Abstract

Ibrutinib (formerly PCI-32765) is a potent, covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, a kinase downstream of the B-cell receptor that is critical for B-cell survival and proliferation. In preclinical studies, ibrutinib bound to Bruton’s tyrosine kinase with high affinity, leading to inhibition of B-cell receptor signaling, decreased B-cell activation and induction of apoptosis. In clinical studies, ibrutinib has been well-tolerated and has demonstrated profound anti-tumor activity in a variety of hematologic malignancies, most notably chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), leading to US FDA approval for relapsed CLL and MCL. Ongoing studies are evaluating ibrutinib in other types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Waldenström’s macrogobulinemia, in larger Phase III studies in CLL and MCL, and in combination studies with monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy. Future studies will combine ibrutinib with other promising novel agents currently in development in hematologic malignancies.

Keywords: B-cell receptor, BTK, CLL, ibrutinib, kinase, lymphocytosis, MCL, NHL

Upregulation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) pathway is a hallmark of the pathophysiology underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and certain subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). A key protein in the BCR pathway is Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK). Loss-of-function mutations in BTK result in the human disease X-linked agammaglobulinemia (Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia), which leads to profound γ globulin deficiency and increased risk of infection [1]. Ibrutinib (formerly PCI-32765) is a potent covalent inhibitor of BTK, and treatment of primary CLL cells with ibrutinib results in abrogation of survival signaling downstream of the BCR, a decrease in prosurvival cytokines and modest induction of CLL cell apoptosis [2]. This promising preclinical activity led to early-phase clinical trials of ibrutinib monotherapy in patients with relapsed lymphoid malignancies and subsequent Phase Ib/II studies in relapsed CLL [3] and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [4]. The excellent safety profile and profound efficacy of ibrutinib in these studies and subsequent studies will likely lead to incorporation of the drug into the armamentarium of standard therapies for several lymphoid malignancies in the near future.

Overview of the market

The backbone of standard therapy for patients with CLL has traditionally been chemotherapy. In recent years, chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens, which include monoclonal anti-CD20 antibodies, were developed. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) has become the standard of care for younger, fit patients with CLL owing to its high response rate, long progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) benefit over fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone [5]. Recently, bendamustine/rituximab (BR) has also demonstrated high response rates, albeit with less durable remissions, but also with less hematologic and infectious toxicity than FCR, making it a preferable CIT option for older, less fit patients [6,7]. BR has also become a standard option for patients with MCL [8]. Though often effective at achieving remission, none of these CIT regimens are curative, and all of them carry substantial toxicities, providing strong motivation for the development of more effective and better tolerated agents.

A number of promising new agents are now under development for CLL, MCL and other forms of NHL. Novel oral agents include those targeting the BCR pathway, such as ibrutinib, PI3K inhibitors, and SYK inhibitors, and drugs targeting the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. New antibody-based therapies are also being developed, some of which, such as the recently US FDA-approved obinutuzumab [9], aim to improve the efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies, while others target different antigens. Novel immunologic therapies in development include chimeric antigen receptor T cells [10]. Within this crowded market in CLL/NHL, ibrutinib has emerged as the first novel small molecule to receive FDA approval.

Ibrutinib (PCI-32765)

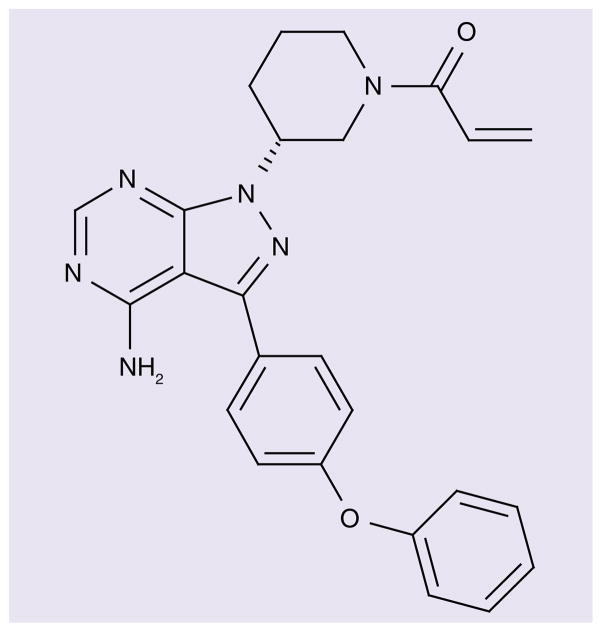

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica™) is a first-in-class BTK inhibitor, manufactured by Pharmacyclics, Inc. (CA, USA) and codeveloped in partnership with Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Beerse, Belgium)/Johnson & Johnson (NJ, USA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of ibrutinib (formerly PCI-32765).

