Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of endometriosis among adolescent school girls with severe dysmenorrhea.

Methodology

Data was collected via interviewed questionnaire. Patients with symptoms and signs suggestive of endometriosis were further evaluated by abdominal ultrasonography (AUS), serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125). Laparoscopy was done for confirmation in those who agreed. Those who declined laparoscopy were offered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Results

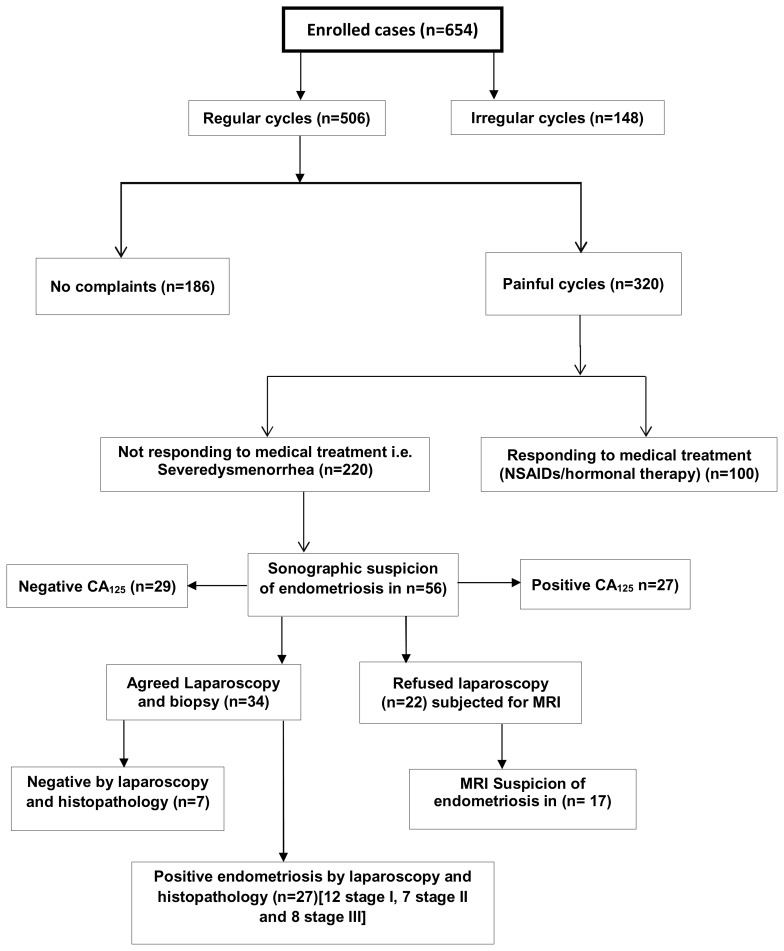

A total number of 654 adolescents were interviewed. Their mean age was 15.2 ± 3.53 SD years. The mean duration of cycles and flow days was 29 ± 8.4 SD and 4 ± 2.8 SD respectively. The age of menarche in years was 13 ± 1.2 SD. Cycles were regular in 77.4 % (n=506) while irregular in 22.6 % (n=148). Of all studied girls, 48.9% (n=320) had menstrual pain of varying degree of severity. Severe dysmenorrhea was reported in 68.8 % (n=220/320) of them. Fifty six of these cases (25.5 %) had ultrasound findings suggestive of endometriosis. CA125 was elevated in 41.5 % (n= 27/56) of them. Patients accepted laparoscopic confirmations were 34, of them 79.4%, (n=27) had positive histo-pathological evidence of endometriosis. MRI was offered to those declined laparoscopy (n=22). Endometriosis was suggested in 77.3% of them.

Conclusion

The study concluded the prevalence of endometriosis in adolescents with severe dysmenorrhea was 12.3 % despite some declined laparoscopy. The unacceptability of laparoscopy and unfeasibility of local examination and trans-vaginal ultrasound add more to the difficulty of diagnosis.

