Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a genetic autosomal dominant disorder characterized by benign tumor-like lesions, called hamartomas, in multiple organ systems, including the brain, skin, heart, kidneys, and lung. These hamartomas cause a diverse set of clinical problems based on their location and often result in epilepsy, learning difficulties, and behavioral problems. TSC is caused by mutations within the TSC1 or TSC2 genes that inactivate the genes' tumor-suppressive function and drive hamartomatous cell growth. In normal cells, TSC1 and TSC2 integrate growth signals and nutrient inputs to downregulate signaling to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), an evolutionarily conserved serine-threonine kinase that controls cell growth and cell survival. The molecular connection between TSC and mTOR led to the clinical use of allosteric mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) for the treatment of TSC. Everolimus is approved for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and renal angiomyolipomas in patients with TSC. Sirolimus, though not approved for TSC, has undergone considerable investigation to treat various aspects of the disease. Everolimus and sirolimus selectively inhibit mTOR signaling with similar molecular mechanisms, but with distinct clinical profiles. This review differentiates mTOR inhibitors in TSC while describing the molecular mechanisms, pathogenic mutations, and clinical trial outcomes for managing TSC.

Keywords: everolimus, mammalian target of rapamycin, sirolimus, tuberous sclerosis complex

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a genetic autosomal dominant disorder characterized by hamartomas in multiple organ systems, including the brain, skin, heart, kidneys, and lung.1 Although considered nearly 100% penetrant, TSC disease presentation is highly variable with respect to age of symptom onset, severity, and degree of organ involvement. Although the tumors are characteristically benign, clinical symptoms appear primarily from complications secondary to tumor mass effect and replacement of normal surrounding tissues. For example, nodules and cystic changes in the lung can occur in 40%–60% of adult females, leading to decreased respiratory function and risk of recurrent pneumothoraces, a condition known as TSC-associated lymphangioleiomyomatosis (TSC-LAM). Hamartomatous lesions in kidneys, known as angiomyolipomas, occur in both genders and can lead to reduced renal function, hypertension, and risk of life-threatening hemorrhage.2 Various dermatologic, cardiac, ophthalmologic, gastroenteric, and endocrinologic manifestations also occur.3 In the brain, tumor-like tissue malformations have characteristic appearances that facilitate diagnostic confirmation of TSC; areas of focal cortical dysplasia known as tubers increase risk of intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, and psychiatric disease.4 Subependymal nodules (SENs) and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs) are also characteristic brain manifestations of TSC.5

The disease-causing mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which consist of deletions, insertions, and point mutations, disrupt the functional complex formed by the protein products of these 2 genes. In normal cells, TSC1 and TSC2 integrate growth signals and nutrient inputs to downregulate signaling to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), an evolutionarily conserved serine-threonine kinase that controls cell growth and cell survival. The molecular connection between TSC and mTOR led to the clinical use of allosteric mTOR inhibitors for the treatment of tuberous sclerosis. Specifically, everolimus is approved for SEGAs and renal angiomyolipomas in TSC patients,6 while sirolimus has not been approved for use despite considerable investigation to treat various aspects of the disease.7–11 Everolimus and sirolimus selectively inhibit mTOR signaling with similar molecular mechanisms, yet with quite distinct clinical profiles. This review differentiates mTOR inhibitors in TSC while describing the molecular mechanisms, pathogenic mutations, and clinical trial outcomes in TSC.

Genetic and Molecular Basis

To understand why mTOR inhibitors have gained prominence in TSC treatment, it is essential to appreciate the disorder's underlying genetic and molecular mechanisms and how mTOR plays a central role in disease pathogenesis. Initial studies involving multigenerational families demonstrated locus heterogeneity in TSC with linkage to 9q34 (TSC1) and 16p13.3 (TSC2),12,13 as well as loss of heterozygosity in hamartomas.14–16 Multiple groups have meticulously mapped the pathogenic mutations to better understand the effects of the diverse TSC1 and TSC2 missense mutations and in-frame insertions or deletions on TSC1–TSC2 activity (Fig. 1).17–20 The ratio of TSC2:TSC1 mutations has been reported to be 3.4:1, and the TSC2 gene has a higher mutation frequency per nucleotide compared with TSC1.21 A majority of mutations of TSC1 (99%) and TSC2 (75%) consist of single base-pair deletions or insertions and point mutations that cause premature termination codons downstream in the open-reading frame, thus generating a truncated or partial protein product causing complete inactivation of the gene or nonterminating missense mutations. In rare instances, although equally important, mutations can result in defective splicing that causes the disease.17 The extensive diversity and functional consequences of each mutation, combined with location and timing of acquired second hit mutations, have an important impact on the observed variability of clinical disease symptoms and range of organ involvement. Importantly, the majority of TSC patients harbor a TSC2 mutation that is associated with more severe clinical features.21,22 Patients with phenotypes with no mutation identified are generally less severe than those with TSC1 or TSC2 mutations.21 This potential relationship between mutational status and clinical severity underscores the need to better understand TSC1 and TSC2 pathogenic mutations for optimal clinical management of the disease.

Fig. 1.