Chemistry

Ibrutinib is a small molecule with the ability to form a covalent bond with Cys-481 in the ATP binding domain of BTK. The chemical name for ibrutinib is 1-{(3R)-3-[4-amino-3-(4-phenoxyphenl)-1-H-pyrazolo [3,4-d]pyrimidin-1-yl]piperidin-1-yl}prop-2-en-1-one, the molecular formula is C25H24N6O2, and the molecular weight is 440.5 g/mol. The IC50 of ibrutinib for BTK is 0.5 nM, although the drug also has activity against at least nine other kinases with a cognate cysteine, including ITK, TEC, BLK and JAK3, as well as EGF receptor and HER2 [11]. This broad activity may have therapeutic implications; for example, ibrutinib was recently found to bind covalently to ITK in T lymphocytes, thereby leading to a Th1-selective pressure [12].

Pharmacokinetics & metabolism

Ibrutinib is rapidly absorbed and eliminated after oral administration, with a time to peak concentration of 1–2 h and an initial mean half-life following oral dosing in humans of only 2–3 h [13]. The fact that the drug covalently binds to BTK for at least 24 h provides the opportunity for daily dosing, while minimizing the duration of off target effects. In Phase I studies, the maximum tolerated dose for ibrutinib was not reached, and based on BTK occupancy, doses of 560 mg daily and 420 mg daily were recommended for MCL and CLL, respectively [13]. The drug is metabolized primarily by the liver, and significant increases in exposure of ibrutinib are expected in patients with hepatic impairment. It is recommended that concurrent use of ibrutinib with strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers be avoided owing to the risk of significantly altering drug levels.

Pharmacodynamics & preclinical studies

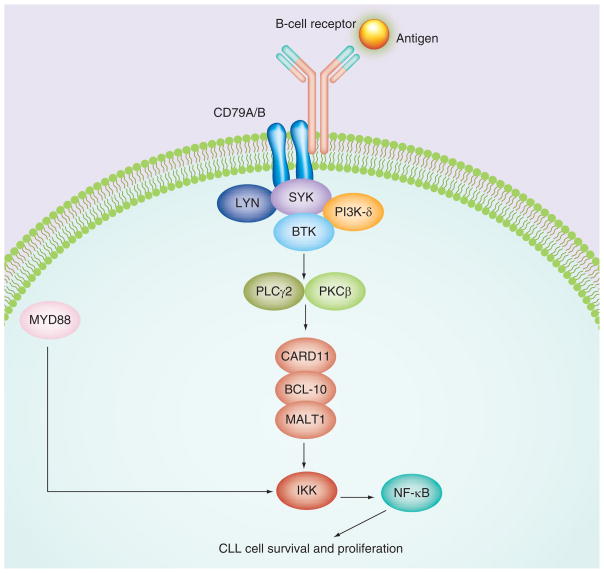

Ibrutinib binds with high affinity to Cys-481 in the active site of BTK, resulting in an IC50 of 0.5 nM [11]. The drug effectively blocks signaling through BTK inhibition, which is a key kinase in the BCR pathway, as illustrated in Figure 2. In a B-cell line in which BCR signaling can be activated with anti-IgG stimulation, ibrutinib has an IC50in the 11 nM range, and the drug inhibits phosphorylation of downstream substrates, such as PLC-γ, in a dose-dependent fashion. In a stromal coculture model, ibrutinib induced CLL cell apoptosis even in the presence of stroma and other prosurvival factors, such as CD40L and B-cell activating factor [2]. In addition to inhibiting CLL survival and proliferation, the drug also impairs CLL cell migration owing to homing chemokines, such as CXCL12 and CXCL13, and downregulates secretion of the BCR-dependent chemokines CCL3 and CCL4, leading to CLL regression in the TCL1 xenograft mouse model [14]. Testing of ibrutinib in canine lymphomas resulted in objective clinical responses in three out of eight dogs with rapidly progressive disease [11].

Figure 2. B-cell receptor signaling pathway.

Ibrutinib targets BTK, a kinase that is critical for signal transduction through the B-cell receptor pathway.

BTK: Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Clinical efficacy

Given the remarkable preclinical efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in lymphoma models, the drug quickly moved into clinical trials in patients with cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ibrutinib (PCI-32765) preclinical, Phase I, II and III trials.

| Study (year) | Disease | Study details | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | ||||

| Honigberg et al. (2010) | CLL | Patient-derived neoplastic cells, mouse and dog models | Ibrutinib blocks BCR signaling in human B cells and induced clinical response in dogs with B-cell NHL | [11] |

| Herman et al. (2011) | CLL | Patient-derived neoplastic cells, stromal coculture model | Ibrutinib abrogates downstream BCR signaling and induces modest apoptosis. It also blocks stromal prosurvival signals | [2] |

| Ponader et al. (2012) | CLL | Patient-derived neoplastic cells, stromal coculture model and TCL-1 mouse model | Ibrutinib inhibits CLL cell survival, DNA synthesis and migration. It also downregulates secretion of BCR-dependent chemokines and causes CLL regression in mouse models | [14] |

| Clinical | ||||

| Advani et al. (2013) | CLL | Phase I included 16 patients with R/R CLL | Responses seen in 11 out of 16 patients with CLL, including two CRs | [13] |

