Abstract

Background

Treatment cures over 90% of children with Wilms tumor (WT) who subsequently risk late morbidity and mortality. This study describes the 25-year outcomes of 5-year Wilms tumor survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS).

Procedure

The CCSS, a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study, assessed Wilms tumor survivors (n=1256), diagnosed 1970 – 1986, for chronic health conditions, health status, health care utilization, socioeconomic status, subsequent malignant neoplasms (SMNs), and mortality compared to the US population and a sibling cohort (n=4023).

Results

The cumulative incidence of all and severe chronic health conditions was 65.4% and 24.2% at 25 years. Hazard Ratios [HR] were 2.0, 95% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.8-2.3 for grades 1 -4 and 4.7, 95% CI, 3.6-6.1 for grade 3-4, compared to sibling group. WT survivors reported more adverse general health status than the sibling group (Prevalence Ratio [PR] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.4), but mental health status, socioeconomic outcome, and health care utilization were similar. The cumulative incidence of SMN was 3.0% (95%CI, 1.9–4.0%) and of mortality was 6.1% (95%CI, 4.7-7.4%). Radiation exposure increased the likelihood of congestive heart failure (CHF) (no doxorubicin - HR 6.6; 95%CI, 1.6-28.3; doxorubicin ≤ 250 mg/m2 - HR 13.0; 95%CI, 1.9-89.7; doxorubicin > 250 mg/m2 - HR 18.3; 95%CI, 3.8-88.2), SMN (Standardized Incidence Ratio [SIR] 9.0; 95%CI, 3.9-17.7 with and 4.9; 95%CI, 1.8-10.6 without doxorubicin) and death.

Conclusion

Long-term survivors of WT treated from 1970 to 1986 are at increased risk of treatment related morbidity and mortality 25 years from diagnosis.

Keywords: Wilms Tumor, late effects, survivorship

Introduction

Since the mid-1980s, the five-year survival rate of children diagnosed with Wilms Tumor (WT) exceeds 90% [1]. From 1970 to 1986, the treatment era of eligibility for the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), children with WT received first line therapy with either two- or three- drug chemotherapy (vincristine and dactinomycin, with or without doxorubicin), and, depending on stage of disease at diagnosis, radiation therapy (RT) to the flank, whole abdomen, and/or whole lung [2].

Previous reports from the CCSS and others on chronic health conditions[3], cardiac events[4], health status [5], activity level [6,7], education [8], marital status [9,10], employment [11], health insurance [12], screening [13], second neoplasms [14-17], and late mortality [18-20] among survivors of childhood cancers included WT cases along with survivors of other pediatric malignancies. The National Wilms Study Group published extensively on the fertility status, pregnancy outcomes, and offspring of WT survivors. Due to the smaller amount of offspring data, the lack of specific information about pregnancy complications, and the lack of new information being added in these topics, this report does not include fertility, pregnancy, and offspring outcomes. The current report provides a comprehensive assessment of all participants in the cohort and not restricted to those over the age of 18 years old at survey; treatment exposure data are also included.

Methods

The CCSS is a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study of pediatric cancer survivors originally diagnosed from 1970 to 1986 who were alive five years following diagnosis. A baseline questionnaire (http://ccss.stjude.org/documents/questionnaires), follow-up surveys, and abstraction of detailed treatment data from medical records constituted the data. A sibling comparison group was also assembled. The methodology of the CCSS has been published previously [21,22]. The CCSS was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Statistical Analysis

Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) and exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated using the methods described previously [18,19]. Person-years at risk were computed from the time of cohort entry to date of death or censoring. United States (US) participants were censored on December 31, 2002. Canadian survivors were censored on either December 31, 2002, or the date of last survey, whichever was earlier. The expected number of deaths for each year since diagnosis was calculated based on the US age-year-sex-specific mortality rates.

The cumulative incidence of subsequent malignant neoplasms (SMNs) was estimated using death as a competing risk event [23]. SMNs diagnosed before cohort entry were included as prevalent cases at cohort entry. Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) for the occurrence of SMNs and specific types of SMNs were calculated using the US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer incidences as reference rates [24].

The occurrence and severity of chronic health conditions were determined for all participants at baseline questionnaire according to the method described previously. Chronic health conditions with onset during the first five years after diagnosis of WT were included as prevalent cases at the cohort entry in the calculation of the cumulative incidence. The incidence of new chronic health conditions after cohort entry was assessed by Cox regression, estimating hazard ratios (HRs) adjusted for age at enrollment, sex, and race/ethnic group. The proportionality assumption of hazard functions was assessed graphically. When the WT survivors and CCSS siblings were compared, within-family correlations were accounted for by using sandwich standard error estimates [25]. The baseline questionnaire also collected self-reported occurrence of genetic conditions.

For analyses of social and economic outcomes, only survivors and siblings ≥ 25 years of age at last follow-up were included because this was an age at which independence from parents might be anticipated. Age-adjusted comparisons were made between the two groups using bootstrap to account for potential within-family correlations [26].

Health status was assessed for WT survivors ≥ 18 years of age at baseline questionnaire, including general health, mental health, functional status, and limitations of activity [5]. For general health, participants were asked, “Would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor? ”. Adverse general health was scored with responses of fair or poor. The 18-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18), a self-report measure of psychological symptoms, was used for the mental health domain. Responses were scored according to the published manual with each participant receiving a T-score (mean = 50, SD = 10) on the Global Severity Index, as well as the three symptom-specific subscales—depression, somatization, and anxiety. Participants who had a significant elevation (T-score ≥ 63 represents the upper 10th percentile of scores reported in a community sample) on any of the three symptom-specific subscales were classified as having adverse mental health [5].

Questions assessing functional status and limitations of activity were adapted from the National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire [5]. Adverse functional status was determined if respondents indicated they had any impairment or health problem that resulted in needing assistance with personal care, routine household chores, or attending school/working. Limited activity status was determined if respondents indicated that for 3 months in the last two years their health limited moderate physical activities, climbing stairs or walking a block. Siblings were asked the same questions as survivors regarding general health, mental health, functional status and activity status [5].

Log-binomial regression was used to estimate the prevalence ratio for each health status domain, comparing the WT survivors and CCSS siblings, adjusting for age at survey, sex, and race/ethnic group (white vs. nonwhite) [5]. Modifications of a log-binomial model with generalized estimating equations were used to account for potential within-family correlation [27].

In all analyses, treatment exposures within the first five years of the original WT diagnosis were considered. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and R 2.10.1, and all statistical inferences were two-sided.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Table I shows the characteristics of the WT survivors and the CCSS sibling cohort. At the time of completion of their last questionnaire (or death), 22% of the WT survivors were > 30 years of age. Thirty-nine percent of the WT survivors received abdominal RT, 23% had combined chest and abdominal RT, and 39% received doxorubicin. Over 94% of the WT survivors received only front-line therapy; 5.4% of the cohort survived a relapse. The WT survivors reported no hemihypertrophy, aniridia, Beckwith-Wiedmemann syndrome, severe mental retardation, or other genetic conditions on the baseline questionnaire. One did report a sibling with hemihypertrophy and three reported severe mental retardation is siblings. Thirteen WT survivors reported mental retardation in the nervous system section of the questionnaire but not in the genetics section. The mean radiation dose to the uninvolved contralateral kidney was 668.7 cGy (standard deviation 580.3 cGy; median, 370 cGy; range, 15 to 2,780 cGy) and the mean radiation dose to the heart was 1,567 cGy (standard deviation 502 cGy; median, 1,420 cGy; range, 340 to 3,470 cGy). Estimate of radiation exposure to breast tissue is 1,500 cGy from whole lung and abdominal radiation.

Table I. Characteristics of CCSS Wilms Tumor survivors and sibling comparison group.

| Characteristics | Survivors (N=1256) | Siblings (N=4023) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | |

| Sex of patient | ||||

|

| ||||

| Male | 47.0 | (590) | 48.1 | (1937) |

|

| ||||

| Female | 53.0 | (666) | 51.9 | (2086) |

|

| ||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

|

| ||||

| 0-3 | 63.8 | (801) | ||

|

| ||||

| 4-9 | 32.5 | (408) | ||

|

| ||||

| 10-14 | 2.6 | (33) | ||

|

| ||||

| 15-20 | 1.1 | (14) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age at latest questionnaire or death (yrs) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 5 – 9 | 0.4 | (5) | 0.3 | (12) |

|

| ||||

| 10 – 19 | 18.4 | (231) | 9.5 | (381) |

|

| ||||

| 20 – 29 | 58.9 | (740) | 34.4 | (1384) |

|

| ||||

| 30 – 39 | 21.4 | (269) | 34.6 | (1391) |

|

| ||||

| 40 - 49 | 0.9 | (11) | 18.8 | (755) |

|

| ||||

| ≥ 50 | 0.0 | (0) | 2.5 | (100) |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up from diagnosis (yrs) | ||||

|

| ||||

| 5-14 | 9.7 | (122) | ||

|

| ||||

| 15-24 | 63.5 | (798) | ||

|

| ||||

| 25+ | 26.8 | (336) | ||

|

| ||||

| Treatment Groups† | ||||

|

| ||||

| No Chest RT* | 36.9 | (386) | ||

| No Abd RT | ||||

|

| ||||

| No Chest RT | 39.3 | (411) | ||

| Abd RT | ||||

|

| ||||

| Chest RT | 1.1 | (12) | ||

| No Abd RT | ||||

|

| ||||

| Chest RT | 22.7 | (238) | ||

| Abd RT | ||||

|

| ||||

| Relapsed Wilms Tumor | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 5.4 | (68) | ||

|

| ||||

| No | 94.6 | (1188) | ||

|

| ||||

| Doxorubicin dose† | 41.1 | (446) | ||

|

| ||||

| None | 60.8 | (638) | ||

|

| ||||

| <250 mg/m2 | 17.1 | (180) | ||

|

| ||||

| ≥ 250 mg/m2 | 22.1 | (232) | ||

Based on data from survivors who consented to medical record abstraction: a Small number of missing values may exist in the medical records of those consented.

RT = Radiation Therapy; Abd = Abdominal

Chronic health conditions

The cumulative incidence of chronic health conditions at 25 years after diagnosis for all WT survivors completing the baseline questionnaire was 65.4% and that of severe conditions (grades 3 to 5) was 24.2% (Figure 1). WT survivors had twice the rate of grades 1 to 4 chronic health conditions (Hazard Ratio [HR] 2.0; 95%CI, 1.8 - 2.3) and 4.7 times higher rates of severe chronic health conditions (grades 3 or 4) (HR 4.7; 95%CI, 3.6 - 6.1) than the sibling comparison group. The HRs were 23.6 (95%CI, 10.8 - 51.5) for congestive heart failure (CHF), 50.7 (95%CI, 14.5 - 177.4) for renal failure, and 8.2 (95%CI, 6.4 - 10.5) for hypertension (HTN), compared to the sibling group.

Figure 1.

Treatment exposure to RT and anthracycline were analyzed as risk factors for development of CHF, renal failure, and HTN. Exposure to doxorubicin, in the absence of cardiac RT, did not show a clear association with an increased risk of CHF (≤ 250 mg/m2, HR 4.8; 95%CI, 0.7 - 31.6; > 250 mg/m2, HR 1.6; 95%CI, 0.2 - 16.1). Cardiac RT was associated with an elevated risk of developing CHF. In the absence of doxorubicin, cardiac RT was associated with a HR of 6.6 (95%CI, 1.6 – 28.3) for CHF. The HR for CHF was increased among those who received both cardiac RT and doxorubicin (≤ 250 mg/m2, HR 13.0; 95%CI, 1.9 - 89.7; > 250 mg/m2, HR 18.3; 95%CI, 3.8 - 88.2). RT to the contralateral kidney was not a risk factor for developing HTN or renal failure (data not shown).

Health Status, Social and Economic Outcomes

Compared to the sibling group, WT survivors reported more adverse general health status (Prevalence Ratio [PR] 1.7, 1.2 – 2.4; p = 0.001), functional impairment (PR 3.3, 2.3 – 4.8; p < .001), and activity limitations (PR 1.9, 1.4 – 2.5; p < .001). WT survivors did not report adverse mental health status more frequently than the siblings (PR 1.2, 1.0 – 1.6; p = 0.09).

Table II shows the socioeconomic outcomes for WT survivors and siblings over the age of 25 years at the time of participation. A slightly higher proportion of siblings graduated from college and had held a job; the differences were marginally statistically significant (p=0.045 and 0.046, respectively). There were no differences in marital status, income, or insurance coverage (Table II).

Table II. Frequencies of social and economic outcomes in survivors of Wilms tumor and siblings over 25 years of age at the latest questionnaire.

| Wilms tumor survivors | Siblings | P for survivors vs. siblings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | N | Percentage | N | ||

| Ever married | 0.35 | ||||

| No | 33.0 | 213 | 20.1 | 595 | |

| Yes | 63.3 | 408 | 79.8 | 2353 | |

| Missing | 3.7 | 24 | 0.5 | 14 | |

| Education | 0.045 | ||||

| Not high school graduate | 2.2 | 14 | 2.8 | 84 | |

| High school graduate/GED | 50.2 | 324 | 45.2 | 1339 | |

| College graduate | 45.0 | 290 | 51.4 | 1521 | |

| Missing | 2.6 | 17 | 0.6 | 18 | |

| Ever Employed | 0.046 | ||||

| No | 1.1 | 7 | 0.2 | 7 | |

| Yes | 96.6 | 623 | 99.6 | 2951 | |

| Missing | 2.3 | 15 | 0.1 | 4 | |

| Personal income ($) | 0.48 | ||||

| <19,999 | 32.1 | 207 | 26.2 | 775 | |

| 20,000-39,999 | 31.3 | 202 | 29.5 | 874 | |

| 40,000-59,999 | 14.7 | 95 | 18.2 | 540 | |

| Over 60,000 | 11.0 | 71 | 19.4 | 575 | |

| Missing | 10.9 | 70 | 6.7 | 198 | |

| House income ($) | 0.78 | ||||

| <19,999 | 8.5 | 55 | 6.9 | 203 | |

| 20,000-39,999 | 22.8 | 147 | 17.0 | 503 | |

| 40,000-59,999 | 19.1 | 123 | 19.6 | 581 | |

| Over 60,000 | 36.1 | 233 | 50.0 | 1482 | |

| Missing | 13.5 | 87 | 6.5 | 193 | |

| Health Insurance | 0.18 | ||||

| No | 13.8 | 89 | 9.1 | 270 | |

| Yes | 76.3 | 492 | 83.2 | 2464 | |

| Canadian resident | 6.8 | 44 | 7.4 | 219 | |

| Missing | 3.1 | 20 | 0.3 | 9 | |

Medical care

WT survivors under the age of 30 years had more general medical examinations than the CCSS siblings in the same age group (Prevalence Ratio [PR] 1.1; 95%CI, 1.1 - 1.2). There were no differences in the frequencies of testicular self examination, breast examinations (self or by a medical professional), Papanicolaou smear screening, or general medical examinations between WT survivors and siblings who were more than 30 years of age (data not shown). Of all female WT survivors who received RT to the chest, 87% reported ever having a breast examination by a health care professional. Thirteen percent of those who were less than 30 years of age, and 57% of those who were more than 30 years of age, reported having had a mammogram.

Subsequent malignant neoplasms (SMNs)

Thirty-five SMNs occurred in 33 patients prior to the completion of the latest questionnaire. The cumulative incidence of SMN (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) was 3.0% at 25 years (Figures 2A and 2B). The most common SMNs were soft tissue sarcomas which occurred in six survivors. Five WT survivors had confirmed breast cancer. Radiation exposure of the breast in survivors who developed breast cancer ranged from 1300 to 1750 cGy. There were four bone tumors: two osteogenic sarcomas; one Ewing sarcoma; and one other bone tumor. The other SMNs were adenocarcinoma (4), melanoma (3), thyroid (3), lymphoid leukemia (2), medulloblastoma (1), and other cancers (7) including one secondary renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 2.

The Standardized Incidence Ratio (SIR) for SMN for WT survivors was 3.4 (95%CI, 2.4 - 4.7). Survivors who received abdominal RT without chest RT or doxorubicin exposure had a SIR of 3.4 (95%CI, 1.5 - 6.5). Those exposed to abdominal and chest RT without doxorubicin had a SIR of 4.9 (95%CI, 1.8 - 10.6) and those exposed to abdominal and chest RT with doxorubicin had a SIR of 9.0 (95%CI, 3.9 - 17.7). The SIR for WT survivors with a history of disease relapse was elevated but did not reach a level of statistical significance due to the small number of subjects.

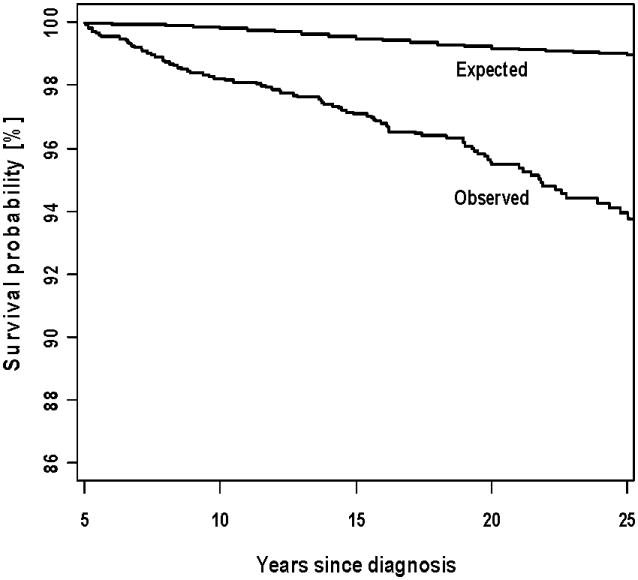

Survival

The overall survival rate at 25 years after diagnosis of WT among the 5-year WT survivors of the CCSS was 93.9% (95%CI, 92.6 - 95.3) (Figure 3). Table III shows the Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) by treatment exposure. The overall SMR is 4.9 (95%CI, 4.0 - 6.1). Survivors who received abdominal and chest RT demonstrated an increased SMR: 6.1 (95%CI, 2.6 - 12.1) in those with no doxorubicin exposure and 12.3 (95%CI, 6.9 - 20.3) in those with doxorubicin exposure. Patients with WT who survived a relapse also had an increased SMR (Table III).

Figure 3.

Table III. Standardized mortality ratios (SMR) of five-year Wilms tumor survivors by treatment exposure and relapsed status.

| No Doxorubicin (N = 638) | Doxorubicin (N = 446) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest RT | Abdominal RT | Number of patients | Number of deaths | SMR (95% CI) | Number of patients | Number of deaths | SMR (95% CI) | ||

| No | No | 328 | 5 | 1.8 (0.6 – 4.2) | 58 | 1 | 2.7 (0.0 – 14.8) | ||

| No | Yes | 202 | 7 | 2.2 (0.9 – 4.6) | 209 | 12 | 6.1 (3.2 – 10.6) | ||

| Yes | No | 6 | 1 | 21.0 (0.3 – 116.6) | 6 | 1 | 16.3 (0.2 – 90.7) | ||

| Yes | Yes | 88 | 8 | 6.1 (2.6 – 12.1) | 150 | 15 | 12.3 (6.9 – 20.3) | ||

| Relapsed WT | 9 | 2 | 24.5 (2.8 – 88.4) | 52 | 11 | 27.2 (13.6 – 48.6) | |||

A total of 94 deaths occurred in the WT cohort. The most common cause of death (n=27) was SMN. Recurrent disease, cardiac, and pulmonary events accounted for 22, 11, and 2 deaths, respectively. External causes (homicides, suicides, accidents) accounted for 11 deaths. Other deaths, specifically gastrointestinal diseases or infections (4), hepatitis, arteriosclerosis, circulatory disease, blood disorder, urinary system disease, myopathy, and nutritional/metabolic disease, resulted in 12 deaths and there were 9 deaths where a cause was not able to be identified.

Discussion

This comprehensive review of WT survivors within the CCSS cohort demonstrates new findings. Twenty-five year WT survivors report a high frequency of chronic health conditions, including severe health conditions. WT survivors exhibit more adverse health status, functional impairment, and activity limitations, but report socioeconomic status and mental health status that is not different from the sibling comparison group.

The overall frequency of reporting any chronic health condition is similar to that of Geenen et al. [28]. The higher frequency of severe chronic health conditions relates to the difference in classification of events and the overlap between the definitions in the two studies.

A unique feature of the CCSS design was the inclusion of questions about specific chronic health conditions. Survivors of WT develop congestive heart failure, renal failure, and hypertension. Treatment with doxorubicin alone did not increase the risk of CHF, but doxorubicin in combination with cardiac RT did. This differs from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group (NWTSG) data where CHF was associated with exposure to a higher dose of anthracycline [29]. The difference may be accounted for by the use of medical record data abstraction by the CCSS for determining exposure or by the larger size of the NWTSG long-term follow-up cohort. CHF is self-reported in the CCSS. A previous study of cardiac outcomes documented the difficulty in validation of specific cardiac outcomes including CHF [4]. There is also the possibility that survivors who developed CHF experienced early mortality and were not represented in the CCSS cohort. Despite the fact that most children treated for WT undergo a nephrectomy, there were too few participants who developed renal failure to determine whether radiation exposure to the contralateral kidney impacted its development. Data from the NWTSG suggested that genetic predisposition (Denys-Drash syndrome or Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary malformation and mental retardation (WAGR) syndrome) and bilateral Wilms tumor were the most frequent causes of end stage renal disease [30]. The WT survivors in this study did not report any genetic predisposing conditions. This may reflect underreporting or may indicate that patients with those underlying conditions did not meet the eligibility criteria of surviving 5 years after diagnosis. The literature regarding the occurrence of HTN following WT diagnosis and treatment is inconsistent. The published studies involved small numbers of patients and vary by duration of follow-up and the definition of HTN [31-33]. The CCSS assessed HTN with the following questions: “Have you ever been told you had hypertension?” and “Do you take medication for blood pressure?”. Radiation to the remaining kidney did not increase the likelihood of responding affirmatively to these questions.

Although the present study included more adult CCSS WT survivors with additional years of follow-up, the increased odds ratios of reporting adverse general health status, functional impairment, and activity limitations compared to the sibling group were similar to previous CCSS reports. The present study did not reveal an increase in adverse mental health status in survivors compared to siblings, as noted previously [5]. There were no significant differences in marital status or insurance coverage between survivors and siblings. However, fewer WT survivors reported graduating from college and ever having been employed compared to the sibling cohort. These results are consistent with earlier publications from the CCSS [8,9,11,12].

The frequencies of self-screening for breast cancer and testicular cancer were similar in the WT survivors, their siblings, and the general population. It was encouraging to see that almost 90% of female WT survivors treated with chest RT, now over 30 years of age at response, reported having a breast examination by a medical professional and almost 60% reported a recent mammogram.

SMNs have been well-described in WT survivors and have been associated with exposure to RT [14-17,34,35]. The cumulative incidence in this study was relatively low (3% at 25 years) and was comparable to other studies. Secondary sarcomas were the most common SMN. In contrast to a previous report of secondary renal tumors, we identified only one– a renal cell carcinoma [36]. Abdominal RT, with or without chest RT, increased the risk of developing a SMN. Doxorubicin exposure in the absence of RT did not increase the SMN risk among the CCSS WT survivors, although this risk was increased in the NWTSG survivor cohort [17]. A study of SMNs in pooled North American, British, and Nordic WT survivors could not evaluate the impact of doxorubicin and RT due to a lack of available treatment data [14]. The risk of developing a secondary leukemia following WT therapy was 0.2% at 25 years and was stable at 30 years of follow-up. The incidence of secondary solid tumors continued to increase with increasing duration of follow-up, consistent with other studies [14,34,37,38].

The standardized mortality ratio for WT survivors has changed marginally with longer duration of follow-up. Mertens initially reported a SMR of 6.2 (95%CI, 4.8 - 7.9) which changed slightly at the time of follow-up analyses to 4.6 (95%CI, 3.8 - 5.6) and 4.9 (95%CI, 4.0 - 6.1) for patients with renal tumors [18,19]. These data are consistent with findings from the Nordic study and the UK CCSS that demonstrated a general decrease in SMR with increasing duration of follow-up [39,40]. Updated data from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (BCCSS) show a SMR of 5.8 (4.9 – 6.9) for over 34,000 person years of WT survivorship.[20]

The causes of mortality are remarkably similar across both large and small studies of WT survivors. The report based on the Nordic population, those derived from the United Kingdom registry, and a smaller study describing WT survivors in the British Columbia registry showed that most deaths were due to recurrence of Wilms tumor, followed by SMN, other medical complications, and then external causes (suicide, homicide, accidents) [39-42]. Compared to these studies, we observed a relative decrease in deaths from recurrence. This likely reflects the length of follow-up as recurrent disease is more influential with shorter duration of follow-up and survivors are less likely to accumulate large numbers of very late occurring events. The analysis by Reulen et al. of the BCCSS demonstrates an increasing proportion of deaths due to second malignancy and cardiac disease, likely treatment related, as survivors achieve longer follow-up [20]. Cancer treatment related complications are the second or third most common cause of death across the larger studies from the UK and the Nordic Group, similar to this study [39,40,42]. Late deaths in WT survivors are commonly cardiac, pulmonary and renal in origin. There is no difference in deaths from external causes across multiple studies and countries (homicide, suicide, or accident) [18,19,39,40].

The CCSS, with its ascertainment of detailed treatment data, allowed testing the hypothesis that exposure to RT increased the risk of mortality and that exposure to doxorubicin would potentiate that effect. The standardized mortality ratio of patients who had received chest and abdominal RT with exposure to doxorubicin was twice that of those without anthracycline exposure. Doxorubicin exposure alone did not increase the SMR in WT survivors. The Nordic study and the UK registry studies did not include treatment data so comparison was not possible [39,42].

There are several limitations to this study. The CCSS is a retrospective cohort study and subject to selection bias. Previous analysis of subjects revealed no difference in characteristics of those participating and those who were eligible but did not participate [22]. The CCSS relies on self-reported data. Analysis of the self-reporting of chronic health conditions also revealed minimal selection bias [43]. Socioeconomic outcomes were analyzed in a subgroup of the cohort due to the age distribution. The investigators acknowledge that the sibling comparison group may not be ideal for comparison on psychosocial outcomes in that they are also impacted by the diagnosis of cancer within the family.

Long term WT survivors remain at risk for serious chronic health conditions, adverse health outcomes and excess mortality from treatment but do not differ from the sibling group in most socioeconomic outcomes or general mental health status. There is opportunity for improvement in the medical surveillance and cancer screening for long-term survivors of Wilms tumor. The impact of decreased radiation exposure in the late 1980s through 2000 on the frequency of severe chronic health conditions, morbidity, and mortality will be studied in the expanded CCSS cohort.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by United States Public Health Service grant no. CA-55727 (L.L. Robison, Principal Investigator) and CA-21765 (M.B. Kastan, Principal Investigator), support provided to the University of Minnesota Cancer Center from the Children's Cancer Research Fund and support provided by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Drs. Termuhlen, Tersak, Yasui, Stovall, Deutsch, Sklar, Oeffinger, Armstrong, Robison and Green, Q. Liu, and R. Weathers have no potential conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests, relationships or affiliations relevant to the subject of this manuscript.

The data in this report were presented in part at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 4 – 8, 2010 in Chicago, Illinois and the 11th International Conference on Long-Term Complications of Treatment of Children and Adolescents for Cancer, June 11-12, 2010 in Williamsburg, Virginia.

References

- 1.Green DM. The treatment of stages I-IV favorable histology Wilms' tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1366–1372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Angio GJ, Evans AE, Breslow N, et al. The treatment of Wilms' tumor: Results of the national Wilms' tumor study. Cancer. 1976;38(2):633–646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197608)38:2<633::aid-cncr2820380203>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Br Med J. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Jama. 2003;290(12):1583–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, et al. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):639–647. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, et al. Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2003;97(4):1115–1126. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauck AM, Green DM, Yasui Y, et al. Marriage in the survivors of childhood cancer: a preliminary description from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33(1):60–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<60::aid-mpo11>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, et al. Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(10):2626–2635. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pang JW, Friedman DL, Whitton JA, et al. Employment status among adult survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(1):104–110. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y, et al. Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9187–9197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–4409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow NE, Lange JM, Friedman DL, et al. Secondary malignant neoplasms after Wilms tumor: an international collaborative study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(3):657–666. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neglia JP, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, et al. Second malignant neoplasms in five-year survivors of childhood cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(8):618–629. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Neglia JP, et al. Second neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer: findings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2356–2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslow NE, Takashima JR, Whitton JA, et al. Second malignant neoplasms following treatment for Wilm's tumor: a report from the National Wilms' Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(8):1851–1859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3163–3172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, et al. JAMA. Vol. 304. United States: 2010. Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer; pp. 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(4):229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, et al. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence- SEER9 Limited-Use Data (1973-2005), Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment-Linked to County Attributes-Total US, 1969-2005 Counties. National Cancer Institue, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; 2008. http://www.seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Royall RM. Model robust confidence intervals using maximum likelihood estimators. Int Stat Rev. 1986;54(2):221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efron BTR. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometricka. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Jama. 2007;297(24):2705–2715. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green DM, Grigoriev YA, Nan B, et al. Congestive heart failure after treatment for Wilms' tumor: a report from the National Wilms' Tumor Study group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(7):1926–1934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.7.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breslow NE, Collins AJ, Ritchey ML, et al. End stage renal disease in patients with Wilms tumor: results from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group and the United States Renal Data System. J Urol. 2005;174:1972–1975. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176800.00994.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kantor AF, Li FP, Janov AJ, et al. Hypertension in long-term survivors of childhood renal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(7):912–915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.7.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haddy TB, Mosher RB, Reaman GH. Hypertension and prehypertension in long-term survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(1):79–83. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finklestein JZ, Norkool P, Green DM, et al. Diastolic hypertension in Wilms' tumor survivors: a late effect of treatment? A report from the National Wilms' Tumor Study Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1993;16(3):201–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor AJ, Winter DL, Pritchard-Jones K, et al. Second primary neoplasms in survivors of Wilms' tumour--a population-based cohort study from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(9):2085–2093. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawkins MM, Wilson LM, Burton HS, et al. Radiotherapy, alkylating agents, and risk of bone cancer after childhood cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(5):270–278. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.5.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherullo EE, Ross JH, Kay R, et al. Renal neoplasms in adult survivors of childhood Wilms tumor. J Urol. 2001;165(6 Pt 1):2013–2016. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200106000-00059. discussion 2016-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhatia S, Yasui Y, Robison LL, et al. High risk of subsequent neoplasms continues with extended follow-up of childhood Hodgkin's disease: report from the Late Effects Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(23):4386–4394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldsby R, Burke C, Nagarajan R, et al. Second solid malignancies among children, adolescents, and young adults diagnosed with malignant bone tumors after 1976: follow-up of a Children's Oncology Group cohort. Cancer. 2008;113(9):2597–2604. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moller TR, Garwicz S, Barlow L, et al. Decreasing late mortality among five-year survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in the Nordic countries. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3173–3181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson CM, Hawkins MM, Kingston JE. Late deaths and survival after childhood cancer: implications for cure. Bmj. 1994;309(6948):162–166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6948.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacArthur AC, Spinelli JJ, Rogers PC, et al. Mortality among 5-year survivors of cancer diagnosed during childhood or adolescence in British Columbia, Canada. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(4):460–467. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawkins MM, Kingston JE, Kinnier Wilson LM. Late deaths after treatment for childhood cancer. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65(12):1356–1363. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.12.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ness KK, Leisenring W, Goodman P, et al. Assessment of selection bias in clinic-based populations of childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(3):379–386. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]