Abstract

Background

In previous research, neighborhood deprivation was positively associated with body mass index (BMI) among adults with diabetes. We assessed whether the association between neighborhood deprivation and BMI is attributable, in part, to geographic variation in the availability of healthful and unhealthful food vendors.

Methods

Subjects were 16,634 participants of the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE), a multiethnic cohort of adults living with diabetes. Neighborhood deprivation and healthful (supermarket and produce) and unhealthful (fast food outlets and convenience stores) food vendor kernel density were calculated at each participant's residential block centroid. We estimated the total effect, controlled direct effect, natural direct effect, and natural indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI. Mediation effects were estimated using G-computation, a maximum likelihood substitution estimator of the G-formula that allows for complex data relationships such as multiple mediators and sequential causal pathways.

Results

We estimated that if neighborhood deprivation were reduced from the most deprived to the least deprived quartile, average BMI would change by −0.73 units (95% CI −1.05, −0.32); however, we did not detect evidence of mediation by food vendor density. In contrast to previous findings, a simulated reduction in neighborhood deprivation from the most deprived to the least deprived quartile was associated with dramatic declines in both healthful and unhealthful food vendor density.

Introduction

Neighborhood deprivation indices are composite measures of area socioeconomic status (SES) commonly used in early neighborhood effects research as crude proxies for area-level deprivation and as predictors of health access and outcomes.1 Much of our understanding of the relevance of place to health comes from these early ecologic and multilevel studies of the relationship between neighborhood deprivation and disease risk.2 Our previous research found that, independent of personal characteristics, neighborhood deprivation index had a significant positive and monotonic relationship with body mass index (BMI) and cardiometabolic risk factor control among adults with diabetes.3 Diabetes is a chronic disease influenced by health-related behaviors including diet and exercise, and thus place-based interventions that promote weight loss or simply weight maintenance may improve long term diabetes outcomes.4

The pathways through which neighborhood deprivation index affects BMI are not well understood, but the food retail environment has been proposed as an important mediator and has been shown to have strong cross-sectional associations with BMI in both healthy and chronically ill populations.5–7 Our previous analysis of the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) found that among moderate to high-income subjects, greater neighborhood healthful food retail density was associated with lower obesity prevalence.8 However, no studies to date examine whether and how much geographic variation in food retail density accounts for neighborhood-level socioeconomic disparities in BMI.

Is neighborhood density of retail food outlets a major contributor to the BMI disparities we observed between more- and less-deprived neighborhoods in this population with diabetes? To address this question, we estimated the total effect, the controlled direct effect, the natural direct effect, and the natural indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI through food retail density, accounting for sequential impacts on intermediate behavioral variables along the causal chain. To accommodate complex data relationships, we used G-computation, a causal inference technique based on the Rubin Causal Model counterfactual framework.9,10

We hypothesized that the effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI is explained in part by geographic variation in healthful and unhealthful food vendor density among those living with diabetes. Using data from DISTANCE, a well-characterized, multi-ethnic cohort of Californian adults with diabetes, we estimated the share of the total effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI that was explained by differences in food retail density between most and least deprived neighborhoods. Additionally, we explored the behavioral mechanisms underlying the direct and indirect mediation pathways. We estimated the effect of a simulated reduction in neighborhood deprivation index on smoking, physical activity, and dietary adherence and incorporated the impact of those subsequent behavioral changes on BMI.

Methods

Study Sample

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large, integrated health care delivery system caring for more than 3 million persons who are representative of the San Francisco Bay and Sacramento regional population.11 The DISTANCE survey was conducted during 2005-2006 in an ethnically stratified random sample of KPNC members in the diabetes registry (n = 40,735) with approximately equal samples sizes among the five largest ethnic groups (African American, Chinese, Filipino, Latino, and White). As described by Moffet et al. (2009), a total of 20,188 people responded to the survey for a response rate of 62% after adjusting for estimated eligibility among non-respondents.12 Respondents to the short-form survey (n = 2,393), individuals with type 1 diabetes (n = 826), and individuals with extreme BMI values above the 99th percentile or below the first percentile (n = 335) were excluded, leaving a final analytic sample of 16,634.

Outcome: BMI

BMI was calculated from electronic records using the first clinical measurement of height and weight recorded in an outpatient visit after the survey date. Self-reported weight and height from the survey was used (n = 1,226) if individuals had no measured weight and height within two years after the survey. BMI was inverse-transformed in regression models to approximate a normal distribution. In sensitivity analyses, we assessed the robustness of findings using alternative body mass outcomes including binary indicators of obesity (BMI≥30) and severe obesity (BMI≥35).