Keywords: Adolescent, endometriosis, severe dysmenorrhea

Introduction

The prevalence of adolescents’ endometriosis appears to be comparable to adults as 35–70% cases presenting with chronic pelvic pain seemed to have pelvic endometriosis on laparoscopy, despite some authors consider it as an underestimated problem in pre or post-menarche girls. (1, 2, 3)

Many theories have been proposed to explain the occurrence of endometriosis but genetic pre-disposition is now evolving and focus has been given on alterations or genetic mutations that may start in utero or in adolescents and young adults. (4) Immune system is postulated by many to have a role in determining who can develop endometriosis, as well as the extent and clinical manifestation of the disease. (5)

Adolescents with the disease are more likely to experience a variety of symptoms which can be safely improved or alleviated by appropriate menstrual management or suppression. (6) However; sometimes cycle pains respond poorly to anti prostaglandins and contraceptive pills and this may be attributed to internal scarring, adhesions, pelvic cysts, chocolate ovarian cysts, bowel obstruction and peritonitis. (7)

The diagnosis of adolescents’ endometriosis is sometimes enigmatic; however, history and clinical examination usually lead the physician to suspect it. (8) The use of AUS and MRI remain an important addition to the non-invasive diagnosis and should be performed before treatment, especially surgical one. (9) On the other hand some biological markers may be used for prediction and treatment follow up in endometriosis, commonly CA125. (10) It goes without saying that laparoscopy with biopsy of the suspicious lesions remains the gold standard for diagnosis as well as management intervention in severe cases. (11)

Adolescent endometriosis is an underestimated health problem particularly in developing countries. Many reasons contribute to this undeniable difficulty in diagnosis. Of these; difficult visiting of gynaecologists by young girls, the unfeasibility of local examination, trans-vaginal ultrasound and diagnostic surgical procedures. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of adolescence endometriosis among school girls with severe dysmenorrhea.

Methods

The study comprised 654 adolescent school girls from 3 different schools covering rural and urban areas in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt during the period of January 2012 to October 2014. The study was approved by the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mansoura College of Medicine and the Institutional Research Ethical Committee. The study was compacted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983.

All participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion. A written questionnaire for screening was designed and translated into simple Arabic language to be handed to all participants. The questionnaire was nameless-coded to collect the data. The codes were used to identify subjects who require intervention. Each participant attended a brief explanation of the research idea and aim of the work.

Sampling procedure: Cluster sampling was used based on geographical contiguity, and then with each subset individual subjects was selected by using simple random sampling. A total of 654 girls were selected which represent 17.2 % of all adolescent girls in the district.

The questionnaire included the following domains: (1) Menstrual pattern; menarche age, duration of the flow, amount of the flow, inter-menstrual bleeding, cycle rhythm and dysmenorrhea, defined as painful cramps that occur with menstruation interfering with patient’s daily activity, (12) type of pain, its duration, relation to the days of the flow, aggravated or stationary with each cycle, does it continue, subside or disappear completely during the inter-menstrual period? aggravated or not by physical exercise, medications given to alleviate, associated bowel or urinary symptoms related to pain time, impact of pain on the patient’s life style”. The severity of pain was assessed by Andrea Mankoski’s pain scale from 0–10. (13) (2) Medications (hormonal or non-hormonal) taken on a regular basis for her complaint. (3) Previous illnesses and surgeries that the patient had related to her complaint. (4) Similar complaint in family members.

Of all interviewed subjects, those found to have intractable pain were offered analgesia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) e.g. Mefenamic Acid and or hormonal therapy (combined oral pills) for 6 months. Those who improved were then excluded; meanwhile those who did not respond to medications were further evaluated by AUS where trans-abdominal scanning by 3–5 MHz convex probe was used with full bladder technique in order to properly visualize the uterus and the ovaries. This is very useful in cases of suspected bladder involvement and abdominal wall endometriosis. The typical ultrasound findings include a cystic mass with diffuse low level echoes varying in appearance depending on the age of the haemorrhage. Again, ovarian endometrioma appearance was based on identification of a cystic mass with diffuse, low-level echoes and/or the presence of punctate echogenicity. (14) Endometrioma can be multilocular with internal thin or thick septations and thick irregular walls. (12) Those with sonographic finding suggestive of endometriosis were investigated by CA125 assay and laparoscopic examination for those who agreed. MRI was offered to those who declined laparoscopy. Laparoscopic staging for positive cases was performed in accordance to American Society of Reproductive Medicine staging of endometriosis (15) and biopsy was taken from all cases for histo-pathological confirmation.

