Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate dose-response associations between misperceived weight and 32 health risk behaviors in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents.

Methods

Participants included 13,864 US high school students in the 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Comparing the degree of agreement between perceived and reported actual weight, weight misperception was determined as 5 categories. Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analyses evaluated associations of weight misperception with 32 health risk behaviors.

Results

Both underestimated and overestimated weight were statistically significantly associated with all 32 health risk behaviors in a dose-response manner after adjustment for age, sex and race/ethnicity, where greater weight misperception was associated with higher engagement in health risk behaviors.

Conclusions

Understanding potential impacts of weight misperception on health risk behaviors could improve interventions that encourage healthy weight perception and attainment for adolescents.

Keywords: adolescent, health risk behaviors, high school, misperceived weight, Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Weight misperception is increasingly recognized as a potentially important health risk marker in adolescents. A large proportion of adolescents incorrectly perceive themselves as being underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese.1-3 For example, in a national sample of high school students, 23.1% underestimated their weight and 20.7% overestimated their weight.4 Studies have demonstrated that adolescents' perceived weight status is more strongly associated with psychological well-being and health risk behaviors than actual weight status.2,5-10 Both overestimation and underestimation of weight are associated with greater health risk in adolescents.5-7,11

Understanding relations between weight misperception and health risk behaviors is important because accurately perceiving oneself has been associated with greater motivation to change harmful behaviors.12 Previous studies showed associations of weight misperception with several health-related factors in adolescents, including mental health (eg, depression, anxiety, suicide, stress, and psychosocial distress), dieting and physical inactivity.4,6,8-10,13-15 However, little is known about associations of misperceived weight with health behaviors related to safety and violence (eg, drinking and driving, physical fighting, dating violence, seatbelt use, condom use) or substance use (eg, smoking, alcohol, illicit drugs). Furthermore, prior studies frequently dichotomize participants as accurate perceivers and inaccurate perceivers,14 or categorize participants as those who underestimate, correctly estimate, or overestimate.16-18 A larger number of weight misperception categories will allow for graded, dose-response associations to be evaluated. The presence of dose-response relations are an important component of Hill's criteria for causal inference.19 Finally, most studies to date used study samples with limited generalizability; consequently, there is a need for nationally representative study populations.5,7,8,10,13-18

Targeting weight misperception may facilitate the adoption of healthy behaviors among adolescents.12 Because overweight/obesity during adolescence increase risks for cardiovascular disease in adulthood, and weight misperception will limit success on the changes of lifestyle behaviors (physical activity, diet, etc.), targeting youth with misperceived weight may improve effectiveness of overweight/obesity prevention interventions.12,20 Consequently, objectives of this study were to evaluate whether weight over- and underestimation are associated with 32 health risk behaviors in 4 categories (safety/violence, mental health, substance use, and dieting/physical activity) in a dose-response manner, in a nationally representative sample of US high school students. We hypothesized that adolescents would be more likely to report unhealthy behaviors in a dose-response manner, to the degree that their perceived weight was incongruent with reported actual weight.

Methods

Data Source

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) monitors health risk behaviors that contribute to the major causes of mortality, morbidity, injury, and social problems among adolescents. A 3-stage cluster sample design was used to produce a nationally representative sample of 9th through 12th grade public and private high school students in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Each school district YRBS employs a 2-stage, cluster sample design to produce a representative sample of students in grades 9–12 in its jurisdiction. In the first sampling stage, schools are selected with probability proportional to school enrollment size. In the second sampling stage, intact classes of a required subject or intact classes during a required period (eg, second period) are selected randomly. All students in sampled classes are eligible to participate. A weight is applied to each student record to adjust for student nonresponse and the distribution of students by grade, sex, and race/ethnicity in each jurisdiction. Therefore, weighted estimates are representative of all students in grades 9–12 in each jurisdiction. More details on the sampling strategy are provided elsewhere.21

Analyses were based on cross-sectional data from the 2011 YRBS, which assessed self-reported height, weight, and health risk behaviors. A total of 15,425 participants completed surveys; the overall response rate was 71%. Of these, 1561 were missing data related to: (1) self-reported height or weight (N = 1140); (2) weight perception (N = 285); (3) age (N = 62); (4) sex (N = 61); and (5) race/ethnicity (N = 315). Some respondents had multiple missing values, resulting in 13,864 participants available for analyses. We compared the prevalence of health risk behaviors between participants with complete data (N = 13,864) vs participants with missing data (N = 1561), and found that participants with complete data were more likely (p < .05) to report healthier levels than participants with missing data for 28 of the 32 evaluated behaviors (ie, all health risk behavior variables other than being bullied, considered suicide, trying to lose weight, and not eating breakfast). Furthermore, particpants with complete data were significantly (p < .05) more likely than participants with missing data to have healthy reported actual weight, healthy perceived weight, be female, and be non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity.

Independent Variable: Weight Misperception

Perceived weight (PW) was assessed via participants' self-reported response to the question: How do you describe your weight? with response categories of “very underweight” (PW score=1), “slightly underweight” (PW score=2), “about the right weight” (PW score=3), “slightly overweight” (PW score=4), or “very overweight” (PW score=5).

Reported actual weight (RAW) was estimated via body mass index (BMI), calculated from self-reported height and weight (kg/m2). BMI values were compared with sex- and age-specific reference data from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts22,23 to create BMI percentiles for each student. Age- and sex-specific BMI percentiles were categorized utilizing standard criteria1,17,24,25 as follows: extremely underweight (<1st percentile; RAW score=1), underweight (≥1st and <5th percentile; RAW score=2), healthy (≥5th and <85th percentile; RAW score=3), overweight (≥85th and <95th percentile; RAW score=4), and obese (≥95th percentile; RAW score=5). Self-reported weight and height underestimate the prevalence of adolescent overweight;26 consequently, directly measured height and weight are preferred. However, previous studies demonstrated that self-reported height and weight tend to be relatively accurate, can be used as a reliable alternative in the absence of direct measures, and remain an important surveillance tool.7,26-31

A weight misperception (WM) score that compared the degree of agreement between PW and RAW was created by subtracting RAW score (range 1-5, details above) from PW score (range 1-5, details above). The WM score included the following 5 categories: greatly underestimated weight (WM score range -2 to -4); moderately underestimated weight (WM score=-1); accurately perceived weight (WM score=0) which was the reference group; moderately overestimated weight (WM score=1); and greatly overestimated weight (WM score range 2 to 4), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Definition of Misperception Categoriesa.

| Perceived Weight | Reported Actual Weight | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Underweight (<1st percentile) (1) | Underweight (≥1st & <5th percentile) (2) | Healthy Weight (≥5th & <85th percentile)(3) | Overweight (≥85th & <95th percentile) (4) | Obese (≥95th percentile) (5) | |

| Very Underweight (1) | 0 | -1 | -2 | -3 | -4 |

| Slightly Underweight (2) | 1 | 0 | -1 | -2 | -3 |

| About the Right Weight (3) | 2 | 1 | 0 | -1 | -2 |

| Slightly Overweight (4) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Very Overweight (5) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Note.

Numbers in parentheses represent scores assigned to each category. Body mass index percentiles are derived from sex- and age-specific reference data from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts.

