1. Introduction

Microbes have a remarkable capacity to build amino acid frameworks that are not incorporated into proteins. It has been estimated that about 500 naturally occurring amino acids have been identified to date, leaving the 20 proteinogenic amino acids as the 4% minority. Many of these nonproteinogenic amino acids have been discovered and biological context established since the last time this subject was reviewed in this journal in 1983.[1] While some of the nonproteinogenic amino acids are utilized as intermediates in primary metabolic pathways (e.g. homoserine, ornithine), most of the unheralded 96% majority serve as building blocks for small bioactive peptide scaffolds. They may represent an underutilized inventory of building blocks for protein engineers, medicinal chemists, and materials scientists.

On the one hand the existence of many hundreds of natural peptides with one or more nonproteinogenic amino acid residues reflects the ability of side chains of these particular monomers to impart some useful functional property not available in the 20 proteinogenic building blocks. On the other hand these natural peptide frameworks highlight the existence of biologic machineries for selection, activation, and incorporation of nonproteinogenic amino acid monomers into nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) as well as chain elongation of the resulting intermediates.[2,3] Perhaps many of those machineries could be moved, evolved, and re-engineered to work as building blocks in ribosomal protein biosynthesis. The development of pairs of evolved tRNAs and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to recognize synthetic unnatural amino acids, their introduction into growing cells, and the ability of the resulting cells to efficiently synthesize proteins harboring the corresponding unnatural amino acids augur well for the utility of these endogenously generated nonproteinogenic amino acids to the protein engineer.[4,5] To do so requires knowledge of the metabolic pathways to these noncanonical building blocks and the kinds of enzymatic transformations involved.

This review summarizes the biosynthetic routes to and metabolic logic for the major classes of the noncanonical amino acid building blocks that end up in both nonribosomal peptide frameworks and in hybrid nonribosomal peptide-polyketide scaffolds noted below.

In addition to microbial peptides of 2–22 residues built nonribosomally and therefore independent of mRNA messages, there are hundreds of naturally occurring scaffolds that are hybrids of peptide and polyketide (PK) frameworks,[6] many containing nonproteinogenic amino acid monomers. The rapamycin and FK506 family members,[7,8] sanglifehrin,[9] and the epothilones are examples of therapeutically interesting categories of such NRP-PK hybrid molecular frameworks that harbor nonproteinogenic amino acid units.[10,11]

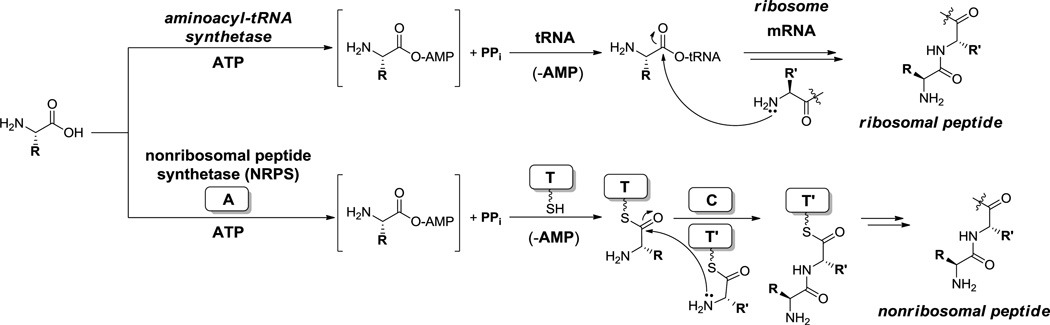

2. Amino Acid Selection, Activation, and Incorporation for Ribosomal versus Nonribosomal Peptide Biosynthesis

In both NRP and hybrid NRP-PK scaffolds, the amino acid monomers, proteinogenic and nonproteinogenic, are selected and activated by 50 kDa proteins, sometimes freestanding, but most often joined in multidomain proteins. These activation domains are termed adenylation (A) domains for the chemistry they perform on their amino acid substrates.[2] Each A domain selects an amino acid. Once bound to the active site, the enzyme utilizes the amino acid’s carboxylate group to attack the α-phosphate of a bound ATP cosubstrate, yielding a bound aminoacyl-adenylate (aminoacyl-AMP) (Scheme 1). This is exactly the mechanism for the first step of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases that activate amino acids used in protein biosynthesis: they are also amino acid adenylating enzymes.[12] However, structural analysis suggests, notwithstanding a few exceptions,[13] in most instances A domains and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases evolved independently. Therefore, they are not readily interchangeable, for example in protein biosynthesis replacement studies.

Scheme 1.

Biosynthesis of ribosomal versus nonribosomal peptides. ATP = adenosine triphosphate, AMP = adenosine monophosphate, PPi = pyrophosphate, A domain = adenylation domain, T domain = thiolation (peptidyl carrier protein) domain, C domain = condensation domain.

In the second step the two enzyme classes diverge with respect to the nature of the cosubstrate to which the activated aminoacyl group is now transferred (Scheme 1). For the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases the cosubstrate is a cognate tRNA and the attacking nucleophilic group is the 3’ or 2’-OH of the ribose ring of the terminal adenine in the CCA tail of each tRNA.[14] The resultant aminoacyl-tRNA is released and is subsequently chaperoned to the large subunit of the ribosome for mRNA-instructed protein biosynthesis.[14] In contrast, for the NRPS adenylation domains, the cosubstrate in the second step is the HS-pantetheinyl arm of the holo form of an 8–10 kDa thiolation (T) domain.[15] The T domains are often in cis with the A domains, as a contiguous downstream region of 80–100 residues following the ~500 residue A domains (A–T didomains by themselves or as parts of larger proteins). Transfer to the nucleophilic thiolate of the pantetheinyl arm yields T domain-tethered aminoacyl thioesters.[16]

Chain elongation on the ribosome and on NRPS assembly lines also has parallels and distinctions (Scheme 1). On the ribosome, an incoming aminoacyl-tRNA sits next to the growing peptidyl-tRNA, with occupancy of the incoming monomer determined by triplet coding between the mRNA codon and the tRNA anticodon. Once the proper aminoacyl-tRNA has been recognized and properly situated by action of conditional GTPases, peptide bond formation can occur in the peptidyl transferase center of the 50S ribosomal subunit, mediated by the 23S rRNA. The nucleophile is the N-terminal amino group of the peptidyl-tRNA. The electrophile is the activated carboxyl oxygen ester of the aminoacyl-tRNA. Peptide bond formation generates an elongated peptidyl-tRNA and the deacylated tRNA that had delivered the incoming aminoacyl group as coproduct. In contrast, in the mRNA-independent NRPS assembly lines, peptide bond formation is driven by a ~50 kDa condensation (C) domain. Again these domains are most often encoded in cis such that a typical NRPS elongation module has the composition C-A-T and would be about 110 kDa, consisting of three (semi-) autonomously folded domains.[2,17] Specificity of monomer incorporation into the growing peptide chain is not determined by mRNA triplet code but rather by which NRPS modules interact with each other sequentially.

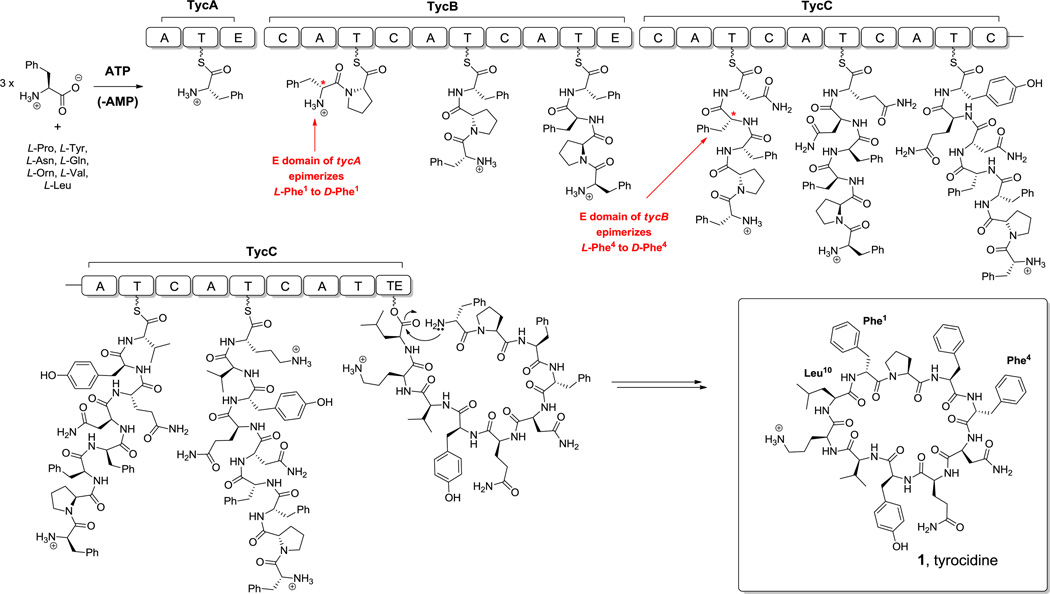

A prototypical NRPS responsible for tyrocidine (1) biosynthesis is shown in Scheme 2.[18] As is evident from this example, in many cases 3–5 modules are encoded in a single protein and chain elongation proceeds from N-C direction.

Scheme 2.

Tyrocidine and its NRPS. A = adenylation domain, T = thiolation (peptidyl carrier protein) domain, C = condensation domain, E = epimerase domain, TE = thioesterase domain.

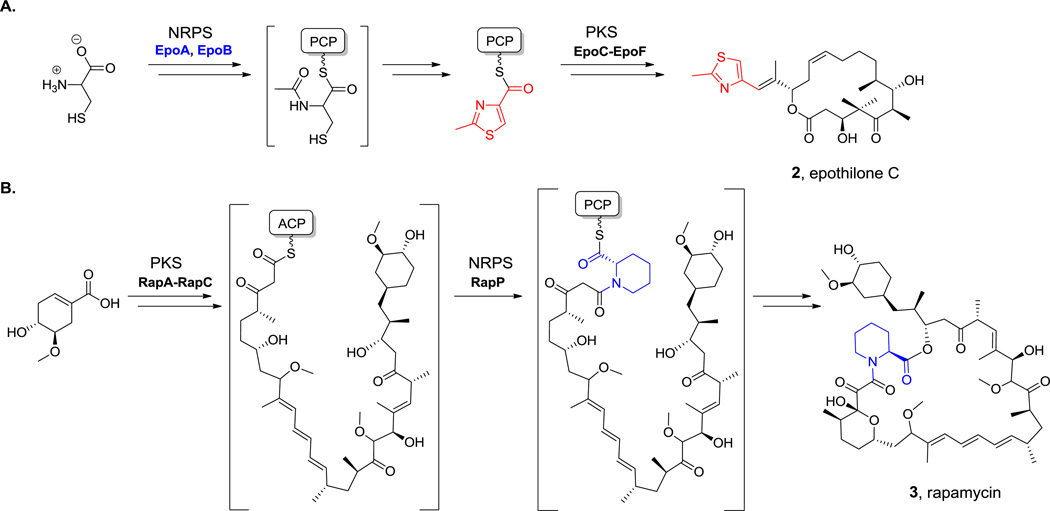

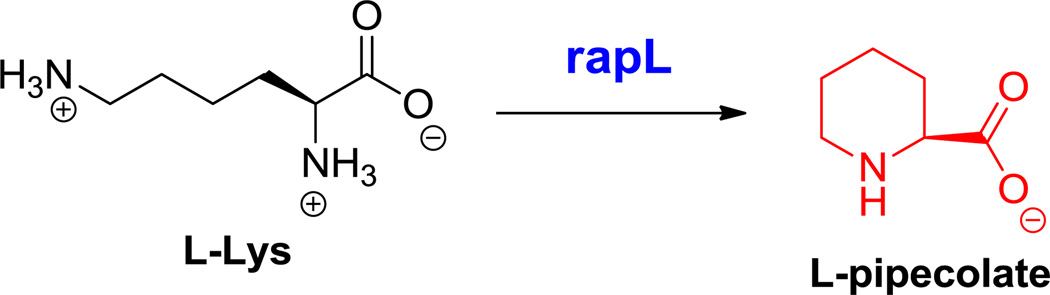

For hybrid NRP-PK natural products, particular NRPS modules have evolved to interface with polyketide synthase assembly lines.[17,19] One can find both possible orientations of NRPs and PKS modules in naturally occurring assembly lines. When an NRPS module is upstream of a PKS module, as is the case in epothilone C (2, Scheme 3A) biosynthesis, the aminoacyl-S-T domain must be recognized by and transferred to the first domain of the downstream PKS module.[20] Typically these are ketosynthase (KS) domains, which make C-C bonds by decarboxylative Claisen condensations. In the alternative configuration where an NRPS module is downstream of a PKS module, as in rapamycin (3, Scheme 3B) and FK506 assembly,[8] the C domain of that NRPS module must be able to recognize the immediately upstream polyketidyl-S-T domain.[21] Now the attacking nucleophile is the amino group of the aminoacyl-S-T domain in the NRPS module. Bond formation creates an amide linkage as the polyketidyl chain is transferred onto the NRPS module.[20,22]

Scheme 3.

Epothilone C and rapamycin biosynthesis. A. NRPS-PKS pathway. B. PKS-NRPS pathway. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = 2-methylthiazole-4-carboxylate, blue = L-pipecolate.

A. epoA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AAF62880.1

epoB: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AAF62881.1

B. Hyperlink 1: L-pipecolate formation in rapamycin biosynthesis.

There are examples of hybrid assembly lines where NRPS domains are flanked both upstream and downstream by PKS domains (e.g., epothilone)[20] and the reverse (e.g., bleomycin,[23] yersiniabactin).[24] One of the virtues of hybrid assembly lines is that they can build complex scaffold architectures and mix a variety of oxygen and nitrogen functionalities into the frameworks of the natural products. Advances in structural determination of domains and whole modules in PKS and NRPS assembly lines has begun to give insights into engineering new PKS-NRPS connectivities and altered specificities of building block utilization.[25,26]

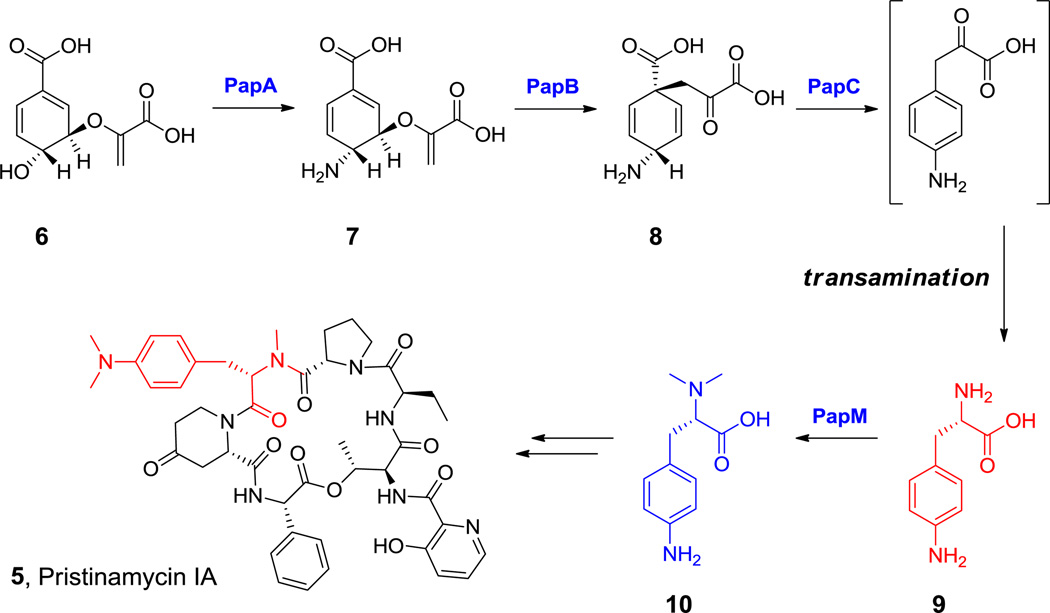

2.1 Para-Amino-Phe Biosynthesis in Streptomyces pristinaespiralis

The noncanonical para-dimethylamino-phenylalanine occurs in pristinamycin IA, an antibiotic produced by S. pristinaespiralis.[27] This building block arises from p-NH2-Phe (by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-mediated dimethylation), which is also a building block for chloramphenicol assembly in Streptomyces venezuelae.[28] Phe is not the direct precursor of p-NH2-Phe; instead it arises by diversion of metabolic flux from chorismate away from prephenate (Scheme 4). In keeping with NRPS assembly logic four pap genes are found in tandem next to the NRPS and PKS genes that build pristinamycin IA (5, Scheme 4) scaffolds in the S. pristinaespiralis genome.[29,30]

Scheme 4.

p-Aminophenylalanine biosynthesis in the pristinamycin IA pathway. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-(p-amino)-Phe (9) and L-((p-(N,N-dimethylamino))-Phe (10).

papA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AAC44866.1

papB: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AAC44868.1

PapA is a glutamine-dependent chorismate amidotransferase, converting chorismate (6, Scheme 4) into 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate (7, Scheme 4) that is the key intermediate formed in p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) biosynthesis.[31] However, in this case PapB intervenes and the enolpyruvyl side chain is not eliminated. Instead PapB is an aminodeoxychorismate mutase, generating 4-amino-4-deoxyprephenate (8, Scheme 4) presumably by a 3,3-electrocyclic rearrangement. This undergoes aromatizing decarboxylation/dehydrogenation by PapC to produce 4-aminophenylpyruvate, which in turn undergoes transamination to yield 4-amino-L-Phe (9). PapM can methylate the amino group once or twice to yield the mono- or dimethylamino-L-Phe (10) monomer, either of which can be incorporated into pristinamycins.

2.2 Incorporation of Nonproteinogenic Amino Acids into Proteins

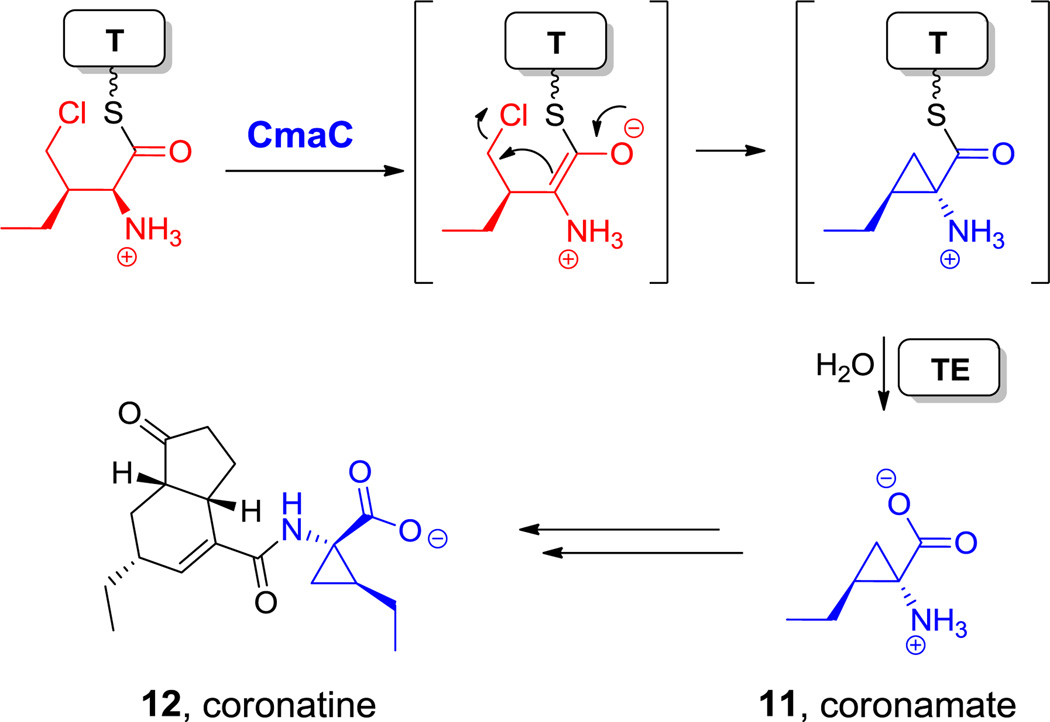

Schultz and colleagues moved the papABC gene cluster from S. venezuelae into an Escherichia coli strain into which they had inserted an evolved tRNA/tRNA synthetase pair that would recognize p-NH2-Phe and incorporate it via amber-suppressor codon technology site-specifically in myoglobin.[32] In principle, the strategy for p-NH2-Phe incorporation could be generalized to any of the other nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks described in this review, as long as the genes are known and the proteins are expressed in active form in a bacterial host (e.g. E. coli) harboring the engineered tRNA/tRNA synthetase pair to recognize the corresponding building block.[33] In practice, as discussed in the following sections, many nonproteinogenic amino acids required for NRP or mixed PK/NRP biosynthesis are generated as aminoacyl thioesters tethered to a protein-bound pantetheine arm. Once synthesized, these building blocks are directly utilized by the NRPS. Hijacking these unnatural amino acids for ribosomal protein synthesis will therefore require an engineered thioesterase. Fortunately, nature harbors a number of these aminoacyl thioesterases: for example, the nonproteinogenic amino acid coronamate is produced as a protein-bound thioester, which is hydrolyzed prior to incorporation into the natural product coronatine (Scheme 5).[34]

Scheme 5.

Coronamate biosynthesis and incorporation in the coronatine pathway. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2R)-2-amino-3-(chloromethyl)pentanoic acid, blue = coronamate (11).

3. Biosynthesis of Nonproteinogenic Amino Acids

3.1 ORFs within NRPS Clusters

In this review we focus on the unusual amino acid building blocks, the nonproteinogenic ones, that are fashioned by producer microbes for specific incorporation into the above classes of molecular scaffolds. Some of these nonproteinogenic amino acids are fashioned from the canonical 20 proteinogenic amino acids while others are biosynthesized de novo. For any nonproteinogenic amino acid with a known biosynthetic pathway, a hyperlink is provided within each scheme that shows the biosynthetic pathway with links to the relevant GenBank entry. In cases where the biosynthetic pathway is unknown, a hyperlink is included that shows a hypothetical biosynthetic pathway for pedagogical purposes.

In most cases the genes encoding these dedicated amino acid building blocks are adjacent to genes for the NRPS assembly line modules, enabling coordinate regulation to make the building blocks as they are needed. This feature greatly simplifies the task of finding open reading frames (ORFs) that encode enzymes dedicated to nonproteinogenic amino acids and then moving them to production organisms. For example, as discussed above, the genes encoding p-dimethylamino-phenylalanine are clustered in the pristinamycin IA producer (Scheme 4).[29]

3.2 Major Classes of Reactions that Build Nonproteinogenic Amino Acids

Most of the almost 500 of the nonproteinogenic amino acids are produced by a small number of enzymatic reactions, either from preexisting proteinogenic amino acids or by de novo construction. Examples discussed below include: 1) racemases that make D-amino acids from L-enantiomers;[35,36] 2) mutases that convert α-amino acids into β-amino acids;[37,38] 3) reactions that produce β-methyl substituted amino acids and hydroxylases that install -OH groups, often as β-OH substituents;[39,40] 4) oxygen-dependent halogenases that install chlorines on both activated and unactivated carbon centers;[41] 5) de novo construction of phenylglycines with both 4-OH- and 3,5-(OH)2 substitution patterns are shown to arise by entirely different molecular logic;[42,43] 6) biosynthesis of α,ω-diamino acids, such as 2,3-diaminopropionate (DAP) and 2,4-diaminobutyrate (DAB);[44,45,46] 7) several distinct types of cyclic nonproteinogenic amino acids are discussed, from three membered cyclopropanes (e.g. coronomate, Scheme 5), four membered tabtoxin β-lactam,[47] to five membered enduracididine,[48] to six membered capreomycidine,[49] pipecolate, and piperazate rings; and 8) the transformation of tryptophan to kynurenine,[50] and of tyrosine to propyl- and propenyl prolines is analyzed.[51]

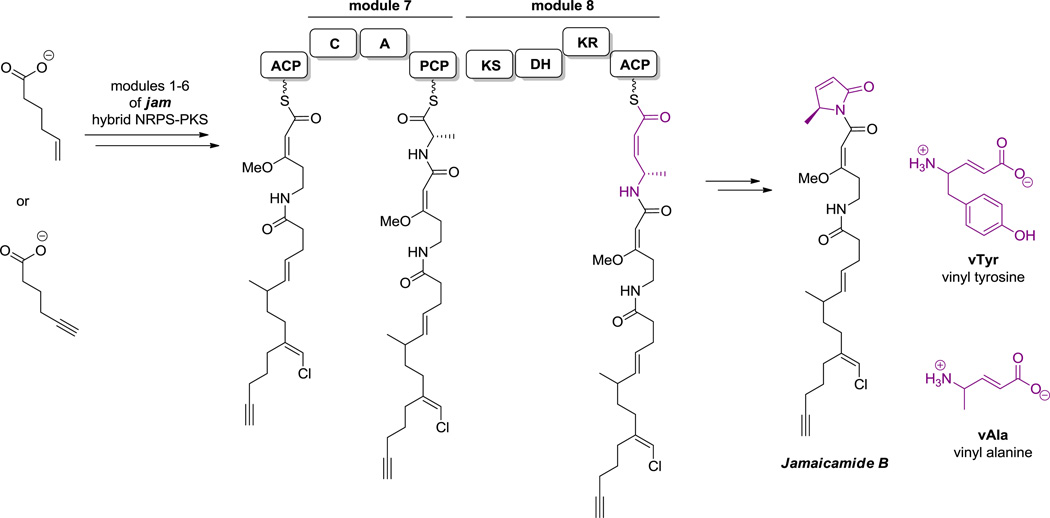

Some of the carbon skeletons of noncanonical amino acids, such as 2-amino-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-6-octenoate, 2-amino-8-oxo-9,10-decanoate and 3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl-4,6-decadienoate, are fashioned by PKSs as free monomers, which undergo late stage enzymatic reductive amination.[52] Other amino acids, such as statine and isostatine, are synthesized on hybrid NRPS-PKS assembly lines and directly incorporated into the growing chains.[53] Comparable hybrid logic and enzymatic machinery pertains for building vinyl-Arg and vinyl-Tyr units.[54]

To illustrate particular molecular contexts for major nonproteinogenic amino acid classes, in the next section we introduce 15 NRP scaffolds and an additional 4 hybrid NRP-PK scaffolds. Together these 19 frameworks contain about 50 of the most common nonproteinogenic building blocks, representative of almost all the major classes of amino acid scaffolds. We then review the details of how those and related nonproteinogenic building blocks are generated within the producer microbes.

