Summary

New cervical cancer screening guidelines in the US and many European countries recommend that women get tested for human papillomavirus (HPV). To inform decisions about screening intervals, we calculate the increase in precancer/cancer risk per year of continued HPV infection. However, both time to onset of precancer/cancer and time to HPV clearance are interval-censored, and onset of precancer/cancer strongly informatively censors HPV clearance. We analyze this bivariate informatively interval-censored data by developing a novel joint model for time to clearance of HPV and time to precancer/cancer using shared random-effects, where the estimated mean duration of each woman’s HPV infection is a covariate in the submodel for time to precancer/cancer. The model was fit to data on 9,553 HPV-positive/Pap-negative women undergoing cervical cancer screening at Kaiser Permanente Northern California, data that were pivotal to the development of US screening guidelines. We compare the implications for screening intervals of this joint model to those from population-average marginal models of precancer/cancer risk. In particular, after 2 years the marginal population-average precancer/cancer risk was 5%, suggesting a 2-year interval to control population-average risk at 5%. In contrast, the joint model reveals that almost all women exceeding 5% individual risk in 2 years also exceeded 5% in 1 year, suggesting that a 1-year interval is better to control individual risk at 5%. The example suggests that sophisticated risk models capable of predicting individual risk may have different implications than population-average risk models that are currently used for informing medical guideline development.

Keywords: HPV, cancer screening, medical guidelines, risk modeling, joint modeling of longitudinal, survival data

1. Introduction

New cervical cancer screening guidelines, both in the US (Massad et al., 2013) and soon to be adopted in many European countries (Leeson et al., 2013), recommend that women get tested for human papillomavirus (HPV), the necessary cause of cervical cancer. However, most women who test HPV-positive will have no evidence of premalignant cells, that is, they also have a negative Pap test; in the US, millions of women each year are expected to test HPV-positive/Pap-negative (Katki et al., 2013b). Because most HPV infections will naturally clear in women without intervention, leaving them at low cancer risk, immediate referral to colposcopy to obtain biopsies is generally considered to be too aggressive (Cuzick et al., 2008).

Thus a critical question for HPV-based screening programs is how soon HPV-positive/Pap-negative women ought to be asked to return for rescreening. Answering this question requires us to calculate, for each possible screening interval, both (1) the chance of developing precancer or cancer, and (2) the chance that the HPV infection will persist. The chance that the HPV infection will persist is equivalent to the fraction of women who will be referred for biopsies because any woman with persistent HPV infection will be asked to undergo colposcopy: the shorter the screening interval, the lower the precancer/cancer risk but the more HPV persistence, and the more women who will be referred for colposcopy. Consequently, calculating both precancer/cancer risk and HPV persistence risk allows screening guidelines committees to trade off precancer/cancer risk with the number of invasive procedures required.

Although precancer/cancer risk and HPV persistence risk have been calculated marginally (Katki et al., 2013b), there may be advantages to calculating them jointly. It is widely accepted that the necessary causal factor for development of cervical cancer is the duration of the HPV infection: the longer an HPV infection persists, the hazard of precancer/cancer concomitantly increases (Schiffman et al., 2007; Rodriguez et al., 2010). However, we are unaware of any published estimate of the increase in risk of precancer or cancer per year of persistence of HPV infection. A naive method for calculating this risk would be to regress precancer/cancer risk on the observed time of clearance of HPV. However, almost all precancers/cancers remain HPV-positive at time of diagnosis and so no naive estimate of HPV duration is possible to plug-in for them. Furthermore, treatment of precancers/cancer informatively censors the duration of HPV infection because the women who develop precancer/cancer are those who are likely to have the longest duration of HPV infection. HPV test results cannot be analyzed naively as a time-dependent covariate because HPV is an endogenous covariate, and regardless, this approach ignores the scientific problem that we want to consider the true time of HPV clearance. Our problem is not a time-to-first-event competing risks problem because neither event time necessarily censors the other. Treating the event times as competing risks does not address the main scientific question of the relationship of informatively censored true HPV clearance (not merely testing HPV-negative) on time to precancer/cancer.

Moreover, an important feature of data from screening programs is that while the time of diagnosis of disease (or a negative HPV test result) is generally known, the time of onset of disease (or clearance of HPV) is only interval censored. Accounting for interval censoring is particularly important for considering alternate hypothetical screening intervals because time of diagnosis is always later than time of onset. Approximating that the time of onset with the time of diagnosis necessarily implies that the time of onset could not be earlier, and thus any shorter screening interval would misleadingly appear to ’miss’ the disease.

We develop a joint model of time to precancer/cancer and HPV duration that directly estimates the hazard of precancer/cancer as a regression function of HPV duration. In our regression framework, we regress the hazard of developing precancer/cancer on a model-based estimate of the mean duration of each woman’s HPV infection. We are not aware of any general method for the analysis of censored bivariate survival data that uses the mean failure time, but the advantage of this natural approach is that it yields the desired interpretation: the hazard ratio is the increased risk of precancer/cancer per extra year of HPV duration. We assume marginal Weibull models for time to precancer/cancer and time to HPV clearance. Parametric models can be robust and more informative than non/semi-parametric methods when data is interval censored (Lindsey, 1998), and in particular, a Weibull model for time to precancer/cancer is suggested by the multistage model of carcinogenesis (Armitage and Doll, 1954). We adopt a shared parameter approach (Wu and Carroll, 1988), akin to that often used in joint analysis of longitudinal and survival data (Rizopoulos, 2012), where a failure-time process is represented as a regression function of a mean and random effects. Our approach handles informative interval-censoring, estimates woman-specific risks of precancer/cancer and of HPV persistence, and we provide our SAS code for fitting it. We fit our model to data from the cervical cancer screening program at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), which is the largest and longest experience with widescale HPV testing in routine clinical practice to date (Katki et al., 2011) and which were pivotal to the development of the new US screening and management guidelines (Massad et al., 2013).

We contrast the potential implications for screening intervals from individual conditional risks estimated from this joint model versus the usual marginal population-average regression model of precancer/cancer risk typically used for so-called ”individual risk prediction”. All risk-based medical guidelines we are aware of attempt to control population-average risk among people with certain covariates, such as the new US cervical screening guidelines (Katki et al., 2013a) or guidelines for prescription of statins to prevent cardiovascular disease (Stone et al., 2013). However, individual patients are naturally interested in controlling their individual risk. Individual risk can only be calculated from conditional models requiring assumptions about the distribution of risk in a population (Diggle et al., 1994). This is much more difficult calculation, typically involving latent classes or random-effects, and we are aware of no risk-based medical guidelines based on individual risk. Because making predictions about individual disease risk using complex longitudinal covariates is a burgeoning area of statistical research (Rizopoulos, 2011; Sweeting and Thompson, 2011, 2012, e.g.), it is important to consider the potential differences in implications for guidelines based on population-average risk versus individual risk.

