Abstract

Objectives

This analysis of screening and baseline data from an ongoing trial examined self-report versus automated adherence monitoring and assessed the relationship between bipolar disorder (BD) symptoms and adherence in 104 poorly adherent individuals.

Methods

Adherence was measured with the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) and the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS). Symptoms were measured with the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

Results

Mean age of the sample was 46.3 years [standard deviation (SD) = 9.41], with 72% (n = 75) women and 71% (n = 74) African American subjects. Adherence improved from screening to baseline with a mean missed drug proportion measured by TRQ of 61.43% (SD = 26.48) versus baseline mean of 46.61% (SD = 30.55). Mean proportion of missed medication using MEMS at baseline was 66.43% (SD = 30.40). Correlation between TRQ and MEMS was 0.47. Correlation between a single index drug and all BD medications was 0.95. Symptoms were generally positively correlated with TRQ (worse adherence = more severe symptoms), but in most instances was only at a trend level (p > 0.05) with the exception of correlation between baseline TRQ and MADRS and BPRS, which were positive (r = 0.20 and r = 0.21, respectively) and significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Conclusions

In patients with BD, monitoring increased adherence by 15%. MEMS identified 20% more non-adherence than self-report. Using a standard procedure to identify a single index drug for adherence monitoring may be one way to assess global adherence in patients with BD receiving polypharmacy treatment. Greater BD symptom severity may be a clinical indicator to assess for adherence problems.

Keywords: adherence, bipolar disorder, compliance, depression, mania, mood stabilizer

Guidelines on illness management for individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) recommend mood stabilizing medication (1–4). However, approximately one in two individuals with BD is non-adherent with medication for BD (5–8), nine out of every 10 individuals with BD has seriously considered medication withdrawal, and at least a third of individuals fail to take more than 70% of their prescribed medication (9, 10). BD medication non-adherence can have severe consequences (11–17) that impose personal and financial burden (18–20). For example, Gonzalez-Pinto et al. (21) reported a 5.2-fold increased suicide rate in patients with BD with poor adherence compared to adherent patients with BD (21).

A major challenge to being able to minimize the effects of poor adherence is identifying individuals with suboptimal adherence (22) so that adherence enhancement approaches can be implemented. Treatment plans that are premised upon apparent treatment resistance when poor adherence might actually explain poor outcome can be expected to lead to high-dose drug regimens and drug-related complications. Some subgroups of individuals with BD, such as minorities, are at particularly high risk for non-adherence (23), but clinicians may not readily recognize those who do not take prescribed medications, particularly when adherence is partial rather than complete.

For some BD medications such as lithium and anticonvulsants, objective biological measures such as serum levels can help clinicians evaluate poor adherence. However, in real-world settings, biomarkers may be less practical given the wide range in serum targets and variability in individual metabolism of BD drugs. There are no clear biomarker targets for antipsychotic drugs, a major therapeutic class for BD.

Given the higher likelihood of poor outcomes in BD non-adherence, it seems reasonable to presume that patients with BD who are non-adherent would have severe BD symptoms that precede relapse or other negative consequence of uncontrolled illness. A number of studies have assessed BD symptom correlates of adherence (24–28) but few of these reports have specifically focused on the highest risk subgroups of non-adherent patients with BD in a prospective fashion. Studies that are based on administrative data or electronic medical record review may include pharmacy data that identifies poor adherence but these types of analysis typically do not provide standardized symptom severity, while traditional clinical trials often only recruit patients who are known to be reliable and adherent.

This analysis, derived from baseline data collected from an ongoing National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing a novel behavioral intervention to promote medication adherence, examined the relationship between BD symptom severity and adherence. This well-characterized, poorly adherent BD sample was assessed on both self-reported and objectively measured medication adherence measures as well as standardized ratings of depression, mania and global psychopathology. Given the wide prevalence of poor adherence in BD, clarification of symptom expression as it relates to differential medication adherence could potentially inform clinical care for high-risk patients with BD.

