Abstract

Introduction

Information detailing the experience of patients with light chain (AL) amyloidosis is lacking. The primary aim of this study was to gather data on the patient experience to understand the challenges in diagnosis and to gain insight into barriers to accessing appropriate care.

Methods

Patients with amyloidosis, family members, and caregivers were invited to participate in an online 16-question survey (available from January 29 to February 5, 2015). Participants with AL amyloidosis were sent an eight-question follow-up survey.

Results

The initial survey was completed by 533 participants (follow-up survey completed by 201 participants). AL amyloidosis was the most common diagnosis. For 37.1% of respondents, the diagnosis of amyloidosis was not established until ≥1 year after the onset of initial symptoms. Diagnosis was received after visits to 1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥5 physicians by 7.6%, 23.5%, 20.3%, 16.8%, and 31.8% of respondents, respectively. Correct diagnosis was most often made by hematologists/oncologists (34.1%). Treatments included chemotherapy (63.1%) and stem cell transplantation (38.9%) and were difficult to tolerate for 54.1% of respondents. A significant number of respondents felt uninformed about clinical trials. Nevertheless, approximately half (46.1%) believed that enrolling in a trial would enhance their care.

Conclusions

Establishing a diagnosis of amyloidosis is difficult. Current treatments are difficult to tolerate and do not substantially improve quality of life for most patients. There is an urgent need for well-tolerated therapies with clear treatment benefit. Patient awareness of clinical trials can be improved, especially given that respondents indicated high willingness to participate.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-015-0250-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Disease awareness, Early diagnosis, Patient survey, Systemic amyloidosis, Treatment

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder characterized by abnormal, misfolded proteins that accumulate in various organs, causing progressive organ damage [1, 2]. There are several types of systemic amyloidoses; light chain (AL) amyloidosis (Orpha number: ORPHA85443) represents the most common type [3]. The estimated incidence of AL amyloidosis is 8–12 persons per million per year [4–6]. In addition, an estimated 10–15% of cases occur in association with multiple myeloma. Based on the incidence data, it is estimated that there are 30,000 to 45,000 patients living with AL amyloidosis in the United States and the European Union.

Clinical presentation of AL amyloidosis can vary widely and depends on the extent and number of organs affected. Initial symptoms at onset are often nonspecific (e.g., weight loss, fatigue). As the disease progresses, symptoms reflect the organs involved, most commonly the heart and the kidneys [5]. The goal of treatment for patients with AL amyloidosis should be to preserve and improve organ function with a well-tolerated and effective disease-modifying therapy. Despite recent advances in AL amyloidosis diagnostic tools and treatment, the early mortality rate remains high; the 1-year mortality rate is approximately 30%. Unfortunately, by the time a diagnosis is made and treatment is initiated, the disease has often become advanced [4, 5].

In the absence of approved therapies for AL amyloidosis, physicians use off-label multiple myeloma therapies that target the abnormal plasma cells responsible for the production of the light chain precursor proteins without consideration for the underlying organ dysfunction in the patient [5, 7, 8]. Thus, these treatments can be associated with significant adverse events, and patients often die before experiencing benefit from them [5]. A substantial need remains for well-tolerated and effective therapies that specifically target the underlying cause of the disease: the misfolded light chain proteins.

Despite the significant effects of AL amyloidosis on patient quality of life, data describing them are lacking. Detailing the patient experience may identify ways to improve patient care and disease outcomes. The primary aim of this study was to gather data on the patient experience to elucidate the challenges in establishing a diagnosis of AL amyloidosis and to gain insight into barriers to accessing appropriate care.

Methods

Patients with amyloidosis, their family members, and their caregivers were invited to participate in an anonymous online survey through email and via the social media channels of the Amyloidosis Foundation (www.amyloidosis.org), the foundation’s Facebook page (www.facebook.com/AmyloidosisFoundation), and an amyloidosis awareness group on Facebook (www.facebook.com/groups/amyloidosisawareness). The initial 16-question survey was developed by the authors and was available online to participants from January 29 to February 5, 2015. After the initial survey was completed, participants with AL amyloidosis who provided contact information were sent an eight-question follow-up survey by email.