Structural features of TSC1 and TSC2. The TSC1 gene is encoded by 21 exons and 1164 amino acids, whereas the TSC2 gene is encoded by 41 exons and is 1807 amino acids in length. The TSC1 and TSC2 gene products form a complex through defined interaction domains that inhibit the GTPase activity of Ras homolog enriched in brain that normally activates mTOR and cell growth. TSC1 and TSC2 contain several important regulatory phosphorylation sites indicated, along with kinase responsible. The arrows and amino acid positions indicate mutations identified in patients with TSC1 and TSC2 mutations.19

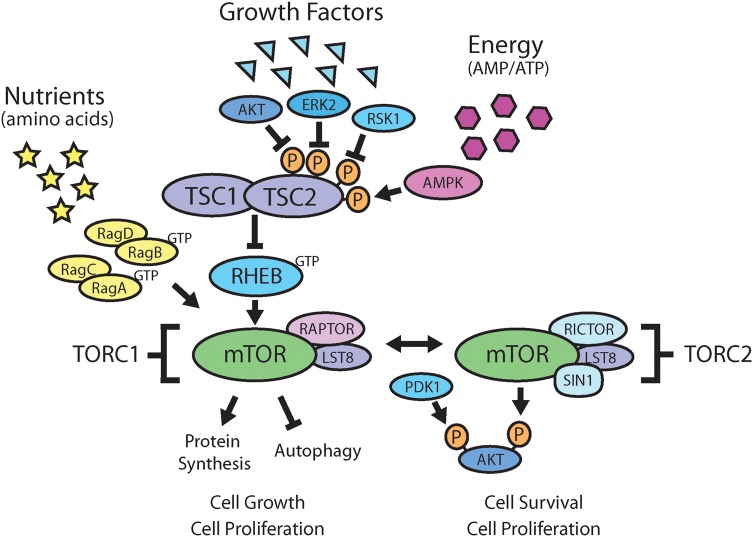

Critical functions of the TSC-mTOR pathway are nutrient-, growth factor-, and energy-sensing. Multiple upstream inputs from growth factors and energy converge on the TSC1/TSC2 complex, which represents a major phosphoacceptor site in the mTOR signaling cascade (Fig. 2).23 Mammalian TOR forms 2 distinct multiprotein complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), that are differentiated by their interaction partners (raptor [mTORC1) versus rictor/SIN1 [mTORC2]), substrate selectivity, and sensitivity to rapamycin and its analogs.24 In a normal cellular context, mTORC1 negatively regulates catabolic processes (such as autophagy) and activates anabolic processes (such as protein synthesis). In cells with constitutive mTORC1 activation, such as in TSC, the anabolic processes dominate over the catabolic processes, disrupt the normal balance, and give a cell-growth advantage over surrounding cells.25 The TSC1/TSC2 complex exerts control of the mTOR pathway by functioning as a GTPase-activating protein toward Ras homolog enriched in brain, a direct and positive regulator of mTORC1.26 In patients with TSC1 or TSC2 mutations, this functional complex is disrupted, leading to constitutive mTORC1 activation and the formation of hamartomatous lesions.

Fig. 2.

Nutrient, growth factor, and energy sensing impinge on the mTOR pathway. Both TSC1 and TSC2 are major pathway components in the mTOR signaling cascade. TSC is caused by mutations in either the TSC1 or TSC2 genes that interact in a protein-protein signaling complex to negatively regulate cell growth. Nutrients, growth factor, and energy status signal to the rapamycin-sensitive TORC1, while TORC2 is known to fully activate Akt.

Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytomas

SEGAs are the most commonly found brain tumor in TSC and usually arise near the caudothalamic groove proximal to the foramen of Monro in children and young adults. It is important to note that SEGAs have been reported throughout the CNS, and congenital SEGAs are being increasingly identified through prenatal ultrasounds, fetal MRI, or routine imaging obtained during the perinatal period.27,28 SEGAs arise from SENs, but not all SENs grow to become SEGAs. SENs, which are present at birth, exist in 80% of individuals with TSC, but the overall prevalence of SEGAs in TSC is estimated at only 5%–15%.29 The distinction between SENs and SEGAs is not always clear, because both are considered benign lesions with little or no malignancy potential, and there are no essential histological or molecular differences between them. Officially, SEGAs are classified as low-grade, World Health Organization grade I astrocytic neoplasms,30 although a mixed neuronal-glial classification would likely be more accurate as tumors almost universally stain positive for both neuronal and glial cell markers.31,32 Grossly, tumors are typically homogeneous and appear with mild atypia consisting of spindle cells, gemistocytic-like cells, and occasional ganglion-like cells. Microcalcification and gross calcification are common, but rosettes, endothelial proliferation, mitoses, inflammation, and necrosis can also be present.32 The hallmarks of SEGA, however, are large giant cells with prominent nuclei, microtubules, abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, free ribosomes indicative of neuronal differentiation, and bundles of intermediate filaments indicative of glial differentiation.32

Prior to the advent of modern imaging, SEGA classification was limited to lesions associated with hydrocephalus arising from obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid passage through the foramen of Monro. Although this clinical definition remains appropriate, SEGA now includes tumors with characteristic radiological features on CT or MRI, such as well-circumscribed tumors arising in typical subependymal locations, associated ventricular enlargement, or evidence of clear growth over time with repeated imaging (Fig. 3).33 SEGA diameter can range from <1 cm to >10 cm, leading to disfavor in using a minimal size as the criterion to distinguish between SEN and SEGA. Similarly, intravenous contrast uptake and calcification ranging from none to complete are typical and not useful for differentiating one from the other.