2. KPNC cervical screening program data

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large health-maintenance organization that adopted HPV testing for all women age 30 and older in 2003. We have previously reported on risks involving all 331,818 women who enrolled for HPV-based screening in 2003–2005 (Katki et al., 2011). In this paper, we focus on the 9553 women age 30 and older who tested HPV-positive/Pap-negative upon their entry into the screening program and for whom we have at least one follow-up visit. We exclude the very few women who, against KPNC screening guidelines, were referred for colposcopy immediately after their entry visit. Of these women, 6886 (72%) had their HPV infection observed to clear (defined as a single HPV-negative test result at some time during follow-up) and 668 (7.0%) developed cervical precancer or cancer during follow-up. Women who developed cervical precancer or cancer (defined as Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade 2 or worse (CIN2+), or ”precancer/cancer”) were referred for excisional treatments. For those whose HPV cleared and are thus interval-censored, we defined the right endpoint of the intervals as being the time of the first observed HPV-negative, and the left endpoint the previous time at which they were HPV-positive. For those who developed precancer/cancer at a biopsy visit and are thus interval-censored, the right endpoint of the intervals was the time of the diagnosis of precancer/cancer, and the left endpoint was the screening visit prior to the current one that referred her to a biopsy. Otherwise, the time of HPV clearance or time of precancer/cancer were right-censored at the last observation time.

KPNC screening guidelines recommended that no women testing HPV-positive/Pap-negative be immediately referred for colposcopy, but instead to return in one year. If at that return visit in one year, she retested HPV-positive/Pap-negative, or if she had an abnormal Pap test, she was referred for colposcopy. If she tested HPV-negative/Pap-negative, she was asked to return in three years. Although most women returned in approximately 1–2 years (IQR for return time: 366–695 days), many women returned later and some women returned sooner.

3. Joint model of HPV duration and time to cervical precancer/cancer

HPV duration is right censored if the infection is never observed to clear, else is interval censored between the consecutive visits where the HPV test was last positive but is currently negative. We fit the standard Weibull hazard regression model as the hazard of clearing an HPV infection for each woman i using accelerated failure-time (AFT) location-scale parameterization

| (1) |

The location coefficients β = (β0, β1, β2) correspond to covariates X = (X0, X1, X2) where X0 = 1 (thus β0 is the intercept), X1 is the woman’s age at entry, and X2 is the square of age. We do not allow the scale parameter τ to vary with covariates, but this extension could be readily accomodated. The woman-specific random-effect frailty ωi is normally distributed ωi ~ N(0, σ2). The latent frailty ωi attempts to account for the unmeasured differences in the abilities of different women to clear HPV infection that have long been hypothesized to explain the wide heterogeneity in time of clearance of HPV infections (Rodriguez et al., 2008).

The key quantity to compute from the model (1) is the model-based woman-specific expected duration of HPV infection

| (2) |

where Γ(·) is the complete Gamma function. This woman-specific estimate of her mean HPV duration (which is not directly observable) will be plugged into the next Weibull model for time to cervical precancer/cancer.

Time to cervical precancer/cancer is right censored if precancer/cancer never occurs, else is interval censored between the consecutive visits where precancer/cancer was not diagnosed and where it was diagnosed. We fit a second Weibull hazard regression model for each woman i on her time to precancer/cancer ui

| (3) |

The notation ”CIN” (Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia) indicates that this is a hazard for precancer/cancer (defined as CIN2+). The function f(di) is a prespecified function of the woman-specific mean HPV duration di; we will consider the identity and the logarithm. This model uses the same covariates Xi as in model (1), but in general the covariates could be different. The key is that the model also regresses on a prespecified function of each woman’s estimated mean duration of HPV di, whose coefficient δ describes how precancer/cancer risk increases per year of HPV infection. The two models (1) and (3) are linked through di which is a function of the random effect ωi.

The full likelihood is a shared-parameter likelihood integrating out the latent random effect ωi for each woman

| (4) |

where Φ(·;·) is the CDF of a normal distribution with given parameters. The notation HPVi denotes a likelihood contribution from the model for HPV duration (1) and CINi a likelihood contribution from the model for time to cervical precancer/cancer (3). The standard assumption in shared parameter likelihoods is that the two contributions HPVi and CINi are independent given the shared parameters as funnelled through di, in particular, ωi. The HPVi and CINi are standard survival likelihoods for interval-censored and right-censored data:

| (5) |

| (6) |

The interval censoring is marked by the time interval (Li, Ri)): those who have their HPV infection clear are denoted ”HPV−”; those who develop precancer/cancer are denoted ”CIN2+”. Right censoring is marked by the time interval (Li, ∞): those who are right-censored for HPV duration are those who remain HPV-positive (denoted ”HPV+”); those who are right-censored for precancer/cancer are denoted ”< CIN2”) . The survival functions have closed forms from the Weibull distribution:

| (7) |

| (8) |

Because identifiability of models with random-effects cannot be presumed, Appendix 1 demonstrates that the random-effects parameters (σ, δ) in the likelihood (4) are indeed identifiable.

By jointly modeling both processes, we implicitly account for informative censoring of HPV duration by occurrence of cervical precancer/cancer. This is because the hazard for HPV clearance (1) is a function of the hazard of precancer/cancer (3) via the shared parameter, the mean HPV duration Di (2). To be explicit, for the model f(di) = log(di), the hazard of HPV duration is a function of the mean HPV duration

and the mean duration Di is a function of the precancer/cancer hazard

Consequently the hazard of HPV clearance is a function of the hazard of precancer/cancer.

The likelihood (4) has no closed-form expression and thus cannot be exactly evaluated. Fortunately, the likelihood can be approximated with adaptive Gaussian quadrature and then maximized in SAS PROC NLMIXED (Wolfinger, 1999; Bellamy et al., 2004). In our experience, the maximization is tricky and requires good starting values. We describe a 5-step procedure for fitting this model in Appendix 2.

