Abstract

Background

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is intended to provide a framework for increasing health care access for vulnerable populations, including the 1.2 million who experience homelessness each year in the US.

Objective

We sought to characterize homeless persons’ knowledge of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), identify barriers to their ACA enrollment, and determine access to various forms of communication that could be used to facilitate enrollment.

Methods

At an urban county Level 1 trauma center, we interviewed all non-critically ill adults who presented to the emergency department (ED) during daytime hours and were able to provide consent. We assessed access to communication, awareness of the ACA, insurance status, and barriers preventing subjects from enrolling in health insurance and compared homeless persons’ responses with concomitantly enrolled housed individuals.

Results

Of the 650 enrolled subjects, 134 (20.2%) were homeless. Homeless subjects were more likely to have never heard of the ACA (26% vs 10%). “Not being aware if they qualify for Medicaid” was the most common (70%) and most significant (30%) barrier to enrollment reported by uninsured homeless persons. Of homeless subjects who were unsure if they qualified for Medicaid, 91% reported an income under 138% of the federal poverty level, likely qualifying them for enrollment. While 99% of housed subjects reported access to either phone or internet, only 74% of homeless subjects reported access.

Conclusions

Homeless persons report 1) having less knowledge of the ACA than their housed counterparts, 2) poor understanding of ACA qualification criteria, and 3) limited access to phone and internet. ED based outreach and education regarding ACA eligibility may increase their enrollment.

Keywords: Emergency Medicine, Emergency Department, Homeless, Health Insurance, Affordable Care Act, ACA, Access to Care, Uninsured, Underinsured, Managed Care, Health Systems, Health Disparities, Health Policy, Medicare, Utilization

INTRODUCTION

Homeless persons are a medically vulnerable population with a high burden of disease and an average life expectancy of only 41–47 years compared to the national average of 78 years.1, 2 Lack of health insurance in this population leads to their greater use of the Emergency Department (ED) often as their only health care access point, which in turn may contribute to ED overcrowding and higher overall costs of care. 3, 4

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted at the start of 2014 and is intended to provide a framework for increasing health care access for vulnerable populations, including the 1.2 million who experience homelessness each year in the US. 5, 6, 7 Opening the door to clinics and other health care access options outside of the ED, the ACA may offload the ED directly.1 It may also indirectly affect homeless persons’ presentations to the ED by improving access to primary care and preventive care services.1, 3, 8

Any potential benefits of the ACA on improving health care access and outcomes for homeless persons and decreasing use of the ED, however, require that individuals actually enroll in the program and acquire health insurance coverage. Even before the widely publicized ACA, Healthcare for the Homeless reported that 10–50% of their homeless clients were eligible for Medicaid but had not enrolled.9 The reason(s) for homeless persons’ non-enrollment have not been clearly delineated—it is possible that many of them simply have not heard of the ACA and opportunities for acquiring health care coverage.8–10

Marginalization and lack of continuity of care make the homeless population a difficult group to assess from an overall medical needs and public health standpoint.5–8 Serving as their central (and often only) health care access site, the ED is uniquely suited to evaluate their health care knowledge and needs during real-time presentations.3, 10 The objectives of this ED cross-sectional study were to 1) characterize homeless persons’ knowledge of the ACA, 2) identify barriers to ACA enrollment, and 3) assess their access to various forms of communication that could be used to facilitate their enrollment. We compared these assessments of homeless persons with concomitantly enrolled housed individuals.

METHODS

Study Design, Participants, and Setting

We conducted this cross-sectional survey-based study at an urban county ED, [blinded for peer review], during a 10-week period (June to August 2014). During these ten weeks all adult patients in treatment areas of the ED between 9AM and 5PM Monday through Friday were considered for enrollment. We excluded patients with any of the following from the survey: 1) intoxication; 2) altered mental status; 3) critical injury or critical illness; 4) incarceration; 5) psychiatric holds; 6) under the age of 18; 7) inability to understand an English-language survey; and 8) temporary visitation from another country. We obtained institutional review board approval prior to study initiation and scripted verbal consent from all study subjects.

