Two ATP binding cassette G transporters play a collaborative role in transferring lipidic molecules from tapetal cells for the development of anther cuticle and pollen exine.

Abstract

Male reproduction in higher plants requires the support of various metabolites, including lipid molecules produced in the innermost anther wall layer (the tapetum), but how the molecules are allocated among different anther tissues remains largely unknown. Previously, rice (Oryza sativa) ATP binding cassette G15 (ABCG15) and its Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ortholog were shown to be required for pollen exine formation. Here, we report the significant role of OsABCG26 in regulating the development of anther cuticle and pollen exine together with OsABCG15 in rice. Cytological and chemical analyses indicate that osabcg26 shows reduced transport of lipidic molecules from tapetal cells for anther cuticle development. Supportively, the localization of OsABCG26 is on the plasma membrane of the anther wall layers. By contrast, OsABCG15 is polarly localized in tapetal plasma membrane facing anther locules. osabcg26 osabcg15 double mutant displays an almost complete absence of anther cuticle and pollen exine, similar to that of osabcg15 single mutant. Taken together, we propose that OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 collaboratively regulate rice male reproduction: OsABCG26 is mainly responsible for the transport of lipidic molecules from tapetal cells to anther wall layers, whereas OsABCG15 mainly is responsible for the export of lipidic molecules from the tapetal cells to anther locules for pollen exine development.

Anther cuticle and pollen exine, two lipidic barriers, covering the outer surface of anther and pollen grain, respectively, play important protective roles in male reproductive development in flowering plants. Similar to the epidermal cuticle of most plant vegetative organs, the anther cuticle consists of the lipidic polyester cutin laying on the anther surface and cuticular wax that is deposited on or embedded within the cutin matrix (Jung et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010). Cutin is a polyester insoluble in organic solvents consisting mainly of fatty acid oxygenated derivatives with a chain length of 16 and 18 carbons, whereas cuticular wax is a complex mixture of very long-chain fatty acid derivatives, terpenoids, and phenolic components (Nawrath, 2002, 2006). In plant vegetative organs, such as stem and leaf, it is believed that cuticular lipid biosynthesis occurs exclusively within epidermal cells from which lipidic molecules are transported to the organ surface by ATP binding cassette G (ABCG) transporters and lipid transport proteins (LTPs; Sieber et al., 2000; Nawrath, 2002; Pighin et al., 2004; Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007; Debono et al., 2009). However, biosynthesis and transport of cuticular lipids in reproductive organs remain largely unknown.

Sporopollenin is one of the main component of pollen exine, which is thought to be made up of aliphatic and aromatic constituents. Sporopollenin is extremely resistant to physical, biological, and chemical degradation, therefore, it plays a critical role in providing protection for pollen grains from abiotic and biotic stresses (Dobritsa et al., 2010; Ariizumi and Toriyama, 2011). The chemical nature and assembly mechanism of sporopollenin still remain largely unclear.

The tapetum, the innermost layer of the four anther cell wall layers, is considered the site of pollen sporopollenin and anther cuticle precursor synthesis, at least in the monocot model plant rice (Oryza sativa; Yang et al., 2014). Up to date, some tapetum-expressed proteins, such as cytochrome P450s (CYP450s; Li et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014), fatty acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase (Shi et al., 2011), ABCG transporters (Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014), LTPs (Zhang et al., 2010), and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors (Li et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008; Niu et al., 2013b), have been identified to be involved in anther cuticle and pollen exine development in rice. CYP704B2 functions as a ω-hydroxylase in producing ω-hydroxylated fatty acids with 16 and 18 carbon chains as the common precursors of two biopolymers: sporopollenin and cutin (Li et al., 2010). CYP703A3 catalyzes the in-chain hydroxylation of lauric acid (Yang et al., 2014). The fatty ACP reductase, Defective Pollen Wall (DPW), is localized in tapetal plastids and produces 1-hexadecanol from palmiltoyl-ACP substrate for anther cuticle and pollen exine development (Shi et al., 2011). The tapetum-expressed ABCG protein, OsABCG15, is considered to be required for the transport of lipidic precursors from tapetal cells to anther cuticle and pollen wall (Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014). OsC6 (for locus [LOC]_Os11g37280) belongs to the small LTP protein family, and it is expressed in tapetal cells and involved in the mediation of lipidic distribution from the tapetal cytoplasm to the extracellular space among different anther cell wall layers and to the anther locules and anther cuticle (Zhang et al., 2010). The bHLH transcription factor Tapetum Degeneration Retardation (TDR) and its ortholog in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS) both play a critical role in directly promoting the expression of genes associated with sporopollenin biosynthesis and the secretion of materials for pollen wall patterning (Zhang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2010, 2014; Yang et al., 2014; Zhang and Li, 2014). Mutation or knockdown of all of these genes caused male sterility and defective anther cuticle and pollen exine (Li et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2011; Niu et al., 2013a, 2013b; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014). Up to now, the mechanism underlying the lipid metabolism, particularly lipid transport from tapetum, remains obscure.

ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters are a large family of proteins in all kingdoms, and the ABCG subfamily is the largest of the ABC family in both rice and Arabidopsis (Verrier et al., 2008). ABCG transporters are known to be actively involved in the translocation of a broad range of substances across membranes, including hormones, mineral ions, peptides, secondary metabolites, xenobiotics, and lipids (Pighin et al., 2004; Rea, 2007; Verrier et al., 2008; Kuromori et al., 2010; Le Hir et al., 2013; Zhang and Li, 2014). Some plant ABCG proteins have been reported to contribute to the synthesis of extracellular barriers. In Arabidopsis, ABCG11 (Cuticular Defect and Organ Fusion1/DESPERADO/White-Brown Complex11; Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010), ABCG12 (Eceriferum5/WBC12; Pighin et al., 2004), ABCG13 (Panikashvili et al., 2010), ABCG29 (Alejandro et al., 2012), ABCG32 (Bessire et al., 2011), and ABCG26 (WBC27; Xu et al., 2010; Quilichini et al., 2010, 2014; Choi et al., 2011; Dou et al., 2011) have been shown to be involved in transport of lipidic compounds. Notably, it has been reported that these ABCG proteins have a broad substrates spectrum (for example, ABCG11 transports both cutin and wax monomers, and ABCG13 and ABCG32 mainly transport cutin monomers, whereas ABCG12 mainly transports wax precursors, and ABCG29 mainly transports monolignol). As transporters, ABCG transporters encoded as half-transporter form homodimers or heterodimers with other ABCG transporters. For example, ABCG11 forms homodimers and heterodimers with ABCG12, whereas ABCG12 forms only heterodimers with ABCG11 (McFarlane et al., 2010). Recently, four additional Arabidopsis ABCG proteins were reported to be related to pollen formation, including ABCG9 (Choi et al., 2014), ABCG31 (Choi et al., 2014), ABCG1 (Yadav et al., 2014), and ABCG16 (Yadav et al., 2014). Furthermore, three Arabidopsis ABCG proteins, ABCG2, ABCG6, and ABCG20, are required for the translocation of suberin in roots and polyesters in seed coats (Yadav et al., 2014). In Physcomitrella patens, PpABCG7 was found to be involved in cuticular wax monomer trafficking (Buda et al., 2013). In potato (Solanum tuberosum), ABCG1 is required for suberin formation in potato tuber periderm (Landgraf et al., 2014). In barley (Hordeum vulgare), HvABCG31, a full ABCG transporter, is involved in leaf cutin formation, and its rice ortholog OsABCG31 shows the similar function (Chen et al., 2011a). In rice, OsABCG5 is required for suberin formation (Shiono et al., 2014), and OsABCG15 is essential for the development of both anther cuticle and pollen exine (Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014). However, how these ABCG proteins cooperate and how they contribute to male reproductive development are not clear.

In this study, we report the isolation and characterization of a base substitution mutation of OsABCG26, a WBC/ABCG gene. Our chemical and cytological data support that OsABCG26 is vital for the export of cuticle precursors from the tapetum to the anther surface, and the previously identified OsABCG15 (Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014) contributes to the development of both anther cuticle and pollen exine. Furthermore, OsABCG15 is epistatic to OsABCG26 in regulating the development of these anther lipidic structures. This work provides insights into how two ABCG transporters, OsABCG26 and OsABCG15, function cooperatively on the formation of anther cuticle and pollen exine in rice.