4. Joint analysis of time to precancer/cancer and HPV duration in the KPNC screening program

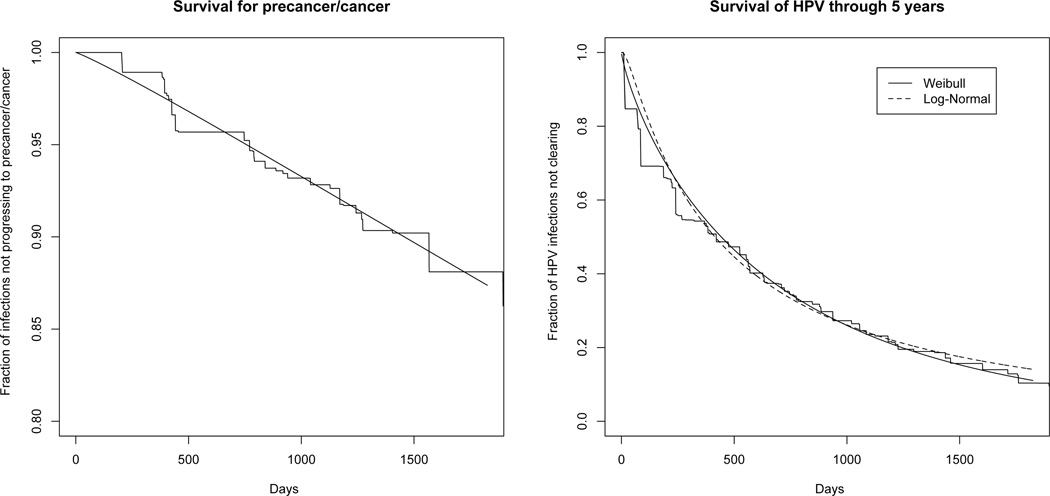

As suggested by the multistage model of carcinogenesis (Armitage and Doll, 1954), the Weibull distribution was a good fit for marginal time to cervical precancer/cancer estimated from a nonparametric estimate (Turnbull, 1976) (Figure 1, left graph). We then checked the fit of the Weibull model to marginal HPV duration. Figure 1 (right graph) compares a nonparametric estimate for the survival of HPV infections over time (ie time to clearance of HPV infections) to fits from Weibull and lognormal models. Although the two models fit the nonparametric estimate equally closely, the lognormal appears to fit the data better than the Weibull by the AIC (19786 vs. 19825). We then fit each model with a normally distributed frailty on the log-hazard. For the Weibull model with frailty (this is equation (1) but without covariates X1 and X2), the frailty variance was 1.09 and the AIC decreased to 19781. The lognormal model with frailty estimated a variance of 0.63, but it was very imprecisely estimated and the AIC increased to 19788. Because we plan to use frailties in our joint model, we felt justified to use a Weibull model with frailty to fit to HPV duration.

Fig. 1.

Fit of Weibull model to time to cervical precancer/cancer (left graph) and fit of Weibull and lognormal models to HPV duration (right graph). X-axes are time in days since 1st screening visit.

We fit two versions of the joint model, one where we parameterized the effect of each woman’s mean HPV duration di on precancer/cancer in model (3) as f(di) = di (a linear parameterization), and one where f(di) = log(di) (a log parameterization). For the linear model 1, the constant hazard ratio for cervical precancer/cancer per year of HPV duration is exp(−δ/κ). For the log model 2, the between-woman hazard ratio for cervical precancer/cancer comparing two HPV infections of duration d0 and d1 is

For example, if one HPV infection persists twice as long as the other, the hazard ratio for increase in precancer/cancer risk from the longer-lasting HPV infection is 2−δ/κ.

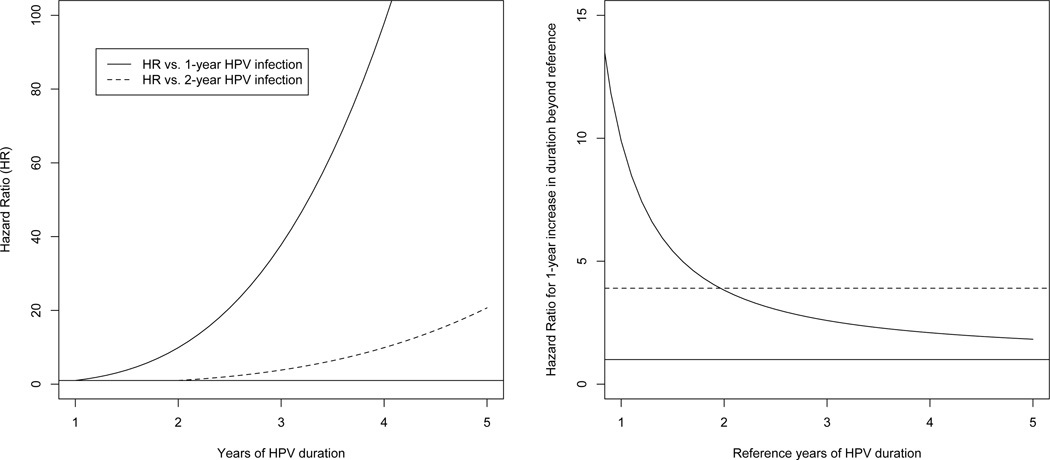

Table 1 shows the parameter estimates from the two models. The deviance and AIC for the log(duration) model is much smaller than for the linear duration model, suggesting that the hazard is better modelled using a relative change in HPV duration rather than an absolute one. In particular, the hazard ratio (HR) for cervical precancer/cancer from a d-year HPV infection versus a 1-year HPV infection is d1.7/0.52 = d3.3, which increases quickly with HPV duration. The left graph of Figure 2 shows this roughly cubic increase with years of HPV duration. The HRs are lower when comparing to longer-term (two-year) HPV infections (dashed curve, left graph, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Estimates (standard errors) from the KPNC data. Covariate coefficients are in AFT parameterization (i.e. positive coefficients imply decreased risk).

| submodel | effect | linear HPV duration model | log(HPV duration) model |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV duration submodel |

Intercept (β0) | 6.63 (0.033) | 6.58 (0.036) |

| baseline age (β1) | −0.224 (0.046) | −0.24 (0.048) | |

| baseline age2 (β2) | 0.064 (0.013) | 0.070 (0.013) | |

| scale (τ) | 0.79 (0.023) | 0.68 (0.033) | |

| frailty SD (σ) | 1.065(0.029) | 1.21 (0.035) | |

| precancer/ cancer submodel |

Intercept (α0) | 9.10 (0.13) | 21.28 (0.81) |

| baseline age (α1) | −0.0042 (0.11) | 0.015 (0.12) | |

| baseline age2 (α2) | 0.054 (0.032) | 0.063 (0.033) | |

| scale (κ) | 0.19 (0.017) | 0.52 (0.040) | |

| duration (δ) | −0.25 (0.021) | −1.7 (0.10) | |

| HR: HPV lasts 2 vs. 1 years | 3.9 (0.51) | 9.9 (1.8) | |

| HR: HPV lasts 3 vs. 2 years | 3.9 (0.51) | 3.8 (0.41) | |

| HR: HPV lasts 4 vs. 3 years | 3.9 (0.51) | 2.6 (0.20) | |

| Deviance | 24606 | 24485 | |

| AIC | 24626 | 24505 |

Fig. 2.

Hazard ratio for precancer/cancer by years of HPV duration (left graph) and hazard ratio for 1-year HPV duration (right graph). The horizonal line represents a hazard ratio of 1.

In contrast, the linear duration model estimates a constant HR of 3.9 per year of increase in HPV duration. Figure 2 (right graph) compares this constant 1-year hazard ratio of 3.9 (dotted line) versus the 1-year increase in hazard ratio from the log(duration) model starting from an x-year infection. For example, per 1-year increase, the log(duration) model has an HR of 9.9 for a 1-year increase in HPV duration from 1-year to 2-years. This is higher than the 1-year increase HR of 3.9 from the constant HR model. The HR is 3.8 for 1-year increase in HPV duration from 2-years to 3-years, comparable to the 3.9 from the constant HR model. The HR of 2.6 is a 1-year increase in HPV duration from 3-years to 4-years, lower than the 3.9 from the constant HR model. Thus, while the overall hazard ratio continues to increase with each year, the hazard ratio for each extra 1-year increment attenuates towards 1.

The frailty from the log-duration model implies that womens’s mean HPV infection duration varies by a factor lognormally-distributed with mean exp(1.212/2) = 2.08 and standard deviation 3.8. The middle 95% of these factors lies in the range (0.093,11). This hundred-fold range in factors shows that for typical women, their mean HPV infection duration can be much shorter, or far longer, than their covariates might otherwise predict. In the Discussion, we suggest potential unmeasured factors that might account for part of these vast differences.

