1. INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a global health concern, affecting 300 million people worldwide. In the US asthma affects 9.5% of children and 8.2% of adults (CDC, 2012). Current standard therapies for asthma which include inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and β2 agonists, are sub-optimally effective in approximately 50% of patients, especially in children (Ducharme et al., 2010;Kelly and Fitzpatrick, 2011;Peters et al., 2007). Asthma is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory disease, which is associated with inflammation mediated by Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, and inflammation mediated by other cytokines such as TNF- α. Unlike Th2 mediated eosinophil predominant inflammation, TNF-α mediated neutrophil and mixed eosinophil and neutrophil inflammation are generally insensitive to ICS. Effective therapies for these conditions are needed.

TNF-α is produced by many cell types, mainly macrophages and monocytes and lymphocytes, in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other stimuli (Berry et al., 2007;Kim et al., 2012). LPS induces TNF-α production through activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), activator protein 1 (AP-1) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAP kinases or MAPK)(Guha and Mackman, 2001). Increased levels of phosphorylated- IκB-α (p-IκBα) protein and p65 in cytosol and nuclear p-p65 indicate heightened NF-κB activation (Ulevitch and Tobias, 1995). AP-1is a heterodimeric protein constituted by members of the Jun and Fos families of DNA binding proteins. Many stimuli (like LPS) induce the binding of AP-1to the promoter region of various genes that enhance the expression of inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-α (Chen et al., 2014). MAP kinases include extracellular-signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK 1/2), p-38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). MAP kinase pathways activate NF-κB and AP-1, which coordinate the induction of TNF-α gene expression (Chen et al., 2014).

Traditional Chinese medicines are increasingly used in the US by individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions including asthma. However, data on efficacy, safety, and mechanisms of action of natural products is limited. A major obstacle is the paucity of knowledge of characterized pharmacologically active compounds in complex herbal products. We previously investigated the anti-asthma herbal medicine intervention ASHMITM -extracts of Ganoderma lucidum (G. lucidum), Sophora flavescens Ait (S. flavescens) and Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fischer (G. uralensis) (Kelly-Pieper et al., 2009;Srivastava et al., 2014;Wen et al., 2005;Zhang et al., 2010). ASHMITM was reported to have beneficial effects and favorable safety in clinical studies (Kelly-Pieper et al., 2009;Wen et al., 2005). In addition to its long-lasting effectiveness in a model of eosinophil predominant asthma (Zhang et al., 2010), ASHMITM is also effective in a steroid resistant neutrophil predominant allergy asthma model (Srivastava et al., 2014). Therapeutic effects are associated with both reduced pro allergic Th-2 inflammation cytokine production, including IL-4, and non Th-2 inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. We previously demonstrated that 7, 4′-dihydroxyflavone is the most effective G. uralensis flavonoid inhibitor of pro-allergic chemokine production (Jayaprakasam et al., 2009) and the pro Th2 cytokine transcription factor GATA3 (Yang et al., 2013). However, the ASHMITM compound (s) responsible for inhibiting production of TNF-α, recently highlighted as important in steroid resistant asthma, was unknown.

The present study found that G. lucidum extracts, but not those of S. flavescens or G. uralensis significantly suppressed murine macrophage TNF-α production; and that methylene chloride (MC) fraction of G. lucidum was the active fraction. Among the 15 bioactive triterpenoid compounds isolated from this fraction, only ganoderic acid C1 (GAC1) significantly suppressed TNF-α production by murine macrophages (RAW 264.7 cells). GAC1 also non-toxically inhibited TNF-α production by PBMCs from asthma patients. GAC1 inhibition of LPS stimulated macrophage TNF-α production was associated with suppression of NF-κB, and partial suppression of the AP-1, and MAPK signaling pathways. Suppression of NF-κB signaling was also found in asthma patient PBMCs. GAC1 may prove to be a novel TNF-α inhibitor with application to TNF-α associated asthma and other disease therapy.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant Materials

ASHMITM, G. lucidum, S. flavescens, and G. uralensis aqueous extracts were manufactured by the Sino-Lion Pharmaceutical Company (a GMP certified facility in Weifang, China) as described previously(Kelly-Pieper et al., 2009;Zhang et al., 2010).

2.2. Extraction and isolation of compounds from G. lucidum

A dried aqueous extract of G. lucidum was dissolved in water and extracted with methylene chloride (MC). The MC layer and water residue layers after methylene chloride extraction were concentrated and dried under pressure to obtain two fractions: F1 (MC), and F2. The F1fraction was further fractionated and purified using repeated silica gel, preparative HPLC, and Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography methods to obtain 15 pure compounds (1–15) (eTable 1).

