Abstract

This study investigated lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression and quality of life (QOL), and validated variable similarities between ever and never smokers. Patients took online self-report surveys. Variable contributions to QOL were investigated using hierarchical multiple regression.

Patients were primarily Caucasian females with smoking experience. Strong negative relationships emerged between QOL and anxiety, depression and lung cancer stigma. Lung cancer stigma provided significant explanation of the variance in QOL beyond covariates. No difference emerged between smoker groups for study variables. Stigma may play a role in predicting QOL. Interventions promoting social and psychological QOL may enhance stigma resistance skills.

Keywords: Lung cancer stigma, quality of life, lung cancer, psycho-oncology, depression, anxiety, patient experience

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in men and women in the United States (Siegel, Naishadham, & Jemal, 2012) and is associated with greater levels of psychological distress than any other cancer (Hewitt, Rowland, & Yancik, 2003; Schag, Ganz, Wing, Sim, & Lee, 1994).The association is especially problematic for long term lung cancer survivors (LTLCS), whose numbers are increasing due to prevention and treatment advances and who suffer prolonged distress as they live longer. This group is less likely to have ever smoked tobacco, which may result in more severe psychological outcomes, given that public perception of lung cancer assumes that all lung cancer patients were or are smokers and thus responsible for their disease (Janne et al., 2002; Sugimura & Yang, 2006).

As lung cancer patients enjoy increasing longevity, it is essential to understand their quality of life (QOL) (Jemal et al., 2009; Montazeri, Milroy, Hole, McEwen, & Gillis). Previous research suggests an association between higher QOL at time of diagnosis and increased life span (Ganz, Jack Lee, & Siau, 2006). Additionally, there is some evidence that successful treatment does not result in improved QOL (L. Sarna et al., 2010). Low QOL reported by LTLCS is not adequately explained by pre-cancer QOL, severity of lung cancer diagnosis, or treatment outcomes.

Anxiety and depression are associated with diminished QOL for lung cancer patients (Arrieta et al., 2012; L. Sarna et al., 2010; L. Sarna et al., 2002). One study found that anxiety significantly increased during chemotherapy and was associated with a decrease in QOL (Li, Wang, Xin, & Cao, 2012). Anxiety decreased at the conclusion of chemotherapy, but did not return to pre-chemotherapy levels (Li et al., 2012). Anxiety and depression are predictors of QOL, but do not explain the total variance in QOL (Hutter et al., 2012). Therefore, there must be additional factors that explain QOL variance among lung cancer patients; the potential role of stigma should not be underestimated.

Lung Cancer Stigma (LCS) is a perceived health-related stigma that results from negative perceptions about the causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer (Cataldo, Slaughter, Jahan, Pongquan, & Hwang, 2011). LCS contributes to the high distress levels of lung cancer patients and may help explain persistent low QOL for LTLCS. Previous research has shown LCS to be associated with higher depression and lower QOL (Cataldo, Jahan, & Pongquan, 2012), and higher anxiety and symptom burden (Cataldo & Brodsky, 2013). Additionally, regardless of smoking status (ever or never smoker), lung cancer patients report no differences in levels of LCS, QOL or distress (Cataldo et al., 2012).