Methods and measures

Overall study description

The NIMH-funded RCT from which these analyses are derived is testing a novel customized adherence enhancement (CAE) intervention intended to promote BD medication adherence versus an educational control (EDU) in poorly adherent individuals with BD (1R01MH093321-01A1; Principal Investigator MS). The EDU control provides similar therapist time and attention as CAE, but without a specific and personalized focus on adherence. Participants are randomized at baseline on a 1:1 basis to receive either CAE or EDU. All study participants were followed for a six-month period. Study inclusion criteria were having either bipolar I disorder (BD-I) or bipolar II disorder (BD-II) as confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (29) BD for at least two years duration, treatment with at least one evidence-based medication to stabilize mood for at least six months, and ≥ 20% non-adherent with prescribed BD medication treatment (i.e., lithium, anticonvulsant, or antipsychotic mood stabilizer). Study inclusion criteria are purposely broad in order to generalize to real-world patients with BD and only individuals who are unable to participate in study procedures, unable/unwilling to provide informed consent, and those at immediate risk of harm to self or others are excluded. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Medication adherence

Adherence was measured with both a self-reported instrument, the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) and with technology-facilitated medication monitoring, the Medication Event Monitoring System [(MEMS®) Aprex Corp., Fremont, CA, USA].

TRQ

TRQ is a self-report measure which identifies the proportion of missed medication in the past seven and past 30 days (30, 31). Lower scores represent better adherence, while higher score represent worse adherence. TRQ has demonstrated a statistically significant association with past non-adherence, non-adherence in the past month, and non-adherence in the past week and has been shown to correlate highly with lithium levels (10). In this RCT, TRQ is assessed for each evidence-based BD maintenance medication (lithium, anticonvulsant, antipsychotic) prescribed for ≥ 3 months. For individuals who are on more than one medication, an average TRQ is calculated. For this analysis we only used past seven day TRQ as it could be readily compared to past week adherence using the automated adherence assessment measure.

MEMS

Study participants used MEMS caps for their pill bottles, which record the time and date of bottle opening. Participants were given the MEMS cap at study screening visit if they appeared to fit inclusion/exclusion criteria and asked to use the MEMS cap for the BD medication that the patient takes the most frequently (BD index drug). In the case of multiple BD medications taken at same frequency, the medication that was started most recently was selected. The rationale for index BD drug selection was thus based upon frequency (more frequent dosing may worsen adherence) and duration that the individual had been prescribed BD drug (individual may have less opportunity to establish adherence habits with more recently prescribed drugs). MEMS data were collected at the baseline visit based upon pill-taking behavior during the one- to two-week interval between screening and baseline visit. To standardize comparison with the TRQ, MEMS pill-taking behavior over the seven days leading up to the baseline visit was assessed. In addition, MEMS scores were calculated based on the TRQ criterion (proportion of missed drug). In cases where at least one dose of medication was missed in a given day, the day was counted as non-adherent, regardless of how many other doses were actually taken that day.

BD symptoms

Symptoms were measured with the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (32), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (33), and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (34).

Comorbidity

Presence of alcohol and drug problems was assessed with the alcohol and drug portions of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (35, 36). On the ASI, the need for treatment for alcohol or drug treatment is scored on a 1–9 continuum with a score of ‘0’ indicating no problem with alcohol or drugs and a score of ‘9’ being the most extreme problem with treatment being absolutely necessary. Medical comorbidity was assessed with the self-reported Charlson Comorbidity Index (37) which identifies major medical disorders by organ or functional system. Higher scores on the Charlson indicate more substantial medical morbidity.

Drug attitudes

The 10-item Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI), used to measure attitudes towards medication (38), is known to be relatively unaffected by psychiatric symptom severity (39). The DAI was originally developed to assess the attitudes and subjective experience of patients with schizophrenia being treated with antipsychotic medications. However, the scale has been widely utilized with other seriously mentally ill populations receiving psychotropic medication (40). The DAI is a simple, true-false format questionnaire that assesses domains of patient’s attitudes including positive and negative experience, locus of control, and attitudes towards health. Responses are scored on a euphoric–dysphoric continuum (alpha = 0.93).

Data analysis

This analysis used screening (TRQ) and baseline (TRQ, MEMS, and demographic and clinical information) data from the first 104 consecutive RCT enrollments. First, demographic and clinical information was summarized using descriptive analyses, including the distribution of TRQ scores at screening and baseline and MEMS at baseline. The MEMS data were only available at baseline as individuals first received the MEMS at screening. Correlation between baseline MEMS and TRQ was computed for the index BD drug (drug used for MEMS assessment). We also examined possible demographic (age, gender, ethnicity, education) and clinical (YMRS, BPRS, MADRS, DAI, ASI, Charlson) correlates of discrepant TRQ and MEMS scores. More specifically, the difference between baseline TRQ and MEMS index drug scores were computed, and correlated with clinical and demographic variables. For gender and ethnicity, two-sample comparisons of difference values were conducted, with ethnicity being white versus other ethnicity.

