Abstract

Methods to identify the bioactive diversity within natural product extracts (NPEs) continue to evolve. NPEs constitute complex mixtures of chemical substances varying in structure, composition and abundance. NPEs can therefore be challenging to evaluate efficiently with high throughput screening approaches designed to test pure substances. Here we facilitate the rapid identification and prioritization of anti-malarial NPEs using a pharmacologically-driven, quantitative high throughput screening (qHTS) paradigm. In qHTS each NPE is tested across a concentration range from which sigmoidal response, efficacy and apparent EC50s can be used to rank order NPEs for subsequent organism re-culture, extraction and fractionation. Using an NPE library derived from diverse marine microorganisms we observed potent antimalarial activity from two Streptomyces sp. extracts identified from thousands tested using qHTS. Seven compounds were isolated from two phylogenetically related Streptomyces species; Streptomyces ballenaensis collected from Costa Rica and Streptomyces bangulaensis collected from Papua New Guinea. Among them we identified actinoramides A and B belonging to the unusually elaborated non-proteinogenic amino acid-containing tetrapeptide series of natural products. In addition, we characterized a series of new compounds, including an artifact 25-epi-actinoramide A, and actinoramides D, E, F which are closely related biosynthetic congeners of the previously reported metabolites.

Graphical abstract

Evolved over eons to encode biological activity, natural products (NPs) are one of medicine's oldest and most enduring sources of drugs. Once the only means to treat disease, elixirs and traditional medicines ceded considerable ground to the perceived more efficient synthetic chemical approach to drug discovery. However, the chemotypes represented by natural products are among the most versatile for addressing the range of pathogenic microbes that continue to inflict significant health and economic burden on human populations worldwide. For example, the β-lactam antibacterials produced by fungi such as Penicillium sp., the antimalarial alkaloid quinine originally isolated from the bark of the cinchona tree, and artemisinin isolated from the leaf of Artemisia annua stand as prototypical examples of highly impactful therapeutic agents.

While NPs were once the mainstay of our pharmaceutical armamentarium the relative ready access to synthetic agents has dampened interest in maintaining a discovery paradigm involving isolation, structure elucidation, and fermentation of novel medicinally active NPs.1 However, semisynthetic NPs, synthetic agents based or inspired by NPs, and natural products themselves make up a significant portion of drugs today,2,3 and remain an important resource for the expansion of pharmacology into emerging disease target space.4 This strongly suggests that improving the efficiency toward their discovery is an important means to identifying chemotypes with novel mechanisms of action.

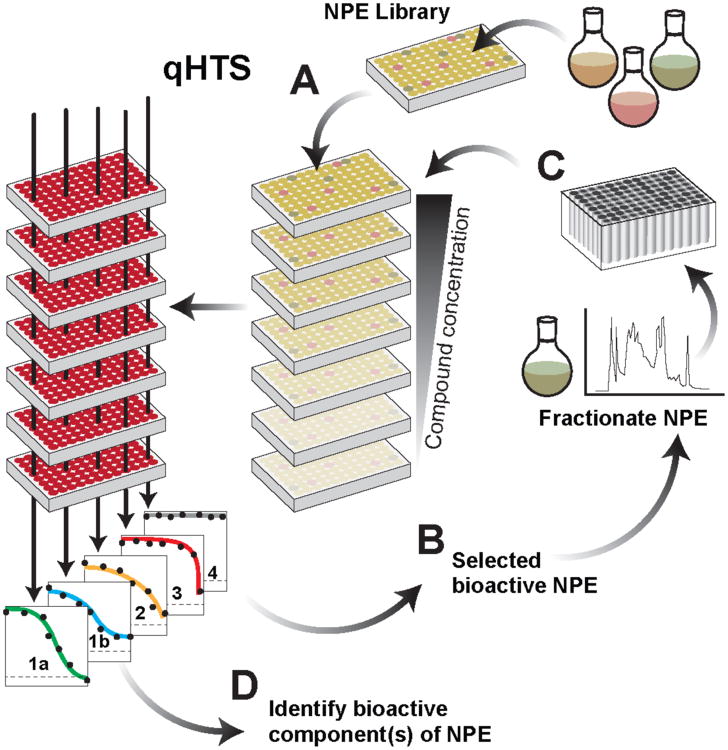

To this end we have embarked on a program to develop more effective approaches to analyze the extracts of marine microorganisms, a proven source of bioactive chemical diversity (Figure 1).5 To maintain diversity, manage source materials, and facilitate re-acquisition of samples for further evaluation we employ minimally enriched natural product extracts from culturable microorganisms. The extracts used in this study are, by virtue of several solvent extractions from Amberlite XAD16 absorbent polymer, largely free of the resins (e.g., oligomeric tannins) and salts that can accompany crude extracts which create significant interferences with sensitive optical outputs of highly miniaturized HTS assays.6 By applying quantitative high throughput screening (qHTS)7 across a series of assays where reinforcing or contrasting outputs can be used to pharmacologically and mechanistically prioritize active samples, the efficiency of identifying biologically relevant activities from NP extracts (NPEs) or other complex mixtures increases significantly. For example, in this study we aimed to identify active compounds that targeted Plasmodium falciparum viability from various geographic localities while selecting for minimal toxicity to human cells.

Figure 1. Overview of natural product extract qHTS.

A pre-fractionated library of Amberlite XAD16 polymer resin enriched natural product extracts (NPEs) is evaluated as a dilution series using a 1536-well assay format to accommodate the added samples, here in a Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) intraerythrocytic SYBR Green viability assay (A). qHTS-derived concentration-response curve (CRC) profiles for each NPE tested are assessed using parameters derived from each CRC, for example EC50, maximal effect and curve class (CC), i.e., 1a, 1b, 2, 3 and 4 (inactive at all concentrations), and selected for follow-up studies (B). NPE microbial strains highest ranking in project profile criteria, here pan-activity on several Pf laboratory stains and low mammalian cell toxicity, are re-cultured, confirmed and fractionated for re-testing (C). Active fractions meeting criteria are subjected to structure elucidation (D).

Results and Discussion

Quantitative High Throughput Screening (qHTS) of NPEs

A library of 16,503 natural product extracts (NPEs) from 5,425 culturable microorganisms prepared by the Amberlite XAD16 extraction method5,8 was screened across 4-orders of magnitude in concentration beginning at 15 mg/mL (assay concentration = 43 μg/mL) and diluting by 5-fold to < 1 μg/mL as described previously5. In the present study we have conducted the qHTS of this NPE library across six geographically distinct lines (cp250, Dd2, HB3, 7G8, GB4 and 3D7) of Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) using a SYBR Green fluorescent DNA staining assay9-11 that enables the intra-erythrocytic measurement of Pf viability (see Tables S1–S2). Using this same approach previously applied to screen several drug/probe libraries12,13 and novel Chemical Methodologies and Library Development (CMLD) libraries14, we herein report efforts to explore the more complex case of NPE libraries.

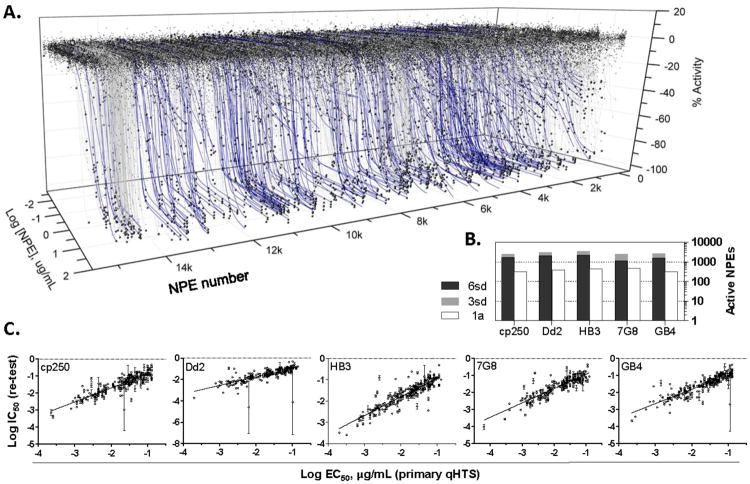

The pharmacological resolving power of qHTS7 yielded the concentration-response curve (CRC) relationships from the NPE library as exemplified in Figure 2A for the Dd2 line. Analysis of the primary qHTS data for the five lines indicated 364 NPEs displayed activity consistent with quality CRCs that we classify as 1a, which is where the sample displays complete sigmoidal response over the concentration range tested (Figure 2b, white bar).7 The impact of the qHTS approach to significantly narrow the consideration of NPEs for further studies is illustrated by our modeling a follow-up compound selection process solely based on % activity at a single concentration of 43 μg/mL This retrospective analysis (explored in depth later in the paper) indicates nearly an order of magnitude more NPEs would cross the activity threshold (Figure 2b, black and grey bars) for a traditional HTS approach vs. qHTS.