Age was best modeled quadratically in both submodels. HPV in older women tended to be of longer duration, most likely because their infection represented those that had evaded immune control for many years and thus more likely to continue persisting (Rodriguez et al., 2010). However, risk of precancer/cancer decreased with age, because screening women when they are younger finds and removes precancer and leads to a deficit at older ages (in the absence of screening, risk increases with age because where precancers are not removed at young ages) (Gage et al., 2014). Thus, although two infections of the same duration have the same carcinogenic potential in isolation, that has to be discounted by age because of screening.

As expected, the scale parameter κ < 1 indicates an increasing hazard of precancer/cancer with time. Unexpectedly, the scale parameter τ = 0.79 indicates that each woman’s hazard of clearing HPV infection is proportional to t1/0.79−1 = t0.27, which increases slightly with time. The marginal Weibull model for HPV clearance shown in the right panel of Figure 1 has a decreasing hazard of clearing HPV infection with time (proportional to t−0.16), as seen in other papers (Rodriguez et al., 2008). It is well known that marginal (or cross-sectional) analyses of trends over time need not yield the same results as trends within a person over time as in a conditional longitudinal analysis (Diggle et al., 1994). The decreasing marginal hazard in this model could be explained by the presence of frailty: women with highest hazard of clearing HPV infection do so quickly, leaving only the those at lowest hazard of clearing as the long-term HPV infections, making the population-average hazard decrease with time even though each woman’s hazard of clearing HPV may slightly increase with time. Regardless, the exponents of 0.27 or −0.16 imply that both the woman-specific hazard and marginal hazard essentially flatten quickly with increasing time.

5. Sensitivity to Parametric Modeling Assumptions

We examined the sensitivity of our joint model to departures from the assumed Weibull distributions on the event times and normal distribution of the frailty. We conducted simulations using a log-duration model f(di) = log(di) to generate data under 3 simulation scenarios: Weibull event times and normal frailty (ie correctly-specified model), (2) weibull event times but log-gamma frailty (ie misspecified frailty), and (3) lognormal time to HPV clearance, Weibull time to precancer/cancer, and normal frailty (ie 1 misspecified survival model). All 10,000 observations (close to our data’s sample size of 9553) in each simulation were interval-censored or right-censored to mirror the KPNC data, where parameters were selected so that 5-year HPV clearance was about 80%, 5-year precancer/cancer risk was about 20%, and the standard devation of the frailty is 0.5. To each of the 1000 simulated datasets, we fit the log-duration model assuming Weibull event times and normal frailties. We calculate model parameters and also the mean and standard deviation (”stdev”) of the 5-year risks of clearing HPV and of developing precancer/cancer. We did not propose variance estimates for 5-year mean risk or standard devation of risk, so we only calculate the percent bias for these. For the third scenario, there is no true τ parameter because time to HPV clearance is generated from a lognormal, not Weibull.

Table 2 shows the percent bias and coverage of 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each scenario. The first scenario is Weibull event times and normal frailty (i.e. no model misspecification) and the model fits the data with no bias and excellent CI coverage. The second and third scenarios lead to fitting a misspecified model. In spite of misspecification, the bias for each parameter is not more than 8 percent and often closer to zero. As expected, the CI coverage for the misspecified frailty is not good, and for a misspecified survival distribution is bad. But the low bias under misspecification suggests that the problem is in the variance estimates. Importantly, the biases for the mean and standard deviation of 5-year precancer/cancer risk are not large even under model misspecification.

Table 2.

Percent bias and confidence interval coverage of misspecified log-duration joint model parameters.

| parameters | Survival: Frailty: |

Simulation Scenarios | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weibull Normal |

Weibull log-gamma |

lognormal Normal |

||

| α | % bias 95% CI |

0.3% 95.6% |

2% 80.5% |

3% 46.1% |

| β | % bias 95% CI |

−0.3% 95.3% |

−0.2% 95.8% |

2% 45.5% |

| τ | % bias 95% CI |

−0.1% 96.6% |

−0.3% 94.3% |

- - |

| κ | % bias 95% CI |

0.02% 94.7% |

4% 66.7% |

2% 87.1% |

| σ | % bias 95% CI |

−1% 94.2% |

0.7% 94.8% |

1% 92.5% |

| 5-year mean HPV clearance |

% bias 95% CI |

−0.08% - |

−0.1% - |

−0.3% - |

| 5-year stdev HPV clearance |

% bias 95% CI |

0.06% - |

4% - |

7% - |

| 5-year mean precancer/cancer risk |

% bias 95% CI |

−0.8% - |

2% - |

2% - |

| 5-year stdev precancer/cancer risk |

% bias 95% CI |

0.2% - |

−8% - |

6% - |

We note that the distribution of the shrunken empirical Bayes frailty estimates (Wolfinger, 1999) cannot be used to select a frailty distribution (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2013). The shrunken frailties will underestimate the true variance. Also, a normality assumption on the random effects can force the estimated frailties to look normally-distributed even when they are not (Verbeke and Lesaffre, 1996).

