Delirium is frequently seen in older patients in the emergency department (ED), is under-recognized, and has potentially serious consequences. 7–17% of older adults who present to the emergency department (ED) suffer from delirium (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). Delirium is a medical emergency with significant associated morbidity and mortality requiring rapid diagnosis and management (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). Patients who have delirium in the ED have increased mortality), increased length of stay in the hospital, and higher risk of functional decline (Han, Eden, et al., 2011; Han, Shintani, et al., 2010). Patients with delirium diagnosed in the ED have a 12-month mortality rate of 10–26%, comparable to patients with sepsis or acute myocardial infarction (Gower, Gatewood, & Kang, 2012).

Despite its seriousness, delirium is missed by ED physicians in 57–83% of cases. (Han et al., 2013; Han et al., 2009). As many as 25% of patients with unrecognized delirium are discharged from the ED (Han et al., 2013; Han et al., 2009). Historically, patients discharged with undetected delirium are nearly three times more likely to die within three months than those in whom delirium is recognized in the ED (Kakuma et al., 2003). Delirious patients discharged from the ED, particularly those with underlying cognitive impairment, are less likely to be able to accurately provide the reason why they were in the ED or to understand their discharge instructions, creating significant potential patient safety hazards (Han, Bryce, et al., 2011). The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Task Force has recommended delirium screening as a key quality indicator for emergency geriatric care (Han et al., 2009), and researchers have identified delirium as a crucial aspect of geriatric emergency medicine requiring additional research (Carpenter et al., 2011).

Managing delirious patients in the ED may pose a significant challenge, particularly if they become agitated. Patients may fall, pull out intravenous catheters or endotracheal tubes, not tolerate necessary invasive therapy, or even become violent, placing themselves and their caregivers at risk for injury (Chevrolet & Jolliet, 2007). The health care team must intervene to ensure the safety of the patient, staff, and other patients while simultaneously evaluating for potential life-threatening etiologies of acute mental status change. In addition, the ED milieu itself can precipitate episodes of delirium in older adults who are not delirious when they initially present (Carpenter et al., 2011), particularly during a lengthy ED stay. Effective management of these episodes may significantly improve patient outcomes, while inappropriate or inadequate treatment can have disastrous consequences.

The goal of our research was to thoroughly review the existing literature in order to develop a novel protocol to improve diagnosis/recognition, management, and disposition of geriatric patients with delirium in the ED.

Mental Status Assessment and Delirium Diagnosis

Recognizing delirium among older adult ED patients is challenging, but it is imperative for effective management. Any patient who is not alert and oriented, who has behavior changes while in the ED, or who appears otherwise altered should be formally assessed for deirium. As mental status assessment depends on the patient’s baseline mental status and the time course of any changes, efforts should be made whenever possible to acquire collateral information from other informants such as family, friends, home health aides, and/or the nursing facility.

Several assessment tools have been developed to assist non-psychiatrists to diagnose delirium (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is the most widely used instrument (Inouye et al., 1990; Wei, Fearing, Sternberg, & Inouye, 2008). The CAM evaluates four cognitive elements: (1) acute onset and fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) altered level of consciousness (Inouye et al., 1990). To be diagnosed with delirium, a patient must demonstrate elements 1 and 2 as well as either 3 or 4 (Inouye et al., 1990). The CAM has been extensively validated in several clinical settings (Inouye et al., 1990; Rolfson, McElhaney, Jhangri, & Rockwood, 1999; Wei et al., 2008). The CAM may be challenging to use routinely in a busy ED, however, as it requires as long as 10 minutes to perform (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). Researchers have recently evaluated in the ED modified, shorter versions of this tool, the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) and the brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) (Han et al., 2014; Han et al., 2013). Both were found to be very specific, with positive tests strongly suggestive of delirium, but with only modest sensitivity (Han et al., 2014; Han et al., 2013). A brief (less than 20 seconds), more sensitive Delirium Triage Screen (DTS) has recently been proposed and evaluated as a preliminary step that may be used in conjunction with the bCAM to increase its sensitivity (Han et al., 2013). Research on these and other tools is ongoing, but a definitive approach for mental status assessment and delirium diagnosis in geriatric ED patients has not yet been identified.

Causes of Acute Delirium

Delirium is rarely caused by a single insult, but, similar to other syndromes in older adults, including falls and failure to thrive, is typically due to the interaction of multiple contributing factors (Wilber, 2006). Researchers have described “predisposing factors” that make the individual more vulnerable to delirium and “precipitating factors,” which are the insults that cause the acute mental disturbance (Inouye & Charpentier, 1996). In the ED, it is important to identify predisposing risk factors and to prevent or ameliorate precipitating factors, as the risk of delirium increases with the number of predisposing and precipitating risk factors present (Wilber, 2006). Therefore, a multicomponent intervention is most likely to be effective for delirium prevention or control (Inouye, 2006).

