Summary

LIGHT (homologous to lymphotoxins, inducible expression, competes with herpesvirus glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator, a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily that contributes to the regulation of immune responses. LIGHT can influence T-cell activation both directly and indirectly by engagement of various receptors that are expressed on T cells and on other types of cells. LIGHT, LIGHT receptors, and their related binding partners constitute a complicated molecular network in the regulation of various processes. The molecular cross-talk among LIGHT and its related molecules presents challenges and opportunities for us to study and to understand the full extent of the LIGHT function. Previous research from genetic and functional studies has demonstrated that dysregulation of LIGHT expression can result in the disturbance of T-cell homeostasis and activation, changing the ability of self-tolerance and of the control of infection. Meanwhile, blockade of LIGHT activity can ameliorate the severity of various T-cell-mediated diseases. These observations indicate the importance of LIGHT and its involvement in many physiological and pathological conditions. Understanding LIGHT interactions offers promising new therapeutic strategies that target LIGHT-engaged pathways to fight against cancer and various infectious diseases.

Keywords: cytokines, autoimmune disease, T cells, TNF superfamily

Introduction

The immune system contains innate and adaptive components that cooperate to initiate, promote, and regulate host defenses against infection. The adaptive immune system provides immunity through antigen-specific receptors that are expressed on T cells and B cells. It is generally believed that adaptive immune cell activation requires at least two signals (1, 2), where signal 1 is delivered by binding antigen receptors with cognate antigens and signal 2 is delivered by cosignaling molecules. This regulation controls the extent, quality, and duration of lymphocyte activation. Among these cosignaling molecules, costimulatory or coinhibitory molecules either positively or negatively contribute, respectively, to the overall outcome of the stimulation. The co-existence of costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules highlights the importance of the quantitative and qualitative control of lymphocyte activation for the host to discriminate self versus non-self. LIGHT [homologous to lymphotoxins, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D (gD) for herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes] is recognized as one of the costimulatory molecules that can regulate T-cell activation. Despite extensive studies over the last decade, the LIGHT molecule and its complex ligand-receptor inter-connection network (Fig. 1) remain to be more fully explored.

Fig. 1. LIGHT-involved molecular network.

Lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) binds to both membrane LTα1/β2 and LIGHT [homologous to lymphotoxins, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes] (membrane or soluble). HVEM binds to membrane or soluble LIGHT, soluble LTα3, B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), and CD160. Membrane or soluble LIGHT can bind to LTβR, HVEM, and decoy receptor 3 (DcR3). Soluble tumor necrosis factor α3 (TNFα3) and LTα3 bind to TNF receptor I (TNFRI) and TNF receptor II (TNFRII). DcR3 might be able to engage reverse signal to membrane LIGHT. Arrow lines indicate the ligand-receptor interactions. Dashed line refers to weak interactions. The cellular distributions of these ligands/receptors are not shown here. The range of interactions could be involved among multiple cells.

LIGHT-involved molecular network

Human and mouse LIGHT cDNA clones were published in 2000 and 1998, respectively (3–5). LIGHT belongs to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, and it can bind to at least two receptors: HVEM and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR). Those two receptors are promiscuous in their binding partners: LTβR can also bind to membrane lymphotoxin (LTα1β2), and HVEM can also bind to soluble lymphotoxin (LTα3). The binding of soluble lymphotoxin LTα3 to HVEM is relatively weak, and the biological significance of this binding is still under debate. Soluble lymphotoxin LTα3 and TNF are also promiscuous and can bind to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2 (6). In the human system, LIGHT can interact with a third receptor, soluble decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) (7), that also binds to other molecules such as Fas ligand (FasL), TNF ligand-related molecule 1A (TL1A), and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (7–9). No mouse DcR3 homolog has been found. Later studies further revealed that HVEM can also act as a ligand to deliver negative signals through B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) (10, 11). In human, HVEM can activate another cell surface molecule, CD160, on CD4+ T cells to transduce negative signal (12); whether this is the case in mouse awaits confirmation. The possibility that LIGHT can also act as a receptor to transduce reverse signaling into the T cell for costimulation instead of acting as just a ligand has been raised (13, 14), but this idea still needs further investigation. This complicated molecular cross-talk involving LIGHT and its interacting molecules suggests functional redundancy among the LIGHT-related molecules and possible ways to fine-tune immune responses by utilizing various cellular and molecular pathways. Differentiating between these many interactions involving LIGHT and its related molecules presents a challenge to study in a research setting. Recombinant soluble LTβR–immunoglobulin (Ig) fusion protein and HVEM–Ig fusion protein are widely used as dissecting tools for determining the biological functions of LIGHT and its related molecules, but it can be difficult to precisely pinpoint the role of individual molecules by data that have been collected from using LTβR–Ig and HVEM–Ig alone. Specific blocking antibodies for LIGHT will be very helpful for these types of studies.

Molecular and cellular expression

LIGHT can be expressed either in the cytosol or on the cell membrane due to alternative splicing that creates two mRNA isoforms (15). The cell membrane form of LIGHT can be further shed into soluble form by metalloproteinase activity (15, 16). These different forms of LIGHT may impart distinct biological functions. Anand et al. (17) reported that a LIGHT mutant, engineered to be expressed only on the membrane and resistant to shedding, did not promote liver inflammation in a concanavalin A (ConA)-induced mouse hepatitis model. Full-length wildtype (WT) LIGHT secreted through protease digestion, however, was able to strongly increase the pathogenesis of ConA-induced hepatitis (17). The underlying mechanism for these differential functions between soluble and membrane forms of LIGHT remains unclear. In vitro binding studies showed that the membrane form of LIGHT could disrupt the HVEM–BTLA interaction (18), while the soluble form of LIGHT could enhance HVEM–BTLA interaction in a dose-dependent manner (11, 18). Whether and how these changes in interaction influence biological outcomes is under current investigation. Expression of the membrane form of LIGHT within the tumor environment could induce infiltration and activation of lymphocytes inside the tumor, leading to effective eradication of primary and metastatic tumors (19, 20), supporting the notion that the membrane form of LIGHT is sufficient for its effector function. The biological reasons for membrane LIGHT shedding are still a matter of mystery.