Exposure: Neighborhood deprivation

Neighborhood deprivation index was calculated based on 2000 US Census housing and population data. Eight census-derived variables comprising six domains (income, poverty, housing, education, employment, and occupation) were used to create the index using principal components analysis of 2,250 census tracts in the 19 counties with more than 25 DISTANCE respondents (Cronbach alpha = 0.93).3,13 We calculated neighborhood deprivation index quartiles (quartile 1 = least deprived; quartile 4 = most deprived), and assigned quartile values to respondents at the census tract level based on 2006 home address data.

Mediator: Healthy and unhealthy food vendor density

Healthful food vendor density was defined as the kernel density of chain supermarkets (including wholesale clubs), large grocery stores (>$2 million in sales), and produce outlets at the census block centroid of each respondent's 2006 residence. Unhealthful food vendor density was defined as the kernel density of fast food outlets and convenience stores at the same address. Vendor locations were obtained from the 2006 InfoUSA commercial food store database as distributed through ESRI Inc.,14 and food stores were classified by Standard Industrial Codes (SIC) as well as by key word, chain name recognition, and annual sales. ArcGIS 10.115 (ESRI, Redlands, CA) was used to transform the geocoded vendor locations into a smooth kernel density surface using a 1-mile radius buffer and a quadratic function for inverse distance weighting. Quartiles of kernel density surface scores were used in the analysis. The first quartile represents the smallest and the fourth quartile represents the greatest kernel density of food vendors.

Intermediate health behaviors

We accounted for the effect of a simulated neighborhood deprivation index reduction on intermediate health behaviors (current smoking status, physical activity, and diet adherence) on the theorized causal pathway from neighborhood deprivation index to BMI. Current smokers (yes vs. no) were members who reported having ever smoked 100 cigarettes and currently smoking at the survey date. Physical activity (sufficiently active vs. inactive) was measured using the brief version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire.16 Diet adherence, a potential mediator of the pathway between food vendor density and BMI, was assessed by two items. Subjects were asked 1) “On how many days out of the last SEVEN DAYS have you followed a healthful eating plan?” and 2) “On average, over the past month, on how many DAYS PER WEEK have you followed your eating plan?” Responses from the two survey items were averaged, and diet adherence was dichotomized as good (≥ 5 days) vs. poor (< 5 days).

Covariates

Age and sex were collected from KPNC administrative data as of the date of survey completion. Census tract residential density was obtained from the 2000 Census and included in regression analyses as quartile indicator variables.17 Other covariates derived from survey responses include: race/ethnicity, marital status, nativity, household size, education, employment status, value of assets, income-to-federal-poverty-ratio, and diabetes-related locus of control. Given that diabetes-specific locus of control has been associated with self-care behavior,18 we included responses to two questions as proxies for health-related attitudes that may influence neighborhood preference. Locus of control was assessed by respondents’ levels of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with the statements: “What I do has a big effect on my health and I can avoid complications of diabetes” (internal locus of control) and “Good blood sugar control is a matter of luck and my blood sugars will be what they will be” (external locus of control). Both internal and external locus-of-control measures were dichotomized (≤3, >3).

Missing Data

Of the 16,634 respondents in the analytic sample, 7,796 were missing data on at least one of the above measures. Compared to respondents with complete data, respondents with missing data were more likely to be female, non-white, older, and foreign-born, and to have lower income and total years of education. Missing values were imputed using chained equations as described in eAppendix Table 1. Since standard errors were estimated using bootstrapping, a single stochastic imputation was drawn for each missing value in each iteration of the G-computation process.19

