Abstract

The topological aspects of electrons in solids can emerge in real materials, as represented by topological insulators. In theory, they show a variety of new magneto-electric phenomena, and especially the ones hosting superconductivity are strongly desired as candidates for topological superconductors. While efforts have been made to develop possible topological superconductors by introducing carriers into topological insulators, those exhibiting indisputable superconductivity free from inhomogeneity are very few. Here we report on the observation of topologically protected surface states in a centrosymmetric layered superconductor, β-PdBi2, by utilizing spin- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Besides the bulk bands, several surface bands are clearly observed with symmetrically allowed in-plane spin polarizations, some of which crossing the Fermi level. These surface states are precisely evaluated to be topological, based on the Z2 invariant analysis in analogy to three-dimensional strong topological insulators. β-PdBi2 may offer a solid stage to investigate the topological aspect in the superconducting condensate.

Materials possessing topologically non-trivial electronic surface states are predicted to host exotic Majorana fermion excitations in the superconducting state. Here, the authors demonstrate the existence of topologically-protected surface states in the centrosymmetric layered superconductor β-PdBi2.

Materials possessing topologically non-trivial electronic surface states are predicted to host exotic Majorana fermion excitations in the superconducting state. Here, the authors demonstrate the existence of topologically-protected surface states in the centrosymmetric layered superconductor β-PdBi2.

Topological insulators are characterized by the non-trivial Z2 topological invariant acquired when the conduction and valence bands are inverted by spin–orbit interaction (SOI), and the gapless surface state appears1,2,3. This topologically non-trivial surface state possesses the helical spin polarization locked to momentum, and is expected to host various kinds of new magneto-electric phenomena. Especially, the ones realized with superconductivity are theoretically investigated as the candidates for topological superconductor2,3,4, whose excitation is described as Majorana Fermions, that is, the hypothetical particles originating from the field of particle physics5,6,7,8. Experimentally, several superconductors developed by utilizing topological insulators are reported thus far, such as Cu-intercalated Bi2Se3 (refs 9, 10, 11, 12), In-doped SnTe13 and M2Te3 (M=Bi, Sb) under pressure14,15. While the previous studies of point-contact spectroscopy on CuxBi2Se3 (refs 9, 10) and In-SnTe13 suggest the existence of Andreev bound states thus raising the possibility of topological superconductivity, the scanning tunnelling microscope/spectroscopy reports the simple s-wave-like full superconducting gap16. Theoretically, this contradiction has been discussed in terms of the possible peculiar bulk odd-parity pairing17, which awaits experimental verifications by various probes18,19. However, partly due to the inhomogeneity effect accompanied by doping or pressurizing, the unambiguous clarification of superconducting states in doped topological insulators has been hindered until now. The half-Heusler superconductor RPtBi (R: rare earth) is another class of material recently reported as a candidate for topological superconductors20,21. Practically, however, its low critical temperature (Tc) of Tc<2 K and the noncentrosymmetric crystal structure without a unique cleavage plane may pose some difficulties for its further investigation.

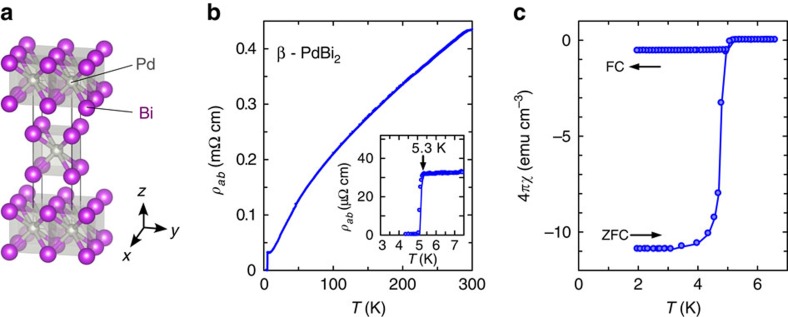

In this work, we introduce a superconductor β-PdBi2 with a centrosymmetric tetragonal crystal structure of space group I4/mmm22,23,24 as shown in Fig. 1a. It has a much simpler structure compared with the related noncentrosymmetric superconductor α-PdBi, recently being discussed as a possible topological superconductor25,26. Pd atoms, each of them located at the centre of the square prism of eight Bi atoms, form the layered body-centred unit cell. PdBi2 layers are stacked in van der Waals nature, making it a feasible compound for cleaving. We investigate the electronic structure of β-PdBi2 using (spin-) angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, (S)ARPES. With the large single crystals of good quality, exhibiting the high residual resistivity ratio (∼14) and a clear superconducting transition at Tc=5.3 K, several spin-polarized surface states are clearly observed in addition to the bulk bands. On the basis of the relativistic first-principles calculation on bulk and the slab calculation on surface, we find that the observed surface states can be unambiguously interpreted to be topologically non-trivial.

Figure 1. Basic properties of superconductor β-PdBi2.

(a) Crystal structure of superconductor β-PdBi2. x, y and z axes are taken along the body-centred tetragonal crystal orientation. (b) In-plane electrical resistivity (ρab) as a function of temperature (T). The inset shows ρab near the critical temperature (5.3 K). (c) Magnetic susceptibility (χ) as a function of T, recorded under the field-cool (FC) and zero-field-cool (ZFC) conditions. The magnetic field of 10 Oe was applied along the direction of the c axis.

