Metabolomics-based integrative approaches provide better understanding of gene function, pathway structure, and regulation.

Abstract

Huge insight into molecular mechanisms and biological network coordination have been achieved following the application of various profiling technologies. Our knowledge of how the different molecular entities of the cell interact with one another suggests that, nevertheless, integration of data from different techniques could drive a more comprehensive understanding of the data emanating from different techniques. Here, we provide an overview of how such data integration is being used to aid the understanding of metabolic pathway structure and regulation. We choose to focus on the pairwise integration of large-scale metabolite data with that of the transcriptomic, proteomics, whole-genome sequence, growth- and yield-associated phenotypes, and archival functional genomic data sets. In doing so, we attempt to provide an update on approaches that integrate data obtained at different levels to reach a better understanding of either single gene function or metabolic pathway structure and regulation within the context of a broader biological process.

The diversity of metabolites in the plant kingdom is staggering: a commonly quoted estimate is that plants produce somewhere in the order of 200,000 unique chemical structures (Dixon and Strack, 2003; Yonekura-Sakakibara and Saito, 2009; Tohge et al., 2014). Of these, only a relatively small subset will be abundant in any given tissue or any one species (Fernie, 2007); however, certain species have evolved a particularly rich metabolic diversity, presumably in response to environmental features of their habitat (for examples, see Futuyma and Agrawal, 2009; Moore et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015). Given these facts, it is unsurprising that our current understanding of the metabolic structure of a large number of pathways remains fragmentary; not to mention our current views of regulatory mechanisms underlying metabolite accumulation, which cover, at best, a very limited fraction of the metabolic network. This statement is especially true for the highly specialized pathways of secondary metabolism, although a number of gaps still remain to be filled also concerning important sectors of plant primary metabolism. As detailed in other Update articles within this issue, the adoption of various broad-scale profiling technologies to assess the gene, transcript, protein, and small molecule complement of the cell has started to mine this metabolic complexity. Additionally, the same approaches have also started to shed light on the evolution of gene and metabolite regulatory networks across the plant kingdom. In addition to large-scale profiling approaches, classical reductionist biochemistry and reverse genetic approaches retain, in any case, great utility in enhancing our understanding of enzyme mechanisms (and their regulation) and about the in vivo functions of enzymes, respectively. To give just a couple of recent examples from organic acid metabolism, a detailed study of the effect of phosphorylation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase reveals an important anaplerotic control point in developing castor bean (Ricinus communis) endosperm (Hill et al., 2014), while the enzyme pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase was recently demonstrated to represent a second gateway for organic acids into the gluconeogenic pathway in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Eastmond et al., 2015). We aim to provide examples from both primary and secondary metabolism and to illustrate the power of such approaches both in (1) gene functional annotation and (2) enhancing our understanding of the systems-level response to cellular circumstances. We will additionally discuss recent studies combining genome sequence data with metabolomics in order to highlight the utility of such approaches in metabolic quantitative loci analyses. Finally, we will detail insight that can be obtained from fusing archived data that can be downloaded from databases with experimental data generated de novo. Given that, as documented previously (Fernie and Stitt, 2012), a number of complicating factors still exist when attempting such analyses, we will discuss these on an approach-by-approach basis.

INTEGRATING METABOLITE AND TRANSCRIPTOME DATA

The earliest integrative approaches with relevance to plant metabolism featured the combination of data from transcript and metabolite profiling (Urbanczyk-Wochniak et al., 2003; Achnine et al., 2005; Tohge et al., 2005). Such studies were initially restricted to model species for which ESTs or oligonucleotides were available; early transcriptomics approaches relied in fact on differential hybridization of complementary DNA samples to known sequences immobilized on solid supports. The advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, however, has removed this barrier, and far more exotic species are beginning to be studied using this approach (Góngora-Castillo et al., 2012; Gechev et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015). Two basic questions are commonly addressed by combining transcript and metabolite data. The first concerns whether a gene functions within a given metabolic pathway. When a better characterization of the pathway is achieved, it becomes fundamental to investigate also the extent of transcriptional control (except in some cases, for example, regulation by posttranscriptional modifications of the enzyme and positive/negative feedback regulation by substrates/products) under various physiological conditions and how it is distributed across the various enzymatic steps.

Initial observations about the role of differential gene expression in tuning the synthesis of metabolites date back to the 1990s. Some specific pathways, such as hormone, glucosinolate, and flavonoid biosynthesis, were the initial focus of these investigations. For example, differential mechanisms of gene expression helped clarify in Arabidopsis the involvement of two different nitrilase genes in regulating the synthesis of auxin (Bartling et al., 1994). Similarly, the contributions of gene duplication and inducible gene expression (differential activation of subsets of biosynthetic genes) were shown to impact the amount and the composition of glucosinolates (Kliebenstein et al., 2001). An additional early evidence of the role of specific transcript accumulation on a metabolic phenotype came from the elucidation of the role that different regulation mechanisms affecting Trp synthase α and β had on the amount of 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one, a natural pesticide synthesized in maize (Zea mays) leaves (Melanson et al., 1997). Another example of the coordination between transcripts and metabolite accumulation came from the analysis of maize anthers, where a strong correlation was found between the expression of a structural gene (flavanone 3-hydroxylase) and the appearance of specific flavonols (mainly quercetin and kaempferol; Deboo et al., 1995). These same approaches have also been used to select a number of candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of capsaicinoids, a group of vanillylamides conferring pungency to hot peppers (Capsicum spp.). In this case, the comparison between sweet and hot pepper varieties facilitated the identification of some placenta-specific, differentially expressed genes that were directly correlated with the accumulation of capsaicinoids (Curry et al., 1999). The examples cited above laid the foundation for large-scale studies using the parallel analysis of transcripts and metabolites. One of the first examples of this approach focused on the identification of transcripts strongly correlated with the abundance of given metabolites across tuber development, irrespective of whether the transcript was associated with the metabolic pathway under question or not (Urbanczyk-Wochniak et al., 2003).

This approach was indeed able to identify some transcripts that exhibited very high correlation with the expression of certain genes and, as such, proved effective in identifying a number of candidate genes for biofortification. By corollary, the same approach can be, and indeed has been, used to elucidate the variation in gene-to-metabolite networks following short- and long-term nutritional stresses in Arabidopsis (Hirai et al., 2004) or to identify metabolic regulators of gene expression (Hirai et al., 2007). Cryptoxanthin, for example, was identified as highly correlating with a broad number of genes across diverse environmental conditions in Arabidopsis (Hannah et al., 2010), and the organic acid malate was putatively identified (Carrari et al., 2006) and subsequently confirmed (Centeno et al., 2011) to be important in mediating the ripening process in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Such current studies are all examples of the guilt-by-association approach, which in essence postulates biological entities as being functionally related if they exhibit strong correlation or coresponse across a wide range of cellular circumstances. The power of this approach is that, given that it does not rely on a priori pathway knowledge, it can have great utility in identifying novel metabolic integration and/or novel regulatory mechanisms (Hirai et al., 2007; Tohge et al., 2007; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008; Tohge and Fernie, 2010). However, a drawback of the approach is that, in the absence of subsequent rounds of experimentation, it is difficult to gain any insight into the mechanistic links underlying the observed behavior, given that correlation between biological entities does not always imply causation or the existence of functional links (Sweetlove and Fernie, 2005; Sweetlove et al., 2008; Stitt, 2013). In this regard, it becomes imperative to validate the outputs of coexpression analyses with follow-up approaches in order to prove the existence of putative functional links. Arguably, the greatest advances made to date following approaches to integrate transcript and metabolite data have been achieved in gene annotation and the structural elucidation of plant intermediary and secondary metabolism.