LIGHT and its related molecules are broadly expressed on various cell populations including T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, platelets, and B cells (Table 1), indicating the importance of this molecule in regulation and implies diversity in the function of the LIGHT molecule. Resting T cells have low amount of intracellular LIGHT expression; upon T-cell activation, a high amount of LIGHT is found on the cell surface in the membrane-bound form. This process is primarily controlled at the transcriptional level (16, 21), but protein transportation from cytoplasm to cell membrane may also play a role (16). Activated human NK cells also express membrane-bound LIGHT (21), which may be able to promote NK cell function. Immature DCs express membrane-bound LIGHT yet lose this expression upon maturation. This particular pattern of expression on DCs is interesting, as most other costimulatory molecules (such as CD80, CD86) are usually upregulated during DC maturation (22). It has been suggested that the loss of LIGHT expression on mature DCs may be due to cleavage of membrane-bound LIGHT, but this remains to be experimentally tested. Platelets, an important player in hemostasis and thrombosis, can also express LIGHT. Upon platelet activation, LIGHT is released in soluble form and promotes inflammatory responses (23). The release of LIGHT from platelets involves metalloproteinase activity as well as intracellular processes such as actin polymerization. The importance of platelets regulating the release of LIGHT during inflammation awaits further studies. In human rheumatoid arthritis, LIGHT was found to be upregulated on B cells and monocytes that may function to mediate cellular adhesion and metalloproteinase production by synoviocytes (24).

Table 1.

LIGHT and its related molecules cellular expression

| Molecule

|

Cellular Expression

|

|---|---|

| Membrane LIGHT | Activated T cells, immature DCs, activated NK cells, platelet, (activated B cells?) |

| LTβR | Broadly expressed (including hepatocytes, gut epithelial cells, stromal cells in lymphoid tissues, monocytes, DCs etc.). Mature lymphocytes lack expression |

| HVEM | T cells, B cells, NK cells, DCs, myeloid cells, some somatic tissues (including gut epithelial cells) |

| DcR3 | Human tumors and activated monocytes and myeloid-derived DCs |

| BTLA | T cells, B cells, DCs, myeloid cells |

| CD160 | T cells, NKT cells, NK cells |

| Membrane LT | T cells, B cells, NK cells, LTic (lymphoid tissue inducer cells) |

| TNF | Broadly expressed |

| TNFR | TNFR1 expressed on most nucleated cells, TNFRII expressed mostly on hematopoietic cells |

LIGHT, homologous to lymphotoxins, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator, a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes; LTβR, lymphotoxin β receptor; HVEM, herpesvirus entry mediator; DcR3, decoy receptor 3; BTLA, B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, TNF receptor; NK, natural killer.

In terms of the receptors that the LIGHT ligand interacts with, LTβR expression is broad and includes both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells, while HVEM is broadly expressed in the hematopoietic lymphoid and myeloid compartment. In terms of lymphocyte expression, mature lymphocytes lack LTβR expression (25, 26), while HVEM is found on naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and is decreased during T-cell activation with expression restored by the end of activation (16, 27). As mature T cells do not express LTβR, the activation of T cells by LIGHT is generally thought to be through HVEM, although this process has yet to be tested experimentally in vivo. Interestingly and contrary to the predicted outcome based upon the LIGHT–HVEM costimulatory interaction, HVEM-deficient T cells demonstrate hyper-responsiveness following stimulation with anti-CD3 antibodies or ConA (28). A dominant inhibitory interaction between HVEM–BTLA is our current hypothesis to explain this unexpected observation (10, 28), but further studies are needed to confirm or refute this idea.

A third receptor for LIGHT, soluble DcR3, is highly expressed by a number of human tumor cells as well as by human monocytes and myeloid derived DCs during bacterial infection (29, 30). While DcR3 can block LIGHT interaction with HVEM and LTβR (31), it may also be able to activate LIGHT to transduce reverse signaling (13).

Structural features

LIGHT contains a C-terminal TNF homology domain (THD), a 150 amino acid long sequence containing a conserved framework of aromatic and hydrophobic residues, folding into a β-sandwich structure with two stacked β-pleated sheets, each formed by five anti-parallel β strands that adopt a classical ‘jelly-roll’ topology (32). The THDs associate to form trimetric LIGHT. Indeed, recombinant LIGHT that contains only extracellular regions bind together to form a homotrimer complex (33).

The LIGHT receptors LTβR, HVEM, and DcR3 are all TNFR family members, with their extracellular regions containing cysteine-rich domains (CRDs). CRDs are pseudo-repeats typically containing six cysteine residues engaged in the formation of three disulfide bonds. LTβR and DcR3 both contain four CRDs, while HVEM contains three CRDs and one non-typical CRD that contains only two disulfide bonds.

The THDs of TNF family members typically bind to CRDs of the correlated TNFR family members. Mutation studies and molecular modeling predict that LIGHT contacts HVEM through the CRD2–CRD3 region (33). Changing a single amino acid at position 119 (G → E) in human LIGHT disrupted LIGHT–HVEM binding but did not affect its binding to LTβR. Changing the residue at 174 (Y → F), however, affected binding to both receptors (33). These LIGHT mutants have been useful in dissecting which receptors are involved in LIGHT-mediated processes.

The CDR1 region of HVEM is responsible for the interaction with BTLA and CD160 (10, 12, 18). HSV envelope protein gD binds HVEM through the CRD1 region and three residues of the CRD2 region (34). Thus, gD can competitively block HVEM–BTLA interaction by utilizing the same HVEM-binding site. Vaccines expressing antigens as fusion proteins within HSV gD induce markedly higher antigen-specific immune responses probably by disrupting the BTLA coinhibitory pathway and diminishing its inhibitory function on the immune response (35). LIGHT can effectively block gD binding to HVEM, even though LIGHT does not overlap with gD in the binding of HVEM (3). The reason behind this activity is not clear. It is possible that LIGHT induces allosteric structural changes when binding to HVEM, which prevents gD from binding to HVEM. Interestingly, LIGHT/HVEM/BTLA can form a complex in vitro (11, 18), but the biological significance of this complex awaits further investigation.

