Abstract

Despite the commonly held belief that there is a high degree of intergenerational continuity in maltreatment, studies to date suggest a mixed pattern of findings. One reason for the variance in findings may be related to the measurement approach used, which includes a range of self-report and official indicators of maltreatment and both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. This study attempted to shed light on the phenomenon of intergenerational continuity of maltreatment by examining multiple indicators of perpetration of maltreatment in young adults and multiple risk factors across different levels within an individual’s social ecology. The sample included 166 women who had been placed in out-of-home care as adolescents (>85% had a substantiated maltreatment incident) and followed into young adulthood, and included three waves of adolescent data and six waves of young adult data collected across 10 years. The participants were originally recruited during adolescence as part of a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of the Treatment Foster Care Oregon intervention. Analyses revealed weak to modest associations between the three indicators of perpetration of maltreatment in young adulthood, i.e., official child welfare records, self-reported child welfare system involvement, and self-reported maltreatment (r = .03–.51). Further, different patterns of prediction emerged as a function of the measurement approach. Adolescent delinquency was a significant predictor of subsequent self-reported child welfare contact, and young adult partner risk was a significant predictor of perpetration of maltreatment as indexed by both official child welfare records and self-reported child welfare contact. In addition, women who were originally assigned to the intervention condition reported perpetrating less maltreatment during young adulthood. Implications for measurement and interventions related to reducing the risk for intergenerational transmission of risk are discussed.

Child maltreatment is a significant societal problem, with serious mental and physical health effects for victims and enormous costs to society (Carvalho et al, 2015; Cicchetti & Banny, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2009; Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, 2013). Official statistics from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2014) indicate that the rate of victimization in the United States is as high as 9.2 children per 1,000 children. Self-report studies reveal that as many as one-in-four U.S. children will experience some form of maltreatment in their lifetime (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormond, & Hamby, 2013). The total lifetime economic burden resulting from new cases of fatal and nonfatal child maltreatment in the U.S. is estimated to be approximately $124 billion, with each nonfatal case associated with a lifetime cost of $210,012, including childhood healthcare costs, adult medical costs, productivity losses, child welfare costs, criminal justice costs, and special education costs (Fang, Brown, Florence, & Mercy, 2012). One factor that may make child maltreatment so persistent and difficult to prevent is its intergenerational continuity. We used a multilevel approach to examine risk factors that were hypothesized to be associated with the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment in a sample of high-risk women who were removed from their parents and placed in out-of-home care as adolescents (and subsequently followed for a 10-year period) with the goal of identifying malleable factors that could be targeted in future interventions.

Intergenerational Continuity of Maltreatment

Beginning with the publication of a book on child abuse that served as a practical guide for professionals and laypersons (Kempe & Kempe, 1978), it has been a commonly held belief that parents who maltreat their children are likely to have been maltreated (as children) themselves. Indeed, some empirical studies have found support for the notion that a common outcome of experiencing maltreatment in childhood is engaging in interpersonal violence and maltreatment in adulthood (e.g., Heyman & Slep, 2002; Zuravin, McMillen, DePanfilis, & Risley-Curtis, 1996). For instance, longitudinal findings from the Rochester Youth Development Study revealed that victims of child maltreatment were 2.6 times more likely to perpetrate maltreatment with their own children than were those who had not been abused as children (Thornberry et al., 2013). Yet, there has also been significant critique of Kempe and Kempe’s (1978) claims regarding the high continuity of maltreatment across generations (e.g., Cicchetti & Aber, 1980), with some studies reporting the risk of intergenerational transmission to be weak to moderate (Renner & Slack, 2006). More exhaustive reviews and meta-analyses conclude that there is a modest, but significant risk of intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment (Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Thornberry, Knight & Lovegrove, 2012), but caution against generalizing results from single-sample studies due to methodological limitations and/or the unique nature of the sample utilized. Indeed, more recent reviews (e.g., Thornberry et al., 2012) find that studies with stronger designs showed only mixed support for the intergenerational transmission hypothesis, which challenges commonly held beliefs about intergenerational continuity and calls for additional research to investigate the nature of this association. More interestingly, perhaps, these studies also indicate that there are many individuals who have experienced maltreatment as children, but who do not go on to perpetrate maltreatment as adults (Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Thornberry et al., 2012). We attempt to help clarify the mixed evidence surrounding intergenerational transmission of maltreatment by: (a) utilizing longitudinal data from a high-risk sample of women who had been removed from the custody of their parent(s) as youth; (b) assessing multilevel predictors of risk within the individual’s social ecology; and (c) comparing across three different approaches to measuring perpetration of maltreatment.

A Multilevel Framework for Examining Risk for Maltreatment

As noted by Cicchetti (2013), one challenge for the field of maltreatment is to shift from its traditional focus on a single level of analysis to multilevel investigations that explore more than one domain of influence on the perpetration or outcomes of maltreatment. Indeed, an individual’s developmental trajectory is influenced by a myriad of individual, contextual, and societal factors that are layered and transactional (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993). By using a multilevel framework to study child maltreatment, we can better decipher the risk and protective factors and work toward developing more effective interventions that not only help prevent maltreatment, but also reduce the risk of psychopathology and behavioral health problems often associated with maltreatment. Moreover, using a more nuanced approach to understanding this complex phenomenon might also help clarify the mixed evidence surrounding intergenerational transmission of maltreatment. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems model lends itself well to this kind of investigation. Cicchetti and Lynch (1993) further elaborate on this model to propose an ecological-transactional framework that can be used to examine the interactional processes whereby maltreatment occurs and development is shaped as a result of risk and protective factors present within each level of the social ecology. These risk and protective factors can serve to exacerbate or deter the likelihood of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

Within this framework, the innermost layer of influence, i.e., the individual level, encompasses personal characteristics that are unique to the individual, such as genetic factors, temperament, and behavior. Next is the microsystem, which involves interpersonal relationships at the most immediate level, such as family, friends, partners, and relationships within the school or work environment. As noted by Cicchetti (2004), because it is the level of the ecology closest to an individual, characteristics of the microsystem have the most direct effects on development, and the most relevance to understanding child maltreatment. The mesosystem, which comes next, comprises the interactions between two microsystems. For example, an individual’s family connecting with his/her romantic partner represents a mesosystem for a young adult. Following the mesosystem is the exosystem, which includes relationships that occur between two spheres within the individual’s ecology, one of which the individual is not directly involved. For example, a parent may become incarcerated, which affects the caregiving situation for the child. The outermost layer of the ecological model is the macrosystem, which encompasses the larger cultural environment. The individual does not directly interact with this system, yet it can have a meaningful impact on development. In this study we focus jointly on factors within the individual level (adolescent delinquency), the microsystem (partner behavior), and the exosystem (family contextual risk), using a sample of women who had been exposed to the child welfare and juvenile justice macrosystems during adolescence and followed longitudinally into young adulthood.

