Abstract

In electron tomography, accurate alignment of tilt series is an essential step in attaining high-resolution 3D reconstructions. Nevertheless, quantitative assessment of alignment quality has remained a challenging issue, even though many alignment methods have been reported. Here, we report a fast and accurate method, tomoAlignEval, based on the Beer-Lambert law, for the evaluation of alignment quality. Our method is able to globally estimate the alignment accuracy by measuring the goodness of log-linear relationship of the beam intensity attenuations at different tilt angles. Extensive tests with experimental data demonstrated its robust performance with stained and cryo samples. Our method is not only significantly faster but also more sensitive than measurements of tomogram resolution using Fourier shell correlation method (FSCe/o). From these tests, we also conclude that while current alignment methods are sufficiently accurate for stained samples, inaccurate alignments remain a major limitation for high resolution cryo-electron tomography.

Keywords: electron tomography, Beer-Lambert law, inelastic scattering, least square fitting, cross validation, alignment accuracy

1. Introduction

Electron tomography (ET) is an emerging technique capable of revealing the 3D structure of complex macromolecular architectures and cellular ultrastructure. A 3D tomogram of the specimen is reconstructed from a series of 2D projection images at different tilt angles. To correct the specimen drift due to instability of the instrument, accurate alignment of the tilt series is a prerequisite to obtaining a high-resolution tomographic reconstruction.

The alignment methods for ET tilt series can be classified into two categories: fiducial marker-based and marker-free alignment methods. Marker-based methods track the positions of high-contrast gold beads over the entire tilt series, and fit them into a projection model in order to determine the alignment parameters (Brandt and Ziese, 2006; Han et al., 2014; Jones and Harting, 2013; Mastronarde, 2006). Marker-free alignment can be further divided into two types, correlation-based and feature-based methods, which rely on cross-correlations between adjacent image pairs within the tilt series (Brandt and Ziese, 2006) and identify features in images as virtual markers (Brandt, 2006), respectively. In addition, 3D model-based approaches were also developed employing projection matching which is commonly used in single particle analysis (Brandt, 2006; Winkler and Taylor, 2006).

Although there are multiple approaches to align the tilt series, quantitative assessment of alignment quality remains a critical issue for achieving high-resolution reconstruction. Most alignment methods use the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the measured and expected positions of fiducials based on least-square metric to evaluate the alignment quality (Mastronarde, 2006). It is inevitable that these methods are sensitive to outliers from a few unreliably tracked fiducials, and can be arbitrarily minimized by manual over-tuning of the bead positions. The most rigorous evaluation of alignment accuracy is to measure the resolution of the reconstructed tomogram (Cardone et al., 2005) and use the resolution as an indication of alignment quality. However, it measures the compound effect of many factors, including data quality, alignment accuracy, CTF fitting/correction, and 3D reconstruction. Furthermore, it is also computationally intensive for large datasets (Cardone et al., 2005) and is usually only done after the tomogram has already been reconstructed using the aligned images.

To remedy these problems, we have developed a fast and robust approach to estimate the quality of 2D alignment. Our approach is based on a mathematical model derived from the Beer-Lambert law and computes the total error between the image data and the image formation model, allowing us to globally assess the alignment quality with a merit figure.

2. Method

2.1 Mathematical model

When the electron beam passes through sample, the electrons will pass through without being scattered, or can be elastically or inelastically scattered. The inelastic scattering will reduce the electron wave amplitude and the beam intensity. The incident beam intensity I0 and the transmitted beam intensity Iexit follow the Beer-Lambert law, no matter whether inelastically scattered electrons are removed by energy filter. Based on the Beer-Lambert law, the beam intensity attenuates exponentially with increasing thickness of the sample. This relationship can be described in Eq. (1)

| (1) |

where de is the effective thickness representing the distance that the electron beam has traveled through in the specimen, Λin is the mean free path for inelastic scattering, I0 is the intensity of incident electron beam and Iexit is the intensity of electron beam exiting the specimen and hitting the detector. The Beer-Lambert law has been used in electron tomography to estimate sample thickness (Cho et al., 2013; Malis et al., 1988; Zhang et al., 2012) or model the image formation process (Venkatakrishnan et al., 2013).

Note that the effective thickness de in Eq. (1) is not equal to the absolute geometric thickness d0 due to tilt angle θ. We can compute the effective thickness de in Eq. (2) using the geometric relationship:

| (2) |

Furthermore, the exiting beam intensity Iexit can be represented as Eq. (3) to associate it with the pixel values we measure from images

| (3) |

where Iimage is the average pixel value of the selected area from the image, A is the gain factor of the detector.

Thus, we can transform our mathematical model for a tilted image to Eq. (4) by combining Eqs. (1-3)

| (4) |

and alternatively on a log-scale

| (5) |

Assuming A, I0, Λin and d0 are constant, there is a linear relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable ln(Iimage) in the aligned image series.

2.2 Quantitative assessment of alignment quality

The approach consists of several steps as described below:

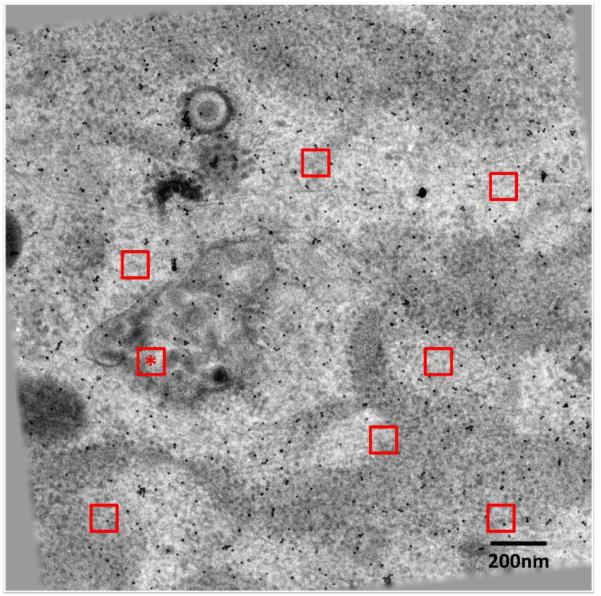

(1) Multiple regions (8 regions for the example shown in Fig. 1) are selected in the untilted image and the corresponding patches in the entire tilt series are tracked according to the tilt angles and the geometric relationship. The patch size in the X-dimension (Nx(θ), perpendicular to the tilt axis along the Y-dimension) can either remain constant or adapt to the reduced sizes for tilted images (Nx(θ) = Nx(0)cosθ ).

