Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Cigarette smoking leads to upregulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the human brain, including the common α4β2* nAChR subtype. While subjective aspects of tobacco dependence have been extensively examined as predictors of quitting smoking with treatment, no studies to our knowledge have yet reported the relationship between the extent of pretreatment upregulation of nAChRs and smoking cessation.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether the degree of nAChR upregulation in smokers predicts quitting with a standard course of treatment.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Eighty-one tobacco-dependent cigarette smokers (volunteer sample) underwent positron emission tomographic (PET) scanning of the brain with the radiotracer 2-FA followed by 10 weeks of double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment with nicotine patch (random assignment). Pretreatment specific binding volume of distribution (VS/fP) on PET images (a value that is proportional to α4β2* nAChR availability) was determined for 8 brain regions of interest, and participant-reported ratings of nicotine dependence, craving, and self-efficacy were collected. Relationships between these pretreatment measures, treatment type, and outcome were then determined. The study took place at academic PET and clinical research centers.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Posttreatment quit status after treatment, defined as a participant report of 7 or more days of continuous abstinence and an exhaled carbon monoxide level of 3 ppm or less.

RESULTS

Smokers with lower pretreatment VS/fP values (a potential marker of less severe nAChR upregulation) across all brain regions studied were more likely to quit smoking (multivariate analysis of covariance, F8,69 = 4.5; P < .001), regardless of treatment group assignment. Furthermore, pretreatment average VS/fP values provided additional predictive power for likelihood of quitting beyond the self-report measures (stepwise binary logistic regression, likelihood ratio ; P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Smokers with less upregulation of available α4β2* nAChRs have a greater likelihood of quitting with treatment than smokers with more upregulation. In addition, the biological marker studied here provided additional predictive power beyond subjectively rated measures known to be associated with smoking cessation outcome. While the costly, time-consuming PET procedure used here is not likely to be used clinically, simpler methods for examining α4β2* nAChR upregulation could be tested and applied in the future to help determine which smokers need more intensive and/or lengthier treatment.

While the health risks1,2 and societal costs3–5 of cigarette smoking are well documented, the prevalence of smoking among adults in the United States remains high at approximately 20%.6,7 Although most smokers endorse a desire to quit,8 very few (<5%) will do so in a given year without treatment, and only about 20% to 25% will achieve abstinence even with 6 months or more of gold-standard treatment.9–14 Therefore, there continues to be a vital need to improve outcomes for cigarette smokers seeking treatment.15

Prior research examining prediction of response to smoking cessation treatments has focused primarily on clinical variables, with the most commonly reported predictors of outcome being levels of nicotine dependence,16–21 craving,22,23 and self-efficacy.24–28 Greater severity of nicotine dependence has been associated with poorer treatment outcome for nicotine patch,16,21 bupropion hydrochloride,18,19 and group psychotherapy20 as well as in naturalistic settings with no specific treatment.17 Similarly, low craving22,23 and high self-efficacy24–28 (self-confidence) have been repeatedly demonstrated to be predictors of successful treatment outcome,27,29,30 especially in situations where smokers are at risk for relapse. Other factors, such as desire to quit,31 low negative affect,32 no history of depression,33 low anger,34 slow nicotine metabolism,35 absence of lapses during early treatment,36 and reduction in smoking over time,37 have also been found to predict a positive response to treatment. Thus, clinical factors have been extensively examined for their value in predicting response to smoking cessation treatments; however, to our knowledge, there are no published studies examining brain receptor availability as a predictor of smoking cessation outcome.

Upregulation of β2-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) is one of the most well-established effects of smoking on the brain. Recent studies using single-photon emission computed tomography (CT)38–40 and positron emission tomography (PET)41–43 have demonstrated significant up-regulation of these receptors in smokers compared with non-smokers in all brain regions studied other than the thalamus. These in vivo studies were an extension of much prior research, including human postmortem brain tissue studies demonstrating that long-term smokers have increased nAChR density compared with nonsmokers and former smokers.44,45 Additionally, many studies of laboratory animals have demonstrated upregulation of markers of nAChR density in response to long-term nicotine administration.46–50

For this study, we sought to determine whether the degree of pretreatment α4β2* nAChR upregulation in cigarette smokers is associated with smoking cessation outcomes with a standard nicotine patch taper. In a smaller prior PET study by our group,51 we found possible associations that did not reach statistical significance between lower levels of a PET marker for α4β2* nAChR availability and improved outcome across 3 smoking cessation treatment groups. Therefore, we hypothesized that smokers with less pretreatment upregulation of available α4β2* nAChRs would have a greater likelihood of quitting smoking with the nicotine patch taper than smokers with more upregulation. We also sought to determine whether pretreatment α4β2* nAChR availability provided additional predictive power beyond previously reported clinical predictors (severity of nicotine dependence,16–21 craving,22,23 and self-efficacy24–27).

Methods

Participants and Screening Methods

Eighty-one treatment-seeking adult smokers completed the study and had usable data. These participants underwent a baseline screening visit, rating scale administration, pretreatment PET/CT scanning with the radiotracer 2-FA (for labeling α4β2* nAChRs), and double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment with nicotine patch taper (see eFigure in Supplement for details of numbers of screening failures and attrition).

Participants were recruited using the same methods as in prior reports,41,51 with the central inclusion criteria being tobacco dependence at the time of study initiation, smoking 10 to 40 cigarettes per day, and general good health. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, use of a medication or presence of a medical condition that might affect the brain at the time of scanning, or any history of an Axis I mental illness or substance abuse or dependence.