Fig. 3.

Major neurological features of TSC. (A) Cortical dysplasias (tubers and radial migration lines, black arrow) and subependymal nodules (white arrow). (B) Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas.

Most SEGAs are slow-growing, typically <0.5 cm/year in the longest dimension.34 Early symptoms of hydrocephalus may be subtle and gradually progressive, such as headaches, nausea, vomiting, ataxia, visual disturbances, increased seizures, irritability, or other mental status changes. If unaddressed or acutely obstructing, patients may present instead with lethargy or obtundation progressing rapidly to death. For best long-term survival and neurological outcome, evidence supports earlier intervention prior to emergence of clinical symptoms.35 In 2012, the International TSC Consensus Group recommended imaging surveillance every 1–3 years in asymptomatic patients until a minimum age of 20 and before clinical symptoms limit intervention options.33 Patients with SEGA require imaging more frequently, while treatment options are considered or treatment response is monitored. Historically, surgical excision has been the main SEGA treatment option and offers potential for definitive treatment. However, complete excision is not assured, and a comprehensive analysis reported a 15% SEGA recurrence rate and a 25% serious complication or injury rate.35 Modern technological advances, neurosurgeon expertise, operation timing, and individual patient presentation favor better outcomes at individual centers.36 For example, intraoperative MRI and adoption of minimally invasive techniques significantly lower morbidity risk.37 Despite such advances, a claims database review of TSC patients who underwent SEGA surgery between 2000 and 2009 revealed that nearly 13% required repeat surgery within the first year due to primary tumor recurrence, development of new SEGA, shunt placement or revision, or to treat complications, including bleeding, empyema, and abscesses.38 It is in this context that mTOR inhibitors, such as sirolimus and everolimus, evolved as a medical alternative to surgery for the treatment of SEGA.

Discovery and Development of Rapamycin and Rapamycin Analogs

Rapamycin is a natural product isolated from soil bacterium extracts found on Easter Island, which is also known by its native name, Rapa Nui. In 1964, a Canadian scientific expedition traveled to Easter Island to gather plant and soil samples from which they isolated and purified an active metabolite with antibiotic properties known as rapamycin from the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus.39 It was demonstrated that rapamycin contained strong antifungal activity.40,41 Two years after its isolation and characterization, rapamycin was found to have cytostatic activity in immune cells,42 and 5 years later in human tumor cells, including medulloblastoma and glioma.43 Rapamycin also was determined to be a potent immunosuppressive agent effective in preventing allograft rejection.44 Antiproliferative effects in yeast and lymphocytes led to rapamycin studies on childhood rhabdomyosarcoma tumor cell lines45 and adult lung cancer cells.46 Subsequently, the race began to test rapamycin (sirolimus) and develop new analogs (temsirolimus, everolimus, and ridaforolimus) to pilot in tumor models and clinical trials.47–51 These first-generation small molecule inhibitors of mTOR, consisting of rapamycin and rapamycin derivatives, can be collectively referred to as rapamycin analogs.

The mechanism of rapamycin started to be uncovered using Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where it bound the immunophilin FK506 binding protein (FKBP) and arrested yeast in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.52 Importantly, 2 genes—target of rapamycin 1 and 2 (TOR1 and TOR2)—were identified and appeared to interact in a complex with rapamycin.52 In mammalian cells, TOR exists as a single 289 kDa isoform (mTOR) that specifically binds to FKBP12.53 The ternary crystal structure was solved in 1996, revealing how rapamycin mediates FKBP12 dimerization with mTOR,54 which then blocks access to the mTOR kinase active site located in a deep cleft and hydrophobic pocket behind the FKBP12–rapamycin binding domain.55 Thus, rapamycin does not directly bind to the mTOR protein; rather, it is highly selective binding of rapamycin to FKBP12 and subsequent selective association of the FKBP12–rapamycin complex with mTORC1 that conveys highly sensitive and targeted mTORC1 inhibition.

Rapamycin (Sirolimus) and Its Analogs

Sirolimus was the first pharmacological agent in this class of mTORC1 inhibitors to be developed and approved (1999) by the FDA to prevent graft rejection in kidney transplant patients.56,57 Other rapamycin analogs have been approved subsequent to sirolimus, including temsirolimus (CCI-779) for advanced renal cell carcinoma58 and everolimus (RAD001) for prevention of solid organ transplant rejection59 and treatment of breast,60 renal,61 and neuroendocrine tumors.62 Another analog, AP23573 or MK-8669 (ridaforolimus), is in advanced stages of clinical development; however, it is not yet approved for any specific clinical indication.63 Only everolimus has been approved for the management of TSC disease manifestations, including SEGA64,65 and renal angiomyolipomas66; however, sirolimus has been shown in various case reports and multiple prospective clinical trials to benefit TSC patients.7–11

These analogs all share a central macrolide chemical structure, yet differ in the functional groups added at C40 (Fig. 4). Everolimus and ridaforolimus are hydroxyethyl ester and dimethylphosphinate derivatives, respectively, of sirolimus that are biochemically active without modification. In contrast, temsirolimus is a prodrug that requires removal of the dihydroxymethyl propionic acid ester group at C40 after administration, becoming sirolimus in its active form. The shared macrolide structure among the analogs permits an interaction with FKBP12, the mechanism by which these allosteric molecules selectively inhibit mTORC1 over mTORC2.54

Fig. 4.