The initial survey covered demographic information, type of amyloidosis, symptoms, organ involvement, diagnosis, amyloidosis education, and clinical trial awareness. It was expected that a high proportion of respondents to the initial survey would be patients with AL amyloidosis; therefore, the follow-up survey focused on AL amyloidosis and consisted of eight questions covering amyloidosis treatments, treatment tolerance, and quality of life before and after treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Data were evaluated using descriptive statistics (Microsoft Excel 2013, Redmond, Washington).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain information on any new studies in human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients as a condition of their inclusion in the study.

Results

Participants

The initial survey was completed by 533 participants; 57.8% identified themselves as patients, 33.8% identified themselves as family members, and 8.3% identified themselves as caregivers taking the survey on behalf of patients (Table 1). The follow-up survey was completed by 201 participants. Most respondents were female (62.2%) and were between 50 and 69 years of age (62.7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents

| Respondents | |

|---|---|

| Type of participant, n (%), n = 515 | |

| Patient | 298 (57.8) |

| Family member | 174 (33.8) |

| Caregiver | 43 (8.3) |

| Sex, n (%), n = 519 | |

| Female | 323 (62.2) |

| Male | 196 (37.8) |

| Age group, n (%), n = 524 | |

| 25–34 years | 23 (4.4) |

| 35–44 years | 59 (11.3) |

| 45–54 years | 96 (18.3) |

| 55–64 years | 190 (36.3) |

| 65–74 years | 120 (22.9) |

| 75 years or older | 36 (6.9) |

| Median age at diagnosis, years (range) | 57 (20–83) |

| Type of amyloidosis, n (%), n = 484 | |

| AL amyloidosis | 347 (71.7) |

| AA amyloidosis | 23 (4.8) |

| Hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis | 35 (7.2) |

| Hereditary non–transthyretin-related amyloidosis | 6 (1.2) |

| Other | 25 (5.2) |

| Unknown | 48 (9.9) |

| Organ involvement, n (%), n = 469 | |

| Heart | 172 (36.7) |

| Kidneys | 132 (28.1) |

| Liver | 15 (3.2) |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 27 (5.8) |

| Nervous system | 26 (5.5) |

| Multiple | 97 (20.7) |

Please note that not all participants responded to all questions. 533 participants completed the survey, but the numbers in the table indicate those who answered each particular survey question

AA inflammatory, AL light chain

Diagnosis of Amyloidosis

Median age at diagnosis was 57 years (range 20–83 years). AL amyloidosis, reported by 71.7% of respondents (Table 1), was the most common diagnosis. The other types of amyloidosis were AA amyloidosis (4.8%), hereditary transthyretin-related amyloidosis (7.2%), hereditary non–transthyretin-related amyloidosis (1.2%), other (5.2%), and unknown (9.9%).

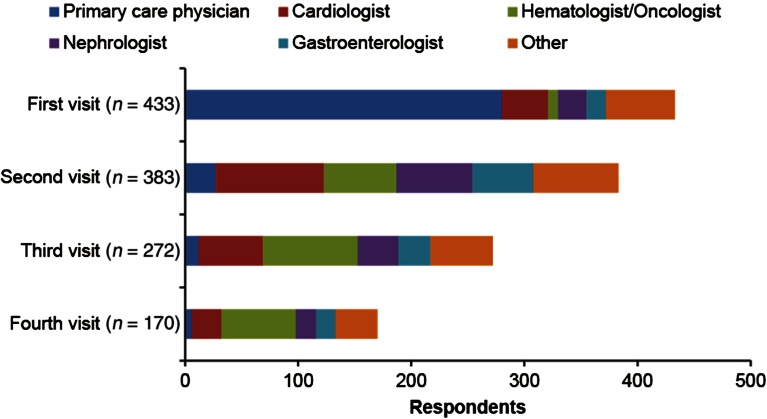

Most respondents (63.0%) reported that they received a diagnosis of amyloidosis within 1 year of initial symptoms, whereas 37.1% of respondents reported that diagnosis was delayed for ≥1 year (Table 2). A substantial proportion of respondents (31.8%) reported visiting ≥5 different physicians before receiving the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and only 7.6% received the diagnosis after visiting one physician (Table 2). The first doctor seen was usually a primary care physician (64.9%). Respondents were then often referred for a second visit to a cardiologist (24.5%), hematologist/oncologist (16.5%), nephrologist (18.1%), or gastroenterologist (14.6%) (Fig. 1). Cardiologists, hematologists/oncologists, and nephrologists had the most opportunities to diagnose amyloidosis for respondents referred to their specialties. Respondents also visited other specialists, including internists, neurologists, hepatologists, ophthalmologists, and dermatologists.