Dependent Variable: Health Risk Behaviors

The 32 risk behaviors included in the analyses are standard health risk factors assessed in adolescents and classified into 4 domains (Appendix Table A): (1) safety and violence (rarely/never wore seatbelt; drink and drive; carry a weapon at school; not go to school due to feeling unsafe; threatened or injured with weapon at school; property stolen/damaged; fight at school; hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose; physically forced to have sex; not use condom; and being bullied); (2) mental health (felt sad/hopeless; considered suicide; planned suicide; attempted suicide; and suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse); (3) substance use (current cigarette use; current alcohol use; current marijuana use; current cocaine use; lifetime heroin use; lifetime methamphetamines use; lifetime hallucinogenic drug use; lifetime ecstasy use; and lifetime steroid use); (4) dieting and physical in activity (trying to lose weight; fasted to lose weight; diet pills to lose weight; vomited to lose weight; not eat breakfast; played video/computer game; and not attend sports teams). Detailed sampling procedures and questionnaires for the 2011 YRBS can be found elsewhere.32

Appendix Table A. Summary of 32 Health Risk Behaviors Survey Questions, 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey32.

| Health Risk Behaviors | Questions |

|---|---|

| Safety & Violence | |

|

| |

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | How often do you wear a seatbelt when riding in a car driven by someone else? 1: Never/Rarely; 2: Sometimes/Most of the time/Always |

| Drink & drive | During the past 30 days, how many times did you drive a car or other vehicle when you had been drinking alcohol? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ time |

| Carry a weapon at school | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you carry a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property? 1: 0 days; 2: 1+ day |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school because you felt you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school? 1: 0 days; 2: 1+ day |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | During the past 12 months, had someone threatened or injured you with a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Property stolen/damaged | During the past 12 months, how many times has someone stolen or deliberately damaged your property such as your car, clothing, or books on school property? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ time |

| Fight at school | During the past 12 months, how many times were you in a physical fight on school property? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ time |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | During the past 12 months, did your boyfriend or girlfriend ever hit, slap, or physically hurt you on purpose? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Physically forced to have sex | Have you ever been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Not use condom | The last time you had sexual intercourse, did you or your partner use a condom? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Being bullied | During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property? 1: Yes; 2: No |

|

| |

| Mental Health | |

| Felt sad/hopeless | During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for 2 weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Considered suicide | During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Planned suicide | During the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Attempted suicide | During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ time |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | If you attempted suicide during the past 12 months, did any attempt result in an injury, poisoning, or overdose that had to be treated by a doctor or nurse? 1: I did not attempt suicide during the past 12 months; 2: Yes; 3: No |

|

|

|

| Substance Use | |

|

| |

| Current cigarette use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes on school property? 1: 0 days; 2: 1+ day |

| Current alcohol use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol on school property? 1: 0 days; 2: 1+ day |

| Current marijuana use | During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana on school property? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

| Current cocaine use | During the past 30 days, how many times did you use any form of cocaine, including powder, crack, or freebase? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

| Lifetime heroin use | During your life, how many times have you used heroin (also called smack, junk, or China White)? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

|

| |

| Health Risk Behaviors | Questions |

|

| |

| Lifetime methamphetamines use | During your life, how many times have you used methamphetamines (also called speed, crystal, crank, or ice)? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | During your life, how many times have you used hallucinogenic drugs, such as LSD, acid, PCP, angel dust, mescaline, or mushrooms? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | During your life, how many times have you used ecstasy (also called MDMA)? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ times |

| Lifetime steroid use | During your life, how many times have you taken steroid pills or shots without a doctor's prescription? 1: 0 times; 2: 1+ time |

|

| |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | |

| Trying to lose weight | Were you trying to lose weight? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Fasted to lose weight | During the past 30 days, did you go without eating for 24 hours or more (also called fasting) to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Diet pills to lose weight | During the past 30 days, did you take any diet pills, powders, or liquids without a doctor's advice to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight? (Do not include meal replacement products such as Slim Fast.) 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Vomited to lose weight | During the past 30 days, did you vomit or take laxatives to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight? 1: Yes; 2: No |

| Not eat breakfast | During the past 7 days, on how many days did you eat breakfast? 1: 0-6 days; 2: 7 days |

| Played video/computer game | On an average school day, how many hours do you play video or computer games or use a computer for something that is not school work? (Include activities such as Xbox, PlayStation, Nintendo DS, iPod touch, Facebook, and the Internet.) 1: 0-2 hours per day; 2: 3+ hours per day |

| Not attend sports teams | During the past 12 months, on how many sports teams did you play? (Count any teams run by your school or community groups.) 1: 0 team; 2: 1+ teams |

Covariates

All participants were in grades 9 through 12, and self-reported age in the following categories: 12 years or younger, 13 years, 14 years, 15 years, 16 years, 17 years, or 18 years or older. Race/ethnicity was self-reported, and categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latino, and other. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate whether cognitive abilities may confound associations between weight misperception and health risk behaviors. The national YRBS did not assess cognitive abilities, consequently these sensitivity analyses were performed in the 2007- and 2009-combined Rhode Island YRBS (N = 5423), where students were asked: During the past 12 months, how would you describe your grades in school? with response options “Mostly A's”, “Mostly B's”, “Mostly C's”, “Mostly D's”, and “Mostly F's.” Socioeconomic status (SES) is not available on the YRBS. Consequently, no adjustment could be made in the analyses. Previous studies showed minimal impact of adjustment for SES on associations of weight misperception with health risk behaviors in adolescents, which suggests risk for residual confounding by SES is fairly low,14,33 although the possiblity of residual confounding due to SES remains in the current analyses.34

Statistical Analyses

Weighted kappa statistics were calculated to measure agreement between perceived and reported actual weight. The kappa coefficient is a more robust measure than computing percent agreement because it considers the agreement caused by chance.35 A kappa of 0.41–0.60 indicates moderate agreement and kappa of 0.21–0.40 indicates fair agreement.16

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to examine associations of misperceived weight with 32 health risk behaviors, adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. The reference category for the the 5-level independent variable (WM score) was correctly perceived weight (WM score=0). Analyses were initially stratified by sex, and formal tests for effect modification in sex-pooled analyses evaluated if there was evidence of effect modification by sex.

Further sensitivity analyses evaluated whether cognitive abilities may be a confounder in the 2007- and 2009-combined Rhode Island YRBS (N = 5423; described above). All data analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina), and accounted for cluster sample design.

Results

Demographic analyses demonstrated that there were similar proportions of boys and girls (48.9% girls; Table 2). Non-Hispanic whites accounted for a high percentage (58.4%) of participants, followed by Hispanics (19.4%) and non-Hispanic blacks (13.4%; Table 2). Age was generally similar across category of misperceived weight, with slightly higher ages for those who overestimated their weight (Table 2). Girls were more likely to overestimate their weight than boys. Non-Hispanic black participants were more likely to underestimate their weight, and conversely, non-Hispanic white participants were more likely to overestimate their weight (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics According to Weight Misperception, 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Demographic Characteristic | Total (N = 13,864) | Greatly Underestimated Weight (N = 599) | Moderately Underestimated Weight (N = 3460) | Correctly Perceived Weight (N = 8213) | Moderately Overestimated Weight (N = 1456) | Greatly Overestimated Weight (N = 136) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SE)a | 16.02 (0.03) | 16.03 (0.07) | 16.00 (0.04) | 16.03 (0.03) | 16.10 (0.04) | 16.19 (0.15) | .008 |

|

| |||||||

| Sex, % femaleb | 48.9 | 26.2 | 34.7 | 52.1 | 72.0 | 59.0 | <.0001 |

|

| |||||||

| Race/Ethnicityb | <.0001 | ||||||

| White, NH, % | 58.4 | 41.9 | 57.4 | 59.2 | 61.7 | 58.9 | |

| Black, NH, % | 13.4 | 24.0 | 14.8 | 13.1 | 8.2 | 9.5 | |

| Hispanic, % | 19.4 | 25.8 | 18.5 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 21.5 | |

| Other, % | 8.9 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 8.4 | 10.7 | 10.1 | |

Note.

Data are reported as weighted means (Standard Errors). The p value was calculated using unadjusted linear regression.

Data are reported as weighted percentages. The p values were calculated using the χ2 test.

Distributions of weight perception within each reported actual weight status category are shown in Table 3. Whereas 69.2% of 9th-to-12th grade students were of healthy weight at the time of the 2011 YRBS, only 56.7% believed that they were “about the right weight.” The bolded diagonal cells in the table represent participants whose perceived weight was concordant with their reported actual weight (59.3%). The values above the diagonal bold cells represent those who overestimated their weight, and the values below the diagonal bold cells represent those who underestimated their weight. The weighted kappa statistics indicated only a moderate agreement (kappa = 0.52).