Results

Bulk and surface band structures

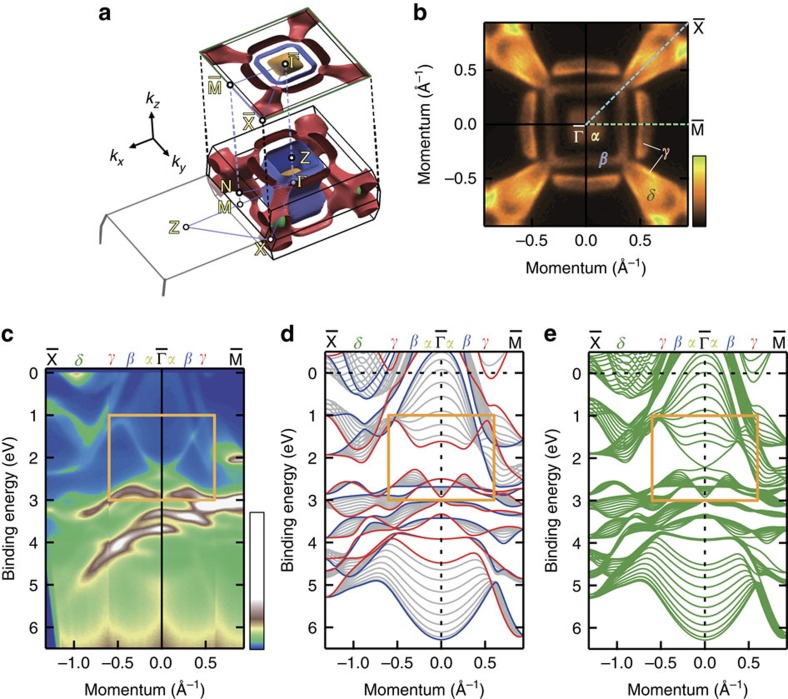

Here we present the ARPES result obtained using the single-crystalline β-PdBi2. The resistivity and magnetic susceptibility of the sample as shown in Fig. 1b,c clearly indicate the sharp superconducting transitions. The band structure of β-PdBi2 observed by ARPES is shown in Fig. 2b,c. For simply describing the (S)ARPES results hereafter, we use the projected two-dimensional (2D) surface Brillouin zone depicted in Fig. 2a by a green square. The projected high-symmetry points are  ,

,  and

and  , and we define kx as the momentum along

, and we define kx as the momentum along  –

– . The ARPES image in Fig. 2c is recorded along

. The ARPES image in Fig. 2c is recorded along  –

– and

and  –

– , respectively. Bands crossing the Fermi level (EF) are predominantly derived from Bi 6p components with large dispersions from the binding energy (EB) of EB∼6 eV to above EF. On the other hand, bands mainly consisting of Pd 4d orbitals are located around EB=2.5∼5 eV with rather small dispersions. Near EF, two hole bands (α, β) and one electron band (γ) are observed along

, respectively. Bands crossing the Fermi level (EF) are predominantly derived from Bi 6p components with large dispersions from the binding energy (EB) of EB∼6 eV to above EF. On the other hand, bands mainly consisting of Pd 4d orbitals are located around EB=2.5∼5 eV with rather small dispersions. Near EF, two hole bands (α, β) and one electron band (γ) are observed along  –

– , whereas for

, whereas for  –

– , the large ARPES intensity from another electron band (δ) is additionally observed. As we can see in Fig. 2b, the experimental Fermi surface mapping mostly well agrees with the 2D projection of the calculated bulk Fermi surfaces (Fig. 2a).

, the large ARPES intensity from another electron band (δ) is additionally observed. As we can see in Fig. 2b, the experimental Fermi surface mapping mostly well agrees with the 2D projection of the calculated bulk Fermi surfaces (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Electronic structure of β-PdBi2.

(a) Calculated Fermi surfaces shown with the first Brillouin zone. kx, ky and kz axes for the crystal momentum space are depicted. Γ, Z, N, X and M are the high-symmetry points. The square plane represents the two-dimensional (2D) projected surface Brillouin zone with 2D high-symmetry points,  ,

,  and

and  . (b) Four-fold symmetrized Fermi surface recorded by angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES). The image is obtained by integrating intensities in the energy window of ±8 meV at the Fermi level. The colour scale indicates the intensity. Two electron-like and two hole-like Fermi surfaces are denoted by α, β and γ, δ, respectively. (c) ARPES image recorded along

. (b) Four-fold symmetrized Fermi surface recorded by angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES). The image is obtained by integrating intensities in the energy window of ±8 meV at the Fermi level. The colour scale indicates the intensity. Two electron-like and two hole-like Fermi surfaces are denoted by α, β and γ, δ, respectively. (c) ARPES image recorded along  –

– and

and  –

– cuts, shown as the light-blue and -green broken lines in b, respectively. The colour scale indicates the intensity. (d) Calculated bulk band dispersions projected onto 2D surface Brillouin zone. Blue (red) curves correspond to kz=0 (2π/c). (e) Surface band dispersions obtained by slab calculation of 11 PdBi2 layers. Orange rectangles in c–e indicate the region where the surface Dirac cone appears.

cuts, shown as the light-blue and -green broken lines in b, respectively. The colour scale indicates the intensity. (d) Calculated bulk band dispersions projected onto 2D surface Brillouin zone. Blue (red) curves correspond to kz=0 (2π/c). (e) Surface band dispersions obtained by slab calculation of 11 PdBi2 layers. Orange rectangles in c–e indicate the region where the surface Dirac cone appears.

