Abstract

Background

Mutations in the CACNA1A gene encoding the voltage-gated calcium channel α1A subunit have been identified in patients with autosomal dominantly inherited neurological disorders, including spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) and familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1). In order to investigate the underlying pathogenesis common to these distinct phenotypic disorders, this study investigated the neuronal function of the GABAergic system and glucose metabolism in vivo using positron emission tomography (PET).

Methods

Combined PET studies with [11C]-flumazenil and [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) were performed in three FHM1 patients and two SCA6 patients. [18F]-FDG-PET using a three-dimensional stereotactic surface projection analysis was employed to measure the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRGlc). In addition, the GABA-A receptor function was investigated using flumazenil, a selective GABA-A receptor ligand.

Results

All patients displayed a significant decrease in CMRGlc and low flumazenil binding in the cerebellum compared with the normal controls. The flumazenil binding in the temporal cortex was also decreased in two FHM1 patients.

Conclusions

Cerebellar glucose hypometabolism and an altered GABA-A receptor function are characteristic of FHM1 and SCA6.

General significance

An altered GABA-A receptor function has previously been reported in models of inherited murine cerebellar ataxia caused by a mutation in the CACNA1A gene. This study showed novel clinical characteristics of alteration in the GABA-A receptor in vivo, which may provide clinical evidence indicating a pathological mechanism common to neurological disorders associated with CACNA1A gene mutation.

Keywords: GABA-A, CACNA1A, PET, SCA6, FHM1, Flumazenil

Highlights

-

•

Functional brain imaging was studied in the CACNA1A gene associated diseases.

-

•

PET study was performed on SCA6 and FHM1 patients caused by the CACNA1A mutations.

-

•

All patients showed cerebellar GABA-A receptor impairment and glucose hypometabolism.

-

•

GABA-A receptor impairment in the temporal cortex was observed in the FHM1 patients.

-

•

GABA-A receptor alteration may be characteristic of neurological diseases caused by the CACNA1A mutations.

1. Introduction

Neuronal Ca2 + plays a role in various neuronal pathways for excitability and neurotransmitter release and is regulated by calcium-permeable channels and calcium binding proteins. Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) help to regulate neuronal Ca2 + and function as heteromultimeric complexes that mediate calcium influx into cells in response to changes in the membrane potential. The α1A subunit, encoded by the CACNA1A gene, is a pore-forming structure specific to the brain specific P/Q-type VGCC, which is diffusedly expressed in the brain, especially in the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum [1].

Mutations in the CACNA1A gene have been identified in autosomal dominantly inherited human neurological disorders, including spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6), episodic ataxia 2 (EA2) and familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1) [2]. SCA6 is caused by small expansions in the CAG repeat at the 3′ end of the CACNA1A gene, while EA2 and FHM1 are the result of point mutations in the CACNA1A gene. The phenotypes of FHM1 exhibit remarkable variation, including episodic neurological symptoms, such as seizures, transient blindness and permanent neurological symptoms of cerebellar ataxia [3], [4]. Phenotypic variation is also observed in patients with specific CACNA1A gene mutations and family members with a single mutation [4], [5]. Cerebellar ataxia is the most frequently observed phenotype in FHM1 patients, and some FHM1 patients develop ataxia as the only neurological sign, without migraines [3], [6]. Therefore, cerebellar signs are clinically indistinguishable in cases of FHM1 and SCA6.

Several inherited mouse neurological disorders can be caused by the CACNA1A gene. Mutations at the orthologous site of the mouse CACNA1A gene induce a group of recessive neurological disorders, including the tottering phenotypes with ataxia and absence epilepsy, as well as the rolling Nagoya phenotype with ataxia without seizures [2]. These mice have been suggested to therefore be appropriate as an animal model of human spinocerebellar ataxia, and recent studies of these animals have demonstrated an abnormal glutamic acid to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor function and expression in the cerebellar and cerebral cortices resulting from an abnormal P/Q type VGCC activity [7], [8], [9], [10]. These findings led us to speculate that the GABA-A receptor function may also be compromised in patients with SCA6 and FHM1. This study therefore investigated the neuronal function of the GABAergic system using positron emission tomography (PET) with a radioligand, [11C]-flumazenil, that binds selectively to the GABA-A receptor and evaluated brain glucose metabolism using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in FHM1 and SCA6 patients. We herein describe functional GABA-A receptor alterations in patients with the CACNA1A gene mutation.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

After obtaining permission from the local ethics committee and written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki, three FHM1 patients (one male and two females) and two SCA6 patients (one male and one female) were included in this study.