MRI findings in endometriosis depend on the fact that the signal intensity of MRI depends on the contents of the endometrial implants that mainly include the proteins and degraded blood products, the ratio of which varies according to the stage of the haemorrhage and thus the variation in the signal intensity can be noted on MRI images. (15) The acute haemorrhage usually gives hypo-intense (dark) signal on the T1 and T2 weighted images. In contrast the lesions containing degraded blood products like met-haemoglobin, proteins and iron may be seen as hyper-intense (bright) on T1 and hypo-intense (dark) on T2 weighted images. Multiple high signal lesions, usually in the ovaries, on T1-weighted images, also are highly suggestive of endometriosis. MRI imaging features of endometrioma include cystic mass with high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and loss of signal intensity on T2-weighted images. This phenomenon is referred to as “shading” as a result of high protein and iron concentration from recurrent haemorrhage in the endometrioma. (15)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Means of continuous variables were compared between groups using Students-t-test. The associations between categorical variables were assessed by Chi square test. P-values <0.05 were considered to be of statistical significance.

Results

The total number of screened adolescents was 654. Their mean age was 15.2 ± 3.53 SD; age of menarche was 13 ± 1.2 SD. The duration of the cycle was 29 ± 8.4 SD days, duration of the flow 4 ± 2.8 SD days. Regular cycles were reported in 77.4 % (n=506) of all screened girls while the remaining 22.6% (148) had irregular cycles. Painful menses with variable degree of severity were reported in 48.9% (n=320) subjects [table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the adolescent school girls.

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD | 15.2 ± 3.53 years |

| Age of menarche ± SD | 13 ± 1.2 years |

| Duration of the cycle ± SD | 29 ± 8.4 days |

| Duration of the flow ± SD | 4 ± 2.8 days |

| Regular cycle | 506/654 (77.4%) |

| Irregular cycle | 148/654 (22.6%) |

| Family history | 69/654 (10.6%) |

Of patients, who had severe dysmenorrhea were 68.8% (n=220) and did not respond to NSAIDS and hormonal therapy, positive ultrasound picture of endometriosis was reported in 25.4% (n=56). Of these patients 60.7% accepted laparoscopic confirmation, in which 27 had proven endometriosis.

Patients with endometriosis had a significantly higher painful bowel movement and pain at defecation and less likely to be free of symptoms p <0.05 compared to those without endometriosis. Nausea and vomiting, painful urination were similar in occurrence in the two groups [table 2].

Table 2.

Association between menses related disorders and serum level of CA125 in patients suspected for endometriosis (n=56).

| Variable | Subjects with normal level of CA125 (n=29) | Subjects with elevated Serum level of CA125 (n=27) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | 5 (5/56 = 8.9%) | 2 (2/56 = 3.6 %) | 0.5613 |

| Painful urination | 10 (10/56 = 17.9 %) | 5 (5/56 = 8.9 %%) | 0.4614 |

| Painful bowel movement or defecation: | 7 (7/56 = 12.5 %) | 20 (20/56 = 35.7 %) | 0.0465 |

| No associated symptoms | 7 (7/56 = 12.5 %) | 0 | 0.0428 |

p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The association between menses related disorders and serum level of CA125 in patients suspected for enodometriosis (n=56) is shown in table [2]. There was a significant association between patients with a high level of CA125 and painful bowel movement or defecation (p=0.0465). There is no association with increased CA125 and painful urination nausea and vomiting (p>0.05).