Management of delirium in the ED requires careful assessment of potential precipitating factors. This includes a complete history and physical, EKG, blood and urine tests, chest x-ray, and consideration of further imaging. ED providers are very familiar with, and experienced in, evaluating for immediately life-threatening delirium triggers such as infection, head trauma, electrolyte disturbance, myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndrome, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, stroke, renal insufficiency, and liver failure. Because there is a substantial body of literature regarding the identification and management of these causes of delirium, they are not discussed in detail here. This review of the literature focuses on the importance of several more subtle precipitating factors, such as pain, urinary retention, constipation, dehydration, environmental distractions, and polypharmacy, that may be more difficult to recognize and treat in the ED setting. These factors are missed by emergency providers because they may not be immediately life-threatening and emergency providers are not trained to routinely check for them in patients with altered mental status.

Pain

Uncontrolled pain is commonly identified as a significant delirium trigger (Schreier, 2010). Patients admitted to the hospital from long-term care who received opioid medications were more likely to experience mild rather than moderate or severe delirium (Schreier, 2010). Among post-operative patients, those who received less effective pain management after hip fracture surgery were more likely to suffer from delirium (Schreier, 2010). Though these studies are correlative rather than causative, they suggest that complete pain assessment and adequate control is relevant for prevention or management of delirium (Nassisi, Korc, Hahn, Bruns, & Jagoda, 2006). Unfortunately, ED physicians are less successful at treating pain in older adults than in younger patients (Hwang, Morrison, Richardson, & Todd, 2011). This is likely partially due to reduced opiate prescribing by ED practitioners because of concerns about side effects, which include sedation and delirium (Hwang et al., 2011). In cases where a patient has severe pain, however, treatment with opioids should be strongly considered (Nassisi et al., 2006), as this may prevent as well as manage delirium. Non-pharmacologic therapies to manage pain, including ice, elevation, and potentially immobilization in the setting of acute injury may be considered. In addition, local or regional drug therapies that manage pain but have minimal systemic effects, such as nerve blocks and epidural catheters, may be considered when appropriate (Hogan et al., 2006).

Urinary Retention

Significant urinary retention can precipitate or exacerbate delirium, a disorder referred to as cystocerebral syndrome (Waardenburg, 2008). Urinary retention from prostatic hypertrophy, other mechanical blockage, or anticholinergic medications is common in elderly ED patients and is under-recognized (Gower, et al., 2012; Thorne & Geraci, 2009; Waardenburg, 2008). Research in geriatric rehabilitation patients has shown that 11–21% of older adults who are asymptomatic are retaining significant amounts of urine (Borrie et al., 2001; Wu & Baguley, 2005). Bladder distension may contribute to delirium due to the increased sympathetic tone and catecholamine surge triggered by the tension on the bladder wall (Liem & Carter, 1991). Bladder scanning via ultrasound has been validated as an accurate measure of retention (Borrie et al., 2001), and one study used a post-void residual (PVR) of 150ml as a threshold for clinically significant retention in a geriatric population (Wu & Baguley, 2005). Bladder decompression via straight catheterization may improve symptoms (Waardenburg, 2008). Whenever possible, placing indwelling urinary catheters should be avoided in delirious older patients (Young, Murthy, Westby, Akunne, & O’Mahony, 2010). Though frequently more convenient for care staff and sometimes requested by patients, these catheters limit patient mobility, are a potential nidus of infection, and have been shown to increase the risk for delirium (Waardenburg, 2008). Therefore, intermittent catheterization is preferable for urinary retention management (Hogan et al., 2006). Critically ill older adults, major trauma victims, and patients undergoing certain surgeries may require indwelling urinary catheters acutely, but these should be removed as soon as clinically indicated (Fakih et al., 2010).

Constipation

Constipation is a frequent, often overlooked precipitating factor for delirium (Morley, 2007). Research suggests that 17–40% of adults aged over 65 may have chronic constipation, with as many as 45% of frail older adults suffering from it (Morley, 2007). Research in skilled nursing facilities finds that 47% of residents have constipation and 50% take daily laxatives (Tariq, 2007). Notably, constipation is associated with verbal and physical aggression in nursing home patients with dementia (Leonard, Tinetti, Allore, & Drickamer, 2006). Constipation may be caused by many factors, including immobility, co-morbid diseases such as diabetes mellitus or colon cancer, electrolyte abnormalities, medications, and even depression (Morley, 2007). A frequent cause of constipation is opioid pain medication. Although it is important not to withhold opioid analgesics, all patients receiving opiates should prophylactically be given a stool softener unless a contraindication exists (Ross & Alexander, 2001). A careful history and physical, including a rectal examination with consideration of disimpaction, may also be helpful in assessing and managing delirious patients.

Dehydration

Dehydration is a common precipitating factor for delirium, in part because it leads to cerebral hypoperfusion (Wilson & Morley, 2003). Dehydration in older adults is often related to acute illness and results in high mortality (George & Rockwood, 2004). Dehydration may have many causes, including decreased thirst mechanism, physical limitations causing inability to access water, swallowing difficulty, cognitive impairment, and misuse of diuretics (George & Rockwood, 2004). In addition, severe dehydration may indicate substandard care or neglect (George & Rockwood, 2004). Recognition of dehydration in the ED can be challenging, as the physical signs of dehydration, such as weight loss, decreased skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, and hypotension, which are very useful in assessing younger adults, are unreliable in geriatric patients (George & Rockwood, 2004). As a result, a BUN/Creatinine ratio of 18 or greater has been suggested by researchers as a threshold for identification and aggressive treatment of dehydration in delirious elderly patients (Chu et al., 2011; Marcantonio et al., 2006).

