Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of irinotecan/cisplatin (IP) and etoposide/cisplatin (EP) in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) and the distribution of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1). The relationship between UGT1A1 genotypes and patient outcomes was also assessed.

Method

Patients with untreated ES-SCLC were randomly assigned to receive either IP or EP, and blood specimens were collected to test the genotypes of UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*6. The association of efficacy and toxicity of an IP regimen with UGT1A1 genotype was analyzed.

Results

Of the 62 patients enrolled from three institutions, 30 patients were in the IP and 32 patients were in the EP arms, respectively. Disease control rates with IP and EP were 83.3% and 71.9%, respectively (P = 0.043). Median progression-free survival for IP and EP were both six months. Median overall survival for IP and EP were 18.1 and 15.8 months respectively, without significant difference. Grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia was more common with EP (18.8% vs. 6.7%; P = 0.035), while the incidence of diarrhea was higher with IP (70% vs. 15.6%; P = 0.008). The incidence of grade 1-4 late-onset diarrhea of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous UGT1A1*28 were 65.0%, 85.7%, and 66.7%, respectively (P = 0.037). UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and chemotherapy cycles were essential factors affecting grade 1-4 late-onset diarrhea in logistic regression analysis.

Conclusions

The efficacy of the IP regimen was similar to the EP regimen for untreated ES-SCLC. UGT1A1 polymorphisms were associated with late-onset diarrhea; however, there was no influence on efficacy.

Keywords: Cisplatin, etoposide, extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, irinotecan, UGT1A1

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in China with an estimated 610 000 new cases in 2010.1 Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) now accounts for 10–15% of all newly diagnosed lung cancer cases, and 60–70% of patients present with extensive stage (ES).2 Over the past 20 years, standard therapy for most patients with ES-SCLC has been either carboplatin or cisplatin in combination with etoposide.3

In 2002, Japanese investigators reported superior results with the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan combined with cisplatin (IP) compared with standard therapy with etoposide plus cisplatin (EP) in a randomized phase III trial comprising 154 patients with ES-SCLC.4 Prolonged median overall survival (OS) (12.8 vs. 9.4 months; P = 0.002) and a non-significantly higher two-year survival rate of 19.5% versus 5.2% were observed in the IP treatment arm compared with the EP arm. Patients in the EP arm experienced significantly higher rates of grade 3/4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, but lower rates of grade 3/4 diarrhea than those in the IP arm. However, two subsequent large phase III trials performed in the United States (US) comparing IP with EP failed to show a significant difference in response rate or OS between the regimens.5,6 Moreover, grade 3/4 hematological toxic effects were more frequent in both EP and IP arms in Japanese compared to Western patients.7 It is possible that the differences in efficacy and toxicity in these randomized trials may partly be because the polymorphisms of genes involved in the metabolism or transport of chemotherapy vary among ethnic populations.6

The present study was designed to compare the efficacy of EP and IP in untreated patients with ES-SCLC in a multicenter setting. Additionally, we sought to explore the distribution of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) polymorphisms and to find out the relationship between UGT1A1 genotypes and patient outcomes, as well as incidence of diarrhea after chemotherapy.

Methods

Patient selection

From April 2010 to December 2012, a consecutive case series of 62 patients with ES-SCLC were enrolled in this study (Table 1). Patients had cytologically or histologically confirmed SCLC. ES disease was defined as extrathoracic metastatic disease, malignant pleural effusion, bilateral or contralateral supraclavicular lymph node metastasis, or contralateral hilar lymph node metastasis. Eligibility criteria included: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0–2; a life expectancy of at least three months; measurable lesions; age 18–70 years; adequate hematologic function (neutrophil count ≥ 2.0 × 109/L, platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L, hemoglobin ≥ 90 g/L); and no severe hepatic or renal dysfunction (a bilirubine ≤ 1.5 × upper limit of normal [UNL] and creatinine, urea nitrogen ≤UNL, ALT,AST,ALP ≤ 2.5 × UNL or ALT,AST ≤ 5 × UNL if liver metastases were present or ALP ≤ 10 × UNL if bone metastases). Patients with central nervous system metastases were eligible if they were asymptomatic and it had been a minimum of four weeks since treatment. Newly diagnosed and relapsed or metastases after radiotherapy or surgery were permitted if it had been at least six months since adjuvant chemotherapy had been administered.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | IP (n = 30) | EP (n = 32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.124 | ||