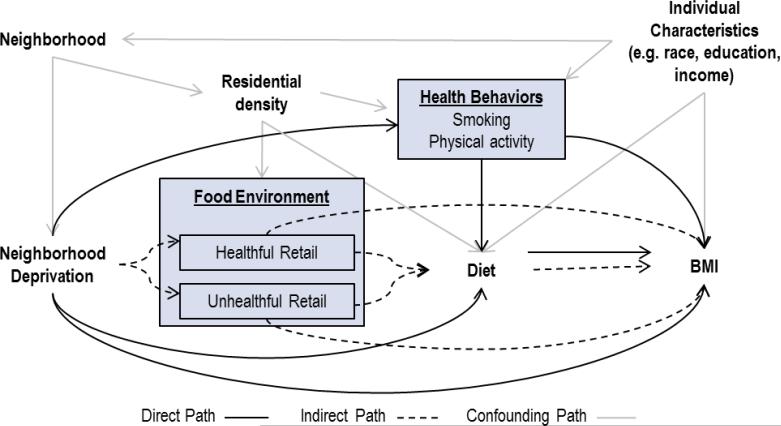

Causal graph

We developed a directed acyclic graph which makes explicit our assumptions about the causal relationships between neighborhood deprivation index, healthful food vendor density, unhealthful food vendor density, smoking, physical activity, diet adherence, and BMI (Figure 1). In this graph, individuals choose their neighborhood of residence based on preferences, resource constraints, and personal characteristics. Neighborhood deprivation index and residential density are characteristics of the residential neighborhood, and these two factors affect healthful and unhealthful food vendor density as well as individual smoking and physical activity. Healthful and unhealthful food vendor density influences BMI directly and indirectly through diet adherence.

Figure 1.

Directed Acyclic Graph. Arrows 1 represent theorized causal relationships

The decomposition of the effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI into direct and indirect effects required adjustment for factors that confound the neighborhood deprivation index-food vendor, food vendor-BMI, and neighborhood deprivation index-BMI relationships. Thus, we adjusted for individual-level traits and residential density in all prediction models. We were also interested in decomposing the natural direct and indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI into subcomponent pathways that operate through diet adherence. Physical activity and smoking were potential confounders of the diet adherence and BMI relationship; however, these health behaviors were also descendants of the exposure and might mediate the direct effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI. Standard adjustment for physical activity and smoking could therefore block the direct effect of neighborhood deprivation index on the outcome. G-computation enabled us to adjust for exposure-dependent confounding by smoking and physical activity without blocking the direct path between neighborhood deprivation index and BMI. The application of G-computation to analyses involving exposure-dependent confounding, of which mediation is a special case, has been discussed previously.9,19–21 In brief, we estimated the counterfactual probabilities of smoking and physical activity under alternate neighborhood deprivation interventions. Then, to estimate counterfactual diet adherence and BMI values under hypothetical scenarios that intervene on neighborhood deprivation, we set physical activity and smoking to their respective counterfactual values under the specific neighborhood deprivation intervention.

Statistical Analysis

G-computation was used to estimate the total effect, the controlled direct effect, the natural direct effect, and the natural indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation index (A) on BMI using Stata, release 12 (College Station, TX).22–24 The neighborhood deprivation intervention settings correspond with a hypothetical reduction in neighborhood deprivation from the highest to the lowest quartile. First, we generated prediction models for BMI, healthful food vendor density, unhealthful food vendor density, smoking, and physical activity as a function of their respective variable inputs (eAppendix, Table 2). Bivariate interaction terms were included as covariates in prediction models if the terms were significant at the p<0.20 level. Model diagnostics were performed for all models to identify specification errors. This involved computing the generalized Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic25 for all logistic and multinomial logistic regression models, conducting specification link tests26 on all models, and visually examining the graph of model residuals against fitted values for BMI.

Next, we used prediction models to simulate counterfactual values for BMI and all variables that impact BMI under six intervention scenarios that differed by exposure and mediator assignment. We simulated counterfactual estimates sequentially such that the predicted probabilities of input variables were used in the prediction of successive outcomes. First, we estimated counterfactual probabilities for each healthful food vendor density quartile (H) and unhealthful food vendor density quartile (U) as well as smoking (S) and physical activity (P) under two exposure settings: 1) if the respondent lived in the least deprived neighborhood [i.e. setting A = 1: to obtain HA1, UA1, SA1, and PA1], and 2) if the respondent lived in the most deprived neighborhood [i.e. setting A = 4: to obtain HA4, UA4, SA4, and PA4]. Next, we simulated counterfactual diet adherence probabilities (D) and counterfactual BMI values (transformed back to original units) setting input variables to the counterfactual values outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Values for variable inputs in BMI prediction models under six intervention scenarios

| Scenario | Neighborhood Deprivation Index Quartile (A) | Smoking status (S) | Physical activity (P) | Healthful Vendor Density (H) | Unhealthful Vendor Density (U) | Diet Adherence (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1: Least Deprived | S A1 | P A1 | 4: Highest | 4: Highest | D(A = 1, S = SA1, P = PA1, H = 4, U = 4) |

| 2 | 4: Most Deprived | S A4 | P A4 | 4: Highest | 4: Highest | D(A = 4, S = SA4, P = PA4, H = 4, U = 4) |

| 3 | 1: Least Deprived | S A1 | P A1 | H A1 | U A1 | D(A = 1, S = SA1, P = PA1, H = HA1, U = UA1) |

| 4 | 1: Least Deprived | S A1 | P A1 | H A4 | U A4 | D(A = 1, S = SA1, P = PA1, H = HA4, U = UA4) |

| 5 | 4: Most Deprived | S A4 | P A4 | H A1 | U A1 | D(A = 4, S = SA4, P = PA4, H = HA1, U = UA1) |

| 6 | 4: Most Deprived | S A4 | P A4 | H A4 | U A4 | D(A = 4, S = SA4, P = PA4, H = HA4, U = UA4) |