The structure of rapamycin and its analogs. Chemical structures of sirolimus, everolimus, temsirolimus, and ridaforolimus all share a central macrolide chemical structure and have unique R groups at the C40 position. The FKBP12 (blue) and mTOR (red) interactions with the central macrolide rapamycin structure are indicated.

Although relatively minor, the differences at C40 have important clinical implications. First, bioavailability and half-life are significantly different among the compounds (Table 1). Sirolimus and everolimus are taken orally each day. Comparative pharmacokinetics suggest that everolimus is more readily absorbed and exhibits greater oral bioavailability compared with sirolimus due to selective intestinal cell efflux for which sirolimus alone is a substrate.6,67,68 Temsirolimus is formulated for weekly intravenous administration, bypassing this system altogether. The relative hydrophobicity of sirolimus does have its own benefits because it is readily absorbed through the skin69 and is used in custom topical preparations to treat TSC-related facial angiofibromas.11 The various rapamycin analogs differ in hepatic metabolism, in which everolimus is 2.7-fold lower than sirolimus.70 Nonetheless, sirolimus systemic clearance is half that of everolimus,67,71 giving everolimus faster steady state levels after initiation and faster elimination after discontinuation. On a pharmacodynamic level, mTORC1 inhibition appears comparable at physiologic dosing ranges, but tissue- and organelle-specific differences have been observed. For example, there is evidence that everolimus, but not sirolimus, distributes to brain mitochondria and stimulates mitochondrial oxidation in the brain.72

Table 1.

Clinical pharmacology of sirolimus, everolimus, temsirolimus, and ridaforolimus

| Sirolimus68 | Everolimus6,67 | Temsirolimus97 | Ridaforolimus63,98,99 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial names | Rapamune®, rapamycin | Afinitor®, RAD001, SDZ-RAD, Votubia®, Certican® | CCI-779, Torisel® | AP23573, MK-8669, deforolimus |

| Mechanism of action | Inhibition of PI3K–TSC–mTOR pathway, resulting in modulation of cellular metabolism, growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis | |||

| Molecular weight | 914.2 g/mol | 958.2 g/mol | 1030.3 g/mol | 990.2 g/mol |

| Route of administration | Once daily by mouth | Once daily by mouth | Intravenous infusion once per week | Oral or intravenous infusion |

| Protein binding | 92% | 75% | ∼85% | ∼94% |

| Bioavailability | Solution: 14% Tablet: 18% |

Tablet: 20% | Injection: 100% | Tablet: 16% |

| Terminal half-life | 46–78 h | 26–30 h | 9–27 h | ∼30–75 h |

| Solubility | Water insoluble | Water insoluble | Water insoluble, alcohol soluble |

Water insoluble |

| Main drug-drug interactions | CYP3A4, P-glycoprotein | CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C8 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4, P-glycoprotein |

| Elimination | Feces (91%), urine (2%) | Feces (>90%), urine (2%) | Feces (82%), urine (5%) | Feces (88%), urine (2%) |

More recently, second-generation pharmacological mTOR inhibitors have been developed. In contrast to the rapamycin analogs, these molecules are direct kinase inhibitors that do not target FKBP12, and instead inhibit both mTORC1 and mTORC2 by directly blocking the ATP catalytic site. There are >20 catalytic mTOR inhibitors; however, these compounds vary in sensitivity and selectivity for other intracellular protein kinases. These agents are useful to differentiate TORC1- versus TORC2-mediated intracellular signaling, and important differences are reported compared with rapamycin in downstream target inhibition, feedback loops, and protein translation control. These newer agents are potent inhibitors of cellular proliferation and therefore could have therapeutic benefit. Second-generation mTOR inhibitors are in either preclinical or early clinical development for oncology indications, but to date none have completed phase III clinical trials or received regulatory approval for human use. Clinical development for TSC has yet to occur, and it will be important to demonstrate that dual targeting of TORC1/TORC2 provides superior efficacy without introducing significant increases in toxicity.

Clinical Trials to Treat Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

Of the different mTOR inhibitors, only sirolimus and everolimus have been clinically evaluated for the management of TSC patients. The first report of sirolimus as a TSC treatment occurred in 2006, when 5 patients with SEGA tumors were treated for 2.5 to 20 months and demonstrated an average 55% reduction in tumor volume, negating the need for resective surgery.73 In 2008 a prospective, open-label clinical trial with sirolimus to treat renal angiomyolipomas began7; in 2011 a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to treat LAM with or without TSC was completed.8 Both studies demonstrated a favorable safety and efficacy profile of sirolimus for treating specific TSC disease manifestations. Importantly, both also included follow-up observations wherein it was demonstrated that disease progression resumes if treatment is discontinued. In other words, for clinical benefit to be sustained, treatment must be maintained for prolonged periods and possibly indefinitely. It remains to be demonstrated whether there is a critical threshold, such as minimum treatment duration or magnitude of response, or a combinatorial therapeutic strategy (ie, dual targeting of mTOR and autophagy) that might allow efficacy to be maintained.