Table 2.

Establishment of amyloidosis diagnosis

| Respondents | |

|---|---|

| Time from initial symptoms to diagnosis of amyloidosis, n (%), n = 459 | |

| <6 months | 171 (37.3) |

| 6–12 months | 118 (25.7) |

| 12–18 months | 44 (9.6) |

| 18–24 months | 34 (7.4) |

| 2–3 years | 44 (9.6) |

| >3 years | 48 (10.5) |

| Different physicians visited before establishment of a diagnosis, n (%), n = 459 | |

| 1 | 35 (7.6) |

| 2 | 108 (23.5) |

| 3 | 93 (20.3) |

| 4 | 77 (16.8) |

| ≥5 | 146 (31.8) |

| Specialty of diagnosing physician, n (%), n = 402 | |

| Hematologist/oncologist | 137 (34.1) |

| Nephrologist | 91 (22.6) |

| Cardiologist | 75 (18.7) |

| Gastroenterologist | 32 (8.0) |

| Neurologist | 19 (4.7) |

| Primary care physician | 16 (4.0) |

| Othera | 32 (8.0) |

aIncludes internists, hepatologists, ophthalmologists, and dermatologists

Fig. 1.

Types of physicians visited before diagnosis of amyloidosis

Respondents saw cardiologists more frequently than hematologists/oncologists and nephrologists, though cardiologists did not typically diagnose the condition. Respondents usually received the correct diagnosis from a hematologist/oncologist (34.1%). Nephrologists and cardiologists provided the correct diagnosis for 22.6% and 18.7% of respondents, respectively (Table 2).

Sixty-three percent of respondents had been evaluated at an amyloidosis center (452 total responses), although only 43.7% received treatment at an amyloidosis center (444 total responses).

Amyloidosis Symptoms and Organ Involvement

The most common initial symptoms were fatigue, shortness of breath, weakness, neuropathy, and swelling of the legs and/or tongue. Most respondents reported the heart (36.7%) or the kidneys (28.1%) as the major organ affected, with involvement of the gastrointestinal tract (5.8%), nervous system (5.5%) or liver (3.2%) reported less frequently (Table 1). Multiple organ involvement was reported by 20.7% of respondents.

AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis and Treatment

Among the participants with AL amyloidosis who completed the follow-up survey, 39.2% reported low quality of life before diagnosis, 31.2% reported average quality of life, and 29.7% reported great quality of life (199 total responses). When asked how the diagnosis of amyloidosis made the patient feel, 63.0% reported feeling frightened, 31.0% depressed, 30.5% numb, 28.5% powerless, 25.5% hopeless, 18.5% relieved, and 18.0% angry (200 total responses).

For patients with AL amyloidosis who responded to the follow-up survey, treatment consisted of chemotherapy in 63.1% of respondents, stem cell transplantation in 38.9%, and solid organ transplantation in 7.6%. When asked how well treatment was tolerated, 54.1% reported that it was somewhat or very difficult, 20.4% reported neither easy nor difficult, and 25.4% reported somewhat easy (181 total responses). However, patients receiving stem cell transplantation found treatment to be much less tolerable than patients receiving other types of treatment (Table 3). Quality of life in patients receiving any of these treatments was greatly improved with treatment for 28.8% of respondents, somewhat improved for 39.1%, and not improved at all for 32.1% (184 total responses). In particular, patients receiving stem cell transplantation rated their quality of life as having improved more substantially than patients receiving other treatments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tolerability and quality of life associated with stem cell transplantation compared with other treatments