Figure 2. Intra-erythrocytic Pf proliferation qHTS of a marine NPE library.

Shown in A. is a representative 3-axis plot for 15,500 microbial NPEs tested against the Dd2 laboratory strain of P. falciparum. NPE numbers increase by alphanumeric sorting of the microbial extract names. Blue lines, high quality concentration-response curves selected for re-testing. B. Bar chart summarizes active NPEs in SYBR Green DNA staining viability assay for five malaria lines. The number of active NPEs per assay are indicated on the y-axis, where the white bars represent class 1a CRC,7 while 3 SD and 6 SD cutoffs for activity at a single concentration of 43 μg/mL are given by the grey and black bars. C. EC50 correlation between activities determined in the primary qHTS vs. retests of 231 NPEs. R2(cp250)=0.73, R2(Dd2)=0.48, R2(HB3)=0.78, R2(7G8)=0.76, R2(GB4)=0.73. NPEs not confirming do not appear in plots, see Data Table S1.

To identify broadly acting antimalarial NPEs we selected those inhibiting Pf viability across multiple laboratory isolates. These initially included both chloroquine-sensitive (HB3, 3D7) and chloroquine-resistant (cp250, Dd2, GB4, 7G8) Pf isolates. NPEs were chosen for further study in the available isolates if they were found across the original six malaria isolates tested to have curve classes 1a, 1b, or 2a with efficacies exceeding a 75% reduction in SYBR green signal and potencies >7.5 μg NPE/L. (Table S3a; also see Experimental Section for additional details). This focused our candidate NPE follow-up to 231 samples derived from 130 culturable species showing pan-activity across the six Pf isolates with high quality CRCs. Some NPE samples were obtained from the same culture but extracted with a different solvent, for example acetone vs. MeOH, therefore resulting in several NPE samples per marine microorganism (see Experimental Section, Isolation of Steptomyces sp. for an example of the multiple solvent extraction procedure). We reacquired these samples from our 384-well source plates and retested these 231 NPEs in the following Pf isolates, cp250, Dd2, HB3, 7G8 and GB4. The reacquired samples were tested in duplicate as 11 point titrations to increase the precision over the primary 7 point qHTS (Figure 2c, Table S2 and Data Table S1). The EC50 correlation between these 231 NPEs and the original qHTS data for the five strains was highly reproducible as determined by the generally high R2 values (Figure 2c) despite several outliers that lowered the R2 in the Dd2 tests. From this analysis 221 NPEs displayed well-fit CRCs across all Pf parasite lines with apparent EC50 potencies ranging from ∼75 ng/mL to ∼7500 ng/mL (Table S3b), confirming the activity of >95% of the NPEs selected for re-test from the primary qHTS. These NPEs were further tested for mammalian cell toxicity using HEK293 and HepG2 lines to generate the activity profile in Figure 3a (also see Table S3b), allowing the separation of NPEs with parasite-restricted vs. broad cellular toxicity (Figure S1a, b). From these we selected 18 NPEs that displayed an activity profile having apparent high potency across all five Pf lines, while showing minimal apparent toxicity in HEK293 and HepG2 cells (See Figure 3b for example CRC profiles).

Figure 3. NPEs selected from primary qHTS and toxicity assessment.

A. Spotfire clustering where NPE activity was calculated as the average EC50 value for all re-acquired extracts (MeOH, acetone and/or EtOAc) against the respective parasite isolate or mammalian cell line. EC50 values determined where curve classes were not equal to 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b or 3 were excluded, as were EC50 values where the p-value of the titration was greater than 0.05. Darker color indicates greater activity in either SYBR Green or Cell TiterGlo assay. Arrows indicate NPE CRCs shown in B. Dotted box frame mammalian cell line response values. The UPGMA clustering method was used for both row and column dimensions using Euclidean distances and ordering weight set to average value. B. Representative 11-point CRC confirmation and mammalian cell line toxicity evaluation for selected NPEs. Data shown are for NPE 07-13-H1I (1), 7714-H2I (2), 276-1 (3), 22278-N3 (4) and 07-234-A1I (5) and broadly toxic NPEs, 7756-H5I (6) and 20755-1I (7); numbers in parenthesis following the NPE number refer to heat map positions. The two data sets per plot are replicate tests (n=2) for a single solvent extract, except for HepG2 which is a single test. Cytotoxicity measured by the CellTiter-Glo assay on HepG2 and HEK293 cell lines. See Figure S1A, B for additional examples.

Culture and Isolation of Active NPE Components

Strains corresponding to 14 of the 18 active NPEs that met our selection criteria were recultured, and subjected to XAD-resin extraction and solvent elution as originally employed to prepare the NPE library5. Step-wise bioassay-guided fractionation traditionally used to resolve the NPE active constituents through a series of chromatographic stationary phases (e.g., silica gel, C4-reversed phase) were bypassed in favor of a more direct approach reducing the assays needed and allowing more rapid acquisition of MS and NMR signatures for preliminary structure assignments. Accordingly, NPEs were subjected to reversed phase HPLC fractionation beginning with 5 mg of the extract for each sample (Figure 4a). Forty-four fractions were collected for each NPE sample and retested in the five Pf and human cell lines, shown for Dd2 in Figure 4B.

Figure 4. Fractionation and testing of selected NPEs.

A. Diagram of NPE fractionation (44 fractions) and preliminary characterization scheme. B. 16 Re-cultured microbial fractionated extracts tested against the Dd2 isolate. Vertical grids separate 44 fractions and original lead parent NPE (magenta) from individual microbial strain growths. Blue curves denote high-quality concentration-response active extract fractions. C. Activity chromatograms for NPE 07-234-A1I from S. bangulaensis and 22278-N3 from S. ballenaensis where the following are indicated: UV absorbance at 210 nm (black line trace); pEC50 from the average of the five P. falciparum lines tested (blue diamond); viability of human RBCs (purple cross), HEK293 cells (red square), and HepG2 cells (green triangle); assay interference due to light absorption by fraction (light blue cross).

Structure Elucidation of Actinoramides as Antimalarial Agents

Based on the HPLC fractionation described above, two phylogenetically related marine Streptomyces species, S. ballenaensis and S. bangulaensis (Figure S2) showed similar bioassay results (Figure 4c). After separating the similar compounds from the two species we focused our efforts on S. bangulaensis, which produced significantly higher levels of an identical suite of active compounds. Further analysis revealed that the major metabolite was the recently described actinoramide A (1) /padanamide A 15,16, whose biosynthetic pathway has recently been characterized17. Actinoramide B (2), also isolated among the active components, was identified by comparison with published spectroscopic data (1H and 13C NMR, HRMS, specific rotation).15 During the NMR experiments, conducted in deuterated pyridine, 1 epimerized. The two epimers were subsequently separated to the known actinoramide A and previously undescribed 25-epi-actinoramide A.

Conversion of Actinoramide A (1) to 25-epi-Actinoramide A (3) and Marfey's Analysis

25-epi-Actinoramide A (3) was isolated as a colorless powder with a molecular formula of C31H48N7O9 based on the HRMS protonated molecule peak at m/z 662.3519 [M+H]+ (Figure S5a). (Figure S5a). Comparison of the 1D and 2D NMR data from actinoramide A (1) (Figure S3b, c) and 25-epi-actinoramide A (3) (Figure S5a–e) suggested only one potential difference at position 25 with a 1H signal shifted from 4.38 ppm for actinoramide A to 4.61 ppm for 25-epi-actinoramide A (Figures S5a, b; Table 1). This prediction was confirmed by Marfey's analysis using 2,4 diamino butyric acid with both compounds, where actinoramide A was shown to have the S configuration whereas 25-epi-actinoramide A had the R configuration (See Scheme S1).