4. Nonproteinogenic Amino Acid Residues in NRP frameworks

4.1 Linear Peptide Frameworks

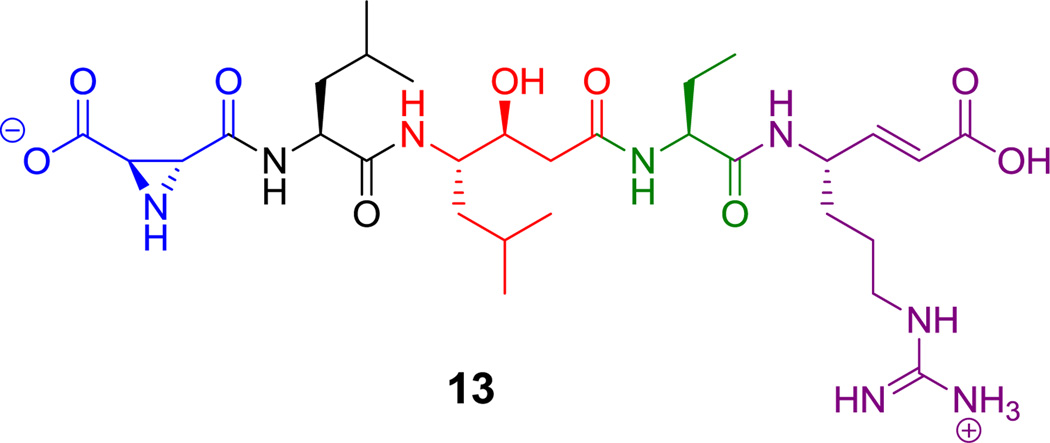

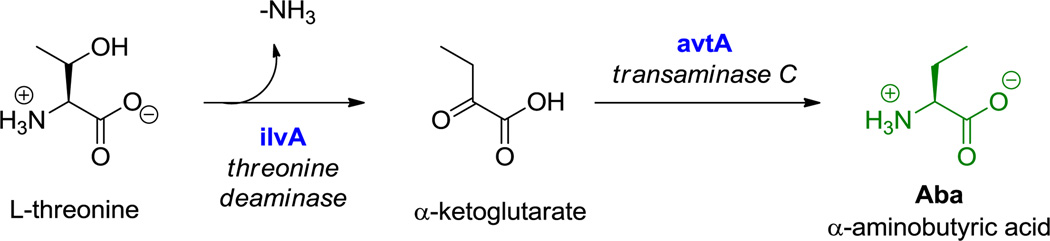

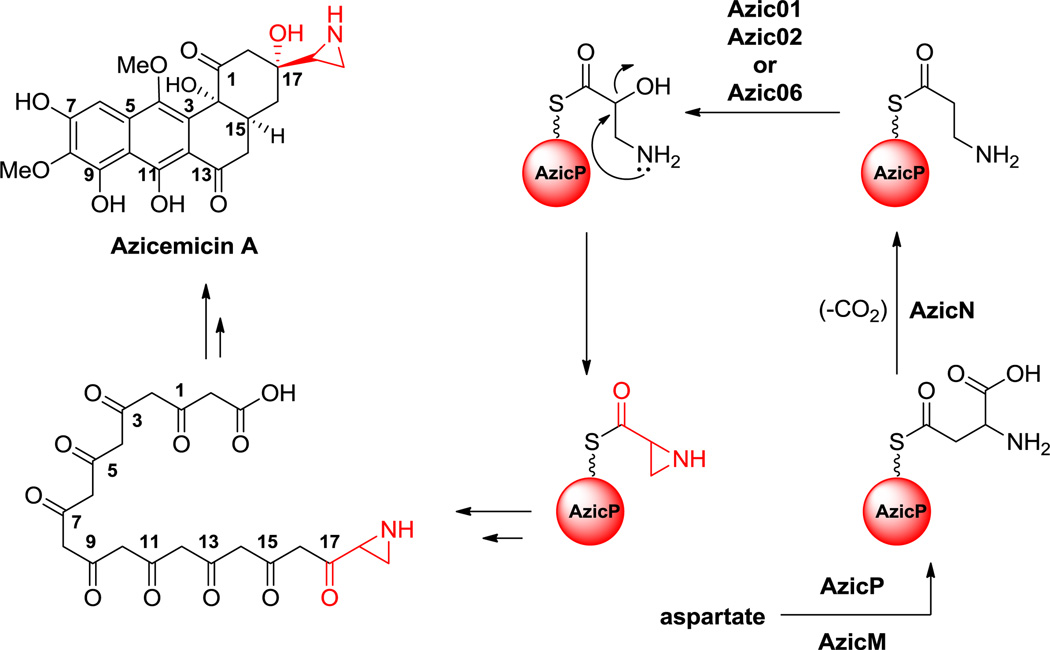

Nonproteinogenic building blocks are found in linear NRP scaffolds, such as in the sponge-associated miraziridine A (13, Figure 1), probably produced by bacteria in the consortium.[55] This linear pentapeptide has four nonproteinogenic residues out of five total. In addition to aminobutyrate (Aba),[56] the next longer homolog of Ala, there are three remarkable building blocks: an aziridine dicarboxylate (Azd),[57] statine,[53] and vinyl-Arg.[54] The three-membered aziridine ring is unusual in biology and likely a reactive chemical functionality.[58,59] Statine and vinyl-Arg are synthesized by hybrid NRPS-PKS assembly lines, as explained in section 6.1.

Figure 1.

Miraziridine A. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (3S, 4S)-statine, blue = (2R, 3R)-aziridine-2,3-dicarboxylate, green = L-α-aminobutyrate, purple = (S)-vinyl-Arg.

Hyperlink 2: Hypothetical biosynthesis of miraziridine A.

Hyperlink 3: Biosynthesis of α-aminobutyric acid (Aba) in E. coli K-12.

avtA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/YP_491862.1

ilvA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/CAA28577.1

Hyperlink 4: Biosynthesis of statine moiety of Thailandepsin E.

Hyperlink 5: Biosynthesis of vinylogous alanine moiety of Jamaicamide B

4.2 Cyclic Peptide Frameworks

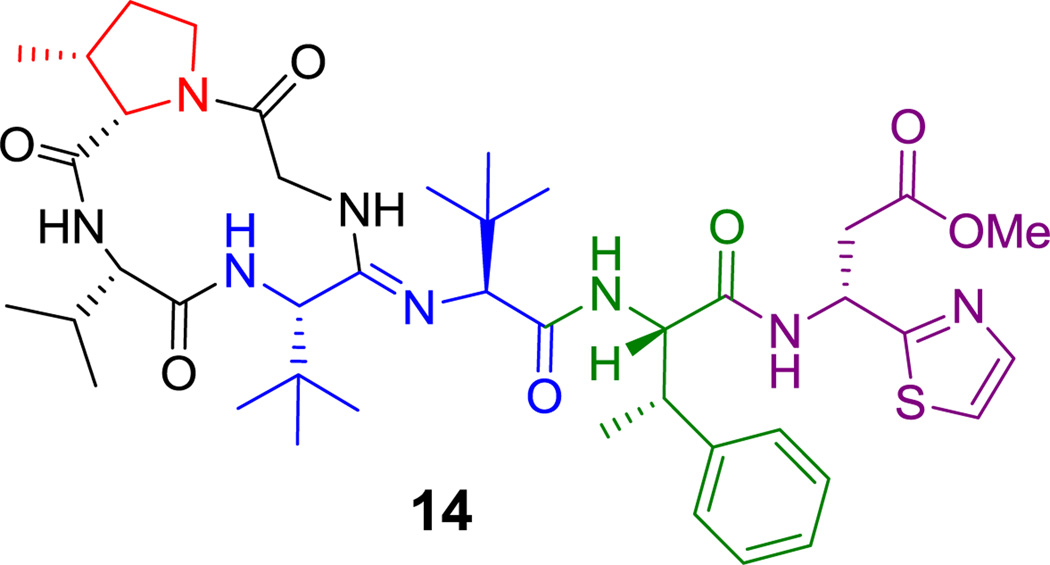

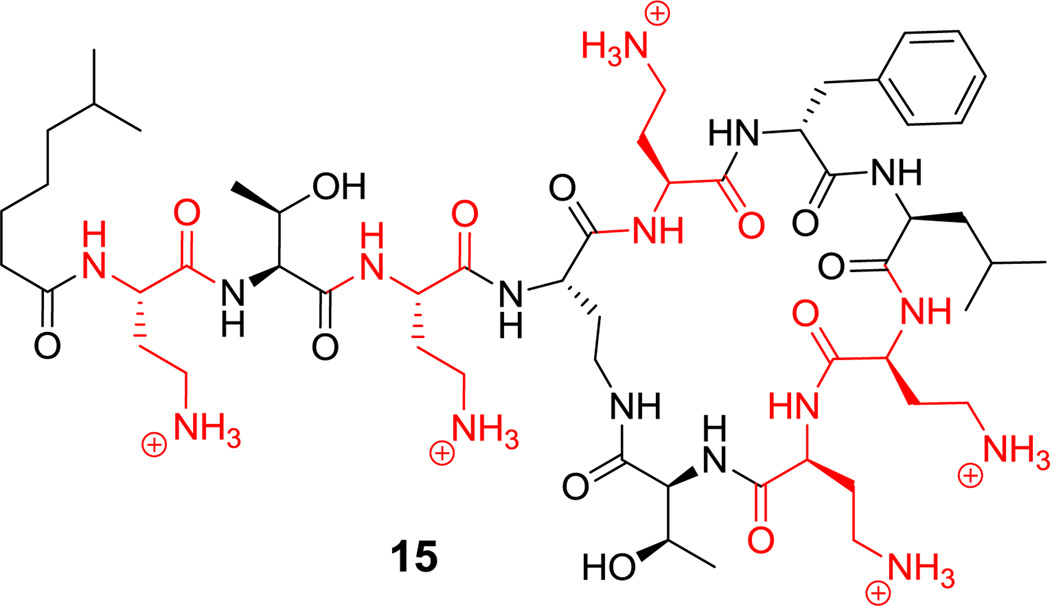

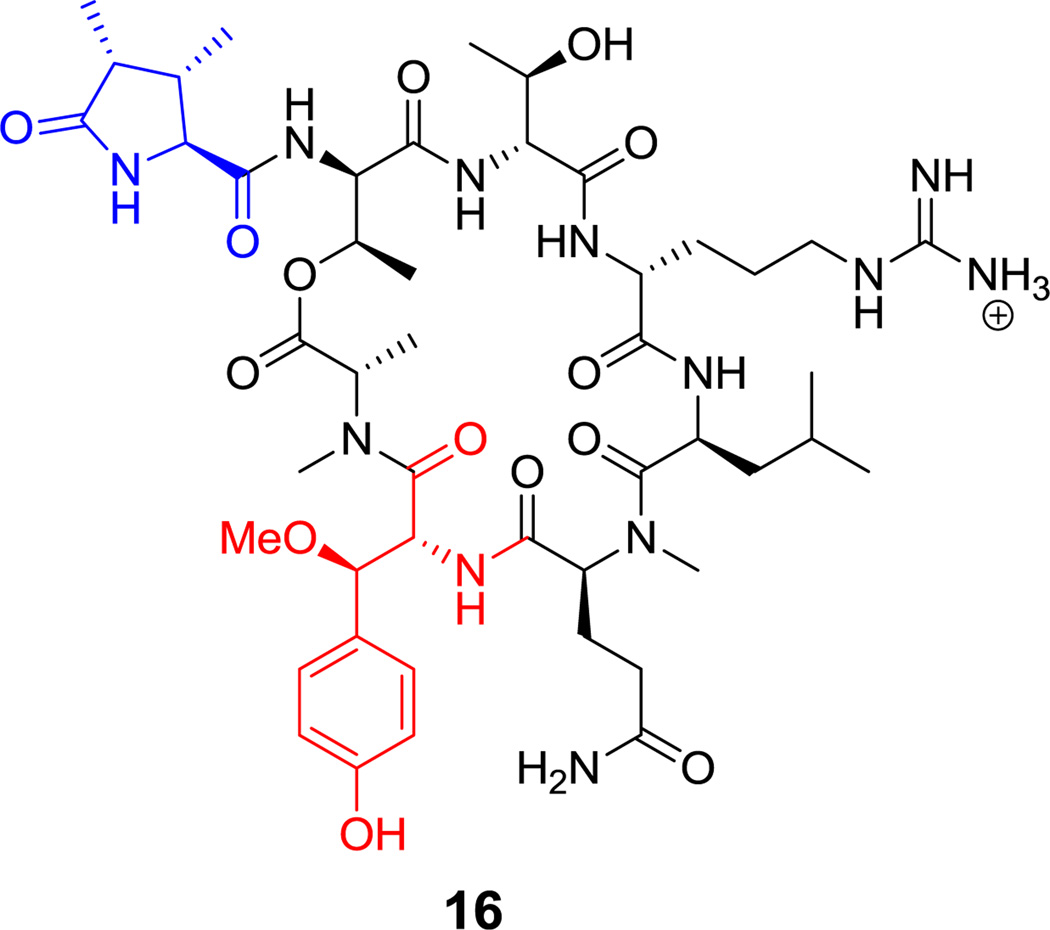

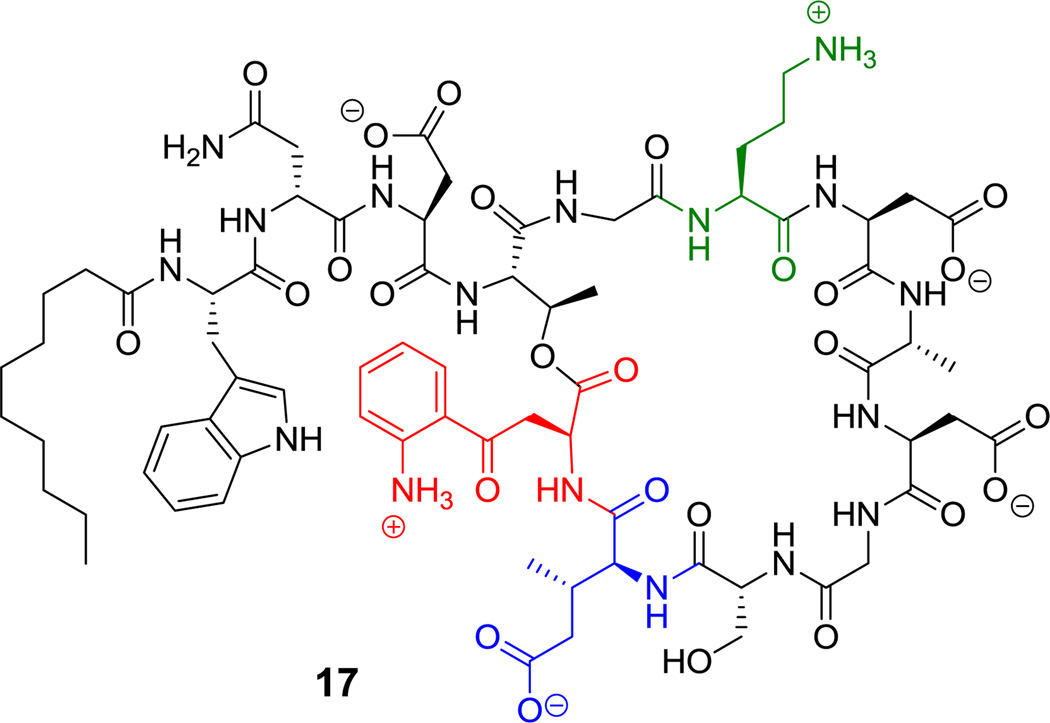

There is sustained interest in cyclic frameworks whose conformational constraints generate fixed three dimensional molecular architectures that can produce high affinity ligands for biological targets.[60] Here we discuss fifteen cyclic peptide frameworks with 3–15 residues in their macrocyclic frameworks. Ring closing of such cyclic peptides can be achieved by macrolactam (cyclic amides), macrolactone (cyclic esters), cyclic amidine (as in the case of bottromycin A2 (14), Figure 2),[61] or aryl ether bridge formation. As seen in Scheme 2, the decapeptidic macrolactam of tyrocidine (1) is formed by head-to-tail condensation of Phe1 and Leu10,[62] whereas the polymyxin nonapeptides (such as polymyxin B2 (15), Figure 3) form stem-loop macrolactam structures in which a side chain amine from 2,4-DAB is the nucleophile.[46,63] Macrolactone linkages (also known as depsipeptides) can arise from the side chain hydroxyl of Thr, as in callipeltin B (16, Figure 4)[64,65] and daptomycin (17, Figure 5),[50,66] or Ser, as in enterobactin.[67]

Figure 2.

Bottromycin A2. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2S,3R)-3-methyl-Pro, blue = L-t-butyl-Gly, green = (2S,3S)-β-methyl-Phe, purple = (R)-methyl 3-amino-3-(thiazol-2-yl)propanoate.

Figure 3.

Polymyxin B2, a stem-loop macrolactam. Nonproteinogenic amino acid: red = L-2,4-diaminobutyrate (2,4-DAB).

Hyperlink 6: Biosynthesis of 2,4-diaminobutyrate (2,4-DAB) from aspartyl phosphate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1

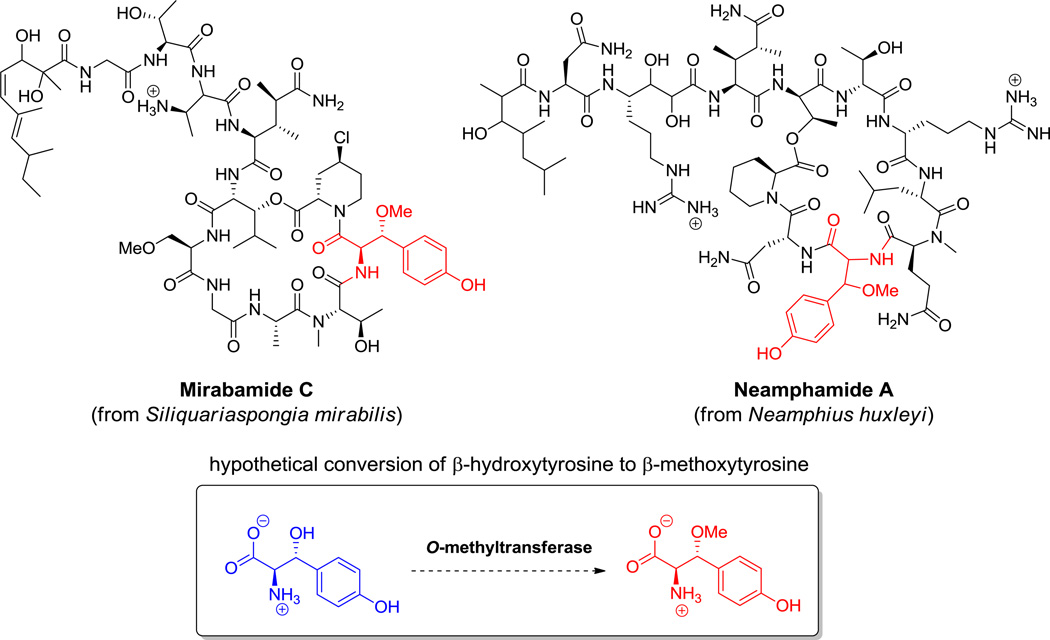

Figure 4.

Callipeltin B, a Thr linked depsipeptide. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2R,3R)-β-methoxy-Tyr, blue = (2S,3S,4R)-3,4-dimethyl-5-oxo-Pro.

Hyperlink 7: Anti-HIV marine cyclicdepsipeptides containing a β-methoxytyrosine moiety.

Figure 5.

Daptomycin. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-kynurenine, blue = (3S,4S)-b-methylglutamate, green = L-ornithine.

Hyperlink 8: Biosynthesis of kyneurinine.