Neurological specialists excluded other possible causes of cerebellar ataxia, including infection, other autoimmune conditions, vitamin deficiencies, cerebrovascular diseases and neoplasms. FHM1 was diagnosed based on clinical criteria published by the International Classification of Headache Disorders [11]. The degree of cerebellar ataxia was evaluated using a uniform clinical examination with a scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) [12]. All patients underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after the initial presentation of symptoms.

2.2. Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the leukocytes of the subjects' family members using a DNA Isolation kit (WAKO, JAPAN). Primers corresponding to the intronic sequences flanking the exons of the CACNA1A gene were designed using the Primer3 software program. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with the GoTaq system (Promega, USA) under standard conditions. The PCR products were purified with ExoSAP (USB, USA) and sequenced for both forward and reverse strands using the BigDye Terminator chemistry version 3 kit according to the standard protocol (Applied Biosystems, CA). Sequences were subsequently obtained using the ABI Genetic Analyzer 3100 (Applied Biosystems) with the sequence analysis software program GENETYX, ver. 9 (GENETYX, JAPAN).

2.3. PET imaging

The FDG-PET studies were performed with the patient in a resting state with his or her eyes open under a dim light following the intravenous injection of 185 MBq [18F]-FDG. All scans were realigned to the anterior–posterior commissure line and spatially normalized to the Talairach and Tournoux atlas using an affine transformation with 12 parameters, followed by nonlinear warping. This process yielded a standardized image set with 2.25 mm voxels. The spatially normalized FDG-PET scan for each subject was compared with a normative reference database generated from the FDG-PET scans of normal individuals. Each scan was compared with the database after controlling the global activity using Neurostat scaling procedures. Z scores (Z 5 [mean subject − mean database] / SD database) were calculated voxel-by-voxel at a threshold of P < 0.01 (one-sided) corresponding to Z > 2.33 for a reduced 18F-FDG uptake in the patient relative to the control mean. Three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections (3D-SSPs) of the Z scores were then generated to allow for the visualization of 18F-FDG uptake abnormalities and an examination of the extent and topography of hypometabolism according to a previously described method [13].

The GABAergic system was examined using PET and [11C]-flumazenil an antagonistic radioligand that binds to the central benzodiazepine receptor site of the GABA-A complex. The flumazenil-PET study was performed with the patient in a resting state with his or her eyes open under a dim light following the intravenous injection of 5 MBq/kg of [11C]-flumazenil. The accumulation of flumazenil was recorded for 60 min using dynamic serial scanning. Prior to the PET scan, MRI (0.3-T MRP/7000 AD; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was performed with 3-dimensional mode sampling to determine the brain areas for setting the regions of interest (ROIs). Accordingly, ROIs were placed on the pons and cerebellum on MRI images then transferred onto the corresponding PET images, and the semiquantitative ROI/pons ratio was subsequently calculated by dividing the number of ROIs by the number of pons based on a previously described method [14]. Two different researchers calculated the ratios three times. Since flumazenil binding declines with age, we used age-matched controls for comparison to eliminate the effects of aging. The values for flumazenil binding were compared between the patients and normal controls.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and genetic outcomes

