Abstract

Aspirin has been shown to protect against colorectal neoplasms, however the optimal chemopreventive dose and underlying mechanisms are unclear. We aimed to study the relationship between prostanoid metabolites and aspirin’s effect on adenoma occurrence. We used data from the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study, in which 1,121 participants with a recent adenoma were randomized to placebo or two doses of aspirin (81 or 325 mg/d) to be taken until the next surveillance colonoscopy, anticipated about 3 years later. Urinary metabolites of prostanoids (PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2) were measured using LC/MS or GC/NICI-MS in 876 participants near the end of treatment follow-up. Poisson regression with a robust error variance was used to calculate relative risks and 95% confidence intervals. PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2 levels were 28%, 37%, and 60% proportionately lower, respectively, in individuals who took 325 mg of aspirin compared to individuals who took placebo (all P<0.001). Similarly, among individuals who took 81 mg of aspirin, PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2 were, respectively, 18%, 30%, and 57% proportionally lower compared to placebo (all P<0.005). None of the metabolites or their ratios were statistically significantly associated with the risk of adenoma occurrence. The effect of aspirin in reducing adenoma risk was independent of prostanoid levels. Aspirin use is associated with lower levels of urinary prostanoid metabolites. However, our findings do not support the hypothesis that these metabolites are associated with adenoma occurrence, suggesting that COX-dependent mechanisms may not completely explain the chemopreventive effect of aspirin on colorectal neoplasms.

Keywords: aspirin, prostaglandins, thromboxanes, colorectal neoplasms, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

There is strong evidence from observational studies and randomized clinical trials that aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are protective against colorectal neoplasms (1–5), however the dose-response relationship and underlying antineoplastic mechanisms are not clear. Pooled results from four clinical trials with 2,967 participants randomly assigned to doses of aspirin from 81 to 325 mg daily showed a borderline statistically significant 15% decrease in any adenoma occurrence, and a statistically significant 29% decrease in advanced adenoma occurrence with higher-dose aspirin supplementation (≥300 mg/d)(6). Interestingly, in a combined analysis of the two trials (2, 5) [including ours (2)] that tested higher (300 or 325 mg/d) and lower (≤160 mg/d) doses of aspirin versus placebo, lower-dose aspirin showed statistically significantly greater risk reduction for all colorectal adenomas than higher-dose aspirin (6).

Prostanoids, important mediators of human physiology, are a subclass of eicosanoids consisting of the prostaglandins (PGs), the prostacyclins, and the thromboxanes. They are generated from the precursor arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes: COX-1, constitutively expressed in the luminal gastrointestinal tract and responsible for the production of cytoprotective PGs; and COX-2, inducible by a variety of factors such as growth factors and mitogens, and a central element of the inflammatory response (7). The increased activity of COX-2 plays an important role in colorectal carcinogenesis (8, 9); the involvement of COX-1 has been less investigated, but also appears to be involved (10). Of the PGs, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is likely to be the primary mediator of COX pro-carcinogenic effects (8).

Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and prostacyclin (PGI2) are other prostanoids, both well known to regulate cardiovascular homeostasis: TXA2 stimulates vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation, whereas prostacyclin PGI2 promotes vasodilatation and inhibits platelet aggregation (8). In addition to their cardiovascular effects, both PGI2 and TXA2 appear to affect carcinogenesis. Thromboxane A2 activation of platelets leads to the release of mediators of carcinogenesis, and TXA2 itself seems to act as a pro-carcinogenic factor (10–13). On the other hand, PGI2 seems anticarcinogenic (14): lower levels are seen in neoplastic tissue (15–17), in vitro and in vivo studies suggest interference with carcinogenesis (12, 18), and studies of the prostacyclin synthase gene point to anti-neoplastic effects as well (19, 20).

Low doses of aspirin are sufficient to reduce PGE2 levels in the colorectal mucosa, with no additional increase in inhibition with doses above 81 mg per day (21–25). There have been no studies of the effects of aspirin on PGI2 or TXA2 in the large bowel mucosa, but higher doses are generally required to substantially modulate systemic prostacyclin production (26–29), while lower doses are effective in inhibiting platelet TXA2, and increasing the ratio of PGI2 to TXA2 (30–32). If prostacyclin has anti-neoplastic properties, aspirin doses above 81 mg would then lose preventive potency from the inhibition of this potentially anti-neoplastic prostanoid.

To understand the role of PGE2, PGI2, and TXA2, in colorectal carcinogenesis, we conducted secondary analyses in the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study (AFPPS) (2, 33), a clinical trial of aspirin and/or folic acid for the prevention of occurrence of colorectal adenomas. Our aims were to assess the effect of two doses of daily aspirin intake on urinary prostanoid metabolites; to investigate whether urinary prostanoid metabolites are associated with risk for recurrent adenoma diagnosed during treatment; and to examine whether a hypothesized aspirin dose-dependent PGE2 to PGI2 trade-off plays a role in colorectal adenoma development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

These data were collected as part of the AFPPS, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-by-two factorial trial testing whether oral aspirin (81 or 325 mg daily) or folic acid (1 mg daily) reduces the risk of new colorectal adenomas (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00272324) (2, 33).

Recruitment, randomization, treatment, and follow-up

Details of subject eligibility, recruitment, randomization, treatment, and follow-up, and study outcomes have been previously described (2, 33). Briefly, patients with a recent history of colorectal adenomas were recruited between during 1994–1998 from nine clinical centers in the US and Canada. Eligible subjects were between 21 and 80 years of age, in good health, had a complete colonoscopy within 3 months before enrollment with no known polyps left in the bowel, and had received a recommendation for a 3-year follow-up colonoscopy by their regular medical practitioner.