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors also contribute to the development of delirium. The cacophonous, chaotic, unfamiliar, and potentially threatening environment of the ED may be stressful and disorienting for geriatric patients (Carpenter et al., 2011). As sensory overload has been shown to worsen delirium, providers should consider moving at-risk patients out of the busy ED corridors into quieter, more controlled settings (Dahlke & Phinney, 2008). In most EDs, however, patients are less closely observed if removed from the hallway, so the potential benefits and risks must be weighed. An uncomfortable temperature may also worsen delirium, so providers should consider adjusting the climate and adding/removing blankets as needed (Conley, 2011; Gillis & MacDonald, 2006). Immobility is another important environmental risk factor for delirium (Rigney, 2006). Minimizing intravenous lines, wires, and monitors, which may reduce mobility, is recommended (Rigney, 2006). Frequent checks should be made to ensure that patients have not become tethered to devices or tangled in bed-sheets or blankets. A soiled incontinence brief may also increase stress and disorientation for a delirious older adult and increases risk of urinary tract infection and super-infection of existing pressure ulcers, potentially worsening delirium. Therefore, every effort should be made to change to a clean brief when appropriate.

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is very common among older adults and frequently contributes to delirium (Wilber, 2006). Older patients presenting to the ED take an average of 4.2 medications per day, with 91% taking at least 1, 13 % taking 8 or more, and some taking as many as 17 (Samaras, Chevalley, Samaras, & Gold, 2010). Of these patients, 31% have been prescribed a combination of medications that may lead to at least one potentially adverse drug interaction (Hohl, Dankoff, Colacone, & Afilalo, 2001). The Beers criteria alert clinicians about medications that, due to potentially dangerous side effects, are inappropriate for older adults (Campanelli, 2012). Despite the existence of these criteria, Chin and colleagues found that 11% of elderly patients presenting to the ED have been prescribed at least 1 of the medications deemed inappropriate by Beers and colleagues (Chin et al., 1999). Compounding this problem, Chin and colleagues also found that medications identified by the Beers List as inappropriate were given to 3.6% of elderly patients in the ED and prescribed to 5.6% upon ED discharge (Chin et al., 1999). The medications most frequently linked to delirium among older adults are those with anticholinergic properties (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). The types of medications commonly associated with delirium among older adults are described in Table 1. The effects of polypharmacy may be magnified during acute illness, with hepatic or renal dysfunction unexpectedly increasing the half-life and, therefore, the effect of medications. A complete medication history and careful consideration of medications and doses given in the ED is an essential part of delirium management.

Table 1.

Medications Most Commonly Associated with Delirium

| Medications with Anticholinergic Properties |

| antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine) |

| antispasmodics (such as oxybutynin) |

| antiemetics |

| antiparkinsonian drugs |

| antipsychotics* |

| Other Psychoactive Medications |

| benzodiazepines |

| anticonvulsants |

| narcotic pain medications** (particularly meperidine) |

| Non-Psychoactive Medications |

| digoxin |

| beta-blockers |

| corticosteroids |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents |

| antibiotics |

Though antipsychotic medications are often used to treat delirium, these medications have anticholinergic properties and may cause or worsen existing delirium.

Though very important for pain control and prevention of pain-induced delirium, narcotics may paradoxically themselves contribute to delirium.

Sources:

Campanelli, C. M. (2012). American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(4), 616.

Han, J. H., Wilson, A., & Ely, E. W. (2010). Delirium in the older Emergency Department patient–A quiet epidemic. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 28(3), 611–631.

Hogan, D. B., Gage, L., Bruto, V., Burne, D., Chan, P., & Wiens, C. (2006). National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health—The assessment and treatment of Delirium. Canadian Journal of Geriatrics, 9(Suppl 2), 542–551.

Management Strategies

Practice guidelines emphasize that most episodes of delirium can be managed with non-pharmacological interventions and that pharmacologic treatment be limited to behavioral emergencies when a patient’s severe agitation is interfering with essential investigations or treatment or placing them or others at risk (Hogan et al., 2006). Despite this, there is currently no universally accepted strategy for managing a delirious patient in the ED (Han et al., 2009). In fact, there is significant variation in hospitalized inpatient management of delirium, with many established treatments remaining underused and most recommended management strategies based on common sense rather than empirical evidence. (Carnes et al., 2003; Pitkala, Laurila, Strandberg, & Tilvis, 2006)

Non-Pharmacologic Management

Non-pharmacologic management recommendations include strategies for effectively communicating with a delirious patient, which may be challenging given these patients’ fluctuations in mental status and difficulties in sustaining attention. Each time a nurse or physician interacts with a delirious older adult, he/she should provide orienting information, reminding the patient where he/she is, the date and time, and what is happening to him/her (Aguirre, 2010). Addressing the patient face-to-face, with instructions and explanations that are slow-paced, short, simple, and repeated helps manage delirium (Hogan et al., 2006). Interpreters should be used if there is any concern that the patient may have difficulty understanding the language (Tropea, Slee, Brand, Gray, & Snell, 2008). Nurses and physicians should keep their hands in sight whenever possible and avoid gestures or rapid movements or touching the older person in an attempt to redirect him/her, because these actions may trigger an episode of agitation (Hogan et al., 2006).