The function of LIGHT

The role of LIGHT on T cells

Previous studies from many laboratories have shown that LIGHT is a costimulatory molecule for T-cell activation, especially for CD8+ T cells. Studies from Pfeffer and colleagues (36) revealed that T-cell receptor (TCR)-stimulated LIGHT−/− CD8+ T cells had an impaired proliferative response, and LIGHT−/− CD4+ T cells had defective interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion. However, two other groups found that LIGHT−/− CD4+ T cells had no defects by using similar strategies (37, 38).

To more clearly address the pathological outcome of prolonged expression of LIGHT on T cells, a situation most likely found in chronic inflammation, we generated a transgenic (Tg) mouse line that constitutively expresses mouse LIGHT on T cells under the control of the proximal lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (lck) promoter and CD2 enhancer. These mice spontaneously develop severe chronic inflammatory diseases over a period of 5–6 months after birth (39, 40). Peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are greatly expanded and activated over time in these LIGHT-Tg mice, which supports the idea that T cells provide the LIGHT ligand to stimulate other T cells, probably through direct T–T-cell interaction. Constitutive expression of human LIGHT on mouse T cells by Shaikh et al. (41) also recapitulates these phenotypes. The binding affinity of human LIGHT to mouse HVEM and mouse LTβR is somewhat different from that of mouse LIGHT, in that human LIGHT-Tg mice seem to experience more severe disease (41).

LIGHT has also been implicated in CD4+ T-effector cell differentiation and/or expansion. In vitro, recombinant LIGHT in combination with anti-CD3 promotes CD4+ T-helper 1 cell (Th1) production. In vivo, overwhelming Th1 cells can be found in the gut when transferring LIGHT-Tg lymphocytes into RAG-1−/− mice (42). In a Leishmania major infection mouse model, LIGHT−/− → RAG1−/− bone marrow chimeric mice are more susceptible to L. major infection than WT → RAG1−/− bone marrow chimeric mice; this finding correlated with reduced Th1 cytokine [interferon-γ (IFN-γ)] production. Treatment of HVEM–Ig or LTβR–Ig on the usually resistant WT C57BL/6 strain of mice results in defective IL-12 and IFN-γ production and severe susceptibility to L. major infection (43). These data overall support an essential and sufficient role for LIGHT in the development of Th1 cells. Interestingly, LIGHT-Tg mice spontaneously develop intestinal inflammation, a pathological phenomena that is related to the IL-23/IL-17 axis (reviewed in 44). LIGHT may therefore play some role in Th17 cell production. Whether LIGHT plays any role in other Th cell type differentiation/expansion or function remains to be studied further.

The role of HVEM, one of the receptors for LIGHT, on T cells

The mechanisms behind the costimulatory role of LIGHT on T cells remain poorly understood. Among the possibilities is that LIGHT interacts with its receptor HVEM expressed on T cells leading to activation. The phenotypes that we found on HVEM−/− mice, however, may indicate otherwise. HVEM−/− T cells showed enhanced responses to ConA stimulation in vitro, and HVEM−/− mice exhibited increased morbidity and mortality in vivo in a ConA-mediated T-cell-dependent autoimmune hepatitis model (28). HVEM−/− mice produced higher levels of multiple cytokines that depend on the presence of CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, HVEM−/− mice were more susceptible to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide-induced experimental autoimmune encephalitis, and they showed increased T-cell proliferation and cytokine production in response to antigen-specific challenge. These phenotypes from HVEM−/− mice are more similar to those found in BTLA−/− mice and are consistent with the notion that HVEM acts through BTLA to inhibit T-cell responses instead of interacting with LIGHT under these acute stimulation conditions (10, 28). Whether the BTLA–HVEM interaction underlies this similarity, however, is still under investigation.

Both HVEM−/− and BTLA−/− mice have increased number of memory CD8+ T cells (45). These increased memory cells could account for the hyper-responsiveness of HVEM−/− and BTLA−/− T cells by anti-CD3 stimulation in vitro. HVEM–BTLA interaction on T cells might be able to control the CD8+ T-memory cell pool, as naive BTLA-deficient CD8+ T cells were more efficient than WT cells at generating memory in a competitive antigen-specific system. This effect was independent of the initial expansion of the responding antigen-specific T-cell population. In addition, BTLA negatively regulated antigen-independent homeostatic expansion of T cells. In striking contrast, the primary expansion and memory/recall of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to influenza A virus in LIGHT−/− mice were not affected (46). Whether LIGHT plays any roles in memory T-cell generation in other models remains to be studied.

HVEM expression on CD4+ CD25+ T-regulatory cells (Tregs) helps to mediate the suppressive functions of Tregs (47). HVEM−/− Tregs had decreased suppressive activity. Whether LIGHT plays a role in the regulation of Tregs by interaction with HVEM remains to be determined. Interestingly, although LIGHT-Tg mice develop inflammatory bowel-like disease (IBD), this process is quite slow and requires about 5–6 months to develop. During the initial 2–3 months after birth, over-activation of T cells in LIGHT-Tg mice is not readily apparent. The number of FoxP3+ Tregs in these animals, however, is increased in young LIGHT-Tg mice and continuously increases over time as the mice age. This observation suggests that Tregs in this environment may be trying to compensate for and help to counter the over-activation of conventional T cells during the early phase of inflammation development (Wang et al., unpublished data).

The downstream signaling events after LIGHT stimulation on T cells have not been extensively studied. LIGHT engagement on human T cells can induce nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation and can further boost NF-κB activation in cooperation with TCR signaling (48). Much more work is needed to have comprehensive pictures regarding LIGHT-induced signaling pathways in T cells.

The HVEM cytoplasmic portion is able to interact with TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) and TRAF5, and overexpression of HVEM with TRAF5 but not with TRAF2 leads to synergistic activation of NF-κB in human 293 cells (49). Overexpression of HVEM in 293 cells also activates Jun N-terminal kinase and the Jun-containing transcription factor activator protein-1 (AP-1), which can play various functions (50). How these findings correlate with the costimulatory role of HVEM interaction with LIGHT on T cells is not known, although the coinhibitory signaling produced by HVEM interaction with BTLA or CD160 on T cells should also be considered.