At enrollment, eligible subjects completed a questionnaire regarding demographics, medical history, and lifestyle habits. All participants were asked to avoid the use of aspirin, NSAIDs, and supplements containing folate for the duration of active treatment. Each subject underwent a three-month, single-blind run-in period on 325 mg of aspirin per day. Only subjects with at least 80% compliance and no adverse effects of aspirin were randomly assigned to receive aspirin placebo, low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d), or high-dose aspirin (325 mg/d), and to receive folate placebo or folate (1 mg/d). A total of 1,021 full factorial subjects were randomized, as well as 100 “aspirin-only” subjects who were recruited before the folic acid component of the study was added.

By protocol, participants were to remain on study treatment until their anticipated surveillance colonoscopy, about three years after the qualifying exam. Every 4 months during study treatment subjects completed a questionnaire regarding compliance with study agents, use of medications and supplements, large bowel endoscopy, and medical events. In addition to a baseline blood sample, blood and spot urine samples were obtained late in the third year of participation, and stored at −70°C. Compliance in the initial 3-year treatment period was excellent: 87% to 95% of subjects took study pills at least 6 days per week during those three years. All study aspirin treatment ended on September 28, 2001.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome — adenoma occurrence — was determined by colonoscopy and confirmed by pathology review. All lesions removed from the large bowels of study subjects were reviewed by a single study pathologist. Polyps were classified as adenomatous, hyperplastic, serrated or other polyps; the degree of dysplasia and the extent of villous component in each adenoma were recorded. Low-risk adenomas were defined as solitary adenomatous polyps < 1 cm in greatest diameter with tubular histology. Advanced adenomas were defined as adenomatous polyps with an estimated diameter of ≥1 cm, or at least 25% villous component, any high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer. “High risk findings” were one or more advanced adenomas or two or more low risk adenomas [for comparability with previous studies (34, 35)].

Laboratory Measurements

Catabolism of PGE2 results in an end metabolite, 11-α-hydroxy-9,15-dioxo-2,3,4,5-tetranor-prostane-1,20-dioic acid (PGE-M), that is excreted in the urine and stable for prolonged periods when stored at −70°C (36). Measurement of urine PGE-M is a better measure of systemic PGE2 production than plasma measurements (37, 38) because PGE2 in plasma is rapidly metabolized in the lungs and consequently may not accurately reflect endogenous prostaglandin production (39). We measured urinary PGE-M using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) as previously described (40) on a Waters Acquity UPLC coupled to a Thermo Scientific Quantum Vantage triple quadruple mass spectrometer.

2,3-dinor-6-keto-PGF1α (PGI-M), a major urinary metabolite of prostacyclin PGI2, was measured using gas chromatography-negative-ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry (GC/NICI-MS) as previously described (41) on an Agilent 5973 Inert Mass Selective Detector coupled with an Agilent 6890n Network GC system (Agilent Labs, Torrance, CA). 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2 (dTxB2), a major urinary enzymatic metabolite of thromboxane A2, was measured using GC/NICI-MS as previously described (42) using the same instruments as described above for PGI-M.

PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2 were successfully measured in 871, 816, and 854 samples, respectively, in the Eicosanoid Core Laboratory at Vanderbilt University. The lower limit of detection of PGE-M and PGI-M was 15 pg/mg creatinine, and of dTxB2, 20 pg/mg creatinine. Inter-day and intra-day variability was less than 10% for all prostanoids assays. Quality control samples, from a pooled urine collection, were included with each batch analyzed. Between-batch coefficients of variation were 8.38%, 5.92%, and 7.32%, for the PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2 assays, respectively. Urinary prostanoid metabolite levels were expressed as pg/mg of analyte per mg of urinary creatinine. Urinary creatinine was measured using a chemical assay based on Jaffe’s reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Enzo Life Sciences, NY, USA). Laboratory staff was blinded to the treatment group assignment of urine samples and the identity of quality control samples included in the study. Samples from each treatment group were randomly included in every batch.

Statistical Analyses

Levels of urinary biomarkers were natural log transformed to improve normality. Values below limit of detection (LOD) were replaced by LOD/2 [n = 4 (0.5%) for PGE-M, n = 61 (7.5%) for PGI-M, and n = 4 (0.5%) for dTxB2]. Fisher exact tests (for categorical variables) and analysis of variance (for continuous variables) were used to compare randomized treatment groups. Correlations between biomarkers were calculated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ). We used modified Poisson regression with a robust variance estimate to calculate the relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of having at least one adenoma (43). Covariates in multivariable models included age (continuous), sex, clinical center, number of lifetime adenoma before randomization (continuous), follow-up time (continuous), and aspirin treatment group assignment (placebo, 81 mg/d, or 325 mg/d). In secondary analyses, we further adjusted for randomized folic acid treatment, first degree family history of colorectal cancer (yes/no), body mass index (<25, 25 – 30, ≥ 30 kg/m2) at study enrollment, alcohol use (yes/no), smoking status (never/former/current). Inclusion of these covariates in the models did not substantially change the results; therefore, only the most parsimonious models are presented. Adjusted estimates are presented for one or more adenomas, low-risk adenomas, or advanced adenomas, and high-risk findings. The ratio of PGE-M to PGI-M was used as an indicator of trade-off between systemic PGE2 and PGI2 production. Since PGE2 and thromboxane A2 are hypothesized to be pro-carcinogenic, and PGI2 possibly anti-carcinogenic, we used the ratio of (PGE-M + dTxB2) to PGI-M as an indicator of the overall balance between potentially pro- and anti-carcinogenic effects of prostanoids. The P-value for trend was calculated using the continuous biomarker levels entered linearly into the models. An interaction by aspirin treatment assignment (placebo, 81 mg/d, or 325 mg/d) was assessed by including the cross product of the treatment variable and urinary biomarker, and evaluated using the Wald test. To compare our results with previous findings (35), we conducted an analysis of aspirin treatment effects within low (first tertile) and high (second and third tertiles) PGE-M levels. All statistical tests were two-sided. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata (version 12.1, Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