Family Contextual Risk: The Influence of the Exosystem

Numerous studies have documented that the family context a child experiences across development can have a significant influence on future risk for engagement in maltreatment. For instance, Thornberry et al. (2014) found that multiple aspects of the family context, such as low parental income, teenage parenthood, parental experiences of negative life events, and exposure to family violence in early adolescence, were all linked to perpetration of maltreatment as an adult. Late adolescent risk factors for subsequent engagement in maltreatment included parental conflict and parental alcohol use (Thornberry et al., 2014). Similarly, parent criminality has been identified as a risk factor related to youth delinquency (Lederman, Dakof, Larrea, & Li, 2004; Leve & Chamberlain, 2004), which in turn is associated with heightened risk for the perpetration of maltreatment. Family contextual risks, including parent criminality, can also affect the resources available to parents, which ultimately can affect the parenting a child receives. Further, the presence of multiple contextual risk factors appears to have a cumulative effect on the perpetration of maltreatment (Thornberry et al., 2014), suggesting the importance of incorporating multiple domains of family contextual risk into our theoretical model of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment. The accumulation of risk in multiple domains is likely to overwhelm an individual’s coping abilities and, therefore, may have the largest impact on predicting maltreatment (Thornberry et al., 2014). Given the prior literature on the association between family contextual risks and perpetration of maltreatment, as well as the evidence surrounding cumulative nature of family contextual risks (Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen, & Sroufe, 2004; Thornberry et al., 2014), we examine the influence of a composite family risk index on the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

Individual Risk: Delinquency

Delinquency has well-established associations with child maltreatment, but it is a complex risk factor because of its reciprocal nature of influence—it has been shown to be both a risk factor for engaging in maltreatment (e.g., Thornberry et al., 2014) as well as a potential outcome of the experience of maltreatment (e.g., Widom, 2013). The evidence surrounding the positive association between childhood maltreatment and female delinquency is vast, with numerous studies indicating that adolescent girls in the juvenile justice system are more likely than their male counterparts to have been victims of sexual and/or physical abuse (e.g., Cauffman, Feldman, Waterman, & Steiner, 1998; Moore, Gaskin, & Indig, 2013; Zahn et al., 2010). In addition, adjudicated girls and those at-risk for adjudication with a history of sexual abuse tend to have more extreme delinquency outcomes than those without such a history (Goodkind, Ng, & Sarri, 2006; Wareham & Dembo, 2007). Further, delinquency is also a commonly reported outcome among individuals who were maltreated as children. For instance, children with histories of physical abuse are found to be at greater risk of being arrested in adolescence for both violent and nonviolent crimes compared to those without abusive pasts (Lansford et al., 2007). Overall, girls who are exposed to abuse or interparental violence during childhood are more than 7 times as likely as control girls (selected from an age-matched community sample who had not been exposed to marital violence) to commit a violent act that is referred to the juvenile justice system (Herrera & McCloskey, 2001). The association between child maltreatment and delinquency remains strong across different methods of assessment, including self-report and formal records (Smith, Ireland, & Thornberry, 2005).

Engaging in delinquent behaviors in adolescence is subsequently linked to perpetration of maltreatment as an adult (Thornberry et al., 2014). For example, Colman and colleagues (2010) found that 62% of the girls who had been released from juvenile justice facilities were investigated by child protective services at least once as an alleged perpetrator of abuse and neglect before age 28. Forty-two percent of them had a confirmed case of perpetration of child maltreatment and 68% of those investigated were implicated in two or more cases during the 12-year study period, with a mean of 3.95 investigations per study female. Similarly, Thornberry et al. (2014) found that adolescent general delinquency behaviors were associated with an odds ratio of 1.56 for perpetration of maltreatment in adulthood, supporting the argument that juvenile delinquents are at an increased risk for placing their children in vicious cycles of system involvement and health disparities. These cyclical intergenerational effects appear to be more pronounced in girls; the Colman et al. (2010) study noted above found that girls involved in the juvenile justice system were approximately 3.5 times more likely than their male counterparts to be identified as a perpetrator of child abuse and neglect during young adulthood. For these reasons, in the current study we focus on female youth who had been involved in the juvenile justice system for serious delinquency during adolescence, and include measures of delinquent engagement across a two-year period during adolescence to examine its association with perpetration of maltreatment in young adulthood.

Partner Risk: The Microsystem

Young adulthood is known to be a challenging developmental period, with prevalence rates of several health risking behaviors (e.g., substance use and unprotected sex) peaking during this stage (Arnett, 2000). Young women with histories of juvenile justice involvement are found to be at particular risk for making unhealthy partner choices (Oudekerk & Reppucci, 2010), making them more prone to involvement in negative behaviors including perpetration of maltreatment (Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002). For example, women who were involved in the juvenile justice system as youth were more likely to select partners who engaged in antisocial or violent behavior (Oudekerk & Reppucci, 2010). There is also evidence that partner choice and relationships during young adulthood can be influenced by prior maltreatment experiences. For example, significant associations between self-reported receipt of physical punishment or maltreatment in childhood and negative partner relationships, partner social adjustment problems, and experiences of intimate partner violence in adulthood were identified in a birth cohort study of more than 900 individuals in New Zealand (McLeod, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2014). These relationships, however, were significant only for females, not for males (McLeod et al., 2014).

Partner behaviors, such as drug use and criminality, can have a strong influence on the behavioral choices of young women with histories of delinquency. For instance, in a previous report using the same sample as reported on here (women with prior juvenile justice involvement and out-of-home placement), we found that women’s drug use was significantly related to her partners’ use (Rhoades, Leve, Harold, Kim, & Chamberlain, 2014). Similarly, Bright, Ward, and Negi (2011) conducted a qualitative study and found that women with a history of juvenile justice involvement indicated a close link between her substance use and either her intimate partner’s or a family member’s drug use. Further, women with history of juvenile justice involvement were more likely to date partners who were involved in antisocial behaviors (Cauffman, Farrugga, & Goldweber, 2008). This constellation of risky behaviors—exposure to maltreatment, family contextual risk, delinquency, and partner risk behavior—are intricately linked, making it important to investigate these links using longitudinal designs and rich measurement approaches. Within our multilevel framework, we investigate the role of partner risk behaviors (a microsystem influence) on the intergenerational continuity of maltreatment by including a composite measure of partner risk, comprised of criminality and drug use indicators.

