Abstract

PCBs in building materials such as caulks and sealants are a largely unrecognized source of contamination in the building environment. Schools are of particular interest, as the period of extensive school construction (about 1950 to 1980) coincides with the time of greatest use of PCBs as plasticizers in building materials. In the United States, we estimate that the number of schools with PCB in building caulk ranges from 12, 960 to 25, 920 based upon the number of schools built in the time of PCB use, and the proportion of buildings found to contain PCB caulk and sealants. Field and laboratory studies have demonstrated that PCBs from both interior and exterior caulking can be the source of elevated PCB air concentrations in these buildings, at levels that exceed health-based PCB exposure guidelines for building occupants. Air sampling in buildings containing PCB caulk has shown that the airborne PCB concentrations can be highly variable, even in repeat samples collected within a room. Sampling and data analysis strategies that recognize this variability can provide the basis for informed decision making about compliance with health-based exposure limits, even in cases where small numbers of samples are taken. The health risks posed by PCB exposures, particularly among children, mandate precautionary approaches to managing PCBs in building materials.

Keywords: PCB, exposure, sealant, caulk, air PCB levels, exposure guidelines, Bayesian statistics

Introduction

PCBs are prevalent throughout the world – in the environment, buildings, and people - and there is a high level of awareness about PCBs in the scientific community and the general public. Historically, we have associated PCBs with industrial sources, and electrical equipment like transformers. Recent investigations have revealed that PCBs in building materials in schools and other buildings may pose a significant risk of exposure to building occupants. Several investigators have identified elevated serum PCB levels among people who live, teach and study in these buildings. Most recently Meyer (2013) reported significant differences in plasma PCB levels (four times higher in exposed compared with non-exposed residents) in a PCB-containing apartment building. They also found significant correlations between PCB indoor air to plasma levels for ten of the lower chlorinated congeners. The questions remaining are how extensive this PCB contamination is, what potential risk these PCBs pose to occupants of these buildings (for schools, this includes teachers, students and staff), and what should be done to address the issue.

The goals of this investigation were to: 1) provide a brief history of the issue for context, 2) develop an estimate of the number of US schools that may contain PCB in building materials such as caulk and sealants, 3) describe the relationship between PCBs in caulk and indoor air, using the building as the unit of analysis, and 4) briefly describe the challenges with interpreting limited environmental data and offer an example of an approach that can be used when faced with these challenges.

Brief History of PCBs in Schools

The size of the published scientific literature on PCBs is vast: a search of PubMed yielded 15, 719 citations since 1968 (January 2015). The earliest review of PCB toxicity is from Drinker (1937) who conducted rodent studies on a variety of chlorinated compounds ranging from carbon tetrachloride through chlorinated naphthalenes to chlorinated diphenyls (PCBs). Drinker reported that "the chlorinated diphenyl is certainly capable of doing harm in very low concentrations and is probably the most dangerous of the chlorinated hydrocarbons studied. “

The first PCB measurements in environmental samples were reported as interferences in analysis of chlorinated pesticides (Jensen 1972, Fishbein 1972). Even at this early stage in PCB research, there was a report of PCB contamination from building materials. The earliest report of PCB contamination in air citing building caulk as a source comes from Singmaster (1976) who identified PCBs in window caulk around a metal frame as the source of PCBs that were interfering with laboratory analysis for pesticides. He reported laboratory results showing that the caulking material contained Aroclor 1254, and a PCB mixture with a “…close correspondence …” to Aroclor 1242 was recovered from what the authors termed “…air fallout…” on oil-filmed glass dishes placed in the laboratory.

The presence of PCBs in building materials, such as paints, adhesives and the sealants used around windows and expansion joints in masonry buildings was next described (in English) by Benthe (1992) who reported elevated air levels of PCB in buildings that contained PCB sealants. Notably these air levels were dominated by the lighter, more volatile congeners such as PCB 28 and 52.

The first evidence on schools in the US comes from a report on a school at Cape Cod, Massachusetts that was found to have elevated PCB levels and closed in 1996 (Leung 1996). This finding of PCBs and the costs that would have been associated with their removal was a major factor in the decision to demolish the school. Since then, there has been an increasing awareness and concern about PCB contamination from buildings materials, but the scope of the problem, that is the number of schools that may contain PCB building materials, remains largely uncharacterized.

Number of PCB-containing schools in the US

There has been no systematic survey done in the US to gauge the number of schools that may contain PCB in caulking, sealants and/or other building materials. An estimate can be developed, however, using the number of schools constructed during the period when PCB caulking and sealants were in use, and the prevalence of PCBs in building materials as estimated by studies in several countries.

Number of schools constructed

The period of interest is approximately 1950 through 1980, which corresponds to a period of active school construction, as well as extensive PCB use in building materials. The U.S. Department of Education reports that there were 78,300 public schools in the US in 1999; of these 62% were constructed between 1950 and 1984 (Lewis 2000). This percentage (62%) yields a population of schools constructed in this period of approximately 48,000.

