Abstract

Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AutoHCT) is a potentially curative treatment modality for relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). However, no large studies have evaluated pre-transplant factors predictive of outcomes of AutoHCT in children, adolescents and young adults (CAYA, age <30 years). In a retrospective study, we analyzed 606 CAYA patients (median age 23 years) with relapsed/refractory HL who underwent AutoHCT between 1995–2010. The probabilities of progression free survival (PFS) at 1, 5 and 10 years were 66% (95% CI: 62–70), 52% (95% CI: 48–57) and 47% (95% CI: 42–51), respectively. Multivariate analysis for PFS demonstrated that at the time of AutoHCT patients with Karnofsky/Lansky score ≥90, no extranodal involvement and chemosensitive disease had significantly improved PFS. Patients with time from diagnosis to first relapse of <1 year had a significantly inferior PFS. A prognostic model for PFS was developed that stratified patients into low, intermediate and high-risk groups, predicting for 5-year PFS probabilities of 72% (95% CI: 64–80), 53% (95% CI: 47–59) and 23% (95% CI: 9–36), respectively. This large study identifies a group of CAYA patients with relapsed/refractory HL who are at high risk for progression after AutoHCT. Such patients should be targeted for novel therapeutic and/or maintenance approaches post-AutoHCT.

Keywords: CAYA, Autologous transplantation, Hodgkin lymphoma

Introduction

Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) is the most common cancer in children, adolescents and young adults (CAYA) with a peak incidence between the ages of 20 and 341. With the use of chemotherapy alone or with the addition of radiotherapy, the overall survival (OS) rate of newly diagnosed HL in CAYA is approximately 80–90%1,2. However, a subset of CAYA patients with HL have refractory disease to first line therapies or experience disease relapse2. For these patients, conventional salvage therapies, followed by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AutoHCT) is often considered the standard of care. Even with the addition of AutoHCT, many patients will not achieve long-term remission3. The outlook for such patients remains poor. A small prospective study by Baker et al., demonstrated that the 5-year probability of failure-free survival in CAYA patients with relapsed/refractory HL following AutoHCT was only 31%4.

Various factors influence the outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory HL. Long-term survival of patients with HL is age dependent; patients <15 years and 15–29 years have better long-term survival probability than do patients 30–44 years old. Patients older than 45 years of age tend to fare less well5. In a handful of small CAYA AutoHCT studies the following have been shown to be associated with inferior outcomes: time to relapse6–8, primary refractory disease4,6, 9–12, response to salvage chemotherapy7,9,11–13, extranodal involvement10,14, mediastinal mass10 and high serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels at the time of relapse4. While the findings in these studies are compelling, their small sample sizes and inconsistent evaluation methodology make the above prognostic indicators difficult to generalize across larger CAYA population.

In adult patients with HL, various prognostic models have identified and validated various disease and patient-specific variables present either at diagnosis15 or prior to AutoHCT 16–18 that are associated with inferior outcomes. These identified predictive factors in older adults may not be applicable to CAYA, as older adults potentially have more co-morbidity. However, differences in disease biology, if any, among CAYA and older adults are yet to be elucidated.

To date, there are no published large-scale studies looking at risk factors or prognostic indicators in CAYA patients with relapsed/refractory HL undergoing AutoHCT. Thus, in this Center for International Bone Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) analysis, we evaluated various risk factors that might be prognostic in CAYA patients undergoing AutoHCT for relapsed/refractory HL.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on HCTs to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin. Centers report HCTs consecutively with compliance monitored by on-site audits. Patients are followed longitudinally with yearly follow-up. Observational studies by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with federal regulations with ongoing review by the institutional review board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patients

There is no universally accepted definition of AYA. The National Cancer Institute Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group include patients from 15 to 39 years of age. However, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and Children’s Oncology Group’s Adolescents and Young Adults Committees define AYA as 15 to 29 years of age19. In the current study we defined AYA as patients from 15–29 years old.

CAYA (age <30 years) with a histologically proven diagnosis of relapsed or refractory HL, undergoing first peripheral blood AutoHCT reported to the CIBMTR between 1995 and 2010 were included in this study. Patients achieving a complete remission (CR) with 1st line therapy and then undergoing upfront AutoHCT consolidation (n=23), without any evidence of relapsed or refractory disease before transplantation were excluded. Subjects undergoing a planned tandem HCT (tandem AutoHCT, n=14; or AutoHCT followed by tandem allogeneic HCT, n=1), those with nodular lymphocyte predominant HL (n=6), and human immunodeficiency virus positive cases (n=10) were also excluded.

