Abstract

Celiac disease may appear both in early childhood and in elderly subjects. Current knowledge of the disease has revealed some differences associated to the age of presentation. Furthermore, monitoring and prognosis of celiac subjects can vary depending on the pediatric or adult stage. The main objective of this review is to provide guidance for the adult diagnostic and follow-up processes, which must be tailored specifically for adults and be different from pediatric patients.

Keywords: Celiac disease, Diagnosis, Complications, Gluten intolerance, Duodenal biopsy

Core tip: Current knowledge of celiac disease (CD) has revealed differences linked to the age of onset. These differences are related to the epidemiology, pathogenicity, clinical signs and prognosis of the disease. Here we present a comprehensive review of CD focusing on the age-specific management of patients. The knowledge of particular aspects linked to either adults or children would improve both the diagnosis and follow-up of this disease. This review can be helpful to the clinician involved in the management of adult and pediatric patients.

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune inflammatory enteropathy triggered by gluten intake in genetically susceptible persons. It was initially described in children and, for many years, has been considered an almost exclusively pediatric entity. The main clinical presentations in the pediatric population include, malnutrition and growth delay along with persistent diarrhea and high mortality[1]. Although the long standing assumption is that CD develops in childhood, the disease can occur at any age. The epidemiology and symptomatology of CD have both considerably changed in recent years, with a significant increase in adult prevalence that was not previously suspected[2]. The clinical presentation of CD has also changed, from typical malnutrition to oligosymptomatic cases such as anemia, osteoporosis and even asymptomatic cases diagnosed by screening high-risk groups[3,4].

The aim of this review is to describe the main differences in CD according to age and highlight the most characteristic aspects of its adult forms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

CD is a disorder more frequent than previously described. The current prevalence of CD ranges between 1/100-1/500 subjects depending to the different populations surveyed and the method employed, with a higher positive diagnosis in females[2]. The accuracy of CD prevalence has been substantially improved by the high sensitivity and specificity of serological tests detecting anti-endomysial, anti-tissue transglutaminase or anti-deamidated gliadin antibodies. These tests have allowed screening of large cohorts, which resulted in estimating CD prevalence as high as 1% of the general population, both in Europe and North America[5]. However, most of these studies are focused on children. A recent epidemiological study in Catalonia that used serology to analyze prevalence, showed that CD prevalence in children (1/71) was five times higher than in adults (1/357). The authors proposed a tendency towards latency in adults, which would explain the lower prevalence of CD during adulthood[6]. Similar studies in Brazil and India also found twice the CD frequency in children[7,8].

However, these data are in contrast with the observed prevalence in adult populations from European countries such as the United Kingdom (1.2%)[9] and, more surprisingly, Finland, where a 2.4% prevalence of CD was demonstrated by biopsy in a population of adults over fifty years of age[10]. The pediatric population was not analyzed in these studies, but prevalence of over 1%, even in older populations, is similar to that observed in pediatric studies. A recent systematic review on world CD frequency in recent years, mainly based on European studies, found variable ratios of prevalence and incidence, which was similar, in many cases, between children and adults[2].

Although a hypothesis based on the evolution of pediatric CD towards latency would explain a lower frequency in adults; more studies on the natural evolution of this disease are needed in order to confirm it. It is clear that adult forms are becoming more frequent, sometimes reaching similar or even higher numbers than those of the pediatric population. The screening methods and the type of population selected may have an influence, since in high-risk groups of adults as well as in first-degree relatives, affected individuals may exceed 15%[3]. It must also be taken into account that, as we discuss below, studies based on serological screening may not really demonstrate adult prevalence, where antibody titers are low or even negative, while histological damage and symptoms are compatible with CD[11].

SYMPTOMATOLOGY

The clearest difference between children and adults is the clinical expressiveness of the disease at the time of diagnosis. Different studies have shown that classic clinical malabsorption pattern is frequently observed in children during diagnosis, while classical symptoms occur in less than 25% of adult cases[12]. Table 1 contains an overview of different clinical manifestations in CD according to the presentation age.

Table 1.