2.3. Identification of compounds isolated from G. lucidum

1H (300 MHz) and 13C (75 MHz) NMR were collected on a JEOL ECX-300 instrument. Samples were dissolved in DMSO-d6, methanol-d4, or chloroform-d containing TMS as an internal standard, and MS spectra were recorded on an Agilent 6130 single quadrupole LC MS. Analysis of 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra yielded characteristic signals for each compound as shown below. Ganoderiol F (1) (C30H46O3) (DMSO-d6): δ 6.46 (1H, d, J = 8.58Hz, H-24), 5.64 (1H, s, H-7), 5.54 (1H, s, H-11), 4.80 (2H, m, H-26), 4.49 (2H, m, H-27). The 1H-NMR spectrum of ganoderic acid α (2) (C32H46O9) (chloroform-d) showed 8 methyl signals, including a signal at δ 2.22 (3H, s, COCH3-12). Ganoderic acid V (3) (C32H48O6) (chloroform-d): δ 6.17 (1H, s, H-24), 4.85 (1H, m, H-7), 4.48 (1H, m, H-15), 2.33 (3H, s, COCH3-15). Ganoderic acid H (4) (C32H44O9) (methanol-d4): δ 3.23 (1H, m, H-3), 2.21 (3H, s, COCH3-12). Ganoderic acid C2 (5) (C32H46O7) (methanol-d4): δ 4.78 (1H, m, H-7), 4.57 (1H, m, H-15), 3.21 (1H, m, H-3). Ganolucidic acid A (6) (C30H44O6) (methanol-d4): δ 4.58 (1H, s, H-15). Ganolucidic acid E (7) (C31H46O4) (chloroform-d): δ 4.78 (1H, m, H-15), 2.47 (3H, m, CH3-26). The 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6) spectrum of Ganoderic acid C1 (8) (C30H42O7) showed a proton signal at δ 4.80 (1H, m, H-7). 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6) spectra showed signals at δ 216.0 (C-15), 215.1 (C-3), 208.6 (C-23), 198.0 (C-11), 176.7 (C-26), 159.4 (C-9), 139.8 (C-8), and 64.8 (C-7). Ganoderenic acid A (9) (C30H42O7) (methanol-d4): δ 6.25 (1H, s, H-22), 4.65 (1H, s, H-7), 4.53 (1H, m, H-15). Ganolucidic acid D (10) (C30H44O6) (DMSO-d6): δ 5.32 (1H, s, H-24), 4.56 (1H, m, H-23). Ganoderic acid U (11) (C30H48O4) (methanol-d4): δ 4.87 (1H, s, H-7), 3.28 (1H, s, H-3). Ganoderic acid J (12) (C30H42O7) (DMSO-d6): δ 4.57 (1H, s, H-15). Ganoderic acid A (13) (C30H44O7) (DMSO-d6): δ 4.76 (1H, s, 7-H), and 4.60 (1H, s, 15-H). Ganoderic acid K (14) (C30H44O7) (DMSO-d6): δ 3.19 (1H, s, 3 H) and 4.53(1H, s, 15-H). Ganoderenic acid D (15) (C30H40O7) (methanol-d4): δ 4.48 (1H, s, H-7).

2.4. RAW 264.7 cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells, a murine macrophage cell line, purchased from American Type Collection Culture (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. To determine potential inhibitory effects of herbs and compounds on LPS-stimulated TNF-α production, linearly growing cells were detached using a cell scraper, and 5×105 cells per well were seeded in 24-well culture plates. Cells were pretreated with herbal extracts or individual compounds for 24 hours followed by stimulation with 1.0 μg/mL LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for another 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested for measurement of TNF-α. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO. The concentration of DMSO in all cultures, including medium alone and LPS alone cultures, was 0.1%. Cell viability was determined using trypan blue dye exclusion and calculating the ratio of viable cells to total cells.

2.5. Annexin V apoptosis assay and MTT cell proliferation assay

Annexin V assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences Annexin V–FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit). Cells were washed twice with PBS and then exposed to annexin V–FITC and propidium iodide (PI) in binding buffer for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Analyses were performed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) emitting an excitation laser light at 488 nm. Fluorescence signals were detected at 518 and 620 nm for FITC and PI detection, respectively. Data were analyzed using CELLQuest (Becton Dickinson) software. For each analysis, 10,000 events were recorded.

MTT Cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay as previously described (Liu et al., 2015)(Deng et al., 2013). Briefly, 100μL of Raw264.7 cells at a concentration of 2×105/mL were added to a 96-well tissue culture plate and allowed to adhere. After 30 minutes, the cells were treated with GAC1 at various concentrations. After 24 hours, 50μL of (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) 2.0 mg/mL in culture medium was added and incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2/95% air, water-jacketed incubator. The supernatant was then discarded and replaced with 200μL of DMSO and the plate was placed on an orbital shaker at room temperature. After 30 minutes absorbance was read at 570 nm using a Vmax Kinetic ELISA microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.6. TNF-α levels measurement

TNF-α levels were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). All experiments were replicated at least three times with duplicate ELISA measurement of each sample.

2.7. Human Subjects

Human studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Blood samples were taken from 14 physician-diagnosed asthma patients (age: 25.3±8.7 yrs; Male/Female: 6/8), who had not taking oral steroids for at least one month. All patients signed informed consent.

2.8. PBMC isolation and cell culture

Eleven asthma patients PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll Hypaque (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Piscataway, NJ) density-gradient centrifugation at 1800 RPM for 30 minutes, and washed 3 times in physiological buffer solution (PBS). To assess the effect of GAC1 on TNF-α production, purified PBMCs (2×106/well) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 mM Hepes 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 60 mg/L (100U/mL) penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin and 0.29 g/L L-glutamine in 24-well plates with or without GAC1 (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours. LPS (2 μg/mL) was added and culture conditions maintained for another 24 hours. (Preliminary studies showed that LPS at 2 μg/mL is optimal for PBMC stimulation). At the end of incubation, supernatants were harvested for TNF-α measurement. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion, and the ratio of viable cells to total cells was calculated. To investigate the possible underlying mechanisms, PBMC (2×105) samples from additional 3 asthma patients were cultured in a 96-well plate overnight in serum free medium with or without GAC1 (20 μg/mL). Cells were stimulated with LPS (2μg/mL) for 30 minutes. Whole cell proteins were extracted from three asthma patients PBMCs.

2.9. Western-blot analysis

RAW 264.7 cells (5×105/mL) were pretreated with GAC1 (0, 2.5, 10, 20, 40 μg/mL) for 24 hours, then stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 30min. Purified asthma patient PBMCs (2×106/mL) were pretreated with GAC1 (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours then stimulated for 30 min with LPS (2 μg/mL). Nuclear and whole cell protein were extracted from RAW cells and asthma patient PBMCs (Active Motif nuclear extract kit, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Whole cell and nuclear extract protein concentrations were determined according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate, Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA), and proteins were stored at −80 °C.

