Abstract

Background

Tumor interstitial fluid (TIF) rather than plasma should be used in cancer biomarker discovery because of the anticipated higher concentration of locally produced proteins in the tumor microenvironment. Nevertheless, the actual TIF-to-plasma gradient of tumor specific proteins has not been quantified. We present the proof-of-concept for the quantification of the postulated gradient between TIF and plasma.

Methods

TIF was collected by centrifugation from serous (n = 19), endometrioid (n = 9) and clear cell (n = 3) ovarian carcinomas with early (n = 15) and late stage (n = 16) disease in grades 1 (n = 2), 2 (n = 8) and 3 (n = 17), and ELISA was used for the determination of CA-125, osteopontin and VEGF-A.

Results

All three markers were significantly up-regulated in TIF compared with plasma (p < 0.0001). The TIF-to-plasma ratio of the ovarian cancer biomarker CA-125 ranged from 1.4 to 24,300 (median = 194) and was inversely correlated to stage (p = 0.0006). The cancer related osteopontin and VEGF-A had TIF-to-plasma ratios ranging from 1 to 62 (median = 15) and 2 to 1040 (median = 59), respectively. The ratios were not affected by tumor stage, indicative of more widespread protein expression.

Conclusion

We present absolute quantitative data on the TIF-to-plasma gradient of selected proteins in the tumor microenvironment, and demonstrate a substantial and stage dependent gradient for CA-125 between TIF and plasma, suggesting a relation between total tumor burden and tissue-to-plasma gradient.

General significance

We present novel quantitative data on biomarker concentration in the tumor microenvironment, and a new strategy for biomarker selection, applicable in future biomarker studies.

Abbreviations: CA-125, cancer antigen 125; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; TIF, tumor interstitial fluid

Keywords: CA-125, Biomarker, Ovarian carcinoma, Tumor microenvironment, Tumor interstitial fluid

Highlights

-

•

Quantification of CA-125, VEGF and osteopontin in tumor interstitial fluid (TIF)

-

•

A large TIF-to-plasma gradient was observed for CA-125, the highest in early stage.

-

•

Lower VEGF and osteopontin gradient indicate more widespread protein expression.

1. Introduction

As pathological tissues are perfused by blood and drained by lymph vessels, locally secreted proteins are assumed to enter the circulation, generating disease-specific signatures in the blood [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. It is likely that disease related biomarkers could be found in substantially higher concentrations closer to the source, i.e. in the tumor microenvironment [4], [5]. Although the concentration gradient is hypothesized to be 1000- to 1500-fold [4], the actual gradient between tumor interstitial fluid (TIF) and plasma has to our knowledge not been quantified.

The exact quantification of potential gradients has been hampered by the lack of suitable methods for isolation of undiluted TIF. As recently reviewed in Haslene-Hox et al. [6] and Wiig & Swartz [7], most methods used for TIF isolation, such as capillary ultrafiltration, microdialysis and tissue elution add physiological buffer to extract proteins from the interstitium. Accordingly, TIF will be diluted to an unknown extent, preventing direct comparison of plasma and TIF concentrations.

The cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) is a high molecular weight cell membrane glycoprotein, with a molecular weight > 500 kDa [8], [9] expressed by a variety of epithelial cells. It was introduced as the first serum tumor marker test for ovarian cancer patients in 1983 [10], [11], [12], [13]. CA-125 is to this date one of the few proteins that is routinely used as a biomarker of cancer in the clinic and the reference standard for validation of new biomarker candidates [14]. This protein is thought to originate from the tumor tissue and a serum concentration > 35 U/ml is considered pathological. The presence of CA-125 in ovarian tumor tissue has earlier been determined mainly in a semi-quantitative manner by immunohistochemistry [15]. CA-125 concentration in blood can also be used to monitor recurrent disease in ovarian cancer patients [16].

We also wanted to extend the quantification in TIF to include additional proteins, and chose two proteins highly related to cancer in general, that were likely to be produced in the tumor. VEGF-A, which is central for angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the body, and especially in cancer [17], and osteopontin, which [18] has been shown to have a role in many steps of cancer development and is up-regulated in many cancers [19]. Osteopontin has also been suggested as a biomarker for ovarian cancer [18], [20] as well as renal cell [21], gastric and liver carcinomas [22].

Utilizing the centrifugation technique developed by Wiig et al. [23], [24] to isolate native, undiluted TIF, we could determine the gradient of tissue specific proteins from TIF to plasma. In this manner we could demonstrate that the local production of the established ovarian cancer biomarker CA-125 resulted in several orders of magnitude higher concentration in the tumor interstitium than in the plasma at early stage disease. This is in contrast to the two smaller proteins osteopontin and VEGF-A, known to be cancer specific and to be induced in several pathological conditions [17], [19], that do not show any stage-related correlation in the present cohort.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

The research protocol has been approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (Protocol # 961478-2), Norwegian Social Sciences Data Services (Protocol # 15501) and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK-Vest, Protocol ID REKIII nr. 052.01). All samples were collected after obtaining the patients' written informed consent. The work conformed to the standards set by the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Collection of blood, ascites and TIF samples