Two early studies of particular note are those from the Saito and Dixon laboratories investigating Arabidopsis anthocyanin and Medicago truncatula triterpene metabolism, respectively (Achnine et al., 2005; Tohge et al., 2005). In the case of the anthocyanin pathway, prior to the study of Tohge et al. (2005), no late biosynthetic genes involved in anthocyanin decoration steps had been identified in Arabidopsis, although all early biosynthetic genes have been characterized by visible phenotype screening. A combination of transcript and metabolite profiling on a Production of Anthocyanin Pigment1 activation-tagged line alongside validatory experiments involving both heterologously expressed enzymes and knockout mutants resulted in the identification of five genes and the identification of up to 11 anthocyanins. Such confirmatory experiments are essential in order to unequivocally assign gene function. The combination of reverse genetic strategies with the characterization of enzyme activity when the gene is expressed in a heterologous system remains the gold standard for the molecular identification of novel enzyme-catalyzed reactions (Tohge et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2007; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2012). Subsequent follow-up studies have identified some six genes associated with flavonol metabolism, and some 24 compounds (among 35 compounds found) of this class have now been identified in Arabidopsis (Tohge et al., 2007; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2007, 2008, 2014; Nakabayashi et al., 2009; Tohge and Fernie, 2010; Saito et al., 2013; Fig. 1). While the expansion of the characterized triterpenoid metabolism in M. truncatula is not quite so impressive, the study of Achnine et al. (2005) allowed the functional annotation of 30 different saponins, and currently, over 70 metabolites of this compound class have been identified in M. truncatula (Pollier et al., 2011; Gholami et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2015). The utility of this approach is at its greatest for the relatively unchartered pathways of specialized metabolism; however, it is worth noting that slight variations on this strategy independently identified the gene encoding plant Thr aldolase (Fernie et al., 2004; Jander et al., 2004) in Arabidopsis and 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one glucoside methyltransferase in maize (Meihls et al., 2013). A decade later, the number of species and pathways for which this approach has been adopted has expanded massively to include several crops and medicinal plants. Strategies combining transcript and metabolite profiling have proved effective in elucidating the structure of several metabolic pathways involved in the synthesis of primary metabolites, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids (Osorio et al., 2011, 2012; Shelton et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2015).

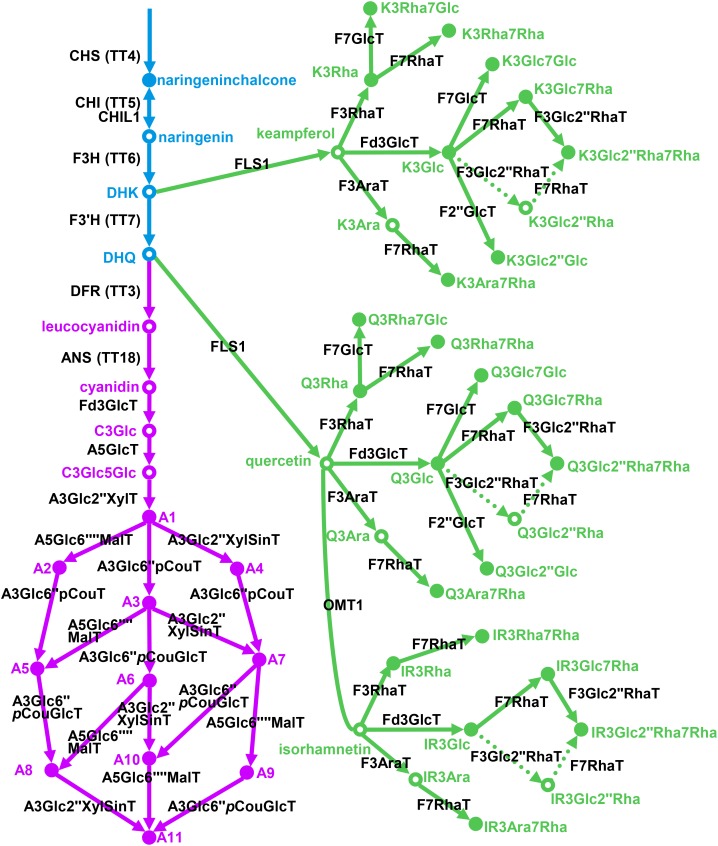

Figure 1.

Current model of flavonol/anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Colors are as follows: blue, early biosynthetic genes; green, flavonol-specific biosynthetic genes; and purple, anthocyanin-specific biosynthetic genes. CHS, Chalcone synthase, At5g13930; CHI, chalcone isomerase, At3g55120; CHIL1, At5g05270; F3H, flavanone-3-hydroxylase, At3g51240; F3′H, flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase, At5g07990; DFR, dihydroflavonol reductase, At5g42800; ANS, anthocyanidin synthase, At4g22880; F3GlcT, flavonoid-3-O-glucosyltransferase, UGT78D2, At5g17050; A5GlcT, anthocyanin-5-O-glucosyltransferase, UGT75C1, At4g14090; A3Glc2″XylT, anthocyanin-3-O-glucoside-2″-O-xylosyltransferase, UGT79B1, At5g54060; A5Glc6″″MalT, anthocyanin-5-O-glucoside-6″″-O-malonyltransferase, At3g29590; A3Glc6″pCouT, anthocyanin-3-O-glucoside-6″-O-p-coumaroyltransferase, At1g03940, At1g03495; A3Glc2″XylSinT, anthocyanin-3-O-(2″-O-xylosyl)-glucoside-6″′-O-sinapoyltransferase, At2g23000; A3Glc6″pCouT, anthocyanin-3-O-(6″-O-coumaroylglucoside-O-glucosyltransferase, At4g27830; FLS1, flavonol synthase, At5g08640; F3RhaT, flavonol-3-O-rhamnosyltransferase, UGT78D1, At1g30530; F3AraT, flavonol-3-O-arabinosyltransferase, UGT78D3, At5g17030; F7RhaT, flavonol 7-O-rhamnosyltransferase, UGT89C1, At1g06000; F7GlcT, flavonol 7-O-glucosyltransferase, UGT73C6, At2g36790; OMT1, O-methyltransferase, At5g54160.

On a broader level, the combination of transcript and metabolite profiling has commonly been used for multilayered descriptions of plant responses, particularly those to abiotic stress (Gibon et al., 2006; Maruyama-Nakashita et al., 2006; Kusano et al., 2011; Gechev et al., 2013; Bielecka et al., 2014; Nakabayashi et al., 2014). In this vein, a number of studies have been carried out that assess the combined transcript and metabolite responses to water stress, temperature stress, light stress, and limitations of nutrient supply (Urano et al., 2009; Caldana et al., 2011; Kusano et al., 2011; Nakabayashi et al., 2014). Such studies, while by nature descriptive, can afford insight into global metabolic variations under certain conditions as well as identify which pathways are under tight and which are under loose transcriptional control. Given the highly interconnected nature and nonlinearity of metabolic pathways in the global network structure, and even in the absence of flux profiling data, the integration of transcriptomics with wide metabolic profiling can, in any case, narrow down which metabolic steps could be active under specific conditions. Occasionally, however, they can also provide more mechanistic information. One prominent example of this is the detailed analysis of several transgenic Arabidopsis lines with altered flavonoid levels via transcriptomic and metabolomics analyses, including hormone analysis, which revealed that the overaccumulation of flavonoids exhibiting strong oxidative capacity in vitro also confers oxidative stress and drought tolerance (Nakabayashi et al., 2014; Nakabayashi and Saito, 2015). In addition, a range of developmental processes have been followed at high resolution by a combination of transcript and metabolite profiles. Such studies are dominated by studies of fruit ripening (Zamboni et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2015; Vallarino et al., 2015) and leaf development (Pick et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014); however, they are not limited to these processes, with studies also covering the development of various organs, lignin deposition, and the establishment of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis (Vanholme et al., 2013; Laparre et al., 2014; Nakamura et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). In this regard, these approaches prove informative in clarifying the relative importance of seemingly redundant pathways of biosynthesis and the degradation of specific metabolites or may also help to define the role of those primary metabolites (e.g. γ-aminobutyrate) for which a signaling role was hypothesized (Batushansky et al., 2014). For example, ascorbate biosynthesis, which is one of the well-studied metabolisms in several higher plants, especially in Arabidopsis (Wheeler et al., 1998; Gatzek et al., 2002; Laing et al., 2004; Conklin et al., 2006; Dowdle et al., 2007), has been revealed as the dominant route of ascorbate biosynthesis during ripening in tomato (Carrari et al., 2006). Another example could be found in the elucidation of the arogenate pathway as an alternative route for Phe biosynthesis (Dal Cin et al., 2011). A similar approach in Arabidopsis, based on feeding studies and coexpression analysis, allowed an alternative pathway to be proposed for Lys degradation in dark-induced senescent leaves (Araújo et al., 2010).

However, despite the fact that these examples illustrate that combined transcriptome/metabolome studies provide increases in our understanding of the regulation of metabolic networks, we contend that they remain at their most powerful in gene functional annotation and in the elucidation of species- and/or tissue-specific metabolic pathway structures.