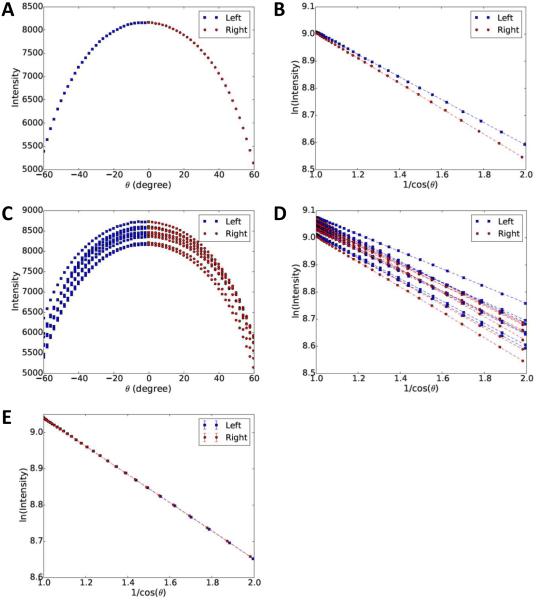

(2) For each selected region, the average pixel value of each tracked patch is used as the measured Iimage (Fig. 2A).

(3) Based on Eq. (5), it can be seen that ln(Iimage) and follow a linear trend if the tilt series is accurately aligned (Fig. 2B). Each selected region would contribute two linear trends, one for negative tilts and one for positive tilts. When multiple regions (for example, 8 regions as shown by the red boxes in Fig. 1) were selected, separate linear trends can be seen due to different image contents in different selected regions (Fig. 2C, D). Among all linear trends, we found the median slope and the median intercept and used them as the reference to re-scale all linear trends to this common slope and intercept. For example, if we want to rescale the n-th linear trend (yn = knx + bn) to the median slope kmedian and the median intercept bmedian, the rescaled n-th linear trend will be . We then computed the mean and standard deviation of the re-scaled data points of all regions at each tilt angle (Fig. 2E). Thus, averaging of multiple regions was performed to reduce noise. In the final averaged plot (Fig. 2E), the number of points is equal to the number of tilts, with every point and its error bar representing the average pixel values and the standard deviation of different regions.

-

(4) Based on the mean pixel values for the different tilts obtained in the previous step, we generated a line fitting f by linear regression in which kfit is the slope and bfit is the intercept.

where i is the ith image in the tilt series.(6) -

(5) The squared error between the fitting line f in Eq. (6) and the averaged data at each tilt angle is computed and denoted as residual res(i).

(7) The mean and standard deviation of all res values from the entire tilt series (Fig. 3E) serve as global quantitative indicators of goodness-of-alignment.

Fig. 1. Zero tilt image of an aligned tilt series of Sindbis virus infected BHK cell section.

The infected cells were plastic embedded, sectioned, and then stained before being imaged. The tilt axis is vertical. The 8 red squares indicate regions selected and tracked through the tilt series. The region size is 100×100 pixels.

Fig. 2. Relationship between image intensity and tilt angles.

(A) Profile of image intensity and tilt angle (θ) for the red square region marked with symbol * shown in Fig. 1. The blue squares and red circles indicate left and right branches, corresponding to negative and positive tilts, respectively. The images were taken in order of negative to positive tilt angles. (B) Replot of (A) using log of intensity (Y-axis) and 1/cosθ (X-axis). Colors are the same as in (A). The two dash lines indicate independent linear regression to points of two branches. (C, D) Expansion of plots (A) and (B) to include multiple regions. (E) Plots in (D) are rescaled and averaged using a common reference line with median slope. The errors are too small to make the error bars visible.

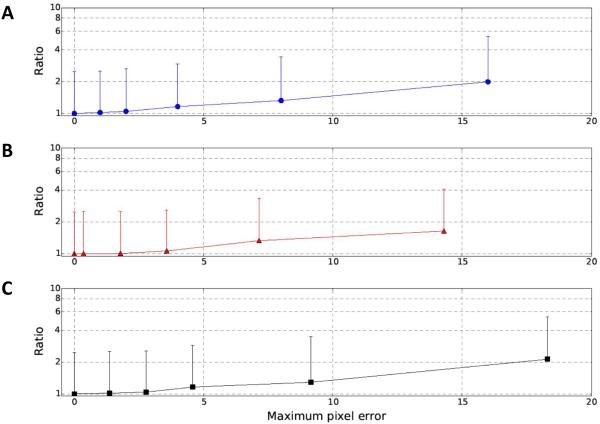

Fig. 3. Quantitative tests with computationally added alignment errors.

A series of random errors, including shifts (A), in-plane rotations (B), and combination of shifts and in-plane rotations (C), were added to the aligned stack of stained cell section (same dataset shown in Figs. 1 and 2). The X-axis values represent a maximum pixel error up to the value (Joyeux and Penczek, 2002). The points and error bars indicate mean and standard deviation of residuals, respectively. Note that the mean residual of aligned stack is set as 1 here and all other mean and standard deviation are represented as ratios. A different random error was used for each image of the aligned tilt series.