| Male | 21 (70%) | 26 (81.3%) | |

| Female | 9 (30%) | 6 (18.8%) | |

| Median age | 59 | 57 | 0.172 |

| ECOG | 0.079 | ||

| 0 | 3 (10%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| 1 | 24 (80%) | 27 (84.4%) | |

| 2 | 3 (10%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Metastatic site | 0.386 | ||

| Lung | 8 (26.6%) | 10 (31.3%) | |

| Liver | 6 (20%) | 5 (15.6%) | |

| CNS | 2 (6.7%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Adrenal | 3 (10%) | 2 (6.2%) | |

| Bone | 9 (30%) | 7 (21.9%) | |

| Distant lymph node | 2 (6.7%) | 5 (15.6%) |

CNS, central nervous system; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EP, etoposide plus cisplatin; IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin.

The exclusion criteria were: infection; myocardial infarction within the preceding three months; symptomatic brain metastases; administration of radiotherapy less than four weeks previous; and pregnancy or breast-feeding.

The ethics committees of CAMS & PUMC, Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, and China-Japan Friendship Hospital, approved the study. All patients were required to provide written informed consent.

Treatment assignment and genotyping procedures

The IP regimen consisted of a maximum of six cycles of irinotecan 65 mg/m2 of body-surface area on days one and eight, and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 of body-surface area on day one. The EP regimen consisted of a maximum of six cycles of etoposide 100 mg/m2 of body-surface area from days one to three and cisplatin 75 mg/m2 of body-surface area on day one. Cycle length for the two arms was three weeks. If necessary, the acceptable dose adjustment was within ±5% per investigator discretion. Both regimens required hydration and the administration of antiemetic drugs (5-hydroxytryptamin3 [5-HT3] receptor antagonist).

Peripheral blood (2 mL) was obtained from each patient three times: before the first cycle, after the second cycle, and after the last cycle of chemotherapy. Blood was refrigerated at −20°C. Genomic DNA was directly extracted from blood specimens, and the UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28 genotypes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction. Polymorphic regions were analyzed by a bi-direct sequencing method.

Evaluation

Pretreatment baseline evaluation included complete medical history and physical examination, complete blood cell count with classification, biochemical tests, and PS evaluation. Chest X-rays, chest or abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans, brain CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging, radionuclide bone scans, and any other diagnostic clinically indicated procedures were performed. Tumor response was evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.8 Objective response rate (ORR) was calculated as the ratio of the number of patients who achieved complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) and the total number of patients enrolled. Disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as the percentage of patients who achieved CR, PR, and stable disease (SD). Assessment was conducted at least every two cycles. Safety was evaluated using treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) graded according to National Cancer Institute-Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0). All patients were counseled about the importance of early recognition and treatment of diarrhea. OS was measured as the date of treatment to the date of death or the date of the most recent follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured as the date of treatment to the date of the first observation of disease progression or the date of death from any cause if there had been no progression. After all cycles of treatment, routine follow-up by imaging analysis was performed every two months until the date of death. The last follow-up date was 30 December 2012. Three patients were lost to follow-up; the follow-up rate was 95.2%.

Statistical analysis

This was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, prospective phase II study. The primary objective of the study was to compare PFS associated with the use of IP and EP for the treatment of patients with previously untreated ES-SCLC. Secondary objectives were to compare the antitumor efficacy as assessed by ORR and OS, and to evaluate the safety and tolerability of each regimen. All calculations and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons of analyzed parameters between groups were performed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for proportional variables. Survival data were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariable analysis of the associations between diarrhea and UGT1A1 genotype in the IP arm were assessed with logistic regression. Two sided values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Response and survival

