Abstract

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is required for the transmission of all taste qualities from taste cells to afferent nerve fibers. ATP is released from Type II taste cells by a nonvesicular mechanism and activates purinergic receptors containing P2X2 and P2X3 on nerve fibers. Several ATP release channels are expressed in taste cells including CALHM1, Pannexin 1, Connexin 30, and Connexin 43, but whether all are involved in ATP release is not clear. We have used a global Pannexin 1 knock out (Panx1 KO) mouse in a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. Our results confirm that Panx1 channels are absent in taste buds of the knockout mice and that other known ATP release channels are not upregulated. Using a luciferin/luciferase assay, we show that circumvallate taste buds from Panx1 KO mice normally release ATP upon taste stimulation compared with wild type (WT) mice. Gustatory nerve recordings in response to various tastants applied to the tongue and brief-access behavioral testing with SC45647 also show no difference between Panx1 KO and WT. These results confirm that Panx1 is not required for the taste evoked release of ATP or for neural and behavioral responses to taste stimuli.

Key words: ATP, gustatory, mouse, taste buds

Introduction

In taste buds, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a requisite neurotransmitter for the transmission of the signal from taste cells to afferent nerve fibers. Upon taste stimulation, ATP is released from taste cells and activates purinergic receptors containing P2X2 and P2X3 subunits localized on nerve fibers (Bo et al. 1999). These receptors are crucial for taste-evoked transmission because genetic elimination of P2X2 and P2X3 (P2X2/P2X3 DKO) (Finger et al. 2005) or pharmacological inhibition of P2X3-containing receptors (Vandenbeuch et al. 2015) totally abolishes responses to all taste qualities. ATP can also activate neighboring taste cells that express P2X2, P2X4, and P2X7 receptors (Hayato et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2011) as well as P2Y1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 (Baryshnikov et al. 2003; Kataoka et al. 2004; Bystrova et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2009). The role of these receptors on taste cells is unclear although a positive feedback to increase ATP release was suggested (Huang et al. 2009). However, the mechanism by which ATP is released from taste cells is still unclear.

Taste buds consist of 50–100 cells that are classified into 3 groups: Type I cells, also called glial-like cells, wrap around the other cells and possess the NTPDase2 enzyme necessary for ATP degradation of extracellular ATP following its release (Bartel et al. 2006; Vandenbeuch et al. 2013). Type II cells possess the receptors and machinery for sweet, bitter, and umami taste qualities but do not form conventional synapses with afferent nerve fibers. Type III cells form synaptic contacts with nerve fibers and are required for the detection of acids (Huang et al. 2006) and possibly high concentrations of salt (Oka et al. 2013). Among these cells, only Type II cells have been shown to release ATP in response to membrane depolarization (Romanov et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2011) or taste stimulation (Huang et al. 2007, 2011; Dando and Roper 2009; Murata et al. 2010), even though ATP is required for transmission of all tastes. ATP release is believed to be mediated by a nonvesicular mechanism, because Type II cells lack the presynaptic mechanisms normally required for vesicular release of transmitter (Clapp et al. 2004; Vandenbeuch et al. 2010) and because pharmacological inhibitors of ATP release channels decrease taste-evoked release of ATP (Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007; Murata et al. 2010). However, Type II cells also express the vesicular ATP transporter VNUT (Iwatsuki et al. 2009), suggesting that ATP could also be transported into and released from vesicles. Nonvesicular release of ATP is likely mediated by large-pore gated channels in the plasma membrane. Several potential ATP release channels are expressed in taste tissue including CALHM1 (Taruno et al. 2013), Connexins 30 and 43 (Romanov et al. 2007, 2008) and pannexin 1 (Panx1; Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007). Of these, only CALHM1 has been tested at the systems level and knockout animals show a significant decrease of taste responses to sweet, bitter, and umami (Taruno et al. 2013; Hellekant et al. 2015) as well as salty stimuli (Tordoff et al. 2014). CALHM1 is clearly playing a role in ATP release but because taste responses were not completely abolished in the knockout, other channels may be involved. The pannexin channels are large conductance ion channels (~500 pS) and release compounds smaller than 1 kD including ATP. Evidence for a role of Panx1 in ATP release is: (i) the channel is expressed in virtually all Type II taste cells (Huang et al. 2007), and (ii) low concentrations of carbenoxolone, a relatively specific inhibitor of pannexins over connexins, blocks taste-evoked release of ATP (Huang et al. 2007, 2011; Dando and Roper 2009; Murata et al. 2010). However, the deletion of Panx1 in taste buds does not prevent ATP release from taste buds (Romanov et al. 2012). To reconcile these data, we tested global Panx1 KO mice with behavior, gustatory nerve recordings and a luciferin/luciferase ATP release assay to determine if Panx1 plays a role in ATP release in taste buds.