The association between screening and baseline TRQ and symptoms (MADRS, YMRS, and BPRS) and the association between baseline MEMS and symptoms were assessed. Study participants were grouped according to non-adherence levels (most, medium, and least adherent), and symptom measures were compared across these groups, using Mann–Whitney U-tests. Finally, to further drill down into categories of psychiatric symptoms we assessed the association between TRQ (screening and baseline) and MEMS in relation to the five factors of the BPRS as summarized by other research groups (41).

Results

Overall sample description

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics in this sample of 104 poorly adherent patients with BD. Mean age of the sample was 46.3 years [standard deviation (SD) = 9.41], with 72% (n = 75) women, 71% (n = 74) African American, and 3% (n = 3) Hispanic subjects. The majority (66%, n = 69) had BD-I, with mean age of onset 21 (SD = 10.11) years. Individuals had a mean of 12.3 (SD = 2.28) years of education and a mean lifetime history of 5.34 (SD = 8.60) psychiatric hospitalizations. Self-reported substance use problems and medical comorbidity were mild to minimal.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 104 poorly adherent patients with bipolar disorder enrolled in an adherence intervention study

| Variables | Mean (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.31 (9.41) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 29 (28) | |

| Female | 75 (72) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 74 (71) | |

| Caucasian | 28 (27) | |

| Asian | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 1 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (3) | |

| Education, years | 12.25 (2.28) | |

| BD diagnostic type | ||

| BD-I | 69 (66)f | |

| BD-II | 23 (22)f | |

| Mean age of BD onset, years | 21.05 (10.11) | |

| Mean no. of previous hospitalizations | 5.28 (8.60) | |

| TRQa at study screen | 61.43 (26.48) | |

| TRQ at baseline | 46.61 (30.55) | |

| MEMS at baseline | 66.43 (30.40) | |

| BPRS at baseline | 37.61 (10.72) | |

| MADRS at baseline | 18.23 (8.98) | |

| YMRS at baseline | 7.60 (5.10) | |

| ASI alcoholb | 1.58 (2.43) | |

| ASI drugc | 1.92 (2.43) | |

| Charlson Indexd | 0.30 (0.95) | |

| DAIe | 6.68 (1.67) |

SD = standard deviation; BD = bipolar disorder; BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder; TRQ = Tablets Routine Questionnaire; MEMS = Medication Event Monitoring System; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; MADRS = Montgomery–Åsberg Rating Scale; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; ASI alcohol = Addiction Severity Index item D32; ASI drugs = Addiction Severity Index item D33; DAI = Drug Attitudes Inventory.

Higher scores indicate worse adherence.

Need for treatment of alcohol abuse (higher scores indicate more need for treatment).

Need for treatment of drug abuse (higher scores indicate more need for treatment).

Self-reported medical comorbidity (higher scores indicate more medical comorbidity).

Higher scores indicate better attitudes towards medication.

n = 12; missing data on this item.

Treatment adherence

While there was substantial variability in adherence with rates of non-adherence between 20 and 100%, the mean proportion of days with missed doses of prescribed BD medications by TRQ at screening was 61.43% (SD = 26.48). Proportion of missed medication improved from screening to baseline with a mean baseline TRQ of 46.61% (SD = 30.55). The mean proportion of missed prescribed index BD medication changed from TRQ screening value of 62.38% (SD = 27.46) to baseline of 47.43% (SD = 32.45). Mean proportion of missed drug on MEMS was 66.43% (SD = 30.40).

Table 2 shows correlations between baseline TRQ for all BD drugs (average of all maintenance BD drugs prescribed), baseline TRQ for BD index drug and baseline MEMS for BD index drug. The TRQ and MEMS scores were relatively well correlated although MEMS identified a greater proportion of missed drug (approximately 20% more) compared to TRQ. Average TRQ for all BD drugs was highly correlated (0.951) with TRQ for index BD drug. Given the very tight correlation between index BD drug and average of all drugs, our subsequent adherence results focus on adherence measures (TRQ and MEMS) of index BD drug.

Table 2.