During the baseline screening visit, rating scales were administered to verify participant reports and characterize smoking history, which included the Smoker’s Profile Form (containing demographic variables and a detailed smoking history), Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND),52 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,53 Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale,54 and screening questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition, version 2.0.55 An exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) level was obtained (Micro-Smokerlyzer; Bedfont Scientific Ltd) to verify smoking status (CO ≥8 ppm). A breathalyzer test (AlcoMatePro), urine toxicology screen (Test Country I-Cup Urine Toxicology Kit), and urine pregnancy test (for women of childbearing potential; Test Country Cassette Urine Pregnancy Test) were performed to support the participant’s report of no current alcohol or drug dependence and no pregnancy. The study was approved by the institutional review board and radiation safety committee of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, and participants provided written informed consent.

Abstinence Period and PET Protocol

One week after the baseline screening session, participants underwent PET/CT scanning with the same abstinence and 2-FA bolus-plus-continuous-infusion PET/CT protocol as in our recent studies (see eAppendix in Supplement for details).41,51 Briefly, participants underwent 2 nights of smoking/nicotine abstinence, followed by a bolus-plus-continuous-infusion PET/CT session during which PET/CT data were collected for 3 hours following a 4-hour radiotracer uptake period. During the uptake period, the Urge to Smoke (UTS)56 craving scale (an analog scale with 10 craving-related questions rated 0–6) and Self-efficacy Rating Scale57,58 (ratings from 0–100) were administered.

Treatment for Cigarette Smoking

Within a week of PET/CT scanning, participants were randomly assigned59 to treatment with either active transdermal nicotine patches (Nicoderm CQ 24-hour patches; Cardinal Health Pharmaceuticals) or matching placebo patches (Rejuvenation Laboratories, Inc) in a manner similar to that of past research by our group60,61 and others.62,63 To maintain the double-blind design, patches were prepared by a research pharmacist and given to participants by a research assistant who was not involved in the participant’s treatment.

Participants met with a study physician (M.S.M. or A.L.B.) for an initial visit, were given nicotine or placebo patches, and were told of potential benefits and adverse effects64–66 of the nicotine patch. They were then seen weekly by a study physician for the remainder of the trial for 15-minute medication management visits, which consisted of assessment of adherence to the medication regimen, monitoring of smoking behavior,67–69 and evaluation of adverse effects. Participants assigned to the active patch group received a standard course of treatment beginning with 21-mg/d patches for 4 weeks followed by 14-mg/d patches for 2 weeks and 7-mg/d patches for 2 weeks, while the placebo patch group underwent an identical patch regimen without nicotine. Participants were encouraged to minimize or eliminate cigarette use when they initiated treatment and to choose a quit date 2 weeks after treatment initiation. If participants lapsed into smoking during treatment, they were encouraged to pick another quit date within the following week. After 8 weeks of patch treatment, participants were seen for study visits on 2 consecutive weeks (10 weeks total treatment). Although we recognize that combining medication with psychotherapy would have resulted in an enhanced smoking cessation rate,8,70,71 no formal psychotherapy was provided so that the relationship between pretreatment brain nAChR availability and nicotine or placebo patch response could be isolated.

At the final study visit, a participant report of 7 or more days of continuous abstinence from any tobacco use and an exhaled CO level of 3 ppm or less were used as criteria for having quit smoking. These criteria are similar to recent recommendations for documenting smoking abstinence72,73 and are comparable to criteria used in many treatment studies.9,13,35 Participants who initiated treatment but dropped out of the study were classified as nonquitters in accordance with recent recommendations72,74 and use75 of this classification. At the conclusion of the medication or placebo trial, all participants were offered open-label treatment with nicotine patch to assist in smoking cessation and to address (at least partly) ethical concerns76 about the use of placebo treatment in this study.