Sensory impairment is a frequent contributor to delirium, worsening disorientation and making communication difficult (Hogan et al., 2006). Many older adults have vision or hearing problems, and the eyeglasses and hearing aids they regularly use should be available and worn when possible (Aguirre, 2010). In addition, the use of magnifying glasses and portable amplifying devices in the ED may be helpful for patients with severe sensory impairment (Aguirre, 2010).

Providers may request that family members and friends, if available, stay with the older person (Aguirre, 2010). Family and friends can assist with communication and reorientation (Hogan et al., 2006). Also, they may calm, aid, protect, support, and advocate for the patient (Hogan et al., 2006). ED providers may facilitate this by placing the patient in a large enough room to accommodate family members and bringing chairs to the bedside.

Environmental strategies may also be useful in managing delirium. Though frequently challenging in a crowded ED, reducing noise near a patient may prevent the sensory overload that can exacerbate delirium (Young et al., 2010). Large, easily visible clocks and calendars may help reorient patients, as may white boards displaying names of staff members and the day of the week (Aguirre, 2010). Low lighting to allow rest is ideal (Hogan et al., 2006; Young et al., 2010), but total darkness may prevent an older adult from perceiving the environment correctly and reorienting him/herself if he/she awakens (Rigney, 2006). In fact, use of nightlights has been recommended to reduce anxiety associated with waking up in unfamiliar surroundings (Rigney, 2006). The disorienting “timelessness” of an often windowless hospital environment is confusing and interrupts older adults’ sleep-wake cycles. Therefore, lighting changes to cue night and day may be helpful.

Physical restraints should be avoided with agitated delirious older adults, as their use may increase agitation and prolong delirium (Evans & Cotter, 2008). Notably, in one study, restraint use among patients in a medical inpatient unit was associated with a three-fold increased odds of delirium persistence at time of discharge (Inouye et al., 2007). In addition, physical restraints create additional clinical problems, such as loss of mobility, pressure ulcers, incontinence, and they increase the chance of serious injury or death (Evans & Cotter, 2008). With anticipated healthcare changes, including worsening ED overcrowding, budgetary cutbacks, nursing shortages, and decreased availability of 1:1 sitters, commentators are concerned about a potential resurgence of restraint use (Inouye et al., 2007). Raising the head and foot of the bed to prevent climbing or falling out may be a safer alternative (Somes, Donatelli, & Barrett, 2010).

The busy, crowded ED, where physicians and nurses are frequently responsible for multiple acutely sick patients, is a challenging environment in which to employ these strategies. Nevertheless, it is important for ED providers to consider using them whenever possible. Unfortunately, all studies to date evaluating their use involve patients in hospital wards or in rehabilitation facilities, and not in EDs. Additional research is required to determine which non-pharmacologic interventions are feasible and cost-effective in the ED (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010).

Pharmacologic Management

In some circumstances, an older adult’s severe agitation may require emergent medication intervention to ensure their safety as well as that of other patients and staff. Despite the recommendation that medication be used only as a last resort, literature suggests that use is widespread, with the majority of delirious hospitalized patients receiving pharmacologic intervention (Briskman, Dubinski, & Barak, 2010). Additional education regarding the efficacy of non-pharmacologic management techniques may be required to change this.

After attempting non-pharmacologic management, care should be taken in selecting pharmacologic approaches to treating delirium. Though benzodiazepines are commonly used to treat delirium in younger adults, guidelines recommend that these medications be avoided as monotherapy unless treating delirium due to alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal (Trzepacz et al., 1999). In older adults, benzodiazepines may precipitate or worsen delirium, and can cause severe side effects, including over-sedation, disinhibition, ataxia, and confusion (Pandharipande et al., 2006).

International guidelines suggest that providers instead use antipsychotic medications to treat behavioral emergencies in geriatric delirium (Trzepacz et al., 1999). These medications include haloperidol, a typical antipsychotic, and newer, atypical antipsychotics including olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. Despite the routine use of these antipsychotic medications for delirious older adults in many EDs, there is little reliable evidence supporting their efficacy or safety (Devlin & Skrobik, 2011; Flaherty, Gonzales, & Dong, 2011). Larger studies with rigorous methodology are needed in order to accurately assess the efficacy of the different pharmacologic approaches to treating geriatric delirium (Flaherty et al., 2011; Ozbolt, Paniagua, & Kaiser, 2008). As with most medication interventions in older adults, providers should always “start low and go slow,” as additional medication may always be given but it cannot be taken away (Tobias, 2003). Unfortunately, research suggests that delirious geriatric patients are frequently started on high doses, and the medication orders are only rarely reviewed (Tropea, Slee, Holmes, Gorelik, & Brand, 2009).

Disposition

Though little evidence-based guidance exists for disposition of older ED patients with delirium, most of these patients likely require hospital admission. For patients who are admitted, admission to a unit specializing in acute geriatric care may improve outcomes (Naughton et al., 2005).