Table 3. Frequencies of Perceived Weight in Relation to Actual Weight; 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Perceived Weight | Reported Actual Weight, N (Weighted %) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Underweight | Underweight | Healthy Weight | Overweight | Obese | ||

| Very Underweight | 27(0.16%) | 31(0.22%) | 169(1.12%) | 23(0.15%) | 21(0.15%) | 271(1.79%) |

| Slightly Underweight | 52(0.40%) | 128(1.02%) | 1402(10.86%) | 48(0.27%) | 30(0.19%) | 1660(12.74%) |

| About the Right Weight | 39(0.29%) | 78(0.53%) | 6539(47.57%) | 872(6.22%) | 308(2.08%) | 7836(56.69%) |

| Slightly Overweight | 3(0.04%) | 5(0.03%) | 1228(8.99%) | 1137(7.80%) | 1155(7.85%) | 3528(24.70%) |

| Very Overweight | 3(0.03%) | 1(0.01%) | 85(0.64%) | 98(0.64%) | 382(2.76%) | 569(4.08%) |

| Total | 124(0.92%) | 243(1.80%) | 9423(69.17%) | 2178(15.08%) | 1896(13.03%) | 13864(100.00%) |

Analyses showed that 4.0%, 25.1%, 59.3%, 10.6%, and 1.0% of participants greatly underestimated, moderately underestimated, correctly perceived, moderately overestimated, and greatly overestimated weight, respectively (Table 4). When compared to participants who accurately perceived their weight, those who either overestimated or underestimated their weight had significantly higher odds of engaging in health risk behaviors in a graded, dose-response manner, adjusted for age, sex and race/ethnicity (Table 4). Greatly underestimated weight and greatly overestimated weight were significantly associated with all health risk behaviors compared with correctly perceived weight, although strengths of association varied across behaviors. Except for 2 health risk behaviors (‘physically forced to have sex’ and ‘not eat breakfast’), students with greatly overestimated weight demonstrated higher odds ratios than students with greatly underestimated weight for all health risk behaviors. Sex-stratified analyses showed overall similar patterns between boys and girls, although strengths of association varied somewhat across behaviors (Appendix Table B-C). Formal tests for interaction of weight misperception by sex demonstrated few significant interaction terms (see Appendix Table D), consequently analyses were sex-pooled for primary analyses, and adjusted for sex.

Table 4. Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors According to Misperceived Weight Category, Adjusted for Age, Sex and Race/Ethnicity; 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Health Risk Behaviors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Greatly Underestimated Weight |

Moderately Underestimated Weight |

Correctly Perceived Weight |

Moderately Overestimated Weight |

Greatly Overestimated Weight |

|

| Safety & Violence | |||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | 2.38(1.60-3.55)*** | 1.26(1.03-1.55)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.02(0.78-1.33) | 3.31(1.72-6.38)*** |

| Drink and drive | 1.60(1.19-2.16)** | 1.09(0.90-1.31) | 1.00(ref) | 1.05(0.83-1.33) | 2.31(1.12-4.76)* |

| Carry a weapon at school | 2.05(1.28-3.29)** | 1.27(1.02-1.57)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.36(0.97-1.91) | 2.35(1.23-4.52)* |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 3.05(2.04-4.58)*** | 1.20(0.97-1.48) | 1.00(ref) | 1.25(0.94-1.65) | 3.38(1.86-6.14)*** |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | 2.20(1.51-3.21)*** | 1.17(0.98-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 1.40(1.03-1.90)* | 3.70(2.00-6.83)*** |

| Property stolen/damaged | 1.18(0.88-1.57) | 0.99(0.86-1.13) | 1.00(ref) | 1.16(0.96-1.40) | 2.00(1.30-3.08)** |

| Fight at school | 1.59(1.25-2.02)*** | 1.06(0.92-1.23) | 1.00(ref) | 0.96(0.76-1.22) | 2.08(1.28-3.38)** |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 1.46(1.03-2.07)* | 0.98(0.85-1.14) | 1.00(ref) | 1.16(0.94-1.43) | 2.65(1.34-5.23)** |

| Physically forced to have sex | 2.70(1.83-3.98)*** | 1.07(0.87-1.32) | 1.00(ref) | 1.41(1.08-1.84)* | 1.84(0.79-4.26) |

| Not use condom | 1.43(0.91-2.26) | 1.18(0.98-1.42) | 1.00(ref) | 1.29(0.98-1.70) | 3.06(1.49-6.25)** |

| Being bullied | 1.88(1.38-2.54)*** | 1.21(1.03-1.43)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.57(1.37-1.81)*** | 2.29(1.43-3.67)*** |

|

| |||||

| Mental Health | |||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | 1.58(1.27-1.96)*** | 1.29(1.15-1.46)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.61(1.40-1.86)*** | 2.44(1.46-4.06)*** |

| Considered suicide | 1.81(1.32-2.48)*** | 1.27(1.07-1.51)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.57(1.35-1.83)*** | 3.20(1.91-5.34)*** |

| Planned suicide | 1.88(1.38-2.56)*** | 1.18(1.02-1.38)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.63(1.37-1.94)*** | 4.19(2.54-6.92)*** |

| Attempted suicide | 1.86(1.30-2.66)*** | 1.15(0.91-1.44) | 1.00(ref) | 1.70(1.27-2.27)*** | 4.49(2.36-8.53)*** |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | 3.11(1.82-5.33)*** | 1.80(1.26-2.56)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.89(1.19-3.00)** | 8.23(3.25-20.86)*** |

|

| |||||

| Substance Use | |||||

| Current cigarette use | 2.58(1.69-3.93)*** | 1.16(0.92-1.48) | 1.00(ref) | 1.17(0.75-1.81) | 2.72(1.30-5.69)** |

| Current alcohol use | 2.68(1.96-3.65)*** | 1.26(1.00-1.57)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.41(1.09-1.82)** | 4.23(2.22-8.06)*** |

| Current marijuana use | 1.89(1.33-2.69)*** | 1.05(0.81-1.36) | 1.00(ref) | 0.97(0.71-1.32) | 4.03(2.36-6.88)*** |

| Current cocaine use | 1.99(1.25-3.18)** | 1.21(0.83-1.77) | 1.00(ref) | 1.08(0.73-1.62) | 6.32(2.90-13.78)*** |

| Lifetime heroin use | 3.84(2.52-5.84)*** | 1.36(0.98-1.88) | 1.00(ref) | 1.33(0.83-2.14) | 6.06(3.31-11.10)*** |

| Lifetime methamphetamines use | 3.50(2.33-5.27)*** | 1.06(0.80-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 1.30(0.91-1.84) | 5.45(3.12-9.52)*** |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | 1.73(1.19-2.52)** | 1.12(0.88-1.42) | 1.00(ref) | 1.09(0.85-1.40) | 3.70(2.13-6.40)*** |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 1.97(1.40-2.79)*** | 1.14(0.93-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(1.01-1.63)* | 2.65(1.55-4.54)*** |

| Lifetime steroid use | 4.01(2.78-5.79)*** | 1.29(1.00-1.67) | 1.00(ref) | 1.41(0.93-2.14) | 8.33(4.36-15.94)*** |

|

| |||||

| Dieting and Physical Inactivity | |||||

| Trying to lose weight | 1.43(1.14-1.80)** | 1.31(1.16-1.46)*** | 1.00(ref) | 5.76(4.75-6.97)*** | 2.13(1.46-3.11)*** |

| Fasted to lose weight | 2.73(2.12-3.51)*** | 1.30(1.10-1.54)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.97(1.69-2.29)*** | 3.39(1.99-5.75)*** |

| Diet pills to lose weight | 3.32(2.43-4.55)*** | 1.11(0.88-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 2.31(1.78-2.99)*** | 4.74(2.65-8.48)*** |

| Vomited to lose weight | 3.35(2.38-4.70)*** | 1.12(0.91-1.38) | 1.00(ref) | 2.61(1.92-3.55)*** | 6.49(3.65-11.57)*** |

| Not eat breakfast | 1.37(1.02-1.85)* | 1.23(1.07-1.41)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.42(1.21-1.67)*** | 1.30(0.76-2.21) |

| Played video/computer game | 1.11(0.88-1.40) | 1.19(1.05-1.34)** | 1.00ref) | 1.55(1.35-1.79)*** | 1.64(1.15-2.36)** |

| Not attend sports teams | 1.37(1.08-1.75)* | 1.21(1.10-1.34)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.45(1.25-1.69)*** | 1.78(1.17-2.73)** |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Note.

ref = referent category

N (weighed %) for greatly underestimated, moderately underestimated, correctly perceived, morderately overestimated, and greatly overestimated weight were 599 (3.96), 3460 (25.14), 8213 (59.30), 1456 (10.57), and 136 (1.03), respectively.