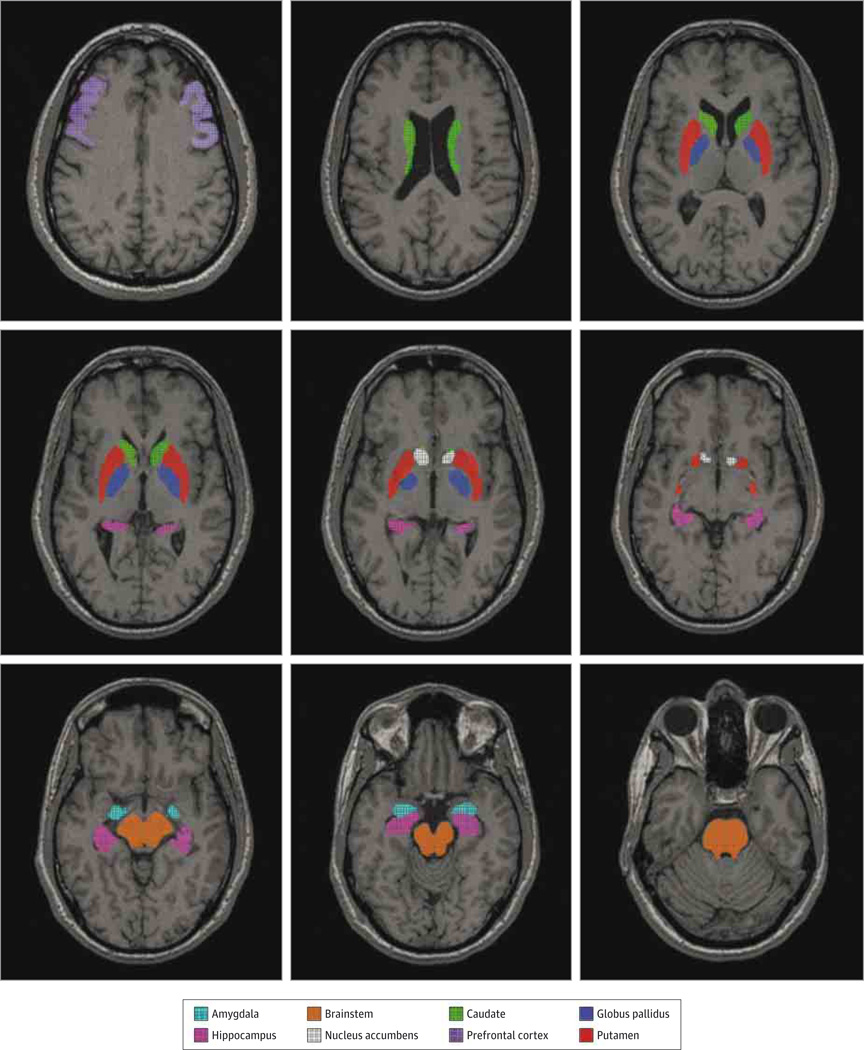

PET Image Analysis

After decay and motion correction, each participant’s PET/CT scan was coregistered to his or her magnetic resonance imaging scan using PMOD version 3.0 software (http://www.pmod.com/technologies). Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn on magnetic resonance images using PMOD and transferred to the coregistered PET (Figure 1). Most regions were delineated automatically using the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library program FIRST, which created automated drawings through model-based segmentation. These automated regions were generated from conditional probabilities based on shape and intensity77 from each participant’s magnetic resonance imaging scans and included the following regions bilaterally: nucleus accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, globus pallidus, and putamen. In addition, hand-drawn ROIs consisted of representative slices of the prefrontal cortex (middle frontal gyrus) bilaterally and the whole brainstem. These ROIs were chosen based on having arrange of nAChR densities, while the thalamus was specifically excluded from analysis because it is known not to have significant upregulation of α4β2* nAChRs in smokers. To preserve power, mean values of bilateral ROIs were used, so a total of 8 ROI values for each participant were used for statistical analysis. Placement of ROIs was visually inspected for each PET frame to minimize effects of coregistration errors and movement; ROI placement procedures were repeated if there was a noticeable problem.

Figure 1.

Study Regions of Interest Shown on a Representative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scan.

Specific binding volume of distribution (designated as VS/fP based on standard nomenclature78) was calculated for each ROI and used for all ROI-based analyses because this value is proportional to α4β2* nAChR availability (see eAppendix in Supplement for details of this calculation).

Statistical Analysis

Means and standard deviations were determined for demographic, rating scale, and smoking-related variables for the entire study sample and subgroups based on treatment type. Baseline data were compared between the nicotine and placebo patch subgroups using t tests for continuous data and Fisher exact tests for categorical data to confirm the success of randomization. For verifying the effect of treatment on smoking-related variables, repeated-measures analyses of variance were performed, with the smoking-related variables (cigarettes per day and exhaled CO levels) as repeated measures and treatment subgroup (nicotine vs placebo patch) as the between-subject factor.

To determine the relationship between α4β2*nAChR availability, treatment type, and quit status, an overall multivariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed using VS/fP values for the 8 ROIs as the measures of interest, subgroup (placebo or nicotine patch) and quit status as factors, and age as a nuisance covariate (based on prior research indicating that nAChR densities decline with age41,79,80).Follow-up ANCOVAS were performed for the ROIs separately with the same variables as in the overall multivariate ANCOVA. For descriptive purposes, mean VS/fP values for quitters and nonquitters were compared with available values from nonsmoking control participants in a previous study,41 and percentage of upregulation for these 2 groups was calculated.

For determining whether PET VS/fP data improve the ability to predict treatment response beyond self-report measures, binary logistic regression was used, as in prior studies.16,18,28,81 For this analysis, quit status was the outcome variable and pretreatment PET VS/fP values (mean of all ROIs based on the preceding analysis, which did not reveal regional differences), severity of nicotine dependence (FTND score), subjective UTS craving ratings, and self-efficacy ratings were the independent variables. To specifically determine whether the PET data provided additional predictive power beyond the well-studied measures, a stepwise logistic regression was performed with the 3 self-report measures entered first followed by the PET VS/fP data (along with the same analysis in reverse order). Statistical tests were performed using PASW/SPSS Statistics version 21.0 statistical software (SPSS, Inc).

Results

Baseline Demographic and Rating Scale Data

At baseline, the study sample was middle-aged, roughly half female, and approximately half white, with some college education and minimal anxiety and depressive symptoms (Table 1). Participants smoked roughly three-quarters of a pack of cigarettes per day and were moderately nicotine dependent. Study subgroups based on randomly assigned treatment type (n = 44 randomized to nicotine patch and n = 41 included in analysis resulting from quitters having lower pretreatment VS/fP values than nonquitters. In post hoc analyses of covariance, all of the individual regions of interest had significant associations with quit status (F1,80 = 10.4–24.9; P = .002 to <.001) but no significant interaction between treatment type and quit status. in nicotine patch subgroup; n = 44 randomized to placebo patch and n = 40 included in analysis in placebo patch subgroup) (eFigure in Supplement) did not differ on any demographic variables or rating scale scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Rating Scale, and Smoking-Related Variables for the Study Sample and Subgroups Randomly Assigned to Placebo or Nicotine Patch Treatment

| Variable | Study Sample (N = 81) |

Patch-Treated Subgroupa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 40) |

