The temperature responses of carbonic anhydrase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, and Rubisco have implications for model C4 photosynthesis.

Abstract

The photosynthetic assimilation of CO2 in C4 plants is potentially limited by the enzymatic rates of Rubisco, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc), and carbonic anhydrase (CA). Therefore, the activity and kinetic properties of these enzymes are needed to accurately parameterize C4 biochemical models of leaf CO2 exchange in response to changes in CO2 availability and temperature. There are currently no published temperature responses of both Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation kinetics from a C4 plant, nor are there known measurements of the temperature dependency of the PEPc Michaelis-Menten constant for its substrate HCO3−, and there is little information on the temperature response of plant CA activity. Here, we used membrane inlet mass spectrometry to measure the temperature responses of Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation kinetics, PEPc carboxylation kinetics, and the activity and first-order rate constant for the CA hydration reaction from 10°C to 40°C using crude leaf extracts from the C4 plant Setaria viridis. The temperature dependencies of Rubisco, PEPc, and CA kinetic parameters are provided. These findings describe a new method for the investigation of PEPc kinetics, suggest an HCO3− limitation imposed by CA, and show similarities between the Rubisco temperature responses of previously measured C3 species and the C4 plant S. viridis.

Biochemical models of photosynthesis are often used to predict the effect of environmental conditions on net rates of leaf CO2 assimilation (Farquhar et al., 1980; von Caemmerer, 2000, 2013; Walker et al., 2013). With climate change, there is increased interest in modeling and understanding the effects of changes in temperature and CO2 concentration on photosynthesis. The biochemical models of photosynthesis are primarily driven by the kinetic properties of the enzyme Rubisco, the primary carboxylating enzyme of the C3 photosynthetic pathway, catalyzing the reaction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) with either CO2 or oxygen. However, the CO2-concentrating mechanism in C4 photosynthesis utilizes carbonic anhydrase (CA) to help maintain the chemical equilibrium of CO2 with HCO3− and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc) to catalyze the carboxylation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) with HCO3−. These reactions ultimately provide the elevated levels of CO2 to the compartmentalized Rubisco (Edwards and Walker, 1983). In C4 plants, it has been demonstrated that PEPc, Rubisco, and CA can limit rates of CO2 assimilation and influence the efficiency of the CO2-concentrating mechanism (von Caemmerer, 2000; von Caemmerer et al., 2004; Studer et al., 2014). Therefore, accurate modeling of leaf photosynthesis in C4 plants in response to future climatic conditions will require temperature parameterizations of Rubisco, PEPc, and CA kinetics from C4 species.

Modeling C4 photosynthesis relies on the parameterization of both PEPc and Rubisco kinetics, making it more complex than for C3 photosynthesis (Berry and Farquhar, 1978; von Caemmerer, 2000). However, the activity of CA is not included in these models, as it is assumed to be nonlimiting under most conditions (Berry and Farquhar, 1978; von Caemmerer, 2000). This assumption is implemented by modeling PEPc kinetics as a function of CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) and not HCO3− concentration, assuming CO2 and HCO3− are in chemical equilibrium. However, there are questions regarding the amount of CA activity needed to sustain rates of C4 photosynthesis and if CO2 and HCO3− are in equilibrium (von Caemmerer et al., 2004; Studer et al., 2014).

The most common steady-state biochemical models of photosynthesis are derived from the Michaelis-Menten models of enzyme activity (von Caemmerer, 2000), which are driven by the Vmax and the Km. Both of these parameters need to be further described by their temperature responses to be used to model photosynthesis in response to temperature. However, the temperature response of plant CA activity has not been completed above 17°C, and there is no known measured temperature response of Km HCO3− for PEPc (KP). Alternatively, Rubisco has been well studied, and there are consistent differences in kinetic values between C3 and C4 species at 25°C (von Caemmerer and Quick, 2000; Kubien et al., 2008), but the temperature responses, including both carboxylation and oxygenation reactions, have only been performed in C3 species (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013).

Here, we present the temperature dependency of Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation reactions, PEPc kinetics for HCO3−, and CA hydration from 10°C to 40°C from the C4 species Setaria viridis (succession no., A-010) measured using membrane inlet mass spectrometry. Generally, the 25°C values of the Rubisco parameters were similar to previous measurements of C4 species. The temperature response of the maximum rate of Rubisco carboxylation (Vcmax) was high compared with most previous measurements from both C3 and C4 species, and the temperature response of the Km for oxygenation (KO) was low compared with most previously measured species. Taken together, the modeled temperature responses of Rubisco activity in S. viridis were similar to the previously reported temperature responses of some C3 species. Additionally, the temperature response of the maximum rate of PEPc carboxylation (Vpmax) was similar to previous measurements. However, the temperature response of KP was lower than what has been predicted (Chen et al., 1994). For CA, deactivation of the hydration activity was observed above 25°C. Additionally, models of CA and PEPc show that CA activity limits HCO3− availability to PEPc above 15°C, suggesting that CA limits PEP carboxylation rates in S. viridis when compared with the assumption that CO2 and HCO3− are in full chemical equilibrium.

RESULTS

Rubisco Temperature Response

The Vcmax and maximum rate of Rubisco oxygenation (Vomax), the Km for carboxylation (KC) and KO, and the specificity of the enzyme for CO2 over oxygen (SC/O) were measured simultaneously using membrane inlet mass spectrometry from 10°C to 40°C on crude leaf extracts of S. viridis (Table I). The maximum turnover rates for carboxylation (kcatCO2) and oxygenation (kcatO2) were determined at 25°C using combined spectrophotometry and radiolabeled binding of the enzyme. At 25°C, the values of kcatCO2, kcatO2, KC, and KO for S. viridis are within ranges previously measured for other C4 species (Yeoh et al., 1980; Sage and Seemann, 1993; Kubien et al., 2008). At 25°C, the kcatCO2 was 5.44 ± 0.44 mol CO2 mol−1 site s−1, and the KC and KO were 94.7 ± 15.1 Pa and 28.9 ± 5.4 kPa, respectively. The measured SC/O in S. viridis at 25°C was 1,610 ± 66 Pa Pa−1. The ratio of the maximum carboxylation rate to the maximum oxygenation rate (Vcmax/Vomax) at 25°C was 5.54 ± 0.73, and the ratio of the Km for oxygenation to carboxylation (KO/KC) had a 25°C value of 0.31 ± 0.04 kPa Pa−1.

Table I. Measured values at 25°C, modeled values at 25°C (k25), and Ea using the equation parameter = k25exp(Ea(Tk − 298.15)/(298.15RTk)) for all measured temperature responses ± se.

For parameters kCA and Vpmax, a deactivation was included using the model parameter = k25exp(Ea(Tk − 298.15)/(298.15RTk))(1 + exp((298.15ΔS − Hd)/(298.15R)))/(1 + exp((TkΔS − Hd)/(TkR))), where Tk is the temperature in Kelvin, R is the molar gas constant, ΔS is the entropy factor, and Hd is the heat of deactivation.

| Parameter | Units | Measured at 25°C | k25 | Ea | ΔS | Hd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kJ mol−1 | kJ mol−1 K−1 | kJ mol−1 | ||||

| kCA | μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 Pa−1 | 124 ± 6 | ||||

| Normalized to 1 at 25°C | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 40.9 ± 70.7 | 0.21 ± 0.19 | 64.5 ± 50.9 | |

| kh | s−1 | 0.039 ± 0.000 | 0.038 ± 0.000 | 95.0 ± 1.0 | – | – |

| Vpmax | μmol HCO3− m−2 s−1 | 450 ± 16 | ||||

| Normalized to 1 at 25°C | 1 | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 94.8 ± 40.8 | 0.25 ± 0.12 | 73.3 ± 39.6 | |

| KP | Pa CO2 | 16.0 ± 1.3 | 13.9 ± 1.0 | 36.3 ± 2.4 | – | – |

| μm HCO3− | 62.8 ± 5.0 | 60.5 ± 2.4 | 27.2 ± 2.8 | – | – | |

| kcatCO2 | mol CO2 mol−1 site s−1 | 5.44 ± 0.44 | ||||

| Vcmax | Normalized to 1 at 25°C | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 78.0 ± 4.1 | – | – |

| Vomax/Vcmax at 25°C | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 55.3 ± 6.2 | – | – | |