INTEGRATING METABOLITE AND PROTEOME/ENZYME ACTIVITY DATA

Less commonly used to date than combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses are combined proteome and metabolome analyses. They are additionally largely used in a manner analogous to the more descriptive studies reviewed above. That said, considerable insight into metabolic network structure as well as into general aspects of metabolic regulation have been gained in this manner. Here, we will describe eight studies that illustrate how the integration of proteomic and metabolomic data sets has been used to inform our understanding of systems regulation. In the first of these examples, metabolite data were studied in parallel to enzyme data (and transcriptomics data) across varying diurnal cycles in wild-type and a starchless mutant of Arabidopsis, revealing that rapid changes in transcripts are integrated over time to generate essentially stable changes in many sectors of metabolism (Gibon et al., 2006). The same group went on to apply this approach to tomato fruit development and natural variance in Arabidopsis. In tomato, enzyme profiles were sufficiently characteristic to allow stages of development and cultivars and the wild species to be distinguished, but comparison of enzyme activity and metabolites revealed remarkably little connectivity between the developmental changes of enzyme and metabolite levels, suggesting the operation of posttranslational modification mechanisms (Steinhauser et al., 2010). In Arabidopsis, they documented highly coordinated changes between enzyme activities, particularly within those of the Calvin-Benson cycle, as well as significant correlations in specific metabolite pairs and between starch and growth. On the other hand, few correlations, and thus low overall connectivity, were observed between enzyme activities and metabolite levels (Sulpice et al., 2010), but strong links were seen between starch levels and growth, which we describe below. In an alternative approach, proteomic and metabolic data were used merely to extend the range of molecular entities in order to demonstrate that fascicular and extrafascicular phloem are isolated from one another and divergent in function (Zhang et al., 2010). A similar approach was taken to identify root as the major organ involved in alkaloid biosynthesis in Macleaya spp. (Zeng et al., 2013). Three further studies of note are more similar to that of Gibon et al. (2006) in that they use a combination of proteomics and metabolomics as a means to define the complex response of the cell to varying circumstances, be they iron nutrition in Arabidopsis (Sudre et al., 2013), the drought response in maize xylem (Alvarez et al., 2008), or heat stress acclimation in the model alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Hemme et al., 2014). The fact that many of these studies were published in the last 2 years reflects the growing uptake of such strategies. That said, in our opinion, it remains an underexploited research approach to date.

INTEGRATING METABOLITE AND GENOME DATA

Given that the advent of metabolomics more or less paralleled the release of the first plant genome, the integration of metabolomics and whole-genome sequence data is perhaps unsurprising. The true potential of this approach has been realized only within the last few years; we will not describe it again in detail, given that it is discussed in a previous correspondence in Plant Physiology (Fernie and Stitt, 2012). Suffice it to say, there are considerable complexities in such combinations; tellingly, early studies aimed at computational prediction of the size of the Escherichia coli metabolome estimated a complement of approximately 750 metabolites, while subsequent experimental approaches have revealed many metabolites that were not computed from the genome (van der Werf et al., 2007). Several potential reasons could be put forward to explain this discrepancy (for review, see Fernie and Stitt, 2012; Tohge et al., 2014); we contend here that an additional reason to explain this (partial) lack of concordance in the integrative approaches involving metabolism could lie within the incomplete annotation of most genomes, including those of model organisms. However, we believe the most likely reason to be the lack of linear relationship between genes, their protein products, and metabolites and, secondly, the fact that most genomes, even those of model organisms, remain incompletely annotated. Despite this serious drawback, we hope to illustrate in this section that the integration of metabolomics and genomic data can be incredibly powerful in understanding natural variation in metabolism and its regulation.

Whole-genome sequences are available for more than 100 plant species (including microalgae; Tohge et al., 2014); this massive acceleration afforded by next-generation technologies cannot currently be matched by metabolomics, especially if high-quality species-optimized approaches are adopted (Fukushima et al., 2014). The KNApSAcK database, which is one of the largest curated compendia of phytochemicals, contains over 700 compounds for early sequenced plants like Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa) but no entries for recently sequenced species such as goatgrass (Aegilops tauschii) and wild tobacco (Nicotiana tomentosiformis). In this section, we will describe insight gained from combining metabolomic data with genome sequences in three different case studies: (1) a simple comparison of a reference genome with metabolomics data; (2) a comparison of natural allelic and metabolic variance; and (3) integrating genome sequence data into quantitative genetics approaches. The first of these has been covered in considerable detail recently (Fukushima et al., 2014; Tohge et al., 2014), so we will only briefly describe it here. The starting point is to perform genome-wide ortholog searches using functionally annotated genes; best practice is to use cross-species cluster-based BLAST searches such as those housed in the PLAZA database (Proost et al., 2009) or, in the case of photosynthetic microbes, pico-PLAZA (Vandepoele et al., 2013). Illustrations of how such analyses have been performed for central, shikimate, phenylpropanoid, terpenoid, alkaloid, and glucosinolate metabolism have been presented (Hofberger et al., 2013; Tohge et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014; Cavalcanti et al., 2014; Boutanaev et al., 2015). Thereafter, comparison of these gene inventories with metabolite profiles of the species under evaluation allows the construction of putative metabolic pathway structures that can be further tested via reverse genetics or heterologous expression, as described in “Integrating Metabolite and Transcript Data” above. Important insights into pathway evolution can be gained from such approaches, as illustrated by the recent cross-kingdom comparison of ascorbate biosynthesis (Wheeler et al., 2015).

The second case study, that of evaluating allelic and metabolic variance across natural diversity, is similar in scope yet far more targeted than genome-wide association studies, which we describe below. The majority of recent examples of its utility come from the analysis of wild species tomato; however, it is important to note that the approach itself is essentially just a modification of that adopted over decades in the cloning of natural color mutants (Fernie and Klee, 2011). In the last few years, understanding of primary as well as secondary and cuticular cell wall metabolism has been enhanced considerably via this approach (Schauer et al., 2005; Matas et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012, 2014; Koenig et al., 2013), albeit the greatest insight into the latter was ultimately elucidated via the use of an introgression line population, as described below. In essence, this approach starts with the identification of metabolic variance within a population of ecotypes, cultivars, or similarly related species and attempts to link this with allelic diversity or gene duplication, as has been achieved for acyl-sugar metabolites (Schilmiller et al., 2015), terpenes (Matsuba et al., 2013), and isoprenoids (Kang et al., 2014), or even with the presence or absence of genes, as described recently for methylated flavonoids of glandular trichomes (Kim et al., 2014). The preceding list documents the success of this approach; until recently, however, it was constrained by the limits of our a priori knowledge, which is needed in order to select the candidate genes in which we search for allelic variance. The development of RNA sequencing technologies means that we are no longer limited by the amount of sequence data; a potential hurdle to these integrative approaches, however, can still be present when comparing highly genetically divergent individuals, since the number of genetic polymorphisms is too great to evaluate one by one. For this reason, the quantitative trait loci approach is a powerful alternative method of associating phenotypes to their underlying genetic variance. The use of such approaches in plant metabolism has been the subject of several recent comprehensive reviews (Kliebenstein, 2009; Scossa et al., 2015); however, we will provide a couple of examples of their utility for advancing the understanding of metabolite accumulation and metabolic regulation.

The fruit of tomato, as the model species for ripening of fleshy fruits, has been the subject of combined large-scale genomic, physiological, and metabolic investigations, often making use of specific biparental populations or large sets of unrelated individuals, in an attempt to understand the causal variants of the metabolic variations (Schauer et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2014; Sauvage et al., 2014). In particular, the use of a population of introgression lines, obtained from the cross between tomato and Solanum pennellii (a wild tomato species), has greatly aided the identification of quantitative trait loci for a large number of physiological and metabolic traits. Profiling data of primary and secondary metabolites in this population were collected over several years (along with some classical yield-related traits), revealing more than 1,500 metabolic quantitative trait loci affecting the levels of several sugars, amino acids, organic acids, vitamins, phenylpropanoids, and glycoalkaloids. The availability of the sequences of both parental genomes (Bolger et al., 2014) narrowed down the origin of the metabolic variation to specific genetic polymorphisms in some selected metabolic quantitative trait loci (Quadrana et al., 2014; Alseekh et al., 2015). The integration between genotypic and metabolic variance can be, and has actually been applied, also on large collections of unrelated individuals (metabolite-based genome-wide association studies): as in the case of biparental populations, also with this strategy, several cases of polymorphological variants of genomic sequences have been identified and related to metabolic variation. These two approaches, based either on biparental populations or on large collections of natural accessions, have been used in Arabidopsis and crop species (maize, rice, wheat [Triticum aestivum], and fruit trees; Gong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2014; Matsuda et al., 2015; for review, see Luo, 2015). The boon that new sequences will provide, especially from wild relatives or locally adapted varieties, will be represented by the possibility to dissect the genetic basis of metabolite variation, with a view to introgress beneficial traits in crop improvement.

