Abstract

Purpose of Review

In this review, we summarize the current status of clinical trials using therapeutic cells produced from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). We also discuss combined cell and gene therapy via correction of defined mutations in human pluripotent stem cells and provide commentary on key obstacles facing wide-scale clinical adoption of pluripotent stem cell-based therapy.

Recent Findings

Initial data suggest hESC/hiPSC-derived cell products used for retinal repair and spinal cord injury are safe for human use. Early stage studies for treatment of cardiac injury and diabetes are also in progress. However, there remain key concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of these cells that need to be addressed in additional well-designed clinical trials. Advances using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system offer an improved tool for more rapid and on-target gene correction of genetic diseases. Combined gene and cell therapy using human pluripotent stem cells may provide an additional curative approach for disabling or lethal genetic and degenerative diseases where there are currently limited therapeutic opportunities.

Summary

Human pluripotent stem cells are emerging as a promising tool to produce cells and tissues suitable for regenerative therapy for a variety of genetic and degenerative diseases.

Keywords: Human pluripotent stem cells, CRISPR/Cas9, human clinical trials, gene therapy, cellular therapy

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several years, patient-specific pharmacotherapies have rapidly advanced in clinical medicine. Personalized or precision medicine-based treatments for cancer subsets and diseases such as cystic fibrosis demonstrate efficacy for many patients while minimizing side effects and improving upon the cost of care [1–4]. More recently, there has been increasing interest in extending this strategy to cell-based therapies to directly replace diseased or damaged tissue. Human pluripotent stem cells are ideal candidates for novel cell-based regenerative repair due to two unique characteristics: 1) they can self-renew indefinitely and 2) they can potentially differentiate into any cell type. The most widely studied and clinically useful pluripotent stem cell groups are human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), which will be the main focus of this review.

The in vitro culture of hESCs was first established in 1998. hESCs are isolated from the inner cell mass of the developing blastocyst [5]. While hESC maintenance originally required mouse embryonic fibroblasts and fetal bovine serum, it is now possible to routinely culture hESCs in completely defined and xenogenic-free conditions that promote self-renewal and retain differentiation potential [6–10]. hESCs are still considered the “gold standard” of human pluripotent stem cells. However, since hESC-derived cells used for therapies would be allogeneic, there remains the potential for immunological rejection unless immunosuppression or other strategies are implemented, as has been reviewed elsewhere [11–13].

The groundbreaking discovery of murine iPSCs in 2006 [14] and later hiPSCs in 2007 [15,16] demonstrated that somatic cells can be reverted into a pluripotent-like state similar to hESCs by transduction of a limited number of defined transcription factors. Since this seminal work, there has been steady progress to improve the reprogramming efficiency of adult cells using various viral, non-viral, and, more recently, small molecule approaches [17,18]. Concurrently, patient-specific hiPSCs have been derived and utilized for a wide variety of studies to better understand human genetic diseases [19–24] and as a platform for pharmaceutical high-throughput screening [25–27]. Many preclinical studies, as well as one clinical trial, further demonstrate the potential of iPSC-derived cells to provide a novel source for cell replacement therapy [*28, *29, 30–32].

In this review, we will highlight the early strategies and initial outcomes of hESC- and hiPSC-derived translational therapy with an emphasis on current clinical trials focused on directed differentiation of hESCs/hiPSCs. We will also address approaches for use of hiPSCs for correcting monogenetic diseases, the potential immunogenicity of autologous and allogeneic hESCs/hiPSCs, as well as quality improvement considerations for practical, wide-scale clinical adoption of stem cell therapy.

CURRENT PLURIPOTENT STEM CELL CLINICAL TRIALS

Initial trials using hESC- and hiPSC-derived cells have focused on therapeutic cell populations that do not require genetic modifications (beyond reprogramming to hiPSCs) and can be efficiently produced under current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) conditions (TABLE 1). The first Phase I, multicenter trial using hESC-derived cells was initiated by the Geron Corporation (Menlo Park, CA, USA). In this study, hESC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cell injections that demonstrated remyelination, growth, and gain of locomotion in rat models were planned for ten patients with subacute thoracic spinal cord injuries [33]. Only four patients were transplanted and the trial was abruptly halted due to a shift in Geron’s business strategy [34]. Initial reports from Geron state there were no adverse effects related to stem cell transplant in two patients [35]. Although it has been over five years since its conception, Asterias Biotherapeutics (Menlo Park, CA, USA) resurrected the trial in June 2015 and plans to treat an additional thirteen patients in a dose-escalation Phase I/IIa study [36].