Proteins (20–40 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose transfer membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in TBS-Tween 20 solution and were incubated with the following antibodies: anti ERK1/2 (rabbit, 1:1000), p-ERK1/2 (mouse, 1:1000), JNK (rabbit, 1:1000), p-JNK (mouse, 1:1000), p38 (mouse, 1:1000), p-p38 (mouse, 1:1000), p-p65 (rabbit, 1:1000), p65 (rabbit, 1:1000), c-Jun (rabbit, 1:1000), c-Fos (rabbit, 1:1000), p-IκB (mouse, 1:1000), β-actin (rabbit, 1:5000) and histone-H3 (mouse, 1:1000) overnight at 4°C. After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin diluted 1:3000 in TBS-Tween 20 for 1 hour at room temperature with continuous agitation. Reactive bands were visualized using Chemiluminescent HRP Antibody Detection Reagent (Denville Scientific, South Plainfield, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.10. Statistical and data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA). Differences between multiple groups and control were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. Differences between 2 treatments of cells from individual patients were analyzed by paired t test, other dual comparisons by unpaired t tests. A p-value 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Percent inhibition was calculated by comparing values obtained by ELISA to respective controls. Data were analyzed using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and expressed as percent inhibition, as in our previous publication (Jayaprakasam et al., 2013).

3. RESULTS

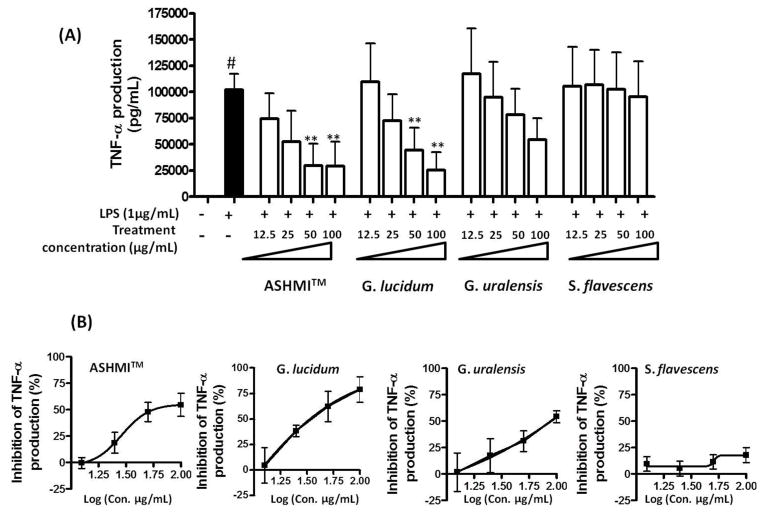

3.1. The ASHMITM constituent G. lucidum extract, but not S. flavescens or G. uralensis extracts significantly suppressed macrophage TNF-α production

To identify the herb(s) in ASHMITM responsible for TNF-α suppression, we compared the effects of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100μg/mL ASHMITM, G. lucidum, S. flavescens, and G. uralensis extracts on RAW 264.7 cell TNF-α production. As expected, LPS stimulation (LPS alone) markedly increased TNF-α production (p<0.05 vs medium). ASHMITM and G. lucidum at 50 and 100 μg/mL concentration significantly suppressed LPS stimulated TNF-α production (p<0.05 vs LPS alone group, Fig. 1A). S. flavescens and G. uralensis had no significant inhibitory effect at any tested concentration. We found that G. lucidum was more potent than S. flavescens or G. uralensis in suppression of macrophage TNF-α production. Calculated IC50 values of ASHMITM, G. lucidum, and G. uralensis were 56.1, 33.8, and 88.9 μg/mL, respectively (no IC50 value of S. flavescens was obtained, Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Effect of ASHMITM and extracts of its constituent herbs on TNF-α production.

(A) RAW 264.7 cells were cultured with or without extracts for 24 hours, and then cultured in the presence of 1 μg/mL LPS for 24 hours. TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. #, p<0.05 vs medium alone culture; **p<0.01 vs. LPS stimulated, but untreated (LPS alone) culture. (B) Percent inhibition was calculated in relation to LPS stimulated untreated cells.

3.2. The G. lucidum methylene chloride fraction suppressed macrophage TNF-α production

Of the two extraction fractions obtained, the triterpenoid-enriched MC fraction (F1) but not the water residue fraction (F2), significantly inhibited LPS-stimulated TNF-α production at 25 μg/ml (equivalent to 250 μg/mL G. lucidum aqueous extract) (eResult 1 and eFig. 1). Therefore, the triterpenoid-enriched MC fraction was used to isolate compounds with anti-TNF-α actions.

3.3. Isolation and identification of G. lucidum ganoderic acids in the MC fraction

Fifteen compounds were isolated and purified from the MC fraction. These compounds were identified by NMR and LC-MS analysis and comparison of the spectroscopic data with those reported in the literature to be ganoderiol F (1)(el Mekkawy et al., 1998), ganoderic acid α (2)(el Mekkawy et al., 1998), ganoderic acid V (3)(Qiao et al., 2005), ganoderic acid H (4)(el Mekkawy et al., 1998), ganoderic acid C2 (5)(Yue et al., 2010), ganolucidic acid A (6)(Min et al., 2000), ganolucidic acid E (7)(Qiao et al., 2005), ganoderic acid C1 (8)(Seo et al., 2009), ganoderenic acid A (9)(Wang and Liu, 2008), ganolucidic acid D (10)(Min et al., 2000), ganoderic acid U (11) (Chen and Yu, 1990), ganoderic acid J (12)(Chen and Yu, 1990), ganoderic acid A (13)(el Mekkawy et al., 1998), ganoderic acid K(14)(Yue et al., 2010), and ganoderenic acid D (15)(Wang and Liu, 2008). 3D-HPLC analysis of aqueous extract of G. lucidum was measured with peaks identified with corresponding G. lucidum triterpenoids isolated (1–15) by comparing the maximum absorption and retention time (eFig. 2).