Appendix Table B. Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors According to Misperceived Weight Category, Adjusted for Age and Race/Ethnicity; 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Boys).

| Health Risk Behaviors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Greatly Underestimated Weight |

Moderately Underestimated Weight |

Correctly Perceived Weight |

Moderately Overestimated Weight |

Greatly Overestimated Weight |

|

| Safety & Violence | |||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | 2.48(1.62-3.79)*** | 1.28(0.99-1.65) | 1.00(ref) | 0.79(0.51-1.22) | 4.82(1.99-11.72)*** |

| Drink & drive | 1.41(0.99-2.00) | 1.12(0.86-1.46) | 1.00(ref) | 0.89(0.59-1.34) | 3.38(1.33-8.60)* |

| Carry a weapon at school | 1.57(0.98-2.53) | 1.12(0.89-1.42) | 1.00(ref) | 1.60(1.03-2.47)* | 2.08(0.87-4.96) |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 2.78(1.79-4.32)*** | 0.90(0.65-1.24) | 1.00(ref) | 1.04(0.65-1.67) | 5.39(2.29-12.69)*** |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | 2.19(1.33-3.58)** | 1.15(0.94-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 1.57(0.99-2.47) | 4.68(2.07-10.57)*** |

| Property stolen/damaged | 1.03(0.73-1.45) | 0.97(0.83-1.13) | 1.00(ref) | 1.33(0.98-1.80) | 4.55(2.19-9.46)*** |

| Fight at school | 1.56(1.19-2.05)** | 0.99(0.83-1.18) | 1.00(ref) | 0.88(0.60-1.29) | 2.88(1.49-5.59)** |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 1.33(0.92-1.92) | 0.93(0.78-1.11) | 1.00(ref) | 1.20(0.84-1.73) | 3.77(1.70-8.38)** |

| Physically forced to have sex | 3.00(1.88-4.78)*** | 0.94(0.67-1.32) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.72-2.28) | 7.16(2.89-17.70)*** |

| Not use condom | 1.26(0.80-1.97) | 1.11(0.88-1.40) | 1.00(ref) | 1.15(0.69-1.92) | 1.73(0.61-4.89) |

| Being bullied | 1.83(1.26-2.65)** | 1.04(0.82-1.32) | 1.00(ref) | 2.12(1.63-2.76)*** | 3.18(1.55-6.52)** |

| Mental Health | |||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | 1.60(1.21-2.11)*** | 1.29(1.10-1.51)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.71(1.34-2.18)*** | 2.88(1.40-5.93)** |

| Considered suicide | 1.52(1.06-2.18)* | 1.07(0.85-1.36) | 1.00(ref) | 1.49(1.11-2.00)** | 4.53(2.03-10.10)*** |

| Planned suicide | 1.72(1.18-2.50)** | 1.06(0.84-1.33) | 1.00(ref) | 1.26(0.85-1.88) | 6.73(3.10-14.60)*** |

| Attempted suicide | 1.96(1.24-3.11)** | 0.96(0.73-1.28) | 1.00(ref) | 1.46(0.89-2.40) | 9.56(3.74-24.46)*** |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | 3.47(1.79-6.72)*** | 1.58(0.92-2.71) | 1.00(ref) | 1.51(0.55-4.17) | 18.5(5.40-63.22)*** |

| Substance Use | |||||

| Current cigarette use | 2.22(1.49-3.29)*** | 1.14(0.87-1.47) | 1.00(ref) | 1.21(0.65-2.28) | 3.63(1.09-12.08)* |

| Current alcohol use | 2.15(1.52-3.03)*** | 1.11(0.84-1.46) | 1.00(ref) | 1.07(0.69-1.66) | 6.20(2.43-15.80)*** |

| Current marijuana use | 1.60(1.05-2.44)* | 1.00(0.77-1.30) | 1.00(ref) | 0.88(0.52-1.49) | 5.59(2.67-11.71)*** |

| Current cocaine use | 1.69(1.02-2.79)* | 1.10(0.73-1.65) | 1.00(ref) | 1.07(0.57-1.98) | 10.2(3.62-28.54)*** |

| Lifetime heroin use | 3.18(2.13-4.76)*** | 1.13(0.77-1.67) | 1.00(ref) | 1.48(0.73-3.01) | 9.27(4.70-18.26)*** |

| Lifetime methamphetamines use | 2.92(1.83-4.66)*** | 0.91(0.64-1.30) | 1.00(ref) | 1.66(0.90-3.08) | 8.44(4.94-14.42)*** |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | 1.56(1.02-2.39)* | 1.15(0.86-1.55) | 1.00(ref) | 1.03(0.66-1.60) | 6.26(3.08-12.74)*** |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 1.68(1.14-2.47)** | 1.08(0.83-1.41) | 1.00(ref) | 0.85(0.44-1.67) | 3.01(1.51-6.00)** |

| Lifetime steroid use | 3.87(2.56-5.85)*** | 1.10(0.78-1.53) | 1.00(ref) | 1.58(0.88-2.83) | 13.8(6.68-28.64)*** |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | |||||

| Trying to lose weight | 1.86(1.38-2.52)*** | 1.76(1.49-2.07)*** | 1.00(ref) | 5.76(4.59-7.24)*** | 1.44(0.77-2.70) |

| Fasted to lose weight | 2.91(2.12-3.98)*** | 1.36(1.07-1.74)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.92(1.37-2.70)*** | 7.22(3.40-15.32)*** |

| Diet pills to lose weight | 3.76(2.47-5.70)*** | 1.35(0.94-1.94) | 1.00(ref) | 1.96(1.16-3.30)* | 5.63(2.26-13.99)*** |

| Vomited to lose weight | 5.35(3.54-8.10)*** | 1.54(1.07-2.22)* | 1.00(ref) | 2.75(1.46-5.17)** | 11.2(4.83-25.90)*** |

| Not eat breakfast | 1.41(1.00-2.00) | 1.21(1.02-1.43)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.29(0.96-1.72) | 0.93(0.46-1.86) |

| Played video/computer game | 1.06(0.78-1.45) | 1.20(1.03-1.40)* | 1.00ref) | 1.96(1.49-2.58)*** | 2.79(1.60-4.85)*** |

| Not attend sports teams | 1.15(0.85-1.55) | 1.13(1.00-1.27)* | 1.00(ref) | 2.11(1.55-2.88)*** | 2.03(1.08-3.81)* |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05.

Note.

ref = referent category

Appendix Table C. Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors According to Misperceived Weight Category, Adjusted for Age and Race/Ethnicity; 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Girls).

| Health Risk Behaviors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Greatly Underestimated Weight |

Moderately Underestimated Weight |

Correctly Perceived Weight |

Moderately Overestimated Weight |

Greatly Overestimated Weight |

|

| Safety & Violence | |||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | 2.09(1.13-3.86)* | 1.24(0.96-1.59) | 1.00(ref) | 1.13(0.79-1.62) | 2.19(1.22-3.92)** |

| Drink & drive | 2.39(1.23-4.66)* | 1.01(0.80-1.28) | 1.00(ref) | 1.13(0.88-1.45) | 1.53(0.58-4.08) |

| Carry a weapon at school | 7.00(3.23-15.18)*** | 2.08(1.33-3.25)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.16(0.66-2.03) | 3.17(1.17-8.58)* |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 3.29(1.76-6.16)*** | 1.73(1.27-2.34)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.38(0.99-1.94) | 2.21(1.10-4.44)* |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | 2.23(1.30-3.81)** | 1.26(0.86-1.83) | 1.00(ref) | 1.31(0.90-1.90) | 2.85(1.22-6.62)* |

| Property stolen/damaged | 1.82(1.12-2.96)* | 1.02(0.81-1.28) | 1.00(ref) | 1.09(0.88-1.36) | 1.03(0.58-1.81) |

| Fight at school | 1.61(0.85-3.03) | 1.23(0.90-1.68) | 1.00(ref) | 1.06(0.81-1.39) | 1.32(0.53-3.30) |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 1.79(1.04-3.08)* | 1.07(0.86-1.33) | 1.00(ref) | 1.14(0.87-1.51) | 1.98(0.73-5.40) |