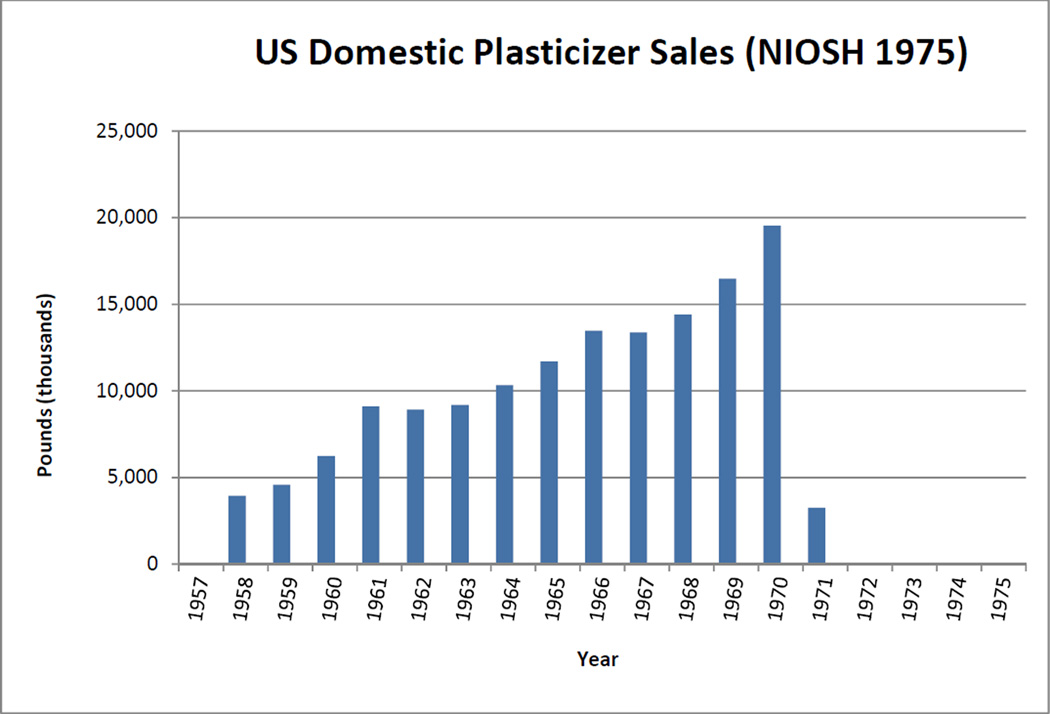

The 1950–1975 time period includes the years of most extensive use of PCB as a plasticizer. As NIOSH (1975) reported in Current Intelligence Bulletin 7, the major domestic US PCB producer, Monsanto Company, manufactured 40 million pounds of PCBs in the United States during 1974. This was down from the peak production of 85 million pounds in 1970. Monsanto's domestic sales of PCBs by grade and category from 1957 through the first quarter of 1975 are summarized in the NIOSH document and presented graphically in Figure 1. PCB sales for use as plasticizers had fallen to zero in 1974, and PCB production was banned in 1978 by the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

Fig. 1.

US domestic PCB sales for use in plasticizers – Monsanto Corporation

Estimating the Proportion of US Buildings (1950–1980) containing PCBs

Although there is no national data about the prevalence of PCB use in US construction materials, there are five studies published that offer an insight into the extent of PCB caulking and sealant materials in buildings. These surveys estimated the percentage of samples from buildings that tested positive for PCB construction materials. Of the five applicable surveys of PCBs in buildings, one was conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area, one in Toronto, Canada, one in the Greater Boston area, one in Denmark, and one in Switzerland. These studies are summarized briefly below.

Kohler (2005): The largest study was a 2005 national survey of buildings in Switzerland. This was prompted by a limited first investigation of joint sealants (caulk) in 29 public buildings in three cantons in East and Central Switzerland (survey conducted 1999 – 2000). The investigators found PCB concentrations between 22 and 216,000 ppm in 17 of 29 samples in this preliminary survey. The subsequent national survey focused on concrete buildings erected between 1950 and 1980. 1348 samples of caulk were collected and 160 indoor air samples were taken. Overall, of the 1348 caulk samples taken, 646 (48%) contained PCB at detectable levels (above 10–25 ppm), and 568 (42%) of the samples exceeded the limit of 50 ppm (above which material is required to be treated as PCB bulk product waste). In 279 samples (21%), PCB concentrations exceeded 10,000 ppm. The maximum PCB concentration encountered was 550 g/kg (550,000 ppm), that is, more than half of the mass of that particular joint sealant was comprised of PCB. There were multiple samples of caulk collected from some buildings, however, so the percentage reported as containing various levels of PCB refers to the caulk samples, not the buildings sampled.

Klosterhaus (2013): These investigators conducted a field study of PCBs in building caulk in the San Francisco Bay area (California, USA). The assessment specifically aimed to determine PCB concentrations in a small sample of buildings in relation to the construction type and building age targeting the 1950s through the 1980s. The investigators collected 29 exterior caulk samples from 10 buildings (1 to 7 samples collected per building). They found that of the 25 caulk samples analyzed, 22 (88%) contained detectable concentrations (exceeding 25 ppm) of PCBs and 10 of these (40% of all samples) exceeded 50 ppm, the US EPA PCB regulatory threshold. The levels of PCB concentrations ranged over six orders of magnitude, from 1 to 220,000 ppm. Because the sampling strategy allowed for the possibility that more than one sample was collected from each building, the investigators did not determine the exact percentage of buildings sampled that contained PCBs. However, the portion of samples greater than 10,000 ppm in the San Francisco Bay Area study (20%) was similar to other surveys indicating that these results are representative of the general situation.

Robson (2012): In 2010, these investigators sampled the exterior caulk from 70 buildings across Toronto, Canada and an additional 25 buildings chosen to include institutional buildings. The buildings were selected to give a range of building ages, as well as to include some control buildings on either side of the PCB use timeframe (1945 to 1980) to check for temporal variations. Samples were taken from ground-level outdoor joint sealants (caulking). Of the 80 buildings constructed between 1945 and 1980, 11 buildings or 14% had detectable concentrations of PCBs in sealants. The concentrations in sealants ranged from less than 40 to 82,000 ppm, with a geometric mean concentration of 46,000 ppm. Ten buildings had levels of PCBs above the regulatory threshold of 50 ppm.

Herrick (2004): In 2004, we studied 24 buildings in the Greater Boston area. Of the 24 buildings sampled, 13 contained caulking material in which detectable levels of PCBs were measured. Of these 13, 8 buildings had caulking that exceeded the 50 ppm US EPA criteria, in some cases by a factor of nearly 1,000 (range, 70.5–36,200 ppm; mean, 15,645 ppm). The buildings where elevated PCB levels in caulking were found include schools, university buildings, and other public buildings. While these 24 buildings were not chosen at random, they were buildings in which experienced bricklayers remembered installing caulking of some type in the 1970s. They did not specifically recall which buildings received PCB-containing caulk, however.

Langeland (2013): Estimates of PCB in Danish buildings reported that 22–27% of public institutions and office buildings contained >0.1 ppm PCB in sealants; 10–13% >50 ppm; and 6–9%> 5,000 ppm (Hansen 2013 citing Langeland 2013 in Danish). Similar results for the Danish survey were presented by Haven at the Eighth International PCB Workshop, Woods Hole Massachusetts 2014 (27 schools sampled, 78%>0.1 ppm; 30%>50 ppm). The national survey in Denmark reported by Langeland (in Danish) collected samples from 87 schools spread across the country. In the 87 schools, 26 were found to contain caulk/sealant in joints with ≥5,000 ppm, representing 31% of the surveyed schools. Of these schools, 11 (13%) were found to have indoor joints with PCB concentrations exceeding 5,000 ppm.