The role of LIGHT on DCs

DCs are an important cellular component for initiating and regulating various immune responses. Earlier studies indicated that human LIGHT can induce peripheral blood-derived DC maturation, especially when in cooperation with CD40L. LIGHT on these mature DCs promotes the production of cytokines such as IL-12, IL-6, and TNF-α as well as enhances DC-mediated allogeneic T-cell responses (51). Human LIGHT alone can induce partial DC maturation, as demonstrated by a modest increase of antigen presentation and upregulation of CD54 and CD86 on DCs (51). The function of LIGHT on mouse DCs is less well understood. Earlier studies did not find obvious defects in LIGHT-deficient DCs in an allogeneic mixed lysmphocyte reaction (MLR) (38). A recent report, however, indicated that mouse bone marrow-derived LIGHT-deficient DCs had a decreased ability to produce IL-12 when primed by IFN-γ and stimulated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (43). Thus, it seems that LIGHT might play important roles on DCs, at least under certain conditions.

The number of DCs in the periphery is a critical factor in controlling immune responses. DC numbers have been attributed mainly to the proliferation of precursors in the bone marrow by cytokines such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) (52). A recent study has indicated that local homeostatic expansion is also critical in regulating the size of the DC pool in the periphery (52). In terms of molecules regulating this expansion, LTβR signaling on DCs has been found to be important in controlling lymphoid tissue DC homeostasis (53, 54). Consistent with this finding, LIGHT Tg mice have a dramatic increase of DCs in secondary lymphoid tissues. The physiological ligands inducing LTβR signals on DCs remain to be determined. However, overexpression of LTα1β2 on B cells was found to be sufficient to promote splenic DC accumulation in vivo (53). It is very likely that LTβR signaling on DCs is activated by different ligands in a context-dependent manner. Interestingly, there may be a role for HVEM–BTLA in counterbalance regulation of the local homeostatic expansion of DCs in non-immunized mice (55). It appears that an integrated signaling circuit on DCs can impart the ability to control the homeostasis by themselves.

The role of LIGHT on NK cells

NK cells represent a distinct population of lymphocytes. They play an important role in preventing both viral infections and cancer development. Earlier studies indicated that LTβR signaling on bone marrow stromal cells is required for NK cell development (56). Mature NK cell function can be regulated by LIGHT (57), as plate-bound recombinant LIGHT can induce the proliferation of purified NK cells and secretion of GM-CSF and IFN-γ. Introducing LIGHT into fibrosarcoma tumor Ag104Ld dramatically increases NK cells inside the tumor, which can further trigger expansion and activation of CD8+ T cells to promote tumor regression (57). The role of LIGHT on NK cells is partially blocked in HVEM−/− NK cells, indicating that the LIGHT–HVEM interaction on NK cells is important for NK cell function.

The role of LIGHT in lymphoid organ development

Lymphoid organ development occurs throughout the lifetime of an organism and is a continuous process. Some lymphoid organs are genetically programmed during ontogeny, while others are induced during chronic inflammation in non-lymphoid tissues. The size, micro-architecture, and cellular components of the lymphoid organs are also constantly changing during different phases of an inflammatory response (58).

The role of LIGHT on mesenteric lymph node genesis has been revealed by LIGHT−/−LTβ−/− double knockout mice (36). In these mice, the mesenteric lymph nodes are present at a lower percentage as compared with LTβ−/− mice, suggesting that LIGHT and membrane lymphotoxin cooperate in controlling mesenteric lymph node development.

LIGHT can also promote tertiary lymphoid organ (TLO) formation. We observed that Tg mice expressing LIGHT in the β cells under the control of the rat insulin promoter (RIP) on the non-obese diabetic (NOD) background (RIP-LIGHT-NOD mice) developed diabetes with complete onset at a much earlier age compared with the NOD control animals (59). Histological analysis of pancreatic tissue from five-week-old RIP-LIGHT-NOD mice revealed organized T–B-cell zones that closely mimicked those found in secondary lymphoid follicles yet were conspicuously absent in five-week-old NOD control mice. In addition, four to five-week-old RIP-LIGHT-NOD mice had elevated pancreatic expression of Secondary Lymphoid Tissue Chemokine (SLC) mRNA than four to five-week-old NOD control mice, indicating an increased ability to attract T cells. These TLOs in RIP-LIGHT-NOD mice, associated with the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), were able to attract naive T cells into these structures and promote T-cell activation in situ, even after surgical removal of the pancreatic draining lymph node.

LTβR signaling in both non-immunized resting and immunized reactive states influenced the cellularity of lymph nodes in adult mice (60). The reduction in cellularity by LTβR–Ig treatment resulted mostly from impaired lymphocyte trafficking and entry into lymph nodes due to decreased levels of peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd) and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule (MAdCAM) on high endothelial venules (HEV). Although LIGHT−/− mice do not have reduced lymph node cellularity in resting conditions, LIGHT−/− mice do have smaller lymph nodes after immunization (Wang et al., unpublished data). Thus, it is likely that LIGHT may also actively participate in lymph node remodeling during inflammation.

LIGHT in disease

The role of LIGHT in cancer immunotherapy

The importance of T-cell costimulation and coinhibition in controlling immune responses is exploited by tumors for immune evasion, and the manipulation of these pathways is crucial for developing effective tumor immunotherapy (61). Indeed, DcR3, a potential LIGHT-blocking molecule, is highly expressed in human primary lung cancer and gastrointestinal tumors (30, 62), suggesting that it might be related to these tumors’ immunosuppressive functions.

Earlier studies indicated that LIGHT can signal via LTβR and/or HVEM expressed on tumor cells to induce tumor cell apoptosis, especially in the presence of IFN-γ (4, 33, 63). This effect seems to be independent of T cells, as LIGHT can directly inhibit human breast cancer cell growth in athymic nude mice (64).