| Physically forced to have sex | 2.32(1.17-4.61)* | 1.19(0.91-1.56) | 1.00(ref) | 1.42(1.04-1.94)* | 0.75(0.29-1.91) |

| Not use condom | 1.96(0.85-4.51) | 1.24(0.92-1.68) | 1.00(ref) | 1.37(1.02-1.83)* | 6.33(2.35-17.06)*** |

| Being bullied | 1.92(1.29-2.87)** | 1.52(1.19-1.93)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.42(1.16-1.72)*** | 1.82(1.04-3.19)* |

| Mental Health | |||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | 1.53(0.93-2.50) | 1.31(1.10-1.57)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.59(1.36-1.86)*** | 2.18(1.22-3.90)** |

| Considered suicide | 2.33(1.41-3.84)*** | 1.50(1.20-1.88)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.64(1.35-2.00)*** | 2.52(1.50-4.24)*** |

| Planned suicide | 2.10(1.22-3.62)** | 1.32(1.05-1.66)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.80(1.47-2.21)*** | 2.98(1.66-5.38)*** |

| Attempted suicide | 1.59(0.93-2.72) | 1.35(1.03-1.79)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.76(1.27-2.44)*** | 2.63(1.36-5.10)** |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | 2.51(0.99-6.37) | 2.08(1.41-3.05)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.94(1.18-3.20)** | 4.50(1.70-11.93)** |

| Substance Use | |||||

| Current cigarette use | 4.10(1.68-10.01)** | 1.25(0.82-1.92) | 1.00(ref) | 1.16(0.71-1.89) | 2.08(0.85-5.04) |

| Current alcohol use | 4.19(2.25-7.82)*** | 1.55(1.18-2.04)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.64(1.16-2.32)** | 2.93(1.22-7.04)* |

| Current marijuana use | 3.24(1.67-6.29)*** | 1.19(0.79-1.79) | 1.00(ref) | 1.04(0.65-1.66) | 2.66(1.07-6.60)* |

| Current cocaine use | 4.37(1.56-12.27)** | 1.75(0.91-3.35) | 1.00(ref) | 1.13(0.59-2.16) | 2.17(0.51-9.21) |

| Lifetime heroin use | 7.20(2.60-19.95)*** | 2.13(1.17-3.89)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.73-2.24) | 2.73(0.72-10.42) |

| Lifetime methamphetamines use | 6.02(2.85-12.70)*** | 1.50(0.93-2.44) | 1.00(ref) | 1.11(0.69-1.78) | 3.40(1.20-9.66)* |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | 3.07(1.38-6.82)** | 1.06(0.71-1.59) | 1.00(ref) | 1.11(0.83-1.48) | 1.94(0.89-4.23) |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 3.20(1.67-6.11)*** | 1.27(0.88-1.83) | 1.00(ref) | 1.59(1.27-1.99)*** | 2.38(1.10-5.17)* |

| Lifetime steroid use | 4.49(1.77-11.37)** | 1.76(1.18-2.62)** | 1.00(ref) | 1.33(0.79-2.25) | 4.57(1.73-12.02)** |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | |||||

| Trying to lose weight | 0.90(0.68-1.19) | 0.88(0.76-1.02) | 1.00(ref) | 5.85(4.44-7.72)*** | 3.09(1.82-5.26)*** |

| Fasted to lose weight | 2.56(1.64-3.99)*** | 1.29(1.00-1.66)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.97(1.65-2.34)*** | 2.22(1.17-4.22)* |

| Diet pills to lose weight | 2.77(1.62-4.75)*** | 0.88(0.59-1.32) | 1.00(ref) | 2.33(1.71-3.18)*** | 4.28(1.86-9.84)*** |

| Vomited to lose weight | 1.76(1.02-3.03)* | 0.97(0.74-1.28) | 1.00(ref) | 2.48(1.76-3.49)*** | 5.30(2.58-10.85)*** |

| Not eat breakfast | 1.21(0.69-2.13) | 1.25(1.01-1.54)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.51(1.25-1.82)*** | 1.67(0.90-3.10) |

| Played video/computer game | 1.30(0.87-1.95) | 1.17(0.97-1.41) | 1.00ref) | 1.39(1.19-1.63)*** | 1.06(0.63-1.79) |

| Not attend sports teams | 2.38(1.59-3.56)*** | 1.33(1.15-1.55)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.26(1.08-1.47)** | 1.61(0.86-3.02) |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Note.

ref = referent category

Appendix Table D. Tests for Interaction of Weight Misperception by Sex, 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Health Risk Behaviors | Weight Misperception × Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| (-II) × Female | (-I) × Female | (I) × Female | (II) × Female | |||||

| Estimation | p value | Estimation | p value | Estimation | p value | Estimation | p value | |

| Safety & Violence | ||||||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | -0.1864 | 0.5264 | -0.0393 | 0.8069 | 0.359 | 0.2295 | -0.7887 | 0.0627 |

| Drink & drive | 0.469 | 0.2449 | -0.1109 | 0.5544 | 0.2492 | 0.2668 | -0.7893 | 0.2067 |

| Carry a weapon at school | 1.4753 | 0.0004 | 0.6146 | 0.0144 | -0.3356 | 0.374 | 0.4154 | 0.5454 |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 0.113 | 0.7361 | 0.6472 | 0.0065 | 0.2914 | 0.3141 | -0.8889 | 0.1014 |

| Threatened or injured with a weapon at school | 0.0441 | 0.9124 | 0.1091 | 0.6063 | -0.1934 | 0.4992 | -0.5301 | 0.3532 |

| Property stolen/damaged | 0.5975 | 0.027 | 0.0619 | 0.6473 | -0.2124 | 0.2222 | -1.5091 | 0.0027 |

| Fight at school | 0.1273 | 0.7152 | 0.2411 | 0.2068 | 0.1687 | 0.4652 | -0.7878 | 0.226 |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 0.261 | 0.3143 | 0.1357 | 0.2848 | -0.0387 | 0.872 | -0.6296 | 0.3104 |

| Physically forced to have sex | -0.3687 | 0.3617 | 0.2116 | 0.342 | 0.122 | 0.7323 | -2.2296 | <.0001 |

| Not use condom | 0.4736 | 0.2568 | 0.1292 | 0.5026 | 0.1566 | 0.5565 | 1.2717 | 0.0721 |

| Being bullied | 0.0347 | 0.8964 | 0.3736 | 0.0434 | -0.4028 | 0.0268 | -0.5599 | 0.2058 |

| Mental Health | ||||||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | -0.0374 | 0.9074 | 0.0313 | 0.798 | -0.0815 | 0.5526 | -0.2939 | 0.4901 |

| Considered suicide | 0.4634 | 0.1017 | 0.3442 | 0.0299 | 0.0833 | 0.6701 | -0.6036 | 0.1684 |

| Planned suicide | 0.2558 | 0.4496 | 0.2319 | 0.1993 | 0.338 | 0.1409 | -0.837 | 0.0705 |

| Attempted suicide | -0.2291 | 0.5339 | 0.333 | 0.0563 | 0.199 | 0.4685 | -1.2758 | 0.0182 |

| Suicide attempt treated by a Dr./nurse | -0.3816 | 0.4956 | 0.2593 | 0.385 | 0.279 | 0.6264 | -1.3702 | 0.047 |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| Current cigarette use | 0.4878 | 0.2644 | 0.0861 | 0.7094 | -0.0415 | 0.9068 | -0.569 | 0.4708 |

| Current alcohol use | 0.6071 | 0.0862 | 0.336 | 0.0504 | 0.4305 | 0.1652 | -0.7564 | 0.2457 |

| Current marijuana use | 0.6339 | 0.1019 | 0.1513 | 0.4489 | 0.1774 | 0.6527 | -0.7271 | 0.2427 |

| Current cocaine use | 0.7935 | 0.1814 | 0.4354 | 0.2227 | 0.079 | 0.871 | -1.5324 | 0.1034 |

| Lifetime heroin use | 0.7952 | 0.1469 | 0.6098 | 0.1149 | -0.1253 | 0.7763 | -1.1911 | 0.1144 |