Table 1.

Summary of Human Clinical Trials Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cells.

| Trial Number | Sponsor | Disease | Stem Cell |

Differentiated Cell at Delivery |

Method | Start Date |

End Date |

Phase | Estimated Enrollment |

Status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01217008 | Geron | Subacute thoracic spinal cord injury |

hESC | Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell |

Injection | Oct. 2010 |

Sept. 2013 |

I | 4/10 received transplant |

Suspended |

| NCT02302157 | Asterias Biotherapeutics |

Subacute thoracic spinal cord injury |

hESC | Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell |

Injection | Mar. 2015 |

Jun. 2013 |

I/II | 13 | Active, recruiting |

| NCT01345006 | Ocata Therapeutics |

Stargardt’s Macular Dystrophy |

hESC | Retinal Pigmented Epithelial Cell |

Injection | Apr. 2011 |

Aug. 2015 |

I/II | 16 | Ongoing, but not recruiting |

| NCT01344993 | Ocata Therapeutics |

Dry age- related macular degeneration |

hESC | Retinal Pigmented Epithelial Cell |

Injection | Apr. 2011 |

Sept. 2015 |

I/II | 16 | Ongoing, but not recruiting |

| -- | RIKEN | Wet age- related macular degeneration |

hiPSC | Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell |

Scaffold implant |

Sept. 2014 |

? | -- | 1 | Active |

| NCT02286089 | Cell Cure Neurosciences, Ltd. |

Dry age- related macular degeneration |

hESC | Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell |

Scaffold implant |

Apr. 2015 |

Aug. 2017 |

I/II | 15 | Active, recruiting |

| NCT02057900 | Assistance Publique- Hopitaux de Paris |

Heart Failure | hESC | SSEA1+Isl-1+ cardiomyocyte progenitor cell |

Fibrin scaffold implant |

Jun. 2013 |

Jun. 2017 |

I | 6 | Active, recruiting |

| NCT02239354 | ViaCyte | Type I diabetes mellitus |

hESC | Pancreatic progenitor cell (PEC-01) |

Encapsulated subcutaneous implant |

Sept. 2014 |

Aug. 2017 |

I/II | 40 | Active, recruiting |

As of August 2015.

hESC: human embryonic stem cell; hiPSC: human induced pluripotent stem cell.

Shortly after the Geron trial, a series of three trials focusing on transplant of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) derived from hESCs and hiPSCs in patients with macular diseases emerged. From a technical perspective, RPE is an attractive target for initial studies since it can be efficiently differentiated and purified in vitro under cGMP conditions, it requires a small number of cells to repopulate dysfunctional retinal tissue, and visual acuity improvement has been demonstrated in both human and animal models [37]. Human clinical trials transplanting fresh RPE into damaged subretinal space have previously been successful in improving vision and quality of life for patients with retinal disease [38–40]. Furthermore, from a patient management perspective, the eye is an ideal candidate since it may be immune privileged and the retina can be monitored noninvasively through ophthalmoscopy. Advanced Cell Technologies (now Ocata Therapeutics, Marlborough, MA, USA) led a Phase I and Phase II trial beginning in 2011 in which hESC-derived RPE cells were surgically injected into the subretinal space of eighteen patients with either Stargardt’s macular dystrophy or age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and were subsequently treated with immunosuppression up to 12 weeks post transplant [**41]. At 37 months post-treatment, no serious adverse effects (i.e. immunological rejection, teratoma formation, or cell transformation) related to stem cell transplant had been documented. Thirteen patients demonstrated a significant increase in subretinal pigmentation, indicative of successful hESC-derived RPE engraftment and proliferation. Best-corrected visual acuity improved in 10 eyes, improved or remained the same in 7 eyes, and decreased in only 1 eye following transplant [**41]. This study is the first documented hESC-based therapy to demonstrate not only safety from adverse effects, but also efficacy post transplant.