Materials and methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted on global Pannexin 1 knockout (Panx1tm1b(KOMP)Wtsi) mice bred on a C57BL/6J background and obtained from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP). To obtain these mice, KOMP bred mice containing the reporter-tagged knock-out first allele (tm1a) to mice expressing a ubiquitous CMV-driven Cre driver, to delete the floxed exon 2 from Panx1. Control experiments were conducted on C57Bl/6J mice obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Male and female mice aged between 3 and 6 months were used in the experiments. All animals were housed at the University of Colorado in ventilated cages and had free access to water and food. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado Medical School.

RNA extraction

Taste buds were isolated from the fungiform and circumvallate taste papillae and surrounding nontaste epithelial tissue after treatment with an enzyme cocktail consisting of Dispase II (3mg/mL; Roche) and Elastase (2.5mg/mL; Worthington) in Tyrode’s for 20min. After peeling, the epithelium was placed for 15min in calcium-free Tyrode’s. Individual taste buds were then sucked with a fire-polished glass pipette and pooled from three adult Panx1 KO and three adult Panx1 WT mice. RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions using the RNeasy Micro kit from Qiagen, including a 30min DNaseI treatment at room temperature for removal of genomic DNA. Reverse transcription was performed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit from Biorad.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed to validate absence of Panx1 in the taste buds of the Panx1 KO mice. Reactions were set up in which reverse transcriptase enzyme was omitted as a control to test for DNA contamination. Two microliters of cDNA were added to the PCR reaction (Qiagen Taq PCR Core kit). PCR conditions included an initial 5min denaturation step followed by 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 95°C, 30 s annealing at 60°C, and 45 s extension at 72°C; concluding with a 7min final extension step. We included cDNA from mouse whole brain (Clontech) as a positive control and used water as a no template control. Amplified sequences were visualized by gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels stained with GelRed (Biotium).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to compare the expression levels of CALHM1, Cx30 and Cx43 in Panx1 WT mice and Panx1 KO mice. Pooled RNA extraction was performed as previously mentioned and repeated 3 independent times. All qPCR assays were run in triplicate. Two microliters of cDNA were used in each PCR reaction using the ABI SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Primers (10 µM) were designed for the reference gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), CALHM1, Cx43, and Cx30 (Table 1) and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. A 2-step PCR was used (initial 10min denaturation at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 s denaturation at 95°C and 60 s annealing and extension at 60°C) in the Biorad CFX Real-Time PCR Detection System. We utilized the SYBR green dye qPCR technique to detect double-stranded DNA/PCR products as they accumulated during PCR cycles. Melting curves were run for each experiment to assure specificity of products. For quantitative analysis, we adapted the Comparative C t relative expression method (Schmittgen and Livak 2008). C t for each sample was set to occur during the exponential growth phase of the curve. The cycle threshold (C t) values for our reference gene, GAPDH, were subtracted from the C t of our target genes (CALHM1, Cx43, and Cx30) and to obtain the mean ΔC t value (C t target gene − C t GAPDH) for specific taste tissues for each group of mice. The mean ± SD was then calculated for each tissue. Fold differences were calculated for each specific taste tissue and gene using the ratio mean KO to mean WT . A Student’s t-test was also used to compare between WT and KO mice.

Table 1.

List of PCR primers used to detect ATP release channels

| Protein | Accession No. | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panx1 | NM_019482 | gctccctgcagagcgagtctgg | ctcttggcagccttgatggcgc | 201 |

| CALHM1 | NM_00108171 | gtaccctgccctgagatctat | cgtaccacgaacgctagtaatg | 134 |

| Cx43 | NM_010288 | tcatcttcatgctggtggtgtcct | tggtgaggagcagccattgaagta | 194 |

| Cx30 | NM_001010937 | tgagcaggaggactttgtctgcaa | tgtgagacaccgggaagaaatggt | 83 |

| GAPDH | NM_008084 | tcaacagcaactcccactcttcca | accctgttgctgtagccgtattca | 115 |

