Abstract

Background and objectives

Although multiple factors influence access to nephrologist care in patients with CKD stages 4–5, the geographic determinants within the United States are incompletely understood. In this study, we examined interstate differences in nephrologist care among patients approaching ESRD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This national, population-based analysis included 373,986 adult patients from the US Renal Data System, who initiated maintenance dialysis between 2005 and 2009. Multilevel logistic regression was used to examine interstate variation in nephrologist care (≥12 months before ESRD) for overall and four race–age subpopulations (black or white and older or younger than 65 years).

Results

The average state-level probability of having received nephrologist care in all states combined was 28.8% (95% confidence interval, 25.2% to 32.7%) overall and was lowest (24.3%) in the younger black subpopulation. Even at these lower levels, state-level probabilities varied considerably across states in overall and subpopulations (all P<0.001). Overall, excluding the states in the upper and lower five percentiles, the remaining states had a probability of receiving care that varied from 18.5% to 41.9%. The lower probability of receiving nephrologist care for blacks than whites among younger patients noted in most states was attenuated in older patients. Geographically, all New England states and most Midwest states had higher than average probability, whereas most Middle Atlantic and Southern states had lower than average probability. After controlling for patient factors, three state-characteristic categories, including general healthcare access measured by percentage of uninsured persons and Medicaid program performance scores, preventive care measured by percentage of receiving recommended preventive care, and socioeconomic status, contributed 55%–66% of interstate variation.

Conclusions

Patients living in states with better health service and socioeconomic characteristics were more likely to receive predialysis nephrologist care. The reported national black–white difference in nephrologist care was primarily driven by younger black patients being the least likely to receive care.

Keywords: CKD, racial difference, US Renal Data System, pre-ESRD care, state characteristics

Introduction

CKD is a growing public health concern in the United States (1). The consequences of CKD are severe, including progression to ESRD and premature development of cardiovascular diseases and death (2–7). Although no randomized trials have been performed, >20 years of accumulating evidence has suggested that early nephrologist care is associated with slower CKD progression and lower rates of adverse outcomes (8–16). Despite practice guidelines recommending that patients in CKD stages 4–5 should be under nephrologist care (6,17), late nephrologist care is still common (18). Moreover, rates of receiving pre-ESRD nephrologist care have long been lower for blacks than whites (12,18,19).

Although the receipt of nephrologist care is influenced by individual as well as contextual factors such as those related to residence, prior studies have mostly examined individual factors (12,19–21), or the few studies that examined contextual factors have generally examined them separately (22–24) or were limited to certain regional areas (15,25). An important knowledge gap exists regarding broad regional (e.g., state-level) differences in the utilization of nephrologist care among patients with CKD stages 4–5. To date, little is known about whether the reported nationally low rates of nephrologist care represent a nationwide phenomenon in all states or are driven by several states with particularly lower rates. It is also not clear whether the nationally observed racial difference in nephrologist care is a nationwide phenomenon or primarily driven by several states. One of the Healthy People 2020 goals is to increase the proportion of patients with CKD receiving care from a nephrologist at least 12 months before the start of RRT by 10% from 2007 to 2020 (26). Understanding the barriers, including those related to geographic factors, will help achieve this specific national goal.

We therefore conducted a national analysis to determine interstate differences in receiving early nephrologist care among patients approaching ESRD. To better control for health insurance coverage that changes at age 65 years, we examined the entire cohort and then four race–age subcohorts (black or white and age <65 or ≥65 years). In addition, we sought to understand whether contextual factors defined at the state level are important to explain interstate differences in the receipt of care.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

This project was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board. We used the national ESRD population data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) (18). The revised 2005 US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ESRD Medical Evidence (ME) Report (CMS-2728) included new data on nephrologist care received before initiation of RRT. Patient race (black or white) and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) were classified in the ME form.

The study population included 373,986 patients who had newly begun maintenance dialysis, had completed the revised ME form between 2005 and 2009, were black or white, were aged ≥18 years at the initiation of dialysis, had not previously undergone kidney transplantation, and resided in any of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. We focused on white and black patients because fewer patients of other races did not permit us to generate reliable probability estimates for most states.

Study Variables

The dependent variable was whether a patient had received nephrologist care at least 12 months before the initiation of maintenance dialysis, based on the ME form. The duration of 12 months was chosen because it was specifically recommended by the Healthy People 2020 objectives (26).