Correlation between TRQ and MEMS scores in non-adherent patients with bipolar disorder

| Item | TRQ baseline all drugs (average) |

TRQ baseline index drug |

MEMS baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRQ baseline all drugs (average) | 1.000 | 0.951a | 0.465a |

| TRQ baseline index drug | 0.951a | 1.000 | 0.423a |

| MEMS baseline | 0.465a | 0.423a | 1.000 |

TRQ = Tablets Routine Questionnaire; MEMS= Medication Event Monitoring System.

p < 0.01.

The mean difference in TRQ and MEMS for the index BD drug was −20.39 (SD = 33.40), consistent with the previously noted observation that MEMS identified worse adherence on average than TRQ. Spearman correlations were computed between the difference in TRQ and MEMS with clinical and demographic variables. Significant correlations were found with Charlson index: 0.282 (p = 0.011, n = 81), with D32 (ASI alcohol abuse): 0.351 (p = 0.001, n = 80), and with D33 (ASI drug abuse): 0.389 (p < 0.001, n = 80). Other correlations were not significant including no significant differences in the mean discrepancies by gender or ethnicity.

Symptom severity

To evaluate the relationship between symptoms and adherence, the BD index drug TRQ at screening and baseline was assessed in relation to total scores on all three standardized symptom severity measures. The MADRS, BPRS, and YMRS were generally positively correlated with TRQ (worse adherence corresponding to more severe symptoms), but, in most instances, the association did not reach statistical significance. The direction of the correlation between baseline TRQ and YMRS was positive, but also not statistically significant. Correlation between the screening TRQ and BPRS approached significance (p = 0.09). However, correlation between baseline TRQ and MADRS at baseline was significant (r = 0.20, p = 0.05) as was correlation between baseline TRQ and BPRS at baseline (r = .21, p < 0.05). As an additional check, Spearman correlations between the TRQ and symptom severity measures were examined. Results of the Spearman correlations were generally similar to the Pearson correlations and did not suggest any differences in identifying correlations of significance.