The sensitivity and specificity of AUS and CA125 in detecting endometriosis is shown in table [3]. AUS sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV (95% CI) were 100 (87.1–100), 50 (23.12–76.88), 79.4 (62.–91.3), 100 (58.93–100) respectively. The corresponding values for CA125 Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV (954%CI) were 78.8 (69.8–97.4), 89.2 (2.72 – 17.29), 85.2 (66.25 – 95.7), 91.7 (73.4 – 97.8) respectively compared to laparoscopy and biopsy.

Table 3.

Accuracy of AUS, and CA125 compared to laparoscopic biopsy for detection of endometriosis.

| Laparoscopy | Total | Accuracy measure (95%CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| AUS | Positive | 27 | 7 | 34 | Sensitivity | 100 (87.1–100) |

| Negative | 0 | 7 | 7 | Specificity | 50 (23.12–76.88) | |

| PPV | 79.4 (62.–91.3) | |||||

| NPV | 100 (58.93–100) | |||||

| CA125 | Positive | 23 | 4 | 27 | Sensitivity | 78.8 (69.8–97.4) |

| Negative | 3 | 26 | 29 | Specificity | 89.2 (2.72–17.29) | |

| PPV | 85.2 (66.25 – 95.7) | |||||

| NPV | 91.7 (73.4 – 97.8) | |||||

AUS = abdominal ultrasonography.

CA125 = cancer antigen 125

PPV = positive predictive value.

NPV = negative predictive value.

Discussion

The main finding in this study was a relatively low prevalence of endometriosis among adolescence girls with severe dysmenorrhea (12.3%). Their mean age (±SD) was 15.2 ±3.53 years. Painful menses with a variable degree of severity were reported in 48.9% subjects. Of them, 31.3% responded to NSAIDS and hormonal therapy. The decline rate of laparoscopic confirmations was 39.3% (n=22/56).

Strengths in this study included its prospective natures and reasonable number of cases included. Moreover, the prevalence of endometriosis in this age group is understudied. Early treatment for endometriosis in adolescent girls may reduce the long-term complications and improve the quality of life and their reproduction. This study has some weaknesses which included, it was a single centre study, multicentre will be more informative in reflecting the true prevalence rate. Further, due to our limited resources and social constrains we did not investigate all girls by all investigations.

Studies have shown that the estimated prevalence of endometriosis in adolescents varies between 45–70% in those undergoing laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain. (16, 17) Other studies reported a lower prevalence rate ranging between 1–17%. (18) In a systematic review based on 15 selected studies, the prevalence of visually confirmed endometriosis among girls with severe dysmenorrhea was 62%. (19) However the overall prevalence of endometriosis among the adolescent girls as reported by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine classified moderate-severe endometriosis was 32%. (19) This disparity of incidence can be explained by the population studied, the sample size used, and the method of diagnosis whether clinical or surgical. Laparoscopy is the most important procedure used to diagnose endometriosis as there are many other diseases that can cause similar symptoms. In most of the developing world, laparoscopic intervention is hardly accepted by adolescence girls. In this study, the decline rate of laparoscopic confirmations was 39.3% (22/56). This unacceptability of laparoscopic surgery could negatively influence the true rate among this group given a false lower rate as in our study.

In the present study, the mean age of girls was 15.2 ±3.53 years which is not in accordance with other studies in the literature where the average age of diagnosis was 18.24 ±1.48 years. (20) A study from 12 centers in Italy to identify the prevalence of endometriosis evaluated by laparoscopic findings with histological confirmation reported that some patients had their age between 10 and 21 years (17)

Endometriosis can present with acyclic or cyclic pelvic pain or heavy menses. These symptoms are sometimes severe enough to cause school absenteeism or losing other activities.(21, 22) Such important finding has not been evaluated in our study.