Theoretical Framework

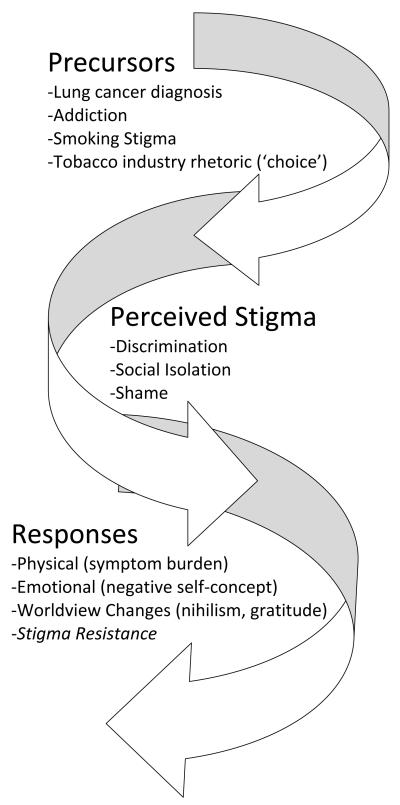

The theoretical framework for this study is the Lung Cancer Stigma Model (LCSM) (Brown & Cataldo, 2013; Cataldo, July 06, 2011). The LCSM was adapted from Berger’s HIV Stigma scale (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001) and was used to guide the development of the Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale (CLCSS) (Cataldo, July 06, 2011; Cataldo et al., 2011). The LCSM is a patient-centered model of LCS (Brown & Cataldo, 2013; Cataldo, July 06, 2011) that includes three potentially simultaneous stages of precursors, perception and responses to LCS (Figure 1). LCS, according to this model, is characterized by a diagnosis of lung cancer and connections to tobacco exposure and smoking stigma; experiences of discrimination, isolation or shame; and responses ranging from increased symptom burden to Stigma Resistance (SR).

The concept of SR was originally a subscale of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003) and was later defined as “opposition to the imposition of … stereotypes by others” (Thoits, 2011). It includes strategies that deflect or overtly challenge stigma (Thoits, 2011). One study among patients with schizophrenia found that high SR was positively correlated with higher self-esteem, empowerment and QOL, and negatively associated with more stigma and depression (Sibitz, Unger, Woppmann, Zidek, & Amering, 2011). In another sample, however, associations between SR and QOL were not observed (Tang & Wu, 2012). One prior study indicated that robust and stable social networks promote SR (Sibitz et al., 2011). Other theoretical but unexamined potential protective factors for SR include prior experience with SR, previous experience of the illness, symptoms that are less noticeable to others, high levels of psychosocial coping resources provided at initial diagnosis, and multiple role-identities (Thoits, 2011).

Lung cancer stigma

Regardless of smoking status, lung cancer patients have reported stigmatization from clinicians, family members and friends due to strong associations between smoking and lung disease (Chapple, Ziebland, & McPherson, 2004). Smokers have become increasingly socially marginalized (Stuber, Galea, & Link, 2008), and this marginalization extends to lung cancer patients. Individuals who have ever smoked have identified contributing factors of LCS related to smoking, including perceptions of smoking as a choice rather than an addiction, the discrimination experienced by smokers as the result of no-smoking policies, and public assumption that smokers are less educated (Stuber et al., 2008). LCS influences all lung cancer stakeholders, including patients and their families, caregivers, and health care providers. Its full impact and the mechanisms underlying its impact on patients are only beginning to be revealed and warrant further study.

Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, and depression

An investigation of patient-reported distress associated with 14 cancer diagnoses found that the prevalence of psychological distress varied by cancer type; lung cancer patients experienced the highest levels of distress (43.4%) (Zabora, BrintzenhofeSzoc, Curbow, Hooker, & Piantadosi, 2001). Carlsen and colleagues (2005) concluded that lung cancer patients are at high risk for psychosocial problems during and after treatment (Carlsen, Jensen, Jacobsen, Krasnik, & Johansen, 2005). One in four persons with lung cancer experiences periods of depression or other psychosocial problems during their treatment (Carlsen et al., 2005), and anxiety and depression increase during the course of the disease from baseline levels (Montazeri et al., 2001). In one study, at the time of diagnosis 23% of lung cancer patients were depressed and 16% were anxious. After three months the percentage almost doubled, when 44% reported depressive symptoms (Montazeri et al., 2001). Similarly, a United Kingdom study found the prevalence of anxiety and depression to be 43% among patients with small cell lung cancer (Hopwood & Stephens, 2000). Gonzalez (2012) found a positive association between perceived stigma and depression among lung cancer patients (Gonzalez & Jacobsen, 2012). In previous work, regardless of whether or not a person with lung cancer had ever smoked, LCS had a strong positive association with depression and a strong inverse association with QOL (Cataldo et al., 2012).