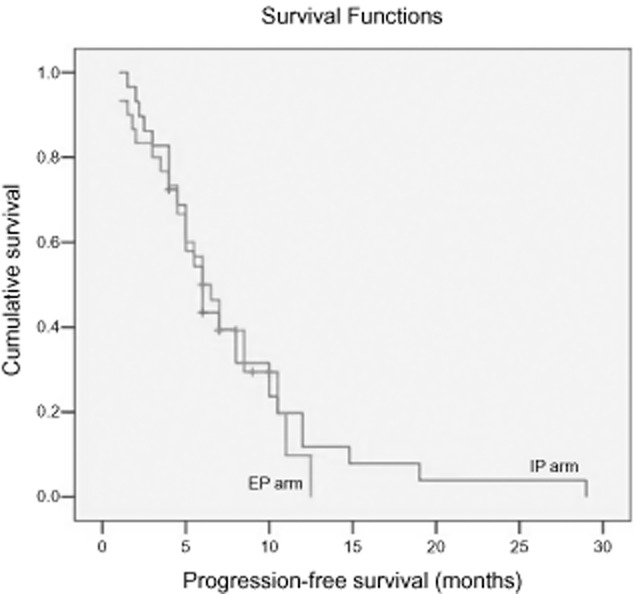

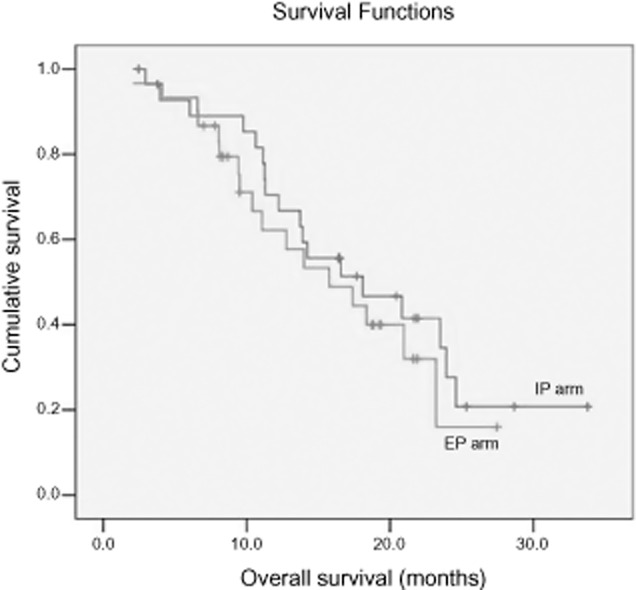

In the IP arm, a total of 128 cycles were administered with an average of 4.3 cycles: one cycle in one patient, two cycles in four, three in two, four in 10, five in five, and six in eight. In the EP arm, a total of 147 cycles were administered with an average of 4.6 cycles: two cycles in four patients, three cycles in zero, four in 14, five in three, and six in 12. There was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.064). ORR was 70% in the IP arm and 65.6% in the EP arm without significant difference (P = 0.056). However, DCR in the IP arm was 83.3%, significantly higher than in the EP arm (71.9%; P = 0.043, Table 2). With a median follow-up of 13.8 months, the median OS for all patients was 16.6 months. There was no statistical difference in PFS (Fig 1) or OS (Fig 2) between the two arms. The median OS and PFS rates in the IP arm were 18.1 and six months, respectively, while in the EP arm the medians were 15.8 and six months, respectively.

Table 2.

Treatment administration and efficacy in both EP and IP arms

| Parameter | IP (n = 30) | EP (n = 32) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycles | 0.064 | ||

| 1 | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | |

| 2 | 4 (13.3%) | 4 (12.5%) | |

| 3 | 2 (6.7%) | 0 | |

| 4 | 10 (33.3%) | 13 (40.6%) | |

| 5 | 5 (16.7%) | 3 (9.4%) | |

| 6 | 8 (26.7%) | 12 (37.5%) | |

| Average cycles | 4.3 | 4.6 | |

| Response | |||

| CR | 2 (6.7%) | 0 | |

| PR | 19 (63.3%) | 21 (65.6%) | |

| SD | 4 (13.3%) | 2 (6.3%) | |

| PD | 5 (16.7%) | 9 (28.1%) | |

| ORR (CR+PR) | 21 (70%) | 21 (65.6%) | 0.056 |

| DCR (CR+PR+SD) | 25 (83.3%) | 23 (71.9%) | 0.043 |

CR, complete response; DCR: disease control rate; EP, etoposide plus cisplatin; IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin; ORR: overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival of patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer treated with irinotecan plus cisplatin (IP) and etoposide plus cisplatin (EP).  , 1 IP;

, 1 IP;  , 2 EP;

, 2 EP;  , 1-censored;

, 1-censored;  , 2-censored.