RESULTS

Isolation and Genetic Analysis of osabcg26

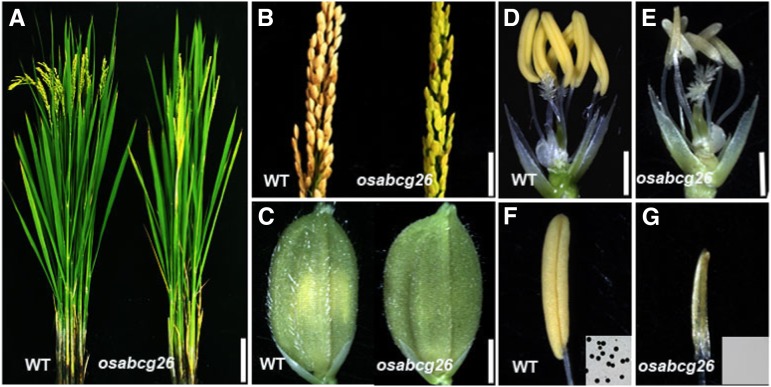

To identify further unique genes required for rice male reproductive development, we isolated the male sterile mutant osabcg26 from our rice mutant library made from the rice ssp. japonica ‘9522’ (Chen et al., 2006). We named this mutant osabcg26 because of a base substitution in the OsABCG26 gene detected by map-based cloning (see below). osabcg26 exhibited normal development of vegetative organs and nonreproductive floral organs but formed small and pale anthers that failed to generate viable pollen grains (Fig. 1). osabcg26 was backcrossed with cv 9522 three times and used for genetic and phenotypic analyses. All of the F1 progeny displayed a normal phenotype, and F2 progeny segregated for 76 normal and 17 mutant plants (x2 = 1.028 for 3:1; P > 0.05), indicating that this male sterility mutant of osabcg26 is caused by a single recessive mutation. Moreover, pollination of the mutant pistil with wild-type pollen yielded viable seeds, indicating that function of female flower organs in osabcg26 is normal.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic analysis of osabcg26. A, Wild-type (WT) and osabcg26 plants after heading. B, Wild-type and osabcg26 seed setting. C, Wild-type and osabcg26 flowers before anthesis. D and E, Wild-type and osabcg26 flower organs after removal of the palea and lemma. F and G, Wild-type yellow anther and osabcg26 pale yellow smaller anther. Insets show stained pollen grains. Bars = 10 cm (A), 2.5 cm (B), 2 mm (C), 1.5 mm (D and E), and 1 mm (F and G).

Characterization of osabcg26

To investigate the cytological defects of osabcg26, we examined the development of wild-type and osabcg26 anthers in detail using semithin section analysis. Based on the previous classification of rice anther development (Zhang and Wilson, 2009), we delineated rice anther development into 14 stages. At stage 8 during the formation of tetrads, no obvious morphological alteration was observed in osabcg26 anthers compared with the wild type (rice ssp. japonica ‘9522’; Fig. 2, A and E). At stage 9 of anther development, the wild-type anther exhibited condensed and deeply stained tapetal cells and a degenerated and invisible middle layer as well as free young microspores (Fig. 2B). By contrast, at this stage, osabcg26 showed irregular shape microspores and did not exhibit obvious degradation of tapetal and middle layers (Fig. 2F). At stage 10, the wild-type tapetal cells became degenerated, and microspores appeared to be round and vacuolated in shape (Fig. 2C); however, osabcg26 displayed dark-stained tapetal cells, persisted middle layers, collapsed microspores, and deep-stained debris in anther locules (Fig. 2G). At stage 11, the wild-type anther contained no middle layer and endothecium but the typical falcate pollen grains (Fig. 2D), whereas osabcg26 showed the persisted middle layer and endothecium and collapsed anther locules containing deep-stained remnants in the center (Fig. 2H).

Figure 2.

Defective cuticle and pollen development in osabcg26. A to H, Comparison of anther development in the wild type (WT) and osabcg26. The images are cross sections of a single locule. Wild-type anthers are shown in A to D, and osabcg26 anthers are shown in E to H. I to P, SEM analysis of anther outer surface of the wild type (I) and osabcg26 (M), anther inner surface of the wild type (J) and osabcg26 (N), pollen grains of the wild type (K) and osabcg26 (O), and pollen grains surface of the wild type (L) and osabcg26 (P) at stage 13 (St13). DMsp, Degenerated microspore; E, epidermis; En, endothecium; GP, germination pore; ML, middle layer; Msp, microspore; T, tapetum; Tds, tetrads; Ub, Ubisch body. Bars = 15 µm (A–H), 10 µm (I and M), 2 µm (J and N), 6 µm (K and O), and 1 µm (L and P).

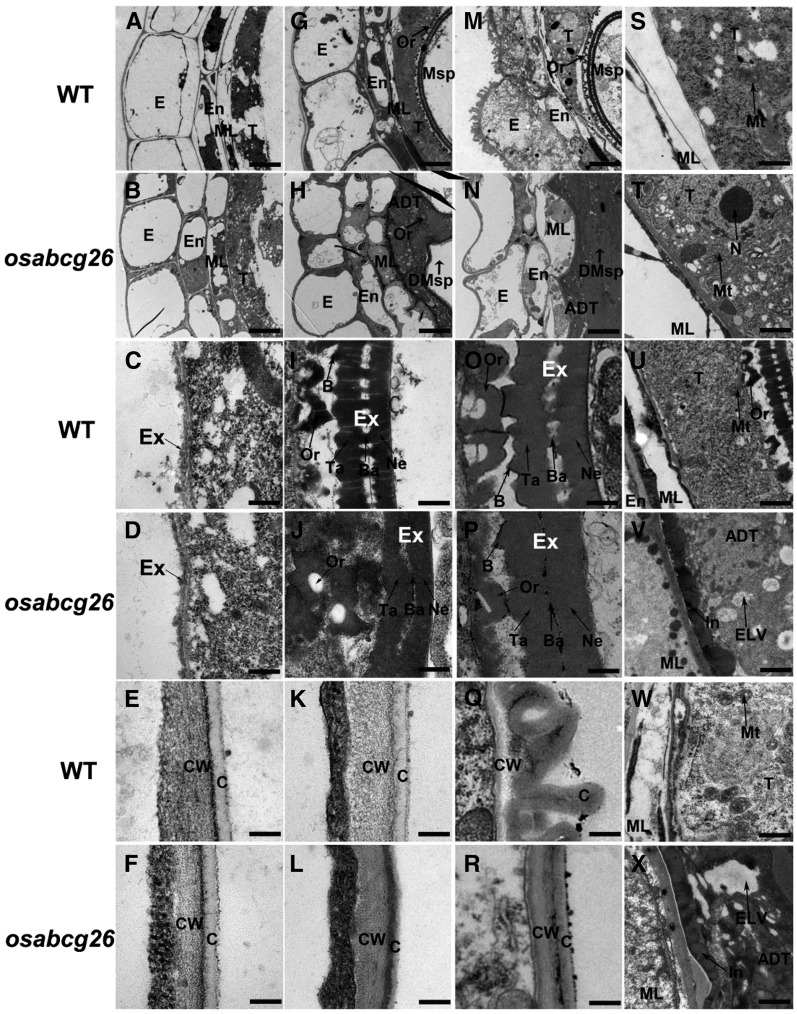

To observe more detailed defects of the osabcg26 mutant, we examined the anthers using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Consistent with the observations of semithin sections, at stage 9, the wild-type middle layer and tapetum appeared to be condensed cytoplasm-containing vacuoles (Fig. 3A), an indicator of cell death (Li et al., 2006; Niu et al., 2013a, 2013b); however, the osabcg26 displayed a less condensed middle layer and tapetal cells with less vacuolation (Fig. 3B). At this stage, the osabcg26 microspores released from the tetrads began to form an exine, which is similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 3, C and D). At stage 10, the three inner anther wall layers of the wild type showed degeneration; particularly, the middle layer was nearly invisible, and many electron-dense orbicules/Ubisch bodies extruded onto the locular side of the tapetum (Figs. 2J and 3G). However, the middle layer and endothecium of osabcg26 anthers appeared to be less degenerated, whereas its tapetal layer was abnormally degenerated, and dark-stained materials accumulated in tapetal cells close to the middle layer and anther locules surrounding the microspores (Fig. 3, H and V; Supplemental Fig. S1E). The lipidic components are frequently dark stained during TEM analysis; thus, our observation suggested the block of the export of lipidic materials from tapetal cells. Supportively, numerous electron-lucent vacuoles accumulated in tapetal cytosol of osabcg26 (Fig. 3V), which was not observed in the wild-type tapetum at the same stage (Fig. 3U). Consistently, at this stage, the wild-type microspores exhibited nearly a completed pollen exine structure with distinctive sexine, nexine sublayers, and baculum, and the sexine showed the typical bulged structure (Fig. 3I), whereas osabcg26 microspores showed a disordered pollen exine with narrow space between the sexine and nexine and without the typical bulged structure (Fig. 3J). Until stage 11, wild-type anther epidermis displayed protrudent hair-like structures (Fig. 3, M and Q), and sporopollenin precursors were secreted onto the microspore surface to thicken the exine (Fig. 3O). However, osabcg26 anthers showed no obvious protrudent hair-like anther cuticle, less degenerated endothecium, middle layer (Fig. 3, N and R; Supplemental Fig. S1F), and dark-stained tapetal cells as well as obvious bright vacuoles (Fig. 3, N and X). Moreover, unlike the well-developed pollen exine patterning in the wild type, osabcg26 showed abnormal thickened pollen exine, in which there was no space between sexine and nexine and no obvious bulged structure on the exine surface (Fig. 3, O and P). The TEM result was corroborated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) examination (Fig. 2P), in which the bulged structure in osabcg26 exine surface was obscure at stage 13, indicating possible overdeposition of lipidic precursors onto the pollen exine surface. Consistent with the role of characteristic orbicules/Ubisch bodies in exporting tapetum-synthesized sporopollenin precursors across the hydrophilic cell wall to the anther locule (Huysmans et al.,1998; Li et al., 2010, 2011), we observed the regular shape of orbicules containing electron-dense lipidic precursors along the tangential inner surface of wild-type tapetal cells (Fig. 3, I and O); in contrast, the morphological structure of osabcg26 orbicules/Ubisch bodies was abnormal, which contained more electron-dense lipidic substances (Fig. 3, J and P). Consistently, SEM examination revealed that, at stage 13, wild-type anther formed a well-organized clathrate texture cuticle on the outer surface (Fig. 2I) but that osabcg26 anther exhibited undeveloped outer surface with a smooth appearance of anther cuticle surface (Fig. 2M). Moreover, at stage 13, wild-type mature pollen grains showed full round shape surface with germinal aperture (Fig. 2K), whereas osabcg26 pollen grains appeared to be severely shrunken (Fig. 2O). The defective formation of anther cuticle, overaccumulation of lipidic materials surrounding microspores, and defective pollen exine structure in osabcg26 (Figs. 2, M, O, and P and 3, H, J, N, P, R, V, and X) suggested abnormal synthesis/supply of lipophilic molecules for the formation of anther cuticle and pollen exine in osabcg26.