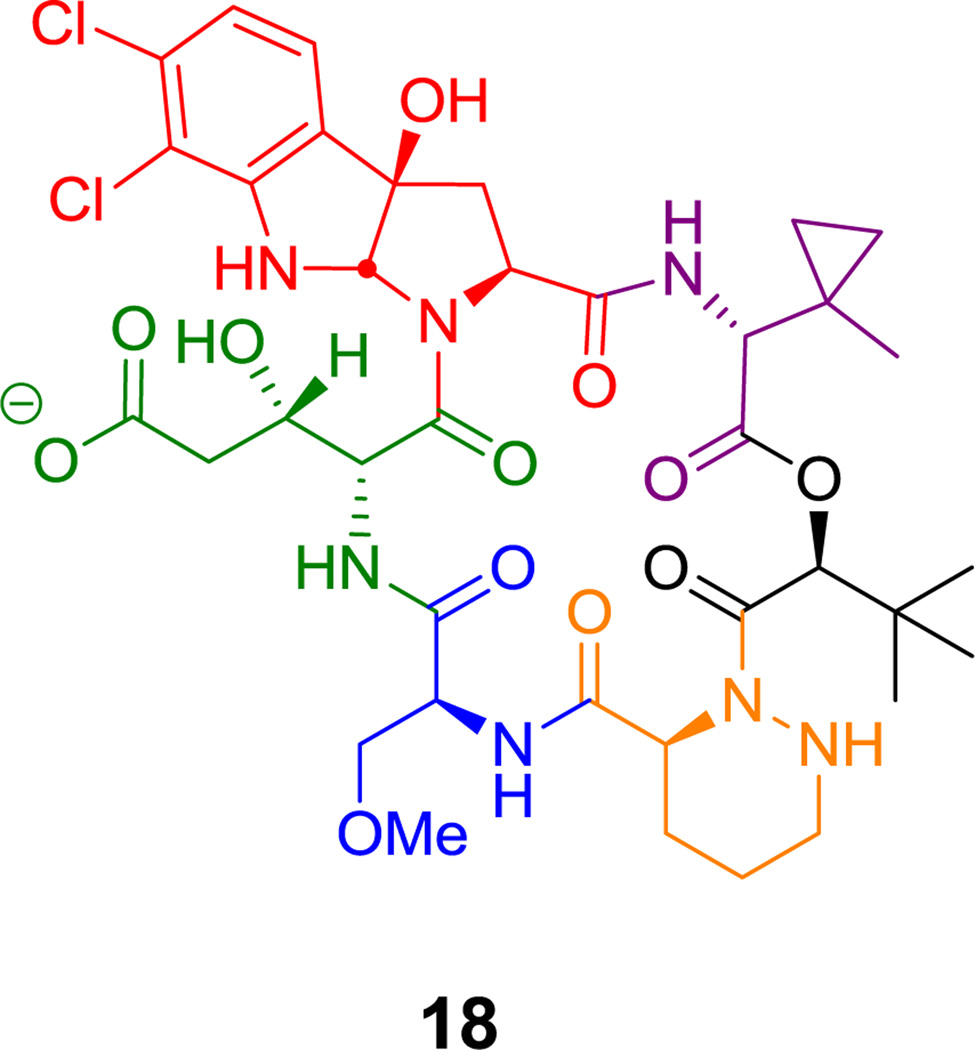

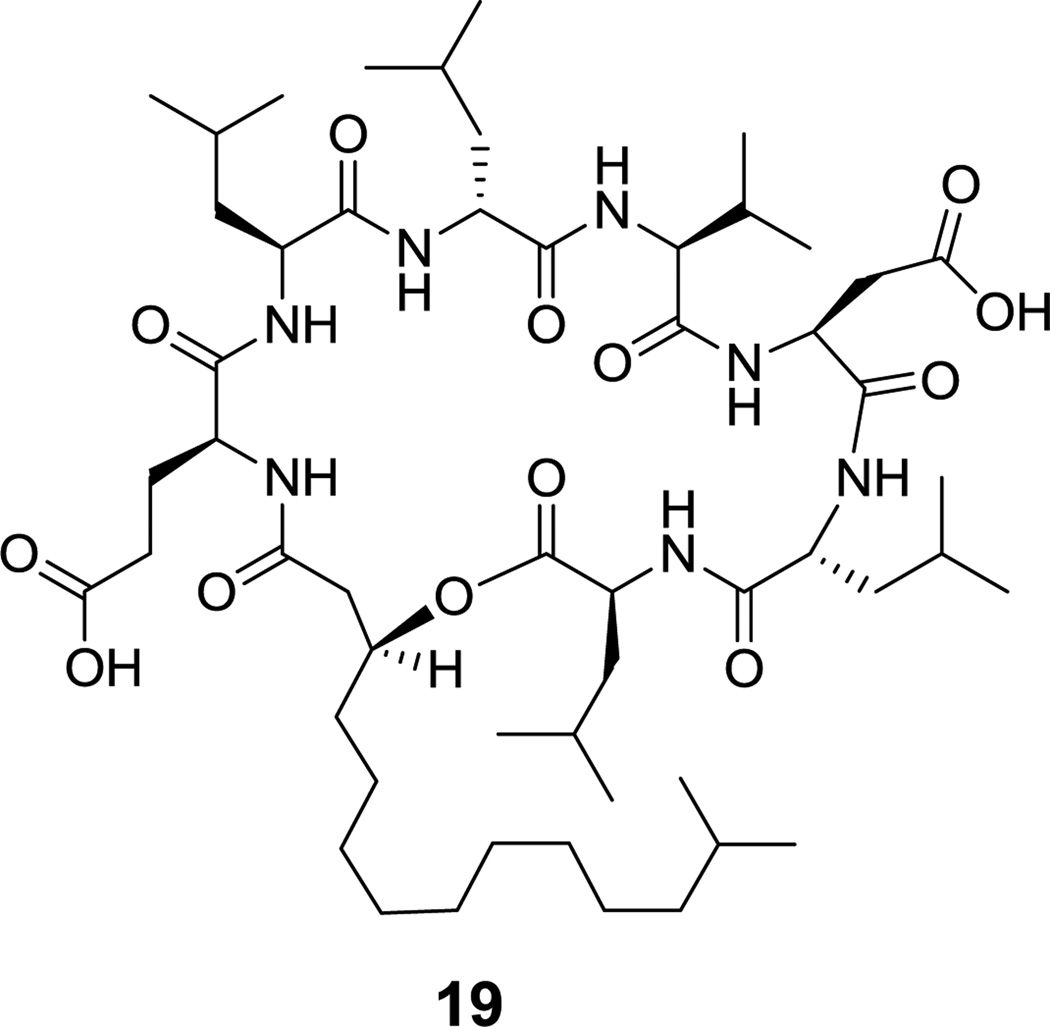

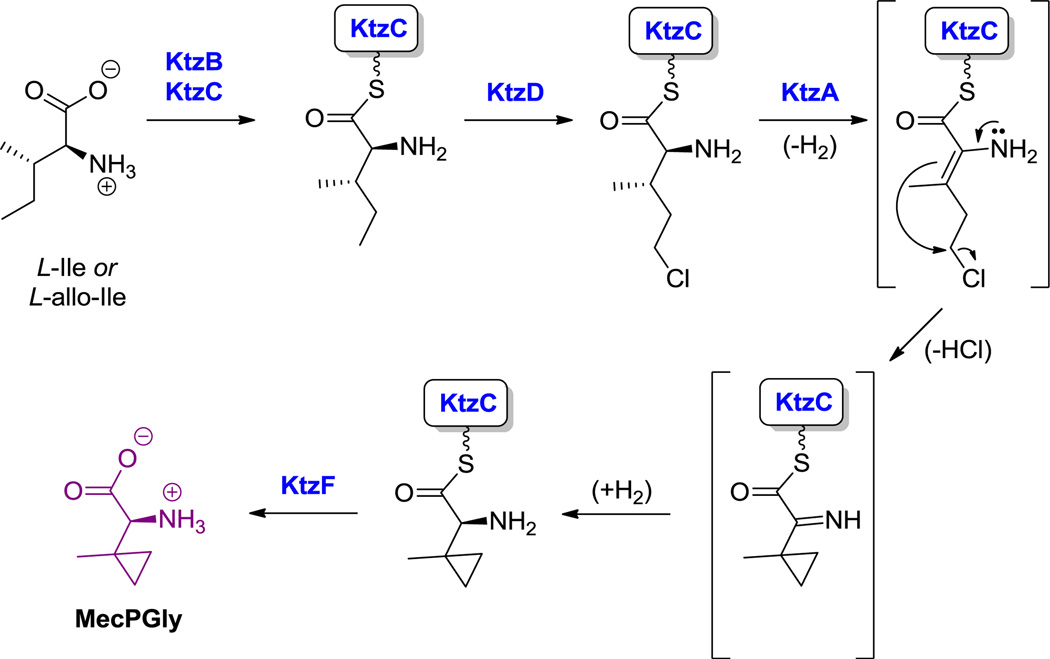

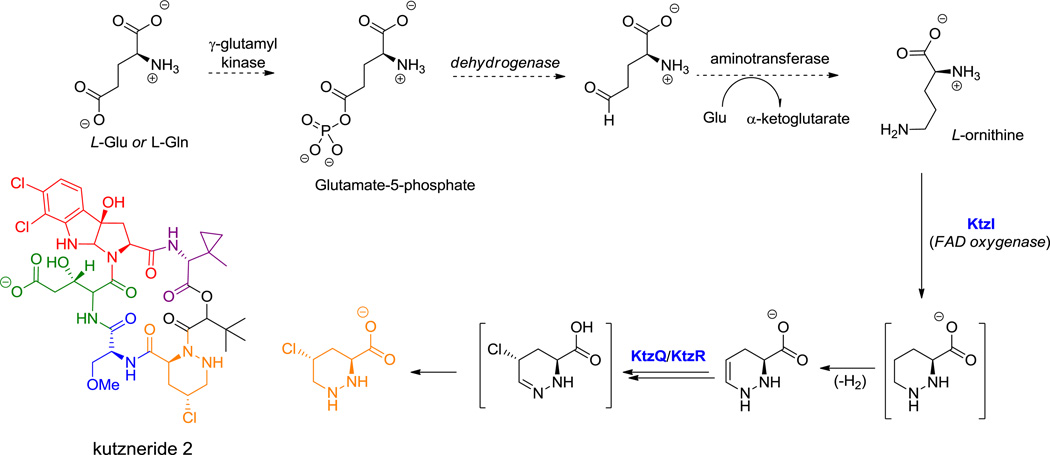

Alternatively an α-hydroxy acid building block incorporated in place of one of the amino acids can form a macrolactone, as in the kutznerides (e.g. kutzneride 1 (18), Figure 6).[68] A variant occurs in the N-acylated lipopeptide surfactin (19, Figure 7), where a β-OH fatty acyl chain participates in macrolactone formation.[69]

Figure 6.

Kutzneride 1, a cyclic hexa(depsi)peptide. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = dichloropyrroloindoline carboxylate, blue = L-O-methyl-Ser, green = (2R,3S)-β-hydroxy-Glu, purple = methylcyclopropyl-Gly (MeCPGly), orange = piperazate.

Hyperlink 9: MecPGly formation in kutzneride biosynthesis.

KtzA: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429059

KtzB: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429060

KtzC: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429061

KtzD: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429062

KtzF: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429064

Hyperlink 10: Piperazate formation in kutzneride biosynthesis.

KtzI: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429067

KtzQ: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429075

KtzR: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/157429076

Hyperlink 11: Hypothetical SAM mediated O-methylation biosynthesis.

Figure 7.

Surfactin, a β-hydroxycarboxylic lactone

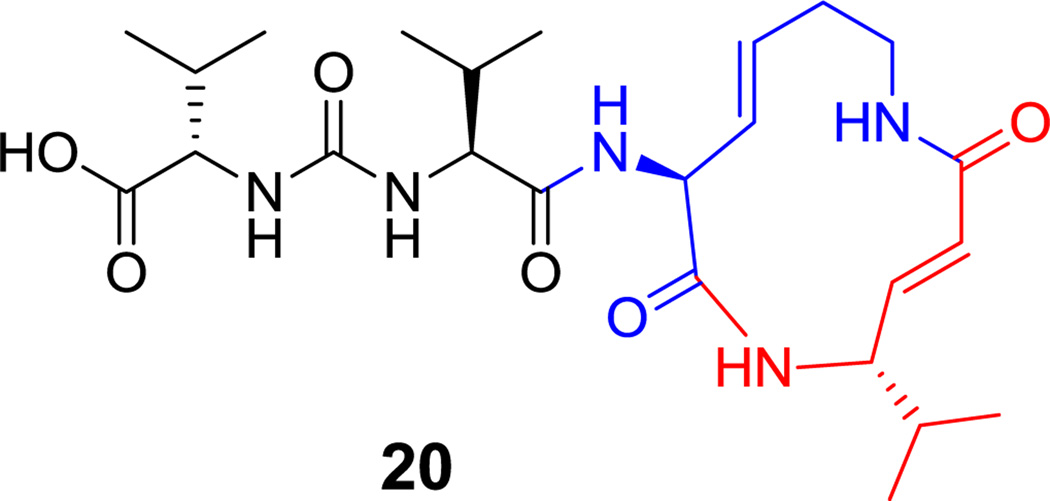

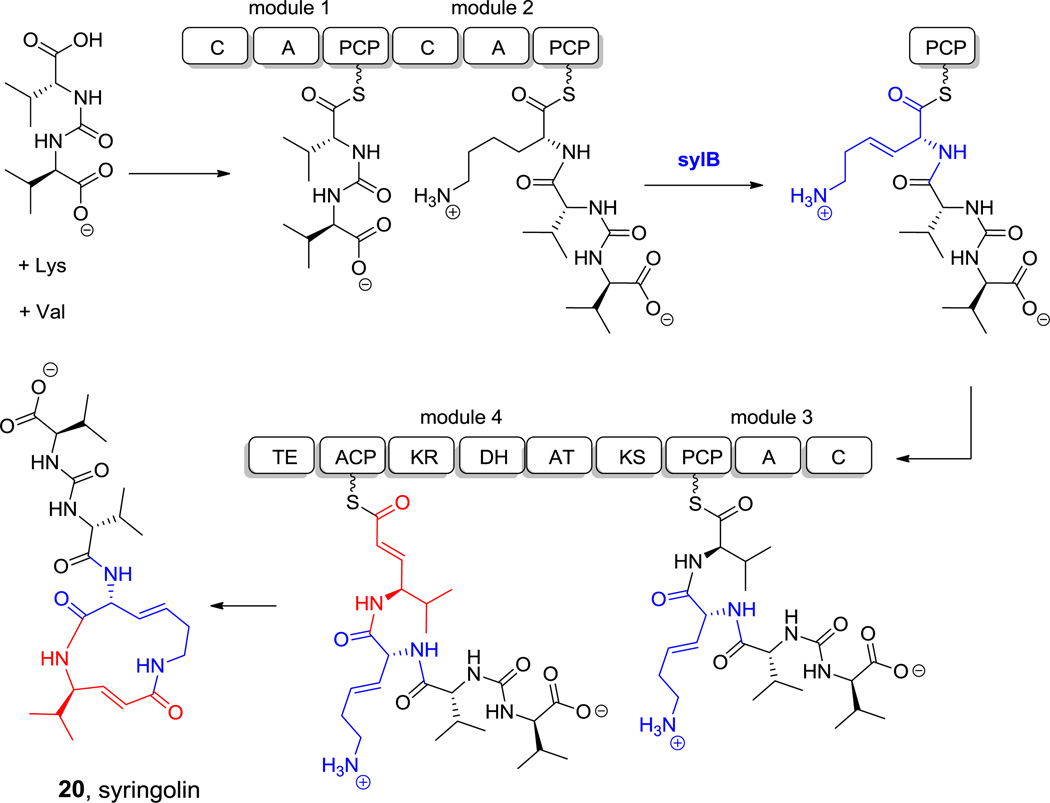

Among the smallest natural peptide macrocycles is the twelve-atom macrolactam found in the proteasome inhibitor syringolin A (20, Figure 8).[70,71] It has a stem-loop structure with a macrocyclic lactam derived from only two residues, both noncanonical. One is a Δ3-lysene that may arise from dehydration of a 3-OH-Lys residue.[70] The other is a vinyl-Val formed by an NRPS-PKS hybrid module (see section 6.1 below). The conjugated enamide derived from vinyl-Val is the electrophilic moiety of syringolin that irreversibly inactivates the proteasome by capture of the active site Thr1-NH2.[72]

Figure 8.

Syringolin A. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-vinyl-Val, blue = L-Δ-3-Lysene.

Hyperlink 12: Biosynthesis of vinylvaline and 3,4-dehydrolysine on the syringolin (syl) synthase.

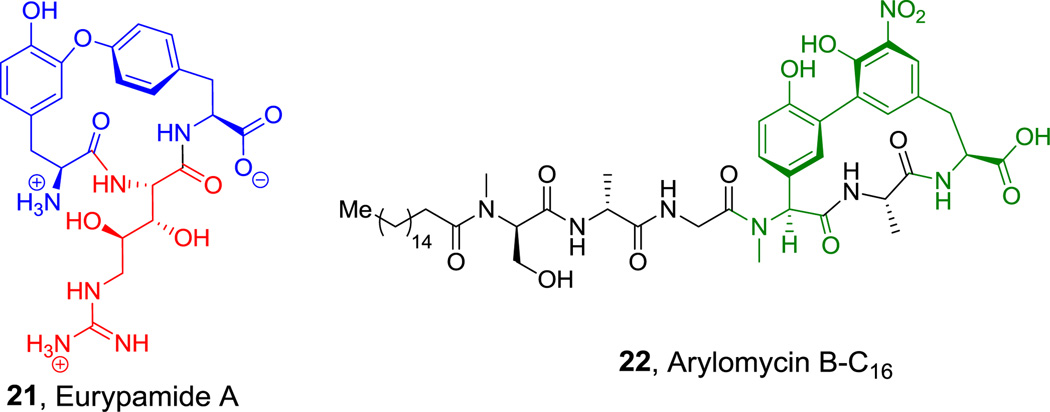

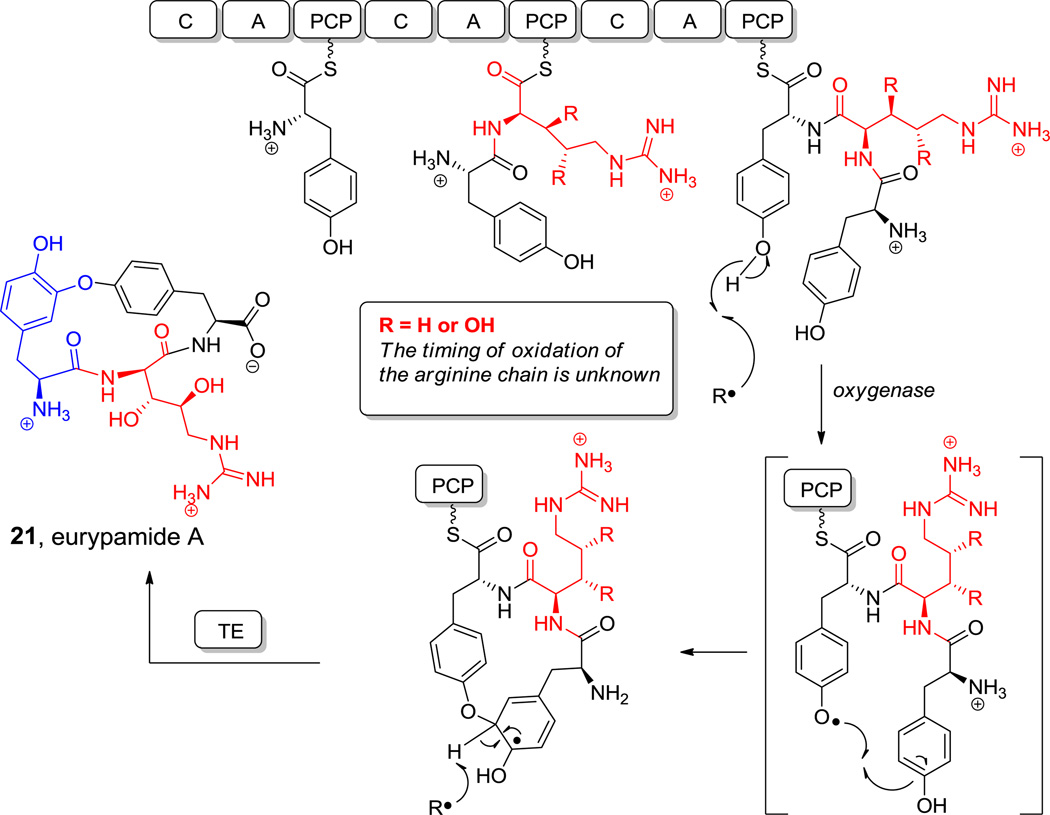

Eurypamide A (21, Figure 9) is a three-residue peptide macrocycle, isolated from a presumed bacterial community in Palauan sponges,[73] containing a Tyr-O-Tyr crosslink similar to the analogous Tyr-C-Tyr crosslink in arylomycin antibiotics (e.g. arylomycin B-C16 (22), Figure 9).[74,75] The side chain aryl ether in 21 is thought to arise from one electron phenoxy radical chemistry via iron-based oxygenase action on the two tyrosine side chains of a tripeptide precursor.[76] These crosslinks set the constrained architecture in 21 and 22 (Figure 9).[75,77] Eurypamide A (21) also harbors the unusual 3R,4S-dihydroxy-L-Arg,[77] although the timing of bis-hydroxylation is unknown. It could occur on the free amino acid, the presumed aminoacyl-S-T NRPS assembly line intermediate, or the released peptide.

Figure 9.

Aryl ethers and aryl-aryl linkages in cyclic peptides. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2S,3R,4S)-3,4-dihydroxy-Arg, blue = Aryl ether (L-Tyr/(R)-β-Tyr), green = Aryl ether (L-(p-hydroxy)phenyl-Gyl/L-m-nitro-Tyr).

Hyperlink 13: Hypothetical pathway for eurypamide biosynthesis.

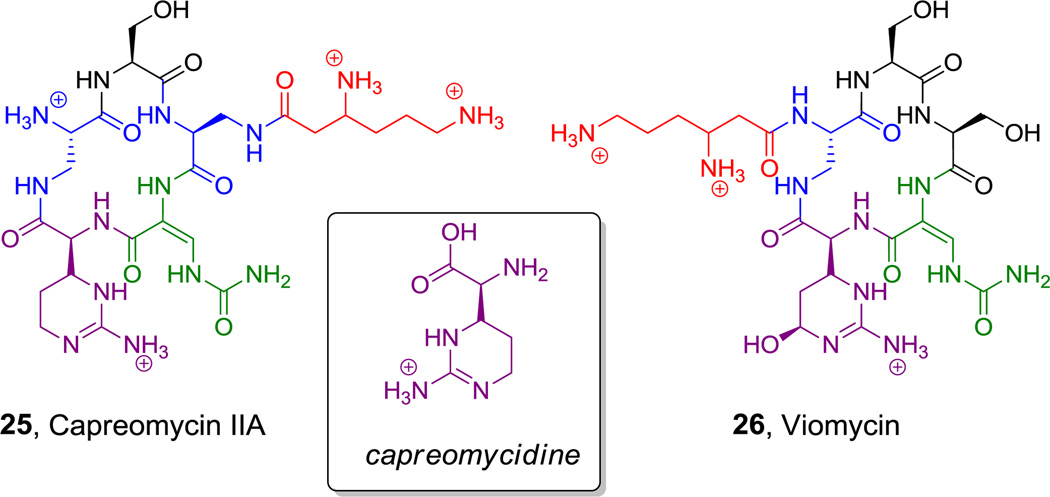

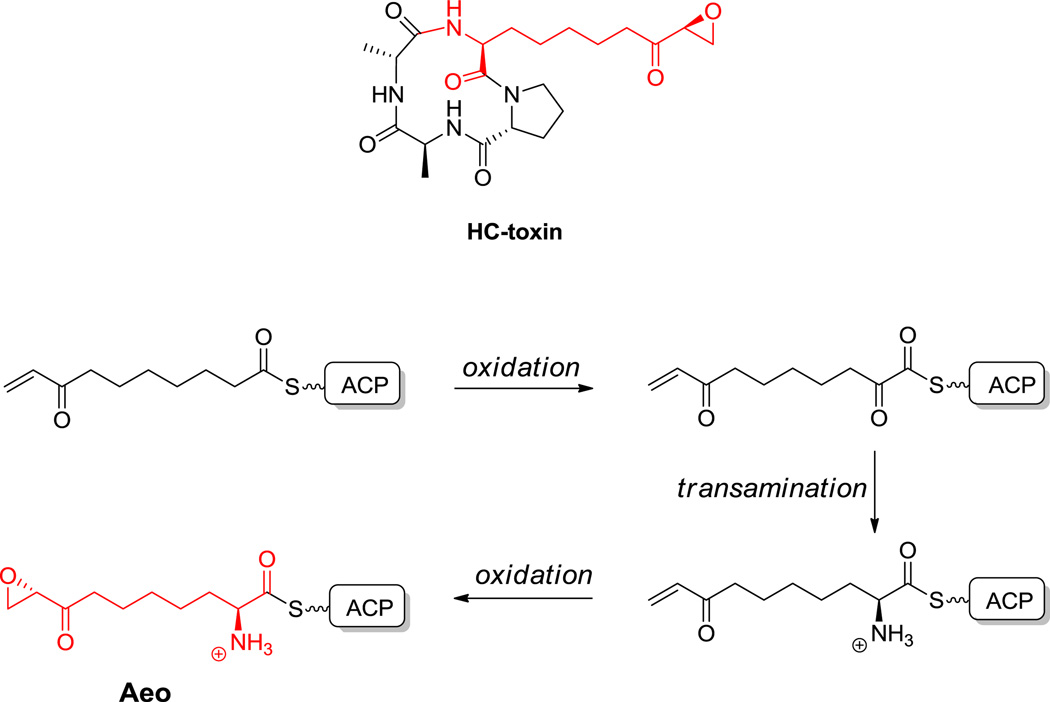

Macrocyclic tetrapeptides are also found in the histone deactylase (HDAC) inhibitors of the trapoxin (21) and HC toxin class (22, Figure 10).[78,79] This compact architecture presents the epoxyketone side chain of the unusual 2-amino-8-oxo-9,10-decanoate (Aeo) epoxy residue to the active site of HDACs for irreversible capture of the active site nucleophile.[80] The strategy for construction of the Aeo monomer is discussed in section 6.2 below.

Figure 10.

Natural products containing L-Aeo. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-2-amino-8-oxo-9,10-decanoate (Aeo).

Hyperlink 14: Hypothetical pathway for Aeo biosynthesis.

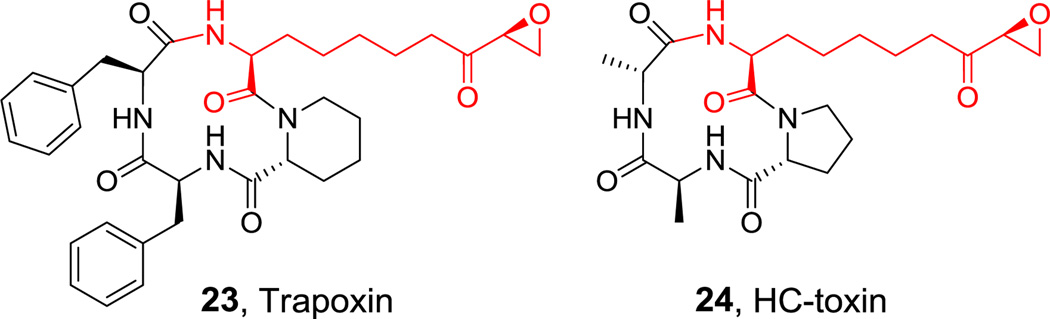

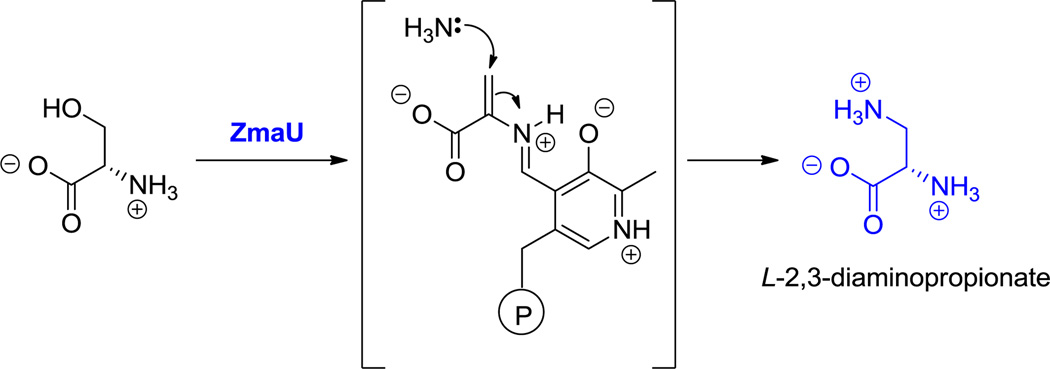

Cyclic pentapeptide scaffolds are found in the antitubercular drugs, capreomycin (23, Figure 11A) and viomycin (24, Figure 11b).[49] They are notable for the presence of a 2,3-DAP as the macrolactam-forming residue,[44] a β-lys residue in the stem of the stem-loop structure, the cyclic arginine derivative capreomycidine, and a ureidodehydroAla residue. These unusual amino acids play important roles in the ability of both antibiotics to bind across the 30S–50S subunit interface on bacterial ribosomes.[81] The biosynthesis of the β-Lys and capreomycidine building blocks are discussed in sections 5.1.2 and 5.6.3, respectively.

Figure 11.

Natural products containing a capreomycidine moiety. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = β-Lys, blue = L-2,3-DAP, green = (E)-ureidodehydro-Ala, purple = capreomycidine and δ-hydroxycapreomycidine.

Hyperlink 15: Formation of L-2,3-diaminopropionate (2,3-DAP) from L-serine in zwittermycin biosynthesis

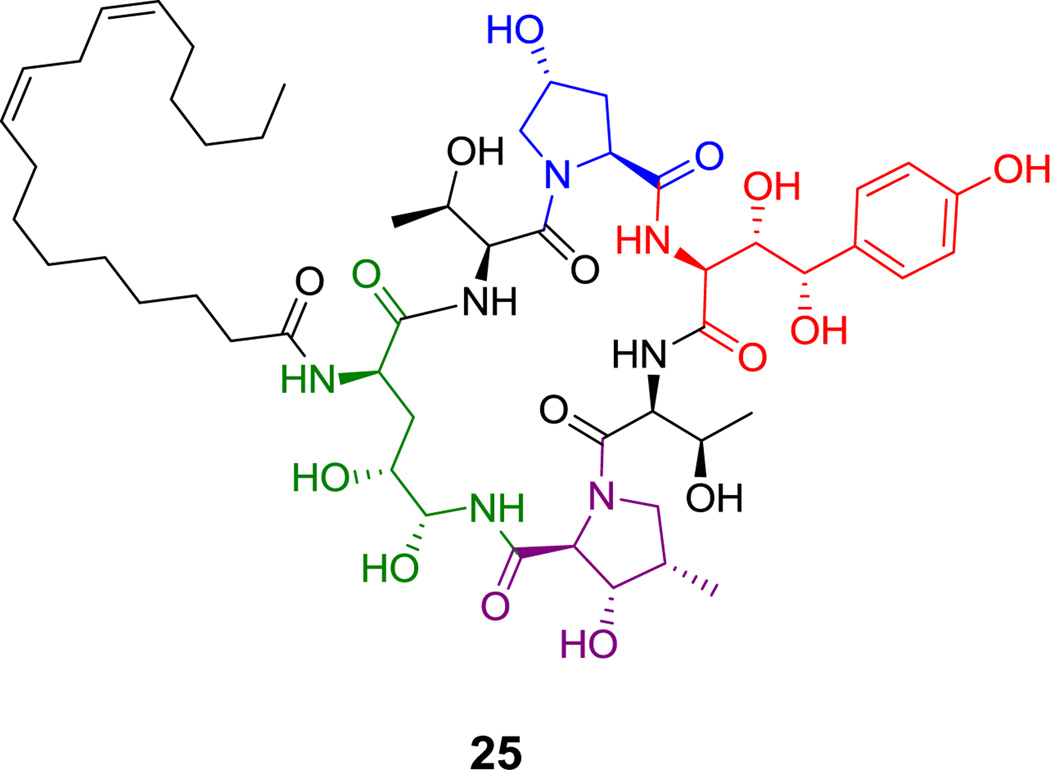

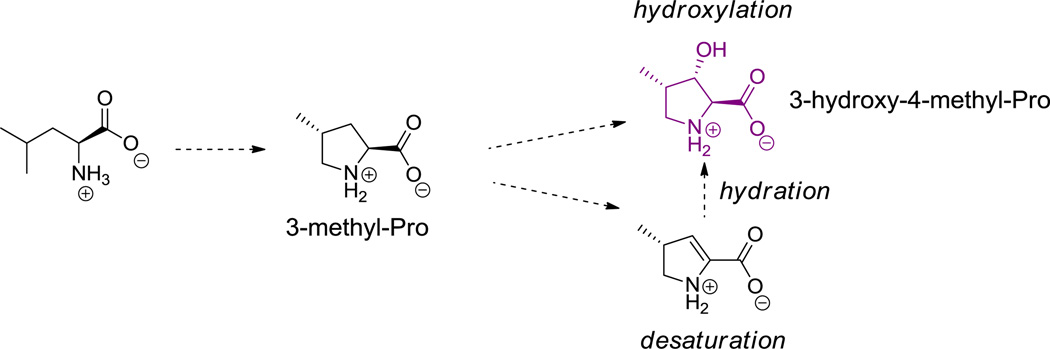

Cyclic hexa(depsi)peptides include the kutzneride family of hexapeptidolactones (e.g. 18, Figure 6)[82] with antifungal activity and the echinocandins (e.g. echinocandin B (25), Figure 12),[83,84] which target the fungal 1,3-glucan synthases. Kutznerides have five nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks and an unusual hydroxy-acid (t-butylglycolate) that participates in forming the macrolactone framework.[68,68] The echinocandins have a hexapeptide scaffold with a metastable hemiaminal linkage between N5 of an N1-acylated ornithine and the carbonyl of a 3-methyl-4-hydroxyproline residue. Both the ornithine side chain and an unusual homotyrosine side chain are dihydroxylated; the timing of the hydroxylations is unknown.