Nicotine (n = 41) |

||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 40.7 (12.6) | 42.7 (11.9) | 38.6 (13.1) |

| Female, No. (%) | 37 (45.7) | 18 (45.0) | 19 (46.3) |

| White, No. (%) | 39 (48.1) | 17 (42.5) | 22 (53.7) |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 14.5 (2.2) | 14.3 (2.2) | 14.8 (2.2) |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale score, mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.8) | 2.2 (2.1) | 2.8 (3.4) |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score, mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.9) | 2.3 (2.5) | 2.7 (3.2) |

| FTND score, mean (SD) | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.3 (2.2) |

| Longest quit period, mean (SD), y | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.7) |

| Cigarettes, No./d | |||

| Pretreatment | 15.4 (4.5) | 15.4 (4.7) | 15.3 (4.3) |

| Posttreatment | 6.8 (8.0)b | 7.5 (7.1)b | 6.3 (8.7)b |

| Change in cigarettes/d with treatment, mean (SD), % | −57.8 (43.6) | −52.7 (41.4) | −62.7 (45.6) |

| Exhaled CO, mean (SD), ppm | |||

| Pretreatment | 13.8 (6.3) | 14.5 (6.6) | 13.1 (6.0) |

| Posttreatment | 8.7 (7.2)b | 10.5 (7.8)b | 6.9 (6.2)b |

| Change in exhaled CO with treatment, mean (SD), % | −36.6 (42.7) | −28.7 (38.6) | −44.2 (45.5) |

| Smokers who quit with treatment, No. (%) | 20 (24.7) | 6 (15.0) | 14 (34.1)c |

Abbreviations: CO, carbon monoxide FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

No significant differences were found for baseline demographic or rating scale variables between smokers randomly assigned to the placebo vs nicotine patch treatment subgroups (t tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables).

P < .001 for within-group changes in cigarettes per day and exhaled CO from before to after treatment (paired t test).

P = .04 for difference between placebo and nicotine patch subgroups in percentage of quitters (Fisher exact test).

Effects of Treatment on Smoking-Related Variables

As expected, treatment was associated with a decrease for the entire study sample in number of cigarettes per day (mean [SD], −57.8% [43.6%]; F1,79 = 106.4; P < .001) and exhaled CO level (mean [SD], −36.6% [42.7%]; F1,79 = 44.0; P < .001). Subgroup × time interactions corresponding to differential change in cigarettes per day and exhaled CO level were not significant (F1,79 = 0.5, P = .50; and F1,79 = 2.2, P = .16, respectively), but the nicotine patch subgroup had greater numerical reductions in these measures than the placebo patch subgroup (Table 1). Twenty of the 81 participants met criteria for quitting smoking, and active nicotine patch treatment was associated with a higher percentage of quitters than placebo patch treatment (34.1% vs 15.0%, respectively; Fisher exact test, P = .04) (Table 1).

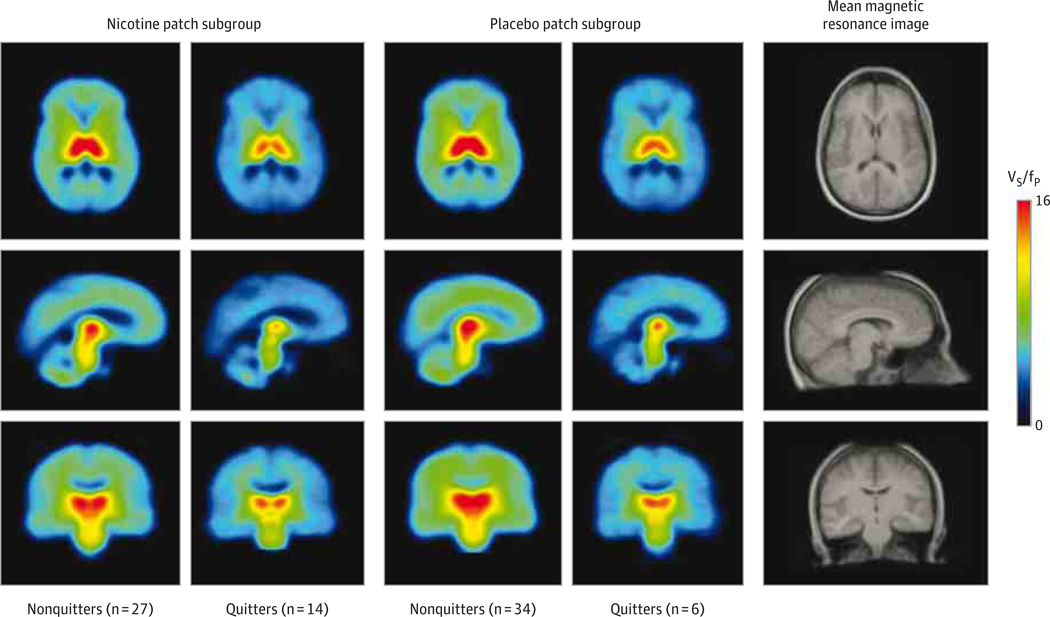

Pretreatment VSfP Values and Smoking Cessation

The overall multivariate ANCOVA revealed a significant main effect of quit status (F8,69 = 4.5; P < .001), resulting from quitters having lower pretreatment VS/fP values than nonquitters (Table 2 and Figure 2). In follow-up ANCOVAs, all ROIs had significant associations with quit status (F1,80 = 10.4–24.9; P = .002 to <.001), indicating that the relationship between pretreatment nAChR availability and quitting was not region specific. The interaction between treatment type and quit status was not significant (F8,69 = 0.8; P = .70), indicating that the relationship between pretreatment nAChR availability and quit status was not dependent on treatment type. For the brainstem and prefrontal cortex, quitters had means of 20% and 29% upregulation of nAChR availability, respectively, compared with available data from previously scanned nonsmoking control participants,41 while nonquitters had 66% and 80% upregulation in these respective regions.

