Abstract

Diarrhoea is one of leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Recent estimations suggested the number of deaths is close to 2.5 million. This study examined the causative agents of diarrhoea in children under 5 years of age in suburban areas of Khartoum, Sudan. A total of 437 stool samples obtained from children with diarrhoea were examined by culture and PCR for bacteria, by microscopy and PCR for parasites and by immunoassay for detection of rotavirus A. Of the 437 samples analysed, 211 (48 %) tested positive for diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli, 96 (22 %) for rotavirus A, 36 (8 %) for Shigella spp., 17 (4 %) for Salmonella spp., 8 (2 %) for Campylobacter spp., 47 (11 %) for Giardia intestinalis and 22 (5 %) for Entamoeba histolytica. All isolates of E. coli (211, 100 %) and Salmonella (17, 100 %), and 30 (83 %) isolates of Shigella were sensitive to chloramphenicol; 17 (100 %) isolates of Salmonella, 200 (94 %) isolates of E. coli and (78 %) 28 isolates of Shigella spp. were sensitive to gentamicin. In contrast, resistance to ampicillin was demonstrated in 100 (47 %) isolates of E. coli and 16 (44 %) isolates of Shigella spp. In conclusion, E. coli proved to be the main cause of diarrhoea in young children in this study, followed by rotavirus A and protozoa. Determination of diarrhoea aetiology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of diarrhoeal pathogens and improved hygiene are important for clinical management and controlled strategic planning to reduce the burden of infection.

Introduction

Diarrhoeal diseases remain one of the leading causes of preventable death in developing countries, especially among children under 5 years of age. In 2008 alone, around nine million children under 5 years died and around 40 % of those deaths were due to pneumonia and diarrhoea (You et al., 2010). Globally, diarrhoea is the second largest cause of death in children under 5 years of age, causing one in every five deaths. Unfortunately, diarrhoea kills more children than AIDS, malaria and measles combined (WHO, 2008).

Diarrhoea is common in the developing countries, especially in areas with poor hygiene and sanitation and with limited access to safe water. Other conditions, such as malnutrition, may further increase the risk of contracting diarrhoea in developing countries. These factors may lead to a significant disease burden and negative economic effects, resulting from medical costs, loss of work, lower quality of life and high mortality.

Infectious organisms, including bacteria, viruses, protozoa and helminths, cause diarrhoea. These organisms are transmitted from the stool of one individual to the mouth of another, a route termed faecal–oral transmission. However, they differ in the exact route of entry from stool to mouth and in the infectious dose needed to cause the illness. Escherichia coli is considered to be the aetiological agent of many diseases, including some affecting the urinary tract and intestine. The classification of diarrhoeagenic E. coli (DEC) strains is based on their virulence properties and comprises six groups: enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAggEC) and diffuse adhering E. coli (DAEC) (Nataro & Kaper, 1998).

In Sudan, diarrhoea is one of the most common reasons for children to visit healthcare clinics, but knowledge of the causative agents of these diarrhoea cases is limited.

The enteric pathogens rotavirus and DEC are the most common causes of diarrhoea globally (Parashar et al., 1998) with DEC cited as the most important cause in developing countries (Gomes et al., 1991). Rotavirus is the leading cause of acute infantile gastroenteritis globally and is responsible for 20 % of deaths in children under 5 years of age (de Zoysa & Feachem, 1985).

In addition to rotavirus and DEC, other enteropathogens including Shigella spp., Salmonella spp., Vibrio cholerae and Campylobacter spp. may cause diarrhoea.

In Sudan infant mortality is 102 per 1000 live births and neonatal mortality is 51 per 1000 live births. Khartoum is the capital city of Sudan with a total population of 5 million. It is located in the centre of Sudan and administratively divided into seven localities. Around 80 % of the population of Khartoum State population live in the urban area (El Tayeb et al., 2014).

Infectious diseases cause most of these deaths (UNICEF, 2014), but the aetiological agents are usually not known and therefore misuse of antibiotics is common. This has led to antibiotic resistance becoming a major problem in Sudan.

The aims of this study were therefore to identify the aetiology of diarrhoea in Khartoum, Sudan, and to determine the antibiotic susceptibility of the organisms isolated.