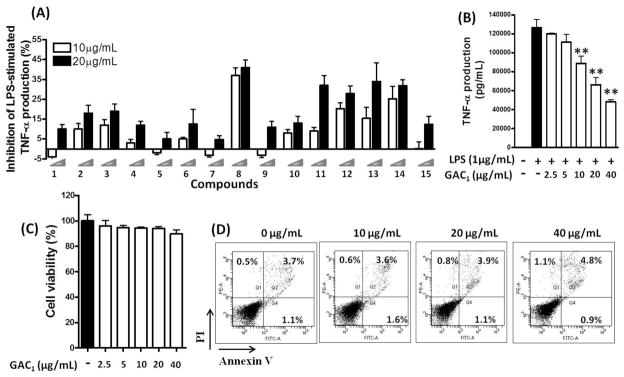

3.4. Effect of GAC1 and other Ganoderma triterpenoids on LPS stimulated TNF-α production

Potential inhibition of TNF-α production by each compound were tested at concentrations of 10 and 20 μg/mL as shown in Fig. 2A. The percent inhibition of compounds 8, 11, 12, 13 and 14 was comparable, with compound 8 (GAC1) being more effective at 20 μg/mL. At 10μg/mL, only compound 8 produced >30 % inhibition.

Fig. 2. Effect of 15 compounds isolated from G. lucidum on TNF-α production.

(A). RAW 264.7 cells were pre-incubated with or without isolated G.lucidum triterpenoids (10 and 20μg/mL) for 24 hours, followed by addition of LPS (1 μg/mL) and culture for additional 24 hours. TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as percent inhibition compared with LPS only group. (B). Concentration dependent GAC1 inhibition of TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. (C). Cell viability of GAC1-treated and LPS-stimulated macrophages. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of 3–6 independent experiments. **p<0.01,*p<0.05 Vs LPS alone. (D). Cells were exposed to 0, 10, 20, 40 μg/mL GAC1 for 24 hours, followed by addition of LPS (1.0 μg/mL) and cultured for an additional 24 hours. Cells were then collected and subjected to Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and analysis by flow cytometry.

We next tested GAC1 at concentrations ranging from 2.5–40 μg/mL. GAC1 suppression of TNF-α was concentration dependent and significant suppression was observed at as low as 10μg/mL (Fig. 2B). The calculated IC50 value (concentration producing 50% inhibition) was 24.5μg/mL (47.7μM). Cell viability was unaffected at any concentration tested by trypan blue staining assay. The percentages of PI (+) and Annexin V (+) cells were all less than 5% at all dose (Fig. 2C, D), considered no-to minimal toxic (Yang et al., 2014) (Yamauchi et al., 2004). GAC1 suppressed up to 60% LPS stimulated TNF-α secretion by RAW 264.7 cells at 40μg/ml, exhibiting 5% PI(+)/Annexin V(+) cells. This demonstrated that suppression of TNF-α production was not due to apoptosis.

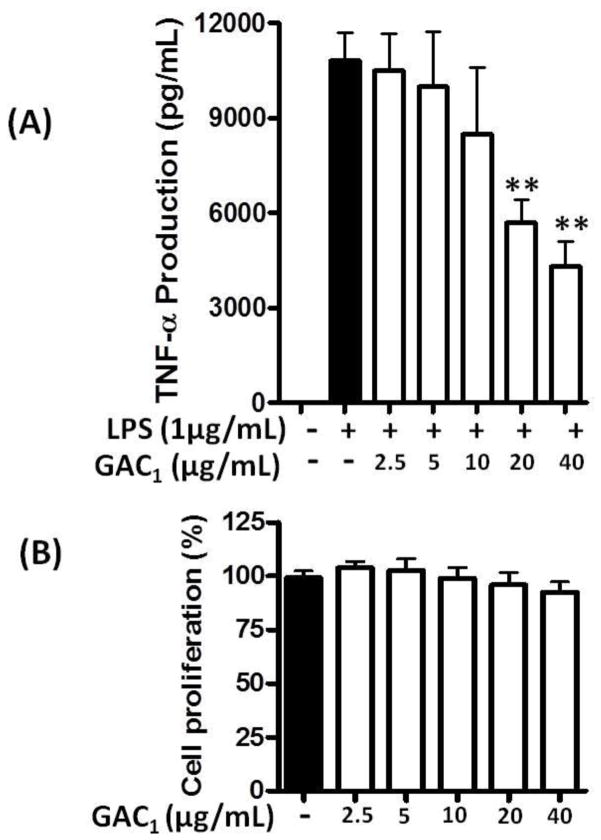

3.5. GAC1 inhibited TNF-α production without affecting cell proliferation

We next tested the effect of simultaneous GAC1 and LPS co-incubation on TNF-α production. RAW264.7 cells were simultaneously treated with GAC1 at various concentrations (0, 2.5,5,10,20 and 40 μg/mL) and LPS (1μg/mL) for 24 hours. As shown in Fig 3A, LPS stimulation (LPS alone) markedly increased TNF-α production (p<0.05 vs medium). Co-administration of GAC1 at 20 and 40 μg/mL concentrations significantly suppressed LPS stimulated TNF-α production (p<0.05 vs LPS alone group). MTT assays showed no effects on proliferation (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. GAC1 inhibited TNF-α production when simultaneously co-incubated with LPS.