Figure 3.

TEM analysis of osabcg26 anthers. A, G, and M, Cross sections of wild-type (WT) anther wall layers at stages 9 to 11. B, H, and N, Cross sections of osabcg26 anther wall layers at stages 9 to 11. C, I, and O, The pollen exine development of the wild type at stages 9 to 11. D, J, and P, The defective pollen exine development of osabcg26 at stages 9 to 11. E, K, and Q, The outer region of anther epidermis in the wild type at stages 9 to 11. F, L, and R, The outer region of anther epidermis in osabcg26 at stages 9 to 11. S and T, The structure of the tapetum in the wild type (S) and osabcg26 (T) at stage 9. U and V, The structure of the tapetum in the wild type (U) and osabcg26 (V) at stage 10. W and X, The structure of the tapetum in the wild type (W) and osabcg26 (X) at stage 11. ADT, Abnormal degenerated tapetum; B, bulged; Ba, bacula; C, cuticle; CW, cell wall; DMsp, degenerated microspore; E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ELV, electron-lucent vacuoles; Ex, exine; In, inclusion; ML, middle layer; Msp, microspore; Mt, mitochondrion; N, nucleus; Ne, nexine; Or, orbicule; T, tapetum; Ta, tectum. Bars = 10 µm (A, B, G, H, M, and N), 500 nm (C–F, I–L, and O–R), and 1 µm (S–X).

Reduced Wax Components and Cutin Monomers in osabcg26 Anthers

The phenotypic defect of osabcg26 anther cuticle indicated that osabcg26 may have altered biosynthesis or transport of precursors for the development of anther cuticle. To test this hypothesis, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and gas chromatography-flame ionization detection (GC-FID) were used to compare wax and cutin contents between the wild type and osabcg26 anthers of stage 12 (Franke et al., 2005). Surface areas of randomly selected anther samples were calculated and plotted against the dry weight of each corresponding sample as described previously (Supplemental Fig. S2; Li et al., 2010) to relate wax and cutin amounts to surface areas of anthers.

Results of the chemical analysis showed a dramatic reduction for most of the cutin monomers in osabcg26 anthers (Fig. 4, C and D; Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4; Supplemental Table S1). We detected 0.727 µg mm−2 cutin monomers in wild-type anther epidermis, whereas only 0.19 µg mm−2 cutin monomers were detected in the osabcg26 anther epidermis, which corresponds to approximately 74% reduction of the total cutin monomer amount compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Table S1). Similarly, the total wax of osabcg26 anthers was reduced compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 4A). Therefore, chemical analysis data suggested that the OsABCG26 affects anther cuticle development, which in turn, affects the male reproductive development in rice.

Figure 4.

Analysis of anther wax and cutin in the wild type (WT), osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15. A, Total wax amounts per unit surface area (micrograms per millimeter−2) in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers. Error bars indicate sd (n = 5). B, Wax constituents per unit surface area (micrograms per millimeter−2) in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers. Error bars indicate sd (n = 5). C, Total cutin amounts per unit surface area (micrograms per millimeter−2) in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers. Error bars indicate sd (n = 5). D, Cutin constituents per unit surface area (micrograms per millimeter−2) in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers. Error bars indicate sd (n = 5). URWC1, Unknown rice wax constituent1; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Map-Based Cloning of OsABCG26

A map-based cloning approach was used to identify OsABCG26 based on 700 individuals of an F2 mapping population. The mutated gene was finally mapped on chromosome 10 between two markers, DW16 and DW11, defining a 148-kb region. These two markers were located in the bacterial artificial chromosome clones OSJNBa0051D19 and OSJNBa0066I08, respectively (Fig. 5). Sequence analysis revealed a base substitution from an A to a G at the 655th nucleotide in the coding region of an annotated gene (LOC_Os10g35180; http://www.gramene.org/), which caused an amino acid substitution in a conserved domain of ABCG transporters. To confirm that LOC_Os10g35180 is the mutated gene causing phenotypic defects, a binary plasmid pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:OsABCG26 was introduced into the osabcg26 homozygous plants. The male sterile phenotype of osabcg26 was fully complemented in transgenic plants (Supplemental Fig. S5). Furthermore, to better understand the role of OsABCG26, we generated transgenic plants that express OsABCG26 under control of the 35S Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) promoter. Surprisingly, a significant reduction in transcript levels of OsABCG26 was observed in the transgenic plants (Supplemental Fig. S6A). The results indicated that, instead of an overexpression, we obtained cosuppression in the transgenic plants. This has been reported previously for AtABCG11, where overexpression of this gene resulted in a cosuppression (Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010). Overall, plants cosuppressing OsABCG26 phenocopied osabcg26 lines (Supplemental Fig. S6). These results showed that the mutation in LOC_Os10g35180 is responsible for the male sterile phenotype of osabcg26 (Figs. 1, 2, 5, and 6; Supplemental Fig. S5).

Figure 5.

Cloning and analysis of OsABCG26. A, Fine mapping of OsABCG26 on chromosome 10 (Chr. 10). Names and positions of the markers are noted. B, A schematic representation of the exon and intron organization of OsABCG26 (Loc_Os10g35180); +1 indicates the putative starting nucleotide of translation, and the stop codon (TGA) is +5,293. Black boxes indicate exons, and intervening lines indicate introns. Numbers indicate the exon length (base). BAC, Bacterial artificial chromosome; UTR, untranslated regions.

Figure 6.

Phenotypic analysis of osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers. A to D, Semithin section analysis of anther in the wild type (WT; A), osabcg26 (B), osabcg15 (C), and osabcg26 osabcg15 (D). E to H, The structure of the tapetum and pollen exine in the wild type (E), osabcg26 (F), osabcg15 (G), and osabcg26 osabcg15 (H) by TEM. I to L, The outer region of anther epidermis in the wild type (I), osabcg26 (J), osabcg15 (K), and osabcg26 osabcg15 (L) by TEM. M to P, SEM analysis of the anther surface of the wild type (M), osabcg26 (N), osabcg15 (O), and osabcg26 osabcg15 (P). C, Cuticle; E, exine; In, inclusion; ML, middle layer; St, stage; T, tapetum. Bars = 20 µm (A–D), 1 µm (E–L), and 10 µm (M–P).

OsABCG26 belongs to the ABCG subfamily, with more than 40 members in both dicot Arabidopsis and monocot rice. Phylogenetic analysis (Verrier et al., 2008) showed that its closest protein is AtABCG11, which was shown to be involved in transport of cuticular lipids in both vegetative and reproductive organs (Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010). Unlike its ortholog in Arabidopsis that shows a broad expression pattern in many vegetative and reproductive organs (Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010), the expression of OsABCG26 seems to be nearly strictly in reproductive organs, including anther and the pistil (Fig. 7). In addition, atabcg11 shows defective cuticular lipid metabolism in not only vegetative tissues, such as leaf and stem (Panikashvili et al., 2007), but also, reproductive organs, such as flowers and seeds (Panikashvili et al., 2010); osabcg26 only shows defective anther cuticle and pollen exine (Figs. 2M, 3, P and R, and 4; Supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting the conserved and divergent functions of ABCG proteins during evolution.

Figure 7.