Methods

Sample collection.

Faecal samples (one per subject) were collected in sterile containers from children with diarrhoea (defecation more than three times within 24 h of hospital admission) in the period from January 2013 to December 2013 . All faeces were stored in the collection containers with Cary–Blair transport medium at 4 °C and transported to the microbiological laboratory within 24 h. The residue of each sample after the first culture on medium was kept at −70 °C for further analyses.

Isolation and identification of diarrhoeal pathogens.

Stool samples were processed and analysed for micro-organisms and intestinal parasites at the laboratory of the University of Medical Sciences and Technology Hospital (UMST) (Khartoum, Sudan). Standard culture and identification methods were used to identify enteric pathogens (WHO, 1987). Intestinal parasites were identified by direct microscopy of wet mount preparations. Positive samples for Entamoeba were identified to species level by PCR to differentiate between E. histolytica and E. dispar (Saeed et al., 2011). For group A rotavirus, stool samples were analysed using the SD BIOLINE Rota Rapid test (catalogue no. 14 FK10; Standard Diagnostics) as described by the manufacturer.

For DEC, Shigella spp. and Salmonella spp., stool samples were cultured on MacConkey agar, thiosulphate citrate bile salt (TCBS) and deoxycholate citrate agar (for Shigella spp. and Salmonella spp.). All plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. All samples were tested for Vibrio cholerae, Shigella spp. and Salmonella spp. by colony morphology, biochemical properties and agglutination with specific antisera (Mast Diagnostica). For Campylobacter spp., the stool samples were inoculated on blood-free charcoal-based selective medium (CCDA) (bioMérieux) and blood-containing medium selective for Campylobacter spp. (bioMérieux). A multiplex PCR using eight primer pairs specific for the virulent genes of five different types of DEC was used for the identification of E. coli from the subcultured bacteria (Table 1) (Nguyen et al., 2005).

Table 1. Primers used for multiplex PCR for detection of diarrhoeagenic E. coli.

| Primer | Target gene | Primer sequence | bp |

| LT | eltB | 5′TCTCTATGTGCATACGGAGC3′ | 322 |

| 5′CCATACTGATTGCCGCAAT3′ | |||

| ST | estA | 5′GCTAAACCAGTAGAGGTCTTCAAAA3′ | 147 |

| 5′CCCGGTACAGAGCAGGATTACAACA3′ | |||

| VT1 | vt1 | 5′GAAGAGTCCGTGGGATTACG3′ | 130 |

| 5′AGCGATGCAGCTATTAATAA3′ | |||

| VT2 | vt2 | 5′ACCGTTTTTCAGATTTTGACACATA3′ | 298 |

| 5′TACACAGGAGCAGTTTCAGACAGT3′ | |||

| eae | eaeA | 5′CACACGAATAAACTGACTAAAATG3′ | 376 |

| 5′AAAAACGCTGACCCGCACCTAAAT3′ | |||

| SHIG | ial | 5′CTGGTAGGTATGGTGAGG3′ | 320 |

| 5′CCAGGCCAACAATTATTTCC3′ | |||

| bfpA | bfpA | 5′TTCTTGGTGCTTGCGTGTCTTTT3′ | 367 |

| 5′TTTTGTTTGTTGTATCTTTGTAA3′ | |||

| EA | pCVD | 5′CTGGCGAAAGACTGTATCAT3′ | 630 |

| 5′CAATGTATAGAAATCCGCTGTT3′ |

Antimicrobial sensitivity.

The antibiotic sensitivity of the micro-organisms isolated from the faeces of children to different antibiotics was tested using Mueller–Hinton agar (Himedia) and the standard disc diffusion technique of the modified Kirby–Bauer method, as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). For the disc susceptibility testing (BD), disc content and zone size scoring were as follows; ampicillin (10 mg) ≥17 mm sensitive and ≤13 mm resistant, amikacin (30 µg) ≥17 mm sensitive and ≤14 mm resistant, ceftazidime (30 µg) ≥18 mm sensitive and ≤14 mm resistant, gentamicin (10 µg) ≥15 mm sensitive and ≤12 mm resistant and nalidixic acid (30 µg) ≥19 mm sensitive and ≤13 mm resistant were used.