In our study, most of the cases suspected by AUS for endometriosis had one or more menses related symptoms. The commonest symptoms were painful bowel movement or defecation 48.2%, followed by painful urination 26.8 % then nausea and vomiting in 12.5% while asymptomatic patients were 12.5%. Our results come in accordance with a New Zealand study evaluating 163 patients with histological confirmation of endometriosis from 2003 to 2009. Authors concluded that, among adolescent patients, the main complaint was dysmenorrhea in 80% versus 55% among adults. (21) Bowel symptoms (rectal pain, painful defecation) and bladder symptoms (e.g. dysuria, urgency, and haematuria) are also common. (24)

Our result supported the evidence that chronic pelvic pain related to endometriosis may respond partially to anti-prostaglandins and oral contraceptive pills, the facts proved by others. (25, 26) In our study, the responds rate to NSAIDS and hormonal therapy was 31.3%. Studies have shown that if these agents are refractory, endometriosis is diagnosable in 50% to 70% of these patients. (24)

In this study, 10.6% of studied subjects reported a positive family history of endometriosis which is consistent with previous studies. (27, 28)

Our study added evidence that ultrasound could be used as an initial screening tool for endometriosis whether trans-abdominal or trans-vaginal, (29) but the non-use of trans-vaginal route in our patients being virgins is considered as one of its limitation. Our results documented AUS sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV (95 %CI) were 100 (87.1 –100), 50 (23.12 –76.88), 79.4 (62.–91.3), 100 (58.93 – 100) respectively. Again trans-rectal one is non-accepted by any of the clients.

MRI is another important radiological addition for non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis especially for young and for detecting small implants.(30) This diagnostic tool was offered to cases who declined laparoscopy, 39.3 % (n=22) of whom 77.3% (n=17) had a picture consistent with endometriosis.

CA125 is often used as a screening test for endometriosis despite some considers levels of interleukin-6 may be a promising one instead.(31) In our study, we found an elevated level of CA125 in 48.2% cases of those who were radiological suspected to have the disease. Moreover, the CA125 level is well correlated with bowel symptoms (p=0.0428). This test showed sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and (95%CI) were 78.8 (69.8 –97.4), 89.2 (2.72 –17.29), 85.2 (66.25 – 95.7), 91.7 (73.4 – 97.8) respectively.

Our research results added an evidence to the opinion stating visual inspection by laparoscopy is still the gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis especially in those who have pelvic pain refractory to simple medical treatments. (18, 32) In our series laparoscopy was done for 34 cases, biopsy was taken from all, 27 had histo-pathological findings of endometriosis. By laparoscopic visualization, 12 cases was staged as stage I disease, 7 cases stage II, and 8 cases stage III.

This study formulated baseline information for future researches in endometriosis among adolescence girls. This study did not answer clearly the situation of endometriosis in the whole country. Further studies are needed to evaluate the treatment offered, patient’s satisfaction and their future fertility.

Conclusion

The study concluded the prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with severe dysmenorrhea was 12.3 % despite some declined laparoscopy. The unacceptability of laparoscopy and the unfeasibility of local examination and trans-vaginal ultrasound are adding more to the difficulty of diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgment

Authors are grateful to all patients and Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology who shared in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors stated that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Laufer MR. Gynecologic Pain: Dysmenorrhea, Acute and Chronic Pelvic Pain, Endometriosis, and Premenstrual Syndrome. In: Emans SJ, Laufer MR, editors. Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology. 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2012. p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farquhar C. Endometriosis. BMJ. 2007 Feb 3;334(7587):249–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39073.736829.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore J, Copley S, Morris J, et al. A systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet/Gynecol. 2002;20:630–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Brosens JJ, et al. Potential role of endometrial stem/progenitor cells in the pathogenesis of early-onset endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014 Jul;20(7):591–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doyle JO, Missmer SA, Laufer MR. The effect of combined surgical-medical intervention on the progression of endometriosis in an adolescent and young adult population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:257. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altshuler AL, Hillard PJ. Menstrual suppression for adolescents. Top of Form Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct;26(5):323–31. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapok Dharmesh, Davila Willy, Laufer MR, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding to conventional therapy. J Pediatr Adolescent Gynecology. 1997;10:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(97)70085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.osayande Amimi s, suarnamehulic Diagnosis and Initial Management of Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Mar 1;89(5):341–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekiesińska-Figatowska M. Magnetic resonance imaging as a non-invasive detection tool for extraovarian endometriosis--own experience. Ginekol Pol. 2014 Sep;85(9):658–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittaway Donald E. The use of serial CA125 concentrations to monitor endometriosis in infertile women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990 Sep;163(3):1032–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91119-w. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(90)91119-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of endometriosis. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(1):225–236. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhoea. BMJ. 2006;332(7550):1134–1138. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7550.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mankoski Pain Scale Copyright © 1995, 1996, 1997. Andrea Mankoski. All rights reserved. Right to copy with attribution freely granted. - reprinted from the newsletter of the Post-Polio Assn of South Florida May 2006. Email: poliowa@upnaway.com.au.