6. Implications for screening intervals

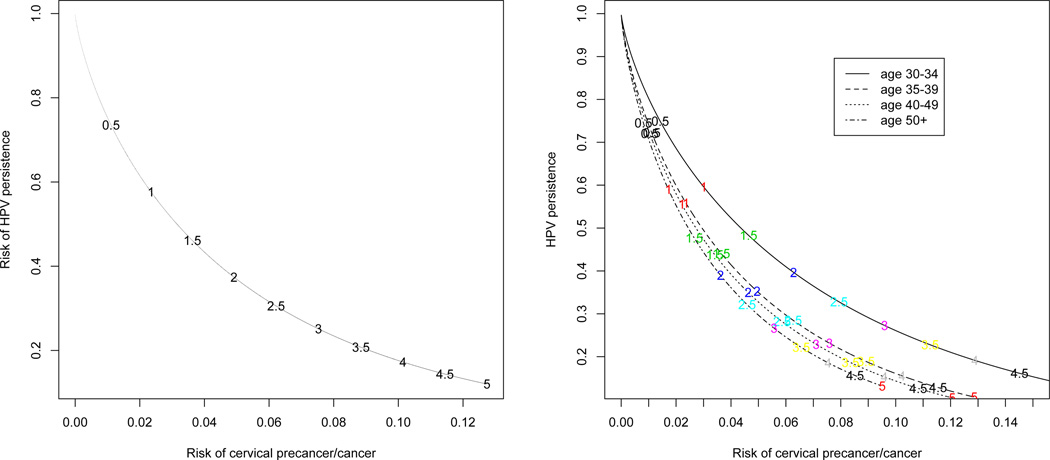

The decision on a screening interval must trade off risk of cervical precancer/cancer with the risk of conducting invasive procedures. Since any woman who at her return visit remained HPV-positive was referred for biopsies, the risk of HPV persistence is equivalent to the risk of conducting invasive procedures. As noted in the introduction, current cervical screening guidelines are based on population-average risk (Katki et al., 2013a), not the individual (conditional) risks that are provided by the joint model. We first examine the implications for screening intervals based on separate marginal Weibull models for calculating population-average risk of precancer/cancer and of HPV persistence. The left panel of Figure 3 contrasts the risk of precancer/cancer and of HPV persistence from separate Weibull models (no covariates) fit to the entire dataset for each screening interval (intervals are noted on the plot). For example, for a 1-year screening interval, the precancer/cancer risk is 2.3% and the HPV persistence is 57%. Thus a 1-year screening interval would biopsy 57% of the women and the precancer/cancer risk is 2.3%. For a 2-year screening interval, the HPV persistence risk drops to 37% but the precancer/cancer risk rises to 4.9%. The right panel of Figure 3 shows these tradeoffs by age, where both Weibull models now have age as a covariate. A 1-year screening interval has HPV persistence risk between 55%–60% for all ages, but the 1-year precancer/cancer risk varies more with age; for ages 50+ it is 1.7% but for ages 30–34 it is 3.0%. Thus using the same screening interval for all women will mix together women of very different risk. Risk could be better managed by using a risk-cutoff implying different screening intervals for different women. For example, a 5% risk-cutoff suggests that women age 30–34 return in 1.5 years, age 35–49 in 2 years, and women age 50+ in 2.5 years.

Fig. 3.

Marginal risk of HPV persistence (equal to the risk of undergoing invasive procedures) versus marginal risk of cervical precancer/cancer for different screening intervals, both overall (left panel) and by age groups (right panel)

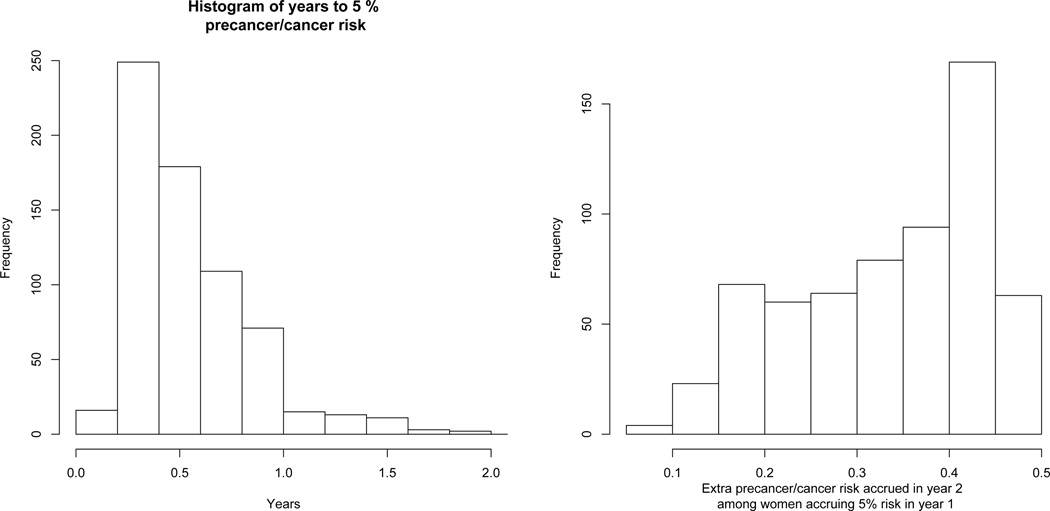

The above risks were all population-average risks for women who fall into certain known categories, such as age. A 5% population-average risk threshold implies a 2-year screening interval. In contrast, the joint model calculates each woman’s individual risk of precancer/cancer and risk of HPV persistence. We use the log-duration joint model with the estimated empirical Bayes frailties for all calculations. Figure 4 shows the histogram for the number of years to a precancer/cancer individual risk cutoff of 5% among the women who achieve 5% individual risk in 2 years. Among women who achieved 5% individual risk over 2 years, almost all (93.4%) did so in the 1st year. Consequently, for a 5% risk threshold, increasing the screening interval from 1 to 2 years would have identified only 6.6% more women at 5% risk in KPNC.

Fig. 4.

Left panel: Histogram for the number of years to achieve an individual risk of 5%, among those achieving 5% individual risk within 2 years. Risks were calculated using the log-duration joint model. Right panel: Histogram of the excess risk accrued in year 2 for women accruing at least 5% risk of cervical precancer/cancer in year 1.

Furthermore, the women who crossed the 5% risk threshold in the 1st year continued to accrue even more risk in year 2. The right panel of Figure 4 shows the distribution of the extra precancer/cancer risk accrued in the 2nd year for the women who exceeded 5% risk in 1 year, which is clearly substantial, averaging 33%. As would be expected, each of these women also has greater than 91% probability that their HPV infection would last 2 years (all had estimated mean HPV duration of at least two years). The joint model suggests that, in order to limit individual precancer/cancer risk to 5%, rather than the 2-year screening interval suggested by the marginal population-average model, a 1-year screening interval would capture nearly everyone who would have 5% individual risk in 2-years, while avoiding having those women needlessly continue to accrue beyond 5% risk during the second year. The large frailty variance is driving this heterogeneity of individual risk. The population-average risk threshold of 5% at 2 years is an average over 2 very different groups of women: those at much higher than 5% risk and those at much lower than 5% risk. This heterogeneity cannot be assessed by marginal population-average risk models and requires a conditional model of individual risk. If instead, risk had been distributed such that most of the women who achieve 5% individual risk in 2 years achieve it between years 1 and 2, then that would have made a stronger case for 2-year screening interval, especially as the longer the screening interval, the more likely HPV will clear without intervention.