INTEGRATING METABOLITE AND PHYSIOLOGICAL DATA

While the above examples concentrate on the integration of various types of profiling data with one another in order to advance our understanding of metabolic pathway structure and/or metabolic regulation, relatively few studies have attempted to correlate metabolite content with physiological data, including growth and yield (for review, see Stitt et al., 2010; Carreno-Quintero et al., 2013). One of the earliest studies to do so was the above-described metabolic quantitative trait loci analysis of the S. pennellii introgression lines, in which yield-associated plant traits were measured alongside primary metabolite content of the fruit (Schauer et al., 2006). In this study, network analysis based on cartographic modeling algorithms developed by Guimerà and Nunes Amaral (2005) identified that yield-associated traits were positively correlated to a range of previously defined signal metabolites, compounds that have signaling as well as metabolic functions, including Suc, hexose, and inositol phosphates, Pro, and γ-aminobutyrate. In addition, this study indicated that the harvest index (i.e. the ratio of harvestable product to total biomass) negatively correlated with the content of the vast majority of amino acids. This relationship was confirmed in an independent population and following experiments that artificially altered the fruit load per truss (Do et al., 2010). However, as would perhaps be anticipated, subsequent evaluation of the relationship between growth and secondary metabolite content revealed far less correlation (Alseekh et al., 2015). Using essentially the same approach in an Arabidopsis recombinant inbred line population, Meyer et al. (2007) found that, although no single metabolite exhibited a very high correlation with biomass, canonical correlation analysis in which the data of a linear combination of metabolites allowed the improvement of this correlation by a factor of 10, thus defined a metabolic signature of growth. Intriguingly, the hexose phosphates Glc-6-P and Fru-6-P as well as Suc were among the 20 top metabolites contributing to this signature. When similar approaches were applied to maize, strong genome-wide association links were found between coumaric and caffeic acids and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, while these precursors also significantly correlated with lignin content plant height and dry matter yield, presenting another example of the narrowing of the genotype-phenotype gap of complex agronomic traits (Riedelsheimer et al., 2012). The same group revealed that models based on data obtained for 130 metabolites gave highly accurate predictions of agronomic traits and suggested that combined metabolite, genomic, and agronomic phenotyping represents an important screening tool for the identification of parental lines for the creation of superior hybrid crops (Riedelsheimer et al., 2012).

Returning to Arabidopsis, evaluation of the variation of growth, metabolite levels, and enzyme activities was also carried out across 94 accessions, revealing that biomass correlated negatively with many metabolites, including starch and protein and to a much lesser extent Suc (Sulpice et al., 2009). However, further experiments in which 97 accessions grown in near-optimal carbon and nitrogen supply, restricted carbon supply, and restricted nitrogen supply and analyzed for biomass and 54 metabolic traits revealed that robust prediction of phenotypic traits (biomass, starch, and protein) is most effective (and reliable) when metabolite data (upon which predictions are based) are collected from the same growth environments (Meyer et al., 2007; Sulpice et al., 2009; Korn et al., 2010; Steinfath et al., 2010). Clearly, attempting to predict biomass, for example, from metabolic profiles collected in a different growth environment generally yields fewer (and weaker) correlations (Sulpice et al., 2013). Therefore, the prediction of biomass across a range of conditions would better require condition-specific measurement of metabolic traits to take account of environment-dependent changes of the underlying networks (Sulpice et al., 2013). Data from this study were subsequently analyzed with respect to the tradeoffs between metabolism and growth, specifically comparing increasing size with increasing protein concentration, demonstrating that accessions with high metabolic efficiency lie closer to the Pareto performance frontier (the optimal solution for the two contending tasks) and hence exhibit increased metabolic plasticity (Kleessen et al., 2014). A related study addressing an ecological tradeoff between secondary metabolism and fitness relates to the accumulation of capsaicinoids in the placenta of pepper fruits (Capsicum spp.). Capsaicinoids constitute a class of vanillylamides derived from Phe; they accumulate in ripening pepper fruit and are responsible for the pungency sensation occurring upon ingestion. In natural environments, the accumulation of capsaicinoids in populations of Capsicum chacoense (a wild pepper species) is inversely correlated with seed set; these metabolites, however, have a defensive role in highly humid environments, where their accumulation deters the attack of phytopathogenic fungi. Across a geographical gradient of decreasing rainfall (with a gradual decreasing pressure of the pathogens, which thrive only in humid environments), the accumulation of capsaicinoids also decreases in Capsicum spp. populations, while seed set, on the other hand, increases. This study is an example of the combination of targeted metabolic approaches with population ecology in dissecting the basis of natural polymorphic traits (Haak et al., 2012). Further studies that address the concept of metabolism and growth tradeoffs have used reciprocal crosses to assess the contribution of the organellar genome to the processes and came to the conclusion that there is far greater diversity in defense chemistry than primary metabolism (Joseph et al., 2013, 2015). The interrogation of such tradeoffs is only possible via the integrated approach described here and appears to be very powerful; as such, we would expect considerable advances in our understanding of this phenomenon to be gained following its application. Not just the last three studies but all of the above studies have been published within the last 6 years, reflecting the fact that such analyses are in their infancy. Given the recognized complexity of the metabolism-to-growth interactions, a comprehensive understanding of the intricate networks that coordinate this interface is likely some time off. That said, as the above examples illustrate, the integration of growth data into metabolite profiling data as well as that of simpler physiological processes such as photosynthetic or respiratory rates (Florez-Sarasa et al., 2012) has already presented a number of key findings.