| Byrd et al. (2013) | CLL | Phase Ib/II included 85 patients with R/R CLL | 71% ORR (2% CR) by IW-CLL plus 18% PR with lymphocytosis, 26-month PFS 75% | [3] |

| O’Brien et al. (2013) | CLL | Phase II included 29 treatment-naive elderly patients | 71% ORR (13% CR and 3% nPR) by IW-CLL plus 13% PR with lymphocytosis | [15] |

| Advani et al. (2013) | MCL | Phase I included nine patients with R/R MCL | Responses seen in seven out of nine patients with MCL, including three CRs | [13] |

| Wang et al. (2013) | MCL | Phase II R/R included 111 patients with R/R MCL | 68% ORR, 21% CR and estimated median PFS of 13.9 months | [4] |

| Advani et al. (2013) | DLBCL | Phase I included seven patients with R/R DLBCL | Responses seen in two out of seven patients with R/R DLBCL, both PRs | [13] |

| Wilson et al. (2012) | DLBCL | Phase II included 70 patients with R/R DLBCL | 23% ORR (9% CR), ABC subtype: 41% ORR, GCB subtype: 5% ORR | [16] |

| Advani et al. (2013) | WM | Phase I included four patients with R/R WM | Responses seen in three out of four patients with WM, all PRs | [13] |

| Treon et al. (2013) | WM | Phase II included 63 patients with R/R WM | 81% ORR (77% for CXCR4 wt and 30% for CXCR4 mut) | [17] |

| Fowler et al. (2012) | FL | Phase I included 16 patients with R/R FL | Responses seen in six out of 11 evaluable patients with FL (ORR: 54.5%), including three CRs. Median PFS of 19.6 months in nine patients at doses of 5 mg/kg or higher | [18] |

ABC: Activated B-cell; BCR: B-cell receptor; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR: Complete response; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL: Follicular lymphoma; GCB: Germinal center B cell; IW-CLL: International Working Group for CLL; MCL: Mantle cell lymphoma; mut: Mutant; nPR: Nodular partial response; NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; PFS: Progression-free survival; PR: Partial response; ORR: Overall response rate; R/R: relapsed/refractory; WM: Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia; wt: Wild-type.

-

Potential clinical uses of ibrutinib in cancer

Ibrutinib was first FDA-approved for relapsed/ refractory MCL and CLL; however, it is likely to gain approval in multiple other indications moving forward. Large studies are are ongoing of ibrutinib in front-line MCL and CLL treatment, and data are accumulating for several other types of NHL. Other potential uses for the drug outside of NHL are also being explored:

MCL: accelerated FDA approval in November 2013 [4]

CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL): accelerated FDA approval in February 2014 [15,19]

-

Other types of NHL [13]:

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM)

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, activated B-cell (DLBCL-ABC) subtype

Follicular lymphoma

Marginal zone lymphoma

Multiple myeloma [20]

Acute myeloid leukemia [21]

Phase I trial with single-agent ibrutinib in lymphoid malignancies

The first Phase I study of ibrutinib enrolled 56 patients with both CLL and other B-cell NHLs [13]. Two different dosing regimens were explored, including punctuated dosing with 4 weeks on, 1 week off, and continuous dosing. Most adverse effects were grade 1 and 2 in severity and self-limited, with no cumulative toxicities with prolonged dosing. In the 50 evaluable patients, the overall response rate (ORR) was 60%, including a complete response (CR) rate of 16%. The median PFS was 13.6 months. The most promising efficacy signals in this study were in CLL/SLL (11 out of 16 patients responded [two CRs]), MCL (seven out of nine patients responded [three CRs]), and WM (three out of four patients responded, no CRs observed).

Lymphocyte redistribution

The majority of CLL subjects on this study were noted to have an initial rise in their lymphocyte count in the setting of lymph node shrinkage. This ‘lymphocyte redistribution’ (LR) phenomenon had previously been observed with other BCR antagonists, and is thought to be the result of release of CLL cells from stromal niches in the lymph nodes and/or bone marrow into the blood where the cells subsequently die. The increase of lymphocyte count is typically very rapid, peaks at a median of 4 weeks, and then slowly decreases, although some patients have persistent lymphocytosis for well over 1 year [3]. The presence of LR has not clearly been linked to clinical response, although it has been noted that patients with unmutated IGHV typically have faster resolution of LR, for reasons that are not yet entirely clear. Although there was initial concern that increasing lymphocyte count may be indicative of progressive disease, investigators noted that other disease parameters, such as lymph node size and cytopenias, were simultaneously improving and that eventually the LR resolved in most patients. This posed a challenge to the traditional International Working Group for CLL (IW-CLL) response criteria, which do not allow for achievement of a partial response (PR) or CR in the setting of persistent lymphocytosis [22]. These observations led to a recommendation that in patients on BCR antagonists including ibrutinib, a patient with LR who is otherwise responding well to therapy may be labeled as having achieved a nodal response with lymphocytosis [23].