These 5 surveys are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Surveys of PCB in building caulking and sealants

| Location | Buildings (number of samples) |

PCB concentration (ppm) in detectable samplesa |

% positive for PCB |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston MA | 24 Buildings constructed/ renovated in 1970s (24 samples) | 0.56–32,600 | 54% | Herrick 2004 |

| Switzer-Land | Buildings constructed 1950–1978 (1348 samples, number buildings not reported) | 20–550,000 | 48% (multiple samples per building) | Kohler 2005 |

| Toronto Canada | 95 Buildings total, 80 constructed 1945–1980 (95 samples) | 570–82,090 | 14% overall (27% not including residential) | Robson 2012 |

| San Francisco Bay Area, CA | 10 Buildings constructed/ renovated in 1970s (29 samples) | 1–220,000 | 88% (multiple samples per building) | Klosterhaus 2013 |

| Denmark | 27 schools (average 8–10 samples per building including sealant, adhesive, paint) | 0.1 ->5000 ppm | 78% >0.1 ppm 30%>50 ppm |

Haven Woods Hole Massachusetts 2014 citing Langeland (in Danish) |

in the cases of Kohler and Herrick, the PCB concentrations were calculated as the sum of congeners PCB-28, -52, -101, -138, -153, and -180 multiplied by a factor of 5; Haven/Langeland calculated total PCB as the sum of congeners PCB-28, -52, -101, -118, -138, -153 and -180 multipled by 5; total PCB reported by Klosterhaus was the sum of 40 congeners; Robson reported the sum of 83 congeners

Proportion of schools likely to contain PCBs

The rate at which PCBs were detected in commercial/institutional (non-residential) buildings constructed during this time period ranges from 27 to 54% based upon the 5 surveys discussed above. Applying these rates to the population of US schools built during this period of PCB use, the number of schools estimated to have PCB in building caulk ranges from 12, 960 (48,000 X 27%) to 25, 920 (48,000 X 54%) schools.

Limitations

This analysis was intended to provide an estimate of the number of schools potentially impacted by PCBs. There are several important limitations to this approach. First, the estimate of the number of schools impacted is based on an extrapolation of surveys conducted in a wide range of building types, not just schools. Second, our approach uses the total number of US schools constructed between 1950–1984, the period that includes the most intense usage of PCB-containing materials. However, data from Monsanto presented by NIOSH (1975) reports that by 1974 PCB (Aroclor) sales for use as plasticizers had fallen to zero. There would be PCB-containing materials (caulking, sealants, paint) in the existing supplies that would probably be used up after 1974, as there was no ban on the use of these materials until 1977. So our approach may provide an underestimate or overestimate of schools currently impacted by PCBs. An underestimate of the true number of PCB containing schools is possible because our approach only included newly constructed schools during 1950–1984; if a school was constructed prior to 1950 but renovated or expanded between 1950–1984, it is possible that PCB-containing materials were used during the renovation, yet this school would not be included in the estimate. Conversely, many of the schools built between 1950 and 1984 that had PCB-containing materials may have been renovated after 1984, with some or all of the PCB materials removed. Those schools will still be included in our estimate because they may have been originally been constructed with PCBs, but those materials may have since been replaced. However, several investigations of secondary PCB sources have reported that PCBs migrate from the caulking to the surrounding materials. Simply replacing windows, for example without removing both the caulking, as well as the surrounding masonry material, would not prevent ongoing PCB contamination to the interior of the buildings. Third, to estimate the proportion of buildings constructed between 1950–1980 that are potentially impacted by PCBs, we relied on surveys of buildings that were focused on PCBs in caulk, specifically. PCBs were also used in other building materials such as paint, but most of these surveys did not include those materials. It is possible that the true proportion of PCB-impacted buildings, by caulk or other material(s), is greater, and therefore may have led us to underestimate the number of impacted schools. Two of the surveys (Kohler and Klosterhaus) collected multiple samples from some buildings so the proportion of PCB positive results is of the caulk samples, not the buildings sampled. Finally, our estimate of public schools impacted by PCBs is probably too high because we only have information on the number of public schools constructed from 1950–1984 from the US National Center for Education Statistics. So schools constructed in the late 1970s and early 1980s may have been outside the time period of PCB use. We do not have comparable data about the buildings constructed at colleges, universities and private schools.

It is also important to recognize the variability in PCB determination methods, in all comparisons between studies discussed in this manuscript. Variability inherent in environmental and biological sampling and analysis methods for PCBs has been discussed by Muir and Sveko (2006), who identified sources of variability associated with methods for sampling, extraction, isolation, identification and quantification of individual congeners and isomers of the PCBs and organochlorine pesticides. The best-performing laboratories participating in QUASIMEME have reported between-laboratory accuracies of 15–20% for PCB congeners. There were also differences in the methods used to calculate the total PCB concentration in caulk, sealant and paints. Some laboratories analyzed six or seven indicator congeners, then multiplied the sum of these by a factor of five; other laboratories analyzed specific congeners ranging from 40 to 83 in number, then presented the sum of these as the total PCB concentration.

Despite these limitations, it is still a worthwhile endeavor to attempt to obtain an estimate of potentially impacted schools in order to evaluate the extent of the issue and potentially remedies. A national US survey is warranted. Last, it also needs to be noted that these estimates are specific to schools. Any building constructed or renovated during this period is at risk for having PCB-containing building materials, but they are not included in our estimate.

Relationship of PCB Caulk to Air Levels, using the Building as the Level of Analysis

EPA has investigated the empirical relationship between PCBs in caulking and emission rates in a laboratory study, as a function of concentration, congener, and temperature (Guo 2011). Guo reported that the emission rate for specific PCB congeners can be estimated from the concentration of the congener in the caulk, and the congener’s vapor pressure. Using the building as the level of analysis in field studies there are several field investigations that are useful for evaluating the relationship between PCB in caulk and indoor air levels. There are 12 studies published that demonstrate this, summarized in Table 2. The majority of studies reveal that buildings containing PCB caulk and sealants can have elevated indoor air levels of PCB as well.

Table 2.