Lung cancer stigma and quality of life

QOL has been established as an independent predictor of survival for cancer patients (Ganz et al., 2006). Previous studies of lung cancer and QOL for women suggested strong associations between prognosis, depression and significant decreases in QOL (Linda Sarna et al., 2005). Sexual dysfunction and family disruption played the most important roles in decreasing QOL in this sample (Linda Sarna et al., 2005). QOL has been studied to determine the best possible treatment options for lung cancer patients who may experience severe changes in lifestyle and increased pain after lung cancer surgery. Reports differ as to whether lung cancer surgery causes continued deterioration of QOL or eventually allows for return to baseline QOL levels (Balduyck, Hendriks, Sardari Nia, Lauwers, & Van Schil, 2009). Demographic and clinical characteristics of lung cancer patients that influence QOL have been investigated; results are inconclusive. One study of the impact of marital status on QOL and longevity showed no difference in QOL overall, but noted that married and widowed patients reported greater spirituality and social support, both of which may affect QOL (Jatoi et al., 2007).

Study Aims and Hypotheses

This study seeks to replicate previous findings of associations among anxiety, depression, LCS, and QOL in a new sample. Additionally, these analyses will explore differences in these relationships by smoking status.

The specific aims for this study were to: 1) Investigate the relationship of LCS with anxiety, depression and QOL; 2) Explore whether LCS has a unique contribution to the explanation of QOL after controlling for significant covariates (i.e., sex, age); 3) Compare whether study variables vary by smoking status. Three hypotheses were tested. H1: There will be a positive relationship between LCS, anxiety, and depression, and an inverse relationship with QOL among lung cancer patients. H2: LCS will have a unique and significant contribution to QOL after controlling for covariates. H3: There will be no difference by ever or never smoking status.

Methods and Design

This descriptive cross-sectional study, with a correlational design, evaluated the relationships among anxiety, depression, LCS, and QOL. IRB approval was received from the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research. Methods and design have been previously described in Cataldo et al. (2011) and Cataldo and Brodsky (2013). Briefly, online recruitment via the study’s homepage and web sites frequented by potential study participants, including http://www.LUNGevity.org/, http://supportgroups.cancercare.org/, etc. produced participants who completed questionnaires. The posting included a study introduction to the study, a pledge of anonymity, the Primary Investigator’s contact information, and a link to the questionnaires. Data were securely collected in a spreadsheet format and remained anonymous with no information linking questionnaires to participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Measures

Cataldo Lung Cancer Stigma Scale (CLCSS)

In our prior work, the CLCSS was found to be a valid and reliable measure in two diverse samples of lung cancer patients (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97 and 0.96, respectively) (Cataldo et al., 2012; Cataldo et al., 2011). Construct validity was supported by expected relationships with related constructs: self-esteem, depression, social support, and social conflict. The CLCSS consists of 31 items; each item is rated on a four-point Likert-type scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree), with higher values indicating greater agreement with the item. For this study the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96. High alphas may indicate that aspects of this measure are redundant; this was not deemed problematic for this study, since we were primarily interested in how LCS interacted with other measures. Future work for this scale, however, may include further factor analysis to reduce the number of items, and thus reduce redundancies.