POSTGENOMIC INTEGRATION OF DATABASE-HOUSED RESEARCH WITH NOVEL EXPERIMENTS

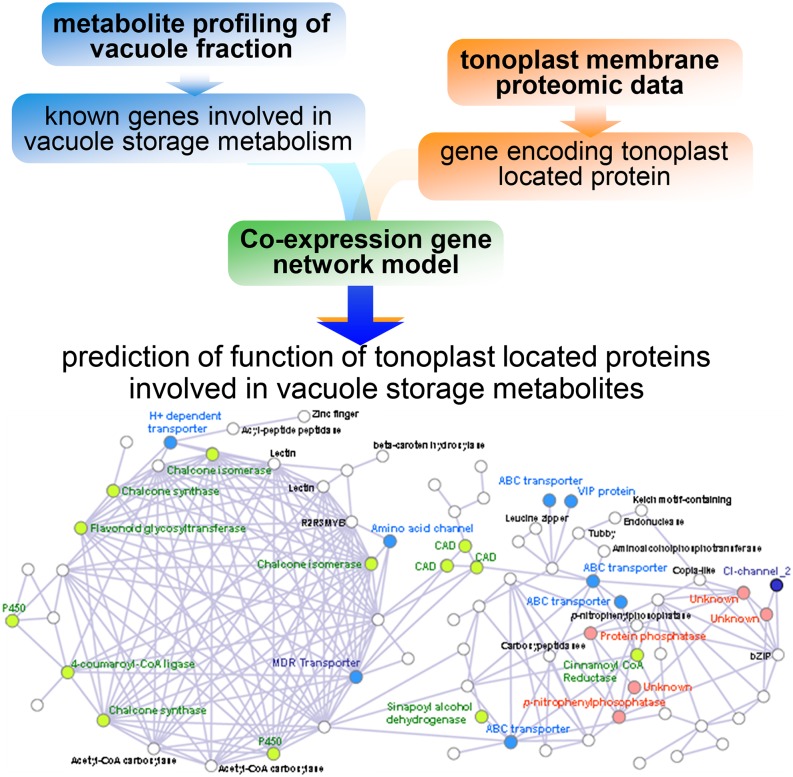

The examples described above rely on the integration of data obtained in parallel using different experimental approaches. While such approaches are ideal for addressing a number of questions, particularly those concerning the temporal aspects underlying dynamic responses to a systems perturbation, the integration of novel experimental data with different types of archived data can also prove highly informative, providing an appropriate amount of caution is used in interpreting the results. Here, we will provide several examples illustrative of such approaches, which largely fit into two major types of approaches: (1) those using correlative approaches and (2) those using genome-scale stoichiometric models. The first study we will describe fits into the former category, being an attempt to define the storage metabolome of the vacuole (Tohge et al., 2011; Fig. 2). In this research, a combination of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and Fourier transform mass spectrometry was used to detect and quantify some 59 primary metabolites and 200 secondary metabolites (defined on the basis of strong chemical formulae predictions) in either silicon oil-purified barley (Hordeum vulgare) vacuoles or the protoplasts from which these were derived. Of the 259 putative metabolites, 12 were exclusively detected in the vacuole, 34 were exclusively in the protoplast, and 213 were common to both samples. At the quantitative level, the difference between vacuole and protoplast was yet more striking, with secondary metabolites being differentially abundant between the two sample types. As a next step to predict the underlying cytosolic-vacuolar transporters, tonoplast proteins predicted to have a transport function were evaluated within the context of the metabolic profiling data. Specifically, 88 proteins reported to be tonoplast proteins in barley (Endler et al., 2006) were evaluated after conversion to Affymetrix probe identifiers and coexpression analysis of the resultant 128 probe sets was carried out using PlaNet for barley (Mutwil et al., 2011; http://aranet.mpimp-golm.mpg.de). Coexpressed networks of these probes separated into 13 subgroups, with the most dense cluster being highly correlated with aromatic amino acid-related genes and the second most dense cluster including several vacuolar ATP synthase proteins and tricarboxylic acid cycle-related genes. In addition, clear associations were found between the expression of transport proteins and that of pathways of flavonoid and mugineic acid synthesis as well as storage protein functions (Tohge et al., 2011). This study was thus able to putatively assign function to previously described transporter proteins as well as to highlight the dynamic nature of the storage metabolome. The coexpression approach has also been combined with metabolic profiling in the annotation of plasma membrane lignin and plastidial glycolate/glycerate and bile acid transporters (Gigolashvili et al., 2009; Sawada et al., 2009; Alejandro et al., 2012) as well as a multitude of cell wall-associated proteins (Persson et al., 2005). Moreover, this approach has also been used to identify process, as opposed to pathway-specific, proteins, identifying proteins involved in dark-induced senescence (Araújo et al., 2011) and in the response to UV-B irradiance (Kusano et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of an integrative approach using metabolite profiling of storage metabolite and membrane proteomic data. Example of network: barley vacuole network from Tohge et al. (2011).

The other type of examples we would like to discuss are based on the integration of transcriptomic and metabolomics level genome-scale models (Töpfer et al., 2014). In the first of these studies, microarray data from Arabidopsis exposed to eight different light and temperature conditions (data published in Caldana et al., 2011) were integrated into a genome-scale model (Mintz-Oron et al., 2012). Before discussing the outcome of this integration, we first digress to provide a brief description of how genome-scale models are generated. Essentially, a genome-scale model corresponds metabolic genes with metabolic pathways in a manner whereby a stoichiometrically balanced metabolic network is generated, which corresponds to all gene functions annotated for that organism. Such models were originally published for microbes at the turn of the century (Edwards and Palsson, 2000), with many models for plants species being subsequently generated, including the model species Arabidopsis as well as crop species such as rice and maize (for review, see Simons et al., 2014). Returning to the superimposition of experimental data on the model, the addition of transcriptomic data was able to predict flux capacities and statistically assess whether these vary under the experimental conditions tested. Moreover, this study introduced the concepts of metabolic sustainers and modulators, with the former being metabolic functions that are differentially up-regulated with respect to the null model whereas the latter are differentially down-regulated in order to control a certain flux and, therefore, modulate affected processes (Töpfer et al., 2013). In a follow-up study, predictions made from the integration of transcriptomics were complemented with metabolomics data from the same experiment. In doing so, the authors were able to bridge flux-centric and metabolomics-centric approaches and, in so doing, demonstrate that, under certain conditions, metabolites serving as pathway substrates in pathways defined as either modulators or sustainers display lower temporal variation with respect to all other metabolites (Töpfer et al., 2013). These findings are thus in concordance with theories of network rigidity and pathway robustness (Stephanopoulos and Vallino, 1991; Rontein et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2008). Furthermore, considerable evidence suggests that the levels of specific metabolites, such as Ala, pyruvate, 2-oxoglutarate, Gln, and spermidine, are exceptionally stable across a massive range of cellular circumstances (Geigenberger, 2003; Stitt and Fernie, 2003). They also are in keeping with observations that the levels of metabolites such as Ser coordinately control the levels of expression of genes encoding multiple steps of the pathways to which they, themselves, belong (Timm et al., 2013). The high stability of these metabolites is in keeping with their requirement across a range of different stresses. It also highlights the fact that the robust metabolites may well be the most biologically relevant for metabolic regulation; this is an important point, since it is at odds with the manner in which the majority of the metabolomics community assesses their data. This observation additionally highlights the potential difficulties and challenges in interpreting data from a single level of the cellular hierarchy and thus provides further grounds for integrated models.

CURRENT AND FUTURE CHALLENGES IN DATA INTEGRATION

The above sections document that integrative approaches to further our understanding of metabolism have proven very successful over the last decade or so, particularly when linked with genetic and/or environmental experiments. To date, the approaches taken have been relatively straightforward and have generally not been performed at a high level of spatial resolution. Several methods currently exist to obtain data from all of the methods described here at the tissue, cellular, and even subcellular levels (Aharoni and Brandizzi, 2012); while still technically challenging, it seems conceivable that such methods could provide data required to better understand the cell specialization of metabolism. In addition, methods to gain accurate metabolic flux estimates following 13CO2 labeling have recently been established (Young et al., 2008; Szecowka et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014) but are not yet fully integrated with protein or transcript data. However, it is important to note that such experiments, albeit using [13C]Glc as a precursor, have already been carried out in in vitro-cultivated Brassica napus embryos, providing considerable insight into the systems-level regulation of this organ (Schwender et al., 2015). It additionally seems highly likely that future research will draw more heavily on archived genomics data than it has to date; thus, the continued availability and quality-control curation of such data sets are imperative if we are going to fully exploit their value.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society (to T.T. and A.R.F.) and an Alexander von Humboldt grant (to T.T.).

