Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown the individual benefits of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) and intraoperative (i)MRI in enhancing survival for patients with high-grade glioma. In this retrospective study, we compare rates of progression-free and overall survival between patients who underwent surgical resection with the combination of 5-ALA and iMRI and a control group without iMRI.

Methods

In 200 consecutive patients with high-grade gliomas, we recorded age, sex, World Health Organization tumor grade, and pre- and postoperative Karnofsky performance status (good ≥80 and poor <80). A 0.15-Tesla magnet was used for iMRI; all patients operated on with iMRI received 5-ALA. Overall and progression-free survival rates were compared using multivariable regression analysis.

Results

Median overall survival was 13.8 months in the non-iMRI group and 17.9 months in the iMRI group (P = .043). However, on identifying confounding variables (ie, KPS and resection status) in this univariate analysis, we then adjusted for these confounders in multivariate analysis and eliminated this distinction in overall survival (hazard ratio: 1.23, P = .34, 95% CI: 0.81, 1.86). Although 5-ALA enhanced the achievement of gross total resection (odds ratio: 3.19, P = .01, 95% CI: 1.28, 7.93), it offered no effect on overall or progression-free survival when adjusted for resection status.

Conclusions

Gross total resection is the key surgical variable that influences progression and survival in patients with high-grade glioma and more likely when surgical adjuncts, such as iMRI in combination with 5-ALA, are used to enhance resection.

Keywords: 5-aminolevulinic acid, glioblastoma, glioma surgery, intraoperative imaging, intraoperative MRI

Survival of patients with malignant glioma remains dismal, with a 5-year survival of 24% in World Health Organization (WHO) grade III1 and 4% in grade IV tumors.2 To improve outcome, surgical resection of glioma should achieve maximal cytoreduction while preserving function. Intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (iMRI) was introduced more than 15 years ago and assists the surgeon in providing anatomical information during surgery which may differ from the preoperative scan because of the distortion created by dural opening and surgical manipulation (brainshift).3 The most important aspect of iMRI is its ability to reveal residual tumor after an initial resection. Although iMRI in itself is not a therapeutic but a diagnostic tool, it may improve outcome by guiding the surgeon in achieving a higher rate of resection.

Although the positive impact of iMRI on extent of glioma resection has been reported in several series reviewed by Kubben et al,4 only 4 studies directly evaluated its effect on survival. Wirtz et al5 found that iMRI reduced the proportion of patients with residual tumor from 62% to 33% and that gross total resection (GTR) was associated with longer survival; however, the study did not include a control group. In a smaller retrospective matched cohort comparison of 32 patients, use of iMRI had no significant effect on survival.6 A retrospective series demonstrated that iMRI led to a detection of incompletely resected tumors, which in turn increased the rate of GTR.7 In the ensuing prospective trial by Senft' et al,8 iMRI was associated with improved survival compared with a control group operated on without iMRI assistance. Although this study argues strongly in favor of iMRI, the study design dictated that 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) not be used to guide resection. Since the use of 5-ALA as a surgical adjunct is known to improve survival9 and is now a standard of care for high-grade glioma surgery, the next question is whether the combination of 5-ALA and iMRI has an impact on outcome. In the outlook of their prospective randomized study, Senft et al suggested that future studies should focus on assessing the combined effect of 5-ALA and iMRI.8

5-Aminolevulinic acid is a porphyrin that accumulates and generates microscope-detectable fluorescence in neoplastic tissue.9 At our institution, 5-ALA has been used routinely in all glioma surgeries since 2006, and iMRI was introduced shortly thereafter. Due to a restricted availability of intraoperative imaging time slots, iMRI could not be applied to all patients. Since prospective data on a combination of 5-ALA and iMRI are elusive, we undertook this retrospective analysis to compare the effect of the combination of 5-ALA + iMRI with a control group operated on without iMRI.