Definitions and Endpoints

To assess disease status at AutoHCT, (chemo-) sensitive disease on CIBMTR forms is define as ≥50% reduction in greatest diameter of all disease sites, with no new sites of disease on radiographic assessment, while (chemo-) resistant disease is defined as <50% reduction in the diameter of all disease sites, or development of new disease sites. Positron emission tomography (PET scan) data were not available for response assessment during the era of this study, the CIBMTR database.

Primary outcomes in this study were non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression/relapse, progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. NRM was defined as death without evidence of disease progression/relapse; relapse was considered a competing event. Progression/relapse was defined as progressive disease after AutoHCT or disease recurrence after a CR; NRM was considered a competing event. For PFS, a patient was considered a treatment failure at the time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. Patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. The OS was defined as the interval from the date of AutoHCT to the date of death or last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Probabilities of PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Probabilities of NRM, disease progression/relapse, and hematopoietic recovery were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate for competing events20. Associations among patient, disease and transplant-related variables and outcomes of interest were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression. A stepwise selection was used to identify covariates that influenced outcomes. Covariates with a p<0.01 were considered significant. The proportionality assumption for Cox regression was tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each risk factor and each outcome. Interactions among significant variables were examined. Results are expressed as relative risk (RR) of occurrence of the event. The variables considered in multivariate analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables tested in Cox proportional hazards regression models for relapse/progression, non-relapse mortality, overall survival and progression free survival.

| Patient-related: |

| Age at transplant, years: continuous; and <21 vs. ≥21 year |

| Gender: Male vs. Female |

| Karnofsky or Lansky performance status ≥90 vs. <90 vs. missing |

| Race: Caucasian/White vs. Black vs. others |

| Disease-related: |

| Histology: nodular sclerosis vs. lymphocyte-rich vs. mixed cellularity vs. lymphocyte depleted vs. HL, not otherwise specified |

| Time from diagnosis to first relapse after 1st line therapy: continuous & <1 year (including refractory to first line) vs. ≥1 year |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant: continuous |

| Disease stage at diagnosis: I/II vs. III/IV |

| B symptoms: No vs. Yes |

| LDH at AutoHCT: normal vs. high |

| Number of lines of therapy prior to transplant: continuous & <3 vs. ≥3 lines |

| First line therapy: ABVD or ABVD-like [±Radiation] vs. All other regimens [± Radiation] vs. Unknown/Missing |

| Extranodal involvement at AutoHCT: No vs. Yes |

| Bulky disease at AutoHCT: No vs. Yes |

| Prior history of radiation therapy: Yes vs. No |

| Disease status at Auto: sensitive vs. resistant |

| Transplant-related: |

| Conditioning regimen: BEAM vs. CBV vs. other |

| Year of transplantation: continuous and 1995–2000 vs. 2001–2005 vs. 2006–2010 |

HL-Hodgkin lymphoma, ABVD-doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, AutoHCT-Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant, BEAM-BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan, CBV-cyclophosphamide, carmustine, etoposide.

Prognostic Model for PFS

To develop a prognostic model of PFS in the CAYA population post-AutoHCT a Cox regression method was used to identify potential risk factors associated with treatment failure (failure event of PFS). This was done using a forward stepwise model with p<0.01 to enter and remove contributing factors from the model. Results were then confirmed using a backward elimination procedure and then a forward selection. The risk factors considered in the model-building procedure are shown in Table 1. Based on the final multivariate model and relative risk of significant prognostic factors, each factor was assigned a score of 1. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Between 1995 and 2010, 606 CAYA with the median age of 23 years (3–29 years) were included in this study. Patient characteristics are described in Table 2. Briefly, the majority of patients in this analysis were Caucasian/white (77%), the most common histological subtype was nodular sclerosis (77%), at diagnosis disease stage was I–II in 50% and III–IV in 48%, while 53% patients had B-symptoms and 32% patients had extranodal involvement at the time of diagnosis. The median number of lines of therapy before AutoHCT was two, and 60% of patients received first line ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) or ABVD-like chemotherapy with or without radiation. Extranodal involvement at AutoHCT was reported in 18% patients. The majority of the patients (79%) had chemosensitive disease prior to AutoHCT. The most commonly utilized conditioning regimen (67%) was BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine and melphalan).

Table 2.