Spielberger State Anxiety Questionnaire

The Spielberger State Anxiety Questionnaire is a 20-item scale that evaluates the emotional responses of worry, nervousness, tension, and feelings of apprehension related to how people feel “right now” in a stressful situation and is expected to correlate negatively with stigma. This scale asks participants to rate their emotional response intensity on a 4-point scale (1=not at all, 2=somewhat, 3=moderately so, and 4=very much so). The scores for each of the items are summed and the total score can range from 20 to 80. Construct validity was determined by testing participants under stressful and nonstressful conditions. Anxiety scores increased as the experimental stress conditions increased. In a study of oncology outpatients, the Cronbach’s alpha=0.94 (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Suchene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). For this study the Cronbach’s alpha =0.96.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D)

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) is a 20-item scale that is expected to correlate negatively with stigma. The CES-D is a valid and reliable tool that has been widely used for self-ratings of depression in clinical populations, including people with cancer and people with HIV/AIDS (Hoover et al., 1993). Participants respond on a 4-point scale (0-3), yielding total scores 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater depression. For this study the Cronbach’s alpha=0.93.

The Quality of Life Inventory

Developed by Ferrell and colleagues (1989), this 33-item instrument measures four dimensions of QOL in cancer patients, which also serve as subscales of the tool (i.e., social well-being, psychological well-being, physical well-being and spiritual well-being). The scale was expected to correlate negatively with LCS. Participants responded to each item on the QOL inventory by choosing a number from 0 (not at all positive) to 10 (extremely positive). Subscale scores and a total QOL score were calculated. The reliability of this tool was determined to be 0.94 in a sample of 435 patients undergoing treatment for cancer (Miaskowski & Dibble, Unpublished data). This tool has been tested for content validity using a panel of experts in oncology and pain management. The content validity index was 0.90. Construct and concurrent validity were reported (Ferrell, Wisdom, & Wenzl, 1989). The Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.94.

Data Analysis

Univariate analyses (i.e., descriptives and frequencies) were performed for all variables. Correlational analyses were performed to examine the bivariate relationships between sex, age, smoking status, anxiety, depression, LCS and QOL. After controlling for significant demographic covariates, hierarchical multiple regression was performed to investigate the individual contributions of anxiety, depression and LCS to the variance of QOL. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Sample

Participants (n=149 unless otherwise specified) ranged in age from 23 to 79 years (=56.8 years), 76% were partnered (n=146), and the vast majority of the participants were Caucasian (93.3%) (n=146). Nearly eighty percent of the sample reported current or prior smoking (“ever smokers”) (n=148); 53% met the CES-D criteria for depression (i.e., total score>16). Nearly 25% were men and almost 92% had 12 years of education or greater (n=148) (Table 1). The skew of this sample (younger and more female than typical lung cancer patients) may be an artifact of online recruitment, though to date there is only anecdotal data that cancer patients using online support systems tend to be younger or more female.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Demographics and Health Status

| Characteristics | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) (n=149) | 56.81 | 11.02 | 23-79 |

| Years of Education (n=148) |

14.59 | 4.22 | 2-26 |

|

| |||

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|

| |||

| Race (n=146) | |||

|

| |||

| Caucasian | 139 | 93.3 | |

|

| |||

| Non-Caucasian | 10 | 6.6 | |

|

| |||

| Sex (n=149) | |||

|

| |||

| Male | 37 | 24.8 | |

|

| |||

| Female | 112 | 75.2 | |

|

| |||

| Marital Status (n=146) | |||

|

| |||

| Married/Living with intimate partner |

111 | 76.0 | |

|

| |||

| Widowed, separated, divorced, never married |

35 | 24.0 | |

|

| |||

|

Currently Employed

(n=148) |

67 | 45.3 | |

|

| |||

|

Depressed Mood

(n=149) |

|||

|

| |||

| ≥16 (CES-D Score) | 80 | 53.7 | |

|

| |||

|

Smoking Status

(n=148) |

|||

|

| |||

| Ever (>100 cigs/life) | 118 | 79.7 | |

|

| |||

| Never | 30 | 20.3 | |

LCS, anxiety, depression, and QOL

The means, standard deviations, and ranges for the study variables are given in Table 2. The participants reported a mean stigma level of 75.9 (SD=18.2), possible range=31-124. The mean anxiety level reported was 43.1 (SD=14.9), possible range=20-80. The cut-off score for a diagnosis of depression is total score >16; mean CES-D depression score for the total sample was 19.4 (SD=13.1). QOL total score mean was 5.6 (SD=1.7), possible range 1-10.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Lung Cancer Stigma, Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life

| Instrument | SD | Range | Possible Range |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lung Cancer Stigma (LCS)