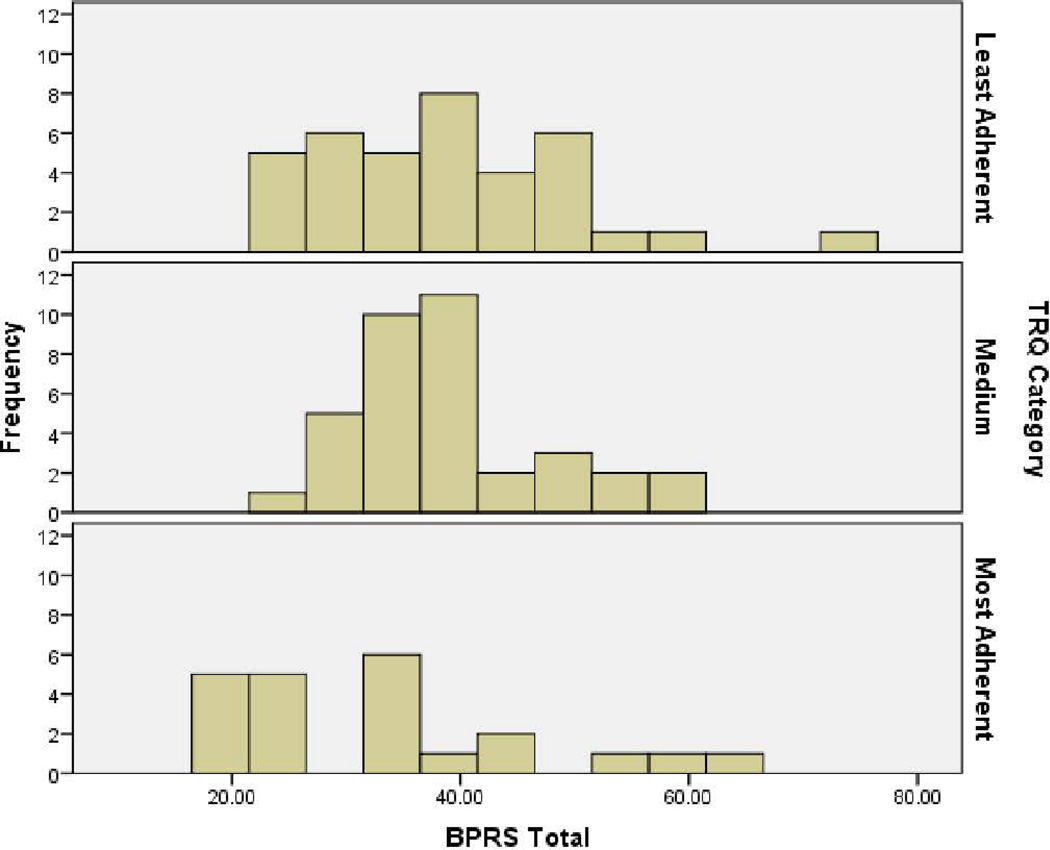

We also considered formalized hypothesis tests of differences in symptom measures by adherence level categories. Based on baseline TRQ values (% non-adherence), participants were placed into either the most, medium, or least adherent group. Cutoff values for these groups were by TRQ score: ≤ 20% missed drug (most adherent), 21–50% missed drug (medium adherence), and ≥ 51% missed drug (least adherent). The relationship between TRQ and BPRS was then examined in terms of these TRQ-based adherence categories (Fig. 1). Non-parametric tests were significant. The distribution of scores on the BPRS was not the same across adherence categories (p < 0.05). Median scores on the BPRS were respectively 33, 37, and 37 for the most, medium, and least adherent groups (higher BPRS scores indicate greater symptom severity). The relationship between TRQ and MADRS also was examined, and distribution of MADRS scores was also not the same across adherence categories (p < 0.05). Median scores on the MADRS were respectively 14, 18, and 19 for the most, medium, and least adherent groups. The same analysis between TRQ and YMRS did not yield any significant differences across categories.

Fig. 1.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) severity in individuals most, medium, and least adherent as assessed by the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ). Higher BPRS scores indicate greater symptom severity. TRQ at baseline (more missed drug = greater non-adherence). Most = ≤ 20% missed drug; medium = 21–50% missed drug; least = ≥ 51% missed drug. Independent samples Kruskall–Wallis test p = 0.043.

Similar analyses were conducted using MEMS to further evaluate the relationship between symptom expression and treatment adherence. MEMS at baseline was assessed in relation to total scores on all three standardized symptom severity measures. BPRS and YMRS did not demonstrate significant correlation with MEMS. MADRS and MEMS, however, were significantly correlated (r = 0.266, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). MEMS-based categories of non-adherence level were generated in the same manner as for TRQ. Analogous non-parametric tests were significant. The relationship between MADRS and MEMS was examined in terms of MEMS adherence categories (most, medium, and least). The distribution of MADRS scores was not the same across TRQ categories (p < 0.05). Median scores on the MADRS were respectively 12.0, 17.5, and 19.0 in individuals who were most, medium, and least adherent (higher MADRS scores indicate greater symptom severity).

Fig. 2.

Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) severity in individuals most, medium, and least adherent as assessed by the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS). Higher MADRS scores indicate greater symptom severity. MEMS at baseline (more missed drug = greater non-adherence). Most = ≤ 20% missed drug; medium = 21–50% missed drug; least = ≥ 51% missed drug. Independent samples Kruskall–Wallis test p = 0.028.

To provide additional clinical context for the adherence categories described above (least, middle and most adherent) we assessed demographic descriptive variables as well as comorbidity and drug attitudes. These variables are illustrated in Table 3. Beyond the relationship of symptoms and adherence as noted previously, only education was significantly different (lowest education in the least adherent patients) and clinically relevant. Comorbidity was highest in the mid-level adherence group, but given the generally low levels of self-reported medical comorbidity overall this may have limited clinical relevance.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder with differing levels of adherence as defined by the TRQa

| Variables | Most adherentb | Middle adherentc | Least adherentd | Statistics | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 45.92 ± 10.41 | 47.74 ± 8.92 | 45.44 ± 9.39 | F2,102 = 0.63 | 0.53 |

| Gender, n (%) | χ2 = 2.17, df = 2 | 0.34 | |||

| Male | 9 (8.57) | 10 (9.52) | 9 (8.57) | ||

| Female | 34 (32.38) | 28 (26.67) | 15 (14.29) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%)e | |||||

| African American | 29 (27.62) | 26 (24.76) | 16 (15.24) | ||

| Caucasian | 10 (9.52) | 8 (7.62) | 4 (3.81) | ||

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Mixed/Other | 3 (2.86) | 4 (3.81) | 5 (4.76) | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (0.95) | 1 (0.95) | 1 (0.95) | ||

| Education, years, mean ± SD | 11.92 ± 1.89 | 13.15 ± 2.49 | 11.67 ± 2.07 | F2,100 = 4.83 | 0.01 |