Blood samples were collected from the patients 1–2 days before surgery and EDTA was added as the anticoagulation agent prior to the isolation of plasma by centrifugation. Ascites and tumor samples were collected during surgery from patients operated for epithelial ovarian cancer tumors at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Haukeland University Hospital. Ascites were collected in centrifuge tubes, centrifuged at 3220 g for 20 min and the supernatant was extracted and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Tumor samples were taken from the surface of the primary tumors, in an area without any apparent necrosis or inflammation. The surface region was selected for sampling, as this has been shown to result in a lower contribution from intracellular fluid to the isolated TIF [23]. Tumor samples (0.2–0.5 g) for biobank storage were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and transferred for storage at − 80 °C. Tumor samples for TIF analysis were placed on ice and transported to the laboratory. TIF was isolated from the fresh tissue (tissue weight mean = 0.32 ± 0.02 g, range 0.13–0.53 g) approximately 60 min after extirpation by centrifugation through a mesh-filter at 106 g for 10 min [23], [24] and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Samples larger than 0.5 g were cut in multiple samples which were centrifuged in parallel. The isolated fluid has earlier been validated as representative for interstitial fluid [24]. Selected samples were taken from the biobank and thawed and subsequently centrifuged as explained above (samples indicated by a in Table 1). Two samples were used as references with fluid isolated both from fresh and biobank tissue.

Table 1.

Patient data with histological subtype, FIGO stage, grade, CA-125 concentrations in tumor interstitial fluid (TIF), ascites and plasma and VEGF-A and osteopontin concentrations (duplicate measurements shown separately) in TIF and plasma.

| Patient no. | Subtype | Stage | Grade | CA-125 |

VEGF-A |

Osteopontin |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIF | Ascites | Plasma | TIF | Plasma | TIF | Plasma | ||||||||

| 1 | CC | IA | 3 | 36,620 | 41.2 | 122 | 114 | 2.08 | 1.90 | 191 | 178 | |||

| 2a | END | IA | 1 | 627,800 | 435 | 141 | 150 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 220 | 212 | 97.6 | 97.5 | |

| 3a | END | IA | 2 | 7670 | 165 | 278 | 273 | 3890 | 4236 | |||||

| 4a | END | IA | 2 | 2300 | 29.6 | 151 | 136 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 843 | 653 | 211 | 238 | |

| 5a | END | IA | 2 | 2700 | 33.2 | 1012 | 1035 | 3.07 | 2.55 | 390 | 376 | 143 | 155 | |

| 6 | SERb | IA | 2 | 2,823,450 | 116 | 36.8 | 34.1 | 0.87 | 1.07 | 3424 | 3571 | 80.3 | 83.0 | |

| 7a | SER | IA | 3 | 132,500 | 59.6 | 530 | 514 | 2.97 | 2.91 | 5306 | 5658 | 97.9 | 101 | |

| 8a | END | IC | 2 | 348,400 | 30.8 | 177 | 167 | 2.15 | 2.07 | 1633 | 2100 | 188 | 180 | |

| 9a | END | IC | 2 | 1,853,000 | 334 | 25.2 | 28.9 | 2.45 | 2.63 | 363 | 388 | 56.5 | 54.2 | |

| 10a | END | IC | 2 | 365,800 | 524 | 5.74 | 4.61 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 629 | 487 | 88.0 | 110 | |

| 11a | END | IC | 3 | 370,900 | 562 | 219 | 227 | 2.05 | 2.22 | 4981 | 5233 | 179 | 181 | |

| 12a | SER | IC | 1 | 925,300 | 242 | 156 | 186 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 1540 | 1507 | 123 | 132 | |

| 13a | SER | IC | 3 | 240,100 | 1239 | 48.0 | 51.4 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 2790 | 1883 | 183 | 188 | |

| 14 | CC | IIA | na | 130,400 | 442 | 142 | 144 | 2.51 | 2.37 | 4178 | 4526 | 371 | 384 | |

| 15 | SER | IIB | 3 | 389,400 | 74.8 | 148 | 130 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 107 | 118 | |||

| 16 | END | IIIB | 3 | 31,395 | 1814 | 375 | 426 | 435 | 2.48 | 2.31 | 1327 | 1401 | 83.2 | 89.2 |

| 17 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 191,800 | 1066 | 413 | 38.6 | 39.2 | 1.92 | 2.31 | 2119 | 2164 | 109 | 116 |

| 18 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 3260 | 1650 | 596 | 6.39 | 4.75 | 3.02 | 2.94 | 194 | 214 | 268 | 273 |

| 19 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 49,280 | 3066 | 213 | 211 | 1.77 | 1.60 | 6825 | 7258 | 344 | 350 | |

| 20 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 125,200 | 1102 | 41.7 | 48.2 | 1.06 | 0.90 | 5266 | 5422 | 193 | 214 | |

| 21 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 5810 | 1937 | 187 | 228 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 6690 | 6597 | 350 | 351 | |

| 22 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 76,370 | 58.8 | 2.71 | 3.95 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 70.9 | 81.2 | 142 | 149 | |

| 23 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 610 | 427 | 197 | 193 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 5678 | 5236 | 146 | 140 | |

| 24 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 174,400 | 85.2 | 68.5 | 56.3 | 1.96 | 1.92 | 1859 | 2114 | 227 | 238 | |