Table 2.

Pretreatment Specific Binding Volume of Distribution for Brain Regions of Interest for Nonquitters and Quitters in the Total Study Group and the Placebo and Nicotine Patch Subgroups

| Brain Region | VS/fP, Mean (SD)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Group | Placebo Patch | Nicotine Patch | ||||

| Nonquitters (n = 61) |

Quitters (n = 20) |

Nonquitters (n = 34) |

Quitters (n = 6) |

Nonquitters (n = 27) |

Quitters (n = 14) |

|

| Amygdala | 5.5 (2.7) | 2.7 (1.2) | 5.9 (2.6) | 2.6 (1.2) | 5.0 (2.8) | 2.8 (1.3) |

| Brainstem | 10.9 (3.4) | 6.7 (1.9) | 11.5 (3.5) | 6.2 (1.7) | 10.1 (3.1) | 7.0 (2.0) |

| Caudate | 7.1 (2.4) | 5.2 (1.5) | 7.6 (2.6) | 4.7 (1.3) | 6.6 (2.1) | 5.5 (1.6) |

| Globus pallidus | 10.2 (3.4) | 6.0 (1.8) | 10.9 (3.4) | 5.6 (1.7) | 9.5 (3.3) | 6.1 (1.8) |

| Hippocampus | 6.7 (3.0) | 3.8 (1.3) | 7.2 (2.9) | 3.5 (1.4) | 6.1 (3.1) | 3.9 (1.3) |

| Nucleus accumbens | 7.7 (3.6) | 4.6 (1.8) | 8.1 (3.4) | 4.1 (1.3) | 7.2 (3.9) | 4.8 (2.0) |

| Putamen | 9.7 (3.6) | 5.9 (1.7) | 10.3 (3.5) | 5.4 (1.4) | 8.8 (3.6) | 6.1 (1.8) |

| Prefrontal cortex | 6.9 (3.3) | 4.0 (1.5) | 7.5 (3.0) | 3.6 (1.5) | 6.2 (3.5) | 4.2 (1.6) |

Abbreviation: Vs/fp , specific binding volume of distribution.

All values are presented as the mean of left and right regions of interest, where applicable. The overall multivariate analysis of covariance examining the relationship between pretreatment VS/fP values, treatment type, and quit status revealed a significant main effect of quit status (F8,69 = 4.5; P < .001), resulting from quitters having lower pretreatment VS/fP values than nonquitters. In post hoc analyses of covariance, all of the individual regions of interest had significant associations with quit status (F1,80 = 10.4–24.9; P = .002 to <.001) but no significant interaction between treatment type and quit status.

Figure 2.

Mean Pretreatment Positron Emission Tomographic Images From the Study Subgroups Demonstrating Higher 2-FA Binding at Baseline in Nonquitters Compared With Quitters

Mean pretreatment positron emission tomographic scans are shown for nonquitters and quitters treated with nicotine patch and for those treated with placebo patch. Positron emission tomographic images were spatially normalized to the group mean magnetic resonance imaging scan. VS/fP indicates specific binding volume of distribution.

Pretreatment Variables and Smoking Cessation

For the logistic regression analysis, the overall test was significant (; P < .001), indicating that the combination of PET and clinical factors has high value in predicting treatment outcome (Table 3). For the individual variables, pretreatment PET VS/fP values (P < .001), UTS craving scores (P = .003), and self-efficacy scores (P = .02) were all associated with quit status, while FTND score did not reach statistical significance (P = .25). In comparing respective mean values of these predictors, quitters compared with nonquitters had lower pretreatment PET VS/fP values (4.9 vs 8.1), lower UTS scores (2.2 vs 3.4), lower FTND scores (4.0 vs 4.6), and higher self-efficacy scores (60 vs 46). Furthermore, in the stepwise logistic regression, pretreatment PET VS/fP values provided additional predictive power beyond the self-report measures alone (for comparing the fit of the nested models: likelihood ratio ; P < .001).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analyses of Rating Scale Scores, Specific Binding Volume of Distribution, and the Combined Model of Rating Scale Scores Plus Specific Binding Volume of Distribution for the Prediction of Quit Status With Treatmenta

| Variable | Rating Scale Score | VS/fP | Rating Scale Score + VS/fP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df) | P Value | χ2 (df) | P Value | χ2 (df) | P Value | |

| Wald χ2 | ||||||

| FTND score | 0.1 (1) | .77 | 0.002 (1) | .96 | ||

| UTS craving scale score | 4.9 (1) | .03 | 2.6 (1) | .11 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 1.6 (1) | .21 | 0.4 (1) | .51 | ||

| VS/fP | 17.1 (1) | <.001 | 10.5 (1) | .001 | ||

| Model χ2 | 11.0 (3) | .01 | 26.4 (1) | <.001 | 30.7 (4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: FTND, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; UTS, Urge to Smoke; VS/fP, specific binding volume of distribution.