Measurement Issues in the Study of Maltreatment

As noted by others (e.g., Cicchetti, 2004; Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Thornberry et al., 2012), the measurement of maltreatment is important to consider in any study examining intergenerational transmission patterns given the variability in measurement approaches and the subsequent variability in findings. Researchers often do not have the ability to utilize a prospective design, and thus rely on self-report, archival child protective system records, or a mixture of both. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses. Self-report studies are especially vulnerable to the social desirability bias. This is particularly a concern when self-report data are used to measure both retrospective recollections of maltreatment as well as perpetration of maltreatment. The utilization of official child welfare records avoids this limitation, but only captures what has been successfully reported to child protection authorities (Widom, Czaja, & DuMont, 2015). A more rigorous approach is to collect official maltreatment records and code them using the Maltreatment Classification System (Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993), rather than relying on the dispositional status from the case file. The MCS uses all information available from the case record, and a team of trained staff code the file, thereby allowing for an independent determination of maltreatment experiences and classification by maltreatment subtype, severity, frequency, and developmental period of each event. Despite these advances in coding official records, Widom and colleagues (2015) note that there exists no “gold standard” for measuring child maltreatment, which may partially explain the large variance in measurement approaches seen in the extant literature. Notable but rare are prospective longitudinal studies that use a combination of official records and interview data, across both maltreated and control samples (e.g., Kim-Spoon, Cicchetti, & Rogosch, 2013).

In an effort to examine potential variations in findings associated with different measurement approaches, Widom et al. (2015) examined self-report, official child welfare records data, and self-report of the children (third generation) in order to examine intergenerational transmission effects. They found clear measurement differences: the extent of the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment largely depended on the source of information used. Specifically, women with a history of child welfare system (CWS) involvement were significantly more likely to be reported to child welfare authorities for perpetration of child maltreatment, however, they did not self-report more maltreatment than matched comparisons. The authors suggest that this measurement artifact may be the result of a surveillance bias, with individuals who have previously been in the system garnering higher levels of surveillance than those who have not been in the system. These findings suggest the grave importance of attending to the issue of measurement in studies of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment before drawing conclusions about continuity across generations.

The Current Study

In this study, we sought to apply a multilevel approach to the study of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment by examining multiple levels of predictors (family contextual risk, adolescent delinquency, and partner risk), and examining the perpetration of maltreatment across multiple modes of assessment. Our sample included women who had been removed from the care of their parent(s) as teenagers, had been involved in the juvenile justice system, and were assessed longitudinally into young adulthood. Eighty-five percent of the sample had a substantiated incident of maltreatment during childhood and all had experienced at least one out-of-home care placement and significant family adversity. Using the transactional ecological model of maltreatment (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), we hypothesized that a cumulative family contextual risk index, a multi-wave, multi-measure construct of adolescent delinquency, and young adult partner risk would each independently predict whether participants would show intergenerational continuity of maltreatment. We also examined interactions between levels of the social ecology. Within these models, we sought to explore whether intergenerational associations would vary as a function of how the perpetration of maltreatment was measured by including three different modes of measurement: official child welfare records, self-reported child welfare contact, and self-reported maltreatment chronicity as indexed by a standardized questionnaire. Finally, because the sample participated in a randomized trial that was aimed at preventing recidivism during adolescence, we examined whether there were any long-term effects of the intervention on the perpetration of maltreatment in young adulthood.

Method

Participants

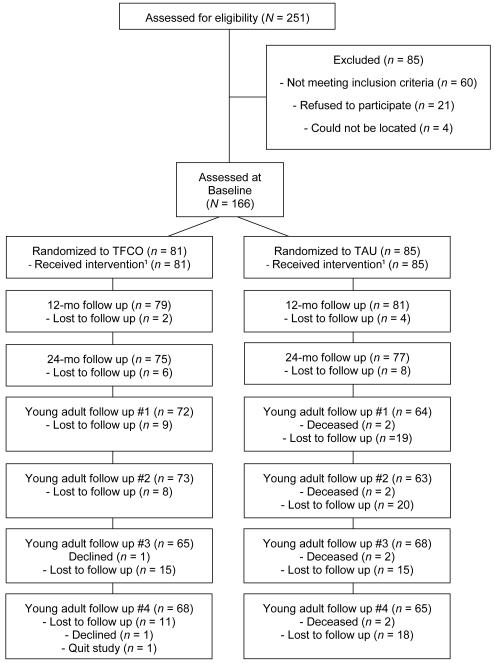

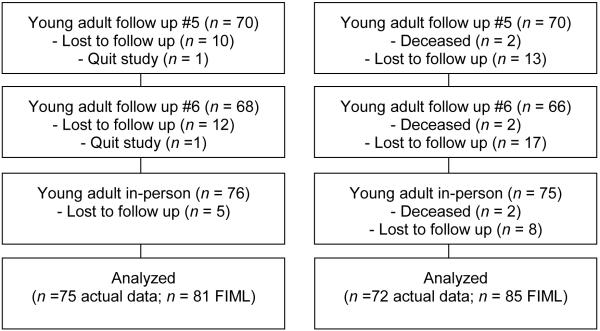

The study sample included 166 women, baseline age 13–17 years (M = 15.31, SD = 1.17), who participated in one of two consecutively run randomized controlled trials contrasting Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO; formerly known as Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care) and out-of-home treatment as usual (TAU), which was typically a group care residential facility. The trial was conducted from 1997–2006, with Cohort 1 n = 81 and Cohort 2 n = 85. Participants were followed for approximately 10 years. The girls had been referred by Oregon juvenile court judges during the study period and had been mandated to community-based, out-of-home care because of problems with chronic delinquency and serious family adversity. Enrollment was consecutive and based on when girls were court-mandated to out-of-home care. We attempted to enroll all referred girls who were 13–17 years of age, had at least one criminal referral in the past 12 months, were placed in out-of-home care within 12 months following referral, and were not currently pregnant. Enrolled girls were randomly assigned to the treatment condition (TFCO; ns = 37 and 44) and control condition (TAU; ns = 44 and 41) for Cohorts 1 and 2, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of participant flow through study recruitment, randomization to Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFC) or treatment as usual (TAU), and follow-up assessments. A superscript “1” indicates that some treatment services were received by all youth, though treatment length varied.

The ethnic breakdown of participants was as follows: 68.1% Caucasian, 1.8% African American, 11.4% Hispanic, 0.6% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 16.9% mixed ethnic heritage. Less than 1% reported other or unknown ethnicity. Ethnicity was reported by participants at the first young adult assessment; note that these percentages differ slightly from those in some earlier published reports due to the self-report (vs. caregiver report) nature of the data used here. In comparison, 93% of the girls 13–19 years of age living in the region at the time this study was conducted were Caucasian (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1992). At baseline, 63% of girls had been living in single-parent family homes, and 54% of these families had an annual income of < $10,000. All girls had been removed from their parent(s) and placed in out-of-home care settings. The vast majority of girls had a formal record of child welfare involvement for maltreatment and/or neglect, with current caseworkers reporting a history of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and/or severe family violence for 85.5% of girls. No group differences were observed in the rate or type of pre-baseline offenses or demographic characteristics.