Characteristics of <30 years old patients who underwent AutoHCT for relapsed/refractory HL from 1995–2010 reported to the CIBMTR.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 606 |

| Age at AutoHCT, years | |

| Median | 23 (3–29) |

| <21 | 208 (34) |

| ≥21 | 398 (66) |

| Male Sex | 332 (55) |

| KPS/LPS | |

| <90% | 124 (20) |

| 90–100% | 454 (75) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian/White | 464 (77) |

| Black | 57 ( 9) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 14 ( 2) |

| Hispanic | 58 (10) |

| Others | 13 ( 2) |

| HL subtype | |

| Lymphocyte-rich | 26 ( 4) |

| Nodular sclerosis | 468 (77) |

| Mixed cellularity | 57 ( 9) |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 10 ( 2) |

| Not specified | 45 ( 7) |

| Time from diagnosis to first relapse (TDFR) pre-AutoHCT, months | |

| Median (range) | 22 (5–229) |

| <12 (including patients refractory to 1st line therapy) | 322 (53) |

| ≥12 | 213 (35) |

| Missing | 71 (12) |

| Time from diagnosis to AutoHCT, months (range) | 19 (3–238) |

| Disease stage at diagnosis | |

| I–II | 300 (50) |

| III–IV | 293 (48) |

| Unknown | 13 ( 2) |

| B-Symptoms at diagnosis | |

| Present | 323 (53) |

| Elevated LDH concentration prior to AutoHCT | 158 (26) |

| Number of chemotherapy lines | 2 (1–5) |

| First line chemotherapy | |

| ABVD or ABVD-like ± radiation | 361 (60) |

| BEACOPP-like ± radiation | 23 ( 4) |

| CHOP-like ± radiation | 15 ( 2) |

| MOPP/ABV(±D) or COPP/ABV (±D) Hybrid ± radiation | 88 (15) |

| COPP or MOPP ± radiation | 32 ( 5) |

| Stanford V | 2 (<1) |

| Radiation alone or other chemotherapy ± radiation | 85 ( 14) |

| Bone marrow involvement at diagnosis | 40 ( 7) |

| Bone marrow involvement at AutoHCT | 9 ( 1) |

| Total number of patients | 606 |

| Extranodal involvement at diagnosis | 196 (32) |

| Extranodal involvement at AutoHCT | 107 (18) |

| Bulky disease at AutoHCT | 73 (12) |

| Radiation prior to AutoHCT | 276 (46) |

| Chemosensitive disease prior to AutoHCT | |

| Sensitive | 479 (79) |

| Resistant | 113 (19) |

| Missing (Untreated relapse/unknown (n=11) included) | 14 ( 2) |

| Disease status prior to AutoHCT | |

| PIF sensitive | 90 (15) |

| PIF resistant | 53 ( 9) |

| CR1 | 35 ( 6) |

| Relapsed sensitive | 209 (34) |

| Relapsed resistant | 60 (10) |

| CR2+ | 145 (24) |

| Untreated relapse/unknown | 11 ( 2) |

| Missing | 3 (<1) |

| Conditioning regimens | |

| TBI-based | 33 ( 5) |

| BEAM and similar | 406 (67) |

| CBV or similar | 77 (13) |

| BuMEL/BuCy | 42 ( 7) |

| Others* | 48 ( 8) |

| Year of AutoHCT | |

| 1995–2000 | 325 (54) |

| 2001–2005 | 127 (21) |

| 2006–2010 | 154 (25) |

| Planned radiation post-AutoHCT | 183 (30) |

| Median follow-up of survivors median (range) | 64 (4–216) |

ABVD-like=include omission of either bleomycin or dacarbazine from standard ABVD or substitution of doxorubicin with epirubicin. PIF resistant= primary induction failure sensitive resistant: never in CR but with stable or progressive disease on treatment; PIF sensitive=primary induction failure sensitive: never in CR but with partial remission.

HL-Hodgkin lymphoma, KPS/LS-Karnofsky/Lansky performance status, TDFR-Time from diagnosis to first relapse, LDH- lactate dehydrogenase, ABVD- doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, BEACOPP-Bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, oncovin, procarbazine, prednisone, COPP- , cyclophosphamide, oncovin, procarbazine, prednisone, MOPP-mechlorethamine, oncovin, procarbazine, prednisone CHOP- Cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone AutoHCT- Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant, TBI-total body irradiation, BEAM- BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan, CBV- cyclophosphamide, carmustine, etoposide. BUMEL/BuCy- busulfan-melphalan/busulfan-cyclophosphamide

Bu alone (n=1), Bu+Thio (n=1), Carboplatin+Mito+Thio (n=4), Carboplatin+Thio (n=3), Carboplatin+VP16+ Ifos (n=5), Carboplatin+VP16+LPAM (n=8), Cy+Carboplatin+Thio (n=5), CY+mito/nitro+thio (n=2), Cy+Thio (n=6), Cy+Thio+Mesna (n=2), LPAM alone (n=8), LPAM+Mito (n=1), VP16 (n=1), unknown (n=1)

