Abstract

The molecular mechanisms that maintain quiescence of the myometrium throughout most of pregnancy and promote its transformation to a highly coordinated contractile unit culminating in labor are complex and intertwined. During pregnancy, progesterone (P4) produced by the placenta and/or ovary serves a dominant role in maintaining myometrial quiescence by blocking proinflammatory response pathways and expression of so-called “contractile” genes. In the majority of placental mammals, increased uterine contractility near term is heralded by an increase in circulating estradiol-17β (E2) and/or increased estrogen receptor α (ERα) activity and a sharp decline in circulating P4 levels. However, in women, circulating levels of P4 and progesterone receptors (PR) in myometrium remain elevated throughout pregnancy and into labor. This has led to the concept that increased uterine contractility leading to term and preterm labor is mediated, in part, by a decline in PR function. The biochemical mechanisms for this decrease in PR function are also multifaceted and interwoven. In this paper, we focus on the molecular mechanisms that mediate myometrial quiescence and contractility and their regulation by the two central hormones of pregnancy, P4 and estradiol-17β. The integrative roles of microRNAs also are considered.

Progesterone (P4) and progesterone receptor (PR) levels remain high through pregnancy and into labor, maintaining myometrial quiescence. Various molecular regulators (e.g., microRNAs) may antagonize PR function near term.

Preterm birth, defined as birth at <37 wk gestation, is the leading cause of infant mortality during the first four weeks of life throughout the world (Blencowe et al. 2012). Globally, ∼15 million babies are born prematurely each year and 1.1 million of these succumb to complications of their untimely birth. The highest rates of preterm birth are found in parts of Africa and in North America. In the United States, the incidence of preterm birth has increased steadily over the past several decades and has recently leveled off at ∼11.5% of all live births. Importantly, the incidence of preterm birth in the U.S. is even higher among certain racial and ethnic groups. Whereas the prematurity rate in white infants is ∼11%, ∼18% of black infants are born prematurely. The reasons for this racial disparity in the U.S. population are not understood (Peltier et al. 2012). The high incidence of preterm birth is due, in part, to our incomplete understanding of the signaling pathways that maintain quiescence of the uterine myometrium throughout pregnancy and mediate its conversion into a synchronous contractile unit culminating in parturition. Although spontaneous preterm birth has multiple pathologic associations, the only definitive causal link established thus far is to subclinical intraamniotic infections, which account for ∼25% of preterm births (Romero et al. 2014).

The maintenance of myometrial quiescence throughout most of pregnancy is mediated by increased circulating levels of progesterone (P4), produced by placenta and/or the ovarian corpus luteum, depending on the species. We believe that the predominant actions of P4 to block myometrial contractility are mediated by its binding to two nuclear receptor isoforms, hPR-A (94 kDa) and hPR-B (114 kDa), which arise from a single gene by alternative transcription initiation from different promoters (Kastner et al. 1990) and by alternative translation initiation from different translation initiation (AUG) sites (Conneely et al. 1987). The mechanisms whereby P4/PR maintains uterine quiescence are diverse and involve the possible antagonistic interaction of PR with proinflammatory transcription factors (Hardy et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2012), as well as genomic actions, including increased expression of genes that block activation of proinflammatory transcription factors (Hardy et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2011) and/or by direct suppression of contractile genes (Renthal et al. 2010).

Both term and preterm labor are associated with an increased inflammatory response. This is characterized by elevated concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6) in amniotic fluid (Cox et al. 1997) and infiltration of the myometrium, cervix, and fetal membranes by neutrophils and macrophages (Thomson et al. 1999; Osman et al. 2003; Condon et al. 2004). The invading immune cells secrete proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Romero et al. 2007), resulting in activation of NF-κB and other proinflammatory transcription factors in the myometrium (Condon et al. 2004, 2006). Activated NF-κB, in turn, increases expression of genes promoting myometrial contractility, including the prostaglandin F2α receptor (Olson 2003), the gap junction protein, connexin 43 (CX43/Gja1) (Chow and Lye 1994), the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) (Fuchs et al. 1984), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Soloff et al. 2004; Hardy et al. 2006). In preterm labor, intra-amniotic infection associated with chorioamnionitis may provide the stimulus for increased amniotic fluid interleukins and inflammatory cell migration (Rauk and Chiao 2000). At term, mechanical stretch (Sooranna et al. 2004; Shynlova et al. 2008) caused by the growing fetus, as well as hormonal signals produced by the developing fetus near term (Mitchell et al. 1984; Challis et al. 2000; Shaw and Renfree 2001; Condon et al. 2004), promote production of chemokines leading to macrophage migration and up-regulation of inflammatory response pathways, as well as a decline in progesterone receptor (PR) function. Our findings suggest that SP-A, the major lung surfactant protein, which is up-regulated in fetal lung during the third trimester (Mendelson and Boggaram 1990) and secreted into amniotic fluid in large amounts near term (Snyder et al. 1988; Condon et al. 2004), may provide an important signal for macrophage migration, activation of uterine NF-κB, and other inflammatory transcription factors, leading to the initiation of labor (Condon et al. 2004; Mendelson and Condon 2005; Montalbano et al. 2013).

Here, we review the cellular and molecular mechanisms whereby P4 acting through nuclear PR regulates myometrial quiescence throughout most of pregnancy, and the mechanisms whereby proinflammatory cytokines and E2/ERα antagonize PR function near term. The hormonal regulation and roles of microRNAs (miRNA, miR) and their targets as important regulators of myometrial quiescence and contractility are also considered.

MECHANISMS FOR P4/PR REGULATION OF MYOMETRIAL QUIESCENCE

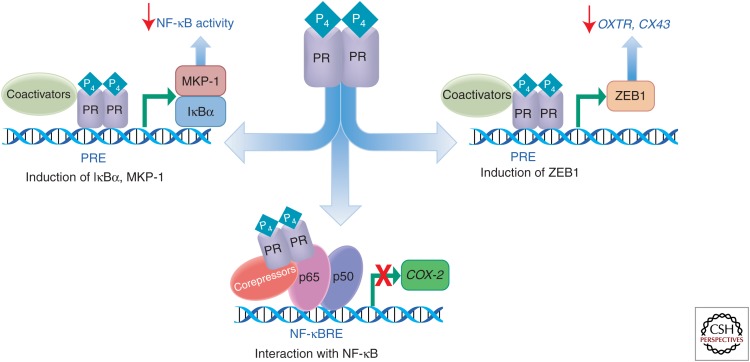

The mechanisms whereby P4/PR maintains the myometrium in a quiescent state throughout most of pregnancy are multifactorial and involve nongenomic and genomic actions. On the one hand, P4/PR can exert a pronounced anti-inflammatory effect, by inhibiting activation/DNA binding of the proinflammatory transcription factors, NF-κB (Hardy et al. 2006) and AP-1 (Dong et al. 2009). Alternatively, P4/PR can block induction of the proinflammatory response by up-regulating expression of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα (Hardy et al. 2006), and the mitogen-activated kinase (MAPK) inhibitor, MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1), also known as dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) (Chen et al. 2011). Moreover, in recent studies, we observed that P4/PR increases expression of the transcriptional inhibitor, ZEB1, which binds to the promoters of the contractile genes CX43 and OXTR to suppress their expression throughout most of pregnancy (Fig. 1) (Renthal et al. 2010, 2013).

Figure 1.

Molecular mechanisms for P4/PR regulation of myometrial quiescence. PR maintains myometrial quiescence, in part, by blocking activation of NF-κB and preventing its transcriptional activation of proinflammatory genes, such as COX-2. P4/PR exerts this action by increasing expression of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκBα, which prevents activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p50 and p65 and by induction of MKP-1/DUSP1, which inhibits p38 MAPK activation and NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation. PR also inhibits activation of CAP genes (e.g., COX-2) by direct interaction/tethering to NF-κB bound to response elements in the promoters of these genes. In addition, PR prevents myometrial contractility by increasing expression of ZEB1, which inhibits expression of CX43 and OXTR.

