Abstract

Background

Altered fetal programming due to a suboptimal in utero environment has been shown to increase susceptibility to many diseases later in life. This study examined the effect of alcohol exposure in utero on N-nitroso-N-methylurea (NMU)-induced mammary cancer risk during adulthood.

Methods

Study 1: Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were fed either a liquid diet containing 6.7% ethanol (alcohol-fed), an isocaloric liquid diet (pair-fed), or rat chow ad libitum (ad lib-fed) from day 11 to 21 of gestation. At birth, female pups were cross-fostered to ad lib-fed control dams. Adult offspring were given an I.P. injection of NMU at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight. Mammary glands were palpated for tumors twice a week and rats were euthanized at 23 weeks post-injection. Study 2: To investigate the role of estradiol (E2), animals were exposed to the same in utero treatments, but were not given NMU. Serum was collected during the pre-ovulatory phase of the estrous cycle.

Results

At 16 weeks post-injection, overall tumor multiplicity was greater in the offspring from the alcohol-fed group compared to the control groups, indicating a decrease in tumor latency. At study termination 70% of all animals possessed tumors. Alcohol-exposed animals developed more malignant tumors and more estrogen receptor-α negative tumors relative to the control groups. In addition, IGF binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) mRNA and protein were decreased in tumors of alcohol-exposed animals. Study 2 showed that alcohol-fed animals had significantly increased circulating E2 when compared to either control group.

Conclusions

These data indicate that alcohol exposure in utero increases susceptibility to mammary tumorigenesis in adulthood and suggest that alterations in the IGF and E2 systems may play a role in the underlying mechanism.

Keywords: mammary cancer, fetal alcohol exposure, estradiol, estrogen receptor, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5

Introduction

The National Cancer Institute estimated that there would be 40,170 deaths due to breast cancer (Horner et al., 2009), and the American Cancer Society predicted 192,370 new cases of invasive breast cancer among American women in 2009 (American Cancer Society, 2009). While considerable gains have been made in establishing new therapies for breast cancer treatment, the underlying causes of breast cancer remain poorly delineated. The idea that environmental exposures and lifestyle choices during pregnancy may affect the offspring’s risk of breast cancer is a newly emerging concept (Hilakivi-Clarke and de Assis, 2006; Soto et al., 2008; Trichopoulos, 1990). For example, studies have indicated that gestational exposure to bisphenol A, an estrogenic compound found in many consumer products, induced the development of mammary gland neoplasias in adult rats (Murray et al., 2007). Similarly, animal studies have shown that offspring from mothers consuming a high fat diet during pregnancy have an increased susceptibility to a mammary carcinogen (Hilakivi-Clarke et al., 1997). Furthermore, using rats as a model system, alcohol exposure in utero has been shown to increase susceptibility to chemically-induced mammary tumors in offspring (Hilakivi-Clarke et al., 2004). This is particularly alarming as the Centers for Disease Control report that 52.6% of women of child-bearing age consume alcohol (Centers for Disease Control, 2004). Even more striking is that in the United States 1 in 12 pregnant women admit drinking alcohol and 1 in 30 pregnant women admit binge drinking (five or more drinks at a time) (Centers for Disease Control, 2009).

Estradiol (E2) plays an integral role in mammary gland development as well as breast cancer progression (Bocchinfuso et al., 2000; Russo and Russo, 2008). It is widely accepted that a woman’s lifetime exposure to both environmental and endogenous E2 affects her risk for breast cancer (Feigelson and Henderson, 1996). Furthermore, epidemiological studies have shown that a higher circulating E2 level is associated with increased breast cancer risk (Hankinson, 2005). Recent data suggest that circulating E2 may be altered in offspring of rats exposed to alcohol in utero (Lan et al., 2009). This finding, together with the finding of Hilakivi-Clarke et al. (2004), that prenatal exposure to alcohol alters mammary morphology, suggests that E2 may contribute to the increased susceptibility to mammary carcinogens in these animals.

Considerable evidence suggests that E2 and estrogen receptor-α (ER-α) cross-talk with peptide growth factors, including insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) (Lanzino et al., 2008; Thorne and Lee, 2003). The IGF system is comprised of IGF-I and -II ligands that signal through the IGF-I receptor and six binding proteins (IGFBP-1-6) and is important in breast cancer etiology (Jones and Moorehead, 2008; Kleinberg et al., 2009; Sachdev and Yee, 2001). It is possible that E2 interacts with the IGF-I system either systemically or in the local environment of the mammary gland to promote tumorigenesis in animals exposed to alcohol in utero. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine the effect of alcohol exposure in utero on risk of mammary carcinogenesis, characterize the resulting tumor phenotype, and determine a potential role for alterations in the E2 and IGF systems in mediating this effect.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and individually housed in a controlled environment with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Dams were fed a liquid diet containing ethanol (alcohol-fed) (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ), an isocaloric liquid diet (pair-fed) (Bio-Serv), or ad libitum rat chow (ad lib-fed) (Purina Mills Lab Diet, St. Louis, MO). Dams were acclimated to the alcohol diet from d 7 to 11 of gestation by feeding a liquid diet containing 2.2% ethanol on d 7 and 8 and 4.4% ethanol on d 9 and 10. Once acclimated, dams were fed the liquid diet containing 6.7% ethanol from d 11-21, which represented 35% of total calories. At birth female pups were cross-fostered to ad lib-fed dams and litters were normalized to 8 pups per dam. Pups were weaned at 21 d of age and fed rat chow ad libitum for the remainder of the experiment. Animal care was performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and complied with National Institutes of Health policy.