(A). RAW 264.7 cells were treated by simultaneous co-incubation with various concentrations of GAC1 and LPS (1.0 μg/mL) for 24 hours. TNF-α levels in cell culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of 3–6 independent experiments. **p<0.01,*p<0.05 vs medium and LPS control groups. (B). RAW264.7 cells were treated with 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/mL GAC1for 24 hours then subjected to MTT cell proliferation assay. Cell proliferation percentage was calculated by comparison with the medium alone group, which was set at 100%.

We also investigated if GAC1 induced overall suppression of constitutive TNF-α production. To this end, RAW264.7 cells were treated with GAC1 at various concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/mL) for 48 hours. No reduction of GAC1 TNF-α production was detected, and 20 and 40μg/mL concentrations slightly increased production (eFig. 3).

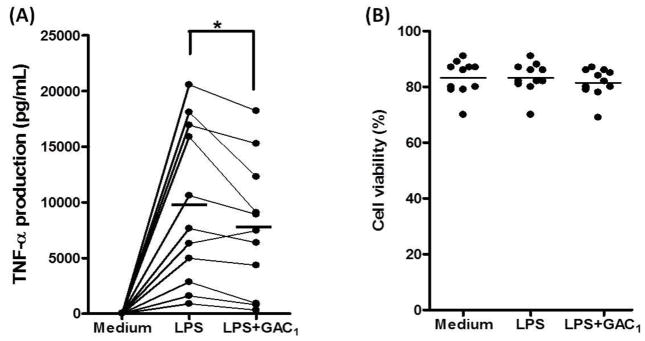

3.6. GAC1 inhibited TNF-α production by PBMCs from asthma patients

Based on the findings that GAC1 non toxically inhibited RAW cells LPS stimulated TNF-α production at IC50 approximately 20μg/mL, we next investigated if this effect would be reproduced in asthma patient PBMCs. LPS stimulation significantly increased TNF-α production by PBMCs from asthma patients (n=11, p<0.05, LPS alone vs medium). Pretreatment with 20 μg/mL GAC1 significantly inhibited TNF-α production (p<0.05 vs LPS alone, Fig. 4A). GAC1 did not affect the percent of viable cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. GAC1 inhibited TNF-α production by PBMCs from asthma patients.

Purified PBMCs were treated with or without GAC1 (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours. LPS (2 μg/mL) was added and culture conditions maintained for additional 24 hours. Supernatants were harvested and TNF-α levels were determined by ELISA. (A). GAC1 (20 μg/mL) inhibition of TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated PBMCs from asthma patients. (B). PBMC viability after treatment with GAC1 (20 μg/mL). * p<0.05, paired t-test, (n=11).

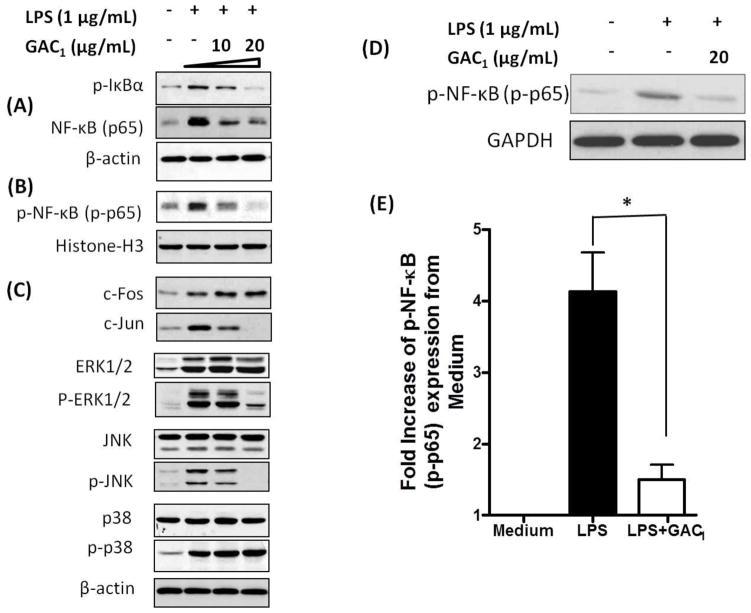

3.7. GAC1 inhibited LPS-stimulated p-IκBα, p-NF-κB expression, and AP-1 and MAPK activation in a murine macrophages and LPS-stimulated p-NF-κB expression in asthma patient PBMCs

RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with GAC1 (0, 10, and 20μg/mL) and stimulated with LPS (1μg/mL). Total protein extract measurements showed that 10 and 20μg/mL GAC1 pretreatment reduced LPS-induced RAW cell p-IκBα and NF-κB (p65) expression, 20 μg/mL being more effective (Fig. 5A). GAC1 pretreatment also reduced nuclear p-p65 levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). In addition, GAC1 inhibited, AP-1 c-Jun, but not c-Fos expression. GAC1 also inhibited JNK and ERK1, ERK2 activation (JNK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation). p38 and p-p38 expression levels were not affected by GAC1 treatment (Fig. 5C). These data showed that GAC1 inhibited NF-κB pathway and partial AP-1 and MAPK family activation.

Fig. 5. GAC1 regulation of NF-κB, AP-1 and MAPK.

RAW 264.7 macrophages were pretreated with GAC1 (0, 10, or 20 μg/mL) for 24 hours, followed by stimulation with LPS (1μg/mL) for 30 minutes. (A). p65, and p-IκBα expression were evaluated by Western-blot analysis of whole cell extracts. (B). Nuclear translocation of p-p65 was evaluated by Western-blot analysis of nuclear extracts. Equal protein loading was verified with Histone-H3 antibody. (C). c-Fos, c-Jun, ERK1/2, p-ERK1/2, JNK, p-JNK, p38, and p-p38 were evaluated by Western-blot analysis of whole cell extracts. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Purified PBMCs were pretreated with GAC1 (20 μg/mL) for 24 hours, followed by stimulation with LPS (2μg/mL) for 30 minutes. (D). Representative Western blotting analysis of NF-κB (p-p65) expression in PBMCs cultured in medium alone, stimulated with LPS, with and without GAC1 treatment. GAPDH expression was used as control. (E). Quantitation of Western blotting analysis of p-NF-κB (p-p65) expression by PBMCs cultured in medium alone, stimulated with LPS, and stimulated and treated with GAC1 (p<0.05 Vs LPS alone, Mean ± S.D., n=3).

