Abstract

Blood-based biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer (CRC) could complement current approaches to CRC screening. We previously identified the APC-binding protein MAPRE1 as a potential CRC biomarker. Here we undertook a case-control validation study to determine the performance of MAPRE1 in detecting early CRC and colon adenoma and to assess the potential relevance of additional biomarker candidates. We analyzed plasma samples from 60 patients with adenomas, 30 with early CRC, 30 with advanced CRC, and 60 healthy controls. MAPRE1 and a set of 21 proteins with potential biomarker utility were assayed using high-density antibody arrays, and CEA was assayed using ELISA. The biologic significance of the candidate biomarkers was also assessed in CRC mouse models. Plasma MAPRE1 levels were significantly elevated in both patients with adenomas and patients with CRC compared with controls (P < 0.0001). MAPRE1 and CEA together yielded an area under the curve of 0.793 and a sensitivity of 0.400 at 95% specificity for differentiating early CRC from controls. Three other biomarkers (AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1) were significantly increased in both adenoma and early CRC patient plasma samples and in plasma from CRC mouse models at preclinical stages compared with controls. The combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 yielded sensitivities of 0.483 and 0.533 at 90% specificity and sensitivities of 0.350 and 0.467 at 95% specificity for differentiating adenoma and early CRC, respectively, from healthy controls. These findings suggest that MAPRE1 can contribute to the detection of early-stage CRC and adenomas together with other biomarkers.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, early detection, MAPRE1, blood-based biomarker, proteomics

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the United States (1). Most sporadic CRCs develop slowly over many years and often progress from early to advanced adenoma and then to invasive CRC (2). CRC is potentially curable if detected at an early stage; the 5-year survival rates for CRC are approximately 91% for localized disease but only about 13% if distant metastasis has occurred. Therefore, detecting adenoma and early-stage CRC is an attractive approach to reducing CRC mortality rates.

Colonoscopy is considered the gold standard for CRC screening owing to its ability to visualize the complete colon and to remove neoplastic lesions (3), but stool- or blood-based tests for CRC are more convenient, more cost effective, and less invasive than colonoscopy. Several clinical trials have reported that CRC screening with the fecal occult blood test reduced CRC-related mortality by approximately 16% (4). Although fecal occult blood tests have limited ability to detect adenomas, Imperiale et al. have recently reported that a stool DNA test combined with a fecal immunohistochemistry test provided higher sensitivity for detecting CRC and, to a lesser extent, advanced precancerous lesions (5).

Several potential blood-based biomarkers for early detection of CRC or for CRC risk assessment have been described (6-9). Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a circulating biomarker for CRC that is used in the clinical setting for monitoring therapy outcomes in patients with advanced disease and for predicting prognosis (10-12). However, CEA alone lacks the sensitivity and specificity to be used for early detection of CRC (12, 13). Additional biomarkers that complement CEA are needed for reliable and noninvasive detection of early-stage CRC.

We have previously undertaken a discovery study of potential circulating CRC biomarkers using mass spectrometry applied to pre-diagnostic samples from the Women’s Health Initiative cohort, which resulted in the identification of several biomarker candidates (14). Prominent among the candidates was MAPRE1, which is known to bind APC (15, 16), a commonly mutated protein in CRC (17) and which plays a role in microtubule stabilization (18). The association between increased levels of circulating MAPRE1 and CRC was validated in independent plasma sample sets that consisted of newly diagnosed and pre-diagnostic CRC cases.

In the current study, we sought to determine the performance of MAPRE1 together with other candidate biomarkers for detecting disease in blood samples from patients with various stages of CRC or with adenoma collected under the auspices of the National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human plasma samples

All human plasma samples were obtained following Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent. Plasma samples were collected through a consortium led by a Clinical Validation Center of the National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network at the University of Michigan. The samples were collected before any treatment at the time of diagnosis with adenoma (N = 60), early-stage CRC (N = 30; stage I [N = 11] and stage II [N = 19]), or late-stage CRC (N = 30; stage III [N = 21] and stage IV [N = 9]). Plasma samples from healthy controls were collected at the time of colonoscopy (N = 60) (Supplementary Table 1).

Mass spectrometry analysis of human plasma samples

Mass spectrometry analysis of human plasma samples was done as previously described (14, 19).