Novel Clinical Protocol

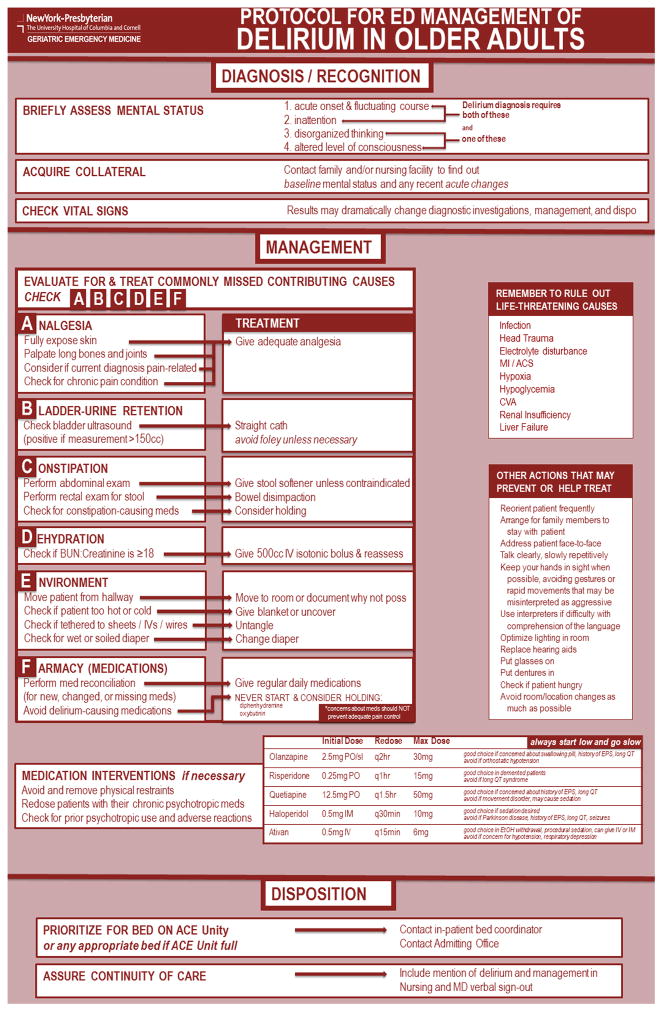

Based on this literature review, we have developed a novel clinical protocol for diagnosis/recognition, management, and disposition of geriatric delirium in the ED (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Novel clinical protocol for emergency department management of delirium in older adults

Reprinted with permission from the authors

Diagnosis/Recognition

Our protocol emphasizes the use of a formal mental status assessment tool for at-risk patients. In addition, it asks providers to acquire collateral information from family or a nursing facility whenever possible, as baseline mental status and time course of behavior change significantly affect assessment. Providers are also reminded that it is important to check vital signs immediately if any mental status change is suspected because of their implications for underlying etiology and subsequent testing, management, and disposition.

Management

Emergency providers are experienced and comfortable with assessment and management of immediately life-threatening conditions that may precipitate agitated delirium, such as sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, or hypoglycemia. Our protocol reminds providers to initially check for these conditions.

The central focus of this protocol, however, is on reminding the ED provider about the importance of assessing for additional commonly missed contributing precipitants of delirium in older adults as well as to provide specific interventions to treat these precipitants. To assist providers with remembering these contributing causes, we developed a mnemonic, A-B-C-D-E-F (A=analgesia, B=bladder/urinary retention, C=constipation, D=dehydration, E=environment, F=f(ph)armacy/medications). For each of these potentially missed contributing causes, we have developed critical action(s) in evaluation and treatment. For A=analgesia (poor pain control): fully expose skin, palpate long bones and joints, consider if acute complaint is pain-related, and check for a chronic pain condition. If pain is found: intervene with adequate analgesia. For B=bladder/urinary retention: check the bladder with ultrasound, and, if measurement is greater than 150 mL: empty the bladder using a straight urinary catheter. For C=constipation: perform a rectal exam, consider disimpaction, and check for and potentially hold constipation-causing medications. For D=dehydration: check BUN:Creatinine ratio and, if it is 18 or greater, give a 500 mL bolus of isotonic intravenous fluid, if not contraindicated, and reassess. For E=environment: check if the patient is in a noisy hallway, is too hot or cold, is tethered to sheets/IVs/wires, or has a wet or soiled brief, and address each as appropriate. For F=f(ph)armacy: perform a reconciliation for new, changed, or missing medications and avoid prescribing delirium-causing medications.

In addition to the critical A-B-C-D-E-F evaluation of commonly missed factors that can contribute to delirium, our protocol also suggests other non-pharmacologic actions that providers may take to prevent or help treat delirium.

Pharmacologic Interventions

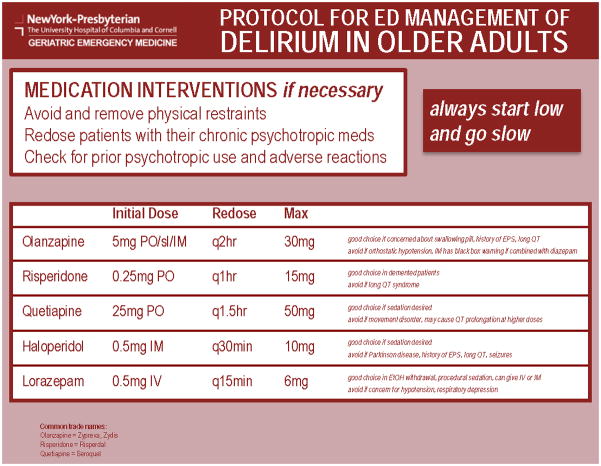

The protocol acknowledges that medication intervention to manage delirium-related behaviors may be necessary to ensure the safety of the patient and staff but encourages providers to use it only as a last resort. As well, the protocol emphasizes the avoidance of physical restraints. We recommend that providers first re-dose patients with their current psychotropic medications and, if possible, check their records for prior psychotropic use and adverse reactions.