Study 1

Ten female pups from each treatment group were administered a single intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection of 50 mg/kg body weight N-nitroso-N-methylurea (NMU) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to induce mammary tumors. Five female pups from each group were administered vehicle (0.9% NaCl) to determine if spontaneous mammary tumors were observed in any treatment group. NMU and vehicle injections were given at approximately 50 days of age. Rats were weighed weekly and mammary glands were palpated twice a week to assess tumor latency. Rats were euthanized by decapitation at 23 weeks after NMU injection. A full necropsy was performed and all major organs were macroscopically examined to ensure the carcinogen was mammary-specific. Mammary tumors were harvested and half of each tumor was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological analysis. The remaining half was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA analysis.

Study 2

In order to determine the effect of alcohol exposure in utero on circulating E2 in the offspring, a second study was conducted without NMU. Beginning at day 42 of age, the estrous cycle was monitored (n = 13 per group) by daily vaginal cytology for two to three weeks. Once animals were exhibiting normal 4-day cycles, they were euthanized during proestrus by rapid decapitation between 62 and 76 days of age. Trunk blood was collected to assess circulating E2 and IGF-I concentrations.

Histology

Fixed tissue was dehydrated, cleared, and embedded in Paraplast using facilities located in the Histopathology Core of The Environmental Occupational Health Sciences Institute (EOHSI) at Rutgers University. Samples were sectioned at 6 μm and placed on slides. Slides were baked for 30 min at 60°C, followed by deparaffinization in xylene and rehydration in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Slides were evaluated by toxicological pathologist Dr. Kenneth Reuhl, who was blinded to treatment.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

For ER-α staining, samples were processed as described above. Slides were baked at 60°C for 30 min, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in isopropanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling slides in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer for 10 min. After cooling, slides were submerged in 3% H2O2 for 5 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, blocked in normal horse serum (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 20 min, and incubated with rabbit ER-α primary antibody (1:200) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C. On each slide, one section was incubated with rabbit isotype IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as a negative control. The next day, slides were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200) (Santa Cruz) for 40 min, then with ABC reagent from the ABC Elite Vectastain kit (Vector Labs) for 40 min. After rinsing in tris-buffered saline, slides were submerged in 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) for 7 min, counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific). Three members of the laboratory viewed all tumors blindly and classified them as highly positive, positive, mostly negative, or negative. Tumors determined to be highly positive and positive were combined and termed positive, while those determined to be mostly negative and negative were combined and termed negative.

Western Immunoblot Analysis

Frozen tissue was sheared in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) lysis buffer then incubated on ice for 1 hr. The protein lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × G for 5 min at 4°C. The upper fat layer was removed and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. Protein concentration was determined using a BioRad protein assay (Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred, then immunoblotted using an IGFBP-5 antibody (Santa Cruz) followed by a β-actin-specific antibody (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) as previously described (Fleming et al., 2005). Protein from a single tumor sample was run on each gel as a calibrator. Densitometry was performed using an Alphaimager imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). Bands were corrected for loading using actin, then normalized to the calibrator for comparison across gels.

Serum Analysis

Serum was analyzed for E2 by a competitive enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) (sensitivity = 20 pg/ml), and for IGF-I using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Immunodiagnostic Systems, Fountain Hills, AZ) (sensitivity = 63 ng/ml) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. All samples were run on one 96 well plate for each variable.

RNA Analysis

Frozen mammary tissue was homogenized in Trizol (Sigma) and RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. RNA was treated with DNase (Qiagen) during isolation. RNA quality was verified using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems (ABI), Foster City, CA) was used to reverse transcribe 2 μg of RNA. Primer sets were developed using PrimerQuest (IDT, Coralville, IA), and each primer set was validated as previously described (Fleming et al., 2005). Primer sets for IGFBP-5 (forward, 5’-TTGAGGAAACTGAGGACCTCGGAA-3’; reverse, 5’-CCTTCTCTGTCCGTTCAACTTGCT-3’), and actin (forward, 5’-CCATTGAACACGGCATTGTCACCA-3’; reverse, 5’-GCCACACGCAGCTCATTGTAGAAA-3’) were obtained from Sigma Genosys (St. Louis, MO). Samples were diluted 1:4 and 5 μl were amplified in a 20 μl reaction mix containing 10 μl Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (ABI), 4 μl ultrapure H2O, and 0.5 μl (200 μM) of each forward and reverse gene-specific primer. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on 384 well plates (ABI) using an ABI 7900 HT Real-Time PCR system. For each experimental sample, fold-change relative to a calibrator sample was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method with actin as the housekeeping gene. The calibrator sample represented a pool of tumor RNA consisting of 2 RNA samples from each of the 3 treatment groups.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in body weight, tumors per group, and tumors per animal were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one way ANOVA, with a Dunn’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc analysis at the level of α = 0.05. Percent of rats with tumors was analyzed using a logrank test at the level of α = 0.05. To evaluate tumor type, a Chi Square test was performed. ER positivity was evaluated using two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test at the level of α = 0.05. Differences in circulating E2 and IGF-I levels were assessed using one way ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis at the level of α = 0.05. IGFBP-5 mRNA and protein values were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one way ANOVA, with a Dunn’s Multiple comparison post-hoc test at the level of α = 0.05.