| KC | Pa of CO2 | 94.7 ± 15.1 | 121 ± 7 | 64.2 ± 4.5 | – | – |

| KO | kPa of oxygen | 28.9 ± 5.4 | 29.2 ± 1.9 | 10.5 ± 4.8 | – | – |

| SC/O | Pa Pa−1 | 1,610 ± 66 | 1,310 ± 52 | −31.1 ± 2.9 | – | – |

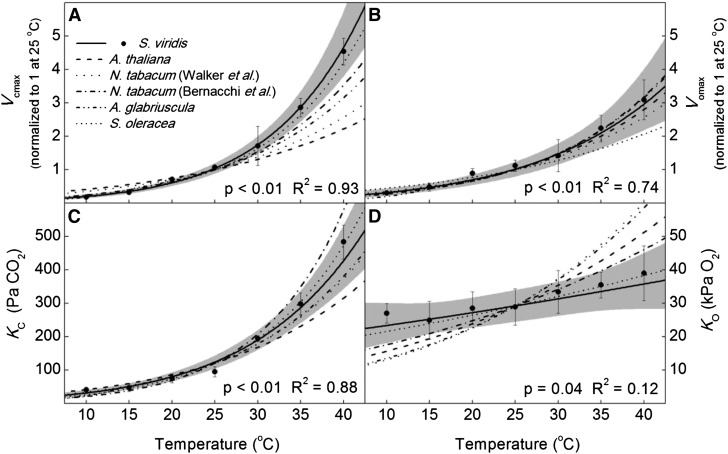

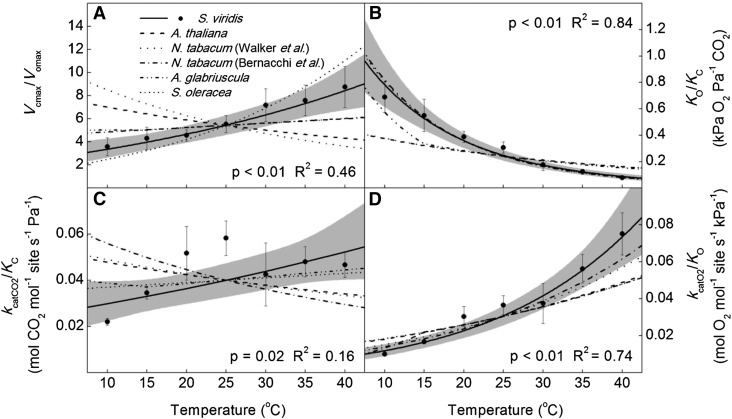

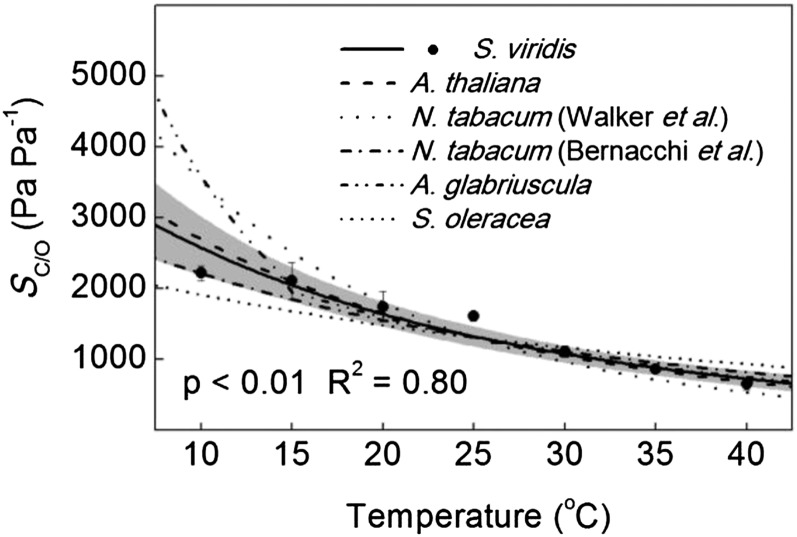

The Vcmax increased exponentially from 10°C to 40°C, with an energy of activation (Ea) of 78.0 ± 4.1 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 1). The temperature response of Vomax was lower compared with Vcmax, with an Ea equal to 55.3 ± 6.2 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 1). The KC and KO had Ea values of 64.2 ± 4.5 and 10.5 ± 4.8 kJ mol−1, respectively (Fig. 1). The Vcmax/Vomax increased from 10°C to 40°C (Fig. 2), but the KO/KC decreased with temperature (Fig. 2). The ratio of the catalytic rate of carboxylation to the KC and the catalytic rate of oxygenation to KO increased with temperature (Fig. 2). The SC/O decreased with temperature from 10°C to 40°C, with an Ea value of −31.1 ± 2.9 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Temperature responses of Rubisco kinetic parameters in S. viridis compared with corresponding values from the literature normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. The Vcmax (A), Vomax (B), KC (C), and KO (D) were determined using membrane inlet mass spectrometry on crude leaf extracts of S. viridis at pH 7.7 (at 25°C). The solid lines are the modeled temperature responses from this report (Table I), with the 95% confidence intervals shaded in gray. Dashed lines are temperature responses from previous reports normalized to S. viridis at 25°C (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). Black circles are the means of four technical replicates ± se. P values refer to the significance of the temperature response from zero, and adjusted R2 values describe the amount of variation in the measured parameter explained by the model.

Figure 2.

Temperature responses of the ratios of Rubisco parameters in S. viridis compared with corresponding values from the literature normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. Vcmax/Vomax (A), KO/KC (B), kcatCO2/KC (C), and kcatO2/KO (D) were calculated from data presented in Figure 1. The solid lines are the modeled temperature responses from this report, with the 95% confidence intervals in gray. Dashed lines are temperature responses from previous reports normalized to S. viridis at 25°C (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). Black circles are the means of four technical replicates ± se. P values refer to the significance of the temperature response from zero, and adjusted R2 values describe the amount of variation in the measured parameter explained by the model.

Figure 3.

Temperature responses of SC/O compared with corresponding values from the literature normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. Black circles represent the averages of four technical replicates ± se of S. viridis measured on crude leaf extracts using membrane inlet mass spectrometry. The solid line is the modeled temperature response from this report (Table I), with the 95% confidence interval in gray. Dashed lines are temperature responses from previous reports normalized to S. viridis at 25°C (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). The P value refers to the significance of the temperature response from zero, and the adjusted R2 value describes the amount of variation in the measured parameter explained by the model.

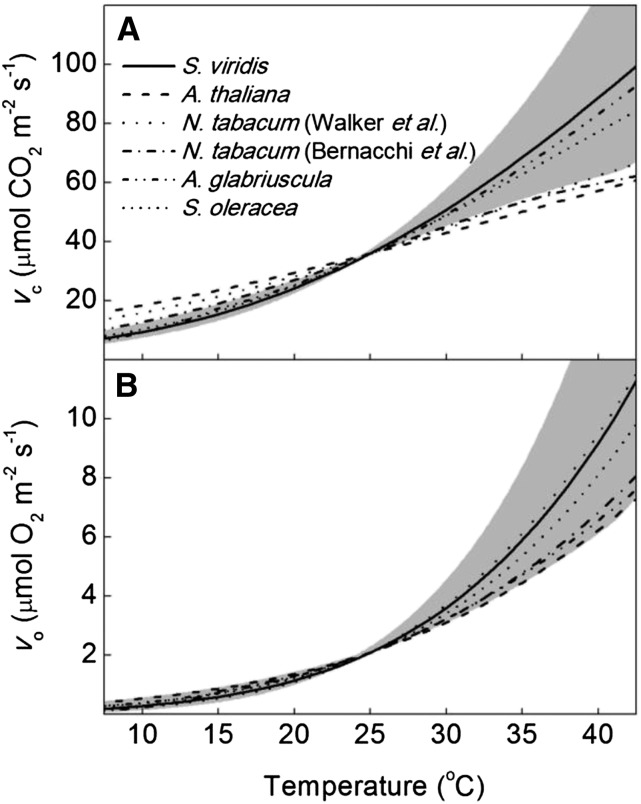

Rates of Rubisco carboxylation (vc) and oxygenation (vo) were modeled at pCO2 of 400 Pa and oxygen partial pressure (pO2) of 35 kPa in response to temperature for kinetic parameters from S. viridis and previously published values normalized to S. viridis values at 25°C (Fig. 4). The temperature response of vc in S. viridis (Fig. 4) was similar to those measured in vitro in Atriplex glabriuscula (Badger and Collatz, 1977) and Spinacea oleracea (Jordan and Ogren, 1984) but larger than those measured in vivo Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Walker et al., 2013) and Nicotiana tabacum (Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). The temperature response of vo in S. viridis was similar to previous measurements (Fig. 4). Additionally, the temperature dependency of S. viridis was compared with nonnormalized temperature responses of vc and vo from previous measurements (Supplemental Fig. S1). Under the low pCO2 (25 Pa) and ambient pO2 (21 kPa) expected in mesophyll of a C3 leaf, vc was lower in S. viridis (Supplemental Fig. S1) compared with the C3 species (Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013), with the exception of A. glabriuscula (Badger and Collatz, 1977). The S. viridis vo response (Supplemental Fig. S1) was similar in all reports with the exception of A. glabriuscula (Badger and Collatz, 1977), which had a lower value above 35°C. At high pCO2, the predicted rates of vc for S. viridis (Supplemental Fig. S1) were not different from those for S. oleracea (Jordan and Ogren, 1984), N. tabacum (Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002), and, below 25°C, Arabidopsis (Walker et al., 2013). At high pCO2, S. viridis had a higher predicted vo (Supplemental Fig. S1) at all temperatures compared with the C3 species (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Walker et al., 2013), with the exception of N. tabacum (Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002) above 25°C.