Statistical analysis.

The chi-squared (χ2) test was used to determine the statistical significance of the data. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Occurrence of pathogens

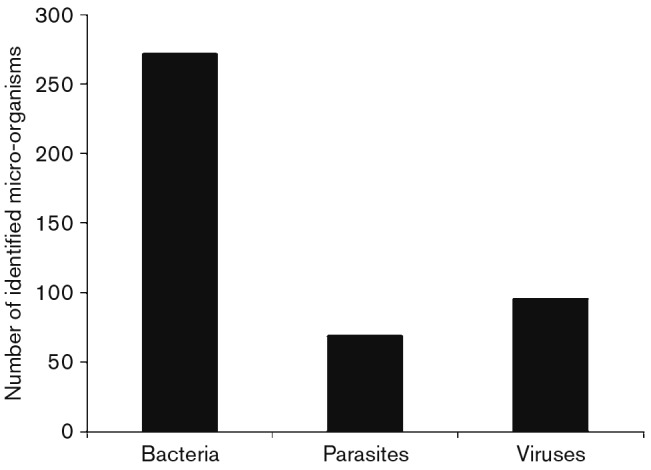

Bacterial infection was the main cause of diarrhoea in children, and among the total cases of bacterial infection (Fig. 1), E. coli caused 48 %, Shigella spp. caused 8 %, Salmonella spp. caused 4 % and Campylobacter spp. caused 2 %. No Vibrio species were isolated from the 437 samples.

Fig. 1. Total number of different aetiological agents found in the 437 diarrhoeal cases included in the study.

Of the E. coli detected, the most frequent type was EAEC (43 %), followed by EPEC (29 %), ETEC (18 %) and EIEC (9 %). Of the 36 Shigella isolates, 36 % were S. flexneri, followed by S. sonnei (33 %) and S. dysenteriae (11 %). The Salmonella isolates represented two different serotypes, S. typhi (76 %) and S. paratyphi (24 %). All eight Campylobacter isolates were of C. jejuni.

Rotavirus was found in 22 % of the children with diarrhoea. The virus was most common in the 49–60 month age group.

Protozoic parasites were found in 16 % of the 437 children. Giardia intestinalis was found in 11 % of the children, followed by Entamoeba histolytica in 5 % of the children. All micro-organisms identified in the stool specimens are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Micro-organisms identified in stool samples from child diarrhoeal cases.

| Micro-organism | Number of cases (%) |

| Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) | 91 (21) |

| Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) | 61 (14) |

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) | 39 (9) |

| Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) | 20 (4) |

| Shigella sonnei | 12 (3) |

| Shigella flexneri | 20 (4) |

| Shigella dysenteriae | 4 (1) |

| Salmonella typhi | 13 (2) |

| Salmonella paratyphi C | 4 (1) |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 8 (3) |

| Giardia intestinalis | 47 (11) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 22 (5) |

| Rotavirus A | 96 (22) |

| Total | 437 (100) |

Distribution of the diarrhoea among the 437 children according to age and gender in this study was as follows: 5 % were aged 0–6 months, 6 % were 7–24 months, 5 % were 25–36 months, 18 % were 37–48 months and 66 % were 49–60 months. Of the diarrhoea cases in the study, 240 (55 %) were boys and 197 (45 %) girls, giving a ratio male to female of 1 : 0.82 (Table 3). The rate of diarrhoea in the oldest group (49–60 months) of children and in the males was significantly higher (P<0.0001).

Table 3. Number of child diarrhoeal cases identified, subdivided according to child age and gender.

| Age group (months) | Males | Females | Total |

| 0–6 | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| 7–24 | 9 | 19 | 28 |

| 25–36 | 8 | 15 | 23 |

| 37–48 | 23 | 56 | 79 |

| 49–60 | 193 | 94 | 287 |

| Total | 240 | 197 | 437 |

| P-value (χ2-test) | <0.0001 | ||

Clinical features and seasonality

Of the 437 children with diarrhoea, 98 % had watery diarrhoea and 2 % had bloody diarrhoea. Fever was apparent in 53 % of the children, most commonly children with shigellosis and rotavirus. Vomiting was seen in 55 % of the children and dehydration in 60 % of the children. The viral infections tended to occur during winter, the bacterial infections during summer and autumn and parasitic infections were seen only during the rainy season.