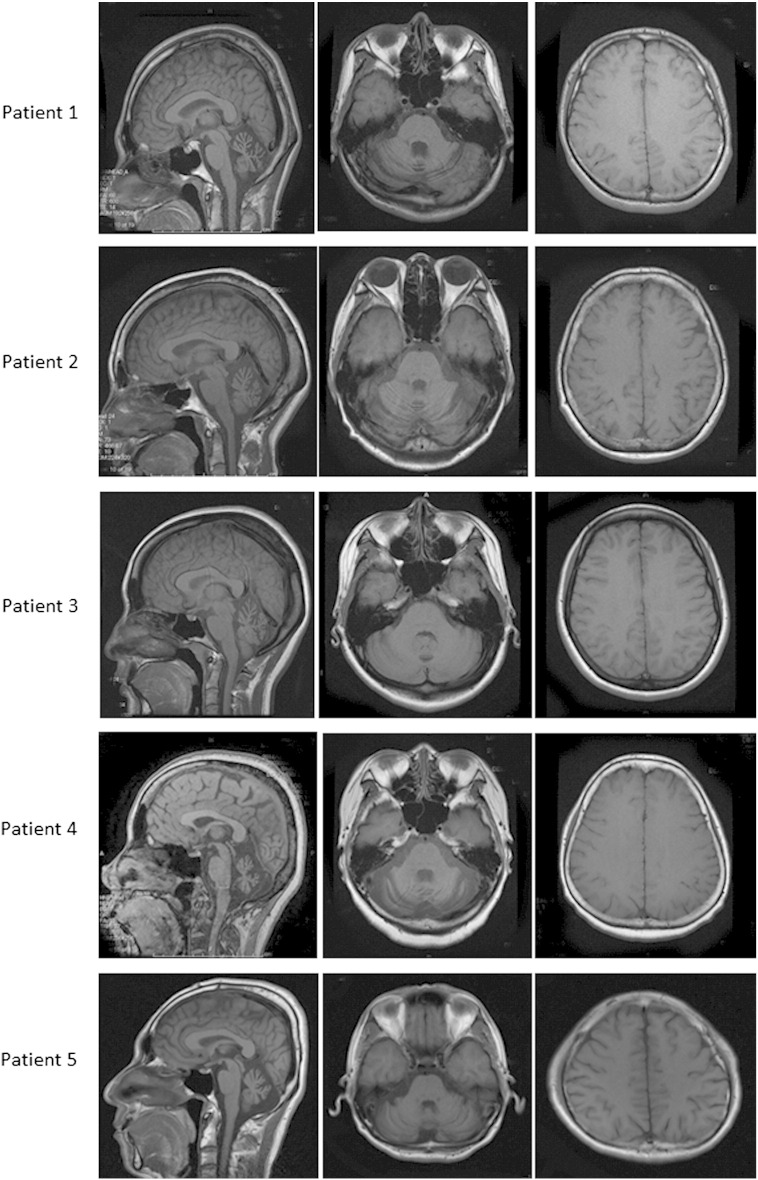

The clinical characteristics of each patient are summarized in Table 1. Patient 1, who was the mother of Patients 2 and 3, presented with hemiplegic migraines with progressive cerebellar ataxia lasting for approximately 20 years. Patients 2 and 3 presented with a several-year history of progressive cerebellar ataxia accompanied by migraines with visual and motor aura. A genetic analysis of the CACNA1A gene showed a homozygous R1347Q mutation (reference sequence: X99897) in all three patients, and they were diagnosed with FHM1. Patients 4 and 5 had also experienced cerebellar ataxia for approximately 20 years, although without migraines. These subjects were diagnosed with SCA6 based on a genetic analysis of the CACNA1A gene, which showed abnormal CAG expansion at the 3′ end of the CACNA1A gene. MRI disclosed symmetric cerebellar atrophy of the bilateral hemisphere and vermis in all patients (Fig. 1); however, no atrophy was noted in the cerebral cortices or brainstem. The SARA scores were in the range of 9 to 10 in all cases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients with CACNA1A mutations.

| Patient No./sex/age Phenotype |

Ataxia Age at onset (y) Progression |

SARA score | Migraine Age at onset (y) Type of aura |

CACNA1A gene mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/F/55 FHM1 |

35 Progressive |

10 | 13 Motor |

R1437Q/wt |

| 2/M/31 FHM1 |

22 Progressive |

9 | 9 Visual |

R1437Q/wt |

| 3/F/24 FHM1 |

20 Progressive |

9 | 12 Motor & visual |

R1437Q/wt |

| 4/M/48 SCA6 |

30 Progressive |

9 | (–) | (CAG)21/(CAG)10 |

| 5/F/54 SCA6 |

34 Progressive |

10 | (–) | (CAG)21/(CAG)10 |

CACNA1A reference sequence: X99897.

SARA: scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia.

wt: wild-type.

Fig. 1.

T1-weighted MRI images of the patients.

All patients showed cerebellar atrophy on axial and sagittal images, whereas cerebral atrophy was not observed.

