Abstract

Intestinal ischemia, which refers to insufficient blood flow to the bowel, is a potentially catastrophic entity that may require emergent intervention or surgery in the acute setting. Although the clinical signs and symptoms of intestinal ischemia are nonspecific, CT findings can be highly suggestive in the correct clinical setting. In this chapter we review the CT diagnosis of arterial, venous, and non-occlusive intestinal ischemia. We discuss the vascular anatomy, pathophysiology of intestinal ischemia, CT techniques for optimal imaging, key and ancillary radiological findings, and differential diagnosis.

In the setting of an acute abdomen, rapid evaluation is necessary to identify intraabdominal processes that require emergent surgical intervention (1). While a wide-range of intraabdominal diseases may be present from trauma to inflammation, one of the most feared disorders is mesenteric ischemia, also known as intestinal ischemia, which refers to insufficient blood flow to the bowel (2). Initial imaging evaluation for intestinal ischemia is typically obtained with CT. Close attention to technique and search for key radiologic features with relation to the CT technique is required. Accurate diagnosis depends on understanding the vascular anatomy, epidemiology, and pathophysiology of various forms of mesenteric ischemia and their corresponding radiological findings on MDCT. At imaging, not only is inspection of the bowel itself important, but evaluation of the mesenteric fat, vasculature, and surrounding peritoneal cavity also helps improves accuracy in the diagnosis of bowel ischemia.

Keywords: Computed Tomography; bowel ischemia; intestinal ischemia; contrastoral contrast, bowel infarction; mesenteric ischemia; pneumatosis intestinalis; mesenteric artery occlusion

Pathophysiology and presentation

Intestinal ischemia has diverse etiologies and presentations. Mesenteric ischemia is classified into two forms, acute and chronic, which are differentiated on the timing of symptom onset and extent of decreased blood flow. Mesenteric ischemia is further subdivided by etiology: arterial, venous, and non-occlusive. In a general sense, intestinal ischemia frequently presents with nonspecific clinical symptoms. The classic triad of abdominal pain, hematochezia, and fever is seen in only 1 out of 3 patients (3). More commonly, non-specific symptoms are seen and include diarrhea, vomiting, and bloating.

Acute mesenteric ischemia

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) occurs from arterial embolic or thrombotic obstruction, mesenteric venous thrombosis, or a non-occlusive etiology (4). The mean age of patients with acute mesenteric arterial occlusive ischemia (embolic and thrombosis) is 70 years of age. However, patients younger than 50 years of age may also form occlusive emboli in the setting of atrial fibrillation (5). Arterial emboli from a cardiac (6) or septic source are the most common cause of acute mesenteric ischemia and comprise 40-50% of the cases. Patients often present with abrupt onset of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting (7).

Thrombotic arterial ischemia may be acute or chronic and occurs in patients with preexisting atherosclerotic lesion in a mesenteric artery with superimposed thrombosis formation. The major risk factors in these patients include atherosclerotic disease, aortic dissection and aneurysm, arteritis, and dehydration. These patients undergo gradual progression of arterial occlusion. Therefore, many present with abdominal angina – a syndrome of postprandial pain lasting up to 3 hours. This results in “food fear”, early satiety, and weight loss. In the acute setting however, the clinical symptoms are similar to those found in patients with the arterial embolic disease (5).

Chronic arterial bowel ischemia presents with subacute and even less specific symptoms. Chronic bowel ischemia may or may not present with abdominal pain, but rather weight loss and food-fear (3). While chronic mesenteric ischemia remains rare, occurring in 1 out of 1000 hospital admissions, it has a high mortality with death rate ranging from 30% to 90% (7). Chronic bowel ischemia generally presents in patients older than 60 years of age and is 3 times more common in women (8).

This syndrome occurs in the setting of long-standing mesenteric arterial atherosclerotic disease resulting in constant decreased blood flow, especially in the post-prandial state. Patients may present with significant weight loss secondary to post-prandial pain lasting up to 90 minutes. These patients often report prior such episodes of intestinal angina clueing the clinician to the diagnosis. However, 15-20% of these patients demonstrate no symptoms. Over time, as the vascular obstructive process progresses, chronic, dull abdominal pain ensues (9).

In contrast, mesenteric venous ischemic, although a less common cause of AMI, has a more variable patient population presentation and occurs in younger patients, often less than 50 years old (3). It can commonly occur due to segmental bowel strangulation or thrombosis. Pertinent medical history is also critical for diagnosis as other risk factors for venous thrombosis include hypercoagulable predispositions such as pregnancy, protein C and S or antithrombin deficiencies, polycythemia vera, malignancy, infection, portal hypertension or venous trauma (10). Patients may present with acute or subacute abdominal pain. They may suffer from symptoms of acute mesenteric ischemia over a prolonged period with gradual progression (25).

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), occurring in 10-20% of AMI cases, is most common in elderly patients with severe systemic illnesses that reduce cardiac output. It most commonly occurs in the post-operative, ICU setting. The clinical diagnosis can be challenging due to the diminished mental state of these patients. These patients may have non-specific symptoms that can range from abdominal pain and nausea to ileus. Other predisposing factors include trauma, cocaine use, ergot ingestion, digoxin, alpha-adrenergic medications, cardiac failure, myocardial infarction, abdominal surgery, and aortic insufficiency (11-13).

Ischemic bowel may result of as complication of other underlying intraabdominal comorbidities. For example, the identification of bowel obstruction on CT should always prompt the search for the complication of bowel ischemia since rapid triage to surgery may be necessary to prevent abdominal catastrophe from bowel perforation (14). Other underlying processes, such as embolic disease or vascular dissection, are important to identify so that long term treatment can be directed toward future prevention of complications (15). Table 1 summarizes the major clinical and CT findings within each of major form of bowel ischemia.

Table I. Major Clinical and CT Findings of Bowel Ischemia.

| Features | Arterial Ischemia |

Venous Ischemia |

Non-occlusive Ischemia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 60-70% | 5-10% | 20-30% |

| Acuity | Acute or chronic | Acute or chronic | Acute or chronic |

|

Clinical Risk

Factors |

Cardiovascular disease: Atrial fibrillation, post- Myocardial infarction, aortic injury, atherosclerosis. septic emboli. systemic vasculitis. |

Bowel strangulation, hypercoagulable state, portal hypertension, venous trauma, infection |

Hypotension, heart failure, recent surgery or trauma, medications including recreational |

| Vasculature | Arterial filling defect, severe arterial narrowing, dissection, aneurysm |

Venous filling defect, often with enlarged venous diameter |

Non-specific |

|

Bowel Wall

Thickness |

May be thin acutely, but may be thickened and involved with hematoma, edema, or inflammation |

Thickened and edematous |

Generally thickened |

|

Bowel Wall

Enhancement |

Variable; diminished or non- enhancement in regions of pale ischemia; hyperenhancement in areas of reperfusion |

Diminished enhancement of mucosa and serosa, target appearance |

Diminished enhancement |

| Mesentery/Fat | Mesenteric fat stranding with free fluid associated with the territory of ischemia |

Mesenteric fat stranding with free fluid associated with the territory of ischemia |

Mesenteric fat stranding with free fluid associated with the territory of ischemia |

Laboratory tests and additional considerations

In patients with abdominal pain, physicians are faced with a broad differential diagnosis that includes pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, diverticulitis, and appendicitis. Physical exam findings and laboratory values can be suggestive of a bowel etiology, but are generally non-specific (14). An elevated lactic acid levels, leukocytosis, and the presence of an anion-gap may or may not be present. Elevated serum lactate levels indicate anaerobic metabolism in the setting of ischemic bowel, but is also associated with other pathologies.

Given the frequent ambiguous clinical presentation of intestinal ischemia, only 1/3 of patients are diagnosed accurately preoperatively (16). CT imaging has been shown to outperform all other laboratory and physical exam findings for the detection of bowel ischemia (14). Catheter-angiography, providing both diagnosis and treatment, has improved mortality over the last 40 years, but is an invasive test (7).

Multidetector CT (MDCT) provides reliable imaging of bowel in the acute setting. Particular benefits of MDCT over MR and US include the rapid speed of image acquisition, which minimizes bowel motion artifact, large field of view and territory of coverage, ability to image through gas and many metals with minimal artifact, and excellent patient tolerance. Potential risks of CT are low, but include risks associated with ionizing radiation dose and nephrotoxicity or reactions to iodinated intravenous contrast material. Conventional angiography is a second line imaging modality that can be extended to relieve areas of obstruction in the mesenteric arteries.

CT oral contrast: positive or neutral?

Generally, approximately 800 to 1200 mL of oral fluid is given to distend the bowel prior to CT scanning. A fundamental decision for CT scanning in patients with suspicion of bowel ischemia is whether or not to administer positive versus neutral oral contrast material. Unfortunately, each choice provides certain benefits and drawbacks. In the emergency setting, urgency may prevent oral contrast administration and CT may be obtained with intravenous contrast material alone. In these cases, the bowel may be poorly distended at imaging and maybe more difficult to evaluate.