P4/PR Maintains Myometrial Quiescence by Its Anti-Inflammatory Actions

P4/PR maintains uterine quiescence, in part, by inhibiting activation of inflammatory response pathways and expression of “contractile” genes within the uterus and cervix and by blocking the production of chemokines that promote chemotaxis of immune cells. During the estrous cycle in rodents, migration of macrophages and neutrophils to the uterus is stimulated by E2 and inhibited by P4 (Hunt et al. 1998; Kaushic et al. 1998; Tibbetts et al. 1999). This antagonistic effect of P4 on estrogen-induced macrophage/neutrophil migration fails to occur in mice with a deletion of the PR gene (PRKO mice) and is, therefore, PR-dependent (Tibbetts et al. 1999). Furthermore, PRKO mice manifest a massive uterine inflammatory response to estrogen (Tibbetts et al. 1999) or E2 plus P4 treatment (Lydon et al. 1995).

Expression of the β-chemokine, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL-2), which attracts and activates macrophages, was found to be stimulated by NF-κB and inhibited by P4/PR in choriodecidual and breast cancer cells (Kelly et al. 1997). Notably, MCP-1 was reported to be up-regulated in myometrium of women in labor, as compared with myometrium from term pregnant women not in labor (Esplin et al. 2005) and in pregnant rat myometrium before and during parturition (Shynlova et al. 2008). Furthermore, MCP-1 expression and macrophage infiltration were greatly increased in the pregnant rat uterus after PR blockade by RU486 treatment, which caused preterm parturition. MCP-1 and macrophage infiltration were inhibited by progestin treatment, which delayed parturition (Shynlova et al. 2008).

Using telomerase-immortalized human myometrial cells, P4/PR was found to serve a major anti-inflammatory role via antagonism of both NF-κB activation and COX-2 expression (Havelock et al. 2005; Hardy and Mendelson 2006). A similar phenomenon was observed in studies using amnion epithelial cells, lower uterine segment fibroblasts (Loudon et al. 2003), and human breast cancer cells (Hardy et al. 2008). By use of chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) analysis, we found that P4 treatment of the human myometrial cells blocked IL-1 induction of in vivo binding of NF-κB p65 to both proximal and distal NF-κB response elements in the COX-2 promoter (Hardy et al. 2006). The P4-mediated decrease in p65 binding to the COX-2 promoter might be caused, in part, by a direct physical interaction of PR with p65 (Kalkhoven et al. 1996), which may, in turn, promote the recruitment of corepressors (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the anti-inflammatory effect of P4 within the myometrium also may be mediated by increased expression of IκBα, a crucial inhibitor of NF-κB transactivation (Fig. 1). Glucocorticoids acting through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which is structurally related to PR, are known to induce IκBα expression in a cell type- and promoter-specific manner (Auphan et al. 1995; Scheinman et al. 1995). Similarly, P4 caused a rapid induction of IκBα mRNA and protein expression in the immortalized human myometrial cells, which preceded its effect to inhibit IL-1β-induced COX-2 expression (Hardy et al. 2006). Moreover, co-incubation of IL-1β with P4 prevented the IL-1β-induced decline in IκBα protein levels, suggesting that P4/PR also blocks IκBα degradation via the proteasome pathway (Baldwin 1996). As a consequence of the increased IκBα expression, more NF-κB is likely sequestered in an inactive state in the cytoplasm. P4 inhibition of NF-κB activation by induction of IκBα has also been observed in macrophage cell lines (Miller and Hunt 1998) and in T47D breast cancer cells (Deroo and Archer 2002; Hardy et al. 2008).

In T47D human breast cancer cells, MKP-1/DUSP1 serves as a PR target gene that mediates P4/PR repression of ERK1/2 activation by serum growth factors and the subsequent increase in cell proliferation (Chen et al. 2011). PR acts to increase MKP-1 expression and to inhibit MAPK activation in T47D cells both by classical and nonclassical mechanisms. Findings from ChIP-qPCR and luciferase reporter assays, suggest that PR up-regulates MKP-1 promoter activity in a ligand-dependent manner through binding to two progesterone response elements (PREs) downstream from the MKP-1 transcription start site (TSS). PR also acts in a ligand-independent manner to increase MKP-1 expression by interaction with two putative Sp1 response elements downstream from the TSS (Chen et al. 2011). Because ERK and p38 MAPK can activate NF-κB (Vanden Berghe et al. 1998) and MKP-1 overexpression decreases NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation (Gil-Araujo et al. 2014), P4 has the capacity to inhibit NF-κB activation via induction of MKP-1.

Importantly, it appears that PR also inhibits NF-κB activation and COX-2 induction via ligand-independent mechanisms. In studies using human breast cancer cells in which PR-A and PR-B protein levels were completely suppressed using siRNA-mediated knockdown, COX-2 expression was up-regulated >30-fold (Hardy et al. 2006). This phenomenon was observed in the absence of P4 treatment. Conversely, up-regulation of PR protein expression in breast cancer cells, markedly inhibited IL-1β induction of COX-2 expression in a P4-independent manner (Janowski et al. 2007).

P4/PR Maintains Myometrial Quiescence throughout Pregnancy by Increasing Expression of the Gene Encoding ZEB1

Our recent findings have revealed that P4/PR also maintains myometrial quiescence by direct genomic actions involving increased expression of the zinc finger E-box-binding transcriptional repressor, ZEB1/TCF8/δEF1 (Fig. 1) (Renthal et al. 2010). ZEB1 and the related transcription factor, ZEB2/SIP1, are E-box-binding transcription factors induced by TGF-β signaling that promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and increased metastasis of cancer cells (Peinado et al. 2007; Yang and Weinberg 2008; Gemmill et al. 2011). Zeb1 was previously reported to be highly expressed in mouse myometrium (Spoelstra et al. 2006) and to be up-regulated by P4/PR (Cochrane et al. 2012). We observed that Zeb1 was expressed at relatively high levels in mouse myometrium at 15.5 d postcoitum (dpc) and declined precipitously toward term (Renthal et al. 2010). Zeb1 expression also declined with preterm labor induction by treatment of pregnant mice with the PR antagonist, RU486, or with the bacterial endotoxin, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to mimic infection-induced preterm labor (Renthal et al. 2010). Analysis of human myometrial biopsies revealed that ZEB1 mRNA and protein were decreased in tissues from women in labor at term, as compared with those from women not in labor (Renthal et al. 2010).

Expression of OXTR and CX43, which are known to be up-regulated near term in a variety of species (Fuchs et al. 1984; Chow and Lye 1994; Ou et al. 1997, 1998; Sparey et al. 1999; Wu et al. 2001), are temporally up-regulated in mouse and human myometrium as ZEB1/2 expression declines (Renthal et al. 2010). CX43 is responsible for the formation of gap junctions in the myometrium, which mediate the intercellular communication required for the synchronous myometrial contractions necessary for successful labor. Mice with a smooth muscle-specific deletion of the Cx43 gene manifest a significant delay in timing of parturition (Doring et al. 2006). Although the action of oxytocin as an uterotonic agent is widely accepted, the role of oxytocin and the OXTR in normal parturition is uncertain, because Oxtr gene knockout mice undergo parturition normally and give birth to live young (Nishimori et al. 1996). Mice deficient in the Oxtr manifest normal timing and duration of parturition (Takayanagi et al. 2005). These unexpected phenotypes may be caused by a functional redundancy of the oxytocin/OXTR signaling system and/or to compensatory up-regulation of other uterotonic systems, such as COX-2 mediated prostaglandin synthesis.