Survey Instrument

With the help of health literacy experts and after reviewing prior work in this field, we developed a 30-question survey that assessed access to communication, awareness of the ACA, insurance status, and barriers individuals face when considering acquiring health insurance. All answers to survey questions were self-reported, including demographic data and housing status. We defined “homelessness” as lack of stable housing for the previous two months, as has been used in previous studies.11 This definition included couch surfing, sleeping at a shelter, sleeping outside, and sleeping in their car, as well as any other form of unstable housing.

The survey instrument included eleven yes/no/not sure questions (e.g., Do you have health insurance?); three analog scale questions (On a scale in which 0 = not difficult and 10 = extremely difficult, how difficult was it to obtain health insurance?); five other numeric-answer questions (How many days a week do you have access to the internet?); ten multiple choice questions (What type of health insurance do you have?); and two questions addressing barriers to enrollment in health insurance (multiple choice and free text). See Appendix A for the full survey instrument.

We pilot-tested the survey on ten homeless patients to gauge their understanding of the questions and check for survey response consistency by having two different researchers interview each patient with a gap of two hours between surveys. The kappa statistic of agreement for the five key survey responses was 1.0 (100% agreement). Prior to the administration of surveys, we gave research personnel a four-hour training session to ensure standard interview technique. Throughout the ten week study period, we conducted weekly meetings with study personnel and random audits of survey data.

Prior to the study we performed a sample size calculation that was driven by the desired width of the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the expected point estimate of the proportion of homeless patients who would know about the ACA. We estimated that 30% would know about it and calculated the need to enroll approximately 127 homeless patients to attain the desired 95% CI width of 8% surrounding this point estimate. We managed data using [blinded for peer review].12 We summarized and reported demographic data in aggregate form and calculated frequency percent, means, mean differences with 95% CIs, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) using STATA v 9.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of the 959 patients considered for the study, 153 (16%) met exclusion criteria including 99 who could not participate in the survey in English, 20 who were intoxicated or had altered mental status, 15 who were on psychiatric holds, 10 who were incarcerated, 5 who were on vacation from another country, and 4 who were under 18 years of age. Of the 806 eligible subjects approached, 663 agreed to participate (response rate of 82.3%). The median age of respondents was 46 years (IQR 32, 57) and 441 (66.5%) were male. Of the 134 (20.2%) subjects who identified themselves as homeless, 74 (55%) said that they were staying at a shelter or transitional housing and 60 (45%) reported that they were currently sleeping outside. Another 54 (8%) patients were staying in single room occupancies (SROs), which are a government subsidized form of housing with minimal provisions (no kitchen and half bathroom) that is often used to provide long-term housing to low-income and previously homeless individuals.13 The housing of 13 (2%) patients did not clearly fit our established criteria for housed or homeless and we therefore did not include them in the analyses.

Only 20% of homeless subjects reported not having health insurance and 72% reported being enrolled in Medicaid, compared to 24% of housed subjects reporting lack of health insurance and 51% enrolled in Medicaid. See Table 1 for a complete description of demographics.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Not Homeless n=462 |

Homeless n=134 |

SRO n=54 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 282 (61) | 104 (78) | 46 (85) |

| Female | 180 (39) | 30 (22) | 8 (15) |

| Age (SD) | 44 (15.6) | 46 (12.8) | 53 (12.6) |

| Chronically homeless, ≥ one year (%) | - | 67 (50) | - |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||

| African-American | 122 (26) | 45 (34) | 27 (50) |

| White | 155 (34) | 63 (48) | 21 (39) |

| Hispanic | 118 (26) | 23 (17) | 1 (2) |

| Asian-American | 51 (11) | 2 (1) | 2 (4) |

| Other | 24 (5) | 2 (1) | 7 (13) |

| Mean # ED visits past year (SD) | 2.8 (4.1) | 6.1 (10.7) | 5 (5.3) |

| Median # ED visits past year (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 6.8) |