Contrast agents that provide CT numbers greater than 50 HU are considered to be “positive” agents, and those with CT numbers near water (−20 to +20 HU) are generally considered to be “neutral” agents. All positive oral contrast agents utilize tri-iodinated compounds or barium sulfate to block X-rays and are effectively mark the lumen of bowel. Positive oral contrast agents improve the ability of CT to distinguish abscess, hematoma, and non-bowel masses from opacified segments of bowel, and help confirm the presence of a bowel leak or fistula. In the setting of bowel obstruction, diminishing oral contrast intensity is generally seen in close proximity to the bowel transition point than in more upstream segments of bowel. Positive oral contrast material may also be valuable to detect bowel wall thickening when intravenous contrast material cannot be given.

A limitation with the use of positive oral contrast are that bright intraluminal contrast material may interfere with the evaluation of hypo- or hyperenhancement of the bowel wall, which may be seen with various forms of bowel ischemia. Also, positive oral contrast may interfere with three-dimensional reformations of the vasculature by maximum intensity projection and volume rendered reformations.

Neutral oral contrast material such as water or sorbitol solutions with 0.1% barium sulfate, are non-FDA approved agents that can distend the bowel with fluid that has CT numbers between −20 and +20 HU. Neutral oral contrast agents, used in conjunction with intravenous contrast agents, allow visualization of bowel wall hypo- or hyperenhancement, and may allow visualization of intraluminal active extravasation of intravenous contrast material.

Three-dimensional reformations of the vasculature is generally possible when neutral contrast agents are used. The major drawback of neutral oral contrast is its resemblance to other bodily fluids: abscesses, free fluid, and to a lesser extent, hematomas. Fistula and leakage of enteric contents may be less vivid or more difficult to identify with neutral than with positive oral contrast agents. Negative oral contrast agents, such as gases and oils, are rarely used for the evaluation of mesenteric ischemia.

CT scan parameters

The CT scan acquisition techniques should be tailored to the clinical need. A noncontrast phase is not essential, but helps to assess for intramural hemorrhage and serves as a baseline for subsequent intravenous contrast-enhanced images. In our institution, a 150 mL bolus of 350 mg iodine/mL intravenous contrast material is injected at 3 mL/sec via a power injector. If an arterial phase is deemed necessary, the injection rate is increased to 5 mL/sec and a bolus threshold trigger is used. A region of interest (ROI) is drawn over the proximal aorta and scanning of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained once a 150 HU threshold is reached. For all scans, a portal venous phase is acquired at 90 seconds delay and reformatted into 2.5 mm axial, 2.5 mm sagittal, and 3 mm coronal images. When available, dual energy CT imaging is utilized with the 90 second delay to assist with the detection of bowel enhancement abnormalities (17).

Anatomy

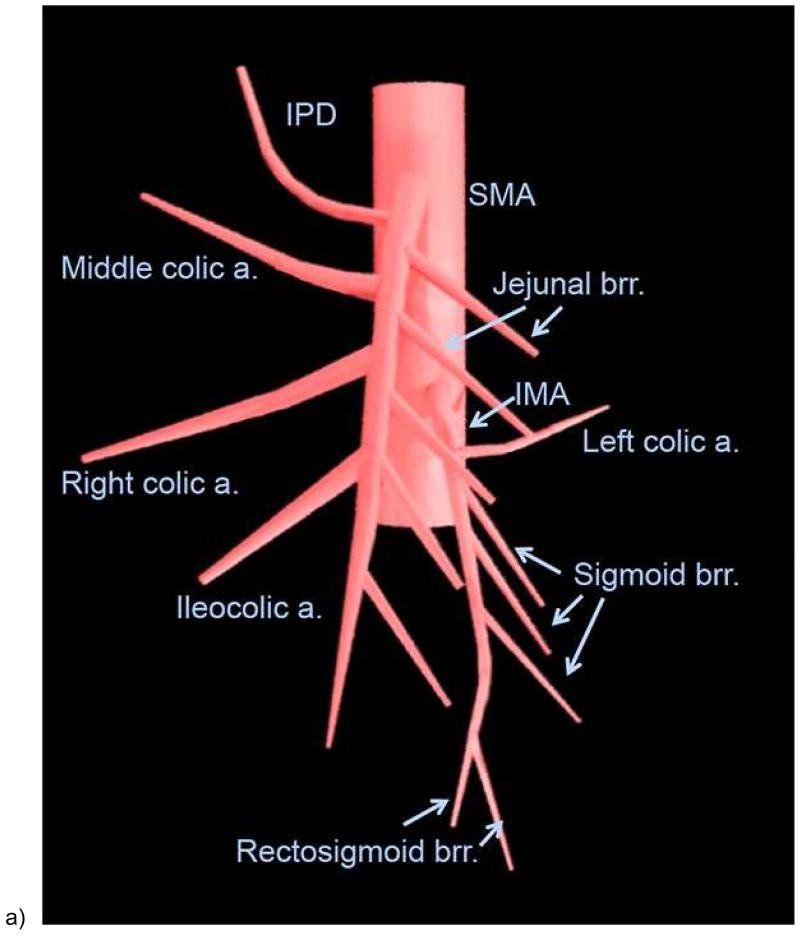

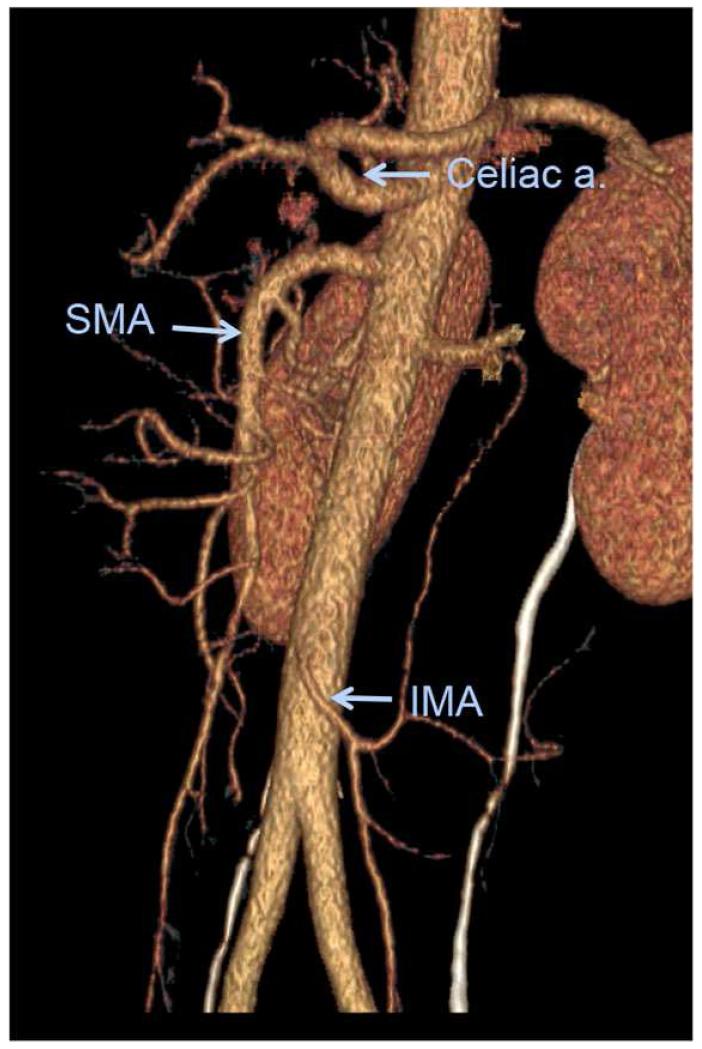

To accurately diagnose mesenteric ischemic disease, interpreting physicians must be acquainted with both mesenteric arterial and venous anatomy of the bowel. There are 3 major arteries that supply the small and large bowel [Figures 1 & 2]. The celiac trunk generally supplies the distal esophagus to the second portion of the duodenum. The superior mesenteric artery (SMA), located at the level of first lumbar vertebral body, supplies the third and fourth portions of the duodenum via the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries, and supplies the jejunum, ileum, and the colon to level of the splenic flexure. The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), located at the level of the third lumbar vertebral body, supplies the distal colon from the level of distal transverse portion to the upper rectum. Branches of the internal iliac arteries, middle and inferior rectal arteries, supply the distal rectum.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the mesenteric arteries (a) and bowel segments supplied by mesenteric arteries (b). SMA = superior mesenteric artery. IPD = inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. a.= artery; brr. = branch artery; IMA = inferior mesenteric artery. The duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon proximal to the splenic flexure is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (bowel with orange color), and the descending and sigmoid colon and upper rectum are supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery (bowel in yellow color). The distal most rectum is supplied by the middle and inferior rectal arteries from the internal iliac artery (bowel in purple color)

Figure 2.

Volume rendered oblique sagittal reformation of normal CT angiogram shows the major mesenteric arteries.

There are numerous important mesenteric collateral pathways that provide a rich vascular safety net for mesenteric blood supply. The gastrodudoenal artery is the first branch of the common hepatic artery and provides a collateral pathway between the celiac artery and the SMA. The marginal artery of Drummond and arcade of Riolan connect the SMA and IMA. Four arcades of anastomosis are formed between the IMA and lumbar arteries arising from the aorta, sacral, and internal iliac arteries. In addition, the peripheral small mesenteric vessels are anatomically arranged in a parallel series configuration that supply the mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis propria of bowel (18).