Materials and Methods

Study Parameters

We retrospectively identified consecutive patients >18 years of age with a histological diagnosis of high-grade glioma who underwent treatment at our institution from 2003 to 2011. We recorded patient age and sex, WHO tumor grade, and pre- and postoperative Karnofsky performance status (KPS), which was defined as a good score of ≥80 and a poor score of <80. Location of the tumor was defined as eloquent in any of the following regions: precentral or postcentral gyrus, calcarine fissure, left frontal operculum, left inferior parietal lobule, left superior temporal gyrus, dentate gyrus, internal capsule, basal ganglia, thalamus, and hypothalamus. According to consensus criteria (Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology), cases where early postoperative MRI (<72 h) showed no residual contrast enhancement were classified as complete resection of detectable disease after review at an interdisciplinary tumor board (referred to for simplicity as GTR).10 Adjuvant therapy was recorded as well. 5-Aminolevulinic acid was administered routinely and used to guide resection.9 Neuronavigation was used to guide resection in all cases.

We defined 2 groups as patients undergoing surgery with 5-ALA + iMRI and the control group, who did not undergo iMRI. No predefined selection criteria were applied in the use of these surgical adjuncts.

Intraoperative MRI

Intraoperative imaging was obtained with the PoleStar N20 (Medtronic Navigation) using a 0.15-Tesla field strength. During the scan, a mobile radiofrequency shield covered the patient and the magnet to minimize field inhomogeneities. Patients were positioned prone or supine or in a modified parkbench position with the head fixed in an MR-compatible 3-pin head holder. After an initial T1-weighted sequence, intravenous contrast agent (0.1 mmol/kg gadolinium-DTPA) was administered and T1-weighted axial sequences with a 2-mm slice thickness were repeated (scan time 11 min).

Overall and Progression-free Survival

Survival was recorded in months and evaluated at regular neuro-oncological follow-up visits. When follow-up was unavailable, we called patients by telephone. The communal population office was contacted to ensure that no patients were deceased in the meantime between follow-ups (last evaluation date: September 20, 2013). Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined according to consensus criteria.10 An increase of 25% of maximal tumor diameter on follow-up MRI, an increased dose of steroids, and death were used as endpoints for PFS.

Statistical Methods

The variable of interest (an independent variable) was the use of iMRI.

The model selection procedure used here was that of forced entry modeling, as distinct from modeling methods such as forward, backward, and stepwise regression. This method has the benefit of reducing multiple testing and erroneous P-values but exposes us to the problem of overfitting.

Descriptive analyses were conducted using methods for categorical data analysis, notably frequencies, proportions, and chi-square tests for imbalances of baseline variables. If a variable was found to be imbalanced, the magnitude of the imbalance was measured using logistic regression.

Descriptive median survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Patients who survived more than 2.5 years were considered long-term survivors; this is the period past which the risk of death is half that experienced during the period of the highest risk of death (12–15 mo).11

Results

This study included a total of 200 patients, 63 (32%) of whom were female. One patient for whom no documentation was available was included (in Table 1) but excluded from further analysis, leaving 199. Mean age was 57 ± 12 years. A total of 387.5 years of follow-up time (4650 mo) was recorded, and over this period, 176 deaths were observed. The long-term survival rate of this cohort was 25% (95% CI: 19%, 31%). GTR was achieved in 132 patients (66%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| No iMRI |

iMRI |

Total |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 46 | 32 | 17 | 31 | 63 | 32 | .912 |

| Male | 99 | 68 | 38 | 69 | 137 | 68 | |

| Age | |||||||

| <50 y | 47 | 32 | 18 | 33 | 65 | 32 | .966 |

| ≥50 y | 98 | 68 | 37 | 67 | 135 | 68 | |

| Preop KPS | |||||||

| Poor (<80) | 39 | 27 | 3 | 5 | 42 | 21 | .001** |

| Good (≥80) | 106 | 73 | 52 | 95 | 158 | 79 | |

| Postop change in KPS | |||||||

| No change | 105 | 72 | 36 | 65 | 141 | 70 | .335 |

| Change | 40 | 28 | 19 | 35 | 59 | 30 | |

| Eloquence | |||||||

| No | 64 | 44 | 26 | 47 | 90 | 45 | .691 |

| Yes | 81 | 56 | 29 | 53 | 110 | 55 | |

| WHO grade | |||||||

| III | 21 | 14 | 13 | 24 | 34 | 17 | .124 |

| IV | 124 | 86 | 42 | 76 | 166 | 83 | |

| Total resection | |||||||

| No | 102 | 70 | 30 | 55 | 132 | 66 | .035* |

| Yes | 43 | 30 | 25 | 45 | 68 | 34 | |

| 5-ALA | |||||||

| No | 87 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 43.5 | <.001** |

| Yes | 58 | 40 | 55 | 100 | 113 | 56.5 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||||