(n=149) |

75.85 | 18.20 | 34-121 | 31-121 |

| Anxiety (n=149) | 43.14 | 14.91 | 20-78 | 20-80 |

| Depression CES-D (n=149) | 19.40 | 13.14 | 0-60 | 0-60 |

|

Quality of Life (QOL)

(n=149) |

5.61 | 1.72 | 1.66-9.39 | 0-10 |

| Physical Well Being (n=149) |

6.28 | 2.44 | 0-10 | 0-10 |

| Psychological Well Being (n=148) |

5.55 | 1.76 | 1.39-9.50 | 0-10 |

| Social Well Being (n=149) |

5.10 | 2.35 | 0-10 | 0-10 |

| Spiritual Well Being (n=149) |

5.62 | 2.16 | 0.71-10 | 0-10 |

A higher score indicates increased Quality of Life, Stigma, Anxiety, and Depression

Among QOL subscales (possible range=1-10; higher indicates better QOL), physical well-being was reported as most positive, with a mean score of 6.28 (SD=2.44). The mean psychological well-being score (n=148) was 5.55 (SD=1.76); the mean social well-being score was 5.10 (SD=2.35) and the mean spiritual well-being score was 5.62 (SD=2.16) (Table 2).

Hypotheses

The results supported all three hypotheses. For hypothesis one, there were significant negative relationships between QOL and anxiety and depression and a significant negative relationship between LCS and total QOL. The results in Table 3 reveal strong Pearson product-moment correlations in the expected directions for QOL, anxiety, depression and LCS. Additionally, significant associations were found for LCS and three of the four QOL subscales (physical, psychological and social well-being). No significant association was established between QOL spiritual well-being and LCS.

Table 3.

Pearson Product Moment Correlations for LCS, Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life and Smoking Status (N=149)

|

ALL

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale |

Lung Cancer

Stigma (LCS) |

Anxiety | Depression |

Smoking

Status |

| Lung Cancer Stigma (LCS) |

--- | --- | --- | .018 |

| Anxiety | 0.418** | --- | --- | .057 |

| Depression (CESD) | 0.562** | 0.799** | --- | .148 |

| Quality of Life (Total) | −0.529** | −0.754** | −0.816** | −.059 |

| Physical Well Being (n=149) |

−0.452** | |||

| Psychological Well Being (n=148) |

−0.545** | |||

| Social Well Being (n=149) |

−0.551** | |||

| Spiritual Well Being (n=149) |

−0.058 | |||

p<0.001

The second hypothesis, that LCS would have a significant and unique role in explaining QOL after controlling for significant covariates, was also supported. After accounting for these covariates, determined to be sex, age, anxiety and depression, LCS made a significant and unique contribution to the explanation of QOL by 1.2% (p=.015) (Table 4). A final hierarchical multiple regression with five independent variables revealed an overall model that explained 71.5% of the total variance of QOL (F5,143=71.61, p<.001, Table 4).

Table 4.

Simultaneous Multiple Regression Summary Table: The effect of Lung Cancer Stigma on Quality of Life controlling for Sex, Age, Anxiety, and Depression (N=149)

| Source | R 2 | R2 change |

df | F | beta | p significant F change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.715 | 5,143 | 71.61 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Model 1: Sex | 0.064 | 1,147 | 10.10 | 0.002 | ||

| Model 2: Sex and Age |

0.081 | 1,146 | 12.44 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 3: Sex, Age and Anxiety |

0.447 | 1,145 | 70.36 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 4: Sex, Age, Anxiety and Depression |