Results

Mammary tumorigenesis is increased in animals exposed to alcohol in utero

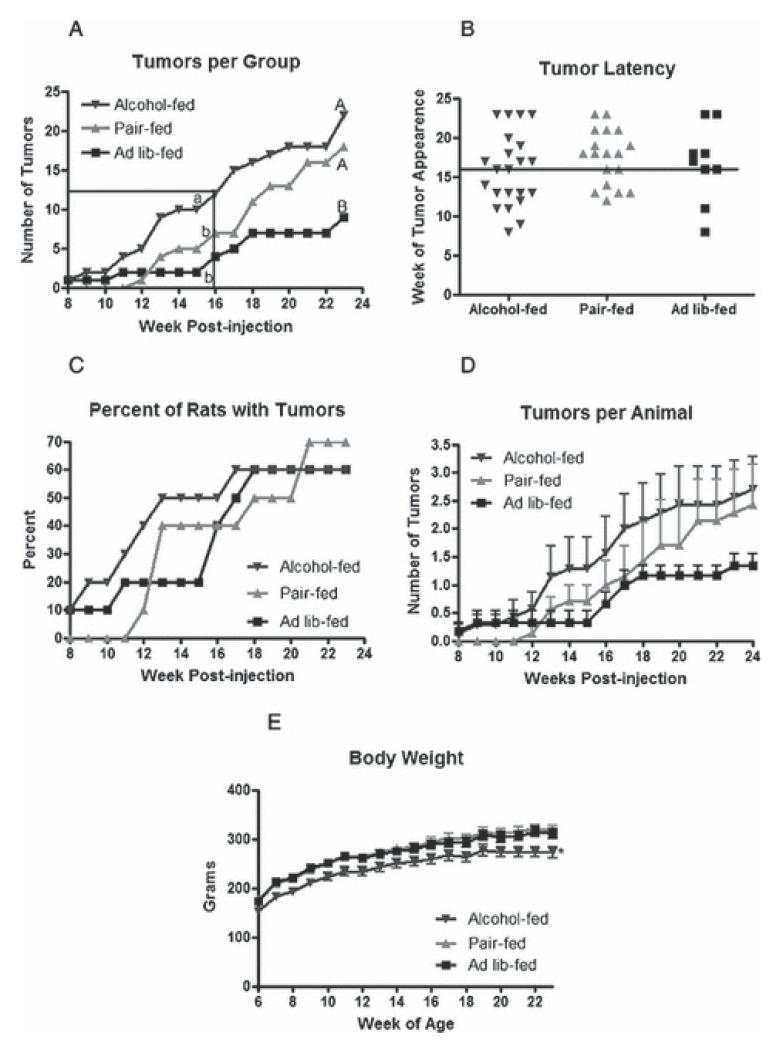

Mammary tumors were first detected at 8 weeks post-NMU injection, with one tumor present in the alcohol-fed group and one in the ad lib-fed control group (Fig. 1a). Thereafter, tumor number increased steadily in the alcohol-fed group, while only two tumors were detected through week 15 in the ad lib-fed control group. Tumors were not detected in the pair-fed control group until 12 weeks post injection. From this point, the rate of increase in tumor number paralleled that of the alcohol-fed group, but the absolute number of tumors remained lower in the pair-fed control group at all time points. At week 16 post-injection, the alcohol-fed group had significantly more tumors, while the number of tumors in the pair-fed control and ad lib-fed control groups did not differ from each other, indicating that tumor latency was decreased by alcohol exposure in utero (Fig. 1a and b). The percent of rats with palpable tumors was similar by 13 weeks post-injection in the alcohol-fed and pair-fed control groups, while remaining lower in the ad lib-fed control group (Fig. 1c). Greater overall tumor multiplicity in the alcohol-fed group at this time was due to the finding that, in general, animals in the alcohol-fed group exhibited more tumors per animal at each time point (Fig. 1d). Rats that received vehicle alone did not develop tumors.

Figure 1.

Alcohol exposure in utero enhances mammary tumorigenesis.