| 25 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 8960 | 139.2 | 158 | 138 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 5315 | 5038 | 87.2 | 79.6 | |

| 26 | SER | IIIC | 3 | 173,800 | 2280 | 31.4 | 31.1 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 2578 | 2534 | 191 | 155 | |

| 27 | SER | IIIC | na | 12,700 | 136 | 34.1 | 35.4 | 3.84 | 4.06 | 1411 | 1321 | 191 | 173 | |

| 28 | CC | IV | na | 5290 | 222 | 70.2 | 60.1 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 7411 | 6406 | 270 | 290 | |

| 29 | SER | IV | 2 | 2480 | 93.0 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 3.64 | 3.58 | 994 | 937 | 400 | 408 | |

| 30 | SER | IV | 3 | 71,560 | 603 | 505 | 47.8 | 44.0 | 2.06 | 1.84 | 1149 | 1241 | 389 | 429 |

| 31 | SER | IV | na | 461,400 | 1466 | 123 | 125 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 5641 | 5570 | 170 | 194 | |

| Across all samples investigated | ||||||||||||||

| Median | 125,200 | 1358 | 334 | 124 | 1.70 | 2141 | 181 | |||||||

| Minimum | 610 | 603 | 29.6 | 3.33 | 0.13 | 76.1 | 55.3 | |||||||

| Maximum | 2,823,450 | 1814 | 3066 | 1023 | 3.95 | 7042 | 409 | |||||||

SER: serous adenocarcinoma, CC: clear cell adenocarcinoma, END: endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Biobank samples.

Areas of tumor with borderline serous histology.

2.3. Tissue elution

One sample (Patient no. 14, Table 1) with ample amounts of tumor tissue was cut in two. One half was used for the isolation of TIF as described above, and the other was eluted as described by Celis et al. [24], [25]. In brief, 0.31 g of tumor sample was washed in PBS, cut into small pieces of approximately 1–3 mm3 and incubated at 37 °C in a pre-weighed 15 ml conical plastic tube containing 1 ml PBS with 0.128 TIU aprotinin to inhibit proteolysis. After 1 h, 350 μl of eluate was extracted (E1). The remaining buffer and tumor sample was further incubated overnight and the supernatant was extracted (E24). Both eluate samples were centrifuged immediately after extraction at 4622 g for 20 min, and supernatants were frozen at − 20 °C for later analysis.

2.4. ELISA analysis

Before CA-125 analysis, samples were diluted in 50 mg/ml bovine serum albumin to maintain a similar matrix for all sample types. Plasma and ascites were diluted 1:2, TIF 1:100 and eluates 1:20 (E1) and 1:34 (E24) to match the protein mass in plasma, to a total volume of 400 μl for all samples. CA-125 concentration was measured with the Elecsys CA 125 II tumor marker assay (Catalogue number 11776223 322, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Osteopontin was quantified in plasma and TIF with an osteopontin human ELISA kit (Cat. no. ab100618, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Plasma was diluted 1:100 and TIF was diluted 1:1000 in buffer A and run in duplicate. Briefly, samples and standards were added to the coated 96-well plate and gently rotated overnight at 4 °C. The plate was washed four times with washing solution, and incubated with biotinylated osteopontin detection antibody for 1 h. Subsequently, the plate was washed and incubated for an additional 45 min with HRP–streptavidin solution. The washing step was repeated, and One-Step reagent solution was added and the plate was incubated in the dark for 30 min. Finally, the stopping solution was added and the optical density was read spectrophotometrically at 450 nm.

VEGF-A was quantified in plasma and TIF with a VEGF-A human ELISA kit (Cat. no. ab100662, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), following the manufacturer's recommendations, and as briefly summarized for osteopontin. Plasma was diluted 1:10 and TIF was diluted 1:100 in buffer A and run in duplicate.

2.5. Data and statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (Software version 6.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant when not stated otherwise. Values are given as mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test was used to compare paired TIF and plasma concentrations, and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test to compare concentrations in early and advanced stage patients. To evaluate whether the values were changing with stage, linear regression for concentrations and linear regression on log-transformed values for ratios were performed.

3. Results

Selected proteins were measured in matched TIF and plasma from 31 patients. All patients had either serous (n = 19), endometrioid (n = 9) or clear cell (n = 3) tumors. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage of disease ranged from IA to IV, with an even number of samples from patients with advanced (n = 16) and early stage (n = 15) disease (Table 1). The grades ranged from high to low differentiation, with the majority of samples having low differentiation (grade 3, n = 18, Table 1). Ascites was investigated when available (n = 4). Histological data are given in Table 1. Having limited access to fresh early stage tumors we isolated fluid from frozen and thawed tumor samples for 11 early stage tumors. To assess the influence of freezing and thus release of intracellular content to TIF on the quantification of the selected proteins, two samples, where fluid from both fresh and frozen tissue was available, were analyzed in parallel.