0.110 | 1,144 | 85.02 | <0.001 | ||

| Model 5: Sex, Age, Anxiety, Depression and Lung Cancer Stigma |

0.012 | 1,143 | 71.61 | 0.015 | ||

| Individual Variables in the final model: |

||||||

| Sex | −0.063 | 0.175 | ||||

| Age | −0.102 | 0.057 | ||||

| Anxiety | −0.274 | <0.001 | ||||

| Depression | −0.555 | <0.001 | ||||

| Lung Cancer Stigma | −0.136 | 0.015 | ||||

Lastly, this study confirmed previous findings that LCS, depression and QOL do not differ by smoking status (r=.018,p=.828 [LCS]; r=.148, p=.072 [depression]; r=−0.59, p=.48 [QOL]). These results suggest that anxiety does not differ by smoking status for lung cancer patients as well (r=.057, p=.493) (Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this study confirm our previous findings that LCS is positively correlated with anxiety and depression and negatively correlated with QOL. Importantly, LCS provides a unique and significant, albeit small, explanation of the variance in QOL. Additionally, this study substantiates previous findings that there are no differences in these relationships by smoking status. Both ever and never smokers’ experiences are similar with respect to anxiety, depression, LCS and QOL. This study expands the understanding of the role of LCS in the lung cancer patient experience by demonstrating an association between LCS and QOL above and beyond anxiety and depression. Although the prognostic outlook for lung cancer patients is improving, lung cancer has one of the poorer prognoses of all human malignancies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). This fact likely influences patient responses to the diagnosis, including increased anxiety and depression, with an associated decline in QOL.

In addition, as previously reported, regardless of smoking status LCS is associated with diminished QOL (Cataldo et al., 2012). Because lung cancer is widely viewed as a smoker’s disease, patients who have never smoked often experience the same stigmatization as smokers do, characterized by a feeling imparted from others that one’s disease was self-inflicted (Cataldo, July 06, 2011; Nrugham, Larsson, & Sund, 2008).

This work supports the LCS Model (Figure 1). LCS’s positive association with anxiety and depression and negative association with QOL are likely reflected in the experience of stigma through a) discrimination, b) social isolation, and c) shame. Decreased QOL associated with LCS is also consistent with physical and emotional responses to stigma that a patient may have, such as increased symptom burden and negative self-concept. These responses may be demonstrated by decreases in QOL as observed by lower scores on the QOL physical, psychological and social well-being subscales.

This study has several limitations. The sample is moderate in size and does not represent the U.S. lung cancer population. This sample was younger, with higher proportions of female and Caucasian respondents, than the overall patient population. Additionally, there is growing evidence that anxiety, depression, and LCS are related constructs (Cataldo et al., 2012); the multiple regression model used may have over-controlled for some underlying aspect of psychological health related to these three constructs as a result.

Although not yet investigated in the realm of lung cancer, these results suggest that SR and QOL may be related. Qualitative studies of other patient populations suggest patient strategies to resist stigma that could positively affect QOL, particularly psychological and social well-being. Seeking support, becoming educated about one’s illness, and making strategic choices about diagnosis disclosure are all strategies applicable to many lung cancer patients that may improve emotional health and promote healthy social functioning (Buseh & Stevens, 2006). Several prior studies have highlighted personal agency manifested through ownership of treatment plans, resistance to external definitions of right and wrong, and direct attacks on stigma and discrimination as helpful in resisting stigma (Riessman, 2000; Wright, 2012); studies have shown these strategies may also increase QOL (Orchowski, Untied, & Gidycz, 2013). None of these SR strategies have been thoroughly studied for lung cancer patients, though qualitative work has suggested their importance (Brown & Cataldo, 2013; Chapple et al., 2004). Future research must explore relationships between SR and QOL in the context of LCS, as SR may provide key elements for effective LCS intervention. Support groups for lung cancer patients, which may serve as an SR strategy, have been found effective to increase QOL and patient agency in this population (Coughlan, 2004). Research into the availability and role of support groups in the context of LCS may reveal effective SR strategies and new LCS intervention opportunities.