Antimicrobial sensitivity

All (211/211) of the E. coli isolates were sensitive to chloramphenicol, while 206 isolates of the 212 tested were sensitive to ceftazidime, 198 to ciprofloxacin, 200 to gentamicin, 160 to tetracycline, 150 to amikacin, 140 to nalidixic acid and only 100 to ampicillin (Table 4). Among the total Shigella species (n = 36), 30 were sensitive to chloramphenicol, 28 to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, 24 to ceftazidime, 20 to tetracycline, 19 to amikacin, 18 to nalidixic acid and 18 to ampicillin (Table 5). Among the Salmonella spp. (n = 17), sensitivity to chloramphenicol, gentamicin and tetracycline was found in 17 of the isolates, while 15 isolates were sensitive to ceftazidime and ciprofloxacin and 11 isolates were sensitive to amikacin, nalidixic acid and ampicillin (Table 6). Campylobacter were sensitive to all antibiotics tested except for two isolates that were resistant to ampicillin.

Table 4. Antimicrobial sensitivity of E. coli isolates (n = 211).

| Antibiotics | Sensitive (%) | Intermediate (%) | Resistant (%) |

| Amikacin | 150 (71) | 0 | 62 (29) |

| Ampicillin | 100 (47) | 12 (6) | 100 (47) |

| Ceftazidime | 206 (97) | 0 | 6 (3) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 198 (93) | 2 (1) | 12 (6) |

| Chloramphenicol | 211 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 200 (94) | 3 (2) | 9 (4) |

| Nalidixic acid | 140 (66) | 0 | 72 (34) |

| Tetracycline | 160 (75) | 2 (1) | 50 (24) |

Table 5. Antimicrobial sensitivity of Shigella spp. isolates (n = 36).

| Antibiotics | Sensitive (%) | Intermediate (%) | Resistant (%) |

| Amikacin | 19 (53) | 3 (4) | 14 (39) |

| Ampicillin | 18 (50) | 2 (6) | 16 (44) |

| Ceftazidime | 24 (67) | 4 (11) | 8 (22) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 28 (78) | 5 (14) | 3 (8) |

| Chloramphenicol | 30 (83) | 2 (6) | 4 (11) |

| Gentamicin | 28 (78) | 4 (11) | 4 (11) |

| Nalidixic acid | 19 (53) | 5 (14) | 12 (33) |

| Tetracycline | 20 (56) | 8 (22) | 8 (22) |

Table 6. Antimicrobial sensitivity of Salmonella isolates (n = 17).

| Antibiotics | Sensitive (%) | Intermediate (%) | Resistant (%) |

| Amikacin | 11 (64) | 3 (18) | 3 (18) |

| Ampicillin | 11 (64) | 2 (12) | 4 (24) |

| Ceftazidime | 15 (88) | 2 (12) | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 15 (88) | 0 | 2 (12) |

| Chloramphenicol | 17 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 17 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Nalidixic acid | 11 (64) | 2 (12) | 4 (24) |

| Tetracycline | 17 (100) | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

In this study, we used a combination of conventional and molecular techniques to investigate the aetiological agent (bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens) in stool samples from children with diarrhoea living in an urban area in Khartoum, Sudan. Of the 437 samples tested, 240 were from male children and 197 from females, giving a male to female ratio of 1.2 : 1. All children in the study were under 5 years of age. The largest number of samples was from the 49–60 month age group 287 (66 %), followed by the 37–48 month age group 79 (18 %). Among the total of 437 samples tested in the study, bacterial pathogens were detected in 272 (62 %) samples.