| Stem cell transplantation (n = 77) | Other treatments (n = 124) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tolerability, n (%) | n = 75 | n = 105 |

| Very difficult | 20 (26.7) | 13 (12.4) |

| Somewhat difficult | 28 (37.3) | 37 (35.2) |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 14 (18.7) | 22 (21.0) |

| Somewhat easy | 13 (17.3) | 33 (31.4) |

| Quality of life, n (%) | n = 76 | n = 108 |

| Greatly improved | 28 (36.8) | 25 (23.1) |

| Somewhat improved | 26 (34.2) | 46 (42.6) |

| No improvement | 22 (28.9) | 37 (34.3) |

Amyloidosis Education

Of the 427 respondents who answered a question pertaining to information or educational material received at the time of diagnosis about their specific amyloidosis type, 39.3% received the center’s own printed handouts, 34.4% received another organization’s disease or treatment literature, 29.3% received information on support groups, 23.7% received clinical trial information, and 40.0% reported receiving no information or educational material.

Clinical Trial Awareness

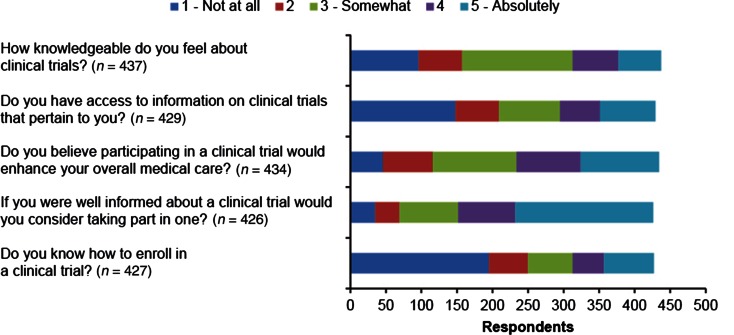

In the initial survey, participants were asked to score their answers regarding clinical trial knowledge and access on a scale of 1 to 5, from “Not at all” (score 1) to “Absolutely” (score 5) (Fig. 2). A significant number of respondents felt uninformed about clinical trials; 71.6% indicated a score of ≤3 regarding how knowledgeable they were about clinical trials. Most respondents also felt that they did not have access to pertinent clinical trial information; 68.8% indicated a score of ≤3 regarding access to clinical trial information. Nevertheless, almost half (46.1%) said they believed that a clinical trial would enhance their medical care (score of ≥4), and 45.5% reported that they would absolutely consider enrolling in a clinical trial if they were well informed. Forty-six percent of respondents also reported that they did not know how to enroll in a clinical trial. In the follow-up survey, 19.5% of respondents reported that they had participated in a clinical trial (190 total responses).

Fig. 2.

Clinical trial awareness and interest

Discussion

Despite the challenges facing health care professionals in diagnosing AL amyloidosis, the lack of available therapeutic options that are effective and well tolerated, and the subsequent impact on the patients involved, no published information describes the patient experience. This article represents the first such description of the patient journey and the challenges faced.

Establishing an early and accurate diagnosis of amyloidosis is a challenge for patients. These data demonstrate that most patients require multiple physician visits to different medical specialists, often spanning >1 year. Consistent with the literature [5, 9, 10], most respondents experience heart or kidney involvement.

Because of the high incidence of cardiac symptoms (including shortness of breath) associated with AL amyloidosis, primary care physicians often refer their patients to cardiologists. There is an opportunity and an urgent need for all physicians, particularly cardiologists, to diagnose amyloidosis earlier, before the disease progresses to more advanced stages. These data suggest that physicians in all medical specialties have difficulty in establishing a diagnosis of AL amyloidosis. Interestingly, although AL amyloidosis is typically considered to be a disease of the elderly (older than 60 years of age), the median age of respondents in our survey was 57 years, with 34.0% younger than 55 years of age and 15.6% younger than 45 years of age. Despite a selection bias inherent in a web-based survey that may skew to younger persons, younger patients are also probably significantly underdiagnosed.