There were 1,121 individuals randomized to aspirin or placebo, and 1,084 (97%) underwent a follow-up examination. A total of 876 participants (80.8% of with a follow-up exam) had at least one urinary prostanoid metabolite measurement; 328 had one or more recurrent adenoma at the end of treatment follow-up. The baseline characteristics of the subjects in the three aspirin treatment arms with at least one biomarker measurement are shown in Table 1. Participants with missing urine measurements (n = 208) were comparable with those included in the analysis (n = 876) with respect to baseline characteristics and treatment randomization (data not shown). There were no statistically significant differences among the three arms with regard to demographic and lifestyle factors at the study entry. The three treatment arms were also similar with regard to the percentage of subjects who were randomly assigned to folic acid treatment.

Table 1.

Baseline selected characteristics of the study participants with at least one biomarker measurement.

| Baseline characteristic | Placebo (N = 296) |

Aspirin 81 mg/d (N = 296) |

Aspirin 325 mg/d (N = 284) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs, mean (SD) | 57.5 (9.8) | 57.2 (9.4) | 57.6 (4.5) | 0.88 | |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 189 (63.9) | 193 (65.2) | 178 (62.7) | 0.83 | |

| White, no. (%) | 253 (85.5) | 260 (87.8) | 250 (88.0) | 0.14 | |

| BMI, kg/m2*, mean (SD) | 27.3 (4.5) | 27.3 (4.5) | 27.7 (4.8) | 0.91 | |

| Overweight, no. (%) | 140 (47.5) | 142 (48.1) | 130 (45.8) | 0.89 | |

| Obese, no. (%) | 63 (21.4) | 60 (20.3) | 70 (24.7) | ||

| Current smoker, no. (%) | 41 (13.9) | 40 (13.6) | 41 (14.5) | 0.56 | |

| Alcohol drinker, no. (%) | 199 (67.3) | 189 (63.9) | 193 (68.0) | 0.62 | |

| Multivitamin use, no. (%) | 104 (35.1) | 111 (37.5) | 96 (33.8) | 0.40 | |

| Family history of colorectal polyps, no. (%) | 62 (26.8) | 72 (29.2) | 77 (34.1) | 0.13 | |

| Adenoma characteristics (at baseline)** | |||||

| Number, mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.1) | 0.41 | |

| Advanced adenomas, no. (%)*** | 84 (36.1) | 80 (34.9) | 89 (39.6) | 0.69 | |

| Proximal location, no. (%) | 136 (54.4) | 135 (54.0) | 133 (55.0) | 0.74 | |

| Folic acid treatment group, no. (%) | 149 (51.0) | 147 (49.7) | 143 (50.7) | 0.98 | |

N=1 in the placebo, and N=1 in the aspirin 81 mg/d group had missing BMI data.

Data available for 268, 257, 243 participants in the placebo, aspirin 81 mg/d, and aspirin 325 mg/d treatment groups, respectively.

Data available for 233, 229, and 229 in the placebo, aspirin 81 mg/d, and aspirin 325 mg/d treatment groups, respectively.

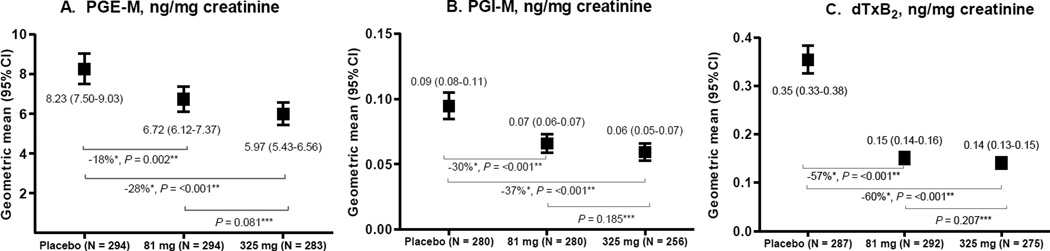

Among all study participants, urinary PGE-M levels were weakly correlated with urinary PGI-M (ρ = 0.16, P <0.001) and dTxB2 (ρ = 0.30, P <0.001), with a somewhat stronger correlation between urinary PGI-M and dTxB2 (ρ = 0.41, P <0.001). Similar correlations were found in each treatment group (data not shown). Urinary PGE-M, PGI-M and dTxB2 differed by sex, age, study center, and smoking status (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Aspirin treatment was associated with lower urinary prostanoid metabolites levels in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). Urinary PGE-M levels were proportionately 28% and 18% lower in participants who took 325 mg and 81 mg of aspirin, respectively, compared to participants who took placebo. Similar but weaker dose-dependent patterns were observed for PGI-M and dTxB2. However, the ratios of PGE-M to PGI-M, and of (dTxB2 + PGE-M) to PGI-M did not differ substantially by aspirin treatment group (Supplementary Table 3). Comparable aspirin-associated decreases in the levels of urinary prostanoid metabolites were observed in the data further stratified by the folic acid treatment arm (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1.