More recently, rapamycin analogs have been explored in topical formulations for the management of facial angiofibromas. Sirolimus is available in a topical formulation, and individual case reports have demonstrated the effectiveness of custom preparations varying in composition and concentration.74–76 In the only prospective clinical trial reported to date, 73% of patients (n = 28) experienced reductions in facial angiofibroma.11 To confirm these findings, a follow-up, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, phase III clinical trial evaluating different sirolimus concentrations is ongoing (NCT01526356). Despite consistent findings across various TSC studies, sirolimus is not yet approved, due largely to clinical trial study design limitations and/or lack of phase III clinical trials evaluating the same TSC manifestation. There are active efforts seeking regulatory approval for sirolimus to treat TSC disease manifestations in the United States and other countries, under alternative approval processes established for orphan drugs and rare disease populations.

Following the initial report of sirolimus to treat SEGA,73 individual case reports and small case series and open-label clinical trials demonstrated similar reduction in SEGA tumor volume.9,77–79 However, to date everolimus is the only mTOR inhibitor to be FDA approved to treat SEGA in TSC after 2 major clinical trials demonstrated efficacy and safety.64,65 The first was a prospective, open-label study of 28 patients who demonstrated SEGA growth on MRI before treatment initiation.64 All 28 patients demonstrated a reduction in tumor volume or cessation of growth. Overall, nearly 80% of patients had SEGAs that were reduced by a third, and more than 30% of patients had SEGAs that were reduced by more than half within 6 months of treatment. Side effects were largely mild to moderate in severity, and none led to treatment discontinuation. Further analysis after continuous treatment (median of 3 y) revealed that efficacy was sustained without encountering new or additional significant side effects.80 The second study, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial involving 117 patients with SEGAs from 24 different TSC centers, reported similar results: SEGA volume was reduced more than 50% in 49% of patients treated a median of 29 months.65,81

In addition to treatment of SEGA, mTOR inhibitors may have additional benefit for treatment of CNS-related disease manifestations. Seizure control, cognitive development, and behavior have improved with everolimus when evaluated as a secondary outcome.64,78,82 In 2013 the first prospective clinical trial to specifically evaluate everolimus efficacy for medically refractory epilepsy in patients with TSC was conducted.83 Seizure frequency was reduced by 50% or more in 12 of 20 patients, including several cases where dramatic improvement was observed in patients with prior history of failed medications, vagus nerve stimulation, or epilepsy surgery. Improvement in multiple aspects of behavior and neurocognition were also reported. It is worth noting that response to treatment was highly variable, and 3 patients experienced an unexpected increase in seizures. Complicating the clinical picture are the phase III clinical trial results for SEGA,65 in which seizure frequency and behavior measures as secondary endpoints failed to confirm the treatment benefit of everolimus. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials are currently under way to specifically evaluate everolimus' effect on primary outcome measures of seizure control (NCT01713946) and neurocognition (NCT01289912).

Sirolimus and everolimus were initially developed to treat fungal infections and cancer and to prevent organ transplant rejection. As a result, robust knowledge around dosing and treatment-related side effects existed years before these drugs were first used to treat TSC. The most frequently encountered medication-related toxicities include mouth ulcers, hypercholesterolemia, marrow suppression, infections, and metabolic effects.84,85 These toxicities are relatively well known and straightforward to manage, except when frequent or severe. The same toxicities occur in TSC patients with overall reduced frequency and severity.8,65,66 The exact reason for this is not known; however, a possible explanation is that these agents are monotherapies for TSC patients, whereas in other oncologic and transplant settings they are frequently combined with chemotherapy or immunosuppressant regimens. Another key difference to note, particularly for cancer treatment, is that dosing is closer to the maximum tolerated dose, while in TSC dosing strategies seek to identify the minimum effective dose, thus avoiding side effects associated with higher doses.

The effect that these molecules have on the immune system should also be noted, as it was their immunosuppressive properties that led them to be initially used in transplant medicine.42 Early TSC clinical trials reported infections in as many as 80%–90% of patients; however, this is misleading because the study designs recorded all infections as treatment related and the evaluation period for study participants was a minimum of 1 year.64 These infections were of common type and severity, and the infection rate actually decreased the longer the patient received treatment.80 The larger, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trials using everolimus to treat angiomyolipomas and SEGAs provide a clearer picture of infection risk. The infection rate in these latter studies generally occurred in only 10%–20% of individuals and was nearly identical in both the treatment and placebo groups.65,66 In fact, in TSC clinical trials, most infections are reported as either mild or moderate in severity, and infections are rarely cited as the reason for discontinuing treatment.64–66,80

Clinical Decision Making: Sirolimus Versus Everolimus

Given the abundance of supporting evidence for the efficacy of sirolimus and everolimus in treating the same TSC manifestations, which medication should be favored when initiating treatment? In preclinical studies, the 2 agents are often used interchangeably, but direct side-by-side comparisons are rarely made in the same study design. Sirolimus demonstrates slightly higher binding affinity to FKBP12 than everolimus (half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 0.4–0.9 nM vs 1.8–2.6 nM, respectively),86 although this difference is not likely to be relevant clinically because human serum levels range between 5 and 15 ng/mL (5.5–16.4 nM). When compared, both agents similarly inhibit cell proliferation and T-cell immunologic activity, and both are efficacious in preventing organ rejection.86

To date, clinical trials directly comparing everolimus and sirolimus are lacking in oncology, transplantation, and TSC. In TSC specifically, we performed a cross-sectional analysis of patients at 2 major TSC centers treated with either sirolimus or everolimus and found that tumor reduction was comparable between the 2, generally within 1%–5% when examined by quartiles.87 Along these lines, we observed best responses to treatment in patients with newly identified SEGA or renal angiomyolipoma with unmistakable growth exceeding the typical 0.5 cm/year evidenced on serial imaging. Tumors with much slower growth rates or increasing degree of calcifications also respond to treatment, but the degree of response is often less robust. Analysis of existing clinical trials and postmarketing studies are needed to confirm these observations and uncover potential clinical predictors for clinicians to identify those patients more likely to respond to treatment.