Figure 12.

Echinocandin B. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2S,3S,4S)-3,4-dihydroxyhomo-Tyr, blue = (2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-Pro, green = (2R,4R,5R)-4,5-dihydroxy-Orn, purple = (2S,3S,4S)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-Pro.

Hyperlink 16: Two possible routes for the biosynthesis of L-3-methyl-4-hydroxy-Pro from L-leucine

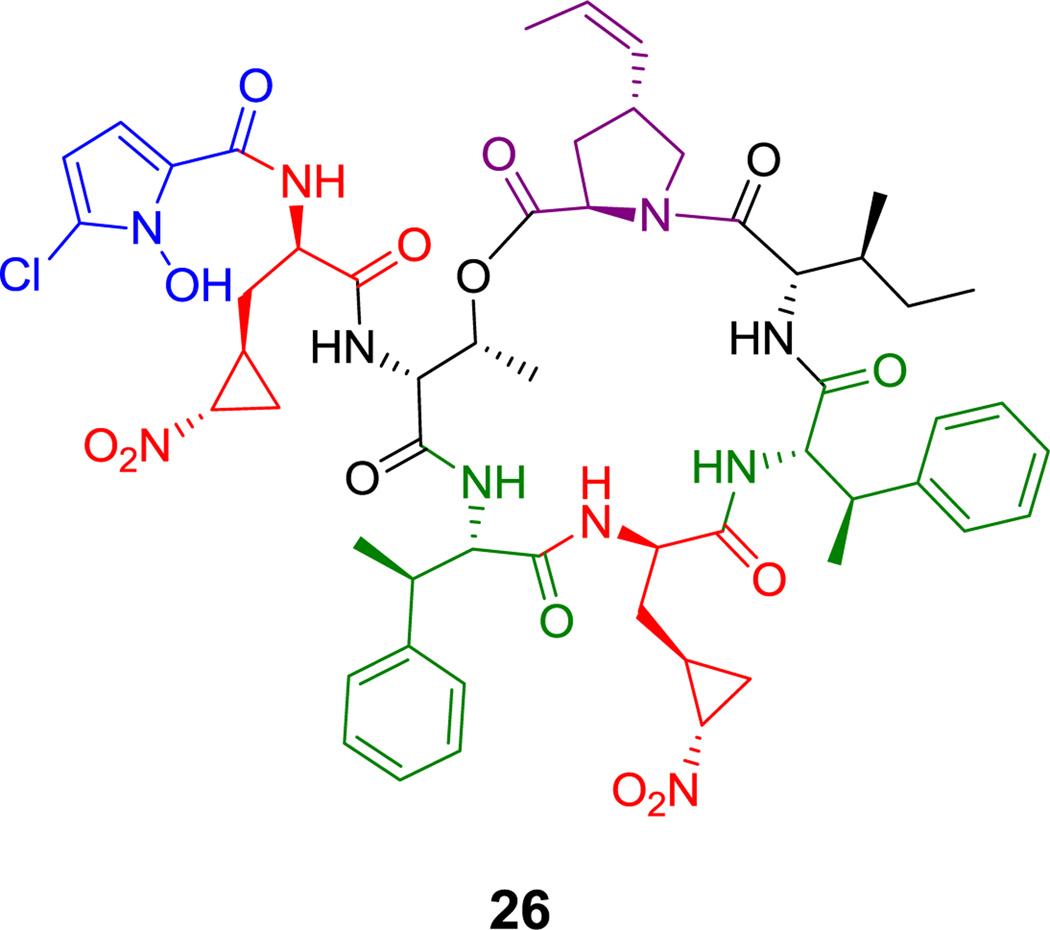

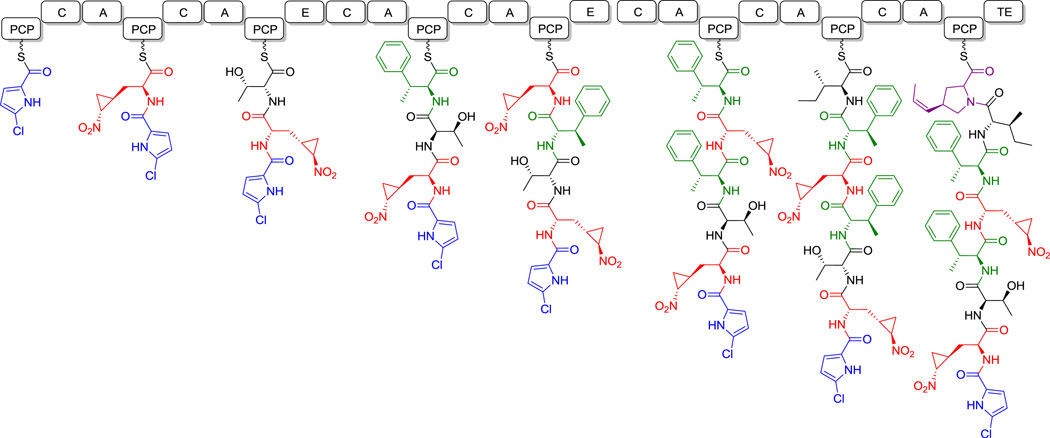

Hormaomycin (26, Figure 13) is another hexapeptidolactone that is also replete with noncanonical amino acid units, including two β-methyl-Phe residues, a propenyl-proline, and a remarkable nitrocyclopropyl-alanine residue.[85] The OH group of a Thr residue participates in the formation of the hexapeptidolactone macrocycle; its amino group is acylated with a dipeptide moiety containing another nitrocyclopropyl-Ala and a proline-derived N-OH-2-chloropyrrole carboxyl residue. A schematic for chain elongation of this remarkable natural product is shown in hyperlinked form in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Hormaomycin. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = Nitrocyclopropyl-Ala, blue = 5-chloro-1-hydroxypyrrole-2-carboxylate, green = (2S,3R)-β-methyl-Phe, purple = (2R,4R)-4-((Z)-propenyl)-Pro.

Hyperlink 17: Hormaomycin biosynthesis.

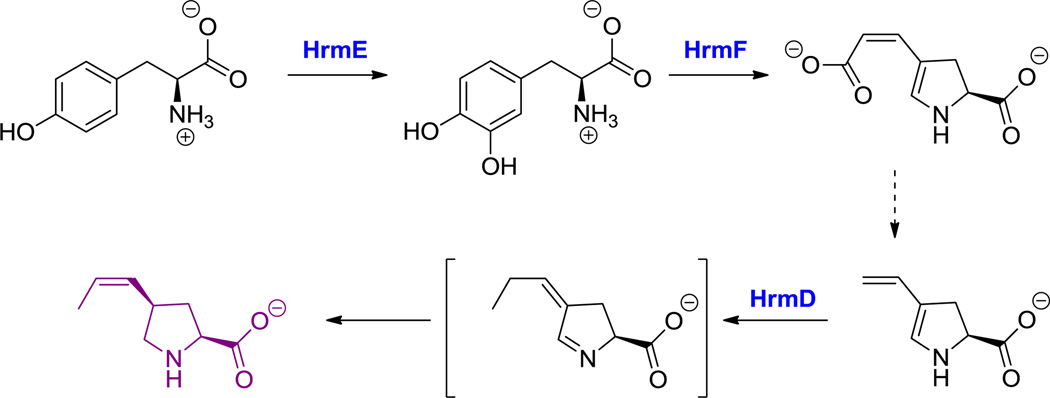

Hyperlink 18: Propenylproline formation in hormaomycin biosynthesis.

HrmD: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/335346673

HrmE: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AEH41783.1

HrmF: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/335346656

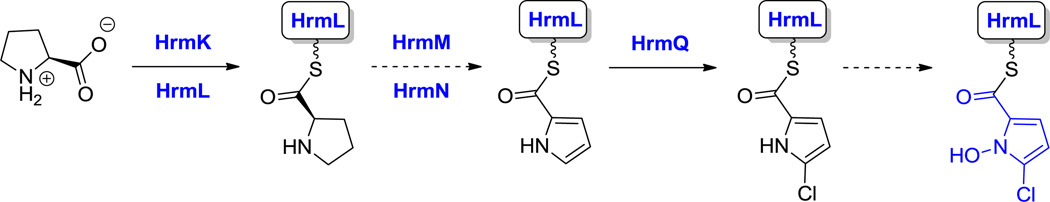

Hyperlink 19: Proposed 5-chloropyrrole-2-carboxylate formation in hormaomycin biosynthesis.

HrmK: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/AEH41789.1

HrmL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/335346662

HrmM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/335346663

HrmN: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/335346664

HrmQ: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/190610819

Hyperlink 20: Two possible pathways for nitrocyclopropylalanine formation in hormaomycin biosynthesis.

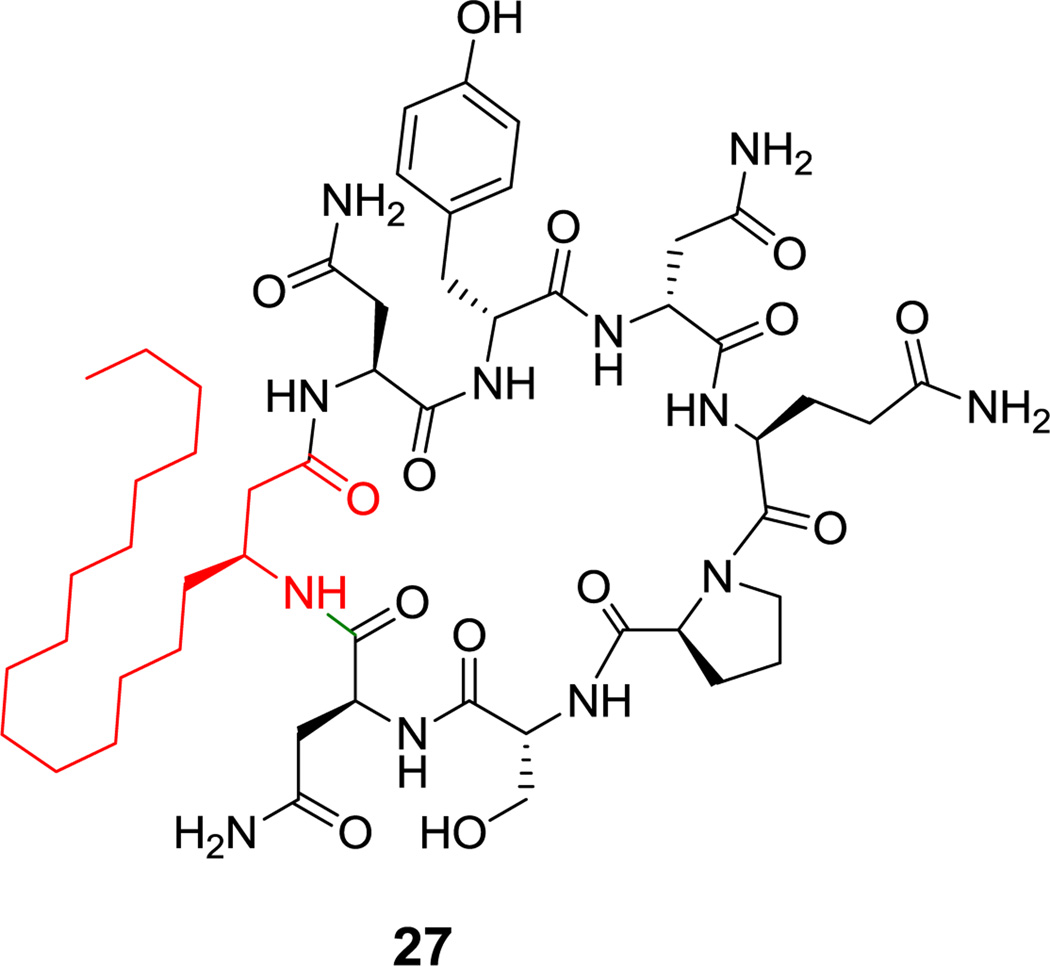

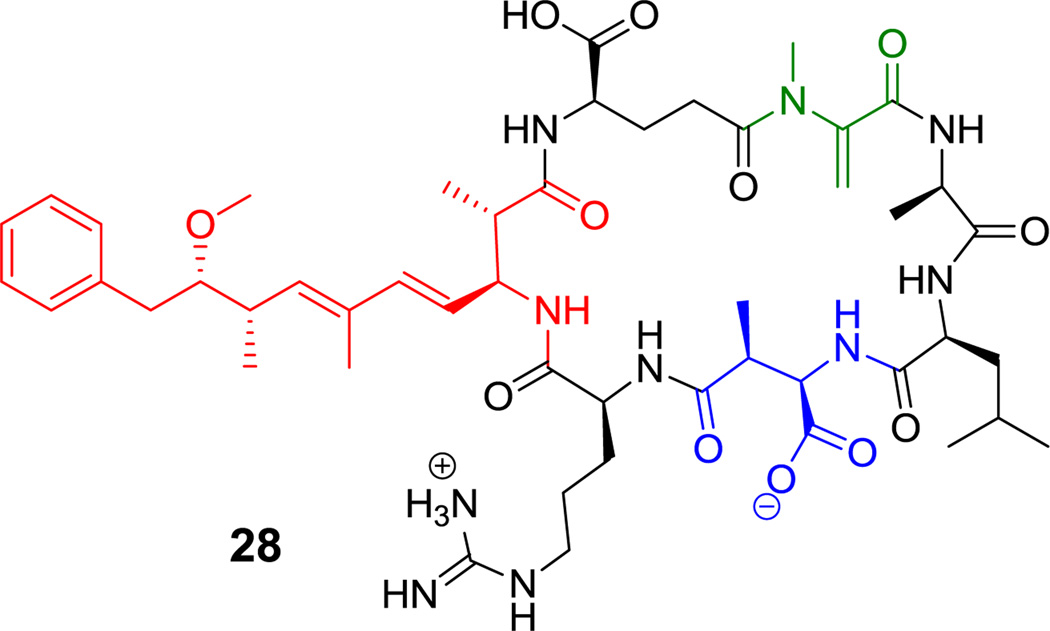

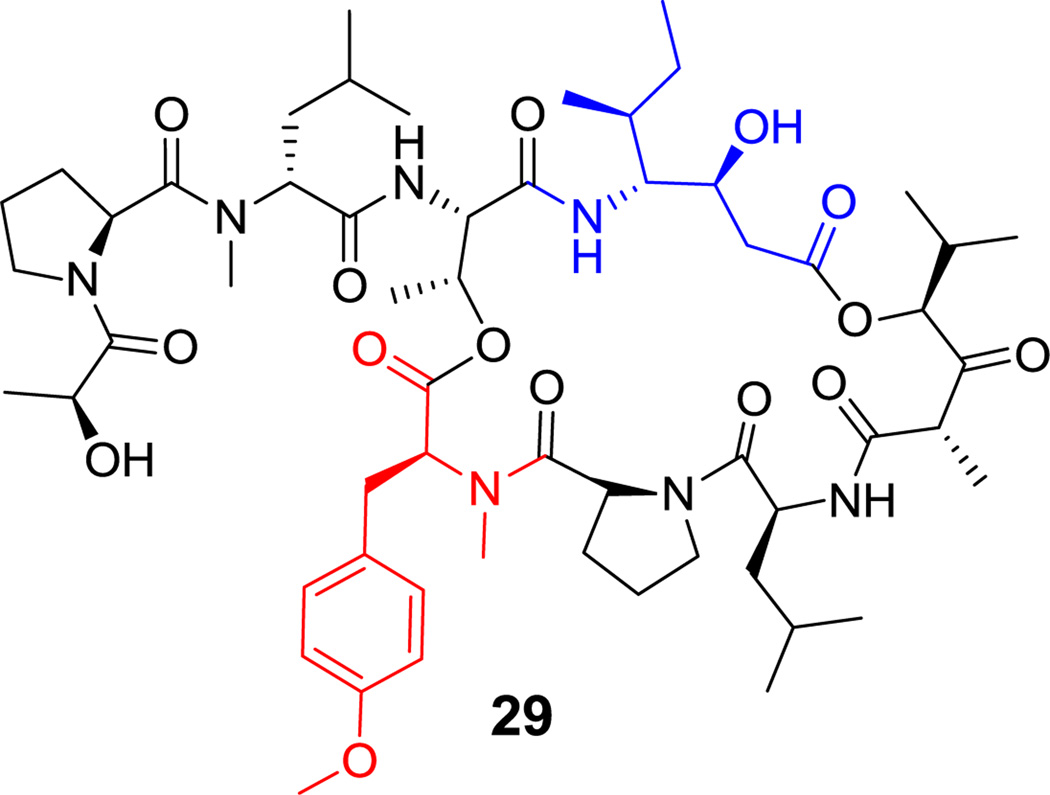

Figure 13. Heptapeptidyl frameworks are found in several natural products, including the N-acylated mycosubtilin (27, Figure 14),[86] and surfactin lipopeptides from Bacillus spp (see Figure 7).[69] The β-hydroxy substituent of the fatty acyl chain engages in macrolactonization in surfactin, while the fatty acyl chain in mycosubtilin instead bears a β-amino group that makes a macrolactam. Callipeltin B (16, Figure 4) is a sponge-derived heptadepsipeptide with a D-allo-Thr residue and also a β-methoxy-Tyr residue.[64] The antibacterial polymyxins (e.g. 15, Figure 3) have multiple 2,4-DAB residues, one of which participates in the heptapeptidyl macrolactam loop.[63] These side chains are cationic under physiologic conditions and may serve to sequester this antibiotic by interaction with anionic lipopolysaccharides on Gram-negative bacterial pathogens.[87] Cyanobacteria make a variety of toxic cyclic peptides via a nonribosomal strategy;[88] among them are the microcystins (e.g. microcystin LR (28), Figure 15), cyclic heptapeptides that target protein phosphatase I for inhibition.[89] More than 70 structural variants are known, reflecting promiscuity in the heptamodule NRPS assembly lines. Among its unusual residues are dehydroalanine, β-Me-D-isoaspartate, the polyketide-derived Adda, and isoglutamate. The didemnins (e.g. didemnin B (29), Figure 16) are cyclic heptadepsipeptides isolated from bacterial symbionts of sea squirts,[90] and have been of interest for their immunosuppressive properties.[91] Among the building blocks of special interest is the isostatine residue, with a 3-OH, 4-NH2 grouping, assembled by a hybrid NRPS-PKS module discussed in section 6.1.

Figure 14.

Mycosubtilin. Nonproteinogenic amino acid: red = (S)-β-aminostearate.

Figure 15.

Microcystin LR. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = vinylogous β-Ala, blue = (2R,3S)-β-methylaspartate, green= dehydro-Ala.

Figure 16.

Didemnin B. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-O-Me-Tyr, blue = (3S,4R,5S)-isostatine.

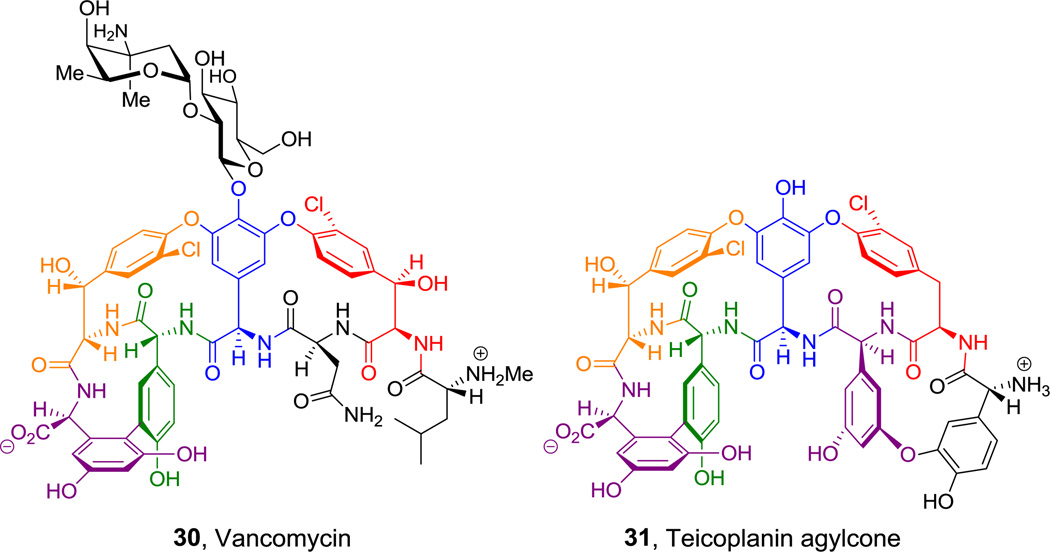

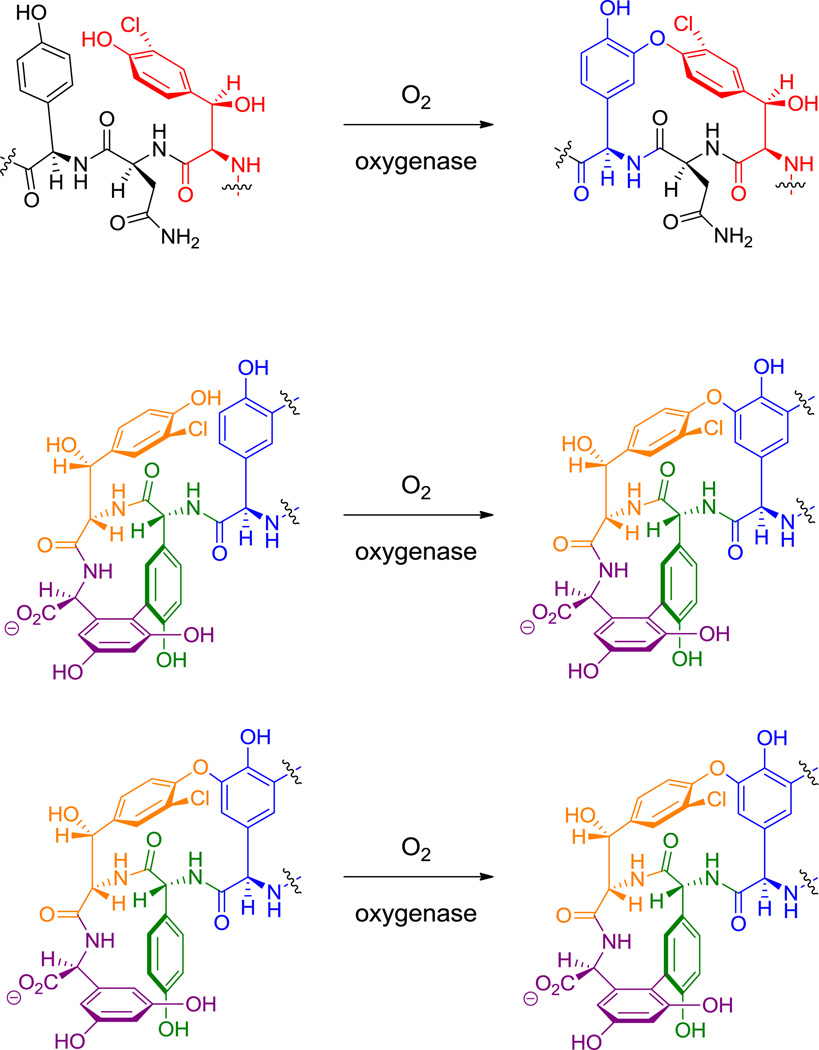

A distinct mode of converting a linear heptapeptidyl framework into a constrained architecture occurs in the maturation of the T7-domain tethered linear heptapeptidyl intermediate in assembly of the antibiotic vancomycin (30, Figure 17).[92,93] Three heme iron-containing monooxygenases act to generate phenoxy radical intermediates to couple residues 2–4, 4–6, and 5–7.[94,95] Each of these five participating residues is nonproteinogenic, and has an accessible redox potential for a radical coupling reaction. Residues 2 and 6 are β-OH-Tyr. Residues 4 and 5 are 4- OH-phenylglycines, and residue 7 is a 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine. In teicoplanin (31, Figure 17) a fourth crosslink occurs between Tyr1 and 3,5-(OH)2-Phegly3, such that all seven residues participate in a total of four crosslinks. The formation of these unusual aryl amino acids is discussed below.

Figure 17.