| BD diagnostic type, n (%)f | |||||

| BD-I | 34 (32.38) | 25 (23.81) | 14 (13.33) | χ2 = 3.36, df = 2 | 0.19 |

| BD-II | 6 (5.71) | 10 (9.52) | 6 (5.71) | χ2 = 2.32, df = 2 | 0.31 |

| Age of BD onset, years, mean ± SD | 22.33 ± 10.70 | 22.69 ± 11.34 | 19.58 ± 9.04 | F2,100 = 1.05 | 0.35 |

| No. of previous hospitalizations, mean ± SD | |||||

| Psychiatric | 5.29 ± 10.03 | 4.08 ± 5.21 | 5.45 ± 8.94 | F2,100 = 0.31 | 0.73 |

| Substance abuse | 1.71 ± 2.39 | 1.68 ± 3.37 | 1.88 ± 3.60 | F2,101 = 0.05 | 0.09 |

| MEMS baseline, mean ± SD | 45.86 ± 30.70 | 66.41 ± 32.92 | 78.97 ± 20.43 | F2,78 = 7.93 | 0.001 |

| BPRS baseline, mean ± SD | 33.30 ± 12.79 | 38.73 ± 8.20 | 38.73 ± 10.95 | F2,97 = 2.36 | 0.10 |

| MADRS baseline, mean ± SD | 13.63 ± 83.80 | 19.29 ± 9.13 | 19.63 ± 8.27 | F2,102 = 4.27 | 0.02 |

| YMRS baseline, mean ± SD | 7.74 ± 6.57 | 6.77 ± 3.74 | 8.13 ± 5.12 | F2,95 = 0.69 | 0.50 |

| ASI alcoholg, mean ± SD | 1.46 ± 2.62 | 1.39 ± 2.38 | 1.71 ± 2.35 | F2,63 = 1.75 | 0.18 |

| ASI drugsh, mean ± SD | 1.13 ± 1.45 | 1.63 ± 2.41 | 2.55 ± 2.69 | F2,63 = 2.98 | 0.06 |

| Charlson Indexi, mean ± SD | 0 ± 0 | 0.71 ± 1.41 | 0.12 ± 0.54 | F2,102 = 5.92 | 0.004 |

| DAIj, mean ± SD | 6.83 ± 1.27 | 6.63 ± 1.67 | 6.57 ± 1.88 | F2,101 = 0.19 | 0.83 |

TRQ = Tablets Routine Questionnaire; SD = standard deviation; BD = bipolar disorder; BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder; MEMS = Medication Event Monitoring System; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; MADRS = Montgomery–Åsberg Rating Scale; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; ASI alcohol = Addiction Severity Index item D32; ASI drugs = Addiction Severity Index item D33; Charlson Index = self-reported medical comorbidity; DAI = Drug Attitudes Inventory.

Higher scores indicate worse adherence.

≤ 20% non-adherent.

21–50% non-adherent.

≥ 51% non-adherent.

Cell samples too small to calculate chi-square statistic.

n = out of 95 samples.

Need for treatment of alcohol abuse (higher scores indicate more need for treatment).

Need for treatment of drug abuse (higher scores indicate more need for treatment).

Higher scores indicate more medical comorbidity.

Higher scores indicate better attitudes towards medication.

Finally, to gain further insight into the specific types of symptoms that may be associated with poor adherence, the five BPRS factors (41) of anxiety depression, hostile suspiciousness, thought disturbance, anergia and activation were evaluated in relation to TRQ. At screening, correlation between TRQ and the hostile suspiciousness and the thought disturbance factors of the BRPS approached significance (p = 0.06 and 0.07, respectively). At baseline, correlation between TRQ and the BPRS factor of anxiety depression also approached significance (p = 0.06).