State contextual characteristics considered were grouped into five categories, as follows: (1) general healthcare access, using the percentage of uninsured persons aged 18–64 years within the state (27) and state Medicaid program performance comprising four performance scores on eligibility, services, quality of care, and reimbursement (28). These four performance scores were developed by the Public Citizen’s Health Research Group and were derived from 55 program performance indicators. Each state was assigned points for each of the four performance scores, with higher scores indicating greater access. The other categories were as follows: (2) preventive care, using percentage of adults aged ≥50 years in the state who received recommended screening and preventive care (29); (3) the state’s socioeconomic status, using the percentage of persons who did not complete high school, percentage of black residents, percentage of minority residents, and poverty rate in the state (27); (4) healthcare resources, using the numbers of primary care physicians (30) and nephrologists per population (31); and (5) geographical properties, using the percentage of urban population, percentage of farmland use, and overall population density (27).

The association of state-level factors and patients’ likelihood of receiving care was adjusted for the following patient-level factors at ESRD onset, which are available on the ME form: demographics (age and sex), employment status (at 6 months before ESRD), lifestyle behaviors (smoking, alcohol dependence, or drug dependence), physical/functional conditions, and presence/absence of each comorbid condition (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, various cardiovascular diseases, and cancer). In addition, we provided a descriptive summary for patient insurance coverage status at the time of ESRD onset. However, this variable was not included in the statistical models because its inclusion would obscure the association of state-level factors with nephrology care, which is the primary objective of this report.

Statistical Analyses

We utilized a multilevel modeling approach in this study (32). Multilevel models allow us to quantify the magnitude of interstate variation in receiving nephrologist care and determine to what extent the observed interstate variation can be accounted for by state-level factors, while simultaneously accounting for interstate differences in patient characteristics and also for nonindependence of patients nested within states. Specifically, we used three-stage random-intercepts logistic regression models that incorporate the hierarchical structure of patients nested within 50 US states and the District of Columbia, which were further nested within 10 geographic regions (Figure 1). Including regions in the models allows for generating more reliable estimates for small states by appropriately “borrowing” information from neighboring states within the same region, rather than globally from all states (33).

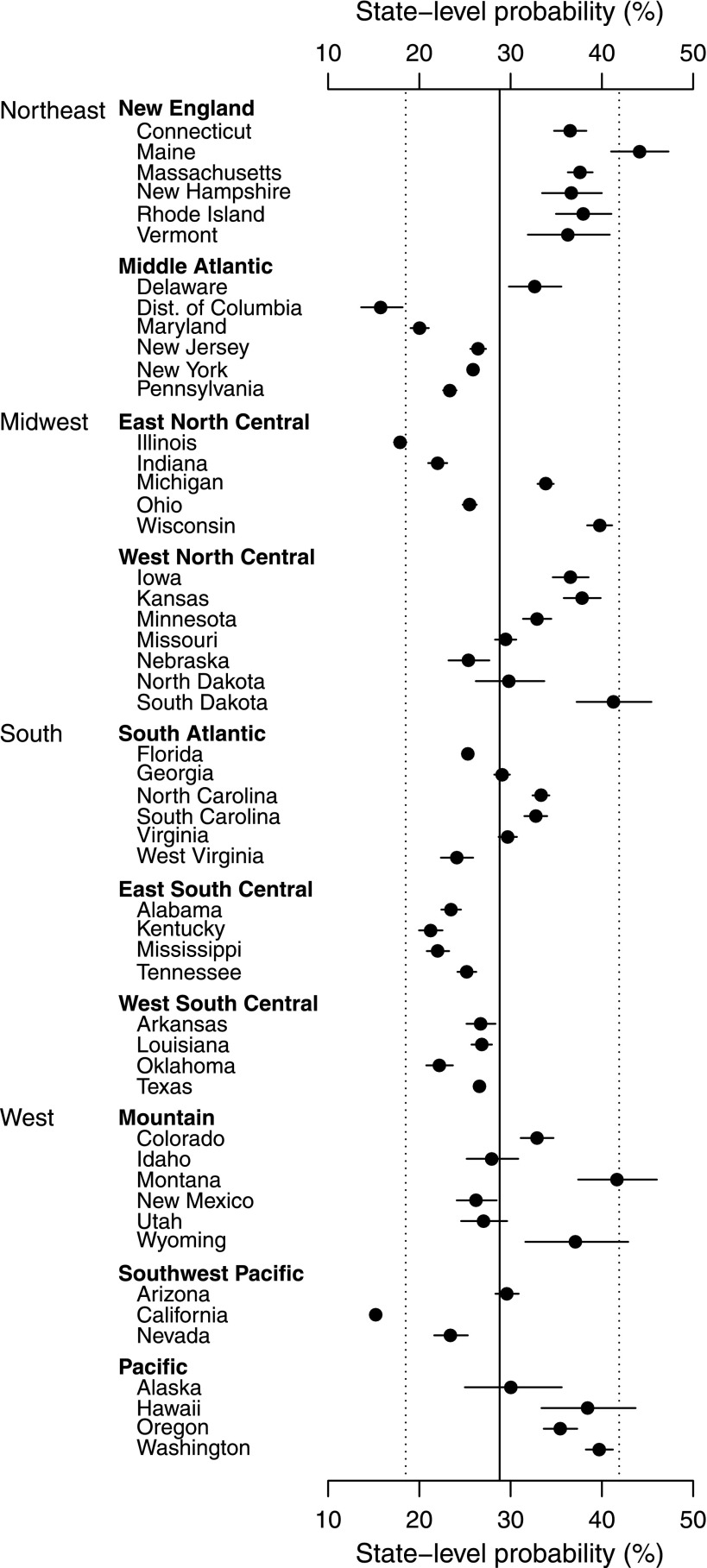

Figure 1.