3.1. CA-125

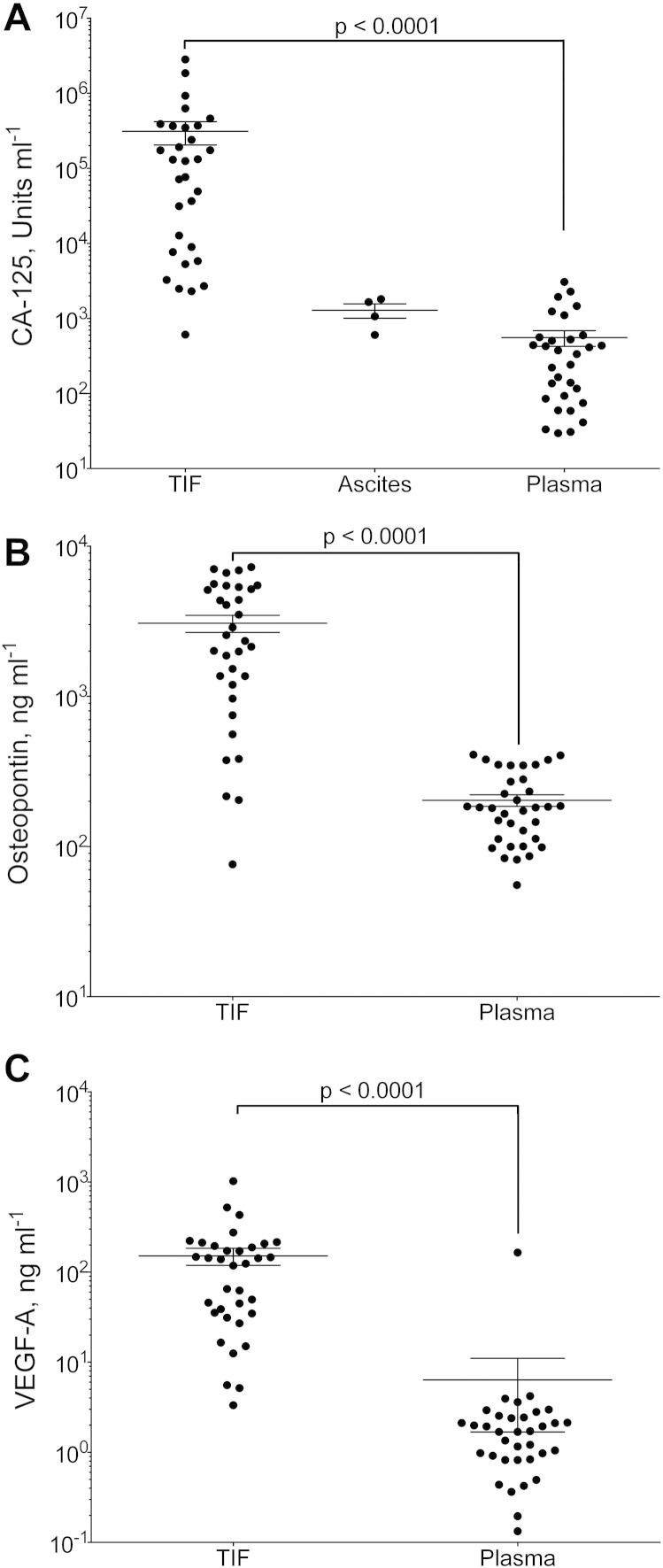

CA-125 is the reference biomarker for ovarian cancer. The majority of CA-125-measurements in plasma, ranging from 30 to 3066 U/ml with a median of 334 U/ml (Fig. 1A), exceeded the clinical threshold of 35 U/ml, while three samples had borderline concentrations (30, 31 and 33 U/ml). Ascites CA-125-levels were between 1.2- and 4-fold that of plasma, with a median value of 1358 U/ml not different from the paired plasma samples (Fig. 1A). In TIF, the concentration ranged from 610 to 2,823,450 U/ml with a median of 125,200 U/ml (Fig. 1A). When comparing samples isolated from frozen and thawed tissue, the concentration of CA-125 was increased 1.6 (sample 20) and 3.2 fold (sample 22) relative to TIF isolated from fresh samples. Moreover, there was a significantly higher concentration in TIF in stages I and II compared to III and IV (p = 0.019), whereas this relationship was opposite, and borderline significant in plasma (p = 0.06). Linear regression showed that CA-125 concentration decreased significantly in TIF (p = 0.03), and increased in plasma with borderline significance (p = 0.053) with increasing FIGO-stage (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

CA-125, VEGF-A and osteopontin in tumor interstitial fluid (TIF), ascites and plasma.

Concentration of A) CA-125 (Units ml− 1); B) VEGF-A (ng ml− 1); and C) osteopontin (ng ml− 1) in TIF, ascites (for CA-125) and plasma from patients with epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Values are for individual tumors and also show mean ± SEM. ***: p = 0.0001 (Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test).