LPS stimulation also significantly increased PBMC NF-κB activation (p-p65 expression) (p<0.05, n=3). 20μg/mL GAC1 nearly abrogated this activation as demonstrated by western blot of NF-κB (p-p65) expression, Fig. 5E, F).

4. DISCUSSION

Asthma is a heterogeneous airway disease. Most asthma studies have focused on Th2 cytokine-driven allergic inflammation. More recently, excessive TNF-α production and increased NF-κB expression have been demonstrated to be associated with steroid resistant asthma (Berry et al., 2007;Ito et al., 2008). At present, there is no safe and effective treatment for this type of asthma. Monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α, TNF-α receptors, and TNF-α receptor constructs are currently used to treat certain TNF-α associated disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Crohn’s disease (Gardam et al., 2003;Scheinfeld, 2004). Although a few preliminary studies of small numbers of asthma patients found improvement in lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness, quality-of-life and exacerbation rate following treatment with anti-TNF therapy, such therapy for asthma is limited because of inconsistent findings of efficacy and concern about serious adverse effects (Berry et al., 2007;Brightling et al., 2008).

ASHMITM was previously shown to suppress TNF-α production in a murine asthma model and in cultured macrophages without toxicity (Brown LL et al., 2009;Srivastava et al., 2014). As a first attempt to identify TNF-α inhibitory compounds present in ASHMITM, we compared potential anti-TNF-α effects of extracts of the three herbs in ASHMITM, and found that G. lucidum was more potent than G. uralensis in suppressing macrophage TNF-α production. S. flavescens had negligible inhibitory effect on macrophage TNF-α production. We therefore, focused on identifying G. lucidum active compounds that inhibit TNF-α production using RAW 264.7 cells as a screening tool. We found that the non polar methylene chloride triterpenoid enriched fraction (F1(MC)), but not the was water-soluble, residue after organic solvent extraction (F2), significantly suppressed TNF-α production. Triterpenes and polysaccharides are the predominant biologically active compounds in G. lucidum. (Boh et al., 2007) These two classes of compounds have different effects on immune responses. G. lucidum polysaccharides increase pro-inflammatory cytokine production including TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6 production (Habijanic et al., 2015;Pan et al., 2013), whereas a triterpene-rich extract suppressed inflammatory cytokines (Dudhgaonkar et al., 2009). Why F2 did not show any effect on LPS-stimulated TNF-α production in our study is unknown, but it might be because F2, which was the water-soluble polysaccharides containing fraction after organic solvent extraction, contained other water-soluble compounds that counteracted the polysaccharide stimulation. Since our goal is to identify compounds that inhibit excessive LPS stimulated TNF-α production, we focused on the triterpene rich MC fraction, and isolated and identified G. lucidum triterpenoid compounds. Among the 15 isolated compounds, GAC1 showed greatest inhibition of TNF-α production, and in a dose dependent, non-cytotoxic manner. It is also worth noting that the exact extent to which GAC1 contributes to the effect of G. ludicum MC fraction inhibition of TNF-α production by RAW 264.7 cell TNF-α inhibition is unknown. Several other compounds isolated from the G. ludicum MC fraction including ganoderic acids U, J, A and K produced more than 30% inhibition of TNF-α production at 20μg/mL concentration. These compounds may act additively and/or synergistically with GAC1. Further investigation is required.

Importantly, the effectiveness and safety of GAC1 suppression of TNF-α was also demonstrated in human PBMC from asthma patients. Although various G. lucidum triterpenoids have been isolated, most studies focused on their anti-cancer (Li et al., 2013;Yao et al., 2012) and anti HIV properties (Akbar and Yam, 2011;el Mekkawy et al., 1998). No previous study determined inhibition of TNF-α production by GAC1 or any other G. lucidum triterpenoid compounds in PBMCs from asthma patients.

LPS induces TNF-α through the activation of several intracellular signaling pathways including NF-κB, AP-1 and MAP kinases. GAC1 reduction of p-IκB levels in total cell protein and p-p65 in nuclear protein demonstrated that it inhibited the NF-κB signaling pathway. It also partially suppressed the AP-1 family as shown by reduction of c-Jun, but not c-fos expression, and the MAPK pathway as shown by suppression of p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK, but not p-p38 expression. Therefore, in addition to the effect of GAC1 on NF-κB, GAC1 suppression of TNF-α may also be partially attributed to suppression of MAPK and AP-1. Because of the limited availability of human asthma patient PBMCs, we focused on the NF-κB pathway, and demonstrated that GAC1 also suppressed p-p65 expression. These findings demonstrate that non-toxic suppression of TNF-α production by GAC1 is due, at least in part, to suppression of NF-κB signaling pathway.