Logistic regression analyses of quit status as determined by rating scale scores alone, VS/fP values alone, and all measures combined. Comparison likelihood ratio χ2 test results were as follows: for rating scale score + VS/fP vs rating scale score, , P < .001; for rating scale score + VS/fP vs VS/fP, , P = .23. Likelihood ratio tests show that VS/fP significantly increases the predictive power of rating scale scores but that rating scale scores do not significantly supplement the predictive power of VS/fP values.

Discussion

Cigarette smokers with less severe upregulation of available brain α4β2*nAChR shave an improved chance of quitting smoking with treatment than smokers with more severe upregulation. This finding was present in smokers treated with nicotine and placebo patch and is consistent with a preliminary indication in a prior report by our group examining smaller groups of smokers treated with cognitive behavioral therapy, bupropion, or pill placebo.51 Furthermore, the degree of α4β2* nAChR upregulation (a biological phenomenon) was significantly associated with quitting even after adjusting for known associations between subjectively rated symptoms (severity of nicotine dependence, craving, and self-efficacy) and quit status, indicating a very strong association between the biological measure and quitting. Prior research indicates that the level of upregulation of α4β2* nAChR availability may primarily reflect the extent of nicotine exposure51; therefore, the biological measure determined here may indicate that markers of brain nicotine exposure may be highly useful in predicting smoking cessation treatment response. This hypothesis is supported by prior research indicating that plasma and salivary markers of greater nicotine exposure are associated with worse treatment response.82,83 Findings here were also widespread throughout the brain, including all ROIs studied, which is consistent with prior research demonstrating significant upregulation of nAChR densities in all brain regions studied other than the thalamus.41

Predictors of response are helpful for treatment planning in smoking cessation programs because smokers with poorer projected outcomes may need more intensive and/or lengthier treatment than smokers with better projected outcomes.84,85 While the costly, time-consuming PET procedure used here is not likely to be used clinically, simpler PET or single-photon emission CT methods with shorter scanning times (ie, <1 hour, as is common with brain imaging86–88) could be tested and applied to help guide treatment for cigarette smoking in the future. Our study indicates that smokers with greater upregulation of nAChRs may require higher medication doses (eg, higher doses of nicotine patch or patch plus another form of nicotine replacement) or more intensive psychotherapy than smokers with less upregulation. In addition, these methods of predicting treatment response could be tested for other medications that affect nAChRs, such as other forms of nicotine replacement or the α4β2* nAChR partial agonist varenicline tartrate,89,90 or for combination treatment including psychotherapy (as is commonly used in clinical practice8,91).

A central limitation of the study was sample size. Although this study was relatively large for a PET experiment of this type, relatively few smokers (15%) quit with placebo patch treatment. While this low quit rate with placebo patch was expected, the small number of quitters in this subgroup precluded a definitive determination of the interaction between nAChR availability, treatment type, and quit status. However, it should be noted that quitters and nonquitters in both treatment subgroups had similar nAChR availabilities (Table 2) and that findings here were consistent with a prior study in which pill placebo was one of the interventions.51 Another limitation of the study was the absence of follow-up beyond the acute phase of treatment, given that smokers who quit with short-term (several-month) treatment may relapse over longer periods.92 Because of this limitation, results here should be interpreted with caution regarding long-term smoking cessation outcomes. A third limitation was that participants were not excluded for previous history of nicotine patch use, which could have affected the blinding. Additionally, while our findings have been consistent for otherwise healthy moderate smokers, future studies could include smokers with more complex psychiatric and drug or alcohol dependence histories or lighter (<10 cigarettes/d) or heavier (>40 cigarettes/d) smoking for even greater generalizability.

Conclusions

Cigarette smokers with less upregulation of available brain α4β2* nAChRs have an improved chance of quitting smoking than smokers with more upregulation. This association was significant even after controlling for known associations between subjectively rated symptoms (severity of nicotine dependence, craving, and self-efficacy) and quit status, indicating a very strong association between this biological measure and quitting. Because prior research demonstrates that the extent of α4β2* nAChR upregulation is a marker for brain nicotine exposure, this study indicates that markers for brain nicotine exposure may be highly useful in the future for predicting smoking cessation treatment responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr Rose is principal investigator and Dr Mukhin is a coinvestigator on a grant from Philip Morris Inc for research unrelated to this study. Dr Rose also has a patent purchase agreement with Philip Morris International for nicotine inhalation technology unrelated to this study.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant R01 DA20872 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dr Brody), grant 19XT-0135 from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (Dr Brody), and Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Review Award I01 CX000412 from the Office of Research and Development, US Department of Veterans Affairs (Dr Brody).

Role of the Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Brody and Mandelkern had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Brody, Mukhin, Rose, Mandelkern.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Brody, Mukhin, Mamoun, Luu, Neary, Liang, Shieh, Sugar, Mandelkern.

Drafting of the manuscript: Brody, Luu, Mandelkern.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Brody, Mukhin, Mamoun, Neary, Liang, Shieh, Sugar, Rose, Mandelkern.

Statistical analysis: Brody, Sugar, Mandelkern.

Obtained funding: Brody.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Brody, Mamoun, Luu, Neary, Liang, Shieh, Rose.

Study supervision: Brody, Mamoun, Mandelkern.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No other disclosures were reported.