Model-based estimates of unadjusted state-level probabilities and 95% confidence intervals of patients who had received nephrologist care at least 12 months before ESRD for all states. The probability estimates were obtained from the null model without covariates (model 1). The horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. The estimated average state-level probability is indicated by the solid vertical line. The estimated interval range of state-level probabilities for 90% of states is indicated by the left and right dotted lines. The 10 geographic regions were based on the nine US census divisions (50) with two pre hoc modifications to group neighboring states in the same region: Delaware, Maryland, and the District of Columbia were moved from the South Atlantic to the Middle Atlantic region, and a new Southwest Pacific region that consisted of Nevada, California, and Arizona was formed.

Our analyses were organized into several steps. A null model without covariate adjustments (model 1) was used to estimate unadjusted state-level probabilities of receiving nephrologist care for all states simultaneously, which are displayed for all patients in Figure 1. Similar figures by race–age subpopulations are not presented because a number of states had few black patients and the probability estimates for these states are highly unreliable. However, we can assess the interstate variation for each subpopulation with the normal distribution assumption. To estimate the interstate variation, we calculated the interval range that contained 90% of states, which would not be influenced by extreme states in the lower and upper five percentiles. Model 2 included only patient-level factors, whereas model 3 added one state-level factor at a time. Finally, model 4 expanded model 3 by including one or more categories of several state-level factors as described previously. Contribution of state-level factors to interstate variation in nephrologist care, after adjusting for patient factors, was assessed by the percent reduction in interstate variance between the model with (model 4) and the model without (model 2) the state factors (34).

We performed these analyses for all patients and then each of the race–age subpopulations by black or white and age <65 years or ≥65 years. Hispanics as a separate group were not examined due to the uneven distribution of Hispanics across states. However, we performed sensitivity analyses that excluded patients with Hispanic ethnicity (12.6%) to examine the robustness of the main findings. All analyses were performed using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software.

Results

Distributions of Patient and State Factors across States

Of 373,986 patients, 115,079 whites (61.3%) and 72,712 blacks (38.7%) comprised the group aged <65 years, and 145,588 whites (78.2%) and 40,607 blacks (21.8%) comprised the group aged ≥65 years. The median number of patients living in a state in this analysis was 4621 (Minnesota); the smallest was 325 (Wyoming) and the largest was 35,453 (California). As seen in Table 1, states differed greatly in many aspects of patient and state characteristics. For example, the median percentage of uninsured patients was 7.2%, with the 10th and 90th percentiles ranging from 2.7% to 10.7%, whereas the 10th and 90th percentiles for the percentage of residents in poverty ranged from 9.9% to 17.5%.

Table 1.

Distributions of patient-level and state-level factors across states

| Factor | Distribution across 50 States and the District of Columbia | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 10th Percentile | 90th Percentile | |

| Patient-level factors across states | |||

| Number of patients in a state | 4621 | 690 | 16,260 |

| Male patients | 57.1 | 53.4 | 59.4 |

| Black patients | 18.8 | 1.9 | 56.1 |

| Mean age at ESRD onset (yr) | 63.8 | 61.3 | 66.4 |

| Employment at 6 mo before ESRD | 85.3 | 78.4 | 92.1 |

| Current tobacco smokers | 7.6 | 5.1 | 10.3 |

| Hypertension | 84.6 | 82.0 | 88.0 |

| Diabetes | 52.3 | 47.9 | 56.7 |

| Congestive heart failure | 33.7 | 26.5 | 40.2 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 25.7 | 15.1 | 31.9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10.2 | 7.6 | 11.7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 15.6 | 10.5 | 20.8 |

| Cancer | 8.5 | 6.2 | 11.5 |

| Health insurance coverage | |||

| No insurance | 7.2 | 2.7 | 10.7 |

| Single insurance | |||

| Medicaid | 9.0 | 5.7 | 12.0 |

| Medicare | 14.9 | 9.9 | 19.4 |

| Employer-group | 16.0 | 12.7 | 19.2 |

| Other | 9.1 | 5.7 | 16.1 |

| Two types of insurance | |||

| Medicare and Medicaid | 10.3 | 6.6 | 14.4 |

| Medicare and one other non-Medicaid | 30.2 | 20.6 | 39.9 |

| Two other types | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.6 |

| Three or more types of insurance | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| State-level factors across states | |||