Animals exposed to alcohol in utero and control rats not exposed were administered a single I.P. injection of NMU at 50 mg/kg at approximately 50 days of age. Rats were palpated for tumors twice a week following injections. (a) Total number of tumors per treatment group each week post NMU injection. The boxed area represents when 50% tumor incidence was reached across all groups. Two time intervals were analyzed: 8-16 weeks (lower case letters, P < 0.05, n=10), and 8-23 weeks (upper case letters, P < 0.05, n=10). (b) Week of tumor appearance. Each data point represents an individual tumor. The horizontal line at week 16 post-injection represents when 50% tumor incidence occurred. (c) Percent of rats presenting with tumors each week post NMU injection, P = 0.9494, n=10. (d) Average number of tumors per animal in each group ± SEM. (e) Average body weight ± SEM with * denoting a significant difference (P < 0.005, n=10). Data in panels a, d, and e were analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one way ANOVA with a Dunn’s Multiple Comparison post-hoc analysis at the level of α = 0.05, and panel c was analyzed using a log-rank test.

In order to determine if overall tumor multiplicity in response to NMU was increased by exposure to alcohol in utero, the study was continued until tumor numbers had reached a plateau in all groups. At 23 weeks post-injection, 60 to 70% of rats in each group injected with NMU presented with tumors (Fig. 1c). At study termination, the alcohol-fed group was no longer different from the pair-fed control group, but remained different from the ad lib-fed control group. As expected, animals exposed to alcohol exhibited decreased body weight that was maintained over the course of the study compared to either control group (Fig. 1e).

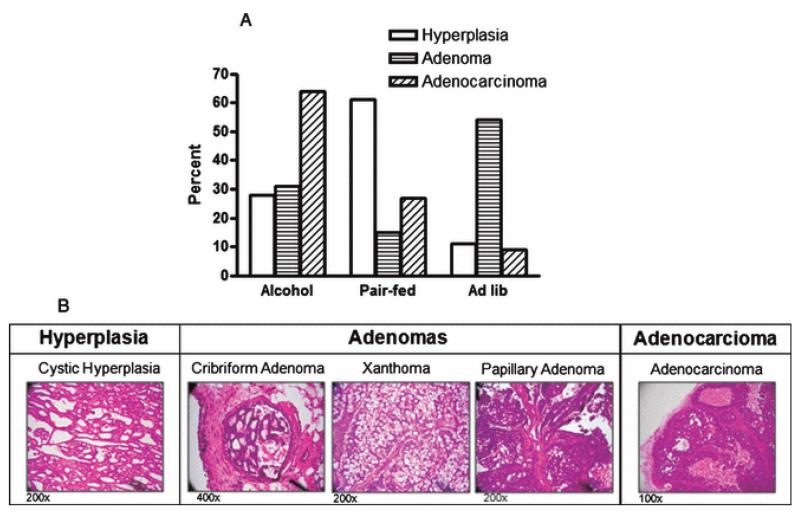

Tumor stage is altered in animals exposed to alcohol

The stage of progression of each tumor was evaluated by histological analysis (Fig. 2). For tumor classification, ductal/cystic hyperplasia was defined by increased proliferation of benign glandular structures, with predominantly regular cells and nuclei. Adenomas were defined by a more solid phase glandular structure with regular cells and nuclei still predominating. Adenocarcinomas presented primarily as solid-phase lesions containing many atypical and anaplastic cells, a high mitotic rate (including numerous atypical mitoses) and observable zones of tumor necrosis. Rats exposed to alcohol in utero developed more adenocarcinomas compared to the other two groups (Table 1). Animals in the pair-fed group developed mostly hyperplastic tumors, with few adenocarcinomas or adenomas. The ad lib-fed group contained mostly adenomas with only moderate hyperplasia and few adenocarcinomas. Treatment was found to be associated with histological tumor type (Fig. 2a). These data suggest that in utero exposure to alcohol leads to a more malignant phenotype in response to a carcinogenic insult.

Figure 2.

Alcohol exposure in utero results in altered tumor development.

Tumors were hematoxylin and eosin stained for histological evaluation. (a) Percent of tumors of each histological tumor type per treatment group (P < 0.01, n=15; Chi-square test). (b) Representative images of different histological tumor types induced in response to NMU.

Table 1.

Number of specific histological tumor type per group.

| Hyperplasia | Adenoma | Adenocarcinoma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Number of Tumors |

na | Tumors per animal |

Number of Tumors |

na | Tumors per animal |

Number of Tumors |

na | Tumors per animal |

| Alcohol-fed | 5 | 3 | 1-3 | 4 | 3 | 1-2 | 7 | 3 | 2-3 |

| Pair-fed | 11 | 6 | 1-3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Ad lib-fed | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 1-2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

n = number of rats.

Animals exposed to alcohol in utero developed more ER negative tumors

IHC was conducted to determine if tumors were ER positive or ER negative. Overall, 27 tumors stained positive and 15 tumors stained negative. Animals exposed to alcohol in utero developed more ER negative tumors in response to NMU compared with the two control groups, which did not differ from each other (Fig. 3a). Representative tumors that were considered ER positive and ER negative are shown in Fig. 3b.

Figure 3.

Alcohol exposure in utero results in more ER negative tumors.