Discussion

In this well-characterized sample of poorly adherent patients with BD, rates of missed drug varied substantially. With respect to measuring medication adherence in BD using the TRQ, a self-reported measure of adherence vs. MEMS, an automated pill monitoring system, there are several key points suggested by this analysis. First, TRQ and MEMS are reasonably well correlated (0.423–0.465), and both in general are positively correlated with BD symptoms (higher rates of missed drug are correlated with higher levels of symptoms). Second, as has been noted by others (42), the act of monitoring adherence can increase adherence. In this sample, adherence increased by approximately 15% within the first two weeks of adherence monitoring using the TRQ. Using a pill-monitoring device like MEMS requires buy-in, instruction in use, and participation by the individuals using them. Thus it may be difficult to determine a true base rate of non-adherence using MEMS, especially in subgroups of people with BD who are known to be poorly adherent as was this case with individuals enrolled in this study. Third, MEMS may be a more sensitive measure of non-adherence as MEMS identified an adherence rate that was approximately 20% worse than self-report. Other researchers have also noted that electronic monitoring appears to identify more missed drug/non-adherent behavior than self-report (22). Fourth, our method of identifying an index BD drug adherence based upon dosing frequency and most recent start-date appeared very tightly correlated with overall/average BD drug adherence. How to best measure medication adherence in BD, where use of multiple drugs is the norm has yet to be definitely determined (43). An advantage of identifying an index/single drug to track for adherence, as was done in this study, allows for comparison with automated pill monitoring using MEMS.

With respect to the relationship between BD symptoms and adherence, our analysis suggests that more severe symptoms occur in people with worse adherence. It has been previously noted that manic symptoms may make it more likely for individuals to be non-adherent (44). Poor adherence in manic patients can occur due to lack of insight, distractibility or lack of routines as well as desire to prolong or maintain euphoria or a sense of well-being. An important limitation to any interpretation between manic symptoms and adherence in our sample is the fact that individuals in our sample had relatively few manic symptoms (mean YMRS score < 8). So, while we did not find a correlation between manic severity and adherence it is possible that our findings would have been different if our sample had been more symptomatic for mania.

In contrast to our findings with manic symptoms, more severe depressive symptoms were associated with worse adherence. Our study methodology did not permit a causal inference for poor adherence in bipolar depression, but other investigators have noted that cognitive impairment that facilitates ‘forgetting’ can impede adherence (22). While motivation and other attitudinal factors can clearly have an impact on adherence (22) it is also possible that individuals with BD may have particular difficulty remembering to take medications at required frequency due to the neurocognitive effects of bipolar depression. Some of the BPRS factor analysis trends for correlation with adherence were consistent with symptom expression that might be seen in individuals with depression, but findings did not quite reach significance, possibly because our study participants all had relatively low BPRS scores to begin with and sample size is not large. Still, these findings give an indication of how correlation arises for overall BPRS score and TRQ.

Given the wide prevalence and destructive effects of medication non-adherence in BD, the relationship between bipolar depressive severity and poor medication adherence has clinical relevance. Excellent recent reviews of treatments for bipolar depression (45, 46) have addressed both the burden of bipolar depression as well as the relative paucity of available treatments. As depression often outlasts and overshadows manic episodes over the life of an individual with BD, it is critical that knowledge on how best to assess and manage bipolar depression continues to advance. Our findings suggest that an important consideration in the assessment of an individual with bipolar depression should be treatment adherence, particularly in the case of more severe depressive episodes. Care approaches that monitor and potentially enhance adherence can improve outcomes for these individuals (22, 47–49).