Mouse models and mass spectrometry analysis of mouse plasma samples

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional and national guidelines and regulations with approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Details on mouse models, plasma sample preparation, and mass spectrometry analysis of those samples are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Human CRC cell lines and mass spectrometry analysis

A mass spectrometry analysis of CRC cell lines was performed as previously described (20). Eight CRC cell lines (HCT116, SW480, LoVo, SW620, HT29, SW48, Colo205, and Caco-2) were purchased from ATCC and grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Pierce) that contained 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 1% penicillin and streptomycin cocktail, and 13C-lysine instead of regular lysine for seven passages, according to the standard SILAC protocol (21). Protein expression was estimated using normalized spectral counts (20).

High-density antibody array

In this study, we have expanded the validation of blood-based biomarkers for CRC and adenoma to include 22 candidates for which antibodies were available for assay using antibody microarrays (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). High-density antibody array analysis was performed as previously described (22, 23). Briefly, albumin and IgG were depleted from plasma samples, 200 μg of the remaining plasma proteins from either cases or controls were labeled with Cy5, and a reference sample (a pool of plasma from seven healthy individuals) was labeled with Cy3. Array images were obtained using a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Molecular Devices), and the scanned array images were analyzed using GenePix Pro 6.0 image analysis software. The raw GenePix Array List file was aligned and resized to fit the individual spot features.

CEA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Plasma levels of CEA were measured with an ELISA kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Histopathology analysis by tissue microarray

Tissue microarrays used in this study comprised 20 normal colonic tissues, 10 colon adenomas, and 66 CRCs (Folio Biosciences). The slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed using a pressure cooker with 0.01 M citrate buffer at pH 6.0. Intrinsic peroxidase activity was blocked using 1% hydrogen peroxide, and 10% normal goat serum (KPL) was used for 30 minutes to block non-specific antibody binding. The slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with MAPRE1 antibody (1:200 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After incubation with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Millipore) for 1 hour at room temperature, antigen signals were detected using the 2-Solution Diaminobenzidine Kit (Cell signaling) and counterstained with hematoxylin. The intensity of staining (0: negative, 1+: weakly positive, 2+: moderately positive, and 3+: strongly positive) and percentage of staining distribution in the tumor cells (from 0 to 100% of the cells) were evaluated for each TMA core. Two independent scoring was performed in a blind manner. Then the scoring was reviewed together again when discordant. In this study samples in which 10% or more of the cells with 1+ staining intensity were considered as positive.

Statistical analyses

For the high-density antibody array analysis, the change in the signal compared with the reference was calculated as log2. Technical sources of variation were normalized using Loess procedures, including within-array print-tip Loess and between-array quantile normalization. Following normalization, triplicate features were summarized using their median values. Individual biomarker performance was assessed using P values calculated by a one-sided Mann–Whitney U test, sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC) determined by a receiver operating characteristic analysis. The P values for significance of the biomarker panel combining MAPRE1 and CEA were subjected to a likelihood ratio test.

To develop an “OR” rule combination model, MAPRE1 and CEA were used as anchor biomarkers to develop a combination rule in which a patient was considered a case if any of the biomarkers exceeded a designated threshold or was ruled out as a case if all biomarkers were below those thresholds (24). The sensitivities at 90% specificity and at 95% specificity of the MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 (“OR” rule combination model) were compared with those of MAPRE1 alone, CEA alone, and MAPRE1 plus CEA (linear combination). The P values for the differences in sensitivity were calculated by the McNemar test (25) and a bootstrap analysis repeated 1000 times. The differences were considered significant when P values were less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Plasma CEA levels were significantly higher in each CRC group than in healthy controls (P = 0.0246 for early CRC, P < 0.0001 for advanced CRC, and P = 0.0002 for total CRC, Mann–Whitney U test), but not significantly different between the adenoma and healthy control groups (P = 0.4886, Mann–Whitney U test) (Table 1). In contrast, the plasma levels of MAPRE1 were significantly elevated in both the adenoma and the CRC groups compared with healthy controls (P < 0.0001 for adenoma, P = 0.0003 for early CRC, P = 0.0025 for advanced CRC, and P < 0.0001 for total CRC, Mann–Whitney U test).

Table 1.

Performance of CEA and MAPRE1 in the University of Michigan sample set.

| Marker (Supplier) |

Parameter | Adenoma (N = 60) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Early CRC (N = 30) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Advanced CRC (N = 30) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Total CRC (N = 60) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Total cases (N = 120) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA (ELISA; R&D Systems) |