2.3 Implementation

The method described here has been implemented as a stand-alone python program tomoAlignEval.py for easy usage. Several parameters, such as, patch locations, patch size and patch type (constant or adaptive), were provided as command line options to give users the flexibilities to experiment for diverse samples. EMAN2 library functions (Tang et al., 2007) were used for image IO. numpy/scipy software was used to perform linear least square fitting and matplotlib software was used for plotting. Although the program was only tested on Linux systems, it should also run on all major platforms (Linux, Windows and MacOS) on which the dependent software packages (python, numpy, scipy, matplotlib and EMAN2) are supported. The tomoAlignEval.py program will be freely downloadable after publication from the authors’ Web site (http://jiang.bio.purdue.edu).

2.4 Test datasets

Both stained and cryo datasets were used to test the performance of our approach. Sindbis virus infected Baby Hamster Kidney fibroblasts (BHK) cells and Flock House virus infected Drosophila S2 cells were embedded in resins, sectioned, and then stained. Tilt series of both samples were obtained on a FEI Titan Krios at 300 kV and were recorded on a Gatan 4K×4K CCD camera at room temperature. The samples were first pre-irradiated (~104 e/Å2) to stabilize the resin and minimize specimen shrinkage during data collection (Braunfeld et al., 1994). Tilt images were collected from −60° to +60° in 2° increments with constant dose for each tilt and a total dose of 4000 e/Å2. The pixel size was 0.404 nm for the datasets used in Fig. 5D, 0.51 nm for datasets of other stained samples. For cryo-datasets, the frozen-hydrated specimens, purified Sindbis virus and Borrelia burgdorferi, were plunge frozen and imaged at liquid nitrogen temperature. The tilt series of purified Sindbis virus were acquired using a FEI Polara TEM at 300 kV on a Tietz 4K×4K CCD and the tilt series of Borrelia burgdorferi were acquired using a JEOL 2200 TEM with energy filter at 200 kV on a Gatan 4K×4K CCD camera. Tilt images were taken from −60° to +60° in 1° increment and 1.5° increment for purified Sindbis virus and Borrelia burgdorferi, respectively, with constant dose for each tilt and a total dose of 100 e/Å2. The images of purified Sindbis virus were 2x binned to 2048×2048 pixels. The pixel size was 0.45 nm for the datasets used in Fig. 5H, 0.55 nm for other cryo datasets.

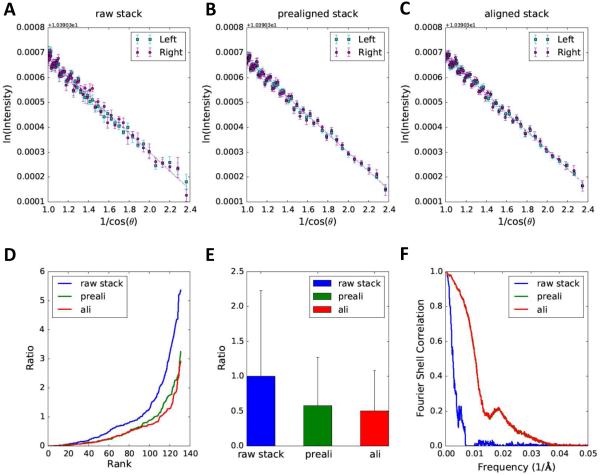

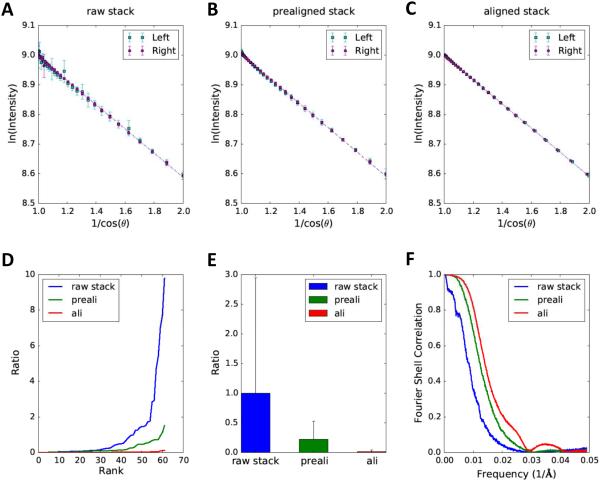

Fig. 5. Quantitative comparison of alignment quality for raw stack, prealigned stack and aligned stack of cryo dataset.

The linear patterns of log intensity as a function of 1/cosθ are shown for the raw stack (A), prealigned stack (B) and aligned stack (C). (D) Sorted residual plot of the three stacks. Note that the mean residual of raw stack is set as 1 and all residuals are represented as ratios. (E) The bar graph illustrates the statistical analysis (mean ± standard deviation) of residuals from 16 selected regions. The region size is 200×200 pixels. (F) The plot depicts resolution comparisons for tomographic reconstructions of raw stack, prealigned stack and aligned stack on the basis of FSCe/o.

All tilt series were aligned using gold fiducial markers with the IMOD software package (Kremer et al., 1996). For each tilt series, raw stack, pre-aligned stack and aligned stack were all used to test if our method can effectively distinguish their alignment qualities. Tomographic reconstruction of raw stack, pre-aligned stack and aligned stack were performed using the back projection method implemented in IMOD. The FSCe/o curves, Fourier shell correlation of two tomograms built from even and odd subsets of tilt images, were computed using ELECTRA (Cardone et al., 2005).