Field studies of building caulk and PCB air concentrations

| Location | Type and (number of buildings) |

PCB in caulk (range, ppm) |

PCB in air mean/median (ng/m3) |

PCB in air range (ng/m3) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | School (1) | 124,000 and 327,000 ppm | NRa | 1,000 and greater | Burkhardt 1990 |

| Germany | Office (1) | 1,000–400,000 | 440/- | Nondetected to 1251 | Benthe 1992 |

| Germany | NR | 2,000–60,000 | NR | 12–346 | Balfanz 1993 |

| Sweden | Apartments (1) | 47,000 – 81,000 | NR | 530–610 | Sundahl 1999 |

| Germany | Schools (3) | 500,000 (approx) | 635, 3541, 7490/- | 77 to 10,655 | Gabrio 2000 |

| Sweden | Flats/apartments (24) | 0–240,000 | 64.6/- | 0–600 | Corner 2002 |

| Schools (3) | 70–120,000 schools | NR | 0–37 | ||

| US | Office (1) | Nondetected-33,000 | NR | < 38.2–393 | Coughlan 2002 |

| Switzerland | Masonry buildings, number NR | NR, 42% exceeded 50 | 790/410 | Nondetected-6,000 | Kohler 2005 |

| US | School (1) | 1,830 – 29,400 | -/432 | 299 – 1,800 | Macintosh 2012 |

| Denmark | Apartments (4 sections, 1 contained PCBs) | 436–718, 430 | -/859 | 168–3843 | Frederiksen 2012 |

| US | Schools (6) | <1–440,000 | -/318 | <49–953 | Thomas (USEPA) 2012 |

| Denmark | Schools (126) | NR | NR | 10% 100–300 12% 300–3000 |

Langeland 2013 (in Danish) |

not reported

Restricting this to studies that specifically mentioned schools among the buildings investigated, there are seven published investigations. The first article that quantified the relationship between indoor air and PCB from caulk in building materials is from Burkhardt (1990, article in German). The abstract (English) reports that in several rooms of a large school building, indoor concentrations of 1000 ng PCB/m3 and more were measured, and the total PCB concentration in sealing (caulking) compounds ranged between 124,000 and 327,000 ppm. Fromme (1996) published an article in German (English abstract) reporting that measurements in 410 community rooms of schools and child-care centers found an average value of 114 ng/m3 (maximum 7,360 ng/m3) and a geometric mean of 155 ng/m3. For measurements in schools (n = 308), the geometric mean was 229 ng/m3, whereas in child-care centers (n = 102) it was 48 ng/ m3.

In a study of serum PCB levels among teachers, Gabrio (2000) reported that buildings containing material “…close to 50% (mass weight) PCB (indicator congeners times 5)”, had PCB air levels ranging from 3,643 to 13,561 ng/m3.

Corner et al. (2002) studied apartment buildings and schools in Sweden and concluded “PCB concentrations in indoor air are most probably caused by PCB-sealant on the outer part of the building structures and indicate continuous contamination of the indoor air.” PCB levels in sealant found in apartment buildings ranged from 0–240,000 ppm with corresponding PCB air levels from 0 to 600 ng/m3. In schools, PCB in sealants ranged from 70 to 120,000 ppm with PCB air levels from 0–37 ng/m3.

Macintosh (2012) found bulk samples of caulk containing 1,830 – 29,400 ppm PCB in a school building. PCB air concentrations in the building ranged from concentrations of 299 – 1,800 ng/m3 (median 432 ng/m3).

Under a consent order with the USEPA, the School Construction Authority of New York City conducted an extensive study of PCBs in 6 New York City schools (USEPA 2012). Exterior caulk samples were found with PCB content from less than 1 to 328,000 ppm, while interior caulk ranged from less than 1 to 440,000 ppm PCB. Indoor air samples were collected in several locations in each school including classrooms, cafeterias, gymnasiums, and transitory spaces. The median indoor air total PCB concentration based on 64 measurements across six schools was 318 ng/m3 with a range of <49 – 2920 ng/m3. Median air levels were highly variable between schools: <50 ng/m3 at School 4 to 807 ng/m3 at School 2. There was also considerable variability within schools; for example, indoor air levels ranged from 236 to 2920 ng/m3 in different rooms at School 3. EPA concluded that “PCB-containing caulk is a primary source of PCBs in and around school buildings. PCB emissions from caulk can potentially result in concentrations from hundreds to over a thousand nanograms per cubic meter in indoor air.” and ”PCB concentrations in indoor air were found to exceed EPA’s 2009 public health guidance levels (ranging from 70 to 600 ng/ m3 depending on age) in many school locations.” In the case of the New York City schools, fluorescent light ballasts were also potential PCB sources in the buildings. EPA concluded however that the results of the study show that emissions of PCBs from caulk, in the absence of light ballast sources, are sufficient to create indoor air total PCB concentrations two orders of magnitude or more higher than outdoor ambient concentrations.

Elevated PCB air levels inside buildings were also measured where PCB was found only in exterior caulk. Data from School #6, for example, reported elevated PCB air levels but only trace amounts of PCB were measured in interior caulk, probably as a result of contamination from the exterior caulk which contained more than 100,000 ppm PCB. EPA concluded that “PCBs-containing caulk is a primary source of PCBs in and around school buildings. PCBs from exterior caulks around windows and mechanical ventilation system air intakes can lead to elevated concentrations in indoor spaces.”

The Danish national survey (Langeland 2013) in Danish) reported the results of air sampling in 126 schools. Of these 10% of the schools had PCB air concentrations measured in the range of 100–300 ng/m3; 12% ranged from 300–3000 ng/m3.