3.2. PET analysis

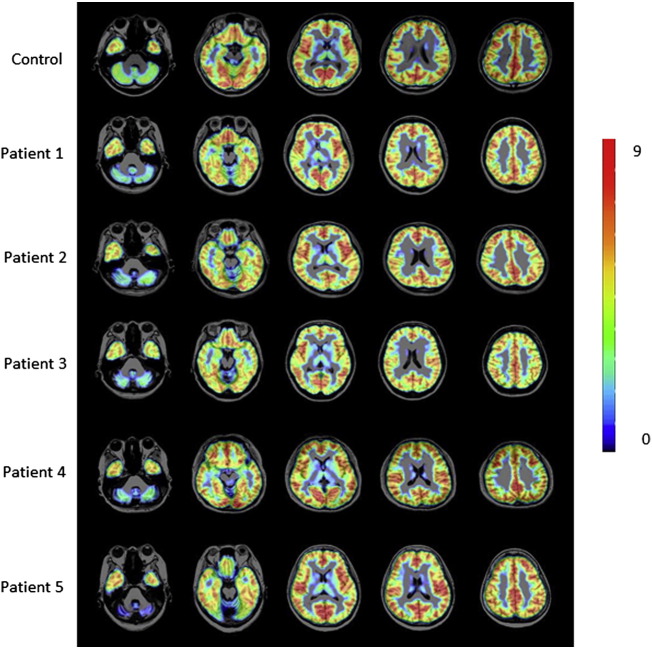

The flumazenil-PET analyses of the semi-quantitative ROI/pons ratio showed a significant reduction in flumazenil binding in the cerebellar vermis and bilateral cerebellar hemisphere in all patients, compared with that observed in the normal controls (Fig. 2, Table 2). The level of flumazenil binding in the temporal cortex was also decreased in FHM1 Patients 1 and 2.

Fig. 2.

Superimposed axial PET/MRI images of [11C]-flumazenil in the patients and an age-matched normal control. The colored bar denotes the [11C]-flumazenil standardized uptake value ratio. The red bar indicates flumazenil binding above the level of the blue bar.

Table 2.

Regional levels of binding potential for [11C]-flumazenil in the patients and controls.

| Controls N = 6 |

Patient 1 FHM |

Patient 2 FHM |

Patient 3 FHM |

Patient 4 SCA6 |

Patient 5 SCA6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right cerebellar hemisphere | 2.35 ± 0.20 | 1.71a | 1.34a | 1.42a | 1.61a | 0.98a |

| Left cerebellar hemisphere | 2.27 ± 0.15 | 1.71a | 1.31a | 1.47a | 1.65a | 1.02a |

| Cerebellar vermis | 2.60 ± 0.17 | 1.44a | 1.62a | 0.97a | 1.44a | 1.60a |

| Right frontal cortex | 3.21 ± 0.12 | 3.23 | 3.07 | 2.76a | 3.26 | 3.25 |

| Left frontal cortex | 3.20 ± 0.12 | 3.20 | 3.01 | 2.68a | 3.26 | 3.25 |

| Right temporal cortex | 3.26 ± 0.12 | 2.93a | 2.90a | 2.68a | 3.31 | 3.33 |

| Left temporal cortex | 3.22 ± 0.12 | 2.94a | 2.91a | 2.67a | 3.20 | 3.46 |

| Right parietal cortex | 3.34 ± 0.24 | 3.18 | 2.90 | 2.92 | 3.24 | 3.31 |

| Left parietal cortex | 3.30 ± 0.22 | 3.15 | 3.03 | 2.90 | 3.30 | 3.42 |

| Right occipital cortex | 3.10 ± 0.15 | 2.95 | 2.83 | 2.92 | 3.12 | 3.16 |

| Left occipital cortex | 3.11 ± 0.17 | 2.94 | 2.91 | 2.93 | 3.14 | 3.17 |

The data are presented as the mean ± SD.

The estimated [11C]-flumazenil binding was calculated as the region of interest (ROI)/pons ratio.

Below the range of mean–2 SD for normative data.