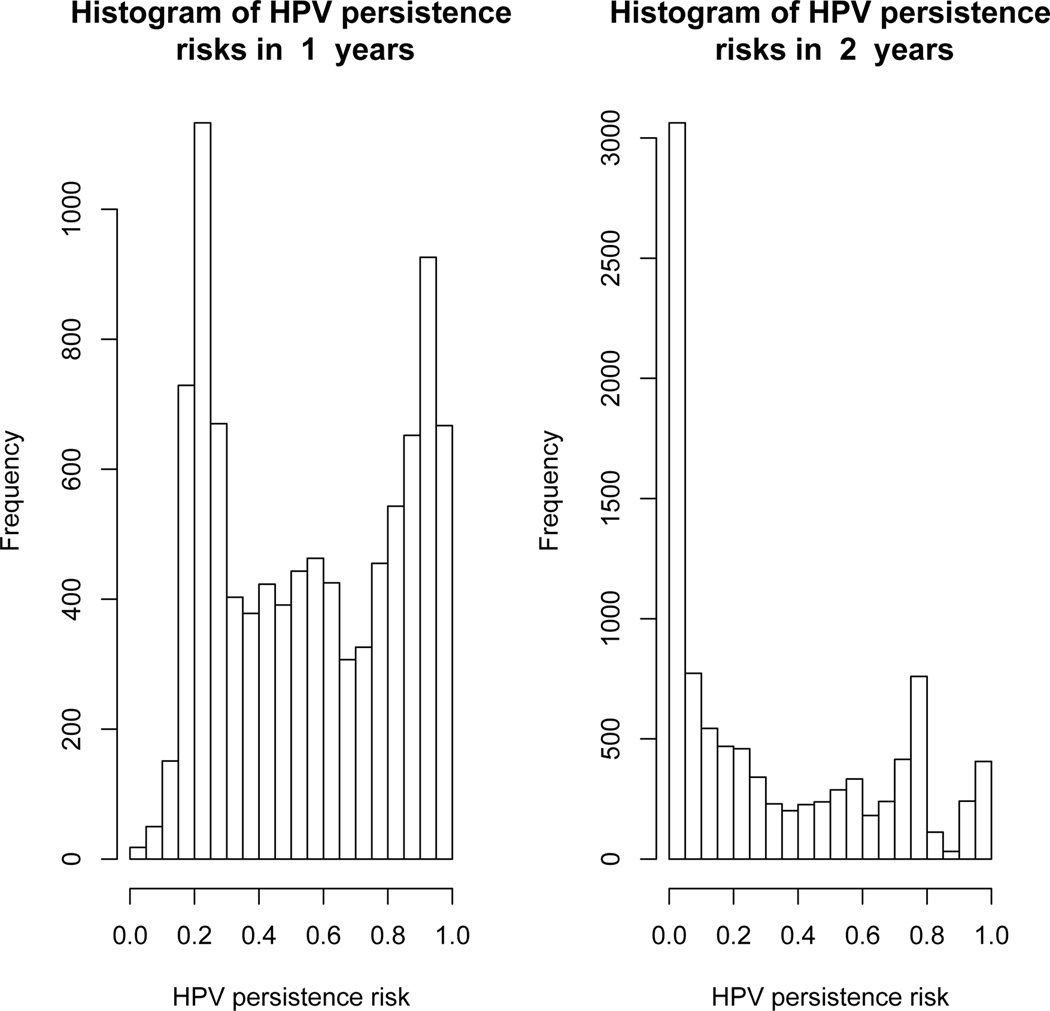

Because individual risk is ”front-loaded” in the 2-year interval, then the only advantage of a 2-year screening interval versus a 1-year interval is that there is less HPV persistence and thus fewer biopsies will be required. Figure 5 shows histograms of HPV persistence risk at 1-year and at 2-years. At 1-year, the marginal mean HPV persistence risk was 57%, but risk was bimodal and symmetric, with one peak around 20% (with little persistence risk below 5%) and another peak around 90%. The bimodality demonstrates that the marginal mean masks strong variation in HPV persistence risk between women. However, in spite of the bimodality, many infections remained in the middle range of indeterminate fate. At 2-years, there is a peak for < 5% persistence, a small peak around 80%, and many fewer infections in the middle range of interdeterminate fate. Thus, the joint model shows that at 2-years, infections more strongly separate themselves into groups almost sure to clear in 2 years and those almost sure to persist 2 years. Again, the marginal population-average HPV persistence risk conceals strong variation in individual HPV persistence risk between women.

Fig. 5.

Histograms of HPV persistence risk at 1-year (left graph) and at 2-years (right graph).

7. Discussion

We developed a joint model of individual cervical precancer/cancer risk and HPV persistence risk and illustrated some implications of it for cervical cancer screening. We believe our joint model takes a novel approach to bivariate survival analysis by regressing one mean survival time on the other mean survival time, while accounting for informative interval censoring of HPV infection duration due to treatment of cervical precancers. Our joint model also gives an estimate of the precancer/cancer risk accrued by each additional year of HPV infection, a fundamental quantity in cervical cancer epidemiology, but which has never before been calculated (to our knowledge). The hazard ratio for precancer/cancer risk by HPV infection duration versus a 1-year HPV infection increased as duration to the power of 3.3, demonstrating that risk dramatically increases with HPV duration. However, as compared to an HPV infection of 1 year shorter duration, the hazard ratio remains elevated but attenuates towards 1 when comparing against longer duration infections. Because any HPV infection present at the 2nd screening visit will trigger a biopsy, the joint model also directly yields the risk of undergoing invasive procedures, which is necessary to trade-off against precancer/cancer risk.

The advantage of a joint individual risk model over marginal population-average risk models is that the joint model informs us about how risk is distributed among women, with some implication for screening. Risk was very unequally distributed, with a small fraction of women accruing most of the risk in a population, and the vast majority having their HPV infection clear and having nearly zero risk. For example, if the goal is to control precancer/cancer ”risk” at 5%, the marginal model showed that 5% population-average risk is achieved at 2-years. This suggests that the screening interval should be 2-years. But the joint model calculates individual risk and its distribution, and almost all the women whose precancer/cancer risk exceeded 5% over two years also exceeded 5% in the first year. These women continued to accrue substantially higher than 5% individual risk in the second year. Thus, the joint model suggests that to limit individual risk to 5%, a 1-year screening interval would be more appropriate. This example illustrates that there can be a difference in implications for screening between population-average risk versus individual risk, especially when the distribution of individual risk is uneven. From an individual’s perspective, controlling individual risk is of primary interest. Public health officials would be interested in controlling population-average risk to ensure that population disease risk, invasive interventions, and program costs are controlled overall.

Thus the marginal model masks a concentration of precancer/cancer risk in a minority of women. The large variation in risk is mostly due to the large frailty variance estimated, where some women have 100 times the HPV infection duration of other women. This variance is not due to small sample size or chance, it is due to unmeasured woman-specific factors. Some unmeasured factors known to affect HPV clearance would be the duration of the HPV infection before detection, the genotype of the HPV infection (Plummer et al., 2007), previous history of HPV infections, or sexual behavior (Cuzick et al., 2008). Other factors that probably play a role, but more research is needed, are p16 staining (Carozzi et al., 2013), and HPV methylation (Mirabello et al., 2012). Although may of these factors are available in research studies, few if any of these would be available in routine clinical practice. Futhermore, many other factors about which little is known also likely play a crucial role, such as host immunology (Schiffman et al., 2009). Unfortunately, these populations are latent and cannot be identified ahead of time. But another useful conclusion from this joint model is that it is likely that there exist other factors strongly predictive of HPV infection duration, and thus precancer/cancer risk, that would be useful for screening.

The popular approaches to bivariate survival analysis that we are aware of either treat the association between the survival times as a nuisance, or of some intrinsic interest but summarize it using a correlational measure (Hougaard, 2000). Our approach of regressing one mean survival time on the other mean survival time, calculating the increase in one survival time per unit of the other survival time, seems like the natural approach that might be taken if there was no censoring. Our joint modeling approach may be a useful complement to standard approaches for analyzing bivariate survival data, and we provide our SAS code. Other researchers have published models focusing on the duration of HPV infection only (Kong et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2011) or risk of precancer/cancer only (Kirby and Spiegelhalter, 1994).

Using HPV test results as a time-dependent covariate in a simple model does not suffice for our purposes. HPV infection is an endogenous (not exogenous) covariate, affecting precancer/cancer risk, which feeds back into affecting the risk of HPV clearance (Rodriguez et al., 2010), and thus cannot be naively used as a time-dependent covariate. Using merely the time of testing HPV-negative does not address the scientific question of the effect of HPV duration (which cannot be directly observed) on precancer/cancer risk. Treatment of precancer informatively censors the duration of HPV infection because the women who develop precancer are those who are likely to have the longest duration of HPV infection. Finally, relying only on the time of testing HPV-negative ignores the interval-censoring of the true HPV clearance time that needs to be explicitly accounted for to allow us to consider hypothetical screening intervals.