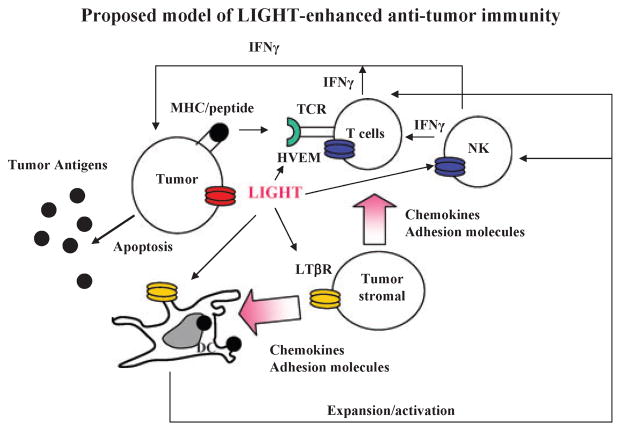

In terms of therapeutic use, LIGHT expression inside the tumors is effective in overcoming physiological and immunological barriers within the tumor. Intratumor LIGHT expression recruits immune cells for intratumor priming and activation of adaptive immunity to inhibit the growth of primary tumors as well as metastases (19, 20). We have shown the mechanism of recruitment to be LIGHT activation of LTβR on tumor stromal cells, leading to upregulation of both chemokine and adhesion molecules inside tumors that function to attract naive T cells into the tumor environment. Furthermore, LIGHT also acts as a strong costimulatory molecule for T-cell activation, most probably by binding to HVEM on T cells (Fig. 2). This ability of LIGHT to directly recruit and prime naive T cells within the tumor environment has several advantages. First, the higher tumor antigen load in situ would improve the efficiency and specificity of priming. Second, recruitment of a broader repertoire of tumor-specific naive T cells to the site of tumor antigens would lead to a broader and more comprehensive response especially for those antigens that cannot be cross-presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Third, no additional priming step in the draining lymph node would be required for naive T cells to reach the target sites, potentially bypassing barriers created within the tumor environment to resist infiltration. Finally, T cells may have a lower threshold of activation and react more readily and robustly to the tumor antigen loss variants in situ due to increased costimulation and activation by LIGHT. In order to deliver LIGHT intratumorly, our group has engineered an adenovirus that expresses LIGHT (Ad-LIGHT) (20). By intratumoral injection of Ad-LIGHT, we can achieve expression of LIGHT inside the tumor. The current understanding of the cellular and molecular interactions created between the immune system and the tumor has led to optimistically foresee immunotherapy as a potential tool for cancer treatment (65), and it would be beneficial to pursue LIGHT treatment in combination with other existing treatment to effectively eradicate human tumors.

Fig. 2. Proposed model of LIGHT-enhanced anti-tumor immunity.

Membrane-bound LIGHT [homologous to lymphotoxins, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes] stimulates stromal cells via lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) to upregulate chemokines, such as SLC, and adhesion molecules to recruit naive T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) into the tumor tissue. LIGHT promotes the survival, expansion, and maturation of DCs, which possibly prime the T cells in situ. LIGHT also costimulates recruited naive T cells, possibly through HVEM, in the presence of tumor antigen for their activation and expansion. Natural killer (NK) cells, which express HVEM, can be activated by LIGHT to produce interferon-γ (IFN-γ) to facilitate the expansion and differentiation of T cells and production of abundance of IFN-γ. Tumor cells signaled by LIGHT via LTβR and/or HVEM may become apoptotic in the presence of IFN-γ leading to antigen release and better priming of anti-tumor immunity.

The role of LIGHT in graft-versus-host disease and allograft transplantation

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major complication associated with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. It occurs when donor immunocompetent T cells react to and attack the genetically disparate recipient. Blockade of T-cell costimulatory signals has been among the most sought after alternatives to immunosuppressants for this condition (66, 67). LIGHT, as a costimulator for T-cell function, has been found to play a critical role in GVHD and is a viable target for therapy to reduce GVHD in transplant patients. Blockade of LIGHT by LTβR–Ig can inhibit alloreactive cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) generation and prolongs the survival of non-irradiated parental-to-F1 GVHD mice independent of LT, another ligand of LTβR (5). This was further confirmed recently by the same group in a more rigorous way using LIGHT−/− donor cells (68).

LIGHT signaling during GVHD appears to exert its influence on T cells through HVEM, as HVEM−/− donor cells fail to induce GVHD (68). Interestingly, LIGHT or HVEM deficiency on donor T cells almost completely ablates the allo-CTL response irrespective of the genotype of the co-transferred non-T cells, suggesting that the LIGHT–HVEM interaction is dependent on T cell–T cell interaction (68). The role of LIGHT–HVEM interaction on donor T cells during GVHD seems to promote T-cell survival instead of proliferation.

It is of note that the LIGHT–HVEM interaction could also potentially interfere with the HVEM–BTLA interaction. Alternatively, loss of LIGHT–HVEM interaction might hinder expression of BTLA, which is normally upregulated upon T-cell activation (69). A recent study found that BTLA-deficient splenocytes transferred into F1 recipients fail to survive in the periphery of recipients. This unexpected observation suggests that HVEM–BTLA interaction is indispensable for the maintenance of GVHD response (70). Thus, the individual roles of LIGHT–HVEM and HVEM–BTLA in GVHD remains to be further determined. Making this scenario even more complicated, the recently identified CD160 receptor also delivers inhibitory signals through HVEM engagement (12). Its role in GVHD awaits future studies.

The costimulatory activity of LIGHT has also been documented in solid organ transplantation. A modest role for LIGHT was shown in a cardiac allograft transplant model, in which LIGHT−/− hosts maintained the cardiac allografts 3–4 days longer than the 1 week allograft survival normally seen in WT hosts (71). A dramatic synergistic effect, however, was shown when cyclosporine A (CsA), a common immunosuppressive drug in transplantation, was used in LIGHT−/− mice. The synergistic effect was associated with markedly reduced cytokines and chemokines and infiltration of host leukocytes when compared with WT mice treated with CsA. The synergistic effect of LIGHT deficiency coupled with CsA treatment was also shown when HVEM–Ig treatment, which acts to block LIGHT responses, was applied, although HVEM–Ig alone does not seem to prolong allograft survival (71). This outcome could be due to the complex involvement of BTLA and CD160. A role for LIGHT in rejecting allografts was also uncovered in a pancreatic islet cell transplantation model, where LTβR–Ig significantly increased allograft survival (72). However, considering the complex function of LTβR–Ig, the precise role of LIGHT in allograft survival needs to be further investigated.