| Lifetime methamphetamines use | 0.5748 | 0.1894 | 0.4743 | 0.135 | -0.3603 | 0.4032 | -0.8789 | 0.1168 |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | 0.5574 | 0.219 | -0.1094 | 0.6794 | 0.0905 | 0.7388 | -1.1775 | 0.0211 |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 0.5382 | 0.1369 | 0.1318 | 0.5874 | 0.638 | 0.0868 | -0.2243 | 0.6578 |

| Lifetime steroid use | 0.0595 | 0.9131 | 0.4373 | 0.1065 | -0.1563 | 0.6824 | -1.0966 | 0.0569 |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | ||||||||

| Trying to lose weight | -0.7552 | 0.0002 | -0.6942 | <.0001 | 0.0252 | 0.881 | 0.7715 | 0.0413 |

| Fasted to lose weight | -0.1618 | 0.5746 | -0.0498 | 0.7886 | 0.0201 | 0.9146 | -1.1988 | 0.027 |

| Diet pills to lose weight | -0.3535 | 0.3126 | -0.4409 | 0.1542 | 0.1846 | 0.562 | -0.2659 | 0.6943 |

| Vomited to lose weight | -1.2773 | 0.0002 | -0.4845 | 0.0578 | -0.0818 | 0.8217 | -0.7352 | 0.1972 |

| Not eat breakfast | -0.0858 | 0.8039 | 0.0531 | 0.6879 | 0.1396 | 0.4378 | 0.5748 | 0.1625 |

| Played video/computer game | 0.2632 | 0.3304 | -0.0131 | 0.9139 | -0.3533 | 0.0318 | -0.9771 | 0.0187 |

| Not attend sports teams | 0.7923 | 0.0017 | 0.158 | 0.0696 | -0.5343 | 0.0018 | -0.2319 | 0.6415 |

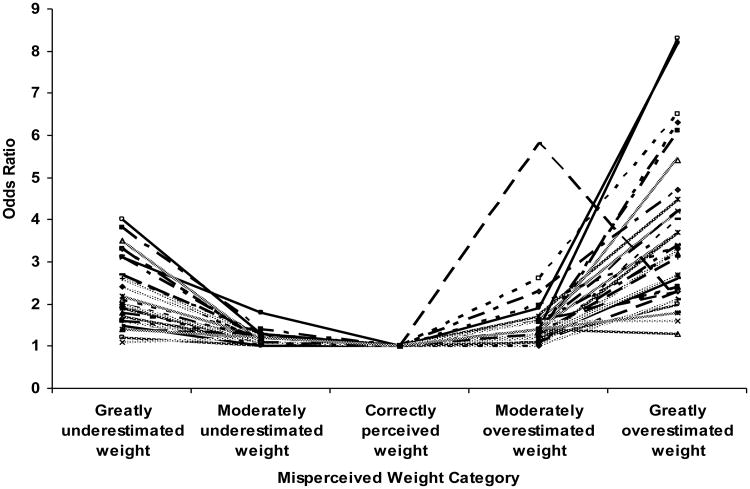

An overview of the dose-response relationship between misperceived weight status and 32 health risk behaviors is shown in Figure 1. Associations between misperceived weight classification and health risk behaviors demonstrated a U-shaped curve among participants, indicating that weight overestimation and underestimation were associated with engaging in health risk behaviors in a dose-response manner.

Figure 1. Odds Ratios Representing Associations of Misperceived Weight Category with Prevalence of 32 Health Risk Behaviors, Adjusted for Age, Sex and Race/Ethnicity; 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Further sensitivity analyses evaluated potential contributions of cognitive abilities as a confounder. Analyses in the 2007- and 2009-combined Rhode Island YRBS that further adjusted for academic performance (Appendix Table E) demonstrated similar associations between weight misperception and health risk behaviors as analyses that did not adjust for academic performance (Appendix Table F).

Appendix Table E. Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors According to Misperceived Weight Category, Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity and Academic Performance; 2007- and 2009-Combined Rhode Island Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Health Risk Behaviors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Greatly Underestimated Weight |

Moderately underestimated Weight |

Correctly Perceived Weight |

Moderately Overestimated Weight |

Greatly Overestimated Weight |

|

| Safety & Violence | |||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | 1.52(1.14-2.03)** | 1.09(0.87-1.36) | 1.00(ref) | 0.91(0.65-1.28) | 1.57(0.69-3.57) |

| Carried a weapon (gun, knife, or club) | 1.34(0.94-1.92) | 1.19(0.96-1.47) | 1.00(ref) | 1.02(0.72-1.45) | 3.07(1.32-7.14)** |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 2.13(1.46-3.11)*** | 1.04(0.66-1.64) | 1.00(ref) | 1.20(0.83-1.74) | 5.73(2.93-11.18)*** |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | 1.56(1.00-2.44)* | 0.82(0.57-1.16) | 1.00(ref) | 1.27(0.86-1.88) | 4.00(1.89-8.48)*** |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 1.92(1.32-2.79)*** | 0.84(0.68-1.05) | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(0.74-1.36) | 2.95(1.77-4.92)*** |

| Physically forced to have sex | 2.46(1.47-4.12)*** | 0.89(0.62-1.26) | 1.00(ref) | 1.27(0.87-1.84) | 2.89(1.54-5.42)*** |

| Mental Health | |||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | 1.76(1.24-2.48)** | 1.17(0.99-1.39) | 1.00(ref) | 1.53(1.21-1.94)*** | 2.91(1.48-5.73)** |

| Considered suicide | 2.09(1.29-3.38)** | 1.16(0.89-1.50) | 1.00(ref) | 1.71(1.27-2.31)*** | 5.60(2.83-11.10)*** |

| Planned suicide | 1.62(1.02-2.57)* | 1.23(0.93-1.61) | 1.00(ref) | 1.55(1.12-2.15)** | 3.24(1.72-6.09)*** |

| Attempted suicide | 4.92(2.93-8.28)*** | 1.24(0.95-1.62) | 1.00(ref) | 1.32(0.90-1.94) | 4.97(2.71-9.13)*** |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | 2.86(1.07-7.63)* | 1.17(0.68-2.00) | 1.00(ref) | 1.22(0.66-2.25) | 8.64(3.29-22.68)*** |

| Substance Use | |||||

| Current cigarette use | 1.54(1.05-2.24)* | 1.00(0.82-1.22) | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(0.67-1.51) | 3.47(1.98-6.07)*** |

| Current alcohol use | 0.94(0.65-1.37) | 1.03(0.87-1.23) | 1.00(ref) | 1.03(0.86-1.23) | 2.08(1.07-4.08)* |

| Current marijuana use | 0.86(0.59-1.26) | 1.01(0.85-1.20) | 1.00(ref) | 1.08(0.85-1.36) | 1.43(0.75-2.72) |

| Current cocaine use | 4.64(2.38-9.06)*** | 0.98(0.54-1.78) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.63-2.60) | 13.3(6.58-26.78)*** |

| Lifetime cocaine use | 2.92(1.73-4.91)*** | 1.13(0.80-1.61) | 1.00(ref) | 1.14(0.69-1.88) | 6.92(3.53-13.56)*** |

| Lifetime inhalant use | 1.84(1.22-2.77)** | 1.09(0.78-1.54) | 1.00(ref) | 0.98(0.67-1.43) | 5.13(2.56-10.30)*** |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 2.76(1.69-4.50)*** | 1.31(0.91-1.89) | 1.00(ref) | 1.27(0.86-1.87) | 4.85(2.84-8.26)*** |

| Lifetime illegal steroid use | 5.97(3.27-10.90)*** | 1.72(1.11-2.67)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.04(0.40-2.70) | 5.26(1.99-13.87)*** |

| Lifetime painkiller use | 1.83(1.32-2.54)*** | 1.20(0.93-1.56) | 1.00(ref) | 1.15(0.86-1.53) | 2.61(1.32-5.20)** |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | |||||

| Trying to lose weight | 2.76(1.98-3.84)*** | 1.31(1.11-1.56)** | 1.00(ref) | 7.43(5.92-9.33)*** | 2.77(1.58-4.84)*** |