ATP release

Patches of lingual epithelium containing the circumvallate papilla were peeled from the tongue after enzymatic treatment with a mixture of Dispase II (3mg/mL; Roche) and Elastase (2.5mg/mL; Worthington) for 18min. The piece of tissue was then placed in a modified Ussing chamber (42 µL) with the basolateral part of the papilla bathed in Tyrode’s. The apical part of the papilla was successively stimulated for 3min with artificial saliva and a bitter mix (denatonium 10mM + cycloheximide 100 µm) diluted in artificial saliva (5 µL). Because the preparation is highly sensitive to mechanical stimulation, the artificial saliva was not rinsed and the bitter mix was added to the already present artificial saliva. Hence, the final concentrations of denatonium and cycloheximide at the taste buds apical membrane were diluted to approximately 5mM and 50 µM, respectively. The bathing solution was then transferred to a 96-well plate and placed in a plate reader (Synergy HT; Biotek). The same amount of luciferase (ATP bioluminescence kit HS II; Roche) was added to the bath via an internal injector and the luminescence reading was performed. Results were obtained as relative light units and converted to ATP concentrations with a standard ATP curve obtained from known concentrations of ATP run on the same day. The experiment was repeated on 6 WT and 6 KO mice. A paired Student’s t-test was used to compare ATP release with artificial saliva and the bitter mix whereas an unpaired t-test was used to compare ATP release from WT and KO mice. The Tyrode’s solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 4 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 1 Na-Pyruvate, 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. Artificial saliva contained (in mM): 2 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 NaHCO3, 3 KHCO3, 1.8 HCl, 0.25 CaCl2, 0.25 MgCl2, 0.12 K2HPO4, 0.12 KH2PO4. Results were analyzed using a 2-way repeated measures ANOVA (genotype × stimulus) with Tukey’s post hoc test (Statistica software, version 10).

Nerve recording

Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50mg/kg) and maintained in a head holder. The trachea was cannulated to facilitate breathing. The chorda tympani nerve was exposed using a ventral approach, freed from surrounding tissue and cut near the tympanic bulla. To expose the glossopharyngeal nerve, the digastric muscle was removed and the nerve was cut near its entrance to the posterior foramen. Nerves were then placed on a platinum-iridium wire and a reference electrode was placed in a nearby tissue. The signal was fed to an amplifier (P511; Grass Instruments), integrated and recorded using AcqKnowledge software (Biopac). For chorda tympani recordings, a total 9 WT and 9 KO mice were used for each stimulus. For glossopharyngeal recordings, a total of 10 WT and 7 KO mice were used. The fungiform papillae (chorda tympani) or the circumvallate papilla (glossopharyngeal nerve) was stimulated with different tastants applied with a constant flow pump (Fisher Scientific). Stimuli including NH4Cl 100mM, sucrose 500mM, MPG 100mM + IMP 0.5mM, HCl 10mM, citric acid 10mM, quinine 10mM, NaCl 100mM were applied for 30 s and rinsed with water for 40 s. To reduce the variability across animals, each response was normalized to the response to 100mM NH4Cl. To analyze the data, the amplitude of each integrated response was averaged over the 30 s using AcqKnowledge software and compared between WT and Panx1 KO with a 2-way ANOVA when several concentrations of the same stimulus were applied or compared with an unpaired Student’s t-test for single concentrations (GraphPad Prism 5).

Lickometer

Panx1 WT (n = 8) and KO (n = 7) mice were trained and tested in a Davis Rig Lickometer (DiLog Instruments). Before training, mice were placed on a 20-h water deprivation schedule with free access to food. At the beginning of testing, mice were water-deprived for 16–20h. On day 1 of training, mice were placed in the apparatus and had access to a water bottle for 15min. On days 2 and 3 of training, mice were presented sequentially with 6 bottles of water. The shutter closed 5 s after the first lick and moved to the next bottle after a 7.5 s interval. On the first and second day of testing, mice were given different concentrations of the artificial sweetener SC45647 diluted in water (0, 3, 10, 30, 100, or 300 µM). Each concentration was presented several times during the 15-min test. To represent the data, we calculated the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) number of licks for all presentations and each concentration. A 2-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data (GraphPad Prism 5).

Results

Absence of Panx1 expression in Panx1 KO mice

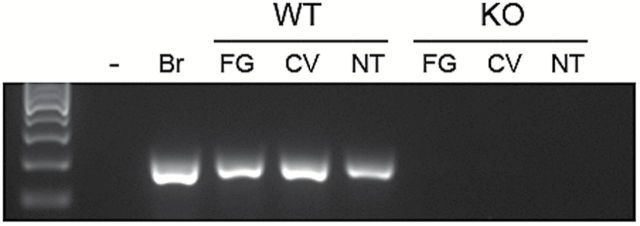

We used RT-PCR to confirm that the global Panx1 KO mice do not express Panx1 in taste tissues. As shown in Figure 1, the pooled taste buds isolated from fungiform and circumvallate papillae as well as the nontaste tissue do not contain Panx1.