Procedures

Prior to entering her out-of-home placement, each girl and her parent (or other primary pre-placement caregiver) completed an in-person, 2-hr baseline assessment. Research assistants responsible for data collection and data entry were blind to participants’ group assignment and were not involved in delivering the intervention. In-person follow-up assessments were conducted at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months post-baseline, and once during young adulthood, approximately 8 years post-baseline (M = 8.36 years post-baseline, SD = 2.47). In addition, a series of six telephone interviews was conducted during young adulthood, occurring once every 6 months over a 2.5-year period, inclusive of the time the participant completed her in-person young adult assessment. One hundred and fifty-two participants (92.6% of the 164 participants still living) completed at least one of these young adult follow-up assessments (in-person or a phone). The young adult follow-up assessments began at means (SD) of 9.81 (1.73) and 4.69 (1.16) years post-baseline for Cohorts 1 and 2, respectively. Juvenile justice court records were collected during each in-person adolescent assessment and CWS records about the participant as perpetrators in young adulthood were collected at the final young adult follow-up assessment, approximately 10 years post-baseline (M = 10.01 years post-baseline, SD = 2.96). The baseline, 12-month, 24-month, and 8-year in-person assessment data, the young adult telephone interview data, the young adult child welfare records data, and the juvenile courts records data were utilized in this study. No adverse events were reported during the course of the study.

Experimental Intervention

The TFCO intervention is described in detail elsewhere (Chamberlain, 2003; Chamberlain, Leve, & DeGarmo, 2007; Leve, Chamberlain, Smith, & Harold, 2011). TFCO girls were individually placed in one of 22 highly trained and supervised homes with state-certified foster parents. Across the years that the trial was conducted, each TFCO home served 1–19 study participants (M = 3.68, SD = 4.53). Experienced program supervisors with small caseloads (10 TFCO families) supervised all clinical staff, coordinated all aspects of each youth’s placement, and maintained daily contact with TFCO parents to monitor treatment fidelity and provide ongoing consultation, support, and crisis intervention services. Interventions were individualized but included all basic TFCO components: daily telephone contact with the foster parents to monitor case progress and adherence to the TFCO model; weekly group supervision and support meetings for foster parents; an individualized, in-home, daily point-and-level program for each girl; individual therapy for each girl; family therapy (for the aftercare placement family) focusing on parent management strategies; close monitoring of school attendance, performance, and homework completion; case management to coordinate the interventions in the foster family, peer, and school settings; 24-hr on-call staff support for foster and biological parents; and psychiatric consultation, as needed. In Cohort 2, the TFCO condition also included intervention components that targeted sexual-risk behaviors and substance use behaviors.

Control Condition

TAU girls were placed in one of 35 community-based program sites located in Oregon. TAU programs represented typical services for girls being referred to out-of-home care by the juvenile justice system, which were primary group care residential placements. The programs had 2–83 youths in residence (M = 13) and 1–85 staff members (Mdn = 9). The program philosophies were primarily eclectic (61.5%) or behavioral (38.5%); 80% of the programs reported delivering weekly therapeutic services.

Measures

Outcome Variables

Committing one or more acts of child maltreatment by the study participants was assessed during the young adult assessments, conducted approximately 8–10 years post-baseline, using two self-report measures, and at the conclusion of all assessments (September 2012; approximately 10 years post-baseline) using official CWS records data. Each of the three maltreatment measures is described below.

Official CWS records

Official maltreatment records were obtained from the Oregon Department of Human Services, Children, Adults and Families Division at the conclusion of the final young adult assessment. Participants who had an official child welfare record with one or more substantiated maltreatment incidents against them for at least one child were assigned a score of 1; those without a record were assigned a score of 0.

Self-reported CWS contact

At each of the six phone assessments during young adulthood, participants were asked to self-report their own contact with the CWS for suspected abuse or neglect of any of their children. The question was asked separately about each child. Those who responded affirmatively for at least one child at any of the 6 assessment waves were assigned a score of 1; those without a self-reported history of CWS contact were assigned a score of 0.

Self-reported maltreatment chronicity

At the in-person young adult assessment, participants’ completed the Conflict Tactics Scale, Parent-Child version (CTS; Strauss, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Mean chronicity of physical assault (5 items) and neglect (5 items) was assessed by summing the frequency of items endorsed in each category for the past year. Mean chronicity scores were then computed by dividing the sum of frequency scores by the total number of items that were answered. To obtain a total chronicity score, we summed the individual mean chronicity scores for the two maltreatment categories.

Predictor Variables

Predictor variables included risk factors associated with intergenerational transmission of maltreatment across three levels of the individual’s social ecology: family context, individual characteristics, and partner characteristics.

Family contextual risk

At the baseline assessment, the girl’s Department of Youth Services caseworker responded to a survey about the girl’s exposure to family context-level risk factors by answering yes or no to each of the following eight items: single family at present, current family income < 10,000, parents divorced during lifetime, 3 or more siblings or step-siblings, any parent (biological/step/adoptive) hospitalized for mental illness, any parent (biological/step/adoptive) convicted of crime, any sibling placed in out-of-home care, and family violence in the home (weapons used or arrested for or victim of). The family contextual risk composite was calculated by summing the eight individual risk scores, and ranged from 0 (no risk factor present) – 8 (all eight risk factors present).

Adolescent delinquency

A multiple-method delinquency measure was computed at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months from three indicators that assessed delinquent behaviors occurring during the prior 12 months: number of criminal referrals, number of days in locked settings, and self-reported delinquency (Chamberlain et al., 2007). Criminal referrals were collected from state police records and circuit court data, which have been found to be reliable indicators of externalizing behavior (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999). The number of days spent in locked settings was measured by girls’ report of total days spent in detention, correctional facilities, jail, or prison over the past 12 months. Self-reported delinquency was measured with the Elliott General Delinquency Scale (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985); this 21-item subscale records the number of times girls report violating laws during the preceding 12 months. The three delinquency indicators were significantly correlated with each other. A principal components analysis revealed a single factor solution at each wave with eigenvalues ranging from 1.5–1.6 and loadings ranging from 0.44–0.82. An adolescent delinquency score was calculated at each wave by rescaling each continuous indicator from 0 to 1 and then averaging them. Criminal referrals and days in locked settings were log transformed before rescaling to correct for distributional skewness and kurtosis. Delinquency scores across time were significantly correlated, rs = 0.36–0.50, p < 0.001. The final adolescent delinquency score was computed by averaging delinquency scores from the baseline, 12-month, and 24-month assessments.