The rate of the diarrhoea was higher in male children, 240 (55 %), than in female children, 197 (45 %), as reported in many previous studies (Klein et al., 2006; Moyo et al., 2011; Shariff et al., 2003; Sherchand et al., 2009) and the ratio of male to female children affected by diarrhoeal disease was distinct from that in other studies, which found that male and female children were equally affected (Mashoto et al., 2014). The majority of positive samples 366 (84 %) were found in children older than 2 years, particularly those aged 4–5 years as noted above. The prevalence of diarrhoea in children above 2 years was found to be significantly higher (P<0.01). Contaminated hands is one of the most common routes for transmission of food-borne infections, which might be one reason why diarrhoea was high in the age group 4–5 years, as poor hand washing practices in this age group are common.

The prevalence of diarrhoea caused by bacteria was significantly higher than that caused by viruses and parasitic infections, in contrast to results reported in other studies in different countries (Nitiema et al., 2011).This is probably because in contrast to previous studies, we investigated the presence of different DEC subgroups and Campylobacter, and these findings increased the detection of bacteria as the causative agents of diarrhoea.

E. coli was the most frequently detected pathogen, in contrast to published findings for other developing countries (Aryal, 1996; Maharjan et al., 2007; Mandomando et al., 2007; Sherchand et al., 2009). E. coli was detected in 48 % (211) of stool samples. EAEC was the most commonly detected type of E. coli in children in this study, present in 43 % (91) of cases, suggesting that it is the major cause of diarrhoea (Olesen et al., 2005), whereas some previous studies concluded that it is not associated with diarrhoea (Bonkoungou et al., 2012). However, those studies were conducted during the dry season, which may explain the differences. Therefore E. coli can be considered the most frequently isolated species of diarrhoeal disease in children in Khartoum.

Shigella species were detected in 36 (8 %) of the stool samples, with S. flexneri the most frequent isolate, 56 % (20/36), followed by S. sonnei, 33 % (12/36) and S. dysenteriae, 11 % (4/36). Other studies in Tanzania and in Jordan have reported similar results for shigellosis (Moyo et al., 2011; Youssef et al., 2000). Salmonella spp. were isolated from 4 % of the stool samples in this study. This percentage was similar to that obtained in others studies in East Africa, in Mozambique and Tanzania, where the prevalence was approximately 3 % (Mandomando et al., 2007; Moyo et al., 2011).

Among Salmonella spp., S. typhi was detected in 76 % (13/17) of cases and S. paratyphi C in 24 % (4/17). This is the first study to detect C. jejuni in Sudan. In fact, Campylobacter is not on the detection system in routine laboratory investigations on the aetiology of diarrhoea in Sudan.

Rotavirus was the second most common pathogen detected in our study, supporting the well-documented role of rotavirus in diarrhoea in children in the developing countries (Bonkoungou et al., 2010; Nitiema et al., 2011; O’Ryan et al., 2005; Rodrigues et al., 2007). The majority of rotavirus cases were detected in children aged over 2 years.

Intestinal parasites have always been an important public health problem in the developing countries, especially in tropical and subtropical areas (Easow et al., 2005). The prevalence of intestinal parasites causing diarrhoea was found to be around 16 % (69/437) in this study, among which G. intestinalis represented 68 % (47/69) and Entamoeba histolytica, 32 % (22/69). These results confirmed previous findings reported for the Kathmandu Valley (Shrestha et al., 2009; Thapa Magar et al., 2011).

The presence of blood in 2 % (9/437) of samples may be due to Entamoeba histolytica. The low positive rate of intestinal parasites found in this study may be due to the source of drinking water used, the fact that public toilets were located at a distance from houses and the availability of a toilet in most houses.