Figure 4.

Temperature responses of vc (A) and vo (B) modeled at pCO2 and pO2 expected at the site of Rubisco carboxylation in a C4 species (400 Pa of CO2 and 35 kPa of oxygen) compared with corresponding values from the literature normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. The solid lines are the modeled temperature responses of S. viridis from this report, with the 95% confidence intervals in gray. Dashed lines are temperature responses from previous reports normalized to S. viridis at 25°C (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). A Vcmax of 60 μmol m−2 s−1 was assumed.

PEPc Temperature Response

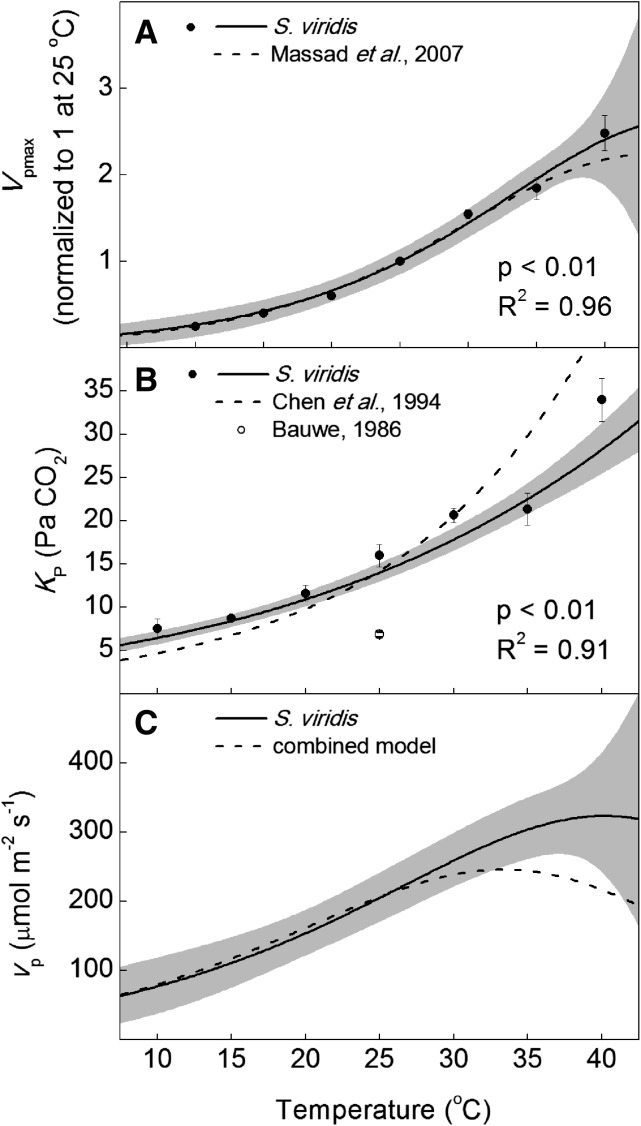

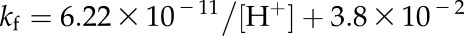

The kinetic parameters of PEPc were measured using membrane inlet mass spectrometry on crude leaf extracts of S. viridis from 10°C to 40°C (Table I; Supplemental Fig. S2). The Vpmax at 25°C was 450 ± 16 µmol m−2 s−1 when measured on freshly collected leaf tissue. The Vpmax increased with temperature from 10°C to 40°C, with an apparent deactivation at 35°C and 40°C (Fig. 5), noted by a deviation from linearity when plotted as a log transformation (transformation not shown). The measured KP was 60.2 µm HCO3− at 25°C. The KP was calculated as 16 ± 1.3 Pa CO2 assuming a pH of 7.2 and a dissociation constant (pKa) of 6.12 appropriate for the mesophyll cytosol at 25°C (Jenkins et al., 1989). Values of KP increased exponentially from 10°C to 40°C, with an Ea of 36.3 ± 2.4 kJ mol−1, when modeled in pCO2 assuming full equilibrium with HCO3− (Fig. 5). The temperature dependency of leaf PEPc activity (vp) modeled at a mesophyll cytosol pCO2 of 12 Pa at all temperatures increased with temperature but plateaued between 35°C and 40°C (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Temperature response of PEPc parameters in S. viridis compared with corresponding temperature responses from the literature normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. The Vpmax (A), KP (B), and vp (C) were measured on crude leaf extracts with membrane inlet mass spectrometry. Calculations of KP assumed a constant leaf pH of 7.2 and a pKa appropriate for an ionic strength or 0.1 m (Jenkins et al., 1989), with a temperature dependency as described by Harned and Bonner (1945). The model of vp used a measured Vpmax of 450 μmol m−2 s−1 at 25°C and a constant mesophyll pCO2 of 12 Pa. The solid lines are the modeled temperature responses from this report (Table I), with 95% confidence intervals in gray. Dotted lines are the temperature responses for Vpmax for maize (Massad et al., 2007) and for KP (Chen et al., 1994) normalized to S. viridis at 25°C. Black circles are the means of three biological replicates ± se, and the white circle in B is the KP reported previously for maize ± se (Bauwe, 1986). P values refer to the significance of the temperature response from zero, and adjusted R2 values describe the amount of variation in the measured parameter explained by the model.