There were a number of potential limitations to our analysis including the primarily cross-sectional design, moderate sample size, low levels of manic and psychotic symptoms among enrolled BD participants, reliance on self-report for comorbidity variables, and the fact that the most poorly adherent patients are unlikely to volunteer to participate in a research study. However, this study explicitly enrolled patients with BD with poor adherence, a group that is of substantial clinical importance due to their high risk of relapse and poor prognosis. Study findings may thus facilitate gaining information that might not be obtained in a typical therapeutic clinical trial where such individuals might be typically excluded.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the proportion of prescribed medication that an individual with BD actually takes can vary widely. Both self-report and automated medication monitoring are reasonable methods of evaluating adherence although automated methods are likely to provide a more sensitive assessment of missed drug. Monitoring adherence may improve adherence (at least temporarily) and individuals with more severe bipolar depression may be particularly likely to be non-adherent. Selecting an index drug for adherence assessment may be a practical work-around for adherence assessment in the context of polypharmacy. Additional investigation into how clinicians can identify patients with BD who are at high risk for poor medication adherence are needed to help inform interventions that can optimize adherence.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant NIMH 1R01MH093321-01A1 (Principal Investigator: MS) and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSC) - UL1TR 00043for REDCap.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors of this paper do not have any commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with this manuscript.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision) Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(Suppl. 4):1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keck P, Jr, Perlis R, Otto M, et al. The Expert Consensus Guidelines: Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2004. Postgraduate Medicine Report: Special Report. 2004 Dec;:1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin GM, Young AH. The British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines for treatment of bipolar disorder: a summary. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(Suppl. 4):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O'Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversies. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(Suppl. 3):5–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, Ganoczy D, Ignacio RV. Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:232–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, Ganoczy D, Ignacio R. Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:855–863. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:164–172. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1r084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Kaczynski R, Kozma L. Medication non-adherence in bipolar disorder: A patient-centered review of research findings. Clin Approach Bipolar Disord. 2004;3:56–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamison KR, Gerner RH, Goodwin FK. Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium: relationship to compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:866–869. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780080040011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott J, Pope M. Self-reported adherence to treatment with mood stabilizers, plasma levels, and psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1927–1929. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Muser-Causemann B, Volk J. Suicides and parasuicides in a high-risk patient group on and off lithium long-term medication. J Affect Disord. 1992;25:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90084-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mander AJ, Loudon JB. Rapid recurrence of mania following abrupt discontinuation of lithium. Lancet. 1988;2:15–17. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mander AJ. Use of lithium and early relapse in manic-depressive illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78:198–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, et al. Twelve-month outcome after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tohen M, Greil W, Calabrese JR, et al. Olanzapine versus lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a 12-month, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1281–1290. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK. Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott J. Predicting medication non-adherence in severe affective disorders. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2000;12:128–130. doi: 10.1017/S0924270800035584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begley CE, Annegers JF, Swann AC, et al. The lifetime cost of bipolar disorder in the US. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:483–495. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrenberger S, Rogers T, Walker R, de Leon J. Economic grand rounds: the high costs of care for four patients with mania who were not compliant with treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1539–1542. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.12.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colom F, Vieta E, Tacchi M, Sánchez-Moreno J, Scott J. Identifying and improving non-adherence in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(Suppl. 5):24–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Pinto A, Mosquera F, Alonso M, et al. Suicidal risk in bipolar I disorder patients and adherence to long-term lithium treatment. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Depp CA, Moore DJ, Patterson TL, Lebowitz BD, Jeste DV. Psychosocial interventions and medication adherence in bipolar disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:239–250. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.2/cadepp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Good CB, Fine MJ, Bauer MS, Kilbourne AM. Therapeutic alliance perceptions and medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;107:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin JB, Tatsuoka C, Cassidy KA, Aebi ME, Sajatovic M. Trajectories of medication attitudes and adherence behavior change in non-adherent bipolar patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sylvia LG, Reilly-Harrington NA, Leon AC, et al. Medication adherence in a comparative effectiveness trial for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129:359–365. doi: 10.1111/acps.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Amann BL, AMA N, Vieta E, Colom F. Treatment adherence in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:1003–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belzeaux R, Correard N, Boyer L, et al. Depressive residual symptoms are associated with lower adherence to medication in bipolar patients without substance use disorder: Results from the FACE-BD cohort. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates JA, Whitehead R, Bolge SC, Kim E. Correlates of medication adherence among patients with bipolar disorder: results of the Bipolar Evaluation of Satisfaction and Tolerability (BEST) Study: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;12 doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00883yel. PCC.09m00883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.First M, Spitzter R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) ed. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peet M, Harvey NS. Lithium maintenance:1. A standard education programme for patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:197–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:384–390. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O'Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43:607–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awad AG. Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:609–618. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sajatovic M, Rosch DS, Sivec HJ, et al. Insight into illness and attitudes toward medications among inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1319–1321. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sajatovic M, Ramirez LF. Rating Scales in Mental Health. 2nd ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shafer A. Meta-analysis of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale factor structure. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:324–335. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1117–1123. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levin JB, Sams J, Tatsuoka C, Cassidy KA, Sajatovic M. Use of automated medication adherence monitoring in bipolar disorder research: pitfalls, pragmatics, and possibilities. Therapeut Advance Psychopharmacology. 2015 doi: 10.1177/2045125314566807. 2045125314566807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Amann BL, Nivoli AM, Vieta E, Colom F. Treatment adherence in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. J Affect Disord. 2013 Dec;151(3):1003–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerullo MA, Strakowski SM. A systematic review of the evidence for the treatment of acute depression in bipolar I disorder. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:199–208. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nivoli AMA, Colom F, Murru A, et al. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaudiano BA, Weinstock LM, Miller IW. Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder: a review of current psychosocial treatment efficacy and recommendations for future treatment development. Behav Modif. 2008;32:267–301. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Six-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Customized adherence enhancement for individuals with bipolar disorder receiving antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:176–178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]