In the absence of head-to-head clinical trials, selection of a specific mTOR inhibitor in TSC has generally followed the best published evidence to date for the specific disease manifestation. Sirolimus is generally favored for TSC-LAM because there have been no published major clinical trials in TSC-LAM that have used everolimus, although a multicenter trial has recently been completed. Considering that only sirolimus is currently formulated for topical application, it is generally used for the management of facial angiofibromas. Decision making for management of renal angiomyolipoma and SEGA is less clear. Multiple clinical trials have been published that used either agent with similar efficacy and tolerability in TSC patients, but clinical trials using everolimus typically have involved greater numbers of subjects and include several studies with a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Furthermore, long-term treatment studies have exclusively focused on everolimus, and the patients have been treated continuously for 2–7 years.80 These long-term studies have not revealed any new toxicities different than those observed in the initial short-term treatment studies spanning 0.5 to 2 years. Rather, prolonged treatment appears to be associated with improved tolerability, with fewer reported adverse events overall.80 In the absence of such direct comparisons, the more robust clinical trial experience with everolimus combined with regulatory approvals by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency provide the most compelling reason favoring everolimus over sirolimus to treat SEGA and other TSC disease manifestations at this time.

Future Directions and Conclusions

Successful development of sirolimus and everolimus for TSC has stimulated intense interest in improving therapeutic options for patients with TSC and other similar disorders. Two major strategies have emerged. First, all published evidence indicates that treatment must be sustained, perhaps indefinitely, for durable treatment effect. A management paradigm in which treatment could be reduced or discontinued over time while benefit is maintained would be preferable to lifelong therapy. One explanation for the loss of sustained treatment effect could be the unintended upregulation of competing cell-survival mechanisms, such as autophagy.88 Exposure to rapamycin analogs induce autophagy, and combination treatment with mTOR inhibitors and anti-autophagy agents sustains treatment response in vitro. Multiple human clinical studies that combine autophagy and mTOR inhibitors are under way, including a phase I study of hydroxychloroquine and sirolimus in women with TSC-LAM (NCT01687179).

The second major strategy is to expand on the treatment progress found in TSC patients for other disorders with similar pathology and/or disease manifestations. For example, patients with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) hamartoma tumor syndromes, such as Cowden syndrome and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, develop hamartomas and exhibit high rates of autism, developmental delay, epilepsy, and intellectual disability.89,90 PTEN, similar to TSC1/TSC2, acts as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) signaling upstream of TSC1/TSC2.91 Mammalian TOR inhibitors have been shown to reverse disease characteristics in PTEN animal models,92,93 and isolated case reports suggest similar benefits may be possible in humans.94,95 Additional proliferative and overgrowth syndromes, including large vascular and lymphatic malformations, have also responded well to mTOR inhibitors.96

Meanwhile, investigation with mTOR inhibitors continues in TSC. Initial studies focused on reduction of hamartomatous lesions of the brain, lung, kidney, and skin. Current studies are focused on the safety and efficacy of these agents when used to treat additional TSC-associated disease manifestations with greater prevalence and morbidity—including epilepsy, cognitive impairments, and autism—that affect 50%–80% of these patients.83 In addition, strategies to prevent or reduce disease severity are being actively pursued, including preventing SEN from transforming to SEGA. Perhaps using these agents as disease modifiers represents overzealous enthusiasm; however, when we consider the remarkable progress made so far—from the discovery of rapamycin on Rapa Nui to the successful repurposing of this antifungal, immunosuppressive, antigrowth agent in TSC—prospects for their future therapeutic applications appear vast.

Funding

Editorial support provided by ApotheCom was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Acknowledgments

J.P.M. wishes to thank the Michigan Strategic Fund, Van Andel Research Institute, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, Great Lakes Scrip, Rockford Construction, Colliers International, Team Hannah TSC, and individual donors for funding and grant support for research. D.A.K. gratefully acknowledges the National Institutes of Health and the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance for research funding.