Table 1. 1Ha NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compound 3–6 (DMSO-d6)b.

| Fragmentsc | no. | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| δH (J in Hz) | |||||

| MAA | 2 | 3.80, m | 3.84, m | 3.78, m | 3.82, d (7.4) |

| 3 | 3.28, s | 3.31, s | 3.27, s | 3.30, s | |

| Hle (Hleu) | 4-NH | 7.48, d (9.6) | 7.69, d (8.4) | 7.30, d, (9.0) | 7.29, m |

| 4 | 5.44, t (8.8) | 5.57, t (8.0) | 5.48, t (9.0) | 5.52, t (8.7) | |

| 5 | 3.45, m | 3.53, m | 3.39, m | 3.38, m | |

| 5-OH | - | 4.71, d (5.6) | - | 4.82, d (6.0) | |

| 6 | 1.63, m | 1.68, m | 1.58, m | 1.65, dq (12.9, 6.5) | |

| 7 | 0.87, d (7.2) | 0.89, d (6.8) | 0.86, d (6.8) | 0.86, d (6.7) | |

| 8 | 0.82, d (6.6) | 0.82, d (6.8) | 0.82, d (6.7) | 0.82, d (6.8) | |

| Pip | 10 | 4.92, dd (2.4, 6.0) | 5.00, m | 4.90, m | 4.97, dd (2.4, 6.0) |

| 11 | 1.60, m | 1.57, m | 1.58, m | 1.67, m | |

| 2.06, m | 2.17, m | 2.08, m | 2.13, m | ||

| 12 | 1.26, m; 1.33, m | 1.60, m | 1.37, m | 1.37, m | |

| 2.01, m | |||||

| 13 | 2.75, m | 6.94, d (4.0) | 2.81, m | 2.83, m | |

| 13-NH | 4.39, dd (6.0, 8.4) | × | 4.73, m | 4.52, t (8.4) | |

| Ahmppa (Ahmpp) | 15-NH | 7.49, d (8.4) | 7.37, d (9.2) | 8.14, d (8.6) | 7.65, d (9.0) |

| 15 | 4.10, q (8.4) | 4.03, q (8.4) | 4.08, m | 4.18, brq (8.1) | |

| 2.65, dd (8.0, 13.6) | 2.77, m | 2.78, m | |||

| 16 | 2.75, m | 2.75, dd, (6.8, 13.6) | 2.87, m | ||

| 18 | 7.19, m | 7.16, m | 7.21, m | 7.21, m | |

| 19 | 7.21, m | 7.22, m | 7.23, m | 7.24, m | |

| 20 | 7.13, m | 7.13, m | 7.14, m | 7.15, m | |

| 21 | 3.45, m | 3.41, m | 3.49, m | 3.47, m | |

| 21-OH | - | 4.97, m | - | - | |

| 22 | 2.22, m | 2.23, m | 2.26, m | 2.29, m | |

| 23 | 1.06, d (7.2) | 1.02, d, (7.2) | 1.05, d (6.6) | 1.05, d (6.8) | |

| C-terminal moiety | Auba (Aopc) | Auba (Aopc) | Apd | adhU | |

| 25-NH | 8.03, d (7.8) | 8.09, d (8.0) | 8.05, d (7.6) | 8.04, d (7.8) | |

| 25 | 4.61, m | 4.35, m | 4.44, m | 4.36, m | |

| 26 | 1.81, m | 1.89, m | 1.87, m | 3.00, m | |

| 2.16, m | 2.10, m | 2.27, m | 3.18, m | ||

| 26-NH | × | × | × | 7.60, d (4.4) × | |

| 27 | 3.43, m | 3.44, m | 3.21, m | ||

| 3.69, m | 3.69, t (9.2) | ||||

| 27-NH | 8.03, d (7.8) | 8.09 d (8.0) | 8.10 d (8.5) | 10.20, s | |

| 28-NH | × | × | 8.06 s | × | |

| 29-NH2 | 7.38, brs | 7.40, brs | × | × | |

| 7.71, brs | 7.72, brs | ||||

δ(ppm) 600 MHz;

in DMSO-d6;

Fragment nomenclature based on ref 13 and 14, 2-methoxyacetic acid, MAA; 3-hydroxyleucine, Hle (Hleu); piperazic acid, Pip; 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-phenylpentanoic acid, Ahmppa (Ahmpp); 3-amino-2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide, Auba (Aopc); cyclic 4-acetoamide-2-aminobutanoic acid (Aaba). 3-aminopiperidine-2,6-dione (Apd); 5-amino-dihydrouracil (adhU) this study.

Actinoramide D (4) was isolated as a colorless powder corresponding to a molecular formula of C31H46N7O9 based on HRMS (Figure S6a). Comparing the 1H NMR of actinoramide D (Figure S6b) to actinoramide A (Figure S3b) revealed a loss of an NH signal (δH 4.52 ppm) and substitution of the methylene signals (δH 2.79, δC 46.0 ppm) with those for a methine (δH 6.94 ppm, δC 143.8 ppm). Analysis of gCOSY, gHSQC and gHMBC NMR spectroscopic data (Figure S6c–e) revealed the unsaturated piperazic acid with a double bond linking C-13 to the adjacent nitrogen (Figure S6a). A previous study on the kutzneride biosynthetic cluster 18 indicates that the unsaturated piperazic acid moiety is a probable precursor to the saturated ring system. Another confirmation for the actinoramide D structure came from a small-scale hydrogenation experiment where actinoramide D was reduced to actinoramide A. The reduced product had identical retention time, UV spectrum and molecular weight compared to actinoramide A. HPLC co-injection was also performed to confirm the identification of actinoramide A (Scheme S2).

Actinoramide E (5) was isolated as a colorless powder corresponding to a molecular formula of C30H46N6O8 based on the HRMS protonated molecule peak at m/z 619.3459 [M+H]+ (Figure S7a). The 1H and 13C NMR (Table 2) spectra of actinoramide E are almost identical to those reported for actinoramide A except that the actinoramide E spectra show the loss of a carbonyl (δC 152.7 ppm) and NH (δH 7.73 and 7.42 ppm) signals, and gain of an amide signal (δH 8.06 ppm). Based on all of the NMR data actinoramide E should have the 3-aminopyrrolidin-2-one moiety instead the 2-amino-4-ureidobutanoic acid in actinoramide A (Figures S7b–f).

Table 2. 13Ca NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compound 1–6 (DMSO-d6)b.

| Fragmentsc | no. | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| δC, type | |||||