In September 2014, the first hiPSC-based trial was initiated by the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology (Kobe, Japan) for the treatment of wet AMD [31,32]. To date, one 70-year-old female received hiPSC-derived RPE, which were casted and surgically implanted onto a 1.3×3 mm monolayer sheet. These hiPSCs were generated from autologous (patient-specific) fibroblasts. While it is still too early for published results, Masayo Takahashi recently reported on the safety profile of these cells [42]. With the exception of subretinal edema attributed to the surgical approach, hiPSC-derived RPE were non-tumorigenic, negative for viruses, and did not cause a graft vs. host response. While not a primary endpoint for this study, preliminary data also suggest efficacy in improving visual acuity relative to the non-transplanted retina. Given these encouraging results, the group is rapidly moving forward with planned allogeneic transplants using HLA-banked hiPSCs for other retinal diseases.

There are two additional ongoing trials focused on cell replacement using hESC-derived cells. The first, initiated in 2013 (Paris Public Hospital, Paris, France), is a Phase I trial focusing on the safety of early stage hESC-derived cardiomyocyte progenitor cells (SSEA1+Isl-1+) in patients with severe heart failure. This study utilizes a surgically implanted fibrin gel scaffold to support SSEA1+Isl-1+ cells within a pericardial flap, which provides a microenvironment to support cardiomyocyte growth and differentiation [**43,44]. SSEA1+Isl-1+ cells are advantageous since they are developmentally restricted to the cardiomyocyte lineage and are not associated with teratoma or extracardiac tumor formation [44]. A total of six patients are to be enrolled with results pending. Some looming questions from this study include whether hESC-derived SSEA1+Isl-1+ cells differentiate into human cardiomyocytes once implanted, whether these cells electrically integrate with endogenous cardiomyocytes (i.e. prevent arrhythmias), and whether immunological rejection develops. The second trial, initiated by ViaCyte (San Diego, CA, USA) in November 2014, involves hESC-derived pancreatic progenitor cell (PEC-01™) transplantation for patients with Type I diabetes mellitus. PEC-01™ cells are reported as the progeny of post-foregut endodermal cells and ultimately differentiate with high efficiency into C-peptide secreting pancreatic β cells in vivo [45]. To circumvent immune responses and to promote angiogenesis near transplanted cells, PEC-01™ will be protected by proprietary encapsulation. Similar to the cardiac trial, it remains to be seen how many pancreatic β cells are formed in vivo from seemingly heterogeneous hESC-derived endodermal progenitors. Other pre-clinical studies suggest additional strategies to produce pancreatic cells from hESCs and hiPSCs and this approach will likely provide a new cellular platform in future trials for diabetic patients [*29].

THE NEW FRONTIER: Using gene-corrected pluripotent stem cells to cure monogenetic diseases