To compare with ARPES, the calculation of bulk band dispersions projected into 2D Brillouin zone is shown in Fig. 2d. Considering that the ARPES intensity includes the integration of finite kz-dispersions due to the surface sensitivity, the overall electronic structure is in a good agreement with the calculation; nevertheless, several differences can be noticed. The most prominent one appears in the orange rectangles in Fig. 2c,d. A sharp Dirac-cone-like dispersion is experimentally observed where the calculated bulk bands show a gap of ∼0.55 eV around the  point. To confirm its origin, we performed a slab calculation for 11 PdBi2 layers (Fig. 2e). Apparently, a Dirac-cone-type dispersion appears in the gapped bulk states, showing a striking similarity to ARPES (Fig. 2c). It clearly presents the surface origin of this Dirac-cone band.

point. To confirm its origin, we performed a slab calculation for 11 PdBi2 layers (Fig. 2e). Apparently, a Dirac-cone-type dispersion appears in the gapped bulk states, showing a striking similarity to ARPES (Fig. 2c). It clearly presents the surface origin of this Dirac-cone band.

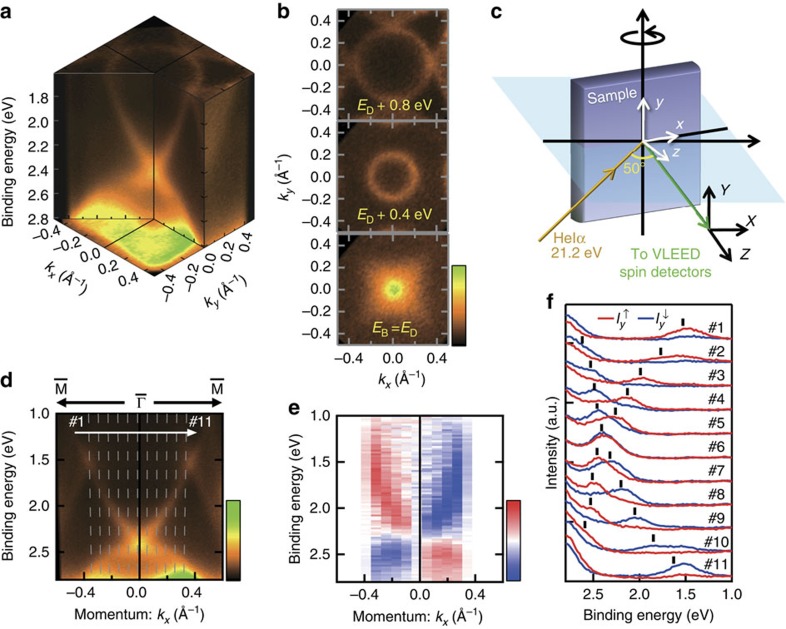

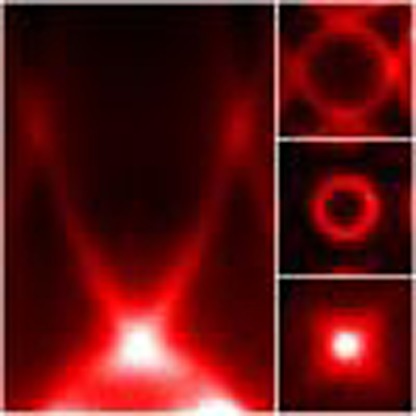

Now we focus on the observed surface Dirac-cone band. The close-up of the surface Dirac cone is demonstrated in Fig. 3a, indicating its crossing point at EB=ED=2.41 eV (ED: the energy of Dirac point where the bands cross each other). Such a clear Dirac-cone-shaped band strongly reminds us of the helical edge states in three-dimensional (3D) strong topological insulators. We can see the very isotropic character of surface Dirac cone in its constant-energy cuts (Fig. 3b), appearing as the perfectly circular-shaped contour even at EB=ED–0.8 eV with a large momentum radius of 0.3 Å−1. It is in contrast to the warping effect often appearing in trigonal strong topological insualtors27,28. The spin polarization of surface Dirac cone is also directly confirmed by SARPES experiments as depicted in Fig. 3c (ref. 29). Figure 3e,f shows the results for the y-component spin, measured along kx ( –

– ). Because of C4v symmetry, x- and z-components are forbidden (Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The red (blue) curves in Fig. 3f, indicating the energy distribution curves of spin-up (-down) components, clearly show the spin-polarized band dispersions. As easily seen in the SARPES image (Fig. 3e), the spin polarization with spin-up (spin-down) for negative (positive) dispersion of surface Dirac cone is confirmed. The observed spin-polarized surface Dirac cone thus presents a strong resemblance to the helical surface state in strong topological insulators.

). Because of C4v symmetry, x- and z-components are forbidden (Supplementary Note 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The red (blue) curves in Fig. 3f, indicating the energy distribution curves of spin-up (-down) components, clearly show the spin-polarized band dispersions. As easily seen in the SARPES image (Fig. 3e), the spin polarization with spin-up (spin-down) for negative (positive) dispersion of surface Dirac cone is confirmed. The observed spin-polarized surface Dirac cone thus presents a strong resemblance to the helical surface state in strong topological insulators.

Figure 3. Band dispersion and spin polarization of surface Dirac-cone band.