Tumors were stained for ER-α as described in the Materials and Methods. (a) Percent of positive or negative tumors in each group. One tumor was arbitrarily chosen from each animal for statistical analysis. Lower case letters denote a statistically significant difference from either control group (P < 0.001, n=6; two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test at the level of α = 0.05). (b) Representative images of ER-positive and ER-negative tumors are shown, the 400x magnification represents the boxed area on the 200x magnification. H & E = hematoxylin and eosin; Negative Control = non-specific IgG.

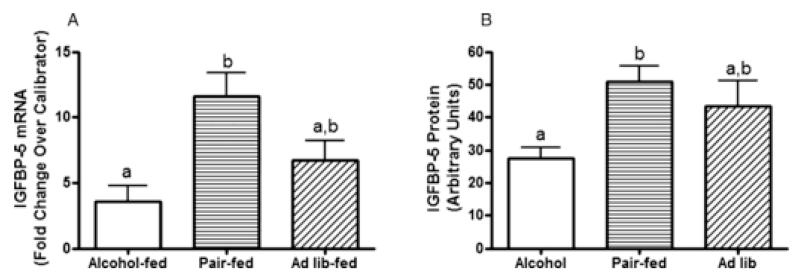

IGFBP-5 mRNA and protein are suppressed in tumors developed in alcohol-exposed animals

The IGF system is involved in both normal mammary gland biology as well as mammary cancer. Therefore, we analyzed mRNA levels in tumor tissue of IGFR, IGF-I, IGFBP-3, and IGFBP-5. While no differences in IGFR, IGF-I, or IGFBP-3 mRNA were detected in tumors across treatment groups (data not shown), animals exposed to alcohol in utero developed tumors with reduced levels of IGFBP-5 mRNA compared to tumors that developed in pair-fed control animals (Fig. 4a). Western blot analysis indicated that this difference in IGFBP-5 expression was also observed at the protein level (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

IGFBP-5 mRNA and protein expression is reduced in tumors of animals exposed to alcohol in utero.

All mammary tumors were collected at necropsy and one tumor from each animal was randomly selected from each animal for analysis. (a) Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to determine IGFBP-5 mRNA expression. Fold-change was calculated relative to a calibrator using the 2−ΔΔCT method with actin as the housekeeping gene. The calibrator consisted of a pool of tumor RNA including 2 samples from each treatment group. (P < 0.05, n = 7; non-parametric one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post-test at the level of α = 0.05). (b) Western immunoblot was performed using an IGFBP-5 specific antibody. Samples were corrected for loading with actin. (P<0.01, n=7; non-parametric one way ANOVA with Dunn’s post-test at the level of α=0.05).

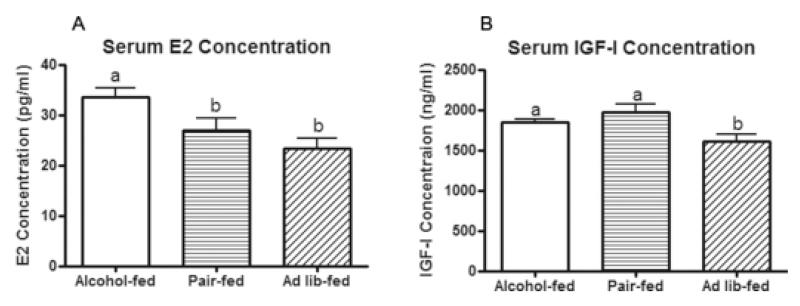

Circulating E2 and IGF-I are altered in animals exposed to alcohol in utero

In a second study, pregnant dams were again fed the same dietary treatments (alcohol-fed, pair-fed, and ad lib-fed from day 11-21 of gestation). Offspring were sacrificed during the proestrus stage of the estrous cycle. Rats exposed to alcohol in utero displayed higher circulating E2 compared to the two control groups, which did not differ from each other (Fig. 5a). Circulating IGF-I was increased in the alcohol group compared to the ad lib group, while the alcohol group was not different from the pair-fed group (Fig. 5b). These data suggest that alterations in circulating E2 and possibly IGF-I may be involved in the increased tumorigenesis that is observed in animals exposed to alcohol in utero.

Figure 5.

Circulating E2 and IGF-I are altered in pups exposed to alcohol in utero.

Pups exposed to alcohol in utero and controls not exposed were sacrificed during proestrus. Serum E2 and IGF-I were determined by EIA and ELISA, respectively. Statistical significance is denoted by different letters (P < 0.05, n = 13; one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls post-test at the level of α = 0.05).