Recommended guidelines and action level of indoor air PCBs

The following reference values for indoor air PCB levels were summarized and reviewed by Hansen (2013). The earliest indoor air exposure level was recommended in Germany (1996) set as an annual mean action value of 300 ng/m3, with an intervention value was 3000 ng/m3 (calculated as PCB6 multiplied with a correction factor of 5). Supplementary values were established by the health authority in Schleswig-Holstein including thresholds for recommended indoor cleaning and sanitation procedures. Switzerland prepared a maximal tolerable annual mean value for indoor home exposure to PCB of 2000 ng/m3 and 6000 ng/m3 for exposures in schools and other institutions using the same analytical method as in Germany. The Danish Health and Medicines Authority introduced two recommended action levels for PCB in indoor air (2009): levels exceeding 3000 ng/m3 called for immediate action, and exposure to levels between 300 and 3000 ng/m3 were considered to be a possible health risk requiring an action plan to reduce the levels. This was later modified to specify that levels between 2000 and 3000 ng/m3 required action within one year. In the US, the EPA has established a site-specific action level of 50 ng PCB/m3 requiring further investigation, and an acceptable long-term average exposure concentration of 300 ng/m3. For schools the USEPA has calculated what are described as prudent public health levels that maintain PCB exposures below the "reference dose" - the amount of PCB exposure that EPA does not believe will cause harm (20 ng PCB/kg body weight per day). Indoor air levels recognized PCB intakes from average exposure to PCBs from all other major sources. The levels were calculated for all ages of children from toddlers in day-care to adolescents in high school as well as for adult school employees. These levels are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

US EPA Guidance levels for airborne PCBs in schools

| Public Health Levels of PCBs in School Indoor Air (ng/m3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age | Age |

| 1-<2 yr | 2-<3 yr | 3-<6 yr | 6-<12 yr | 12-<15 yr | 15-<19 yr | 19+ yr |

| Elementary School |

Middle School |

High School |

Adult | |||

| 70 | 70 | 100 | 300 | 450 | 600 | 450 |

Other levels have been set by conducting site-specific risk assessments that included considerations of specific local conditions. In one Massachusetts elementary school, the lowest target concentration for the annual average concentration of PCBs in indoor air of a classroom was set at 230 ng/m3 (http://lps.lexingtonma.org/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&ModuleInstanceID=1499&ViewID=7b97f7ed-8e5e-4120-848f-a8b4987d588f&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=1056&PageID=963). In a California school, the EPA established a health based target concentration of 200 ng/m3 (http://www.smmusd.org/PublicNotices/EPACoverLetter012814.pdf).

The Challenge of Variability in Measured PCB Air Levels and Proposed Approach

Variability in Environmental Data

There is little data available about the variability in PCB indoor air levels within buildings. The surveys of 6 schools in New York City (EPA 2012) showed that there can be very substantial variability in air PCB levels measured in a single building. For example, one school (#3) was found to have air levels that varied between rooms by more than a factor of 10 in a single sampling period (range 236–2920 ng/m3). Data from Balfanz (1993) examined the effect of season on indoor air levels, and laboratory research (Guo 2011) and a Danish study (Lyng presented at the Eighth International PCB Workshop Woods Hole Massachusetts 2014) of indoor air temperature and PCB air concentrations have demonstrated that temperature is a major source of variability in PCB levels. Ventilation is also a strong predictor of indoor PCB concentrations (Lyng 2014), and analytical uncertainty (which can be 20–30%), wind speed and outdoor barometric pressure must be considered as sources of variability in indoor air levels.

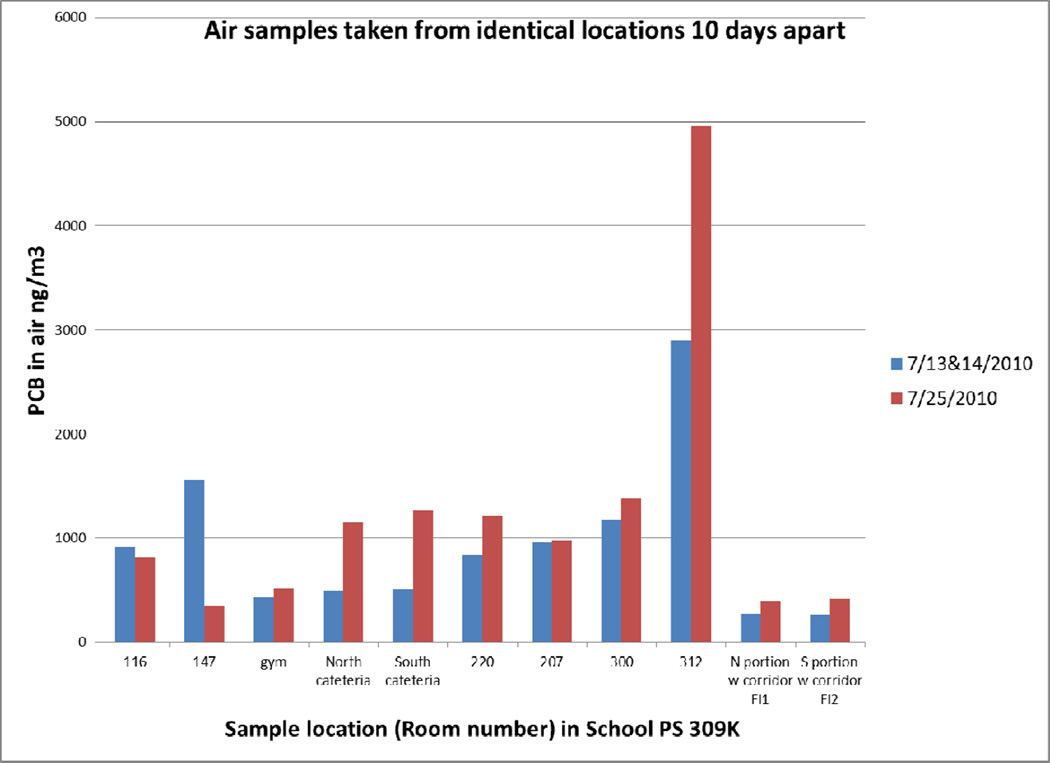

The study in New York City (EPA 2012) included some repeat air samples taken in identical locations, this data is presented in Figure 2. Air samples were collected from identical locations in Public School (PS) 309 in accordance with USEPA Method TO-10A Determination of Pesticides and Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Ambient Air Using Low Volume Polyurethane Foam (PUF) Sampling followed by Gas Chromatographic/Multi-Detector Detection (GC/MD). Samples in classrooms and offices were collected near the center of each room in the breathing zone at desk level, away from doors, windows, and vents. All windows and doors were closed and general ventilation systems were operational during the air sampling events. There is no central air conditioning at PS 309, and window air conditioners present in study areas were not operational during the sampling.

Figure 2.

Repeat air samples 10 days apart identical sampling locations NYC school

The results of these paired air samples collected in identical locations approximately 10 days apart illustrate the variability that may be inherent in environmental PCB measurements in indoor air. Comparing the ratios of the first day’s sample result to the second day’s sample, two of the eleven pairs were higher on day 1 than day 2, while the remainder were lower, ratios ranged from 0.40 to 0.99. The greatest discordance between the sample pairs, however was in classroom number 147 with a day 1: day 2 ratio of 4.44. Climactic conditions were approximately the same on both sampling dates, as temperatures averaged 78 degrees F, range 73–83 (26 C, range 23–28) on 13 July, and average 82 degrees F range 70–93, (28C, range 21–34) on 25 July, with rain reported on both days.