The difference in counterfactual BMI values between scenarios 1 and 2 were used to estimate the controlled direct effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI, holding both healthful and unhealthful food vendor density variables at the highest quartile values. Counterfactual BMI values under scenarios 3, 4, 5, and 6 were used to calculate the total effect, natural direct effect and natural indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation on BMI.

Mediation Effect Parameters

Assuming that everyone lived in the most deprived neighborhood quartile at baseline, the mediation parameters represent the expected change in population average BMI under alternative neighborhood deprivation and food vendor density interventions. Mediation parameters were estimated as the differences in sample mean simulated BMI comparing the intervention scenarios presented above. Confidence intervals for all mediation effect estimates were obtained from three hundred bootstrap iterations of the G-computation procedure.

Controlled Direct Effect

The controlled direct effect represents the expected change in population average BMI due to decreasing neighborhood deprivation holding healthful and unhealthful food vendor densities constant at a specific value for all cohort members. Since controlled direct effect parameters are defined by the specific mediator value settings that are chosen, multiple parameter definitions exist. We estimated the controlled direct effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI, holding both healthful and unhealthful food vendor density at the highest quartile. This parameter is estimated by the mean difference in simulated BMI for scenario 1 versus scenario 2.

Natural Direct Effect

Similar to the controlled direct effect, the natural direct effect also estimates the expected change in population average BMI due to decreasing neighborhood deprivation, omitting the influence of food vendor density. However, food vendor density values were set to their counterfactual values under the least deprived neighborhood setting and these counterfactual values may differ between subjects. This parameter was estimated by the mean difference in simulated BMI for scenario 3 versus scenario 5.

Natural Indirect Effect

The natural indirect effect parameter of interest was estimated by the mean difference in simulated BMI for scenario 5 versus scenario 6. This parameter represents the expected change in population average BMI if we could set every study subject to his or her counterfactual food environment values under the least-deprived neighborhood quartile while holding neighborhood deprivation constant at the most deprived quartile.

Total Effect

The total effect (TE) of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI represents the combined effect of all direct and indirect causal pathways. It is estimated by the mean difference in simulated BMI for scenario 3 compared to scenario 6. It is also computationally equal to the sum of the natural indirect effect and the natural direct effect parameters above.

Other Component Effects

The natural direct and indirect effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI can be further decomposed into subcomponent pathways through intermediate behavioral outcomes. eAppendix Table 3 presents the definitions for these additional subcomponent effects. Each subcomponent effect was estimated as the difference in sample mean simulated values comparing counterfactual interventions that differ by neighborhood deprivation index, healthful food vendor density, and unhealthful food vendor density settings. The estimation process is analogous to the process described above for the estimation of the total effect, natural indirect effect, and natural direct effect.

Results

Table 2 presents selected socio-demographic and health characteristics by neighborhood deprivation index and food vendor density. The average BMI of this cohort was 31.7 kg/m2. BMI was higher in the most deprived neighborhoods (quartile 4) compared with the least deprived neighborhoods (quartile 1) (32.6 vs. 30.6 kg/m2). Higher BMI was also observed among residents with the lowest density (quartile 1) compared to the highest density (quartile 4) of healthful food vendors (31.7 vs 31.0 kg/m2).

Table 2.

Selected health and demographic characteristics by neighborhood deprivation index and food vendor density

| Neighborhood Deprivation |

Healthful Food Vendors |

Unhealthful Food Vendors |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall n=16,634 |