Our joint model has limitations. We noted the difficulties in fitting this model. The parametric modeling is required to estimate mean survival times. However, in the presence of interval censoring, parametric modeling is often not overly restrictive (Lindsey, 1998). Individual risk models require assumptions about the distribution of risk, and diagnostics for misspecification of latent random-effects are notoriously challenging (Rizopoulos, 2012, Ch. 6.4). At least, linear mixed models may be relatively insensitive to misspecification (Verbeke and Lesaffre, 1996) and standard joint models of longitudinal and survival data may be insensitive to misspecification as well (Song et al., 2002; Huang et al., 2009; Rizopoulos et al., 2010). Our simulation, under true normally-distributed frailties, shows that the shrunken empirical Bayes estimated frailties did not have a normal distribution, showing that this distribution cannot be used for diagnostics (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2013). It is likely that the bias in the estimates would increase with the frailty variance. Choice of frailty distribution is a challenging issue for random-effects modeling and remains a limitation. Furthermore, it is possible that many women who clear HPV might be cured and will not develop precancer or cancer in the long-run. It might be desirable to account for a potential cure fraction, but this would be identifiable only with longer follow-up of women than we currently have. Women with large frailties can be considered as essentially cured, so joint modeling of frailty and cure would be challenging. Also, our model only concerns women whose first HPV test result is positive. More sophisticated stochastic models are needed to account for aquisition of HPV to handle future HPV test results.

For our purpose of modeling the precancer/cancer risk per year of HPV infection, we did not include Pap smear results. The Pap smear result is not a confounder of the HPV-precancer/cancer relationship because HPV is the ultimate cause of all downstream carcinogenic events. The Pap smear should not be used as a covariate because it is a surrogate for the gold-standard outcome measure, which is the biopsy result to determine the presence of precancer/cancer. Consequently, treating the Pap smear as a covariate would be akin to regressing on the outcome itself.

A burgeoning area of research is dynamic models for predicting individual disease risk based on all currently-available longitudinal risk factor information (Proust-Lima and Taylor, 2009; Sweeting and Thompson, 2011; Taylor et al., 2013, e.g). One could imagine generalizing this joint model into a dynamic model incorporating longitudinal biopsy results, HPV test results, and Pap smear results over time that would be better suited to making individual risk predictions. Such a model might efficiently incorporate all relevant aspects of a woman’s medical history to make the best possible precancer/cancer risk predictions. As dynamic individual disease risk models become more popular, more work needs to be done to understand the different implications of using population-average risk versus individual risk for developing medical guidelines.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank Dr. Thomas S. Lorey and Dr. Gene Pawlick (Regional Laboratory of the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program) for creating and supporting the data warehouse, and Kaiser Permanente Northern California for allowing use of the data.

Appendix 1: Identifiability of the joint model

Denote Φ(·, σ) the normal c.d.f. with mean zero and standard deviation σ. Recall that given the random effect, HPV and CIN are independent. As is customary, all quantities are subject to a given covariate whose value is fixed at x. Identifiability is based on the observable marginal joint survival distribution after integrating out the random effect:

| (9) |

where SHPV (t) and SCIN(s) are given by equations (7,8). Consider the observable marginal joint distributions implied by 2 sets of parameters

The proof proceeds by showing that if J(t, s) = J̃(t, s), a.e. x, then the parameter sets must be the same. Since this equality must be true for all (t, s), in particular it must be true for s = 0, where SCIN(0; ⋯) = 1. Thus, equating the two joint distributions J and J̃ at s = 0 we obtain

If these two distributions are the same, then their r-th moments must be equal. Consequently,

Using explicit formula for the integer r-th non-central moment for the Weibull distribution, we get

An explicit integration with the normal c.d.f. then yields the following identity (in r):

| (10) |

First note that (10) yields

Note that the right hand side of this equality does not involve x. Assuming the covariate is not a constant a.e. yields β = β̃. Thus, on simplification, from (10), we readily obtain the identity

or equivalently,

Since the above equality holds now for all r > 0, using well-known properties of the Gamma function, we readily obtain σ = σ̃, γ = γ̃. We have thus established equality of the parameters (β, γ, σ) = (β̃, γ̃, σ̃). This in particular also shows that d = d̃ as the computation of d depends only on ω and the aforementioned parameters.

Now equating now the two joint distributions (9) by first setting t = 0 and noting that σ = σ̃ and d = d̃, we obtain as before

A similar argument as before yields α = α̃ and δ = δ̃.

Appendix 2: Fitting the joint model

We developed a 5-step procedure to develop good starting values to fit the joint model (4) in SAS:

Fit Weibull regression model (1) to HPV duration (without frailty) using PROC LIFEREG

Use the previous parameter estimates as starting values for PROC NLMIXED to fit the full HPV duration model (1) with frailty

Using the empirical Bayes estimate of each woman’s frailty ωi from PROC NLMIXED, calculate and save the mean HPV duration for each woman (2)

Fit Weibull regression model (3) to precancer/cancer data with covariates, including a covariate for the previously calculated mean HPV duration estimates, in PROC LIFEREG. This is a 1-step joint model assuming fixed frailties.

Take the previous parameter estimates as starting values to estimate the full joint model (4) in PROC NLMIXED

For our dataset of nearly 10,000 observations, it took about 30 minutes to fit the model with the above procedure. Our SAS code for the final step to fit the full joint model is below.

proc nlmixed data=fullscrn QMAX=100 QTOL=1E-06 qpoints=10 itdetails;

* Starting parameters from the previous 4 steps;

PARMS scale_hpv=0.730 beta0=6.573 beta1=−0.213 beta2=0.0641 logfrailtystdev=0.029;

scale_cin=1.034 alpha0=20.536 alpha1=0.125 alpha2=0.032 alphabetai=−1.662;

BOUNDS scale_hpv>0, scale_cin>0;

* Set up regression models;

fixed_hpv = beta0 + beta1*agestd + beta2*agestd**2;

lp_hpv = fixed_hpv + betai;

RR_hpv = exp(-lp_hpv); * don’t forget that negative sign!;

logMeanDuration = lgamma(1+scale_hpv) - (-lp_hpv);

fixed_cin = alpha0 + alpha1*agestd + alpha2*agestd**2;

lp_cin = fixed_cin + logMeanDuration*alphabetai;

RR_cin = exp(-lp_cin); * don’t forget that negative sign!;

* Conditional survival (HPV) at lower and upper limits of the intervals;

S_lower_hpv = exp(-(RR_hpv*lower)**(1/scale_hpv));

if CENSORID=1 then S_upper_hpv = exp(-(RR_hpv*upper)**(1/scale_hpv));

* Conditional survival (CIN2+) at lower and upper limits of the intervals;

S_lower_cin = exp(-(RR_cin*lower_cin)**(1/scale_cin));

S_upper_cin = exp(-(RR_cin*upper_cin)**(1/scale_cin));

* Time to precancer/cancer: right-censored (0) and interval-censored (1);

if intcens_cin=0 then loglik = log(S_lower_cin);

if intcens_cin=1 then loglik = log(S_lower_cin-S_upper_cin);

* Contributions from HPV duration: right-censored (0) and interval-censored (1);

if CENSORID=0 then loglik = loglik + log(S_lower_hpv);

if CENSORID=1 then loglik = loglik + log(S_lower_hpv-S_upper_hpv);

* Specify a GENERAL model with random effect;

MODEL lower ~ GENERAL(loglik);

RANDOM betai ~ normal(0,exp(2*logfrailtystdev)) subject=PID out=EBjoint;

run;

Contributor Information

Hormuzd A. Katki, Email: katkih@mail.nih.gov, Division of Cancer Epidemilogy and Genetics, US National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda MD, USA..