Despite a literature review yielding limited evidence, we have provided a chart of various medication alternatives with recommended dosing and circumstances in which each medication may be beneficial or deleterious choice. (Figure 2) Olanzapine, which is available in sublingual form in addition to oral and intramuscular (IM), is a good choice if a practitioner is concerned about a patient’s ability to swallow a pill. Also, olanazapine is appropriate for individuals with a history of extrapyramidal symptoms or evidence or concern for prolonged QT interval (Bhana, Foster, Olney, & Plosker, 2001; Chung & Chua, 2011). Given this side effect profile, olanzapine is often an appropriate first choice in the elderly ED patient. Olanzapine should be avoided in those at risk for orthostatic hypotension (Escobar et al., 2008). Evidence suggests an increased risk of sudden death when IM olanzapine is used in combination with diazepam (Allen, Currier, Carpenter, Ross, & Docherty, 2005).

Figure 2.

Recommended medication interventions for emergency department management of delirium in older adults

Reprinted with permission from the authors

Risperidone, though it is an unfamiliar medication to many emergency providers, may be a particularly good choice for patients with underlying dementia complicating their acute delirium (Alexopoulos, Streim, Carpenter, & Docherty, 2004). Risperidone is commonly used in skilled nursing facilities to manage agitated behaviors. Of the atypical antipsychotics, risperidone has the highest likelihood for dangerous QT interval prolongation, however, so should be avoided in at-risk patients (Chung & Chua, 2011).

Quetiapine is an appropriate choice if sedation is desired (Devlin et al., 2010) and may be appropriate for patients with significant acute medical illness who will require ICU-level care. Quetiapine should be avoided in those with a known movement disorder (Rizos, Douzenis, Gournellis, Christodoulou, & Lykouras, 2009; Walsh & Lang, 2011), however, and it may prolong the QT interval at higher doses, so providers should be wary of using quetiapine in conjunction with other QT prolonging drugs (Aghaienia, Brahm, Lussier, & Washington, 2011).

Haloperidol, commonly used in the emergent management of agitated younger patients, is the medication that has been most well-studied for use in delirious older adults (Han, Wilson, & Ely, 2010). Haloperidol may be useful in situations where sedation is required (Attard, Ranjith, & Taylor, 2008) and may be given intravenously in emergent situations. Haloperidol, however is potentially dangerous for many patients, as this medication is associated with increased incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, seizures, Parkinsonism, and a prolonged QT (Angelini, Ketzler, & Coursin, 2001). Many of these side effects may be avoided with lower doses, so haloperidol should likely be used for older adult ED patients in much smaller doses than typically given to younger patients.

Lorazepam and other benzodiazepines, which may cause paradoxical delirium, are typically discouraged for use in delirious older adults, particularly for those at risk for respiratory depression or hypotension (Pandharipande et al., 2006). In limited situations, however, such as delirium due to alcohol withdrawal and sedation for an ED procedure or radiologic test, lorazepam may be an appropriate choice (Gower et al., 2012; Trzepacz et al., 1999). As with the use of most medications in older adults, we emphasize starting low and going slow. If an emergency practitioner is unfamiliar with use of these medications, consultation with a geriatrician is also recommended.

Disposition

Safe disposition is imperative for older adults suffering from delirium, and the ED is not an appropriate environment for these patients. Therefore, in our protocol, these patients are prioritized for transfer to inpatient units, particularly units specializing in the care of geriatric patients, where they can receive definitive care. Also, to ensure continuity of care, our protocol requires that both the ED nurse and physician verbally report to the in-patient team that the patient is delirious and how this condition has been managed as part of the transfer of care.

Conclusion

Assessing and managing agitated delirium in older adults remains a significant challenge for ED providers. We have synthesized existing literature into an evidence-based, comprehensive, A-B-C-D-E-F protocol that addresses many of the factors precipitating delirium and both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches to manage them. Future research involves implementing this protocol and measuring its efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the American Federation of Aging Research (AFAR), which provided the funding for Scott Connors’ participation through its Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) fellowship program. Dr. Mark Lachs is the recipient of a mentoring award in patient-oriented research from the National Institute on Aging (K24 AG022399).