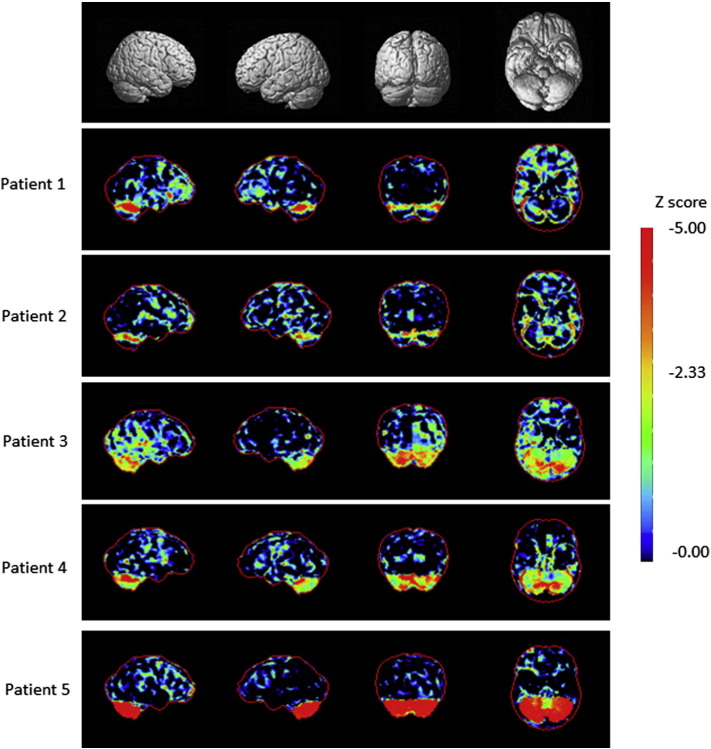

The metabolic rate of glucose (MRGlc) measured on FDG-PET was evaluated using a 3D-SSP analysis (Fig. 3). Consequently, all patients exhibited a significant decrease in the MRGlc in the bilateral cerebellar cortex, which presented with mild atrophy on MRI. The MRGlc was also reduced in the frontotemporal cortex in both the FHM1 and SCA6 patients.

Fig. 3.

3D-SSP analysis of the cortical [18F]-FDG PET patterns in the patients.

3D-SSP maps and corresponding Z scores showing metabolic rate of glucose reduction in the patients compared with that observed in the database of normal subjects are displayed on a color-coded scale ranging from black to red. The Z scores were calculated voxel-by-voxel at a threshold of P < 0.01 corresponding to Z > 2.33.

4. Discussion

GABA-A receptor impairment has been demonstrated in ataxic mice of the rolling mouse Nagoya and tottering mouse strains due to spontaneous CACNA1A gene mutations. However, no previous studies have investigated the GABA-A receptor function in human neurological diseases resulting from CACNA1A gene mutations. The rolling mouse Nagoya strain carries a point mutation in the voltage-sensing S4 segment of the third repeat of the α1 subunit encoded by the CACNA1A gene [15]. In these mice, the GABA receptor function assessed using a GABA receptor agonist is impaired in the cerebellum, thalamus, pons and medulla [7]. Meanwhile, tottering mice present with seizures and involuntary movements, as well as ataxia, and genetic analyses have revealed a point mutation in the CACNA1A gene encoding the pore-forming subunit of the P/Q type VGCC [16]. Furthermore, histochemical analyses in tottering mice have demonstrated a decreased number and impaired function of GABA-A receptors in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, in which aberrant GABA-A receptor subunits are expressed [8], [9], [10]. These findings led us to hypothesize that the GABA-A receptor may also be impaired in human neurological diseases associated with CACNA1A gene mutations. PET using [11C]-flumazenil, a radioactive ligand of the GABA-A receptor, is a useful neuroimaging modality for assessing the in vivo GABA-A receptor function in the living brain. However, there are no flumazenil-PET studies in patients with hereditary spinocerebellar ataxia, including SCA6 and FHM. In the present study, all patients with SCA6 and FHM1 displayed reduced flumazenil binding in the cerebellum, whereas decreased flumazenil binding in the temporal cortex was observed only in the FHM1 patients. These PET findings suggest that P/Q VGCC mutations contribute to impairment of the GABA-A receptor function, thus resulting in damage to the cerebellar GABAergic network, as previously observed in CACNA1A mutant ataxic mice. Mutant ataxic mice and cases of FHM1 in humans are caused by specific point mutations in the CACNA1A gene. In addition, biochemical studies in the mice brain show an aberrant GABA-A receptor expression in the cerebral cortex as well as cerebellum [8], [9], [17]. The characteristic finding of flumazenil-PET studies in FHM1 patients is regional decreased GABA-A receptor binding in the temporal cortex. The cerebrocortical GABA-A receptor impairment observed in FHM1 patients may be associated with pathological mechanisms caused by point mutations. However, it remains unclear how P/Q VGCC mutations induce dysfunction of the GABA-A receptor. Biochemical studies of tottering mice show the upregulation of cerebellar L-type voltage-activated calcium channel m-RNA, which may contribute to the dystonia observed in these animals [18]. L-type voltage-activated calcium channels regulate the GABA-A receptor expression in cultured neurons and cerebellar granule cells [19], [20]. Future pathological studies of the expression of GABA-A receptors and L-type voltage-activated calcium channels may provide clues to elucidating the pathological mechanisms underlying the development of CACNA1A-associated neurological diseases.