(a) Close-up of the observed surface Dirac-cone dispersions. (b) Constant-energy cuts at the binding energies (EB) of EB=ED+0.8 eV, ED+0.4 eV and ED (=2.41 eV), respectively, where ED is the band crossing point of the surface Dirac cone. The colour scale indicates the intensity. (c) Schematic of spin- and angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (SARPES) experimental geometry using the HeIα light source (21.2 eV) and very-low-energy electron diffraction (VLEED) spin detectors. (d) Intensity image of the surface Dirac cone along  –

– . The colour scale indicates the intensity. Grey lines (#1–11) represent the measurement cuts for energy distribution curves (EDC) shown in f. (e) Spin-resolved image of the surface Dirac-cone dispersions for spin y-component. The colour scale indicates the spin polarization Py, from Py=−1 (blue) to Py=+1 (red). (f) Spin-resolved EDCs for momenta #1–11 as shown in d, respectively. Red (blue) curves show the spin-up (spin-down) component of the intensity,

. The colour scale indicates the intensity. Grey lines (#1–11) represent the measurement cuts for energy distribution curves (EDC) shown in f. (e) Spin-resolved image of the surface Dirac-cone dispersions for spin y-component. The colour scale indicates the spin polarization Py, from Py=−1 (blue) to Py=+1 (red). (f) Spin-resolved EDCs for momenta #1–11 as shown in d, respectively. Red (blue) curves show the spin-up (spin-down) component of the intensity,  (

( ). The black markers denote the peak positions of the EDC in d.

). The black markers denote the peak positions of the EDC in d.

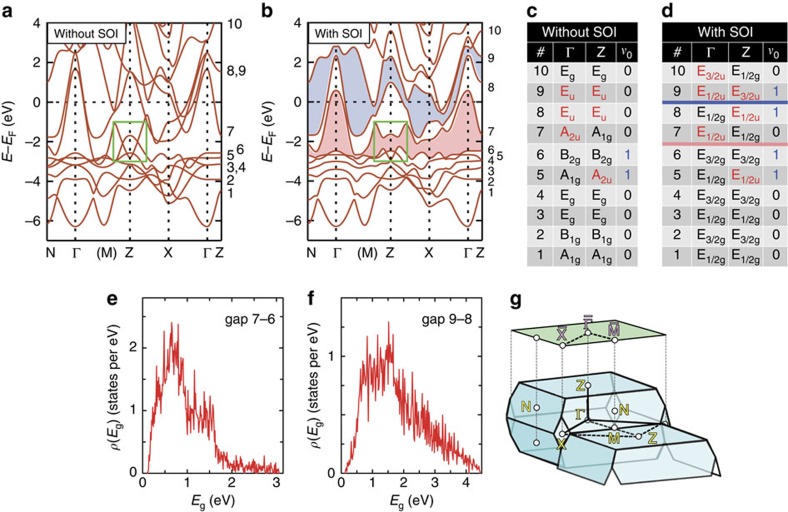

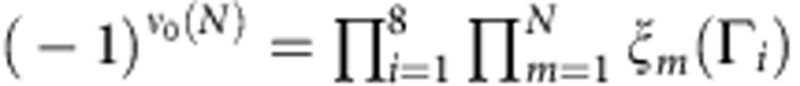

Analysis of the topological invariant

To evaluate whether the observed surface state is topologically non-trivial, we derive the Z2 invariant ν0 for β-PdBi2, in analogy to 3D strong topological insulators30. For 3D band insulators with inversion symmetry, ν0 obtained from the parity eigenvalues of filled valence bands at eight time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) classifies whether it is a strong topological insulator (ν0=1) or not (ν0=0). The bulk β-PdBi2 is apparently a metal; nevertheless, here we define a gap in which there is no crossing of the bulk band dispersions through the entire Brillouin zone. By considering this gap, we discuss its topological aspect by calculating ν0. The calculated bulk bands without and with SOI are shown in Fig. 4a,b, respectively. The valence bands are identified by numbers (from 1st to 10th) as indicated on the right side of respective graphs. The bands are numbered by the energy (E) at the Z point. Note that all bands are doubly spin-degenerate. By comparing Fig. 4a,b, we notice that many anticrossings are introduced by SOI, including the ∼0.55 eV gap opening in the green rectangle region where the surface Dirac cone appears. Here we focus on the gap between the 7th and 6th bulk bands, namely gap 7−6, shaded by pink in Fig. 4b. The distribution of the direct gap between the 7th and 6th bands can be evaluated by the joint density of states as a function of the gap energy Eg, defined as  . Here, E6(k) and E7(k) represent the respective eigenenergies of the 6th and 7th bands at momentum k with k=(kx, ky, kz). The result for gap 7−6 is shown in Fig. 4e, which guarantees the minimum value of 0.105 eV gap opening between the 7th and 6th bands through the entire Brillouin zone.

. Here, E6(k) and E7(k) represent the respective eigenenergies of the 6th and 7th bands at momentum k with k=(kx, ky, kz). The result for gap 7−6 is shown in Fig. 4e, which guarantees the minimum value of 0.105 eV gap opening between the 7th and 6th bands through the entire Brillouin zone.

Figure 4. Analysis of parity and topological invariant for valence bands.

(a,b) First-principles band calculations without and with spin–orbit interaction (SOI), respectively. Valence bands are numbered by the energy (E) at the Z point, as shown in the right side of the panels. The green rectangles indicate the energy region where the surface Dirac cone appears. Pink (blue)-shaded area in b shows gap 7−6 (gap 9−8) induced by SOI. (c,d) Lists of the topological invariant ν0 and the symmetries of wavefunctions at the Γ and Z points without and with SOI, respectively. The left-end columns (#) indicate the number of the valence bands as given in a and b, respectively. The symmetries indicated with red (black) have the odd (even-) parity. ν0=1 indicates the topologically non-trivial band-inverted state. The pink (blue) line in d denotes the gap 7−6 (gap 9−8). (e,f) The distribution of the direct gap (Eg) for gap 7−6 and gap 9−8, respectively, obtained by the band calculation. (g) The blue solid (green plane) indicates the three (two)-dimensional Brillouin zone with high-symmetry points Γ, Z, N, X and M ( ,

,  and

and  ). Γ, Z, N and X are the three-dimensional time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM).