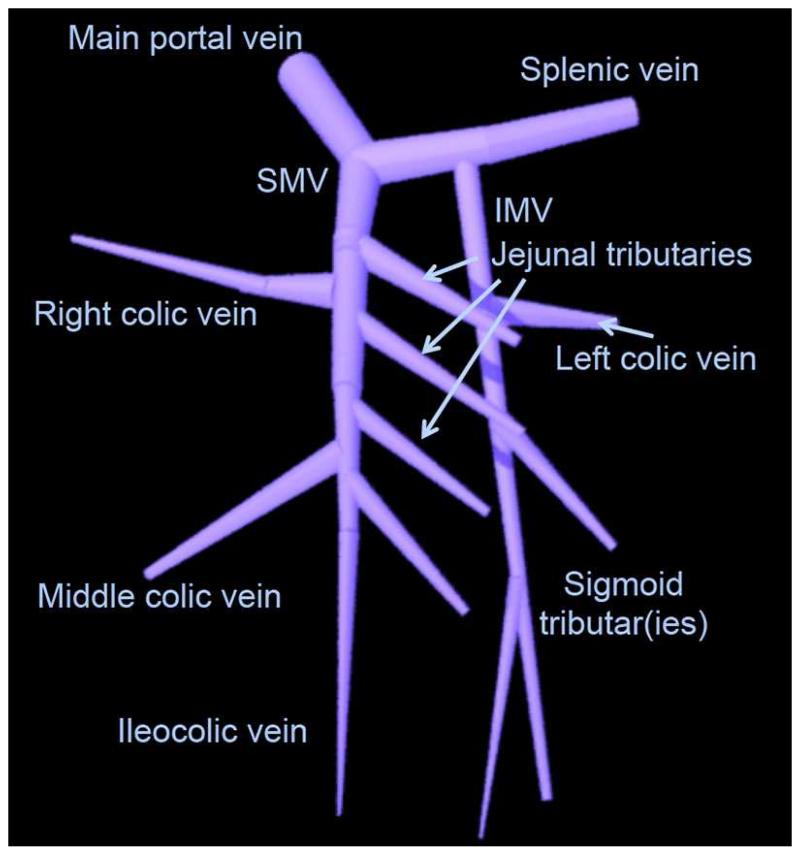

The superior and inferior mesenteric veins run parallel to the arteries and drain the respective part of the bowel [Figure 3]. The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) joins the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) after emptying into the splenic vein to form the main portal vein. Numerous collateral venous pathways exist or can form between mesenteric and systemic veins including, gastric and esophageal, renal, lumbar and pelvic veins. They tend to be more robust than those seen with the mesenteric arteries.

Figure 3.

Illustration of normal major mesenteric veins. SMV = superior mesenteric vein. IMV = inferior mesenteric vein.

Stages of ischemia

While understanding the anatomy allows localization of the disease process, familiarity with pathology helps the radiologist provide a better evaluation of abnormal gut. Acute bowel ischemia is characterized by three stages, specifically based on the extent of bowel wall involvement. Stage I (reversible disease) is pathologically characterized by necrosis, erosions, ulcerations, edema and hemorrhage localized to the mucosa (19, 20). Stage II represents necrosis extending into the submucosal and muscularis propria layers. Finally, the high mortality Stage III disease involves all three layers (transmural necrosis) (21-23). In addition, superinfection of post-mucosal breakdown in the colon may facilitate further necrosis and perforation.

Arterial Ischemia – blood vessel evaluation

The most common cause of acute ischemic colitis and associated necrosis is arterial embolic disease, which comprises for 60-70% of cases (22, 24, 25). The primary systemic risk factors include atrial fibrillation (6, 15), post-myocardial infarction cardiac wall motion abnormalities, emboli from aortic injury or atherosclerosis, and rarely cholesterol and post-aortic surgery embolism. Emboli preferentially affect SMA because of it’s small takeoff angle compared to those of the celiac and IMA. While thrombi and large emboli may occlude the proximal SMA and ostia of major mesenteric vessels resulting in extensive small bowel and colon ischemia, smaller emboli may lodge in the distal portions of the vessel and cause smaller regions of segmental ischemia (22, 24, 25).

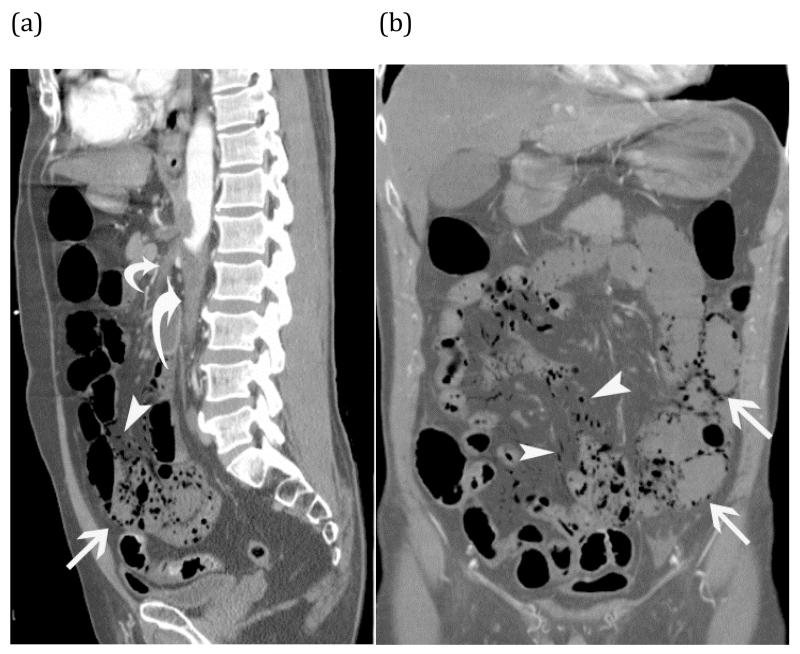

Acute arterial thrombi and emboli may appear as obvious low-attenuation filling defects in the SMA, its branches, or other major mesenteric arteries (26) [Figures 4 & 5]. The presence of emboli involving other visceral organs may help the radiologist suggest this diagnosis.

Figure 4.

Normal small bowel on CT - Coronal image of normal small bowel. Notice the relative increased enhancement of the jejunum in the left upper quadrant compared to the ileum in the right lower quadrant. The apparent jejunal hyperenhancement is due to the higher fold density of the valvulae conniventes in collapsed jejunum than ileum.

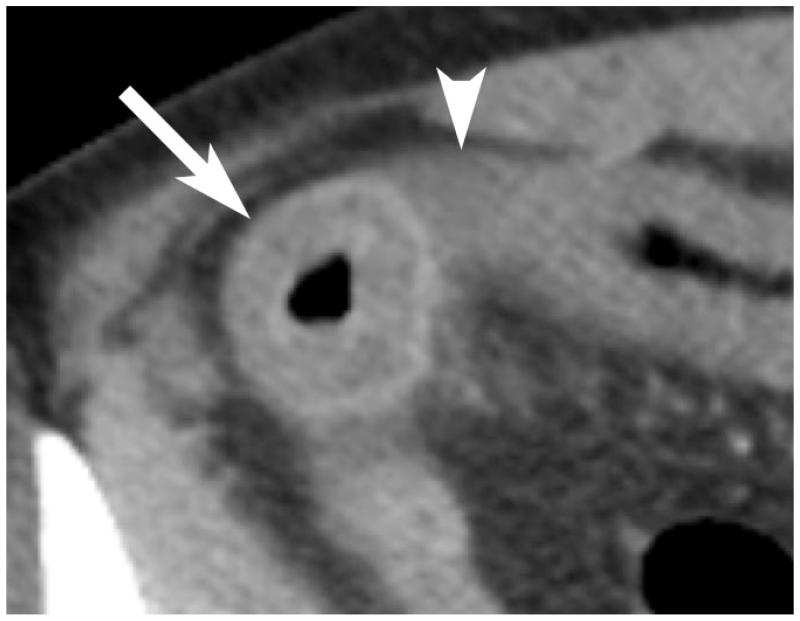

Figure 5.

Arterial ischemia from SMA thrombosis – Elderly man presented with three days of abdominal pain and anorexia. Sagittal (a) and coronal (b) CT images show pneumatosis intestinalis (white arrows) and mesenteric venous gas (white arrowheads) associated with extensive clot in the aorta (large curved arrow) extending into the celiac trunk and SMA (small curved arrow).

Systemic vasculitides causing vascular occlusions uncommonly affect mesenteric vasculature and utimately the bowel. However, when involved, polyarteritis nodosa most commonly (50-70%) is the underlying cause. Polyarteritis nodosa may cause small arterial aneurysms as well as occlusions. Systemic lupus erythematous, Henoch Schloein Purpura, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss disease, Buerger disease, and hemolytic uremic syndrome may also occlude small mesenteric arteries and intramural mesenteric veins. Takayasu’s arteritis and giant cell arteritis affect primarily the large vessels.

While the clinical symptoms may overlap with other forms bowel ischemia, arteritis tends to affect younger patients. An appropriately elicited medical history may focus the clinician to the correct diagnosis (27). Additionally, the associated ischemia and extensive wall thickening may involve unusual sites such as the stomach, duodenum, occasionally jejunum, ileum and rectum (27). The associated GI complications can be devastating ranging from regional gangrene to hemorrhage and perforation. (40).

Aortic dissection with extension into or occlusion of the mesenteric arteries may result in bowel ischemia and hemorrhage (25). Isolated dissection of superior mesentery artery is an exceedingly rare occurrence resulting in acute ischemia and may be associated with underlying fibrous dysplasia of the mesenteric artery.