P value | 0.4886 | 0.0246 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0422 |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.502 (0.430-0.574) | 0.600 (0.494-0.706) | 0.712 (0.605-0.820) | 0.656 (0.574-0.738) | 0.579 (0.515-0.643) | |

| Sensitivity at 95% specificity |

0.133 | 0.267 | 0.400 | 0.333 | 0.233 | |

|

| ||||||

| MAPRE1 (Strategic Diagnostics Inc.) |

P value | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0025 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.706 (0.612-0.799) | 0.719 (0.608-0.830) | 0.681 (0.568-0.793) | 0.700 (0.606-0.793) | 0.703 (0.622-0.784) | |

| Sensitivity at 95% specificity |

0.250 | 0.267 | 0.100 | 0.183 | 0.217 | |

|

| ||||||

| MAPRE1 + CEA | AUC | 0.731 | 0.793 | 0.759 | 0.777 | 0.753 |

| P value (vs. CEA) |

<0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0014 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| P value (vs. MAPRE1) |

0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Sensitivity at 95% specificity |

0.167 | 0.400 | 0.233 | 0.350 | 0.258 | |

CI: confidence interval

Protein expression of MAPRE1 was examined in colon adenoma and CRC tissues. Among 20 normal colonic tissues, 10 colon adenomas, and 66 CRCs in the tissue microarray, 9 (90.0%) colon adenomas and 45 (66.2%) CRCs were MAPRE1 positive while MAPRE1 expression was observed in only 5 (25.0%) normal colonic tissues (Supplementary Figure 1), suggesting that plasma MAPRE1 would be derived from colorectal tumors.

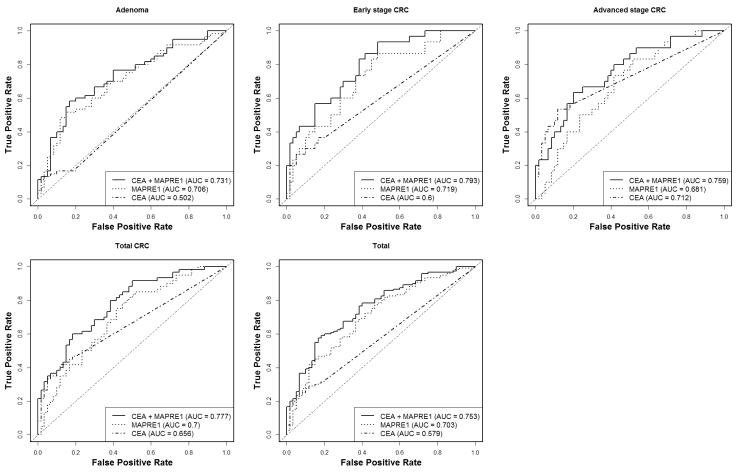

The combination of MAPRE1 and CEA yielded AUCs of 0.793 for early CRC and 0.731 for adenoma (Table 1 and Figure 1). The AUC of the two biomarkers together was significantly better than that of CEA alone (P < 0.0001 for adenoma, early CRC, and total CRC, and P = 0.0014 for advanced CRC, likelihood ratio test) or of MAPRE1 alone (P = 0.0007 for adenoma, P = 0.0004 for early CRC, P = 0.0003 for advanced CRC and P < 0.0001 for total CRC, likelihood ratio test). The combination of MAPRE1 and CEA yielded a sensitivity of 0.400 at 95% specificity in early CRCs compared with healthy controls, whereas the sensitivities of CEA alone and MAPRE1 alone at 95% specificity were noticeably lower for detecting early CRC, indicating an additive effect of the combination of MAPRE1 and CEA for detecting early CRC.

Figure 1. Performance of CEA, MAPRE1, and CEA combined with MAPRE1 in the University of Michigan sample set.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for CEA, MAPRE1, and the combined panel of CEA and MAPRE1 in the comparison of adenoma, early-stage CRC, advanced-stage CRC, total CRC, and total cases with healthy controls.

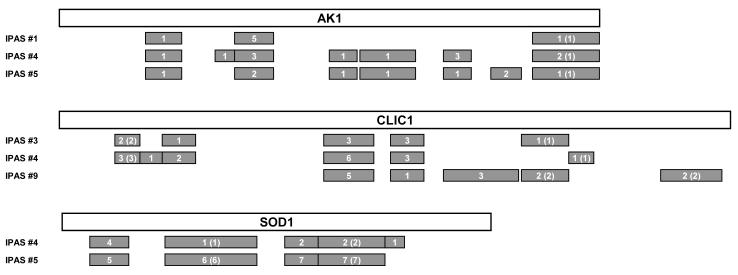

We determined the individual performances of biomarker candidates for which antibodies were printed on the microarrays (Table 2). Three proteins (AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1) were significantly elevated in adenoma and in each CRC group compared with healthy controls (P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test). Five additional proteins (AZGP1, CALR, LGALS3BP, SPARC, and ZYX) exhibited significantly elevated levels in at least one disease group compared with healthy controls. AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1 had been previously identified in a proteomic analysis of pre-diagnostic plasma samples from the Women’s Health Initiative cohort (Supplementary Table 2). Mass spectrometry analysis yielded substantial peptide coverage for AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1 (Figure 2), indicating the occurrence of full-length proteins for these three biomarkers in human plasma. To determine whether these proteins originated from tumor cells, we performed proteomic analysis of three different compartments (media, surface, and whole-cell extract) of eight CRC cell lines. CLIC1 and SOD1 were broadly expressed in the media of CRC cell lines (Supplementary Table 4), while AK1 was identified in the media of three CRC cell lines.

