHAO F. The Shigella type three secretion system effector OspG directly and specifically binds to host ubiquitin for activation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZWACK E, SNYDER A, WYNOSKY-DOLFI M, RUTHEL G, PHILIP N, MARKETON M, FRANCIS M, BLISKA J, BRODSKY I. Inflammasome activation in response to the Yersinia type III secretion system hyperinjection of translocon proteins YopB and YopD. MBio. 2015;6:e02095–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02095-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]