In conclusion, this study suggests that LCS plays a unique and important role in predicting QOL. These results indicate that, regardless of smoking status, lung cancer patients experience LCS, which is associated with anxiety, depression, and diminished QOL. Further research is needed with larger samples and over time to replicate these findings and understand relationships among anxiety, depression, LCS, QOL, and SR.

Clinical Implications

This investigation validates previous findings linking QOL and LCS, and demonstrates that LCS provides a unique explanatory contribution to the understanding of QOL for lung cancer patients, above and beyond depression, anxiety and demographic covariates. With this in mind, we would encourage providers working with lung cancer patients and their families to consider not only typical psychosocial aspects of the diagnosis (e.g., depression, anxiety and QOL), but also to attend to the level of LCS a patient may experience. Related to this, lung cancer stigma literature suggests a gap in the psychosocial care of lung cancer patients, since at present there is no stigma reduction intervention available for this population. While researchers test the efficacy of strategies proposed to mitigate LCS and improve QOL, providers working with this patient population could consider encouraging their patients to engage in the following potential stigma reduction behaviors: 1) educate themselves about their diagnosis, 2) critically evaluate their treatment plans, 3) attend support groups, and 4) advocate against stigma. Lastly, further investigation of the underlying mechanisms of lung cancer stigma and connections with other relevant psychosocial factors will allow for better development of LCS interventions, as well as incorporation of stigma reduction elements into pre-existing support structures.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-113710.

This research was supported in part by a grant from the California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program TRDRP #21XT-0063.

Contributor Information

Cati G. Brown, Stanford University, Stanford Prevention Research Center..

Jennifer Brodsky, University of California San Francisco School of Nursing, Department of Physiological Nursing..

Janine K. Cataldo, University of California San Francisco School of Nursing, Department of Physiological Nursing..

References

- Arrieta O, Angulo LP, Nunez-Valencia C, Dorantes-Gallareta Y, Macedo EO, Martinez-Lopez D, Onate-Ocana LF. Association of Depression and Anxiety on Quality of Life, Treatment Adherence, and Prognosis in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2793-5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balduyck B, Hendriks J, Sardari Nia P, Lauwers P, Van Schil P. Quality of life after lung cancer surgery: a review. [Review] Minerva Chirurgica. 2009;64(6):655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Evaluation Studies Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Cataldo J. Explorations of lung cancer stigma for female long-term survivors. Nursing Inquiry. 2013 doi: 10.1111/nin.12024. doi: 10.1111/nin.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buseh AG, Stevens PE. Constrained but not determined by stigma: Resistance by African American women living with HIV. Women & Health. 2006;44(3):1–18. doi: 10.1300/J013v44n03_01. doi: Doi 10.1300/J013v44n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen K, Jensen AB, Jacobsen E, Krasnik M, Johansen C. Psychosocial aspects of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;47(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo JK. Lung cancer stigma and symptom burden. Paper presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer; Amsterdam, Netherlands. Jul 06, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo JK, Brodsky JL. Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression and symptom severity. Oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1159/000350834. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo JK, Jahan TM, Pongquan VL. Lung cancer stigma, depression, and quality of life among ever and never smokers. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(3):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo JK, Slaughter R, Jahan TM, Pongquan VL, Hwang WJ. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: psychometric testing of the cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(1):E46–54. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) 1999-2008 Cancer Incidence and Mortality Data National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7454):1470–1473. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan R. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer - Health promotion and support groups have a role. British Medical Journal. 2004;329(7462):402–403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7462.402-b. doi: DOI 10.1136/bmj.329.7462.402-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989;63(11):2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Jack Lee J, Siau J. Quality of life assessment. An independent prognostic variable for survival in lung cancer. Cancer. 2006;67(12):3131–3135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910615)67:12<3131::aid-cncr2820671232>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez BD, Jacobsen PB. Depression in lung cancer patients: the role of perceived stigma. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21(3):239–246. doi: 10.1002/pon.1882. doi: 10.1002/pon.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological and Medical Sciences. 2003;58(1):82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover DR, Saah AJ, Bacellar H, Murphy R, Visscher B, Anderson R, Kaslow RA. Signs and symptoms of “asymptomatic” HIV-1 infection in homosexual men. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. [Multicenter Study Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1993;6(1):66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(4):893–903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter N, Vogel B, Alexander T, Baumeister H, Helmes A, Bengel J. Are depression and anxiety determinants or indicators of quality of life in breast cancer patients? Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.736624. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.736624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janne PA, Freidlin B, Saxman S, Johnson DH, Livingston RB, Shepherd FA, Johnson BE. Twenty-five years of clinical research for patients with limited-stage small cell lung carcinoma in North America. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1528–1538. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatoi A, Novotny P, Cassivi S, Clark MM, Midthun D, Patten CA, Yang P. Does marital status impact survival and quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer? Observations from the mayo clinic lung cancer cohort. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] Oncologist. 2007;12(12):1456–1463. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1456. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Wang Y, Xin S, Cao J. Changes in quality of life and anxiety of lung cancer patients who underwent chemotherapy] Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2012;15(8):465–470. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2012.08.03. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2012.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Dibble S. Oncology outpatient pain: Incidence and morbidity paramaters. (Unpublished data)