| Mean # primary care visits past year (SD) | 3.9 (6.9) | 6.3 (18.8) | 6.1 (9.9) |

| Median # primary care visits past year (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 6.0) | 3.5 (0.0, 7.8) |

| Site of usual health care (%) | |||

| ED | 162 (35) | 63 (47) | 29 (54) |

| Free/Sliding Scale Clinic | 190 (41) | 59 (44) | 22 (41) |

| Private Clinic | 103 (22) | 9 (7) | 3 (6) |

| Other | 6 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Insurance Status (%) | |||

| No health Insurance | 110 (24) | 27 (20) | 6 (11) |

| Medicaid | 236 (51) | 97 (72) | 45 (83) |

| Medicare | 51 (11) | 13 (10) | 11 (20) |

| Veterans Affairs | 2 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Private | 78 (17) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Healthy San Francisco | 33 (7) | 13 (10) | 3 (6) |

| Has had health insurance in the past | 79/110 (72) | 22/27 (81) | 0 (0) |

SRO= Single Room Occupancy, SD= Standard Deviation, IQR = Interquartile Range

Compared to their housed counterparts, subjects that were homeless were less likely to have access to forms of communication including phone (61% vs. 98%; mean difference = 37%, 95% CI [29.1–45.5]), computer (41% vs. 75%, mean difference = 33.6%, 95% CI [24.2–43.4]), and email (41% vs. 71%; mean difference = 29.5%, 95% CI [20.0–38.4]). While 99% of those with housing reported having access to at least one of these devices, only 74% of homeless subjects reported the same (mean difference = 25%, 95% CI [18.7–33.5]). See Table 2 for complete description of access to communication.

Table 2.

Subjects’ Access to Technology and Communication

| Not Homeless n=462 |

Homeless n=134 |

SRO n=54 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Has access to a phone (%) | 454 (98) | 82 (61) | 42 (78) |

| Owns personal cell phone (%) | 415 (90) | 63 (47) | 30 (56) |

| Has access to a computer/tablet (%) | 345 (75) | 55 (41) | 31 (57) |

| Owns personal computer (%) | 280 (60) | 16 (12) | 13 (24) |

| Accesses computer at library (%) | 21 (4.5) | 29 (21) | 8 (15) |

| Mean # days/week with access to computer (SD) | 5.5 (2.7) | 3 (3.2) | 3.5 (3.3) |

| Median # days/week with access to computer (IQR) | 7.0 (5.2, 7.0) | 0.5 (0.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 7.0) |

| Has access to email (%) | 326 (71) | 55 (41) | 23 (43) |

| Mean #days/week use email for communication (SD) | 5.6 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.9) | 3.9 (3.0) |

| Median #days/week use email for communication (IQR) | 7.0 (4.0, 7.0) | 5.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 7.0) |