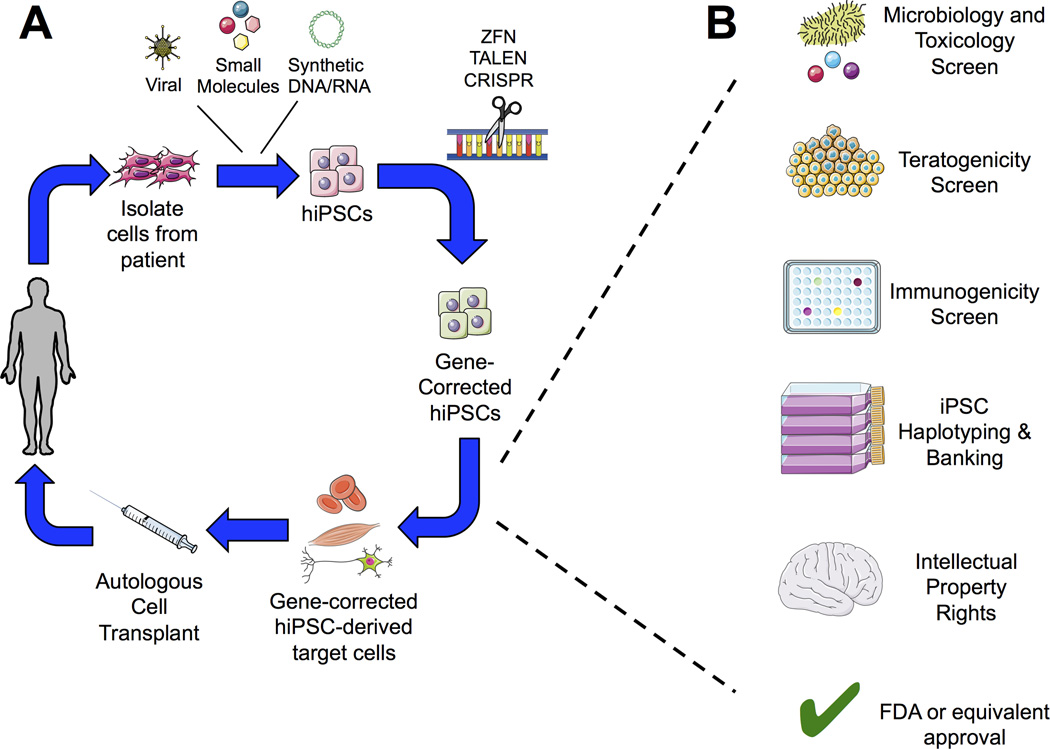

Although current clinical trials utilize unmodified hESCs and hiPSCs, there is keen interest to utilize gene-corrected stem cells for conditions with defined genetic etiologies. An initial proof-of-concept study was successfully implemented in a murine model for treatment of sickle-cell anemia [46]. With this approach, autologous cells (i.e. dermal fibroblasts or peripheral blood) from an affected patient would first be harvested and reprogrammed into hiPSCs. Gene modification of pathological mutations in hiPSCs would then be performed and cells subsequently would be expanded and differentiated into target cell lineages. The gene-corrected, differentiated cells would be transplanted back to the patient through direct injection or seeded on a biocompatible scaffold (FIGURE 1A). Three gene-correction approaches have been successfully implemented in pluripotent stem cells. Zinc finger nucleases (ZFN) were the earliest tool to induce site-specific repair. Although some groups successfully used ZFN in hESCs/hiPSCs for mutagenic repair that could be suitable for patients [47–49], this approach has fallen out of favor due to concerns in ZFN specificity within a targeted gene locus [50,51], difficulty in ZFN design [52], and time and cost in validating optimal ZFN sets [53]. In 2007, TAL effector nucleases (TALENs) subsequently emerged as an alternative for ZFNs. TALENs function similarly to ZFN, but possess dramatically improved specificity. There have been several reports demonstrating successful applications in hESCs/hiPSCs [54–56], however, TALENs also are subjected to the same concerns as ZFNs in that their delivery is mostly dependent on viral transduction [57], there is a high rate of non-specific targeting that may result in tumorigenesis (even if the intended target is a safe harbor site) [58], and validation can be laborious.

FIGURE 1. Clinical strategy for wide-scale hiPSC-based gene and cell therapy.

A. Dermal fibroblasts or peripheral mononuclear blood cells are obtained from patient with a defined genetic disease. hiPSCs are engineered from autologous cells via reprogramming with defined factors. Pathological mutations can be corrected through zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN), TAL effector nucleases (TALEN), or clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) gene-editing technologies. Gene-corrected hiPSCs can then be differentiated into the desired cell and/or tissue products prior to autologous transplantation via direct injection or seeding on a biocompatible scaffold. B. Prior to autologous cell transplantation, gene-corrected hiPSC-derived cell products must first pass several safety checkpoints, such as viral, toxicology, and tumorigenicity screens. Cells would also be immunophenotyped and banked for future patient use based on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) expression at this time. Furthermore, logistical hurdles such as obtaining intellectual property rights for product commercialization and regulatory agency approval must be in place prior to clinical trial.

The most promising current approach to hESCs/hiPSC targeted gene repair now lies in the clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) system. This system, originally discovered as an innate-like immune response in Streptococcus pyogenes, forms the basis behind eukaryotic gene editing by using a transfected guide RNA (gRNA) with complementarity to a targeted gene locus that also recruits exogenous Cas9 endonuclease. Site-specific double-strand cleavage via Cas9 only occurs if the template sequence possesses a 3’-NGG nucleotide motif. Insertions or deletions resulting in endogenous gene knockout arise if non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair ensues. Gene insertion (i.e. correction) via homology-directed repair (HDR) can also be accomplished if a repair template is cotransfected with the gRNA and Cas9. The CRISPR/Cas9 system possesses several advantages. First, gRNAs are simple to design and cost effective with several, well validated online tools available for optimal gRNA production for almost any gene locus of interest [59, 60, *61]. Second, on-target specificity is much greater than that of ZFN and TALENs [62]. Third, modifications can be multiplexed to target many genes simultaneously by introducing multiple gRNAs within the same plasmid [63]. Fourth, from initial gRNA design to final gene modified cells, production time can be as quick as 2–3 weeks [59]. Fifth, a Cas9 enzyme possessing catalytic domain variants that diminishes off-target effects can be efficiently transfected as transient, non-integrating mRNA [64].