). Γ, Z, N and X are the three-dimensional time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM).

By considering the obtained gap, we discuss its topological aspect by calculating ν0 in analogy to 3D strong topological insulators. As shown in Fig. 4g, the eight TRIM in the Brillouin zone of β-PdBi2 with I4/mmm symmetry are Γ, Z, two X and four N points. Considering these TRIM, Z2 invariant for the gap between the (N+1)-th and N-th bulk bands, ν0(N), can be calculated by  , where

, where  represents the parity eigenvalue (±1) of the m-th band at i-th TRIM. Note that since there are even numbers of X and N points, only Γi=Γ and Z contribute to the calculation of ν0(N), that is,

represents the parity eigenvalue (±1) of the m-th band at i-th TRIM. Note that since there are even numbers of X and N points, only Γi=Γ and Z contribute to the calculation of ν0(N), that is,  . Thus, ν0 can be calculated by considering solely Γ and Z points, whose symmetries of wavefunctions are listed in Fig. 4d for respective bands. Those indicated by red (black) is of odd (even) parity. We find that gap 7−6 is characterized by ν0(6)=1, indicating its analogy to 3D strong topological insulators. This requires an odd number of surface states connecting the 7th and 6th bands, to topologically link the bulk β-PdBi2 and a vacuum. The observation of spin-helical surface Dirac cone in gap 7−6 clearly represents the characters of such topologically protected surface states.

. Thus, ν0 can be calculated by considering solely Γ and Z points, whose symmetries of wavefunctions are listed in Fig. 4d for respective bands. Those indicated by red (black) is of odd (even) parity. We find that gap 7−6 is characterized by ν0(6)=1, indicating its analogy to 3D strong topological insulators. This requires an odd number of surface states connecting the 7th and 6th bands, to topologically link the bulk β-PdBi2 and a vacuum. The observation of spin-helical surface Dirac cone in gap 7−6 clearly represents the characters of such topologically protected surface states.

Topological surface state crossing E F

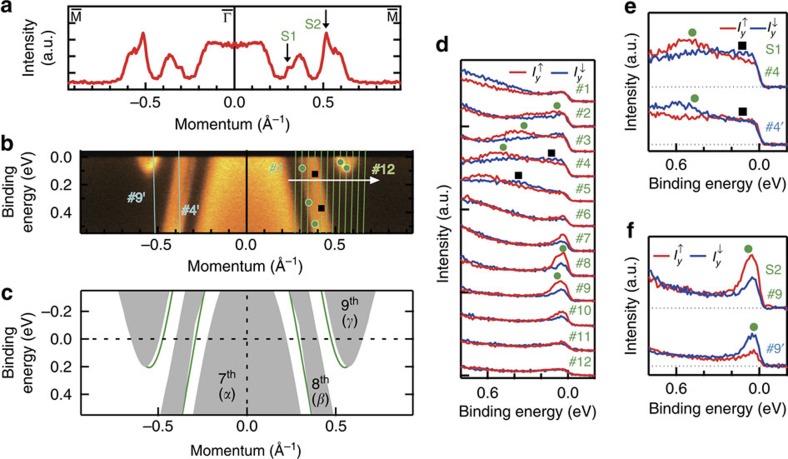

By further looking at the list of ν0 in Fig. 4d, we notice ν0(8)=1 for gap 9−8 shaded by blue in Fig. 4b, which has a minimum gap of 0.127 eV as confirmed by the calculation (Fig. 4f). It suggests that the topological surface states connecting the 9th and 8th bands must exist, where we may observe the effect of superconductivity if located close enough to EF. To clarify this possibility, the close-up of ARPES image near EF is shown with the calculation in Fig. 5b,c. The green curves in Fig. 5c indicate the calculated surface states crossing EF separately from the 2D projected bulk bands shaded by grey. They appear at the smaller-kx side of β (8th) and γ (9th) bands. Experimentally, the sharp peaks indicative of 2D surface states are observed in momentum distribution curve at EF, as denoted by S1 and S2 in Fig. 5a. As can be seen in the list of ν0 in Fig. 4d, S2 should be the topological surface state connecting the 9th and 8th bands, whereas S1 appearing in gap 8−7 must be trivial.

Figure 5. Spin-polarized surface states crossing the Fermi level.

(a–c) Momentum distribution curve obtained by integrating the intensity in the energy window of ±10 meV at the Fermi level, the intensity image and the calculation, respectively, shown along  –

– . The black arrows in a indicate the intensities from two different surface bands denoted by S1 and S2. Green circles (black squares) depicted in b are the peak positions of energy- and momentum-distribution curves for surface (bulk) bands. In c, surface band dispersions (green) are overlaid to two-dimensional projected bulk bands (grey), namely the 7th (α), 8th (β) and 9th (γ) bands. (d) Spin-resolved spectra recorded at momenta #1–12, as shown in b, respectively. (e,f) Spin-resolved spectra for S1 at momenta #4 and #4′ in b, and for S2 at momenta #9 and #9′ in b, respectively. Red (blue) curves in d–f show the spin-up (spin-down) component of the intensity for spin-y,

. The black arrows in a indicate the intensities from two different surface bands denoted by S1 and S2. Green circles (black squares) depicted in b are the peak positions of energy- and momentum-distribution curves for surface (bulk) bands. In c, surface band dispersions (green) are overlaid to two-dimensional projected bulk bands (grey), namely the 7th (α), 8th (β) and 9th (γ) bands. (d) Spin-resolved spectra recorded at momenta #1–12, as shown in b, respectively. (e,f) Spin-resolved spectra for S1 at momenta #4 and #4′ in b, and for S2 at momenta #9 and #9′ in b, respectively. Red (blue) curves in d–f show the spin-up (spin-down) component of the intensity for spin-y,  (

( ). Green circles (black squares) depicted in d–f are identical to those in b.