CA Temperature Response

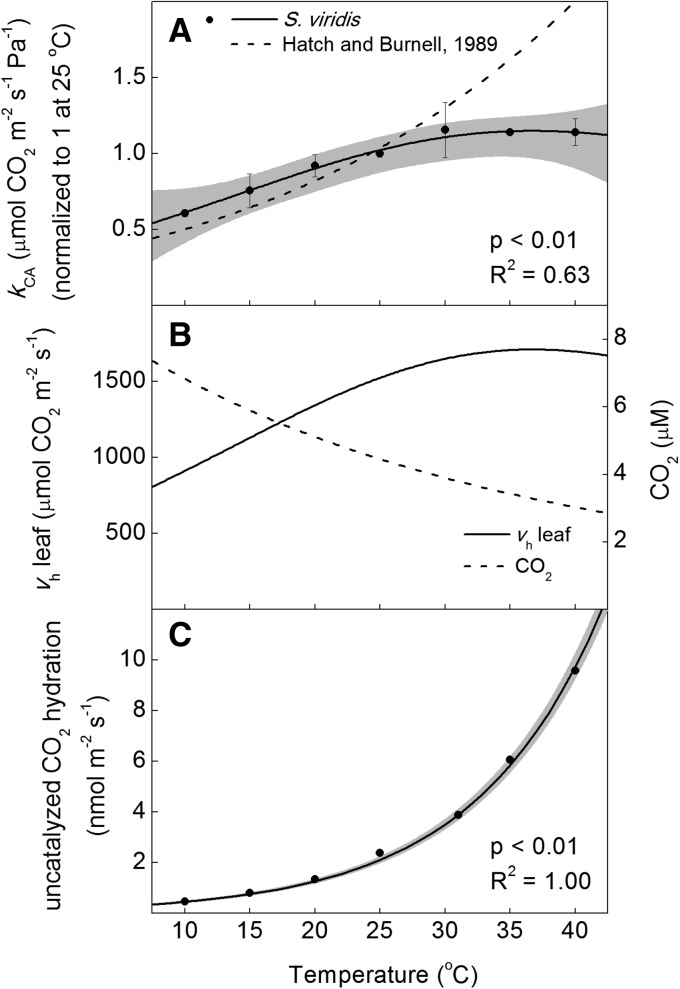

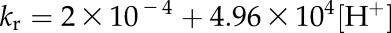

The rate constant for CA hydration activity (kCA) was determined from crude leaf extracts using membrane inlet mass spectrometry to measure rates of 18O exchange between labeled 13C18O2 and H216O (Table I; Supplemental Fig. S3). At 25°C, freshly collected leaf tissue of S. viridis had a kCA of 124 ± 6 µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 Pa−1. The kCA increased from 10°C to 30°C but plateaued from 30°C to 40°C (Fig. 6). When CA activity was modeled for an expected mesophyll pCO2 of 12 Pa, the hydration rate (vh) was 1,488 µmol m−2 s−1 at 25°C (Fig. 6). The temperature change in vh was identical to kCA because the mesophyll pCO2 was assumed to be 12 Pa at all temperatures. Alternatively, the temperature response of the uncatalyzed rate of CO2 hydration in the leaf increased exponentially with temperature and is described by the rate constant, having an Ea of 95 ± 1.0 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 6). The Ea for the uncatalyzed rate is much higher than that for the catalyzed rate; however, the uncatalyzed rate is at least 105 times lower from 10°C to 40°C (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Temperature responses of CA parameters in S. viridis. A, The kCA was measured on crude leaf extracts using membrane inlet mass spectrometry and is compared with a previously published maximum hydration rate from maize (Hatch and Burnell, 1990) normalized at 25°C. B, The kCA from S. viridis was used to calculate leaf CA activity (vh; solid line) assuming a constant 12 Pa of CO2 above the liquid phase and the temperature-dependent change in dissolved CO2 (dashed line). C, Temperature responses of the uncatalyzed CO2 vh for the mesophyll cytosol calculated assuming a cytosol volume of 30 μL mg−1 chlorophyll (Badger and Price, 1994) and 200 mg chlorophyll m−2 leaf tissue at a constant 12 Pa of CO2. Black circles represent average values of three biological replicates, each with three technical replicates per temperature, ± se (n = 3). The solid lines represent models fit to measured data (Table I), with the 95% confidence intervals shown in gray. Calculations of the catalyzed and uncatalyzed vh account for changes in pH and CO2 that occurred when measuring at different temperatures (Supplemental Fig. S1); however, it was assumed that the pH of the mesophyll cytosol was buffered at 7.2. P values refer to the significance of the temperature response from zero, and adjusted R2 values describe the amount of variation in the measured parameter explained by the model.

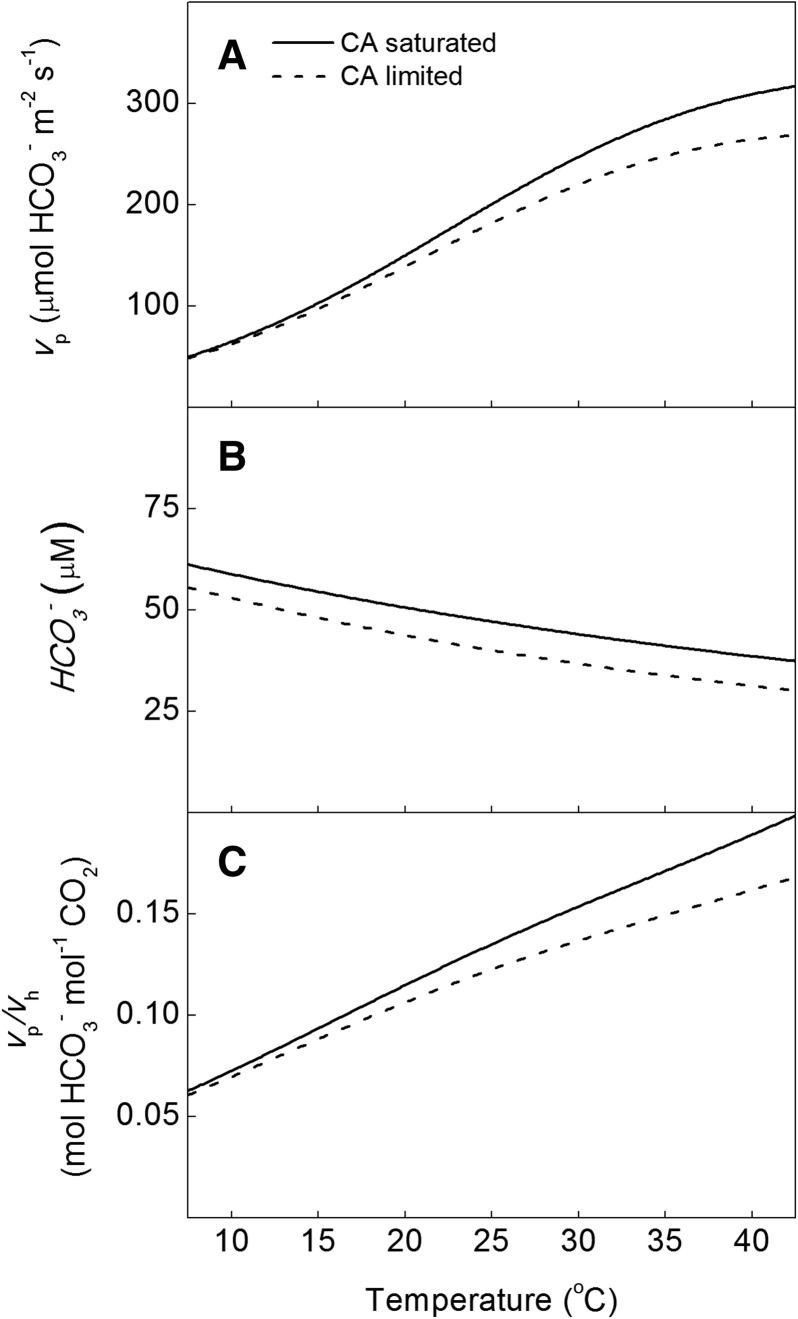

The supply of HCO3− provided to PEPc by the hydration activity of CA was investigated using the model of Hatch and Burnell (1990) and the temperature responses reported here (Fig. 7). At 12 Pa CO2 and pH 7.2, CA activity limits PEPc carboxylation above 15°C by more than 5% compared with assuming full chemical equilibrium between CO2 and HCO3− (Fig. 7). Additionally, the modeled HCO3− concentration is lower at all temperatures compared with the concentration assuming HCO3− is in full equilibrium with CO2 (Fig. 7). The modeled activity of CA relative to PEPc activity (vp/vh) increased with temperature and is lower when vp is modeled based on HCO3− availability provided by CA activity compared with assuming CO2 and HCO3− are in chemical equilibrium (Fig. 7). It should be noted that the modeled limitation of CA to PEPc depends on temperature, pH, and ionic strength, as all these conditions influence the ratio of CO2 to HCO3−.

Figure 7.

Effects of CA activity on PEPc activity with temperature. A, vp modeled assuming chemical equilibrium (CA saturated) and calculated based on CA activity (CA limited). B, Concentration of HCO3− at equilibrium and calculated based on CA activity. C, vp/vh calculated assuming equilibrium and based on CA activity. Calculations assume a constant leaf pH of 7.2 and a 25°C hydration as well as dehydration rate constants described by Jenkins et al. (1989), with the temperature responses for the rate constants described by Sanyal and Maren (1981) applied. The model used a measured Vpmax of 450 μmol m−2 s−1, a measured kCA of 124 μmol m−2 s−1 Pa−1 at 25°C, and a constant mesophyll pCO2 of 12 Pa at all temperatures.

DISCUSSION

Rubisco Temperature Response

The C4 biochemical model of photosynthesis uses both carboxylase and oxygenase parameters of Rubisco (von Caemmerer, 2000); therefore, it is important to know the temperature dependency of both reactions in order to model C4 photosynthesis in response to temperature. Rubisco kinetic parameters have been measured in numerous C3 and C4 species at 25°C (Yeoh et al., 1980; Sage and Seemann, 1993; Kubien et al., 2008; Galmés et al., 2014); however, there are few studies that measure both Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation parameters from C4 species (Kubien et al., 2008; Cousins et al., 2010). The S. viridis 25°C values of Rubisco parameters are similar to previous measurements of C4 species. Notably, the KC value is at the higher end of measured C4 species but similar to Setaria italica (Jordan and Ogren, 1983) and lower than Setaria geniculata (Yeoh et al., 1980). The SC/O was low compared with Flaveria C4 spp. and maize (Zea mays; Kubien et al., 2008; Cousins et al., 2010) but larger than a previous measure of S. italica (Jordan and Ogren, 1983). However, the values reported here fit the tenuous understanding that C4 species have higher KC and kcatCO2 values and lower SC/O values compared with C3 species (Yeoh et al., 1980; Sage, 2002; Kubien et al., 2008; Savir et al., 2010; Whitney et al., 2011).