| General healthcare access | |||

| Uninsured persons aged 18–64 yr | 17.6 | 13.3 | 23.8 |

| State Medicaid program performance (higher scores mean greater access) | |||

| Eligibility score | 183.0 | 108.5 | 254.5 |

| Services score | 118.2 | 82.9 | 145.1 |

| Quality of care score | 56.4 | 18.8 | 105.1 |

| Reimbursement scorea | 115.3 | 68.8 | 160.1 |

| Preventive care | |||

| Aged >50 yr receiving recommended screening and preventive care | 42.4 | 37.3 | 49.9 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Aged >25 yr who did not complete high school | 17.9 | 12.8 | 24.7 |

| Persons in poverty | 12.3 | 9.9 | 17.5 |

| Black residents | 6.8 | 0.6 | 27.9 |

| Minority residents | 18.4 | 7.6 | 36.0 |

| Healthcare resources | |||

| Primary care physicians (per 10,000 population) | 9.8 | 8.3 | 11.9 |

| Nephrologists (per million population) | 26.6 | 14.4 | 34.6 |

| Geographical properties | |||

| Population density (natural log of persons per square mile) | 4.5 | 2.8 | 6.3 |

| Urban population | 71.7 | 52.4 | 91.4 |

| Farmland use | 33.2 | 9.1 | 77.5 |

Data are given in percentages unless otherwise indicated.

Reimbursement score in Tennessee was not available and was imputed using the mean score of all other states.

Interstate Variation in Nephrologist Care

The average probability that patients had received early nephrologist care in all states combined was 28.8%, with lower probability for blacks than whites among patients aged <65 years (24.3% versus 28.8%) and those aged >65 years (29.3% versus 30.8%) (Table 2). For patients of the same race, probability of care was always lower in the younger patients than in the older patients. The lower probabilities in the younger group and in blacks culminated in the younger blacks having the lowest likelihood to receive nephrologist care (24.3%) in the United States.

Table 2.

Model-based estimates of unadjusted state-level probabilities of receiving nephrologist care at least 12 months before ESRD, overall and by four race–age subpopulations

| Probability of Receiving Nephrologist Care | Overall Population (n=373,986) | Age <65 yr | Age ≥65 yr | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black(n=72,712) | White(n=115,079) | Black(n=40,591)a | White(n=145,588) | ||

| Average of all states, % (95% CI) | 28.8 (25.2 to 32.7) | 24.3 (20.7 to 28.5) | 28.8 (25.3 to 32.5) | 29.3 (25.1 to 33.8) | 30.8 (27.6 to 34.1) |

| Variation in the state-level probabilities (%) among states | |||||

| Interval range containing 90% of the states | (18.5, 41.9) | (14.7, 37.5) | (18.8, 41.3) | (17.3, 45.1) | (20.7, 43.2) |

| Length of the interval range | 23.4 | 22.8 | 22.5 | 27.8 | 22.5 |

The estimated averages and variations were obtained from the null model without covariates (model 1), which was separately fit to the overall population and each of the four subpopulations. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Seven states (Maine, Vermont, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho) were excluded from the analysis because of fewer older black patients in these states (16 older black patients in total).

There was a significant variation in the probability of receiving nephrologist care across states (P<0.001; Figure 1). All New England states and most Midwest states (e.g., Wisconsin, Iowa) had higher than average probability of receiving care, whereas most states in the Middle Atlantic and the South had lower than average probability. The multilevel model estimated that 90% of the states had a probability of receiving care that varied from 18.5% to 41.9% (states within the left and right dotted bands in Figure 1) (Table 2). An alternative way to express these data is that the difference in probability of receiving care between the states in the lower and upper five percentiles was >23.4 percentages.