Vancomycin and Teicoplanin. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2R,3R)-m-chloro-(or β-hydroxy-m-chloro)Tyr aryl ether, blue = 3,5-dihydroxy-Tyr aryl ether, green = p-hydroxyphenyl-Gly aryl-aryl, purple =3,5-dihydroxyphenyl-Gly arly-aryl or aryl ether, orange = (2S,3R)-β-hydroxy-m-chloro-Tyr aryl ether.

Hyperlink 21: Aryl-aryl and aryl ether crosslinking in vancomycin.

Hyperlink 22: Aryl amino acid hydroxylation.

Hyperlink 23: Chlorination of amino acids

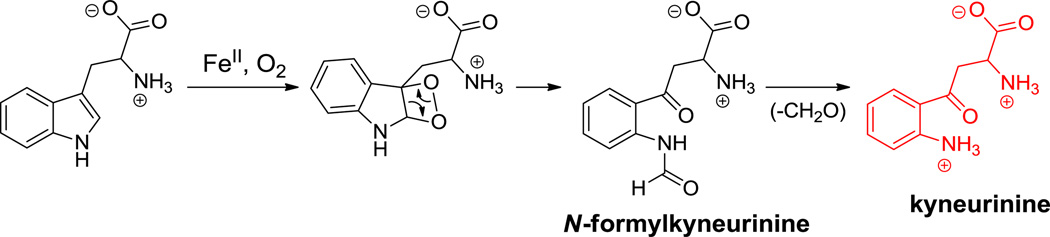

Daptomycin is a clinically used N-acylated 13-residue NRP antibiotic (17, Figure 5).[96] It has a 10-residue macrolactone ring, fashioned from the OH group of Thr4 and the carbonyl of residue 13 that is the nonproteinogenic kynurenine, which arises from oxidative metabolism of tryptophan.[97] It also harbors a nonproteinogenic 3-methyl-Glu residue 11 as one of several side chain carboxylates that coordinate Ca2+ ions and change conformation to a membrane active form.

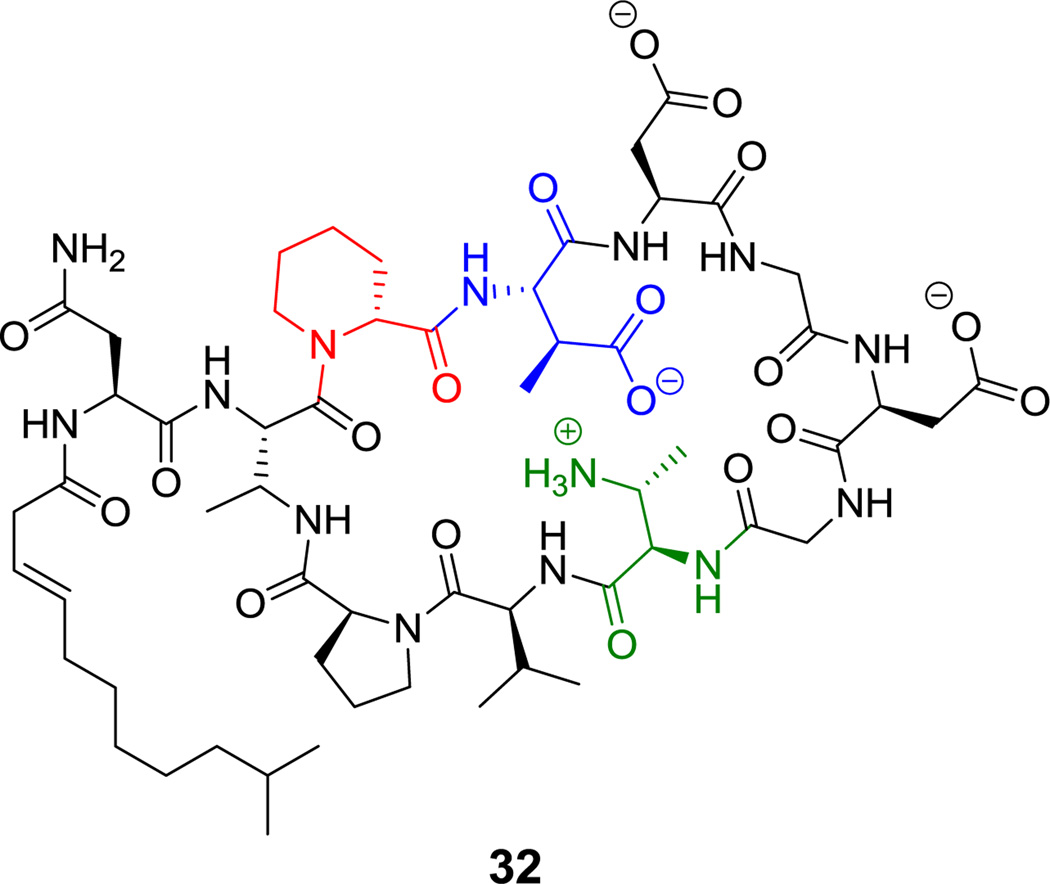

Friulimicin is another nonribosomally produced lipopeptide (32, Figure 18),[45] with a decapeptidyl macrolactam between a 2,3-diaminobutyryl residue at position 2 and Pro11. Fruilimicin binds the lipid II carrier required for peptidoglycan formation in bacterial cell wall assembly.[98] Friulimicin also has additional nonproteinogenic amino acid building blocks, including pipecolate3, β-Me-Asp4 and another 2,3-DAB.

Figure 18.

Friulimicin. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = D-pipecolate, blue = β-methyl-Asp, green = 2,3-DAB.

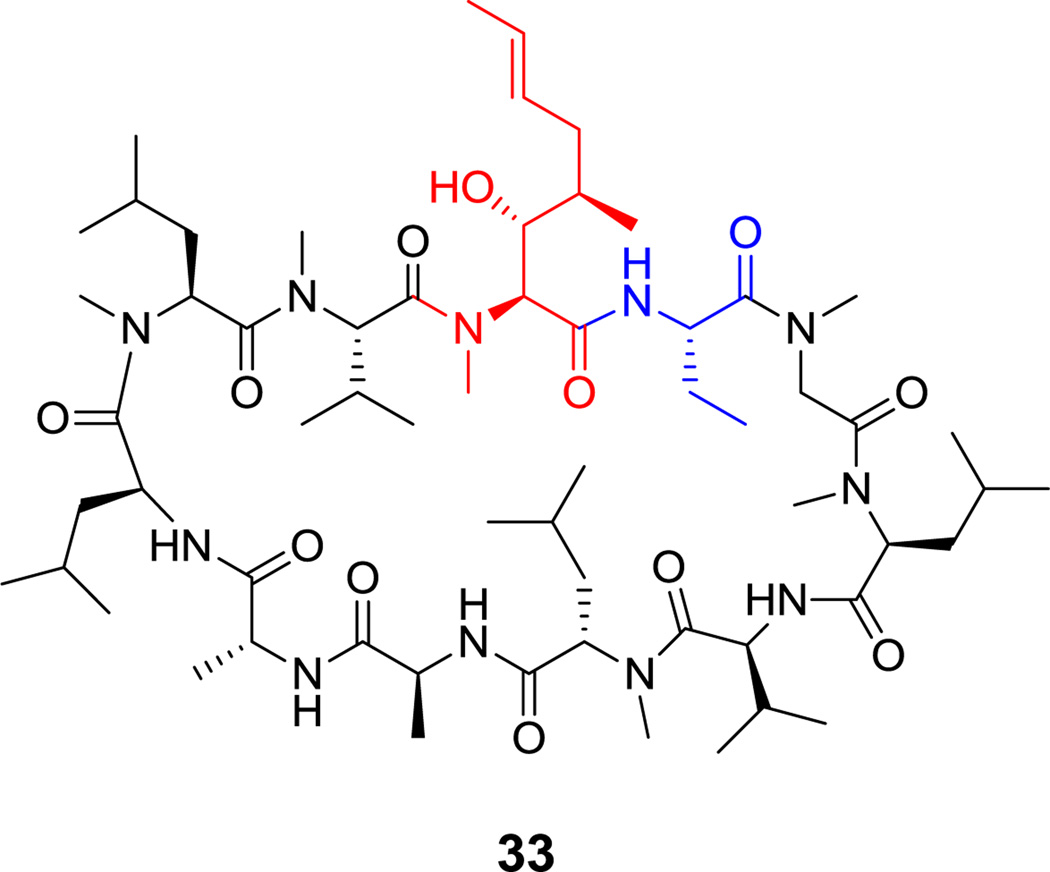

An 11-residue macrolactam is formed in the last step of biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant undecapeptide cyclosporin A (33, Figure 19), when D-Ala1 is coupled head-to-tail to the thioesterified carbonyl of L-Ala11 by the megadalton NRPS cyclosporin synthetase.[99] Seven of the 11 residues of cyclosporin are N-methylated. There is also a nonproteinogenic 2- aminobutyryl residue and a methylbutenylthreonine residue that is generated by a PKS assembly line with subsequent transamination.[100]

Figure 19.

Cyclosporin A. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = (2S,3R,4R)-(E)-butenylmethyl-Thr, blue = L-α-aminobutyrate.

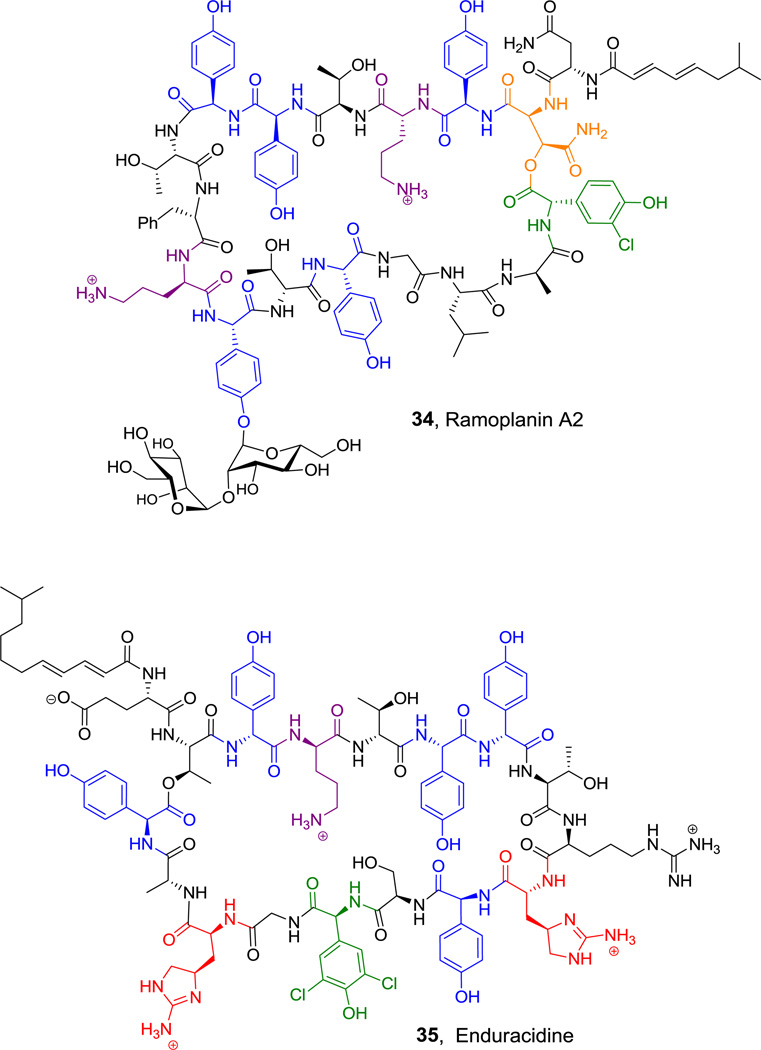

Among the largest nonribosomally generated peptide macrocycles are the ramoplanin A2(34),[101] and related enduracidine (35, Figure 20) antibiotics.[48] In both of these lipid II binders residues 2 and 16 are macrocyclized to yield a 15 residue cyclic framework.[102] Among the noncanonical building blocks are 4-hydroxyphenylglycines and in enduracidine, two cyclic arginine-derived enduracididine residues.

Figure 20.

Ramoplanin and Enduracidine. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = enduracididine, blue = D or L p-hydroxyphenyl-Gly, green = L-3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl-Gly or 3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl-Gly (in 34), purple = D-Orn, orange = (2S,3S)-β-hydroxy-Asp.

4.3. Macrocyclic hybrid nonribosomal peptide-polyketide frameworks

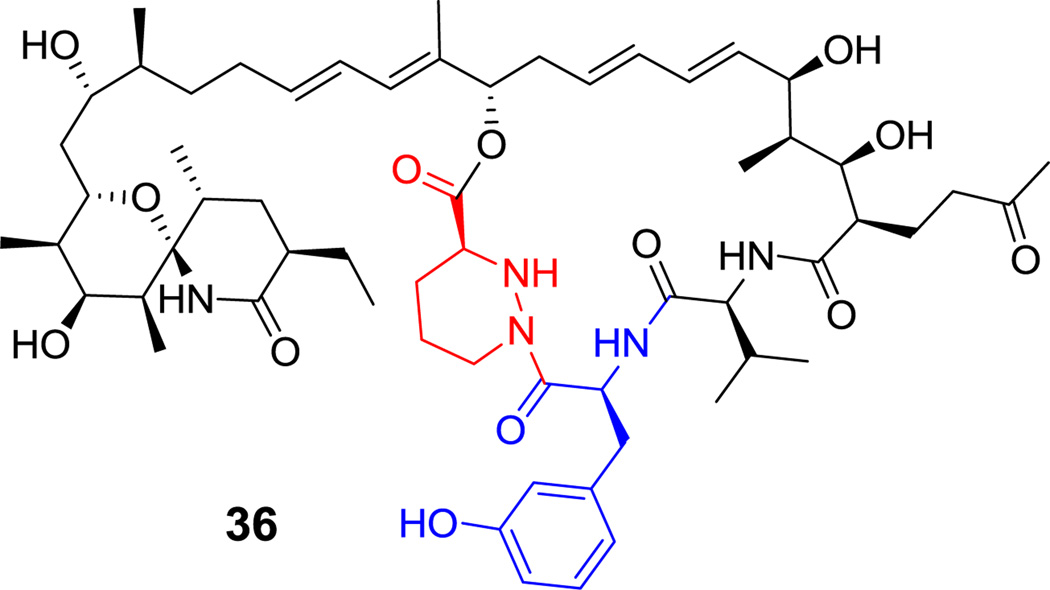

There are also variable macrocyclic ring sizes in hybrid NRP-PK scaffolds. The PKS machinery can generate fully reduced CH2 groups, CHOH, HC=CH, or C=O groups from partial processing of tethered intermediates on the PKS assembly lines.[17,103] These three functional groups can mix and match with the amino acid building blocks, as exemplified by the macrocyclic portion of syringolin A (20, Figure 8), epothilone B (2, Scheme 3) and rapamycin (3, Scheme 3). The naturally occurring immunosuppressant sanglifehrin A (36, Figure 21) has 22 atoms in the macrocycle, spanning 3 amino acids (Val-(m-Tyr)-piperazate) and the rest is polyketide.[104] The phytotoxin coronatine (12, Scheme 5) is produced by hybrid PKS-NRPS machinery in the plant pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae through ligation of a cyclopropyl amino acid to the polyketide fragment coronafacic acid.[34,105,106]

Figure 21.

Sanglifehrin A. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-piperazate, blue = L-meta-Tyr.

5. Generation of Nonproteinogenic Amino Acid Building Blocks

5.1 D-Amino Acids and β-Amino Acids

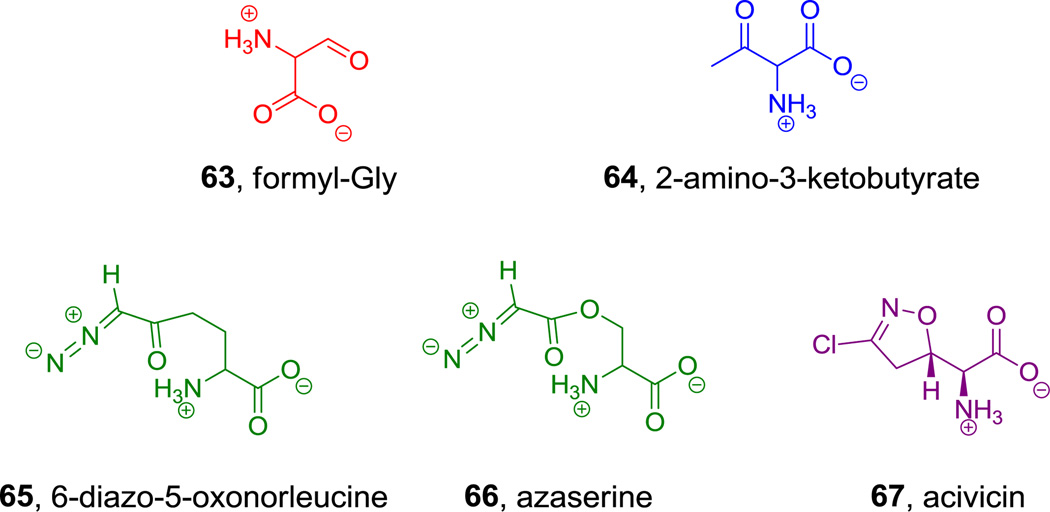

As noted above, microcystin LR (28, Figure 15) has a D-isomer of β-methyl isoaspartate, and vancomcyin and teicoplanin (30 and 31, Figure 17) have D-hydroxyphenylglycine units, which engage in the crosslinking of the rigid scaffold. Cyclosporin has one D-Ala residue (33, figure 24). More generally, many dozens of D-amino acid residues are found in nonribosomal peptide scaffolds. Also there are β-amino acids, as in the side chain β-Lys residue in the antitubercular agents viomycin and capreomycin (25 and 26, Figure 11), as well as β-Phe in andrimid and β-Tyr in ene-diyne antitumor natural products.[107,108]

Figure 24.

Aldehyde, imine, ketone, and diazo-containing amino acids. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = formyl-Gly, blue = 2-amino-3-ketobutyrate, green= α-diazoketone or α-diazoester, purple = acivicin.

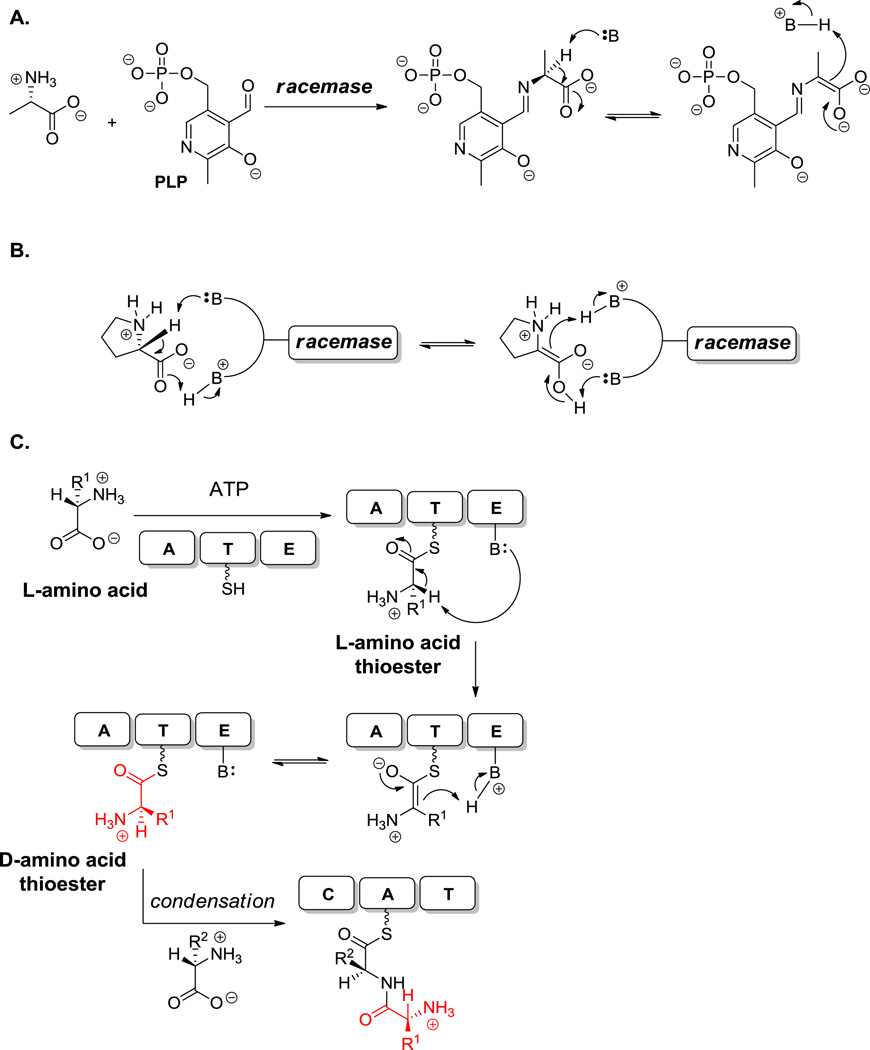

5.1.1 Racemases and Epimerases

The most common route to D-amino acids is by action of amino acid racemases and epimerases to convert L-isomers to D-isomers. For example, D-Ala in bacterial peptidoglycan layers and cyclosporine are generated by prototypic pyridoxal-phosphate (PLP)-dependent racemases that generate the stabilized C2 carbanion from Ala=PLP aldimine followed by stereorandom reprotonation (Scheme 6A).[35,36] On the other hand, the glutamate, proline and diaminopimelate racemases are PLP-independent and use two active site bases – one protonated as conjugate acid, the other deprotonated as initiating active site base – to catalyze Cα stereochemical equilibration (Scheme 6B).[109] Broad specificity PLP racemases acting on a range of proteinogenic amino acids have been isolated from Pseudomonas putida,[110] as has a threonine epimerase which is representative of diastereomer interconversion (L-Thr to D-allo Thr and D-Thr to L-allo-Thr.[111]

Scheme 6.

Racemase and epimerase activity. A. PLP-dependent catalysis for racemization. B. acid-base catalysis for racemization. C. template-bound catalysis for racemization.

In many NRPS assembly lines, including those for vancomycin and teicoplanin, there are ~50 kDa epimerization domains which act not on free amino acids, but only after an L-amino acid has been activated and tethered as the L-aminoacyl thioester.[112] The C2-H is then kinetically acidic, since the carbanion is stabilized as the thioester enolate (Scheme 6C). Stereorandom return of the hydrogen yields a mix of L- and D-aminoacyl thioester for subsequent chain elongation by downstream D-specific condensation domains.[113,114,115]

5.1.2 Aminomutases Interconvert α- and β-Amino Acids

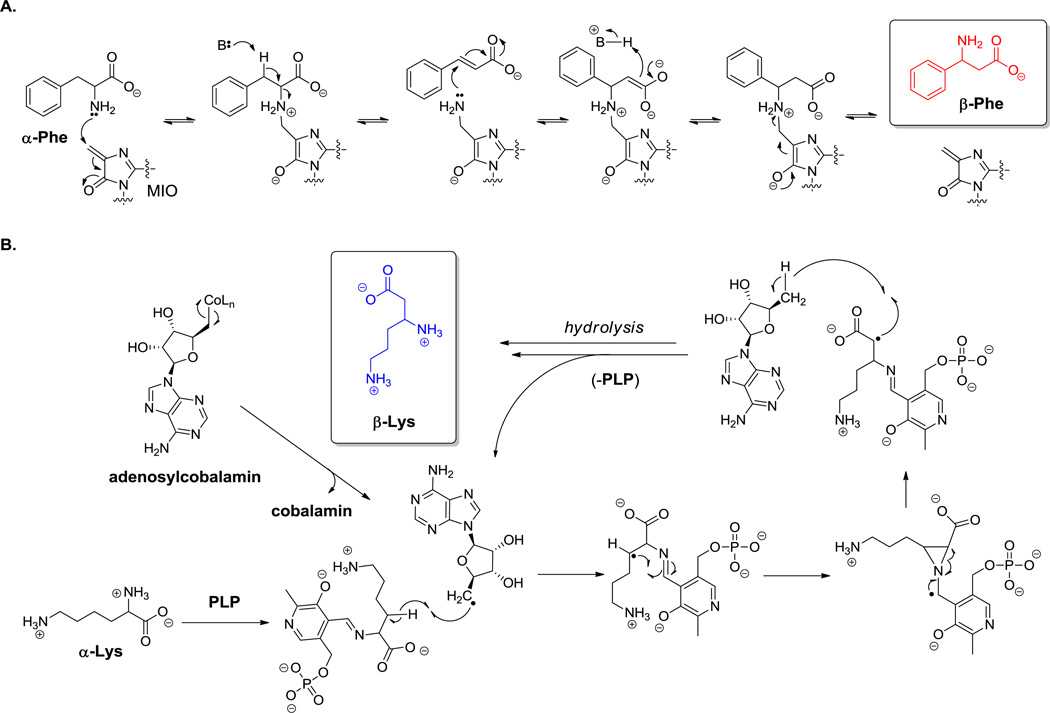

The most general route to β-amino acids is by action of a family of amino acid mutases on the corresponding α-amino acids. Two types of microbial enzymes have been observed to have such mutase activity.[116,117] One involves conversion of Phe or Tyr to the corresponding β-amino acids. In the case of tyrosine, both 3R- and 3S-β-tyrosine are produced by mutases from various sources.[37,38] This subfamily of enzymes contain a covalently attached cofactor 4-methylidene-5-imidazole-5-one (MIO), which arises during automodifying maturation of an Ala-Ser-Gly tripeptide loop in the inactive proenzyme (Scheme 7A). The MIO prosthetic group acts as an electrophilic center for attack by the amino group of bound amino acid substrate. The resulting adduct can undergo Cβ-H bond cleavage to yield a transient noncovalent olefinic species (e.g. cinnamate when starting from Phe) with the itinerant amino group tethered to the MIO moiety. The amino group is transferred back to the cinnamate by attack at Cβ rather than Cα,[118] followed by elimination of β-Phe and restoration of the starting MIO prosthetic group. All this is catalyzed by a single enzyme.

Scheme 7.

Interconversion of α- and β-amino acids. A. MIO-mediated catalysis. B. Radical intermediate catalysis.