Urinary PGE-M (A), PGI-M (B) and dTxB2 (C) levels by aspirin treatment group, the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study.

* P-value vs. placebo. ** The proportional difference in geometric means was calculated as ([treatment group – placebo group]/placebo group)*100%. *** P-value vs. 81 mg.

There was no evidence that urinary PGE-M, PGI-M, or dTxB2 concentrations (or their ratios) were associated with risk for any adenoma: RR’s quartiles 2 through 4 were each close to 1.0, with narrow confidence intervals. Urinary PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTXB2 also had no material associations with low risk adenomas or high risk findings (Table 2). In contrast, the PGE-M, PGI-M, and to a lesser extent dTXB2, showed non-significant suggestions of decreasing RR trends with increasing urinary levels for advanced adenomas (Table 2). The ratios of PGE-M to PGI-M, and of (dTxB2 + PGE-M) to PGI-M were unassociated with risk of any adenomas class (Supplementary Table 5). None of the interactions of urinary prostanoid levels with aspirin treatment group were statistically significant (all P > 0.1). We repeated the analyses in the placebo group only and obtained similar findings (Supplementary Table 6).

Table 2.

Association of adenoma occurrence during study treatment with urinary PGE-M, PGI-M and dTxB2 levels, the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study.

| Biomarker / Quartile range |

Any adenoma | Low-risk adenoma* | High-risk findings* | Advanced adenoma* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/ total N |

RR** | 95% CI | Cases/ total N |

RR** | 95% CI | Cases/ total N |

RR** | 95% CI | Cases/ total N |

RR** | 95% CI | |||||

| PGE-M, ng/mg creatinine# | ||||||||||||||||

| <4.57 | 71/207 | 1.00 (ref) | 36/172 | 1.00 (ref) | 35/171 | 1.00 | 21/205 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||||||

| 4.57–7.37 | 77/207 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.29 | 39/169 | 1.07 | 0.72 | 1.61 | 38/168 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 1.41 | 22/204 | 0.93 | 0.51 | 1.71 |

| 7.37–11.38 | 86/210 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.28 | 45/169 | 1.08 | 0.72 | 1.60 | 41/165 | 0.91 | 0.61 | 1.35 | 16/207 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 1.11 |

| ≥11.39 | 93/211 | 1.07 | 0.83 | 1.37 | 48/166 | 1.19 | 0.80 | 1.77 | 45/163 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 1.38 | 16/205 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 1.08 |

| P trend | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| PGI-M, ng/mg creatinine# | ||||||||||||||||

| <0.049 | 70/196 | 1.00 (ref) | 33/159 | 1.00 (ref) | 37/163 | 1. (ref) | 18/194 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||||||

| 0.049–0.082 | 82/194 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 1.45 | 41/153 | 1.30 | 0.88 | 1.93 | 41/153 | 1.10 | 0.75 | 1.60 | 20/190 | 1.01 | 0.55 | 1.87 |

| 0.082–0.124 | 76/194 | 1.05 | 0.82 | 1.36 | 38/156 | 1.21 | 0.81 | 1.82 | 38/156 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 1.47 | 19/192 | 0.93 | 0.49 | 1.79 |

| ≥0.125 | 80/196 | 1.04 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 47/163 | 1.40 | 0.94 | 2.09 | 33/149 | 0.77 | 0.51 | 1.16 | 13/192 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 1.15 |

| P trend | 0.92 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 0.16 | ||||||||||||

| dTxB2, ng/mg creatinine# | ||||||||||||||||

| <0.107 | 68/199 | 1.00 (ref) | 31/162 | 1.00 (ref) | 37/168 | 1.00 (ref) | 18/196 | 1.00 (ref) | ||||||||

| 0.107–0.194 | 96/209 | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.69 | 56/169 | 1.79 | 1.22 | 2.62 | 40/153 | 1.12 | 0.75 | 1.67 | 22/207 | 1.04 | 0.55 | 1.93 |

| 0.195–0.346 | 79/206 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 1.30 | 42/169 | 1.27 | 0.83 | 1.95 | 37/164 | 0.78 | 0.50 | 1.21 | 19/200 | 0.60 | 0.29 | 1.24 |

| ≥0.347 | 77/204 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.28 | 34/161 | 1.15 | 0.70 | 1.88 | 43/170 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 16/199 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 1.00 |

| P trend | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.44 | ||||||||||||

Low-risk adenoma defined as solitary adenomatous polyp < 1 cm in greatest diameter and tubular or unknown histology (high-risk adenoma excluded from the analysis). High-risk adenoma defined as adenomatous polyp ≥1 cm in greatest diameter and/or tubulovillous, villous or high-grade dysplasia, histology or multiple (≥2) adenomatous polyps of any size or histology (low-risk adenoma excluded from the analysis). Advanced adenoma defined as adenomatous polyp with an estimated diameter of ≥1 cm, or at least 25% villous component, any high-grade dysplasia, or invasive cancer.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, center (categorical), number of previous adenomas (continuous), follow-up time (continuous) and aspirin treatment group (placebo, 81 mg, 325 mg).