References

- Achnine L, Huhman DV, Farag MA, Sumner LW, Blount JW, Dixon RA (2005) Genomics-based selection and functional characterization of triterpene glycosyltransferases from the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 41: 875–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A, Brandizzi F (2012) High-resolution measurements in plant biology. Plant J 70: 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alejandro S, Lee Y, Tohge T, Sudre D, Osorio S, Park J, Bovet L, Lee Y, Geldner N, Fernie AR, et al. (2012) AtABCG29 is a monolignol transporter involved in lignin biosynthesis. Curr Biol 22: 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alseekh S, Tohge T, Wendenberg R, Scossa F, Omranian N, Li J, Kleessen S, Giavalisco P, Pleban T, Mueller-Roeber B, et al. (2015) Identification and mode of inheritance of quantitative trait loci for secondary metabolite abundance in tomato. Plant Cell 27: 485–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez S, Marsh EL, Schroeder SG, Schachtman DP (2008) Metabolomic and proteomic changes in the xylem sap of maize under drought. Plant Cell Environ 31: 325–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo WL, Ishizaki K, Nunes-Nesi A, Larson TR, Tohge T, Krahnert I, Witt S, Obata T, Schauer N, Graham IA, et al. (2010) Identification of the 2-hydroxyglutarate and isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenases as alternative electron donors linking lysine catabolism to the electron transport chain of Arabidopsis mitochondria. Plant Cell 22: 1549–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo WL, Ishizaki K, Nunes-Nesi A, Tohge T, Larson TR, Krahnert I, Balbo I, Witt S, Dörmann P, Graham IA, et al. (2011) Analysis of a range of catabolic mutants provides evidence that phytanoyl-coenzyme A does not act as a substrate of the electron-transfer flavoprotein/electron-transfer flavoprotein:ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex in Arabidopsis during dark-induced senescence. Plant Physiol 157: 55–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartling D, Seedorf M, Schmidt RC, Weiler EW (1994) Molecular characterization of two cloned nitrilases from Arabidopsis thaliana: key enzymes in biosynthesis of the plant hormone indole-3-acetic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 6021–6025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batushansky A, Kirma M, Grillich N, Toubiana D, Pham PA, Balbo I, Fromm H, Galili G, Fernie AR, Fait A (2014) Combined transcriptomics and metabolomics of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings exposed to exogenous GABA suggest its role in plants is predominantly metabolic. Mol Plant 7: 1065–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecka M, Watanabe M, Morcuende R, Scheible WR, Hawkesford MJ, Hesse H, Hoefgen R (2014) Transcriptome and metabolome analysis of plant sulfate starvation and resupply provides novel information on transcriptional regulation of metabolism associated with sulfur, nitrogen and phosphorus nutritional responses in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 5: 805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A, Scossa F, Bolger ME, Lanz C, Maumus F, Tohge T, Quesneville H, Alseekh S, Sørensen I, Lichtenstein G, et al. (2014) The genome of the stress-tolerant wild tomato species Solanum pennellii. Nat Genet 46: 1034–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutanaev AM, Moses T, Zi J, Nelson DR, Mugford ST, Peters RJ, Osbourn A (2015) Investigation of terpene diversification across multiple sequenced plant genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: E81–E88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C, Degenkolbe T, Cuadros-Inostroza A, Klie S, Sulpice R, Leisse A, Steinhauser D, Fernie AR, Willmitzer L, Hannah MA (2011) High-density kinetic analysis of the metabolomic and transcriptomic response of Arabidopsis to eight environmental conditions. Plant J 67: 869–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrari F, Baxter C, Usadel B, Urbanczyk-Wochniak E, Zanor MI, Nunes-Nesi A, Nikiforova V, Centero D, Ratzka A, Pauly M, et al. (2006) Integrated analysis of metabolite and transcript levels reveals the metabolic shifts that underlie tomato fruit development and highlight regulatory aspects of metabolic network behavior. Plant Physiol 142: 1380–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno-Quintero N, Bouwmeester HJ, Keurentjes JJB (2013) Genetic analysis of metabolome-phenotype interactions: from model to crop species. Trends Genet 29: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti JH, Esteves-Ferreira AA, Quinhones CG, Pereira-Lima IA, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Araújo WL (2014) Evolution and functional implications of the tricarboxylic acid cycle as revealed by phylogenetic analysis. Genome Biol Evol 6: 2830–2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centeno DC, Osorio S, Nunes-Nesi A, Bertolo ALF, Carneiro RT, Araújo WL, Steinhauser MC, Michalska J, Rohrmann J, Geigenberger P, et al. (2011) Malate plays a crucial role in starch metabolism, ripening, and soluble solid content of tomato fruit and affects postharvest softening. Plant Cell 23: 162–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin PL, Gatzek S, Wheeler GL, Dowdle J, Raymond MJ, Rolinski S, Isupov M, Littlechild JA, Smirnoff N (2006) Arabidopsis thaliana VTC4 encodes L-galactose-1-P phosphatase, a plant ascorbic acid biosynthetic enzyme. J Biol Chem 281: 15662–15670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry J, Aluru M, Mendoza M, Nevarez J, Melendrez M, O’Connell MA (1999) Transcripts for possible capsaicinoid biosynthetic genes are differentially accumulated in pungent and non-pungent Capsicum spp. Plant Sci 148: 47–57 [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin V, Tieman DM, Tohge T, McQuinn R, de Vos RCH, Osorio S, Schmelz EA, Taylor MG, Smits-Kroon MT, Schuurink RC, et al. (2011) Identification of genes in the phenylalanine metabolic pathway by ectopic expression of a MYB transcription factor in tomato fruit. Plant Cell 23: 2738–2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deboo GB, Albertsen MC, Taylor LP (1995) Flavanone 3-hydroxylase transcripts and flavonol accumulation are temporally coordinate in maize anthers. Plant J 7: 703–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Strack D (2003) Phytochemistry meets genome analysis, and beyond. Phytochemistry 62: 815–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do PT, Prudent M, Sulpice R, Causse M, Fernie AR (2010) The influence of fruit load on the tomato pericarp metabolome in a Solanum chmielewskii introgression line population. Plant Physiol 154: 1128–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle J, Ishikawa T, Gatzek S, Rolinski S, Smirnoff N (2007) Two genes in Arabidopsis thaliana encoding GDP-L-galactose phosphorylase are required for ascorbate biosynthesis and seedling viability. Plant J 52: 673–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ, Astley HM, Parsley K, Aubry S, Williams BP, Menard GN, Craddock CP, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Hibberd JM (2015) Arabidopsis uses two gluconeogenic gateways for organic acids to fuel seedling establishment. Nat Commun 6: 6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JS, Palsson BO (2000) The Escherichia coli MG1655 in silico metabolic genotype: its definition, characteristics, and capabilities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5528–5533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler A, Meyer S, Schelbert S, Schneider T, Weschke W, Peters SW, Keller F, Baginsky S, Martinoia E, Schmidt UG (2006) Identification of a vacuolar sucrose transporter in barley and Arabidopsis mesophyll cells by a tonoplast proteomic approach. Plant Physiol 141: 196–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie AR. (2007) The future of metabolic phytochemistry: larger numbers of metabolites, higher resolution, greater understanding. Phytochemistry 68: 2861–2880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie AR, Klee HJ (2011) The use of natural genetic diversity in the understanding of metabolic organization and regulation. Front Plant Sci 2: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie AR, Stitt M (2012) On the discordance of metabolomics with proteomics and transcriptomics: coping with increasing complexity in logic, chemistry, and network interactions. Plant Physiol 158: 1139–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie AR, Trethewey RN, Krotzky AJ, Willmitzer L (2004) Metabolite profiling: from diagnostics to systems biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 763–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Sarasa I, Araújo WL, Wallström SV, Rasmusson AG, Fernie AR, Ribas-Carbo M (2012) Light-responsive metabolite and transcript levels are maintained following a dark-adaptation period in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 195: 136–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima A, Kanaya S, Nishida K (2014) Integrated network analysis and effective tools in plant systems biology. Front Plant Sci 5: 598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futuyma DJ, Agrawal AA (2009) Macroevolution and the biological diversity of plants and herbivores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 18054–18061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzek S, Wheeler GL, Smirnoff N (2002) Antisense suppression of L-galactose dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana provides evidence for its role in ascorbate synthesis and reveals light modulated L-galactose synthesis. Plant J 30: 541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gechev TS, Benina M, Obata T, Tohge T, Sujeeth N, Minkov I, Hille J, Temanni MR, Marriott AS, Bergström E, et al. (2013) Molecular mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in the resurrection glacial relic Haberlea rhodopensis. Cell Mol Life Sci 70: 689–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigenberger P. (2003) Response of plant metabolism to too little oxygen. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami A, De Geyter N, Pollier J, Goormachtig S, Goossens A (2014) Natural product biosynthesis in Medicago species. Nat Prod Rep 31: 356–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibon Y, Usadel B, Blaesing OE, Kamlage B, Hoehne M, Trethewey R, Stitt M (2006) Integration of metabolite with transcript and enzyme activity profiling during diurnal cycles in Arabidopsis rosettes. Genome Biol 7: R76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigolashvili T, Yatusevich R, Rollwitz I, Humphry M, Gershenzon J, Flügge UI (2009) The plastidic bile acid transporter 5 is required for the biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 1813–1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Chen W, Gao Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Xu C, Yu S, Zhang Q, Luo J (2013) Genetic analysis of the metabolome exemplified using a rice population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20320–20325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Góngora-Castillo E, Childs KL, Fedewa G, Hamilton JP, Liscombe DK, Magallanes-Lundback M, Mandadi KK, Nims E, Runguphan W, Vaillancourt B, et al. (2012) Development of transcriptomic resources for interrogating the biosynthesis of monoterpene indole alkaloids in medicinal plant species. PLoS One 7: e52506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimerà R, Nunes Amaral LA (2005) Functional cartography of complex metabolic networks. Nature 433: 895–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak DC, McGinnis LA, Levey DJ, Tewksbury JJ (2012) Why are not all chilies hot? A trade-off limits pungency. Proc Biol Sci 279: 2012–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah MA, Caldana C, Steinhauser D, Balbo I, Fernie AR, Willmitzer L (2010) Combined transcript and metabolite profiling of Arabidopsis grown under widely variant growth conditions facilitates the identification of novel metabolite-mediated regulation of gene expression. Plant Physiol 152: 2120–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemme D, Veyel D, Mühlhaus T, Sommer F, Jüppner J, Unger AK, Sandmann M, Fehrle I, Schönfelder S, Steup M, et al. (2014) Systems-wide analysis of acclimation responses to long-term heat stress and recovery in the photosynthetic model organism Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell 26: 4270–4297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Ying S, Plaxton WC (2014) Phosphorylation of bacterial-type phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase by a Ca2+-dependent protein kinase suggests a link between Ca2+ signalling and anaplerotic pathway control in developing castor oil seeds. Biochem J 458: 109–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Sugiyama K, Sawada Y, Tohge T, Obayashi T, Suzuki A, Araki R, Sakurai N, Suzuki H, Aoki K, et al. (2007) Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcription factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6478–6483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Yano M, Goodenowe DB, Kanaya S, Kimura T, Awazuhara M, Arita M, Fujiwara T, Saito K (2004) Integration of transcriptomics and metabolomics for understanding of global responses to nutritional stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10205–10210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofberger JA, Lyons E, Edger PP, Pires JC, Schranz ME (2013) Whole genome and tandem duplicate retention facilitated glucosinolate pathway diversification in the mustard family. Genome Biol Evol 5: 2155–2173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G, Norris SR, Joshi V, Fraga M, Rugg A, Yu S, Li L, Last RL (2004) Application of a high-throughput HPLC-MS/MS assay to Arabidopsis mutant screening; evidence that threonine aldolase plays a role in seed nutritional quality. Plant J 39: 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph B, Corwin JA, Kliebenstein DJ (2015) Genetic variation in the nuclear and organellar genomes modulates stochastic variation in the metabolome, growth, and defense. PLoS Genet 11: e1004779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph B, Corwin JA, Züst T, Li B, Iravani M, Schaepman-Strub G, Turnbull LA, Kliebenstein DJ (2013) Hierarchical nuclear and cytoplasmic genetic architectures for plant growth and defense within Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1929–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Gonzales-Vigil E, Matsuba Y, Pichersky E, Barry CS (2014) Determination of residues responsible for substrate and product specificity of Solanum habrochaites short-chain cis-prenyltransferases. Plant Physiol 164: 80–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kang K, Gonzales-Vigil E, Shi F, Jones AD, Barry CS, Last RL (2012) Striking natural diversity in glandular trichome acylsugar composition is shaped by variation at the Acyltransferase2 locus in the wild tomato Solanum habrochaites. Plant Physiol 160: 1854–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Matsuba Y, Ning J, Schilmiller AL, Hammar D, Jones AD, Pichersky E, Last RL (2014) Analysis of natural and induced variation in tomato glandular trichome flavonoids identifies a gene not present in the reference genome. Plant Cell 26: 3272–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleessen S, Laitinen R, Fusari CM, Antonio C, Sulpice R, Fernie AR, Stitt M, Nikoloski Z (2014) Metabolic efficiency underpins performance trade-offs in growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun 5: 3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein D. (2009) Advancing genetic theory and application by metabolic quantitative trait loci analysis. Plant Cell 21: 1637–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Lambrix VM, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Mitchell-Olds T (2001) Gene duplication in the diversification of secondary metabolism: tandem 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases control glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13: 681–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig D, Jiménez-Gómez JM, Kimura S, Fulop D, Chitwood DH, Headland LR, Kumar R, Covington MF, Devisetty UK, Tat AV, et al. (2013) Comparative transcriptomics reveals patterns of selection in domesticated and wild tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E2655–E2662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn M, Gärtner T, Erban A, Kopka J, Selbig J, Hincha DK (2010) Predicting Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and heterosis in freezing tolerance from metabolite composition. Mol Plant 3: 224–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano M, Tohge T, Fukushima A, Kobayashi M, Hayashi N, Otsuki H, Kondou Y, Goto H, Kawashima M, Matsuda F, et al. (2011) Metabolomics reveals comprehensive reprogramming involving two independent metabolic responses of Arabidopsis to UV-B light. Plant J 67: 354–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing WA, Bulley S, Wright M, Cooney J, Jensen D, Barraclough D, MacRae E (2004) A highly specific L-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase on the path to ascorbate biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 16976–16981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laparre J, Malbreil M, Letisse F, Portais JC, Roux C, Bécard G, Puech-Pagès V (2014) Combining metabolomics and gene expression analysis reveals that propionyl- and butyryl-carnitines are involved in late stages of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Mol Plant 7: 554–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Baldwin IT, Gaquerel E (2015) Navigating natural variation in herbivory-induced secondary metabolism in coyote tobacco populations using MS/MS structural analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: E4147–E4155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Peng Z, Yang X, Wang W, Fu J, Wang J, Han Y, Chai Y, Guo T, Yang N, et al. (2013) Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. Nat Genet 45: 43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Wang C, Dong W, Jiang Q, Wang D, Li S, Chen M, Liu C, Sun C, Chen K (2015) Transcriptome and metabolome analyses of sugar and organic acid metabolism in ponkan (Citrus reticulata) fruit during fruit maturation. Gene 554: 64–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Zhu G, Zhang J, Xu X, Yu Q, Zheng Z, Zhang Z, Lun Y, Li S, Wang X, et al. (2014) Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat Genet 46: 1220–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. (2015) Metabolite-based genome-wide association studies in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 24: 31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Nishiyama Y, Fuell C, Taguchi G, Elliott K, Hill L, Tanaka Y, Kitayama M, Yamazaki M, Bailey P, et al. (2007) Convergent evolution in the BAHD family of acyl transferases: identification and characterization of anthocyanin acyl transferases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 50: 678–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Jazmin LJ, Young JD, Allen DK (2014) Isotopically nonstationary 13C flux analysis of changes in Arabidopsis thaliana leaf metabolism due to high light acclimation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 16967–16972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama-Nakashita A, Nakamura Y, Tohge T, Saito K, Takahashi H (2006) Arabidopsis SLIM1 is a central transcriptional regulator of plant sulfur response and metabolism. Plant Cell 18: 3235–3251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matas AJ, Yeats TH, Buda GJ, Zheng Y, Chatterjee S, Tohge T, Ponnala L, Adato A, Aharoni A, Stark R, et al. (2011) Tissue- and cell-type specific transcriptome profiling of expanding tomato fruit provides insights into metabolic and regulatory specialization and cuticle formation. Plant Cell 23: 3893–3910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuba Y, Nguyen TTH, Wiegert K, Falara V, Gonzales-Vigil E, Leong B, Schäfer P, Kudrna D, Wing RA, Bolger AM, et al. (2013) Evolution of a complex locus for terpene biosynthesis in Solanum. Plant Cell 25: 2022–2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda F, Nakabayashi R, Yang Z, Okazaki Y, Yonemaru J, Ebana K, Yano M, Saito K (2015) Metabolome-genome-wide association study dissects genetic architecture for generating natural variation in rice secondary metabolism. Plant J 81: 13–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meihls LN, Handrick V, Glauser G, Barbier H, Kaur H, Haribal MM, Lipka AE, Gershenzon J, Buckler ES, Erb M, et al. (2013) Natural variation in maize aphid resistance is associated with 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one glucoside methyltransferase activity. Plant Cell 25: 2341–2355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melanson D, Chilton MD, Masters-Moore D, Chilton WS (1997) A deletion in an indole synthase gene is responsible for the DIMBOA-deficient phenotype of bxbx maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13345–13350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RC, Steinfath M, Lisec J, Becher M, Witucka-Wall H, Törjék O, Fiehn O, Eckardt A, Willmitzer L, Selbig J, et al. (2007) The metabolic signature related to high plant growth rate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 4759–4764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz-Oron S, Meir S, Malitsky S, Ruppin E, Aharoni A, Shlomi T (2012) Reconstruction of Arabidopsis metabolic network models accounting for subcellular compartmentalization and tissue-specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 339–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BD, Andrew RL, Külheim C, Foley WJ (2014) Explaining intraspecific diversity in plant secondary metabolites in an ecological context. New Phytol 201: 733–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutwil M, Klie S, Tohge T, Giorgi FM, Wilkins O, Campbell MM, Fernie AR, Usadel B, Nikoloski Z, Persson S (2011) PlaNet: combined sequence and expression comparisons across plant networks derived from seven species. Plant Cell 23: 895–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi R, Kusano M, Kobayashi M, Tohge T, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Kogure N, Yamazaki M, Kitajima M, Saito K, Takayama H (2009) Metabolomics-oriented isolation and structure elucidation of 37 compounds including two anthocyanins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 70: 1017–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi R, Saito K (2015) Integrated metabolomics for abiotic stress responses