Age-related major clinical findings at celiac disease diagnosis

| Children < 2 yr | Children > 2 yr | Adults |

| Diarrhea | Loose stools | Dyspepsia/irritable bowel syndrome |

| Malnutrition | Iron deficiency | Iron deficiency |

| Bloating | Abdominal pain | Constipation |

| Vomiting | Dyspepsia | Osteoporosis |

| Irritability | Growth delay | Arthritis |

| Muscular atrophy | Headache | Hypertransaminasemia |

| Anemia | Pubertal delay | Extraintestinal symptoms |

A tendency towards lower clinical manifestations can be observed as age increases[4]. In older children and adults only limited symptoms are prevalent, which often consist of an increase in stool volume, or intestinal gas generated by lactose malabsorption or bacterial overgrowth. In fact, constipation may be the only manifestation in a celiac adult.

Extraintestinal symptoms or manifestations are quite frequent in adult CD, and may appear associated with other digestive symptoms such as asthenia, oral sores, osteoporosis or skin lesions. In fact, some patients only present these extraintestinal symptoms at diagnosis. Although celiac children may exhibit non-digestive manifestations, these are less frequent and show a predominant digestive symptomatology[13].

There are numerous diseases associated with CD in children and adults. However, the presence of associated pathologies in adults seems to be more frequent and may have an autoimmune origin like CD. Autoimmune disorders such as autoimmune thyroiditis, type I diabetes, Sjögren’s syndrome or dermatitis herpetiformis have been linked to CD[14,15].

Even though malnutrition is a frequent manifestation in CD, mainly in adults, excessive weight or obesity may also be present at diagnosis. Recent studies have shown that more than half the adults diagnosed with CD have obesity while only 15% of them are below their normal weight[16,17]. These figures are from European and North American studies, where the prevalence of obesity among the adult population is high. Excess weight can also be observed in children at a lower frequency. Therefore, excess weight in an adult must not be a reason to lower the suspicion threshold for CD.

Functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome are two functional digestive pathologies, which are quite prevalent in the adult population, but are also seen during infancy. CD prevalence in adults with functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome can rise to over 10% of cases, as reported in some studies. Currently, before diagnosing both functional pathologies in adults, an underlying CD must always be ruled out, either by serology or endoscopy[18,19].

DIAGNOSIS

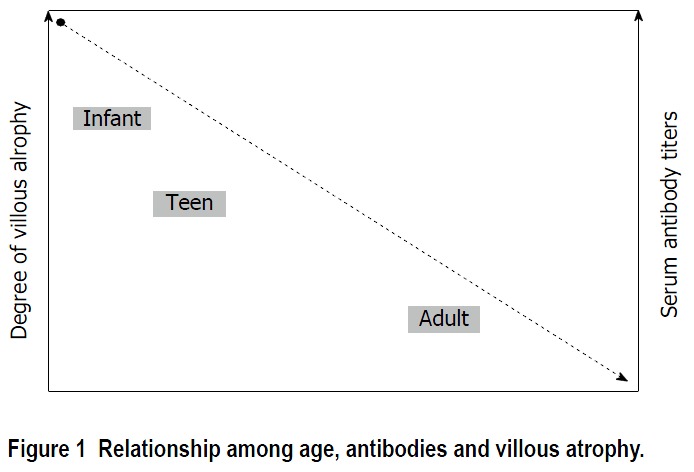

The diagnosis of CD is based on the presence of serum antibodies against deamidated antigliadin, antiendomysium or anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies. In addition, the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytosis and/or villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia of small-bowel mucosa, and clinical remission after withdrawal of gluten from the diet, are also used for diagnosis antitransglutaminase antibody (tTGA) titers and the degree of histological lesions inversely correlate with age[12]. Thus, as the age of diagnosis increases antibody titers decrease and histological damage is less marked. It is common to find adults without villous atrophy showing only an inflammatory pattern in duodenal mucosa biopsies: Lymphocytic enteritis (Marsh I) or added crypt hyperplasia (Marsh II), as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Relationship among age, antibodies and villous atrophy.