- 14.Bagaria Shalini Jain, Rasalkar Darshana D, Paunipagar Bhawan K. In: Imaging Tools for Endometriosis: Role of Ultrasound, MRI and Other Imaging Modalities in Diagnosis and Planning Intervention, Endometriosis - Basic Concepts and Current Research Trends. Chaudhury Koel., editor. In Tech; 2012. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/endometriosis-basic-concepts-andcurrent-research-trends/role-of-imaging-in-the-diagnosis-of-endometriosis. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Society for Reproductive M. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertility and Sterility. 1997 May;67(5):817–21. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81391-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG. 2009;117(2):185–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vicino M, Parazzini F, Cipriani S, et al. Endometriosis in young women: the experience of GISE. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(4):223–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballweg M. Impact of endometriosis on women’s health: comparative historical data show that the earlier the onset, the more severe the disease. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2004;18(2):201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen EB, Rijkers AC, Hoppenbrouwers K, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013 Sep-Oct;19(5):570–82. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Andres MP, Podgaec S, Carreiro KB, et al. Endometriosis is an important cause of pelvic pain in adolescence. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2014 Nov-Dec;60(6):560–4. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.60.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbas S, Ihle P, Koster I, et al. Prevalence and incidence of diagnosed endometriosis and risk of endometriosis in patients with endometriosis-related symptoms: findings from a statutory health insurance-based cohort in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;160:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harada Tasuku. Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in Young Women. onagoActa Med. 2013 Dec;56(4):81–84. Published online Nov 28, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roman JD. Adolescent endometriosis in the waikato region of New Zealand-a comparative cohort study with a mean follow-up time of 2.6 years. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;50(2):179–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laufer MR, Goitein L, Bush M, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding to conventional therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:199–202. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(97)70085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada T, Momoeda M, Taketani Y, et al. Low-dose oral contraceptive pill for dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Fertile Steril. 2008;90:1583–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seracchioli R, Mabrouk M, Manuzzi L, et al. Post-operative use of oral contraceptive pills for prevention of anatomical relapse or symptom recurrence after conservative surgery for endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2729–2735. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campo S, Campo V, Gambadauro P. Is a positive family history of endometriosis a risk factor for endometrioma recurrence after laparoscopic surgery? Reprod Sci. 2014 Apr;21(4):526–31. doi: 10.1177/1933719113503413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nouri Kazem, Ott Johannes, Krupitz Birgitt, et al. Family incidence of endometriosis in first-, second-, and third-degree relatives: case-control study. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2010;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Exacoustos C, Zupi E, Carusotti C, et al. Staging of pelvic endometriosis: role of sonographic appearance in determining extension of disease and modulating surgical approach. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:378–382. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinkel K, Frei KA, Balleyguier C, et al. Diagnosis of endometriosis with imaging: a review. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:285–298. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seow KM, Lin YH, Hsieh BC, et al. Transvaginal three-dimensional ultrasonography combined with serum CA125 level for the diagnosis of pelvic adhesions before laparoscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:320–326. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busacca M, Vignali M. Ovarian endometriosis: from pathogenesis to surgical treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:321–326. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000084247.09900.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]