). Green circles (black squares) depicted in d–f are identical to those in b.

The spin polarization of the topological surface state S2 as well as the trivial surface state S1 is also confirmed experimentally. As shown in Fig. 5d, the y-oriented spin polarizations of S1 (#2–5) and S2 (#7–10) along kx ( –

– ) are clearly observed in the spin-resolved spectra. Here, the peak positions for S1 and S2 (bulk β) bands are depicted by green circles (black squares). We can see that S1 and S2 are both spin-polarized with spin-up for kx>0, whereas they get inverted for kx<0 (Fig. 5e,f) as required by the time-reversal symmetry. These clearly indicate that both topological and trivial surface states crossing EF possess the in-plane spin polarizations.

) are clearly observed in the spin-resolved spectra. Here, the peak positions for S1 and S2 (bulk β) bands are depicted by green circles (black squares). We can see that S1 and S2 are both spin-polarized with spin-up for kx>0, whereas they get inverted for kx<0 (Fig. 5e,f) as required by the time-reversal symmetry. These clearly indicate that both topological and trivial surface states crossing EF possess the in-plane spin polarizations.

Discussion

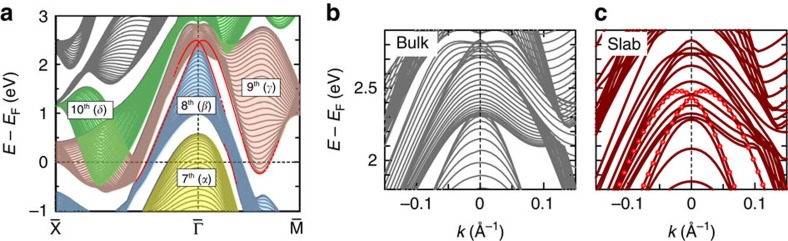

The Z2 analysis shows that odd number of gapless surface states in gap 9−8, connecting the 9th and 8th bands, must exist between  and

and  . To confirm whether the experimentally observed S2 indeed corresponds to this topological surface state, we need to carefully look at the slab calculation since S2 crosses EF and extends to the unoccupied state. By tracking the calculated data from

. To confirm whether the experimentally observed S2 indeed corresponds to this topological surface state, we need to carefully look at the slab calculation since S2 crosses EF and extends to the unoccupied state. By tracking the calculated data from  towards

towards  (Fig. 6a), we first notice that S2 is derived from the local minimum of the 9th (γ) band. S2 then crosses EF and reaches up to E–EF=2 eV without merging into the bulk states. At

(Fig. 6a), we first notice that S2 is derived from the local minimum of the 9th (γ) band. S2 then crosses EF and reaches up to E–EF=2 eV without merging into the bulk states. At  , although it gets overlapped with 2D projected bulk bands, we can distinguish S2 forming a Rashba-like crossing point at E–EF=2.4 eV. After the crossing, S2 band eventually gets merged into the 8th (β) band. It thus shows that S2 indeed connects the 9th and 8th bands. The crossing of S2 surface band at

, although it gets overlapped with 2D projected bulk bands, we can distinguish S2 forming a Rashba-like crossing point at E–EF=2.4 eV. After the crossing, S2 band eventually gets merged into the 8th (β) band. It thus shows that S2 indeed connects the 9th and 8th bands. The crossing of S2 surface band at  is more clearly seen, by comparing the 2D projected bulk (Fig. 6b) and the slab (Fig. 6c) calculations magnified near the crossing point. The crossing of the S2 surface band at

is more clearly seen, by comparing the 2D projected bulk (Fig. 6b) and the slab (Fig. 6c) calculations magnified near the crossing point. The crossing of the S2 surface band at  is distinguished in Fig. 6c, by following the eigenenergies highlighted with the red markers. Note that no such crossing exists for the calculation of bulk in Fig. 6b. S2 thus possesses a similarity to the Dirac cone that connects the gap with the crossing at

is distinguished in Fig. 6c, by following the eigenenergies highlighted with the red markers. Note that no such crossing exists for the calculation of bulk in Fig. 6b. S2 thus possesses a similarity to the Dirac cone that connects the gap with the crossing at  , and is indeed a topologically protected surface state.

, and is indeed a topologically protected surface state.

Figure 6. Band crossing of the topological surface state.

(a) Two-dimensional projected bulk bands and the surface state bands obtained by the calculation. The energy (E) relative to the Fermi level (EF) is plotted along  –

– and

and  –

– . Those crossing the Fermi level are painted by colours; yellow for 7th (α), blue for 8th (β), pink for 9th (γ) and green for the 10th (δ) bands. The surface state bands crossing the Fermi level are depicted by the red curves. (b,c) The calculated band dispersions for the bulk PdBi2 and for the slab of 11 PdBi2 layers, respectively, magnified near the band crossing point. E–EF for respective bands are plotted as a function of momentum k. The bands at the topmost surface are highlighted by red markers in c.