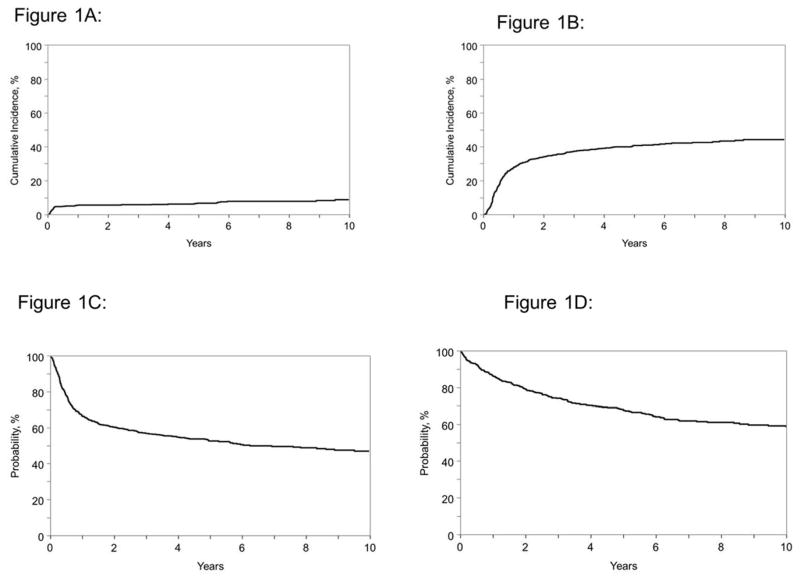

Univariate Outcomes

For the total cohort, the probabilities of NRM at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 6% (95% CI: 4–8), 6% (4–8), 7% (95% CI: 5–9) and 9% (95% CI: 6–12), respectively (Figure 1A). The probabilities of disease progression/relapse at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 28% (95% CI: 24–32), 38% (95% CI: 34–42), 41% (95% CI: 37–45) and 45 % (95% CI: 40–49) (Figure 1B). The probabilities of PFS at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 66 % (95% CI: 62–70), 57% (95% CI: 53–61), 52% (95% CI: 48–57) and 47% (95% CI: 42–51), respectively (Figure 1C). The probability for OS were 87% (95% CI: 84–89), 74% (95% CI: 70–78), 68% (95% CI: 63–71) and 58% (95% CI: 53–63), respectively (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes for children, adolescents and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma

1A: Non-relapse related mortality.

1B: Progression/relapse.

1C: Progressions free survival.

1D: Overall survival.

Multivariate Outcomes

On multivariate analysis for NRM, the single significant factor associated with higher NRM was utilization of non-ABVD regimens as a first line therapy compared to ABVD/ABVD-like regimens (RR=2.47; 95% CI=1.32–4.62: p=0.004) [Table 3]. Multivariate analysis for disease progression/relapse demonstrated that patients with Karnofsky/Lansky performance score (KPS/LPS) <90 (RR=1.46; 95% CI=1.08–1.98: p=0.01), utilization of CBV (cyclophosphamide, BCNU and etoposide) conditioning regimen (RR=1.72; 95% CI=1.21–2.45: p=0.003), presence of extranodal involvement at AutoHCT (RR=1.67; 95% CI=1.23–2.29: p=0.001) and chemoresistant disease (RR=1.75; 95% CI=1.29–2.36; p=0.0003) were associated with a higher risk of relapse/progression post-AutoHCT, while time from diagnosis to first relapse (TDFR) interval of ≥1 year was associated with a reduced risk of progression/relapse (RR= 0.65; 95% CI=0.48–0.88: p=0.006).

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses for NRM, progression/relapse, PFS and OS.

| Non-relapse related mortality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First line therapy | N | RR | 95%CI Lower Limit | 95%CI Upper Limit | p-value |

| ABVD or ABVD like | 359 | 1 | |||

| Other regimens | 221 | 2.47 | 1.32 | 4.62 | 0.004 |

| Missing | 24 | 6.41 | 2.63 | 15.60 | <0.0001 |

| Progression/relapse | |||||

| Karnofsky/Lansky score | |||||

| ≥90 | 453 | 1 | |||

| <90 | 124 | 1.46 | 1.08 | 1.98 | 0.01 |

| Missing | 27 | 1.63 | 0.94 | 2.84 | 0.08 |

| TDFR | |||||

| < 1 year | 321 | 1 | |||

| ≥1 year | 212 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.88 | 0.006 |

| Missing | 71 | 1.35 | 0.98 | 1.99 | 0.13 |

| Extranodal involvement at AutoHCT | |||||

| No | 476 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 107 | 1.67 | 1.23 | 2.29 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 21 | 1.19 | 0.60 | 2.36 | 0.62 |