| MAA | 1 | 168.5, C | 168.8, C | 168.1, C | 168.4, C |

| 2 | 70.9, CH2 | 70.8, CH2 | 71.2, CH2 | 71.2, CH2 | |

| 3 | 58.3, CH3 | 58.1, CH3 | 58.5, CH3 | 58.5, CH3 | |

| Hle (Hleu) | 4 | 49.9, CH | 50.8, CH | 49.4, CH | 49.4, CH |

| 5 | 74.7, CH | 75.1, CH | 74.9, CH | 75.1, CH | |

| 6 | 29.0, CH | 29,0, CH | 28.8, CH | 29.2, CH | |

| 7 | 19.8, CH3 | 19.7, CH3 | 19.8, CH3 | 20.1, CH3 | |

| 8 | 15.3, CH3 | 15.5, CH3 | 15.2, CH3 | 15.6, CH3 | |

| 9 | 172.3, C | 172.0, C | 172.0, C | 172.1, C | |

| Pip | 10 | 50.9, CH | 51.5, CH | 50.5, CH | 50.9, CH |

| 11 | 25.1, CH2 | 18.3, CH2 | 25.5, CH2 | 25.9, CH2 | |

| 12 | 20.5, CH2 | 19.8, CH2 | 20.8, CH2 | 20.8, CH2 | |

| 13 | 45.7, CH2 | 140.8, CH | 46.0, CH2 | 46.4, CH2 | |

| 14 | 170.0, C | 169.6 C | 173.8 C | 170.4 C | |

| Ahmppa (Ahmpp) | 15 | 52.1, CH | 52.8, CH | 52.7, CH | 52.9, CH |

| 16 | 37.7, CH2 | 37.3, CH2 | 37.0, CH2 | 37.3, CH2 | |

| 17 | 138.8, C | 138.7, C | 139.6, C | 139.0, C | |

| 18 | 128.6, CH | 128.6, CH | 129.1, CH | 129.1, CH | |

| 19 | 127.8, CH | 127.7, CH | 128.0, CH | 128.1, CH | |

| 20 | 125.6, CH | 125.4, CH | 125.9 | 125.9 | |

| 21 | 71.6, CH | 71.4, CH | 71.7, CH | 71.8, CH | |

| 22 | 43.1, CH | 42.6, CH | 42.9, CH | 43.2, CH | |

| 23 | 15.0, CH3 | 14.5, CH3 | 15.3, CH3 | 15.0, CH3 | |

| 24 | 174.3, C | 174.0 C | 173.8, C | 174.4, C | |

| C-terminal moiety | Auba (Aopc) | Auba (Aopc) | Apd | adhU | |

| 25 | 51.3, CH | 51.8, CH | 49.2, CH | 47.3, CH | |

| 26 | 23.8, CH2 | 23.0, CH2 | 23.7, CH2 | 40.0, CH2 | |

| 27 | 41.7, CH2 | 41.1, CH2 | 41.2, CH2 | 153.2, C | |

| 28 | 174.7, C | 174.4, C | 175.8, C | 170.0, C | |

| 29 | 152.7 C | 154.2, C | |||

δ(ppm) 150 MHz;

in DMSO-d6;

Fragment nomenclature based on ref 13 and 14, 2-methoxyacetic acid, MAA; 3-hydroxyleucine, Hle (Hleu); piperazic acid, Pip; 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-phenylpentanoic acid, Ahmppa (Ahmpp); 3-amino-2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide, Auba (Aopc); cyclic 4-acetoamide-2-aminobutanoic acid (Aaba). 3-aminopiperidine-2,6-dione (Apd); 5-amino-dihydrouracil (adhU) this study.

A new natural product, actinoramide F (6) was isolated as a colorless powder corresponding to the molecular formula of C30H45N7O9 based on HRMS (Figure S8a). Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of actinoramide F and actinoramide A showed no difference for the hydroxy leucine bearing the methoxy acetate substitution, piperazic acid and 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-phenylpentanoic acid backbone (Figures S8b, c). The 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-phenylpentanoic acid carbonyl 13C signal at δC 174.4 ppm showed an HMBC correlation from an amidic proton resonating at δH 8.04 ppm. This amidic proton showed a COSY correlation with a methine proton δH 4.36 ppm (δC 47.3 ppm), which correlates to methylene protons δH 3.18 ppm (δC 40.0 ppm), and to an amidic proton δH 7.60 ppm (Figures S8d–f). All of these correlations were confirmed by HMBC correlations (Figure S8e). The amidic proton resonating at δH 7.60 ppm show another HMBC correlation to a carbonyl carbon resonating at δC 153.2 ppm, which shows a correlation from another amidic proton δH 10.20 ppm. The carbonyl carbon resonating at δC 170 ppm shows two HMBC correlations, the first to the amidic carbon at δH 10.20 ppm, and the second to the previously described methine at δH 4.36 ppm, which forms the dihydrouracil ring system (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Dihydrouracil ring system.

The novel terminal end group of actinoramide F (6) differs from actinoramide A (1) by virtue of 5,6-dihydrouracil replacing the 2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide.

During our study another dihydrouracil analog was isolated where the piperazic acid is unsaturated similar to actinoramide D. Due to lack of material and purity issues (this compound was isolated as a mixture with actinoramide F), this compound was incompletely characterized primarily by NMR and HRMS.

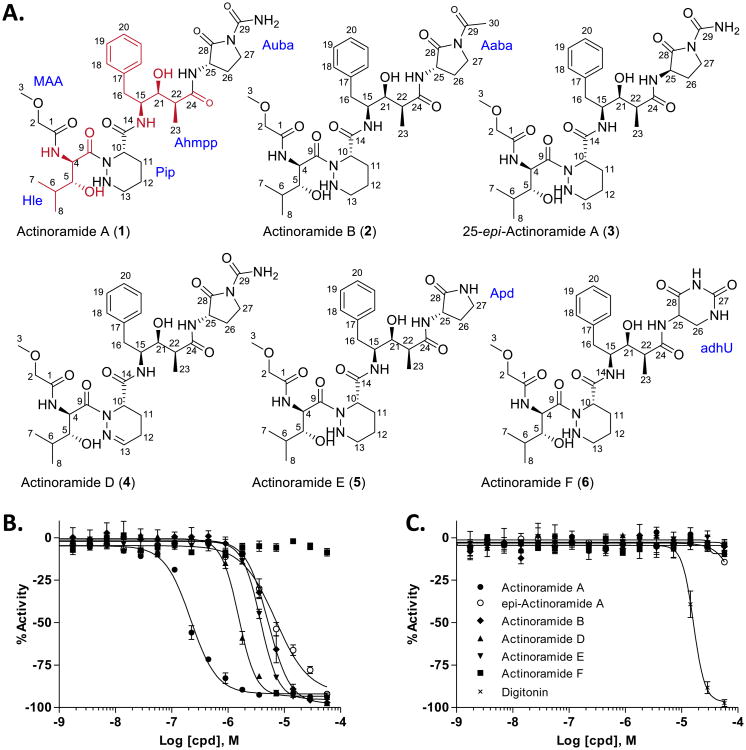

Antimalarial Activity of the Actinoramides

The natural products isolated from S. bangulaensis include members of the recently discovered actinoramide/padanamide family of modified tetrapeptides illustrated in Figure 6a 15,16. Once purified and structurally characterized, the actinoramides were re-examined against in vitro cultured P. falciparum parasites and human cell lines. The results show a clear separation in activity between actinoramide A and 25-epi-actinoramide A of approximately 20-fold, with the highly active actinoramide A displaying an EC50 of approximately 200 nM in all five parasite lines retested (Figure 6b; Figure S9a and Table S4). Strikingly these compounds show virtually no toxicity toward the HepG2 and HEK293 human cell lines tested in this study (Figure 6C and Figure S9b).

Figure 6. Activity of the actinoramides on blood stage parasite (Dd2 line) and a hepatocyte cell line.

A. Structures of the actinoramides. (2R, 3R)-2-amino-3-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoic acid and (2S, 3S, 4S)-4-amino-3-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-phenyl pentanoic acid amino acids are shown in red. 1H and 13C NMR, HSQC, HMBC, COSY, data for compounds 1–6 and ROESY and TOCSY data for compounds 3–6 are provided in Tables 1 and 2 and Figures S3–S8. B. Actinoramide congener activity on 3D7 showing stereoselective antimalarial activity of the 25S (solid circles, actinoramide A) and 25R (open circles, 25-epi-actinoramide A) isomers of actinoramide A. The activity of these compounds on all five blood stage parasites (Dd2, HB3, 7G8, GB4, and cp250) are provided in Figure S9a. C. Effect of the actinoramides on viability of HEK293 cells (for effect on viability of HepG2 cells see Figure S9b). Digitonin control (}). n=2 or greater for all experiments, error bars are SD of mean.

One possible P. falciparum candidate target class of actinoramide A is suggested by the presence of statine-like amino acids moieties in the molecule (see Figure 6a, red substructures). By mimicking the tetrahedral transition-state in aspartyl protease-catalyzed peptide bond hydrolysis statine-containing peptides such as pepstatin are potent class-specific protease inhibitors19. We therefore examined if actinoramide A would be capable of inhibiting the aspartyl protease activity of P. falciparum plasmepsins found in the digestive vacuole of the parasite20. Using freshly prepared P. falciparum extracts we demonstrated the presence of plasmepsin activity using a pro-fluorescent FRET peptide substrate (Figure S10a) based on internal FRET quenching21. While pepstatin potently inhibited the aspartyl protease activity of our Pf extracts, actinoramide A had no effect up to 100 μM, nor did the S. ballenaensis or S. bangulaensis NPEs (Figure S10b, c), leaving the Pf target of actinoramide A in question.