Table 2.

Biomarker candidates significantly elevated in the University of Michigan sample set.

| Marker (Supplier) |

Parameter | Adenoma (N = 60) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Early- CRC (N = 30) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Advanced- CRC (N = 30) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Total CRC (N = 60) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

Total cases (N = 120) vs. healthy controls (N = 60) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK1 (Strategic Diagnostics, Inc.) |

P value | 0.0021 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| AUC | 0.652 | 0.755 | 0.732 | 0.744 | 0.698 | |

| AZGP1 (MyBioSource) |

P value | 0.4572 | 0.2069 | 0.0233 | 0.0424 | 0.1442 |

| AUC | 0.506 | 0.553 | 0.629 | 0.591 | 0.549 | |

| CALR (Aviva Systems Biology) |

P value | 0.1512 | 0.0178 | 0.0734 | 0.0146 | 0.0314 |

| AUC | 0.555 | 0.637 | 0.594 | 0.616 | 0.585 | |

| CLIC1 (Strategic Diagnostics, Inc.) |

P value | 0.0180 | 0.0121 | 0.0036 | 0.0012 | 0.0015 |

| AUC | 0.611 | 0.647 | 0.675 | 0.661 | 0.636 | |

| LGALS3BP (Aviva Systems Biology) |

P value | 0.2353 | 0.0455 | 0.4710 | 0.1613 | 0.1606 |

| AUC | 0.538 | 0.610 | 0.495 | 0.553 | 0.545 | |

| SOD1 (Strategic Diagnostics, Inc.) |

P value | 0.0424 | 0.0279 | 0.0126 | 0.0054 | 0.0067 |

| AUC | 0.591 | 0.624 | 0.646 | 0.635 | 0.613 | |

| SPARC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) |

P value | 0.2500 | 0.0416 | 0.1433 | 0.0428 | 0.0828 |

| AUC | 0.536 | 0.613 | 0.569 | 0.591 | 0.564 | |

| ZYX (Sigma-Aldrich) |

P value | 0.0241 | 0.2647 | 0.0602 | 0.0900 | 0.0274 |

| AUC | 0.605 | 0.541 | 0.601 | 0.571 | 0.588 |

Figure 2. Mass spectrometry identification of biomarker candidates in the pre-diagnostic plasmas in the Women’s Health Initiative cohort.

Schema of three biomarker candidates (AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1) and identification of peptides by mass spectrometry. Gray bars indicate identified peptides. Numbers indicate mass spectra counts for each peptide, and numbers in parentheses indicate mass spectra counts with quantification. The amino acid sequence is based on P00568-1 for AK1, O00299-1 for CLIC1, and P00441-1 for SOD1 in the UniProt Knowledgebase.

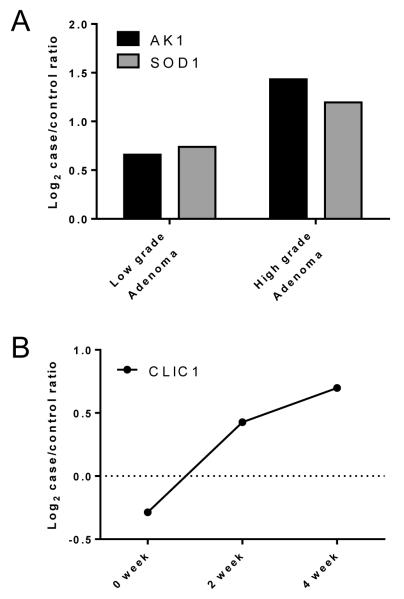

To further investigate the association of increased circulating levels of these biomarker candidates with early CRC development, we used mass spectrometry to profile plasma samples collected at different time points during tumor development from two genetically engineered CRC mouse models. Levels of AK1 and SOD1 were elevated in plasma samples from Apc- and Msh2-deficient mice (26) with low-grade and high-grade adenomas compared with controls (Figure 3). CLIC1 levels were elevated at pre-clinical timepoints (at 2 weeks and 4 weeks after induction of KrasG12D) in a mouse with oncogenic Kras-induced CRC compared with controls (unpublished mouse model) (Figure 3). These findings further support a biologic basis for the association between increased plasma levels of these three biomarker candidates and early development of CRC.