ZEB1/2 may suppress myometrial contractility by negatively regulating OXTR and CX43 expression. Overexpression of ZEB1 or ZEB2 in human myometrial hTERT-HM cells markedly inhibited OXTR and CX43 mRNA levels (Renthal et al. 2010). Using ChIP-qPCR analysis of pregnant mouse myometrium, we observed that endogenous Zeb1 was bound at relatively high levels to E-box-containing regions of the mouse Cxtr and Oxtr promoters at 15.5 dpc, whereas binding was markedly reduced at term (Renthal et al. 2010). To assess the functional roles of ZEB1 and ZEB2 in myometrial contractility, hTERT-HM cells transduced with ZEB1 or ZEB2 expression vectors or with control vectors were embedded in 3D collagen gels. Oxytocin significantly increased contraction of collagen gel matrices embedded with untransduced and β-galactosidase-transduced hTERT-HM cells. However, this action of oxytocin was blocked in the hTERT-HM cells transduced with ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression vectors, demonstrating their inhibitory effect on myometrial contractility in vitro (Renthal et al. 2010).

Importantly, ZEB1 and ZEB2 are direct targets of members of the miR-200 family. In the following sections of this review, we will consider recent studies on the regulation and interactive roles of miRNAs and their targets in the control of myometrial quiescence and contractility in pregnancy and labor.

MicroRNAs SERVE IMPORTANT ROLES IN THE REGULATION OF MYOMETRIAL QUIESCENCE AND CONTRACTILITY

MicroRNAs are evolutionarily conserved regulators of gene expression that play important roles in a variety of biological and pathological processes, including cell differentiation (van Rooij et al. 2008; Braun and Gautel 2011; Turner et al. 2011), immune regulation (Boldin and Baltimore 2012), female reproduction (Chakrabarty et al. 2007; Montenegro et al. 2007, 2009; Renthal et al. 2010; Hawkins et al. 2011; Williams et al. 2012a), and cancer (Mendell 2008; Garzon et al. 2009).

MicroRNAs are ∼22 nucleotide, single-stranded RNAs that typically inhibit gene expression by binding through imperfect base-pairing via their “seed sequences” (nt 2–8 at their 5′-ends) to complementary sites, typically in the 3′-untranslated regions of target mRNAs. This results in inhibition of mRNA translation and/or mRNA degradation (Ruvkun 2008; Bartel 2009). A single miRNA can target multiple components of functionally related gene networks, whereas multiple miRNAs can target a single mRNA. They can act as rheostats or as on–off switches of gene expression. Although the effect of a specific miRNA on the regulation of a target can be subtle, combined actions of several related miRNAs on the same target can have pronounced phenotypic consequences. This is especially true when miRNAs with similar or identical seed sequences are expressed from the same polycistronic transcript and/or when miRNAs encoded within the same transcript have different seed sequences that bind to different sequences within the same target mRNA. It is estimated that ∼1000 miRNAs are encoded by the human genome and these regulate approximately one-third of expressed human genes (van Rooij et al. 2008).

To identify miRNAs and targets that are differentially regulated in quiescent versus contractile pregnant mouse myometrium, we used an unbiased microarray approach. Using coordinated miRNA and gene expression microarray analyses of myometrial tissues from pregnant mice at 15.5 dpc (when the myometrium is quiescent) versus 18.5 dpc (just before labor at 19 dpc), 15 miRNAs were found to be significantly up- and down-regulated (p < 0.05), in association with a body of gestationally regulated genes. Intriguingly, the highly conserved miR-200 family was among the most significantly up-regulated miRNAs at term, whereas the miR-199a/214 cluster was among the most significantly down-regulated (Renthal et al. 2010).

The miR-200 Family and Its Targets

The miR-200 family is comprised of five miRNAs arranged into two conserved, coordinately transcribed (Bracken et al. 2008) clusters (miR-200b/200a/429 and miR-141/200c) that exist on two different chromosomes within the mouse and human genomes (Renthal et al. 2010). miR-200b, 200c, and 429 contain an identical seed sequence; miR-200a and 141 also share an identical seed sequence that differs by only a single nucleotide from those of miR-200b, 200c, and 429. Thus, all members of the miR-200 family likely share mRNA targets. From the results of our gene expression array, TargetScan prediction algorithms (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research) (Grimson et al. 2007), and published findings, we identified a pool of regulated miR-200 targets among those mRNAs down-regulated at term. The two most significantly down-regulated miR-200 targets were the transcriptional repressors, Zeb1 and Zeb2 (Renthal et al. 2010).

The findings of the microarrays were validated in myometrial tissues from gestational series of timed pregnant mice (15.5 dpc–19.5 dpc), in which expression of miR-200b, miR-429 (Renthal et al. 2010), and miR-200a (Williams et al. 2012a) was found to be significantly up-regulated after 17.5 dpc; this corresponded to the time at which Zeb1 and Zeb2 were significantly down-regulated in the myometrium (Renthal et al. 2010). Notably, miR-200b and miR-429 were also significantly up-regulated and ZEB1/2 significantly down-regulated in myometrium of women in labor, as compared with those not in labor (Renthal et al. 2010). Thus, the relationship between miR-200 family members and ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression is conserved between mice and humans.

miR-200 family members and ZEB1 and ZEB2 exist in a double-negative feedback loop in a number of cancer cell lines (Bracken et al. 2008; Burk et al. 2008; Gregory et al. 2008; Brabletz et al. 2011). An inverse relationship between ZEB1 and ZEB2 and the miR-200 family in myometrium was indicated by findings that overexpression of miR-200b/429 mimics in immortalized human myometrial cells caused inhibition of ZEB1 and ZEB2, whereas transduction of mouse myometrial cells in primary culture with recombinant adenoviruses containing ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression vectors caused repression of miR-200s (Renthal et al. 2010). Moreover, using ChIP-qPCR, in vivo binding of Zeb1 to the miR-200b/a/429 promoter in mouse myometrium was observed at relatively high levels at 15.5 dpc; Zeb1 binding declined markedly at 18.5 dpc with the increase in miR-200b and miR-429 expression (Renthal et al. 2010).

The miR-200 family was up-regulated and Zeb1/2 down-regulated in pregnant myometrium using two mouse models of premature parturition, induced either by a single subcutaneous injection of RU486 (Dudley et al. 1996), or by intra-amniotic injection of LPS (Renthal et al. 2010). Conversely, daily injection of P4 into pregnant mice from 15.5 through 18.5 dpc, which inhibited myometrial Cx43 and Oxtr gene expression and delayed labor, caused induction of Zeb1, compared with vehicle injected mice. Surprisingly, P4 injection had no effect on Zeb2. Because both Zeb1 and Zeb2 are expressed at relatively high levels in the myometrium throughout most of pregnancy, this raised the question regarding the factor(s) that cause the pregnancy-associated induction of Zeb2. In studies using cultured mouse myometrial cells, it was observed that Zeb1 overexpression caused a time-dependent up-regulation of Zeb2. This suggests that P4 induction of Zeb1 and the associated inhibition of the miR-200 family, in turn, relieves suppression of Zeb2, allowing its subsequent induction. A direct effect of P4/PR on ZEB1 promoter activity was supported by cotransfection studies of HEK293 cells with a ZEB1-luciferase reporter construct containing –978 bp of ZEB1 5′-flanking sequence (containing the two putative PREs). ZEB1 promoter activity was induced by cotransfection of wild-type PR-B, but not by a PR DNA-binding domain mutant of PR (Renthal et al. 2010).