Figure 1.

RT-PCR products for Panx1 in WT and KO mice. The expected size for Panx1 (201bp) was observed in fungiform (FG), circumvallate (CV), and nontaste (NT) tissue of WT animals but was absent in all tissues from KO. Brain (Br) and zero template (−) were used as controls.

To verify that the deletion of Panx1 in knockout animals did not lead to the overexpression of other potential ATP release channels known to be expressed in taste tissues, we performed quantitative PCR on isolated pooled taste buds. Results show no significant difference between Panx1 KO and WT in the expression of CALHM1, Connexin 30, or Connexin 43 in all fungiform and circumvallate taste buds (Table 2). These results suggest that genetic deletion of Panx1 does not evoke upregulation of other ATP release channels in taste buds.

Table 2.

Quantitative PCR results

| Protein | Tissue | Mean ± SD | Fold change | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | KO | ||||

| CALHM1 | FG | 3.9×10−5 ± 2.8×10−5 | 8.6×10−5 ± 8.4×10−5 | 2.21 | NS |

| CV | 7.0×10−3 ± 5.6×10−3 | 4.9×10−3 ± 1.9×10−3 | 0.71 | NS | |

| Cx43 | FG | 1.9×10−1 ± 1.0×10−1 | 3.3×10−1 ± 1.4×10−1 | 1.75 | NS |

| CV | 1.2×10−1 ± 3.9×10−2 | 1.3×10−1 ± 9.9×10−2 | 1.05 | NS | |

| NT | 2.7×10−1 ± 1.8×10−1 | 2.8×10−1 ± 3.0×10−1 | 1.04 | NS | |

| Cx30 | FG | 1.0×10−2 ± 1.7×10−3 | 1.3×10−2 ± 4.0×10−3 | 1.28 | NS |

| CV | 3.7×10−2 ± 1.7×10−2 | 3.0×10−2 ± 2.1×10−2 | 0.80 | NS | |

| NT | 5.2×10−2 ± 1.0×10−2 | 3.0×10−2 ± 2.1×10−2 | 1.01 | NS | |

NS, not significant. GAPDH was used as the reference gene to calculate ΔC t. No significance difference (unpaired Student’s t-test; P > 0.05; n = 3) was observed in the expression of CALHM1, Connexin 43, and Connexin 30 in KO compared with WT mice.