| Disease status | |||||

| Chemosensitive | 478 | 1 | |||

| Resistant | 112 | 1.75 | 1.29 | 2.36 | 0.0003 |

| Missing | 14 | 2.14 | 1.05 | 4.40 | 0.04 |

| Conditioning regimen | |||||

| BEAM | 404 | 1 | |||

| CBV | 77 | 1.72 | 1.21 | 2.45 | 0.003 |

| Other | 123 | 1.3 | 0.95 | 1.78 | 0.10 |

| Therapy failure (inverse of PFS) | |||||

| Karnofsky/Lansky performance score | |||||

| ≥90 | 453 | 1 | |||

| <90 | 124 | 1.45 | 1.10 | 1.92 | 0.008 |

| Missing | 27 | 1.57 | 0.95 | 2.59 | 0.08 |

| TDFR | |||||

| < 1 year | 321 | 1 | |||

| ≥1 year | 212 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Missing | 71 | 1.35 | 0.95 | 1.91 | 0.09 |

| Extranodal involvement | |||||

| No | 476 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 107 | 1.59 | 1.19 | 2.12 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 21 | 1.50 | 0.85 | 2.66 | 0.16 |

| Disease status | |||||

| Chemosensitive | 478 | 1 | |||

| Resistant | 112 | 1.84 | 1.40 | 2.42 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 14 | 2.06 | 1.05 | 4.05 | 0.03 |

| Mortality (overall survival) | |||||

| TDFR | |||||

| < 1 year | 322 | 1 | |||

| ≥1 year | 213 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.86 | 0.004 |

| Missing | 71 | 1.20 | 0.79 | 1.83 | 0.39 |

| First line therapy | |||||

| ABVD or ABVD like | 361 | 1 | |||

| Other regimens | 221 | 1.64 | 1.21 | 2.22 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 24 | 2.30 | 1.23 | 4.32 | 0.01 |

| Extranodal involvement | |||||

| No | 478 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 107 | 1.81 | 1.29 | 2.52 | 0.0005 |

| Missing | 21 | 1.91 | 1.03 | 3.55 | 0.04 |

| Disease status | |||||

| Chemosensitive | 479 | 1 | |||

| Resistant | 113 | 2.27 | 1.64 | 3.13 | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 14 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 2.50 | 0.84 |

ABVD- doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, ABVD-like=include omission of either bleomycin or dacarbazine from standard ABVD or substitution of doxorubicin with epirubicin. TDFR-Time from diagnosis to first relapse, AutoHCT- Autologous hematopoietic cell transplant, BEAM- BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan, CBV- cyclophosphamide, carmustine, etoposide. BUMEL/BuCy- busulfan-melphalan/busulfan-cyclophosphamide.

Patients who had a KPS/LPS <90 (RR–1.45; 95% CI=1.10–1.92: p=0.008), extranodal involvement at AutoHCT (RR=1.59; 95% CI=1.19–2.12: p=0.001) and chemoresistant disease (RR=1.84; 95% CI=1.40–2.42: p<0.0001) had a higher risk of therapy failure (i.e. inferior PFS). Patients with TDFR interval of ≥1 year had a lower risk of therapy failure (i.e. superior PFS) (RR=0.71; 95% CI=0.54–0.93: p=0.01) [Table 3].

On multivariate analysis a higher risk of mortality (inferior OS) was associated with first line therapy with non-ABVD compared to ABVD/ABVD-like regimens (RR=1.64; 95% CI=1.21–2.22: p=0.001), the presence of extranodal involvement at AutoHCT (RR=1.81; 95% CI=1.29–2.52: p=0.0005), and chemoresistance disease (RR=2.27; 95% CI=1.64–3.13: p=<0.0001). In contrast, patients with a TDFR interval of ≥ 1 year had a lower risk of mortality (i.e. superior OS) (RR=0.62; 95% CI=0.44–0.86: p=0.004) [Table 3].

Prognostic Model for PFS

The four significant adverse prognostic factors, each assigned a score of 1, included in the final model were (i) KPS/LPS <90%, (ii) TDFR of <1 year, (iii) extranodal involvement at AutoHCT and (iv) chemoresistant disease at AutoHCT. The score for any individual patient using the 4 significant prognostic factors, ranged from 0 to 4. Table 4 summarizes the prognostic model’s performance. Distribution of patients by total risk score was as follows: 126 patients had a total risk score of 0 (reference category), 192 patients had a total risk score of 1 (RR=1.81 range, 1.25 to 2.62), 129 patients had a total risk score of 2 (RR=2.11 range, 1.42 to 3.13), 38 patients had a total risk score of 3 (RR=3.92 range, 2.42 to 6.36) and 4 patients had a total risk score of 4 (RR=11.33 range, 4.03 to 31.82).

Table 4.