| No | 28 | 19 | 8 | 15 | 36 | 18 | .434 |

| Yes | 117 | 81 | 47 | 85 | 164 | 82 | |

| Total | 145 | 100 | 55 | 100 | 200 | 100 | |

Important imbalances were noted across the iMRI groups. Proportionately more patients with good preop KPS status (P = .001) received iMRI; total resection was greater in the iMRI group (P = .035), as was the use of 5-ALA (P < .001).

P < .05.

P < .01.

Comparison of Study Groups

Intraoperative MRI and 5-ALA were used in combination in 55 patients (28%). No iMRI was applied in 145 patients (72%). Sex, age, WHO grade, and eloquence were well matched, with no differences between groups (Table 1). Adjuvant therapies were balanced across the categories of surgery type (Table 1), with 164 patients (82%) having undergone additional therapy after surgery. 5-Aminolevulinic acid was used in 58/145 patients in the non-iMRI group (40%) but in all patients in the iMRI group (P < .001) owing to the inclusion of patients since 2003 prior to initiation of a 5-ALA protocol. Preoperative KPS was more favorable in the iMRI group (good in 52 [95%] vs 106 [73%] in the non-iMRI group; P = .001). Therefore, preoperative KPS was considered to be a potential confounder and was maintained in all regression analyses.

Gross Total Resection

The strongest predictor of GTR was non-eloquent localization of the tumor. Patients who had tumors in non-eloquent locations were 11.8 times as likely to have GTR as patients with tumors in eloquent locations (Table 2). The second predictor of GTR was the use of 5-ALA. However, iMRI was not a predictor of GTR even with adjustment for eloquent location and preoperative KPS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of GTR

| Univariable | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | ||

| Odds ratio | 1.797 | 1.657 |

| P | .08 | .21 |

| Lower CI | 0.925 | 0.751 |

| Upper CI | 3.491 | 3.653 |

| Age >50 y | ||

| Odds ratio | 0.826 | 0.796 |

| P | .55 | .58 |

| Lower CI | 0.445 | 0.353 |

| Upper CI | 1.534 | 1.797 |

| WHO grade IV | ||

| Odds ratio | 0.933 | 0.791 |

| P | .86 | .66 |

| Lower CI | 0.431 | 0.274 |

| Upper CI | 2.023 | 2.281 |

| Good preop KPS | ||

| Odds ratio | 1.373 | 0.588 |

| P | .40 | .29 |

| Lower CI | 0.652 | 0.220 |

| Upper CI | 2.890 | 1.576 |

| Eloquent location | ||

| Odds ratio | 0.085 | 0.082 |

| P | .00** | .00** |

| Lower CI | 0.042 | 0.038 |

| Upper CI | 0.175 | 0.174 |

| Intraoperative MRI | ||

| Odds ratio | 1.977 | 1.360 |

| P | .04* | .51 |

| Lower CI | 1.043 | 0.547 |

| Upper CI | 3.746 | 3.381 |

| 5-ALA | ||

| Odds ratio | 3.042 | 3.188 |

| P | .00** | .01* |

| Lower CI | 1.608 | 1.282 |

| Upper CI | 5.758 | 7.931 |

P < .05.

P < .01.