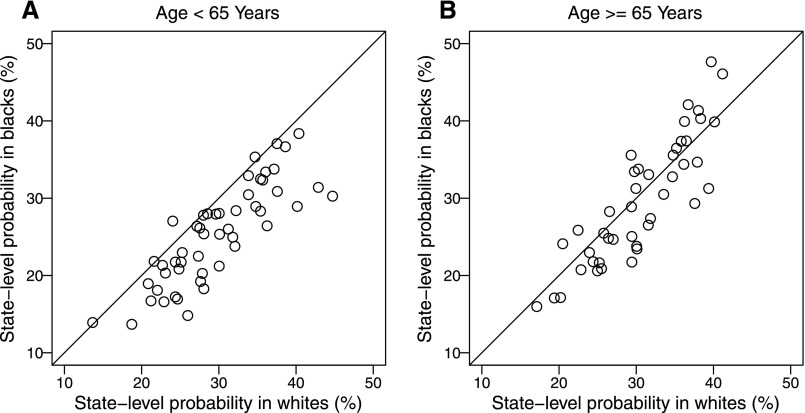

For race–age subpopulations, the variation among states was largest for older blacks but was similar for the other three subpopulations (Table 2). At the state level, racial difference was more prevalent in younger patients (<65 years) than in older patients. Among younger patients, blacks had an estimated probability of receiving care that was lower than their white counterparts in 47 states (dots under the diagonal line in Figure 2A), whereas there was no such dominant pattern among older patients (Figure 2B). After removing Hispanics, the results remained similar (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Model-based estimates of unadjusted state-level probabilities of patients who had received nephrologist care at least 12 months before ESRD for black patients (vertical axis) versus white patients (horizontal axis) by age subgroup. (A and B) The probability estimates for younger blacks, younger whites, older blacks, and older whites were obtained separately from the null model without covariates (model 1). Each dot represents an individual state. The diagonal lines are the equality lines. For age ≥65 years, seven small states (Maine, Vermont, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho) are not shown.

Contribution of State Factors to State-Level Variation in Nephrologist Care

To provide insights into the reasons for the variation in nephrologist care among states, we examined a number of state factors. After accounting for patient differences among states, the following state-level factors were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of nephrologist care in most of the four subpopulations: lower percentage of uninsured residents, higher scores on certain categories of state Medicaid performance, higher percentage of residents receiving preventive care, and higher socioeconomic status (Table 3). Interestingly, indicators of healthcare resources (primary care physicians and nephrologists) and geographic properties (e.g., population density and farmland use) had no or little association with the state level of receiving care.

Table 3.

Associations of each state-level factor and receipt of nephrologist care at least 12 months before ESRD, controlling for patient-level factors, separately for each of the four race–age subpopulations

| State-Level Factor | Age <65 yr | Age ≥65 yr | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | White | Black | White | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| General healthcare access, % or score per 1 SD | ||||||||

| Uninsured persons aged 18–64 yr (per 5%) | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.73 to 0.94) | 0.004 | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.19 |

| State Medicaid eligibility score | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.24) | 0.09 | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) | 0.02 | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.21) | 0.31 | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.14) | 0.28 |

| State Medicaid services score | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.20) | 0.22 | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.18) | 0.14 | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.20) | 0.40 | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.13) | 0.46 |

| State Medicaid quality of care score | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.18) | 0.32 | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.14) | 0.48 | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.18) | 0.54 | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.11) | 0.78 |

| State Medicaid reimbursement score | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.27) | 0.02 | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.16) | 0.24 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.30) | 0.02 | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.16) | 0.21 |

| Preventive care, % | ||||||||

| Aged >50 yr receiving recommended screening and preventive care (per 5%) | 1.22 (1.10 to 1.36) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.32) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.09 to 1.36) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.28) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status, % | ||||||||

| Aged >25 yr who did not complete high school (per 5%) | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.68 to 0.89) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.91) | <0.001 |

| Persons in poverty (per 5%) | 0.85 (0.72 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99) | 0.04 | 0.79 (0.66 to 0.95) | 0.01 | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.97) | 0.01 |

| Black residents (per 10%) | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.006 | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.01) | 0.08 | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.98) | 0.02 | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.97) | 0.01 |

| Minority residents (per 10%) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.95) | 0.001 | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 0.07 | 0.89 (0.81 to 0.98) | 0.01 | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.02 |

| Healthcare resources | ||||||||

| Primary care physicians (no. per 10,000 population) (per 1 physician) | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.04) | 0.72 | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) | 0.07 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 0.51 | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 0.92 |

| Nephrologists (no. per million population) (per 1 nephrologist) | 0.99 (0.99 to 1.00) | 0.14 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.54 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 0.08 | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.00) | 0.02 |

| Geographic properties, % | ||||||||

| Population density (natural log of persons per square mile) (per 1 unit) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.03) | 0.17 | 0.97 (0.91 to 1.04) | 0.40 | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 0.31 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 0.18 |

| Urban population (per 10%) | 0.92 (0.85 to 0.99) | 0.03 | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.11 | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.73 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 0.15 |

| Farmland use (per 20%) | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.10) | 0.92 | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.52 | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.13) | 0.84 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | 0.67 |

Results for each subpopulation were obtained separately. ORs and P values for each state-level factor were obtained individually (model 3), controlling for patient factors including age, sex, employment, lifestyle behaviors (smoking, alcohol, and drug dependence), and physical/functional conditions, presence of each comorbid condition (hypertension, diabetes, cardiac failure, atherosclerotic heart disease, other heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, amputation). Presented ORs are the ORs associated with the unit(s) increase as indicated for each of the factors. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

After accounting for patient differences among states, except for the subpopulation of whites aged >65 years, general healthcare access appeared to be the most important category, explaining approximately one-third of the total interstate variation in receipt of nephrologist care (Table 4). The preventive care and socioeconomic status within the state were the next two powerful categories, each explaining approximately 30% of the interstate variation. Collectively, these three categories explained 58%–66% of interstate variation. For the older–white subpopulation, the aforementioned three categories accounted for 55% of the interstate variation. Further addition of healthcare resources and geographic properties explained 61%–70% of the variation. We note that significant variation among states (P<0.001) still persisted even after accounting for all measured patient-level and state-level factors, indicating that these state-level factors, although contributing substantially, did not fully explain the state-level variation.