P-values for interaction for aspirin treatment group were: for any adenoma,P PGE-M = 0.14,P PGI-M = 0.40, andP dTxB2 = 0.50; for low-risk adenoma,P PGE-M = 0.13,P PGI-M = 0.22, andP dTxB2 = 0.40; for high-risk adenoma,P PGE-M = 0.53,P PGI-M = 0.45, andP dTxB2 = 0.63; and for advanced adenoma,P PGE-M = 0.62,P PGI-M = 0.33, andP dTxB2 = 0.32.

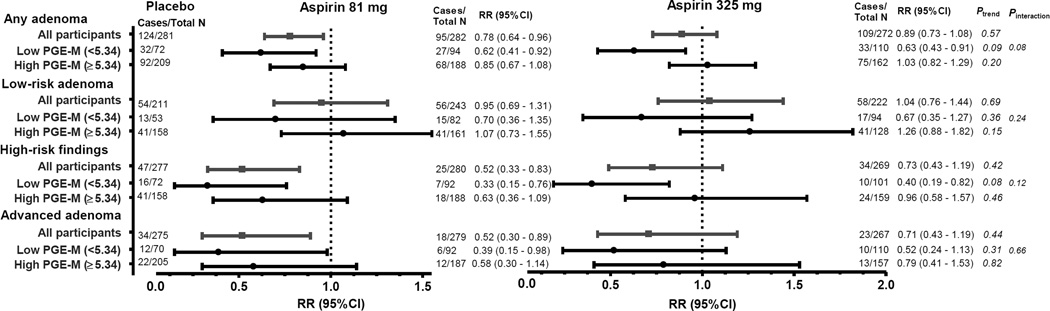

In an exploratory analysis, in which we stratified the study participants according to PGE-M levels (Figure 2), aspirin treatment was associated with a significant reduction in any and high-risk adenoma occurrence among participants with low PGE-M (<5.34 ng/mg creatinine), but not among participants with high PGE-M (≥5.34 ng/mg creatinine) concentrations; however neither of the interactions were statistically significant. A similar pattern was suggested for low-risk adenoma, whereas for advanced adenoma the aspirin treatment effects did not seem to differ by PGE-M levels. Analyses stratified by sex (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) suggested that among women, higher levels of PGE-M may be positively associated with adenoma occurrence; however, the results were based on a very small number of events and no statistically significant multiplicative interactions by sex were found.

Figure 2.

Association of adenoma occurrence during study treatment within categories of urinary PGE-M levels by aspirin treatment group, the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study. All models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex, center (categorical), number of previous adenomas (continuous), and follow-up time (continuous). Placebo was the reference group. Low PGE-M category = tertile 1, High PGE-M category = tertile 2 & tertile 3.

Two participants in the low-dose aspirin group and three in the high-dose aspirin group were classified as aspirin resistant based on dTxB2 > 1.5 ng/mg creatinine (>67.9 ng/mmol of creatinine)(44, 45). Among the 5 participants, one did not take the study treatment (0% compliance). The exclusion of these subjects from the analysis had no effect on the risk estimates (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of individuals participating in a randomized clinical trial, aspirin treatment was associated with lower levels of urinary prostanoids in a dose-dependent manner: participants who took high-dose aspirin had the lowest concentrations of PGE-M, PGI-M, and dTxB2 compared to participants who took low-dose of aspirin or placebo. None of the urinary prostanoid metabolites or their ratios were significantly associated with risk of any measure of adenoma risk.

The levels of COX-derived PGE2 and its synthase are increased in colorectal neoplasia as compared with histologically normal tissue.(16, 46, 47) PGE2 has been shown to inhibit apoptosis, promote cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration, and activate Wnt signaling (48, 49). In previous studies, the major urinary metabolite of PGE2, PGE-M, has been strongly directly associated with the risk of colorectal cancer (50) and (contrary to our findings) with multiple and/or advanced adenoma (RR ranging from 1.66 to 2.19 comparing the highest vs. lowest quartiles) (34, 35). Conversely, in our study, the association pattern for PGE-M with advanced adenomas was non-significantly suggestive of an inverse association. In agreement with our results, previous studies have not found an association with single small tubular adenoma (34, 35) or any adenoma (35). There are no previous data regarding the associations of metabolites of PGI2 and thromboxane with risk of colorectal cancer or adenomas of any type.

Our data suggested that aspirin treatment was associated with a significant reduction in adenoma occurrence in participants with low PGE-M, measured near the end of treatment. This is expected, since both adenoma occurrence and low PGE-M levels are associated with aspirin use and so are logically associated with each other. Trial participants on aspirin tended to have low PGE-M and also had the lowest adenoma risk. On the other hand, participants with high PGE-M tended to be placebo subjects (or aspirin subjects resistant to treatment) and had a higher risk for adenomas. Bezawada et al (35) also investigated this issue, and reported the opposite pattern: stronger aspirin/NSAIDs associations in women with higher urinary PGE-M. To the extent that their samples were truly baseline (taken before starting aspirin), their data are logical and do not conflict with ours. However, to the extent their data were taken “on treatment” (during aspirin/NSAID use) the two studies disagree. It is not clear whether their samples were truly baseline as they were collected at the same time as information on aspirin/NSAID use.