The actinoramides/padanamides were recently isolated by two independent laboratories from marine Streptomyces sp. originating from the coastal regions of Papua New Guinea16 and southern California15. In the latter case the compounds isolated from this halophilic Streptomyces species (CNQ-027) failed to demonstrate activity against a HCT-116 human colon carcinoma cell line and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. In the former, two compounds were isolated, padanamide A which is identical to actinoramide A, and padanamide B. Padanamide A and padanamide B differ at their terminal functional groups, bearing either the 2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide or piperidine-2,6-dione, respectively. Padanamide A (actinoramide A) and padanamide B were shown to be somewhat cytotoxic to Jurkat cells (EC50 ≈ 60 μg/mL (90 μM) and 20 μg/mL (30 μM), respectively), although such concentrations can be considered relatively benign in cell culture studies. In this study actinoramide A/padanamide A was discovered independently from NPEs prepared from cultures of Streptomyces sp. isolated from the Costa Rican coast by qHTS in an array of P. falciparum viability assays. We observed a consistent 20–50-fold separation in potency between the 25R and 25S diastereomers of actinoramide A (padanamide A) with no toxicity to HEK293 or HepG2 cells at the highest tested concentrations (Figure S9; Table S4). This activity is differentiated by the configuration at the terminal tertiary carbon of the 2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide ring (Figure 6a). We further observed the apparent oxidation product of the piperazic acid moiety (dehydro actinoramide A, characterized herein as a new congener actinoramide D; Figure 6a, 4) had an observable effect on its activity in our malaria assays leading to a ∼6–20-fold decrease in potency depending on the parasite strain (Figure S9a; Table S4). In addition to the actinoramide A congeners, we isolated a structurally related metabolite. Actinoramide F (Figure 6a, 6) differs from actinoramide A at the terminus of the tetrapeptide where the 3-amino-2-oxopyrrolidine-1-carboxamide (Aopc; also referred to as cyclic 2-amino-4-ureidobutanoic acid (Auba)15 is replaced by a 5-amino-5,6-dihydrouracil (adhU). Actinoramide F showed no antimalarial activity (Figure 6b), which strongly implicates the terminal moiety of actinoramide A as a key active substituent of the molecule.

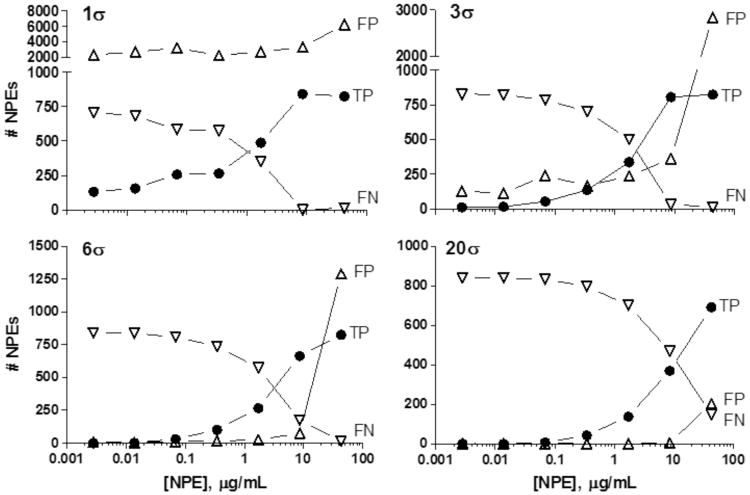

To gain additional insight into how, and under what conditions, the Pf SYBR Green viability assay would best perform in a single test concentration experiment with NPEs, we re-analyzed the primary qHTS data obtained from the Dd2 Pf isolate. Using the qHTS curve classification7 (Figure 1), we defined the NPEs with active curve classes (i.e., 1a, 1b and 2) as true positives (TP), and for simplicity, all other curve classes (i.e., 3 and 4) as true negatives. In a scenario with few limits on follow-up capacity of candidate NPEs, a 1σ (i.e., 1 standard deviation from the mean of the DMSO treated control) and more likely 3σ activity threshold were examined. In the 1σ threshold case, the number of false positives (FP) would likely be untenable, numbering in the thousands and rising with increasing tested concentrations. It is interesting to note that not all the TPs with the 1σ hit cutoff would be found unless tested at the second highest concentration of 10 μg/mL NPE as illustrated in Figure 7. That is, 15 TP NPEs would be missed at the highest concentration of 43 μg/mL NPE.

Figure 7. Analysis of qHTS data at a single NPE concentration with various hit threshold scenarios.

Solid circles, true positives (TP); open triangles, false positives (FP); open down triangles, false negatives (FN). See Discussion for description. σ = standard deviation

Using a 3σ cutoff, most of the qHTS actives (807 of 840) would be found if tested at 10 μg/mL, but would be accompanied by 392 FPs. At the third and fourth highest concentrations, the false negatives (FN) would exceed the TPs, and yield comparable numbers of FPs to TPs (137 TP, 167 FP at 0.344 μg/mL NPE; 338 TP, 228 FP at 1.73 μg/mL NPE). Again, at the highest tested concentration, only 15 NPEs characterized as qHTS actives would be missed, but an unreasonable 2,843 hits are FPs, inactive in qHTS.

At more stringent hit thresholds of 20σ and 6σ, the lowest tested concentration results generally in higher FNs with an accompanying reduction in FPs. As expected, using a 20σ threshold yields fewer actives and more FNs at any tested concentration. Examining the highest tested concentration, 692 hits are actives according to qHTS criteria and 148 FNs result, the fewest of any of the tested concentrations. Of the 895 overall hits in this scenario, 203 NPEs would be characterized as negative by qHTS, supporting an overall trend of FPs tracking with TPs in any single-concentration screening scenario, and suggesting an intrinsic FP rate related to the threshold. Of the four threshold scenarios, the best case might use a 6σ cutoff at the second highest concentration tested. Compared to the 20σ cutoff, a slightly more modest 21% (176 of 840) of the actives found using qHTS are not found using a threshold of 6σ, while simultaneously keeping the false positive hits down to 74, although the split between TPs and FNs is slightly worse at 664 and 176, respectively.

In this study we examined the effect of a library of pre-fractionated marine natural product extracts5,8 on the viability of Plasmodium falciparum in its RBC host using qHTS. The resulting CRCs displaying potent antimalarial activity were clearly separable from those having accompanying mammalian cellular toxicity as indicated by a parallel HEK293 and HepG2 viability screen, facilitating selection of NPEs with optimal profiles for subsequent reversed phase fractionation and structure elucidation. The screening methodology described here focuses the prioritization of NPEs to a limited number of microbial species for re-culture. We anticipate the paradigm's capacity to resolve primary activity by EC50 with minimal library consumption will prove useful for the evaluation of other forms of complex or multicomponent chemical libraries which may exist or be prepared in initial limited quantities.22-26

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Harvard Medical School (Compounds 3 and 4): Optical rotations were obtained using a Jasco P1010 Polarimeter. UV spectra were measured on Amersham Biosciences Ultrospec 5300 spectrophotometer. IR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Alpha-P UV/visible spectrophotometer. All NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer. Compounds 1 and 3 were purified on an Agilent 1100 series HPLC (Agilent Technologies) using a preparative Phenomenex Luna Phenyl-hexyl column. University of Michigan (Compounds 1, 2, 5 and 6): Optical rotations were determined on a Jasco P2000 polarimeter. UV spectra were measured on a UV-visible Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer using 1 mL cuvettes with 1.0 cm path lengths at room temperature in solvent CH3OH. IR spectra were obtained on a Perkin Elmer FTIR spectrometer equipped with Miracle ATR accessory. The NMR spectra were acquired at 600 MHz for 1H and 150 MHz for 13C on Varian Inova 600 MHz spectrometer. High-resolution MS spectra were measured at the University of Michigan core facility in the Department of Chemistry using an Agilent 6520 Q- TOF mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent 1290 HPLC system. The LCMS analysis of HPLC fractions was performed on a Shimadzu 2010 EV APCI spectrometer. HPLC separations were performed on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system consisting of a G1311A pump and DAD detector G1315B equipped with Clarity software using Merck HiBar LiChrospher 60 RP-Select B, 5 μm, 250×25 mm and Phenomenex, Cosmosil C8, 4.6 μm, 250×20 mm, type: Waters HPLC columns using a solvent system of CH3CN and H2O.