The expression analysis of OsABCG26. A, qRT-PCR analysis of OsABCG26. RNA was extracted from anthers, Error bars indicate sd, and each reaction had three biological repeats. B, GUS expression was visible in anthers of the OsABCG26pro:GUS transgenic line at various stages. C, GUS expression (arrows) in the epidermis, endothecium, and tapetum at stage 9 (St9). E, Epidermis; En, endothecium; Le/pa, lemma and palea; T, tapetum; WT, wild type.

osabcg26 osabcg15 Displays Phenotypes Similar to osabcg15

Previously, we reported that the knockout mutant of OsABCG15 exhibits defective postmeiotic development, including abnormal degeneration of tapetal cells and no obvious formation of pollen exine and anther cuticle (Hu et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2013). To understand the relationship between OsABCG15 and OsABCG26 in regulating the development of anther cuticle and pollen exine, we made the osabcg26 osabcg15 double mutant by crossing and genotyping. At stage 10, osabcg26 osabcg15 microspores became degraded, and the anther locule filled with degenerated debris (Fig. 6D). At stages 11 and 13, osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers showed defective anther cuticle and aborted microspores (Fig. 6, H, L, and P), which are similar to those of osabcg15. Chemical analysis revealed that the level of wax was lower in osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers compared with that of osabcg26 or osabcg15 single mutant and that total cutin level of osabcg26 osabcg15 did not show any significant difference compared with that of osabcg26 or osabcg15 (Fig. 4, A and C). Notably, the contents of some cutin monomers in osabcg26 osabcg15, such as ω-OH acid and midchain oxygenated acid, were significantly more reduced compared with those of osabcg26 or osabcg15 (Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. S4). Overall, the osabcg26 osabcg15 phenotype is similar to that of osabcg15.

OsABCG26 Is Highly Expressed in Reproductive Organs

The main defects of osabcg26 are observed in anther development, whereas there is no obvious phenotype for vegetative growth. To confirm that the role of OsABCG26 is dedicated to the anther development, we tested the expression pattern of OsABCG26 using quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR, and results indicated that OsABCG26 expression was mainly detectable in reproductive organs, such as anthers and pistils. In anthers, the expression of OsABCG26 was observed at stage 7, which increased along the developmental stages, peaked at stage 10, and then, declined. The signal of OsABCG26 transcripts was relatively low in other organs, including glumes, lemmas, paleas, stems, and leaves, and there was hardly detectable signal in roots (Fig. 7). This expression pattern of OsABCG26 is consistent with its function in rice reproductive development. In addition, compared with the wild type, the OsABCG26 expression level in osabcg26 was relatively lower (Fig. 7A), which is likely because of the fact that osabcg26 has a single-amino acid residue substitution. Furthermore, transgenic plants expressing the pOsABCG26:GUS showed that GUS activity was detectable mainly in the epidermis, the endothecium, and the tapetal cell layers of the anthers at stage 9 (Fig. 7, B and C).

OsABCG26 Protein Is Localized on the Plasma Membrane of Anther Wall Layers

To understand how OsABCG26 affects anther development, we tested the subcellular localization of OsABCG26 by generating an enhancer yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP)-OsABCG26 fused expression cassette under the control of the CaMV35S promoter. The fused expression vector was transiently transferred into onion (Allium cepa) epidermal cells by particle bombardment, and the eYFP fluorescent signal was detected on the cell periphery (Fig. 8E). In contrast, the free eYFP signal was detectable in both the cell periphery and nuclei (Fig. 8A). To distinguish whether eYFP-OsABCG26 is localized to the cell wall or plasma membrane, we treated the cells with 0.8 m mannitol to induce plasmolysis. Under plasmolysis, eYFP-OsABCG26 was found to be associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 8F), and free eYFP signal was found in the plasma membrane and nuclei (Fig. 8B). This result suggested that OsABCG26 is localized to the plasma membrane.

Figure 8.

Plasma membrane localization of OsABCG15 and OsABCG26 visualized by confocal microscopy. A to F, Localization of fusions proteins eYFP-OsABCG15 and eYFP-OsABCG26 in onion epidermal cells. In each image pair, the photo on the left was acquired through bright field, and the photo on the right shows the fluorescence image of the same cell. G, eYFP-OsABCG26 signal at the plasma membrane of epidermal cells of anther (arrow). H, Plasma membrane of epidermal cells of anther stained with FM4-64. I, eYFP-OsABCG26 colocalized with plasma membrane stained with FM4-64. Anther derived from plants harboring the pOsABCG26:eYFP-OsABCG26 vector (eYFP fused in the N termini) at stage 9. Bars = 50 µm (A–F) and 5 µm (G–I).

To further confirm the localization of OsABCG26 in rice anthers, we introduced the OsABCG26 full-length coding sequence (CDS) fused with eYFP into osabcg26 under the control of the promoter of OsABCG26 of 2.7 kb in length. Sixteen independent transgenic lines showed completely rescued male fertility of osabcg26 (Supplemental Fig. S8C), suggesting the functional fusion of eYFP-OsABCG26 in plants. In all tested transgenic lines, the eYFP signal was observed in the periphery within the cells and colocalized with the plasma membrane signal stained with FM4-64 (Fig. 8I). Intriguingly, the signal of eYFP-OsABCG26 was observed specifically in the anther wall layers: the epidermis, the endothecium, and the tapetal layer at stage 9, during which the middle layer becomes almost degenerated (Fig. 9, A–J). Given the phenotype of osabcg26 in accumulating lipidic molecules in tapetal cells and the protein localization on the plasma membrane in anther wall layers, we proposed that OsABCG26 is responsible for the transport of lipidic molecules from tapetum to anther wall layers.

Figure 9.

Tissue-specific localization of OsABCG26 and OsABCG15. Images were acquired through YFP filter (A, C, E, G, I, K, M, and O) and merge (B, D, F, H, J, L, N, and P) from YFP filter, bright field, and chlorophyll filter. A to J, eYFP-OsABCG26 signal localized at the epidermis, endothecium, and tapetum of anther in pOsABCG26:eYFP-OsABCG26-expressing plants at stage 9. A and B show images taken from a focal plane at a distal region of the epidermis. C and D show images taken from a focal plane at a distal region of the endothecium of the same anther shown in A. E and F show images taken from a focal plane at a distal region of the tapetum of the same anther shown in A. G and H show images taken from a focal plane at a unilateral region of the same anther shown in A. I and J show images taken from anther cross sections. K to P, eYFP-OsABCG15 signal localized at the tapetum of anther in pOsABCG15:eYFP-OsABCG15-expressing plants at stage 9. K and L show images taken from a focal plane at a distal region of tapetum. M and N show images taken from a focal plane at a unilateral region of the same anther shown in K. O and P show images taken from anther cross sections. Chlorophyll autofluorescence is shown for visualization of anther tissue. E, Epidermis; En, endothecium; Msp, microspore; T, tapetum. Bars = 10 µm (A–F, K, and L) and 30 µm (G–J and M–P).

OsABCG15 Is Mainly Localized on the Plasma Membrane of Tapetal Cells

Previously, we showed that mRNA signals of OsABCG15 are strongly detectable in tapetal cells during anther development (Zhu et al., 2013). To examine the localization of OsABCG15, in this study, we made the expression fusion of eYFP-OsABCG15, and transient expression assay in onion epidermal cells also suggested the localization of OsABCG15 to the plasma membrane (Fig. 8, C and D), similar to other ABC transporters. Furthermore, we generated transgenic plants using a construct in which eYFP was fused in frame to the N terminus of the OsABCG15 opening reading frame driven by the OsABCG15 promoter. Forty resulting independent transgenic lines in osabcg15 background displayed rescued male fertility (Supplemental Fig. S8D), suggesting the functional equivalence between OsABCG15 and eYFP-OsABCG15. In these transgenic plants, eYFP signal was detected exclusively in the tapetal layer, showing a polar localization along the inner side of tapetal layer facing anther locules (Fig. 9, M–P). The polar localization has been also reported in other ABCG proteins, such as AtABCG11 (Panikashvili et al., 2007) and AtABCG32 (Bessire et al., 2011). The protein localization signal is also in agreement with previous reported expression patterns of OsABCG15 (Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013).

Transcriptional Analysis of Genes Related to Lipid Metabolism in osabcg26

To understand the role of OsABCG26 in affecting lipid metabolism and explain the phenotype in osabcg26, we conducted comparative expression analysis of known genes involved in lipid metabolism during male reproductive development between the wild type and osabcg26. We observed dramatic reduced expression levels of cytochrome P450 704B2 (CYP704B2), CYP703A3, DPW, and Wax-deficient anther1 (WDA1) in osabcg26 anthers from stage 9 to stage 11 (Fig. 10). These results indicate that the mutation of OsABCG26 affects the biosynthesis of lipidic compounds required for anther cuticle and pollen exine development.

Figure 10.

The expression analysis of the gene-related lipid metabolism in anthers at stages 9 to 11 (St9–St11). qRT-PCR analysis of genes related to lipid metabolism in the wild type (WT) and osabcg26. Error bars indicate sd, and each reaction had three biological repeats.