. Those crossing the Fermi level are painted by colours; yellow for 7th (α), blue for 8th (β), pink for 9th (γ) and green for the 10th (δ) bands. The surface state bands crossing the Fermi level are depicted by the red curves. (b,c) The calculated band dispersions for the bulk PdBi2 and for the slab of 11 PdBi2 layers, respectively, magnified near the band crossing point. E–EF for respective bands are plotted as a function of momentum k. The bands at the topmost surface are highlighted by red markers in c.

Here we note that the spin-polarized topological S2 and the surface Dirac cone are both derived as a consequence of SOI, but in different processes. For the case of S2 in gap 9−8, we see that ν0 changes to 1 by including the SOI. It thus indicates the band inversion associated with the 8th, 9th and 10th bands occurring at Γ (see Fig. 4c,d) induced by the SOI. This situation is fairly similar to the topological phase transition being discussed in 3D strong topological insulators31. For the surface Dirac cone in gap 7−6, on the other hand, ν0=1 is realized already in the non-relativistic case (Fig. 4c), due to the inversion of A1g and A2u bands introduced by Bi6p–Pd4d mixing. This non-relativistic situation should be rather similar to the 3D Dirac semimetals32,33, as represented by the bulk Dirac points appearing along Z–M and Z–X (Fig. 4a), which may accompany the spin-degenerate surface states (Fermi arcs). The role of the SOI in this case is the gap opening at these bulk Dirac points, giving rise to the spin-polarized surface Dirac cone connecting the gap edges.

The next future step for β-PdBi2 should be the direct elucidation of the superconducting state. Low-temperature ultrahigh-resolution ARPES will surely be a strong candidate for such investigation34,35. There may be a chance to observe non-trivial superconducting excitations, by selectively focusing on the surface and bulk band dispersions as experimentally presented in Bi2Se3/NbSe2 thin film34. Scanning tunnelling microscope/spectroscopy, on the other hand, can locally probe the superconducting state around the vortex cores. As theoretically suggested, it may capture the direct evidence of Majorana mode4,11,36,37. We should note that β-PdBi2 will also provide a solid platform for bulk measurements such as thermal conductivity and nuclear magnetic resonance, which are expected to give some information on the odd-parity superconductivity18,19. It may thus contribute to making the realm of superconducting topological materials, and pave the way to various new findings such as the direct observation of Majorana fermions dispersion and/or surface Andreev bound states36,37, clarification of its relation to the possible odd-parity superconductivity11,17 and bulk-surface mixing effect36,38.

Methods

Crystal growth

Single crystals of β-PdBi2 were grown by a melt growth method. Pd and Bi at a molar ratio of 1:2 were sealed in an evacuated quartz tube, pre-reacted at high temperature until it completely melted and mixed. Then, it was again heated up to 900 °C, kept for 20 h, cooled down at a rate of 3 °C h−1 down to 500 °C and rapidly quenched into cold water. The obtained single crystals had good cleavage, producing flat surfaces as large as ∼1 × 1 cm2. The resistivity shown in Fig. 1b and the magnetic susceptibility shown in Fig. 1c exhibit the clear superconducting transition at Tc=5.3 K.

Angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES)

ARPES measurement with the HeIα light source (21.2 eV) were made at the Department of Applied Physics, The University of Tokyo, using a VUV5000 He-discharge lamp and an R4000 hemispherical electron analyzer (VG-Scienta). The total energy resolution was set to 10 meV. Samples were cleaved in situ at around room temperature and measured at 20 K.

Spin- and angular-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (SARPES)

SARPES with the HeIα light source (21.2 eV) was performed at the Efficient SPin REsolved SpectroScOpy (ESPRESSO) end station attached to the APPLE-II-type variable polarization undulator beamline (BL-9B) at the Hiroshima Synchrotron Radiation Center (HSRC)29. The analyzer of this system consists of two sets of very-low-energy electron diffraction spin detectors, thus enabling the detection of the electron spin orientation in three dimension39. The angular resolution was set to ±1.5° and the total energy resolution was set to 35 meV. Samples were cleaved in situ at around room temperature and measured at 20 K.

Band calculations

First-principles electronic structure calculations within the framework of the density functional theory were performed using the full-potential linearized augmented plane-wave method as implemented in the WIEN2k code40, with the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof exchange-correlation function41. SOI was included as a second variational step with a basis of scalar-relativistic eigenfunctions.

The experimental crystal data (a=3.362 Å, c=12.983 Å, z(Bi)=0.363) were used for the bulk calculations. The (001) surface was simulated by a slab model; a stacking of 11 PdBi2-triple layers along the c axis with a 15 Å of vacuum layer, forming a tetragonal crystal structure of space group P4/mmm with the lattice constants of a=3.362 Å and c=83.423 Å.

The plane-wave cutoff energy was set to RMTKmax=9, where the muffin tin radii are RMT=2.5 a.u. for both Bi and Pd. The Brillouin zone was sampled with the Monkhorst-Pack scheme42 with momentum grids finer than Δk=0.02 Å−1 (for example, a Γ-centred 38 × 38 × 38 k-point mesh was used for the Fermi surface visualization, corresponding to Δk=0.009 Å−1).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sakano, M. et al. Topologically protected surface states in a centrosymmetric superconductor β-PdBi2. Nat. Commun. 6:8595 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9595 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Arita for fruitful discussion, A. Kimura, H. Namatame and M. Taniguchi for sharing SARPES infrastructure. M.S. is supported by Advanced Leading Graduate Course for Photon Science (ALPS). M.S., K.O. and M.K. are supported by a research fellowship for young scientists from JSPS. This research was partly supported by Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO), Japan Science and Technology Agency; the Photon Frontier Network Program of the MEXT; Research Hub for Advanced Nano Characterization, The University of Tokyo, supported by MEXT, Japan; and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS, Japan (KAKENHI Kiban-B 24340078 and Kiban-A 23244066). The experiments were approved by the Proposal Assessing Committee of the Hiroshima Synchrotron Radiation Center (Proposal No. 14-B-7).