Discussion

Many diseases have been linked to a suboptimal fetal environment, including hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease (Jones and Ozanne, 2007; Law and Shiell, 1996; Osmond et al., 1993). While a connection between the fetal environment and breast cancer has been proposed (Hilakivi-Clarke et al., 1995; Hilakivi-Clarke and de Assis, 2006; Trichopoulos, 1990), only one previous study has addressed alcohol as the fetal insult (Hilakivi-Clarke et al., 2004). In the present study, pregnant dams were fed 6.7% alcohol. The expected blood alcohol levels in these animals would be 100 to 150 mg/dl (Mihalick et al., 2001; Miller, 1992), which would be equivalent to three to five drinks in two hours for a woman (Leeman et al., 2010). Offspring of the alcohol-fed dams exhibited an increase in tumor multiplicity in response to NMU at 16 weeks post-injection. A similar result was observed by Hilakivi-Clarke et. al (2004) using a more moderate level of alcohol, though no effect on tumor multiplicity was observed when dams were fed a low level of alcohol. Thus, the results of these two studies indicate that both moderate to high alcohol intake during pregnancy may significantly impact breast cancer susceptibility in offspring.

Hilakivi-Clarke et al. (2004) reported that circulating maternal E2 increased when dams were drinking alcohol and suggested that this may play a role in the increased risk for mammary tumors in the offspring. While E2 levels were not measured in the dams in the present study, we did find that circulating E2 levels were significantly higher during proestrus in the alcohol-exposed offspring. It is widely accepted that a woman’s endogenous E2 levels over her lifetime can affect her breast cancer risk, therefore, this could be a contributing factor to the increase in mammary tumor susceptibility observed in the offspring in the present study. Recently, Lan and co-workers found that E2 was higher during proestrus compared to other phases of the cycle in both rat offspring exposed to alcohol as well as pair-fed controls relative to ad lib-fed controls (Lan et al., 2009). However, in the Lan et al. study, alcohol-exposed and pair-fed pups remained with their dams after birth, with both groups weighing less throughout the study relative to ad-lib fed controls. Therefore, the authors concluded that these differences were largely due to nutritional status. In the present study, all animals nursed from dams that did not receive alcohol. The offspring of the two control groups were of similar weight throughout the study, with only the alcohol-exposed offspring showing a reduced body weight and an increase in circulating E2 levels.

Increased circulating E2 levels could contribute to mammary tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms (Russo and Russo, 2008). E2 metabolites such as 2- and 4-OH-E2 have been shown to directly bind DNA and introduce DNA adducts, thus inducing mutagenesis (Cavalieri and Rogan, 2006; Santen et al., 2009). In addition, the conversion of E2 to 4-OH-E2 during E2 metabolism results in the formation of reactive oxygen species that are also carcinogenic (Yager and Davidson, 2006). E2 may contribute to tumor susceptibility by activating ER-α and promoting cell proliferation. This can occur through both classical genomic effects as well as more recently recognized non-genomic effects (Bjornstrom and Sjoberg, 2005). The classical ligand-dependent mode of E2 action involves binding of the E2/ER-α complex to specific estrogen response elements (EREs) and enhancers located within the regulatory regions of target genes (Mangelsdorf et al., 1995). In addition, this complex can upregulate expression of genes that lack classical EREs by binding to other DNA-bound transcription factors that tether the activated ER to DNA (McKenna et al., 1999). In contrast, the non-genomic effects of ER may involve cross-talk with tyrosine kinase receptors including IGFR at the level of the plasma membrane (Fagan and Yee, 2008; Song and Santen, 2006).

In addition to cross-talk with the IGF signaling pathway, E2 can also upregulate expression of individual components of the IGF signaling pathway (Fagan and Yee, 2008). For example, E2 can increase IGFR expression, as well as that of IRS-1 in breast cancer cells (Lee et al., 1999; Stewart et al., 1990). This regulation is also observed in vivo in mammary tissue of ovariectomized rats and mice (Chan et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003). While we found no differences in mRNA levels of IGFR, IGF-I, or IGFBP-3 between tumors from the three treatment groups in the present study, we found that IGFBP-5 mRNA and protein were significantly reduced in the tumor tissue from alcohol-exposed rats when compared to pair-fed controls.

A large body of evidence supports a role for IGFBP-5 as a growth-inhibitory and/or pro-apoptotic factor in the mammary gland. Many studies have shown a strong positive relationship between IGFBP-5 expression and the occurrence of cell death during mammary involution (Boutinaud et al., 2004; Flint et al., 2005; Phillips et al., 2003). Transgenic overexpression of IGFBP-5 in mammary tissue resulted in increased apoptotic death of epithelial cells and reduced invasion of the mammary fat pad, while addition of exogenous IGFBP-5 to murine mammary epithelial cells suppressed IGF-I mediated survival (Marshman et al., 2003; Tonner et al., 2002). Furthermore, addition of exogenous IGFBP-5 to human breast cancer cells inhibited growth in vitro (Butt et al., 2003). Many of these pro-apoptotic, growth-inhibitory effects have been thought to be related to the ability of IGFBP-5 to sequester IGF-I and prevent its pro-survival and growth-stimulatory effects. Therefore, in the present study the decrease in IGFBP-5 expression in tumors of rats exposed to alcohol in utero may have allowed more free IGF-I to access the IGFR and promote tumorigenesis. However, we cannot rule out IGF-independent roles for IGFBP-5, which have also been suggested (Akkiprik et al., 2008).