Among the 32 ABCG half-transporters in rice, OsABCG26 shares the highest amino acid sequence identity with OsABCG9 and OsABCG12 (Verrier et al., 2008). Our expression analysis showed that the expression of OsABCG9 is increased in osabcg26 anthers from stage 9 to stage 11, and the expression of OsABCG12 in osabcg26 anthers was also obviously increased at stage 10 (Supplemental Figs. S9 and S10). The expression of OsABCG15 was slightly increased in osabcg26 anthers at stage 9; however, there was no obvious difference between the wild type and osabcg26 afterward (Fig. 10). Notably, the expression of OsC6 was also dramatically reduced in osabcg26 anthers (Fig. 10), and the expression of an additional six of nine anther preferentially expressed ABCG transporter genes was obviously increased in osabcg26 anthers (Supplemental Figs. S9 and S10; Supplemental References S1). These results suggested that mutation of OsABCG26 may cause a negative feedback regulation of the expression of other ABCG transporter genes.

Moreover, we observed that the mutation of OsABCG26 also affected the expression of three previously reported program cell death regulators, such as TDR (Li et al., 2006), GAMYB (Aya et al., 2009), and PERSISTENT TAPETAL CELL1 (PTC1; Li et al., 2011). The expression levels of TDR and GAMYB were decreased in osabcg26, whereas those of PTC1 were fluctuating in osabcg26 (Fig. 10). These expression data confirmed again that blocked lipid transport could affect general lipid metabolism, which is in agreement with the previous finding of AtABCG11 (Panikashvili et al., 2010). These expression data may explain the delayed degeneration of endothecium and middle layer of the anthers in osabcg26.

In addition, by searching against the published microarray data of known transcription factors involved in cuticle development and pollen exine formation in rice, we found that the expression of OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 was significantly reduced in undeveloped tapetum1 (2.23- and 4.53-fold, respectively, in anthers of stages 8 and 9; Jung et al., 2005) and tdr (at least 2.68- and 100-fold, respectively, in anthers of stages 8 and 9; Zhang et al., 2008). Given that AMS, the Arabidopsis ortholog of TDR, directly regulates the expression of AtABCG26, the Arabidopsis ortholog of OsABCG15 (Xu et al., 2010), we propose that TDR may act as the direct regulator of OsABCG15, which remains to be elucidated.

DISCUSSION

Rice anther cuticle and pollen exine play an important protective role for male gametophytes from various environmental stresses. Although lipid metabolism is well known to be involved in the formation of these two barriers, the exact mechanism regarding lipid transport/export from tapetal cells to other tissues is still poorly understood. Here, we isolated and identified a gene, OsABCG26, that is highly expressed in rice reproductive organs and essential for normal anther cuticle and pollen development (Figs. 2M, 3, P and R, and 7). OsABCG26 protein is located to the plasma membrane of anther wall layers (Figs. 8, E and F and 9, A–J), and the osabcg26 null mutation causes defective anther development that fails to produce viable pollens (Fig. 1G). The morphological defect in the anther cuticle was accompanied by the significant reduction in wax and cutin loads in osabcg26. We reveal that another anther-expressed ABCG transporter, OsABCG15, is preferentially localized in the tapetal plasma membrane polarly toward anther locules (Figs. 8, C and D and 9, M–P). In addition, osabcg26 osabcg15 shows a similar phenotype to that of osabcg15. These findings suggest that OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 collaboratively regulate anther cuticle and pollen exine formation, playing important roles in rice male reproduction. Given the fact that the OsABCG26 protein was found to be localized on the plasma membrane of epidermis, endothecium, and tapetum layers of the anther, whereas that of OsABCG15 was polarly localized to only plasma membrane of tapetum facing the microspore (Fig. 9), we propose that OsABCG26 is mainly responsible for anther cuticle formation, whereas OsABCG15 is mainly responsible for the development of pollen exine. However, whether OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 function in the same pathway or complex in lipid export still remains to be investigated. We failed to identify an interactional of these two proteins with yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid assays, probably because of no interaction between them or the difficulties in heterologous expression of plant transporters in yeast (McFarlane et al., 2010). Other approaches need to be used in future to solve this specific issue.

OsABCG26 Is Important for the Transport of Wax and Cutin Precursors from the Tapetum to the Anther Surface

In this study, we show strong evidence that OsABCG26 plays an important role in the transport of wax molecules and cutin monomers from the tapetum to the anther surface across the plasma membranes of anther wall layers. This is supported by the protein localization in the plasma membrane of anther wall layers during the pollen development (Figs. 8, E and F and 9, A–J) and reduced amounts of wax and cutin loads (Figs. 2M, 3R, and 4; Supplemental Figs. S3 and S4; Supplemental Table S1). The spatial and temporal expression patterns of OsABCG26 are predominantly in reproductive organs (Fig. 7), suggesting the specialized role of OsABCG26 in reproduction development. Consistently, mutation of OsABCG26 did not affect leaf cuticle structure (Supplemental Fig. S7), which is different from its Arabidopsis ortholog AtABCG11 (WBC11; Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010). AtABCG11 mainly affects the formation of vegetative organ cuticles, such as stem and leaf cuticle as well as flower cuticle and root suberin (Bird et al., 2007; Panikashvili et al., 2007, 2010). Moreover, phenotypic analysis showed the defects of osabcg26 in anther cuticle are similar to those of other previously reported mutants, such as cyp704b2, dpw, and osabcg15 (Li et al., 2010; Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014).

Furthermore, TEM observations indicate that osabcg26 tapetal cells undergo abnormal degradation and have irregular accumulation of dark-stained lipidic components. It is noteworthy that numerous electron-dense lipidic granules inclusions are distributed along the tapetal cell locules wall adjacent to the middle layer in osabcg26 (Fig. 3, V and X). Although the exact components of the electron-dense granules inclusions observed in osabcg26 are unknown, similar inclusions have been previously described in tapetal locules of Arabidopsis anther lipid metabolism-defective mutants, including a lipid transport mutant atabcg26 (Choi et al., 2011) and three mutants with defective primexine: no exine formation1 (Ariizumi et al., 2004), transient defective exine1 (Ariizumi et al., 2008), and callose synthase5 (Dong et al., 2005). It is believed that primexine is the template for initial sporopollenin accumulation, and defective primexine results in failing sporopollenin deposition, in which feedback regulates the tapetal lipid metabolism (Ariizumi et al., 2004, 2008; Dong et al., 2005; Ariizumi and Toriyama, 2011). Overall, the phenotypic defects of osabcg26 can be explained by the reduced capability to transport lipidic molecules from the tapetum to the endothecium, the epidermis, and the anther surface, which is necessary for normal cuticle formation because of the mutation of OsABCG26. Moreover, the similarity of defective anther cuticle of osabcg26 with those of cyp704b2 and dpw (Li et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2011), corresponding to the genes for synthesizing fatty alcohols and hydroxylated fatty acids for anther cuticle formation, respectively, suggests that the anther cuticular precursors, at least the part of cuticular precursors, may be produced in the tapetum and transported by OsABCG26. The phenotype of persisted middle layer and endothecium in osabcg26 was also observed in mutants of sporopollenin and cutin biosynthetic genes, such as cyp704b2 and dpw (Li et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2011), indicating possible signaling roles of lipids from tapetum in the degradation of middle layer and endothecium. The expression levels of these two lipid metabolism-related genes are both reduced in osabcg26 (Fig. 10), suggesting a possible negative feedback regulation mechanism in rice anther that might maintain lipid metabolism homeostasis to avoid excess lipid accumulation in the tapetum, which prevents waste of energy sources. In summary, our data indicated that OsABCG26 functions in different anther wall layers to export tapetum-synthesized lipid molecules across plasma membranes to the anther surface for normal anther cuticle formation; therefore, mutation of OsABCG26 leads to defective anther cuticle, abnormal pollen exine, and male sterility. Nevertheless, further biochemical analysis is needed for the validation of the proposed roles of OsABCG26 in the export of tapetum-synthesized lipid molecules to the anther surface.

OsABCG15 Is Mainly Involved in the Transport of Sporopollenin Precursors

Previous studies show that osabcg15 is defective in pollen exine and anther cuticle formation (Niu et al., 2013a; Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014); however, the mechanism underlying the formation of pollen exine and anther cuticle is still not clear. Here, we observed that OsABCG15 is mainly localized in tapetal cells polarly facing the anther locules (Fig. 9, M–P), suggesting that OsABCG15 is likely involved mainly in the transport of lipid molecules synthesized in tapetum to microspores for the formation of pollen wall. This assumption can be supported indirectly by the finding that AtABCG26, the OsABCG15 ortholog in Arabidopsis, is involved in exine formation and pollen development (Quilichini et al., 2010, 2014). Furthermore, because of the defective anther cuticle phenotype of osabcg15, OsABCG15 may also function in transporting lipid precursors from the tapetum to anther surface. Previous studies suggested that the effect of mutation of OsABCG15/Postmeiotic deficient anther1 on anther cuticle formation is likely because of down-regulated expression of several cuticular lipid biosynthetic genes, such as CYP703A3, DPW, and CYP704B2 (Qin et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013). OsABCG15 protein localization data obtained in this study suggest the possible indirect effect of OsABCG15 on anther cuticle formation in rice.