The antimicrobial susceptibility tests showed that among the 211 E. coli isolates tested, 100 % of isolates were demonstrated to be sensitive to chloramphenicol, while 97 % (206/211) demonstrated sensitivity to ceftazidime, 94 % (200/211) to gentamicin, 93 % (198/211) to ciprofloxacin and 75 % (160/211) to tetracycline. Very few isolates were resistant to the different antibiotics but among these 34 % (62/211) were resistant to nalidixic acid and 47 % (100/211) were resistant to ampicillin. Previous studies found that ciprofloxacin was 100 % (8) effective against E. coli and tetracycline was effective in 29 % (101) of cases, but that 50 % (8) of these bacteria were resistant to ampicillin (Al-Gallas et al., 2007; Kaminski et al., 1994). Among the 36 isolates of the Shigella spp. tested here, 83 % (30/36) were sensitive to chloramphenicol and 78 % (28/36) were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, whereas 44 % (16/36) of the isolates were resistant to ampicillin and 39 % (14/36) to amikacin. Bodhidatta et al. (2002) found that 100 % (56/56) of bacteria isolates tested were sensitive to ciprofloxacin, unlike in our study. This may be due to empirical use of these antibiotics and development of resistance in Sudan. Chloramphenicol, gentamicin and tetracycline were the most effective antimicrobials for Salmonella spp. with 100 % (17/17) sensitivity, followed by 88 % (15/17) to ciprofloxacin and ceftazidime. This is in contrast to the findings of Mandomando et al. (2007) that 92 % (12) of Salmonella isolates were sensitive to chloramphenicol and 85 % (11) to tetracycline. That study also found that 62 % (8) of Salmonella isolates were resistant to ampicillin and 8 % (1) to nalidixic acid. This finding of much lower resistance to ampicillin in our study may be due to Salmonella not being a major problem in Khartoum, Sudan. In this study, chloramphenicol, gentamicin and third generation cephalosporin were the most effective antibiotics against the bacteria causing diarrhoea, while amikacin, ampicillin and nalidixic acid were the least effective. However, the use of chloramphenicol in children is not recommended (Mandomando et al., 2007).

This study showed that the frequency of diarrhoea was higher in male children than in female children. Awareness about the prevention of the infectious diseases, improved hygiene and proper medication are needed to reduce the burden of the preventable infectious diseases among young children in Khartoum.