Nerve recordings

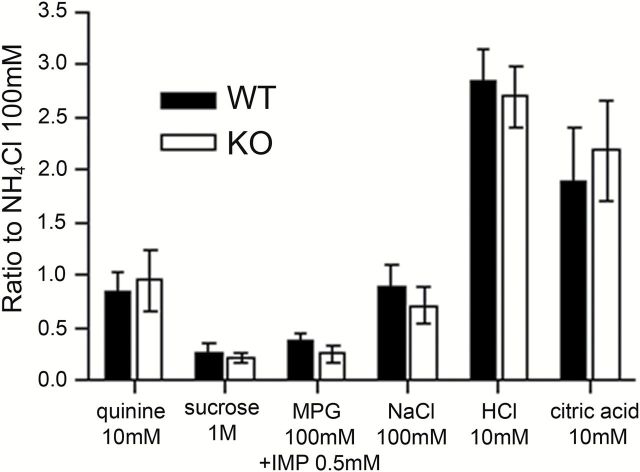

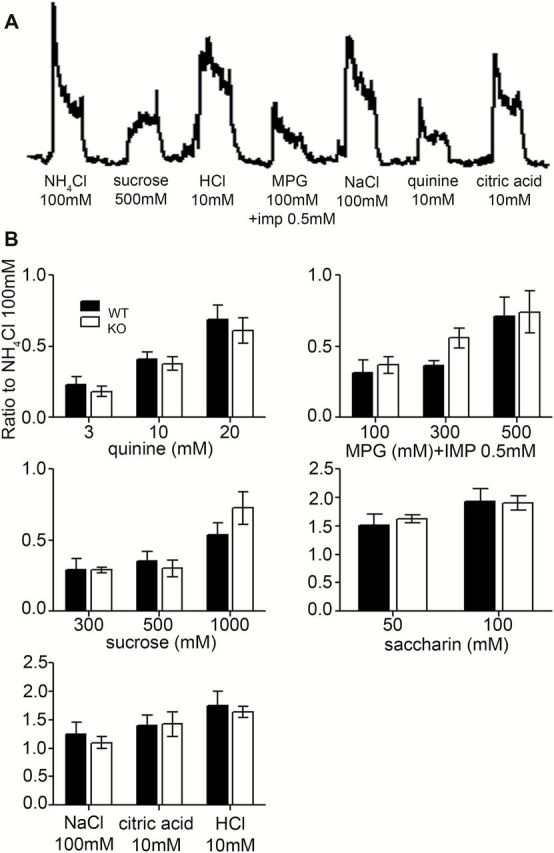

To test whether Panx1 contributes to the release of ATP and taste responses, we used WT and Panx1 KO mice and performed chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal whole-nerve recordings while stimulating the tongue with various taste stimuli. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 3, Panx1 KO mice showed similar responses to all taste qualities in chorda tympani compared with WT mice (2-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). Similarly, in the glossopharyngeal nerve (Figure 3), no significant difference in the response to various tastants was observed between WT and KO mice [F(1, 83) = 3.12, P = 0.085, 2-way ANOVA]. These data suggest that Panx1 is not required for the transmission of the signal from taste cells to nerve fibers and that there is no significant difference between KO and control mice.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative integrated chorda tympani nerve responses in Panx1 KO mice. Taste stimuli were applied for 30 s with 40 s intervening washes. (B) Amplitude of the integrated response for each tastant. Responses were normalized to the response to 100mM NH4Cl to control for variability between mice. Responses show the mean ± SEM (n = 5–9 mice for each stimulus). No significant difference was observed between the WT (black bars) and KO (open bars) mice for any of the tastants (2-way ANOVA, P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Results of ANOVAs for chorda tympani nerve recordings

| Stimulus | Genotype | Concentration | Genotype × concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinine | F(1, 33) = 0.70; P = 0.4085 | F(2, 33) = 16.19; P < 0.0001 | F(2, 33) = 0.05; P = 0.9496 |

| MPG + IMP 0.5 mM | F(1, 28) = 1.37; P = 0.2522 | F(2, 28) = 7.58; P = 0.0023 | F(2, 28) = 0.43; P = 0.6564 |

| Sucrose | F(1, 31) = 0.36; P = 0.5505 | F(2, 31) = 9.65; P = 0.0006 | F(2, 31) = 1.22; P = 0.3077 |

| Saccharin | F(1, 14) = 0.05; P = 0.8265 | F(2, 14) = 3.19; P = 0.0955 | F(2, 14) = 0.14; P = 0.7162 |

Figure 3.

Amplitude of integrated glossopharyngeal nerve responses in Panx1 WT and KO mice. Responses represented as in Figure 2 (n = 5–10 mice for each stimulus). No significant difference was observed between the WT (black bars) and KO (open bars) mice for any of tastants (2-way ANOVA, P > 0.05).

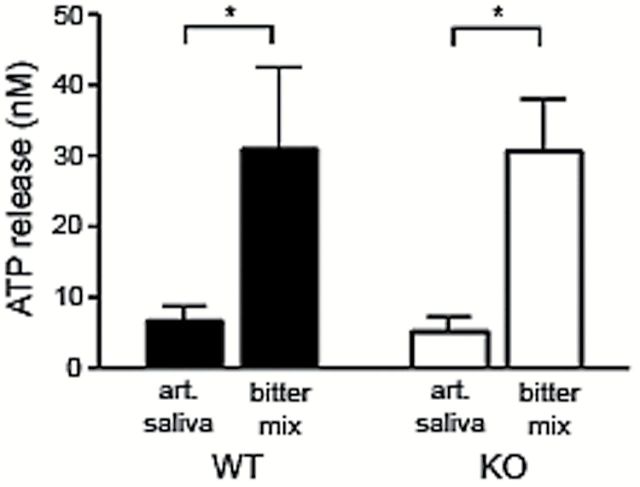

ATP release

Because low concentrations of carbenoxolone (an inhibitor of Panx1) blocked the release of ATP from Type II cells in other studies (Huang et al. 2007, 2011; Dando and Roper 2009; Murata et al. 2010), we used a luciferin/luciferase assay to compare ATP release from Panx1 KO and WT mice in response to artificial saliva (to control for mechanically evoked release) and a bitter mix of denatonium and cycloheximide in artificial saliva (final concentrations approximately 5 μM and 50 μM, respectively). There was no significant difference in the amount of ATP released in Panx1 KO compared with WT mice [F(1, 10) = 0.01, P = 0.9, 2-way ANOVA; Figure 4]. Both Panx1 KO and WT mice released a significantly higher amount of ATP after stimulation with the bitter stimuli compared with stimulation with artificial saliva [F(1, 10) = 14.97, P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test] These results, utilizing a different assay, confirm an earlier study (Romanov et al. 2012) that Panx1 is not required for ATP release in taste buds.