- Montazeri A, Milroy R, Hole D, McEwen J, Gillis CR. Quality of life in lung cancer patients: as an important prognostic factor. Lung Cancer. 2001;31(2-3):233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nrugham L, Larsson B, Sund AM. Predictors of suicidal acts across adolescence: influences of familial, peer and individual factors. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;109(1-2):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski LM, Untied AS, Gidycz CA. Social reactions to disclosure of sexual victimization and adjustment among survivors of sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0886260512471085. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Stigma and everyday resistance practices - Childless women in South India. Gender & Society. 2000;14(1):111–135. doi: Doi 10.1177/089124300014001007. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121(1):31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. doi: DOI 10.1016/j.physchres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Brown JK, Cooley ME, Williams RD, Chernecky C, Padilla G, Danao LL. Quality of life and meaning of illness of women with lung cancer. Paper presented at the Oncology nursing forum; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Cooley ME, Brown JK, Chernecky C, Padilla G, Danao L, Elashoff D. Women with lung cancer: quality of life after thoracotomy: a 6-month prospective study. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Cancer Nursing. 2010;33(2):85–92. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181be5e51. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181be5e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Padilla G, Holmes C, Tashkin D, Brecht ML, Evangelista L. Quality of life of long-term survivors of non-small-cell lung cancer. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(13):2920–2929. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schag CAC, Ganz PA, Wing DS, Sim MS, Lee JJ. Quality of life in adult survivors of lung, colon and prostate cancer. Quality of Life Research. 1994;3(2):127–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00435256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibitz I, Unger A, Woppmann A, Zidek T, Amering M. Stigma Resistance in Patients With Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37(2):316–323. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp048. doi: DOI 10.1093/schbul/sbp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Suchene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the state-anxiety inventory (formy): self-evaluation questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Galea S, Link BG. Smoking and the emergence of a stigmatized social status. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura H, Yang P. Long-term survivorship in lung cancer: a review. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. Chest. 2006;129(4):1088–1097. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.4.1088. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.4.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang IC, Wu HC. Quality of Life and Self-Stigma in Individuals with Schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2012;83(4):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9218-2. doi: DOI 10.1007/s11126-012-9218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Resisting the Stigma of Mental Illness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2011;74(1):6–28. doi: Doi 10.1177/0190272511398019. [Google Scholar]

- Wright AG. Social Defeat in Recovery-Oriented Supported Housing: Moral Experience, Stigma, and Ideological Resistance. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry. 2012;36(4):660–678. doi: 10.1007/s11013-012-9280-0. doi: DOI 10.1007/s11013-012-9280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]