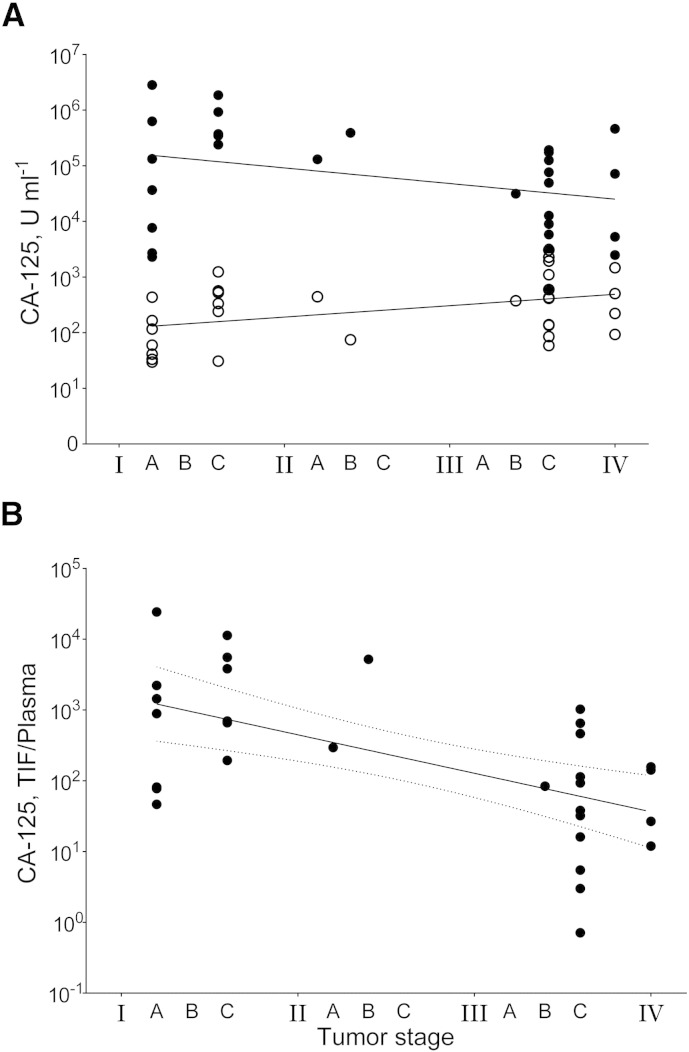

Fig. 2.

CA-125 concentration related to tumor stage.

A) CA-125 concentration (units ml− 1) in tumor interstitial fluid (TIF, ●) and in plasma (○) according to FIGO tumor stage. Linear regressions (solid lines) for TIF: y = − 203,892x + 848,009, R2 = 0.15 and plasma: y = 224.3x − 34.46, R2 = 0.12, slopes being different from zero for TIF (p = 0.03) and borderline significant for plasma (p = 0.053).

B) Ratio of CA-125 concentration in TIF and plasma in individual tumors according to FIGO tumor stage. Exponential regression (solid line): y = 4482e− 1.12x, R2 = 0.29, with 95% confidence interval (dashed lines), slope significantly different from zero (p = 0.0006).

As might be expected in a situation with local production, the TIF CA-125-concentration was significantly higher than in the corresponding plasma samples (p < 0.0001), with a 1.4- to 24,256-fold increase (median = 194). The mean TIF-to-plasma ratio was 1985, comparable with the 1000–1500-fold gradient predicted by Ahn et al. [4], [5], confirming that there is a substantial up-concentration of the locally produced CA-125 in TIF compared with plasma, including in early stage disease. The TIF-to-plasma ratios correlated strongly to stage (p = 0.0006, y = 4482e− 1.12x, R2 = 0.29, Fig. 2B).

3.2. VEGF-A

VEGF-A is an angiogenesis promoter with a central role in tumor development, and thus of interest to quantify in TIF. The concentration of VEGF-A in plasma ranged from 0.13 to 3.9 ng/ml, with a median of 1.7 ng/ml (Fig. 1B). TIF had significantly increased levels of VEGF-A (p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test), ranging from 3.3 to 1023 ng/ml, with a median concentration of 124 ng/ml (Fig. 1B). The TIF-to-plasma ratio of VEGF was smaller than for CA-125, ranging from 1.9 to 1040, and was not related to the stage of disease (data not shown). The concentrations of VEGF-A in TIF isolated from fresh and frozen tissue were highly similar, with a tissue sample from frozen tissue containing 91 and 102% of the VEGF-A concentration in TIF, suggesting that the tumor cells are not a major source of VEGF-A.

3.3. Osteopontin

Osteopontin has earlier been suggested as a biomarker for ovarian cancer [18], [20]. The concentrations ranged from 55 to 409 ng/ml (median = 181 ng/ml) in plasma (Fig. 1C), whereas in TIF, osteopontin levels ranged from 76 to 7042 ng/ml (median = 2141 ng/ml, Fig. 1C), significantly increased compared with plasma (p < 0.0001, Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test). The TIF-to-plasma concentration gradient ranged from 0.5 to 62, with a median of 12, and was not related to stage (data not shown).

3.4. Tissue elution

We measured the CA-125 in eluate after 1 and 24 h to 6164 and 10,837 U/ml respectively, with the corresponding TIF of 130,400 U/ml (Patient no. 14, Table 1). To be able to estimate the concentration of CA-125 in TIF after elution in PBS, we assumed that all CA-125 present in eluate originated from the extracellular compartment of the tumor, being ~ 50% of tumor wet weight [7]. Using this approach, the undiluted extracellular CA-125 concentration was calculated at 45,522 and 67,955 U/ml for E1 and E24 respectively. The increase in CA-125 after 24 h compared with 1 h indicates that CA-125 may not have been completely eluted from the tissue after 1 h, although the extended time of elution may result in increased proteolytic cleavage of membrane bound CA-125 that is released to the elution buffer.