, 2-censored.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer treated with irinotecan plus cisplatin (IP) and etoposide plus cisplatin (EP).  , 1 IP;

, 1 IP;  , 2 EP;

, 2 EP;  , 1-censored;

, 1-censored;  , 2-censored.

, 2-censored.

Toxicity

The most common adverse effects were hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicities. The incidence of grade 1–4 neutropenia, leukocytopenia, and anemia did not differ significantly between the two groups. In the IP arm, the occurrence of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia was 6.7% and 18.8% (P = 0.035) in the IP and EP arms, respectively. However, grade 3–4 diarrhea was more frequent in the IP than in the EP arm (P = 0.008). The details are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Toxicity and side effects

| Toxicity type | IP (n = 30) | EP (n = 32) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade1-2 | Grade3-4 (%) | Grade1-2 | Grade3-4 (%) | ||

| Neutropenia | 10 | 16 (53.3) | 8 | 23 (71.9) | 0.057 |

| Leukopenia | 13 | 13 (43.3) | 12 | 17 (53.1) | 0.271 |

| Anemia | 18 | 9 (30.0) | 18 | 10 (31.3) | 0.114 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 | 2 (6.7) | 16 | 6 (18.8) | 0.035 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 23 | 4 (13.3) | 23 | 3 (9.4) | 0.237 |

| Diarrhea | 16 | 5 (16.7) | 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0.008 |

| Constipation | 8 | 3 (10.0) | 7 | 3 (9.4) | 0.167 |

| Infection | 5 | 1 (3.3) | 2 | 1 (3.1) | 0.076 |

| Alopecia | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0.107 |

| Fatigue | 24 | 3 (10.0) | 23 | 4 (12.5) | 0.236 |

| Hepatic dysfunction | 12 | 1 (3.3) | 6 | 1 (3.1) | 0.191 |

EP, etoposide plus cisplatin; IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin.

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) polymorphisms

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase is a key enzyme involved in the complex metabolism of irinotecan. UGT1A1*28 is a common allele with seven TA repeats in the promoter of UGT1A1, compared with the wild-type allele which has six repeats. UGT1A1*28 could be classified into three groups: wild-type (TA6/6), heterozygous (TA6/7), and homozygous (TA7/7). Another polymorphism, UGT1A1*6, characterized by replacing a single nucleotide in exon1 of UGT1A1, could be classified into wild-type (GG), heterozygous (GA), and homozygous (AA). According to the frequency of mutation alleles, including both UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28, genotypes could be classified into wild-type, single, and double mutations. Allele frequency was tested to conform to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of UGT1A1 of patients treated with IP (n = 30)

| Genotype | Genotype | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UGT1A1*28 (n) | UGT1A1*6 (n) | ||

| TA6/6 (20) | G/G (21) | Wild-type | 12 (40.0) |

| TA6/6 (20) | A/G (8) | Single mutation | 7 (23.4) |

| TA6/7 (7) | G/G (21) | Singe mutation | 6 (20.0) |

| TA6/7 (7) | A/G (8) | Double mutation | 1 (3.3) |

| TA7/7 (3) | G/G (21) | Double mutation | 3 (10.0) |

| TA6/6 (20) | A/A (1) | Double mutation | 1 (3.3) |

IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin; UGT1A1, uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase.