Prognostic Model for progression-free survival

| 95% CI | 95% CI | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prognostic Score | N | RR | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | p-value | p-value |

| 0 | 126 | 1 | <0.0001 | |||

| 1 | 192 | 1.81 | 1.25 | 2.63 | 0.002 | |

| 2 | 129 | 2.11 | 1.42 | 3.13 | 0.0002 | |

| 3 | 38 | 3.93 | 2.42 | 6.36 | <0.0001 | |

| 4 | 4 | 11.33 | 4.03 | 31.82 | <0.0001 | |

| Contrast | ||||||

| 1 vs. 2 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 1.19 | 0.36 | ||

| 1 vs. 3 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.0004 | ||

| 1 vs. 4 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.0004 | ||

| 2 vs. 3 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.84 | 0.006 | ||

| 2 vs. 4 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 vs. 4 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.99 | 0.05 | ||

| PFS Risk Groups | ||||||

| 95% CI | 95% CI | Overall | ||||

| Risk Group | N | RR | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | p-value | p-value |

| Low (Score=0) | 126 | 1 | <0.0001 | |||

| Intermediate (Score=1 or2) | 321 | 1.92 | 1.36 | 2.72 | 0.0002 | |

| High(Score=3 or 4) | 42 | 4.27 | 2.68 | 6.79 | <0.0001 | |

| Contrast | ||||||

| Intermediate vs. High | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.66 | <0.0001 |

PFS-progression-free survival

Based on the range of RR and the distribution of patients across the total risk score categories, we classified each patient into three prognostic risk groups: low-risk group (score = 0), intermediate-risk group (score = 1 or 2), or high-risk group (score = 3 or 4). Statistical significance was reached when we compared the PFS between low and intermediate group (p=0.0002), low and high risk group (p<0.0001) and intermediate and high risk group (p<0.0001). The 3-year PFS probabilities for the low, intermediate and high risk groups are 75% (95% CI=67–82), 56% (95% CI=51–62) and 29% (95% CI=15–43), respectively. The probability for 5-year PFS were 72% (95% CI: 64–80), 53% (95% CI: 47–59) and 23% (95% CI: 9–36) respectively, for the three prognostic groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prognostic model predicting progression free survival for children, adolescents and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma with low, intermediate and high risk scores [low vs. intermediate score (p=0.0002), low vs. high score (p<0.0001) and intermediate vs. high score (p<0.0001)].

Cause of Death and Secondary Malignancies

At a median follow-up of 64 months 209 patients were no longer alive. The primary causes of death post-AutoHCT were recurrent HL (N=154, 74% of all deaths), organ failure (N=12, 6%), second malignancy (N=4, 2%), infection (N=7, 3%) or other/indeterminate (N=32, 15%). At a median follow-up of 64 months, 16 patients (3%) developed secondary malignancies. New malignancies reported included one case each of basal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, prostate cancer, oligodendroglioma, carcinoma of the pleural cavity and two cases each of acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome and thyroid cancer. There were 3 cases of genitourinary cancer and one missing second malignancy subtype.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study describing the outcomes of CAYA with relapsed/refractory HL following AutoHCT. For the first time, we propose a prognostic model specifically for CAYA patients undergoing AutoHCT for relapsed/refractory HL. Previous HL models included older patients and therefore may not be as relevant for the CAYA population. Our large CAYA data set enabled us to develop a simple-to-use, clinically relevant prognostic model identifying 4 risk factors easily available at the time of AutoHCT.

Due to the improvement in upfront treatment strategies for newly diagnosed HL, the outcome for patients with HL has improved such that approximately 80% of HL patients become long-term survivors now 21. However, for those who have relapsed or refractory disease, outcomes are variable, with some patients achieving long-term remission after AutoHCT and others responding poorly. Improved prognostic tools are needed to identify such high-risk patients. Various prognostic factors have been identified from a series of clinical studies that are frequently small. Such studies often lack statistical power to definitively define prognostic factors, which has led to a lack of consistency and consensus across studies2,22. Because of this, accurately determining risk of treatment failure for CAYA patients undergoing AutoHCT remains a challenge, which makes identification of patients suitable for intensified or investigational therapies difficult. CIBMTR data are uniformly collected with rigorous quality control and has large number of patients with contemporary and generalizable data. Hence, in this large analysis we were able to identify the prognostic factors associated with poor outcomes in CAYA patients with HL post-AutoHCT.

Previously published studies with small number of patients (highest n=70)12, prognostic factors that have been studied in CAYA are primary refractory disease (3–10 year OS/EFS/DFS: 35–47%)6,9–12, early relapse within one year of diagnosis (3–10 years OS/DFS: 34–67%)6–8, poor response to salvage therapy (2–5 year OS/DFS/EFS: 6–30%)7,9,11–13, extranodal involvement at relapse (8 year EFS-7%)14 and B-symptoms at relapse (2yr OS-27%)9. In our large CAYA study, the probabilities of PFS at 1 and 5 years following AutoHCT were 66% and 52%, respectively. Patients with TDFR of <1 year, extranodal involvement at AutoHCT, chemoresistant disease and KPS/LPS <90 at the time of AutoHCT all had inferior PFS. Of interest, according to our analysis, age, time from diagnosis to AutoHCT, disease stage at diagnosis and relapse, B-symptoms, bulky disease at the time of AutoHCT, LDH at the time of AutoHCT, number of chemotherapy regimens prior to AutoHCT and radiation therapy prior to AutoHCT were not associated with PFS.