Table 4.

Contributions of combined state-level factors to the interstate variation in nephrologist care at least 12 months before ESRD, controlling for patient-level factors, separately for each of the four race–age subpopulations

| Category of the State-Level Factors | Percentage of Interstate Variation Explained by One or More of the Categories of State-Level Factorsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <65 yr | Age ≥65 yr | |||

| Black | White | Black | White | |

| General healthcare access | 38.1 | 31.7 | 32.0 | 18.1 |

| Preventive care | 29.7 | 30.6 | 29.7 | 29.2 |

| Socioeconomic status | 31.4 | 27.8 | 33.9 | 25.3 |

| Healthcare resources | 20.6 | 19.2 | 17.0 | 18.1 |

| Geographic properties | 7.8 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| General healthcare access, preventive care, and socioeconomic status combinedb | 65.9 | 58.2 | 61.8 | 55.3 |

| All five categories combinedb | 70.3 | 63.0 | 65.8 | 61.4 |

Results for each subpopulation were obtained separately and were calculated by the percent reduction in the interstate variation between the model with (model 4) and the model without (model 2) the state factors including one or more categories indicated in the first column, controlling for the patient factors.

Less than the numerical sum of the categories because of overlaps in the contributions of different categories.

Discussion

Using national incident maintenance dialysis patients and multilevel models, we report that the average state-level probability of having received nephrologist care ≥12 months before ESRD was only 24.3%–30.8% across the four race–age subpopulations (Table 2). Even at these lower levels, state-level probabilities of receiving care differed greatly among states. Overall, even excluding the states in the upper and lower five percentiles, the remaining states had a probability of receiving care that varied from 18.5% to 41.9%. Much of the interstate variations could be explained by the state contextual characteristics examined. Moreover, our finding of the racial differences among patients aged <65 years in many states, in contrast with little differences among patients aged ≥65 years, suggests that the reported national black–white difference in nephrologist care was primarily driven by the difference among younger patients, with younger blacks being less likely to receive care.

Although access to nephrologist care is influenced by both individual and contextual factors, prior studies exploring race as a determinant of predialysis care have largely examined patient factors alone or one or two contextual factors. For example, a recent national analysis of all patients with ESRD in the USRDS revealed the lower rates of initiating dialysis with an arteriovenous fistula for black and Hispanic patients than whites, but the analysis did not assess contextual factors jointly with the patient factors (35). The few studies that examined contextual factors found some particular aspects of residential areas associated with the lower likelihood of patients having received pre-ESRD care, including residential areas with larger proportions of black residents (23), counties with greater poverty (25), large metropolitan or rural counties (24), or states with more stringent Medicaid coverage (36). Another study found substantial variation in pre-ESRD care across treatment centers (15). Because these studies generally focused on a single or a few contextual factors, the relative contributions of these contextual factors to the pre-ESRD care are unknown. More importantly, these studies have not examined the broad regional differences, such as at the state level. This study is the first population-based analysis to examine the interstate variation in nephrologist care for the entire nation. Our findings are novel and significant, because they not only uncover the substantial state-level variation in pre-ESRD nephrologist care, but they also assess the relative contributions of the multiple contextual factors while simultaneously adjusting for patient-level factors.

Our findings of the substantial state-level variations in nephrologist care demonstrate that the individual’s likelihood of receiving nephrologist care depends highly on the state of the individual’s residence, regardless of age and race. These findings add to the prior research documenting similarly considerable state-level variation in healthcare utilization and care for patients with other chronic diseases (37–39). As shown in our analyses, the state-to-state variations in nephrologist care could be largely explained by state-to-state variations in health service characteristics, such as healthcare access (e.g., percentage of uninsured population), preventive care, and socioeconomic status (Table 4). Barriers to healthcare access are generally characterized by five categories: affordability, availability, accessibility, accommodation, and acceptability (36). It is likely that patients living in states with better health service characteristics face fewer barriers, which allow them to more easily access a nephrologist when needed. Our finding of the strong association between receipt of nephrologist care and state-level health service characteristics provides support for the notion that interventions at the state level that improve health insurance and preventive care can be effective to increase nephrologist care for patients with CKD. The implications of Affordable Care Act (ACA) for CKD are also substantial given the tremendous role that the nephrology community has played in piloting key ACA demonstration programs (40,41). Although the ACA has dramatically increased the number of low-income nonelderly adults eligible for insurance coverage including Medicaid (42), implementation of the ACA varies by state, which may limit its success (36,43). Public health policies implemented at the state level are likely to affect a larger number of patients.

Healthcare resources, such as availability in primary care providers and nephrologists, and geographic properties theoretically address the “availability” and “accessibility” categories. However, this study failed to observe the associations of these factors with nephrologist care. It is possible that the indicators measured at the state level, as we examined, are not sufficiently granular; using data in smaller geographic units may be more revealing.

Our finding of the lowest rates of receiving nephrologist care for younger blacks in many states demonstrates that the racial difference in nephrologist care was indeed nationwide down to the state level, rather than only in a few geographic clusters. The lower rate of receiving nephrologist care by the younger black patients with CKD, as described in this study, may be responsible, in part, for their poor outcomes reported in the literature (44–47). Novel strategies aimed at improving pre-ESRD care for younger black patients and implemented both nationally and at the state level could have far-reaching effects.

Several limitations in these analyses should be considered. Many factors may determine whether a patient would receive nephrologist care, including CKD referral patterns, patient behaviors, and/or the quality of providers that care for black and white patients (48). Our study did not directly address these causes. Our analyses were limited to access to care specifically provided by nephrologists and not by other practitioners who may also make significant contributions to clinical care. In addition, our study population did not include patients who died before the initiation of dialysis, refused dialysis, or were preemptively transplanted, which may limit the generalization of the findings. A prior study found some discrepancies in the reporting of pre-ESRD nephrologist care between the CMS-2728 and Medicare physician claims (49). The nature of these discrepancies is unclear because of the methodologic differences in the ascertainment of the first predialysis nephrologist visit. Finally, it should be noted that the probability of receiving nephrologist care estimated for each state reported herein is the average for that state. Within a given state, the probability may vary greatly at the county level, at the city level, or even within a zip code. Assessment of within-state variation at these smaller units is problematic because many units do not have sufficient numbers of incident dialysis patients to allow for reliable conclusions.

In summary, we report herein the robust findings that there is a considerable variation across states in the receipt of early predialysis nephrologist care, which could be largely explained by the state characteristics. Moreover, the commonly reported racial difference in nephrologist care is primarily driven by younger black patients who are least likely to receive care in most states. These findings shed light on the direction for public health policies that will be necessary to reduce disparities and achieve the Healthy People 2020 goals of improving nephrologist care for patients with advanced CKD (26).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant 5R01DK084200-04. In addition, K.C.N. is supported in part by NIH Grants P20-MD000182, 3P30AG021684, and UL1TR000124. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02800315/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “Border Health: State-Level Variation in Predialysis Nephrology Care,” on pages 1892–1894.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Barsoum R, Eckardt KU, Levin A, Levin N, Locatelli F, MacLeod A, Vanholder R, Walker R, Wang H: The burden of kidney disease: Improving global outcomes. Kidney Int 66: 1310–1314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foley RN, Murray AM, Li S, Herzog CA, McBean AM, Eggers PW, Collins AJ: Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population, 1998 to 1999. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 489–495, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH: Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med 164: 659–663, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J, Cohen EP, Collins AJ, Eckardt KU, Nahas ME, Jaber BL, Jadoul M, Levin A, Powe NR, Rossert J, Wheeler DC, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: Approaches and initiatives - a position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int 72: 247–259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, Parfrey P, Pfeffer M, Raij L, Spinosa DJ, Wilson PW, American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention : Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 108: 2154–2169, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golper TA: Predialysis nephrology care improves dialysis outcomes: Now what? Or chapter two. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 143–145, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungers P, Zingraff J, Albouze G, Chauveau P, Page B, Hannedouche T, Man NK: Late referral to maintenance dialysis: Detrimental consequences. Nephrol Dial Transplant 8: 1089–1093, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones C, Roderick P, Harris S, Rogerson M: Decline in kidney function before and after nephrology referral and the effect on survival in moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2133–2143, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Innes A, Rowe PA, Burden RP, Morgan AG: Early deaths on renal replacement therapy: The need for early nephrological referral. Nephrol Dial Transplant 7: 467–471, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avorn J, Bohn RL, Levy E, Levin R, Owen WF, Jr, Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ: Nephrologist care and mortality in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Arch Intern Med 162: 2002–2006, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng CL, Kern EF, Miller DR, Tiwari A, Maney M, Rajan M, Pogach L: Survival benefit of nephrologic care in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 168: 55–62, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClellan WM, Wasse H, McClellan AC, Kipp A, Waller LA, Rocco MV: Treatment center and geographic variability in pre-ESRD care associate with increased mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1078–1085, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minutolo R, Lapi F, Chiodini P, Simonetti M, Bianchini E, Pecchioli S, Cricelli I, Cricelli C, Piccinocchi G, Conte G, De Nicola L: Risk of ESRD and death in patients with CKD not referred to a nephrologist: A 7-year prospective study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1586–1593, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G, National Kidney Foundation : National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Renal Data System : USRDS 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ifudu O, Dawood M, Iofel Y, Valcourt JS, Friedman EA: Delayed referral of black, Hispanic, and older patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 728–733, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR: Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: A national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 192–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J: Determinants of delayed nephrologist referral in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 38: 1178–1184, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Kurella Tamura M: Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA 304: 180–186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prakash S, Rodriguez RA, Austin PC, Saskin R, Fernandez A, Moist LM, O’Hare AM: Racial composition of residential areas associates with access to pre-ESRD nephrology care. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1192–1199, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan G, Cheung AK, Ma JZ, Yu AJ, Greene T, Oliver MN, Yu W, Norris KC: The associations between race and geographic area and quality-of-care indicators in patients approaching ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 610–618, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClellan WM, Wasse H, McClellan AC, Holt J, Krisher J, Waller LA: Geographic concentration of poverty and arteriovenous fistula use among ESRD patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1776–1782, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2020, Washington, DC, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. Available at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx. Accessed May 2, 2011