The role of LIGHT in IBD

IBD is a chronic relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract associated with local intestinal and systemic immune responses and is caused by the loss of tolerance against intestinal antigens. The human LIGHT gene is mapped to a region overlapping with an IBD susceptibility locus on human chromosome 19p13.3 (15), suggesting that LIGHT might play an important role in IBD. Indeed, constitutive expression of LIGHT in vivo results in IBD-like diseases in mice caused by aberrant T-cell activation (39, 41). Adoptive transfer of LIGHT-Tg lymphocytes into RAG-1−/− mice can lead to severe intestinal inflammation in the hosts (42), with strikingly similar pathological characteristics observed in human IBD.

The mechanisms regarding how LIGHT promotes IBD development are still incompletely understood. The factors influencing the development of IBD are varied and many and include at least the microbial flora in the gut, the integrity of mucosa homeostasis and barrier functions, as well as the innate and adaptive immune systems of the mucosa (73). The barrier function of the intestine provided by anatomical features, including the pre-epithelial barrier and epithelial tight junctions, physically prevent the penetration of macromolecules and intact bacteria. LIGHT, in cooperation with IFN-γ, can activate intestinal epithelial LTβR signal to induce gut barrier dysfunction via cytoskeletal and endocytic mechanisms (74). Furthermore, LIGHT may be able to coordinate innate and adaptive immunity through LTβR and HVEM in the gut to promote gut inflammation, the details of which are unclear. Interestingly, HVEM expression by radioresistant non-lymphoid cells plays a critical role in preventing intestinal inflammation (75). The role of LIGHT in promoting tertiary lymphoid structure formation to support inflammation has been suggested in our studies (59). In general, tertiary lymphoid structures are prevalent in IBD, which might play an important role in maintaining chronic intestinal inflammation. How LIGHT breaks the tolerance created by the multiple checkpoints for the control of a normally immunotolerant gut environment is an interesting and important issue to pursue. Additionally, the efficacy of blocking LIGHT pathways in the treatment of human IBD remains to be tested in clinical trials.

The role of LIGHT in atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis has been recognized as a chronic inflammatory response, where lipid accumulates within the blood vessels and in which both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system play a critical role (76). Although a complete understanding of atherogenesis remains unclear, it is thought that the increase of cholesterol in the blood is probably the major factor for initiation of the atherosclerotic response. Atherosclerosis begins from a buildup of foam cells formed when cholesterol carrier-lipoproteins are retained in the vessel wall and are then modified and internalized by macrophages to form foam cells. Foam cells then accumulate and become fatty xanthoma, which attracts monocytes, lymphocytes, and smooth muscle cells to become a complex lesion. The foam cells may ultimately die either by necrosis or apoptosis, liberating the lipid contained within and producing a necrotic core with extracellular lipid. Late atherosclerotic plaques may also undergo cartilaginous dysplasia with calcium deposition. The increase in the size of the evolving atherosclerotic plaque arises from the continued recruitment of monocytes and lymphocytes, the continued migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells, the evolution of a necrotic core, and the synthesis of matrix protein. Activation of the macrophages in the lesions, particularly on the lesion shoulders, may lead to the release of proteases that disrupt the plaque surface, giving rise to an unstable plaque lesion. This lesion then becomes the nidus for thrombosis and consequent clinical complications.

LIGHT is detected in the macrophage foam cell region of the atherosclerotic plaque (77). HVEM-expressing THP-1 cells, a human monocytic leukemia cell line often used to study foam cell formation in vitro, incubated with recombinant soluble LIGHT produce IL-8, a powerful leukocyte chemokine, and express matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), MMP-9, and MMP-13 as well as inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1 and -2 (77). LIGHT also induces macrophage migration and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and both effects appear to be dependent upon signaling via HVEM (78). LIGHT expression can also be induced in THP-1 cells by oxidized-low-density lipoprotein (oxidized-LDL), where LIGHT then induces the expression of scavenger receptor A (SRA) and promotes lipid uptake in macrophages (79). These in vitro studies suggest that manipulation of LIGHT expression in atherosclerotic lesions has the potential to modulate atherosclerosis lesion development and plaque stability.

Young (one to two-month-old) lck-LIGHT Tg mice exhibit elevated plasma lipid levels when fed either normal chow diet or western-type diet (high fat or high cholesterol). The LIGHT-induced increase of plasma lipid levels is abrogated in the absence of the LTβR. In contrast, it is further aggravated in the absence of HVEM. Thus, LTβR signaling and HVEM signaling seem to play opposite roles in the regulation of these lipid changes. Further studies indicate that the interaction of LIGHT on T cells with LTβR on the liver cells can regulate key enzymes [such as hepatic lipase (HL)] that are involved in lipid metabolism to control lipid levels in the blood (80). LIGHT-induced uncontrolled lipid metabolism might play an important role in initiating and promoting atherosclerotic lesion genesis. An alternative or concurrent mechanism may be that LIGHT expression in the local atherosclerotic lesion might promote inflammation while decreasing lesion size, as the LDL receptor deficient (LDLR−/−) mice transplanted with bone marrow from LIGHT Tg mice displayed a decreased atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic sinus, while the lesions in the left coronary sinus were significantly more necrotic and inflammatory than those in control mice (personal communication from Dr Getz). Thus, it seems that LIGHT may play dichotomous roles in regulating atherosclerotic lesions.

Although LDLR−/− mice have a genetic defect in lipid metabolism due to LDLR deficiency and usually have high lipid levels in the blood, LTβR–Ig fusion protein treatment can still potently decrease the serum lipid levels in those mice (80). This strongly suggests biological levels of LIGHT and/or lymphotoxin might be capable of promoting the increases of blood lipid levels. As LIGHT/lymphotoxin are mostly expressed by activated lymphocytes, a destructive positive loop might exist between the plasma lipid levels and the activation of lymphocytes, whose collaboration results in chronic inflammation much like that manifested in atherosclerosis patients. Further investigation is needed to resolve these issues.