3. Results

3.1 Experimental confirmation of the mathematical model

To confirm that the mathematical model (Eqs. 4 and 5) derived from the Beer-Lambert law is indeed consistent with experimental tomographic tilt images, we plotted the mean pixel values at different tilt angles. One region (100×100 pixels, the red square marked with symbol * in Fig. 1) was selected from the untilted image, and tracked through the entire aligned tilt series according to its geometric relationship. The average pixel values (Iimage in Eq. 3) of all tracked patches were plotted as a function of tilt angles in Fig. 2A. When the tilt angles become larger, the effective thickness de increases, leading to exponential attenuation of beam intensity. The distribution of average pixel values depicts a parabolic curve which is qualitatively consistent with the theoretical model shown in Eq. (4), since the tilt angles at positive and negative directions should produce the same effective thickness and the same intensity.

To better illustrate the tilt-angle dependence for the beam intensity, Fig. 2A was replotted in Fig. 2B to show the log of intensity as a function of . It is now evident that there is a linear relationship (dash line) between and ln(Iimage) in aligned image series, in excellent agreement with the Beer-Lambert law based mathematical model shown in Eq. (5). For convenience, the curve in Fig. 2A was divided into left (blue squares) and right (red circles) branches, corresponding to negative and positive tilts during data collection, respectively. The two branches were transformed to log scale in Fig. 2B and marked with the corresponding colors and symbols used in Fig. 2A. When multiple regions (8 red squares as shown in Fig. 1) are plotted, multiple parabolic curves and straight lines are present, with one region for each set of curves (Fig. 2C) or lines (Fig. 2D). The curves/lines are offset from each other due to differences in the contents of different regions, which cause different attenuation rates of the beam and brightnesses in the tilt images. In Fig. 2E, all linear trends were scaled to the median slope and the median intercept, and rescaled data points at same tilt angle but from different regions were then averaged. The point and its error bar in Fig. 2E represent the mean and standard deviation of intensities of different regions after rescaling. It can be seen that all the points form a nearly perfect line with no point visibly offset from the line. The error bar of each point in Fig. 2E is too small to be visible. These results have confirmed that our theoretic model (Eq. 5) is indeed consistent with aligned experimental images.

3.2 Tests with computationally added alignment errors

To use the goodness of log-linear relationship as a quantitative measurement of the alignment quality of tilt series, a strong correlation of these two properties is required. We thus performed tests in which a series of perturbations (Joyeux and Penczek, 2002), including shifts (Fig. 3A), in-plane rotations (Fig. 3B), and combinations of shifts and in-plane rotations (Fig. 3C), were purposely applied to an aligned stack images shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 3, the points and error bars correspond to mean and standard deviation of the residuals defined in Eq. 7. The mean residual of the aligned stack was set at 1 and all other values were shown as ratios to the mean residual of the aligned stack without additional alignment perturbations. The results (e.g. mean and standard deviation of residuals) showed a strong positive correlation with the applied perturbations to the alignments. Both the mean and standard deviation increase with larger applied perturbations, indicating that our method is able to distinguish the different amounts of alignment errors for a tilt series.

3.3 Quantitative assessment of alignment quality of stained samples

To assess the performance of the proposed method, we tested experimental datasets of both stained and cryo specimens. Fig. 4 displays the intensities of the same regions (100×100 pixels) in the raw stack (Fig. 4A), the prealigned stack (Fig. 4B) and the aligned stack (Fig. 4C) of a dataset of stained sections of a Sindbis virus infected BHK cell.

Fig. 4. Quantitative comparison of alignment quality for raw stack, prealigned stack and aligned stack of stained sample.

The linear patterns of log intensity as a function of 1/cosθ are shown for the raw stack (A), prealigned stack (B) and aligned stack (C). (D) Sorted residual plot of the three stacks. Note that the mean residual of raw stack is set at 1 and all residuals are represented as ratios. (E) The bar graph illustrates the statistical analysis (mean ± standard deviation) of residuals from 10 selected regions. The column denotes mean and the error bar denotes standard deviation. The region size is 100×100 pixels. (F) The plot depicts resolution comparisons for tomographic reconstructions of raw stack, prealigned stack and aligned stack on the basis of FSCe/o. The small dip at around 0.03 Å−1 in the curve of aligned stack (red curve) reflects the first CTF zero frequency of the mean defocus (~5.8 µm) for this dataset.

Here, the prealigned stack and aligned stack refer to the tilt series produced by coarse alignment using cross-correlation method and fine alignment using fiducial marker based method provided in IMOD, respectively. As can be seen from Fig. 4A, the data points of the raw stack usually have larger standard deviation on each data point and multiple outliers are significantly offset from the fitting line (dash line), representing a very poor alignment quality for the raw stack. In contrast, Fig. 4B shows most of the data points of the prealigned stack follow the linear trend with smaller standard deviation, though a few of them still slightly deviate from the fitting line, suggesting that the prealigned stack has a better quality of alignment. In addition, the data points of the aligned stack present a linear relationship with invisible standard deviation and perfectly match the fitting line, demonstrating that marker-based alignment is able to significantly improve the alignment quality in this case. The comparison shown in Fig. 4A-C confirms that the goodness of linear trend of data points is correlated with the alignment quality, supporting the concept of our mathematical model.