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services : Area Resources Health File, Rockville, MD, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramírez de Arellano AB, Wolfe SM: Unsettling Scores: A Ranking of State Medicaid Programs, Washington, DC, Public Citizen Foundation, 2007. Available at http://www.citizen.org/Page.aspx?pid=737#executivesummary. Accessed May 2, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Commonwealth Fund: State Data Center. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/. Accessed May 10, 2010

- 30.The Robert Graham Center: Policy studies in family medicine and primary care. American Medical Association's master file. Washington, DC, American Academy of Family Physicians. Available at http://www.graham-center.org. Accessed May 10, 2011

- 31.US Medical Databases: http://www.usmeddata.com/. Accessed May 10, 2011

- 32.Goldstein H: Multilevel Statistical Models, London, Arnold, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gelman A, Hill J: Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer JD, Willett JB: Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence, New York, Oxford University Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarkowsky DS, Arhuidese IJ, Hicks CW, Canner JK, Qazi U, Obeid T, Schneider E, Abularrage CJ, Freischlag JA, Malas MB: Racial/ethnic disparities associated with initial hemodialysis access. JAMA Surg 150: 529–536, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurella-Tamura M, Goldstein BA, Hall YN, Mitani AA, Winkelmayer WC: State Medicaid coverage, ESRD incidence, and access to care. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1321–1329, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen MA, Tumlinson A: Understanding the state variation in Medicare home health care. The impact of Medicaid program characteristics, state policy, and provider attributes. Med Care 35: 618–633, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arday DR, Fleming BB, Keller DK, Pendergrass PW, Vaughn RJ, Turpin JM, Nicewander DA: Variation in diabetes care among states: Do patient characteristics matter? Diabetes Care 25: 2230–2237, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lochner KA, Goodman RA, Posner S, Parekh A: Multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries: State-level variations in prevalence, utilization, and cost, 2011. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 3: mmrr.003.03.b02, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nissenson AR, Maddux FW, Velez RL, Mayne TJ, Parks J: Accountable care organizations and ESRD: The time has come. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 724–733, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watnick S, Weiner DE, Shaffer R, Inrig J, Moe S, Mehrotra R, Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : Comparing mandated health care reforms: The Affordable Care Act, accountable care organizations, and the Medicare ESRD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1535–1543, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill SC, Abdus S, Hudson JL, Selden TM: Adults in the income range for the Affordable Care Act’s medicaid expansion are healthier than pre-ACA enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood) 33: 691–699, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barcellos SH, Wuppermann AC, Carman KG, Bauhoff S, McFadden DL, Kapteyn A, Winter JK, Goldman D: Preparedness of Americans for the Affordable Care Act. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 5497–5502, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Adler S, Norris K: Racial differences in mortality among those with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1403–1410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan G, Norris KC, Greene T, Yu AJ, Ma JZ, Yu W, Cheung AK: Race/ethnicity, age, and risk of hospital admission and length of stay during the first year of maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1402–1409, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan G, Norris KC, Yu AJ, Ma JZ, Greene T, Yu W, Cheung AK: The relationship of age, race, and ethnicity with survival in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 953–961, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Lessler J, Hall EC, James N, Massie AB, Montgomery RA, Segev DL: Association of race and age with survival among patients undergoing dialysis. JAMA 306: 620–626, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL: Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 351: 575–584, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JP, Desai M, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC: Validation of reported predialysis nephrology care of older patients initiating dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1078–1085, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Census Bureau: Census Regions and Divisions of the United States, 2011. Available at http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2011

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.