The second subfamily of amino acid mutases is found in Clostridium spp, and encompasses lysine- 2,3-aminomutase, glutamate 2,3-aminomutase, and lysine 5,6-aminomutase.[117] This class of enzymes utilizes both pyridoxal-P and adenosyl-B12 as required coenzymes (Scheme 7B). The PLP forms its typical aldimine with the substrates, and the B12 coenzyme mediates radical intermediates in the -H for -NH2 swaps. Also in this enzyme class are D-ornithine 4,5-aminomutase (yielding (2R,4S)-diaminopentanoate) and lysine-5,6-aminomutase, each of which act on the distal rather than the proximal amine of these dibasic amino acids. The last enzyme will also process 3S-β-Lys to 3S,5S-diaminohexanoate. Mutant forms of lysine 2,3-aminomutase can produce β-alanine from Lys as a biotechnological alternative to the aspartate decarboxylase route. The β-Lys in capreomycin and viomycin may arise by this kind of enzymatic action (25 and 26, Figure 11).

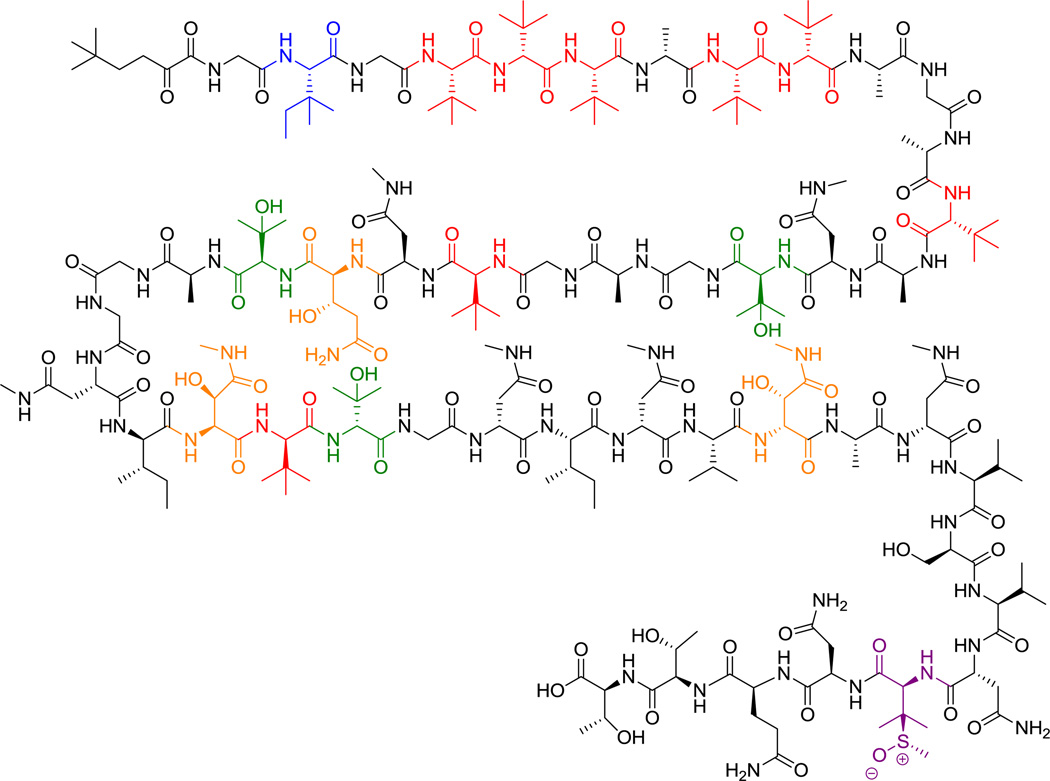

5.2 C-Methyl-O-Methyl-, and N-Methyl Amino Acids

5.2.1 Methylations at Cβ

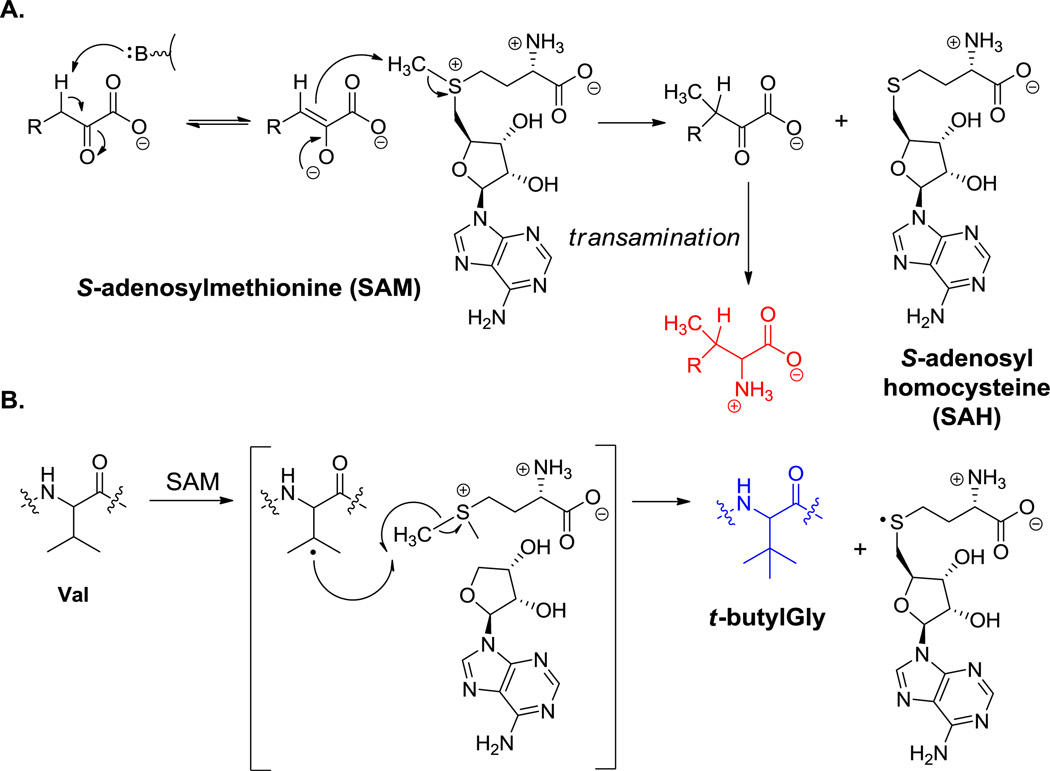

Friulimicin contains a β-methyl-Asp residue (32, Figure 18), daptomycin a β-methyl-Glu (17, Figure 5), and hormaomycin two β-Me-Phe residues (26, Figure 13). In the cases that have been investigated for timing and mechanism to date, Cβ methylations on residues incorporated by NRPS assembly lines occur at the α-keto acid stage.[119] This strategy allows use of the abundant methyl donor SAM to transfer its “CH3+” equivalent to a Cβ carbanion equivalent. Subsequent diastereoselective transamination of the 3-methyl-2-keto acids yields the β-branched amino acids (Scheme 8A). These transformations occur prior to amino acid activation by the corresponding NRPS. Multiple methylations on pyruvate can generate the dimethyl and trimethyl versions of the keto acid and yield either the corresponding amino acid (t-butylglycine) or, via reduction, t-butylglycolate, as found in kutznerides (e.g. 18, Figure 6). In contrast to de novo assembly of the t-butyl moiety on an amino acid building block, such as the t-butylglycines in the ribosomal peptide polytheonamide B and bottromycin A2 (14, Figure 2),[120,121] appear to be introduced by post-translational C-methylation of valine side chains at the β carbon, via radical SAM mediated transfer of CH3• equivalents (Scheme 8B). An analogous C-methylation of an Ile side chain also occurs to give the corresponding branched side chain. Likewise the S-β-methyl-Phe residue in bottromycin is proposed to arise by such radical SAM chemistry. Even more remarkable is a related net sequential addition of four one carbon units to build a -CH2-C(CH3)3 moiety, presumably by the same radical SAM machinery (this provides t-butylglycine, which is found in 14, Figure 2).[61] Some C-methylations of the indole ring of tryptophan involve unreactive carbon sites; those SAM-dependent methyl transfers may also proceed via CH3• radical equivalents, related to polytheonamide B biosynthesis.

Scheme 8.

C-methylation of amino acids at the β-position. A. SAM-mediated C-methylation. B. radical SAM-mediated C-methylation.

Hyperlink 24: Polytheonamide B.

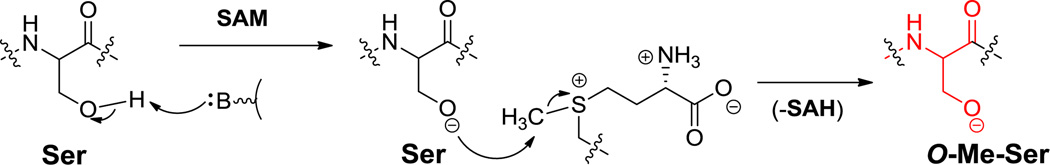

5.2.2 O- and N-Methylations

For O-methylations as in the O-Me-Ser in kutznerides (Figure 6) and the O-Me-Tyr in didemnin B (29, Figure 16), the side chain-OH groups are the proximal nucleophiles to attack the activated methyl group of cosubstrate SAM in a more conventional transfer of a “CH3+” equivalent.[68,90] The timing of O-methylation, in the free amino acid or after incorporation into a peptide framework is not known.

A number of NRPs have one or more peptide bonds that have undergone N-methylation. For example, 7 of the 11 peptide bonds in cyclosporin A (33, Figure 19) and the N-terminus of vancomycin (30, Figure 17) have N-methyl substituents. N-methylation also arises via SAM as cosubstrate and involves direct capture of the itinerant methyl group by the basic amine nitrogen atom acting as a nucleophile.[2] Most of these reactions are catalyzed by methyltransferase (MT) domains that are inserted into A domains in the relevant chain-elongating NRPS modules.[2] Preliminary studies have shown that some N-methylamino acids will function in ribosomal protein biosynthesis in E. coli.[122, 123]

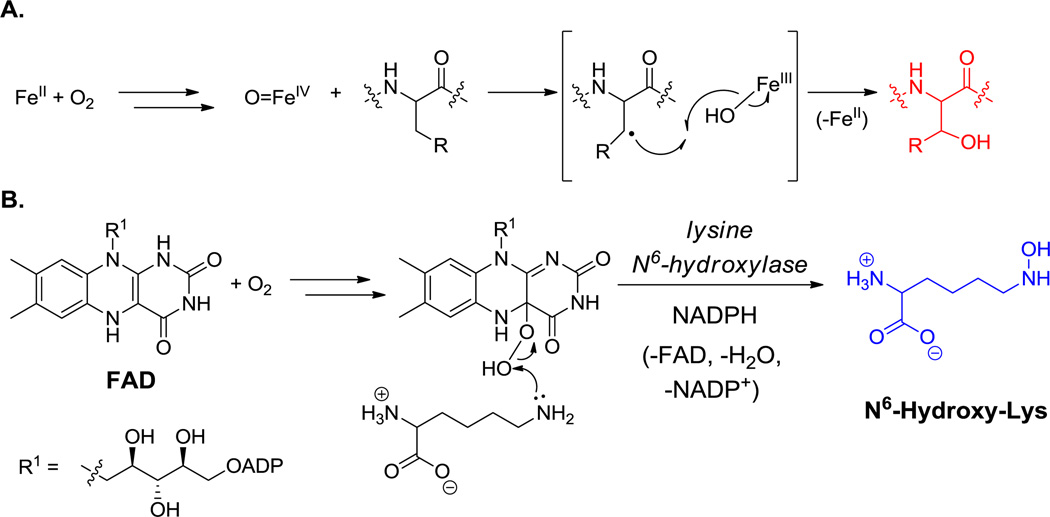

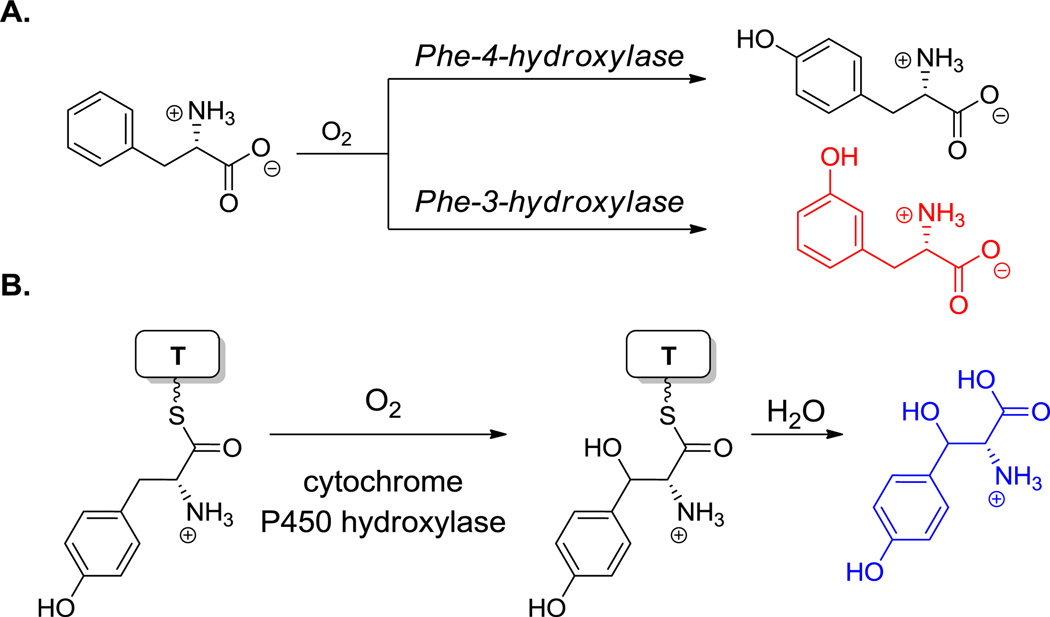

5.3 Side Chain Hydroxylations

In the 15 nonribosomal peptide scaffolds noted in the previous section there are 11 hydroxylated noncanonical amino acid residues. Two of the hydroxyl groups, in the statine residue of miraziridine A (13, Figure 1) and the isostatine residue of didemnin B (29, Figure 16), do not derive from molecular oxygen (O2), but instead stem from the carboxyl of Val and Ile, respectively, as will be discussed in section 6.1 below on hybrid NRPS-PKS modules. All the others arise from O2 by action of hydroxylases that come in two varieties, depending on the cofactor involved. They either harbor an inorganic redox active metal iron center, or they use the organic coenzyme FAD. The former generates a high valent oxoiron intermediate (Scheme 9A), whereas the latter forms a less reactive FAD-OOH as oxygen transfer agent (Scheme 9B).[124] The choice between these two alternative mechanisms is tuned to the reactivity of the amino acid receiving the electrophilic oxygen atom.[125] The six amino acid units in the particular examples (Tyr, Arg, Pro, Glu, Orn, Homo-Tyr) hydroxylated at specific carbon sites all require iron as cofactor, either as heme iron in cytochrome P450 superfamily monooxygenases or as mononuclear nonheme ferrous iron.[126,127] Both forms of these iron-containing oxygenases generate high valent oxoiron species which can cleave unactivated C-H bonds homolytically and deliver back an OH• equivalent.

Scheme 9.

Hydroxylation of amino acids. A. Metal-dependent hydroxylation. B. FAD-dependent hydroxylation.

The proteinogenic building block p-Tyr is normally generated by the nonheme iron-containing phenylalanine hydroxylase, which oxygenates the phenyl ring of Phe regiospecifically. In sanglifehrin biosynthesis (36, Figure 21)[9] and also in the peptidyl nucleoside pacidiamycin antibiotic family,[128] an orthologous Phe hydroxylase acts instead with specificity at the meta position to generate nonproteinogenic meta-tyrosine. Enzymatic hydroxylation at the benzylic (C3) position of Tyr residues yields the β-OH-Tyr that is found in positions 2 and 6 of vancomycin and teicoplanin.[39,40] The three oxidative crosslinkings in the vancomcycin scaffold (and four in teicoplanin) occur by sequential action of three hemeprotein oxygenases encoded in the biosynthetic gene cluster and link β-OH-Tyr2 to 4-OH-Phegly4, 4-OH-Phegly4 to β-OH-Tyr6, and 4-OH-Phegly5 to dihydroxyPhegly7 (see hyperlink in Figure 17).[129] Importantly, whereas β-OH-Tyr is synthesized as a free amino acid, oxidative crosslinking occurs on the NRPS assembly line.

The glutamate-3-hydroxylase in kutzneride maturation (18, Figure 6) is a mononuclear nonheme iron oxygenase,[15] while the oxygenase acting on both C4 and C5 of the Orn side chain in the echinocandin scaffold (25, Figure 12) is a heme-containing oxygenase.[130] It is not yet clear how to predict whether a given iron-based hydroxylase will modify the free amino acid (a feature that would be most useful for their incorporation into proteins) or instead work only on that residue displayed on the deshydroxy peptide scaffold.

Flavin-dependent monooxygenases utilize FL-OOH as the transfer agent for an electrophilic (“OH+”) equivalent.[125] For example, formation of the 2-Cl-N-OH-pyrrole moiety in hormaomycin biosynthesis (26, Figure 13)[51] and hydroxylation of a 3-Cl-β-Tyr monomer to produce 3-Cl-5-OH-β-Tyr in C-1027 biosynthesis require the activity of FAD-containing monooxygenases.[131] Both oxidative reactions occur on aminoacyl substrates tethered to T domains via thioester linkages. Analogously, for N-hydroxylations at basic side chain amino groups (e.g. Orn, Lys in siderophore biosynthesis and at indole NH of Trp-based scaffolds), the nucleophilicity of the nitrogen is sufficiently high that a less robust oxygenation reagent can suffice. Many such amino acid N-oxygenases are flavin-containing enzymes and act on free-standing amino acid substrates.[125] Further oxygenation of N-OH to nitroso and even nitro groups occurs in some NRP biosynthetic pathways, as proposed in formation of the nitrocyclopropyl-alanine residue in hormaomycin (26, Figure 13).[51]

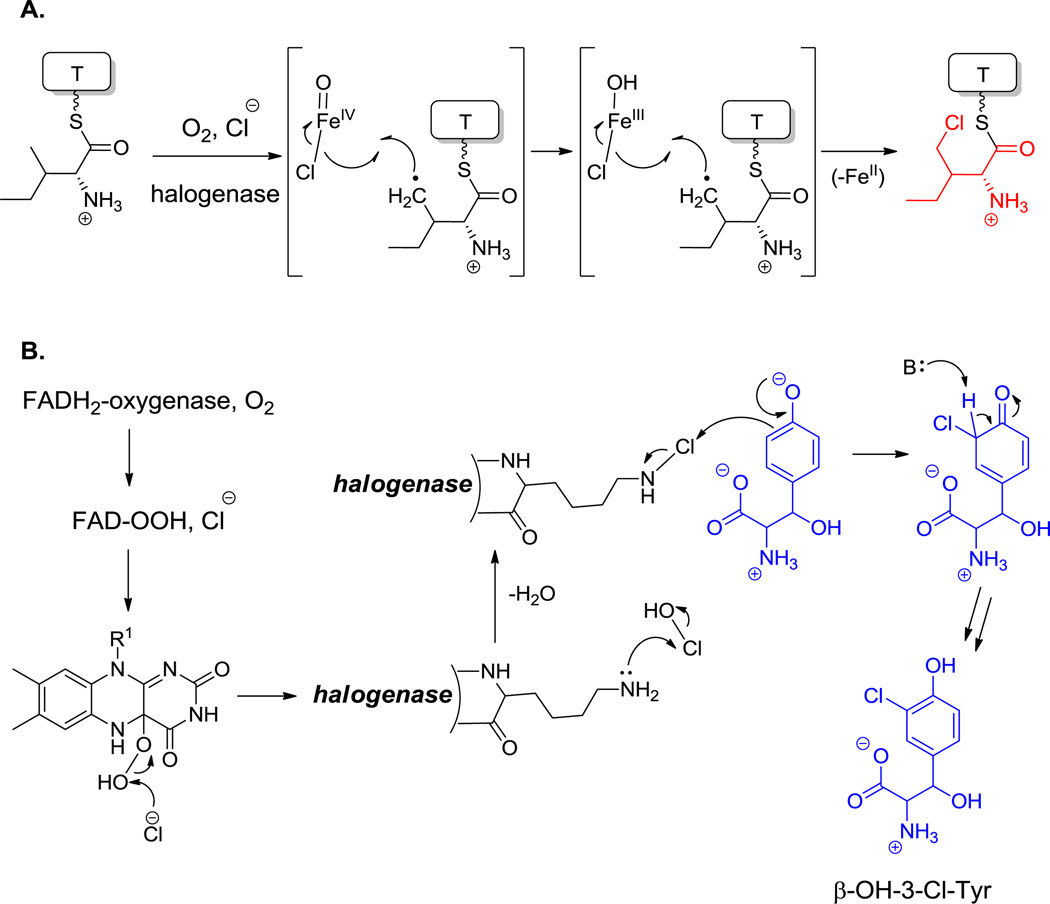

5.4 Chlorination as a Variant of Hydroxylations

Amino acid chlorinases can be viewed as variants of the above oxygenase families.[41] In cases where a formal replacement of C-H by C-Cl occurs at unactivated carbon atoms in amino acid side chains, the responsible catalysts are again mononuclear iron enzymes, consuming one equivalent of O2 and α-ketoglutarate in close analogy to their oxygenase counterparts. Such halogenases for Pro, Leu, and Ile act on aminoacyl-S-T substrates.[132]

In contrast, the electron rich phenol side chain of Tyr and the indole ring of Trp residues again require a weaker chlorinating agent, in analogy to the hydroxylation chemistry cited above that is effected by flavoenzymes. Here too, FADH2-containing halogenases are used, this time to deliver a “Cl+” equivalent.[133] Examples include the 3-Cl-β-OH-Tyr residues of glycopeptide antibiotics (Figure 17),[134] ClmS in chloramphenicol biosynthesis,[135] the 6,7-dichloro pyrroloindole residue in the kutznerides (Figure 6),[136] the biosynthesis of Dicyostelium differentiating factor Dif-1 and in the biosynthesis of the 2-Cl-N-OH-pyrrole carboxy residue of hormaomycin (Figure 13).[51,137] This is also the likely route to 3,5-dichloro-4-OH-Phegly found in enduracidine (35, Figure 20).[48] Intriguingly, the known iron-based halogenases recognize aminoacyl-S-T substrates, while the known flavin-dependent ones act upon free amino acids.