SYBR Green DNA-staining Parasite Viability Assay

Briefly, 3 μL of culture medium was dispensed into 1,536-well black clear-bottom plates (Aurora Biotechnologies) using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) followed by 23 nL NPE via pin tool transfer (Kalypsys), then 5 μL of P. falciparum–infected RBCs (0.3% parasitemia, 2.5% hematocrit final concentration). The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator in 5% CO2 for 72 h, after which 2 μL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl,10 mM EDTA, 0.16% saponin (w/v), 1.6% Triton-X (v/v), 10× SYBR Green I (supplied as 10,000×concentration by Invitrogen) were added to each well. The plates were incubated overnight at 22–24 °C in the dark. The following morning, fluorescence intensity at 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission wavelengths was measured on an EnVision (Perkin Elmer) plate reader. The compound library was screened against each parasite line at seven five-fold dilutions beginning at 15 mg/mL DMSO stock. The antimalarial drugs, artemisinin and mefloquine, and DMSO were included as positive and negative controls for each plate, respectively. Additional details can be found in protocol Table S1 and Refs. 13 and 14.

Analysis of qHTS Data and Selection of Follow-up NPEs

NPE concentration-response curves (CRC) from the qHTS were determined from the normalized and corrected data as previously described.13 CRCs for each NPE were curve-fitted and categorized into four major curve classes (CC) as described7 using freely available NCATS software (http://ncgc.nih.gov/pub/openhts/curvefit/). Briefly, NPEs in class 1 produce a complete response curve containing two asymptotes. Sub-classification of CC = 1 CRCs into either 1a or 1b is based on the magnitude of the response relative to control, where 1a is equal to ≥80% of control inhibition and 1b <80%. NPEs comprising class 2 have incomplete response curves containing one asymptote and can be likewise subcategorized into a or b. NPEs fitting class 3 curves display activity only at the highest tested concentration or are poorly fit class 1 or 2 curves with r2 less than 0.9. NPEs with class 4 curves are inactive, and either they do not have a curve fit or the curve fit is below three SD of the mean basal activity (about 30% of the maximal control response).

Preliminary selection criteria for NPEs with pan-isolate antimalarial activity used qHTS data from six Pf assays, two using chloroquine-sensitive (HB3 and GB7) and four using chloroquine-resistant (cp250, Dd2, GB4, 7G8) laboratory isolates. An NPE was considered active, and promoted for follow-up testing if it displayed a high quality CC of either 1 or 2a in each of the six assays, with measured IC50 values less than 7500 ng/mL and efficacies exceeding a 75% reduction in SYBR green signal. This identified 235 pan-active NPEs (Table S3a, pan-active NPE counts in parenthesis), of which 231 were available in sufficient amounts from our 384-well archive for retesting. The relatively few samples displaying color interference (11 NPEs) or RBC toxicity (1 NPE) were flagged.

The 231 NPEs retrieved from the archive and tested using 11-point titrations were then selected for regrowth using the more stringent conditions of only curve classes 1a or 2a with the IC50 of all five Pf isolates <7500 ng/mL, and no measurable or weak effects in HEK293 and HepG2 cell viability assays. Using these criteria, 29 NPEs representing 18 microbial strains were selected for regrowth. Fourteen of the 18 microbial strains were available for regrowth and fractionation.

Mammalian Cell Viability Assays

Cell viability assays for HEK293 and HepG2 lines, and RBCs were carried out using Cell TiterGlo (Promega) according to manufacturer's instructions. Assays were performed in solid white 1536-well plates (Nexus Biosystems) and measurements made on a ViewLux (Perkin Elmer). See Brown et al. 14 for additional details.

Optical Interference Assay

Potential compound interference with the SYBR Green viability assay was determined by adding test compound following a 72 h incubation time and reading fluorescence intensity at 485/535 nm EX/EM on an EnVision (Perkin Elmer). See Brown et al.14 for additional details.

Preparation of Actinoramides for Follow-up Testing

From ∼2 mg of actinoramide A (MW: 661) in 1 mL of CH2Cl2: CH3OH (50/50 v/v), 400 μg in that solution was taken (and then dried), and 30 μL of molecular biology grade of DMSO was added to make a 20 mM DMSO solution. The other samples were prepared similarly.

Plasmepsin Protease Assay

A P. falciprarum parasite extract (saponin treated and RBC removed) was prepared as previously described22 to enable a plasmepsin protease assay using the EDANS-DABCYL Plasmepsin II fluorogenic substrate, EDANS-COCH2CH2CO-ALERMFLSFP-Dap(DABCYL)OH (AnaSpec). An estimated KM value was calculated for the Pf preparation and compared to the aspartic protease pepsin. Briefly, 2 μL of assay buffer (100 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0 and 20% glycerol) was dispensed into black, clear bottom 1536-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) followed by 1 μL of the respective protease or protease preparation across 3–5 different concentrations using a BioRaptr Flying Reagent Dispenser (Beckman Coulter). Plates were sealed, centrifuged for 1 min and incubated at room temperature, protected from light for 15 min. Baseline fluorescence was read on the Tecan Infinite M1000. 1 μL of a 4-pt titration of the EDANS-DABCYL Plasmepsin II fluorogenic substrate was added to respective wells as above. Plates were sealed, centrifuged for 1 min and fluorescence at EX 336 nm, 5 nm bandwidth and EM 490 nm, 10 nm bandwidth was measured for 3 h. Actinoramide congeners, and three fractions of NPE 07-234-A1I and 7714-H2I were tested under KM conditions for inhibitory activity on the plasmepsin-containing extracts. Assay plates were set up as above and 23 nL of each compound were transferred via pin tool (Wako) followed by addition of 1 μL of pepsin (50 nM final concentration) or plasmepsin pellet (P) extract (0.16% final concentration). Following a 15 min incubation 1 μL of EDANS-DABCYL Plasmepsin II fluorogenic substrate (5 μM or 10 μM final concentration) was added to each well. Plates were read for 3 h as described above (Table S5). Data was plotted and KM and EC50 values were calculated in GraphPad Prism 5.

Marine Microbes

Marine sediments were collected by scuba diving; the source material resulting in S. ballenaensis (Sherman lab 22278-N3) was collected near the “whale tail” isthmus close to Uvita, Costa Rica (9° 8′ 37.5″, -83° 45′ 21.7008″). The second strain S. bangulaensis (Sherman Lab 07-234-A1) was derived from marine sediments collected at the Bangula Bay, New Britain Island, Papua New Guinea (-5°25′40.5600″, 150°46′10.0200″).

Isolation of Streptomyces spp

S. ballenaensis and S. bangulaensis isolation was based on a modified protocol of Imura and Yamamura 27 where 500 mg of wet sediment was diluted in 10 mL of sterile water and vortexed for 10 min. One mL of this suspension was then applied directly to the top of the discontinuous sucrose gradient and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 300× g. 500 μL of the 20%, 30%, and 40% layers were then plated to HVA agar supplemented with 10 μg/mL chlortetracycline, 25 μg/ml cyclohexamide, and 25 μg/ml of nalidixic acid. The plates were then incubated at 28 °C for one month. The colony was picked off the plate and streaked onto International Streptomyces Project media 2 (ISP2) agar supplemented with 3% NaCl to mimic sea water salinity until pure. Seed cultures were grown in 17 mL dual position cap tubes containing 2 mL of ISP2 and grown for 4 days on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. The seed culture was then poured into a 250 mL baffled flask containing 100 mL of ISP2 and grown for 21 days for S. ballenaensis sp. and 19 days for S. bangulaensis sp. on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. The culture was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cells and 2 g of XAD16N resin (Sigma-Aldrich) contained within a polypropylene mesh bag was added to the broth and incubated overnight on the rotary shaker. The resin bag was removed and placed into 10 mL of CH3OH followed by 10 ml of acetone and 10 mL of EtOAc. Each of the three fractions was dried in vacuo and reconstituted to a final concentration of 15 mg/mL in DMSO.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification of 16S rRNA Genes, Cloning, and Sequencing