Figure 3. Quantification of biomarker candidates in pre-diagnostic plasmas from mouse models of CRC.

A. Log2-transformed case/control ratios of AK1 and SOD1 levels in plasma from Apc- and Msh2-deficient mice with low-grade adenoma and high-grade adenoma compared with controls. B. Log2-transformed case/control ratios of CLIC1 levels in plasma from a mouse with oncogenic KrasG12D-induced CRC compared with controls. Plasma samples were collected at 0 weeks, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks (the mice were sacrificed at 5 weeks) after induction of KrasG12D from mice in which colon adenocarcinoma developed, and those samples were compared with a pool of plasma samples from five sex-matched mice without tumors.

Since CEA was not significantly elevated in adenoma but was significantly elevated in CRCs at all stages, we investigated whether an “OR” rule (24), rather than a linear combination rule, better discriminates between cases (adenomas or CRCs) and controls. To rule in an asymptomatic person for subsequent work-up (i.e., colonoscopy) who otherwise does not plan to take part in screening, a biomarker test with sensitivity at 90% or with 95% specificity would have potential clinical utility. As reported in Table 1, the combination of MAPRE1 and CEA using logistic regression yielded a sensitivity of 0.400 at 95% specificity in a comparison of early CRC and healthy controls and a sensitivity of only 0.167 at 95% specificity in a comparison of adenoma and healthy controls. Therefore, we assessed the potential of an “OR” rule strategy in which any biomarker in the panel exceeding a certain threshold identifies a patient as a case and in which all biomarkers in the panel not exceeding their designated thresholds would rule out a patient as a case. The “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 yielded significantly higher sensitivity at 95% specificity than the combination of MAPRE1 and CEA in a comparison of adenoma with controls (0.167 sensitivity for MAPRE1 and CEA and 0.350 sensitivity for the “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1; P = 0.015, McNemar test; P = 0.099, bootstrap) and in a comparison of advanced CRC with controls (0.233 sensitivity for MAPRE1 and CEA and 0.500 sensitivity for the “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1; P = 0.013, McNemar test; P = 0.071, bootstrap) (Table 3). For early CRC compared with controls, the sensitivity at 95% specificity of the “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 (0.467) was higher than that of MAPRE1 and CEA (0.400); however, the difference between these sensitivities did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). The sensitivities of the “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 at 90% specificity were 0.483 for adenoma, 0.533 for early CRC, and 0.633 for advanced CRC, and the sensitivities of MAPRE1 and CEA at 90% specificity were 0.400 for adenoma, 0.433 for early CRC, and 0.400 for advanced CRC. These findings suggest an incremental increase in diagnostic performance due to integrating AK1 as a biomarker with MAPRE1 and CEA in screening for adenoma.

Table 3.

Sensitivities at 90% and 95% specificity of biomarkers and their combinations.

| Parameter | Model | Adenoma | Early- CRC |

Advanced CRC |

Total CRC | Total case | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sensitivity at

95% specificity |

MAPRE1+CEA+AK1 (“OR” rule) | 0.350 | 0.467 | 0.500 | 0.433 | 0.375 | |

| P value (McNemar test, Bootstrap) |

vs. MAPRE1+CEA | 0.015, 0.099 | 0.617, 0.308 | 0.013, 0.071 | 0.228, 0.037 | 0.008, 0.042 | |

| vs. MAPRE1 | 0.041, 0.007 | 0.077, 0.005 | 0.003, <0.001 | 0.001, <0.001 | 0.002, <0.001 | ||

| vs. CEA | 0.012, <0.001 | 0.077, 0.005 | 0.450, 0.061 | 0.239, 0.001 | 0.004, <0.001 | ||

| MAPRE1+CEA | 0.167 | 0.400 | 0.233 | 0.350 | 0.258 | ||

| MAPRE1 | 0.250 | 0.267 | 0.100 | 0.183 | 0.217 | ||

| CEA | 0.133 | 0.267 | 0.400 | 0.333 | 0.233 | ||

|

| |||||||

|

Sensitivity at

90% specificity |

MAPRE1+CEA+AK1 (“OR” rule) | 0.483 | 0.533 | 0.633 | 0.567 | 0.500 | |

| P value (McNemar test, Bootstrap) |

vs. MAPRE1+CEA | 0.182, 0.075 | 0.248, 0.067 | 0.023, 0.020 | 0.003, 0.008 | 0.006, 0.009 | |