UGT1A1 polymorphisms and late-onset diarrhea

The incidence of grade 1–4 late-onset diarrhea of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous UGT1A1*28 were 65.0%, 85.7%, and 66.7%, respectively, with statistical difference (P = 0.037). However, the incidence of grade 3–4 late-onset diarrhea was 10.0%, 14.3%, and 66.7% (P = 0.087), respectively. There was no significant difference in UGT1A1*6 allele and the incidence of grade 1–4 or 3–4 late-onset diarrhea. According to the frequency of mutation alleles for both UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*6, the incidence of grade 1–4 late-onset diarrhea of wild-type, single, and double mutation were 66.7%, 76.9%, and 75.0% (P = 0.267), respectively, whereas grade 3-4 were 8.3%, 15.4%, and 50.0% (P = 0.075), respectively. Details are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Relationship between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and late-onset diarrhea of patients treated with IP (n = 30)

| Genotype | n | Late-onset diarrhea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1-4 (%) | P | Grade 3-4 (%) | P | ||

| UGT1A1*28 | 0.037 | 0.087 | |||

| TA6/6 | 20 | 13 (65.0) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| TA6/7 | 7 | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| TA7/7 | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 2 (66.7) | ||

| UGT1A1*6 | 0.348 | 0.083 | |||

| G/G | 21 | 15 (71.4) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| A/G | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | ||

| A/A | 1 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | ||

| UGT1A1*6 and GT1A1*28 | 0.267 | 0.075 | |||

| Wild-type | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Single mutation | 13 | 10 (76.9) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Double mutation | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin; UGT1A1, uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase.

Factors affecting the late-onset diarrhea

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase*28 genotype, ECOG PS, and chemotherapy cycles were the essential factors affecting grade 1–4 late-onset diarrhea in logistic regression analysis. With respect to the UGT1A1 genotype, a significant association was observed between the UGT1A1*28 allele and late-onset diarrhea (hazard ratio 5.48, 95% confidence interval 1.256–9.311; P = 0.028). Patients with an ECOG PS of 2 had a higher risk of late-onset diarrhea than those with a PS of 0-1 (P = 0.003). Meanwhile, a significant association was observed between patients treated with less than four cycles and four or more cycles (P = 0.031). Details are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Multivariable analysis of factors affecting grade 3-4 late-onset diarrhea

| Factors | HR (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| UGT1A1*28 | 5.848 (1.256–9.311) | 0.028 |

| ECOG: 0-1 versus 2 | 8.726 (3.269–30.378) | 0.003 |

| Cycles: < 4 versus ≥ 4 | 3.264 (1.543–8.326) | 0.031 |

CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR, hazard ratio; UGT1A1, uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase.

UGT1A1 polymorphisms and efficacy

None of the genotypes were associated with better efficacy. There was no significant difference among wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous UGT1A1*28 (P = 0.628) or UGT1A1*6. No difference was observed in the mutation allele frequency of UGT1A1*28 and UGT1A1*6 (P = 0.336), as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Relationship between UGT1A1 polymorphisms and efficacy of patients treated with IP (n = 30)

| Genotype | n | RR (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| UGT1A1*28 | 0.628 | ||

| TA6/6 | 20 | 14 (70.0) | |

| TA6/7 | 7 | 5 (71.4) | |

| TA7/7 | 3 | 2 (66.7) | |

| UGT1A1*6 | 0.352 | ||

| G/G | 21 | 14 (66.7) | |

| A/G | 8 | 6 (75.0) | |

| A/A | 1 | 1 (100.0) | |

| UGT1A1*6 and UGT1A1*28 | 0.336 | ||

| Wild-type | 12 | 8 (66.7) | |

| Single mutation | 13 | 10 (76.9) | |

| Double mutation | 4 | 3 (75.0) |

UGT1A1*28: TA6/6, wild-type; TA6/7, heterozygous; TA7/7, homozygous; UGT1A1 *6: GG, wild-type; GA, heterozygous; AA, homozygous. IP, irinotecan plus cisplatin; RR, response rate; UGT1A1, uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase.