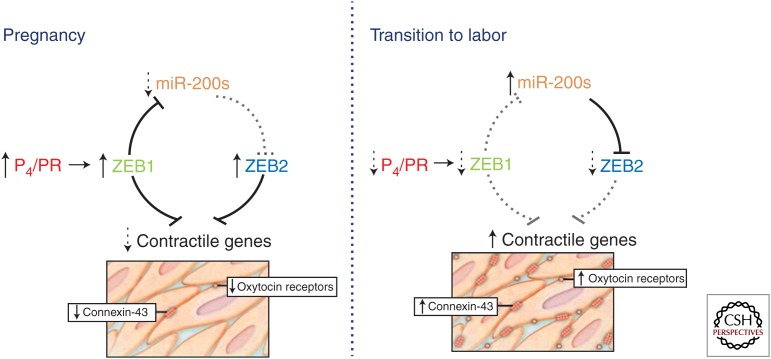

Altogether, these findings support an important role for the miR-200 family and ZEB1/2 in the regulation of myometrial contractility during pregnancy and labor from mice to humans (Fig. 2). Throughout most of gestation, elevated circulating P4 induces myometrial ZEB1 expression via binding of P4/PR to the ZEB1 promoter. Elevated ZEB1 suppresses expression of CX43 and OXTR (Renthal et al. 2010), as well as the miR-200 gene clusters (Bracken et al. 2008; Burk et al. 2008) by binding to response elements within their promoters. The suppression of miR-200 promotes further up-regulation of ZEB1 and increases expression of ZEB2. Together, ZEB1 and ZEB2 inhibit CX43 and OXTR to maintain myometrial quiescence. Near term, signals from mother and fetus, together with a decline in circulating P4 and/or PR function result in an increased inflammatory response within the myometrium and a further decline in PR function, resulting in decreased ZEB1 expression. The decline in ZEB1 allows up-regulation of miR-200 expression, resulting in a further suppression of ZEB1 and inhibition of ZEB2. The combined decline in ZEB1 and ZEB2 then permits marked up-regulation of OXTR and CX43 gene expression and induction of myometrial contractility.

Figure 2.

P4/PR modulation of the ZEB1-miR-200 negative feedback loop regulates contractile gene expression in the pregnant myometrium. During pregnancy, P4/PR increase expression of ZEB1, which acts to suppress the miR-200 family, as well as contraction-associated genes. Decreased expression of the miR-200 family relieves suppression of ZEB2 (as well as ZEB1), resulting in further down-regulation of contractile genes. Near term, a decrease in circulating P4 and/or a decrease in PR function results in down-regulation of ZEB1 expression, and, in turn, an up-regulation of the miR-200 family, further suppressing ZEB1 and ZEB2. This removes the brakes from contractile gene expression, resulting in increased uterine contractility and labor.

Role of the miR-200 Family in the Decline of PR Function Leading to Labor

As discussed above, in humans circulating P4 levels remain elevated throughout pregnancy and into labor, owing to enhanced placental P4 synthesis (Mendelson 2009). Although parturition in rodents is associated with a pronounced decline in P4 production by the corpus luteum, the levels of circulating P4 at term still remain higher than the Kd for binding to PR (Pointis et al. 1981). Moreover, levels of PR remain relatively constant in the majority of species during pregnancy and into labor. Thus, a number of molecular and biochemical changes likely contribute in all species to the decline in PR function leading to parturition.

It has been suggested that increased local metabolism of P4 and a local decline in PR function in the uterus and cervix near term are crucial for the initiation of parturition in all mammals (Runnebaum and Zander 1971; Csapo et al. 1981; Puri and Garfield 1982; Power and Challis 1987; Mahendroo et al. 1999). In myometrium of pregnant women at term, a pronounced decrease was observed in the ratio of P4 to 20α-dihydroprogesterone (20α-OHP) (Runnebaum and Zander 1971), an inactive metabolite of P4 generated by the enzyme 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (20α-HSD), a member of the aldo-ketoreductase (AKR) superfamily (Penning and Drury 2007). Furthermore, targeted deletion of 20α-HSD in mice caused a significant delay in the timing of labor (Piekorz et al. 2005). Notably, the transcription factor, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)5b, is a P4-responsive transcriptional repressor of 20α-HSD in reproductive tissues (Richer et al. 1998; Piekorz et al. 2005). Consequently, STAT5b-deficiency in mice resulted in increased expression of ovarian 20α-HSD, decreased circulating P4, and pregnancy loss during mid-gestation (Piekorz et al. 2005). This mid-gestation pregnancy loss was partially corrected by combined 20α-HSD deficiency (Piekorz et al. 2005). Because 20α-HSD expression in the ovarian corpus luteum remains low throughout pregnancy and increases in association with PGF2α-induced luteolysis at term (Stocco et al. 2001), it was suggested that delayed labor in 20α-Hsd-deficient mice was caused by an inhibition of luteolysis and sustained circulating P4 levels. However, in one of the 20α-Hsd knockout studies, labor was delayed in pregnant gene-targeted mice, despite a fall in circulating P4 levels similar to wild-type mice (Ishida et al. 2007). These findings suggest that mechanisms other than induction of ovarian 20α-HSD may contribute to the functional luteolysis near term and that actions of 20α-HSD to catalyze local metabolism of P4 in the reproductive tract may be more critical for the decline in PR function leading to labor.

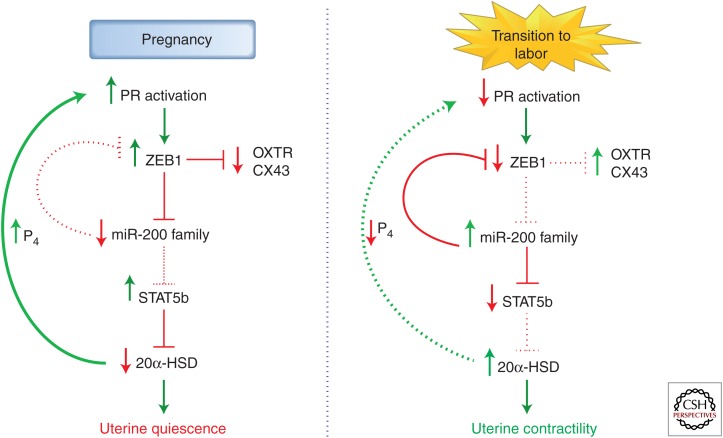

In consideration of the presumed importance of 20α-HSD and STAT5b in the timing of parturition, we were intrigued to discover that STAT5b is a bona fide target of miR-200a (Williams et al. 2012a), which together with other miR-200 family members, increases dramatically at term in myometrium of mice and humans (Williams et al. 2012a). Remarkably, STAT5b mRNA and protein expression were decreased in myometrial tissues of pregnant mice and women in association with the increase in miR-200a at term. Moreover, these gestational changes were associated with decreased binding of endogenous STAT5b to response elements in the 5′-flanking region of the 20α-HSD gene and an induction of 20α-HSD mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity (Williams et al. 2012a). An intermediary role of miR-200a in P4 induction of STAT5b was suggested by the finding that P4 treatment of ovariectomized mice inhibited miR-200a, induced STAT5b and inhibited 20α-HSD expression. Conversely, RU486 injection of timed pregnant mice caused induction of miR-200a, inhibition of STAT5b, and enhanced 20α-HSD mRNA levels. Because the seed sequence of miR-200a is nearly identical to that of miR-200b and miR-429, which are encoded within the same transcript (Renthal et al. 2010), it is likely that other members of the miR-200 family also target myometrial STAT5b and regulate 20α-HSD. Moreover, miR-200a also directly targets ZEB1 and ZEB2 (Gregory et al. 2008), suggesting that near term, increasing levels of miR-200a act cooperatively with miR-200b/429 to inhibit ZEB expression and derepress contraction-associated genes.