Footnotes

Titles of Authors:

Tony Rosen MD MPH: Geriatric Emergency Medicine Fellow, Instructor in Medicine

Scott Connors BS: Medical Student

Sunday Clark MPH ScD: Director of Research

Alexis Halpern MD: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Assistant Director of Geriatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship

Michael E. Stern MD: Assistant Professor of Medicine, Co-Director of Geriatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship

Jennifer DeWald RN: Director of Emergency Nursing Education

Mark S. Lachs MD MPH, Co-chief, Division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine

Neal Flomenbaum MD, Emergency Physician-in-Chief

References

- Aghaienia N, Brahm NC, Lussier KM, Washington NB. Probable quetiapine-mediated prolongation of the QT interval. Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2011;24(5):506–512. doi: 10.1177/0897190011415683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre E. Delirium and hospitalized older adults: a review of nonpharmacologic treatment. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2010;41(4):151. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100326-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Streim JE, Carpenter D, Docherty JP. Expert consensus guidelines for using antipsychotic agents in older patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 2):1–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MH, Currier GW, Carpenter D, Ross RW, Docherty JP. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of behavioral emergencies 2005. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11:5–108. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200511001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini G, Ketzler JT, Coursin DB. Use of propofol and other nonbenzodiazepine sedatives in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Clinics. 2001;17(4):863–880. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard A, Ranjith G, Taylor D. Delirium and its treatment. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(8):631–644. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana N, Foster RH, Olney R, Plosker GL. Olanzapine. Drugs. 2001;61(1):111–161. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrie MJ, Campbell K, Arcese ZA, Bray J, Hart P, Labate T, Hesch P. Urinary retention in patients in a geriatric rehabilitation unit: prevalence, risk factors, and validity of bladder scan evaluation. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2001;26(5):187–191. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2001.tb01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briskman I, Dubinski R, Barak Y. Treating delirium in a general hospital: a descriptive study of prescribing patterns and outcomes. International Psychogeriatrics. 2010;22(2):328. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanelli CM. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults: The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(4):616. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes M, Howell T, Rosenberg M, Francis J, Hildebrand C, Knuppel J. Physicians vary in approaches to the clinical management of delirium. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(2):234–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, Heard K, Gerson LW, Miller DK. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine: prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2011;66(7):775–783. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevrolet JC, Jolliet P. Clinical review: agitation and delirium in the critically ill: significance and management. Critical Care. 2007;11(3):214. doi: 10.1186/cc5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, Mulliken R, Walter J, Hayley DC, Karrison TG, Nerney MP, Miller A, Friedmann PD. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1999;6(12):1232–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CL, Liang CK, Lin YT, Chow PC, Pan CC, Chou MY, Lu T. Biomarkers of delirium: Well evidenced or not? Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2011;2(4):100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chung AK, Chua SE. Effects on prolongation of Bazett’s corrected QT interval of seven second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2011;25(5):646–66. doi: 10.1177/0269881110376685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley DM. The gerontological clinical nurse specialist’s role in prevention, early recognition, and management of delirium in hospitalized older adults. Urologic Nursing. 2011;31(6):337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlke S, Phinney A. Caring for hospitalized older adults at risk for delirium: the silent, unspoken piece of nursing practice. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2008;34(6):41–47. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080601-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JW, Roberts RJ, Fong JJ, Skrobik Y, Riker RR, Hill NS, Robbins T, Garpestad E. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: A prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(2):419–427. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9e302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JW, Skrobik Y. Antipsychotics for the prevention and treatment of delirium in the intensive care unit: what is their role? Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2011;19(2):59–67. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.565247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar R, San L, Perez V, Olivares JM, Polavieja P, Lopez-Carrero C, Montoya A. Effectiveness results of olanzapine in acute psychotic patients with agitation in the emergency room setting: results from NATURA study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36(3):151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LK, Cotter VT. Avoiding restraints in patients with dementia: understanding, prevention, and management are the keys. American Journal of Nursing. 2008;108(3):40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000311827.75816.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakih MG, Pena ME, Shemes S, Rey J, Berriel-Cass D, Szpunar SM, Savoy-Moore RT, Saravolatz LD. Effect of establishing guidelines on appropriate urinary catheter placement. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(3):337–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty JH, Gonzales JP, Dong B. Antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium in older hospitalized adults: a systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(s2):S269–S276. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Rockwood K. Dehydration and Delirium—Not a Simple Relationship. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2004;59(8):M811–M812. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.8.m811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AJ, MacDonald B. Unmasking delirium. The Canadian Nurse. 2006;102(9):18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower LE, Gatewood MOK, Kang CS. Emergency department management of delirium in the elderly. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2012;13(2):194. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.10.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Bryce SN, Ely E, Kripalani S, Morandi A, Shintani A, Jackson JC, Storrow AB, Dittus RS, Schnelle J. The effect of cognitive impairment on the accuracy of the presenting complaint and discharge instruction comprehension in older emergency department patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2011;57(6):662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Eden S, Shintani A, Morandi A, Schnelle J, Dittus RS, Storrow AB, Ely EW. Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(5):451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S, Morandi A, Solberg LM, Schnelle J, Dittus RS, Storrow AB, Ely EW. Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6 months. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2010;56(3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Wilson A, Ely EW. Delirium in the older Emergency Department patient–A quiet epidemic. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2010;28(3):611–631. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ, Shintani A, Schnelle JF, Dittus RS, Powers JS, Vernon J, Storrow AB, Ely EW. Validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit in older Emergency Department patients. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014;21(2):180–187. doi: 10.1111/acem.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani A, Schnelle JF, Dittus RS, Graves AJ, Storrow AB, Shuster J, Ely EW. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2013;62(5):457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, Schnelle J, Morandi A, Dittus RS, Storrow AB, Ely EW. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(3):193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DB, Gage L, Bruto V, Burne D, Chan P, Wiens C. National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health—The assessment and treatment of Delirium. Canadian Journal of Geriatrics. 2006;9(Suppl 2):542–551. [Google Scholar]