The present study demonstrated clinical characteristics common to FHM1 and SCA6. The regional patterns of brain hypometabolism obtained using a voxel-based analysis of FDG binding showed glucose hypometabolism in the frontotemporal cerebellar cortices as well as cerebellum in both the SCA6 and FHM1 patients. FDG-PET studies have been reported previously in SCA1, SCA2, SCA3 and SCA6 patients [21], [22]. Decreased regional glucose metabolism is found in the cerebellum in all SCA patients, while decreased glucose metabolism is observed in the brainstem in SCA1, SCA2, SCA3 and the basal nucleus of SCA3 [21], [22]. In SCA6 patients, glucose metabolism is diminished in the frontal and prefrontal cortices in addition to the cerebellum [22]. A previous FDG-PET study of FHM1 patients demonstrated hypometabolism in the frontotemporal cortex and cerebellum [23]. These previous FDG-PET findings are consistent with the PET features reported in this study.

Cerebella ataxia is an intriguing neurological sign, noted in two-thirds of FHM1 patients [4]. Some FHM1 patients develop ataxia with cerebellar atrophy prior to their first migraine attack, while others in various affected families show only cerebellar ataxia [3], [6]. In addition, some CACNA1A gene point mutations causing FHM1 may be associated with impairment of the cerebellar system. SCA6 is characterized by inherited neurodegeneration in the cerebellar system due to a mutation in the CACNA1A gene with expansion of the CAG repeats and may be categorized as a CAG repeat disorder. Recent molecular biological studies have revealed changes in the P/Q channel activity resulting in alterations in Ca2 + influx into cells transfected with the expanded CAG repeats in the CACNA1A gene causing SCA6 and missense mutations causing FHM1 [24], [25], [26]. These findings suggest that the pathological mechanisms of SCA6 have the potential to alter the P/Q VGCC activity, as well as induce a novel toxic gain of function, independent of the channel kinetics, as hypothesized for other CAG repeat diseases.

5. Conclusions

Neurological disorders associated with CACNA1A gene mutations have distinct clinical phenotypes. However, recent detailed clinical reports and molecular pathological studies have identified pathological mechanisms common to neurological disorders associated with CACNA1A gene mutation. The present PET study revealed glucose hypometabolism and GABA-A receptor dysfunction with novel clinical characteristics common to FHM1 and SCA6 patients, which may provide clinical evidence of pathological mechanisms caused by CACNA1A gene mutations.

Financial disclosures

This study was not sponsored by any else. All authors report no disclosures of financial relationships.