TNF-α is a key cytokine involved in the immediate host defense against invading microorganisms prior to activation of the adaptive immune system (Medzhitov and Janeway, Jr., 2000). It also inhibits tumorigenesis and viral replication (Kumar et al., 2013;Landskron et al., 2014). However, excessive levels of TNF-α have been implicated in mediating or exacerbating a number of refractory inflammatory diseases including Crohn’s disease (CD) (Brynskov et al., 2002), rheumatoid arthritis (Choy and Panayi, 2001), and asthma (Brightling et al., 2008). Anti-TNF-α medications, including receptor constructs and monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α, are currently used to treat inflammatory bowel disease and arthritis, and are being explored as treatments for recalcitrant asthma. Unfortunately, adverse effects, including lymphoma and infections have been associated with current TNF blockers (Scheinfeld, 2004). Therefore developing safe and effective natural TNF-α inhibitors may be of value in treating excessive TNF-α associated condition. If GAC1 would affect cancer and infections is unknown, but previous publication showed that GAC1 exhibits anti- HIV-1 (el Mekkawy et al., 1998) and anti-cancer cell activities properties (Gao et al., 2002). We found that GAC1 suppression of TNF-α production is not via induction of cell death or apoptosis, but due, at least partially, to modulation of cell signaling pathways. In addition, we found that GAC1 does not cause overall TNF-α production suppression. RAW 264.7 cells constitutively produce low levels of TNF-α. We found that GAC1 co-incubation at 20 and 40μg/mL slightly but significantly increased constitutive TNF-α production. This effect is similar to the G. lucidum polysaccharide immune stimulatory effect on non LPS stimulated cells. (Habijanic et al., 2015;Pan et al., 2013). Taken together, GAC1 treatment may be of less concern regarding adverse effect than current anti-TNF-α therapy. The precise mechanisms underlying GAC1 regulatory effect on TNF-α and other cytokines are unknown and require further investigation.

In conclusion, we for the first time, demonstrated that GAC1 isolated from G. lucidum, an ASHMITM herbal constituent, inhibited TNF-α production by LPS stimulated murine macrophages and asthma patients PBMCs; and that this effect was associated with suppression of the NF-κB signaling pathway and in part suppression of AP1 and MAPK pathways. GAC1 may have potential as a novel therapy for treatment of TNF-α associated asthma and other inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Ganoderic acid C1 (G. lucidum) inhibits LPS-evoked TNF-α produced by macrophages

Ganoderic acid C1 reduces LPS-evoked TNF-α produced by PBMCs from asthma patients

Ganoderic acid C1 inhibition of TNF-α production is associated with decreased NF-κB

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NIH/NCCAM center grant # 1P01 AT002644725-01 “Center for Chinese Herbal Therapy (CHT) for Asthma”, The Sean Parker Foundation, “ASHMI active compounds for asthma therapy”, The Winston Wolkoff Fund for Integrative Medicine for Allergies and Wellness, and partially supported by a new faculty start up fund of Utah State University to Jixun Zhan.

We thank Henry Ehrlich and Brian Schofield for asistance in manuscript preparation, and Dr. Hugh A. Sampson for his continued support.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosure

Dr. Xiu-Min Li shares the patent on ASHMITM (PCT/US05/08600 for ASHMITM) with Herbal Spring LLC. The other authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Akbar R, Yam WK. Interaction of ganoderic acid on HIV related target: molecular docking studies. Bioinformation. 2011;7:413–417. doi: 10.6026/97320630007413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Brightling C, Pavord I, Wardlaw A. TNF-alpha in asthma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boh B, Berovic M, Zhang J, Zhi-Bin L. Ganoderma lucidum and its pharmaceutically active compounds. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2007;13:265–301. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(07)13010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brightling C, Berry M, Amrani Y. Targeting TNF-alpha: a novel therapeutic approach for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LL, Rusinova E, Li X. Development of an Efficient Fractionation Procedure for the Identification of Active Compounds in the Complex ASHMI (Anti-Asthma Herbal Medicine Intervention) Formula. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009;123(2):S256. [Google Scholar]

- Brynskov J, Foegh P, Pedersen G, Ellervik C, Kirkegaard T, Bingham A, Saermark T. Tumour necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme (TACE) activity in the colonic mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51:37–43. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. National Center for Health Statistics: Asthma. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm.