Initial studies using CRISPR/Cas9 in human pluripotent stem cells have focused on correcting patient-derived hiPSCs for hematological conditions. Based on previous studies demonstrating the correction of β-thalassemia in hematopoietic stem cells by lentiviral-mediated TALEN delivery [65], Xie, et al. used CRISPR/Cas9 with a non-integrating piggyBac transposon to repair patient-derived iPSCs heterozygous for two common β-thalassemia mutations [*66]. This combination resulted in site-specific correction of the HBB locus and enabled erythroid cell production with successful expression of normal HBB. Notably, off-target effects were not observed in the six most-common sites of gRNA sequence homology. Smith, et al. assessed CRISPR/Cas9 correction of a heterozygous JAK2-V617F mutation causing polycythemia vera in patient-derived hiPSCs [*67]. Again, in this genetic repair system, Cas9 was more efficient and specific as compared to TALENs. When cotransfected with corrected homology donor templates, 25 of 29 hiPSC-derived JAK2-V617F clones had successful gene correction. Flynn, et al. were able to extend a similar approach in correcting hiPSCs engineered from patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) [*68]. In these patients, single point mutations in CYBB cause inappropriate NADPH oxidase complex synthesis and deregulation of the innate immune response. In hiPSCs, HDR CYBB correction occurred at a rate greater than 10% and of 60 isolated clones in one diseased hiPSC line, 23% were successfully modified with the wild-type sequence. Most importantly, in vitro phenotypic and functional correction of CGD was demonstrated in monocytes that were differentiated from the gene-corrected hiPSCs, though in vivo studies were not performed.

There is also a very high potential for pluripotent stem cell-based gene therapy in additional targets, such as skeletal muscle. Li, et al. offer one of the first insights to correcting of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) using CRISPR/Cas9 in patient-derived hiPSCs [*69]. Exon knockin with a wild-type dystrophin template caused a complete restoration of the dystrophin protein in terminally differentiated skeletal muscle cells. Moreover, this approach yielded an 84% success rate, making it a feasible route for clinical translation. Collectively, these recent studies provide strong and convincing evidence that CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing of human pluripotent stem cells is a feasible and highly efficient method to generate phenotypically normal cells from diseased patients.

REMAINING BARRIERS FOR CLINICAL IMPLEMENTATION OF HUMAN PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS

One major concern in translating pluripotent stem cells from bench to bedside is the issue of immunological tolerance to allogeneic and, paradoxically, autologous cell transplants of genetically repaired cells [70–72]. While it has been suggested that hESCs are immune privileged [73,74], several studies demonstrate some mature cell lineages derived from ESCs become immunogenic [75, 76]. Moreover, newly synthesized protein products generated from autologous, gene-corrected cells could also elicit an immune response, similar to inhibitory antibody synthesis in patients receiving Factor VIII or IX replacement therapy for hemophilia [77]. Although these problems may be circumvented with immunosuppression or other strategies [11,12], such therapy may predispose patients to therapeutic complications, such as infection, renal failure, or neurotoxicity. Despite the fact that current clinical trials using hESCs routinely include immunosuppressive medications, it remains unclear for what duration and levels of these medications is required—an area that should remain an important priority for future study. As with other transplantation therapies, it is necessary to balance the benefit of correcting and potentially curing a disabling disease with the risk of the cells and drugs used for treatment.

Several approaches have been proposed to limit immune responses against hESC and/or hiPSC-derived cells. Perhaps most promising is the concept of hiPSC banking based on HLA genotype, similar to what is currently performed for umbilical cord blood cells utilized for hematopoietic cell transplantation [78]. Indeed, Yamanaka and colleagues are pioneering HLA-homozygous hiPSC banking in Japan. Computational models predict a bank of only 50 hiPSC lines would be sufficient to cover roughly 91% of the total Japanese population with three-locus HLA compatibility (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-DR) [79]. Alternatively, CRISPR/Cas9 or other methods can be used to reduce expression of immune cell activators (i.e. HLA molecules, co-stimulatory molecules, NK cell activating receptor ligands, etc.) on hESC/hiPSC-derived cells [80,81]. Another approach would be to combine hiPSC transplantation with adoptive T-regulatory (Treg) cell or mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) transfer. These cells have anti-inflammatory modulators and have demonstrated efficacy for preventing immune responses in human clinical trials [82–84].