Partner risk

During each of the six young adult telephone assessments, women were asked to report, for up to 4 recent partners, their partners’ (1) use of marijuana (Y/N) and (2) illicit drug use (Y/N) in the past 6 months, and (3) if the partner had ever been arrested in his/her lifetime (Y/N). For each risk factor, participants were assigned a score of 1 if the risk factor was present for any partner at any wave. All women had at least one partner during at least one assessment wave. Only those telephone interviews that occurred at or prior to the in-person assessment (when the CTS maltreatment measure was collected) were used in analyses, to preserve the sequential ordering of the predictor and outcome variables. The partner risk composite was computed by summing the individual risk scores, and ranged from 0 (no risk factor present) – 3 (all three risk factors present).

Controls

All models included an examination of potential intervention effects (0 = TAU, 1 = TFCO) and age at the final young adult assessment (when the CWS records were collected).

Analytic Plan

We used separate logistic regression analyses to predict perpetration of maltreatment for the two categorical outcomes, i.e., official CWS records and self-reported CWS contact, and ordinary least squares regression for the continuous outcome of CTS maltreatment chronicity. Independent variables were added in blocks with the control variables entered first, followed by our predictor variables. Interaction effects were explored for all key independent variables. Analyses were conducted in Mplus v7 using robust estimation procedures to account for any violations of normality.

Missing data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) under the missing at random (MAR) assumption. Missing data were present only in case of the partner risk variable, with 11% of the sample having missing values (due to failure to complete the in-person assessment, or a participant choosing to skip the partner items). A dummy variable was created to indicate missingness on the partner risk variable, and was correlated with the key study variables and sample demographics. Participants with missing data did not differ significantly from those with complete data on any of these variables, suggesting that missing data were ignorable and use of FIML was appropriate (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables included in the analytical models are reported in Table 1. Nearly one-third of the sample (n = 50) had a substantiated CWS record for at least one child. Approximately the same number of participants (n = 53) also self-reported CWS contact. Nevertheless, the correlation between the two variables was only 0.51. CTS self-reported maltreatment chronicity was significantly associated with self-reported CWS involvement (r = 0.20, p < 0.05), but not with official CWS records, suggesting the possibility of shared method variance.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix of Study Variables

| Variable Names (Range) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Official CWS record of maltreatment (0-1) | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. Self-reported CWS contact (0-1) | 0.51*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. CTS maltreatment chronicity (0-11) | 0.03 | 0.20** | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. Family contextual risk (0-8) | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. Adolescent delinquency (0-0.7) | 0.20** | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |||

| 6. Partner risk (0-3) | 0.19* | 0.17* | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 1.00 | ||

| 7. Intervention assignment (0-1) | −0.12 | −0.07 | −0.14+ | −0.01 | −0.14+ | −0.06 | 1.00 | |

| 8. Age at follow-up (19-32) | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.37*** | 0.05 | 1.00 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.30 (0.46) |

0.32 (0.47) |

0.82 (1.99) |

3.88 (1.79) |

0.30 (0.14) |

1.67 (0.95) |

0.49 (0.50) |

25.39 (3.10) |

p < .08.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Bivariate analyses revealed partner risk to be significantly associated with both official CWS records and self-reported CWS involvement. Adolescent delinquency was only associated with official CWS records, and family contextual risk was not significantly associated with any of the three maltreatment outcomes. Overall, none of the predictor variables was significantly correlated with the CTS maltreatment chronicity outcome. Two trends were also noted at the bivariate level: assignment to the TFCO intervention group was associated with lower CTS maltreatment chronicity and lower adolescent delinquency. The later association was anticipated based on the previously-reported intervention effect on adolescent delinquency (Chamberlain et al., 2007); although in this study, we also include baseline delinquency in our delinquency construct to examine its effect on later perpetration of maltreatment, and therefore did not specifically hypothesize intervention effects for the delinquency composite. Finally, a significant inverse correlation between partner risk and age at follow-up was also noted, with younger women reporting more partner risk.

Consistent with the bivariate linkages, regression analyses revealed that both adolescent delinquency, β (SE) = 1.80 (0.76), p < 0.05, and partner risk, β (SE) = 0.35 (0.11), p = 0.001, were significant predictors of official CWS child maltreatment records (see Table 2). Participants who engaged in delinquent behaviors during their adolescent years and those who had a high-risk partner in young adulthood were significantly more likely to have an official CWS record. Age at follow-up was also a significant predictor of official CWS records, β (SE) = .09 (0.03), p < 0.01, with older age associated with greater likelihood of an official CWS record.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients and Standard Errors Associated With Model Pathways (N = 166)

| Outcome Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Official CWS record |

Self-reported CWS contact |

CTS maltreatment chronicity |

|

| Predictor Variables | |||

| Family Contextual Risk | −0.01 (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.07) |

| Adolescent Delinquency | 1.80 (0.76)* | −0.09 (0.74) | −0.06 (0.06) |

| Partner Risk | 0.35 (0.11)*** | 0.22 (0.11)* | 0.10 (0.07) |

| Controls | |||

| Intervention assignment | −0.25 (0.21) | −0.20 (0.20) | −0.15 (0.07)* |

| Age at follow-up | 0.09 (0.03)** | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.08) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.01.

Having a high-risk partner was also associated with a higher likelihood of self-reported CWS involvement, β (SE) = 0.22 (0.11), p < 0.05. There were no other significant predictors of self-reported CWS involvement. Finally, intervention assignment was a significant predictor of CTS maltreatment chronicity, β (SE) = −.15 (0.07), p < 0.05, indicating that women who previously were randomly assigned to the TFCO intervention had lower self-reported CTS maltreatment chronicity. None of the other predictor variables significantly accounted for the variation in CTS maltreatment chronicity scores. In addition, family contextual risk did not emerge as a significant predictor of any of the three indicators of child maltreatment. None of the interaction effects were significant. Overall, our models explained 19% of variance in the official CWS record outcome, 5.9% variance in self-reported CWS involvement, and 3.4% variance in the CTS maltreatment chronicity.

Discussion

We sought to examine factors related to the intergenerational continuity of maltreatment from a multilevel perspective in a sample of young women who had been removed from the care of their parent(s) as teens, and had experienced maltreatment and/or chronic adversity in childhood. We examined three levels of predictors in the social ecology—family contextual risk, individual risk (adolescent delinquency), and young adult partner risk—and examined associations across three different modes of assessment of the perpetration of maltreatment during young adulthood. Our results indicated that there were only weak to modest associations between self-reported CWS involvement, self-reported maltreatment, and official CWS records, and that different patterns of predictors emerged as a function of the measurement mode used to assessment perpetration of maltreatment.