| vs. MAPRE1 | 0.016, 0.016 | 0.077, 0.006 | 0.002, 0.002 | <0.001, <0.001 | <0.001, <0.001 | ||

| vs. CEA | <0.001, <0.001 | 0.013, 0.001 | 0.074, 0.011 | 0.003, <0.001 | <0.001, <0.001 | ||

| MAPRE1+CEA | 0.400 | 0.433 | 0.400 | 0.383 | 0.392 | ||

| MAPRE1 | 0.333 | 0.367 | 0.200 | 0.283 | 0.308 | ||

| CEA | 0.167 | 0.300 | 0.467 | 0.383 | 0.275 | ||

DISCUSSION

Our study focused on testing the merits of MAPRE1 as a circulating biomarker for CRC and adenomas, both alone and in combination with CEA. We also explored the potential contributions of additional candidate biomarkers. Our prior finding of increased levels of MAPRE1 in pre-diagnostic CRC plasmas (14), which led to the present study, is of particular interest, considering the biologic significance of this protein in the context of CRC (15-17). Concordant with the results of immunohistochemical staining of MAPRE1 in this study, recent studies have demonstrated that MAPRE1 is upregulated in pre-malignant colon mucosa of a rat model of chemically induced CRC and an APC-mutant rat model (27), suggesting that MAPRE1 expression is associated with early field carcinogenesis of CRC. Overexpression of MAPRE1 also has been associated with poor prognosis in CRC (28). In this study, we validated that plasma MAPRE1 levels are significantly associated with CRC and adenoma using an independent sample set from the University of Michigan. MAPRE1 with and without CEA was significantly associated with early CRC and adenoma.

Currently, the repertoire of biomarkers with demonstrated ability to detect adenoma is quite limited. In a recent validation study of a multitarget stool DNA test for CRC screening, the sensitivity for advanced precancerous lesions was 42.4% with DNA testing and 23.8% with a fecal immunochemical test. The rate of detection of polyps with high-grade dysplasia was 69.2% with DNA testing and 46.2% with the fecal immunochemical test (5). Plasma methylated SEPT9 has been shown to be a biomarker for CRC in a screening setting, with a sensitivity of 48.2% and a specificity of 91.5%, but its sensitivity for advanced adenoma was only 11.2% (6). For MAPRE1 and CEA, the sensitivity at 90% specificity was 40% for adenoma and 43% for early CRC (Table 3), suggesting that MAPRE1 combined with CEA may improve current blood-based screening for both adenoma and CRC. Further studies will be warranted to validate the performance of MAPRE1 together with CEA, particularly in high-risk adenoma (villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, size larger than 1 cm, or 3 or more adenomas).

We also determined the individual performances of additional biomarker candidates. Eight candidates were significantly associated with disease in one or more groups, of which three candidates (AK1, CLIC1, and SOD1) were each significantly associated with adenoma, early-stage CRC, advanced-stage CRC, and total CRC. These three candidates were previously identified in a proteomic analysis of pre-diagnostic plasma samples from the Women’s Health Initiative cohort (Supplementary Table 2).

Evidence also suggests that a systemic increase in circulating AK1 may occur very early in the development of colorectal neoplasia. We found that plasma levels of AK1 were significantly higher in mice with low-grade as well as those with high-grade adenoma compared with controls and that AK1 was elevated in plasma samples from human adenoma and CRC cases compared with controls. Recent studies have indicated a role of AK1 in the bloodstream in regulating metabolism of extracellular AMP, ADP, and ATP (29), which are associated with immunosuppression and tumor progression (30). Expression of AK1 increases in response to obesity and metabolic syndrome, which are known risk factors of CRC (31-33).

We also found increases in plasma levels of CLIC1 in preclinical CRC and SOD1 in adenomas compared with controls in mouse experiments, and those biomarkers were also elevated in plasma samples from human adenoma and CRC cases compared with controls. CLIC1 is a previously characterized plasma biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma and has been found to promote cell migration and invasion in CRC (34-37). SOD1 protein expression in CRC tumors and precancerous colon tissues from chemically induced CRC mouse or rat models has been investigated, with variable results (34, 38-41).

Although the “OR” rule combination of MAPRE1, CEA, and AK1 yielded the highest sensitivity in this study compared with the Lasso logistic regression model and two other machine learning methods (optimal linear combination by maximizing the partial area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and combination of biomarkers using fractional polynomials) (data not shown), the merits of the “OR” rule will need to be assessed through further testing in additional, larger sample sets. The bootstrap test used the decision rule applied to subjects not included in the bootstrap sample; thus, the test does not have the bias associated with estimating performance using the same sample set used for training.