Thromboxane is essential to platelet activation, and the antiplatelet effect of aspirin through inhibition of thromboxane synthesis seems to be relevant to its anti-neoplastic actions (11). It has been proposed that activated platelets promote COX-2 upregulation in adjacent cells of the colorectal mucosa at sites of mucosal injury via paracrine lipid (e.g., TXA2) or protein (e.g., interleukin-1β) mediators (11). There may also be direct effects of TXA2 itself, as mucosal levels stimulate proliferation, promote metastases, and mediate COX-2-dependent angiogenesis (13, 51–53). Elevated levels of TXA2 and thromboxane synthase in colorectal neoplasms have been reported, (13, 17) and colon cancer cells that overexpress the TXA2 synthase gene grow faster and exhibit more abundant vasculature (12). In our study, higher levels of dTxB2, a major urinary metabolite of TXA2, were not associated with the risk of any adenoma. In contrast to our initial hypothesis, the association pattern for dTxB2 was suggestive of an inverse association for advanced adenoma at the end of study follow-up among all and placebo-only participants.

Prostacyclin PGI2, a prostaglandin downstream of COX-1 and COX-2 (54), has important roles in cardiovascular homeostasis, and may also influence carcinogenesis. Expression of PGI2 seems reduced in lung cancers (15), and administration of a PGI2 analogue improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers (18). Colon cancer cells that overexpress the prostacyclin synthase gene (PTGIS) grow more slowly and with less developed vasculature than control inoculants (12). Epigenetic inactivation of the PTGIS is common in colorectal cancer (19), and reduced tumor tissue levels of PGI2 compared with adjacent normal mucosa have been reported (16, 17). Furthermore, a polymorphism associated with reduced activity of the PTGIS gene has been associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenomas and a blunting of the protective effect of NSAIDs (20). Our results show that PGI-M, a major urinary metabolite of PGI2, was not associated with any adenoma, but – in agreement with our initial hypothesis – higher levels of PGI-M were non-significantly inversely associated with advanced adenoma.

Although numerous epidemiological studies and several randomized clinical trials reported that aspirin is protective against colorectal neoplasms (1–5); it is unknown exactly how it exerts its anti-neoplastic effects, and why the lower aspirin dose seems more effective in preventing colorectal adenomas. The main proposed mechanism so far includes inhibition of COX enzymes. We also hypothesized that a trade-off between pro-carcinogenic PGE2 and/or TXA2, and putatively anti-carcinogenic PGI2 may explain a protective effect of lower dose aspirin. However, our findings did not suggest that differential inhibition of prostanoids explains the paradoxical aspirin effects, nor support the COX-dependent anti-neoplastic effects of aspirin, as urinary prostanoid metabolites were not associated with risk for colorectal adenoma occurrence. It is possible that COX-independent effects of aspirin are involved, including inhibition of PPARδ (55) and oxidative DNA damage (56), modulation of polyamine metabolism (57) and Wnt signaling (58), activation of the NF-kB signaling pathway resulting in apoptosis (59), increase in leukotriene production as a result of shuttling of free arachidonic acid between COXs and lipoxygenases pathways (58), and activation of the NSAID-activated gene (NAG-1) (60), which is a member of the TGF-β family that has pro-apoptotic and anti-tumorigenic activities (61).

This study has several limitations. First, participants in this analysis had a previous history of at least one colorectal adenoma, potentially limiting the generalizability of the data. In particular, it is possible that the colorectal mucosa that has had prior adenoma may already have altered prostanoid signaling (e.g., a deficiency in 5-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase [15-PGDH]), which may efface the differences in levels between those who do, and do not, have a recurrent adenoma on a later colonoscopy. Second, we did not measure the prostanoids concentrations at the study entry, as we did not collect urinary samples at that time. However, the on-treatment measurements better reflect the subjects’ metabolic milieu during the period the adenomas were forming. Third, the ratios of PGE-M and dTxB2, individually and in combination, to PGI-M may not adequately capture trade-off between systemic productions of these prostanoids. Fourth, treatment effects of aspirin on the prostanoid synthesis in the colon mucosa are unclear, as we did not measure the expression of prostanoids in the colorectal tissue. Finally, we had a limited sample size to investigate risk of advanced adenoma occurrence.

The strengths of this study include the randomized, placebo-controlled trial design; high protocol adherence by study participants; the high follow-up rate; and the systemic collection of risk factor information at baseline and follow-up intervals as well as outcomes at the end of treatment. Another strength of this study is that we measured stable biomarkers of systemic production of prostanoids using highly sensitive assays in one laboratory. Finally, this study is the first human study to investigate the association between PGI-M and dTxB2 and risk of colorectal adenoma.

Overall, in this study, we found that low- and high-dose aspirin is associated with lower levels of urinary prostanoid metabolites in a dose-dependent manner. However, our findings provided no evidence that urinary prostanoid metabolites are associated with reduced risk of colorectal adenoma occurrence. In agreement with our original hypothesis, we observed a possible inverse association of metabolites of the possibly anti-carcinogenic prostanoid PGI2 with advanced adenoma occurrence. However similar inverse associations were observed for other potentially pro-carcinogenic prostanoids. Studies of colorectal neoplasms that measure changes in both systemic and tissue-specific levels of prostanoids in response to aspirin treatment are needed to confirm our results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the subjects in the trial for their dedication and cooperation.

Funding: This study was funded by the US Public Health Service, grant CA059005. Dr. Bradshaw was supported by National Institute of Health training award K12CA120780

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Dr. Baron and Dartmouth College hold a use patent for the chemopreventive use of aspirin, currently not licensed.