An Approach for Interpreting Limited Environmental Data for PCBs

Variations of this magnitude in repeated measures of airborne contaminants are not uncommon. For example, in occupational settings, a comprehensive investigation of sources and nature of within- and between- worker variation in measured exposures (Symanski 2006) found that the day-to-day variation in exposures generally exceeded the variation between workers. Studies in occupational environments have attempted to address the effect of the variability underlying environmental measurements by developing strategies for reaching defensible decisions based upon limited numbers of samples.

In occupational exposure settings, groups of individuals having the same general exposure profile are defined by the American Industrial Hygiene Association (AIHA 2006) as Similar Exposure Groups (SEGs). The 95th percentile of an exposure distribution for a SEG is used to place a SEG into exposure categories, and those categories provide a way of deciding what actions need to be taken for the SEG. For example, if the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution (assumed lognormal distribution) is greater than the exposure limit then action to reduce/control exposure would be indicated (AIHA 2006). If the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution is less than the exposure limit then its category can be used to determine what, if any, actions need to be taken. For example, if the 95th percentile of an exposure distribution is 50–99% of the exposure limit, then the response may be implementation of medical surveillance and/or special training. The categories recommended by the AIHA are:

| Category | Exposure level |

|---|---|

| 0 | Trivial (95th percentile <0.01 x exposure limit) |

| 1 | Highly controlled (95th percentile >Category 0 but <0.1 x exposure limit) |

| 2 | Well controlled (95th percentile > Category 1 but <0.5 x exposure limit) |

| 3 | Controlled (95th percentile> Category 2 but < exposure limit |

| 4 | Poorly controlled (> exposure limit) |

There are several approaches to calculate the probability that the true exposure profile falls within a specific range, given a limited number of measurements. An approach that has been used in studies of exposures in occupational settings is Bayesian Decision Analysis (BDA) (Hewett 2006). This analytical approach is useful for making decisions about where exposure measurements fall in reference to a guideline limit value, when small numbers of measurement are available. BDA utilizes the combination of a “Prior” distribution (e.g., professional judgment) and a “Likelihood” distribution (sampling data only) to produce a “Posterior” distribution. The Posterior distribution is the probability that the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution lies in each of the AIHA exposure categories.

BDA uses sampling data, a user selected exposure limit and a defined set of exposure categories. Using these inputs, the investigator calculates the probability of the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution falling within each category. BDA uses maximum likelihood methods to determine if the 95th percentile falls within Category. The assumptions in the BDA as applied here are that the data are lognormally distributed, that the GSD falls within this range 1.05 ≤ GSD ≤ 4 and the GM is no more than 5 times the exposure limit and is greater than zero (a very small default value is assumed, e.g., 5 × 10-6). The software used to perform these BDA calculations was IH DataAnalyst V1.27 (IHDA Exposure Assessment Solutions, Inc, Morgantown, West Virginia, http://www.oesh.com/software.php.)

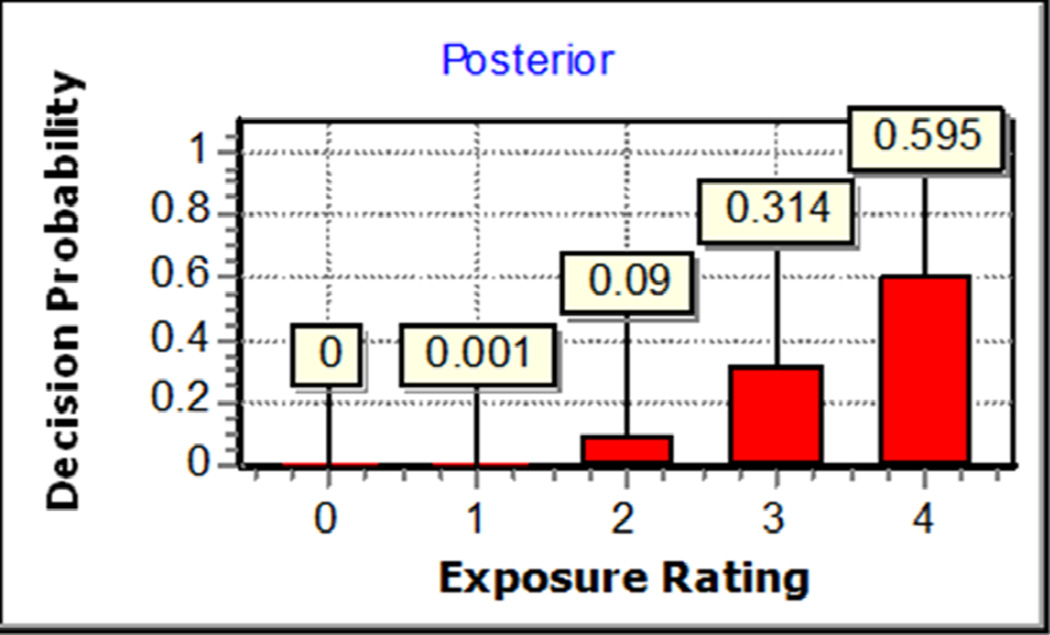

As an example, consider the set of PCB air measurements reported for a room of a school before and after cleaning procedures (Best Management Practices or BMP), where the reference guideline value from the Region 9 EPA was 200 ng/m3 PCB. The censored data in the PCB samples were incorporated into the analysis using the maximum likelihood method.