| Has access to phone+ computer+ email (%) | 296 (64) | 30 (22) | 18 (33) |

| Has access to phone or computer or email (%) | 459 (99) | 99 (74) | 46 (85) |

SRO= Single Room Occupancy, SD= Standard Deviation, IQR = Interquartile Range

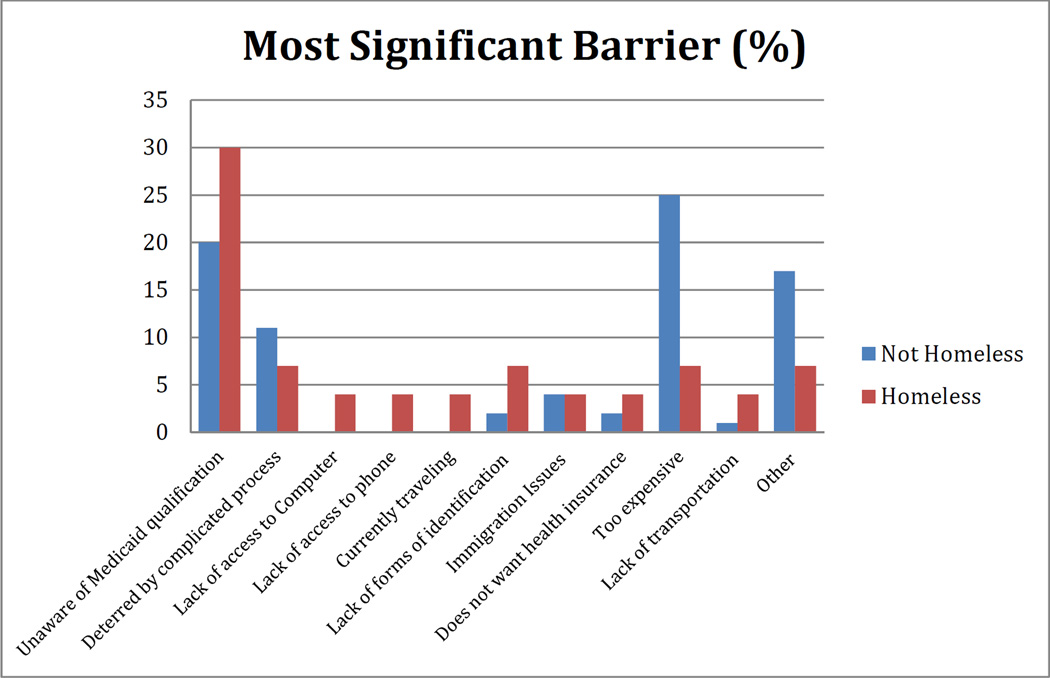

Homeless subjects were more likely to have never heard of the ACA (26% vs 10% mean difference = 16%, 95% CI [8.6–24.3]). Homeless persons also reported “not being aware if they qualified for Medicaid” as their most common and most significant barrier preventing them from enrolling in health insurance. The second most common barrier of this group was “not knowing what steps to take to sign up for health insurance.” Of the homeless subjects who were unsure if they qualified for Medicaid, 90% of them reported an income under 138% of the federal poverty level, likely qualifying them for Medicaid. See Tables 3 and 4 for complete description of ACA awareness and barriers. See Figure 1 for the list of most significant barriers.

Table 3.

Subjects’ Awareness and Involvement in the Affordable Care Act

| Not Homeless n=462 |

Homeless n=134 |

SRO n=54 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Average understanding of the ACA (SD) *Analog scale 0 (low understanding)-10 (very knowledgeable) |

3.5 (0.57) | 2.1 (2.5) | 2.2 (2.6) |

| Where did you hear about the ACA? (%) | |||

| Has never heard of the ACA | 47 (10) | 35 (26) | 7 (13) |

| Television | 290 (63) | 67 (50) | 31 (57) |

| Radio | 29 (6) | 11 (8) | 8 (15) |

| Friend | 48 (10) | 17 (13) | 4 (7) |

| Social Worker | 5 (1) | 9 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Medicaid Provider | 21 (5) | 8 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Other | 86 (19) | 10 (7) | 6 (11) |

| Do you currently qualify for Medicaid? (%) | |||

| Yes | 272 (59) | 111 (83) | 47 (87) |

| No | 75 (16) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 108 (23) | 22 (16) | 7 (13) |

| If unsure, do you make less than 1,300 a month? (%) | |||

| Yes | 57/108 (53) | 20/22 (91) | 5/7 (71) |

| No | 46/108 (43) | 2/22 (9) | 2/7 (29) |

| Has never enrolled in Medicaid prior to January 1st 2014 (%) | 252 (55) | 52 (39) | 15 (28) |

| Attempted to enroll in health insurance through the ACA (%) | 142 (31) | 44 (33) | 14 (26) |

| Successfully enrolled in health insurance through ACA (%) | 83 (18) | 27 (20) | 12 (22) |

| Of those that attempted to enroll, how did you enroll? (%) | |||

| Enrolled online | 61/142 (43) | 6/44 (14) | 2/14 (14) |

| Enrolled at hospital or clinic | 37/142 (26) | 13/44 (30) | 6/14 (43) |

| Enrolled at Medicaid office | 31/142 (22) | 22/44 (50) | 4/14 (29) |

| How important is health insurance to you? (SD) *Analog scale 0 (not important)-10 (very important) |