Ibrutinib in CLL/SLL

Phase Ib/IIa trial with single-agent ibrutinib in CLL/SLL

The promising results from the Phase I study in lymphoid malignancies prompted a CLL/ SLL-specific Phase Ib/IIa trial that enrolled both patients with relapsed refractory disease, as well as a small cohort of older patients with previously untreated disease.

Relapsed/refractory

A total of 85 patients with relapsed refractory CLL/SLL were enrolled and received either 420 mg (n = 51) or 840 mg (n = 34) daily on a continuous schedule until time of progression or unacceptable toxicity [3]. The majority of patients on this study were considered to have high-risk disease based on CLL/SLL prognostic markers and/or response to prior therapies. The ORR, based on standard IW-CLL criteria, was 71% (including two CRs). An additional 15 patients had a nodal response with lymphocytosis, meaning that approximately 88% of patients achieved clinical benefit from the drug. The response rate did not vary according to most of the traditional high-risk prognostic features, such as del(17p), where the ORR was 68%. Interestingly, patients with unmutated IGHV actually had a higher response rate of 77% compared with mutated IGHV patients (p = 0.005), probably owing to the fact that the lymphocytosis resolved more quickly in the unmutated group. These promising responses have proven to be durable for the majority of patients, with a 26-month estimated rate of PFS of 75%.

One area of concern from this study is that although patients with del(17p) (n = 28) had equivalent response rates to other patients, their 26-month estimated rate of PFS is shorter (57 vs 75%). Some of the samples from time of progression were sequenced to look for mutations that may confer resistance. Interestingly, several patients were found to have C481S mutations that inhibited covalent binding of ibrutinib to BTK, and one patient had a R665W substitution in PLC-γ2, a substrate of BTK, consistent with constitutive PLC-γ2 activation [24]. Whole-exome sequencing of samples from patients on ibrutinib with progressive disease has also revealed the emergence of leukemic populations with high-risk genetic alterations with putative driver characteristics, such as del(8p) and SF3B1 mutation, which arose from a background of pre-existing 17p or 11q deletion, suggesting that resistance to the drug cannot be solely attributed to mutations in BTK or other genes in the BCR pathway [25]. Another area of concern from this study is that seven of the 11 patients who developed progressive disease did so by biologic transformation (Richter’s syndrome). This phenomenon has been observed in CLL patients on trials of other novel agents, and it remains to be seen whether these new drugs are inducing a selective pressure on CLL cells that is predisposing to Richter’s syndrome, or whether we are observing the natural history of CLL patients with highly refractory disease who are living longer than they otherwise would without these new drugs.

Previously untreated

In total, 31 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL were also enrolled on this study, and the results were recently reported [15]. To qualify, patients had to be aged at least 65 years and have symptomatic CLL or SLL requiring therapy by IW-CLL criteria. The median age was 71 years (range: 65–84 years), and the incidence of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities was low (only two patients with del[17p] and one patient with del[11q]). Approximately half of the patients had unmutated IGHV. A total of 22 out of 31 patients (71%) achieved an objective response, including four patients (13%) with a CR and one patient (3%) with a nodular PR. An additional four (13%) patients achieved a partial response with lymphocytosis. The median follow-up on this study remains short for a front-line study at 22.1 months, and at this early time point, the median PFS has not yet been reached, with only one patient having progressed during follow-up. One theoretical question is whether prolonged exposure to ibrutinib may lead to a decrease in serum immunoglobulin levels owing to effects of the drug on normal B cells, thereby leading to increased risk of infection. In this study, there were no changes in IgG levels during the first year of treatment, providing some initial evidence that this concern may be unwarranted. Since ibrutinib was highly effective and well tolerated in this elderly CLL population, the question is raised as to whether ibrutinib will replace chemotherapy as the preferred initial therapy for this group. Although these initial data look promising, more data from ongoing randomized studies in comparison to standard chemoimmunotherapy will be needed before definitive recommendations can be made.

Combination studies of ibrutinib for CLL

Although the efficacy data for ibrutinib as a single agent in CLL are strong, there have been few complete remissions, and at least based on the currently available data, it seems unlikely that the drug has curative potential as a single agent. Therefore, much attention has recently been focused on finding optimal combination partners for ibrutinib to improve the depth and duration of response and perhaps even to devise a curative combination treatment strategy.

Ibrutinib plus antibody

Given that monoclonal anti-CD20 antibodies are typically well tolerated and active in combination with other therapies in CLL, it is not surprising that the first combination studies with ibrutinib in CLL were with these agents. A Phase II study of ibrutinib plus rituximab enrolled 40 patients who were treated with continuous ibrutinib at 420 mg daily along with weekly rituximab (375 mg/m2) for 4 weeks, then monthly until cycle six, at which point responders continued on ibrutinib alone until progression [26]. The median age was 65 years, with a median of two prior therapies. Half of the patients had either del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and 80% of patients had unmutated IGHV. The ORR was 95%, including 8% CR, with one of the CR patients achieving minimal residual disease negativity by flow cytometry. The 20 patients with del(17p) or TP53 mutation had a response rate of 90%, with two patients achieving CR. Quality of life was also measured in this study and was found to improve significantly over the course of the study. As expected, LR resolved more rapidly and completely compared with patients in prior studies of ibrutinib monotherapy. A randomized study of ibrutinib plus or minus rituximab recently opened at MD Anderson Cancer Center (TX, USA) and will help determine whether there is a PFS and ultimately an OS benefit to adding rituximab to ibrutinib in this patient population. A randomized, Phase III trial being run by the Alliance cooperative group will seek to answer a similar question in a previously-untreated elderly population, and will also include a bendamustine/rituximab arm to compare ibrutinib with or without rituximab to a standard chemotherapy regimen for this population.

Promising results have also been reported with the combination of ibrutinib with the fully-humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab. A Phase Ib/II study in relapsed refractory CLL is evaluating three different dosing schedules of the ibrutinib ofatumumab combination, and data have been presented on the schedule that starts ibrutinib 4 weeks prior to starting ofatumumab, which is then given for a standard 6-month course, with ibrutinib continued as maintenance at the conclusion of the combination portion of the study [27]. In total, 27 patients have been reported thus far, with a median age of 66 years and median of three prior therapies. This was a high-risk group, with 37% having del(17p), 33% having del(11q) and 91% having unmutated IGHV. All 27 patients achieved a response by IW-CLL criteria, including one patient with a CR. At a median 9.8 months of follow-up, 89% of patients remained on study, with only one patient coming off study for progressive disease. Interestingly, this study included three patients with Richter’s syndrome, and two out of the three achieved a response, with one Richter’s patient remaining on study in ongoing response at 10.1 months.

The strong efficacy data along with the favorable toxicity profile of these early studies of ibrutinib with monoclonal antibodies are promising, and support the development of larger randomized studies to help determine how much benefit is gained through the addition of the antibody compared with the already impressive activity of ibrutinib alone. Such studies are particularly essential in light of recent preclinical data suggesting that inhibition of ITK by ibrutinib may antagonize the ability of rituximab to cause antibody-dependent natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity [28], providing a rationale for exploring alternative ibrutinib dosing schedules (sequential vs concurrent) in future trials to maximize the activity of the combination.

Ibrutinib plus chemoimmunotherapy

Though older patients and those with comorbidities often experience significant toxicity with CIT, younger, fit patients may derive benefit from the deep responses achieved by these regimens, in particular FCR. For example, approximately 20% of patients achieved an minimal residual disease-negative CR in the bone marrow with front-line FCR, and many of these patients went on to have durable remissions lasting 10 years or more [29]. Therefore, a logical avenue to explore is the combination of ibrutinib with CIT to try to enhance these responses further.

The final results of a Phase Ib study of ibrutinib in combination with BR for relapsed/refractory CLL were recently reported [30]. In total, 30 patients with CLL/SLL with a median age of 62 years and a median of two prior therapies were treated with ibrutinib with continuous dosing at 420 mg daily along with up to six cycles of BR, followed by ibrutinib maintenance. The combination was well tolerated, and the ORR was 93%, including five CRs, three nodular PRs and 20 PRs, with one additional patient achieving PR with lymphocytosis. The estimated 15-month PFS was 78%, and responses were independent of high-risk features. These results provided a strong rationale for the development of a Phase III study of BR plus or minus ibrutinib, which is now ongoing. Three younger patients with a median age of 56 years who were treated with ibrutinib in combination with FCR at standard dosing were also included in this study. All three patients completed six cycles of therapy and two of these patients achieved CR, while a nodular PR was observed for the remaining patient. These results warrant further exploration of the ibrutinib plus FCR combination in future studies.

Ibrutinib in MCL

To explore the promising efficacy signal observed with ibrutinib in MCL in the Phase I study, a Phase II study with ibrutinib at 560 mg continuous daily was conducted, with 111 patients enrolled [4]. The median age was 68 years, 86% of patients had intermediate to high MCL International Prognostic Index scores, and patients had a median of three prior therapies. A response rate of 68% was observed, including 21% CR rate. Modest elevations in circulating lymphocyte count were observed in 34% of patients, although these were typically much shorter lived and of smaller magnitude than the LR observed in CLL. Many of the MCL responses were durable, with an estimated median PFS of 13.9 months, and an OS of 58% at 18 months. These efficacy data compare quite favorably to salvage chemotherapy regimens, which have high rates of toxicity with limited efficacy in this setting. Due to the major unmet medical need of this relapsed/refractory MCL population, ibrutinib received accelerated FDA approval for this indication in November 2013, based on this Phase II study. An ongoing randomized Phase III trial is examining bendamustine/rituximab with or without ibrutinib as first-line therapy in newly diagnosed patients with MCL [31].

Ibrutinib in WM

Based on the strong efficacy signal observed in WM patients in the Phase I study, a Phase II study of ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory WM was conducted, with 63 patients enrolled [17]. The median age was 63 years, with a median of two prior therapies. The best ORR using consensus criteria adapted from the Third International Workshop on WM was 81% (no CRs), with rapid reductions in serum IgM and improved hematocrit observed in most patients. Interestingly, patients on this study had Sanger sequencing performed on sorted bone marrow lymphoplasmacytic cells to determine the CXCR4 and MYD88 mutation status; patients with wild-type CXCR4 had a significantly higher rate of major response than those with CXCR4 mutations (77 vs 30%, respectively; p = 0.018). By contrast, the response rate in patients with MYD88 L265P mutation was equivalent to patients with wild-type MYD88, although there were only three of the latter group. This trial is illustrative of the type of correlative laboratory work that may one day prospectively guide selection of drugs such as ibrutinib for the particular patients most likely to benefit.

Ibrutinib in DLBCL

This approach of individualized therapy with ibrutinib may also be applicable in DLBCL, where cell of origin appears to be associated with response to the drug. Interim results from a multicenter Phase II study in 70 DLBCL patients treated with ibrutinib 560 mg daily found an ORR of 22% with a CR rate of 5% [16]. Interestingly, patients with the ABC subtype had a significantly higher response rate (41%) compared with patients with the germinal center B cell subtype (5%). Responses occurred both in patients with mutated and wild-type CD79B, suggesting that ibrutinib sensitivity does not require a BCR pathway mutation. By contrast, none of the patients with sole mutation of proteins downstream of BTK, such as MYD88 (n = 5) or CARD11 (n = 4) responded. Interestingly, patients with both CD79B and MYD88 mutations did respond in four out of five cases, suggesting that perhaps CD79B-driven BCR pathway activation was dominant in these patients. The median PFS of ABC responders on this study was only 2.5 months, suggesting that although ibrutinib has activity as a single agent in DLBCL-ABC, it may be necessary to combine it with other agents to achieve more durable responses.

This combination approach is being explored in an ongoing Phase Ib study of ibrutinib in combination with standard rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy in treatment-naive patients with CD20-positive NHL, including DLBCL [32]. A total of 33 patients have been enrolled, and the ORR for evaluable patients in the DLBCL cohort (n = 22) is 100%, including 64% CR and 36% PR. Cell of origin data from this study are limited, as only a small number of patients have been subtyped, and this has been performed by immunohistochemical analysis as opposed to the more accurate gene-expression pro-filing technique utilized in the ibrutinib mono-therapy study. The efficacy data of ibrutinib in combination with standard R-CHOP appear promising, but data from an ongoing randomized, placebo-controlled study of R-CHOP plus or minus ibrutinib in patients with nongerminal center B-cell DLBCL will be critical to determine whether ibrutinib adds significantly to the efficacy of chemotherapy in this setting.

Safety & tolerability

Overall, ibrutinib has demonstrated that it is well tolerated (Table 2). In preclinical models, ibrutinib achieved target inhibition of BTK at dose levels that produced no overt toxicity. In the initial Phase I study in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, most of the adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 and 2 in severity and were self-limited. These common grade 1/2 AEs included pain (62.5%), respiratory issues (50%), diarrhea (42.9%), nausea/vomiting (41.1%), muscle spasms/myalgia (37.5%), fatigue (37.5%), cough (32.1%) and decreased appetite/dyspepsia (30.4%). Grade 3 or 4 toxicities were uncommon and independent of dose, and included neutropenia (12.5%), thrombocytopenia (7.2%) and anemia (7.1%). These cytopenias were generally thought to be related to the underlying malignancy, and the majority of patients had improvement in their blood counts with ibrutinib treatment. Two dose-limiting toxicities were observed, including a dose interruption of greater than 7 days for grade 2 neutropenia and a grade 3 allergic reaction. Dose-limiting events were not observed, even with prolonged dosing. The maximum tolerated dose was defined as a dose three levels above the dose level with full BTK occupancy, as measured by a fluorescent affinity probe.

Table 2.

Safety outcomes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma clinical trials.

| Study (year) | Disease | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advani et al. (2013) | Lymphoid malignancies | Grade 1/2 AEs: pain, respiratory issues, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, muscle spasms/myalgia, fatigue, cough and decreased appetite/dyspepsia Grade 3/4 AEs: cytopenias DLTs: grade 3 allergic reaction and dose interruption for >7 days due to grade 2 neutropenia |

[13] |

| Byrd et al. (2013) | CLL | Grade 1/2 AEs: diarrhea, fatigue and URTI Grade 3/4 AEs: pneumonia and dehydration |

[3] |

| O’Brien et al. (2013) | CLL | Grade 1/2 AEs: diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, hypertension and contusion Grade 3/4 AEs: infection, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia |

[15] |

| Wang et al. (2013) | MCL | Grade 1/2 AEs: diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, peripheral edema, dyspnea, constipation, URTI, vomiting and decreased appetite Grade 3/4 AEs: bleeding (including subdural hematoma), neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia and sepsis |

[4] |

AE: Adverse event; CLL: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLT: Dose-limiting toxicity; MCL: Mantle cell lymphoma; URTI: Upper respiratory tract infection.