- Hohl CM, Dankoff J, Colacone A, Afilalo M. Polypharmacy, adverse drug-related events, and potential adverse drug interactions in elderly patients presenting to an emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2001;38(6):666–671. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.119456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang U, Morrison RS, Richardson LD, Todd KH. A painful setback: misinterpretation of analgesic safety in older adults may inadvertently worsen pain care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(12):1127–1127. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(11):1157–1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, Cooney LM., Jr A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(9):669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons: predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(11):852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method, a new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Jones RN, Kiely DK, Yang F, Marcantonio ER. Risk factors for delirium at discharge: development and validation of a predictive model. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(13):1406–1413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma R, Fort D, Galbaud G, Arsenault L, Perrault A, Platt RW, Monette J, Moride Y, Wolfson C. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(4):443–450. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Jung IK, Han C, Cho SH, Kim L, Kim SH, Lee BH, Lee HJ, Kim YK. Antipsychotics and dopamine transporter gene polymorphisms in delirium patients. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2005;59(2):183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KU, Won WY, Lee HK, Kweon YS, Lee CT, Pae CU, Bahk WM. Amisulpride versus quetiapine for the treatment of delirium: a randomized, open prospective study. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;20(6):311–314. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard R, Tinetti ME, Allore HG, Drickamer MA. Potentially modifiable resident characteristics that are associated with physical or verbal aggression among nursing home residents with dementia. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(12):1295–1300. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.12.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem PH, Carter WJ. Cystocerebral syndrome: a possible explanation. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1991;151(9):1884–1886. doi: 10.1001/archinte.151.9.1884a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcantonio ER, Rudolph JL, Culley D, Crosby G, Alsop D, Inouye SK. Serum Biomarkers for Delirium. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61(12):1281–1286. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. Constipation and irritable bowel syndrome in the elderly. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2007;23(4):823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassisi D, Korc B, Hahn S, Bruns J, Jagoda A. The evaluation and management of the acutely agitated elderly patient. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2006;73(7):976–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton BJ, Saltzman S, Ramadan F, Chadha N, Priore R, Mylotte JM. A multifactorial intervention to reduce prevalence of delirium and shorten hospital length of stay. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(1):18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbolt LB, Paniagua MA, Kaiser RM. Atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of delirious elders. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2008;9(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, Pun BT, Wilkinson GR, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkälä KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61(2):176–181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigney TS. Delirium in the hospitalized elder and recommendations for practice. Geriatric Nursing. 2006;27(3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizos E, Douzenis A, Gournellis R, Christodoulou C, Lykouras LP. Tardive dyskinesia in a patient treated with quetiapine. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):54–57. doi: 10.1080/15622970701362550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson DB, McElhaney JE, Jhangri GS, Rockwood K. Validity of the Confusion Assessment Method in detecting postoperative delirium in the elderly. International Psychogeriatrics. 1999;11(04):431–438. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299006043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DD, Alexander CS. Management of common symptoms in terminally ill patients: Part II. Constipation, delirium and dyspnea. American Family Physician. 2001;64(6):1019–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, Gold G. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2010;56(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier AM. Nursing care, delirium, and pain management for the hospitalized older adult. Pain Management Nursing. 2010;11(3):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small JG, Hirsch SR, Arvanitis LA, Miller BG, Link CG. Quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia: a high-and low-dose double-blind comparison with placebo. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(6):549–557. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180067009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somes J, Donatelli NS, Barrett J. Sudden confusion and agitation: causes to investigate! Delirium, dementia, depression. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2010;36(5):486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq SH. Constipation in long-term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2007;8(4):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne MB, Geraci SA. Acute urinary retention in elderly men. American Journal of Medicine. 2009;122(9):815–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias DE. Start low and go slow. Hospital Pharmacy. 2003;38(7):634–636. [Google Scholar]

- Tropea J, Slee J, Holmes ACN, Gorelik A, Brand CA. Use of antipsychotic medications for the management of delirium: an audit of current practice in the acute care setting. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(01):172–179. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea J, Slee JA, Brand CA, Gray L, Snell T. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of delirium in older people in Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2008;27(3):150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzepacz P, Breitbart W, Franklin J, Levenson J, Martini DR, Wang P. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waardenburg IE. Delirium caused by urinary retention in elderly people: a case report and literature review on the “cystocerebral syndrome. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(12):2371–2372. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RA, Lang AE. Early-onset tardive dyskinesia in a neuroleptic-naive patient exposed to low-dose quetiapine. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(12):2297–2298. doi: 10.1002/mds.23831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(5):823–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilber ST. Altered mental status in older emergency department patients. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2006;24(2):299–316. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MG, Morley JE. Impaired cognitive function and mental performance in mild dehydration. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;57:S24–S29. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Baguley IJ. Urinary retention in a general rehabilitation unit: prevalence, clinical outcome, and the role of screening. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86(9):1772–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J, Murthy L, Westby M, Akunne A, O’Mahony R. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium: summary of NICE guidance. Brtish Medical Journal. 2010:341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]