9.4 (1.5) | 9.2 (1.8) | 9.3 (2.0) |

ACA=Affordable Care Act, SRO=Single Room Occupancy, SD=Standard Deviation

Table 4.

Uninsured Subjects’ Reported Barriers to Enrolling in Health Insurance

| Not Homeless N=110 | Homeless N=27 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrier | Most Significant Barrier |

Barrier | Most Significant Barrier |

|

| I do not know if I qualified for Medicaid (%) | 62 (56) | 22 (20) | 19 (70) | 8 (30) |

| I do not know what steps to take to apply for health insurance (%) | 54 (49) | 19 (17) | 16 (59) | 5 (19) |

| The process of applying for health insurance is too complicated (%) | 54 (49) | 12 (11) | 14 (52) | 2 (7) |

| I do not have access to a computer (%) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 10 (37) | 1 (4) |

| I do not have access to a phone (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (33) | 1 (4) |

| I do not plan on staying in the same city long enough to apply (%) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| I do not have the necessary forms of identification (%) | 9 (8) | 2 (2) | 7 (26) | 2 (7) |

| My current immigration status prevents me from enrolling (%) | 8 (7) | 5 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| I do not want health insurance (%) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) |

| It is too expensive (%) | 67 (61) | 28 (25) | 10 (37) | 2 (7) |

| I do not have access to transportation (%) | 14 (13) | 1 (1) | 9 (33) | 1 (4) |

| Other (%) | 33 (30) | 19 (17) | 6 (22) | 2 (7) |

Subjects were told to select as many barriers as applied to them under the “Barriers” column and then choose one as their “Most Significant Barrier”.

Figure 1.

Most Significant Barriers to Health Insurance Enrollment for Homeless and Housed Subjects

Legend: The bar graph shows the most significant reported barrier to applying for or enrolling in health insurance as a percentage of not-homeless and homeless uninsured patients interviewed.

Of the subjects who reported stable housing, the most significant barrier and the most frequent barrier chosen was cost of enrolling in health insurance. The second most common barrier chosen was “not knowing if they qualified for Medicaid”. Of the housed subjects who were unsure if they qualified for Medicaid, 53% reported an income less than 138% the federal poverty level, likely qualifying them for Medicaid. See Tables 3 and 4 for complete description of ACA awareness and barriers. See Figure 1 for the list of most significant barriers.

DISCUSSION

In our summer of 2014 survey of patients presenting to the ED, we found that most homeless persons had health insurance of some type, most commonly Medicaid. Although most homeless persons had heard of the ACA, they were less familiar with it than their housed counterparts. Similar rates of housed and homeless individuals reported successful enrollment in health insurance since the ACA was implemented. Lack of understanding of health insurance (Medicaid) eligibility and a complicated signup process were the most common reported barriers to enrollment for homeless persons.