Anther Cuticle and Pollen Exine Share One Common Aliphatic Synthetizing Pathway in Tapetum

It is generally accepted that sporopollenin, the pollen exine constituent, is produced exclusively in tapetum, and many genes involved in lipid synthesis and exine formation were identified in tapetum (Li et al., 2010; Quilichini et al., 2010, 2014; Ariizumi and Toriyama, 2011; Chen et al., 2011b; Shi et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013; Lou et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014). However, there is no common consensus about the anther cuticle synthesis. In plant vegetative organs, such as stems and leaves, it is believed that cuticular lipid biosynthesis occurs exclusively within epidermal cells (Sieber et al., 2000; Nawrath, 2002; Panikashvili et al., 2007). Previous reports showed that plastids could not been found in anther epidermal cells (Mamun et al., 2005a, 2005b), which implies that lipid de novo synthesis cannot occur within anther epidermal cells. Therefore, it is not surprising that several tapetum-expressed lipid metabolism genes are involved in anther cuticle formation (Li et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014). Here, we observed that OsABCG26 is localized to the plasma membrane of anther wall layers at stage 9 during anther development, and mutation of OsABCG26 leads to detective anther cuticle and pollen exine, suggesting that cuticular lipids are produced in the tapetum, from which they are exported or distributed by OsABCG26. Another known anther cuticle and pollen exine-related ABCG transporter, OsABCG15, is mainly localized in tapetal cells polarly facing the extracellular microspore at stage 9 during pollen development (Fig. 9, M–P), which implies that OsABCG15 likely secrets lipidic precursors to anther locules from the tapetum. Thus, these results suggest that anther cuticle and pollen exine may share one common aliphatic synthetizing pathway in tapetum as suggested in our model (Fig. 11). It is noteworthy that a previous study shows that WDA1, an epidermal specifically expressed gene, also profoundly affects anther cuticle formation (Jung et al., 2006). Perhaps, both epidermis and tapetum can produce lipid molecules for anther cuticle formation, but our data seem to be more supportive for tapetum-derived cuticular lipid production in anthers.

Figure 11.

The proposed model of the role of OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 during anther development. OsABCG26, a half-sized plasma membrane-localized transport protein possibly forming homodimers or heterodimers for export, may export lipidic precursors out of tapetal, endothecial, and epidermal cells to the surface for anther cuticle development at stages 9 and 10 when the middle layer degenerated. OsC6, an LTP protein, may transport lipidic precursors across cell spaces among different plasma membranes (Zhang et al., 2010). OsABCGX, a putative ABCG importer, may import lipidic precursors across the plasma membrane into different anther wall cells. In such a way, the lipidic precursors are eventually transported to the anther surfaces for cuticle formation. Meanwhile, sporopollenin precursors may be exported from tapetum to anther locule by OsABCG15 and then, to the surface of the microspore by OsC6 for exine formation (Zhang et al., 2010). ER, Endoplasmic reticulum.

CONCLUSION

This work highlights that wax and cutin precursors and sporopollenin precursors are synthesized in the tapetum (Fig. 11), and from the tapetum, they are transported to other cell layers for specific developmental purposes: to either anther surface for facilitating the cuticle formation or anther locules for facilitating exine formation. During this process, many ABCG proteins are involved, and the final destination of these transported lipids depended largely on the ABCG transporters. OsABCG26 transports lipids mainly to anther surface for anther cuticle formation, whereas OsABCG15 exports lipids mainly to anther locules for pollen exine formation (Fig. 11). Our work also highlights that anther cuticle and pollen exine share one common aliphatic synthetizing pathway in the tapetum (Fig. 11). Thus, our data provide unique insights into the mechanisms of ABCG transporters’ involvement in the anther cuticle and pollen exine formation and expand understanding of lipid metabolism-specific lipid transportation in the development of male reproductive organs in rice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

All of the rice (Oryza sativa) lines used in this study are in the background of rice ssp. japonica ‘9522’ and were grown in the paddy field of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The F2 mapping population was generated from a cross between the osabcg26 mutant (rice ssp. japonica) and cv 9311 (rice ssp. indica). In the F2 population, male-sterile plants were selected for gene mapping as previously described (Liu et al., 2005).

Characterization of the Mutant Phenotype

Morphology of whole plants and flowers at mature stage was photographed with a Nikon E995 Digital Camera. For pollen viability analysis, both wild-type and osabcg26 anthers were immersed into iodine-potassium iodide solution and then photographed with a Leica DM2500 Microscope. SEM and TEM were performed to observe anther and pollen development as described previously (Li et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008). For expression and chemical analyses, anthers from different developmental stages, as defined by Zhang and Wilson (2009), were collected based on spikelet length and lemma/palea morphology.

Molecular Cloning of OsABCG26

To fine map the OsABCG26 locus, bulked segregant analysis (Liu et al., 2005) was used, and insertion-deletion (InDel) molecular markers were designed based on the sequence difference between rice ssp. japonica and rice ssp. indica described in the National Center for Biotechnology Information. OsABCG26 locus was first mapped between two InDel molecular markers: Os1005 and Os1006. Then, 700 F2 segregants from the mapping cross were generated, and six InDel markers (DW8, DW16, DW5, DW11, DW12, and DW14) were used. OsABCG26 was eventually defined between DW16 and DW11 within a 148-kb region (Fig. 5). All primers used in the mapping are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

qRT-PCR Assay

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) from various rice tissues, including lemma, palea, glume, pistil, root, stem, leaf, and anther at different developmental stages as described by the supplier. qRT-PCR procedures and data analysis were performed as previous described (Li et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2013). All of the primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

Transgene Vector Construction and Plant Transformation

For generation of the osabcg26 functional complementation vector, 2,707 bp of the OsABCG26 upstream region (termed pOsABCG26), full-length OsABCG26 CDS, and the 78-bp downstream region were amplified using corresponding gene-specific primers and then, inserted into pCAMBIA1301 to construct the plasmid pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:OsABCG26. For examination of the tissue specificity of OsABCG26, the plasmid pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:GUS was constructed (the GUS marker protein was driven by the 2,707-bp OsABCG26 promoter region). For examination of the OsABCG26 protein localization, eYFP open reading frame was amplified without the stop codon using gene-specific primers and subcloned together with pOsABCG26 and full-length OsABCG26 CDS into pCAMBIA1301, and the plasmid pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:eYFP-OsABCG26 was constructed. The plasmids pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG15:eYFP-OsABCG15 and pCAMBIAPHB-35S:OsABCG26 were constructed in a similar way.

Calli induced from young panicles of the homozygous osabcg26 plants were used for transformation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens (EHA105) that carries either pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:OsABCG26 plasmid or pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:eYFP-OsABCG26 plasmid. Calli induced from young panicles of the homozygous osabcg15 plants were used for transformation with A. tumefaciens (EHA105) that carries pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG15:eYFP-OsABCG15 plasmid, and calli induced from young panicles of the cv 9522 plants were used for transformation with A. tumefaciens (EHA105) that carries pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:GUS plasmid or pCAMBIAPHB-OsABCG26 plasmid. At least 14 independent lines of each transgenic construct were obtained and verified with PCR using the gene-specific primers (Supplemental Fig. S11). Above primers used in vector construct and identification of transgenic plants are listed in Supplemental Tables S4 and S5, respectively.

GUS Staining Assay

GUS activity was visualized by staining the flowers from spikelets of transgenic lines overnight in 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (X-Gluc; Willemsen et al., 1998), and then, tissues were cleared in 70% (v/v) ethanol. The cleared anther was observed and photographed.

Subcellular Localization of OsABCG26

For examination of OsABCG26 protein localization, full-length OsABCG26 CDS sequences were cloned into the XhoI and BamHI sites of the PSAT6-p35S:eYFP-C1 plasmid; for examination of OsABCG15 protein localization, full-length OsABCG15 CDS sequences were cloned into the BglII and HindIII sites of the PSAT6-p35S:eYFP-C1 plasmid. Both OsABCG26 and OsABCG15 CDS were translationally fused to eYFP at the N terminus, and the resulting plasmids were coupled with gold particles, bombarded into onion (Allium cepa) epidermal cells, and observed as previously described (Liu and Mehdy, 2007). Anthers with pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG26:eYFP-OsABCG26 or pCAMBIA1301-pOsABCG15:eYFP-OsABCG15 at stage 9 were mounted in distilled water and observed under confocal microscopy. For plasma membrane staining, tissues were immersed in FM4-64 solution (10 µm) for 3 min. FM4-64 staining was detected using an excitation of 514 nm with a 600- to 650-nm band-pass filter. eYFP fluorescent signals were imaged at the excitation wavelength of 514 nm and the emission wavelength of 520 to 580 nm. The red autofluorescence of chlorophylls was imaged at emission wavelength longer than 640 to 700 nm. A laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS) was used for the analysis.