Effect size measured using univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

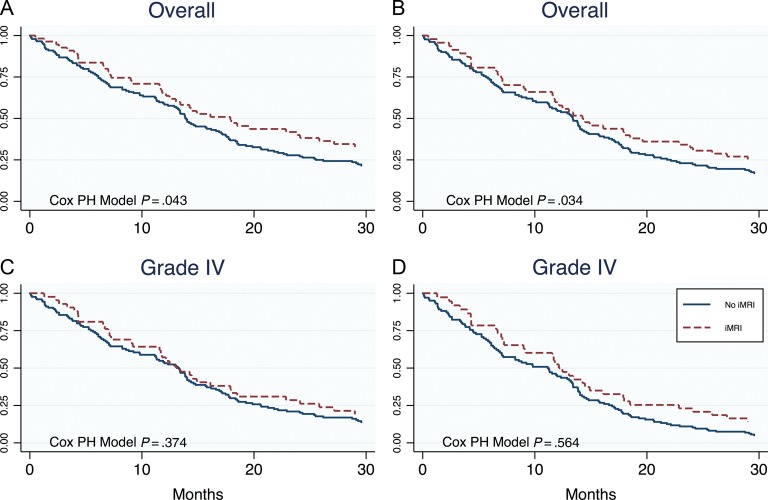

Progression-free Survival and Overall Survival

Median PFS was 7.0 months in the non-iMRI group and 10.6 months in the iMRI group (log-rank P = .19) (Table 3). Median follow-up time in patients who were still alive was 236.7 weeks (59 mo). Once adjusted for multiple covariates, iMRI did not appear to affect PFS between groups (Table 4). Age (>50 y), WHO grade, and extent of resection were the strongest predictors of PFS, with a change in KPS increasing in strength (1.37–1.59) after adjustment (Table 4). Median overall survival (OS) was 13.8 months in the non-iMRI group and 17.9 months in the iMRI group (P = .043) (Fig. 1 and Table 4). On univariable analysis, patients operated on with iMRI were 1.432 times less likely to die than patients operated on without iMRI (Table 4). Of note, good preoperative KPS scores were observed in 95% of patients with iMRI versus 73% without iMRI (Table 1). However, using the multivariable analysis to adjust for these baseline discrepancies in preoperative KPS, we then found that the effect of iMRI on OS was not significant (P = .34) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Descriptors of PFS

| PFS |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time at Risk (mo) | n | Median | PFS Time 1 y | PFS Time 2.5 y | P (log-rank) | HR | 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1146.1 | 62 | 10.39 | 42.2% | 19.4% | .272 | 1.20 | 0.868 | 1.650 |

| Male | 1823.1 | 137 | 7.79 | 36.0% | 15.3% | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| <50 y | 1690.8 | 65 | 18.50 | 57.8% | 32.9% | <.001** | 2.36 | 1.698 | 3.281 |

| ≥50 y | 1278.4 | 134 | 5.64 | 27.6% | 7.9% | ||||

| Preop KPS | |||||||||

| Poor (<80) | 564.8 | 42 | 5.10 | 37.2% | 13.3% | .488 | 0.88 | 0.614 | 1.261 |

| Good (≥80) | 2404.4 | 157 | 9.17 | 38.3% | 17.4% | ||||

| Postop change in KPS | |||||||||

| No change | 2360.9 | 141 | 9.17 | 41.3% | 18.0% | .060 | 1.369 | 0.986 | 1.901 |

| Change | 608.29 | 58 | 4.85 | 29.2% | 12.7% | ||||

| Eloquence | |||||||||

| No | 1459.0 | 90 | 9.78 | 41.9% | 16.2% | .352 | 1.15 | 0.856 | 1.545 |

| Yes | 1510.1 | 109 | 6.89 | 34.7% | 16.8% | ||||

| WHO grade | |||||||||

| III | 1242.6 | 33 | 36.90 | 93.6% | 61.3% | <.001** | 3.76 | 2.421 | 5.841 |

| IV | 1726.6 | 166 | 5.78 | 29.5% | 7.4% | ||||

| Total resection | |||||||||

| No | 1691.7 | 131 | 5.78 | 30.3% | 12.6% | .019* | 1.45 | 1.061 | 1.971 |

| Yes | 1277.5 | 68 | 12.36 | 68.7% | 23.8% | ||||

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||||||

| No | 349.7 | 36 | 3.32 | 37.1% | 17.8% | .085 | 1.49 | 0.95 | 2.15 |

| Yes | 2619.5 | 163 | 9.78 | 41.1% | 16.7% | ||||

| 5-ALA | |||||||||

| No | 1404.3 | 86 | 6.89 | 39% | 17% | .671 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 1.44 |