To quantitatively analyze the alignment accuracy, we computed the residuals between data points and the fitting line (Eq. 7) of each stack and compared them statistically. As shown in Fig. 4D, we first sorted all residuals of one stack, set the mean residual of raw stack as 1, and used it as a reference to convert all residuals to ratios, aiming to intuitively show how much the residuals are reduced by coarse and fine alignment, respectively. We found those with largest residuals are mostly from high tilt angles. It is evident that, as expected, the raw stack has largest residuals (blue line in Fig. 4D), while the aligned stack has the smallest residuals (red line in Fig. 4D). These sorted plots also provide clear clues to the tilts with largest alignment errors that need to be further investigated. We also computed the mean and standard deviation of residuals of each stack and used them as a global figure of merit of alignment (Fig. 4E). As shown in Fig. 3E, the improvement of alignment quality from raw stack to aligned stack is accompanied with significant reduction of mean and standard deviation of residuals. The mean of residuals of final aligned stack is decreased to less than 2% of that of raw stack (Fig. 4E). The marker based fine alignment is thus able to considerably boost the alignment accuracy over the correlation based prealignment. It is evident that our method is capable of evaluating and revealing the difference of alignment quality at different stages of alignment.

To further corroborate the effectiveness of our method, we validated our method with resolution criteria of reconstructed tomograms. Fig. 4F depicts the FSCe/o curves of three tomograms, reconstructed from the raw stack, the prealigned stack and the aligned stack in this example, respectively. It can be seen that the resolution of tomograms is improved from raw stack to aligned stack, matching our analysis (Figs. 4A-E) and confirming the effectiveness of our proposed method.

3.4 Quantitative assessment of alignment quality of cryo-ET images

We then tested if our method can also reliably work with cryo datasets, which are typically imaged with lower doses and are more noisy than stained sample images. Compared to the narrow spread of the data points around the fitting line for the stained example (Fig. 4), the data points for the cryo datasets (region size 200×200 pixels) are widely scattered although a linear trend is still evident (Fig. 5).

Due to the large spreads, it is difficult to visualize the difference of alignment quality directly from the log-linear plots of raw (Fig. 5A), prealigned (Fig. 5B) and aligned (Fig. 5C) stack. However, the plot of residuals in Fig. 5D indicates that the aligned stack attains the best alignment accuracy with the smallest residuals (red line in Fig. 5D) among these three stacks, even though it is only marginally better than the prealigned stack (green curve in Fig. 5D). The statistical analysis in Fig. 5E suggests that both coarse alignment and fine alignment are able to improve alignment quality of cryo datasets, and marker based fine alignment can achieve the best alignment accuracy in this case, even though it does not enhance the alignment accuracy as much as it does for the stained sample images (Fig. 4E). The FSCe/o curves of prealigned and aligned stacks are indistinguishable in Fig. 5F and fail to reveal the difference between their resolutions, which is likely due to the poor SNR of these images. We then visually examined the tomograms reconstructed from the prealigned stack (Fig. S1A, C, E) and final aligned stack (Fig. S1B, D, F). Based on the clearly worse missing wedge artifacts around the gold beads in the tomogram of prealigned stack (Fig. S1A, C, E) and the more symmetric artifacts in the tomogram of aligned stack (Fig. S1B, D, F), we conclude that the marker based alignment can indeed further improve the alignment quality of the coarse prealignment based on cross correlation although such minor improvements cannot be reliably detected by the FSCe/o resolution tests. However, such minor alignment improvements could still be detected by our method (Fig. 5D, E).

3.5 Alignment inaccuracies

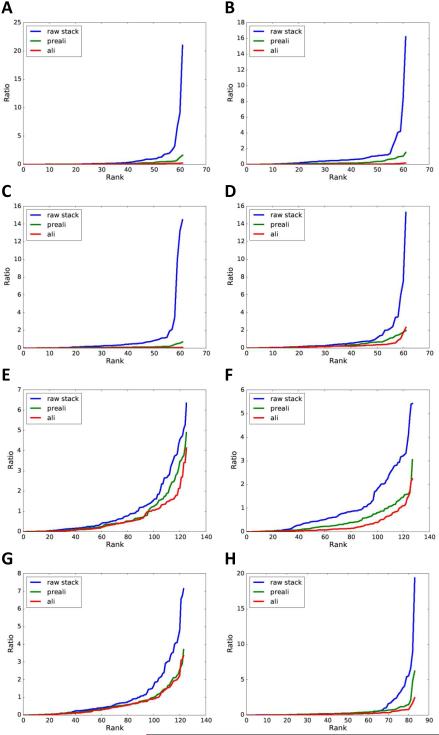

The above tests indicated excellent alignment quality for the stained sample (Fig. 4) but significantly worse quality for the cryo sample (Fig. 5). To investigate if such difference in alignment quality is a general phenomenon, we have further applied our method to additional stained sample datasets (Fig. 6A-D) and cryo sample datasets (Fig. 6E-H).

Fig. 6. Evaluations of alignment qualities of additional datasets.

Shown are sorted residual plots of tilt series of additional stained (A-D) and cryo (E-H) samples. (A-C) Sindbis virus infected BHK cell sections embedded in resin and stained. (D) Flock House virus infected Drosophila S2 cell sections embedded in resin and stained. (E-G) Frozen-hydrated, purified Sindbis virus. (H) Frozen-hydrated Borreliaburgdorferi cells.

It can be seen that residuals of stained datasets were almost all minimized to very small values after pre and fine alignments. There were only occasional sub-optimal alignments for a small number of tilt images (Fig. 6D). In stark contrast, the alignment qualities for cryo datasets appear to be much poorer with large residuals after both pre and fine alignments for most datasets. For cryo datasets, most of the alignment improvements were achieved by correlation based prealignment while the marker based fine alignment could only provide small additional improvements. Compared to the apparently superior alignment quality for stained datasets, current methods appear to be inadequate in providing optimal alignment for cryo datasets.

To better understand the drastically different levels of residuals for stained and cryo datasets, we investigated the effect of several factors, number of regions (Figs. S2, S3), region sizes (Fig. S4), and adaptive change of region sizes at different tilt angles (Fig. S5). To test effects of noise and the efficacies of averaging of more regions in reducing the residuals (Figs. S2, S3), we applied different levels of random noise to the raw stack and then performed prealignment and marker-based alignment for each of the new stacks. For a fixed number of regions, increasing noise will increase, as expected, the residual of both prealigned and aligned stacks. For a fixed noise level, averaging of more regions can effectively reduce the residuals to negligible levels for stained samples (Fig. S2). However, significant levels of residuals remain even when large numbers of regions were used for cryo datasets (Fig. S3). These results suggest that the remaining residuals for aligned stacks of cryo datasets were not caused by the higher level of noises but more likely from systematic errors, for example, alignment inaccuracies, that cannot not be reduced by averaging. To test the effect of different region sizes, we repeated the analysis for constant region sizes ranging from 50×50 to 300×300 pixels (Fig. S4). We found that the levels of residuals for each of the three stacks remain essentially the same for all these tested region sizes. Thus, region size is not a sensitive parameter for our method and an arbitrary size (100×100 or 200×200 pixels) in this tested range should be fine in general. However, a user option was provided for our program to let the user specify a region size. To test if the extra contents from left/right side of the region in tilted image would affect the performance of our method, we also tested variable region sizes by reducing the X-dimension according to the tilt angle (Nx(θ) = Nx(0)cosθ) (Fig. S5). For all region sizes, the adaptive region size strategy (Fig. S5) returned very similar results as those by the simple constant region size strategy (Fig. S4). Thus, our method is robust for a wide range (50×50 to 300×300 pixels) of both constant and adaptive region sizes. However, a user option was provided for our program to let user specify either constant or adaptive region size for the best performance of diverse samples.

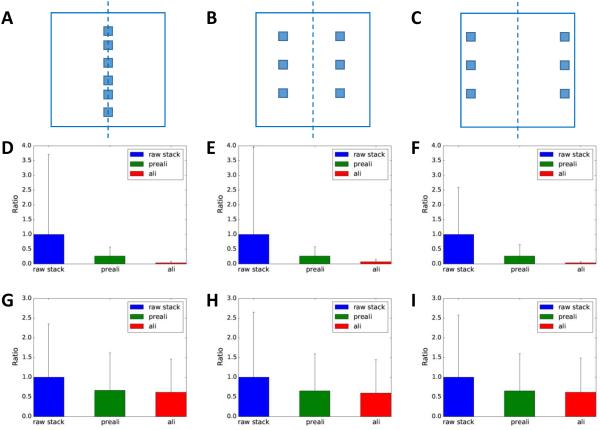

3.6 Effects of defocus

In a tilted image, a defocus gradient exists in the direction perpendicular to the tilt axis. The overall defocus of different tilt images can also be different. These defocus variations can potentially cause the variation of pixel values and affect the performance of our method. To test the effect of defocus variation on the performance of our method, we selected multiple sets of regions with varying distances to the tilt axis. The first row in Fig. 7 (Fig. 7A-C) illustrates three different sets of locations: along the tilt axis, offset from tilt axis at halfway towards and close to the edges which represent minimal, medium and maximal defocus variations, respectively. The alignment qualities for the stained (Fig. 7D-F) and cryo (Fig. 7G-I) samples were evaluated using our method for each of these three sets of locations. It is evident that the defocus variations have no significant effect on the evaluation of alignment quality, since the method is able to correctly distinguish the alignment quality of raw stack, prealigned stack and aligned stack no matter where the regions are located. Hence, the results indicate that our method can perform robustly on the tilt series and the method is insensitive to defocus variations.

Fig. 7. Performances with varying defocuses.

(A-C) The three panels represent three different sets of regions with different amounts of defocus gradient: minimum (A), intermediate (B) and large defocus gradient (C). The dash lines represent the tilt axis. (D-F) The three panels compare the residuals when multiple regions were selected as shown in (A-C) from one stained sample tilt series. (G-I) The three panels compare the residuals when multiple regions were selected as shown in (A-C) from one cryo sample tilt series.

To understand the basis of our method’s insensitivity to defocus variations, we used simulations to probe the effects of contrast transfer function (CTF) with varying defocuses on a simulated image with random noise of Gaussian distribution. We measured the mean and standard deviation of the CTF modulated images and plotted them as function of defocus in Fig. S6. The profiles of mean and standard deviation exhibit very different behaviors: the mean values remain nearly constant, while the standard deviation increases with defocus until reaching a plateau. The constant mean pixel value explains why our method is insensitive to defocus variations. Since both image contrast and image standard deviation measure the pixel value variations, we can use the standard deviation as a measurement of image contrast. The increased image contrast at large defocuses is thus consistent with the weak phase object image formation theory for TEM of thin biological specimens. The plateauing of image contrast also suggests that there is no need for excessively large defocus.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we have introduced a new method, derived from the principle of the Beer-Lambert law (Eq. 1), in order to establish a reliable cross-validation tool for alignment quality of tilt series. The underlying idea is to evaluate the alignment quality in terms of the goodness of linear relationship of data points calculated from tilt series (Eq. 5 and Fig. 2). The tests with both experimental stained and cryo samples (Figs. 2-6) demonstrated that this method allows a robust and accurate assessment of alignment quality of electron tomographic tilt images. This method is fast and takes less than one minute on a typical desktop computer for a tilt series. Compared to the FSCe/o resolution test (Cardone et al., 2005), our new method is not only orders faster but also a direct method specifically for testing alignment instead of measuring the compound effects of image alignment and 3D reconstruction methods. This specificity for alignment might also explain its better sensitivity to alignment improvement than the FSCe/o resolution test (Fig. 5). With these unique features, our new method can serve as an accurate and fast cross-validation of alignment quality and also as a guide for further optimizing the alignment before reconstructing 3D tomogram.

From our tests with both stained and cryo samples and the drastically different alignment qualities discovered for both types of images (Figs. 2-6), we have also gained insights to the key factors for accurate alignments and the limitations of current alignment methods. If we assume that the residuals reported by our method consist of two sources, one from alignment errors and the other from the noise contribution to the pixel values, the minimal residuals for the stained samples suggest that both sources are negligible for these datasets. Further tests with larger number of regions and increased level of noises (Fig. S2) suggest that noise-related residuals can be effectively minimized by averaging of multiple regions used by our method. The high level of residuals for cryo datasets even after averaging a large number of regions thus suggests significant alignment errors for the cryo datasets. We think that inaccurate alignment might still be a major bottleneck for high resolution tomography. A similar conclusion was also independently reported based on other evidences (Bartesaghi et al., 2012; Voortman et al., 2014). We hypothesize that the gold bead positions undergo a non-negligible amount of movement (Chen et al., 2008) during imaging when considering that vitreous ice undergoes melt/freeze cycles of phase changes induced by the electron beam (McMullan et al., 2015) and the highly localized deposition of energy on the electron-dense gold. In contrast, images of stained section samples were taken at room temperature without fluidic phase and the samples were embedded in highly cross-linked resin. The gold beads are thus likely much more stable and allow much more accurate alignment for the stained samples. Based on these analyses, we suggest a new marker-free alignment method without relying on electron dense beads will be needed to provide better alignment accuracy for higher resolution tomograms of cryo samples. As shown in Fig. 3, the residuals from the linear fitting line are highly correlated with the magnitude of alignment errors. A direction to explore will be to use the residuals from the linear fitting line of tilt images not only as an evaluation criterion but also as a scoring function for optimization of the alignment parameters to minimize these residuals.

Our finding of the insensitivity of the mean pixel values to defocus variations (Fig. 7, S6) is both satisfying and initially puzzling. This property removes a major complication related to defocus variations due to either defocus gradient within a single tilt image or change of mean defocus across different tilt images. We will understand it from the physical process of electrons passing through the sample and objective lens. While most electrons pass through the sample without being scattered, some of the electrons will be either elastically or inelastically scattered with ~1:3 ratio in probability (Henderson, 1995). If we consider electrons as waves, the amplitude of the wave will be reduced by inelastic scattering but elastic scattering will only influence the phases. Since the beam intensity is only dependent on the wave amplitude but not the phase, the Beer-Lambert law used here thus primarily utilized the inelastically scattered electrons. On the contrary, image contrast is dominated by the defocus-dependent phase contrast resulted from phase modulations by objective lens, which do not change the wave amplitude and beam intensity. This property can also be explained using the CTF theory in image formation: the Fourier transform of the image is the Fourier transform of the sample multiplied by CTF and then corrupted by noises. In this Fourier formulation, the mean pixel value corresponds to the DC term (i.e. F(0,0), the origin of the Fourier transform). Since varying defocus only changes the CTF oscillations at non-zero frequencies but not the DC term, the mean pixels values should stay constant at different defocuses.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Comparison of reconstruction qualities of prealigned and aligned cryo tilt series shown in Fig. 5. Sections (A, B for XY plane, C, D for XZ plane, and E, F for YZ plane) are shown for tomogram of prealigned (left column, A, C, E) and aligned (right column, B, D, F) stacks. Note that the reconstruction quality of gold beads in the prealigned stack reconstruction, as judged by the asymmetric missing-wedge artifacts around the beads, is worse than that of the beads in tomogram of aligned stack. This small quality improvement from marker-based alignment can be detected by our method (Fig. 5D, E) but not by FSCe/o (Fig. 5F).

Fig. S2. Performance with stained sample dataset at multiple levels of computationally added noise and different numbers of regions used for alignment quality evaluation. The region size is 100×100 pixels. We added different levels of random noise to raw stack and then aligned the noise-added raw stack. Here the random noise is Gaussian noise with zero mean and its standard deviation is 4 (B) or 8 (C) times of the standard deviation of the original image. The bar graphs compare alignment qualities of the original raw stack (A), stack with 4x noise added (B), and stack with 8x noise added (C).

Fig. S3. Performance with cryo dataset at multiple levels of computationally added noise and different numbers of regions used for alignment quality evaluation. The region size is 200×200 pixels. We added different levels of random noise to raw stack and then aligned the noise-added raw stack. Here the random noise is Gaussian noise with zero mean and its standard deviation is 0.25 (B) or 0.5 (C) times of the standard deviation of the original image. The bar graphs compare alignment qualities of the original raw stack (A), stack with 0.25x noise added (B), and stack with 0.5x noise added (C).

Fig. S4. Performance with different constant region sizes. Using the same set of selected region locations in a dataset of stained sample (shown in Fig. 1), we tested different region sizes, 50×50 (A), 100×100 (B), 200×200 (C), and 300×300 (D) pixels.

Fig. S5 Performance with different variable region sizes adaptive to the tilt angles. Using the same set of selected region locations in a dataset of stained sample (shown in Fig. 1), we tested different variable region sizes, 50×50 (A), 100×100 (B), 200×200 (C), and 300×300 (D) pixels. The X-dimension region sizes are varied according to the tilt angle (Nx (θ) = Nx(0)cosθ).

Fig. S6. Defocus-dependence of image mean and standard deviation. CTFs with varying defocuses were applied to a simulated noise image. The CTFs used the following parameters: voltage=300kV, Cs=2mm, amplitude contrast=0.1, B factor=4000Å2, sampling=5Å/pixel, and image size of 256×256 pixels.

Acknowledgements

R.Y. and W.J. designed research, developed scripts, analyzed data and wrote the paper; T.J.E., R.J.K., L.M.P. and J.K.L. provided datasets of stained samples; J.L provided cryo datasets. This work was supported by grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI087946) and Welch Foundation (AU-1714) to J.L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartesaghi A, Lecumberry F, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Protein secondary structure determination by constrained single-particle cryo-electron tomography. Structure. 2012;20:2003–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt SS. Markerless Alignment in Electron Tomography. In: Frank J, editor. Electron Tomography. Springer; New York, New York: 2006. pp. 187–215. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt SS, Ziese U. Automatic TEM image alignment by trifocal geometry. Journal of microscopy. 2006;222:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunfeld MB, Koster AJ, Sedat JW, Agard DA. Cryo automated electron tomography: towards high-resolution reconstructions of plastic-embedded structures. Journal of microscopy. 1994;174:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1994.tb03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardone G, Grunewald K, Steven AC. A resolution criterion for electron tomography based on cross-validation. Journal of structural biology. 2005;151:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JZ, Sachse C, Xu C, Mielke T, Spahn CM, Grigorieff N. A dose-rate effect in single-particle electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2008;161:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H-J, Hyun J-K, Kim J-G, Jeong H, Park H, You D-J, Jung H. Measurement of ice thickness on vitreous ice embedded cryo-EM grids: investigation of optimizing condition for visualizing macromolecules. J Anal Sci Technol. 2013;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Han R, Zhang F, Wan X, Fernandez JJ, Sun F, Liu Z. A marker-free automatic alignment method based on scale-invariant features. Journal of structural biology. 2014;186:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. The potential and limitations of neutrons, electrons and X-rays for atomic resolution microscopy of unstained biological molecules. Quarterly reviews of biophysics. 1995;28:171–193. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SD, Harting M. A new correlation based alignment technique for use in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyeux L, Penczek PA. Efficiency of 2D alignment methods. Ultramicroscopy. 2002;92:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3991(01)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. Journal of structural biology. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malis T, Cheng SC, Egerton RF. EELS Log-Ratio Technique for Specimen-Thickness Measurement in the TEM. J Electron Micr Tech. 1988;8:193–200. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060080206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. Fiducial Marker and Hybrid Alignment Methods for Single- and Double-axis Tomography. In: Frank J, editor. Electron Tomography. Springer; New York, New York: 2006. pp. 163–185. [Google Scholar]

- McMullan G, Vinothkumar KR, Henderson R. Thon rings from amorphous ice and implications of beam-induced Brownian motion in single particle electron cryo-microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2015;158:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan SV, Drummy LF, De Graef M, Simmons JP, Bouman CA. Model Based Iterative Reconstruction for Bright Field Electron Tomography. Proc Spie. 2013;8657 [Google Scholar]

- Voortman LM, Vulovic M, Maletta M, Voigt A, Franken EM, Simonetti A, Peters PJ, van Vliet LJ, Rieger B. Quantifying resolution limiting factors in subtomogram averaged cryo-electron tomography using simulations. Journal of structural biology. 2014;187:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Taylor KA. Accurate marker-free alignment with simultaneous geometry determination and reconstruction of tilt series in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HR, Egerton RF, Malac M. Local thickness measurement through scattering contrast and electron energy-loss spectroscopy. Micron. 2012;43:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Comparison of reconstruction qualities of prealigned and aligned cryo tilt series shown in Fig. 5. Sections (A, B for XY plane, C, D for XZ plane, and E, F for YZ plane) are shown for tomogram of prealigned (left column, A, C, E) and aligned (right column, B, D, F) stacks. Note that the reconstruction quality of gold beads in the prealigned stack reconstruction, as judged by the asymmetric missing-wedge artifacts around the beads, is worse than that of the beads in tomogram of aligned stack. This small quality improvement from marker-based alignment can be detected by our method (Fig. 5D, E) but not by FSCe/o (Fig. 5F).

Fig. S2. Performance with stained sample dataset at multiple levels of computationally added noise and different numbers of regions used for alignment quality evaluation. The region size is 100×100 pixels. We added different levels of random noise to raw stack and then aligned the noise-added raw stack. Here the random noise is Gaussian noise with zero mean and its standard deviation is 4 (B) or 8 (C) times of the standard deviation of the original image. The bar graphs compare alignment qualities of the original raw stack (A), stack with 4x noise added (B), and stack with 8x noise added (C).

Fig. S3. Performance with cryo dataset at multiple levels of computationally added noise and different numbers of regions used for alignment quality evaluation. The region size is 200×200 pixels. We added different levels of random noise to raw stack and then aligned the noise-added raw stack. Here the random noise is Gaussian noise with zero mean and its standard deviation is 0.25 (B) or 0.5 (C) times of the standard deviation of the original image. The bar graphs compare alignment qualities of the original raw stack (A), stack with 0.25x noise added (B), and stack with 0.5x noise added (C).

Fig. S4. Performance with different constant region sizes. Using the same set of selected region locations in a dataset of stained sample (shown in Fig. 1), we tested different region sizes, 50×50 (A), 100×100 (B), 200×200 (C), and 300×300 (D) pixels.

Fig. S5 Performance with different variable region sizes adaptive to the tilt angles. Using the same set of selected region locations in a dataset of stained sample (shown in Fig. 1), we tested different variable region sizes, 50×50 (A), 100×100 (B), 200×200 (C), and 300×300 (D) pixels. The X-dimension region sizes are varied according to the tilt angle (Nx (θ) = Nx(0)cosθ).

Fig. S6. Defocus-dependence of image mean and standard deviation. CTFs with varying defocuses were applied to a simulated noise image. The CTFs used the following parameters: voltage=300kV, Cs=2mm, amplitude contrast=0.1, B factor=4000Å2, sampling=5Å/pixel, and image size of 256×256 pixels.