Discussion

The current standard chemotherapy for ES-SCLC is an EP or IP regimen. Noda et al. first reported a phase III study (JCOG9511) of an IP compared with an EP regimen in 154 patients with ES-SCLC. During interim analysis, they found significant differences in OS and a toxicity profile in favor of the IP arm and, thus, prematurely closed the study. However, large randomized trials conducted in North America, including the Southwest Oncology Group trial (SWOG S0124) using almost the same eligibility criteria and identical treatment regimens as JCOG9511, did not confirm the JCOG9511 results. Despite several negative trials, two meta-analyses using non-individual patient data showed a significant survival improvement with IP compared with EP in patients with ES-SCLC.9,10

This multicenter, phase II, randomized study did not reveal a statistically significant difference in OS and PFS between the IP and EP regimens; however, the DCR in the IP arm was 83.3%, higher than the EP arm (71.9%; P = 0.043) and similar to JCOG9511 results. Non-hematological adverse events were much the same between the two groups, except the incidence of diarrhea was 70.0% in the IP arm and 15.6% in the EP arm (P = 0.008). However, the IP arm was associated with significantly lower rates of grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia (P = 0.035). Our results are consistent with previous trials, which reported that the IP regimen produced more non-hematological toxicities and less hematological toxicities compared with the EP regimen.4–7

A comparative analysis of response rates and toxicities between the IP arms of JCOG9511 and SWOG S0124 suggests that pharmacogenomic factors may account for differences in the efficacy and toxicities seen in the two trials.7 In the IP arms, the incidence of grade 3–4 neutropenia was 65% in the JCOG 9511 trial and 34% in the SWOG S0124 trial (P < 0.001). Many studies have indicated that SN38 glucuronidation activity and irinotecan-induced toxicity are associated with UGT1A1*28, which generates a repeat polymorphism in the TATA box promoter of UGT1A1, demonstrating a lower allele frequency in Asians compared with Caucasians.11 There is fairly strong evidence that individuals with the homozygote UGT1A1*28 genotype tend to have a higher prevalence of irinotecan-induced neutropenia.12–14 Ferraldeschi et al. observed an association between the UGT1A1*28 genotype and diarrhea; however, other studies have reported no statistically significant association.15–17 A meta-analysis reported that patients carrying UGT1A1*28 alleles are at an increased risk of severe diarrhea, and this increased risk is only apparent in those who are administered medium or high doses of irinotecan.18 Moreover, there was a significant linear correlation between irinotecan doses and related odds ratios (ORs) of severe diarrhea; however, this association was only observed when comparing the risk of diarrhea between patients with a homozygous UGT1A1*28 genotype and those carrying wild-type alleles.18 In the present study, the incidence of grade 1–4 diarrhea was related to UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms (P = 0.037); however the relationship of the severe diarrhea (grade 3–4) and UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms was not observed.

Another genotype, UGT1A1*6, characterized by replacing a single nucleotide in exon1 of UGT1A1, has been considered to be related to reduced SN38 glucuronidation activity and bears a higher allele frequency in Asians compared with Caucasians.17,19 Moreover, grade 3–4 neutropenia is significantly more frequent in patients who have the UGT1A1*6 genotype, and the homozygosity for the UGT1A1*6 is associated with an increased risk of severe neutropenia in Asians.20 In a meta-analysis of Asian patients, UGT1A1*6 polymorphisms increased the incidence of severe neutropenia in high/medium and low doses of irinotecan.21 For severe diarrhea, the heterozygous variant of UGT1A1*6 showed no significant risk, while the homozygous variant indicated a notable risk.21 However, our data did not support this theory, most likely because the sample of UGT1A1*6 cases in this study was too small.

In 2005, UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms were taken into consideration by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as predictors for evaluating the risk of irinotecan-induced toxicity. However, a reduction in dosage might also be associated with reduced tumor response and/or increased morbidity.22 In 2009, the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention Working Group reported that routine UGT1A1 genotyping for guiding irinotecan dosing is not recommended.23 Definitive evidence of whether the UGT1A1*28 genotype is associated with clinical outcomes of irinotecan-based chemotherapy is not yet available to assist in a clinical setting. As for the correlation between efficacy and the UGT1A1 genotype, we did not observe a significant difference in our study. Our result was consistent with Liu et al.’s meta-analysis, in which no association between UGT1A1*28 genotypes and IP response was found.24 However, the UGT1A1*28 allele showed significant or marginal association with poorer OS, especially in the low dose irinotecan subgroup of the homozygous model. Furthermore, the irinotecan dose also did not impact upon therapeutic response or PFS according to UGT1A1 genotype.25

In conclusion, the present study failed to show a significant superiority in efficacy for the IP regimen compared with the standard of care EP for ES-SCLC. The UGT1A1 genotype has an influence on late-onset diarrhea, but there was no evidence of UGT1A1 having an impact on the efficacy of the IP regimen for SCLC. Phase III clinical trials are urgently required.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2014BAI09B01). Zhou Tao performed statistical analysis (Medical Department of Pfizer).