4. Discussion

Here we have determined the magnitude of a previously assumed TIF-to-plasma gradient, central for proximal fluid biomarker discovery. We have quantified the concentration gradient of three proteins relevant for ovarian cancer, CA-125, osteopontin and VEGF-A, and demonstrate a substantial CA-125 concentration even in early stage tumors, with a TIF-to-plasma ratio strongly correlated to stage.

4.1. CA-125

The origin of the fluid sample isolated from human ovarian carcinomas has earlier been verified to be representative for tumor interstitial fluid [24] when isolated from fresh samples. However, due to a low number of early stage fresh samples available, frozen biobank material was also used. Previously we have shown that samples that have been frozen and thawed have a contribution of approximately 20% intracellular fluid to the isolated sample [24]. Comparing parts from the same tumor samples that were either processed fresh or after freezing demonstrated a CA-125-concentration 1.6 to 3.2 times higher in the latter case. Although two samples are not enough for statistical analysis, these findings can indicate a substantial intracellular concentration of CA-125 that is added to the isolated fluid consistent with local production of CA-125 in the tissue. Calculations based on values obtained from frozen biobank samples may thus overestimate CA-125-concentration. To control whether an overestimation of these values affects the statistical analysis, calculations were repeated with the measured CA-125 concentrations multiplied by the two frozen samples' average increase of 2.4. Both with and without this correction the main conclusions remained unchanged.

In tissue arrays performed on 382 ovarian tumors with matched serum samples, Høgdall et al. [15] found that expression of CA-125 in tissue, but not serum, had prognostic value. Although moderate, we found that CA-125-concentrations in TIF decreased in advanced stage disease. The decrease in TIF CA-125-concentration in advanced stage disease may result from a more heterogeneous tumor cell population as the tumor grows and contributions to TIF from stromal cells.

We found a substantial TIF-to-plasma ratio that correlated strongly with stage, yet decreasing in advanced stage tumors. A likely explanation is that during tumor growth, the amount of CA-125 secreted to plasma will increase provided that there is a similar interstitial concentration of CA-125 and there is no increase in clearance from plasma. As the tumor volume increases, CA-125 can be released from a larger fluid compartment into the unchanged circulating blood volume. The net result will be a reduced TIF-to-plasma ratio as the tumor grows and a higher TIF-to-plasma ratio when the total tumor burden is low. Since there is a parallel increase in cell mass and interstitial volume during tumor growth, the concentration of CA-125 in plasma is most likely mainly decided by tumor mass, in agreement with the present observation (Fig. 2).

It should be noted, though, that the total tumor burden in advanced stage disease will also depend on metastases that may or may not produce CA-125. These metastases will contribute to the protein concentration in plasma, but not in TIF from the primary tumor site.

When considering change in CA-125 concentrations related to stage, it is important to note that the endometrioid and serous subtypes of ovarian cancer is differently represented in the early- and advanced-stage groups, with endometrioid tumors predominantly present at earlier stages. Recently, a classification of ovarian cancer in two types has been suggested; type I representing slow-growing cancers with good prognosis, such as low-grade serous, low-grade endometrioid, clear cell and mucinous tumors, and type II being more aggressive, including high-grade serous, high-grade endometrioid and undifferentiated tumors [26]. It has also been demonstrated by Köbel et al. [27] that a number of biomarkers have different levels in plasma between subtypes but not necessarily between disease stages within each subtype. Thus, care should be taken when considering the change in protein concentrations according to stage in a cohort including multiple subtypes. However, the levels of CA-125 were practically similar in serous compared with both clear cell and endometrioid subtypes [27]. Our cohort also includes high-grade tumors that may be classified as type II in the lower stages. CA-125 concentrations will likely reflect disease development rather than being subtype-specific, but care should be taken when extrapolating to other biomarkers.

4.2. VEGF-A

The angiogenesis related protein VEGF-A had lower TIF-to-plasma gradients compared with CA-125 (Fig. 1B). The concentrations of VEGF-A in TIF isolated from fresh and frozen tissue were practically similar, with a tissue sample from frozen tissue containing 91 and 102% of the VEGF-A concentration in TIF. Even though there were two observations only, these findings suggest that the rupture of tumor cells does not change the concentration of VEGF-A in the isolated fluid, and that VEGF-A enters the tumor microenvironment both from tumor cells and the circulation.

The quantification of VEGF-A in TIF can be used in the modeling of tumor biology [28], where such quantitative data is lacking. The measured TIF concentration of VEGF-A (3.3–1023 ng/ml) is higher than the value estimated by Finley et al. of 1125 pg/ml [28], but within the range found in tumor extracts (5.5 to 7600 ng/ml, Supplementary Table 1 in [28]).

Intratumoral VEGF-A in tumor fluid isolated by microdialysis has previously been reported to 6 pg/ml (n = 10) with similar concentrations measured in plasma (3.67 pg/ml) [29]. The substantially lower measured concentration in dialysate compared to our measurements is likely due to the sieving effect and low recovery of proteins in microdialysis [6], [7].