Our analysis of 606 HL CAYA patients, with relapse/refractory HL who were treated with AutoHCT found three prognostic factors consistently associated with relapse/progression, PFS and OS. These prognostic indicators were as follows: TDFR <1 year, extranodal involvement at relapse and chemoresistant disease at the time of AutoHCT.

This study has limitations of being retrospective, patients were reported to the CIBMTR over the period of 15 years, and PET scan data were not collected. Over that last decade PET scan has emerged as an important prognostic factor in adults with relapsed HL as patients with negative PET study prior to AutoHCT have been shown to have superior outcomes23–24. With regard to our study, PET data was not uniformly captured during the era in question. We therefore were not able to determine the impact of PET status pre-AutoHCT. Our data suggest that the extent of exposure to specific cytotoxic chemotherapy agents during salvage therapy does not directly correlate with PFS. However, knowing that PET-avid disease prior to AutoHCT has been associated with inferior outcomes in other studies23–24, reasonable efforts should be made to achieve PET negative status prior to AutoHCT, whether that be using conventional therapy25 or novel therapies such as brentuximab vedotin26 or bendamustine27.

Various conditioning regimens have been utilized for patients with relapsed HL. In our study BEAM, busulfan-based and CBV were the most frequently utilized regimens. In multivariate analysis, the incidence of NRM did not differ across various conditioning regimens. We did find, however, that compared to BEAM, CBV conditioning was associated with a higher-risk of progression/relapse (RR-1.72, p=0.002). Similar results were reported by William et al28. NRM in our study was 6% and 7% at 1 and 5 years respectively which is comparable to the studies published in adults with relapsed/refractory HL receiving AutoHCT 29–31. However, incidence of NRM in a prospective COG study that utilized CBV conditioning regimen for AutoHCT in children with relapsed/refractory lymphoma was 13% (5/38)7. In the current study, utilization of non-ABVD regimens as a first line therapy was associated with higher NRM and lower OS. It is plausible that patients treated with a more intensive first line non-ABVD regimen have less risk of primary relapse. However, few patients who relapse experience higher NRM resulting in lower OS.

The CAYA population with HL is a unique and challenging, despite excellent outcomes, still includes a subset of patients whose survival is unacceptably low. Because they are younger at diagnosis, they are at risk of long-term complications and significant morbidity later in life as a result of disease treatment. The prognostic model developed in our study identifies a group of high-risk patients, who have suboptimal outcomes despite AutoHCT salvage. Investigation of novel conditioning approaches or post-AutoHCT therapies e.g. maintenance brentuximab vedotin26, reduced-intensity allogeneic HCT35, cellular therapy36 or incorporation of PD-1 inhibitors37, for these CAYA with poor prognosis is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the patients and centers reporting to CIBMTR and CIBMTR Lymphoma. We would also like to acknowledge the following committee members for their scientific input: Baldeep Wirk, Basem M. William, Harry C. Schouten, Nishitha M. Reddy, David Rizzieri, Mahmoud Aljurf, Reinhold Munker, Brandon Hayes-Lattin, Victor A. Lewis, and Maggie M. Simaytis for administrative support.

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-12-1-0142 and N00014-13-1-0039 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from * Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; * Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; * Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; * Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; * Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;* Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; * Milliman USA, Inc.; * Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; * Remedy Informatics; * Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; * Tarix Pharmaceuticals; * TerumoBCT; * Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; * THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and * Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Corporate Members

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Praskash Satwani & Mehdi Hamadani

Collection and assembly of data: Kwang Woo Ahn, Jeanette Carreras and Mehdi Hamadani

Data analysis: Kwang Woo Ahn, Jeanette Carreras with final approval on fidelity of analysis by CIBMTR statistical center in Milwaukee, WI.

Data Interpretation: Prakash Satwani, Kwang Woo Ahn, Jeanette Carreras and Mehdi Hamadani. All remaining authors provided written comments on interpretation of data.

Manuscript writing: Prakash Satwani and Mehdi Hamadani prepared the first manuscript draft. All authors critically reviewed the study and provided detailed written comments initially at the conception of study protocol, after results of analysis were available, and finally helped revise/write the final draft of the manuscript.

Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: No conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, et al. Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:24–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly KM. Management of children with high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daw S, Wynn R, Wallace H. Management of relapsed and refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:249–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker KS, Gordon BG, Gross TG, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s disease in children and adolescents. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:825–831. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG, editors. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975–2000. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2006. NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schellong G, Dorffel W, Claviez A, et al. Salvage therapy of progressive and recurrent Hodgkin’s disease: results from a multicenter study of the pediatric DAL/GPOH-HD study group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6181–6189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris RE, Termuhlen AM, Smith LM, et al. Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in children with refractory or relapsed lymphoma: results of Children’s Oncology Group study A5962. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;17:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoneham S, Ashley S, Pinkerton CR, et al. Outcome after autologous hemopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsed or refractory childhood Hodgkin disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:740–745. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhtar S, El Weshi A, Rahal M, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant in adolescent patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:476–482. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieskovsky YE, Donaldson SS, Torres MA, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for recurrent or refractory pediatric Hodgkin’s disease: results and prognostic indices. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4532–4540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metzger ML, Hudson MM, Krasin MJ, et al. Initial response to salvage therapy determines prognosis in relapsed pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Cancer. 2010;116:4376–4384. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorde-Grosjean S, Oberlin O, Leblanc T, et al. Outcome of children and adolescents with recurrent/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma, a study from the Societe Francaise de Lutte contre le Cancer des Enfants et des Adolescents (SFCE) Br J Haematol. 2012;158:649–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shafer JA, Heslop HE, Brenner MK, et al. Outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplant as salvage therapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adolescents and young adults at a single institution. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:664–670. doi: 10.3109/10428190903580410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wimmer RS, Chauvenet AR, London WB, et al. APE chemotherapy for children with relapsed Hodgkin disease: a Pediatric Oncology Group trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:320–324. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Carreras J, et al. Simplified validated prognostic model for progression-free survival after autologous transplantation for hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1740–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Josting A, Franklin J, May M, et al. New prognostic score based on treatment outcome of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma registered in the database of the German Hodgkin’s lymphoma study group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:221–230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hahn T, Benekli M, Wong C, et al. A prognostic model for prolonged event-free survival after autologous or allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:557–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollock BH, Birch JM. Registration and classification of adolescent and young adult cancer cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1090–1093. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, et al. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harker-Murray PD, Drachtman RA, Hodgson DC, et al. Stratification of treatment intensity in relapsed pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:579–586. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akhtar S, Al-Sugair AS, Abouzied M, et al. Pre-transplant FDG-PET-based survival model in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: outcome after high-dose chemotherapy and auto-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:1530–1536. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moskowitz AJ, Yahalom J, Kewalramani T, et al. Pretransplantation functional imaging predicts outcome following autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:4934–4937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moskowitz CH, Matasar MJ, Zelenetz AD, et al. Normalization of pre-ASCT, FDG-PET imaging with second-line, non-cross-resistant, chemotherapy programs improves event-free survival in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119(7):1665–1670. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-388058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moskowitz CH, Nadamanee A, Masszi T, et al. The Aethera trial: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of brentuximab vedotin in the treatment of patients at risk of progression following autologous stem cell transplant for Hodgkin lymphoma. Presented at: 2014 ASH Annual Meeting; December 6–9, 2014; San Francisco, CA. p. Abstract 673. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moskowitz AJ, Hamlin PA, Jr, Perales MA, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:456–460. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.William BM, Loberiza FR, Jr, Whalen V, et al. Impact of conditioning regimen on outcome of 2-year disease-free survivors of autologous stem cell transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13(4):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benekli M, Smiley SL, Younis T, et al. Intensive conditioning regimen of etoposide (VP-16), cyclophosphamide and carmustine (VCB) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(7):613–619. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kebriaei P, Madden T, Kazerooni R, et al. Intravenous busulfan plus melphalan is a highly effective, well-tolerated preparative regimen for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with advanced lymphoid malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(3):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadehra N, Farag S, Bolwell B, et al. Long-term outcome of Hodgkin disease patients following high-dose busulfan, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(12):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehl V, Franklin J, Pfreundschuh M, et al. M: German Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group. Standard and increased-dose BEACOPP chemotherapy compared with COPP-ABVD for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2386–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly KM, Sposto R, Hutchinson R, et al. BEACOPP chemotherapy is a highly effective regimen in children and adolescents with high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2011;117(9):2596–2603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Josting A, Müller H, Borchmann P, et al. Dose intensity of chemotherapy in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(34):5074–5080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satwani P, Jin Z, Martin PL, et al. Sequential myeloablative autologous stem cell transplantation and reduced intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is safe and feasible in children, adolescents and young adults with poor-risk refractory or recurrent Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia. 2015;29:448–455. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Torrano V, et al. Sustained complete responses in patients with lymphoma receiving autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:798–808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 Blockade with Nivolumab in Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.