| Exercised to lose weight | 1.27(0.87-1.86) | 0.80(0.68-0.93)** | 1.00(ref) | 2.17(1.70-2.77)*** | 1.08(0.54-2.18) |

| Ate less to lose weight | 1.73(1.18-2.53)** | 1.21(1.01-1.45)* | 1.00(ref) | 2.69(2.12-3.41)*** | 3.29(1.76-6.15)*** |

| Fasted to lose weight | 4.47(2.84-7.04)*** | 1.27(0.97-1.66) | 1.00(ref) | 2.28(1.73-3.01)*** | 13.4(7.03-25.59)*** |

| Vomited to lose weight | 10.4(6.71-16.17)*** | 1.19(0.89-1.60) | 1.00(ref) | 2.57(1.73-3.82)*** | 15.8(9.11-27.38)*** |

| Not drink 100% fruit juices | 2.71(2.03-3.64)*** | 1.16(0.99-1.37) | 1.00(ref) | 1.10(0.82-1.46) | 3.17(1.60-6.29)*** |

| Not eat fruit | 2.92(2.27-3.75)*** | 1.19(0.96-1.47) | 1.00(ref) | 1.01(0.74-1.38) | 3.47(1.86-6.47)*** |

| Insufficient physical activity | 2.60(1.72-3.93)*** | 1.37(1.16-1.61)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.41(1.13-1.75)** | 1.37(0.59-3.19) |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Note.

ref = referent category

Appendix Table F. Odds Ratios of Health Risk Behaviors According to Misperceived Weight Category, Adjusted for Age, Sex and Race/ethnicity; 2007- and 2009-Combined Rhode Island Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

| Health Risk Behaviors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Greatly Underestimated Weight |

Moderately Underestimated Weight |

Correctly Perceived Weight |

Moderately Overestimated Weight |

Greatly Overestimated Weight |

|

| Safety & Violence | |||||

| Rarely/never wore seatbelt | 1.61(1.23-2.10)*** | 1.14(0.92-1.40) | 1.00(ref) | 0.94(0.66-1.33) | 1.69(0.69-4.11) |

| Carried a weapon (gun, knife, or club) | 1.44(1.00-2.08)* | 1.24(1.01-1.53)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.02(0.72-1.44) | 3.25(1.44-7.33)** |

| Not go to school due to feeling unsafe | 2.12(1.46-3.10)*** | 1.12(0.72-1.73) | 1.00(ref) | 1.19(0.82-1.74) | 6.13(3.14-11.98)*** |

| Threatened or injured with weapon at school | 1.63(1.03-2.58)* | 0.87(0.62-1.22) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.86-1.90) | 4.44(1.98-9.94)*** |

| Hit by boyfriend/girlfriend on purpose | 2.01(1.37-2.94)*** | 0.89(0.72-1.11) | 1.00(ref) | 1.02(0.75-1.39) | 3.10(1.88-5.12)*** |

| Physically forced to have sex | 2.50(1.51-4.14)*** | 0.94(0.67-1.33) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.88-1.86) | 3.11(1.61-6.03)*** |

| Mental Health | |||||

| Felt sad/hopeless | 1.79(1.26-2.54)** | 1.20(1.02-1.41)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.53(1.21-1.93)*** | 3.08(1.55-6.14)** |

| Considered suicide | 2.14(1.31-3.48)** | 1.19(0.92-1.53) | 1.00(ref) | 1.73(1.29-2.32)*** | 5.77(3.00-11.07)*** |

| Planned suicide | 1.64(1.01-2.66)* | 1.26(0.96-1.64) | 1.00(ref) | 1.54(1.11-2.14)* | 3.36(1.90-5.93)*** |

| Attempted suicide | 4.97(2.93-8.45)*** | 1.26(0.96-1.64) | 1.00(ref) | 1.30(0.89-1.90) | 5.06(2.70-9.45)*** |

| Suicide attempt treated by doctor/nurse | 2.82(1.07-7.41)* | 1.19(0.69-2.04) | 1.00(ref) | 1.21(0.67-2.21) | 8.49(3.24-22.22)*** |

| Substance Use | |||||

| Current cigarette use | 1.67(1.13-2.46)** | 1.05(0.87-1.27) | 1.00(ref) | 1.03(0.71-1.50) | 3.59(2.02-6.39)*** |

| Current alcohol use | 0.99(0.68-1.44) | 1.06(0.91-1.25) | 1.00(ref) | 1.03(0.87-1.22) | 2.11(1.06-4.21)* |

| Current marijuana use | 0.91(0.64-1.30) | 1.05(0.89-1.25) | 1.00(ref) | 1.08(0.86-1.37) | 1.57(0.84-2.94) |

| Current cocaine use | 4.91(2.48-9.73)*** | 1.12(0.66-1.89) | 1.00(ref) | 1.28(0.63-2.63) | 15.3(7.53-30.96)*** |

| Lifetime cocaine use | 3.08(1.79-5.30)*** | 1.21(0.88-1.67) | 1.00(ref) | 1.14(0.69-1.90) | 7.55(3.87-14.72)*** |

| Lifetime inhalant use | 1.91(1.28-2.84)** | 1.13(0.80-1.59) | 1.00(ref) | 0.99(0.67-1.45) | 5.65(2.82-11.32)*** |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | 2.78(1.73-4.47)*** | 1.38(0.99-1.93) | 1.00(ref) | 1.27(0.86-1.87) | 5.50(3.09-9.80)*** |

| Lifetime illegal steroid use | 6.14(3.29-11.45)*** | 1.80(1.14-2.83)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.04(0.40-2.75) | 6.29(2.47-16.01)*** |

| Lifetime painkiller use | 1.86(1.33-2.59)*** | 1.24(0.96-1.61) | 1.00(ref) | 1.14(0.86-1.51) | 2.84(1.42-5.68)** |

| Dieting & Physical Inactivity | |||||

| Trying to lose weight | 2.75(1.98-3.84)*** | 1.33(1.12-1.57)** | 1.00(ref) | 7.46(5.94-9.36)*** | 2.73(1.62-4.61)*** |

| Exercised to lose weight | 1.26(0.86-1.85) | 0.80(0.68-0.94)** | 1.00(ref) | 2.18(1.71-2.78)*** | 1.06(0.52-2.15) |

| Ate less to lose weight | 1.72(1.19-2.49)** | 1.22(1.02-1.46)* | 1.00(ref) | 2.70(2.12-3.43)*** | 3.31(1.77-6.19)*** |

| Fasted to lose weight | 4.54(2.91-7.08)*** | 1.31(1.01-1.69)* | 1.00(ref) | 2.29(1.72-3.05)*** | 13.9(7.39-25.98)*** |

| Vomited to lose weight | 10.6(7.01-16.04)*** | 1.27(0.96-1.68) | 1.00(ref) | 2.58(1.74-3.83)*** | 16.5(9.45-28.95)*** |

| Not drink 100% fruit juices | 2.73(2.03-3.67)*** | 1.18(1.00-1.39)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.12(0.84-1.48) | 3.19(1.64-6.20)*** |

| Not eat fruit | 2.92(2.30-3.71)*** | 1.18(0.96-1.45) | 1.00(ref) | 1.01(0.74-1.39) | 3.49(1.89-6.42)*** |

| Insuffcient physical activity | 2.66(1.74-4.06)*** | 1.39(1.19-1.63)*** | 1.00(ref) | 1.40(1.13-1.74)** | 1.43(0.62-3.31) |

| Academic Performances | |||||

| Mostly D's or F's | 1.60(0.93-2.75) | 1.38(1.00-1.90)* | 1.00(ref) | 1.10(0.70-1.73) | 2.37(0.93-6.04) |

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Note.

ref = referent category

Discussion

Perceived weight status in a nationally representative sample of high school students was not concordant with reported actual weight for 40.7% of participants. Misperceived weight was significantly associated with all 32 of the evaluated health risk behaviors in the 4 domains including safety/violence, mental health, substance use, and dieting/physical inactivity. Participants with underestimated or overestimated weight were more likely to engage in health risk behaviors in a dose-response manner, compared to those with correctly perceived weight.