Currently, there are no known temperature dependencies of the full suite of Rubisco kinetics for a C4 enzyme. However, for C3 plants, there are two in vitro temperature responses of both carboxylase and oxygenase parameters (A. glabriuscula and S. oleracea) and three in vivo measurements from Arabidopsis and N. tabacum (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). These C3 temperature responses are typically applied to C4 Rubisco 25°C values, with the assumption that the temperature response is similar between these two photosynthetic functional types (Berry and Farquhar, 1978). However, this assumption has not been tested for the Rubisco parameters used in the C4 model of photosynthesis, and the previous comparisons of C3 and C4 Rubisco temperature responses have been limited to kcatCO2 and SC/O (Björkman and Pearcy, 1970; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Sage, 2002; Galmés et al., 2015) and a recent investigation comparing kcatCO2, KC, and SC/O between C3, C4, and intermediate species within the Flaveria lineage (Perdomo et al., 2015). However, these studies lack comparisons of the oxygenation parameters kcatO2 and KO needed to accurately predict the temperature response of carboxylation and oxygenation. Here, we report the temperature response of complete C4 Rubisco kinetics from 10°C to 40°C. In general, the temperature responses of Rubisco parameters in S. viridis were similar to reports from previous C3 species; however, variation exists in how individual kinetic parameters change with temperature in relation to one another.

For example, SC/O has been reported to decrease with temperature, but the reason for the decrease has been debated (Badger and Andrews, 1974; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Walker et al., 2013). However, there are no consistent trends in the literature on the temperature response of Vcmax/Vomax, suggesting that the temperature responses of Vcmax and Vomax are nearly identical (Badger and Andrews, 1974; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2013). Additionally, there appears to be very little Vcmax/KC temperature dependency (Fig. 2). The decrease of KO/KC and increase of Vomax/KO with temperature are consistent between studies (Fig. 2; Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013). Taken together, it is likely that the insensitivity of KO to temperature drives the decrease in specificity in Rubisco, because between species and measurement methods, the temperature responses of Vcmax, Vomax, and KC are similar and are higher compared with KO (Badger and Collatz, 1977; Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Bernacchi et al., 2001, 2002; Walker et al., 2013).

For comparing the predicted vc and vo, the values were plotted in units of mol CO2 mol−1 site s−1, so that a comparison of the predicted tradeoff of kcatCO2 and KC between C3 and C4 species could be analyzed with temperature. Because no kcatCO2 values in these units are available for three of the previous four temperature response publications, the in vitro value of 3.3 mol CO2 mol−1 site s−1 measured by Walker et al. (2013) for both Arabidopsis and N. tabacum was applied to all species except S. viridis. At low pCO2, the previously reported C3 Rubisco has higher vc compared with the S. viridis enzyme, with the exception of A. glabriuscula, because the KC for A. glabriuscula at 25°C is 3 times larger than for other C3 enzymes included in this analysis. However, at high pCO2, the S. viridis Rubisco has a slightly higher vc compared with the C3 enzymes. The minimal difference of vc observed between C3 and S. viridis Rubisco at high pCO2 is likely the result of the high KC measured in S. viridis.

The absolute values of kinetic parameters measured at 25°C for S. viridis are similar to previously published values from C4 plants, which generally differ from C3 parameters (Yeoh et al., 1980; von Caemmerer and Quick, 2000; Kubien et al., 2008; Savir et al., 2010; Whitney et al., 2011). However, there is less support in the literature for differences in the temperature response between C3 and C4 Rubisco (Jordan and Ogren, 1984; Sage, 2002; Galmés et al., 2015; Perdomo et al., 2015). The Rubisco temperature responses of S. viridis presented here are similar to the available temperature responses of C3 species, suggesting a generally conserved variation in kinetic parameters. While the temperature response of Rubisco is becoming increasingly well studied, less work has focused on PEPc kinetics, especially the temperature response of KP.

PEPc Temperature Response

The temperature response of Vpmax presented here (Fig. 5) was similar to measurements from other species (Buchanan‐Bollig et al., 1984; Wu and Wedding, 1987; Chen et al., 1994; Massad et al., 2007), which showed a change in the temperature response above 25°C. While this change in the temperature response has been observed previously, the magnitude varies between studies and species (Buchanan‐Bollig et al., 1984; Wu and Wedding, 1987; Chen et al., 1994; Massad et al., 2007). It is unclear if there are differences in the temperature response of Vpmax between species, because there are not sufficient comparisons made within a single study.

The KP is important for modeling the response of PEPc to changes in HCO3− availability. However, the temperature response of KP has been left out of models of C4 photosynthesis (Berry and Farquhar, 1978; von Caemmerer, 2000) or a predicted temperature response has been used (Chen et al., 1994; Massad et al., 2007). This is in contrast to the incorporation of measured Rubisco temperature responses that have been used in the C4 model (Berry and Farquhar, 1978). The temperature response of KP measured here was lower than a predicted temperature response (Fig. 5; Chen et al., 1994); however, it should be noted that the temperature response from Chen et al. (1994) was not actually measured but selected to have a 2.1-fold change for every 10°C (Q10). Because the temperature dependency of Vpmax is similar between this study and Massad et al. (2007), the effect of differences in KP temperature response can be seen on modeled vp in Figure 5, where there is an 80 µmol m−2 s−1 increase in the optimum occurring 5°C higher. This shift in modeled vp suggests that the use of the measured KP presented here is important for estimates of Vpmax values based on leaf gas exchange.

CA Temperature Response

CA activity is considered necessary for C4 photosynthesis because it provides PEPc with HCO3− by facilitating the hydration of dissolved CO2 in the mesophyll cytosol (von Caemmerer et al., 2004). Additionally, the vp/vh can influence the isotopic CO2 exchange in C4 plants (Farquhar, 1983). However, the activity of CA is not included in models of C4 photosynthesis and is generally thought to have little effect on 13CO2 isotope exchange, because vp/vh is assumed to be low (Berry and Farquhar, 1978; Farquhar, 1983; von Caemmerer, 2000). However, in some C4 grass species, leaf activity (leaf vh) is reported to be just sufficient to maintain rates of C4 photosynthesis at 25°C (Hatch and Burnell, 1990; Cousins et al., 2008). Therefore, under conditions that limit leaf CO2 availability, the rate of leaf vh may restrict C4 photosynthesis and influence leaf CO2 isotope exchange. This limitation may be particularly important at temperatures higher than 25°C; however, the temperature response of leaf vh is poorly understood.

The measured 25°C values of leaf vh and the first-order kCA in S. viridis are 4-fold higher than previously published values for other C4 grasses (Cousins et al., 2008). Published CA activity varies widely between studies, species, tissue collection methods, and growth conditions (Hatch and Burnell, 1990; Gillon and Yakir, 2001; Affek et al., 2006; Cousins et al., 2008). This variation is poorly understood; however, it raises questions regarding CA responses to changes in growth conditions, particularly those that limit CO2 availability to the leaf such as drought and temperature.

The measured temperature response of kCA from 10°C to 25°C was similar to the 1.9-fold change for every 10°C(Q10) measured from 0°C to 17°C and intermediate to two isozymes of human CA measured from 0°C to 37°C, but it deviated at 30°C and above (Fig. 6A; Sanyal and Maren, 1981; Burnell and Hatch, 1988). The CA temperature response reported here plateaued between 25°C and 40°C, suggesting a deactivation of CA activity in S. viridis at temperatures above 25°C (Fig. 1). This apparent deactivation was not observed in previous studies (Sanyal and Maren, 1981; Burnell and Hatch, 1988).

As expected for a chemical reaction, the uncatalyzed rate of CO2 hydration increases exponentially (Fig. 1). The Ea reported here for the uncatalyzed rate constant of CO2 hydration at pH 8 was larger than that measured previously for pH 7.2 (Sanyal and Maren, 1981). Following the assumptions of Badger and Price (1994) regarding the volume of the mesophyll cytoplasm per unit of leaf area, the amount of the uncatalyzed CO2 hydration estimated in the mesophyll cytoplasm was 105 times lower than the leaf vh. The importance of the uncatalyzed rate when modeling isotopic discrimination is unclear and should be investigated further, but the estimated uncatalyzed rates presented here are insufficient to support rates of photosynthesis at any temperature (Fig. 6).