There remain many logistical barriers that must still be overcome to streamline pluripotent stem cell therapy for patient use (FIGURE 1B). Therapeutic cells of interest must be produced in an efficient manner using methods compatible with cGMP regulations. Methodologies to produce these therapeutic cells can be complicated, requiring stringent regulatory oversight and standard operating procedures to ensure consistent and reproducible hESC/hiPSC-derived cell products. hESC/hiPSC-derived products must also be subjected to appropriate karyotype or more detailed genetic testing, screening for adventitious agents, toxicology screening, etc. prior to receiving approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or other foreign regulatory body for clinical trials. Additionally, it is imperative that the purity of target populations remains high to minimize the possibility of adverse effects such as tumors from transplanted stem cell-derived products. Reporter proteins or genomic switches that are unique to differentiated products should be considered in future hESC/hiPSC engineering for this reason.

CONCLUSION

The earliest clinical trials demonstrate hESC- and hiPSC-derived therapies are safe and likely efficacious. The combination of site-specific gene correction provides opportunity to produce a curative option for a variety of diseases. While advances in the lab and clinic are rapidly moving forward, it is essential that cell manufacturing and regulatory processes keep pace with the science to safely provide hESCs and hiPSC-based therapies to all patients who could potentially benefit.

KEY POINTS.

Initial clinical trials using hESC and hiPSC-derived cell products for spinal cord injury and retinal repair demonstrate these cells are safe and potentially efficacious.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system can be applied in human pluripotent stem cells to correct pathogenic mutations with improved efficiency and specificity than existing gene-editing technologies.

While promising for wide-scale clinical adoption, additional preclinical and clinical trials are needed to better understand potential immune responses resulting from autologous hESC- and hiPSC-derived cells used for transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MGA performed the literature review and wrote the manuscript. DSK wrote and edited the manuscript. Figure was produced in part using Servier Medical Art.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Support for studies in the Kaufman lab include: National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 HL067828 (DSK), R01 DE022556 (DSK), F30 DK107017 (MGA), and T32 GM113846 (DSK and MGA); Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology Award 00042454 (DSK); Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance (DSK); American Cancer Society (DSK); and Regenerative Medicine Minnesota (DSK).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw AT, Kim D-W, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2010;365(18):609–619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccart-Gebhart M, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):877–889. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendall SC, Stewart MH, Menendez P, et al. IGF and FGF cooperatively establish the regulatory stem cell niche of pluripotent human cells in vitro. Nature. 2007;448(7157):1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature06027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao S, Chen S, Clark J, et al. Long-term self-renewal and directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells in chemically defined conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(18):6907–6912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602280103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levenstein ME, Ludwig TE, Xu R-H, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor support of human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2006;24(3):568–574. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig TE, Levenstein ME, Jones JM, et al. Derivation of human embryonic stem cells in defined conditions. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(2):185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, et al. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odorico JS, Kaufman DS, Thomson JA. Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2001;19(3):193–204. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman DS. Toward clinical therapies using hematopoietic cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2009;114(17):3513–3523. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-191304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman DS, Thomson JA. Human ES cells--haematopoiesis and transplantation strategies. J Anat. 2002;200:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angelos MG, Kidwai F, Kaufman DS. Pluripotent Stem Cells and Gene Therapy. In: Laurence Jeffery, Franklin Michael., editors. Translating Gene Therapy to the Clinic. Elsevier; 2015. pp. 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao MS, Malik N. Assessing iPSC reprogramming methods for their suitability in translational medicine. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(10):3061–3068. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park I-H, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134(5):877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321(5893):1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee G, Papapetrou EP, Kim H, et al. Modelling pathogenesis and treatment of familial dysautonomia using patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2009;461(7262):402–406. doi: 10.1038/nature08320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unternaehrer JJ, Daley GQ. Induced pluripotent stem cells for modelling human diseases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1575):2274–2285. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for Long-QT Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;363(15):1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457(7227):277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Lei Y, Luo J, et al. Prevention of β-amyloid induced toxicity in human iPS cell-derived neurons by inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases and associated cell cycle events. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10(2):213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeish J, Roach M, Hambor J, et al. High-throughput screening in embryonic stem cell-derived neurons identifies potentiators of α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionatetype glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(22):17209–17217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egawa N, Kitaoka S, Tsukita K, et al. Drug screening for ALS using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(145):145ra104. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ye L, Chang Y-H, Xiong Q, et al. Cardiac Repair in a Porcine Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction with Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiovascular Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.009. This article demonstrates safety and efficacy of hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes in a large animal model.