In Building C, for the pre BMP condition there were only 2 samples, one was ND (less than 70 ng/m3); the other was 120 ng/m3. The traditional approach, as was employed by the group that collected these samples, was to simply compare the measured concentrations against the threshold value. This led to the determination that no samples were detected above the threshold of 200 ng/m3. A true, but potentially misleading, conclusion. Using the Bayesian Decision Analysis approach, and assuming an non-informative prior, we would say that there is a 9% probability that the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution is in category 2 (11–50% of the exposure limit), and a 31.4% probability that is in category 3 (51%–100% of the Exposure Limit) and a 59.5% chance that it in category 4 (above the exposure limit of 200 ng/m3). Put another way, there is a greater than 50% chance that the 95th percentile exposure concentration actually exceeds the 200 ng/m3 limit. This is depicted in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

Probability of 95% exposure distribution by category pre-BMP condition

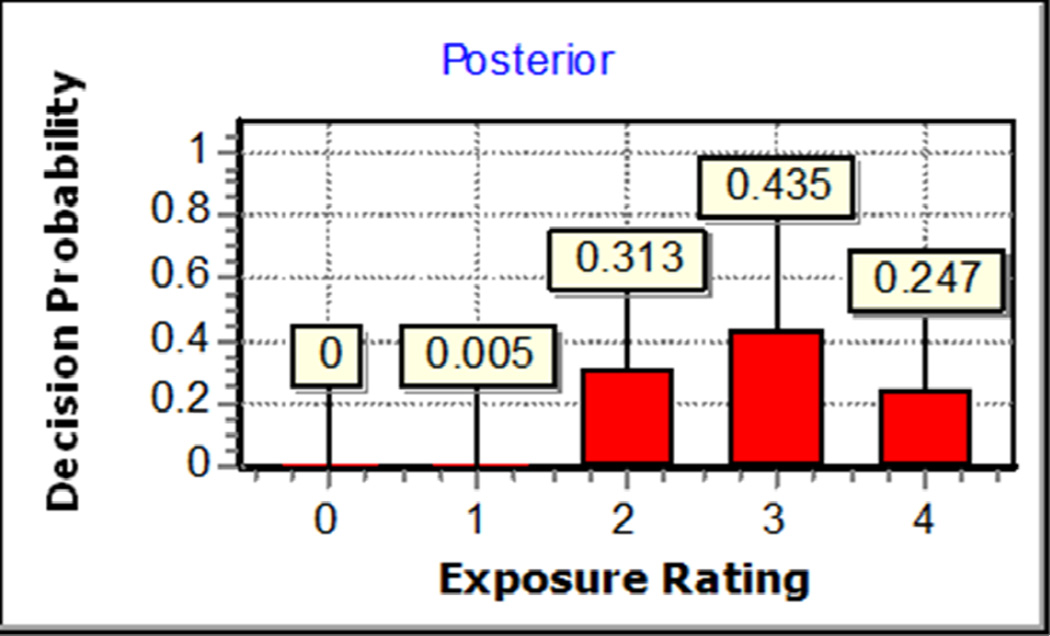

A comparable depiction of the probability of exceeding the 200 ng/m3 reference value can be presented for the post BMP condition. In this case, there were 5 samples collected, 4 were ND (less than 70 ng/m3); the other was 110. The same estimation procedure (BDA) shows that there is a 31.3% probability that the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution is in category 2 (11–50% of the Exposure Limit) and a 43.5% chance that the 95th percentile lies in category 3 (51–100% of the exposure limit) and a 24.7% chance that it lies in category 4 (above the exposure limit). This is depicted in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Probability of 95% exposure distribution by category post-BMP condition

The BDA shows that after BMP remediation the probability of having the 95th percentile of the exposure distribution in Category 4 (Poorly Controlled) decreases from approximately 60% to 25% but there is still over a 44% probability that the 95th percentile is in Category 3 (greater than 50% of our exposure limit of 200 ng/m3).

BDA does not make the decision as to whether or not the probabilities are acceptable. The decisions on what actions will be taken if the 95th percentile falls into each category should be made a priori. For example, is it acceptable to have a 25% probability that the 95th percentile of the exposures in the building be above the exposure limit of 200 ng/m3? If it is not, what intervention would be needed? Another question is “What actions need to be taken if there is a 44% probability that the exposures have a 95th percentile that is in Category 3 (greater than 50% of the exposure limit)?” A strength of this approach is that we are able to estimate the likelihood of exposure exceedances, even when the number of samples is small, i.e., <6 and there are non-detect values. Another benefit of BDA is that it provides an ability to include professional judgment in the analysis (if desired). In these analyses in this manuscript a non-informative prior was used, meaning no professional judgment was assumed. In this situation, the pre and post BMP PCB sampling data alone determined the probabilities for each exposure category.

Discussion and Conclusions

The issue of PCBs in schools requires attention. There is unequivocal evidence showing that PCBs are common in building materials, causing PCB contamination of the building environment. Airborne PCB levels in excess of health-based guidelines have been frequently measured in these buildings. In addition to exposure by inhalation, children are at particular risk of exposure by touching contaminated materials. People occupying these buildings, including students, teachers and staff of schools, residents, or workers in contaminated buildings have been shown to have elevated serum PCB levels. PCBs are a known hazard that, based on our calculations, are likely to still be impacting thousands of buildings, including an estimated 12, 960 to 25, 920 US schools. Additional surveys of the extent, and potential health impact of PCBs in building materials are essential to inform decisions on risk assessment and management. These surveys need to be carefully designed to recognize and account for the variability in PCB concentrations in building materials, and particularly in PCB air levels even between measurements made within a single room. Decisions must be based upon valid sampling and data analysis strategies that will produce reliable estimates of the likelihood that PCB exposures are below or above health-based guidelines. Given the uncertainties surrounding the associations between PCB exposures and health effects, particularly among children, precautionary approaches to managing PCBs in building materials are warranted.

Table 3.

Airborne PCB samples California school

| BUILDING C | # samples | # ND | Detectable<200 ng/m3 | Detectable > 200 ng/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre BMP | 2 | 1 | 120 | None |

| Post BMP | 5 | 4 | 110 | None |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Harvard NIEHS Center for Environmental Health Grant number P30ES000002.