Considering that 54% of respondents had difficulty in tolerating treatment and only 30% of respondents reported a definite improvement in quality of life, there is a need for therapies clearly associated with treatment benefit. On the other hand, benefits from therapy are more likely to occur in early stages of the disease, making early diagnosis essential for improving outcomes for patients with systemic amyloidosis [11]. Efforts to increase physician awareness of the signs and symptoms and the appropriate evaluation of AL amyloidosis have the potential to improve patient outcomes.

Survey responses indicate that patient awareness of clinical trials and patient education about the disease can be considerably improved, especially because respondents indicated a high willingness to participate in clinical trials. Patient care can be enhanced through education and information to help patients feel empowered and knowledgeable about their diagnosis and treatment plan and through increased access to support groups and relevant clinical trials.

We acknowledge the limitations in controlling the quality of information gathered through a web-based questionnaire. Of note, there is a selection bias inherent to a web-based survey that includes a younger audience of patients and/or younger persons involved in their care. However, we show that this younger population, which likely represents the most knowledgeable segment of patients and which has the best access to Internet resources, is not very well informed. Additionally, there may be a bias with respect to sex given that several studies have shown that men have a higher incidence of most forms of amyloidosis, whereas our respondents were primarily women (62%). Web-based surveys also do not control for the quality of care patients are receiving; as such, it is not known whether the respondents represent patients with better or worse (or equivalent) care than the average amyloidosis patient. Nevertheless, this patient-centered initiative provides important insights into the AL amyloidosis patient experience from the time of diagnosis through treatment of the disease.

Conclusions

This study highlights the value of and the need for data on patient experience and quality of life that can be reported in future studies as part of patient-centered initiatives. Data from this study and other studies can help to identify areas in which diagnosis is delayed or missed and can illustrate the need for early, accurate diagnosis of amyloidosis to help improve disease management and survival outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by Amyloidosis Research Consortium. We thank David Gibson, PhD, CMPP, of ApotheCom (San Francisco, CA), who provided medical writing services on behalf of the Amyloidosis Research Consortium. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures.

Isabelle Lousada has received speaker fees from Pfizer. Raymond L. Comenzo has received consulting fees or honoraria from Takeda Millennium, Karyopharm, and Janssen and has received research support from Takeda Millennium, Prothena, Janssen, and Teva. Heather Landau has received honoraria from Takeda; consulting or advisory fees from Onyx, Spectrum, Takeda, Prothena; and research support from Onyx.

Spencer Guthrie is an employee of and owns stock in Prothena Biosciences Inc.

Giampaolo Merlini has received honoraria from Millennium-Takeda and Pfizer, consulting fees from Janssen, speaker fees from Pfizer, and travel expenses from Janssen and Pfizer.

Compliance with ethics guidelines.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients as a condition of their inclusion in the study.

References

- 1.Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchorawala V. Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1331–1341. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02740806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merlini G, Comenzo RL, Seldin DC, Wechalekar A, Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Exp Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;7:143–156. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2014.858594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comenzo RL, Reece D, Palladini G, Seldin D, Sanchorawala V, Landau H, et al. Consensus guidelines for the conduct and reporting of clinical trials in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Leukemia. 2012;26:2317–2325. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merlini G, Wechalekar AD, Palladini G. Systemic light chain amyloidosis: an update for treating physicians. Blood. 2013;121:5124–5130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-453001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyle RA, Linos A, Beard CM, Linke RP, Gertz MA, O’Fallon WM, et al. Incidence and natural history of primary systemic amyloidosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950 through 1989. Blood. 1991;79:1817–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. (2015) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: systemic light chain amyloidosis. Version 1. 2015. https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/amyloidosis.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Wechalekar AD, Gillmore JD, Bird J, Cavenagh J, Hawkins S, Kazmi M, et al. Guidelines on the management of AL amyloidosis. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:186–206. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, Fermand JP, Hazenberg BP, Hawkins PN, et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Tours, France, 18–22 April 2004. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:319–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palladini G, Hegenbart U, Milani P, Kimmich C, Foli A, Ho AD, et al. A staging system for renal outcome and early markers of renal response to chemotherapy in AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2014;124:2325–2332. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-570010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2014 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:1132–1140. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.