References

- 1.Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet. 2007;369:1603–1613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen D, Bresalier R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:891–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, Budinger S, Paskett E, Keresztes R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:883–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan RF, Grainge MJ, Shepherd VC, Armitage NC, Muir KR. Aspirin and folic acid for the prevention of recurrent colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:29–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benamouzig R, Deyra J, Martin A, Girard B, Jullian E, Piednoir B, et al. Daily soluble aspirin and prevention of colorectal adenoma recurrence: one-year results of the APACC trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:328–336. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole BF, Logan RF, Halabi S, Benamouzig R, Sandler RS, Grainge MJ, et al. Aspirin for the chemoprevention of colorectal adenomas: meta-analysis of the randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:256–266. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubois RN, Abramson SB, Crofford L, Gupta RA, Simon LS, Van De Putte LB, et al. Cyclooxygenase in biology and disease. FASEB J. 1998;12:1063–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha YI, DuBois RN. NSAIDs and cancer prevention: targets downstream of COX-2. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:239–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marnett LJ, DuBois RN. COX-2: a target for colon cancer prevention. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:55–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082301.164620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bambace NM, Holmes CE. The platelet contribution to cancer progression. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, Patrono C. The role of aspirin in cancer prevention. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2012;9:259–267. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pradono P, Tazawa R, Maemondo M, Tanaka M, Usui K, Saijo Y, et al. Gene transfer of thromboxane A(2) synthase and prostaglandin I(2) synthase antithetically altered tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2002;62:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai H, Suzuki T, Takahashi Y, Ukai M, Tauchi K, Fujii T, et al. Upregulation of thromboxane synthase in human colorectal carcinoma and the cancer cell proliferation by thromboxane A2. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3368–3374. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cathcart MC, O'Byrne KJ, Reynolds JV, O'Sullivan J, Pidgeon GP. COX-derived prostanoid pathways in gastrointestinal cancer development and progression: novel targets for prevention and intervention. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1825:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cathcart MC, Reynolds JV, O'Byrne KJ, Pidgeon GP. The role of prostacyclin synthase and thromboxane synthase signaling in the development and progression of cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1805:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigas B, Goldman IS, Levine L. Altered eicosanoid levels in human colon cancer. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bing RJ, Miyataka M, Rich KA, Hanson N, Wang X, Slosser HD, et al. Nitric oxide, prostanoids, cyclooxygenase, and angiogenesis in colon and breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3385–3392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keith RL, Blatchford PJ, Kittelson J, Minna JD, Kelly K, Massion PP, et al. Oral iloprost improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers. Cancer prevention research. 2011;4:793–802. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frigola J, Munoz M, Clark SJ, Moreno V, Capella G, Peinado MA. Hypermethylation of the prostacyclin synthase (PTGIS) promoter is a frequent event in colorectal cancer and associated with aneuploidy. Oncogene. 2005;24:7320–7326. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole EM, Bigler J, Whitton J, Sibert JG, Potter JD, Ulrich CM. Prostacyclin synthase and arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase polymorphisms and risk of colorectal polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:502–508. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes CJ, Hamby-Mason RL, Hardman WE, Cameron IL, Speeg KV, Lee M. Effect of aspirin on prostaglandin E2 formation and transforming growth factor alpha expression in human rectal mucosa from individuals with a history of adenomatous polyps of the colon. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frommel TO, Dyavanapalli M, Oldham T, Kazi N, Lietz H, Liao Y, et al. Effect of aspirin on prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 production in human colonic mucosa from cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan K, Ruffin MT, Normolle D, Shureiqi I, Burney K, Bailey J, et al. Colonic mucosal prostaglandin E2 and cyclooxygenase expression before and after low aspirin doses in subjects at high risk or at normal risk for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:447–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruffin MTt, Krishnan K, Rock CL, Normolle D, Vaerten MA, Peters-Golden M, et al. Suppression of human colorectal mucosal prostaglandins: determining the lowest effective aspirin dose. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1152–1160. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.15.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sample D, Wargovich M, Fischer SM, Inamdar N, Schwartz P, Wang X, et al. A dose-finding study of aspirin for chemoprevention utilizing rectal mucosal prostaglandin E(2) levels as a biomarker. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerletti C, Dell'Elba G, Manarini S, Pecce R, Di Castelnuovo A, Scorpiglione N, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences between two low dosages of aspirin may affect therapeutic outcomes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1059–1070. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De La Cruz JP, Gonzalez-Correa JA, Guerrero A, Marquez E, Martos F, Sanchez De La Cuesta F. Differences in the effects of extended-release aspirin and plain-formulated aspirin on prostanoids and nitric oxide in healthy volunteers. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:363–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FitzGerald GA, Oates JA, Hawiger J, Maas RL, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Lawson JA, et al. Endogenous biosynthesis of prostacyclin and thromboxane and platelet function during chronic administration of aspirin in man. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:676–688. doi: 10.1172/JCI110814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tohgi H, Konno S, Tamura K, Kimura B, Kawano K. Effects of low-to-high doses of aspirin on platelet aggregability and metabolites of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin. Stroke. 1992;23:1400–1403. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.10.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta JL, Mehta P, Lopez L, Ostrowski N, Aguila E. Platelet function and biosynthesis of prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 in whole blood after aspirin administration in human subjects. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1984;4:806–811. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin C, Varner MW, Branch DW, Rodgers G, Mitchell MD. Dose-related effects of low dose aspirin on hemostasis parameters and prostacyclin/thromboxane ratios in late pregnancy. Prostaglandins. 