Li C. Cheung, Infomation Management Services, Inc., Calverton MD, USA.

Barbara Fetterman, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Berkeley CA, USA..

Philip E. Castle, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, The Bronx NY, USA.

Rajeshwari Sundaram, Division of Intramural Population Health Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Rockville MD, USA..

References

- Armitage P, Doll R. The age distribution of cancer and a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1954 Mar;8(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1954.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy SL, Li Y, Ryan LM, Lipsitz S, Canner MJ, Wright R. Analysis of clustered and interval censored data from a community-based study in asthma. Stat Med. 2004 Dec;23(23):3607–3621. doi: 10.1002/sim.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi F, Gillio-Tos A, Confortini M, Del Mistro A, Sani C, De Marco L, Girlando S, Rosso S, Naldoni C, Dalla Palma P, Zorzi M, Giorgi-Rossi P, Segnan N, Cuzick J, Ronco G, CCwg NT. Risk of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia during follow-up in hpv-positive women according to baseline p16-ink4a results: a prospective analysis of a nested substudy of the ntcc randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013 Feb;14(2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Tsu V, Ronco G, Mayrand M-H, Dillner J, Meijer CJLM. Overview of human papillomavirus-based and other novel options for cervical cancer screening in developed and developing countries. Vaccine. 2008 Aug;26(Suppl 10):K29–K41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gage JC, Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Kinney WK. Age-stratified 5-year risks of cervical precancer among women with enrollment and newly detected HPV infection. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29143. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard P. Analysis of Multivariate Survival Data. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Stefanski LA, Davidian M. Latent-model robustness in joint models for a primary endpoint and a longitudinal process. Biometrics. 2009 Sep;65(3):719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, Lorey T, Poitras NE, Cheung L, Demuth F, Schiffman M, Wacholder S, Castle PE. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jul;12(7):663–672. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Gage JC, Kinney WK. Benchmarking CIN 3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013a Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S28–S35. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285423c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Gage JC, Kinney WK. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women who test Pap-negative but are HPV-positive. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013b Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S56–S63. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285437b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AJ, Spiegelhalter DJ. Modeling the precursors of cervical cancer. In: Lange N, Ryan L, Billard L, Brillinger D, Conquest L, Greenhouse J, editors. Case Studies in Biometry. Wiley-Interscience; 1994. pp. 359–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Gray RH, Moulton LH, Wawer M, Wang M-C. A modeling framework for the analysis of HPV incidence and persistence: a semi-parametric approach for clustered binary longitudinal data analysis. Stat Med. 2010 Dec;29(28):2880–2889. doi: 10.1002/sim.4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson SC, Alibegashvili T, Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Carriero C, Mergui J-L, Nieminen P, Prendiville W, Redman CWE, Rieck GC, Quaas J, Petry KU. HPV testing and vaccination in europe. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013 Jun; doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318286b8d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey JK. A study of interval censoring in parametric regression models. Lifetime Data Anal. 1998;4(4):329–354. doi: 10.1023/a:1009681919084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wentzensen N, Lawson HW ASCCPCGC. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013 Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S1–S27. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabello L, Sun C, Ghosh A, Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Wentzensen N, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Lorincz A, Burk RD. Methylation of human papillomavirus type 16 genome and risk of cervical precancer in a costarican population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Apr;104(7):556–565. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CE, Hudgens MG, King CC, Cu-Uvin S, Lo Y, Rompalo A, Sobel J, Smith JS. Discrete-time semi-markov modeling of human papillomavirus persistence. Stat Med. 2011 Jul;30(17):2160–2170. doi: 10.1002/sim.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Maucort-Boulch D, Wheeler CM ALTSG. A 2-year prospective study of human papillomavirus persistence among women with a cytological diagnosis of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. J Infect Dis. 2007 Jun;195(11):1582–1589. doi: 10.1086/516784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proust-Lima C, Taylor JMG. Development and validation of a dynamic prognostic tool for prostate cancer recurrence using repeated measures of posttreatment psa: a joint modeling approach. Biostatistics. 2009 Jul;10(3):535–549. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D. Dynamic predictions and prospective accuracy in joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data. Biometrics. 2011 Sep;67(3):819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D. Joint Models for Longitudinal and Time-to-Event Data. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Biostatistics Series CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos D, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Multiple-imputation-based residuals and diagnostic plots for joint models of longitudinal and survival outcomes. Biometrics. 2010 Mar;66(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, Sherman ME, Solomon D, Guilln D, Alfaro M, Morales J, Hutchinson M, Katki H, Cheung L, Wacholder S, Burk RD. Longitudinal study of human papillomavirus persistence and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3: Critical role of duration of infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010 Mar;102(5):315–324. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Wacholder S, Hildesheim A, Castle PE, Solomon D, Burk R PEGG. Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Apr;100(7):513–517. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007 Sep;370(9590):890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman M, Safaeian M, Wentzensen N. The use of human papillomavirus seroepidemiology to inform vaccine policy. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Nov;36(11):675–679. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bce102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Davidian M, Tsiatis AA. A semiparametric likelihood approach to joint modeling of longitudinal and time-to-event data. Biometrics. 2002 Dec;58(4):742–753. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, Merz CNB, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, McBride P, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Jr, Watson K, Wilson PWF. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart association Task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Nov [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG. Joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to-event data with application to predicting abdominal aortic aneurysm growth and rupture. Biom J. 2011 Sep;53(5):750–763. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting MJ, Thompson SG. Making predictions from complex longitudinal data, with application to planning monitoring intervals in a national screening programme. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2012 Apr;175(2):569–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2011.01005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JMG, Park Y, Ankerst DP, Proust-Lima C, Williams S, Kestin L, Bae K, Pickles T, Sandler H. Real-time individual predictions of prostate cancer recurrence using joint models. Biometrics. 2013 Mar;69(1):206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped censored and truncated data. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1976;38:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Lesaffre E. A linear mixed-effects model with heterogeneity in the random-effects population. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(433):217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. The gradient function as an exploratory goodness-of-fit assessment of the random-effects distribution in mixed models. Biostatis- tics. 2013 Jul;14(3):477–490. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxs059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger RD. Fitting non-linear mixed models with the new NLMIXED procedure. Proceedings of the 24th SAS Users Group International Conference, Miami Beach, paper 287.1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Carroll R. Estimation and comparison of changes in the presence of informative right censoring by modeling the censoring process. Biometrics. 1988;44:175–188. [Google Scholar]