The lack of a robust pattern of associations between the three measures of maltreatment has been noted in past studies (e.g., Widom et al., 2015) and poses a challenge for the field. In this study, the correlations between the three measures of maltreatment ranged from .03–.51, suggesting that a different core construct was being measured in each instance. To some extent, the lack of stronger associations is not surprising—reporting biases may cause women to over- or under-report their own involvement in the CWS, and specific neglectful and physically assaultive parenting practices may not meet the same definitional threshold for “maltreatment” as do substantiated events that have been acted upon by the child welfare service sector. Nonetheless, the diversity of measurement approaches used in prior studies in the field, the lack of an agreed upon gold standard for measurement, and the differential prediction patterns in this study gives pause for concern about the translation of findings from any given study to the delivery of evidence-based interventions. Are we over- or under-identifying individuals most at risk for intergenerational continuity? The answer to this question depends on the type of maltreatment assessment used and the specific risk factors examined. In the present study, 30–32% of the sample engaged in perpetration of maltreatment as a young adult when relying on any single indicator (official records or self-reported CWS contact). When endorsement of either self-reported CWS contact or official CWS records is used as the marker to maltreatment, 42% of the sample showed a pattern of intergenerational continuity. Thus, the specific individuals identified as showing intergenerational continuity varied as a function of the measurement instrument used.

In addition, the risk factors showed a different pattern of prediction as a function of the outcome measure used. When examining official CWS records, both adolescent delinquency and partner risk were associated with later perpetration of child maltreatment. However, when self-reported CWS contact was the outcome of interest, partner risk was the only significant predictor. Consistent with the findings from Widom and colleagues (2015), this pattern of associations may indicate a system surveillance issue: individuals who have had high contact with the juvenile justice system (i.e., are highly delinquent) may be more likely to fall under the surveillance of child welfare authorities at levels that exceed their counterparts who are engaging in similar parenting behaviors, but do not have as extensive of a history of delinquency and juvenile justice involvement. A question that cannot be addressed in this study is whether the potential surveillance difference results in overly aggressive decision-making for dual-system involved women, or whether heightened surveillance would be beneficial to prevent future harm to the children of women who have been less involved in the juvenile justice system. In the case of both official records and self-reported CWS contact, partner risk emerged as a significant predictor, suggesting the potential utility in implementing evidence-based interventions that include a partner focus in future prevention work, as is further discussed below.

In contrast, CTS maltreatment chronicity was not significantly associated with any of the three hypothesized risk factors. There are a variety of explanations for this lack of significance, including the likelihood that the neglect and physical assault items included on the CTS may not rise to the level of “maltreatment” (even though this measure is commonly used as a measure of maltreatment), and even when they do, there is a difference between parenting acts that come to the attention of the child protective services and parenting behaviors that are serious and harmful nonetheless but that escape the attention of teachers, neighbors, relatives, or others who would file an official report with child welfare authorities. In addition, because the CTS is a self-report measure, participants may have underreported on parenting practices reflective of abusive parenting, and the reporting period only covered the 2.5 years spanning the young adult telephone assessments. In contrast, the official CWS records measured participants’ lifetime perpetration of maltreatment.

Of note, however, is the significant intervention effect on CTS maltreatment chronicity: women originally assigned to the TFCO condition reported lower levels of maltreatment chronicity than women assigned to the TAU condition. The TFCO intervention involves placing a youth in a well-trained and supported foster home for a period of approximately 6 months. It may be that this family living experience, where the youth is parented by an effective and well-trained foster parent, helps provide a positive role model for women as they enter young adulthood and begin to form families of their own. In contrast, the TAU youth received a group care based intervention, and therefore did not have an opportunity to experience the same highly structured and supported family-like environment as TFCO youth. This experience during the formative adolescent years may have affected women’s own parenting behaviors as young adults, and led to the significant intervention effect identified in this study.

Prior reports from this study have identified intervention effects on trajectories of drug use (Rhoades et al., 2014) and depressive symptoms (Kerr, DeGarmo, Leve, & Chamberlain, 2014) in young adulthood, which may be alternative proximal mechanisms associated with the lower trends for maltreatment chronicity in the TFCO group. In support of this notion, a mediated pathway from maternal history of sexual abuse to substance use problems to offspring victimization was identified in a large community-based study of mothers and their young children (Appleyard, Berlin, Rosanbalm, & Dodge, 2011). The current findings, as well as the Appleyard et al. (2011) findings, offer support for the supposition that substance use problems may be an important behavior to target in the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

Intervention Implications

In addition to the positive benefits of the TFCO intervention on maltreatment chronicity, the current findings have implications for the development and delivery of additional preventive intervention approaches. First, we found that partner risk (a composite score comprised of partners’ marijuana use, other illicit drug use, and criminal behavior) was significantly associated with official CWS records and with self-reported CWS contact. This suggests a potential opportunity for intervention (or prevention) by identifying women who have been maltreated, and delivering intervention services specifically designed to help them make healthy partner choices and improve the quality of their partner relationships. Because intimate relationship patterns are established early in development, beginning with the parent-child relationship and development of the attachment system, timing interventions aimed at establishing healthy romantic partner relationships to be delivered during adolescence may be more effective than waiting until adulthood. There are a number of school-level, family-level, and group-level interventions that have shown promising evidence for the development of adaptive partner relationships and the prevention of teen dating violence (http://www.nij.gov/topics/crime/intimate-partner-violence/teen-dating-violence/pages/prevention-intervention.aspx). These could be useful directions to pursue among populations of teenage girls who have experienced the dual systems of the CWS and the juvenile justice system. In addition, there are evidence-based relationship-based approaches focused on the mother-child attachment relationship that might be appropriate for women who have already given birth and are parenting. For example, child-parent psychotherapy has been shown to lead to improvements in attachment security among children in a maltreated sample (Cicchetti, Rogosch & Toth, 2006).

During young adulthood, interventions that include a dual focus on the couple relationship and parenting may be particularly beneficial. Cowan and Cowan (2008) found that the inclusion of dual couple and parenting components resulted in positive outcomes for both children and parents. Knox, Cowan, Cowan and Bildner (2011) reviewed interventions that strengthen fathers’ involvement and family relationships, with a particular focus on fatherhood programs aimed at disadvantaged noncustodial fathers and relationship skills programs for parents who are together. They found that fatherhood programs have some efficacy in increasing child support payments, and that some relationship skills approaches have benefits for the couples’ relationship quality, coparenting skills, fathers’ engagement in parenting, and children’s well-being. Together, this work suggests that women’s relationship with her partner should be a fundamental consideration in future programs aimed at reducing intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