Analysis of Anther Wax and Cutin Constituents

Wax and cutin of anthers were analyzed as described previously (Jung et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010) with appropriate modifications. We generated a correlation of anther dried weight to surface area to express cuticular lipid amounts as unit weight per unit anther surface area (Supplemental Fig. S2). Anther surface area was determined from pixel numbers in microscopy images assuming a cylindrical body for rice anthers. To extract waxes, 5 to 10 mg of freeze-dried anther material corresponding to 125 to 402 mm2 of surface area was submersed in 1 mL of chloroform for 1 min two times. The resulting chloroform extracts were spiked with 10 µg of tetracosane (Fluka) as internal standard and transferred to new vials. The solvents were evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas until a final volume of 100 µL was reached. Compounds containing free hydroxyl and carboxyl groups were converted to their trimethylsilyl ethers and esters by adding 20 µL of N,N-bis-trimet hylsilyltrifluoroacit amide (Machery-Nagel) and 20 µL of pyridine to the extracts and incubating them for 40 min at 70°C. These derivatized samples were then analyzed by GC-FID (Agilent Technologies) and GC-MS (Agilent Gas Chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 5973N Quadrupole Mass Selective Detector). Anthers that had been used in the wax extraction were fully extracted with 1 mL of chloroform:methanol (1:1; v/v). They were first incubated at 50°C for 30 min and then, overnight with constant shaking at room temperature. This extraction was repeated three times to ensure that no soluble lipids were left in the anther samples. The remaining delipidated anthers were dried over silica gel and used to analyze the monomers composition of cutin polyester as described by Franke et al. (2005). All anther cutin samples were transesterified in 1 mL of 1 n methanolic HCl for 2 h at 80°C. After the addition of 2 mL of saturated NaCl-water and 20 µg of C32 alkane as internal standard, the hydrophobic monomers were subsequently extracted three times with 1 mL of hexane. The organic phases were combined, the solvent was evaporated, and the remaining sample was derived as described above. GC-MS and GC-FID analyses were performed as for the wax analysis.

Sequence data from this article for the complementary DNA and genomic DNA of OsABCG26 can be found in the GenBank/EMBL/Gramene data libraries under accession numbers LOC_Os10g0494300 and LOC_Os10g35180, respectively.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. TEM analysis of osabcg26.

Supplemental Figure S2. Weight/surface area ratio of wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers.

Supplemental Figure S3. Analysis of wax constituents in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers.

Supplemental Figure S4. Analysis of cutin monomers in wild-type, osabcg26, osabcg15, and osabcg26 osabcg15 anthers.

Supplemental Figure S5. Complementation of osabcg26 by OsABCG26.

Supplemental Figure S6. Expression and phenotypic analysis of OsABCG26 cosuppression line (co-osabcg26).

Supplemental Figure S7. SEM analysis of osabcg26 leaf surface structures.

Supplemental Figure S8. Complementation analysis of the osabcg26 and osabcg15 by eYFP-OsABCG26 and eYFP-OsABCG15 fusion protein, respectively.

Supplemental Figure S9. Rice ABCG genes expressed in the anther, root, shoot, and leaf.

Supplemental Figure S10. The expression analysis of eleven ABCG transporter genes in osabcg26 using qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Figure S11. Identification of transgenic plants.

Supplemental Table S1. Detailed cutin compositions of wild-type and osabcg26 anthers.

Supplemental Table S2. List of the primers used for mapping.

Supplemental Table S3. List of the primers used for qRT-PCR analysis.

Supplemental Table S4. List of the primers used for vector construction.

Supplemental Table S5. List of the primers for identification of transgenic plants.

Supplemental References S1. Reference cited in Supplemental Figure S9.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Changsong Yin for TEM assay and Zhijing Luo for mutants screening and generation of F2 population for mapping.