References

- Al-Gallas N., Bahri O., Bouratbeen A., Ben Haasen A., Ben Aissa R. (2007). Etiology of acute diarrhea in children and adults in Tunis, Tunisia, with emphasis on diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: prevalence, phenotyping, and molecular epidemiology. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77, 571–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal, B. K. (1996). Serological analysis of Escherichia coli isolated from various clinical specimens with special interest in gastroenteritis. PhD thesis, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Bodhidatta L., Vithayasai N., Eimpokalarp B., Pitarangsi C., Serichantalergs O., Isenbarger D. W. (2002). Bacterial enteric pathogens in children with acute dysentery in Thailand: increasing importance of quinolone-resistant Campylobacter. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 33, 752–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkoungou I. J. O., Sanou I., Bon F., Benon B., Coulibaly S. O., Haukka K., Traoré A. S., Barro N. (2010). Epidemiology of rotavirus infection among young children with acute diarrhoea in Burkina Faso. BMC Pediatr 10, 94. 10.1186/1471-2431-10-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkoungou I. J. O., Lienemann T., Martikainen O., Dembelé R., Sanou I., Traoré A. S., Siitonen A., Barro N., Haukka K. (2012). Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli detected by 16-plex PCR in children with and without diarrhoea in Burkina Faso. Clin Microbiol Infect 18, 901–906. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zoysa I., Feachem R. G. (1985). Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: chemoprophylaxis. Bull World Health Organ 63, 295–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easow J. M., Mukhopadhyay C., Wilson G., Guha S., Jalan B. Y., Shivananda P. G. (2005). Emerging opportunistic protozoa and intestinal pathogenic protozoal infestation profile in children of western Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J 7, 134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Tayeb S., Abdalla S., Van den Bergh G., Heuch I. (2014). Use of healthcare services by injured people in Khartoum State, Sudan. Int Health. 10.1093/inthealth/ihu063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T. A., Rassi V., MacDonald K. L., Ramos S. R., Trabulsi L. R., Vieira M. A., Guth B. E., Candeias J. A., Ivey C., et al. (1991). Enteropathogens associated with acute diarrheal disease in urban infants in São Paulo, Brazil. J Infect Dis 164, 331–337. 10.1093/infdis/164.2.331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski N., Bogomolski V., Stalnikowicz R. (1994). Acute bacterial diarrhoea in the emergency room: therapeutic implications of stool culture results. J Accid Emerg Med 11, 168–171. 10.1136/emj.11.3.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E. J., Boster D. R., Stapp J. R., Wells J. G., Qin X., Clausen C. R., Swerdlow D. L., Braden C. R., Tarr P. I. (2006). Diarrhea etiology in a children’s hospital emergency department: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 43, 807–813. 10.1086/507335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan R., Lekhak B., Shrestha C. D., Shrestha J. (2007). Detection of enteric bacterial pathogens (Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli O157) in childhood diarrhoeal cases. Sci World 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mandomando I. M., Macete E. V., Ruiz J., Sanz S., Abacassamo F., Vallès X., Sacarlal J., Navia M. M., Vila J., et al. (2007). Etiology of diarrhea in children younger than 5 years of age admitted in a rural hospital of southern Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76, 522–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashoto K. O., Malebo H. M., Msisiri E., Peter E. (2014). Prevalence, one week incidence and knowledge on causes of diarrhea: household survey of under-fives and adults in Mkuranga district, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 14, 985. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyo S. J., Gro N., Matee M. I., Kitundu J., Myrmel H., Mylvaganam H., Maselle S. Y., Langeland N. (2011). Age specific aetiological agents of diarrhoea in hospitalized children aged less than five years in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Pediatr 11, 19. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nataro J. P., Kaper J. B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 11, 142–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. V., Le Van P., Le Huy C., Gia K. N., Weintraub A. (2005). Detection and characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli from young children in Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol 43, 755–760. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.755-760.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitiema L. W., Nordgren J., Ouermi D., Dianou D., Traore A. S., Svensson L., Simpore J. (2011). Burden of rotavirus and other enteropathogens among children with diarrhea in Burkina Faso. Int J Infect Dis 15, e646–e652. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Ryan M., Prado V., Pickering L. K. (2005). A millennium update on pediatric diarrheal illness in the developing world. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 16, 125–136. 10.1053/j.spid.2005.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen B., Neimann J., Böttiger B., Ethelberg S., Schiellerup P., Jensen C., Helms M., Scheutz F., Olsen K. E. P., et al. (2005). Etiology of diarrhea in young children in Denmark: a case-control study. J Clin Microbiol 43, 3636–3641. 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3636-3641.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar U. D., Bresee J. S., Gentsch J. R., Glass R. I. (1998). Rotavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 4, 561–570. 10.3201/eid0404.980406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A., de Carvalho M., Monteiro S., Mikkelsen C. S., Aaby P., Molbak K., Fischer T. K. (2007). Hospital surveillance of rotavirus infection and nosocomial transmission of rotavirus disease among children in Guinea-Bissau. Pediatr Infect Dis J 26, 233–237. 10.1097/01.inf.0000254389.65667.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A., Abd H., Evengård B., Sandström G. (2011). Epidemiology of entamoeba infection in Sudan. Afr J Microbiol Res 5, 3702–3705. [Google Scholar]

- Shariff M., Deb M., Singh R. (2003). A study of diarrhoea among children in eastern Nepal with special reference to rotavirus. Indian J Med Microbiol 21, 87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherchand J. B., Yokoo M., Sherchand O., Pant A. R., Nakogomi O. (2009). Burden of enteropathogens associated diarrheal diseases in children hospital, Nepal. Sci World 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S. K., Rai S. K., Vitrakoti R., Pokharel P. (2009). Parasitic infection in school children in Thimi area, Kathmandu Valley. J Nep Assoc Med Lab Sci 10, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa Magar D., Rai S. K., Lekhak B., Rai K. R. (2011). Study of parasitic infection among children of Sukumbasi Basti in Kathmandu valley. Nepal Med Coll J 13, 7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2014). Levels & Trends in Child Mortality. Report 2014. Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New York, NY: United Nations Children's Fund. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (1987). Programme for control of diarrhoeal diseases. In Manual for Laboratory Investigation of Acute Enteric Infections. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2008). The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- You D., Wardlaw T., Salama P., Jones G. (2010). Levels and trends in under-5 mortality, 1990–2008. Lancet 375, 100–103. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61601-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef M., Shurman A., Bougnoux M. E., Rawashdeh M., Bretagne S., Strockbine N. (2000). Bacterial, viral and parasitic enteric pathogens associated with acute diarrhea in hospitalized children from northern Jordan. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 28, 257–263. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]