This lower clinical, analytical and histological expressiveness in adult forms makes their diagnosis more complex than in pediatric forms. The European Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Society (ESPGHAN) criteria were edited in 2012 for CD diagnosis in children. These current pediatric criteria allow CD diagnosis upon finding high tTGA titers, without the need for a duodenal biopsy[20]. This is, again, based on the evidence of high antibody titers having a high predictive value for villous atrophy, and thus avoiding the need for biopsy. Thus, in pediatric patients, up to 75% of duodenal biopsies can be avoided. However, the presence of high antibody titers (> 10 times normal levels) that allow bypassing biopsies, appear in less than half of adult cases[21]. Besides, currently, when adult subjects present symptoms such as dyspepsia, an upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy is routinely performed independently of CD serology[18].

Therefore, correct diagnosis can only be achieved on a few occasions, where high tTGA titers are present in adult patients. For low titers, duodenal biopsies have to be performed to verify histological damage and begin a gluten-free diet. However, adult patients with symptoms and serology could have two types of enteropathies based on duodenal biopsy: (1) Duodenal mucosa with slight villous atrophy and increased intraepithelial lymphocytes (Marsh 3A). When a DQ2 or DQ8 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype is found, the patient should be put on a gluten-free diet, and the clinical and histological response must be subsequently evaluated. Thus, 4 out of the 5 criteria for gluten-sensitive enteropathy diagnosis, proposed by Catassi and Fasano[22], would be fulfilled (Table 2); and (2) Mucosa with no villous atrophy, but with a marked increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (> 25 LIE/100 enterocytes). Such cases present lymphocytic enteritis (Marsh I) with diverse etiologies that are independent of CD: Helicobacter pylori infection, Non Steroid Anti-inflammatory Drugs intake, infections or Crohn’s disease, among others. If none of these conditions are suspected, and the patient has a CD-compatible HLA genotype, the biopsy study can be extended by: Analyzing IgA antitransglutaminase subepithelial deposits[23] and flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry of the duodenal lymphocytic population, in order to evaluate the prevalence of gamma-delta receptor expression in T lymphocytes, which could point to CD[24].

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for celiac disease proposed by Catassi and Fasano[22]

| The presence of signs and symptoms compatible with celiac disease |

| Positivity of serum celiac disease IgA class autoantibodies at high titer |

| Presence of the predisposing genes HLA-DQ2 and/or -DQ8 |

| Celiac enteropathy at the small intestinal biopsy1 |

| Resolution of the symptoms and normalization of serology test following the implementation of a gluten-free diet2 |

Including Marsh-Oberhuber 3 lesions, Marsh-Oberhuber 1-2 lesions associated with positive celiac antibodies positive at low/high titer, or Marsh-Oberhuber 1-3 lesion associated with IgA subepithelial deposits;

Histological normalization in patients with sero-negative celiac disease or associated IgA deficiency. At least 4 of 5 (or 3 of 4 if the HLA genotype is not performed). HLA: Human leukocyte antigen.

Although, these tools could implicate CD, in order to fulfill the criteria proposed by Catassi, the lymphocytic enteritis response to the gluten-free diet has to be evaluated, along with a biopsy, once clinical improvement is seen. The evolution of lymphocytic enteritis associated with adult CD, and its relation to complications are not clearly understood. Therefore, once lymphocytic enteritis is found in an adult subject with negative serology, CD diagnosis must be carefully made with a subsequent follow-up check.

POSSIBLE PATHOGENIC DIFFERENCES

A number of studies have evaluated intestinal microbiota in relation to CD[25]. The colonization process during the early stages of life, and the interaction between the microbiota and the immune system, could have an important role in the pathogenesis of CD.

The composition of the intestinal microbiota, both in duodenal biopsies and stool samples of celiac children and adults, exhibits alterations in relation to non-celiac controls[26]. Age-related differences in duodenal microbiota composition have also been found between celiac and non-celiac subjects[27,28]. In general terms, the richness in intestinal microbiota increases with age, as expected. Moreover, differences were also observed in the kind of bacterial community in children and adults. Although these are speculative data, it could be hypothesized that the interaction between microbiota and the immune system differs based on the age-varying microbial composition. This would originate a different response, which could be related to the clinical, analytical and histological responses, we see in adults.

Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) have an important role in the immune response, which is part of the pathogenesis of CD. Within these lymphocytes, the most characteristic feature of CD, independent of the presentation age, is the increase in CD3+ lymphocytes, which express the γδ receptor. The function of γδ IELs is not known, but they could have a regulatory role in the immune response[29]. This would explain their relationship with the degree of villous atrophy both in children and in adults[30]. Another characteristic population is CD3-, which is inversely related to age. It appears at twice the frequency in children under three years of age than adults[31]. Changes in IEL population may be related to the presentation form according to age. Advances in the knowledge of these lymphocytes and CD pathogenesis will offer answers in the near future.

EVOLUTION AND PROGNOSIS

CD treatment consists of a strict life-long gluten-free diet (GFD). Once the diet has begun, a clinical response can be observed in most patients. However, in contrast to children, up to 30% adults may still have symptoms despite having withdrawn gluten from their diet. This fact demands investigation, in adult forms, of other possible causes associated to symptoms in celiac patients: Lactose intolerance, bacterial overgrowth, pancreatic insufficiency, microscopic colitis or refractory CD.

Not only do a high percentage of adults not respond to the GFD, there is also an observable lack of histological recovery during follow-up. Recent studies have shown that more than 50% of adults do not recover from villous atrophy, even after two years on a proper diet[32]. In the case of children, even though information is limited, there is duodenal mucosa recovery in the vast majority (95%) during the first two years after the diagnosis[33]. The main cause of this lack of mucosal recovery in adults could be the continuous and inadvertent ingestion of small amounts of gluten. This cause is likely to be more frequent in adults, since the daily diets of children are more closely monitored.

A strict adherence to the diet along with duodenal mucosa normalization should be the main objectives of adult follow-up. The lack of dietary compliance and persistence of histological damage, are two factors associated with the development of lymphoproliferative disease in adults, which is the most severe complication associated to CD[34]. A recent Swedish population study noted that celiac patients with persistent villous atrophy, during follow-up, had twice the risk of developing a malignant lymphoproliferative disease, mostly T lymphoma[35]. These findings make it necessary to recommend a control biopsy during the second year after diagnosis, in order to evaluate villous atrophy recovery. Thus, those individuals at higher risk of developing CD-associated complications could be identified and a closer follow-up performed in conjunction with monitoring dietary compliance.

CD patients have other complications that should be monitored. Decrease in bone mineral density is probably due to vitamin D deficiency. However, the risk of fracture in CD patients is unclear, and the predictive value of bone densitometry is not sufficient to identify individuals at high-risk of fracture. It seems reasonable to perform bone densitometry on adult CD patients in high-risk situations who include post-menopausal women, men > 55 years and those with known osteopenia before the diagnosis of CD[36]. Further studies are required to identify the efficacy and cost-effectiveness to perform bone densitometry on all adult CD patients at diagnosis, and to identify the follow-up frequency of performing such analysis[37]. Children may have reduced bone mass at diagnosis. However, they are more likely to have fully restored bone mass after 6-12 mo of a GFD than adults. Bone densitometry is not generally required in newly diagnosed pediatric patients with uncomplicated CD. Special attention to ensure normal growth and development is recommended in children[38].

Hyposplenism may affect more than one-third of adult CD patients, while it is not a complication in pediatric patients. The incidence of hyposplenism correlates with the duration of pre-exposure to gluten, and it is higher in those with concomitant autoimmune disorders or pre-malignant conditions[39]. Based on these associated factors, splenic function may be determined in a selected group of adult CD patients: Older patients at diagnosis, those with concomitant autoimmune or premalignant disorders, and patients with a previous history of major infections or thromboembolism. As a diagnostic tool, pitted red cell counting remains an accurate, quantitative and inexpensive method[40]. Protein-conjugate vaccines should be recommended in patients with major hyposplenism, defined by a pitted red cell value higher than 10% and/or an IgM memory B cell frequency lower than 10%.

Pediatric CD may be followed using the same scheme as adults. However, bone densitometry and follow-up biopsy should only be performed in select cases. Children with good adherence to GFD and normal antibody levels, should be followed annually instead of every two years. The main reason for this shorter interval is the need for an early recognition of conditions associated to pediatric CD, and especially to ensure normal growth and development. The appearance of malignant complications associated to CD, as well as the development of refractory CD, is both exclusively associated to adult forms. Even when both situations are infrequent, they dictate a different follow-up from that performed for pediatric patients.