Q1: Lowest n=3,427 |

Q4: Highest n=3,689 |

Q1: Lowest n=4,148 |

Q4: Highest n=4,144 |

Q1: Lowest n=4,201 |

Q4: Highest n=4,159 |

|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.6 | 30.6 | 32.6 | 31.7 | 31.0 | 31.5 | 31.7 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30) | 51% | 46% | 58% | 54% | 47% | 51% | 52% |

| Severe Obese (BMI≥35) | 28% | 23% | 33% | 29% | 25% | 27% | 29% |

| Follow diet ≥5 days/wk | 59% | 68% | 55% | 61% | 59% | 62% | 59% |

| Physically active | 40% | 41% | 36% | 42% | 38% | 43% | 38% |

| Current smoker | 8.4% | 6.8% | 10% | 7.8% | 9.5% | 7.5% | 9.3% |

| Age | 58.6 | 59.2 | 58.4 | 58.5 | 58.6 | 58.8 | 58.5 |

| Percent male | 52% | 60% | 44% | 56% | 49% | 57% | 49% |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 23% | 31% | 13% | 31% | 17% | 31% | 20% |

| Black | 17% | 12% | 29% | 15% | 19% | 15% | 19% |

| Hispanic | 20% | 11% | 29% | 17% | 21% | 15% | 24% |

| Asian | 26% | 35% | 12% | 24% | 31% | 27% | 23% |

| Other/Mixed | 14% | 11% | 16% | 13% | 13% | 13% | 14% |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 17% | 9.0% | 26% | 14% | 19% | 13% | 20% |

| Completed high school or technical | 43% | 32% | 48% | 42% | 42% | 40% | 45% |

| Associates | 11% | 12% | 11% | 12% | 9.9% | 12% | 11% |

| Bachelors | 20% | 28% | 11% | 22% | 20% | 23% | 17% |

| Post-college | 9.5% | 19% | 3.8% | 11% | 9.4% | 12% | 7.5% |

| Married | 71% | 79% | 63% | 78% | 65% | 80% | 63% |

| Income (% of Federal Poverty Level) | |||||||

| <100% | 12% | 7.1% | 18% | 9.2% | 14% | 8.7% | 14% |

| 100-300% | 33% | 20% | 45% | 28% | 37% | 25% | 39% |

| 301-600% | 35% | 36% | 30% | 37% | 32% | 37% | 33% |

| 600%+ | 21% | 40% | 7.3% | 26% | 17% | 30% | 14% |

| Born in USA | 64% | 61% | 67% | 66% | 55% | 65% | 60% |

Table 3 presents the marginal mediation effect estimates obtained from G-computation. A reduction in neighborhood deprivation from the highest to the lowest quartile would be associated with an average change in BMI of −0.73 units (95% CI −1.05, −0.32). Analyses that used dichotomous outcome classifications (i.e. obesity and severe obesity) found similarly large total effect estimates. We found no evidence of mediation by healthful and unhealthful food vendor density. The simulated effect of lower deprivation on BMI through the healthful and unhealthful retail food pathway was an increase in average BMI of 0.01 (95% CI −0.06, 0.05) units. In sensitivity analyses, healthful and unhealthful food vendor density did not appear to mediate the association between neighborhood deprivation index and dichotomous obesity outcomes.

Table 3.

Marginal mediation effects of neighborhood deprivation reduction from highest to lowest quartile

| BMI (kg/m2) |

Obese* (BMI≥30) |

Severe obese* (BMI≥35) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Total Effecta | −0.73 | (−1.05, −0.32) | −5.0% | (−7.1, −2.0) | −5.0% | (−6.1, −1.3) |

| Controlled Direct Effectb | −0.71 | (−1.00, −0.32) | −4.7% | (−6.8, −1.5) | −4.6% | (−5.6, −0.90) |

| Natural Direct Effectc | −0.74 | (−1.06, −0.34) | −6.3% | (−7.0, −1.3) | −5.5% | (−6.8,−0.54) |

| Natural Indirect Effectd | 0.01 | (−0.06, 0.05) | 1.3% | (−0.51, 3.7) | 0.5% | (−2.1, 1.9) |

Mediation effects for obese and severe obese dichotomous outcomes are expressed as expected change in probability of event in absolute-scale percentage points.

Total Effect estimates the total effect of a NDI reduction (from highest to lowest quartile) on body mass outcomes.

Controlled Direct Effect estimates the effect of a NDI reduction (from highest to lowest quartile) on body mass outcomes holding healthful and unhealthful food vendor density constant at the highest quartile (H=4, U=4)

Natural Direct Effect estimates the effect of a NDI reduction (from highest to lowest quartile) on body mass outcomes, holding healthful and unhealthful food vendor density constant at their counterfactual values under the most affluent neighborhood setting (HA=1, UA=1).

Natural Indirect Effect estimates the effect of healthful and unhealthful food vendor density change (from HA=4 and UA=1 to HA=1 and UA=1) on body mass outcomes, holding neighborhood deprivation constant at the highest quartile.