4.3. Osteopontin

Osteopontin is a small integrin-binding glycophosphoprotein secreted by a variety of cell types, including osteoclasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and activated immune cells, and can act as a modulator of cell adhesion as well as an autocrine and paracrine factor by interaction with e.g. integrins [19], [22]. When measuring osteopontin in frozen and thawed tissue we found concentrations 29% and 43% of the values measured in fresh TIF. Thus, fluid not containing osteopontin was admixed into the isolated fluid when using frozen tissue, indicating that the concentration of osteopontin is low in these two tumors. The decrease in osteopontin concentration after one freeze/thaw cycle could be restricted to the two samples tested in both conditions, but as these two samples showed two of the highest concentrations for osteopontin in both TIF and plasma it is unlikely that they originated from osteopontin-negative patients. The two patients may however have osteopontin-producing metastases that contribute to a high plasma concentration, with the primary tumor producing small amounts of the protein.

The osteopontin TIF-to-plasma ratios were substantially lower than the corresponding ratios for both VEGF-A and CA-125. Our findings may indicate systemic production of osteopontin rather than local, and the tumor is supplied with osteopontin mainly from the blood stream. Another explanation for the low ratios compared with CA-125 and VEGF can be that osteopontin has a short half-life in the tumor environment, resulting in a fast breakdown, and low steady-state concentrations of the protein. This may question the value of osteopontin as a specific ovarian cancer biomarker [18], [20]. Nevertheless, the ratio between TIF and plasma is high for several patients and can indicate that osteopontin may accumulate in the tumor microenvironment.

For a definite conclusion to be drawn about the relation between both osteopontin and VEGF-A with stage, a larger patient cohort, including documentation of tumor burden and residual disease is needed.

4.4. Tissue elution

Tissue elution is a widely utilized technique for TIF isolation [25] that does not give an absolute concentration of the substance of interest in TIF because of dilution with PBS [25]. Furthermore, the extracellular CA-125 concentration estimated from eluate was lower than that measured in TIF extracted by centrifugation. The explanation is probably that CA-125 cannot distribute in the total extracellular fluid volume due to volume exclusion [30], [31] as earlier demonstrated for proteins such as albumin that can distribute in approximately 50% of the interstitial fluid in tumors [30 and unpublished results]. Incomplete equilibration with buffer as well as volume exclusion will result in the underestimation of the CA-125 concentration in TIF based on elution data. If we, however, take these considerations into account, and assume that CA-125 can distribute in a volume similar to albumin, the concentration of CA-125 estimated by tissue elution at both time points approach the concentration measured in TIF isolated by centrifugation. By calculating the total extracellular volume of the ovarian tumors and the available distribution volume of similar sized plasma proteins, the correct concentration of CA-125, or other proteins may be calculated from eluate data [32].

Sedlaczek et al. [33] investigated CA-125 in cyst fluid from ovarian tumors, ascites and plasma. Cyst fluid differs from TIF because it originates from a sequestered space not in direct contact with the circulation, whereas TIF originates from filtered fluid and is returned to the blood circulation by lymph having percolated tumor and stromal cells. Sedlaczek and co-workers found median levels of CA-125 in serum from serous and endometrioid carcinomas of 696 and 661 U/ml respectively; somewhat higher, but within the same range as our data. The range of CA-125 was smaller in cyst fluid than in TIF, mainly because of one patient in our set who had an extremely high CA-125-level in TIF (2.82 ⋅ 106 U/ml), and the median values (44,850 and 32,150 U/ml in cyst fluid from serous and endometrioid tumors, respectively) were lower than our measured levels of CA-125 in TIF (125,200 U/ml), suggesting that cyst fluid may have a protein composition slightly lower than TIF.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge our results represent the first successful efforts to quantify the concentration gradient between tumor microenvironment and plasma in human samples. Our method to quantify this gradient may significantly contribute to the applicability of proximal fluids and TIF for biomarker discovery. The determination of the locally produced biomarker CA-125 in TIF compared with plasma exemplifies the advantage of using TIF as a source for biomarker and therapeutic target discoveries. Proteins locally produced in the tumor will have dramatically elevated concentrations in TIF compared with plasma, more so in early stages, and the likelihood of finding tumor-specific proteins can be increased in such samples. On the other hand, the demonstration of lower ratios for VEGF-A and osteopontin suggests a less tumor-specific production. These proteins are elevated in plasma from ovarian cancer patients [17], [19], as they are for many other cancers, and are thus likely primarily coupled to the systemic response to cancer and only secondarily to the tumor microenvironment.

The use of TIF-to-plasma ratios as a tool to assess the suitability of novel biomarkers may assist in the validation and translation of novel biomarkers for ovarian as well as other cancers, and should be further explored.