Another rare cause of mesenteric ischemia is a mesenteric aneurysm, which may rupture and cause pain and hemorrhage. Most splanchnic true and pseudoaneurysms are found in asymptomatic patients on cross-section imaging or autopsy (0.01%-0.25%) with SMA involved 6% of the times. (25).

The development of intestinal ischemia from an arterially obstructing lesion depends also upon the location of the obstruction, the patient’s collateral vasculature, and the acuity and degree of the obstruction. The presence of two collateral arcades, the first connecting the celiac artery and the SMA via the pancreaticoduodenal and gastroduodenal arteries, and the second connecting SMA to IMA via Arch of Rioland and marginal artery of Drummond, allow bidrectional flow which can bypass obstructing lesions. In the presence of obstructions involving all three major arteries (celiac, SMA, and IMA) the phrenic, lumbar, and pelvic collateral arteries may dilate to provide accessory visceral blood flow. However, if the lesion is distal to the point of collateral flow, the collateral supply is ineffective and ischemia is more likely to ensue (28). Additionally, if there is rapid development of obstruction from an embolus or vasculitis, the patient may not be able to develop sufficient collaterals in time to provide perfusion. Patients with diabetes or severe diffuse atherosclerotic disease may have limited ability to develop collaterals, which places diabetics at high risk for bowel ischemia from even mild lesions (28).

Arterial Ischemia –bowel wall evaluation

Abnormal intestinal mural enhancement is critical to assess when there is a suspicion of bowel ischemia. The intensity of bowel wall enhancement varies depending up on the etiology of the ischemia. Normal small and large bowel show homogenous mural enhancement, particularly in the venous phase of enhancement. During the early phase of arterial occlusion, a key finding is substantially diminished bowel mural enhancement [Figure 6] (14, 29, 30), and has been termed “pale ischemia”. Alternatively, in the post-reperfusion period after arterial injury, hyperenhancement of the bowel is present [Figure 7] (29), much like “shock bowel”. Commonly, “shock bowel” may be seen immediately adjacent to “pale ischemia” due to the development of collateral pathways in acute bowel ischemia.

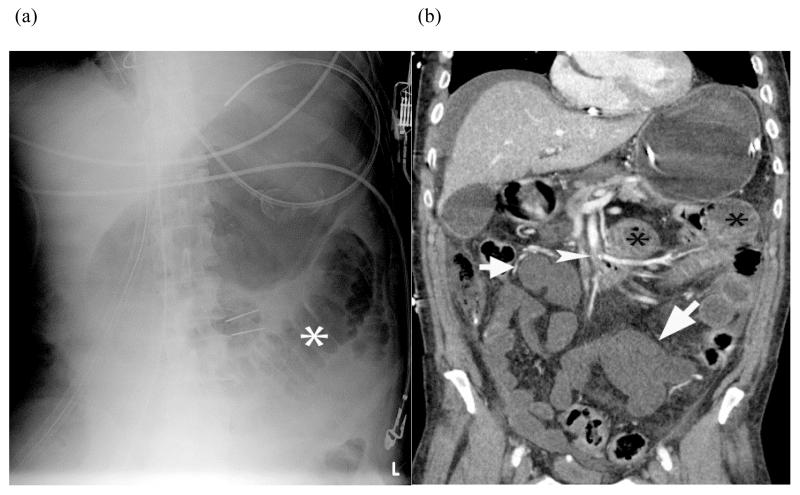

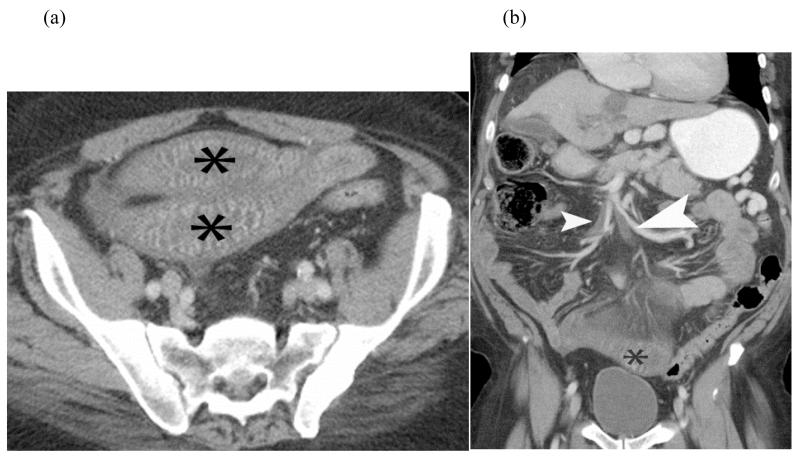

FIGURE 6.

Plain radiograph of small bowel ischemia – Plain radiograph (a) shows a focally dilated “paper thin” segment of small bowel (*) that had persisted over several consecutive examinations. Subsequent coronal reformatted CT image (b) of the same patient shows the corresponding dilated segment (*) as well as other fluid filled segments of small bowel with absent mural enhancement (white arrow) and clot in the SMA (white arrow head). At laparotomy, 220 centimeters of dead bowel was found.

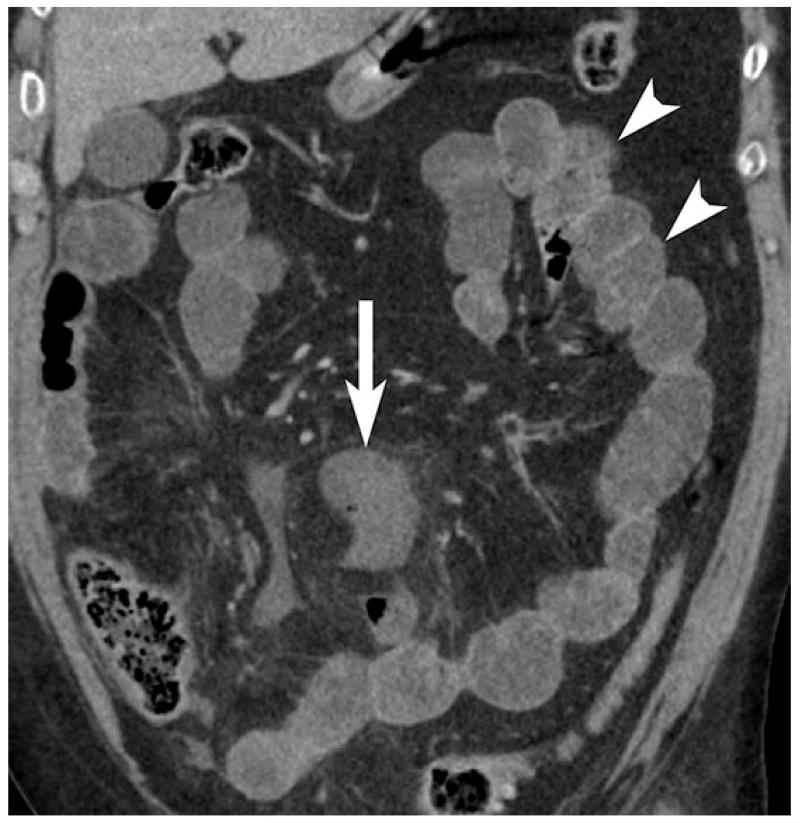

Figure 7.

54 year old with SMA thrombus causing arterial bowel ischemia. Thin hypoenhancing bowel wall (arrow) and associated subtle mesenteric fat stranding is seen on coronal contrast enhanced CT image. Mural enhancement of non-ischemic jejunum (arrowheads) is seen in the left upper abdomen.

Pneumatosis intestinalis, which is the presence of locules of air within or a contiguous line of gas dissecting between bowel layers, is commonly described as a finding of transmural bowel ischemia [Figure 8]. When pneumatosis intestinalis is present along with portomesenteric gas, the specificity approaches approximately 100% for ischemic bowel. However, it is critical to note that in the absence of a clinical signs or symptoms of ischemia, the finding of isolated pneumatosis intestinalis should not trigger a definite diagnosis of intestinal ischemia (31-33). Pneumatosis intestinalis is not a specific finding of intestinal ischemia and may occur in a wide range of non-emergent benign scenarios [Figure 9]. When found however, bowel ischemia must be excluded first and foremost.

Figure 8.

Coronal contrast enhanced CT shows pale arterial ischemia with absent mural enhancement in a segment of small bowel (arrow). An adjacent segment of small bowel shows mural hyperenhancement (arrowhead), indicating bowel reperfusion injury.

Figure 9.

Coronal CT showing pneumatosis intestinalis; gas within the bowel wall (white arrow) can be suggestive bowel ischemia and infarction in the appropriate clinical setting. In the absence of other concerning CT findings, clinical signs, or symptoms of bowel ischemia, a benign cause pneumatosis should be considered.

In exclusively arterial occlusive mesenteric ischemia, the presence of segmental mesenteric fat stranding and free fluid interleaved between the mesenteric folds associated with the poorly enhancing bowel is highly suggestive of transmural infarction (34-37). While the severity of bowel ischemia is variable, perforation and peritonitis are high mortality complications of infarction.