Interestingly, previous work has shown an inverse correlation between E2 and IGFBP-5 expression in breast cancer cells. In MCF-7 cells, E2 decreased IGFBP-5 expression while the anti-estrogen ICI 182780 (ICI) increased IGFBP-5 expression (Huynh et al., 1996; Parisot et al., 1999). Similarly, ICI stimulated IGFBP-5 expression in DMBA-induced mammary tumors (Huynh et al., 1996). These authors also showed that reducing IGFBP-5 expression in MCF-7 cells with IGFBP-5 antisense oligonucleotides increased DNA synthesis in both untreated and ICI-treated MCF-7 cells. They therefore suggested that E2-stimulated proliferation involved reducing the inhibitory effect of IGFBP-5. These findings support the present study where increases in circulating E2 and decreases in tumor IGFBP-5 expression were observed in animals that exhibited an overall increase in tumorigenesis in response to NMU. It is interesting to speculate that this may represent an IGF-independent mechanism of growth inhibition by IGFBP-5.

Interestingly, at study termination the alcohol-exposed animals had more ER negative tumors as well as more adenocarcinomas. In the polyoma middle T oncoprotein (PyMT) mouse model of mammary tumor progression, Lin et al. (2003) showed that mammary tumors in these mice lost ER positivity as they progressed to the more malignant phenotype (Lin et al., 2003). These data support our findings that mammary tumors that arise in alcohol-exposed offspring are more likely to progress to a malignant phenotype compared to animals that are not exposed to alcohol in utero.

The results of the present study show that alcohol exposure in utero leads to an increased susceptibility to mammary carcinogenesis in adulthood. Furthermore, the resulting tumors are characterized by a more malignant phenotype with increased ER-negative status. The idea that alcohol exposure in utero leads to tumors with a worse prognosis is a novel finding and warrants future investigation into the mechanisms that underlie this tumor phenotype. Our data also show that E2 and components of the IGF system may play a role in this enhanced susceptibility. Further studies will be aimed at delineating the mechanisms by which the E2 and IGF systems are altered by alcohol exposure in utero.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R37 AA08757 to DKS and F31CA132620 to TAP), The Charles and Johanna Busch Memorial Fund and the NJ Agricultural Experiment Station (Rutgers University to WSC), and by facilities supported by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences Center (E05022).

Contributor Information

Tiffany A. Polanco, Rutgers Endocrine Program, Department of Animal Sciences; Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 59 Dudley Rd, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, tpolanco@eden.rutgers.edu

Catina Crismale-Gann, Rutgers Endocrine Program, Department of Animal Sciences; Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 59 Dudley Rd, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, ccrismal@eden.rutgers.edu

Kenneth R. Reuhl, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy; Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 41 Gordon Rd, Piscataway, NJ 08854, reuhl@eohsi.rutgers.edu

Dipak K. Sarkar, Rutgers Endocrine Program, Department of Animal Sciences; Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 67 Poultry Farm Rd, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, sarkar@aesop.rutgers.edu