- Chen RY, Yu DQ. studies on the ganderma triterpenoids. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 1990;25:940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zong C, Gao Y, Cai R, Fang L, Lu J, Liu F, Qi Y. Curcumol exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by interfering with the JNK-mediated AP-1 pathway in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;723:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EH, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:907–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Yuan H, Yi J, Lu Y, Wei Q, Guo C, Wu J, Yuan L, He Z. Gossypol acetic acid induces apoptosis in RAW264.7 cells via a caspase-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway. J Vet Sci. 2013;14:281–289. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2013.14.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme FM, Ni CM, Greenstone I, Lasserson TJ. Addition of long-acting beta2-agonists to inhaled steroids versus higher dose inhaled steroids in adults and children with persistent asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD005533. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005533.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhgaonkar S, Thyagarajan A, Sliva D. Suppression of the inflammatory response by triterpenes isolated from the mushroom Ganoderma lucidum. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:1272–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el Mekkawy S, Meselhy MR, Nakamura N, Tezuka Y, Hattori M, Kakiuchi N, Shimotohno K, Kawahata T, Otake T. Anti-HIV-1 and anti-HIV-1-protease substances from Ganoderma lucidum. Phytochemistry. 1998;49:1651–1657. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JJ, Min BS, Ahn EM, Nakamura N, Lee HK, Hattori M. New triterpene aldehydes, lucialdehydes A-C, from Ganoderma lucidum and their cytotoxicity against murine and human tumor cells. Chem Pharm Bull(Tokyo) 2002;50:837–840. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardam MA, Keystone EC, Menzies R, Manners S, Skamene E, Long R, Vinh DC. Anti-tumour necrosis factor agents and tuberculosis risk: mechanisms of action and clinical management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:148–155. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjurow D, Grzelewski T, Sobocinska A, Stelmach I. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in pediatric asthma. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2009;3:143–148. doi: 10.2174/187221309788489797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2001;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habijanic J, Berovic M, Boh B, Plankl M, Wraber B. Submerged cultivation of Ganoderma lucidum and the effects of its polysaccharides on the production of human cytokines TNF-alpha, IL-12, IFN-gamma, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-17. N Biotechnol. 2015;32:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Herbert C, Siegle JS, Vuppusetty C, Hansbro N, Thomas PS, Foster PS, Barnes PJ, Kumar RK. Steroid-resistant neutrophilic inflammation in a mouse model of an acute exacerbation of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:543–550. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0028OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasam B, Doddaga S, Wang R, Holmes D, Goldfarb J, Li XM. Licorice flavonoids inhibit eotaxin-1 secretion by human fetal lung fibroblasts in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:820–825. doi: 10.1021/jf802601j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakasam B, Yang N, Wen M, Wang R, Goladfarb J, Sampson H, Li X-M. Constituents of the anti-asthma herbal formula ASHMITM synergistically inhibit IL-4 and IL-5 secretion by murine Th2 memory cells, and eotaxin by human lung fibroblasts in vitro. J Integr Med. 2013;11(3):195–205. doi: 10.3736/jintegrmed2013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly I, Fitzpatrick P. Sub-optimal asthma control in teenagers in the midland region of Ireland. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:851–854. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0725-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Pieper K, Patil SP, Busse P, Yang N, Sampson H, Li XM, Wisnivesky JP, Kattan M. Safety and tolerability of an antiasthma herbal Formula (ASHMI) in adult subjects with asthma: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation phase I study. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:735–743. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Sohn JH, Choi JM, Lee JH, Hong CS, Lee JS, Park JW. Alveolar macrophages play a key role in cockroach-induced allergic inflammation via TNF-alpha pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Abbas W, Herbein G. TNF and TNF receptor superfamily members in HIV infection: new cellular targets for therapy? Mediators Inflamm. 2013;484378 doi: 10.1155/2013/484378. (ePub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landskron G, De la FM, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;149185 doi: 10.1155/2014/149185. (ePub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Deng YP, Wei XX, Xu JH. Triterpenoids from Ganoderma lucidum and their cytotoxic activities. Nat Prod Res. 2013;27:17–22. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.652961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Weir D, Busse P, Yang N, Zhou Z, Emala C, Li XM. The Flavonoid 7,4′-Dihydroxyflavone Inhibits MUC5AC Gene Expression, Production, and Secretion via Regulation of NF-kappaB, STAT6, and HDAC2. Phytother Res. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ptr.5334. (ePub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immunity. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:44. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min BS, Gao JJ, Nakamura N, Hattori M. Triterpenes from the spores of Ganoderma lucidum and their cytotoxicity against meth-A and LLC tumor cells. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2000;48:1026–1033. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan K, Jiang Q, Liu G, Miao X, Zhong D. Optimization extraction of Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides and its immunity and antioxidant activities. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;55:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, Valacer DJ, Weiss ST. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1454–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y, Yang YK, Dong XC, Qiu MH. 13C NMR Chemical Shifts of Ganderma Triterpenoids: A Meta-Analysis. Chinese Journal of Megnetic Resonance. 2005;22:437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld N. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:280–294. doi: 10.1080/09546630410017275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HW, Hung TM, Na M, Jung HJ, Kim JC, Choi JS, Kim JH, Lee HK, Lee I, Bae K, Hattori M, Min BS. Steroids and triterpenes from the fruit bodies of Ganoderma lucidum and their anti-complement activity. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1573–1579. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-2109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava KD, Dunkin D, Liu C, Yang N, Miller RL, Sampson HA, Li XM. Effect of Antiasthma Simplified Herbal Medicine Intervention on neutrophil predominant airway inflammation in a ragweed sensitized murine asthma model. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau LM, Kavanaugh A, Wasserman SI. The role of monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of severe asthma. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5:183–194. doi: 10.1177/1753465811400489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–57. 437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Liu JK. Highly oxygenated lanostane triterpenoids from the fungus Ganoderma applanatum. Chem Pharm Bull(Tokyo) 2008b;56:1035–1037. doi: 10.1248/cpb.56.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen MC, Wei CH, Hu ZQ, Srivastava K, Ko J, Xi ST, Mu DZ, Du JB, Li GH, Wallenstein S, Sampson H, Kattan M, Li XM. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-asthma herbal medicine intervention in adult patients with moderate-severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi R, Morita A, Yasuda Y, Grether-Beck S, Klotz LO, Tsuji T, Krutmann J. Different susceptibility of malignant versus nonmalignant human T cells toward ultraviolet A-1 radiation-induced apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:477–483. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Patil S, Zhuge J, Wen MC, Bolleddula J, Doddaga S, Goldfarb J, Sampson HA, Li XM. Glycyrrhiza uralensis flavonoids present in anti-asthma formula, ASHMI, inhibit memory Th2 responses in vitro and in vivo. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1381–1391. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Wang J, Liu C, Song Y, Zhang S, Zi J, Zhan J, Masilamani M, Cox A, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson H, Li XM. Berberine and limonin suppress IgE production by human B cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from food-allergic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(5):556–564.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Li G, Xu H, Lu C. Inhibition of the JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway by ganoderic acid A enhances chemosensitivity of HepG2 cells to cisplatin. Planta Med. 2012;78:1740–1748. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue QX, Song XY, Ma C, Feng LX, Guan SH, Wu WY, Yang M, Jiang BH, Liu X, Cui YJ, Guo DA. Effects of triterpenes from Ganoderma lucidum on protein expression profile of HeLa cells. Phytomedicine 2010. 2010;17:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Srivastava K, Wen MC, Yang N, Cao J, Busse P, Birmingham N, Goldfarb J, Li XM. Pharmacology and immunological actions of a herbal medicine ASHMI on allergic asthma. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1047–1055. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.