Figure 4.

ATP concentration from circumvallate papillae from Panx1 WT and KO mice. The apical part of the papilla was stimulated successively with artificial saliva (art. saliva) and a bitter mix (Denatonium 10mM + Cycloheximide 100 µM in artificial saliva). In both groups, the stimulation with the bitter mix induced a significantly higher level of ATP release compared to stimulation with artificial saliva. Asterisks indicate P < 0.05, Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 6 for WT and n = 6 for KO). The amount of ATP released upon stimulation with the bitter mix was not significantly different in Panx1 KO compared with WT.

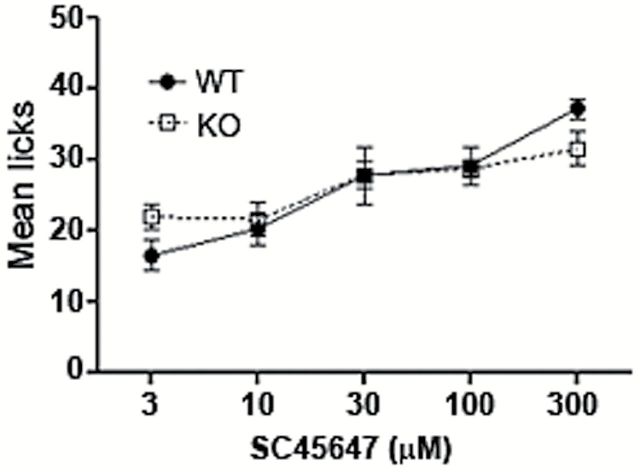

Behavior

To determine whether the deletion of Panx1 affects the licking behavior in awake animals, mice were tested in a lickometer with the artificial sweetener SC45647. This sweetener has a purely sweet taste and does not elicit a postingestive effect (Sclafani and Glendinning 2003, 2005). Figure 5 shows the mean number of licks for each concentration of SC45647 for both Panx1 WT and KO mice. No significant difference was observed between the 2 groups of mice suggesting that Panx1 is not necessary for behavioral detection of sweet stimuli [F(1, 65) = 0.01; P = 0.93].

Figure 5.

Behavioral taste response to SC45647 in Panx1 WT and KO mice. Mean ± SEM number of licks in all presentations of each concentration. No significance difference was observed between the WT (black circles; n = 8) and KO (open squares; n = 7) (2-way ANOVA, P > 0.05).

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that Panx1 is not required for the taste evoked release of ATP from taste cells or for transmission of the signal from taste cells to taste nerves. Nerve recordings from both the chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerve show normal responses to all taste qualities in KO compared with control WT mice. In a brief access taste test, WT and KO mice are similar in their responses to different concentrations of SC45647. Moreover, the circumvallate papilla shows the same amount of ATP released upon stimulation with a bitter mix as the controls. However, it is possible that the techniques used in our study were not sensitive enough to detect a small effect due to absence of Pannexin 1. Our results, obtained using different knockout mice, confirm and extend other studies showing that taste buds isolated from Pannexin 1 KO mice still release ATP after taste stimulation or depolarization with KCl (Romanov et al. 2012) and Pannexin KO mice show normal behavioral responses to all taste qualities (Tordoff et al. 2015).

The primary evidence for a role of Panx1 in ATP release is that low concentrations of carbenoxolone inhibit taste-evoked release of ATP in isolated taste buds (Huang et al. 2007; Murata et al. 2010). Carbenoxolone is moderately specific for pannexin over connexin channels, with an IC50 of 5 μM for block of Panx1 (Bruzzone et al. 2005) with at least 10-fold higher concentrations needed to block connexins. Other studies, however, found no effect of carbenoxolone, even at 100 μM, on depolarization-evoked ATP release from taste cells (Romanov et al. 2007, 2008), but inhibitors of connexin channels, such as the mimetic peptide Gap26 and octanol did so. Whether this discrepancy is due to the different methods of stimulation (taste vs. depolarization) or other factors remains to be determined. An additional concern is that carbenoxolone has other nonspecific effects, including a decreased action potential firing rate in neurons (Tovar et al. 2009). Since taste cells fire action potentials, and action potentials are required for ATP release (Murata et al. 2010), it is possible that carbenoxolone alters taste-evoked ATP release by nonspecifically decreasing action potential firing in response to taste stimulation.