CONCLUSION

CD has many differences between children and adults. In adults, the presentation of the disease is less marked than during childhood. Clinicians must be aware of the less marked clinical profile in adults than children, such as atypical or minor symptoms, lower antibody titers and mild mucosal lesions (Table 3). Pediatric diagnostic criteria (ESPGHAN), cannot always be applied to adulthood. In fact, duodenal biopsy is necessary in most adult CD diagnosis, and during follow-up, to assess mucosal recovery and to detect complications.

Table 3.

Summary of key features associated with the presentation of celiac disease in adults

| High prevalence, even in advanced age |

| Oligosymptomatic presentation |

| Serology may have a low diagnostic yield |

| Duodenal biopsy usually shows mild atrophy or lymphocytic enteritis |

| Lymphocytic enteritis is a common presentation in adult celiac |

| The study of duodenal biopsy by an expert pathologist and the use of advanced techniques like flow cytometry may be useful for the diagnosis |

| Monitoring of the strict dietary compliance and the recovery of villous atrophy |

| The presence of associated complications should be identified at an early stage |

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 3, 2015

First decision: August 4, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

P- Reviewer: Bener A S- Editor: Ji FF

L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, Green PH, Hadjivassiliou M, Holdoway A, van Heel DA, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63:1210–1228. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang JY, Kang AH, Green A, Gwee KA, Ho KY. Systematic review: worldwide variation in the frequency of coeliac disease and changes over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:226–245. doi: 10.1111/apt.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaquero L, Caminero A, Nuñez A, Hernando M, Iglesias C, Casqueiro J, Vivas S. Coeliac disease screening in first-degree relatives on the basis of biopsy and genetic risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:263–267. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volta U, Caio G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R. The changing clinical profile of celiac disease: a 15-year experience (1998-2012) in an Italian referral center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:194. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0194-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1538–1544; quiz 1537, 1545. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mariné M, Farre C, Alsina M, Vilar P, Cortijo M, Salas A, Fernández-Bañares F, Rosinach M, Santaolalla R, Loras C, et al. The prevalence of coeliac disease is significantly higher in children compared with adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratesi R, Gandolfi L, Garcia SG, Modelli IC, Lopes de Almeida P, Bocca AL, Catassi C. Prevalence of coeliac disease: unexplained age-related variation in the same population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:747–750. doi: 10.1080/00365520310003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makharia GK, Verma AK, Amarchand R, Bhatnagar S, Das P, Goswami A, Bhatia V, Ahuja V, Datta Gupta S, Anand K. Prevalence of celiac disease in the northern part of India: a community based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:894–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West J, Logan RF, Hill PG, Lloyd A, Lewis S, Hubbard R, Reader R, Holmes GK, Khaw KT. Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut. 2003;52:960–965. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, Krekelä I, Patrikainen H, Valve R, Mäki M, Collin P. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong D, Don-Wauchope AC, Verdu EF. Testing for gluten-related disorders in clinical practice: the role of serology in managing the spectrum of gluten sensitivity. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:193–197. doi: 10.1155/2011/642452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vivas S, Ruiz de Morales JM, Fernandez M, Hernando M, Herrero B, Casqueiro J, Gutierrez S. Age-related clinical, serological, and histopathological features of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2360–2365; quiz 2366. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lionetti E, Catassi C. New clues in celiac disease epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Int Rev Immunol. 2011;30:219–231. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2011.602443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonaci-Nikolic B, Andrejevic S, Radlovic N, Davidovic I, Sofronic L, Spuran M, Micev M, Nikolic MM. Serological and clinical comparison of children and adults with anti-endomysial antibodies. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9062-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauret E, Rodrigo L. Celiac disease and autoimmune-associated conditions. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:127589. doi: 10.1155/2013/127589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickey W, Kearney N. Overweight in celiac disease: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and effect of a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2356–2359. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng J, Brar PS, Lee AR, Green PH. Body mass index in celiac disease: beneficial effect of a gluten-free diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:267–271. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181b7ed58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santolaria Piedrafita S, Fernández Bañares F. [Gluten-sensitive enteropathy and functional dyspepsia] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;35:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sainsbury A, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:359–365.