Homeless persons were also less likely to have access to means of communication such as phones, computers, and email, and reported these as further barriers to acquisition of insurance. This lack of access to forms of communication makes patient education about the ACA more difficult and may complicate the process of follow-up for successfully enrolled patients. Previous studies have emphasized gradual and targeted relationship building as important for building rapport and trust with individuals experiencing homelessness as a means of increasing enrollment.10 Without the availability of traditional means of communication, targeted in-person outreach and direct assistance will likely be required to successfully enroll those without stable housing in the Medicaid expansion.8

Because the ACA was only very recently implemented, there is little other published data on ACA knowledge and barriers to enrollment to put our findings into context. Before the ACA in 2012, the Kaiser commission on Medicaid and the underserved reported a list of barriers that homeless individuals face to enrollment and accessing Medicaid services.10 This list included many of the barriers that we found, such as difficulty obtaining and providing required documentation, difficulty understanding the application, literacy barriers, lack of a constant phone number and address, lack of transportation, and not receiving notifications to renew Medicaid access.10

In a recent study that looked at likely eligibility for Medicaid expansion in Veterans Affairs (VA) service users, Tsai et al reported that 64% of homeless and 30% of housed persons are likely eligible for Medicaid through the expansion.14 The differences in potential Medicaid eligibility seen in this study compared to ours are likely due to the different populations evaluated. A large VA facility exists close to our study site and only three subjects in our study reported having VA insurance.

Most homeless subjects in our study had some form of health insurance, which contrasts to studies prior to the expansion reporting only 47% of chronically homeless adults having some sort of health insurance.8 Although this may indicate some progress in Medicaid enrollment, it likely also reflects the fact that we conducted this study in a city that has many services directed at the large homeless population. The city supports several programs such as “Healthy San Francisco”, which provides some health insurance benefits to those who live within the city of San Francisco prior to the ACA being put into action. San Francisco’s large homeless population is also of younger age than the national average.15, 16 Other cities with dissimilar homeless populations may have different levels of knowledge about the ACA, as well as lower reported rates of health insurance.2, 10

One basic intervention to improve enrollment may be the provision of information regarding the ACA and Medicaid qualification during presentations to the ED. Many homeless (and non-homeless) individuals were simply unaware that they qualify for Medicaid and therefore did not take steps to attempt to enroll. Along with homeless clinics and shelters, the ED acts as an initial point of contact to many uninsured patients and may thus serve as a pivotal site for patient education regarding the ACA and insurance eligibility.18 Nearly half of homeless persons stated that the ED was their usual site for health care needs. Although overcrowding and resource constraints may limit the amount of staff time available to fully enroll patients, the ED nevertheless has in many ways been demonstrated to serve as a social safety net.12, 17, 18

Limitations

Our results are subject to the limitations of interview-based studies, particularly social desirability bias and failure of participants to respond to all questions. Some subjects may have not wanted to admit that they were homeless or that they did not have health insurance, which would artificially decrease these proportions. The self-reported 0–10 numerical scale for understanding of the ACA may inflate our estimate of their understanding of the ACA by virtue of cognitive bias, in which individuals with low understanding tend to overestimate their understanding of a subject. The cumulative effect of cognitive and social desirability bias is likely an overestimation of patients’ true understanding of the ACA.

Although technically we conducted convenience sampling, in effect we approached all eligible patients consecutively within our specified time periods (block sampling) and therefore minimized selection bias. The daytime hours of interviews may skew our findings slightly toward a different population, but our homeless surveyed rate of 20.6% closely approximates our overall ED’s annual homeless census rate of 20.3%. In terms of selection bias, the most significant limitation of our study is the fact that we only examined the group of patients who actually showed up in the ED. This group, by definition, has at least some access to health care and is likely to have higher rates of ACA knowledge and health insurance than the homeless population at large.

Finally, ethical and feasibility constraints prevented us from interviewing patients who were intoxicated, on psychiatric holds, critically-ill, or who could not participate in the interview in English. Our findings may not reflect those that would be seen in undocumented immigrant homeless persons and those suffering with mental illness and addiction.

CONCLUSION

Most homeless persons in this emergency department had some type of health insurance, but they reported having less knowledge of the ACA than their housed counterparts. Most homeless subjects who do not have health insurance report major barriers to enrollment, especially lack of information, and poor understanding of the enrollment process. Homeless persons were less likely to have access to standard forms of communication (phones and computers) and therefore face-to-face enrollment may be the only way to boost their enrollment. Overall, our findings suggest that homeless patients could benefit from enrollment outreach and education regarding Medicaid eligibility during presentations to the ED.