| Yes | 1565.0 | 113 | 8.86 | 37% | 16% | ||||

| Intraoperative MRI | |||||||||

| No | 2074.5 | 144 | 7.03 | 35.3% | 14.6% | .198 | 0.80 | 0.577 | 1.121 |

| Yes | 894.7 | 55 | 10.64 | 45.0% | 21.5% | ||||

| Total | 2969.21 | 199 | 8.36 | 38% | 17% | ||||

Note that age at surgery, WHO grade, and resection status were all predictors of PFS.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model for PFS and OS outcomes

| PFS |

OS |

OS (WHO grade IV only) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | 95% CI |

HR | P | 95% CI |

HR | P | 95% CI |

||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1.350 | .08 | 0.970 | 1.878 | 1.118 | .50 | 0.807 | 1.549 | 1.04 | .81 | 0.73 | 1.48 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| ≥50 y | 1.882 | <.001** | 1.334 | 2.655 | 1.860 | <.001** | 1.298 | 2.665 | 1.66 | .01 | 1.12 | 2.45 |

| Preop KPS | ||||||||||||

| Poor (<80) | 1.231 | .32 | 0.818 | 1.851 | 0.883 | .53 | 0.599 | 1.302 | 0.85 | .44 | 0.56 | 1.28 |

| Postop KPS | ||||||||||||

| decline† | 1.624 | <.01** | 1.133 | 2.327 | 1.399 | .06 | 0.988 | 1.980 | 1.20 | .33 | 0.82 | 1.75 |

| Eloquence | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.039 | .83 | 0.728 | 1.484 | 1.226 | .28 | 0.850 | 1.768 | 1.14 | .50 | 0.77 | 1.69 |

| WHO grade | ||||||||||||

| IV | 4.676 | <.001** | 2.816 | 7.765 | 6.244 | <.001** | 3.527 | 11.051 | – | – | – | – |

| Total resection | ||||||||||||

| No | 2.264 | <.001** | 1.539 | 3.332 | 2.528 | <.001** | 1.698 | 3.766 | 2.76 | >.001** | 1.81 | 4.23 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.942 | <.001** | 1.254 | 3.008 | 2.763 | <.001** | 1.794 | 4.255 | 4.18 | >.001** | 2.58 | 6.75 |

| 5-ALA | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 1.404 | .09 | 0.953 | 2.069 | 1.057 | .77 | 0.729 | 1.533 | 1.09 | .65 | 0.74 | 1.61 |

| Intraoperative MRI | ||||||||||||

| No | 1.277 | .23 | 0.854 | 1.911 | 1.227 | .34 | 0.809 | 1.859 | 1.13 | .56 | 0.73 | 1.76 |

All predictor variables are binary/dichotomous. Interpretation of the HR: Patients who had a subtotal resection were 2.53 times as likely to die of their brain tumor as patients who had received a GTR. The 4 columns on the right display multivariable outcomes as calculated from WHO grade IV tumors only.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Compared with preop KPS.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier graphs comparing the effect of no iMRI vs iMRI on OS. (A) The effect of iMRI on OS in patients with high-grade glioma just reaches significance on univariate analysis. (B) The effect is significantly reduced once adjusted for resection status in multivariate analysis. Considering only WHO grade IV tumors (graph C for univariate, graph D for multivariate analysis) does not change the overall conclusion that iMRI did not have a direct outcome on survival. PH, proportional hazards.

Eloquence

As expected, subtotal resection was 11.8 times more likely in patients whose tumors occurred in eloquent rather than non-eloquent locations. In addition, eloquent location was not an independent predictor of outcomes, OS or PFS, in univariable or multivariable models.