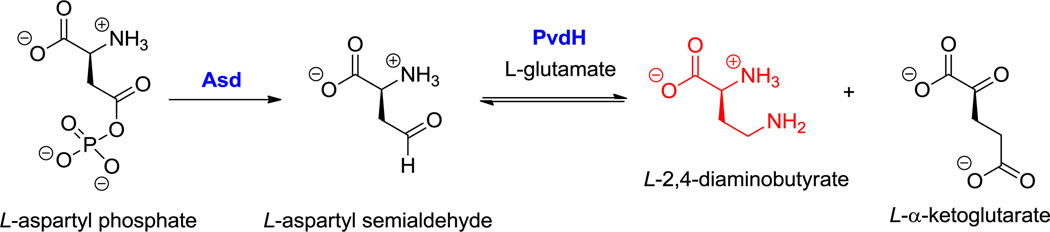

5.5 Diamino Acids

While the six-carbon dibasic (α,ω) amino acid lysine is a proteinogenic building block, the three-, four-, and five-carbon chain dibasic amino acids are nonproteinogenic building blocks. For example, the three carbon 2,3-DAP residue is found in capreomycin (25, Figure 11), five 2,4-DAB residues are incorporated into the cationic polymyxins (15, Figure 3), and the 2,5-diaminopentanoate (a.k.a. ornithine) occurs in echinocandin (25, Figure 12) (where it is doubly hydroxylated) and daptomycin (17, Figure 5) as well as in many siderophores.[138] In addition to the linear 2,4-DAB, the branched 2,3-DAB is also found, as the 2S,3S-diastereomer, in friulimcin (32, Figure 18).[55]

The biosynthesis of ornithine has been well studied, as it is in fact a component of primary amino acid metabolism. 2,3-DAP arises from pyridoxal-P-dependent enzymatic dehydration of serine to a dehydroAla-PLP intermediate which is captured by NH3 (see hyperlink for Figure 11).[44] The branched 2,3-DAB would arise correspondingly from Thr dehydration and regiospecific C3 amination, whereas the 2,4-DAB regioisomer presumably arises from enzymatic transamination of the primary metabolite aspartate semialdehyde (see the hyperlink in Figure 3).[45,46]

5.6 Cyclization of Amino Acid Units

5.6.1 Three Membered Rings

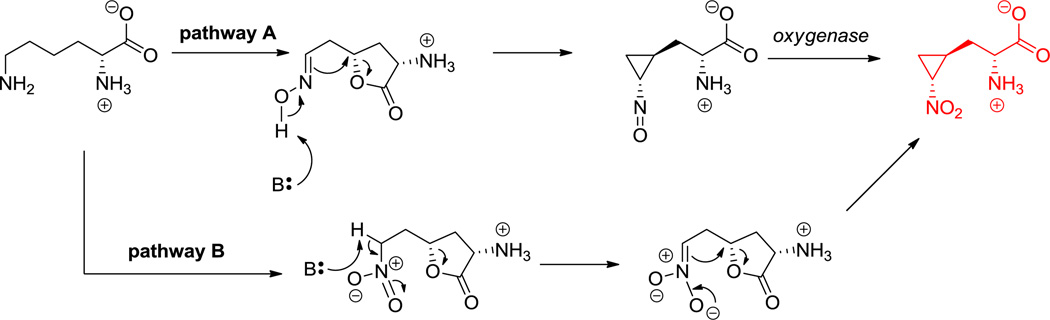

One of the important functional attributes of nonproteinogenic/noncanonical amino acids are the conformational constraints and rigidifications that are imparted into the structural scaffolds where they are incorporated. One such constraint is ring size. In the monocyclic amino acid category, one can observe three membered rings, such as 1-amino-1-carboxy-2-ethyl cyclopropane in the coronamate moiety of coronatine (12, Scheme 5),[105] the aziridine dicarboxylate in miraziridine A (13, Figure 1)[55] and in the nitrocyclopropyl ring embedded in the lysine-derived framework of hormaomycin (26, Figure 13).[51] The cyclopropane in coronamic acid derives from L-allo-Ile (whose direct precursor is unknown, but could be D-Ile). L-allo-Ile is activated and tethered on the S-pantetheinyl arm of a thiolation domain of the CmaA enzyme.[34] There it undergoes regiospecific Cγ-chlorination, prior to intramolecular attack of Cα on that chlorine-substituted Cγ to construct the cyclopropane framework of coronamic acid, still tethered via the thioester linkage. Thioesterase action releases the free coronamic acid,[139] which on subsequent ligation to the bicyclic polyketide coronofacic acid, yields the toxin coronatine (12, Scheme 5) a mimic of jasmonate plant hormones. Processing of Val in place of Ile through this chlorination/cyclization process yields the methyl-substituted cyclopropane known as norcoronamic acid. The cryptic chlorination chemistry is mediated by an O2-requiring iron-containing halogenase as discussed above; instead of transferring an OH•, CmaB transfers a Cl• from the active site high valent iron intermediate.[34]

Less obvious is the enzymatic pathway from Lys to nitrocyclopropyl alanine found in the hormaomycin (26, Figure 13); the C6-amino group of Lys has been oxidized to the nitro group and a cyclopropane has formed by a C-C bond-forming step between C4 and C6. Two possible variations of ring opening of an internal lactone following N6 and C4–oxygenation have been proposed but not yet validated.[51]

5.6.2 Orn and Lys Cyclizations

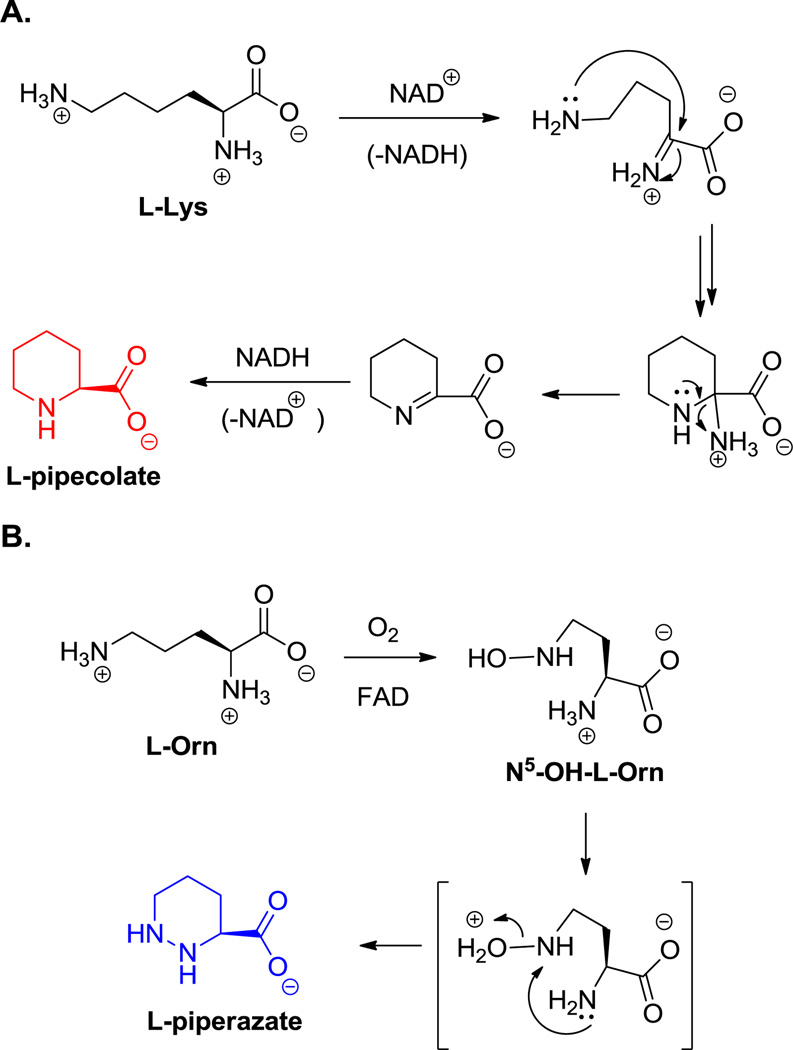

Six ring cyclic amino acids include the proline analog pipecolate, found in rapamycin (3, Scheme 3) and the 1,2-hydrazo analog piperazate, seen in sanglifehrin (36, Figure 21) and the kutznerides (18, Figure 6). Pipecolate is synthesized by lysine cyclodeaminase;[140] this enzyme class has tightly bound NAD and begins catalysis by oxidation of the α-amine to the imine, yielding NADH as a transient coproduct still bound to the enzyme. Intramolecular attack by the C6-NH2 generates a cyclic imine after elimination of NH3. That Δ1-piperidine carboxylate is finally reduced by hydride transfer from the bound NADH, regenerating the starting oxidation state of the bound coenzyme (NAD) and releasing pipecolate (Scheme 10A).

Scheme 10.

Pipecolate and piperazate biosynthesis. A. Proposed mechanism of pipecolate formation. B. Proposed mechanism of piperazate formation.

The piperazate ring found in kutznerides and sanglifehrin is also a cyclic six-atom framework but has two nitrogens in a hydrazo (N1-N2) linkage. It derives from ornithine and the first step is N5-hydroxylation by a dedicated flavoprotein.[141] It has been proposed that further oxygenation occurs to the nitroso-Orn to set up intramolecular attack of the α-NH2 as nucleophile on such an electrophilic Nδ to form the unusual N-N bond (Scheme 10B).

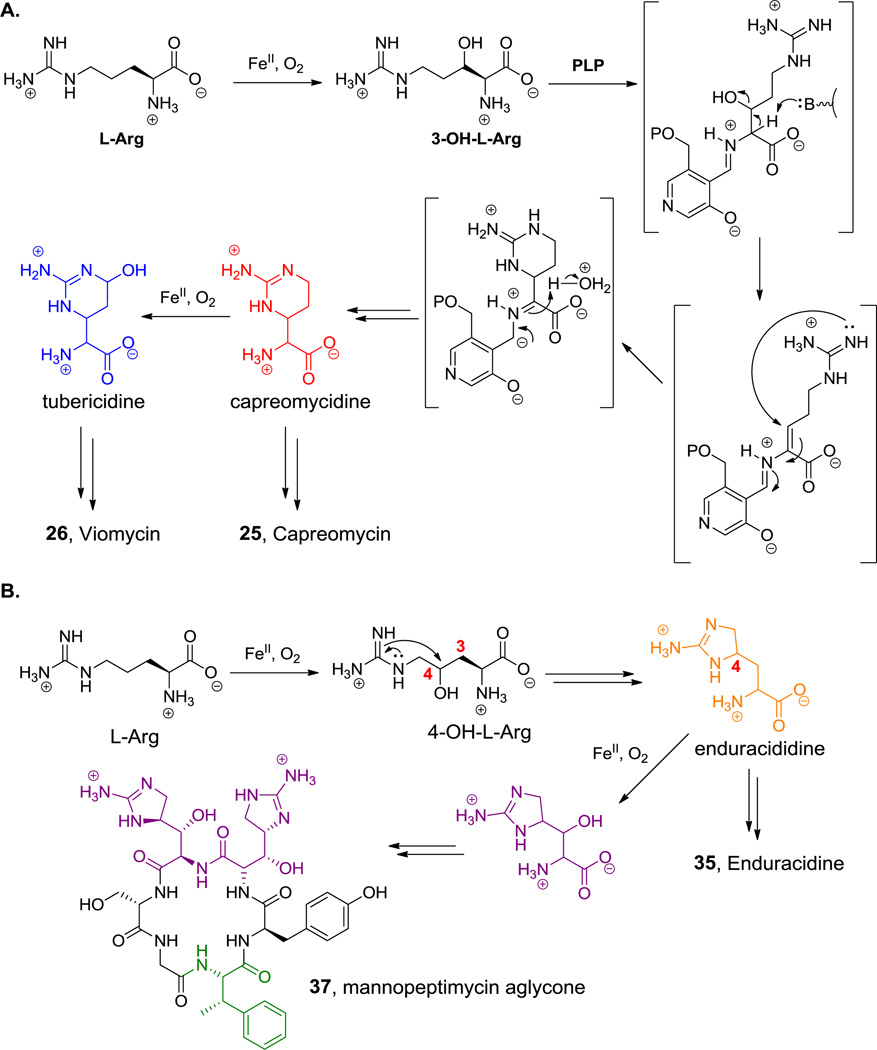

5.6.3 Cyclization of the Guanidino Moiety of Arg

Five- and six-membered, Arg-derived cyclic guanidines are observed in enduracidine (35, Figure 20) and capreomycin (25, Figure 11), respectively. The six member capreomycidine ring is proposed to arise following hydroxylase action to create a 3-OH-Arg.[142,143] Subsequent processing by a pyridoxal-P dependent enzyme presumably leads to water elimination and the formation of an eneamino-PLP adduct. Intramolecular capture by the terminal guanidino nitrogen and release from the PLP-enzyme active site yields the cyclic six-membered ring (Scheme 11A). In viomycin (26, Figure 11) the same ring system has undergone an additional hydroxylation to generate a tuberacidine residue. The route to the five membered cyclic guanidine in enduracidine is not as well worked out (the route shown in Scheme 11B is hypothetical), although a similar ring system in guadinomine is formed via intramolecular attack of the guanidine group terminal nitrogen on a C3–C4 unsaturated intermediate.[144] In mannopeptimycins (e.g. 37, Scheme 11B), a subsequent C3 hydroxylation yields β-OH enduracididine.[145]

Scheme 11.

Biosynthesis of cyclic guanidines. A. Biosynthesis of six-membered cyclic guanidines. B. Biosynthesis of five-membered cyclic guanidines. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = capreomycidine, blue = tubericidine, green = (2S,3S)-β-methyl-Phe, purple = β-hydroxyenduracididine, orange = enduracididine.

5.6.4 Pyrroloindole tricycle formation

Tryptophan residues can be converted to tricyclic pyrroloindole cores by addition of two types of electrophiles across the 2,3-double bond of the pyrrole ring. In generation of the Bacillus competence factor peptides, a geranyl group is added to C3 while the downstream amide NH attacks C2.[146] Alternatively, delivery of electrophilic oxygen “OH+” by oxygenases (to generate a transient indole epoxide/hydroxyiminium species) can induce capture by the intramolecular amide to build a pyrroloindole, as in kutzneride biosynthesis (Figure 6).[147] These modifications must occur either on the elongating linear chain or after the macocyclic peptide scaffold has formed, and are not possible on free Trp. A comparable indole epoxygenation is observed during fungal biosynthesis of fumiquinazoline A.[148]

5.7 Kynurenine and Alkyl/Alkenyl Proline Biosynthesis

In daptomycin (17, Figure 5), the indole ring of tryptophan is oxidatively cleaved by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase action to yield N-formylkynurenine. Enzymatic deformylation yields free kynurenine which is selected, activated, and incorporated by the adenylation domain of NRPS module 13 to become the terminal residue in daptomycin.

Analogous oxidative cleavage of the aromatic ring of tyrosine occurs in the formation of the propenyl proline monomer of hormaomycin (26, Figure 13) as well as in anthramycin, suburomycin, and tomayomycin biosynthesis.[149] The pathway starts by conventional ortho-hydroxylation of Tyr to L-DOPA and subsequent oxidation of the diphenol to the orthoquinone.[150] Intramolecular attack by the amine on the quinone yields a dihydroxyindole carboxylate that is substrate for oxygenative cleavage of the ring by an intradiol-type dioxygenase, yielding a diene-diacid-substituted proline. Removal of the C2 enoyl acid moiety must occur as well as addition of a C1 fragment, probably by radical SAM enzymology, to construct the C3-substituted propenyl group.[51] The propenyl Pro is presumed to be a free amino acid building block for the hormaomycin NRPS assembly line, with a total of six enzymes required to morph Tyr into propenyl proline.[51]

5.8 Hydroxylated Phenylglycines

The 4-OH-Phegly monomer of vancomycin (30, Figure 17), teicoplanin (31, Figure 17) and enduracidine (35, Figure 20) is synthesized by four enzymes.[42] The first enzyme, a homolog of prephenate decarboxylase, utilizes the primary metabolite prephenate to produce p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate. A second decarboxylase oxygenates this intermediate to form p-hydroxymandelate. Oxidation of the hydroxy group to the ketone yields p-hydroxybenzoylformate; the last enzyme transaminates this keto acid to L-p-OH-Phegly. Phenylglycine in pristinamycin (Scheme 4) is also derived from an analogous pathway.[43]

By contrast, 3,5-dihydroxyphenylycine building block in glycopeptides is assembled via a distinct four enzyme pathway (Figure 17). The pathway commences with a type III PKS that uses 4 molecules of malonyl CoA and via iterative decarboxylative Claisen reaction to build the eight carbon framework of 3,5-dihydroxyphenylacetyl CoA.[151,152] The next enzyme performs a remarkable chain-shortening oxidation, dependent on O2, to generate the 3,5-dihydroxybenzoylformate. The last enzyme is a transaminase to produce the 2S (L-) form of 3,5-(OH)2-Phegly.

6 Amino Acids Synthesized by Enzymatic Assembly lines

A variety of nonproteinogenic amino acids, or peptides containing them, have been isolated in which the amino group is at C4 rather than at C2. In many of these cases it appears a two-carbon extender, derived from a CH2-COOH equivalent has been inserted into a proteinogenic amino acid scaffold and now comprises C2 and C1, respectively. C3 in these scaffolds is often an OH or an O-CH3 group, as seen in the amino acids statine in miraziridine A (13, Figure 1) and isostatine in didemnin B (29, Figure 16). This is also the case for dolaisoleucine in dolastatin 10.[153] The statine residue with its tetrahedral C3-OH has been a useful inhibitory mimic of tetrahedral intermediates in the action of several aspartyl proteases.[154] Correspondingly miraziridine has a vinyl-Arg residue at its C terminus (Figure 1) and syringolin A has a vinyl-Val (20, Figure 8).

These residues are also extended by an acetate-derived two-carbon unit, but now C2 is an sp2 rather than an sp3 carbon.

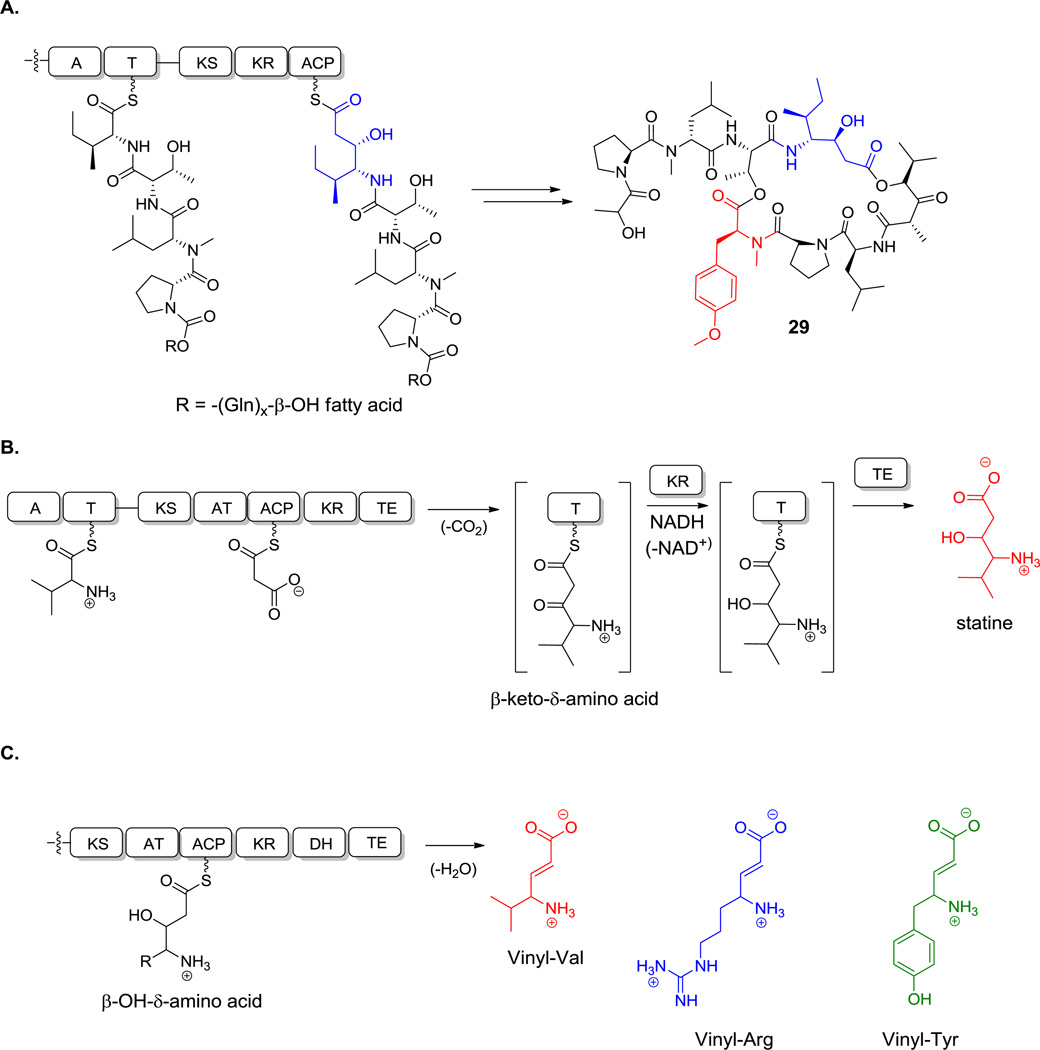

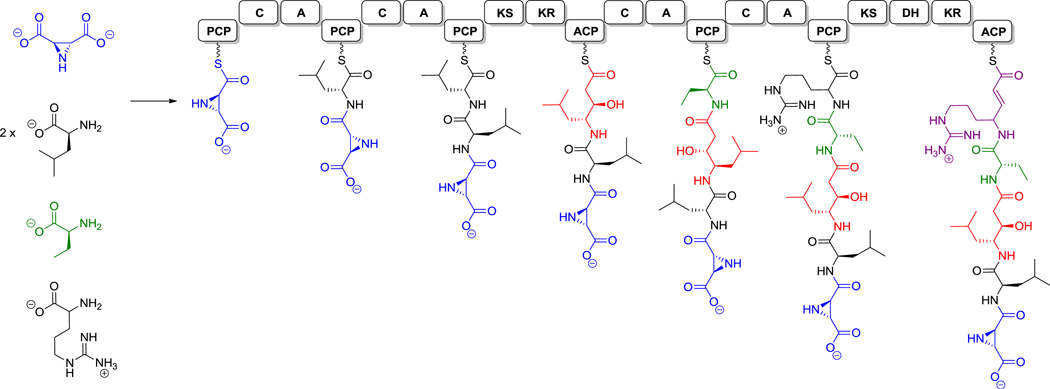

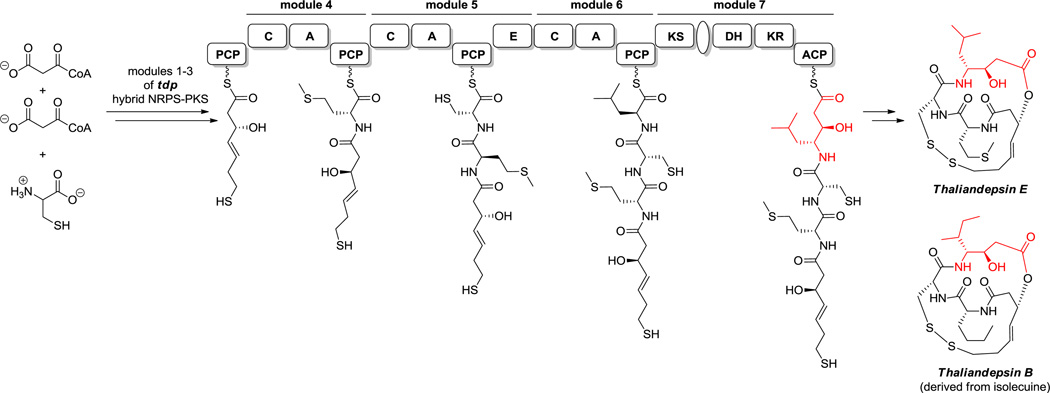

6.1 NRPS-PKS Hybrids

These amino acid connectivity observations could be fully rationalized when biosynthetic gene clusters became available for natural products containing such 3-OH-4-NH2 acid frameworks, such as didemnin B (29, Figure 16) and andrimid.[155,107,156] The didemnin cluster encodes a PKS module interspersed between NRPS modules. In that case the growing N-acyl-Pro-D-MeLeu-Thr-Ile-S-tetrapeptide is tethered as a thioester to the S-pantetheinyl arm of the peptidyl carrier protein domain of the fourth NRPS module. Immediately downstream is a PKS module, which tethers a malonyl unit also in S-pantetheinyl linkage, on its own acyl carrier protein. Decarboxylation of the malonyl moiety generates the C2 carbanion for capture of the upstream peptidyl thioester. The C-C bond-forming step moves the peptidyl moiety onto the two-carbon unit and sets the peptidyl amino carbon as C3.The PKS module has a ketoreductase domain so the β-keto group is then reduced to the β-OH, yielding the isostatyl residue as a ketide-extended N-acyl-pentapeptidyl thioester. This intermediate is then subjected to further chain elongation by the downstream NRPS modules, with macrocyclizing release, embedding the isostatyl residue within the macrocyclic framework. The mechanism of an isostatyl biosynthesis is shown in Scheme 12A.

Scheme 12.

Hybrid NRPS-PKS assembly lines. A. Isostatine assembly into didemnin B. Mechanism of statine biosynthesis. C. Vinylogous amino acid biosynthesis. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: (A) red = O-Me-Tyr, blue = isostatine; (B) red = statine; (C): red = vinyl-Val, blue = vinyl-Arg, green = vinyl-Tyr.

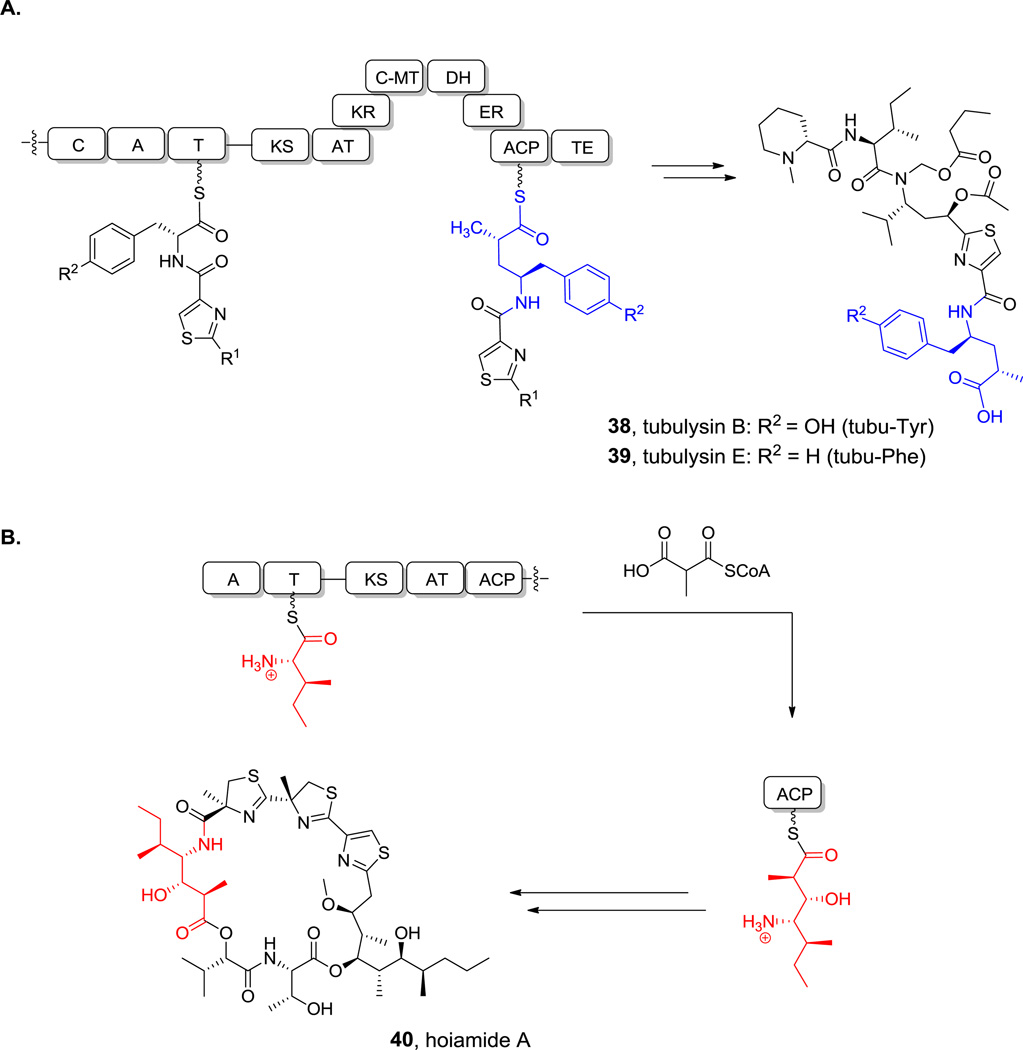

Analogously, if Leu is activated by such an NRPS-PKS hybrid, the resulting chain-extended hybrid building block would be a statyl residue (Scheme 12B) as in miraziridine. In the andrimid biosynthetic pathway, the comparable NRPS-PKS pair lacks a reductase domain within the PKS module, so the β-ketone functionality is retained.[156] If the chain-elongated intermediate in the statine pathway with its β-OH group were further subjected to typical α,β-dehydration by a dehydratase domain, the resulting product would be vinyl-Leu (Scheme 12C). The comparable vinyl-Val residue is known (Figure 8). Alternatively, starting from Arg, comparable logic in an NRPS-PKS bimodule would generate vinyl-Arg for the miraziridine assembly line (Figure 1).[54] Similarly, a vinyl-Tyr can be found in cyclotheonamide.[157] Finally, if the PKS module has an enoyl reductase (ER) domain, the vinyl group would undergo hydrogenation, resulting in an amino acid extended by a CH2COOH group. Such extended Tyr and Phe residues are found in the tubulin inhibitors tubulysins B (39) and E (40, Scheme 13A), where they are known as tubu-tyrosine and tubu-phenylalanine.[158]

Scheme 13.