Another inhibitor, probenecid, has no effect on connexin channels but specifically blocks pannexin channels (Silverman et al. 2008). Probenecid was used, in vitro, on isolated taste cells and blocked the taste-evoked ATP release from Type II cells (Dando and Roper 2009). These results were, however, not confirmed by another study (Taruno et al. 2013) showing that probenecid had no effect on ATP release from taste cells. The inconsistency in the results from different studies, as well as our in vivo studies makes the role of Panx1 in ATP release questionable.

If Panx1 is not involved in ATP release, what is its possible role in the taste bud? Only Type II cells have been shown to release ATP upon membrane depolarization (Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007) or stimulation with tastants (Huang et al. 2007; Murata et al. 2010) but interestingly, all cell types express at least some Panx1 (Huang et al. 2007). Thus, Panx1 in taste cells may be connected to functions other than ATP release. Panx1 can bind to purinergic receptors containing P2X2 and P2X7 and is responsible for their large pore mode of conductance (Pelegrin and Surprenant 2006, 2009). In oocytes, the formation of the large pore is involved in cell death (Locovei et al. 2007). Taste cells express both P2X2 (Hayato et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2011) and P2X7 (Hayato et al. 2007), so such a mechanism could possibly contribute to cell death in taste buds.

What is the likely mechanism of the residual taste responses in the CALHM1 knockout mice? Our data clearly suggest that Panx1 is not involved, although to be completely sure Panx1/CALHM1 double knockouts would need to be generated and tested. Residual effects could be due to vesicular release of ATP, since the enzyme for transporting ATP into vesicles is expressed in Type II taste cells (Iwatsuki et al. 2009). However, other conditions normally required for vesicular release, such as voltage-gated calcium channels, are absent in Type II cells (Clapp et al. 2006; DeFazio et al. 2006; Vandenbeuch et al. 2010). A more plausible mechanism is another ATP release channel, such as one of the connexin hemichannels. Both Connexins 30 and 43 have been identified in taste tissue and surrounding lingual epithelium, (Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007) and our RT-PCR results confirm this expression pattern. Interestingly, Romanov et al. (2007, 2008) demonstrated that, in heterologous cells, the kinetics of ATP release is more consistent with connexin channels than pannexin channels. Indeed, ATP is released via slowly deactivating channels, a feature not displayed by pannexin channels (Valiunas 2002). So, whether the small remaining response to tastants in the CALHM1 knockout mice may be due to the expression of connexins 43 or 30, or possibly another ATP release channel still must be determined. Further studies will be needed to fully understand ATP release in taste buds.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01 DC012555 to S.C.K. and P30 DC004657 to Diego Restrepo].

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyndal Davis and Matthew Steritz for genotyping and maintaining the mouse colony, and Drs Thomas Finger and Eric Larson for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr Jennifer Stratford for her help with statistics.