Intraoperative MRI

In Table 5, although iMRI appears to improve OS (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.432, P = .043, 95% CI: 1.012, 2.027), this finding was likely confounded by several variables. As seen in Table 1, variables showing baseline imbalances included preoperative KPS (P < .001), extent of resection (P = .035), and use of 5-ALA at surgery (P < .001). When compared with non-iMRI patients, more iMRI patients with good KPS had 5-ALA at surgery and achieved GTR. Subsequently, in the multivariable Cox proportional model, the use of iMRI had no significant effect on outcomes (Table 4). From a logical perspective as well as a statistical perspective, we believe that GTR is the variable that most likely confounds the relationship between iMRI and outcome. The main purpose of iMRI is to help the surgeon achieve GTR at surgery. Moreover, when estimating the OS model without GTR as a parameter, the effect size of iMRI increased to an HR of 1.36 (95% CI: 0.90, 2.06; not far from the univariate HR of 1.43), thus indicating that the variable with the largest confounding effect was GTR. A separate analysis of uni- (P = .374) and multivariable (P = .564) effects of iMRI on the subset of WHO grade IV tumors only equally showed no tangible direct effect of iMRI on survival (Fig. 1, Table 4).

Table 5.

Descriptors of OS

| OS |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time at Risk (mo) | n | Median | OS Time 1 y | OS Time 2.5 y | P (log-rank) | HR | 95% CI |

||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1545.3 | 62 | 14.21 | 61.3% | 23.4% | .868 | 1.02 | 0.787 | 1.411 |

| Male | 3104.5 | 137 | 14.25 | 58.1% | 27.4% | ||||

| Age | |||||||||

| <50 y | 2468.3 | 65 | 26.18 | 76.9% | 47.7% | <.001** | 2.52 | 1.787 | 3.558 |

| ≥50 y | 2181.5 | 134 | 12.89 | 52.2% | 13.4% | ||||

| Preop KPS | |||||||||

| Poor (<80) | 1010.0 | 42 | 12.89 | 52.4% | 19.1% | .681 | 1.079 | 0.752 | 1.546 |

| Good (≥80) | 3639.8 | 157 | 14.46 | 62.4% | 26.1% | ||||

| Postop change in KPS | |||||||||

| No change | 3648.5 | 141 | 16.10 | 64.5% | 27.7% | .054 | 1.37 | 0.994 | 1.905 |

| Change | 1001.3 | 58 | 12.00 | 50.0% | 17.2% | ||||

| Eloquence | |||||||||

| No | 2192.2 | 90 | 15.78 | 65.6% | 25.6% | .538 | 1.09 | 0.815 | 1.477 |

| Yes | 2457.6 | 109 | 13.42 | 56.0% | 23.9% | ||||

| WHO grade | |||||||||

| III | 1819.9 | 33 | 67.82 | 90.9% | 72.7% | <.001** | 4.50 | 2.741 | 7.388 |

| IV | 2829.9 | 166 | 13.21 | 54.2% | 15.1% | ||||

| Total resection | |||||||||

| No | 2672.5 | 131 | 12.90 | 52.7% | 18.3% | .004** | 1.601 | 1.166 | 2.201 |

| Yes | 1977.3 | 68 | 22.85 | 75.0% | 36.8% | ||||

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||||||

| No | 545.7 | 36 | 4.21 | 22.2% | 16.7% | .001** | 1.92 | 1.305 | 2.836 |

| Yes | 4104 | 163 | 17.07 | 68.7% | 26.4% | ||||

| 5-ALA | |||||||||

| No | 2138.0 | 86 | 14.04 | 58.1% | 23.3% | .44 | 0.89 | 0.659 | 1.198 |

| Yes | 2511.8 | 113 | 14.61 | 62.0% | 25.7% | ||||

| Intraoperative MRI | |||||||||

| No | 3240.5 | 144 | 13.85 | 58.3% | 21.5% | .043* | 1.432 | 1.012 | 2.027 |

| Yes | 1409.3 | 55 | 17.89 | 65.5% | 32.7% | ||||

| Total | 4649.8 | 199 | 14.25 | 60.3% | 24.6% | ||||

P < .05.

P < .01.

5-Aminolevulinic Acid

All patients who received 5-ALA also underwent iMRI at surgery (Table 1). Patients receiving 5-ALA were more likely to achieve GTR at surgery than patients who did not receive 5-ALA (odds ratio: 3.19, P = .01, 95% CI: 1.28, 7.93; Table 2). No effect on PFS and OS (Tables 3 and 6) was observed in univariable models, and no effects were observed on PFS and OS in the multivariable models that adjust for resection status.