Hoiamide and tubulysin biosynthesis. A. Tubu-tyrosine and tubu-phenylalanine biosynthesis. B. Mechanism of 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2,5-dimethylheptanoate biosynthesis Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2,5-dimethylheptanoate, blue = tubu-Tyr or tubu-Phe.

Many PKS assembly lines use methylmalonyl-CoA instead of malonyl-CoA as chain extender units. Indeed the hoiamides (e.g. hoiamide A (41), Scheme 13B) harbor a 4-amino-3-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl heptanoate residue that results from an Ile -and methylmalonyl-utilizing NRPS/PKS hybrid module.[159] Of course one can have more than one PKS-mediated chain extension cycle to build longer alkyl chains. For example, the 3-amino-2,5,7,8-tetrahydroxy-10-methylundecanoate in cyanobacterial pahayokolides may arise from leucine and three malonyl-CoA extender units with additional adjustments of redox states.[160] Here, the β-amino acid would be generated by reductive amination of the β-keto acid produced by the PKS machinery.

It should be noted that the opposite arrangement of modules (i.e. PKS-NRPS) also exists in nature’s repertoire of hybrid assembly lines, as in the case of rapamycin (3, Scheme 3). However, these configurations typically do not yield an amino acid product; instead, they catalyze amide bond formation.

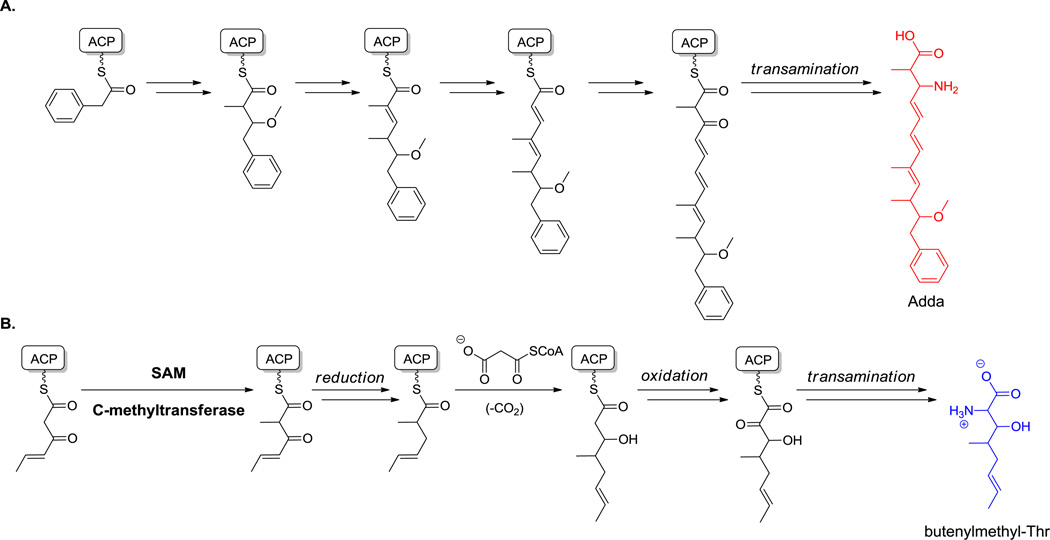

6.2. Amino Acids Synthesized by PKSs Followed by Reductive Amination

The nonproteinogenic amino acids Aeo in the cyclic tetrapeptide HDAC inhibitors trapoxin and HC toxin (23 and 24, Figure 10), Adda (3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl-4,6-decadienoate) in microcystin LR (28, Figure 15),[79,161] and butenylmethylthreonine in cyclosporin A (33, Figure 19)[100] are clearly reminiscent of PKS assembly line origins. For Adda in particular, a benzoyl CoA starter unit gets extended by three methylmalonyl CoA and 2 malonyl CoA extender units, yielding a β-keto acid that undergoes transamination (Scheme 14A).[79,162] A similar route and PKS machinery may be involved in the formation of the Atmu (3-amino-2,5,7,8- tetrahydroxy-10-methyl-undecanoate) unit in pahayokolides,[160160] this time with additional hydroxylation events at C2 and C6. The long chain (C15–17) β-amino acid starter units in mycosubtilin (27, Figure 14) and iturin are also derived by a similar mechanism. In this instance a β-keto acyl-CoA, from fatty acid biosynthesis, undergoes transthiolation on the NRPS heptapeptide assembly lines and then undergoes enzymatic transamination in situ as preamble to building the acylated peptide chain.[86b] That N-terminal β-amino fatty acyl group is subsequently the nucleophile in the last step of mycosubtilin assembly to create the heptapeptidyl macrolactam scaffold. Note that this route to β-amino acids is distinct from the action of amino acid mutases on β-amino acids, such as the conversion of α-Phe to β-Phe carried out by MIO-containing mutases noted in section 5.1.2.

Scheme 14.

Biosynthesis of polyketide precursors to amino acids. A. Biosynthesis of 3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl-4,6-decadienoate (Adda). B. Biosynthesis of butenylmethyl-Thr.

The butenylmethylthreonine residue (2S,3R,4R,6E-2-amino3-hydroxy-4-methyl-6-octenoate) in the immunosuppressant undecapeptide cyclosporin A (33, Figure 19) is an α-rather than a β-amino acid but similarly has a PKS origin (Scheme 14B).[163] The nine carbon thioester is assumed to undergo oxygenation and oxidation of the CH2 at Cα, followed by hydrolysis and transamination to give the α amino acid. An analogous route is envisioned for the 2-amino-8-keto-9,10-epoxy-decanoate (Aeo) residue in the HC-toxin and trapoxin family of cyclic tetrapeptide antagonists of histone deacetylases (Figure 10).[79] The epoxide is thought to arise from a Δ9 olefin. The saturated 2-amino-8-ketodecanoate residue homologous to Aeo is found in apicidin,[164] and the 9-OH analog in another member of the cyclic tetrapeptide fungal metabolite family, consistent with differential tailoring of the polyketide precursors.[165]

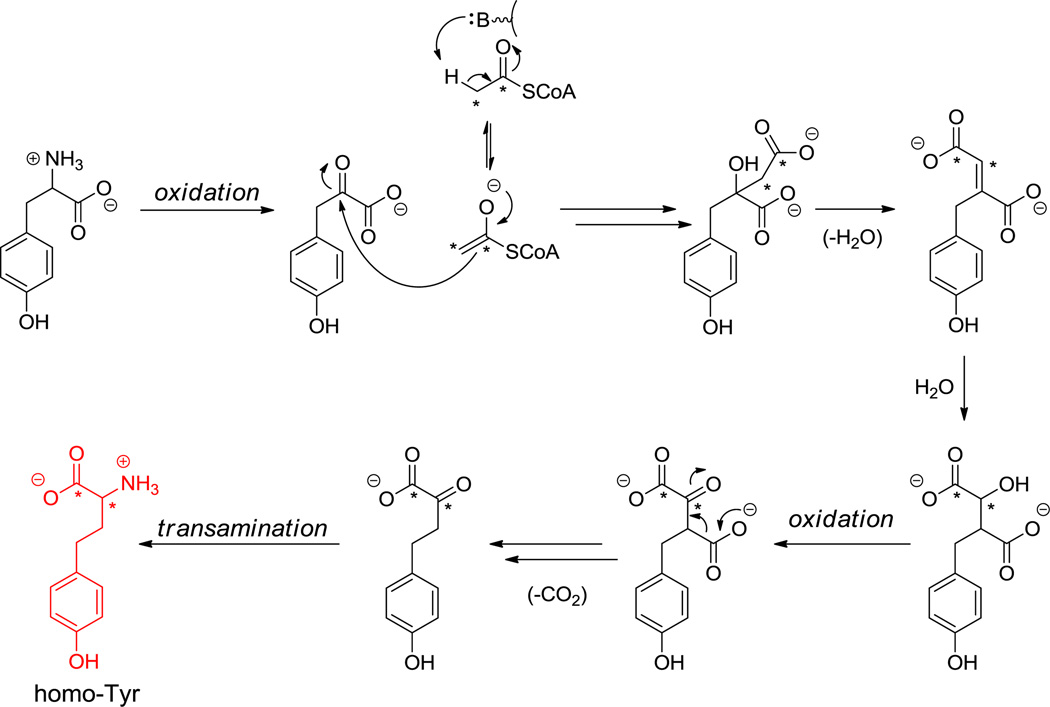

7. HomoTyr and Other Homologated Amino Acids

HomoPhe and homoTyr, where an additional methylene has been inserted into the chain, arise from the scaffolds of Phe and Tyr, respectively. Homotyr residues are found in some cyanopeptolins and 3,4-dihydroxy-homoTyr is found in echinocandins.[85,166] Early labeling studies had shown that the dihydroxy homoTyr in echinocandins (e.g. 25, Figure 12) arises from Tyr and the two carbons of acetate. It is presumed that the carboxylate moiety of the Tyr precursor is lost (two carbons added, one carbon lost). Precedent for such net CH2 homologation occurs during leucine biosynthesis.[167] By analogy, for homoTyr, the C2 carbanion of acetyl CoA could add into the ketone of p-OH-phenylpyruvate (arising from Tyr transamination) to yield a β-OH adduct, which can isomerize to the α-OH, β-COOH adduct via reversible dehydration and rehydration in the opposite regiochemical sense (Scheme 15). Oxidation of the hydroxyl to the ketone and resultant facile decarboxylation of the β-carboxylate yields the homologated α-keto acid. Transamination then gives homoTyr. Dihydroxylation at C3 and C4 to complete the framework found in echinocandins is presumed to occur via iron-based oxygenase action. An analogous pathway from Phe and acetyl CoA would lead to homoPhe, found in some nonribosomal peptides including in pahayokolides as the D-isomer.[160]

Scheme 15.

Biosynthesis of homo-Tyr.

In norvaline biosynthesis, α-ketobutyrate can substitute for p-OH-phenylpyruvate in the initial condensation with the acetyl CoA carbanion. If instead α-keto-β-methyl valerate (derived from transamination of Ile) is the keto acid condensing partner with acetyl-CoA for isopropylmalate synthase, homoisoleucine will arise at the final transamination step. The simplest homologated nonproteinogenic amino acid is 2-aminobutyrate, (homologated alanine), available from transamination of the same α-ketobutyrate.

8. Amino Acids with Potentially Reactive Functional Groups

Proteinogenic amino acids do not contain any reactive or potentially reactive electrophilic side chain functionalities such as olefins, aldehydes or ketones, ruling out unwanted side reactions of these groups once installed in proteins. On the other hand natural nonproteinogenic amino acids do contain some potentially reactive functional groups such as olefins (and very rarely alkynes), epoxides (and very rarely aziridines), and, exceedingly rarely, the β-lactam acylation warheads.[168]

8.1 Olefins and Alkynes

α,β-Olefinic amino acids are enamines and will not be stable, due to spontaneous isomerization to the imines, followed by hydrolysis to ammonia and the keto acid. One can observe posttranslational dehydration of Ser and Thr residues in small proteins to yield the α,β-unsaturated amides (dehydroAla and also dehydrobutyrine and also in pahayokolide).[160,169] While these are kinetically stable they are electrophilic at Cβ due to conjugation to the amide and undergo capture by nucleophiles: this is the basis for lanthionine and methylanthionine residue formation, notable in the lantipeptides. In capreomycin the dehydroalanine moiety is further modified with a ureido group (25, Figure 11).

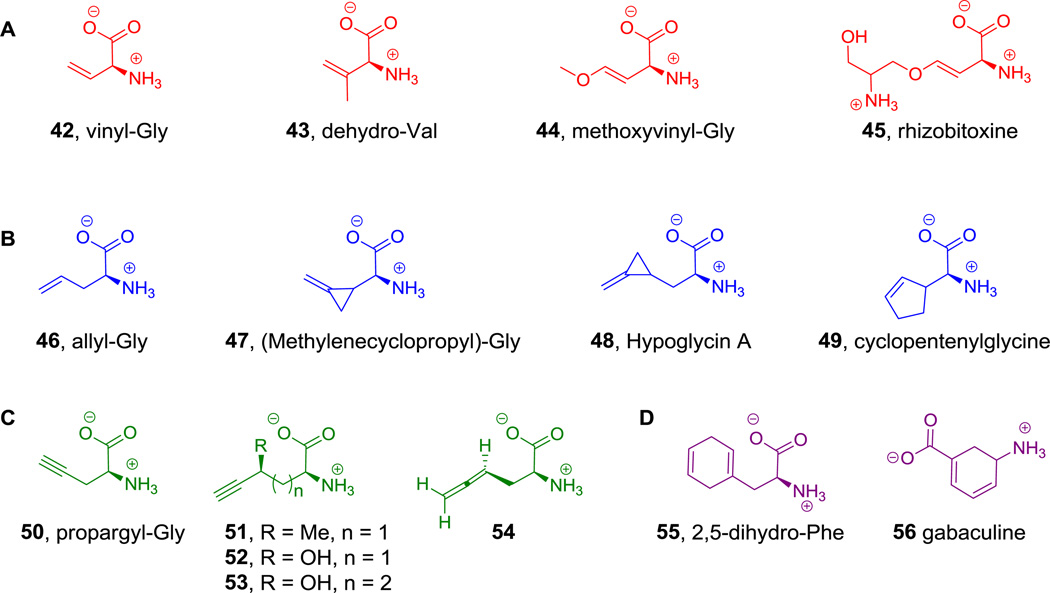

In contrast, β,γ-olefinic amino acids are stable.[170] The parent in this category, vinyl-Gly (42, Figure 22A) is a known natural metabolite,[171] although its biosynthesis is not fully clear: a byproduct of PLP-containing γ-elimination enzymes would be one route. A related β,γ-olefinic amino acid is dehydro-Val (43, Figure 22A), which occurs in the hexapeptide mycotoxin phomopsin A.[172] The β-alkoxy substituted vinylglycines, including methoxyvinylglycine (44) and rhizobitoxine (45, Figure 22A), are less reactive than vinyl-Gly as free metabolites.[173,174] Once they undergo elimination of the -OR group in the active site of PLP-enzymes they are subject to capture by other nucleophiles including oxygen and sulfur side chains of amino acids in the enzyme. Notably, these amino acids are synthesized as free metabolites (i.e., not tethered to T domains of NRPS modules).

Figure 22.

Alkyne and alkene containing amino acids. A. red = β,γ-olefins, B. blue = γ,δ and δ,ε-olefins. C. green = alkynes and an allene. D. purple = dienes.

The simplest γ,δ-olefinic amino acid allylglycine (46, Figure 22B) is also a known metabolite, in mushrooms, but its biosynthetic pathway has not been delineated.[175,176] It is a stable molecule but the olefin can be isomerized into conjugation and become electrophilic by the subset of PLP-enzymes that carry out γ-elimination and replacement reactions.[177] Several other olefinic amino acids have also been isolated from a variety of plants, including β,γ-unsaturated (methylenecyclopropyl)-Gly (47) which occurs in the seeds of Litchi chinensis;[178] δ,ε-unsaturated amino acid Hypoglycin A (48), which occurs in the seeds of Blighia sapida (ackee) fruit and is known to cause Jamaican vomiting sickness if ingested;[179] and cyclopentenyl-Gly, which is known to inhibit isoleucine utilization in E. coli (49, Figure 22B).[180] The alkyne congener of vinyl-Gly, L-propargylglycine (50, Figure 22C) has the same stability and latent reactivity with the same set of PLP enzymes.[181], Several other naturally occurring alkyne containing amino acids are known, such as 2-amino-4-methyl-5-hexynoic acid (51), 2-amino-4-hydroxy-5-hexynoic acid (52), and 2-amino-4-hydroxy-6-heptynoic acid (53, Figure 22C), all isolated from the seeds of Euphoria longan.[182] Additionally, an allene containing amino acid (2-amino-4,5-hexadienoic acid (54), Figure 22C) was isolated from the mushroom Amanita solitaria.[183]

2,5-Dihydrophenylalanine (55, Figure 22D) is another γ,δ-olefinic amino acid that can act a bacterial antimetabolite interfering with Phe metabolism.[184] Another amino acid of particular interest in the natural dienoic dihydro amino acid category is gabaculine (56, Figure 22D).[185] Its biosynthesis is not yet resolved but its mechanism of action with certain PLP-dependent enzymes has been studied.[186] Formation of the gabaculine=PLP aldimine, followed by Cα-H abstraction generates an intermediate that can aromatize and in so doing capture the PLP coenzyme as a nonhydrolyzable amine adduct.[185]

8.2 Epoxides

While prevalent in certain terpene and polyketide classes, epoxides are relatively rare in amino acid-derived natural products.[168] One amino acid noted above is the 2-amino-8-keto-9,10-epoxydecanoate, Aeo, responsible for the covalent modification of histone deacetylases when embedded in the HC-toxin/trapoxin class of cyclic tetrapeptides (Figure 10).[79] Almost assuredly the epoxide arises from the T-domain bound 9,10-olefin precursor by action of an iron-based monooxygenase, as recently proven for dapdiamide C.[187] When bound to active sites of their target enzymes, such epoxides require an acid catalyst to transfer a proton to the oxygen, to lower the transition state energy for C-O bond cleavage as some nucleophile attacks the carbon.

8.3 Aldehydes and Ketones

Aldehyde and ketone functional groups are absent in proteins, as pointed out by Schultz and colleagues in their successful efforts to expand the genetic code and incorporate ketone-containing unnatural amino acids into engineered proteins to increase functional group capacity.[33]

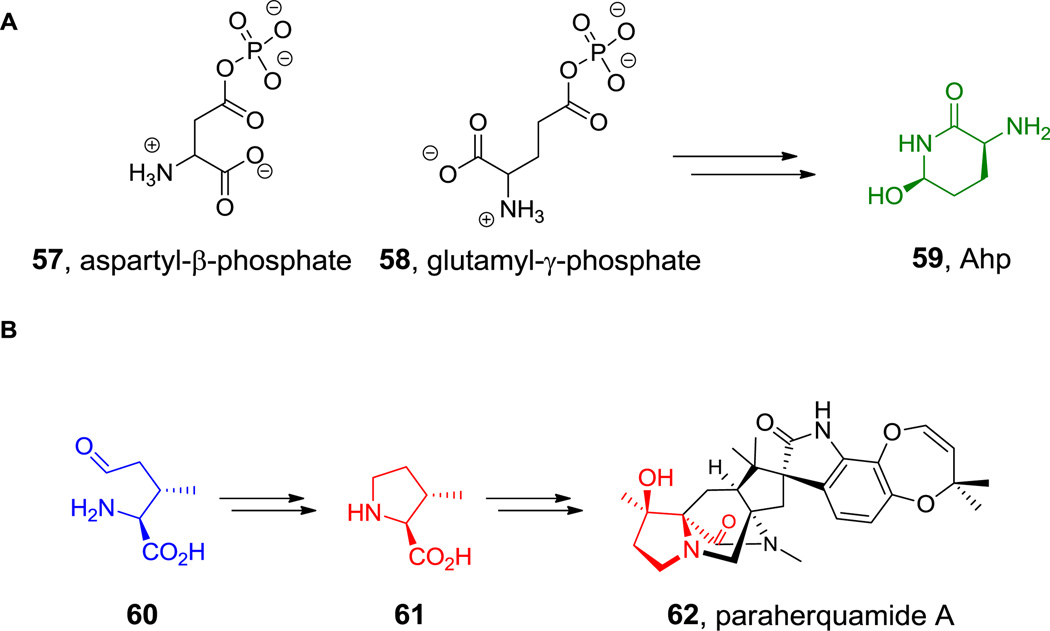

However, aldehydic amino acids are central intermediates in the metabolism of the amino acids aspartate and glutamate. Each of the side chain carboxylates can be phosphorylated enzymatically to yield aspartyl-β-phosphate (57) and glutamyl-γ-phosphates (58, Figure 23A), respectively. These are then enzymatically reduced by hydride transfer from dihydronicotinamide cofactors.ref The Asp aldehyde is a key intermediate in microbial and fungal biosynthesis of lysine, methionine isoleucine, and threonine.[167] The glutamyl-γ-semialdehyde is a corresponding intermediate by transamination to ornithine or by intramolecular imine formation and NADH-mediated reduction to proline. A cyclized form of the glutamyl semialdehyde is found in some nonribosomal peptides where it has been termed an Ahp residue (3-amino-6-hydroxypiperidone (59), Figure 23A).[188] The nitrogen of the immediately downstream amide in the peptide backbone acts as a nucleophile to form the cyclic hemiaminal linkage, a conformationally restricting cyclization event. Examples of such natural products include stigonemapeptin,[188] symplocamide,[189] and cyanopeptolins.[190]

Figure 23.

Amino acids accessed through aldehyde intermediates. A. glutamyl and aspartyl phosphates. B. Paraherquamide A biosynthesis. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: blue = 5-oxo-Ile, red = β-Me-Pro, green= Ahp.

In contrast to the reduction of acid groups to aldehydes for Asp and Glu, the terminal δ-CH3 of Ile is oxidized to the corresponding aldehyde (5-oxo-Ile, 60), presumably through the alcohol intermediate, both in the free amino acid on the way to form β-methylPro (61) which is incorporated into paraherquamide A (62, Figure 23B).[191]A similar residue is also embedded in the peptide macrocycle of GE37468 to yield the β-methyl-δ-OH proline residue in that scaffold.[192] Cysteine residues in some proteins, such as sulfatases, can be oxidized posttranslationally to the side chain aldehyde, yielding formylglycine (63, Figure 24) residues which participate as electrophiles in sulfate ester substrate hydrolysis.[118] These unique formylglycine residues can be captured by external nucleophiles to engineer site-specifically modified proteins.

Ketones are more thermodynamically stable carbonyl groups than aldehydes. A few cases of ketone-containing nonproteinogenic amino acids are known. The most prominent is 2-amino-3- ketobutyrate (64, Figure 24), arising from enzymatic oxidation of the side chain alcohol of L-threonine.[193] This four carbon α-amino-β-keto acid is subject to retro aldol cleavage in the presence of CoASH as cosubstrate to yield acetyl CoA from C3,4 and glycine from C1,2. Retro aldol fragmentation would be a continuing but presumably muted liability if 2-amino-3-keto amino acids were incorporated into protein backbones.

6-Diazo-5-oxonorleucine (DON (65), Figure 24) provides a diazomethyl ketone in its compact scaffold.[194] Its biosynthesis has not been reported even though it was isolated 60 years ago. A related α-diazoester, azaserine (66, Figure 23), is also naturally occurring and has antitumor and antibiotic properties.[194,195] The diazoketone group is set up for loss of dinitrogen (N2) on attack by nucleophiles, so an engineered tRNA/tRNA synthetase pair for DON might be of use for selective reactivity.

The cyclic amino acid acivicin (67, Figure 24) is another example of a heterocyclic electrophile that mimics glutamine residues.[196] Its biosynthesis remains unknown.

8.4. α,β-Unsaturated Amides, Epoxyamides, and Epoxyketones

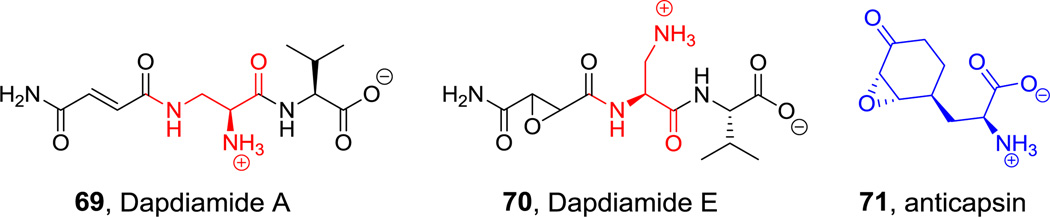

When olefins are α,β- to carbonyl groups they become activated as electrophiles for conjugate addition. We noted the vinyl-Val residue in syringolin (20, Figure 8) as the reactive site for covalent modification of the proteasome.[197] Another example is in the dapdiamide family of antibiotics, where the nonproteinogenic amino acid 2,3-DAP has a fumaramoyl group appended to the β-amino functionality.[198] When dapdiamide A (69, Figure 25) binds to the active site of the glutaminase domain of a bacterial glucosamine-6-P synthase, its fumaramoyl-DAP moiety mimics a “stretched” glutamine whose electrophilic group can covalently inactivate the active site Cys.[199] In this instance the conjugated olefinic group is not built de novo into the amino acid but brought in by enzymatic acylation (of a DAP-Val dipeptide intermediate) with fumarate and then converted from the fumaroyl- to the fumaramoyl-DAP (Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Dapdiamides and anticapsin. Nonproteinogenic amino acids: red = L-2,3-DAP, blue = anticapsin.

In some members of the dapdiamide antibiotic family noted above, such as dapdiamide E (70, Figure 25), the fumaramoyl group is converted by a mononuclear iron enzyme to the epoxysuccinamoyl group, yielding the epoxysuccinamoyl-DAP as the glutamine analog which again captures the active site Cys thiolate in the glutaminase domain of glucosamine-6-P synthase.[187]

Another amino acid with a epoxycabonyl side chain is anticapsin (71, Figure 25), the warhead in bacilysin.[200] The keto group ultimately derives from the 7-OH group of prephenate, by enzymatic oxidation at a late stage in diversion of prephenate through to anticapsin.[201] Similar to dapdiamide E, the epoxycyclohexanone side chain can capture the same active site cysteine of glucosamine-6-P synthase.[202]

9. Challenges and Opportunities for Utilization of Nonproteinogenic Amino Acids as Protein Building Blocks

In this review, we have introduced the reader to a broad range of nonproteinogenic amino acids. A number of these can be readily biosynthesized as freestanding building blocks, and simply await exploitation by the protein engineer. However, several levels of potential challenges can be envisioned for the ready utilization of some of the other amino acids. Consider, for example, five examples. The olefinic allylglycine (46, Figure 22B) and the alkynoic propargylglycine (50, Figure 22C) and congeners could provide useful in providing bioorthogonally reactive functional groups in proteins. Likewise, the diazoketone amino acids DON (67, Figure 24) and azaserine (68, Figure 24) have specific reactivity features, as does aziridine dicarboxylate (Figure 1). A third set of unusual building blocks is represented by the β-oxy, γ-amino dolaisoleucine.[153]