Using the steady-state model of Hatch and Burnell (1990), HCO3− concentration and vp were modeled using the temperature responses of kCA, Vpmax, and KP measured for S. viridis assuming a constant mesophyll pCO2 of 12 Pa. This model was compared with the assumption of current gas-exchange models that assume HCO3− is at chemical equilibrium with CO2 in the mesophyll cytosol (Fig. 7). The results show that CA limits vp by more than 5% above 15°C when compared with the full equilibrium model due to reduced HCO3− availability to PEPc (Fig. 7). These results are contradictory to the assumptions of gas-exchange models, which assume that CA activity is high enough to maintain full chemical equilibrium between CO2 and HCO3−, and may have important implications for comparing models and measurements of C4 photosynthesis. For example, in wild-type maize plants presented by Studer et al. (2014), there is an 80% reduction in in vivo compared with in vitro Vpmax. The in vivo value is calculated from the initial slope of net CO2 assimilation against intercellular CO2 concentration (A-Ci curve); therefore, the lower Vpmax calculated from an A-Ci curve is possibly driven by inaccurate estimates of the conductance of CO2 from the intercellular air space to the mesophyll cytosol (gm) and the proposed disequilibrium between CO2 and HCO3− due to limiting CA activity. Both of these factors would lower the initial slope of an A-Ci curve and, therefore, in vivo estimates of Vpmax.

The CA limitation in wild-type maize is initially hard to reconcile with evidence from CA mutants showing little change in net CO2 assimilation, except for homozygous mutants at subambient CO2 (Studer et al., 2014). However, using the model of Hatch and Burnell (1990) combined with the PEPc-limited models of net CO2 assimilation (von Caemmerer, 2000) and the in vitro data set presented by Studer et al. (2014), the predicted apparent in vivo Vpmax in the wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous plants are 34, 33, and 13 μmol m−2 s−1, respectively. These values are similar to the gas-exchange estimates of in vivo Vpmax presented by Studer et al. (2014), reanalyzed here using just the linear portion of the A-Ci curves as 36 ± 2, 34 ± 2, and 16 ± 1 for the wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous plants, respectively. This demonstrates that the in vitro data of CA and PEPc activities used with the Hatch and Burnell (1990) model and the PEPc-limited models of net CO2 assimilation (von Caemmerer, 2000) can accurately predict subtle changes in leaf gas exchange measured in plants with low CA.

Although the difference between in vivo and in vitro PEPc can generally be predicted in the example presented above, there are still unknown factors that potentially regulate in vivo PEPc activity. Of critical importance for estimating in vivo Vpmax are the values of gm; however, there are no robust means for measuring gm in C4 plants, which also limits the accuracy of defining a CA limitation to gas-exchange measurements. Therefore, more work is needed to define the importance of CA in C4 photosynthesis, especially in linking leaf-level gas exchange to biochemical models in order to better define carbon flux through the C4 pathway.

CONCLUSION

Rubisco, PEPc, and CA are potentially rate-limiting steps in the photosynthetic assimilation of atmospheric CO2 in C4 plants. Therefore, the activity and kinetic properties of these enzymes are needed to accurately parameterize biochemical models of leaf CO2 exchange in response to changes in CO2 and temperature. To address this issue, the temperature responses of Rubisco carboxylation and oxygenation kinetics, PEPc carboxylation kinetics, and CA hydration reaction from the C4 plant S. viridis (succession no., A-010) were analyzed using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer. These findings suggest that the C4 Rubisco of S. viridis has a similar temperature response to previously measured C3 Rubisco, the KP of PEPc increases with temperature, and, although modeling shows that CA limits HCO3− availability to PEPc in S. viridis, it also supports previous findings that large changes in CA activity have minimal effect on net CO2 assimilation. These results advance our understanding of the temperature response of CO2 assimilation in C4 plants and help to better parameterize the models of C4 photosynthesis. However, more work is needed, including leaf gas-exchange and isotopic measurements, to determine the importance and implications of CA limitation to C4 photosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth Conditions

Seeds of Setaria viridis (A-010) were planted in 7.5-L pots with LC-1 Sunshine mix (Sun Gro Horticulture). Plants were grown in environmental growth chambers (Enconair Ecological GC-16) with a temperature of 28°C/18°C day/night, photoperiod of 16/8 h day/night, and light intensity of 1,000 µmol quanta m−2 s−1 at canopy level using 50% 400-W high-pressure sodium and 50% 400-W metal halide lighting. Relative humidity was not controlled and varied from 30% to 85% during the life of the plants as measured by the growth chamber. Plants were watered as needed and fertilized twice per week using Peters 20-20-20 (J.R. Peters) and supplemented with Sprint 330 iron chelate (BASF) as needed. Plants were grown for 6 weeks after germination and sampled periodically between 3 and 6 weeks.

Sample Preparation

CA Extraction

Leaf discs were extracted on ice in a glass homogenizer in 1 mL of 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.8), 1% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP), 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 2% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (P9599; Sigma-Aldrich). Crude extracts were centrifuged at 4°C for 1 min at 17,000g, and the supernatant was collected for immediate use in the CA assay.

PEPc Extraction

The midveins of youngest fully expanded leaves were removed, and the remaining tissue was cut into small pieces prior to grinding to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle. The frozen powder was transferred to an ice-cooled mortar containing extraction buffer and ground on ice using a pestle until fully homogenized. Approximately 2 g of leaf tissue was ground in 4 mL of 100 mm HEPES (pH 7.8), 10 mm DTT, 25 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaHCO3, 1% (w/v) PVPP, 0.5% (v/v) Triton, 33 µL of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for every gram of leaf tissue used, and sand. The extract was spun at 17,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and desalted using an Econo Pac 10DG column (Bio-Rad), filtered through a Millex GP 33-mm syringe-driven filter unit (Millipore), and then centrifuged using Amicon Ultra Ultracel 30K centrifugal filters (Millipore) at 4°C for 1 h at 4,000 rpm (3,000g). The layer maintained above the filter unit was collected, brought to 20% (v/v) glycerol, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until measured. Three individual plants were used, with one extraction per plant.

Rubisco Extraction

Rubisco extraction followed that of PEPc except that most Rubisco activity was found to be in the green layer of the pellet and not the supernatant following the first centrifugation. The supernatant was discarded, and the upper portion of the pellet was collected, avoiding sand and PVPP. The pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer and spun again at 4°C, for 9 s, up to 17,000g to remove large particulates. The supernatant was collected and run through Econo Pac 10DG desalting columns (Bio-Rad), and the dark green fraction was collected and centrifuged at 4°C, for 10 min, at 17,000g. Although no pellet formed, a gradient in color, from light green at the top of the tube to dark green at the bottom, was noted. Most Rubisco activity was found to be in the bottom half of the sample. The upper light green portion of the sample was discarded to concentrate Rubisco. The sample was brought to 20% (v/v) glycerol, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until measured. After being thawed for use, the extract was allowed to activate in 15 mm MgCl2 and 15 mm NaHCO3 for 10 min at room temperature before being placed on ice for the duration of the measurement. Measurements for a single oxygen level lasted approximately 1 h, and a single aliquot was used per oxygen level. A new aliquot was thawed for each of the four oxygen levels.

Extraction for Spectrophotometry

Rubisco activity and PEPc activity at 25°C were measured on freshly collected leaf discs homogenized on ice in 1 mL of 100 mm HEPES (pH 7.8), 1% (w/v) PVPP, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm DTT, 0.1% (v/v) Triton, and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail using a glass homogenizer. The extract was then centrifuged at 17,000g for 1 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant was activated in 15 mm MgCl2 and 15 mm NaHCO3 for 10 min at room temperature and placed on ice.

Membrane Inlet Mass Spectrometry

CA Measurements

CA activity was measured using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer to measure the rates of 18O2 exchange from labeled 13C18O2 to H216O with a total carbon concentration of 1 mm (Silverman, 1982; Badger and Price, 1989; Hatch and Burnell, 1990). The hydration rates were calculated from the enhancement in the rate of 18O loss over the uncatalyzed rate with the nonenzymatic first-order rate constant for the hydration of CO2 calculated for the assay pH 8.03 at 25°C using the equation from Jenkins et al. (1989). The measured temperature response was applied to the 25°C rate constant correcting for the change in assay pH at each temperature (Supplemental Fig. S3). The CO2 concentration was calculated using the temperature-appropriate pKa assuming an ionic strength of 0.1 m (Harned and Bonner, 1945), and the pCO2 was calculated using the temperature-appropriate Henry’s constant (Sander, 2015). The temperature response was determined on three biological replicates separately extracted and measured three times (technical replication) from frozen leaf tissue in 5°C increments from 10°C to 40°C. Total leaf CA activity at 25°C was determined from four biological replicates measured on fresh tissue.