Discussion

In this initial series assessing the combined effect of iMRI and 5-ALA on survival in patients with high-grade gliomas, we found that the unadjusted OS was higher in the iMRI group than in the control group (P = .043). However, considering confounding variables in our study, multivariate analysis revealed that this finding failed to reach significance; neither iMRI nor 5-ALA is a predictor of improved OS. Rather, these surgical methods increase the likelihood of the surgeon to achieve GTR (Table 2), and they augment rates of PFS and OS through their effects on resection status (Tables 2 and 4).

Lack of Direct Effect of Intraoperative MRI on Survival

Our findings are similar to those in the trial by Stummer and colleagues9 of 5-ALA versus controls in which the treatment arm had smaller residual tumor volume (P < .0001) and achieved better OS on univariable analysis. We found that the effect of these combined treatments on OS abated when adjusted for resection status and other confounders.

There are several explanations. First, the addition of 5-ALA improves extent of resection12 and survival9 and may have dampened the effect of iMRI. Second, GTR was more prevalent among the iMRI group; in our study, a patient with subtotal resection was more than twice as likely to die during the observation period. GTR is a known predictor for survival,13 justifying the use of multimodal technical tools to maximize extent of resection.14 In our study, the initially significant effect of iMRI decreased to subsignificant levels in favor of GTR status, which became the stronger predictor of survival. Finally, the last confounding variable of good preoperative KPS (≥80), which was more common among the iMRI group, did not affect outcomes after multivariate correction. In addition, the low-field iMRI (0.15 Tesla) used in our study has a lower resolution compared with the diagnostic MRI systems (1.5–3 Tesla) and newer-generation iMRI systems (>1 Tesla). Whether this technical parameter led to a lower number of GTRs than would have been achieved at higher field strengths and whether such a discrepancy would have led to a tangible difference in outcomes remain elusive to determine. Intuitively, however, the advent of higher field strengths should lead to improved diagnostic yield and ultimately better resection rates.

Neuronavigation

Although there is no prospective trial to evaluate the effect of neuronavigation on survival in glioma surgery, it is considered to be one of the surgeon's most helpful tools in accurately obtaining intraoperative orientation.15 In one randomized trial of neuronavigation in a small population of patients with a solitary cerebral lesion, Willems and colleagues agreed that navigation was useful but did not enhance the rate of GTR.16 The study was conducted on a small population and was limited to solitary cerebral lesions, for which the surgeon already acknowledged that neuronavigation was not essential to the outcome. With the routine use of neuronavigation in practice, it is unlikely that any randomized clinical trials will be performed to evaluate its utility. In the setting of iMRI, navigated surgery is even more useful because the intraoperative imaging reflects the actual position and extension of brain and tumor tissue during surgery. In a prospective study of functional neuronavigation, Eyupoglu et al noted that the combined use of high-field iMRI and 5-ALA yielded complementary information and increased the rate of GTR.17

Intraoperative MRI

In 68 patients with high-grade gliomas, Wirtz and colleagues showed that iMRI led to higher rates of GTR5; similar to another retrospective series,6 this study had no control group. In a series of 98 high-grade gliomas operated on with iMRI, Nimsky et al18 focused on GTR and functional neuronavigation but did not provide patient survival. Our study's rate of 66% GTR is comparable to that of other studies with high rates of tumors in eloquent areas.

Combination of 5-ALA and Intraoperative MRI

Although robust evidence exists from prospective randomized neurosurgical studies that both 5-ALA9 and iMRI8 used individually are associated with improved survival, it is less common to correct for confounders and “intermediates” (ie, resection status). In our study, the use of 5-ALA was associated with a 3-fold higher likelihood of GTR. An intuitive conclusion is that the combination of both techniques should be beneficial, as confirmed in a post-hoc analysis (data not shown). However, the effect of a single technique, like iMRI, on survival is more difficult to prove when the “interfering” benefit of 5-ALA is corrected in a statistically sound manner.