- 29. Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gürtler M, et al. Generation of Functional Human Pancreatic β Cells In Vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. This article demonstrates large-scale production of human insulin secreting β-pancreatic cells derived from hiPSCs.

- 30.Li Y, Tsai Y-T, Hsu C-W, Erol D, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of human-induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) grafts in a preclinical model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Med. 2012;18(9):1. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2012.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cyranoski D. Stem cells cruise to clinic. Nature. 2013;494(7438):413. doi: 10.1038/494413a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cyranoski D. Japanese woman is first recipient of next-generation stem cells. Nature. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keirstead HS, Nistor G, Bernal G, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cell transplants remyelinate and restore locomotion after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4694–4705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0311-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker M. Stem-cell pioneer bows out. Nature. 2011;479(7374):459–459. doi: 10.1038/479459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth E, Jones L, Priest C, et al. Update on a phase 1 safety trial of human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (GRNOPC1) in subjects with neurologically complete, subactue spinal cord injuries. International Congress on Spinal Cord Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011:7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott CT, Magnus D. Wrongful Termination: Lessons From the Geron Clinical Trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:1398–1401. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leach LL, Clegg DO. Concise Review: Making stem cells retinal: methods for deriving retinal pigment epithelium and implications for patients with ocular disease. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2363–2373. doi: 10.1002/stem.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Binder S, Stolba U, Krebs I, et al. Transplantation of autologous retinal pigment epithelium in eyes with foveal neovascularization resulting from age-related macular degeneration: A pilot study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(2):215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen FK, Patel PJ, Uppal GS, et al. Long-term outcomes following full macular translocation surgery in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(10):1337–1343. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.172593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Zeeburg EJT, Maaijwee KJM, Missotten TO, et al. A free retinal pigment epitheliumchoroid graft in patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration: Results up to 7 years. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(1):120.e2–127.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwartz SD, Regillo CD, Lam BL, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in patients with age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy: follow-up of two open-label phase 1/2 studies. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):509–516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61376-3. This paper discusses the initial results of the two clinical trials using hESC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells for treatment of Stargardt's macular dystrophy and age-related macular degeneration.

- 42.Takahashi M. Retinal Cell Therapy Using iPS Cells; International Society for Stem Cell Research Annual Meeting; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Menasché P, Vanneaux V, Fabreguettes J-R, et al. Towards a clinical use of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac progenitors: a translational experience. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:743–750. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu192. This manuscript summarizes the production and provides preclinical evidence of clinical-grade hESC-derived cardiomyocyte progenitor cells that are currently in use in human trials.

- 44.Bel A, Planat-Bernard V, Saito A, et al. Composite cell sheets: A further step toward safe and effective myocardial regeneration by cardiac progenitors derived from embryonic stem cells. Circulation. 2010;122:S118–S123. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(11):1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318(5858):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, et al. Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(9):851–857. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang C-J, Bouhassira EE. Zinc-finger nuclease-mediated correction of α-thalassemia in iPS cells. Blood. 2012;120(19):3906–3914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunet E, Simsek D, Tomishima M, et al. Chromosomal translocations induced at specified loci in human stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(26):10620–10625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902076106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lombardo A, Genovese P, Beausejour CM, et al. Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(11):1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/nbt1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isalan M. Zinc-finger nucleases: how to play two good hands. Nat Methods. 2011;9(1):32–34. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeFrancesco L. Move over ZFNs. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):681–684. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding Q, Lee YK, Schaefer EAK, et al. A TALEN genome-editing system for generating human stem cell-based disease models. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(2):238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hockemeyer D, Wang H, Kiani S, et al. Genetic engineering of human pluripotent cells using TALE nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):731–734. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osborn MJ, Starker CG, McElroy AN, et al. TALEN-based gene correction for epidermolysis bullosa. Mol Ther. 2013;21(6):1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergmann T. Progress and problems with viral vectors for delivery of talens. J Mol Genet Med. 2014;08(01):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piganeau M, Ghezraoui H, De Cian A, et al. Cancer translocations in human cells induced by zinc finger and TALE nucleases. Genome Res. 2013;23(7):1182–1193. doi: 10.1101/gr.147314.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. 2013;8(11):2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11(2):122–123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2812. Free, computational program for easy generation of gRNA for CRISPR/Cas9 applications.