Assessing the mural thickness of the gut for findings of intestinal ischemia may be problematic because bowel wall thickness depends on the etiology, site, extent, duration, and superimposed complications of intestinal disease. Furthermore, there is significant variation in thickness of large bowel depending up on distention Typically, gas or fluid filled normal small bowel wall thickness measures 1-2 mm, whereas the wall of partially collapsed bowel may measure 2-3 mm in the ileum and colon. Normal partially collapsed jejunum may have an even greater apparent thickness than 3 mm (27, 38, 39).

In the setting of primary arterial occlusion resulting in ischemia or transmural infarction, small bowel may become dilated with a classic “paper-thin wall” appearance [Figure 5b]. This appearance occurs as a result of loss of bowel wall tissue, vasculature, and muscular tone. However, in cases of reversible ischemia, mild bowel thickening may be noted (27, 39). When acute arterial occlusion results in intramural hemorrhage, edema and/or superimposed infection, abnormal bowel wall thickening up to 15 mm of the small and large intestines is commonly demonstrated [Figure 10] (34).

Figure 10.

Benign pneumatosis – CT images in lung window of a patient who presented with abdominal pain after trauma. Coronal image (a) shows pneumatosis cystoides coli (black arrow), while the axial images (b) shows small volume of pneumoperitoneum (black arrow head). Patient was admitted for observation and discharged without any intervention as his pain resolved spontaneously.

Venous Ischemia – mesenteric vein evaluation

Mesenteric venous occlusion comprises up to 10% of bowel ischemia cases and is usually associated with mechanical obstruction, but can be due to venous thrombosis (37). The latter may occur in patients with hypercoagulable syndromes such as sickle cell disease, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, polycythemia vera, protein C/S deficiency or in hypercoagulable states such as pregnancy and with the use of oral contraceptives. Underlying inflammatory diseases such a vasculitis (e.g. SLE) also result in occlusion of small intramural mesenteric veins. Infectious causes, albeit rare, such as enterocolic lymphocytic phlebitis have also been known to occlude small intramural colonic veins leading to ischemia(2, 22, 25).

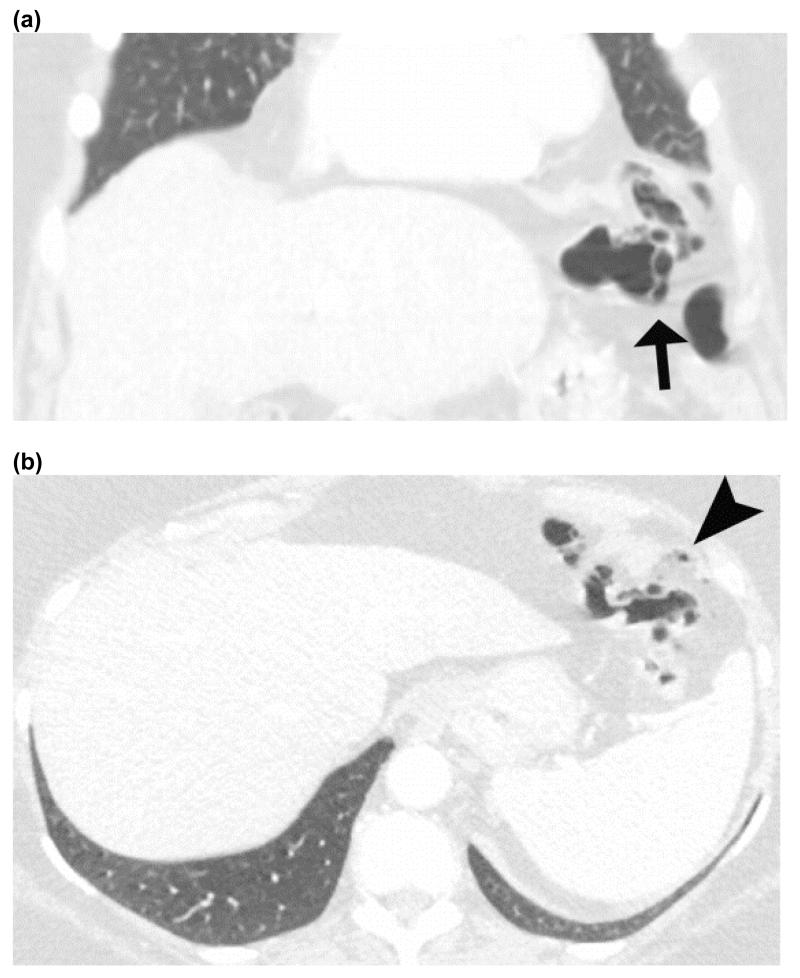

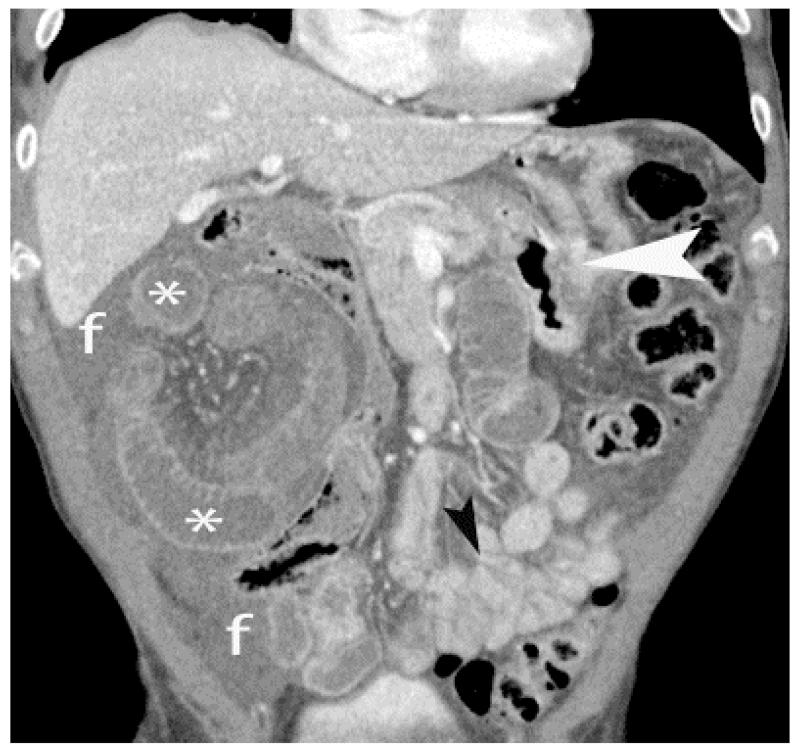

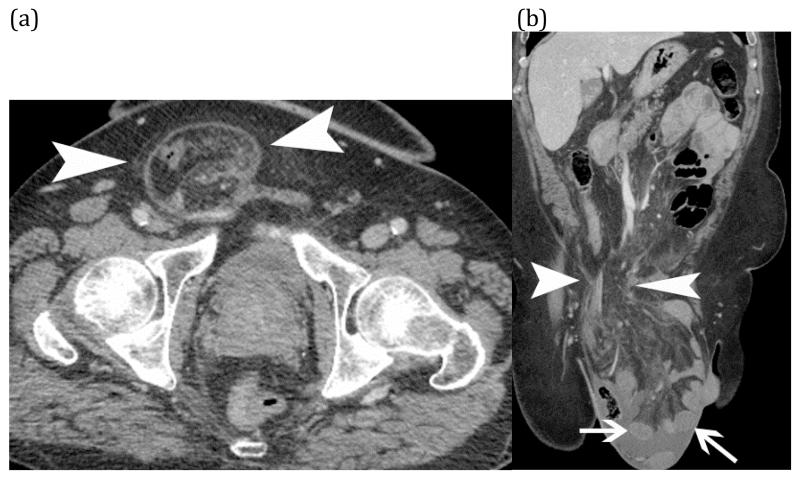

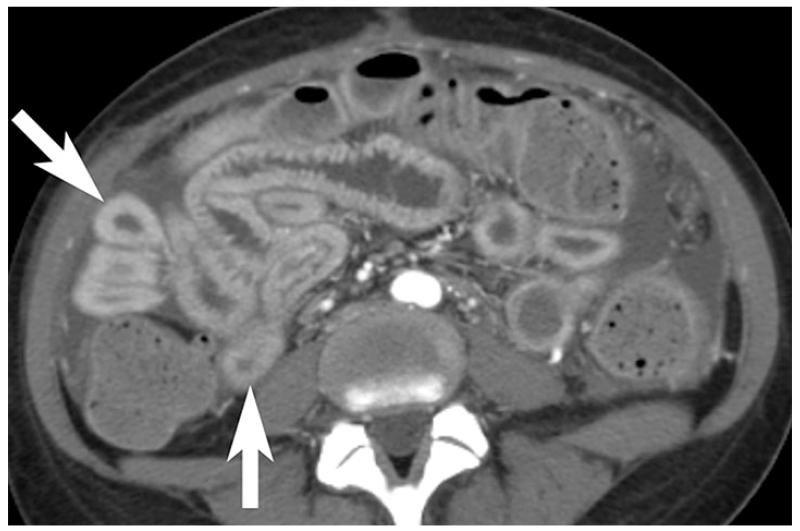

Venous circulation can also be compromised in association with bowel strangulation, typically observed in volvulus, intussusception and closed-loop obstructions. Bowel ischemia occurs in 10% of small bowel obstructions; initially the low-pressure venous outflow is compressed with subsequent loss of arterial inflow. The strangulated segments of bowel are usually fluid filled, distended, and edematous with ascites (40, 41) [Figures 11 & 12]. The enhancement is usually variable depending upon the duration of obstruction. Early obstruction, with only venous compromise, may demonstrate hyperenhancement. Subacute findings with compromise of arterial supply demonstrate diminished or absent mural enhancement [Figure 11]. CT has high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of strangulation, 83-100% and 61-93%, respectively. Among all the findings, decreased mural enhancement, segmental mesenteric fat stranding, and adjacent ascites interleaved between folds of the mesentery are the most specific for bowel ischemia (42-45).