PEPc and Rubisco Measurements

PEPc and Rubisco assays were conducted in a 600-μL temperature-controlled cuvette linked to a mass spectrometer as described by Cousins et al. (2010). CO2 and oxygen calibrations were made daily at the measurement temperature as described by Cousins et al. (2010), with the exception that no oxygen-zero or membrane consumption was determined, because it was assumed to be accounted for in the blank rate made immediately prior to measurement of the enzymatic rate. To determine the oxygen concentration dissolved in water during equilibrium with air, the temperature dependency of the Henry’s constant for oxygen was taken into account given the measurement temperature. Because calibrations account for the concentrations of CO2 and total inorganic carbon, the concentration of HCO3− was calculated as the difference between total inorganic carbon and CO2.

Measurements of PEPc bicarbonate kinetics were similar to the method presented by Cousins et al. (2010), except that only one oxygen level (approximately 80 µm) was used with five HCO3− concentrations ranging from 0 to 3,000 µm. The assay buffer contained 200 mm HEPES (pH 7.8; measured at 25°C), 20 mm MgCl2, 8 µg mL−1 CA, 5 mm Glc-6-P, and 4 mm PEP. For all measurement points, except the lowest HCO3−, 30 s were sampled prior to the initiation of the reaction as the blank rate; following a 30-s mixing period after the injection of PEP to initiate the reaction, the next 30 s were sampled as the enzymatic rate (Fig. 1). The blank rate was subtracted from the enzymatic rate. For the lowest HCO3− concentration, the slope was found to change rapidly over the course of 30 s; therefore, the slope was calculated every 5 s during the 30-s interval. Three biological replicates were measured in 5°C increments from 10°C to 40°C.

Measurements of Rubisco kinetics were made following the methods of Cousins et al. (2010). Samples were measured at four oxygen concentrations ranging from 40 to 1,600 µm, and five CO2 concentrations ranging from 10 to 200 µm at each oxygen level, for a total of 20 data points per measurement. Measurements were made in 5°C intervals from 10°C to 40°C, and four replicates were measured per temperature. The assay buffer contained 200 mm HEPES, 20 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm α-hydroxypyridinemethanesulfonic acid, 8 µg mL−1 CA, and 0.6 mm RuBP. A total of 20 to 100 µL of extract was added per measurement depending on the Rubisco concentration of the extract. One measurement initiating the reaction with RuBP was made at each oxygen concentration to test for any non-RuBP-dependent consumption of CO2 and oxygen. Non-RuBP-dependent consumption of CO2 and oxygen was considered negligible because it did not have a significant effect on the final calculations of Rubisco kinetic parameters.

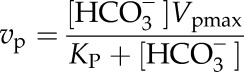

For PEPc measurements, vp and HCO3− concentration ([HCO3−]) were fit to the equation:

|

(1) |

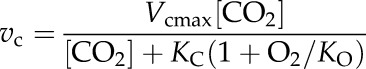

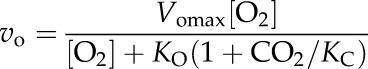

solving for Vpmax and KP. For Rubisco measurements, vc and vo were normalized by dividing all measured values by their average to give uniform weight during the fitting calculation. The normalized vc and vo, and corresponding CO2 concentration ([CO2]) and oxygen concentration ([O2]), were fit simultaneously to the following equations:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

solving for the parameters KC and KO. This was repeated using the nontransformed vc and vo values while holding KC and KO constant and solving for Vcmax and Vomax. The normalizing of data before solving for KC and KO improved the fits for vo. The KC and KO data obtained this way match the methods of plotting the apparent KC against oxygen concentration (von Caemmerer et al., 1994). All model fits were performed in the software package Origin 8 (OriginLab) using the nonlinear curve-fit function NLfit.

Enzyme Quantification

Rubisco Quantification

Rubisco activity was determined by enzyme-coupled spectrophotometry, monitoring the conversion rate of NAD (NADH) to NAD+ at 340 nm (Evolution 300 UV-Vis; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The 1-mL assay contained 100 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid (EPPS; pH 8 with NaOH), 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm creatine phosphate, 20 mm NaHCO3, 0.2 mm NADH, 12.5 units mL−1 creatine phosphokinase, 250 units mL−1 CA, 22.5 units mL−1 3-phosphoglyceric phosphokinase, 20 units mL−1 glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 56 units mL−1 triose-phosphate isomerase, 20 units mL−1 glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 10 μL of fresh leaf extract. The reaction was initiated with 0.5 mm RuBP. Rubisco content was determined from the stoichiometric binding of radiolabeled [14C]carboxy-arabinitolbisphosphate (14CABP; Collatz et al., 1979; Walker et al., 2013). For 14CABP binding assays, the extract was incubated in 1 mm 14CABP for 45 min at room temperature and then passed through a chromatography column (737-4731; Bio-Rad) packed with Sephadex G-50 fine beads (GE Healthcare Biosciences). Rubisco content was determined from the Rubisco-bound fractions using a scintillation counter and the specific activity of the 14CABP (Collatz et al., 1979; Walker et al., 2013).

The extract used to measure Rubisco kinetics was too viscous to move through the columns used for 14CABP site quantification. To normalize the temperature response of Vcmax and Vomax from the membrane inlet mass spectrometry measurements, each extract was measured at 25°C for Vcmax using enzyme-coupled spectrophotometry. The 25°C Vcmax value was used to normalize rates obtained from 10°C to 40°C using membrane inlet mass spectrometry. There was no significant difference between the 25°C values measured on the spectrophotometer compared with the membrane inlet mass spectrometer.

PEPc Quantification

A similar enzyme-coupled spectrophotometric assay as described above for Rubisco was conducted for PEPc to determine the leaf-level Vpmax. The 1-mL assay contained 100 mm EPPS (pH 8 NaOH), 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm Glc-6-P, 1 mm NaHCO3, 0.2 mm NADH, 12 units of malate dehydrogenase, and 10 μL of freshly collected leaf extract. The reaction was initiated with 4 mm PEP.

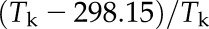

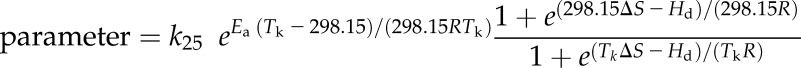

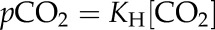

Modeling the Temperature Response

The temperature responses of the kinetic parameters kh (for the first order rate constant for the hydration of CO2), KP, Vcmax, Vomax, KC, KO, and SC/O were fit to the following equation:

|

(4) |

where k25 is the value of the parameter at 25°C and R is the molar gas constant (Badger and Collatz, 1977). The fit was calculated by taking the natural log of the data plotted against  using the linear function in Origin 8, such that the intercept was equal to ln(k25) and the slope was equal to Ea/(298.15R). The temperature responses of kCA and Vpmax were modeled to include the heat of deactivation (Hd) and entropy factor (ΔS) using the following equation (Farquhar et al., 1980; Leuning, 1997):

using the linear function in Origin 8, such that the intercept was equal to ln(k25) and the slope was equal to Ea/(298.15R). The temperature responses of kCA and Vpmax were modeled to include the heat of deactivation (Hd) and entropy factor (ΔS) using the following equation (Farquhar et al., 1980; Leuning, 1997):

|

(5) |

This model fitting was performed using the nonlinear curve-fit function NLfit in Origin 8.

Modeling the Supply of HCO3− by CA

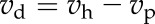

The model of Hatch and Burnell (1990) was used to calculate the CA-limited model (Fig. 7). The rates of PEP carboxylation and HCO3− concentration were calculated by solving for the following equations:

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

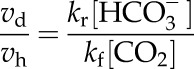

where vd is the rate of HCO3− dehydration catalyzed by CA, kr is the uncatalyzed rate constant for the reverse reaction, kf is the uncatalyzed rate constant for the forward reaction, and KH is the Henry’s law constant used to determine the concentration of CO2 for any given pCO2 at the appropriate temperature. The pCO2 was held constant at 12 Pa. The uncatalyzed rates of the forward and reverse reactions at 25°C and pH 7.2 were calculated using the following equations from Jenkins et al. (1989):

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

where the temperature response of kf and kr measured by Sanyal and Maren (1981) for pH 7.2 was applied.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Non-normalized temperature response of vc and vo.

Supplemental Figure S2. Measurement of PEPc kinetics.