Additional Contributions: Shahrdad Lotfipour, PhD, University of California, Los Angeles, collected data on which the regional nondisplaceable volume of distribution values were calculated; he received no compensation from the funders for this contribution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartal M. Health effects of tobacco use and exposure. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2001;56(6):545–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leistikow BN, Martin DC, Milano CE. Fire injuries, disasters, and costs from cigarettes and cigarette lights: a global overview. Prev Med. 2000;31(2, pt1):91–99. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leistikow BN. The human and financial costs of smoking. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21(1):189–197. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leistikow BN, Miller TR. The health care costs of smoking. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(7):471. author reply 472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults: United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(45):1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DW. Smoking prevalence among US veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):147–149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health & Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, et al. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(17):1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Davis L, Strausberg L, Varady A. Do heavy smokers benefit from higher dose nicotine patch therapy? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(3):226–233. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Schatzberg AF, et al. Nicotine patch and paroxetine for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):883–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes JR, Lesmes GR, Hatsukami DK, et al. Are higher doses of nicotine replacement more effective for smoking cessation? Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(2):169–174. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes S, Zwar N, Jiménez-Ruiz CA, et al. Bupropion as an aid to smoking cessation: a review of real-life effectiveness. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58(3):285–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray R, Schnoll RA, Lerman C. Nicotine dependence: biology, behavior, and treatment. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:247–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.041707.160511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westman EC, Behm FM, Simel DL, Rose JE. Smoking behavior on the first day of a quit attempt predicts long-term abstinence. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(3):335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6(suppl 2):S57–S62. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale LC, Glover ED, Sachs DP, et al. Bupropion for smoking cessation: predictors of successful outcome. Chest. 2001;119(5):1357–1364. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paluck EC, McCormack JP, Ensom MH, Levine M, Soon JA, Fielding DW. Outcomes of bupropion therapy for smoking cessation during routine clinical use. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(2):185–190. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batra A, Collins SE, Torchalla I, Schröter M, Buchkremer G. Multidimensional smoker profiles and their prediction of smoking following a pharmacobehavioral intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH. Cue-provoked craving and nicotine replacement therapy in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1136–1143. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berlin I, Singleton EG, Heishman SJ. Predicting smoking relapse with a multidimensional versus a single-item tobacco craving measure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haaga DA, Stewart BL. Self-efficacy for recovery from a lapse after smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(1):24–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li WW, Froelicher ES. Predictors of smoking relapse in women with cardiovascular disease in a 30-month study: extended analysis. Heart Lung. 2008;37(6):455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA, et al. Dynamic effects of self-efficacy on smoking lapse and relapse. Health Psychol. 2000;19(4):315–323. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnoll RA, James C, Malstrom M, et al. Longitudinal predictors of continued tobacco use among patients diagnosed with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(3):214–222. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2503_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Norman GJ, et al. Does smoking abstinence self-efficacy vary across situations? identifying context-specificity within the Relapse Situation Efficacy Questionnaire. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):516–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez E, Tatum KL, Glass M, et al. Correlates of smoking cessation self-efficacy in a community sample of smokers. Addict Behav. 2010;35(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiggers LC, Stalmeier PF, Oort FJ, Smets EM, Legemate DA, de Haes JC. Do patients’ preferences predict smoking cessation? Prev Med. 2005;41(2):667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Prediction of lapse from associations between smoking and situational antecedents assessed by ecological momentary assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91(2–3):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Japuntich SJ, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Piper ME, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Depression predicts smoking early but not late in a quit attempt. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(6):677–686. doi: 10.1080/14622200701365301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.al’Absi M, Carr SB, Bongard S. Anger and psychobiological changes during smoking abstinence and in response to acute stress: prediction of smoking relapse. Int J Psychophysiol. 2007;66(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Tyndale RF, Benowitz N, Lerman C. Nicotine metabolic rate predicts successful smoking cessation with transdermal nicotine: a validation study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation: who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA. 1994;271(8):589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyland A, Levy DT, Rezaishiraz H, et al. Reduction in amount smoked predicts future cessation. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(2):221–225. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mamede M, Ishizu K, Ueda M, et al. Temporal change in human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor after smoking cessation: 5IA SPECT study. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(11):1829–1835. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staley JK, Krishnan-Sarin S, Cosgrove KP, et al. Human tobacco smokers in early abstinence have higher levels of beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors than nonsmokers. J Neurosci. 2006;26(34):8707–8714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0546-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cosgrove KP, Batis J, Bois F, et al. beta2-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability during acute and prolonged abstinence from tobacco smoking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):666–676. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brody AL, Mukhin AG, La Charite J, et al. Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(5):957–966. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukhin AG, Kimes AS, Chefer SI, et al. Greater nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density in smokers than in nonsmokers: a PET study with 2-18F–FA-85380. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(10):1628–1635. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.050716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wüllner U, Gündisch D, Herzog H, et al. Smoking upregulates alpha4beta2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the human brain. Neurosci Lett. 2008;430(1):34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benwell ME, Balfour DJK, Anderson JM. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (−)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. J Neurochem. 1988;50(4):1243–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breese CR, Marks MJ, Logel J, et al. Effect of smoking history on [3H]nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Tian JY, Svensson AL, Gong ZH, Meyerson B, Nordberg A. Chronic treatments with tacrine and (−)-nicotine induce different changes of nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain of aged rat. J Neural Transm. 