Figure 11.

Abnormally thickened bowel (white arrow) with mesenteric fat stranding and slightly decreased mural enhancement is non-specific; etiologies include bowel ischemia, edema, intramural hemorrhage and/or superimposed infection.

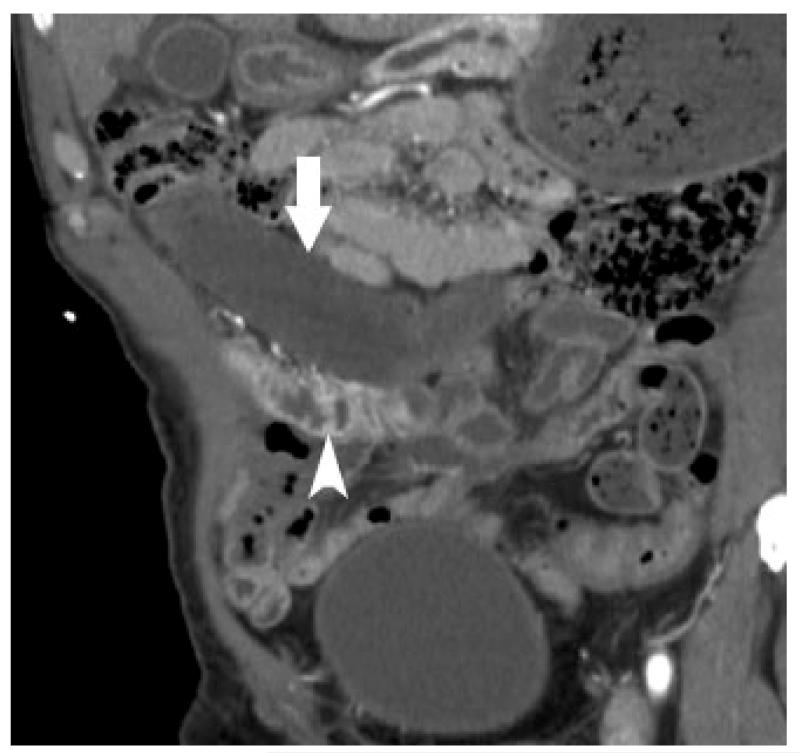

Figure 12.

Closed loop obstructionleading to mesenteric ischemia– CT scan of a patient who presented with sudden abdomen pain and nausea. A focally dilated segment of ischemic small bowel (*) with collapsed proximal (white arrowhead) and distal (black arrow head) small bowel is seen. The dilated ischemic bowel shows less enhancement than the collapsed segments of normal small bowel. The presence of adjacent free fluid (f) and mesenteric edema is also concerning for early ischemia.

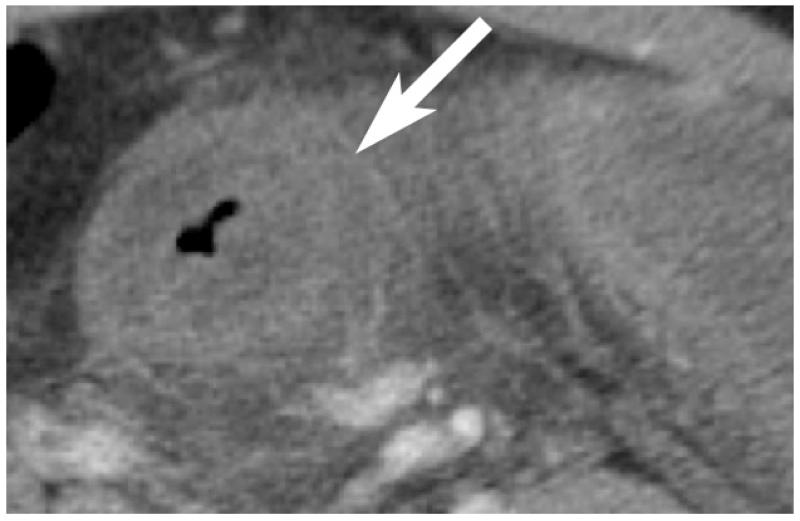

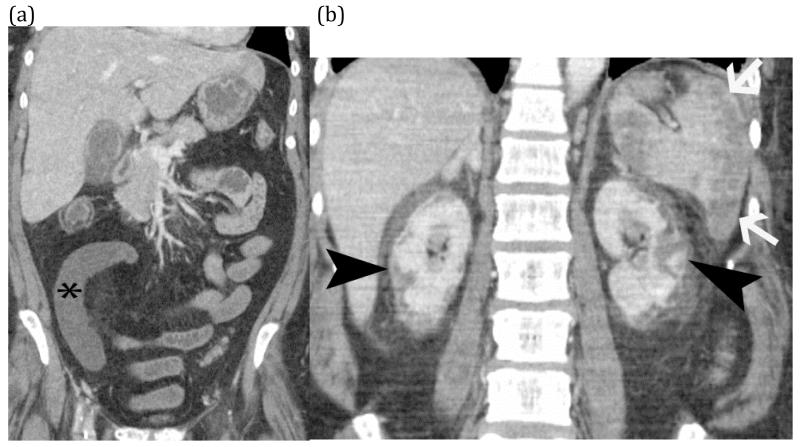

Thrombosis within the mesenteric veins may appear as a low-attenuation filling defect on contrast-enhanced CT and can be visualized in approximately 90% of cases of venous bowel ischemia [Figure 13](46, 47). In addition, due to venous outflow obstruction, engorged mesenteric veins are typically observed. The venous obstruction elevates hydrostatic pressure in the bowel wall because high pressure arterial inflow may continue despite venous occlusion. The vascular engorgement and edema of the bowel wall in turn lead to leakage of extravascular fluid into the bowel wall and mesentery [Figure 14]. The resultant edematous bowel may have a “halo” or “target” appearance due to mild mucosal enhancement, submucosal and muscularis propria nonenhancement, and mild serosal/subseserosal enhancement. This finding is easily identified on CT and the wall may measure up to 1.5 cm in thickness [Figure 15](37, 40). The impaired venous drainage ultimately results in loss of arterial supply resulting in ischemia and infarction with CT findings as described above. In these cases, bowel enhancement is significantly diminished or absent [Figure 16]. The presence of mesenteric edema and fluid may be more prominent in venous ischemia than in arterial ischemia.

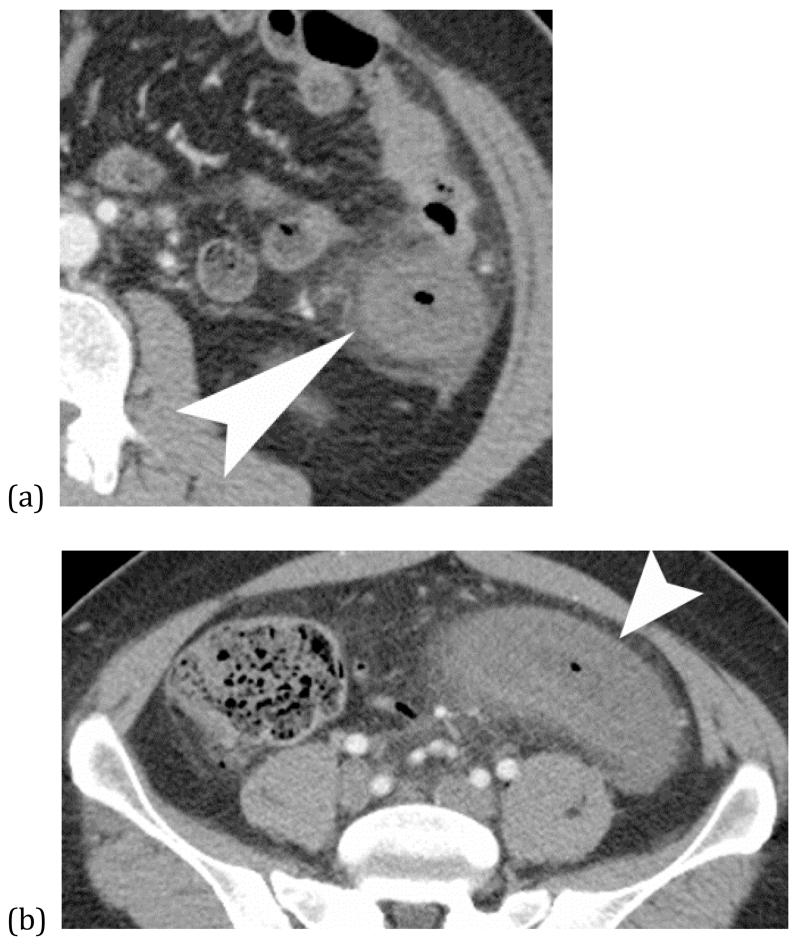

Figure 13.

Strangulated small bowel – Axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images of incarcerated small bowel (white arrows) in a large right inguinal hernia (white arrow heads). CT findings include hypoenhancement of the small bowel wall (arrows) with adjacent fluid and fat stranding of the associated mesentery in the hernia sac.