Prior to DNA extraction, 1 mL of a liquid culture of Streptomyces sp. (S. ballenaensis and S. bangulaensis) was combined with 100 μL of 10 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma catalog no. L6876-5G) then incubated in a 35 °C water bath for 1 h. After incubation, the cell material was centrifuged and the supernatant discarded. DNA was extracted from the resulting cell material using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega cat. A1120). The manufacturer's protocol was modified to include mechanical disruption after the addition of the Nuclei lysis solution (step 6). A portion of the 16S rDNA genes were amplified by PCR from the DNA using the primers FC27 and RC1492 previously described27-29. Reaction mixtures consisted of 2.5 μL of DNA (250 ng), 10 μL of 5× Phusion GC buffer, 1.0 μL of dNTP mix (10 μM of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 2.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), 1.5 μL of DMSO, 0.5 μL of Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs cat. F-530S), and 28.5 μL of H2O for a total volume of 50 μL. The reaction was performed using a Bio-Rad iCycler thermal cycler with the following reaction program: initial denaturation for 30 s at 98 °C, 30 cycles of amplification with 10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 50 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C, and a final elongation of 5 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified using the Zymo Gel DNA Recovery Kit. The manufacturer instructions were modified by combining 250 μL of the Binding Buffer with 50 μL of PCR products then skipping to step 4 of the instructions. The purified PCR products were modified to add a 3′-A overhang using Taq DNA polymerase. Reaction mixtures consisted of 3 μL of PCR product, 1 μL of 10× Taq buffer, 2 μL of 1 mM dATP, 0.5 μL of Taq DNA polymerase, and 3.5 μL of H2O for a total volume of 10 μL. The reaction was incubated for 30 min at 72 °C using a Bio-Rad iCycler thermal cycler. The modified PCR products were ligated into a pGEM vector using the Promega pGEM-T Vector Kit. The resulting pGEM-16S rDNA construct was transformed into chemically competent E. coli XL1-Blue cells and cultured on LB-ampicillin plates. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Zymo Plasmid Miniprep Kit (cat. no. D4037) and sequenced using the primers T7 and SP6. 16S rRNA sequences were deposited at GenBank with the following accession numbers: Streptomyces ballenaensis (KT333053) and Streptomyces bangulaensis (KT333054)

Phylogenetic Analysis of Marine Streptomyces Species

The genetic analysis of Streptomyces ballenaensis and Streptomyces bangulaensis was performed using a 1.5 kb sequence of the 16S rRNA gene. A Blast search of the 16S rRNA sequence was employed to retrieve sequence data for the phylogenetic analysis. Only sequences of at least 1.3 kb were retrieved from GenBank as well as the two other actinoramide like producing strains Streptomyces sp. RJA2928 (padanamide producer) and Streptomyces sp. CNQ-027_SD01. The 16S rRNA sequence of Micromonospora aurantiaca ATCC 27029 was used as an out group. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted with Geneious Pro 4.8.4. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method.30 S. ballenaensis and S. bangulaensis show high phylogenetic similarity (d=1.16 ×10-4). The closest member was Streptomyces sp. VTT E-062996 (d = 4.21×10-4). It is also worth noting that the padanamide A producing Streptomyces sp. RJA2928 (d=0.0124), and the actinoramides producing strain CNQ-027_SD01 (d=0.0147) were more distant than the bacteria of the S. albiaxailis/paraguayensis clade (Figure S2).

Cultivation and Extraction

Two marine-derived microorganisms, S. ballenaensis and S. bangulaensis were cultured each in two 6 L Erlenmeyer flasks each containing 2.5 L of ISP2 medium and shaken at 200 rpm at 27 °C. After 21 days of cultivation for S. ballenaensis strain and 19 days of cultivation for S. bangulaensis strain the cells were separated from the broth by centrifugation (5500 RPM for 30 min). Washed XAD-16 resin (15 g/L) was added to the broth using 30 g resin bags in order to adsorb the organic substances, and the culture and resin were agitated at 200 rpm overnight. The XAD resin was washed with Milli-Q H2O and extracted with three different solvents, MeOH, acetone and EtOAc. The biological activity of these two extracts was evaluated using gradient HPLC separation (5-100% CH3CN over 30 min). 5 mg of the extract was injected onto the HPLC column and 60 fractions were collected (every 30 s) evaporated and transferred for biological activity evaluation. Results of the biological activity assay were plotted on top of the 210 nm UV chromatogram to identify the active HPLC peaks (Figure 4).

Based on the enhanced metabolite production and biological activity results, S. bangulaensis was pursued for longer-term metabolite analysis. However, all of the known and novel molecules described in this work were isolated from the strains obtained both from Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea.

Isolation Procedure

Initial fractionation of S. bangulaensis species: The XAD resin was washed and extracted as described above to give three extracts: MeOH (402.9 mg), acetone (170 mg), and EtOAc (46 mg). The MeOH extract showed the expected antimalarial activity and was further purified using similar chromatography procedures. The MeOH extract was separated on an ODS (YMC-GEL, 120 Å, 4.4×10 cm) flash column with 10 percent increasing amounts of MeOH in H2O and washed using EtOAc to obtain 11 fractions labeled (A-K). Based on the NMR spectra and the biological activity assay fractions D (79.7 mg) and E (18.1 mg) were further separated. Fraction D was subjected to a reversed phase HPLC column (Merck HiBar LiChrospher 60 RP-Select B, 5 μm, 250×25 mm, Agilent 1100 series HPLC, DAD at 210 and 238 nm, flow rate 5.0 mL/min) eluted with 4:6 CH3CN/H2O to give two semi-pure fractions, D4 (8.6 mg) and D6 (32 mg). Fraction D6 (32 mg) was further separated on a reversed phase HPLC column (Phenomenex, Cosmosil C8, 4.6 μm, 250×20 mm, type: Agilent 1100 series HPLC, DAD at 210 and 238 nm, flow rate 5.0 mL/min) eluted with 4:6 CH3OH/H2O. Seven fractions were collected; two of them were pure compounds. Fraction D6b (1.2 mg, tR =29.8 min, MH+ 660.37 g/mol) was established to be the new compound actinoramide D (4). Fraction D6c (24.1 mg, tR =34.1 min, MH+ 662.47, MNa+ 684.37 g/mol) was established to be the known compound padanamide A 16 /actinoramide A (1)15, and this compound was also isolated from the crude isolate E. Fraction D6e (2.4 mg, tR =39.3 min, MH+ 661.3564, MNa+ 683.3373 g/mol) was established to be the known compound actinoramide B.13 Fraction D4 (8.6 mg) was further separated on a reversed phase HPLC column (Phenomenex, Cosmosil C8, 4.6 μm, 250 × 20 mm, type: Jasco PU 2080 Plus HPLC, DAD at MaxAbs, flow rate 5.0 mL/min) eluted with 45:55 CH3OH/H2O. Five fractions were collected; one of them was a pure compound. Fraction D4a (1.3 mg, tR =24.3 min, MH+ 648.47 g/mol) was established to be actinoramide F (6), while fraction D4c (2.2 mg, tR =27.4 min, MH+ 646.43 g/mol) was established to be the mixture of actinoramide F and its unsaturated piperazic analog. Fraction 2D5 (1.1 mg, tR =32.3 min, MH+ 619.37 g/mol) contains actinoramide E (5).

S. bangulaensis Strain Secondary Cultivation and Fractionation

Seed cultures were generated by inoculating 10 mL of ISP2 growth media in a 50 mL glass culture tube containing a stainless steel spring for aeration with 10 μL of S. bangulaensis from spore preparation glycerol stock. At this point, 1 mL of seed culture was used to inoculate 100 mL of ISP2 growth media in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing a circular stainless steel spring at the base for aeration. This culture was grown at 28 °C with shaking at 180 rpm until the culture reached the stationary phase of growth. Finally, 20 mL of this culture was used to inoculate 2 L of modified ISP2 media containing high C:N (contained 15 g/L malt extract instead of 10 g/L that is used in standard ISP2 media) in a 6 L flask containing a large stainless steel circular spring at the base for aeration (15 flasks resulting in 30 L total culture). The process was repeated as described above to isolate actinoramide A, E and F. Actinoramide D was detected as a mixture with actinoramide A in a 5:1 ratio, respectively.