in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 24: 10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi R, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Urano K, Suzuki M, Yamada Y, Nishizawa T, Matsuda F, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Shinozaki K, et al. (2014) Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J 77: 367–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Teo NZ, Shui G, Chua CH, Cheong WF, Parameswaran S, Koizumi R, Ohta H, Wenk MR, Ito T (2014) Transcriptomic and lipidomic profiles of glycerolipids during Arabidopsis flower development. New Phytol 203: 310–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio S, Alba R, Damasceno CMB, Lopez-Casado G, Lohse M, Zanor MI, Tohge T, Usadel B, Rose JKC, Fei Z, et al. (2011) Systems biology of tomato fruit development: combined transcript, protein, and metabolite analysis of tomato transcription factor (nor, rin) and ethylene receptor (Nr) mutants reveals novel regulatory interactions. Plant Physiol 157: 405–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio S, Alba R, Nikoloski Z, Kochevenko A, Fernie AR, Giovannoni JJ (2012) Integrative comparative analyses of transcript and metabolite profiles from pepper and tomato ripening and development stages uncovers species-specific patterns of network regulatory behavior. Plant Physiol 159: 1713–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Wei H, Milne J, Page GP, Somerville CR (2005) Identification of genes required for cellulose synthesis by regression analysis of public microarray data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 8633–8638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick TR, Bräutigam A, Schlüter U, Denton AK, Colmsee C, Scholz U, Fahnenstich H, Pieruschka R, Rascher U, Sonnewald U, et al. (2011) Systems analysis of a maize leaf developmental gradient redefines the current C4 model and provides candidates for regulation. Plant Cell 23: 4208–4220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollier J, Morreel K, Geelen D, Goossens A (2011) Metabolite profiling of triterpene saponins in Medicago truncatula hairy roots by liquid chromatography Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J Nat Prod 74: 1462–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proost S, Van Bel M, Sterck L, Billiau K, Van Parys T, Van de Peer Y, Vandepoele K (2009) PLAZA: a comparative genomics resource to study gene and genome evolution in plants. Plant Cell 21: 3718–3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrana L, Almeida J, Asís R, Duffy T, Dominguez PG, Bermúdez L, Conti G, Corrêa da Silva JV, Peralta IE, Colot V, et al. (2014) Natural occurring epialleles determine vitamin E accumulation in tomato fruits. Nat Commun 5: 3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedelsheimer C, Czedik-Eysenberg A, Grieder C, Lisec J, Technow F, Sulpice R, Altmann T, Stitt M, Willmitzer L, Melchinger AE (2012) Genomic and metabolic prediction of complex heterotic traits in hybrid maize. Nat Genet 44: 217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rontein D, Dieuaide-Noubhani M, Dufourc EJ, Raymond P, Rolin D (2002) The metabolic architecture of plant cells: stability of central metabolism and flexibility of anabolic pathways during the growth cycle of tomato cells. J Biol Chem 277: 43948–43960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Nakabayashi R, Higashi Y, Yamazaki M, Tohge T, Fernie AR (2013) The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis: structural and genetic diversity. Plant Physiol Biochem 72: 21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage C, Segura V, Bauchet G, Stevens R, Do PT, Nikoloski Z, Fernie AR, Causse M (2014) Genome-wide association in tomato reveals 44 candidate loci for fruit metabolic traits. Plant Physiol 165: 1120–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Toyooka K, Kuwahara A, Sakata A, Nagano M, Saito K, Hirai MY (2009) Arabidopsis bile acid:sodium symporter family protein 5 is involved in methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1579–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer N, Semel Y, Roessner U, Gur A, Balbo I, Carrari F, Pleban T, Perez-Melis A, Bruedigam C, Kopka J, et al. (2006) Comprehensive metabolic profiling and phenotyping of interspecific introgression lines for tomato improvement. Nat Biotechnol 24: 447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer N, Zamir D, Fernie AR (2005) Metabolic profiling of leaves and fruit of wild species tomato: a survey of the Solanum lycopersicum complex. J Exp Bot 56: 297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilmiller AL, Moghe GD, Fan P, Ghosh B, Ning J, Jones AD, Last RL (2015) Functionally divergent alleles and duplicated loci encoding an acyltransferase contribute to acylsugar metabolite diversity in Solanum trichomes. Plant Cell 27: 1002–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwender J, Hebbelmann I, Heinzel N, Hildebrandt T, Rogers A, Naik D, Klapperstück M, Braun HP, Schreiber F, Denolf P, et al. (2015) Quantitative multilevel analysis of central metabolism in developing oilseeds of oilseed rape during in vitro culture. Plant Physiol 168: 828–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scossa F, Brotman Y, de Abreu e Lima F, Willmitzer L, Nikoloski Z, Tohge T, Fernie AR (June 5, 2015) Genomics-based strategies for the use of natural variation in the improvement of crop metabolism. Plant Sci http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton D, Stranne M, Mikkelsen L, Pakseresht N, Welham T, Hiraka H, Tabata S, Sato S, Paquette S, Wang TL, et al. (2012) Transcription factors of Lotus: regulation of isoflavonoid biosynthesis requires coordinated changes in transcription factor activity. Plant Physiol 159: 531–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Misra A, Sriram G (2014) Genome-scale models of plant metabolism. Methods Mol Biol 1083: 213–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfath M, Strehmel N, Peters R, Schauer N, Groth D, Hummel J, Steup M, Selbig J, Kopka J, Geigenberger P, et al. (2010) Discovering plant metabolic biomarkers for phenotype prediction using an untargeted approach. Plant Biotechnol J 8: 900–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser MC, Steinhauser D, Koehl K, Carrari F, Gibon Y, Fernie AR, Stitt M (2010) Enzyme activity profiles during fruit development in tomato cultivars and Solanum pennellii. Plant Physiol 153: 80–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephanopoulos G, Vallino JJ (1991) Network rigidity and metabolic engineering in metabolite overproduction. Science 252: 1675–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M. (2013) Systems-integration of plant metabolism: means, motive and opportunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Fernie AR (2003) From measurements of metabolites to metabolomics: an ‘on the fly’ perspective illustrated by recent studies of carbon-nitrogen interactions. Curr Opin Biotechnol 14: 136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Sulpice R, Keurentjes J (2010) Metabolic networks: how to identify key components in the regulation of metabolism and growth. Plant Physiol 152: 428–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudre D, Gutierrez-Carbonell E, Lattanzio G, Rellán-Álvarez R, Gaymard F, Wohlgemuth G, Fiehn O, Alvarez-Fernández A, Zamarreño AM, Bacaicoa E, et al. (2013) Iron-dependent modifications of the flower transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and hormonal content in an Arabidopsis ferritin mutant. J Exp Bot 64: 2665–2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice R, Nikoloski Z, Tschoep H, Antonio C, Kleessen S, Larhlimi A, Selbig J, Ishihara H, Gibon Y, Fernie AR, et al. (2013) Impact of the carbon and nitrogen supply on relationships and connectivity between metabolism and biomass in a broad panel of Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Physiol 162: 347–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice R, Pyl ET, Ishihara H, Trenkamp S, Steinfath M, Witucka-Wall H, Gibon Y, Usadel B, Poree F, Piques MC, et al. (2009) Starch as a major integrator in the regulation of plant growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10348–10353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpice R, Trenkamp S, Steinfath M, Usadel B, Gibon Y, Witucka-Wall H, Pyl ET, Tschoep H, Steinhauser MC, Guenther M, et al. (2010) Network analysis of enzyme activities and metabolite levels and their relationship to biomass in a large panel of Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Cell 22: 2872–2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove LJ, Fell D, Fernie AR (2008) Getting to grips with the plant metabolic network. Biochem J 409: 27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove LJ, Fernie AR (2005) Regulation of metabolic networks: understanding metabolic complexity in the systems biology era. New Phytol 168: 9–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szecowka M, Heise R, Tohge T, Nunes-Nesi A, Vosloh D, Huege J, Feil R, Lunn J, Nikoloski Z, Stitt M, et al. (2013) Metabolic fluxes in an illuminated Arabidopsis rosette. Plant Cell 25: 694–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm S, Florian A, Wittmiß M, Jahnke K, Hagemann M, Fernie AR, Bauwe H (2013) Serine acts as a metabolic signal for the transcriptional control of photorespiration-related genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 162: 379–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer N, Caldana C, Grimbs S, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR, Nikoloski Z (2013) Integration of genome-scale modeling and transcript profiling reveals metabolic pathways underlying light and temperature acclimation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1197–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer N, Scossa F, Fernie A, Nikoloski Z (2014) Variability of metabolite levels is linked to differential metabolic pathways in Arabidopsis’s responses to abiotic stresses. PLoS Comput Biol 10: e1003656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, de Souza LP, Fernie AR (2014) Genome-enabled plant metabolomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 966: 7–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Fernie AR (2010) Combining genetic diversity, informatics and metabolomics to facilitate annotation of plant gene function. Nat Protoc 5: 1210–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Nishiyama Y, Hirai MY, Yano M, Nakajima J, Awazuhara M, Inoue E, Takahashi H, Goodenowe DB, Kitayama M, et al. (2005) Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J 42: 218–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Ramos MS, Nunes-Nesi A, Mutwil M, Giavalisco P, Steinhauser D, Schellenberg M, Willmitzer L, Persson S, Martinoia E, et al. (2011) Toward the storage metabolome: profiling the barley vacuole. Plant Physiol 157: 1469–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Watanabe M, Hoefgen R, Fernie AR (2013a) The evolution of phenylpropanoid metabolism in the green lineage. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 48: 123–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T, Watanabe M, Hoefgen R, Fernie AR (2013b) Shikimate and phenylalanine biosynthesis in the green lineage. Front Plant Sci 4: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]