Conflicts of interest

The authors' declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Britt Edvardsen and the research lab at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics for invaluable assistance with the collection of sample material. Financial support from The National Program for Research in Functional Genomics (FUGE) and Olav Raagholt and Gerd Meidel Raagholt's Foundation for Research is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Hanash S.M., Pitteri S.J., Faca V.M. Mining the plasma proteome for cancer biomarkers. Nature. 2008;452:571–579. doi: 10.1038/nature06916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liotta L.A., Ferrari M., Petricoin E. Clinical proteomics: written in blood. Nature. 2003;425:905. doi: 10.1038/425905a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanash S., Taguchi A. The grand challenge to decipher the cancer proteome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2010;10:652–660. doi: 10.1038/nrc2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn S.M., Simpson R.J. Body fluid proteomics: prospects for biomarker discovery. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2007;1:1004–1015. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson R.J., Bernhard O.K., Greening D.W., Moritz R.L. Proteomics-driven cancer biomarker discovery: looking to the future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haslene-Hox H., Tenstad O., Wiig H. Interstitial fluid—a reflection of the tumor cell microenvironment and secretome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1834(11):2336–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiig H., Swartz M.A. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 2012;92:1005–1060. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiland F., Martin K., Oehler M.K., Hoffmann P. Deciphering the molecular nature of ovarian cancer biomarker CA125. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:10568–10582. doi: 10.3390/ijms130810568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiland F., Fritz K., Oehler M.K., Hoffmann P. Methods for identification of CA125 from ovarian cancer ascites by high resolution mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:9942–9958. doi: 10.3390/ijms13089942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bast R.C., Jr., Klug T.L., St John E., Jenison E., Niloff J.M. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309:883–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310133091503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fritsche H.A., Bast R.C. CA 125 in ovarian cancer: advances and controversy. Clin. Chem. 1998;44:1379–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs I., Bast R.C., Jr. The CA 125 tumour-associated antigen: a review of the literature. Hum. Reprod. 1989;4:1–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholler N., Urban N. CA125 in ovarian cancer. Biomark. Med. 2007;1:513–523. doi: 10.2217/17520363.1.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menon U., Gentry-Maharaj A., Hallett R., Ryan A., Burnell M. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Høgdall E.V., Christensen L., Kjaer S.K., Blaakaer J., Kjaerbye-Thygesen A. CA125 expression pattern, prognosis and correlation with serum CA125 in ovarian tumor patients. From the Danish “MALOVA” Ovarian Cancer Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007;104:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bast R.C., Jr. CA 125 and the detection of recurrent ovarian cancer: a reasonably accurate biomarker for a difficult disease. Cancer. 2010;116:2850–2853. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neufeld G., Cohen T., Gengrinovitch S., Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visintin I., Feng Z., Longton G., Ward D.C., Alvero A.B. Diagnostic markers for early detection of ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:1065–1072. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellahcene A., Castronovo V., Ogbureke K.U.E., Fisher L.W., Fedarko N.S. Small integrin-binding ligand N-linked glycoproteins (SIBLINGs): multifunctional proteins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:212–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J.H., Skates S.J., Uede T., Wong K.K., Schorge J.O. Osteopontin as a potential diagnostic biomarker for ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2002;287:1671–1679. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun M., Shariat S.F., Cheng C., Ficarra V., Murai M. Prognostic factors and predictive models in renal cell carcinoma: a contemporary review. Eur. Urol. 2011;60:644–661. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao D.X., Li Z.J., Jiang X.O., Lum Y.L., Khin E. Osteopontin as potential biomarker and therapeutic target in gastric and liver cancers. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3923–3930. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i30.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiig H., Aukland K., Tenstad O. Isolation of interstitial fluid from rat mammary tumors by a centrifugation method. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H416–H424. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00327.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haslene-Hox H., Oveland E., Berg K.C., Kolmannskog O., Woie K. A new method for isolation of interstitial fluid from human solid tumors applied to proteomic analysis of ovarian carcinoma tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Celis J.E., Gromov P., Cabezon T., Moreira J.M., Ambartsumian N. Proteomic characterization of the interstitial fluid perfusing the breast tumor microenvironment: a novel resource for biomarker and therapeutic target discovery. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:327–344. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentry-Maharaj A., Menon U. Screening for ovarian cancer in the general population. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;26:243–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Köbel M., Kalloger S.E., Boyd N., McKinney S., Mehl E. Ovarian carcinoma subtypes are different diseases: implications for biomarker studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finley S.D., Popel A.S. Effect of tumor microenvironment on tumor VEGF during anti-VEGF treatment: systems biology predictions. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):802–811. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garvin S., Dabrosin C. In vivo measurement of tumor estradiol and vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiig H., Gyenge C.C., Tenstad O. The interstitial distribution of macromolecules in rat tumours is influenced by the negatively charged matrix components. J. Physiol. 2005;567:557–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oien A.H., Justad S.R., Tenstad O., Wiig H. Effects of hydration on steric and electric charge-induced interstitial volume exclusion—a model. Biophys. J. 2013;105:1276–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiig H., Gyenge C., Iversen P.O., Gullberg D., Tenstad O. The role of the extracellular matrix in tissue distribution of macromolecules in normal and pathological tissues: potential therapeutic consequences. Microcirculation. 2008;15:283–296. doi: 10.1080/10739680701671105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedlaczek P., Frydecka I., Gabrys M., Van Dalen A., Einarsson R. Comparative analysis of CA125, tissue polypeptide specific antigen, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha levels in sera, cyst, and ascitic fluids from patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1886–1893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]