Figure 14.

Contrast enhanced CT shows low-attenuation clot within SMV (arrow) in a patient with pancreatitis

Figure 15.

Venous bowel ischemia from SMV thrombosis - Axial (a) and coronal reformatted (b) CT images of a patient with history of cirrhosis presenting with abdominal pain. Axial CT image shows marked bowel wall thickening with hyperenhancement and mesenteric edema. Coronal image shows thrombosis of the SMV. Venous ischemia presents with marked bowel thickening and may show some bowel wall enhancement, unlike arterial ischemia which often shows normal to thinned wall thickness and absent mural enhancement.

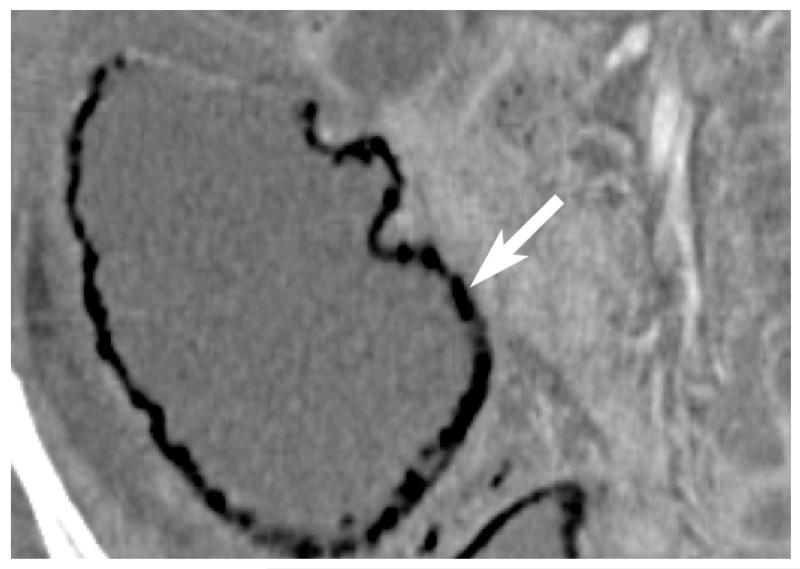

Figure 16.

“Target-appearance of bowel”; venous occlusion resulting in bowel edema with hyperenhancement (arrow) of serosal/subserosal layers, mesenteric stranding, and small adjacent free fluid (arrowhead).

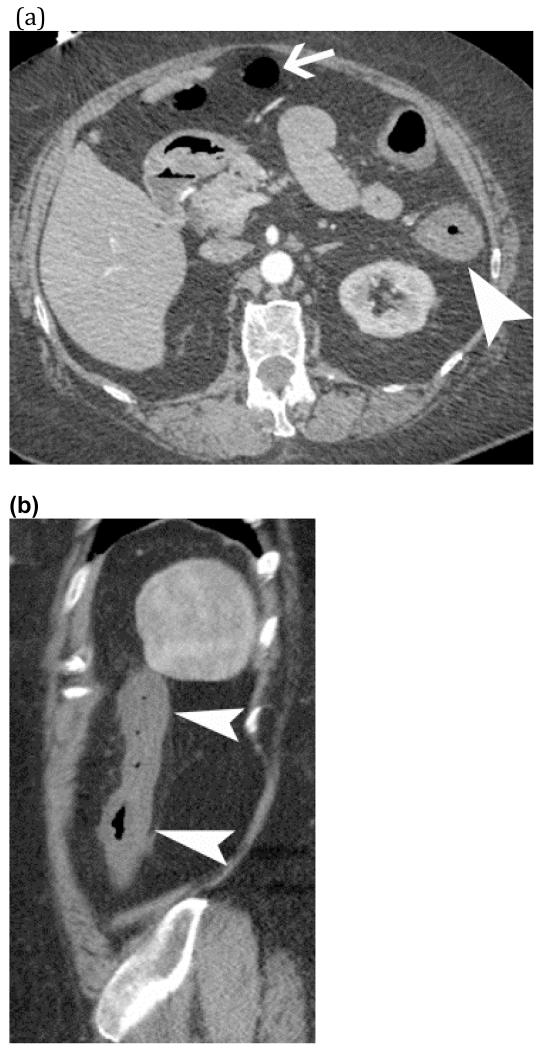

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI)

NOMI is usually multifactorial in etiology. Depending on the definition, non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia may comprise up to 20-30% of all acute mesenteric ischemic syndromes and may be associated with high mortality ranging from 30-93% (48). There has been an overall decrease in incidence of this syndrome with improved management of hemodynamic instability. In the setting of septic, hemorrhagic or cardiogenic shock, a profound drop of systemic blood pressure results in reflexive mesenteric arterial vasoconstriction with diversion of blood flow to the brain and heart. Other causes of reduced mesenteric blood flow include blunt abdominal trauma, overdose of digitalis, use of amphetamines, cocaine and ergotamine or other agents resulting in vasoconstriction (40, 48, 49). Classic CT findings of “shock bowel” include diffuse small bowel wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement with relative sparing of the colon and mesenteric ascites [Figure 17]. However, one must also be familiar the normal differences in small bowel enhancement such as jejunal hyperenhancement compared to ileum due to higher density of valvulae conniventes [Figure 18]. The ischemic injuries range from localized superficial mucosa damage to the watershed regions (splenic flexure, rectosigmoid region) with sparing of the right colon. In severe cases, the entire bowel may be affected [Figures 19 and 20] (48-50). The diagnosis of NOMI may be challenging because CT findings overlap with other forms of bowel disease such as infectious and inflammatory enteritis and colitis. The pattern of bowel enhancement is quite variable, and may include absent, decreased, or hyperenhancement (37, 51, 52). In addition, hypoperfusion may lead to extravascular leakage of fluid resulting in bowel edema, mesenteric stranding, and ascites [Image 11].

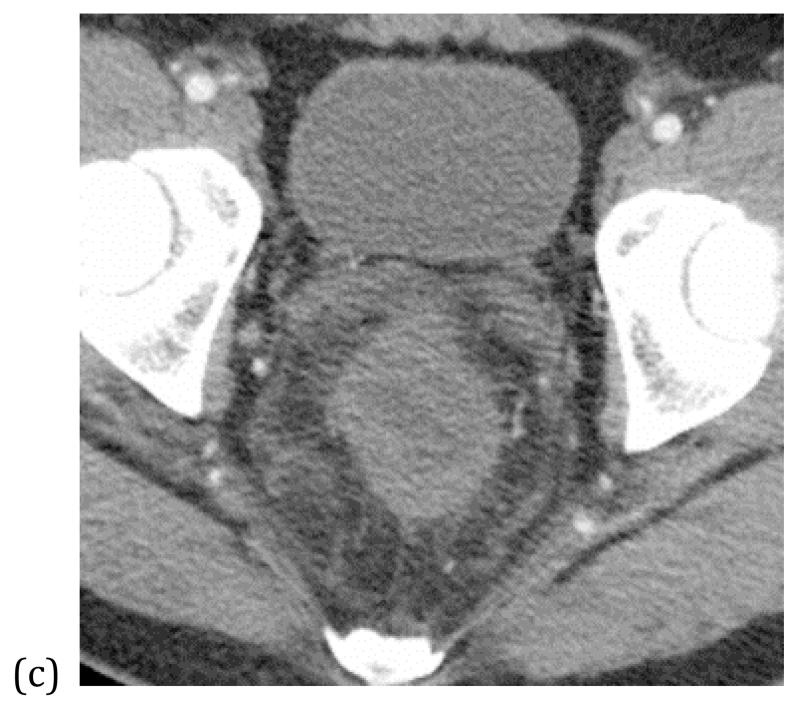

Figure 17.

Veno-occlusive disease – Three axial CT images (a-c) show marked bowel wall thickening with poor enhancement of the colon (white arrowhead) continuously from the descending colon to the rectum. Associated mesenteric fat stranding is seen.

Figure 18.

Shock bowel; mucosal hyperenhancement of thick walled small bowel (arrows) and ascites suggests recent hypotension.

FIGURE 19 (a) and (b).

Shock bowel from hypotension – Coronal CT images of an elderly man with presented sepsis and hypotension. The first image (a) shows non-enhancement of a small bowel segment (*) compatible with small bowel ischemia. Additional images (b) shows evidence of global hypotension and shock with renal cortical necrosis (black arrow heads) and splenic infarcts (white arrows).

FIGURE 20.

Watershed colonic Ischemia - Axial (a) and sagittal (b) CT images of a patient with hypotension shows segmental bowel wall thickening and poor mural enhancement of the descending colon (white arrowhead) with sparing of the transverse colon (white arrow).

Summary

Radiologists play a critical role in diagnosis and appropriate triage of patients with mesenteric ischemia. MDCT is an invaluable imaging test for patients with suspected mesenteric ischemia and outperforms all other medical tests. Since mesenteric ischemia may present with many different radiological appearances, an understanding of intestinal vascular and mesenteric anatomy as well as the pathophysiology of mesenteric ischemic disease helps improve the diagnosis of this challenging disease. The variable and overlapping appearance of various forms of mesenteric ischemia can be confusing, however, recognition of these findings is important for accurate diagnosis.

Key points.