2002;109(3):377–392. doi: 10.1007/s007020200030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoaib M, Schindler CW, Goldberg SR, Pauly JR. Behavioural and biochemical adaptations to nicotine in rats: influence of MK801, an NMDA receptor antagonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;134(2):121–130. doi: 10.1007/s002130050433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauly JR, Marks MJ, Robinson SF, van de Kamp JL, Collins AC. Chronic nicotine and mecamylamine treatment increase brain nicotinic receptor binding without changing alpha 4 or beta 2 mRNA levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278(1):361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauly JR, Stitzel JA, Marks MJ, Collins AC. An autoradiographic analysis of cholinergic receptors in mouse brain. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22(2):453–459. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yates SL, Bencherif M, Fluhler EN, Lippiello PM. Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors following chronic exposure of rats to mainstream cigarette smoke or alpha 4 beta 2 receptors to nicotine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50(12):2001–2008. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brody AL, Mukhin AG, Shulenberger S, et al. Treatment for tobacco dependence: effect on brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor density. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(8):1548–1556. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamilton M. Diagnosis and rating of anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;(special publication 3):76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 55.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jarvik ME, Madsen DC, Olmstead RE, Iwamoto-Schaap PN, Elins JL, Benowitz NL. Nicotine blood levels and subjective craving for cigarettes. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66(3):553–558. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Condiotte MM, Lichtenstein E. Self-efficacy and relapse in smoking cessation programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1981;49(5):648–658. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Lawrence DL, Jorenby DE, Shiffman S, Baker TB. Psychological mediators of bupropion sustained-release treatment for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2008;103(9):1521–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rose JE, Herskovic JE, Trilling Y, Jarvik ME. Transdermal nicotine reduces cigarette craving and nicotine preference. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38(4):450–456. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levin ED, Conners CK, Sparrow E, et al. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;123(1):55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shiffman S, Ferguson SG. The effect of a nicotine patch on cigarette craving over the course of the day: results from two randomized clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(10):2795–2804. doi: 10.1185/03007990802380341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Penetar DM, Kouri EM, Gross MM, et al. Transdermal nicotine alters some of marihuana’s effects in male and female volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(2):211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:57–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ossip DJ, Abrams SM, Mahoney MC, Sall D, Cummings KM. Adverse effects with use of nicotine replacement therapy among quitline clients. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(4):408–417. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hatsukami D, Mooney M, Murphy S, LeSage M, Babb D, Hecht S. Effects of high dose transdermal nicotine replacement in cigarette smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(1):132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Griffith SD, Shiffman S, Heitjan DF. A method comparison study of timeline followback and ecological momentary assessment of daily cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(11):1368–1373. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Toll BA, Cooney NL, McKee SA, O’Malley SS. Do daily interactive voice response reports of smoking behavior correspond with retrospective reports? Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):291–295. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toll BA, Cooney NL, McKee SA, O’Malley SS. Correspondence between Interactive Voice Response (IVR) and Timeline Followback (TLFB) reports of drinking behavior. Addict Behav. 2006;31(4):726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brandon TH. Behavioral tobacco cessation treatments: yesterday’s news or tomorrow’s headlines? J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18) suppl:64S–68S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Richmond RL, Kehoe L, de Almeida Neto AC. Effectiveness of a 24-hour transdermal nicotine patch in conjunction with a cognitive behavioural programme: one year outcome. Addiction. 1997;92(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(5):978–982. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rigotti NA, Gonzales D, Dale LC, Lawrence D, Chang Y. CIRRUS Study Group A randomized controlled trial of adding the nicotine patch to rimonabant for smoking cessation: efficacy, safety and weight gain. Addiction. 2009;104(2):266–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hughes JR. Ethical concerns about non-active conditions in smoking cessation trials and methods to decrease such concerns. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, Jenkinson M. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):907–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(9):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rogers SW, Gahring LC, Collins AC, Marks M. Age-related changes in neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit α4 expression are modified by long-term nicotine administration. J Neurosci. 1998;18(13):4825–4832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04825.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mitsis EM, Cosgrove KP, Staley JK, et al. [123I]5-IA-85380 SPECT imaging of beta2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor availability in the aging human brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1097:168–170. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Japuntich SJ, Leventhal AM, Piper ME, et al. Smoker characteristics and smoking-cessation milestones. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(3):286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Paoletti P, Fornai E, Maggiorelli F, et al. Importance of baseline cotinine plasma values in smoking cessation: results from a double-blind study with nicotine patch. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(4):643–651. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09040643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nørregaard J, Tønnesen P, Petersen L. Predictors and reasons for relapse in smoking cessation with nicotine and placebo patches. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):261–271. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Hajek P, Gilburt SJ, Targett DA, Strahs KR. Efficacy of a nicotine lozenge for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1267–1276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, et al. Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) Tobacco Dependence Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(suppl 4):S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Newberg AB, Lariccia PJ, Lee BY, Farrar JT, Lee L, Alavi A. Cerebral blood flow effects of pain and acupuncture: a preliminary single-photon emission computed tomography imaging study. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15(1):43–49. doi: 10.1177/1051228404271005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Novak B, Milcinski M, Grmek M, Kocmur M. Early effects of treatment on regional cerebral blood flow in first episode schizophrenia patients evaluated with 99Tc-ECD-SPECT. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26(6):685–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takagi S, Takahashi W, Shinohara Y, et al. Quantitative PET cerebral glucose metabolism estimates using a single non-arterialized venous-blood sample. Ann Nucl Med. 2004;18(4):297–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02984467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, et al. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48(10):3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.West R, Baker CL, Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG. Effect of varenicline and bupropion SR on craving, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and rewarding effects of smoking during a quit attempt. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197(3):371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Brown RA, Emmons KM, Goldstein MG, Monti PM. The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hatsukami DK, Stead LF, Gupta PC. Tobacco addiction. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):2027–2038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60871-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.