The natural direct effect and natural indirect effect estimates were further decomposed into constituent subcomponent effects. Figure 2 depicts the simulated influence of neighborhood deprivation index on each intermediate behavioral outcome in the causal chain.

Figure 2.

Decomposition of natural direct and indirect effects. Neighborhood deprivation index was reduced from the most deprived (Qt 4) to least deprived (Qt 1) quartile. Dashed lines indicate path segments that contribute to the natural indirect effect

Unlike many studies that document a positive association between neighborhood affluence and healthful food vendor availability,27–29 in our analysis, a simulated reduction in neighborhood deprivation from the most deprived (quartile 4) to the least deprived quartile (quartile 1) was associated with dramatic declines in both healthful and unhealthful food vendor density. Based on prediction models, the probability of being in the highest quartiles of healthy food vendor density and unhealthy food vendor density would decline 7.2 percentage points (95% CI −11.7, −5.1 and 22.5 percentage points (95% CI: −25.9, −19.6), respectively, if neighborhood deprivation were reduced. The probability of being in the lowest quartiles of healthy food vendor density and unhealthy food vendor density would rise by 9.3 percentage points (95% CI 5.7, 11.6 and 19.3 percentage points (95% CI 17.1, 22.9), respectively, if neighborhood deprivation were reduced. The simulated reduction in neighborhood deprivation index and the resulting changes in healthful and unhealthful vendor density, smoking and physical activity did not appear to improve diet adherence. The total effect of reducing neighborhood deprivation from the highest to the lowest quartile would reduce the probability of diet adherence by 2.9 percentage points (95% CI: −1.4, 5.4).

Simulated BMI and obesity outcomes under the natural course (i.e. no intervention scenario) were comparable to observed outcomes across categories of the exposure and mediators (eAppendix, Table 4). Moreover, the magnitude of the deviation between simulated and observed outcome values did not differ across neighborhood deprivation index, healthful food vendor density, and unhealthful food vendor density mediator categories (not shown).

Discussion

In this multi-ethnic cohort of adults living with diabetes, we found a significant association between neighborhood deprivation and BMI using causal modeling methods that adjusted for a wide array of individual characteristics, but we found no evidence that variation in food vendor density mediated that relationship in our sample. Healthful and unhealthful food vendor density accounted for none of the total effect of neighborhood deprivation index on BMI, obesity, and severe obesity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the pathways through which neighborhood deprivation index may affect BMI and obesity using G-computation. Assuming that predictive models are correctly specified, G-computation can estimate natural mediation effect parameters in the presence of exposure-mediator interaction and sequential impacts on intermediate variables along the causal chain. Despite the advantages of using G-computation for mediation analyses and the availability of a statistical package for common mediation parameters (g-formula),19 few applications of this method have been published to date.30

In contrast to previous findings,27–29 greater neighborhood deprivation was associated with a higher density of all types of food vendors, healthful and unhealthful. This is not surprising in this study setting, however. Higher land values in more affluent neighborhoods may discourage construction of supermarkets in these residential areas. Moreover, residents are likely to value the residential feel and, through zoning, maintain a distance from centers of commerce. In addition, produce stores were clustered in neighborhoods with large immigrant populations (i.e. Chinatown, San Francisco), which were less affluent. As expected, unhealthful food venues also clustered in poorer neighborhoods, with the number of unhealthful food venues far outweighing the number of healthful food venues. The associations between food vendor density and neighborhood deprivation index persisted despite adjustment for population density, suggesting that other social forces influence the location of healthful and unhealthful food venues.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our study findings. DISTANCE survey respondents represent an insured, managed-care population of adults with type 2 diabetes in a largely urban area, and study results may not generalize to dissimilar populations. Also, given that this mediation analysis is based on cross-sectional data, there is no way to establish time ordering of the exposure, mediators, and outcome. Additionally, the validity of the G-computation estimator hinges on the validity of the predictive models used to create the simulated data. Misspecification of the predictive models, either by omission of confounding variables or miss-specification of functional form would lead to bias. We adjusted for a wide range of individual characteristics and beliefs that plausibly predict residential choice and store location, but these controls may not have been adequate. Moreover, diet adherence, smoking, physical activity, and personal socio-demographic characteristics were obtained from survey responses that may not reflect true values. Additionally, a handful of studies have documented both random and systematic error in vendor classification and identification in commercial databases obtained from marketing firms31–33 and mediator measurement error can induce bias in mediation effect estimates. Ground-truth verification of supermarket and produce store locations was not feasible given the extensive geographic scope of this study, but store type designations within the commercial list were cleaned and reclassified based on key word searches, name recognition, and annual sales data to improve accuracy.