References

- Bartel DL, Sullivan SL, Lavoie EG, Sevigny J, Finger TE. 2006. Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-2 is the ecto-ATPase of type I cells in taste buds. J Comp Neurol. 497:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikov SG, Rogachevskaja OA, Kolesnikov SS. 2003. Calcium signaling mediated by P2Y receptors in mouse taste cells. J Neurophysiol. 90:3283–3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo X, Alavi A, Xiang Z, Oglesby I, Ford A, Burnstock G. 1999. Localization of ATP-gated P2X2 and P2X3 receptor immunoreactive nerves in rat taste buds. Neuroreport. 10:1107–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Barbe MT, Jakob NJ, Monyer H. 2005. Pharmacological properties of homomeric and heteromeric pannexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurochem. 92:1033–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystrova MF, Yatzenko YE, Fedorov IV, Rogachevskaja OA, Kolesnikov SS. 2006. P2Y isoforms operative in mouse taste cells. Cell Tissue Res. 323(3):377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Medler KF, Damak S, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC. 2006. Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25. BMC Biol. 4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Yang R, Stoick CL, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC. 2004. Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Comp Neurol. 468:311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dando R, Roper SD. 2009. Cell-to-cell communication in intact taste buds through ATP signalling from pannexin 1 gap junction hemichannels. J Physiol. 587:5899–5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio RA, Dvoryanchikov G, Maruyama Y, Kim JW, Pereira E, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. 2006. Separate populations of receptor cells and presynaptic cells in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci. 26:3971–3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger TE, Danilova V, Barrows J, Bartel DL, Vigers AJ, Stone L, Hellekant G, Kinnamon SC. 2005. ATP signaling is crucial for communication from taste buds to gustatory nerves. Science. 310(5753):1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayato R, Ohtubo Y, Yoshii K. 2007. Functional expression of ionotropic purinergic receptors on mouse taste bud cells. J Physiol. 584:473–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellekant G, Schmolling J, Marambaud P, Rose-Hellekant TA. 2015. CALHM1 deletion in mice affects glossopharyngeal taste responses, food intake, body weight, and life span. Chem Senses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang AL, Chen X, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Guo W, Tränkner D, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. 2006. The cells and logic for mammalian sour taste detection. Nature. 442(7105):934–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YA, Dando R, Roper SD. 2009. Autocrine and paracrine roles for ATP and serotonin in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci. 29:13909–13918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2007. The role of pannexin 1 hemichannels in ATP release and cell–cell communication in mouse taste buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:6436–6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YA, Stone LM, Pereira E, Yang R, Kinnamon JC, Dvoryanchikov G, Chaudhari N, Finger TE, Kinnamon SC, Roper SD. 2011. Knocking out P2X receptors reduces transmitter secretion in taste buds. J Neurosci. 31:13654–13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki K, Ichikawa R, Hiasa M, Moriyama Y, Torii K, Uneyama H. 2009. Identification of the vesicular nucleotide transporter (VNUT) in taste cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 388(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Toyono T, Seta Y, Ogura T, Toyoshima K. 2004. Expression of P2Y1 receptors in rat taste buds. Histochem Cell Biol. 121(5):419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Scemes E, Qiu F, Spray DC, Dahl G. 2007. Pannexin1 is part of the pore forming unit of the P2X(7) receptor death complex. FEBS Lett. 581(3):483–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Yasuo T, Yoshida R, Obata K, Yanagawa Y, Margolskee RF, Ninomiya Y. 2010. Action potential-enhanced ATP release from taste cells through hemichannels. J Neurophysiol. 104:896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka Y, Butnaru M, von Buchholtz L, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. 2013. High salt recruits aversive taste pathways. Nature. 494(7438):472–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. 2006. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 25:5071–5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. 2009. The P2X(7) receptor-pannexin connection to dye uptake and IL-1beta release. Purinergic Signal. 5(2):129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Bystrova MF, Rogachevskaya OA, Sadovnikov VB, Shestopalov VI, Kolesnikov SS. 2012. The ATP permeability of pannexin 1 channels in a heterologous system and in mammalian taste cells is dispensable. J Cell Sci. 125:5514–5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Bystrova MF, Jiang P, Margolskee RF, Kolesnikov SS. 2007. Afferent neurotransmission mediated by hemichannels in mammalian taste cells. EMBO J. 26:657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Khokhlov AA, Kolesnikov SS. 2008. Voltage dependence of ATP secretion in mammalian taste cells. J Gen Physiol. 132(6):731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 3:1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A, Glendinning JI. 2003. Flavor preferences conditioned in C57BL/6 mice by intragastric carbohydrate self-infusion. Physiol Behav. 79:783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A, Glendinning JI. 2005. Sugar and fat conditioned flavor preferences in C57BL/6J and 129 mice: oral and postoral interactions. Am J Physiol. Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 289:R712–R720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Locovei S, Dahl G. 2008. Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 295:C761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taruno A, Vingtdeux V, Ohmoto M, Ma Z, Dvoryanchikov G, Li A, Adrien L, Zhao H, Leung S, Abernethy M, et al. 2013. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature. 495:223–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordoff MG, Aleman TR, Ellis HT, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Shestopalov VI, Mitchell CH, Foskett JK, Poole RL. 2015. Normal taste acceptance and preference of PANX1 knockout mice. Chem Senses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordoff MG, Ellis HT, Aleman TR, Downing A, Marambaud P, Foskett JK, Dana RM, McCaughey SA. 2014. Salty taste deficits in CALHM1 knockout mice. Chem Senses. 39(6):515–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar KR, Maher BJ, Westbrook GL. 2009. Direct actions of carbenoxolone on synaptic transmission and neuronal membrane properties. J Neurophysiol. 102:974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiunas V. 2002. Biophysical properties of connexin-45 gap junction hemichannels studied in vertebrate cells. J Gen Physiol. 119(2):147–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Anderson CB, Parnes J, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, Finger TE, Kinnamon SC. 2013. Role of the ectonucleotidase NTPDase2 in taste bud function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110:14789–14794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Larson ED, Anderson CB, Smith SA, Ford AP, Finger TE, Kinnamon SC. 2015. Postsynaptic P2X3-containing receptors in gustatory nerve fibres mediate responses to all taste qualities in mice. J Physiol. 593:1113–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbeuch A, Zorec R, Kinnamon SC. 2010. Capacitance measurements of regulated exocytosis in mouse taste cells. J Neurosci. 30:14695–14701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]