In addition, given the significant association between adolescent delinquency and subsequent perpetration of child maltreatment as shown by official CWS records, it is important to continue to deliver interventions aimed at preventing girls’ involvement in the juvenile justice system. At least four empirically validated, evidence-based interventions for juvenile justice–involved youths have been tested with girls, including Functional Family Therapy (Alexander & Parsons, 1982), Multisystemic Therapy, Multidimensional Family Therapy (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2009), Treatment Foster Care Oregon (Chamberlain, 2003), and Multidimensional Family Therapy (Liddle, Rodriguez, Dakof, Kanzki, & Marvel, 2005). Each has been shown to be effective in preventing subsequent delinquency and related problems in girls, and during the past decade, these four evidence-based practices have had an increased presence in routine care of youth in juvenile justice (Henggeler & Schoenwald, 2011). However, recent surveys indicate that only 9% of youths per year in the United States are served by one of these four interventions, or about 15,000 of 160,000 juvenile justice-involved youths (Henggeler & Schoenwald, 2011). This speaks not only to the feasibility of implementing research-based programs in community settings but also to the need to expand the reach of these effective programs and to develop new implementation models, to ultimately help reduce rates of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

Limitations and Future Directions

In addition to the strengths and weaknesses related to each of the maltreatment measures noted earlier, other design issues warrant consideration. First, the women in this study were, on average, 23–25 years old when the three outcome assessments were collected. Although teens and women under 25 have high rates of perpetrating child maltreatment (http://www.datanetwork.org/viz/risk), studies show that women age 25–34 comprise the largest group of perpetrators (Finkelhor et al., 2013), with 82% of perpetrators being between the ages of 18 and 44 years (Finkelhor et al., 2013). If we had access to longer-term follow-up assessment data, additional cases of maltreatment may have been reported, either by CWS records or by self-report, because women in this study have not yet passed the period of risk for maltreating their child. Therefore, data collection in 10 or 15 years would yield a more complete picture of the predictors of intergenerational transmission of maltreatment.

Second, only females were assessed in this study. Although the data on perpetrators suggest that men and women engage in maltreatment in approximately equal rates (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), there is evidence that the effects of some forms of maltreatment may vary by sex. For example, one study indicated that men evidence reduced hippocampus volume as a function of childhood emotional abuse, but not women (Samplin, Ikuta, Malhotra, Szeszko, & Derosse, 2013). However, despite this neurobiological difference, emotional abuse was associated with higher levels of subclinical psychopathology in both men and women, suggesting that both sexes suffer from behavioral symptoms associated with childhood maltreatment (Samplin et al., 2013). In addition, physical abuse in childhood has been shown to be significantly related to the onset of mental health conditions in adulthood for women, but not for men (Thompson, Kingree, & Desai, 2004). Because women tend to have a primary parenting role more often than men, the vast majority of research on the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment has focused on samples of women. Given the possible sex differences in both the outcomes of maltreatment and the prevalence rates of different forms of maltreatment (Asscher, Van der Put, & Stams, 2015), additional longitudinal research that examines intergenerational patterns of maltreatment among men is needed.

This study only included women who had been removed from the care of their parent(s) and placed in out-of-home care as adolescents. The majority of the sample (85%) had at least one substantiated maltreatment incident during childhood, and all women were involved in the juvenile justice system. We lacked a comparison group of age-, ethnicity-, and socioeconomic status-matched girls to examine potential differential prediction to perpetration of maltreatment among a cohort of women who had not been maltreated as children and had not been involved in an out-of-home placement. Our sample had extremely high levels of problems on all three predictors, with an average of nearly 4 family contextual risks, 12 prior criminal referrals for delinquency, and with 82% of the sample reporting that one of their partners had been arrested at least once. Although the variable distributions approximated normality, the sample as a whole falls on the right (higher) end of the distribution and we did not have women without maltreatment histories, low rates of contextual risk, low teen delinquency, and drug- and crime-free partners in the study. Including a comparison sample with these more normative features may have yielded different associations between our risk factors and the maltreatment outcomes, and is an important avenue for future research.

Additionally, our measure of partner risk was limited by the fact that we relied on young women’s self-report of partner drug use and delinquency, rather than having access to partner’s self-report data. Further, in constructing the partner risk measure we only included data from the telephone interviews that were collected prior to or at the same time as the in-person assessment to preserve the sequencing of this predictor and our CTS outcome measure (which was collected during the in-person assessment). The in-person assessment occurred anywhere across the first to the sixth telephone interview, and thus some women had more data to aggregate in this measure than others. Having additional data points on partner risk for all participants may have yielded a different pattern of associations.

Although a strength of our approach was the inclusion of multiple methods of measuring maltreatment, this approach did not allow us to distinguish among different forms of abuse (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, emotional abuse), or factors such as age of first incident and severity of any given incident. Use of the MCS (Barnett et al., 1993) would have allowed us to delve deeper into questions related to specific type of maltreatment, and issues related to maltreatment severity and chronicity. Our CTS measure did capture chronicity, but only via self-report and our other two measures were categorical (yes/no). Extant research has shown that all forms of maltreatment can have deleterious behavioral health impacts (e.g., Norman, Brambaa, Butchart, Scott, & Vos, 2012), but it is also clear that maltreatment subtypes may yield distinct effects (e.g., Mendle, Leve, Van Ryzin, Natsuaki, & Ge, 2011; Nikulina, Widom, & Brustowicz, 2012; Pears, Kim, & Fisher, 2008; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012). For example, some studies suggest that experiencing abuse during childhood is a stronger predictor for victimization of future children than experiencing neglect (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011). Additional insights could be gained in future research by attending to the different types of maltreatment, as well as factors such as chronicity and onset.

Finally, this study accounted for only a modest amount of the variance in perpetration of maltreatment, regardless of which measure was examined. The model examining official CWS records accounted for the most variance (19%) of all our models, which still leaves a large amount of variance unaccounted for. In fact, when using the generous criteria of perpetration of maltreatment on either self-reported CWS contact or official records, only 42% of the women in this study had involvement with the CWS for maltreatment of their child. This suggests that half the sample was successful in breaking the pattern of intergenerational continuity, despite having experienced maltreatment as a child (as well as a host of other risk factors such as juvenile justice involvement and removal from the one’s parents). As recommended by Cicchetti (2013), the field needs to turn its attention to multilevel studies that examine the contributors to resilient functioning to enhance our understanding of why some individuals are able to develop into well-adjusted, non-maltreating parents despite their own experiences of childhood maltreatment.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Oregon Youth Authority and by grants R01 DA024672, R01 DA015208, and P50 DA035763 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and by grant R01 MH054257 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), NIH, U.S, PHS. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Patricia Chamberlain from the Oregon Social Learning Center for her leadership as Principal Investigator of the original studies and developer of Treatment Foster Care Oregon, Sally Guyer for data management, Courtney Paulic and Priscilla Havlis for project management, Michelle Baumann for editorial assistance, the team of interviewers and data management staff, and the study participants, parents, case workers, and foster parents.

Footnotes

Disclosure of financial interests: No authors have any conflicts to disclose.