References

- 1.Westenbroek R.E., Sakurai T., Elliott E.M., Hell J.W., Starr T.V., Snutch T.P., Catterall W.A. Immunochemical identification and subcellular distribution of the alpha 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6403–6418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06403.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietrobon D. Calcium channels and channelopathies of the central nervous system. Mol. Neurobiol. 2002;25:31–50. doi: 10.1385/MN:25:1:031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducros A., Denier C., Joutel A., Cecillon M., Lescoat C., Vahedi K., Darcel F., Vicaut E., Bousser M.G., Tournier-Lasserve E. The clinical spectrum of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with mutations in a neuronal calcium channel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:17–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell M.B., Ducros A. Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:457–470. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barros J., Damasio J., Tuna A., Alves I., Silveira I., Pereira-Monteiro J., Sequeiros J., Alonso I., Sousa A., Coutinho P. Cerebellar ataxia, hemiplegic migraine, and related phenotypes due to a CACNA1A missense mutation: 12-year follow-up of a large Portuguese family. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:235–240. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi T., Igarashi S., Kimura T., Hozumi I., Kawachi I., Onodera O., Takano H., Saito M., Tsuji S. Japanese cases of familial hemiplegic migraine with cerebellar ataxia carrying a T666M mutation in the CACNA1A gene. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2002;72:676–677. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.5.676-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi T., Hayashi K., Murakami H., Maruyama S., Yamaguchi M. Distribution and characterization of the GABA receptors in the CNS of ataxic mutant mouse. Neurochem. Res. 1984;9:485–495. doi: 10.1007/BF00964375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tehrani M.H., Barnes E.M., Jr. Reduced function of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors in tottering mouse brain: role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Epilepsy Res. 1995;22:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tehrani M.H., Baumgartner B.J., Liu S.C., Barnes E.M., Jr. Aberrant expression of GABAA receptor subunits in the tottering mouse: an animal model for absence seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1997;28:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaja S., Hann V., Payne H.L., Thompson C.L. Aberrant cerebellar granule cell-specific GABAA receptor expression in the epileptic and ataxic mouse mutant, Tottering. Neuroscience. 2007;148:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz-Hubsch T., du Montcel S.T., Baliko L., Berciano J., Boesch S., Depondt C., Giunti P., Globas C., Infante J., Kang J.S., Kremer B., Mariotti C., Melegh B., Pandolfo M., Rakowicz M., Ribai P., Rola R., Schols L., Szymanski S., van de Warrenburg B.P., Durr A., Klockgether T., Fancellu R. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66:1717–1720. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219042.60538.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minoshima S., Frey K.A., Koeppe R.A., Foster N.L., Kuhl D.E. A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer's disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDG PET. J. Nucl. Med. 1995;36:1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosoi Y., Suzuki-Sakao M., Terada T., Konishi T., Ouchi Y., Miyajima H., Kono S. GABA-A receptor impairment in cerebellar ataxia with anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. J. Neurol. 2013;260:3086–3092. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7092-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori Y., Wakamori M., Oda S., Fletcher C.F., Sekiguchi N., Mori E., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Matsushita K., Matsuyama Z., Imoto K. Reduced voltage sensitivity of activation of P/Q-type Ca2 + channels is associated with the ataxic mouse mutation rolling Nagoya (tg(rol)) J. Neurosci. 2000;20:5654–5662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05654.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher C.F., Lutz C.M., O'Sullivan T.N., Shaughnessy J.D., Jr., Hawkes R., Frankel W.N., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A. Absence epilepsy in tottering mutant mice is associated with calcium channel defects. Cell. 1996;87:607–617. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayata C., Shimizu-Sasamata M., Lo E.H., Noebels J.L., Moskowitz M.A. Impaired neurotransmitter release and elevated threshold for cortical spreading depression in mice with mutations in the alpha1A subunit of P/Q type calcium channels. Neuroscience. 2000;95:639–645. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell D.B., Hess E.J. L-type calcium channels contribute to the tottering mouse dystonic episodes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:23–31. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gault L.M., Siegel R.E. Expression of the GABAA receptor delta subunit is selectively modulated by depolarization in cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2391–2399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02391.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saliba R.S., Kretschmannova K., Moss S.J. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of GABAA receptors regulates receptor insertion and tonic current. EMBO J. 2012;31:2937–2951. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wullner U., Reimold M., Abele M., Burk K., Minnerop M., Dohmen B.M., Machulla H.J., Bares R., Klockgether T. Dopamine transporter positron emission tomography in spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, and 6. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:1280–1285. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.8.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P.S., Liu R.S., Yang B.H., Soong B.W. Regional patterns of cerebral glucose metabolism in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2, 3 and 6: a voxel-based FDG-positron emission tomography analysis. J. Neurol. 2007;254:838–845. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Topakian R., Pischinger B., Stieglbauer K., Pichler R. Rare clinical findings in a patient with sporadic hemiplegic migraine: FDG-PET provides diminished brain metabolism at 10-year follow-up. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:392–396. doi: 10.1177/0333102413513182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuyama Z., Wakamori M., Mori Y., Kawakami H., Nakamura S., Imoto K. Direct alteration of the P/Q-type Ca2 + channel property by polyglutamine expansion in spinocerebellar ataxia 6. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:RC14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-j0004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toru S., Murakoshi T., Ishikawa K., Saegusa H., Fujigasaki H., Uchihara T., Nagayama S., Osanai M., Mizusawa H., Tanabe T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 mutation alters P-type calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10893–10898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tottene A., Fellin T., Pagnutti S., Luvisetto S., Striessnig J., Fletcher C., Pietrobon D. Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations increase Ca(2 +) influx through single human CaV2.1 channels and decrease maximal CaV2.1 current density in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:13284–13289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192242399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]