Together, our findings suggest that the elevated P4 and PR activity in the myometrium during most of pregnancy causes induction of ZEB1 and inhibition of miR-200 expression, which is permissive for increased expression of STAT5b. The increased STAT5b maintains low levels of 20α-HSD expression and allows tissue levels of P4 and PR function to remain elevated (Fig. 3). The increased inflammatory response leading to term or preterm labor causes a decline in PR function and associated decrease in ZEB1. This allows up-regulation of miR-200a and other miR-200 family members, inhibition of STAT5b and induction of 20α-HSD expression and activity. The increased local metabolism of P4 to inactive products in the myometrium contributes to the further decline in PR function and progression to labor (Fig. 3). These studies have revealed a robust positive feed forward loop wherein an initially modest decline in PR function and induction of miR-200 expression can escalate to an intensity that effectively reduces tissue P4 to levels significantly below the Kd for PR binding. This culminates in further decline of ZEBs, which permits the induction of OXTR and CX43 gene expression in response to increased NF-κB activation.

Figure 3.

Increased miR-200 expression near term inhibits PR function by targeting STAT5b and enhancing P4 metabolism in myometrium. During pregnancy, elevated P4/PR function increases expression of transcription factor ZEB1, which inhibits expression of miR-200a and other members of the miR-200 family. The decreased levels of miR-200 enhance expression of STAT5b, which represses 20α-HSD to sustain elevated P4 levels within the myometrium. During the transition to term and preterm labor, an increased inflammatory response promotes a decline in PR function in myometrium, resulting in decreased levels of ZEB1, which releases repression of the miR-200 family. The increased levels of miR-200s inhibit STAT5b expression, releasing repression of 20α-HSD. The increase in 20α-HSD expression, in turn, catalyzes metabolism of P4 to reduce local P4 levels in the myometrium and further promote the progression of labor. The decline in PR function may act in a positive feed forward manner to further increase miR-200 expression, suppress STAT5b, and up-regulate 20α-HSD.

Other Mechanisms for the Decline in PR Function Leading to Parturition

In addition to increased metabolism of P4 to inactive steroids, the decline in PR function near term also is associated with a decrease in PR coactivators (Condon et al. 2003; Leite et al. 2004), with increased expression of the inhibitory PR isoform, PR-C, an increase in the ratio of PR-A to PR-B (Mesiano et al. 2002; Condon et al. 2006; Tan et al. 2012) and a physical interaction of PR with NF-κB p65 (Kalkhoven et al. 1996; Hardy et al. 2006, 2008), which is activated in the myometrium during late gestation (Condon et al. 2004, 2006). Furthermore, increased circulating E2 levels (Challis 1971; Buster et al. 1979) and enhanced ERα activity (Wu et al. 1995; Mesiano et al. 2002; Mesiano and Welsh 2007; Welsh et al. 2012) near term also promote a cascade of proinflammatory events leading to the decline in PR function and parturition. Estrogens induce an influx of macrophages and neutrophils into the uterus and antagonize the anti-inflammatory actions of P4/PR (Tibbetts et al. 1999; Mesiano et al. 2002). ERα activation also promotes labor by enhancing transcription of genes for OXTR (Murata et al. 2003), CX43 (Piersanti and Lye 1995) and COX-2 (Mesiano et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012b), which is expressed at low to undetectable levels in the uterus throughout most of pregnancy, but is highly up-regulated at term (Tsuboi et al. 2000; Engstrom 2001; Williams et al. 2012b).

miR-199a-3p and miR-214 Are Coordinately Down-Regulated in the Pregnant Myometrium Toward Term, Whereas Their Target COX-2 Is Increased

MicroRNAs that were significantly down-regulated near term in our microarray analysis included miR-199a-3p, known to target COX-2 mRNA (Chakrabarty et al. 2007) and miR-214, which targets PTEN and activates the Akt pathway (Yang et al. 2008; Yin et al. 2010). Mature miR-199a and miR-214 are processed from the same precursor/pri-miR-199a as part of a 6-kb antisense transcript (Dnm3os) from the intron of the Dynamin3 (Dnm3) gene, which is highly expressed in pregnant uterus (Loebel et al. 2005). As noted, the expression of COX-2 increases in the pregnant myometrium during late gestation and is believed to be critical for the increase in contractile PGF2α (Olson et al. 2003) required for the progression to labor.

Our studies revealed that COX-2 also is a bona fide target of miR-214 (Williams et al. 2012b). In pregnant mouse myometrium, Cox-2 protein levels were significantly increased at 18.5 dpc and during labor, compared with 15.5 dpc, as miR-199a-3p and miR-214 reciprocally declined. However, Cox-2 mRNA levels remained low through 18.5 dpc and increased only during labor. Our findings suggested that miR-199a-3p/miR-214 may exert a direct effect on COX-2 mRNA translation, rather than on COX-2 mRNA stability. Accordingly, overexpression of miR-199a-3p and miR-214 in cultured human myometrial cells inhibited COX-2 protein, but had no effect on COX-2 mRNA levels (Williams et al. 2012b). Moreover, in myometrial samples from women in labor versus not in labor at term, in the absence of underlying infection, COX-2 mRNA was unchanged during labor, whereas COX-2 protein levels were markedly increased (Williams et al. 2012b). Thus, these findings suggest that COX-2 expression in the pregnant myometrium is regulated at the level of mRNA translation and the miR-199a/214 cluster may serve an important role in this regulation. Our studies further revealed that myometrial levels of miR-199a-3p and miR-214 were significantly decreased in an LPS-induced mouse model of preterm labor, whereas Cox-2 expression increased. Moreover, the physiological relevance of the miR-199a/214-COX-2 relationship in the regulation of myometrial contractility was further supported by the finding that miR-199a/214 overexpression blocked TNF-α-induced myometrial cell contractility to the same extent as the cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin (Williams et al. 2012b).

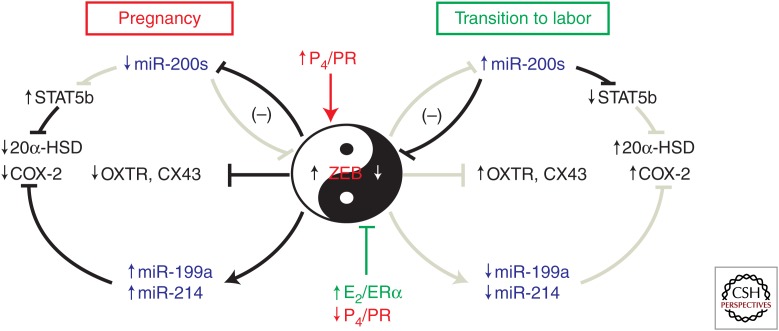

As discussed previously, P4 and E2 exert opposing effects on myometrial quiescence/contractility. Accordingly, E2 treatment of ovariectomized mice suppressed, whereas P4 enhanced, uterine miR-199a-3p/214 expression. Interestingly, these opposing hormonal effects were found to be mediated by Zeb1, which is induced by P4 (Spoelstra et al. 2006; Renthal et al. 2010), inhibited by E2 and activates miR199a/214 transcription (Williams et al. 2012b). Thus, these findings have uncovered an intriguing pivotal role of ZEB1 as a negative regulator of the miR-200b/200a/429 cluster and a positive regulator of the miR-199a/214 cluster that is under opposing control by P4 and E2 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

ZEB1 serves a pivotal role by mediating opposing actions of P4 and E2 on myometrial contractility during pregnancy and labor. During pregnancy, increased levels of P4 and increased PR function promote up-regulation of ZEB1 in myometrium. ZEB inhibits expression of the miR-200 family and suppresses OXTR and CX43. The decline in miR-200 levels further up-regulates ZEB1 and increases ZEB2, which bind response elements upstream of the miR-199a/214 cluster to enhance its expression, causing suppression of COX-2, and preventing synthesis of contractile prostaglandins. The decreased levels of miR-200s allow up-regulation of another target, STAT5b, which inhibits expression of 20α-HSD, allowing local levels of P4 in myometrium to remain elevated. During the transition to labor, the decline in myometrial P4/PR function and increase in circulating E2 and ERα activity cause down-regulation of ZEB1. This leads to induction of the miR-200 family, which further suppresses ZEB1 and ZEB2, allowing up-regulation of OXTR and CX43 expression. The decline in ZEBs also causes decreased expression of the miR199a/214 cluster, which allows up-regulation of COX-2 and increased synthesis of contractile prostaglandins. The increase in miR-200 expression inhibits STAT5b, permitting increased transcription of 20α-HSD to promote increased metabolism of P4 to inactive products in myometrium. Collectively, these molecular events contribute to the initiation of uterine contractility, leading to labor.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The opposing mechanisms that underlie the maintenance of myometrial quiescence throughout most of pregnancy and its transition to a contractile phenotype leading to labor are multifactorial and interrelated. It is clear that P4/PR serve a key role in the maintenance of pregnancy through anti-inflammatory actions and inhibition of contractile gene expression. These effects are mediated by PR antagonism of inflammatory transcription factor activation (e.g., NF-κB and AP-1) and by up-regulation of the transcriptional inhibitor, ZEB1, which acts together with ZEB2 to inhibit expression of contractile genes. Recent studies have provided intriguing evidence for the central role of ZEB1 in the regulation of two opposing pathways regulated by clusters of evolutionarily conserved miRNAs (Fig. 4). Throughout most of pregnancy, increased circulating and tissue levels of P4 activate PR transcriptional activity resulting in up-regulation of ZEB1 expression. ZEB1 inhibits transcription of members of the miR-200 family, as well as the contractile genes, OXTR and CX43. Elevated P4/PR levels and suppression of the miR-200 family also allow up-regulation of STAT5b, which inhibits expression of the P4-metabolizing enzyme, 20α-HSD. This permits myometrial tissue levels of P4 to remain elevated, resulting in enhanced PR function to sustain myometrial quiescence, and to suppress NF-κB activation of inflammatory genes, such as COX-2. The increased expression of ZEB1 and ZEB2 also cause up-regulation of miR-199a-3p and miR-214, which directly target COX-2, resulting in suppression of prostaglandin synthesis. Near term, the increased inflammatory response caused by uterine stretch, increased E2 production and/or ERα activity and other signaling molecules produced by mother and fetus (Condon et al. 2004; Montalbano et al. 2013) initiate a decline in PR function. This further enhances NF-κB activation and the inflammatory response. The decreased P4/PR activity and increased in E2/ERα signaling promote a decline in ZEB1, a reciprocal increase in miR-200 expression, with further inhibition of ZEB1 and of ZEB2. This allows for induction of OXTR and CX43 gene expression. The increased levels of miR-200s cause suppression of STAT5b, allowing for induction of 20α-HSD, which promotes increased metabolism of P4 to inactive products within the myometrium, contributing to the decline in PR function. The decreased levels of ZEB1/2 also result in decreased expression of miR-199a-3p and miR-214, which allow for increased COX-2 protein expression with synthesis of contractile prostaglandins. Collectively, these highly integrated molecular events coordinated by conserved miRNAs and their targets result in enhanced myometrial contractility leading to parturition. Thus, we are developing an understanding of the molecular events that underlie the maintenance of uterine quiescence during pregnancy and the activation of contractility leading to labor. In future investigations, we hope to apply these findings to development of therapeutic strategies to prevent preterm birth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors’ research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Grant 5-P01-HD011149) and the March of Dimes Foundation (Prematurity Research Grant No. #21-FY14–146).

Footnotes

Editors: Diana W. Bianchi and Errol R. Norwitz

Additional Perspectives on Molecular Approaches to Reproductive and Newborn Medicine available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Auphan N, DiDonato JA, Rosette C, Helmberg A, Karin M. 1995. Immunosuppression by glucocorticoids: Inhibition of NF-κB activity through induction of IκB synthesis. Science 270: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin ASJ. 1996. The NF-κB and IκB proteins: New discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol 14: 649–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, Vera GC, Rohde S, Say L, et al. 2012. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 379: 2162–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldin MP, Baltimore D. 2012. MicroRNAs, new effectors and regulators of NF-κB. Immunol Rev 246: 205–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz S, Bajdak K, Meidhof S, Burk U, Niedermann G, Firat E, Wellner U, Dimmler A, Faller G, Schubert J, et al. 2011. The ZEB1/miR-200 feedback loop controls Notch signalling in cancer cells. EMBO J 30: 770–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken CP, Gregory PA, Kolesnikoff N, Bert AG, Wang J, Shannon MF, Goodall GJ. 2008. A double-negative feedback loop between ZEB1-SIP1 and the microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 68: 7846–7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Gautel M. 2011. Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, Brabletz T. 2008. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep 9: 582–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buster JE, Chang RJ, Preston DL, Elashoff RM, Cousins LM, Abraham GE, Hobel CJ, Marshall JR. 1979. Interrelationships of circulating maternal steroid concentrations in third trimester pregnancies. II: C18 and C19 steroids: Estradiol, estriol, dehydroepiandrosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, Δ5-androstenediol, Δ4-androstenedione, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 48: 139–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty A, Tranguch S, Daikoku T, Jensen K, Furneaux H, Dey SK. 2007. MicroRNA regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 15144–15149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JR. 1971. Sharp increase in free circulating oestrogens immediately before parturition in sheep. Nature 229: 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. 2000. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev 21: 514–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Hardy DB, Mendelson CR. 2011. Progesterone receptor inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells via induction of MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1/DUSP1). J Biol Chem 286: 43091–43102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow L, Lye SJ. 1994. Expression of the gap junction protein connexin-43 is increased in the human myometrium toward term and with the onset of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170: 788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane DR, Spoelstra NS, Richer JK. 2012. The role of miRNAs in progesterone action. Mol Cell Endocrinol 357: 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Wilson JM, Mendelson CR. 2003. A decline in progesterone receptor coactivators in the pregnant uterus at term may antagonize progesterone receptor function and contribute to the initiation of labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 9518–9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Jeyasuria P, Faust JM, Mendelson CR. 2004. Surfactant protein secreted by the maturing mouse fetal lung acts as a hormone that signals the initiation of parturition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 4978–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Hardy DB, Kovaric K, Mendelson CR. 2006. Upregulation of the progesterone receptor (PR)-C isoform in laboring myometrium by activation of nuclear factor-κB may contribute to the onset of labor through inhibition of PR function. Mol Endocrinol 20: 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conneely OM, Maxwell BL, Toft DO, Schrader WT, O’Malley BW. 1987. The A and B forms of the chicken progesterone receptor arise by alternate initiation of translation of a unique mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 149: 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox SM, Casey ML, MacDonald PC. 1997. Accumulation of interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 in amniotic fluid: A sequela of labour at term and preterm. Hum Reprod Update 3: 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csapo AI, Eskola J, Tarro S. 1981. Gestational changes in the progesterone and prostaglandin F levels of the guinea-pig. Prostaglandins 21: 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroo BJ, Archer TK. 2002. Differential activation of the IκBα and mouse mammary tumor virus promoters by progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 81: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Yu C, Shynlova O, Challis JR, Rennie PS, Lye SJ. 2009. p54nrb is a transcriptional corepressor of the progesterone receptor that modulates transcription of the labor-associated gene, connexin 43 (Gja1). Mol Endocrinol 23: 1147–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doring B, Shynlova O, Tsui P, Eckardt D, Janssen-Bienhold U, Hofmann F, Feil S, Feil R, Lye SJ, Willecke K. 2006. Ablation of connexin43 in uterine smooth muscle cells of the mouse causes delayed parturition. J Cell Sci 119: 1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley DJ, Branch DW, Edwin SS, Mitchell MD. 1996. Induction of preterm birth in mice by RU486. Biol Reprod 55: 992–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom T. 2001. The regulation by ovarian steroids of prostaglandin synthesis and prostaglandin-induced contractility in non-pregnant rat myometrium. Modulating effects of isoproterenol. J Endocrinol 169: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esplin MS, Peltier MR, Hamblin S, Smith S, Fausett MB, Dildy GA, Branch DW, Silver RM, Adashi EY. 2005. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression is increased in human gestational tissues during term and preterm labor. Placenta 26: 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AR, Fuchs F, Husslein P, Soloff MS. 1984. Oxytocin receptors in the human uterus during pregnancy and parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol 150: 734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R, Calin GA, Croce CM. 2009. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Med 60: 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemmill RM, Roche J, Potiron VA, Nasarre P, Mitas M, Coldren CD, Helfrich BA, Garrett-Mayer E, Bunn PA, Drabkin HA. 2011. ZEB1-responsive genes in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 300: 66–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Araujo B, Toledo Lobo MV, Gutierrez-Salmeron M, Gutierrez-Pitalua J, Ropero S, Angulo JC, Chiloeches A, Lasa M. 2014. Dual specificity phosphatase 1 expression inversely correlates with NF-κB activity and expression in prostate cancer and promotes apoptosis through a p38 MAPK dependent mechanism. Mol Oncol 8: 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ. 2008. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 10: 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. 2007. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DB, Mendelson CR. 2006. Progesterone receptor (PR) antagonism of the inflammatory signals leading to labor. Fetal Maternal Med Rev 17: 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DB, Janowski BA, Corey DR, Mendelson CR. 2006. Progesterone receptor (PR) plays a major anti-inflammatory role in human myometrial cells by antagonism of NF-κB activation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) expression. Mol Endocrinol 20: 2724–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy DB, Janowski BA, Chen C-C, Mendelson CR. 2008. Progesterone receptor inhibits aromatase and inflammatory response pathways in breast cancer cells via ligand-dependent and ligand-independent mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol 22: 1812–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock JC, Keller P, Muleba N, Mayhew BA, Casey BM, Rainey WE, Word RA. 2005. Human myometrial gene expression before and during parturition. Biol Reprod 72: 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SM, Buchold GM, Matzuk MM. 2011. Minireview: The roles of small RNA pathways in reproductive medicine. Mol Endocrinol 25: 1257–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JS, Miller L, Platt JS. 1998. Hormonal regulation of uterine macrophages. Dev Immunol 6: 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida M, Choi JH, Hirabayashi K, Matsuwaki T, Suzuki M, Yamanouchi K, Horai R, Sudo K, Iwakura Y, Nishihara M. 2007. Reproductive phenotypes in mice with targeted disruption of the 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene. J Reprod Dev 53: 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE, Corey DR. 2007. Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nat Chem Biol 3: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoven E, Wissink S, van der Saag PT, van der BB. 1996. Negative interaction between the RelA(p65) subunit of NF-κB and the progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem 271: 6217–6224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner P, Bocquel MT, Turcotte B, Garnier JM, Horwitz KB, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H. 1990. Transient expression of human and chicken progesterone receptors does not support alternative translational initiation from a single mRNA as the mechanism generating two receptor isoforms. J Biol Chem 265: 12163–12167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushic C, Frauendorf E, Rossoll RM, Richardson JM, Wira CR. 1998. Influence of the estrous cycle on the presence and distribution of immune cells in the rat reproductive tract. Am J Reprod Immunol 39: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RW, Carr GG, Riley SC. 1997. The inhibition of synthesis of a β-chemokine, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) by progesterone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 239: 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Sooranna SR, Terzidou V, Christian M, Brosens J, Huhtinen K, Poutanen M, Barton G, Johnson MR, Bennett PR. 2012. Interactions between inflammatory signals and the progesterone receptor in regulating gene expression in pregnant human uterine myocytes. J Cell Mol Med 16: 2487–2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite RS, Brown AG, Strauss JF III. 2004. Tumor necrosis factor-α suppresses the expression of steroid receptor coactivator-1 and -2: A possible mechanism contributing to changes in steroid hormone responsiveness. FASEB J 18: 1418–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebel DA, Tsoi B, Wong N, Tam PP. 2005. A conserved noncoding intronic transcript at the mouse Dnm3 locus. Genomics 85: 782–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon JA, Elliott CL, Hills F, Bennett PR. 2003. Progesterone represses interleukin-8 and cyclo-oxygenase-2 in human lower segment fibroblast cells and amnion epithelial cells. Biol Reprod 69: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA Jr, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. 1995. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev 9: 2266–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendroo MS, Porter A, Russell DW, Word RA. 1999. The parturition defect in steroid 5α-reductase type 1 knockout mice is due to impaired cervical ripening. Mol Endocrinol 13: 981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JT. 2008. miRiad roles for the miR-17–92 cluster in development and disease. Cell 133: 217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR. 2009. Minireview: Fetal-maternal hormonal signaling in pregnancy and labor. Mol Endocrinol 23: 947–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR, Boggaram V. 1990. Hormonal and developmental regulation of pulmonary surfactant synthesis in fetal lung. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 4: 351–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson CR, Condon JC. 2005. New insights into the molecular endocrinology of parturition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 93: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesiano S, Welsh TN. 2007. Steroid hormone control of myometrial contractility and parturition. Semin Cell Dev Biol 18: 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesiano S, Chan EC, Fitter JT, Kwek K, Yeo G, Smith R. 2002. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87: 2924–2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Hunt JS. 1998. Regulation of TNF-α production in activated mouse macrophages by progesterone. J Immunol 160: 5098–5104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MD, MacDonald PC, Casey ML. 1984. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 synthesis in human amnion cells maintained in monolayer culture by a substance(s) in amniotic fluid. Prostaglandins Leukot Med 15: 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalbano AP, Hawgood S, Mendelson CR. 2013. Mice deficient in surfactant protein A (SP-A) and SP-D or in TLR2 manifest delayed parturition and decreased expression of inflammatory and contractile genes. Endocrinology 154: 483–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro D, Romero R, Pineles BL, Tarca AL, Kim YM, Draghici S, Kusanovic JP, Kim JS, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. 2007. Differential expression of microRNAs with progression of gestation and inflammation in the human chorioamniotic membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197: 289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro D, Romero R, Kim SS, Tarca AL, Draghici S, Kusanovic JP, Kim JS, Lee DC, Erez O, Gotsch F, et al. 2009. Expression patterns of microRNAs in the chorioamniotic membranes: A role for microRNAs in human pregnancy and parturition. J Pathol 217: 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Narita K, Honda K, Matsukawa S, Higuchi T. 2003. Differential regulation of estrogen receptor α and β mRNAs in the rat uterus during pregnancy and labor: Possible involvement of estrogen receptors in oxytocin receptor regulation. Endocr J 50: 579–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimori K, Young LJ, Guo Q, Wang Z, Insel TR, Matzuk MM. 1996. Oxytocin is required for nursing but is not essential for parturition or reproductive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 11699–11704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM. 2003. The role of prostaglandins in the initiation of parturition. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 17: 717–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM, Zaragoza DB, Shallow MC, Cook JL, Mitchell BF, Grigsby P, Hirst J. 2003. Myometrial activation and preterm labour: Evidence supporting a role for the prostaglandin F receptor—A review. Placenta 24: S47–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman I, Young A, Ledingham MA, Thomson AJ, Jordan F, Greer IA, Norman JE. 2003. Leukocyte density and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human fetal membranes, decidua, cervix and myometrium before and during labour at term. Mol Hum Reprod 9: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou CW, Orsino A, Lye SJ. 1997. Expression of connexin-43 and connexin-26 in the rat myometrium during pregnancy and labor is differentially regulated by mechanical and hormonal signals. Endocrinology 138: 5398–5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou CW, Chen ZQ, Qi S, Lye SJ. 1998. Increased expression of the rat myometrial oxytocin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid during labor requires both mechanical and hormonal signals. Biol Reprod 59: 1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. 2007. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer 7: 415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier MR, Drobek CO, Bhat G, Saade G, Fortunato SJ, Menon R. 2012. Amniotic fluid and maternal race influence responsiveness of fetal membranes to bacteria. J Reprod Immunol 96: 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning TM, Drury JE. 2007. Human aldo-keto reductases: Function, gene regulation, and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Arch Biochem Biophys 464: 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekorz RP, Gingras S, Hoffmeyer A, Ihle JN, Weinstein Y. 2005. Regulation of progesterone levels during pregnancy and parturition by signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 and 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Mol Endocrinol 19: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersanti M, Lye SJ. 1995. Increase in messenger ribonucleic acid encoding the myometrial gap junction protein, connexin-43, requires protein synthesis and is associated with increased expression of the activator protein-1, c-fos. Endocrinology 136: 3571–3578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointis G, Rao B, Latreille MT, Mignot TM, Cedard L. 1981. Progesterone levels in the circulating blood of the ovarian and uterine veins during gestation in the mouse. Biol Reprod 24: 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power SG, Challis JR. 1987. The effects of gestational age and intrafetal ACTH administration on the concentration of progesterone in the fetal membranes, endometrium, and myometrium of pregnant sheep. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 65: 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri CP, Garfield RE. 1982. Changes in hormone levels and gap junctions in the rat uterus during pregnancy and parturition. Biol Reprod 27: 967–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauk PN, Chiao JP. 2000. Interleukin-1 stimulates human uterine prostaglandin production through induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am J Reprod Immunol 43: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal NE, Chen CC, Williams KC, Gerard RD, Prange-Kiel J, Mendelson CR. 2010. miR-200 family and targets, ZEB1 and ZEB2, modulate uterine quiescence and contractility during pregnancy and labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 20828–20833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal NE, Williams KC, Mendelson CR. 2013. MicroRNAs-mediators of myometrial contractility during pregnancy and labour. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9: 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer JK, Lange CA, Manning NG, Owen G, Powell R, Horwitz KB. 1998. Convergence of progesterone with growth factor and cytokine signaling in breast cancer. Progesterone receptors regulate signal transducers and activators of transcription expression and activity. J Biol Chem 273: 31317–31326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Espinoza J, Goncalves LF, Kusanovic JP, Friel L, Hassan S. 2007. The role of inflammation and infection in preterm birth. Semin Reprod Med 25: 21–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. 2014. Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes. Science 345: 760–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runnebaum B, Zander J. 1971. Progesterone and 20α-dihydroprogesterone in human myometrium during pregnancy. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh) 150: 3–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G. 2008. The perfect storm of tiny RNAs. Nat Med 14: 1041–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinman RI, Cogswell PC, Lofquist AK, Baldwin AS. 1995. Role of transcriptional activation of IκBα in mediation of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Science 270: 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw G, Renfree MB. 2001. Fetal control of parturition in marsupials. Reprod Fertil Dev 13: 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shynlova O, Tsui P, Dorogin A, Lye SJ. 2008. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL-2) integrates mechanical and endocrine signals that mediate term and preterm labor. J Immunol 181: 1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JM, Kwun JE, O’Brien JA, Rosenfeld CR, Odom MJ. 1988. The concentration of the 35-kDa surfactant apoprotein in amniotic fluid from normal and diabetic pregnancies. Pediatric Res 24: 728–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff MS, Cook DL Jr, Jeng YJ, Anderson GD. 2004. In situ analysis of interleukin-1-induced transcription of cox-2 and IL-8 in cultured human myometrial cells. Endocrinology 145: 1248–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sooranna SR, Lee Y, Kim LU, Mohan AR, Bennett PR, Johnson MR. 2004. Mechanical stretch activates type 2 cyclooxygenase via activator protein-1 transcription factor in human myometrial cells. Mol Hum Reprod 10: 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparey C, Robson SC, Bailey J, Lyall F, Europe-Finner GN. 1999. The differential expression of myometrial connexin-43, cyclooxygenase-1 and -2, and Gsα proteins in the upper and lower segments of the human uterus during pregnancy and labor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84: 1705–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoelstra NS, Manning NG, Higashi Y, Darling D, Singh M, Shroyer KR, Broaddus RR, Horwitz KB, Richer JK. 2006. The transcription factor ZEB1 is aberrantly expressed in aggressive uterine cancers. Cancer Res 66: 3893–3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco CO, Chedrese J, Deis RP. 2001. Luteal expression of cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase genes in late pregnant rats: Effect of luteinizing hormone and RU486. Biol Reprod 65: 1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, et al. 2005. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 16096–16101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H, Yi L, Rote NS, Hurd WW, Mesiano S. 2012. Progesterone receptor-A and -B have opposite effects on proinflammatory gene expression in human myometrial cells: Implications for progesterone actions in human pregnancy and parturition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: E719–E730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AJ, Telfer JF, Young A, Campbell S, Stewart CJ, Cameron IT, Greer IA, Norman JE. 1999. Leukocytes infiltrate the myometrium during human parturition: Further evidence that labour is an inflammatory process. Hum Reprod 14: 229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts TA, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. 1999. Progesterone via its receptor antagonizes the pro-inflammatory activity of estrogen in the mouse uterus. Biol Reprod 60: 1158–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi K, Sugimoto Y, Iwane A, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto S, Ichikawa A. 2000. Uterine expression of prostaglandin H2 synthase in late pregnancy and during parturition in prostaglandin F receptor-deficient mice. Endocrinology 141: 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner ML, Schnorfeil FM, Brocker T. 2011. MicroRNAs regulate dendritic cell differentiation and function. J Immunol 187: 3911–3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooij E, Liu N, Olson EN. 2008. MicroRNAs flex their muscles. Trends Genet 24: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe W, Plaisance S, Boone E, De Bosscher K, Schmitz ML, Fiers W, Haegeman G. 1998. p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are required for nuclear factor-κB p65 transactivation mediated by tumor necrosis factor. J Biol Chem 273: 3285–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh T, Johnson M, Yi L, Tan H, Rahman R, Merlino A, Zakar T, Mesiano S. 2012. Estrogen receptor (ER) expression and function in the pregnant human myometrium: Estradiol via ERα activates ERK1/2 signaling in term myometrium. J Endocrinol 212: 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KC, Renthal NE, Condon JC, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR. 2012a. MicroRNA-200a serves a key role in the decline of progesterone receptor function leading to term and preterm labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 7529–7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KC, Renthal NE, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR. 2012b. The microRNA (miR)-199a/214 cluster mediates opposing effects of progesterone and estrogen on uterine contractility during pregnancy and labor. Mol Endocrinol 26: 1857–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WX, Myers DA, Nathanielsz PW. 1995. Changes in estrogen receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in sheep fetal and maternal tissues during late gestation and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 172: 844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WX, Ma XH, Zhang Q, Nathanielsz PW. 2001. Characterization of topology-, gestation- and labor-related changes of a cassette of myometrial contraction-associated protein mRNA in the pregnant baboon myometrium. J Endocrinol 171: 445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Weinberg RA. 2008. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: At the crossroads of development and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell 14: 818–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Kong W, He L, Zhao JJ, O’Donnell JD, Wang J, Wenham RM, Coppola D, Kruk PA, Nicosia SV, et al. 2008. MicroRNA expression profiling in human ovarian cancer: miR-214 induces cell survival and cisplatin resistance by targeting PTEN. Cancer Res 68: 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin G, Chen R, Alvero AB, Fu HH, Holmberg J, Glackin C, Rutherford T, Mor G. 2010. TWISTing stemness, inflammation and proliferation of epithelial ovarian cancer cells through MIR199A2/214. Oncogene 29: 3545–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]