Footnotes

Author contributions M.S. and H.S. carried out ARPES. M.S., T.O. and K.I. carried out SARPES. K.O., M.K. and T.S. synthesized and characterized the single crystals. T.S. carried out the calculations. M.S. and K.I. analysed (S)ARPES data and wrote the manuscript with input from K.O., M.K., T.O. and T.S. K.I. conceived the experiment. All authors contributed to the scientific discussions.

References

- Hasan M. Z. & Kane C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Qi X.-L. & Zhang S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder A. P., Ryu S., Furusaki A. & Ludwig A. W. W. Classification of topological insulators and superconductors in three spatial dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 78, 195125 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. & Kane C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczek F. Majorana returns. Nat. Phys. 5, 614–618 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Sato M. & Nagaosa N. Symmetry and topology in superconductors: odd-frequency pairing and edge states. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 81, 011013 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Alicea J. New directions in the pursuit of Majorana fermions in solid state systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 075602 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenakker C. W. J. Search for Majorana fermions in superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 113–116 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hor Y. S. et al. Superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 and its Implications for Pairing in the Undoped Topological Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 057001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriener M., Segawa K., Ren Z., Sasaki S. & Ando Y. Bulk superconducting phase with a full energy gap in the doped topological insulator CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 127004 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. & Berg E. Odd-parity topological superconductors: theory and application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S. et al. Topological superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S. et al. Odd-parity pairing and topological superconductivity in a strongly spin-orbit coupled semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 217004 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. L. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in topological parent compound Bi2Te3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 24–28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. et al. Superconductivity in topological insulator Sb2Te3 induced by pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 2016 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N. et al. Experimental evidence for s-wave pairing symmetry in superconducting CuxBi2Se3 single crystals using a scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 117001 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima T., Yamakage A., Sato M. & Tanaka Y. Dirac-fermion-induced parity mixing in superconducting topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 90, 184516 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zocher B. & Rosenow B. Surface states and local spin susceptibility in doped three-dimensional topological insulators with odd-parity superconducting pairing symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155138 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Nakamura H. & Machida M. Rotational isotropy breaking as proof for spin-polarized Cooper pairs in the topological superconductor CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 86, 094507 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. et al. Half-Heusler ternary compounds as new multifunctional experimental platforms for topological quantum phenomena. Nat. Mater. 9, 546–549 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. Metallic surface electronic state in half-Heusler compounds RPtBi (R=Lu, Dy, Gd). Phys. Rev. B 83, 205133 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., de Groot R. A. & van der Lugt W. The electrical resistivities of liquid Pd-Bi alloys and the band structure of crystalline beta-PdBi2 and PdBi. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 4, 2389–2395 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y. et al. Superconductivity at 5.4 K in β-Bi2Pd. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 81, 113708 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Shein I. R. & Ivanovskii A. L. Electronic band structure and Fermi surface of tetragonal low-temperature superconductor Bi2Pd as predicted from first principles. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 26, 1–4 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mondal M. et al. Andreev bound state and multiple energy gaps in the noncentrosymmetric superconductor BiPd. Phys. Rev. B 86, 094520 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. et al. Dirac surface states and nature of superconductivity in noncentrosymmetric BiPd. Nat. Commun. 6, 6633 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. L. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional topological insulator, Bi2Te3. Science 325, 178–181 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. Hexagonal warping effects in the surface states of the topological insulator Bi2Te3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 266801 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T. et al. Efficient spin resolved spectroscopy observation machine at Hiroshima Synchrotron Radiation Center. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 103302 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L. & Kane C. L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045302 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.-Y. et al. Topological phase transition and texture inversion in a tunable topological insulator. Science 332, 560–564 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane M. et al. Observation of a three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal phase in high-mobility Cd3As2. Nat. Commun. 5, 3786 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. K. et al. A stable three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 13, 677–681 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K. et al. Octet-line node structure of superconducting order parameter in KFe2As2. Science 337, 1314–1317 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.-Y. et al. Momentum-space imaging of Cooper pairing in a half-Dirac-gas topological superconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 943–950 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Hosur P., Ghaemi P., Mong R. S. K. & Vishwanath A. Majorana modes at the ends of superconductor vortices in doped topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 097001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh T. H. & Fu L. Majorana fermions and exotic surface Andreev bound states in topological superconductors: application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 107005 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman D. L. & Refael G. Bulk metals with helical surface states. Phys. Rev. B 82, 195417 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T., Miyamoto K., Kimura A., Namatame H. & Taniguchi M. A double VLEED spin detector for high-resolution three dimensional spin vectorial analysis of anisotropic Rashba spin splitting. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 201, 23–20 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Blaha P., Schwarz K., Sorantin P. & Trickey S. B. Full-potential, linearized augmented plane wave programs for crystalline systems. Comp. Phys. Commun. 59, 399–415 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Burke K. & Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkhorst H. J. & Pack J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary References