Abstract

The engraftment failure associated with Abs to donor-specific HLA (DSA) limits options for sensitized BMT candidates. Fourteen of fifteen patients with no other viable donor options were desensitized and transplanted using a regimen of plasmapheresis and low-dose i.v. Ig modified to accommodate pre-BMT conditioning. DSA levels were assessed by solid-phase immunoassays and cell-based crossmatch tests. DSA levels were monitored throughout desensitization and on day − 1 to determine if there was any DSA rebound that would require additional treatment. A mean reduction in DSA level of 64.4% was achieved at the end of desensitization, with a subsequent reduction of 85.5% after transplantation. DSA in 11 patients was reduced to levels considered negative post-BMT, whereas DSA in three patients remained at low levels. All 14 patients achieved donor engraftment by day +60; however, seven patients suffered disease relapses. Four patients experienced mild, grade 1 GVHD. Factors influencing the response to desensitization include initial DSA strength, number, specificity, DSA rebound and a mismatch repeated from a prior transplant. While desensitization should be reserved for patients with limited donor options, careful DSA assessment and monitoring can facilitate successful engraftment after BMT.

INTRODUCTION

The use of donors partially mismatched for one or more HLA alleles and full HLA haplotypes has increased in recent years to expand the number of potential donor options and to expedite rapid transplantation of patients for whom no unrelated donor exists or the time required for unrelated donor searches may be prohibitive.1–7 At the same time, numerous reports have associated the presence of donor HLA-specific Abs (DSA) with increased risk of engraftment failure.8–15 Although the risk imposed by high levels of DSA has been recognized since the late 1980s,16 the use of highly sensitive solid-phase immunoassays for HLA-specific Abs has increased the number of BMT candidates recognized to have lower levels of pre-existing sensitization. Using these techniques, the rates of sensitization range from 20 to 40% of patients with any HLA Abs and up to 24% of patients with DSA.9,11,13,14,17–20 In a retrospective analysis of nearly 300 consecutive cases of candidates for transplant with HLA-mismatched donors at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, we found that 14.5% of patients had DSA to one or more potential HLA-haploidentical donors.20 Not surprisingly, the DSA incidence was higher among females than among males (31% vs 5%) and was highest among parous females (42.9%).

Limited donor options and/or an urgent need to proceed to transplant have led us and others to attempt various means to lower DSA to levels that would permit successful donor stem cell engraftment.9,15,20–24 Protocols have included adsorption of Abs on Staphylococcus protein A columns or with donor platelets; treatment with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib; and various combinations of plasmapheresis (PP) with i.v. Ig (IVIG) and/or the anti-CD20 monoclonal Ab, rituximab (reviewed in Zachary and Leffell24). The majority of these reports have been anecdotal, including from one to four cases, but taken together have indicated that reduction of DSA to low levels can permit successful engraftment. Among recent reports, Ciurea et al.15 treated four patients with a combination of PP and rituximab before their haploidentical, mobilized PBSC grafts.15 DSA reduction was achieved for three patients. Two patients with DSA reduction engrafted, whereas one patient with reduction and one with no reduction both experienced graft failure. The desensitization approach of these authors consisted of two weekly doses of rituximab at 375 mg/m2 and two sessions of total volume PP starting 2 weeks before transplant. In 2010, Costa et al.21 successfully reduced DSA to a single HLA-DP mismatch for one patient who engrafted with a PBSC graft from an unrelated donor. Their approach involved PP on days − 3 to − 1 followed by infusion of IVIG at 1000 mg/kg. Norlander et al.22 treated two patients with HLA-specific DSA who were to receive umbilical cord blood stem cell transplants with a combination of total volume PP, rituximab and IVIG. One patient received 10 PP treatments before transplant and the other had four PP pretransplant and three post transplant. Both received one dose of rituximab at 375 mg/mm2, 2 weeks pretransplant and one dose of IVIG at 250 mg/kg after completion of all PP. These authors also used two umbilical cord blood stem cell units to increase the cell dose in an effort to reduce the risk of Ab-mediated rejection of the graft; however, engraftment was only achieved for one patient. Yoshihara et al.9 have tried three desensitization approaches for five patients who were to receive either BM or PBSC grafts from haploidentical donors: a combination of PP and rituximab; adsorption with platelets; and administration of the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib. One of the two patients treated with PP and rituximab received PP on day − 11 and the other received PP on days − 17, − 15 and − 13. Both were given a single dose of rituximab at 375 mg/mm2. DSA reduction was achieved for one patient, but not the other; however, both engrafted. The most impressive reduction of DSA was achieved by these authors with platelet transfusions of 40 U of platelets from healthy donors selected to have the HLA Ags corresponding to the DSA. For two patients so treated, the DSA were reduced to very low levels and both patients engrafted. In contrast to either the combination PP/rituximab or platelet transfusion, administration of bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 on days − 18 and − 15 resulted in only a slight decrease in DSA for one patient, but who did engraft despite the DSA. Treatment solely with IVIG has been tried for one patient who was to receive BM from an HLA-haploidentical donor. Ishiyama et al.23 gave 400 mg/kg of IVIG from day − 2 to +2. Only a moderate decrease in the DSA was observed and the authors speculated that the patient's engraftment was facilitated more by the IVIG preventing rapid destruction of donor cells through Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity than by DSA reduction.23

For our BMT recipients, we have used a modification of the PP and IVIG regimen developed at the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant center that has been highly successful in transplantation of more than 200 renal recipients.25 Our series of nine patients who underwent desensitization during their HLA-mismatched, reduced-intensity allogeneic BMT is the largest published to date.20 A notable feature of our series was that the nine patients who were treated all had relatively high levels of DSA, that is, levels that were positive at flow cytometric crossmatch (FCXM) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch (CDC XM) levels. The DSA in all but one patient were reduced following treatment to levels well below that consistent with a positive FCXM, and the eight patients subsequently transplanted all fully engrafted. We report here an update of our series with six additional patients successfully desensitized and describe our protocols for evaluation of DSA, determining patient eligibility, assessing the extent of desensitization required and monitoring the Ab course during desensitization. From our experience to date, we further provide observations on the relative levels of DSA that permit successful engraftment as well as the levels and types of DSA that may be less responsive to desensitization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient eligibility

Desensitization was considered for patients who met our institutional clinical criteria for HLA-mismatched reduced-intensity allogeneic BMT and who had no other related or unrelated donor to whom they did not have DSA. Other factors considered included a patient's ability to undergo PP and the likelihood of reducing the DSA to levels below detectability by flow cytometry (discussed below). Demographics of the 15 patients included in this report are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of desensitized patients

| Pt. no. | Disease | Gender | Age (years) | Donor relation | HLA MM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1 | AML | F | 51 | Son | Haplotype |

| 2 | AML | F | 40 | Unrelated | HLA-DPB1 allele |

| 3 | AML | F | 53 | Daughter | Haplotype |

| 4 | Myelodysplastic syndrome | M | 64 | Daughter | Haplotype |

| 5 | Myelodysplastic syndrome | F | 49 | Half-sister | Haplotype |

| 6 | Myelodysplastic syndrome | F | 58 | Unrelated | HLA-C, -DRB1, -DQA, -DQB1 alleles |

| 7 | Aplastic anemia | M | 25 | Not Tx'd | |

| 8 | T-cell lymphoma | F | 60 | Son | Haplotype |

| 9 | Hodgkin's lymphoma | F | 30 | Brother | Haplotype |

| 10 | AML | F | 57 | Son | Haplotype |

| 11 | Myelodysplastic syndrome | M | 70 | Niece | Haplotype |

| 12 | Sickle cell anemia | M | 39 | Father | Haplotype |

| 13 | AML | F | 56 | Son | Haplotype |

| 14 | AML | F | 42 | Brother | Haplotype |

| 15 | AML | M | 73 | Daughter | Haplotype |

Abbreviations: MM = mismatch; Tx=transplanted.

Ab evaluation

HLA-specific Abs were defined and their relative levels determined as previously described using both single HLA phenotype (LIFECODES class I ID, LIFECODES class II IDv2; Immuncor, Stamford, CT, USA) and single HLA Ag panel immunoassays (LABScreen Single Ag class I—Combi and LABScreen Single Ag class II Antibody Detection Test—Group 1; One Lambda; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Canoga Park, CA, USA) on the Luminex (Austin, TX, USA) platform.20 To reduce interference in the single Ag assays, euglobulins were depleted from test sera by hypotonic dialysis.26 The relative DSA levels were based on correlations of the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values with CDC XM or FCXM tests, as well as with actual donor XMs.27 Reactions in the immunoassays with MFI values > 1000 were considered positive. Although the reactivity ranges for different Ab specificities varied, in general, MFI values ⩾ 5000 in the phenotype panels and values ⩾ 10 000–15 000 in single Ag assays were consistent with a positive FCXM. MFI values ⩾ 10 000 in the phenotype panels and ⩾ 10 000 when tested at a 1:8 dilution in single Ag assays correlated with positive CDC XMs. Higher thresholds were used with Abs to HLA-C, -DQ and-DP Ags as the solid-phase assays are enhanced for detection of these specificities. Pre- and post-PP samples were tested to monitor both the effect of desensitization in reducing DSA levels and whether there was any Ab rebound between treatments. The pre-PP level on day − 1 was evaluated to determine if there had been any substantial rebound during the conditioning interval. Post-transplant Ab monitoring was performed on post-transplant days +3 and +5, as needed for DSA rebounds, and then on days +7, +14 and +30. To control for day-to-day variation in the solid-phase assays and to determine the percentage increase or decrease in Ab levels, the MFI values were normalized as a ratio to the positive control values in each assay.

Conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis and desensitization regimens The conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis and desensitization regimens were as described previously.20 Briefly, the non-myeloablative conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis consisted of: Cy (14.5 mg/kg per day) days − 6 and − 5, fludarabine (30 mg/m per day) days − 5 through − 2, TBI (200 cGy) day − 1, day 0 infusion of an unmanipulated BM graft (target 4.0 × 108 nucleated cells per kg recipient ideal body weight), CY (50 mg/kg) days +3 and +4, mycophenolate mofetil days +5 through +35, tacrolimus days +5 through day +180 and filgrastim (5 μg/kg per day) day +5 through neutrophil recovery (> 1000 /μL).

The desensitization treatment consisted of alternate-day, single volume PP followed by IVIG (100 mg/kg), tacrolimus (1 mg, i.v. per day) and mycophenolate mofetil (1g two times daily) starting 1–2 weeks before the beginning of BMT conditioning, depending on each patient's starting DSA levels.20 The number of PP/IVIG treatments planned for each patient was based on experience with desensitization of renal transplant candidates at the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center.28 The number of PP/IVIG treatments was estimated based on the starting donor-specific Ab levels correlated with flow cytometric or CDC XM tests (Table 2). Additional risk factors that were considered in determining the extent of desensitization included the presence of multiple DSAs; the presence of any HLA mismatch repeated from a previous transplant; a child-to-mother transplant; and if the relative DSA level was increasing before the initiation of treatment. As PP could not be given during the pretransplant conditioning or with the post-transplant CY on days +3 and +4, treatments were given before conditioning with one additional treatment on the day before infusion. For patients with only low-level DSA below that which could be detected in an FCXM, one PP/IVIG treatment was given on day − 1. A total of four to five treatments were planned for patients with Abs at FCXM+ levels, and three to four treatments were performed before conditioning, with an additional treatment on day − 1. Additional treatments for patients with starting FCXM+ levels were prospectively planned on days 1 and 2 and canceled if not needed based on DSA levels on day − 1. A minimum of five to six treatments was scheduled for patients with DSA at CDC XM+ levels, with additional treatments on day − 1, and on days +1 and +2. For patients with CDC XM titers > 4 (log base 2), desensitization was not undertaken and other therapy options were considered.

Table 2.

General guidelines for desensitization for BMT

| DSA/XM strengtha | Number of PP/IVIG treatments | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Preconditioning | Day −1b | Day +1, +2 | |

|

| |||

| Low-level DSA+, FCXM− | 0 | 1 | If needed, based on day −1 DSA levelc |

| CDC XM−, FCXM+ | 3–4 | 1 | Day +1; day +2 if needed, based on day −1 DSA leveld |

| CDC XM titer 1–4 | 5–6 | 1 | Day +1 and day +2; recommend monitoring DSA level on days +3 and +5e |

| CDC XM HLA class I titer ⩾ 8 | Consider other options | ||

| CDC XM HLA class II DSA ⩾ 1 | |||

Abbreviations: CDC XM=complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch; DSA=donor HLA-specific Ab; FCXM=flow cytometric crossmatch; PP/IVIG=plasmapheresis and i.v. Ig treatments; XM=crossmatch.

It is recommended that the relative DSA strength be based on actual XM tests correlated with results from solid-phase immunoassays. Higher immunoassay thresholds may be required for Abs to HLA-C, -DQB1 and -DPB1 Ags.

The relative Ab level on day −1 should be monitored for all patients to determine the extent, if any, of rebound during the conditioning interval.

Slight DSA increases that remain below an FCXM+ level may not require any post-BMT treatment, whereas increases approaching or consistent with an FCXM+ level may require treatments on day +1 and day +2, respectively.

Post-BMT PP/IVIG treatments should be considered for patients with DSA at either FCXM or CDC XM levels as higher starting levels may be less responsive to desensitization and may be more likely to experience a substantial rebound during the conditioning period.

For patients with starting DSA at a CDC XM+ level, monitoring on day +3 and day +5 is recommended to determine if any further intervention is needed.

The DSA levels were monitored during desensitization to ensure sufficient DSA reduction before the initiation of pre-BMT conditioning. The number of treatments before active conditioning was extended in one case because of a delay in donor availability and in another case because of the patient's clinical status. For patients experiencing an increase or rebound of DSA on day − 1, if not already prospectively scheduled, one to two additional PP/IVIG treatments were scheduled on day +1 and day +2 depending on the extent of the DSA increase; that is, for DSA rebounds approaching or reaching FCXM levels, one or two additional PP/IVIG treatments were planned and additional monitoring was performed on days +3 and +5 to determine if additional post-BMT treatments were needed. If there was only a modest increase with the DSA remaining well below flow cytometric detectability, no further treatment was given.

Engraftment monitoring

Engraftment was evaluated at days +30, +60 and +180 via microsatellite PCR detection of PB chimerism for both total leukocyte and sorted T lymphocytes. Mixed donor chimerism was defined as ⩾ 5%, but < 95%, donor. Full donor chimerism was defined as ⩾ 95% donor.

RESULTS

The DSA specificity, starting levels and percentage of DSA reduction following desensitization are given in Table 3 for the 15 patients included in this report. The first nine patients were previously reported and all had pretreatment DSA at XM+ levels.20 Of the additional six patients treated, three had FCXM+ DSA levels (patient nos. 10, 13 and 14). The three other patients had DSA below a positive FCXM level, but were given one PP/IVIG treatment on transplant day − 1 because of other risk factors, including a rise in the DSA level before the initiation of desensitization for two patients (nos.12 and 13) and the presence of multiple, low-level DSA in the other patient (no. 10). Substantial DSA reduction was achieved in all 15 patients by the end of the desensitization regimen, with a mean reduction of 64.4% and individual reductions ranging from 33.1 to 93.9%. In the 14 of 15 patients transplanted, there was a further reduction in DSA post BMT, with a mean reduction of 85.5% at last follow-up (range = 59–99.9%). There was only one patient (no. 7) for whom desensitization failed to reduce the DSA to a level that was thought to be safe for BMT. This patient had the highest starting level of DSA, CDC XM+ with a titer of eight before desensitization. Despite a 64.7% reduction from starting levels and three additional PP/IVIG treatments, the DSA remained at an FCXM+ level. As this patient was to receive full myeloablation, the transplant was canceled.

Table 3.

Reduction of DSA through desensitization

| Pt. no. | No. of PP/IVIG | DSA HLA specificity | Additional risk factors | Pretreatment DSA level | % DSA reduction end of PP | % DSA reduction F/U | DSA levelbF/U | Time of DSA F/U (mos.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 7 | B7 | Child to mother | vFCXM+ | 93.9 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2 | 5 | DPI | vFCXM+ | 59.5 | 93.8 | Neg | 12 | |

| 3 | 3 | A2 | Child to mother | vFCXM+ | 33.1 | 96.0 | Neg | 6 |

| 4 | 3 | DR13, DR52, DQ6 | Multiple DSA | FCXM+ | 86.0 | 99.1 | Neg | 7 |

| 5 | 5 | DR16 | FCXM+ | 52.1 | 96.9 | Neg | 1 | |

| 6 | 4 | DQ4 | FCXM+ | 44.3 | 73.0 | Neg | 6 | |

| 7 | 7 | A2 | DSA level | CDC XM+ | 64.7 | Not Tx | Neg | 6 |

| 8 | 3 | A3, B27 | Multiple DSA | FCXM+ | 74.0 | 99.9 | Neg | 2 |

| 9 | 11 | DR4, DR53 | Repeat mismatches | FCXM+ | 77.4 | 98.4 | Neg | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | A2, Cw4, B35 | Multiple DSA | FCXM− | 41.2 | 95.1 | Neg | 1 |

| 11 | 4 | A1, B8 | Multiple DSA | FCXM+ | 92.4 | 98.3 | Neg | 1 |

| 12 | 1 | A68 | DSA increasea | FCXM− | 65.1 | 75.6 | Neg | 1 |

| 13 | 10 | A26, DP2 | FCXM+ | 52.4 | 62.7 | Low Level | 3 | |

| 14 | 6 | B51, Cw15 | FCXM+ | 40.2 | 59.0 | Low Level | 2 | |

| 15 | 1 | B37 | DSA increasea | FCXM− | 51.5 | 91.7 | Low Level | 1 |

| Mean | 64.4 | 85.5 | ||||||

| SD | 15.7 | 14.4 | ||||||

Abbreviations: CDC XM=complement-dependent cytotoxicity crossmatch; DSA=donor HLA-specific Ab; FCXM=flow cytometric XM; F/U=follow-up; MFI, median fluorescence values; ND=not done; PP/IVIG=plasmapheresis and i.v. Ig treatments; Tx=transplanted; vFCXM=DSA levels consistent with a positive FCXM; XM=crossmatch.

To control for interassay variation, the MFIs were expressed as a ratio to the positive control value in each assay. The percentage of Ab reduction from the pretreatment level was determined using these normalized values. Patient no. 7 was not transplanted as desensitization did not reduce the DSA below a positive FCXM level.

The DSA increase was before the initiation of desensitization.

The relative DSA level at last follow-up Ab testing is given. Neg= DSA that was undetectable or below the level considered positive; low level=MFI values for DSA were well below a level consistent with a positive FCXM, that is, MFI <3000 for HLA-A, -B and -DR Ags, with higher values for HLA-C, -DQ and -DP.

DSA levels in pre-PP samples were monitored on days − 7 and − 1 to determine the occurrence of any substantial increases in DSA during the conditioning period when no PP/IVIG treatments were given. The results of the Ab testing for the 11 patients who received more than one PP/IVIG treatment are given in Table 4. Five patients (nos. 2, 4, 8, 11 and 14) had no DSA rebound during the conditioning interval and, in fact, demonstrated some additional decrease in the relative DSA level. For three of these patients (nos. 8, 11 and 14), the decreases resulted in a lower relative FCXM level than was present on day − 7 when the conditioning was started. Four patients (nos. 1, 3, 5 and 6) experienced some increase in their DSA during conditioning. In these four cases, the DSA had been substantially reduced by the treatments before conditioning and the observed increases did not alter the relative FCXM level from that present on day − 7. Two patients (nos. 9 and13) experienced substantial DSA rebounds during the conditioning interval, resulting in relative DSA levels consistent with a positive FCXM. Among the six patients who experienced any DSA increase, all were parous females, in comparison with the five patients with no DSA rebound, among whom two were parous females.

Table 4.

Changes in DSA levels during the conditioning period

| Patient no. | Porous female | Donor | DSA specificity | Change in DSA levela | Relative DSA level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Day −7 | Day −1 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 2 | No | Unrelated | DPI | Slight decrease | <FCXM | <FCXM |

| 4 | No | Child | DR13, DR52 | Decrease | <<FCXM | <<FCXM |

| 8 | Yes | Child | A3, B27, Cw4 | Decrease | <FCXM | <<FCXM |

| 11 | No | Niece | A1, B8 | Slight decrease | <FCXM | <<FCXM |

| 14 | Yes | Brother | Cw5, B51 | Decrease | +FCXM | ±FCXM |

| 1 | Yes | Child | B7 | Slight increase | <<FCXM | <<FCXM |

| 3 | Yes | Child | A2 | Slight increase | ±FCXM | ±FCXM |

| 5 | Yes | Half-sister | DR16 | Increase | ±FCXM | ±FCXM |

| 6 | Yes | Unrelated | DQ4 | Slight increase | <FCXM | <FCXM |

| 9 | Yes | Brother | DR4, DR53 | Substantial increase | <FCXM | +FCXM |

| 13 | Yes | Child | A26, DP2 | Substantial increase | ±FCXM | +FCXM |

Abbreviations: DSA=donor HLA-specific Ab; FCXM=flow cytometric crossmatch; <FCXM=below a positive FCXM; ⪡FCXM=well below a positive FCXM, but still at a level considered positive; ±FCXM=borderline positive FCXM levels; +FCXM=levels sufficient to yield a positive FCXM.

The changes in DSA levels were analyzed by comparison of the normalized results of solid-phase immunoassay tests for preplasmapheresis samples obtained on day −7 before the initiation of the pretransplant conditioning and on day −1 before HSCT. The relative DSA levels indicate whether or not the DSA levels would correspond to positive or negative FCXM results.

The slight increases and decreases in DSA levels were not sufficient to change the relative Ab strength.

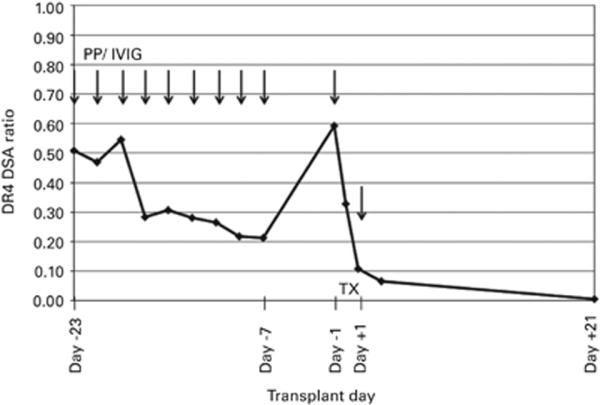

The Ab trends and responses to desensitization for the two cases with substantial rebounds are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. In the first case, patient no. 9 had DSA to two HLA class II mismatches, HLA-DR4 and -DR53, with her haploidentical donor. Both of these Ags were repeated mismatches with a BMT performed a year earlier using marrow from another related donor. Before treatment, the DSA to HLA-DR4 was at a FCXM+ level, whereas the DR53 Ab was at a relatively low level. Three PP/IVIG treatments before conditioning and one treatment on day − 1 were planned. The course of the strongest DSA to HLA-DR4 is shown in Figure 1. Owing to rebounds of the DR4 DSA between the first three treatments, additional treatments were scheduled. The DSA was reduced following the third treatment, but some rebounding continued following treatments four to six, with a gradual decrease to a level consistent with a negative FCXM achieved after nine treatments. During the conditioning interval, the DSA increased by 86.8% to a level slightly higher than before treatment; however, following the day − 1 treatment, the BMT and one additional treatment on post-transplant day +1, the DSA levels were well below that associated with a positive FCXM. By day +21, the DSA to both DR4 and DR53 were negative in the solid-phase immunoassays.

Figure 1.

The desensitization course for patient no. 9 who had DSA to HLA-DR4 and -DR53. Arrows indicate the timing and number of PP/IVIG treatments. The course of the strongest DSA to HLA-DR4 is given as a ratio of the MFI values normalized to the positive control to account for the day-to-day variation in the solid-phase immunoassays.

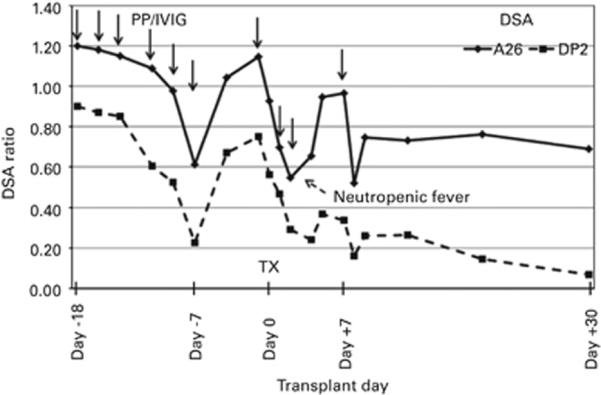

Figure 2.

The desensitization course for patient no. 13 who had DSA to HLA-A26 and -DP2. The trend of the DSA to HLA-A26 is illustrated by the solid line and the DSA to HLA-DP2 is shown as a dashed line. The DSA values are given as ratios of the MFI values normalized to their respective positive controls. The solid arrows indicate the timing and number of PP/IVIG treatments and the dashed arrow indicates when the patient experienced a neutropenic fever.

The course of patient no. 13 was complicated by a delay in the start of conditioning due to the patient's clinical status. Because desensitization had been started, treatments were scheduled to continue until the patient was clinically stable (Figure 2). During this time, gradual decreases in both the DSA to HLA-A26 and -DP2 were observed. A substantial rebound in both DSAs occurred during the conditioning interval, for which two post-BMT desensitization treatments were scheduled on post-transplant days +1 and +2. Following these treatments and the infusion of the BMT, the DSA levels on day +2 were well below those corresponding to a positive FCXM. However, another substantial DSA rebound was noted on days +4 and +5 following development of a neutropenic fever. One additional PP/IVIG treatment was given on day +7. There was a slight DSA rebound following this treatment, but not to positive FCXM levels. By day +30, the DSA to HLA-DP2 had decreased to levels considered negative, whereas the DSA to HLA-A26 remained positive, but at a level below that consistent with a positive FCXM.

The post-BMT status of the 14 patients transplanted following desensitization is summarized in Table 5. All fourteen had engrafted by post-transplant day +60. Four patients experienced grade 1 GVHD with skin involvement. Despite initial engraftment, seven patients suffered relapses of their underlying diseases from 3 to 12 months after transplantation. All of these patients subsequently succumbed to their relapsed disease. Two other patients died from infections and one from a non-transplant-related cause. Four patients remain disease free at a range of 1–3.9 years after BMT. The small numbers of patients, and their disease heterogeneity, preclude any comparison of these outcome data with our much larger group of patients who were transplanted without DSA.

Table 5.

Post-BMT clinical status

| Pt. no. | Disease | Donor chimerism day +60 % donor | GVHD | Disease relapse | F/U time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unsorted PBL | CD3+ PBL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 1 | AML | 100 | 100 | No | No | 3.9 Years |

| 2 | AML | 94 | NT | No | 3 Mos. | Died: 17 mos. |

| 3 | AML | >95 | 100 | No | 5 Mos. | Died: 7 mos. |

| 4 | MDS | 100 | 100 | Grade 1 skin | No | Died: 2.3 years viral pneumonia |

| 5 | MDS | 100 | 100 | Grade 1 skin | 12 Mos. | Died: 18 mos. |

| 6 | MDS | 100 | 100 | No | 16 mos. | Died: 20 mos. |

| 8 | T-cell lymphoma | 100 | 100 | Grade 1 skin | No | Died: 1.1 years hepatitis C |

| 9 | Hodgkin's lymphoma | >95 | <5 | No | No | 2.1 Years |

| 10 | AML | >95 | 100 | No | 4 Mos. | Died |

| 11 | MDS | >95 | 100 | No | No | Died non-transplant related |

| 12 | SS | 94 | <5 | No | No | 1.5 Years |

| 13 | AML | >95 | 100 | No | 4 Mos. | Died: 4.3 mos. |

| 14 | AML | 100 | <5 | No | No | 1 Year |

| 15 | AML | 100 | 100 | Grade 1 skin | 4 Mos. | Died: 4 mos. |

Abbreviations: MDS=myelodysplastic syndrome; SS=sickle cell disease; NT=not tested.

DISCUSSION

Our results and those from other centers indicate that desensitization methods can reduce DSA to levels that permit successful T-cell engraftment after reduced intensity conditioning.9,15,20–24 The key requirement appears to be sufficient reduction of DSA to prevent Ab-mediated destruction of donor cells before they can engraft. Among the different desensitization regimens, combinations of PP with rituximab and/or IVIG have been most often used and have demonstrated successful DSA reduction.9,15,20–22 Treatment with high-dose IVIG alone was not very effective in the one BMT patient in whom it has been tried,23 and it has been shown not to impact high levels of Abs in renal transplant candidates.29 The proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, to date, has only been tried in one BMT candidate with minimal DSA reduction.9 In studies of renal transplants, preconditioning with bortezomib was found to affect only small, transient changes in Ab levels.30 The time frame needed for bortezomib-induced Ab reduction, a median of 1.5 months,31 may also be prohibitive for patients in urgent need of BMT. Further, bortezomib, in our experience with renal transplants, is not very effective against Ab to HLA class II Ags.32 Norlander et al.22 tried increasing the cell dose by using two umbilical cord blood stem cell units, which raises the question of whether larger cell numbers that might be achieved with mobilized PBSC might be used to overcome DSA. The experience of Yoshihara et al.9 with platelet adsorption9 supports this concept; however, whether or not increased donor cell numbers could overcome DSA likely would depend on the starting DSA levels. For patients with high DSA levels, that is, XM-positive levels, some desensitization would likely be needed even if a larger graft could be given.

The number of patients desensitized to date is too small to permit development of specific guidelines for successful treatment; however, from our experience, certain factors should be considered. The failure to reduce the DSA sufficiently in patient no. 7, whose pretreatment DSA level was at a titer of eight in a CDC XM, suggests that desensitization may be best attempted in candidates with lower starting DSA levels. Mismatches repeated in a second transplant to which the patient had developed DSA likely contributed to the difficulty encountered in reducing the DSA to HLA-DR4 for patient no. 9. Sensitization to the previous mismatches also was a probable cause of the substantial rebound of the DR4 DSA during the conditioning interval when the PP/IVIG treatments were discontinued. Ab specificity to different HLA Ag classes may be another factor for consideration as in the case of patient no. 6 with DSA to an HLA-DQ4 mismatch. Desensitization for this patient resulted in only a 44.3% reduction at the end of the PP/IVIG treatments and only by 73% post-BMT. Experience at the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center with desensitization for renal transplantation supports these observations, as factors associated with poorer responses to desensitization include starting levels of DSA consistent with positive CDC XM tests and the HLA class specificity of the Abs with the elimination of DSA correlating to the expression of the target Ags: class I>DR/DQ>DR51, 52 and 53.33 Drawing from our experience with both BMT and renal desensitization, the presence of low-level DSA to multiple Ags and increasing Ab levels before desensitization should also be considered as risk factors.

The two patients who experienced substantial DSA rebounds during the conditioning period emphasize the importance of monitoring Ab levels. In both cases, recognition of the DSA rebound prompted the addition of post-BMT treatment to help lower the DSA to a level permissive for engraftment. For patient no. 13, a second rebound of DSA was noted beginning on day +4 and increasing in level by day +5. This second DSA increase occurred after the patient developed a neutropenic fever, which is consistent with increases in HLA Abs provoked by infections and other proinflammatory events.34 The course of patient no. 13 also illustrates the value of post-BMT Ab monitoring as, while the DSA to HLA-DP2 was effectively eliminated, the DSA to the HLA-A26 Ag persisted at a low level. The observation that all of the six patients who experienced some degree of DSA rebound during conditioning were parous females is consistent with higher degrees of sensitization among these patients.20 As sensitization from pregnancy can result in not only humoral but also cellular sensitization, child-to-mother BMT should be considered as a potential risk factor.

While certain factors that may influence responses to desensitization can be identified, the exquisite sensitivity of current immunoassays has raised the question of what level of DSA is permissible for BMT. Our approach has been to reduce the DSA to a level well below that which would be detectable in a FCXM and this has permitted successful engraftment using our desensitization, conditioning and post-BMT immunosuppression regimens. From an ongoing retrospective review of 213 cases transplanted at our center with partially HLA-mismatched donors, 22 patients were transplanted in the presence of low levels of DSA without any desensitization intervention. Among these 22 patients, 19/22 (86.4%) had full engraftment by day +60 compared with 170/191 (89%) of DSA-negative patients (unpublished data). Although the results from both of our studies suggest that intervention may not be necessary for low levels of DSA, there is no clear definition of a `safe' DSA level that may be applicable to other desensitization regimens. The thresholds for what Ab level is considered positive vary considerably among published reports, making it difficult to determine what defines a permissible level in other studies. The impact of DSA on longer-term outcomes also remains to be determined. Both increased rates of disease relapse and reduced OS have been associated with the presence of DSA in studies among recipients of umbilical cord blood stem cells.18,19,35 In our series of 14 patients who were successfully desensitized and received allogeneic BM grafts, half suffered relapses of their underlying diseases despite achieving initial donor engraftment. Although infection can be a complication of PP, there were no infections complicating the post-transplant course among our patients whose disease relapsed; however, it is possible that the post transplant immunosuppression may have been a factor in these relapses. It should be noted that none of these patients had any other donor options that would have avoided DSA, and all but two of the relapsed patients had essentially cleared their DSA before their relapse. Whether or not the relapse rate among our patients is excessively high cannot be determined with such small numbers, and the influence of DSA on potential relapse and OS remains an open question. Both the criteria for defining acceptable levels of DSA and the long-term impact of the presence of any level of DSA clearly needs to be addressed in future and larger studies.

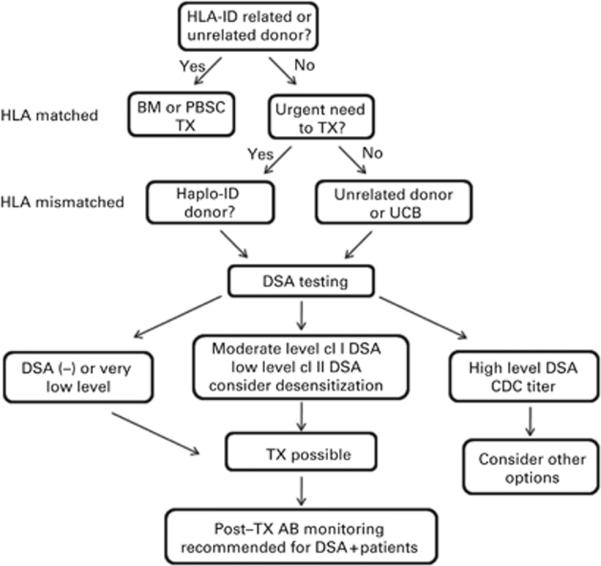

Although it is clear that our desensitization regimen can facilitate engraftment in sensitized recipients, it should be reserved for candidates with no donors to whom there is no DSA. Our approach to evaluating candidate treatment options is illustrated in Figure 3. An HLA-identical related donor or a fully matched unrelated donor remain as preferable choices, but as the majority of patients lack a well-matched donor, partially mismatched related or unrelated donors are evaluated. Unrelated donor and/or cord blood units may be considered if the patient's clinical status permits the time required for registry searches. HLA-haploidentical donors offer two distinct advantages—ready availability and often multiple donor possibilities, which may, in many cases, allow selection of a potential donor to whom there is no DSA. Determination of the relative DSA levels is used to (1) evaluate the likelihood of successful desensitization and (2) to estimate the extent of treatment needed. It is highly recommended that estimates of DSA levels derived from immunoassays be confirmed with cell-based XM tests because current immunoassays for HLA Abs are at best only semiquantitative and are subject to inherent variability.27,36 As there are no algorithms to evaluate the collective strength of multiple Abs, actual XM tests also provide the best measure of relative DSA strength when two or more, low-level DSA are present. Desensitization is considered for candidates with moderate levels of HLA class I-specific Ab, that is, levels ranging from borderline FCXM positive to low-titer CDC XM positive. Because we have found HLA class II Abs to be less responsive to desensitization,33 a lower threshold is used for these Abs. Generally, no desensitization is required for patients with low levels of DSA, that is, levels well below those associated with a positive FCXM; however, as previously noted, a single treatment on day − 1 may be considered if there are multiple low-level DSA or if the DSA is noted to be increasing in strength. Desensitization is not considered as an option for any DSA resulting in positive CDC XM at titer >4. Post-transplant Ab monitoring is routinely carried out in the first week post-BMT on days +3, +5 and/or +7 as needed to determine if there has been any DSA rebound that would require intervention. If desensitization is undertaken, good communication among all members of the transplant team, including the clinicians, histocompatibility directors, hemapheresis personnel, nurses and coordinators, is essential to ensure sufficient treatment for adequate DSA reduction. Given these considerations, desensitization can extend the opportunity for BMT to patients who harbor DSA to their only potential donors.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of BMT candidates for desensitization. The algorithm is illustrated for donor selection and evaluation of relative DSA levels for possible desensitization. For patients lacking an HLA fully matched donor, partially mismatched haploidentical, unrelated registry donors or umbilical cord blood units become options. Whether desensitization is considered is based on the DSA level. Moderate levels of DSA to HLA class I Ags can range from borderline FCXM positive to low-titer CDC XM positive. Lower thresholds are used for DSA to HLA class II Ags, generally no more than FCXM positive. Low levels of DSA are below a positive FCXM. CDC = complement-dependent cytotoxicity; DSA = donor HLA-specific antibody; TX = transplant.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kekre N, Antin JH. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation donor sources in the 21st century: choosing the ideal donor when a perfect match does not exist. Blood. 2014;124:334–343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-514760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs E, O'Donnell PV, Brunstein CG. Alternative transplant donor sources: Is there any consensus? Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:173–179. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835d815f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciurea SO, Champlin RE. Donor selection in T cell-replete haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: knowns, unkowns, and controversies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler C, Ballen KK. Improving outcomes in umbilical cord blood transplantation: state of the art. Blood Rev. 2012;26:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale GA, Shrestha S, Le-Rademacher J, Burns LJ, Gibson J, Inwards DJ, et al. Alternate donor hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in non-Hodgkin lymphoma using lower intensity conditioning: a report from the CIBMTR. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luznik L, O'Donnell PV, Symons HJ, Chen AR, Leffell MS, Zahurak M, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasamon YL, Luznik L, Leffell MS, Kowalski J, Tsai HL, Bolanos-Meade J, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand A, Doxiadis IN, Roelen DL. On the role of HLA antibodies in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 2013;81:1–11. doi: 10.1111/tan.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara S, Maruya E, Taniguchi K, Kaida K, Kato R, Inoue T, et al. Risk and prevention of graft failure in patients with preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies undergoing unmanipulated haploidentical SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:508–515. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Vina MA, de Lima M, Ciurea SO. Humoral sensitization matters in CBT outcome. Blood. 2011;118:6482–6484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-382630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciurea SO, Thall PF, Wang X, Wang SA, Hu Y, Cano P, et al. Donor-specific anti-HLA Abs and graft failure in matched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:5957–5964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-362111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fancosi D, Zucca A, Scatena F. The role of anti-HLA antibodies in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1585–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler C, Kim HT, Sun L, Sese D, Glotzbecker B, Armand P, et al. Donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies predict outcome in double umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:6691–6697. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spellman S, Bray R, Ronsen-Bronsen S, Haagenson M, Klein J, Flesh S, et al. The detection of donor-directed, HLA-specific alloantibodies in recipients of unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation is predictive of graft failure. Blood. 2010;115:2704–2708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciurea SO. High risk of graft failure in patients with anti-HLA antibodies undergoing haploidentical stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1019–1024. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b9d710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anasetti C, Amos D, Beatty PG, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger W, Buckner CD, et al. Effect of HLA compatibility on engraftment of bone marrow transplants in patients with leukemia or lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:197–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901263200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunstein CG, Noreen H, DeFor TE, Maurer D, Miller JS, Wagner JE. Anti-HLA antibodies in double umbilical cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1704–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansari M, Uppugunduri CR, Ferrari-Lacraz S, Bittencourt H, Gumy-Pause F, Chalandon Y, et al. The clinical relevance of pre-formed anti-HLA and anti-MICA antibodies after cord blood transplantation in children. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggeri A, Rocha V, Masson E, Labopin M, Cunha R, Absi L, et al. Impact of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies on graft failure and survival after reduced intensity conditioning-unrelated cord blood transplantation: a Eurocord, Société Franco-phone d'Histocompatibilité et d'Immunogénétique (SFHI) and Société Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire (SFGM-TC) analysis. Haematologica. 2013;98:1154–1160. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.077685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gladstone DE, Zachary AA, Fuchs EJ, Luznik YL, King KE, et al. Partially mismatched transplantation and human leukocyte antigen donor-specific antibodies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa LJ, Moussa O, Bray RA, Stuart RK. Overcoming HLA-DPB1 donor specific antibody-mediated hematopoietic graft failure. Br J Haematol. 2010;151:84–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norlander A, Uhlin M, Ringden O, Kumlien G, Hausenberger D, Mattsson J. Immune modulation to prevent antibody-mediated rejection after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplant Immunol. 2011;25:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishiyama K, Anzai N, Tashima M, Hayashi K, Saji H. Rapid hematopoietic recovery with high levels of DSA in an unmanipulated haploidentical transplant patient. Transplantation. 2013;95:e76–e77. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318293fcda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zachary AA, Leffell MS. Desensitization for solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunol Rev. 2014;258:183–207. doi: 10.1111/imr.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, Kraus ES, Kucirka LM, Locke JE, et al. Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:318–328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zachary AA, Lucas DP, Detrick B, Leffell MS. Naturally occurring interference in Luminex assays for HLA-specific antibodies: characteristics and resolution. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zachary AA, Sholander JT, Houp JA, Leffell MS. Using real data for a virtual crossmatch. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:574–579. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery RA, Zachary AA. Transplanting patients with a positive donor-specific crossmatch: a single center's perspective. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alachkar N, Lonze BE, Zachary AA, Holechek MJ, Schillinger K, Cameron AM, et al. Infusion of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin fails to lower the strength of human leukocyte antigen antibodies in highly sensitized patients. Transplantation. 2012;94:165–171. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318253f7b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guthoff M, Schmid-Horch B, Wiesel KC, Häring HU, Königsrainer A, Heyne M. Proteasome inhibition by bortezomib: effect on HLA-antibody levels and speci-ficity in sensitized patients awaiting renal allograft transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2012;26:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everly MJ, Terasaki PI, Trivedi HL. Durability of antibody removal following proteasome inhibitor-based therapy. Transplantation. 2012;93:572–577. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824612df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philogene MC, Sikorski P, Montgomery RA, Leffell MS, Zachary AA. Differential effect of bortezomib on HLA class I and class II antibody. Transplantation. 2014;98:660–665. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zachary AA, Montgomery RA, Leffell MS. Factors associated with and predictive of persistence of donor-specific antibody after treatment with plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Locke JE, Zachary AA, Warren DS, Segev DL, Houp JA, Montgomery RA, et al. Proinflammatory events are associated with significant increases in breadth and strength of HLA-specific antibody. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2136–2139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takanashi M, Atsuta Y, Fujiwara K, Kodo H, Kai S, Sato H, et al. The impact of anti-HLA antibodies on unrelated cord blood transplantations. Blood. 2010;116:2839–2846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tait BD, Sűsal C, Gebel HM, Nickerson PW, Zachary AA, Claas FH, et al. Consensus guidelines on the testing and clinical management issues associated with HLA and non-HLA antibodies in transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:19–47. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827a19cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]