Our previous discovery studies and our validation studies presented here stem from an in-depth quantitative proteome analysis of plasma that addresses the intended application of blood-based screening for adenoma and early CRC in combination with other screening modalities. Plasma contains a rich assortment of circulating molecules and cellular materials that can inform us about tumor development, including tumor-derived DNA (6, 42), non-coding RNAs (43, 44), autoantibodies (45, 46), and metabolites (47). There remains a pressing need to determine the relevance and relative contributions of the various potential biomarkers in detecting adenoma and early CRC. Our validation of MAPRE1 as a circulating biomarker for adenoma and CRC provides a rationale for further studies into the development of a blood-based biomarker approach using MAPRE1 that complements current screening modalities for CRC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: This work was supported by U01 CA152746 (P.D. Lampe and S.M. Hanash) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64:104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490–502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valori R, Rey JF, Atkin WS, Bretthauer M, Senore C, Hoff G, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Quality assurance in endoscopy in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Endoscopy. 2012;44(Suppl 3):SE88–105. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuipers EJ, Rosch T, Bretthauer M. Colorectal cancer screening--optimizing current strategies and new directions. Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2013;10:130–42. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Levin TR, Lavin P, Lidgard GP, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:1287–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Church TR, Wandell M, Lofton-Day C, Mongin SJ, Burger M, Payne SR, et al. Prospective evaluation of methylated SEPT9 in plasma for detection of asymptomatic colorectal cancer. Gut. 2014;63:317–25. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyro C, Olsen A, Landberg R, Skeie G, Loft S, Aman P, et al. Plasma alkylresorcinols, biomarkers of whole-grain wheat and rye intake, and incidence of colorectal cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106:djt352. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Duijnhoven FJ, Bueno-De-Mesquita HB, Calligaro M, Jenab M, Pischon T, Jansen EH, et al. Blood lipid and lipoprotein concentrations and colorectal cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Gut. 2011;60:1094–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.225011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fijneman RJ, de Wit M, Pourghiasian M, Piersma SR, Pham TV, Warmoes MO, et al. Proximal fluid proteome profiling of mouse colon tumors reveals biomarkers for early diagnosis of human colorectal cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:2613–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan E, Gouvas N, Nicholls RJ, Ziprin P, Xynos E, Tekkis PP. Diagnostic precision of carcinoembryonic antigen in the detection of recurrence of colorectal cancer. Surgical oncology. 2009;18:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy MJ, van Dalen A, Haglund C, Hansson L, Holinski-Feder E, Klapdor R, et al. Tumour markers in colorectal cancer: European Group on Tumour Markers (EGTM) guidelines for clinical use. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1348–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nature reviews Cancer. 2005;5:845–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy MJ. Carcinoembryonic antigen as a marker for colorectal cancer: is it clinically useful? Clinical chemistry. 2001;47:624–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladd JJ, Busald T, Johnson MM, Zhang Q, Pitteri SJ, Wang H, et al. Increased plasma levels of the APC-interacting protein MAPRE1, LRG1, and IGFBP2 preceding a diagnosis of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:655–64. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green RA, Wollman R, Kaplan KB. APC and EB1 function together in mitosis to regulate spindle dynamics and chromosome alignment. Molecular biology of the cell. 2005;16:4609–22. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su LK, Burrell M, Hill DE, Gyuris J, Brent R, Wiltshire R, et al. APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer research. 1995;55:2972–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, Cabrera-Poch N, Morris EJ, Chen M, et al. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nature cell biology. 2004;6:820–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faca V, Coram M, Phanstiel D, Glukhova V, Zhang Q, Fitzgibbon M, et al. Quantitative analysis of acrylamide labeled serum proteins by LC-MS/MS. Journal of proteome research. 2006;5:2009–18. doi: 10.1021/pr060102+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taguchi A, Politi K, Pitteri SJ, Lockwood WW, Faca VM, Kelly-Spratt K, et al. Lung cancer signatures in plasma based on proteome profiling of mouse tumor models. Cancer cell. 2011;20:289–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong SE, Mann M. A practical recipe for stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2650–60. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loch CM, Ramirez AB, Liu Y, Sather CL, Delrow JJ, Scholler N, et al. Use of high density antibody arrays to validate and discover cancer serum biomarkers. Molecular oncology. 2007;1:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez AB, Loch CM, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang X, Wayner EA, et al. Use of a single-chain antibody library for ovarian cancer biomarker discovery. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2010;9:1449–60. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900496-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etzioni R, Kooperberg C, Pepe M, Smith R, Gann PH. Combining biomarkers to detect disease with application to prostate cancer. Biostatistics. 2003;4:523–38. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mc NQ. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucherlapati MH, Esfahani S, Habibollahi P, Wang J, Still ER, Bronson RT, et al. Genotype directed therapy in murine mismatch repair deficient tumors. PloS one. 2013;8:e68817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stypula-Cyrus Y, Mutyal NN, Dela Cruz M, Kunte DP, Radosevich AJ, Wali R, et al. End-binding protein 1 (EB1) up-regulation is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis. FEBS letters. 2014;588:829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugihara Y, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Tsuda H, Kubota D, Ichikawa H, et al. Proteomic-based identification of the APC-binding protein EB1 as a candidate of novel tissue biomarker and therapeutic target for colorectal cancer. Journal of proteomics. 2012;75:5342–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yegutkin GG, Wieringa B, Robson SC, Jalkanen S. Metabolism of circulating ADP in the bloodstream is mediated via integrated actions of soluble adenylate kinase-1 and NTPDase1/CD39 activities. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012;26:3875–83. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-205658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stagg J, Smyth MJ. Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and adenosine in cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:5346–58. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzeja P, Terzic A. Adenylate kinase and AMP signaling networks: metabolic monitoring, signal communication and body energy sensing. International journal of molecular sciences. 2009;10:1729–72. doi: 10.3390/ijms10041729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hittel DS, Hathout Y, Hoffman EP, Houmard JA. Proteome analysis of skeletal muscle from obese and morbidly obese women. Diabetes. 2005;54:1283–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giovannucci E. Metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, and colon cancer: a review. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2007;86:s836–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.836S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang B, Wang J, Wang X, Zhu J, Liu Q, Shi Z, et al. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2014;513:382–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrova DT, Asif AR, Armstrong VW, Dimova I, Toshev S, Yaramov N, et al. Expression of chloride intracellular channel protein 1 (CLIC1) and tumor protein D52 (TPD52) as potential biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Clinical biochemistry. 2008;41:1224–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang P, Zeng Y, Liu T, Zhang C, Yu PW, Hao YX, et al. Chloride intracellular channel 1 regulates colon cancer cell migration and invasion through ROS/ERK pathway. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2014;20:2071–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i8.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang YH, Wu CC, Chang KP, Yu JS, Chang YC, Liao PC. Cell secretome analysis using hollow fiber culture system leads to the discovery of CLIC1 protein as a novel plasma marker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Journal of proteome research. 2009;8:5465–74. doi: 10.1021/pr900454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skrzycki M, Majewska M, Podsiad M, Czeczot H. Expression and activity of superoxide dismutase isoenzymes in colorectal cancer. Acta biochimica Polonica. 2009;56:663–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amaral EG, Fagundes DJ, Marks G, Inouye CM. Study of superoxide dismutase's expression in the colon produced by azoxymethane and inositol hexaphosfate's paper, in mice. Acta cirurgica brasileira / Sociedade Brasileira para Desenvolvimento Pesquisa em Cirurgia. 2006;21(Suppl 4):27–31. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502006001000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christudoss P, Selvakumar R, Pulimood AB, Fleming JJ, Mathew G. Tissue zinc levels in precancerous tissue in the gastrointestinal tract of azoxymethane (AOM)-treated rats. Experimental and toxicologic pathology : official journal of the Gesellschaft fur Toxikologische Pathologie. 2008;59:313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korenaga D, Takesue F, Kido K, Yasuda M, Inutsuka S, Honda M, et al. Impaired antioxidant defense system of colonic tissue and cancer development in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. The Journal of surgical research. 2002;102:144–9. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:224ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, Lam EK, Shin VY, Yu J, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58:1375–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofsli E, Sjursen W, Prestvik WS, Johansen J, Rye M, Trano G, et al. Identification of serum microRNA profiles in colon cancer. British journal of cancer. 2013;108:1712–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barderas R, Villar-Vazquez R, Fernandez-Acenero MJ, Babel I, Pelaez-Garcia A, Torres S, et al. Sporadic colon cancer murine models demonstrate the value of autoantibody detection for preclinical cancer diagnosis. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2938. doi: 10.1038/srep02938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang W, Wu L, Cao F, Liu Y, Ma L, Wang M, et al. Development of autoantibody signatures as biomarkers for early detection of colorectal carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:5715–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leufkens AM, van Duijnhoven FJ, Woudt SH, Siersema PD, Jenab M, Jansen EH, et al. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and risk of developing colorectal cancer: a cohort-nested case-control study in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;175:653–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.