Conflict of interest statement. J.P.M. has nothing to disclose. D.A.K. has received support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation for research, consulting, and speaking not associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Gomez MR. Varieties of expression of tuberous sclerosis. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1(5–6):330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northrup H, Krueger DA. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: Recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49(4):243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolton PF, Park RJ, Higgins JN, et al. Neuro-epileptic determinants of autism spectrum disorders in tuberous sclerosis complex. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 6):1247–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curatolo P, Verdecchia M, Bombardieri R. Tuberous sclerosis complex: a review of neurological aspects. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2002;6(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Afinitor (everolimus tablets for oral administration). Afinitor Disperz (everolimus tablets for oral suspension) [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(2):140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormack FX, Inoue Y, Moss J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1595–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dabora SL, Franz DN, Ashwal S, et al. Multicenter phase 2 trial of sirolimus for tuberous sclerosis: kidney angiomyolipomas and other tumors regress and VEGF-D levels decrease. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e23379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies DM, de Vries PJ, Johnson SR, et al. Sirolimus therapy for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a phase 2 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(12):4071–4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, et al. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topically applied rapamycin. Drugs R D. 2012;12(3):121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell. 1993;75(7):1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Povey S, Burley MW, Attwood J, et al. Two loci for tuberous sclerosis: one on 9q34 and one on 16p13. Ann Hum Genet. 1994;58(Pt 2):107–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green AJ, Smith M, Yates JR. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 16p13.3 in hamartomas from tuberous sclerosis patients. Nat Genet. 1994;6(2):193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henske EP, Scheithauer BW, Short MP, et al. Allelic loss is frequent in tuberous sclerosis kidney lesions but rare in brain lesions. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59(2):400–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sepp T, Yates JR, Green AJ. Loss of heterozygosity in tuberous sclerosis hamartomas. J Med Genet. 1996;33(11):962–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen FE, Braams O, Vincken KL, et al. Overlapping neurologic and cognitive phenotypes in patients with TSC1 or TSC2 mutations. Neurol. 2008;70(12):908–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nellist M, van den Heuvel D, Schluep D, et al. Missense mutations to the TSC1 gene cause tuberous sclerosis complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(3):319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Wentink M, van den Heuvel D, et al. Functional assessment of variants in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes identified in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum Mutat. 2011;3(4):424–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nellist M, Sancak O, Goedbloed MA, et al. Distinct effects of single amino-acid changes to tuberin on the function of the tuberin-hamartin complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sancak O, Nellist M, Goedbloed M, et al. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: genotype:phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in tuberous sclerosis complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(6):731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN, et al. Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(1):64–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aicher LD, Campbell JS, Yeung RS. Tuberin phosphorylation regulates its interaction with hamartin. Two proteins involved in tuberous sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):21017–21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang J, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 1):217–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412(2):179–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Inoki K, Guan KL. Biochemical and functional characterizations of small GTPase Rheb and TSC2 GAP activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(18):7965–7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raju GP, Urion DK, Sahin M. Neonatal subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: new case and review of literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36(2):128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotulska K, Borkowska J, Mandera M, et al. Congenital subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30(12):2037–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwiatkowski DJ, Wittemore V, Theile E. Pathogenesis of TSC in the brain. In: Crino PB, Mehta R, Vinters HV, eds. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Genes, Clinical Features and Therapeutics. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:159–185. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopes MBS, Wiestler OD, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Sharma MC. Tuberous sclerosis complex and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th ed Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007:218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrows BD, Rutkowski MJ, Gultekin SH, et al. Evidence of ambiguous differentiation and mTOR pathway dysregulation in subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2012;28(2):95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buccoliero AM, Franchi A, Castiglione F, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA): is it an astrocytoma? Morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Neuropathol. 2009;29(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krueger DA, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuccia V, Zuccaro G, Sosa F, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in children with tuberous sclerosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003;19(4):232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Ribaupierre S, Dorfmuller G, Bulteau C, et al. Subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in pediatric tuberous sclerosis disease: when should we operate? Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1):83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berhouma M. Management of subependymal giant cell tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex: the neurosurgeon's perspective. World J Pediatrics. 2010;6(2):103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine NB, Collins J, Franz DN, Crone KR. Gradual formation of an operative corridor by balloon dilation for resection of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in children with tuberous sclerosis: specialized minimal access technique of balloon dilation. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006;49(5):317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun P, Kohrman M, Liu J, et al. Outcomes of resecting subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) among patients with SEGA-related tuberous sclerosis complex: a national claims database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(4):657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vezina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28(10):721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sehgal SN, Baker H, Vezina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. II. Fermentation, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1975;28(10):727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker H, Sidorowicz A, Sehgal SN, Vézina C. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. III. In vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1978;31(6):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martel RR, Klicius J, Galet S. Inhibition of the immune response by rapamycin, a new antifungal antibiotic. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1977;55(1):48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houchens DP, Ovejera AA, Riblet SM, Slagel DE. Human brain tumor xenografts in nude mice as a chemotherapy model. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983;19(6):799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris RE, Wu J, Shorthouse R. A study of the contrasting effects of cyclosporine, FK 506, and rapamycin on the suppression of allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 1990;22(4):1638–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dilling MB, Dias P, Shapiro DN, et al. Rapamycin selectively inhibits the growth of childhood rhabdomyosarcoma cells through inhibition of signaling via the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 1994;54(4):903–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seufferlein T, Rozengurt E. Rapamycin inhibits constitutive p70s6k phosphorylation, cell proliferation, and colony formation in small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56(17):3895–3897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clackson T, Metcalf C, Rivera V, et al. Broad anti-tumor activity of AP23573, an mTOR inhibitor in clinical development. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22 Abstract 882. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boulay A, Zumstein-Mecker S, Stephan C, et al. Antitumor efficacy of intermittent treatment schedules with the rapamycin derivative RAD001 correlates with prolonged inactivation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(1):252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raymond E, Alexandre J, Faivre S, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of escalated doses of weekly intravenous infusion of CCI-779, a novel mTOR inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(12):2336–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA, III, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1588–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991;253(5022):905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, et al. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229(1):105–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP. Science. 1996;273(5272):239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang H, Rudge DG, Koos JD, et al. mTOR kinase structure, mechanism and regulation. Nature. 2013;497(7448):217–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kahan BD. Efficacy of sirolimus compared with azathioprine for reduction of acute renal allograft rejection: a randomised multicentre study. The Rapamune US Study Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9225):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacDonald AS. A worldwide, phase III, randomized, controlled, safety and efficacy study of a sirolimus/cyclosporine regimen for prevention of acute rejection in recipients of primary mismatched renal allografts. Transplant. 2001;71(2):271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2271–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tedesco SH, Cibrik D, Johnston T, et al. Everolimus plus reduced-exposure CsA versus mycophenolic acid plus standard-exposure CsA in renal-transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(6):1401–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116(18):4256–4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mita MM, Mita AC, Chu QS, et al. Phase I trial of the novel mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor deforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) administered intravenously daily for 5 days every 2 weeks to patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1801–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirchner GI, Meier-Wiedenbach I, Manns MP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of everolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(2):83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. Rapamune (sirolimus) oral solution and tablets [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rauktys A, Lee N, Lee L, Dabora SL. Topical rapamycin inhibits tuberous sclerosis tumor growth in a nude mouse model. BMC Dermatology. 2008;8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobsen W, Serkova N, Hausen B, et al. Comparison of the in vitro metabolism of the macrolide immunosuppressants sirolimus and RAD. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1–2):514–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahalati K, Kahan BD. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sirolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(8):573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klawitter J, Gottschalk S, Hainz C, et al. Immunosuppressant neurotoxicity in rat brain models: oxidative stress and cellular metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(3):608–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Franz DN, Leonard J, Tudor C, et al. Rapamycin causes regression of astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mutizwa MM, Berk DR, Anadkat MJ. Treatment of facial angiofibromas with topical application of oral rapamycin solution (1mgmL(-1)) in two patients with tuberous sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(4):922–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wheless JW, Almoazen H. A novel topical rapamycin cream for the treatment of facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(7):933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salido R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Cuevas-Asencio I, et al. Sustained clinical effectiveness and favorable safety profile of topical sirolimus for tuberous sclerosis–associated facial angiofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(10):1315–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lam C, Bouffet E, Tabori U, et al. Rapamycin (sirolimus) in tuberous sclerosis associated pediatric central nervous system tumors. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2010;54(3):476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cardamone M, Flanagan D, Mowat D, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors for intractable epilepsy and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Pediatr. 2014;17:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koenig MK, Butler IJ, Northrup H. Regression of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma with rapamycin in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(10):1238–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krueger DA, Care MM, Agricola K, et al. Everolimus long-term safety and efficacy in subependymal giant-cell astrocytoma. Neurol. 2013;80:574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: 2-year open-label extension of the randomised EXIST-1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(13):1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kotulska K, Chmielewski D, Borkowska J, et al. Long-term effect of everolimus on epilepsy and growth in children under 3 years of age treated for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013;17(5):479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krueger DA, Wilfong AA, Holland-Bouley K, et al. Everolimus treatment of refractory epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(5):679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soefje SA, Karnad A, Brenner AJ. Common toxicities of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors. Targeted Oncol. 2011;6(2):125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev. 2014;28(3):126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schuler W, Sedrani R, Cottens S, et al. SDZ RAD, a new rapamycin derivative: pharmacological properties in vitro and in vivo. Transplant. 1997;64(1):36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoon S, Ung N, Mehta N, et al. Medical management with mTOR inhibitors vs surgical resection: comparison of clinical outcomes for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGA) in tuberous sclerosis complex. Neurol. 2013;80 (Meeting abstracts 1):PL01.001. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu J, Parkhitko A, Henske EP. Autophagy: an ‘Achilles’ heel of tumorigenesis in TSC and LAM. Autophagy. 2011;7(11):1400–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McBride KL, Varga EA, Pastore MT, et al. Confirmation study of PTEN mutations among individuals with autism or developmental delays/mental retardation and macrocephaly. Autism Research. 2010;3(3):137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gustafson S, Zbuk KM, Scacheri C, Eng C. Cowden syndrome. Semin Oncol. 2007;34(5):428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, et al. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Squarize CH, Castilho RM, Gutkind JS. Chemoprevention and treatment of experimental Cowden's disease by mTOR inhibition with rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):7066–7072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhou J, Blundell J, Ogawa S, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 suppresses anatomical, cellular, and behavioral abnormalities in neural-specific Pten knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29(6):1773–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iacobas I, Burrows PE, Adams DM, et al. Oral rapamycin in the treatment of patients with hamartoma syndromes and PTEN mutation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(2):321–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmid GL, Kassner F, Uhlig HH, et al. Sirolimus treatment of severe PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: case report and in vitro studies. Pediatr Res. 2014;75(4):527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(6):1018–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pfizer. Torisel Kit (temsirolimus) injection, for intravenous infusion only [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Pfizer; May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mita MM, Poplin E, Britten CD, et al. Phase I/IIa trial of the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor ridaforolimus (AP23573; MK-8669) administered orally in patients with refractory or advanced malignancies and sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.European Medicines Agency. Withdrawal assessment report for Jenzyl. December 3, 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Application_withdrawal_assessment_report/human/002259/WC500138917.pdf Accessed May 21, 2015.