Choice of CT technique affects the visibility of CT findings. Positive oral contrast may improve the detection of fluid collections, hematomas, and bowel leakage. Neutral oral contrast improves visualization of bowel wall hypo- or hyperenhancement.

Findings of bowel ischemia include mural hypoenhancement associated with adjacent mesenteric edema, pneumatosis, and free fluid

Hyperemia (shock bowel) may be seen adjacent to segments of acute pale ischemia

Evaluation of the arteries and veins leading to and from diseased bowel can reveal the etiology of bowel ischemia as embolic, dissection, thrombosis, inflammation, or malignant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. American family physician. 2008;77(7):971–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruotolo RA, Evans SR. Mesenteric ischemia in the elderly. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 1999;15(3):527–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;345(23):1683–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamatakos M, Stefanaki C, Mastrokalos D, et al. Mesenteric ischemia: still a deadly puzzle for the medical community. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2008;216(3):197–204. doi: 10.1620/tjem.216.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang HH, Chang YC, Yen DH, et al. Clinical factors and outcomes in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia in the emergency department. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association: JCMA. 2005;68(7):299–306. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barajas RF, Jr., Yeh BM, Webb EM, Westphalen AC, Poder L, Coakley FV. Spectrum of CT findings in patients with atrial fibrillation and nontraumatic acute abdomen. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2009;193(2):485–92. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoots IG, Levi MM, Reekers JA, Lameris JS, van Gulik TM. Thrombolytic therapy for acute superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology: JVIR. 2005;16(3):317–29. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141719.24321.0B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kougias P, Lau D, El Sayed HF, Zhou W, Huynh TT, Lin PH. Determinants of mortality and treatment outcome following surgical interventions for acute mesenteric ischemia. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007;46(3):467–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hohenwalter EJ. Chronic mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis and treatment. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2009;26(4):345–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agaoglu N, Turkyilmaz S, Ovali E, Ucar F, Agaoglu C. Prevalence of prothrombotic abnormalities in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. World journal of surgery. 2005;29(9):1135–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7692-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuyoshi A, Obama K, Shinkura N, Ito T, Zaima M. Survival in nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia: early diagnosis by multidetector row computed tomography and early treatment with continuous intravenous high-dose prostaglandin E(1) Annals of surgery. 2007;246(2):229–35. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000263157.59422.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angel W, Angel J, Shankar S. Ischemic bowel: uncommon imaging findings in a case of cocaine enteropathy. Journal of radiology case reports. 2013;7(2):38–43. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v7i2.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrett T, Upponi S, Benaglia T, Tasker AD. Multidetector CT findings in patients with mesenteric ischaemia following cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. The British journal of radiology. 2013;86(1030):20130277. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jancelewicz T, Vu LT, Shawo AE, Yeh B, Gasper WJ, Harris HW. Predicting strangulated small bowel obstruction: an old problem revisited. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2009;13(1):93–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SJ, Coakley FV, Webb EM, Westphalen AC, Poder L, Yeh BM. Computed tomography of the acute abdomen in patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2009;33(2):280–5. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31817f4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mamode N, Pickford I, Leiberman P. Failure to improve outcome in acute mesenteric ischaemia: seven-year review. The European journal of surgery = Acta chirurgica. 1999;165(3):203–8. doi: 10.1080/110241599750007054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potretzke TA, Brace CL, Lubner MG, Sampson LA, Willey BJ, Lee FT., Jr. Early Small-Bowel Ischemia: Dual-Energy CT Improves Conspicuity Compared with Conventional CT in a Swine Model. Radiology. 2014:140875. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenblum JD, Boyle CM, Schwartz LB. The mesenteric circulation. Anatomy and physiology. The Surgical clinics of North America. 1997;77(2):289–306. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haglund U, Bergqvist D. Intestinal ischemia -- the basics. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery / Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 1999;384(3):233–8. doi: 10.1007/s004230050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo WE, Ballantyne GH, Gusberg RJ. Ischemic colitis: patterns and prognosis. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 1992;35(8):726–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02050319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ball WS, Jr., Seigel RS, Goldthorn JF, Kosloske AM. Colonic strictures in infants following intestinal ischemia. Treatment by balloon catheter dilatation. Radiology. 1983;149(2):469–71. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.2.6622690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brandt L, Boley S, Goldberg L, Mitsudo S, Berman A. Colitis in the elderly. A reappraisal. The American journal of gastroenterology. 1981;76(3):239–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehead R. The pathology of ischemia of the intestines. Pathology annual. 1976;11:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inderbitzi R, Wagner HE, Seiler C, Stirnemann P, Gertsch P. Acute mesenteric ischaemia. The European journal of surgery = Acta chirurgica. 1992;158(2):123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine JS, Jacobson ED. Intestinal ischemic disorders. Digestive diseases. 1995;13(1):3–24. doi: 10.1159/000171483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkpatrick ID, Kroeker MA, Greenberg HM. Biphasic CT with mesenteric CT angiography in the evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia: initial experience. Radiology. 2003;229(1):91–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291020991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H, Ros PR. CT of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 2003;226(3):635–50. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cognet F, Ben Salem D, Dranssart M, et al. Chronic mesenteric ischemia: imaging and percutaneous treatment. Radiographics: a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2002;22(4):863–79. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl07863. discussion 79-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein HM, Lensing R, Klosterhalfen B, Tons C, Gunther RW. Diagnostic imaging of mesenteric infarction. Radiology. 1995;197(1):79–82. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.1.7568858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taourel PG, Deneuville M, Pradel JA, Regent D, Bruel JM. Acute mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis with contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 1996;199(3):632–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.3.8637978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonopoulos P, Siaperas P, Troumboukis N, Demonakou M, Alexiou K, Economou N. A case of pneumoperitoneum and retropneumoperitoneum without bowel perforation due to extensive intestinal necrosis as a complication to chemotherapy: CT evaluation. Acta radiologica short reports. 2013;2(7):2047981613498723. doi: 10.1177/2047981613498723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HS, Cho YW, Kim KJ, Lee JS, Lee SS, Yang SK. A simple score for predicting mortality in patients with pneumatosis intestinalis. European journal of radiology. 2014;83(4):639–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milone M, Di Minno MN, Musella M, et al. Computed tomography findings of pneumatosis and portomesenteric venous gas in acute bowel ischemia. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2013;19(39):6579–84. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horton KM, Fishman EK. Multidetector CT angiography in the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2007;45(2):275–88. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2007;188(6):1604–13. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kernagis LY, Levine MS, Jacobs JE. Pneumatosis intestinalis in patients with ischemia: correlation of CT findings with viability of the bowel. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2003;180(3):733–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiesner W, Mortele KJ, Glickman JN, Ji H, Ros PR. Pneumatosis intestinalis and portomesenteric venous gas in intestinal ischemia: correlation of CT findings with severity of ischemia and clinical outcome. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2001;177(6):1319–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macari M, Balthazar EJ. CT of bowel wall thickening: significance and pitfalls of interpretation. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2001;176(5):1105–16. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.5.1761105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macari M, Megibow AJ, Balthazar EJ. A pattern approach to the abnormal small bowel: observations at MDCT and CT enterography. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2007;188(5):1344–55. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rha SE, Ha HK, Lee SH, et al. CT and MR imaging findings of bowel ischemia from various primary causes. Radiographics: a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2000;20(1):29–42. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.1.g00ja0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turnage RH, Guice KS, Oldham KT. Endotoxemia and remote organ injury following intestinal reperfusion. The Journal of surgical research. 1994;56(6):571–8. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balthazar EJ, Liebeskind ME, Macari M. Intestinal ischemia in patients in whom small bowel obstruction is suspected: evaluation of accuracy, limitations, and clinical implications of CT in diagnosis. Radiology. 1997;205(2):519–22. doi: 10.1148/radiology.205.2.9356638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frager D, Baer JW, Medwid SW, Rothpearl A, Bossart P. Detection of intestinal ischemia in patients with acute small-bowel obstruction due to adhesions or hernia: efficacy of CT. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1996;166(1):67–71. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ha HK, Kim JS, Lee MS, et al. Differentiation of simple and strangulated small-bowel obstructions: usefulness of known CT criteria. Radiology. 1997;204(2):507–12. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zalcman M, Sy M, Donckier V, Closset J, Gansbeke DV. Helical CT signs in the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia in small-bowel obstruction. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2000;175(6):1601–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.6.1751601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradbury MS, Kavanagh PV, Bechtold RE, et al. Mesenteric venous thrombosis: diagnosis and noninvasive imaging. Radiographics: a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2002;22(3):527–41. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harward TR, Green D, Bergan JJ, Rizzo RJ, Yao JS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Journal of vascular surgery. 1989;9(2):328–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segatto E, Mortele KJ, Ji H, Wiesner W, Ros PR. Acute small bowel ischemia: CT imaging findings. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2003;24(5):364–76. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(03)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trompeter M, Brazda T, Remy CT, Vestring T, Reimer P. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia: etiology, diagnosis, and interventional therapy. European radiology. 2002;12(5):1179–87. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim AY, Ha HK. Evaluation of suspected mesenteric ischemia: efficacy of radiologic studies. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2003;41(2):327–42. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chou CK. CT manifestations of bowel ischemia. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2002;178(1):87–91. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chou CK, Mak CW, Tzeng WS, Chang JM. CT of small bowel ischemia. Abdominal imaging. 2004;29(1):18–22. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]