Article Summary.

Why is this topic important?

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is intended to provide a framework for increasing health care access for vulnerable populations, including the 1.2 million who experience homelessness each year in the US. Opening the door to clinics and other health care access options outside of the ED, the ACA may offload the ED directly and also indirectly affect homeless persons’ presentations to the ED by improving access to primary care and preventive care services.

What does this study attempt to show?

We sought to characterize homeless persons’ knowledge of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), identify barriers to their ACA enrollment, and determine access to various forms of communication that could be used to facilitate enrollment.

What are the key findings?

Homeless persons report 1) having less knowledge of the ACA than their housed counterparts, 2) poor understanding of ACA qualification criteria, and 3) limited access to phone and internet. ED based outreach and education regarding ACA eligibility may increase their enrollment.

How is patient care impacted?

Overcoming barriers to enrollment in the ACA and improving access to primary care and preventive care services may with time lessen the high burden of disease in a medically vulnerable population. Having alternative access points to care may also reduce the overall cost of care and reduce ED overcrowding.

AKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number R25MD006832. The funding organization or sponsor had no role in the design, conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, approval, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

APPENDIX A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Beyond this funding, the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this research.

Author Contributions:

RMR and LF conceived and oversaw the study. LF and PM interviewed patients and contributed to survey instrument design. LF managed and finalized the data including quality control. LF assisted with the background research for the project and drafted the manuscript and RMR contributed substantially to its revisions. RMR takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

References

- 1.Bharel M, Lin WC, Zhang J, et al. Health care utilization patterns of homeless individuals in Boston: preparing for Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S311–S317. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Connell J. Premature mortality in homeless populations: A review of the literature. Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc.; 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors Associated With the Health Care Utilization of Homeless Persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zur J, Mojtabai R, Li S. The cost savings of expanding Medicaid eligibility to include currently uninsured homeless adults with substance use disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(2):110–124. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mcdonough JE, Adashi EY. Realizing the promise of the Affordable Care Act--January 1, 2014. JAMA. 2014;311(6):569–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.286067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal D, Collins SR. Health care coverage under the Affordable Care Act--a progress report. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(3):275–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1405667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. HUD/HHS/VA Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness. West Haven (CT): Northeast Program Evaluation Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA, Culhane DP, Artiga S. Medicaid Expansion: Chronically Homeless Adults Will Need Targeted Enrollment And Access To A Broad Range Of Services. Health Affairs. 2013;32.9:1552–1559. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patricia Post. Casualties of Complexity: Why Eligible Homeless People Are Not Enrolled in Medicaid National Health Care for the Homeless Council. 2001

- 10.Ku BS, Scott KC, Kertesz SG, et al. Factors associated with use of urban emergency departments by the U.S. homeless population. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(3):398–405. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez RM, Fortman J, Chee C, et al. Food, Shelter and Safety Needs Motivating Homeless Persons' Visits to an Urban Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul H, Robert T, Robert T, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linhorst DM. The use of single room occupancy (SRO) housing as a residential alternative for persons with a chronic mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 1991;27(2):135–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00752816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Homeless and nonhomeless VA service users likely eligible for Medicaid expansion. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(5):675–684. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.10.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz MH, Brigham TM. Transforming a traditional safety net into a coordinated care system: lessons from healthy San Francisco. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):237–245. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.San Francisco Homeless Point-in-time count Executive Summary, SF Department of Public Health. 2013

- 17.Ku, Bon S, et al. Factors Associated with Use of Urban Emergency Departments by the U.S. Homeless Population. Public Health Reports. 2010;125.3:398–405. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miner JR, Westgard B, Olives TD, Patel R, Biros M. Hunger and Food Insecurity among Patients in an Urban Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(3):253–262. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.5.6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]