References

- AIHA. A Strategy for Assessing and Managing Occupational Exposures. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Balfanz E, Fuchs J, Kieper H. Sampling and Analysis of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) in Indoor Air due to Permanently Elastic Sealants. Chemosphere. 1993;26(5):871–880. [Google Scholar]

- Benthe Chr, Heinzow B, Jessen H, Mohr S, Rotard W. Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Indoor air contamination due to thiokol-rubber sealants in an office building. Chemosphere. 1992:1481–1486. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt U, Bork M, Balfanz E, Leidel J. Indoor Air Pollution by Polychlorinated Biphenyl Compounds in Permanently Elastic Sealants. Offentl Gesundheitweis. 1990;52(10):567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan KM, Chang MP, Jessup DS, Fragala MA, McCrillis K, Lockhart TM. Characterization of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Building Materials and Exposures in the Indoor Environment. Proceedings: Indoor Air 2002. The 9th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate; June 30–July 5, 2002; Monterey, CA, USA. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Corner R, Sundahl M, Rosell L, Ek-Olausson B, Tysklind M. PCB in Indoor Air and Dust in Buildings in Stockholm. Indoor Air 2002, proceedings from the 9th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate; Monterey, California. June 30–July 5; 2002. pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Currado G, Harrad S. Comparison of polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations in indoor and outdoor air and the potential significance of inhalation as a human exposure pathway. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000;32:3043–3047. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J, Law RJ. Developments in the use of chromatographic techniques in marine laboratories for the determination of halogenated contaminants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J Chromatogr A. 2003;1000(1–2):223–251. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drinker CK, Warren MF, Bennet GA. The Problem of Possible Systemic Effects from Certain Chlorinated Hydrocarbons. J Ind Hyg Tox. 1937; Paper presented at the Symposium on Certain Chlorinated Hydrocarbons, Harvard School of Public Health; June 30, 1937; 1937. pp. 283–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein L. Chromatographic and biological aspects of polychlorinated biphenyls. J Chromatogr. 7. 1972;68(2):345–426. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)85724-6. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H, Baldauf AM, Klautke O, Piloty M, Bohrer L. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) in Caulking Compounds of Buildings-Assessment of Current Status in Berlin and new indoor air sources [in German] Gesundheitswesen. 58(12):666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen M, Meyer HW, Ebbehoj NE, Gunnarsen L. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in indoor air originating from sealants in contaminated and uncontaminated apartments in the same housing estate. Chemosphere. 2012;89(4):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabio T, Piechotowski I, Wallenhorst T, Klett M, Cott L, Friebel P, Link B, Schwenk M. PCB-Blood Levels in Teachers, Working in PCB-Contaminated Schools. Chemosphere. 2000;40:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Liu X, Krebs KA, Stinson RA, Nardin JA, Pope RH, Roache NF. Emissions from Selected Primary Sources. U.S. EPA: National Risk Management Research Laboratory; 2011. Laboratory Study of Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Contamination and Mitigation in Buildings Part 1. EPA/600/R-11/156, October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Keiding L. Health risks of PCB in the indoor climate in Denmark-Background for setting recommended action levels. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Herrick RF, McClean MD, Meeker JD, Baxter LK, Weymouth GA. An Unrecognized Source of PCB Contamination in Schools and Other Buildings. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(10):1051–1053. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett P, Logan P, Mulhausen J, Ramachandran G, Banerjee S. Rating exposure control using Bayesian decision analysis. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2006;3(10):568–581. doi: 10.1080/15459620600914641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontsas H, Pekari K, Riala R, Back B, Rantio T, Priha E. Worker Exposure to Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Elastic Polysulphide Sealant Renovation. Ann. occup. Hyg. 2004;48(1):51–55. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/meg092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klosterhaus S, McKee LJ, Yee D, Kass JM, Wong A. Polychlorinated biphenyls in the exterior caulk of San Francisco Bay Area buildings, California, USA. Environ Int. 2014;66:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler M, Tremp J, Zennegg M, Seiler C, Minder-Kohler S, Beck M, Lienemann P, Wegmann L, Schmid P. Joint Sealants: An Overlooked Diffuse Source of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Buildings. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:1967–1973. doi: 10.1021/es048632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S. The PCB Story. Ambio. 1972;1:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Langeland M, Jensen MK. Kortlægning af pcb i materialer og indeluft. Fase 2 rapport. Grontmij/COWI. 2013 Apr [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann GM, Christensen K, Maddaloni M, Phillips LJ. Evaluating health risks from inhaled polychlorinated biphenyls: research needs for addressing uncertainty. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;23(2):109–113. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408564. Epub 2014 Oct 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L, Snow K, Farris E, Smerdon B, Cronen S, Kaplan J. Condition of America’s Public School Facilities: 1999 NCES 2000-032. U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liebl B, Schettgen T, Kerscher G, Broding H, Otto A, Angerer J, Drexler H. Evidence for Increased Internal Exposure to Lower Chlorinated Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) in Pupils Attending a Contaminated School . Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2004;207:315–324. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S. Source of Toxin Revealed at Bourne School. Boston Globe. 1996 Mar 21; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lyng N, Trap N, Andersen HV, Gunnarsen L. Proceedings Indoor Air 2014. Hong Kong: ISIAQ; 2014. Ventilation as mitigation of PCB contaminated air in buildings: review of nine cases in Denmark. 2014. HP 1239. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh DL, Minegishi T, Fragal MA, Allen JG, Coghlan KM, Stewart JH, McCarthy JF. Mitigation of Building-related Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Indoor Air of a School. Environ Health. 2012;11(24):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir D, Sverko E. Analytical methods for PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in environmental monitoring and surveillance: a critical appraisal. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;386(4):769–789. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0765-y. Epub 2006 Sep 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. Polychlorinated (PCBs) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 1975. Nov 3, [Accessed July 2012]. Current Intelligence Bulletin 7. (1975). http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/1970/78127_7.html. [Google Scholar]

- Robson M, Melymuk L, Csiszar SA, Giang A, Diamond ML, Helm PA. Continuing sources of PCBs: the significance of building sealants. Environ Int. 2010;36(6):506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.009. Epub 2010 May 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singmaster JA, Crosby DG. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1976;16(3):291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01685891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundahl M, Sikander E, Ek-Olaussen B, Hjorthage A, Rosell L, Tornevall M. Determinations of PCB within a project to develop cleanup methods for PCB-containing elastic sealant used in outdoor joints between concrete blocks in buildings. J. Environ. Monit. 1999;1:383–387. doi: 10.1039/a902528f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symanski E, Maberti S, Chan W. A meta-analytic approach for characterizing the within-worker and between-worker sources of variation in occupational exposure. Ann Occup Hyg. 2006;50(4):343–357. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mel006. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency “Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in School Buildings: Sources, Environmental Levels, and Exposures” Au:Kent Thomas, Jianping Xue, Ronald Williams, Paul Jones, Donald Whitaker; EPA/600/R-12/051. 2012 Sep 30; ( http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/hazard/tsd/pcbs/pubs/caulk/pdf/pcb_EPA600R12051_final.pdf).