References

- Akkiprik M, Feng Y, Wang H, Chen K, Hu L, Sahin A, Krishnamurthy S, Ozer A, Hao X, Zhang W. Multifunctional roles of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society AC . Cancer Facts and Figures 2009. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornstrom L, Sjoberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchinfuso WP, Lindzey JK, Hewitt SC, Clark JA, Myers PH, Cooper R, Korach KS. Induction of mammary gland development in estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2982–2994. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutinaud M, Shand JH, Park MA, Phillips K, Beattie J, Flint DJ, Allan GJ. A quantitative RT-PCR study of the mRNA expression profile of the IGF axis during mammary gland development. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:195–207. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0330195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AJ, Dickson KA, McDougall F, Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29676–29685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri E, Rogan E. Catechol quinones of estrogens in the initiation of breast, prostate, and other human cancers: keynote lecture. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:286–301. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TW, Pollak M, Huynh H. Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor signaling pathways in mammary gland by pure antiestrogen ICI 182,780. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2545–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Alcohol consumption among women who are pregnant or who might become pregnant - United States, 2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:1178–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age---United States, 1991-2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan DH, Yee D. Crosstalk between IGF1R and estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13:423–429. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigelson HS, Henderson BE. Estrogens and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2279–2284. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.11.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JM, Leibowitz BJ, Kerr DE, Cohick WS. IGF-I differentially regulates IGF-binding protein expression in primary mammary fibroblasts and epithelial cells. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:165–178. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint DJ, Boutinaud M, Tonner E, Wilde CJ, Hurley W, Accorsi PA, Kolb AF, Whitelaw CB, Beattie J, Allan GJ. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins initiate cell death and extracellular matrix remodeling in the mammary gland. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2005;29:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson SE. Endogenous hormones and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Breast Dis. 2005;24:3–15. doi: 10.3233/bd-2006-24102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Cabanes A, de Assis S, Wang M, Khan G, Shoemaker WJ, Stevens RG. In utero alcohol exposure increases mammary tumorigenesis in rats. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2225–2231. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Cho E, Raygada M, Onojafe I, Clarke R, Lippman ME. Early life affects the risk of developing breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;768:327–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb12152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, Clarke R, Onojafe I, Raygada M, Cho E, Lippman M. A maternal diet high in n - 6 polyunsaturated fats alters mammary gland development, puberty onset, and breast cancer risk among female rat offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9372–9377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilakivi-Clarke L, de Assis S. Fetal origins of breast cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner MJ, Reis LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Lewis DR, Eisner MP, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006. eds. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/: based on November 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh H, Yang XF, Pollak M. A role for insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 in the antiproliferative action of the antiestrogen ICI 182780. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1501–1506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Moorehead RA. The impact of transgenic IGF-IR overexpression on mammary development and tumorigenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RH, Ozanne SE. Intra-uterine origins of type 2 diabetes. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:25–29. doi: 10.1080/13813450701318484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg DL, Wood TL, Furth PA, Lee AV. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in the transition from normal mammary development to preneoplastic mammary lesions. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:51–74. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan N, Yamashita F, Halpert AG, Sliwowska JH, Viau V, Weinberg J. Effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function across the estrous cycle. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1075–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzino M, Morelli C, Garofalo C, Panno ML, Mauro L, Ando S, Sisci D. Interaction between estrogen receptor alpha and insulin/IGF signaling in breast cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:597–610. doi: 10.2174/156800908786241104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law CM, Shiell AW. Is blood pressure inversely related to birth weight? The strength of evidence from a systematic review of the literature. J Hypertens. 1996;14:935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AV, Jackson JG, Gooch JL, Hilsenbeck SG, Coronado-Heinsohn E, Osborne CK, Yee D. Enhancement of insulin-like growth factor signaling in human breast cancer: estrogen regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:787–796. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AV, Zhang P, Ivanova M, Bonnette S, Oesterreich S, Rosen JM, Grimm S, Hovey RC, Vonderhaar BK, Kahn CR, Torres D, George J, Mohsin S, Allred DC, Hadsell DL. Developmental and hormonal signals dramatically alter the localization and abundance of insulin receptor substrate proteins in the mammary gland. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2683–2694. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Heilig M, Cunningham CL, Stephens DN, Duka T, O’Malley SS. Ethanol consumption: how should we measure it? Achieving consilience between human and animal phenotypes. Addict Biol. 2010;15:109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Jones JG, Li P, Zhu L, Whitney KD, Muller WJ, Pollard JW. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2113–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshman E, Green KA, Flint DJ, White A, Streuli CH, Westwood M. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:675–682. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalick SM, Crandall JE, Langlois JC, Krienke JD, Dube WV. Prenatal ethanol exposure, generalized learning impairment, and medial prefrontal cortical deficits in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Circadian rhythm of cell proliferation in the telencephalic ventricular zone: effect of in utero exposure to ethanol. Brain Res. 1992;595:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91447-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray TJ, Maffini MV, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Induction of mammary gland ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ following fetal bisphenol A exposure. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond C, Barker DJ, Winter PD, Fall CH, Simmonds SJ. Early growth and death from cardiovascular disease in women. BMJ. 1993;307:1519–1524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6918.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisot JP, Leeding KS, Hu XF, DeLuise M, Zalcberg JR, Bach LA. Induction of insulin-like growth factor binding protein expression by ICI 182,780 in a tamoxifen-resistant human breast cancer cell line. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;55:231–242. doi: 10.1023/a:1006274712664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips K, Park MA, Quarrie LH, Boutinaud M, Lochrie JD, Flint DJ, Allan GJ, Beattie J. Hormonal control of IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-5 and IGFBP-2 secretion during differentiation of the HC11 mouse mammary epithelial cell line. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:197–208. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo J, Russo IH. Breast development, hormones and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;630:52–56. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78818-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev D, Yee D. The IGF system and breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:197–209. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen R, Cavalieri E, Rogan E, Russo J, Guttenplan J, Ingle J, Yue W. Estrogen mediation of breast tumor formation involves estrogen receptor-dependent, as well as independent, genotoxic effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1155:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX, Santen RJ. Membrane initiated estrogen signaling in breast cancer. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:9–16. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto AM, Vandenberg LN, Maffini MV, Sonnenschein C. Does breast cancer start in the womb? Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ, Johnson AD, May FEB, Westley BR. Role of the insulin-like growth factors and the type-I insulin-like growth factor receptor in the estrogen-stimulted proliferation of human breast cancer cells. J.Biol.Chem. 1990;265:21172–21178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne C, Lee AV. Cross talk between estrogen receptor and IGF signaling in normal mammary gland development and breast cancer. Breast Dis. 2003;17:105–114. doi: 10.3233/bd-2003-17110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonner E, Barber MC, Allan GJ, Beattie J, Webster J, Whitelaw CB, Flint DJ. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) induces premature cell death in the mammary glands of transgenic mice. Development. 2002;129:4547–4557. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos D. Hypothesis: does breast cancer originate in utero? Lancet. 1990;335:939–940. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91000-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JD, Davidson NE. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]