Glossary

- GC-FID

gas chromatography-flame ionization detection

- GC-MS

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Key Basic Research Developments Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology, China (grant no. 2013 CB126902); the 863 High Tech Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology, China (grant no. 2012AA10A302); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31322040 and 31271698); the Innovative Research Team, Ministry of Education, and 111 Project (grant no. B14016); the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant no. 13JC1408200); and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. SCHR 506/12–1 to L.S.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Alejandro S, Lee Y, Tohge T, Sudre D, Osorio S, Park J, Bovet L, Lee Y, Geldner N, Fernie AR, et al. (2012) AtABCG29 is a monolignol transporter involved in lignin biosynthesis. Curr Biol 22: 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T, Hatakeyama K, Hinata K, Inatsugi R, Nishida I, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Toriyama K (2004) Disruption of the novel plant protein NEF1 affects lipid accumulation in the plastids of the tapetum and exine formation of pollen, resulting in male sterility in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 39: 170–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T, Kawanabe T, Hatakeyama K, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Toriyama K (2008) Ultrastructural characterization of exine development of the transient defective exine 1 mutant suggests the existence of a factor involved in constructing reticulate exine architecture from sporopollenin aggregates. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T, Toriyama K (2011) Genetic regulation of sporopollenin synthesis and pollen exine development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62: 437–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aya K, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Kondo M, Hamada K, Yano K, Nishimura M, Matsuoka M (2009) Gibberellin modulates anther development in rice via the transcriptional regulation of GAMYB. Plant Cell 21: 1453–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessire M, Borel S, Fabre G, Carraça L, Efremova N, Yephremov A, Cao Y, Jetter R, Jacquat AC, Métraux JP, et al. (2011) A member of the PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE family of ATP binding cassette transporters is required for the formation of a functional cuticle in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1958–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird D, Beisson F, Brigham A, Shin J, Greer S, Jetter R, Kunst L, Wu X, Yephremov A, Samuels L (2007) Characterization of Arabidopsis ABCG11/WBC11, an ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter that is required for cuticular lipid secretion. Plant J 52: 485–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buda GJ, Barnes WJ, Fich EA, Park S, Yeats TH, Zhao L, Domozych DS, Rose JK (2013) An ATP binding cassette transporter is required for cuticular wax deposition and desiccation tolerance in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 25: 4000–4013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Komatsuda T, Ma JF, Nawrath C, Pourkheirandish M, Tagiri A, Hu YG, Sameri M, Li X, Zhao X, et al. (2011a) An ATP-binding cassette subfamily G full transporter is essential for the retention of leaf water in both wild barley and rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 12354–12359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chu H, Yuan Z, Pan A, Liang W, Huang H, Shen M, Zhang D, Chen L (2006) Isolation and genetic analysis for rice mutants treated with 60Co γ-ray. J Xiamen Univ 45: 82–85 [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Yu XH, Zhang K, Shi J, De Oliveira S, Schreiber L, Shanklin J, Zhang D (2011b) Male Sterile2 encodes a plastid-localized fatty acyl carrier protein reductase required for pollen exine development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 157: 842–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Jin JY, Choi S, Hwang JU, Kim YY, Suh MC, Lee Y (2011) An ABCG/WBC-type ABC transporter is essential for transport of sporopollenin precursors for exine formation in developing pollen. Plant J 65: 181–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Ohyama K, Kim YY, Jin JY, Lee SB, Yamaoka Y, Muranaka T, Suh MC, Fujioka S, Lee Y (2014) The role of Arabidopsis ABCG9 and ABCG31 ATP binding cassette transporters in pollen fitness and the deposition of steryl glycosides on the pollen coat. Plant Cell 26: 310–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono A, Yeats TH, Rose JK, Bird D, Jetter R, Kunst L, Samuels L (2009) Arabidopsis LTPG is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored lipid transfer protein required for export of lipids to the plant surface. Plant Cell 21: 1230–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa AA, Lei Z, Nishikawa S, Urbanczyk-Wochniak E, Huhman DV, Preuss D, Sumner LW (2010) LAP5 and LAP6 encode anther-specific proteins with similarity to chalcone synthase essential for pollen exine development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 153: 937–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Hong Z, Sivaramakrishnan M, Mahfouz M, Verma DPS (2005) Callose synthase (CalS5) is required for exine formation during microgametogenesis and for pollen viability in Arabidopsis. Plant J 42: 315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou XY, Yang KZ, Zhang Y, Wang W, Liu XL, Chen LQ, Zhang XQ, Ye D (2011) WBC27, an adenosine tri-phosphate-binding cassette protein, controls pollen wall formation and patterning in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol 53: 74–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke R, Briesen I, Wojciechowski T, Faust A, Yephremov A, Nawrath C, Schreiber L (2005) Apoplastic polyesters in Arabidopsis surface tissues: a typical suberin and a particular cutin. Phytochemistry 66: 2643–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Tan H, Liang W, Zhang D (2010) The Post-meiotic Deficicent Anther1 (PDA1) gene is required for post-meiotic anther development in rice. J Genet Genomics 37: 37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huysmans S, ElGhazaly G, Smets E (1998) Orbicules in angiosperms: morphology, function, distribution, and relation with tapetum types. Bot Rev 64: 240–272 [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Han MJ, Lee DY, Lee YS, Schreiber L, Franke R, Faust A, Yephremov A, Saedler H, Kim YW, et al. (2006) Wax-deficient anther1 is involved in cuticle and wax production in rice anther walls and is required for pollen development. Plant Cell 18: 3015–3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Han MJ, Lee YS, Kim YW, Hwang I, Kim MJ, Kim YK, Nahm BH, An G (2005) Rice Undeveloped Tapetum1 is a major regulator of early tapetum development. Plant Cell 17: 2705–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T, Miyaji T, Yabuuchi H, Shimizu H, Sugimoto E, Kamiya A, Moriyama Y, Shinozaki K (2010) ABC transporter AtABCG25 is involved in abscisic acid transport and responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 2361–2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf R, Smolka U, Altmann S, Eschen-Lippold L, Senning M, Sonnewald S, Weigel B, Frolova N, Strehmel N, Hause G, et al. (2014) The ABC transporter ABCG1 is required for suberin formation in potato tuber periderm. Plant Cell 26: 3403–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir R, Sorin C, Chakraborti D, Moritz T, Schaller H, Tellier F, Robert S, Morin H, Bako L, Bellini C (2013) ABCG9, ABCG11 and ABCG14 ABC transporters are required for vascular development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 76: 811–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Pinot F, Sauveplane V, Werck-Reichhart D, Diehl P, Schreiber L, Franke R, Zhang P, Chen L, Gao Y, et al. (2010) Cytochrome P450 family member CYP704B2 catalyzes the ω-hydroxylation of fatty acids and is required for anther cutin biosynthesis and pollen exine formation in rice. Plant Cell 22: 173–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Yuan Z, Vizcay-Barrena G, Yang C, Liang W, Zong J, Wilson ZA, Zhang D (2011) PERSISTENT TAPETAL CELL1 encodes a PHD-finger protein that is required for tapetal cell death and pollen development in rice. Plant Physiol 156: 615–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang DS, Liu HS, Yin CS, Li XX, Liang WQ, Yuan Z, Xu B, Chu HW, Wang J, et al. (2006) The rice Tapetum Degeneration Retardation gene is required for tapetum degradation and anther development. Plant Cell 18: 2999–3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Mehdy MC (2007) A nonclassical arabinogalactan protein gene highly expressed in vascular tissues, AGP31, is transcriptionally repressed by methyl jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 145: 863–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Chu H, Li H, Wang H, Wei J, Li N, Ding S, Huang H, Ma H, Huang C, et al. (2005) Genetic analysis and mapping of rice (Oryza sativa L.) male-sterile (OsMS-L) mutant. Chin Sci Bull 50: 122–125 [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Xu XF, Zhu J, Gu JN, Blackmore S, Yang ZN (2014) The tapetal AHL family protein TEK determines nexine formation in the pollen wall. Nat Commun 5: 3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun EA, Cantrill LC, Overall RL, Sutton BG (2005a) Cellular organisation and differentiation of organelles in pre-meiotic rice anthers. Cell Biol Int 29: 792–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamun EA, Cantrill LC, Overall RL, Sutton BG (2005b) Cellular organisation in meiotic and early post-meiotic rice anthers. Cell Biol Int 29: 903–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane HE, Shin JJH, Bird DA, Samuels AL (2010) Arabidopsis ABCG transporters, which are required for export of diverse cuticular lipids, dimerize in different combinations. Plant Cell 22: 3066–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C. (2002) The biopolymers cutin and suberin. The Arabidopsis Book 1: e0021, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C. (2006) Unraveling the complex network of cuticular structure and function. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9: 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu BX, He FR, He M, Ren D, Chen LT, Liu YG (2013a) The ATP-binding cassette transporter OsABCG15 is required for anther development and pollen fertility in rice. J Integr Plant Biol 55: 710–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu N, Liang W, Yang X, Jin W, Wilson ZA, Hu J, Zhang D (2013b) EAT1 promotes tapetal cell death by regulating aspartic proteases during male reproductive development in rice. Nat Commun 4: 1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panikashvili D, Savaldi-Goldstein S, Mandel T, Yifhar T, Franke RB, Höfer R, Schreiber L, Chory J, Aharoni A (2007) The Arabidopsis DESPERADO/AtWBC11 transporter is required for cutin and wax secretion. Plant Physiol 145: 1345–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panikashvili D, Shi JX, Bocobza S, Franke RB, Schreiber L, Aharoni A (2010) The Arabidopsis DSO/ABCG11 transporter affects cutin metabolism in reproductive organs and suberin in roots. Mol Plant 3: 563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pighin JA, Zheng H, Balakshin LJ, Goodman IP, Western TL, Jetter R, Kunst L, Samuels AL (2004) Plant cuticular lipid export requires an ABC transporter. Science 306: 702–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Tu B, Wang Y, Deng L, Quilichini TD, Li T, Wang H, Ma B, Li S (2013) ABCG15 encodes an ABC transporter protein, and is essential for post-meiotic anther and pollen exine development in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 54: 138–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilichini TD, Friedmann MC, Samuels AL, Douglas CJ (2010) ATP-binding cassette transporter G26 is required for male fertility and pollen exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 154: 678–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilichini TD, Samuels AL, Douglas CJ (2014) ABCG26-mediated polyketide trafficking and hydroxycinnamoyl spermidines contribute to pollen wall exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 4483–4498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea PA. (2007) Plant ATP-binding cassette transporters. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 347–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Tan H, Yu XH, Liu Y, Liang W, Ranathunge K, Franke RB, Schreiber L, Wang Y, Kai G, et al. (2011) Defective pollen wall is required for anther and microspore development in rice and encodes a fatty acyl carrier protein reductase. Plant Cell 23: 2225–2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiono K, Ando M, Nishiuchi S, Takahashi H, Watanabe K, Nakamura M, Matsuo Y, Yasuno N, Yamanouchi U, Fujimoto M, et al. (2014) RCN1/OsABCG5, an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, is required for hypodermal suberization of roots in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant J 80: 40–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber P, Schorderet M, Ryser U, Buchala A, Kolattukudy P, Métraux JP, Nawrath C (2000) Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing a fungal cutinase show alterations in the structure and properties of the cuticle and postgenital organ fusions. Plant Cell 12: 721–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrier PJ, Bird D, Burla B, Dassa E, Forestier C, Geisler M, Klein M, Kolukisaoglu U, Lee Y, Martinoia E, et al. (2008) Plant ABC proteins: a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci 13: 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen V, Wolkenfelt H, de Vrieze G, Weisbeek P, Scheres B (1998) The HOBBIT gene is required for formation of the root meristem in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development 125: 521–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Guan Y, Wu Z, Yang K, Lv J, Converse R, Huang Y, Mao J, Zhao Y, Wang Z, et al. (2014) OsABCG15 encodes a membrane protein that plays an important role in anther cuticle and pollen exine formation in rice. Plant Cell Rep 33: 1881–1899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Ding Z, Vizcay-Barrena G, Shi J, Liang W, Yuan Z, Werck-Reichhart D, Schreiber L, Wilson ZA, Zhang D (2014) ABORTED MICROSPORES acts as a master regulator of pollen wall formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 1544–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yang C, Yuan Z, Zhang D, Gondwe MY, Ding Z, Liang W, Zhang D, Wilson ZA (2010) The ABORTED MICROSPORES regulatory network is required for postmeiotic male reproductive development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22: 91–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Molina I, Ranathunge K, Castillo IQ, Rothstein SJ, Reed JW (2014) ABCG transporters are required for suberin and pollen wall extracellular barriers in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 3569–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wu D, Shi J, He Y, Pinot F, Grausem B, Yin C, Zhu L, Chen M, Luo Z, et al. (2014) Rice CYP703A3, a cytochrome P450 hydroxylase, is essential for development of anther cuticle and pollen exine. J Integr Plant Biol 56: 979–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Liang W, Yin C, Zong J, Gu F, Zhang D (2010) OsC6, encoding a lipid transfer protein, is required for postmeiotic anther development in rice. Plant Physiol 154: 149–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DB, Li H (2014). Exine Export in Pollen. Plant ABC Transporters. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DB, Wilson ZA (2009) Stamen specification and anther development in rice. Chin Sci Bull 54: 2342–2353 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DS, Liang WQ, Yuan Z, Li N, Shi J, Wang J, Liu Y, Yu W, Zhang DB (2008) Tapetum degeneration retardation is critical for aliphatic metabolism and gene regulation during rice pollen development. Mol Plant 1: 599–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liang W, Shi J, Xu J, Zhang D (2013) MYB56 encoding a R2R3 MYB transcription factor regulates seed size in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Integr Plant Biol 55: 1166–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Shi J, Zhao G, Zhang D, Liang W (2013) Post-meiotic deficient anther1 (PDA1) encodes an ABC transporter required for the development of anther cuticle and pollen exine in rice. J Plant Biol 56: 59–68 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.