Study Limitations

This study spanned several years during which neuro-oncological management of high-grade glioma evolved significantly, not only at our institution. Predictive biomarkers such as alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked,19 isocitrate dehydrogenase 1,20 and O6-DNA methylguanine-methyltransferase promoter methylation status21 were not routinely assessed in the early years of the study. Therefore, these biomarkers were not part of the present analysis. This introduces the potential of confounding biologically distinct subtypes of tumors with variable prognosis. Pooling all “high-grade glioma” patients instead of addressing grade IV or grade III tumors separately is a similar issue. A separate analysis of our grade IV data did not alter the message obtained by an analysis of the “pooled” high-grade cohort. However, usually neither precise tumor grade nor biological subtype is known until after surgery. Thus, we believe that the decision to use iMRI or any surgical adjunct should be made and evaluated based on preoperative criteria. The identification of the preoperative selection criteria that best justify the added effort of iMRI will need to be addressed in future studies.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that GTR, however accomplished, improves OS. In turn, the 5-ALA + iMRI combination and neuronavigation enhance GTR. To determine which of these adjuncts has a higher impact on survival would require a complex study design with many groups and will likely remain elusive. The use of iMRI prolongs the duration of surgery8 and is logistically challenging and costly. One may hypothesize that case selection for iMRI may be biased toward tumors lying in eloquent areas and more preferably used in patients who are sufficiently healthy to endure longer anesthesia. Future studies will need to address criteria for patient selection to provide a guideline as to whether certain patients (ie, with tumors of small size or in completely non-eloquent territories) may not require the addition of iMRI for successful treatment.

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Smoll NR, Hamilton B. Incidence and relative survival of anaplastic astrocytomas. Neuro Oncol. 2014;1610:1400–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoll NR, Schaller K, Gautschi OP. Long-term survival of patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(5):670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black PM, Moriarty T, Alexander E, 3rd, et al. Development and implementation of intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging and its neurosurgical applications. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(4):831–842, discussion 842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubben PL, ter Meulen KJ, Schijns OE, et al. Intraoperative MRI-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(11):1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirtz CR, Knauth M, Staubert A, et al. Clinical evaluation and follow-up results for intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(5):1112–1120, discussion 1120–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirschberg H, Samset E, Hol PK, et al. Impact of intraoperative MRI on the surgical results for high-grade gliomas. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2005;48(2):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senft C, Franz K, Ulrich CT, et al. Low field intraoperative MRI-guided surgery of gliomas: a single center experience. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(3):237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senft C, Bink A, Franz K, et al. Intraoperative MRI guidance and extent of resection in glioma surgery: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(11):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogelbaum MA, Jost S, Aghi MK, et al. Application of novel response/progression measures for surgically delivered therapies for gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) Working Group. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(1):234–243, discussion 243–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smoll NR, Schaller K, Gautschi OP. The cure fraction of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;39(1):63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marbacher S, Klinger E, Schwyzer L, et al. Use of fluorescence to guide resection or biopsy of primary brain tumors and brain metastases. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36(2):E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(2):190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schucht P, Beck J, Abu-Isa J, et al. Gross total resection rates in contemporary glioblastoma surgery: results of an institutional protocol combining 5-aminolevulinic acid intraoperative fluorescence imaging and brain mapping. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(5):927–935, discussion 935–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett GH, Kormos DW, Steiner CP, et al. Use of a frameless, armless stereotactic wand for brain tumor localization with two-dimensional and three-dimensional neuroimaging. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(4):674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willems PW, van der Sprenkel JW, Tulleken CA, et al. Neuronavigation and surgery of intracerebral tumours. J Neurol. 2006;253(9):1123–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eyupoglu IY, Hore N, Savaskan NE, et al. Improving the extent of malignant glioma resection by dual intraoperative visualization approach. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e44885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimsky C, Ganslandt O, Buchfelder M, et al. Intraoperative visualization for resection of gliomas: the role of functional neuronavigation and intraoperative 1.5T MRI. Neurol Res. 2006;28(5):482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao Y, Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, et al. Frequent ATRX, CIC, FUBP1 and IDH1 mutations refine the classification of malignant gliomas. Oncotarget. 2012;3(7):709–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321(5897):1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]