Overall, retail food vendor density is a crude measure of neighborhood food availability and it is not, on its own, an appropriate measure for neighborhood food access.34–36 In addition to vendor proximity and density, within-store product variety, quality, price, and cultural relevance are important components of food accessibility that may more strongly influence individual food choice. Moreover, resident characteristics such as car-ownership or disability also affect the lived experience of accessing neighborhood food resources. None of these factors were measured in our study.

A related but separate concern that is common to current research on neighborhood health effects is that the exposure and mediator definitions used in analyses do not capture important distinctions in neighborhood environment. Two neighborhoods in the same healthy food vendor density quartile can have vastly different food environments in practice. Additionally, similar food environments can arise from very different underlying processes. For example, a greater density of healthful food vendors may be an unintentional consequence of land use and zoning changes. Alternatively, intentional policy interventions that subsidize food retail development in target neighborhoods may create a similar food environment.37 Thus, each value of neighborhood deprivation index or food vendor density may in fact represent multiple underlying “versions” of “treatment” that can have differential impact on BMI and this complicates the interpretation of mediation effect estimates.38,39

It is also worth noting that there is considerable debate about the policy relevance of natural direct and indirect effects since the intervention settings for the parameters cannot be defined in practice.40–42 Controlled direct effects, which estimate the magnitude of the exposure-outcome relationship that would remain under an intervention which sets the mediator to specific levels, has been proposed as a preferred alternative.40,41 However, only natural direct and indirect effects analyses can quantify the relative contribution of a mediation pathway in accounting for the total influence of an exposure on an outcome. In deference to each viewpoint, our study presented both controlled and natural direct effects estimates. We believe that both of these approaches can provide meaningful policy guidance and can help policy makers evaluate and prioritize among many policy options for addressing neighborhood disparities in chronic disease.

We found that neighborhood deprivation is strongly and independently associated with BMI and other weight outcomes, but there was no consistent evidence that these associations were mediated by neighborhood food vendor density in this sample of adults with diabetes. The identification of the specific neighborhood attributes that explain geographic variation in obesity risk in this population remains largely unexplained. Future investigations of the impact of the food vendor environment on diet-related outcomes should adopt a more nuanced exposure definition that makes a distinction between food product availability and retail outlet type. Despite the limitations, our methods and findings contribute to a growing literature which investigates how neighborhood deprivation translates into specific and potentially modifiable neighborhood factors that impact the daily existence of residents.

Supplementary Material

Data Access.

Survey data for the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) and clinical records are confidential and maintained by the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. For more information or to collaborate please contact Howard H. Moffett (MPH), howard.h.moffett@kp.org

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Maya Petersen for her statistical guidance. This study was supported by: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK-080744); “Ethnic disparities in diabetes complications” (PI Andrew Karter, R01 DK065664-01-A1); and “Neighborhood Effects on Weight Change and Diabetes Risk Factors (PI Barbara Laraia, R01 DK080744);

References

- 1.Roux AVD, Kershaw K, Lisabeth L. Neighborhoods and cardiovascular risk: Beyond individual-level risk factors. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk Rep. 2008;2(3):175–180. doi:10.1007/s12170-008-0033-0. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. doi:10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laraia BA, Karter AJ, Warton EM, Schillinger D, Moffet HH, Adler N. Place matters: neighborhood deprivation and cardiometabolic risk factors in the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(7):1082–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.036. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz S, Fabricatore AN, Diamond A. Weight reduction in diabetes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;771:438–458. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5441-0_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morland K, Diez Roux AV, Wing S. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006;30(4):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafson AA, Sharkey J, Samuel-Hodge CD, et al. Perceived and objective measures of the food store environment and the association with weight and diet among low-income women in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(06):1032–1038. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011000115. doi:10.1017/S1368980011000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beydoun MA, Powell LM, Chen X, Wang Y. Food Prices Are Associated with Dietary Quality, Fast Food Consumption, and Body Mass Index among U.S. Children and Adolescents. J. Nutr. 2011;141(2):304–311. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.132613. doi:10.3945/jn.110.132613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones-Smith JC, Karter AJ, Warton EM, et al. Obesity and the food environment: income and ethnicity differences among people with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2697–2705. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2190. doi:10.2337/dc12-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robins J. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period—application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Math. Model. 1986;7(9–12):1393–1512. doi:10.1016/0270-0255(86)90088-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snowden JM, Rose S, Mortimer KM. Implementation of G-Computation on a Simulated Data Set: Demonstration of a Causal Inference Technique. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):731–738. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq472. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon NP, Kaplan GA. Some evidence refuting the HMO “favorable selection” hypothesis: the case of Kaiser Permanente. Adv. Health Econ. Health Serv. Res. 1991;12:19–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moffet HH, Adler N, Schillinger D, et al. Cohort Profile: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE)--objectives and design of a survey follow-up study of social health disparities in a managed care population. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009;38(1):38–47. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn040. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2006;83(6):1041–1062. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. doi:10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ESRI [February 24, 2014]; Available at: http://www.esri.com/.