In the Phase Ib and Phase II studies, a similar toxicity profile has been observed, and long-term therapy with ibrutinib has generally been well tolerated, again with most of the AEs being grade 1 or 2. Common AEs include diarrhea, fatigue and upper respiratory tract infections; most of these patients were able to continue on study drug with eventual resolution of the AEs. One common AE to highlight is bruising, which is typically grade 1–2, but occurs in nearly half of patients and is probably due to the inhibition of BTK and possibly other kinases in platelets [33]. Serious AEs have been rare, and have included pneumonia and bleeding events (including subdural hematoma, gastrointestinal bleeding and hematuria) in a small number of patients; for example, five of the 115 patients on the Phase II study in MCL had grade 3 bleeding events, with no patients having grade 4 or 5 bleeding events. Several of these bleeding events were in patients on warfarin, prompting subsequent patients on warfarin to be excluded from ibrutinib clinical trials. Based on this experience, ibrutinib’s label advises caution when utilizing the drug in patients on therapeutic anticoagulation of any kind. In addition, it is recommended that patients undergoing elective surgery hold ibrutinib for 3–7 days before and after the procedure to reduce the risk of bleeding complications.

Regulatory affairs

The uniformly high levels of durable response seen with ibrutinib in clinical trials led the FDA to grant breakthrough therapy designations for ibrutinib in MCL, 17p(del) CLL and WM. Ibrutinib received accelerated approval by the FDA in the USA on 13 November 2013 for patients with MCL who have received at least one prior therapy and for CLL on 12 February 2014, again for patients who have received at least one prior therapy. A new marketing authorization application has also been submitted to the EMA for both relapsed CLL and MCL to seek approval for ibrutinib in the EU. As with any drug that receives accelerated approval based on data from a relatively small sample size of patients on the initial clinical trials, close attention will be paid to the safety and efficacy data that emerge from the ongoing larger Phase III studies of ibrutinib, and pharmacovigilance will be critical to detect safety issues that may emerge in patients receiving ibrutinib by prescription.

Conclusion

Ibrutinib has demonstrated profound single-agent activity in challenging patient populations, such as relapsed MCL and relapsed high-risk CLL. Preclinical data support exploration of ibrutinib’s activity in other hematologic malignancies, such as multiple myeloma [20], as well as acute myeloid leukemia [21]. The most common reported AEs have included diarrhea, bruising and upper respiratory infections, and grade 3/4 toxicities have been uncommon, with the most common ones being cytopenias that are unlikely to be related to ibrutinib. Dose reduction or discontinuation owing to adverse effects has been rare, even with long-term use. Ibrutinib has also been safely combined with both monoclonal antibodies and chemotherapy, and exciting combination studies with other novel agents in development are on the near horizon.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

Mechanism of action

Imbruvica is an oral inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK).

The drug inhibits the B-cell receptor pathway, leading to several effects on malignant B lymphocytes, including direct induction of apoptosis, inhibition of proliferation and effects on lymphocyte trafficking, which lead to egress of lymphocytes from the protective stromal microenvironment, resulting in subsequent apoptosis in the peripheral blood.

Pharmacokinetic properties

The drug is rapidly absorbed and eliminated after oral administration, time to peak concentration of 1–2 h.

The drug has an initial mean half-life following oral dosing of 2–3 h.

Daily dosing is possible because the drug covalently binds to BTK.

The maximum tolerated dose was not reached, and recommended Phase II dose was chosen to be three dose levels above full BTK occupancy.

The drug is metabolized primarily hepatically.

Clinical efficacy

There have been durable responses to ibrutinib observed in the majority of patients with relapsed/refractory and previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia, with equivalent response rates in patients with high-risk markers such as del(17p).

There are high response rates in relapsed mantle cell lymphoma with significantly longer progression-free survival than other drugs in this setting.

There are promising preliminary efficacy results in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, especially in patients with wild-type CXCR4.

There is a signal of efficacy in the activated B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, although durability of single-agent response is limited.

There has been activity observed in other types of indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, such as follicular lymphoma.

Safety & tolerability

Long-term therapy is associated with modest toxicity, with most adverse events being grade 1 or 2.

Common adverse events include diarrhea, fatigue, bruising, and upper respiratory tract infections.

Serious adverse events have been rare, and have included bleeding events and pneumonia.

Drug interactions

Caution should be used when giving the drug to patients on therapeutic anticoagulation.

Concurrent use with strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers should be avoided.

Dosage & administration

The approved dose for mantle cell lymphoma is 560 mg daily given orally.

The approved dose for chronic lymphocytic leukemia is 420 mg daily given orally.