Supplemental Figure S3. Measurement of CA parameters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Murray Badger and Connor Bollinger-Smith for helping to establish our membrane inlet mass spectrometry protocol for Rubisco, Chuck Cody for maintaining plant growth facilities, and Susanne von Caemmerer and past and current members of Cousins laboratory for helpful and insightful discussions.

Glossary

- RuBP

ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- PEPc

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

- pCO2

CO2 partial pressure

- KP

temperature response of Km HCO3− for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- Vcmax

maximum rate of Rubisco carboxylation

- KO

Km for oxygenation

- Vpmax

maximum rate of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase carboxylation

- Vomax

maximum rate of Rubisco oxygenation

- KC

Km for carboxylation

- SC/O

specificity of the enzyme for CO2 over oxygen

- kcatCO2

maximum turnover rate for carboxylation

- kcatO2

maximum turnover rate oxygenation

- Vcmax/Vomax

ratio of the maximum carboxylation rate to the maximum oxygenation rate

- KO/KC

ratio of the Km for oxygenation to carboxylation

- Ea

energy of activation

- vc

Rubisco carboxylation

- vo

Rubisco oxygenation

- pO2

oxygen partial pressure

- vp

temperature dependency of leaf phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity

- kCA

rate constant for carbonic anhydrase hydration activity

- vh

hydration rate

- vp/vh

activity of carbonic anhydrase relative to phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity

- A-Ci curve

initial slope of net CO2 assimilation against intercellular CO2 concentration

- gm

conductance of CO2 from the intercellular air space to the mesophyll cytosol

- PVPP

polyvinylpolypyrrolidone

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- 14CABP

[14C]carboxy-arabinitolbisphosphate

- kh

Henry’s constant

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Department of Energy (grant no. DE–FG02–09ER16062), by the National Science Foundation (Major Research Instrumentation grant no. 0923562), and by the Seattle chapter of the Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation (fellowship to R.A.B.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Affek HP, Krisch MJ, Yakir D (2006) Effects of intraleaf variations in carbonic anhydrase activity and gas exchange on leaf C18OO isoflux in Zea mays. New Phytol 169: 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ (1974) Effects of CO2, O2 and temperature on a high-affinity form of ribulose diphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase from spinach. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 60: 204–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Collatz GJ (1977) Studies on the kinetic mechanism of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and oxygenase reactions, with particular reference to the effect of temperature on kinetic parameters. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 76: 355–361 [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD (1989) Carbonic anhydrase activity associated with the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Physiol 89: 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD (1994) The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 45: 369–392 [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H. (1986) An efficient method for the determination of Km values for HCO3− of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase. Planta 169: 356–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi C, Singsaas E, Pimentel C, Portis A Jr, Long S (2001) Improved temperature response functions for models of Rubisco‐limited photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 24: 253–259 [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Portis AR, Nakano H, von Caemmerer S, Long SP (2002) Temperature response of mesophyll conductance: implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiol 130: 1992–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Farquhar G (1978) The CO2 concentrating function of C4 photosynthesis: a biochemical model. In Hall D, Coombs J, Goodwin T, eds, Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on Photosynthesis. Biochemical Society, London, pp 119–131 [Google Scholar]

- Björkman O, Pearcy RW (1970) Effect of growth temperature on the temperature dependence of photosynthesis in vivo and on CO2 fixation by carboxydismutase in vitro in C3 and C4 species. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 70: 511–520 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan‐Bollig IC, Kluge M, Müller D (1984) Kinetic changes with temperature of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase from a CAM plant. Plant Cell Environ 7: 63–70 [Google Scholar]

- Burnell JN, Hatch MD (1988) Low bundle sheath carbonic anhydrase is apparently essential for effective C4 pathway operation. Plant Physiol 86: 1252–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DX, Coughenour M, Knapp A, Owensby C (1994) Mathematical simulation of C4 grass photosynthesis in ambient and elevated CO2. Ecol Modell 73: 63–80 [Google Scholar]

- Collatz G, Badger M, Smith C, Berry J (1979) A radioimmune assay for RuP2 carboxylase protein. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book 78: 171–175 [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S (2008) C4 photosynthetic isotope exchange in NAD-ME- and NADP-ME-type grasses. J Exp Bot 59: 1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Ghannoum O, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR (2010) Simultaneous determination of Rubisco carboxylase and oxygenase kinetic parameters in Triticum aestivum and Zea mays using membrane inlet mass spectrometry. Plant Cell Environ 33: 444–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Walker DA (1983) C3, C4: Mechanisms, and Cellular and Environmental Regulation, of Photosynthesis. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. (1983) On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol 10: 205–226 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Andralojc PJ, Conesa MA, Keys AJ, Parry MA, Flexas J (2014) Expanding knowledge of the Rubisco kinetics variability in plant species: environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant Cell Environ 37: 1989–2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Copolovici LO, Hermida-Carrera C, Niinemets Ü (2015) Temperature responses of the Rubisco maximum carboxylase activity across domains of life: phylogenetic signals, trade-offs, and importance for carbon gain. Photosynth Res 123: 183–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillon J, Yakir D (2001) Influence of carbonic anhydrase activity in terrestrial vegetation on the 18O content of atmospheric CO2. Science 291: 2584–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned HS, Bonner FT (1945) The first ionization of carbonic acid in aqueous solutions of sodium chloride. J Am Chem Soc 67: 1026–1031 [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD, Burnell JN (1990) Carbonic anhydrase activity in leaves and its role in the first step of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 93: 825–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CL, Furbank RT, Hatch MD (1989) Mechanism of C4 photosynthesis: a model describing the inorganic carbon pool in bundle sheath cells. Plant Physiol 91: 1372–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL (1983) Species variation in kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys 227: 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL (1984) The CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: dependence on ribulosebisphosphate concentration, pH and temperature. Planta 161: 308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubien DS, Whitney SM, Moore PV, Jesson LK (2008) The biochemistry of Rubisco in Flaveria. J Exp Bot 59: 1767–1777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuning R. (1997) Scaling to a common temperature improves the correlation between the photosynthesis parameters Jmax and Vcmax. J Exp Bot 48: 345–347 [Google Scholar]

- Massad RS, Tuzet A, Bethenod O (2007) The effect of temperature on C4-type leaf photosynthesis parameters. Plant Cell Environ 30: 1191–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo JA, Cavanagh AP, Kubien DS, Galmés J (2015) Temperature dependence of in vitro Rubisco kinetics in species of Flaveria with different photosynthetic mechanisms. Photosynth Res 124: 67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. (2002) Variation in the kcat of Rubisco in C3 and C4 plants and some implications for photosynthetic performance at high and low temperature. J Exp Bot 53: 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Seemann JR (1993) Regulation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity in response to reduced light intensity in C4 plants. Plant Physiol 102: 21–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander R. (2015) Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos Chem Phys 15: 4399–4981 [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal G, Maren TH (1981) Thermodynamics of carbonic anhydrase catalysis: a comparison between human isoenzymes B and C. J Biol Chem 256: 608–612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T (2010) Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3475–3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman DN. (1982) Carbonic anhydrase: oxygen-18 exchange catalyzed by an enzyme with rate-contributing proton-transfer steps. Methods Enzymol 87: 732–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer AJ, Gandin A, Kolbe AR, Wang L, Cousins AB, Brutnell TP (2014) A limited role for carbonic anhydrase in C4 photosynthesis as revealed by a ca1ca2 double mutant in maize. Plant Physiol 165: 608–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2000) Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2013) Steady-state models of photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1617–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Hudson GS, Andrews TJ (1994) The kinetics of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta 195: 88–97 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Quick WP (2000) Rubisco: physiology in vivo. In Leegood RC, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S, eds, Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 85–113 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Quinn V, Hancock N, Price G, Furbank R, Ludwig M (2004) Carbonic anhydrase and C4 photosynthesis: a transgenic analysis. Plant Cell Environ 27: 697–703 [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Ariza LS, Kaines S, Badger MR, Cousins AB (2013) Temperature response of in vivo Rubisco kinetics and mesophyll conductance in Arabidopsis thaliana: comparisons to Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Environ 36: 2108–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Houtz RL, Alonso H (2011) Advancing our understanding and capacity to engineer nature’s CO2-sequestering enzyme, Rubisco. Plant Physiol 155: 27–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MX, Wedding RT (1987) Temperature effects on phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase from a CAM and a C4 plant: a comparative study. Plant Physiol 85: 497–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh HH, Badger MR, Watson L (1980) Variations in Km(CO2) of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase among grasses. Plant Physiol 66: 1110–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.