References

- Alexander JA, Parsons BV. Functional family therapy. Brookes-Cole; Monterey, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Berlin LJ, Rosanbalm KD, Dodge KA. Preventing early child maltreatment: Implications from a longitudinal study of maternal abuse history, substance use problems, and offspring victimization. Prevention Science. 2011;12(2):139–149. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0193-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MHM, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child outcome behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;46(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asscher JJ, Van der Put CE, Stams GJ. Gender differences in the impact of abuse and neglect victimization on adolescent offending behavior. Journal of Family Violence. 2015;30:215–225. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright CL, Ward SK, Negi NJ. “The chain has to be broken”: A qualitative investigation of the experiences of young women following juvenile court involvement. Feminist Criminology. 2011;6:32–53. doi: 10.1177/1557085110393237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho JCN, Donat JC, Brunnet AE, Silva TG, Silva GR, Fristensen CH. Cognitive, neurobiological and psychopathological alterations associated with child maltreatment: A review of systematic reviews. Child Indicators Research. 2015 Online first. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Farruggia SP, Goldweber A. Bad boys or poor parents: Relations to female juvenile delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescents. 2008;18:699–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Feldman S, Waterman J, Steiner H. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(11):1209–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. Treating chronic juvenile offenders: Advances made through the Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Leve LD, DeGarmo DS. Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for girls in the juvenile justice system: 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:187–193. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. An odyssey of discovery: Lessons learned through three decades of research on child maltreatment. American Psychologist. 2004;59:731–741. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children – past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Aber LA. Abused children-abusive parents: An overstated case? Harvard Educational Review. 1980;50:244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Banny A. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child maltreatment. In: Lewis M, Rudolph K, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 723–741. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry. 1993;56:96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18(3):623–649. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman R, Mitchell-Herzfeld S, Kim DH, Shady TA. From delinquency to the perpetration of child maltreatment: Examining the early adult criminal justice and child welfare involvement of youth released from juvenile justice facilities. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1410–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Diverging family policies to promote children’s well-being in the United Kingdom and United States: Some relevant data from family research and intervention studies. Journal of Children’s Services. 2008;3:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglec. 2012;36:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormond R, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: an update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind S, Ng I, Sarri RC. The impact of sexual abuse in the lives of young women involved or at risk of involvement with the juvenile justice system. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(5):456–477. doi: 10.1177/1077801206288142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-based interventions for juvenile offenders and juvenile justice policies that support them. Society for Research in Child Development: Social Policy Report. 2011;25:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic therapy for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. 2nd Guilford; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera VM, McCloskey LA. Gender differences in the risk for delinquency among youth exposed to family violence. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;25:1037–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Slep AM. Do child abuse and interparental violence lead to adulthood family violence? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe RS, Kempe CH. Child Abuse. London; Fontana: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DC, DeGarmo DS, Leve LD, Chamberlain PC. Juvenile justice girls’ depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation 9 years after Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:684–693. doi: 10.1037/a0036521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability-negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2013;84:512–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox V, Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Bildner E. Policies that strengthen fatherhood and family relationships: What do we know and what do we need to know? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2011;635(1):216–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatmen. 2007;12(3):233–245. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman CS, Dakof GA, Larrea MA, Li H. Characteristics of adolescent females in juvenile detention. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2004;27:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Female juvenile offenders: Defining an early-onset pathway for delinquency. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P, Smith DK, Harold GT. Chapter 9: Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care as an intervention for juvenile justice girls in out-of-home care. In: Miller S, Leve L, Kerig P, editors. Delinquent girls: Contexts, relationships, and adaptation. Springer Press; New York: 2011. pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Rodriguez RA, Dakof GA, Kanzki E, Marvel FA. Multidimensional Family Therapy: A science-based treatment for adoelscent drug abuse. In: Lebow JL, editor. Handbook of clinical family therapy (pp. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 128–163. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod GFH, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Childhood physical punishment or maltreatment and partnership outcomes at age 30. American Orthopsychiatric Association. 2014;84:307–315. doi: 10.1037/h0099807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Leve LD, Van Ryzin M, Natsuaki M, Ge X. Associations between early life stress, child maltreatment, and pubertal development among girls in foster care. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:871–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E, Gaskin C, Indig D. Childhood maltreatment and post-traumatic stress disorder among incarcerated young offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:861–870. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control . Child maltreatment: Facts at a glance. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina V, Widom CS, Brzustowicz LM. Child abuse and neglect, MAOA, and mental health outcomes: A prospective examination. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71(4):350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Brambaa M, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudekerk BA, Reppucci ND. Romantic relationships matter for girls’ criminal trajectories: Recommendations for juvenile justice. Court Review: The Journal of the American Judges Association. 2010;46:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA. Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:958–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Slack KS. Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Understanding intra- and intergenerational connections. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:599–617. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades KA, Leve LD, Harold GT, Kim HK, Chamberlain P. Drug use trajectories after a randomized controlled trial of MTFC: Associations with partner drug use. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:40–55. doi: 10.1111/jora.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samplin E, Ikuta T, Malhotra AK, Szeszko PR, Derosse P. Sex differences in resilience to childhood maltreatment: Effects of trauma history on hippocampal volume, general cognition and subclinical psychosis in healthy adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47(9):1174–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view on the state of the art. Psychological Medicine. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Ireland TO, Thornberry TP. Adolescent maltreatment and its impact on young adult antisocial behavior. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005;29:1099–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(3):345–355. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Kingree JB, Desai S. Gender differences in long-term health consequences of physical abuse of children: Data from a nationally representative survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(4):599–604. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Smith CA, Ireland TO, Greenman SJ, Lee RD. Breaking the cycle of maltreatment: The role of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships. Journal of Adolescent Healt. 2013;53:S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ. Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systemic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma Violence, & Abuse. 2012;13:135–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838012447697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Matsuda M, Greenman SJ, Augustyn MB, Henry KL, Smith CA, Ireland TO. Adolescent risk factors for child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglec. 2014;38:706–722. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce . 1990 census of population: General population characteristics, Oregon. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau . Child Maltreatment. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2012. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wareham J, Dembo R. A longitudinal study of psychological functioning among juvenile offenders: A latent growth model analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34(2):259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Longterm consequences of child maltreatment. In: Korbin JE, Krugman RD, editors. Handbook of child maltreatment. Vol. 2. Springer; Netherlands: 2013. pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, Johnson MS. A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;106(6):1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dumont KA. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Real or detection bias? Science. 2015;347:1480–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1259917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(3):231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015150728887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn MA, Agnew R, Fishbein D, Miller S, Winn DM, Dakoff G, Chesney-Lind M. Causes and correlates of girls' delinquency: Girls study group, understanding and responding to girls' delinquency. U. S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zuravin SJ, McMillen C, DePanfilis D, Risley-Curtis C. The intergenerational cycle of child maltreatment: Continuity versus discontinuity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:315–334. [Google Scholar]