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Zeng HM, Zou XN. The incidences and mortalities of major cancers in China, 2010. Chin J Cancer. 2014;33:402–405. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddadin S, Perry MC. History of small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AM, Lara PN, Lau DH, Gandara DR. Treatment of extensive small cell lung cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;8:373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:85–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna N, Bunn PA, Jr, Langer C, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2038–2043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara PN, Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: Clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2530–2535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara PN, Jr, Chansky K, Shibata T, et al. Common arm comparative outcomes analysis of phase 3 trials of cisplatin + irinotecan versus cisplatin + etoposide in extensive stage small cell lung cancer: Final patient-level results from Japan Clinical Oncology Group 9511 and Southwest Oncology Group 0124. Cancer. 2010;116:5710–5715. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing irinotecan/platinum with etoposide/platinum in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:867–873. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3181d95c87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima JP, dos Santos LV, Sasse EC, Lima CS, Sasse AD. Camptothecins compared with etoposide in combination with platinum analog in extensive stage small cell lung cancer: Systematic review with meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1986–1993. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f2451c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Chida M, Nakayama K, Saka H, Kamataki T. The UGT1A1* 28 allele is relatively rare in a Japanese population. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:357–360. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199808000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins JM, Goldberg RM, Qu P, Ibrahim JG, McLeod HL. UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan-induced neutropenia: Dose matters. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1290–1295. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Chen PM, Chiou TJ, et al. UGT1A1*28 polymorphism predicts irinotecan-induced severe toxicities without affecting treatment outcome and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112:1932–1940. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweekel DM, Gelderblom H, Van der Straaten T, et al. UGT1A1*28 genotype and irinotecan dosage in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group study. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:275–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraldeschi R, Minchell LJ, Roberts SA, et al. UGT1A1*28 genotype predicts gastrointestinal toxicity in patients treated with intermediate-dose irinotecan. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:733–739. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Lim HS, Park YH, Lee SY, Lee JS. Integrated pharmacogenetic prediction of irinotecan pharmacokinetics and toxicity in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;63:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Lim HS, Shin ES, et al. Comprehensive analysis of UGT1A polymorphisms predictive for pharmacokinetics and treatment outcome in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with irinotecan and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2237–2244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu ZY, Yu Q, Zhao YS. Dose-dependent association between UGT1A1*28 polymorphism and irinotecan-induced diarrhoea: A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1856–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Bock KW, Burchell B, et al. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:677–685. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173483.13689.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jada SR, Lim R, Wong CI, et al. Role of UGT1A1*6, UGT1A1*28 and ABCG2 c.421C4A polymorphisms in irinotecan-induced neutropenia in Asian cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1461–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Li M, Hu J, et al. UGT1A1*6 polymorphisms are correlated with irinotecan-induced toxicity: A system review and meta-analysis in Asians. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomaki GE, Bradley LA, Douglas MP, Kolor K, Dotson WD. Can UGT1A1 genotyping reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with irinotecan? An evidence-based review. Genet Med. 2009;11:21–34. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818efd77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AO, Armstrong K, Botkin J, et al. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: Can UGT1A1 genotyping reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with irinotecan? Genet Med. 2009;11:15–20. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818efd9d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cheng D, Kuang Q, Liu G, Xu W. Association between UGT1A1*28 polymorphisms and clinical outcomes of irinotecan-based chemotherapies in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis in Caucasians. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias MM, Pignon JP, Karapetis CS, et al. The effect of the UGT1A1*28 allele on survival after irinotecan-based chemotherapy: A collaborative meta-analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;14:424–431. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]