1996;51:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(96)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao XR, Adhikari CM, Peng LY, Guo XG, Zhai YS, He XY, et al. Efficacy of different doses of aspirin in decreasing blood levels of inflammatory markers in patients with cardiovascular metabolic syndrome. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2009;61:1505–1510. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.11.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen DJ, Bresalier RS, et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:2351–2359. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shrubsole MJ, Cai Q, Wen W, Milne G, Smalley WE, Chen Z, et al. Urinary prostaglandin E2 metabolite and risk for colorectal adenoma. Cancer prevention research. 2012;5:336–342. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bezawada N, Song M, Wu K, Mehta RS, Milne GL, Ogino S, et al. Urinary PGE-M levels are associated with risk of colorectal adenomas and chemopreventive response to anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Prev Res. 2014 doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphey LJ, Williams MK, Sanchez SC, Byrne LM, Csiki I, Oates JA, et al. Quantification of the major urinary metabolite of PGE2 by a liquid chromatographic/mass spectrometric assay: determination of cyclooxygenase-specific PGE2 synthesis in healthy humans and those with lung cancer. Anal Biochem. 2004;334:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oates JA, FitzGerald GA, Branch RA, Jackson EK, Knapp HR, Roberts LJ., 2nd Clinical implications of prostaglandin and thromboxane A2 formation (1) The New England journal of medicine. 1988;319:689–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809153191106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweer H, Meese CO, Seyberth HW. Determination of 11 alpha-hydroxy-,15-dioxo-2,3,4,5,20-pentanor-19-carboxyprostan oic acid and 9 alpha,11 alpha-dihydroxy-15-oxo-2,3,4,5,20-pentanor-19-carboxyprostanoi c acid by gas chromatography/negative ion chemical ionization triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:54–58. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piper PJ, Vane JR, Wyllie JH. Inactivation of prostaglandins by the lungs. Nature. 1970;225:600–604. doi: 10.1038/225600a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohebati A, Milne GL, Zhou XK, Duffield-Lillico AJ, Boyle JO, Knutson A, et al. Effect of zileuton and celecoxib on urinary LTE4 and PGE-M levels in smokers. Cancer prevention research. 2013;6:646–655. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daniel VC, Minton TA, Brown NJ, Nadeau JH, Morrow JD. Simplified assay for the quantification of 2,3-dinor-6-keto-prostaglandin F1 alpha by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of chromatography B, Biomedical applications. 1994;653:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)e0432-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrow JD, Minton TA. Improved assay for the quantification of 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of chromatography. 1993;612:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80161-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American journal of epidemiology. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fritsma GA, Ens GE, Alvord MA, Carroll AA, Jensen R. Monitoring the antiplatelet action of aspirin. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2001;14:57–58. 61–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lordkipanidze M, Pharand C, Schampaert E, Turgeon J, Palisaitis DA, Diodati JG. A comparison of six major platelet function tests to determine the prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with stable coronary artery disease. European heart journal. 2007;28:1702–1708. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mal M, Koh PK, Cheah PY, Chan EC. Ultra-pressure liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry targeted profiling of arachidonic acid and eicosanoids in human colorectal cancer. Rapid communications in mass spectrometry : RCM. 2011;25:755–764. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshimatsu K, Golijanin D, Paty PB, Soslow RA, Jakobsson PJ, DeLellis RA, et al. Inducible microsomal prostaglandin E synthase is overexpressed in colorectal adenomas and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3971–3976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenhough A, Smartt HJ, Moore AE, Roberts HR, Williams AC, Paraskeva C, et al. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:377–386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buchanan FG, DuBois RN. Connecting COX-2 and Wnt in cancer. Cancer cell. 2006;9:6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai Q, Gao YT, Chow WH, Shu XO, Yang G, Ji BT, et al. Prospective study of urinary prostaglandin E2 metabolite and colorectal cancer risk. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5010–5016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nie D, Lamberti M, Zacharek A, Li L, Szekeres K, Tang K, et al. Thromboxane A(2) regulation of endothelial cell migration, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2000;267:245–251. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daniel TO, Liu H, Morrow JD, Crews BC, Marnett LJ. Thromboxane A2 is a mediator of cyclooxygenase-2-dependent endothelial migration and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4574–4577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dovizio M, Alberti S, Guillem-Llobat P, Patrignani P. Role of platelets in inflammation and cancer: novel therapeutic strategies. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;114:118–127. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricciotti E, Yu Y, Grosser T, Fitzgerald GA. COX-2, the dominant source of prostacyclin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219073110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He TC, Chan TA, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. PPARdelta is an APC-regulated target of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cell. 1999;99:335–345. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsu CS, Li Y. Aspirin potently inhibits oxidative DNA strand breaks: implications for cancer chemoprevention. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;293:705–709. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughes A, Smith NI, Wallace HM. Polyamines reverse non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced toxicity in human colorectal cancer cells. The Biochemical journal. 2003;374:481–488. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kashfi K, Rigas B. Non-COX-2 targets and cancer: expanding the molecular target repertoire of chemoprevention. Biochemical pharmacology. 2005;70:969–986. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stark LA, Reid K, Sansom OJ, Din FV, Guichard S, Mayer I, et al. Aspirin activates the NF-kappaB signalling pathway and induces apoptosis in intestinal neoplasia in two in vivo models of human colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:968–976. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baek SJ, Kim KS, Nixon JB, Wilson LC, Eling TE. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors regulate the expression of a TGF-beta superfamily member that has proapoptotic and antitumorigenic activities. Molecular pharmacology. 2001;59:901–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eling TE, Baek SJ, Shim M, Lee CH. NSAID activated gene (NAG-1), a modulator of tumorigenesis. Journal of biochemistry and molecular biology. 2006;39:649–655. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.