- 15.ArcGIS Desktop. Environmental Systems Research Institute; Redland, CA: 2012. [February 24, 2014]. Available at: http://gis.stackexchange.com/questions/5783/how-do-you-cite-arcgis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census Bureau. [February 24, 2014];2000 Census. 2012 Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html.

- 18.Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Structure and correlates of diabetes-specific locus of control. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(9):994–1001. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.9.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel RM, De Stavola BL, Cousens SN. gformula: Estimating causal effects in the presence of time-varying confounding or mediation using the g-computation formula. Stata J. 2011;11(4):479–517. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins JM, Hernán MA. Estimation of the Causal Effects of Time-Varying Exposures. In: Fitzmaurice G, Davidian M, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, editors. Crc Press-Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniel RM, Cousens SN, De Stavola BL, Kenward MG, Sterne JA. Methods for dealing with time-dependent confounding. Stat. Med. 2013;32(9):1584–1618. doi: 10.1002/sim.5686. doi:10.1002/sim.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen ML, Sinisi SE, van der Laan MJ. Estimation of direct causal effects. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass. 2006;17(3):276–284. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000208475.99429.2d. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000208475.99429.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass. 2009;20(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f69ce. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f69ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagerland M, Hosmer D. A generalized Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for multinomial logistic regression models. Stata J. 2012;12(3):447–453. [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Stata 12 Base Reference Manual. College Station, TX: 2011. Linktest. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Fruit and vegetable access differs by community racial composition and socioeconomic position in Detroit, Michigan. Ethn. Dis. 2006;16(1):275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev. Med. 2007;44(3):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.008. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Associations of neighborhood characteristics with the location and type of food stores. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96(2):325–331. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058040. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.058040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepage B, Dedieu D, Savy N, Lang T. Estimating controlled direct effects in the presence of intermediate confounding of the mediator–outcome relationship: Comparison of five different methods. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2012:0962280212461194. doi: 10.1177/0962280212461194. doi:10.1177/0962280212461194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoehner CM, Schootman M. Concordance of commercial data sources for neighborhood-effects studies. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2010;87(4):713–725. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9458-0. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9458-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auchincloss AH, Moore KAB, Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Improving retrospective characterization of the food environment for a large region in the United States during a historic time period. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1341–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.016. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell LM, Han E, Zenk SN, et al. Field validation of secondary commercial data sources on the retail food outlet environment in the U.S. Health Place. 2011;17(5):1122–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.010. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA, Lytle LA, Yaroch AL. Measures of the Food Environment: A Compilation of the Literature, 1990–2007. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;36(4, Supplement):S124–S133. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caspi CE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Adamkiewicz G, Sorensen G. The relationship between diet and perceived and objective access to supermarkets among low-income housing residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;75(7):1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.014. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, et al. Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: a methodological review. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1773–1785. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000753. doi:10.1017/S1368980010000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giang T, Karpyn A, Laurison HB, Hillier A, Perry RD. Closing the grocery gap in underserved communities: the creation of the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. JPHMP. 2008;14(3):272–279. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000316486.57512.bf. doi:10.1097/01.PHH.0000316486.57512.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VanderWeele TJ, Hernan MA. Causal inference under multiple versions of treatment. J. Causal Inference. 2013;1(1):1–20. doi: 10.1515/jci-2012-0002. doi:10.1515/jci-2012-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernán MA, VanderWeele TJ. Compound treatments and transportability of causal inference. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass. 2011;22(3):368–377. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182109296. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182109296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naimi AI, Kaufman JS, MacLehose RF. Mediation misgivings: ambiguous clinical and public health interpretations of natural direct and indirect effects. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1656–61. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu107. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman JS. Commentary: Gilding the black box. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009;38(3):845–847. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp163. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz S, Hafeman D, Campbell U, Gatto N. Author's Response: Gilding the Black Box. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010;39(5):1399–1401. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp323. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.