Concluding remarks

The broad expression of two related receptors for LIGHT and their complicated molecular cross-talk are challenging to dissect and discern the precise role of LIGHT in various processes. The information yielded from past and future studies will provide not only knowledge about the unique features of LIGHT but also the possible ways hosts regulate immune responses for survival and well-being in general. LIGHT is an attractive candidate for therapeutic intervention, and a better understanding of the mechanism(s) behind its involvement in pathogenesis will allow us to develop more effective treatment in the future.

Acknowledgments

This research was in part supported by US National Institutes of Health grants AI062026, CA115540, and DK58891 to Y. X. F.

References

- 1.Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretscher PA. A two-step, two-signal model for the primary activation of precursor helper T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:185–190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mauri DN, et al. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrop JA, et al. Herpesvirus entry mediator ligand (HVEM-L), a novel ligand for HVEM/TR2, stimulates proliferation of T cells and inhibits HT29 cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27548–27556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamada K, et al. Modulation of T-cell-mediated immunity in tumor and graft-versus-host disease models through the LIGHT co-stimulatory pathway. Nat Med. 2000;6:283–289. doi: 10.1038/73136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohmann HP, Remy R, Poschl B, van Loon AP. Tumor necrosis factors-alpha and -beta bind to the same two types of tumor necrosis factor receptors and maximally activate the transcription factor NF-kappa B at low receptor occupancy and within minutes after receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15183–15188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu KY, Kwon B, Ni J, Zhai Y, Ebner R, Kwon BS. A newly identified member of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TR6) suppresses LIGHT-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13733–13736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Migone TS, et al. TL1A is a TNF-like ligand for DR3 and TR6/DcR3 and functions as a T cell costimulator. Immunity. 2002;16:479–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang YC, Chan YH, Jackson DG, Hsieh SL. The glycosaminoglycan-binding domain of decoy receptor 3 is essential for induction of monocyte adhesion. J Immunol. 2006;176:173–180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sedy JR, et al. B and T lymphocyte attenuator regulates T cell activation through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:90–98. doi: 10.1038/ni1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez LC, et al. A coreceptor interaction between the CD28 and TNF receptor family members B and T lymphocyte attenuator and herpesvirus entry mediator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1116–1121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai G, Anumanthan A, Brown JA, Greenfield EA, Zhu B, Freeman GJ. CD160 inhibits activation of human CD4+ T cells through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:176–185. doi: 10.1038/ni1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan X, et al. A TNF family member LIGHT transduces costimulatory signals into human T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6813–6821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi G, Luo H, Wan X, Salcedo TW, Zhang J, Wu J. Mouse T cells receive costimulatory signals from LIGHT, a TNF family member. Blood. 2002;100:3279–3286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granger SW, Butrovich KD, Houshmand P, Edwards WR, Ware CF. Genomic characterization of LIGHT reveals linkage to an immune response locus on chromosome 19p13. 3 and distinct isoforms generated by alternate splicing or proteolysis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5122–5128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morel Y, et al. Reciprocal expression of the TNF family receptor herpes virus entry mediator and its ligand LIGHT on activated T cells: LIGHT down-regulates its own receptor. J Immunol. 2000;165:4397–4404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand S, et al. Essential role of TNF family molecule LIGHT as a cytokine in the pathogenesis of hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1045–1051. doi: 10.1172/JCI27083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung TC, et al. Evolutionarily divergent herpesviruses modulate T cell activation by targeting the herpesvirus entry mediator cosignaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13218–13223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506172102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu P, et al. Priming of naive T cells inside tumors leads to eradication of established tumors. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:141–149. doi: 10.1038/ni1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu P, et al. Targeting the primary tumor to generate CTL for the effective eradication of spontaneous metastases. J Immunol. 2007;179:1960–1968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohavy O, Zhou J, Ware CF, Targan SR. LIGHT is constitutively expressed on T and NK cells in the human gut and can be induced by CD2-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 2005;174:646–653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otterdal K, et al. Platelet-derived LIGHT induces inflammatory responses in endothelial cells and monocytes. Blood. 2006;108:928–935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-010629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang YM, et al. LIGHT up-regulated on B lymphocytes and monocytes in rheumatoid arthritis mediates cellular adhesion and metalloproteinase production by synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1106–1117. doi: 10.1002/art.22493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy M, et al. Expression of the lymphotoxin beta receptor on follicular stromal cells in human lymphoid tissues. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:497–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Browning JL, French LE. Visualization of lymphotoxin-beta and lymphotoxin-beta receptor expression in mouse embryos. J Immunol. 2002;168:5079–5087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy KM, Nelson CA, Sedy JR. Balancing co-stimulation and inhibition with BTLA and HVEM. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:671–681. doi: 10.1038/nri1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, et al. The role of herpesvirus entry mediator as a negative regulator of T cell-mediated responses. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:711–717. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, McAuliffe WJ, Zaritskaya LS, Moore PA, Zhang L, Nardelli B. Selective induction of tumor necrosis receptor factor 6/decoy receptor 3 release by bacterial antigens in human monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:89–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.89-93.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitti RM, et al. Genomic amplification of a decoy receptor for Fas ligand in lung and colon cancer. Nature. 1998;396:699–703. doi: 10.1038/25387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, et al. Modulation of T-cell responses to alloantigens by TR6/DcR3. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1459–1468. doi: 10.1172/JCI12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rooney IA, et al. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor is necessary and sufficient for LIGHT-mediated apoptosis of tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14307–14315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carfi A, et al. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bound to the human receptor HveA. Mol Cell. 2001;8:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lasaro MO, et al. Targeting of antigen to the herpesvirus entry mediator augments primary adaptive immune responses. Nat Med. 2008;14:205–212. doi: 10.1038/nm1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheu S, Alferink J, Potzel T, Barchet W, Kalinke U, Pfeffer K. Targeted disruption of LIGHT causes defects in costimulatory T cell activation and reveals cooperation with lymphotoxin beta in mesenteric lymph node genesis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1613–1624. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. LIGHT-deficiency impairs CD8+ T cell expansion, but not effector function. Int Immunol. 2003;15:861–870. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamada K, et al. Cutting edge: selective impairment of CD8+ T cell function in mice lacking the TNF superfamily member LIGHT. J Immunol. 2002;168:4832–4835. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, et al. The regulation of T cell homeostasis and autoimmunity by T cell-derived LIGHT. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1771–1780. doi: 10.1172/JCI13827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, et al. Dysregulated LIGHT expression on T cells mediates intestinal inflammation and contributes to IgA nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:826–835. doi: 10.1172/JCI20096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaikh RB, et al. Constitutive expression of LIGHT on T cells leads to lymphocyte activation, inflammation, and tissue destruction. J Immunol. 2001;167:6330–6337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, et al. The critical role of LIGHT in promoting intestinal inflammation and Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:8173–8182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu G, et al. LIGHT Is critical for IL-12 production by dendritic cells, optimal CD4+ Th1 cell response, and resistance to Leishmania major. J Immunol. 2007;179:6901–6909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maloy KJ. The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis in intestinal inflammation. J Intern Med. 2008;263:584–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krieg C, Boyman O, Fu YX, Kaye J. B and T lymphocyte attenuator regulates CD8+ T cell-intrinsic homeostasis and memory cell generation. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:162–171. doi: 10.1038/ni1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sedgmen BJ, Dawicki W, Gommerman JL, Pfeffer K, Watts TH. LIGHT is dispensable for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell and antibody responses to influenza A virus in mice. Int Immunol. 2006;18:797–806. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tao R, Wang L, Murphy KM, Fraser CC, Hancock WW. Regulatory T cell expression of herpesvirus entry mediator suppresses the function of B and T lymphocyte attenuator-positive effector T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:6649–6655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamada K, et al. LIGHT, a TNF-like molecule, costimulates T cell proliferation and is required for dendritic cell-mediated allogeneic T cell response. J Immunol. 2000;164:4105–4110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu H, Solovyev I, Colombero A, Elliott R, Kelley M, Boyle WJ. ATAR, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor family member, signals through TRAF2 and TRAF5. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13471–13474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsters SA, Ayres TM, Skubatch M, Gray CL, Rothe M, Ashkenazi A. Herpesvirus entry mediator, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family, interacts with members of the TNFR-associated factor family and activates the transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14029–14032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morel Y, Truneh A, Sweet RW, Olive D, Costello RT. The TNF superfamily members LIGHT and CD154 (CD40 ligand) costimulate induction of dendritic cell maturation and elicit specific CTL activity. J Immunol. 2001;167:2479–2486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Auffray C, Emre Y, Geissmann F. Homeostasis of dendritic cell pool in lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:584–586. doi: 10.1038/ni0608-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kabashima K, Banks TA, Ansel KM, Lu TT, Ware CF, Cyster JG. Intrinsic lymphotoxin-beta receptor requirement for homeostasis of lymphoid tissue dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;22:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang YG, Kim KD, Wang J, Yu P, Fu YX. Stimulating lymphotoxin beta receptor on the dendritic cells is critical for their homeostasis and expansion. J Immunol. 2005;175:6997–7002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Trez C, et al. The inhibitory HVEM–BTLA pathway counter regulates lymphotoxin receptor signaling to achieve homeostasis of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:238–248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu Q, et al. Signal via lymphotoxin-beta R on bone marrow stromal cells is required for an early checkpoint of NK cell development. J Immunol. 2001;166:1684–1689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fan Z, et al. NK-cell activation by LIGHT triggers tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell immunity to reject established tumors. Blood. 2006;107:1342–1351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drayton DL, Liao S, Mounzer RH, Ruddle NH. Lymphoid organ development: from ontogeny to neogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:344–353. doi: 10.1038/ni1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee Y, et al. Recruitment and activation of naive T cells in the islets by lymphotoxin beta receptor-dependent tertiary lymphoid structure. Immunity. 2006;25:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Browning JL, et al. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor signaling is required for the homeostatic control of HEV differentiation and function. Immunity. 2005;23:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zang X, Allison JP. The B7 family and cancer therapy: costimulation and coinhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5271–5279. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bai C, et al. Overexpression of M68/DcR3 in human gastrointestinal tract tumors independent of gene amplification and its location in a four-gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1230–1235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Browning JL, et al. Signaling through the lymphotoxin beta receptor induces the death of some adenocarcinoma tumor lines. J Exp Med. 1996;183:867–878. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhai Y, et al. LIGHT, a novel ligand for lymphotoxin beta receptor and TR2/HVEM induces apoptosis and suppresses in vivo tumor formation via gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Finn OJ. Cancer immunology. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2704–2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murphy WJ, Blazar BR. New strategies for preventing graft-versus-host disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:509–515. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blazar BR, Murphy WJ. Bone marrow transplantation and approaches to avoid graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1747–1767. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu Y, et al. Selective targeting of the LIGHT-HVEM costimulatory system for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2007;109:4097–4104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hurchla MA, Sedy JR, Gavrieli M, Drake CG, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. B and T lymphocyte attenuator exhibits structural and expression polymorphisms and is highly induced in anergic CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:3377–3385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hurchla MA, Sedy JR, Murphy KM. Unexpected role of B and T lymphocyte attenuator in sustaining cell survival during chronic allostimulation. J Immunol. 2007;178:6073–6082. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye Q, et al. Modulation of LIGHT-HVEM costimulation prolongs cardiac allograft survival. J Exp Med. 2002;195:795–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fan K, et al. Blockade of LIGHT/HVEM and B7/CD28 signaling facilitates long-term islet graft survival with development of allospecific tolerance. Transplantation. 2007;84:746–754. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000280545.14489.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwarz BT, et al. LIGHT signals directly to intestinal epithelia to cause barrier dysfunction via cytoskeletal and endocytic mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2383–2394. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steinberg MW, et al. A crucial role for HVEM and BTLA in preventing intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1463–1476. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Getz GS. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis. Immune function in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1–10. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R400013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee WH, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 14 is involved in atherogenesis by inducing proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2004–2010. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.098945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wei CY, Chou YH, Ho FM, Hsieh SL, Lin WW. Signaling pathways of LIGHT induced macrophage migration and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:735–743. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scholz H, et al. Enhanced plasma levels of LIGHT in unstable angina: possible pathogenic role in foam cell formation and thrombosis. Circulation. 2005;112:2121–2129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.544676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lo JC, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor-dependent control of lipid homeostasis. Science. 2007;316:285–288. doi: 10.1126/science.1137221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]