Conversion of Actinoramide A (1) to 25-epi-Actinoramide A (3) and the Separation

3 mg of actinoramide A (1) was dissolved in 500 μL pyridine-d5 for overnight NMR. 1H NMR spectrum showed that it was a mixture of two components (4:1, actinoramide A:25-epi-actinoramide A). The mixture was separated by using semi-preparative HPLC (Phenomenex, Luna, Phenyl-hexyl, 250 × 10 mm, 5 μ, 2 mL/min, 33:67 CH3CN/H2O with 0.1% formic acid). Actinoramide A (1) and 25-epi-actinoramide A (3, 0.6 mg) had retention time of 21.2 and 23.0 min, respectively.

Small Scale Reduction of Actinoramide D to Actinoramide A

Actinoramide D (100 μg, 0.15 μmol), NaBH3CN (12 μg, 0.19 μmol), and trace amount of acetic acid in about 100 μL of dry CH3CN were magnetically stirred at room temperature. After 1 h, the reaction mixture was analyzed by LC/MS. The reduced product had the same retention time, same UV spectrum and same molecular weight as actinoramide A. HPLC co-injection analysis was also performed to confirm the identity of actinoramide A.

Marfey's Analysis

Actinoramide A (1), 25-epi-actinoramide A (3) or actinoramide E (5) (0.2 mg) were hydrolyzed in 170 μL of 6 N HCl at 108 °C for 20 h, the HCl was removed under vacuum. The dry material was resuspended in 100 μL of H2O and dried three times to remove residual acid. The residue was dissolved in 1 N NaHCO3 (100 μL). Marfey's reagent (50 μL 10 mg/mL 1-fluoro-2-4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-alanine amide, in acetone) was added to each solution and the reaction mixtures were heated at 80 °C for 5 min. The reactions were quenched by neutralization with 50 μL of 2 N HCl. Aqueous 50 % CH3CN (50 μL) was added to each solution to dissolve the products, which were analyzed by LC/MS (Figures S11-14).

Actinoramide A (1)

[α]23D -8.8 (c 0.26, MeOH); [α]21D -18 (c 0.1, MeOH);15 [α]25D -10.7(c 5.2, MeOH).16

Actinoramide B (2)

25-epi-Actinoramide A (3)

Colorless powder; [α]23D -6.7 (c 0.15, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 204 (4.20), 260 (sh), 268 (sh) nm; IR ν 3377, 2842, 2356, 2349, 1725, 1645, 1385, 1354, 1023 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 2; HRMS m/z 662.3519 [M+H]+ (calcd for C31H48N7O9, 662.3514).

Actinoramide D (4)

Colorless powder; [α]23D -11.5 (c 0.20, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 207 (4.28), 237 (3.81, sh); 260 (sh), 268 (sh) nm; IR ν 3418, 2829, 2362, 2335, 2214, 1723, 1651, 1594, 1381, 1351, 1026 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 2; HRMS m/z 660.3367 [M+H]+ (calcd for C31H46N7O9, 660.3357).

Actinoramide E (5)

Colorless powder; [α]23D -5.1 (c 0.09, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 214(2.19), 232 (1.06, sh) nm; IR ν 3294, 2954, 2923, 2851,1701, 1649, 1529, 1454, 1349 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 2; HRMS m/z 619.3459 [M+H]+ (calcd for C30H46N6O8, 619.3505).

Actinoramide F (6)

Colorless powder; [α]23D -9.87 (c 0.15, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 216(2.31), 232 (1.26, sh), 292 (0.27) nm; IR ν 3292, 2958, 2931, 2875, 1708, 1649, 1529 cm-1; 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 1; 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6), Table 2; HRMS m/z 648.3353 [M+H]+ (calcd for C30H45N7O9, 648.3357).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant U01 TW007404 as part of the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group initiative at the Fogarty International Center (D.H.S., G.T-C. & J.C.), and the Hans W. Vahlteich Professorship (D.H.S.), and at the NIH through the Divisions of Intramural Research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (X.-z. Su) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (J.I.). The authors are grateful to PNG BioNet and the University of Papua New Guinea, Department of Environment and Conservation for permission to collect research samples. We thank P. Shinn (NCATS) for compound management. We also thank S. Carmeli (Tel Aviv University), A. Lowell (UMICH LSI) for his help with the spectroscopic analysis, and R.L. Johnson (NCI) for early support of this work. The Costa Rican marine sediment sample was obtained under the permit R-CM-INBio-82-2009-OT.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: P. falciparum assay 1536-well protocols, performance metrics, NPE retest and EC50 (compounds 1–6) data, Tables S1 – S5, Data Table S1, Figures S1, S9 and S10. Phylogenetic tree relating active S. sp. to other actinoramide producing strains, Figure S2. Degradation and Marfey reaction of compounds 1 and 3, and reduction of 4 to 1, Schemes S1 and S2. NMR and MS data for compounds 1–6, and Figures S3–S8, S11–S15. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DO I: xxxx.

The Authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Koehn FE, Carter GT. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler MS. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:475–516. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer AM, Glaser KB, Cuevas C, Jacobs RS, Kem W, Little RD, McIntosh JM, Newman DJ, Potts BC, Shuster DE. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson EE. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:639–653. doi: 10.1021/cb100105c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz PG, Auld DS, Schultz PJ, Lovell S, Battaile KP, MacArthur R, Shen M, Tamayo-Castillo G, Inglese J, Sherman DH. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1442–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inglese J, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Xia M, Zheng W, Austin CP, Auld DS. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:466–479. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raveh A, Schultz PJ, Aschermann L, Carpenter C, Tamayo-Castillo G, Cao S, Clardy J, Neubig RR, Sherman DH, Sjogren B. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;86:406–416. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.092403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett TN, Paguio M, Gligorijevic B, Seudieu C, Kosar AD, Davidson E, Roepe PD. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1807–1810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1807-1810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbett Y, Herrera L, Gonzalez J, Cubilla L, Capson TL, Coley PD, Kursar TA, Romero LI, Ortega-Barria E. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan J, Cheng KC, Johnson RL, Huang R, Pattaradilokrat S, Liu A, Guha R, Fidock DA, Inglese J, Wellems TE, Austin CP, Su XZ. Science. 2011;333:724–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1205216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan J, Johnson RL, Huang R, Wichterman J, Jiang H, Hayton K, Fidock DA, Wellems TE, Inglese J, Austin CP, Su XZ. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown LE, Chih-Chien Cheng K, Wei WG, Yuan P, Dai P, Trilles R, Ni F, Yuan J, MacArthur R, Guha R, Johnson RL, Su XZ, Dominguez MM, Snyder JK, Beeler AB, Schaus SE, Inglese J, Porco JA., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6775–6780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam SJ, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:6707–6712. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams DE, Dalisay DS, Patrick BO, Matainaho T, Andrusiak K, Deshpande R, Myers CL, Piotrowski JS, Boone C, Yoshida M, Andersen RJ. Org Lett. 2011;13:3936–3939. doi: 10.1021/ol2014494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du YL, Dalisay DS, Andersen RJ, Ryan KS. Chem Biol. 2013;20:1002–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumann CS, Jiang W, Heemstra JR, Jr, Gontang EA, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Chembiochem. 2012;13:972–976. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turk B. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:785–799. doi: 10.1038/nrd2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg DE, Slater AF, Cerami A, Henderson GB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2931–2935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matayoshi ED, Wang GT, Krafft GA, Erickson J. Science. 1990;247:954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.2106161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asai T, Yamamoto T, Shirata N, Taniguchi T, Monde K, Fujii I, Gomi K, Oshima Y. Org Lett. 2013;15:3346–3349. doi: 10.1021/ol401386w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balthaser BR, Maloney MC, Beeler AB, Porco JA, Jr, Snyder JK. Nat Chem. 2011;3:969–973. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlop-Powers Z, Milshteyn A, Brady SF. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;19:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamura T, Matsubara K, Otaka H, Tashiro E, Shindo K, Yanagita RC, Irie K, Imoto M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4377–4385. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNally A, Prier CK, MacMillan DW. Science. 2011;334:1114–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1213920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamura H, Hayakawa M, Iimura Y. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magarvey NA, Keller JM, Bernan V, Dworkin M, Sherman DH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:7520–7529. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7520-7529.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mincer TJ, Jensen PR, Kauffman CA, Fenical W. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5005–5011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5005-5011.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.