Combination studies are ongoing to help determine the optimal dosing in various combinations.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact: reprints@futuremedicine.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

MS Davids has served as a consultant for Infinity, and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb. JR Brown has served as a consultant for Avila, Novartis, Genentech, Celgene, Emergent, Sanofi-Aventis, Pharmacyclics and Onyx, and has received research funding from Genzyme (now Sanofi-Aventis). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest;

••of considerable interest

- 1.de Weers M, Mensink RG, Kraakman ME, Schuurman RK, Hendriks RW. Mutation analysis of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase gene in X-linked agammaglobulinemia: identification of a mutation which affects the same codon as is altered in immunodeficient xid mice. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(1):161–166. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman SE, Gordon AL, Hertlein E, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood. 2011;117(23):6287–6296. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):32–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637. The most definitive published results of ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):507–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306220. The most definitive published results of ibrutinib in relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter Phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(26):3209–3216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Busch RB, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (F), cyclophosphamide (C), and rituximab (R) (FCR) versus bendamustine and rituximab (BR) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results of a planned interim analysis of the CLL10 trial, an international, randomized study of The German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). Presented at: The 55th ASH® Annual Meeting and Exposition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, Phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Head-to-head comparison of obinutuzumab (GA101) plus chlorambucil (Clb) versus rituximab plus clb in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and co-existing medical conditions (comorbidities): final stage 2 results of the CLL11 trial. Presented at: The 55th ASH® Annual Meeting and Exposition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, et al. The bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(29):13075–13080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107. Important preclinical work that provided the rationale for exploring ibrutinib in the clinic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubovsky JA, Beckwith KA, Natarajan G, et al. Ibrutinib is an irreversible molecular inhibitor of ITK driving a Th1-selective pressure in T lymphocytes. Blood. 2013;122(15):2539–2549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13•.Advani RH, Buggy JJ, Sharman JP, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (PCI-32765) has significant activity in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):88–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7906. Final results of the Phase I study of ibrutinib in relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponader S, Chen SS, Buggy JJ, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 thwarts chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell survival and tissue homing in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2012;119(5):1182–1189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: an open-label, multicentre, Phase 1b/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;15(1):48–58. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70513-8. Most definitive published results of ibrutinib in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson WH, Gerecitano JF, Goy A, et al. The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, ibrutinib (PCI-32765), has preferential activity in the ABC subtype of relapsed/refractory de novo diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma (DLBCL): interim results of a multicenter, open-label, Phase 2 study. Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 686. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treon SP, Tripsas CK, Yang G, et al. A prospective multicenter study of the bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 251. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler NH, Advani RH, Sharman JP, et al. The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib (PCI-32765) is active and tolerated in relapsed follicular lymphoma. Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; GA, USA. 8–11 2012; p. Abstract 156. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrd JC, O’Brien S, James DF. Ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(13):1278–1279. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1309710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rushworth SA, Bowles KM, Barrera LN, Murray MY, Zaitseva L, MacEwan DJ. BTK inhibitor ibrutinib is cytotoxic to myeloma and potently enhances bortezomib and lenalidomide activities through NF-kappaB. Cell Signal. 2013;25(1):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rushworth SA, Murray MY, Zaitseva L, Bowles KM, MacEwan DJ. Identification of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase as a therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;123(8):1229–1238. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-511154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111(12):5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheson BD, Byrd JC, Rai KR, et al. Novel targeted agents and the need to refine clinical end points in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2820–2822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang B, Furman RR, Zapatka M, et al. Use of tumor genomic profiling to reveal mechanisms of resistance to the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Presented at: ASCO Annual Meeting; IL, USA. 31 May–4 June 2013; p. Abstract 7014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger JA, Landau D, Hoellenriegel J, et al. Clonal evolution in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) developing resistance to BTK inhibition. Presented at: The 55th ASH® Annual Meeting and Exposition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 866. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burger JA, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, et al. Ibrutinib in combination with rituximab (iR) is well tolerated and induces a high rate of durable remissions in patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): new, updated results of a Phase II trial in 40 patients. Presented at: The 55th ASH® Annual Meeting and Exposition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 7014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaglowski SM, Jones JA, Flynn JM, et al. A Phase Ib/II study evaluating activity and tolerability of BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 and ofatumumab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and related diseases. Presented at: 2012 ASCO Annual Meeting; IL, USA. 1–5 June 2012; p. Abstract 6508. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohrt H, Sagiv-Barfi I, Rafiq S, et al. Ibrutinib (PCI-32765) antagonizes rituximab-dependent NK-cell mediated cytotoxicity. Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 373. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bottcher S, Ritgen M, Fischer K, et al. Minimal residual disease quantification is an independent predictor of progression-free and overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multivariate analysis from the randomized GCLLSG CLL8 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):980–988. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown JR, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib in combination with bendamustine and rituximab is active and tolerable in patients with relapsed/refractory CLL/SLL. Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 525. [Google Scholar]

- 31.A Study of the Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib Given in Combination With Bendamustine and Rituximab in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Mantle Cell Lymphoma. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01776840

- 32.Younes A, Flinn I, Berdeja J, et al. Combining ibrutinib with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP): updated results from a Phase 1b study in treatment-naive patients with CD20-positive B-Cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Presented at: The 55 ASH® Annual Meeting and Exopsition; LA, USA. 7–10 December 2013; p. Abstract 852. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Fitzgerald ME, Berndt MC, Jackson CW, Gartner TK. Bruton tyrosine kinase is essential for botrocetin/VWF-induced signaling and GPIb-dependent thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2006;108(8):2596–2603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]