- 62.Ding Q, Regan SN, Xia Y, et al. Enhanced efficiency of human pluripotent stem cell genome editing through replacing TALENs with CRISPRs. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(4):393–394. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153(4):910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154(6):1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Payen E, Negre O, et al. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human β-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467(7313):318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Xie F, Ye L, Chang JC, et al. Seamless gene correction of β-thalassemia mutations in patient-specific iPSCs using CRISPR/Cas9 and piggyBac. Genome Res. 2014;24:1526–1533. doi: 10.1101/gr.173427.114. One of the first studies utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in human pluripotent stem cells to correct HBB mutation associated with β-thalassemia.

- 67. Smith C, Abalde-Atristain L, He C, et al. Efficient and allele-specific genome editing of disease loci in human iPSCs. Mol Ther. 2014;23(3):570–577. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.226. This manuscript successfully uses CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing to repair JAK2-V617F mutations associated with polycythemia vera in patient-derived hiPSCs.

- 68. Flynn R, Grundmann A, Renz P, et al. CRISPR-mediated genotypic and phenotypic correction of a chronic granulomatous disease mutation in human iPS cells. Exp Hematol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.06.002. pii: S0301-472X(15)00207-6. Proof-of-principle study demonstrating CRISPR/Cas9 gene correction of CYBB gene in patient-derived hiPSCs.

- 69. Li HL, Fujimoto N, Sasakawa N, et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;4(1):143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.013. A comparative approach in gene correction demonstrate exon-knockin of dystrophin gene was highly efficient for expressing full-length dystrophin protein in patient-derived pluripotent stem cells.

- 70.Zhao T, Zhang Z-N, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474(7350):212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schuetz C, Markmann JF. Immunogenicity of β-cells for autologous transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2015;98:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simonson OE, Domogatskaya A, Volchkov P, Rodin S. The safety of human pluripotent stem cells in clinical treatment. Ann Med. 2015;1:1–11. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1051579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Baroja ML, Majumdar A, et al. Human embryonic stem cells posses immune-privileged properties. Stem Cells. 2004;22:448–456. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-4-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drukker M, Katz G, Urbach A, et al. Characterization of the expression of MHC proteins in human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2002;99(15):9864–9869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142298299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swijnenburg RJ, Tanaka M, Vogel H, Baker J, Kofidis T, Gunawan F, et al. Embryonic stem cell immunogenicity increases upon differentiation after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 2005;112(9 SUPPL.):166–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Swijnenburg R-J, Schrepfer S, Cao F, Pearl JI, Xie X, Connolly AJ, et al. In vivo imaging of embryonic stem cells reveals patterns of survival and immune rejection following transplantation. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17(6):1023–1029. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witmer C, Young G. Factor VIII inhibitors in hemophilia A: rationale and latest evidence. Ther Adv Hematol. 2012:59–72. doi: 10.1177/2040620712464509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rao M, Ahrlund-Richter L, Kaufman DS. Concise review: Cord blood banking, transplantation and induced pluripotent stem cell: Success and opportunities. Stem Cells. 2012;30(1):55–60. doi: 10.1002/stem.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakatsuji N, Nakajima F, Tokunaga K. HLA-haplotype banking and iPS cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):739–740. doi: 10.1038/nbt0708-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carlsten M, Childs RW. Genetic manipulation of NK Cells for cancer immunotherapy: Techniques and clinical implications. Front Immunol. 2015;6:266. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Snanoudj R, De Préneuf H, Créput C, et al. Costimulation blockade and its possible future use in clinical transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19(9):693–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(14):3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, Cao Q, et al. Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2011;117(3):1061–1070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-293795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Introna M, Rambaldi A. Mesenchymal stromal cells for prevention and treatment of graft-versus-host disease: successes and hurdles. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20(1):72–78. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]