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vivas S, Ruiz de Morales JG, Riestra S, Arias L, Fuentes D, Alvarez N, Calleja S, Hernando M, Herrero B, Casqueiro J, et al. Duodenal biopsy may be avoided when high transglutaminase antibody titers are present. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4775–4780. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease diagnosis: simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. Am J Med. 2010;123:691–693. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteve M, Rosinach M, Fernández-Bañares F, Farré C, Salas A, Alsina M, Vilar P, Abad-Lacruz A, Forné M, Mariné M, et al. Spectrum of gluten-sensitive enteropathy in first-degree relatives of patients with coeliac disease: clinical relevance of lymphocytic enteritis. Gut. 2006;55:1739–1745. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.095299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmi TT, Collin P, Reunala T, Mäki M, Kaukinen K. Diagnostic methods beyond conventional histology in coeliac disease diagnosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laparra MOM, Sanz Y. Microbiota intestinal y enfermedad celiaca. In: Rodrigo L y Peña AS., editor. Enfermedad celiaca y sensibilidad al gluten no celiaca. 213. Barcelona, España: Omnia Science; 2013. pp. 479–496. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collado MC, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M, Sanz Y. Specific duodenal and faecal bacterial groups associated with paediatric coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:264–269. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.061366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nistal E, Caminero A, Herrán AR, Arias L, Vivas S, de Morales JM, Calleja S, de Miera LE, Arroyo P, Casqueiro J. Differences of small intestinal bacteria populations in adults and children with/without celiac disease: effect of age, gluten diet, and disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:649–656. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nistal E, Caminero A, Vivas S, Ruiz de Morales JM, Sáenz de Miera LE, Rodríguez-Aparicio LB, Casqueiro J. Differences in faecal bacteria populations and faecal bacteria metabolism in healthy adults and celiac disease patients. Biochimie. 2012;94:1724–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leon F. Flow cytometry of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in celiac disease. J Immunol Methods. 2011;363:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calleja S, Vivas S, Santiuste M, Arias L, Hernando M, Nistal E, Casqueiro J, Ruiz de Morales JG. Dynamics of non-conventional intraepithelial lymphocytes-NK, NKT, and γδ T-in celiac disease: relationship with age, diet, and histopathology. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2042–2049. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Camarero C, Leon F, Sanchez L, Asensio A, Roy G. Age-related variation of intraepithelial lymphocytes subsets in normal human duodenal mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:685–691. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio-Tapia A, Rahim MW, See JA, Lahr BD, Wu TT, Murray JA. Mucosal recovery and mortality in adults with celiac disease after treatment with a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1412–1420. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahab PJ, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Histologic follow-up of people with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet: slow and incomplete recovery. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:459–463. doi: 10.1309/EVXT-851X-WHLC-RLX9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elfström P, Granath F, Ekström Smedby K, Montgomery SM, Askling J, Ekbom A, Ludvigsson JF. Risk of lymphoproliferative malignancy in relation to small intestinal histopathology among patients with celiac disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:436–444. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebwohl B, Granath F, Ekbom A, Smedby KE, Murray JA, Neugut AI, Green PH, Ludvigsson JF. Mucosal healing and risk for lymphoproliferative malignancy in celiac disease: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:169–175. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis NR, Scott BB. Should patients with coeliac disease have their bone mineral density measured. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1065–1070. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West J, Logan RF, Card TR, Smith C, Hubbard R. Fracture risk in people with celiac disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:429–436. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00891-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribes-Koninckx C, Mearin ML, Korponay-Szabó IR, Shamir R, Husby S, Ventura A, Branski D, Catassi C, Koletzko S, Mäki M, et al. Coeliac disease diagnosis: ESPGHAN 1990 criteria or need for a change Results of a questionnaire. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:15–19. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31822a00bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas HJ, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Ahmad T, Jewell DP, Goldacre MJ. Pneumococcal infection in patients with coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:624–628. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f45764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Sabatino A, Brunetti L, Carnevale Maffè G, Giuffrida P, Corazza GR. Is it worth investigating splenic function in patients with celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2313–2318. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i15.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]