Prior Literature

Previous studies demonstrated that inaccurate weight perception in adolescents is typically positively associated with depressive symptoms, suicidal behavior, alcohol consumption, soft drink consumption, time spent watching television, and negatively associated with vegetable intake, trying to lose weight, and physical activity, compared to those who correctly percieved their weight.1-3,5,6,8,10,11,14,36-38 Other studies found adolescents with overestimated weight were more likely to engage in weight-related health risk behaviors (taking diet pills, fasting, or using laxatives/vomited to lose their weight, eating fewer calories, watching TV), and those students with underestimated weight were less likely to exercise or eat fewer calories.34,39 Our results showed that those high school students who misperceived their weight were more likely to engage in all health risk behaviors compared to those who correctly perceived their weight. Those who greatly overestimated their weight have higher odds ratios for all health risk behaviors than those who greatly underestimated their weight except ‘physically forced to have sex’ and ‘not eat breakfast’. These findings are consistent with the present results. The current analyses further evaluated novel outcomes such as seatbelt use, drinking and driving, carrying weapons, feeling unsafe at school, dating violence, and forced sex, and found signficant dose-response associations of misperceived weight with these factors. Furthermore, most studies to date use study samples with limited generalizability; there is a need for nationally representative study populations, which the current study provides.5,7,8,10,13-18

Additionally, prior studies have tended to dichotomize participants as accurate vs innaccurate perceivers,14 or categorized participants in 3 levels as those who underestimated, correctly estimated, or overestimated weight.16-18 The larger number of weight misperception categories in the current study allowed for dose-response associations to be demonstrated. Finally, weight overestimation is less common, and less often considered a public health concern. This study demonstrated that adolescents who either underestimated or overestimated weight had greater health risk behaviors, suggesting that both underestimation and overesimation of weight may be important.

Strengths and Limitations

With regard to strengths, this study evaluated associations of weight misperception with a large number of health risk behaviors, in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Among the 4 domains of health risk behaviors evaluated, particularly novel findings were demonstrated for associations of weight misperception with seatbelt use, drinking and driving, carrying weapons, feeling unsafe at school, not using condoms, dating violence, and forced sex. Furthermore, by using 5 categories of weight misperception, this study was able to evaluate, and demonstrate, dose-response relations between weight misperception and health risk behaviors.

There were several limitations to this study. First, although BMI percentiles calculated from self-reported height and weight tend to be relatively accurate,7,26-31 evidence suggests that adolescents tend to overestimate their height and underestimate weight.26 Future studies using directly assessed weight and height will provide further evidence on the relation between weight misperception and health risk behaviors. Secondly, the findings do not reflect adolescents who dropped out of school, as the study only assessed participants who were high school students in the US. Third, the YRBS is a cross-sectional study, consequently we cannot infer causation between misperceived weight and health risk behaviors. Future longitudinal research and randomized controlled trials would will provide further evidence on whether misperceived weight status influences adolescents' engagement in health risk behaviors. Fourth, the majority of the health risk behaviors were ‘negative’ or unhealthy in nature except for ‘trying to lose weight’. This could be a positive health behavior for some participants but not others.

Potential Implications

In Western culture, overweight or underweight are often stigmatizing characteristics.9 Peer weight norm misperceptions may help perpetuate adolescents' weight overestimation or underestimation, and contribute to unhealthy behaviors.7,40 Incorrect weight comments have been shown to be related to weight misperception, which can then result in lower self-esteem and poorer body image.41 A study by Ali et al27 demonstrated that participants tended to report perceived weight more inaccurately than their reported actual height and weight. Adolescents may misperceive their weight because they are not aware of clinical descriptions of weight status or because of environmental influences and messages from the media that may not promote healthy body types.12,42 Understanding these influences is necessary to improve interventions that encourage healthy weight perception and attainment, such as potentially incorporating cognitive-behavioral skills into health education curricula, nutrition and physical activity programs. Studies have demonstrated that when adolescents are exposed to actual norms, their misperceptions and actual problem behavior can be reduced.40 There is evidence that prevention intervention programs may be more effective by addressing healthy body image and body size.8 Incorporating misperception awareness to interventions may help adolescents to be more receptive to adopting healthy lifestyle behaviors.12

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated that misperceived weight was significantly associated with 32 health risk behaviors in a dose-response manner, using a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Understanding the potential impact of weight misperception on health risk behaviors could improve interventions that encourage healthy weight perception and attainment for adolescents.

Acknowledgments

No funding was obtained to conduct the study. The authors want to thank all the participants for willingness to participate in this survey. The authors also appreciate the YRBS team for making the data available. The authors have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement: The YRBS study protocol was approved by the CDC Institutional Review Board (IRB). Because the current study performed secondary data analyses without personal identifiers, IRB approval was not required.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists as defined by the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Contributor Information

Yongwen Jiang, Senior Public Health Epidemiologist, Center for Health Data and Analysis, Rhode Island Department of Health, Providence, RI.

Marga Kempner, Research Assistant and Eric B Loucks, Brown University School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, Providence, RI.

Eric B. Loucks, Assistant Professor, Brown University School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, Providence, RI.

References

- 1.Edwards NM, Pettingell S, Borowsky IW. Where perception meets reality: self-perception of weight in overweight adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):e452–458. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang L, Tao FB, Wan YH, et al. Self-reported weight status rather than BMI may be closely related to psychopathological symptoms among Mainland Chinese adolescents. J Trop Pediatr. 2011;57(4):307–311. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurth BM, Ellert U. Perceived or true obesity: which causes more suffering in adolescents?: findings of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS) Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(23):406–412. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman-Hoffman V. High prevalence of abnormal eating and weight control practices among U.S. high-school students. Eat Behav. 2004;5(4):325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang J, Yu Y, Du Y, et al. Association between actual weight status, perceived weight and depressive, anxious symptoms in Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:594. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swahn MH, Reynolds MR, Tice M, et al. Perceived overweight, BMI, and risk for suicide attempts: findings from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3):292–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ursoniu S, Putnoky S, Vlaicu B. Body weight perception among high school students and its influence on weight management behaviors in normal weight students: a cross-sectional study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2011;123(11-12):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-1578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiefelbein EL, Mirchandani GG, George GC, et al. Association between depressed mood and perceived weight in middle and high school age students: Texas 2004-2005. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie B, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D, et al. Longitudinal analysis of weight perception and psychological factors in Chinese adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(1):92–104. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jauregui-Lobera I, Bolanos-Rios P, Santiago-Fernandez MJ, et al. Perception of weight and psychological variables in a sample of Spanish adolescents. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:245–251. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park E. Overestimation and underestimation: adolescents' weight perception in comparison to BMI-based weight status and how it varies across socio-demographic factors. J Sch Health. 2011;81(2):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maximova K, McGrath JJ, Barnett T, et al. Do you see what I see? Weight status misperception and exposure to obesity among children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(6):1008–1015. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao M, Zhang M, Zhou X, et al. Weight misperception and its barriers to keep health weight in Chinese children. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(12):e550–556. doi: 10.1111/apa.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khambalia A, Hardy LL, Bauman A. Accuracy of weight perception, life-style behaviours and psychological distress among overweight and obese adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(3):220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo WS, Ho SY, Mak KK, et al. Weight misperception and psychosocial health in normal weight Chinese adolescents. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2-2):e381–389. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.514342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Liang H, Chen X. Measured body mass index, body weight perception, dissatisfaction and control practices in urban, low-income African American adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott RA, Lee AJ, Stubbs CO, Davies PS. Accuracy of weight status perception in contemporary Australian children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(6):343–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade FC, Raffaelli M, Teran-Garcia M, et al. Weight status misperception among Mexican young adults. Body Image. 2012;9(1):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Edpiemiology. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell TM, de Lemos JA, Banks K, et al. Body size misperception: a novel determinant in the obesity epidemic. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1695–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System--2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11(246):1–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About BMI for children and teens. [Accessed April 10, 2014]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html/

- 25.Blubberbusters. Height, Weight, and body mass index (BMI) percentile calculator for ages 2 to 20 yrs. [Accessed April 10, 2014]; Available at: http://www.blubberbuster.com/height_weight.html.

- 26.Brener ND, McManus T, Galuska DA, et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported height and weight among high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(4):281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali MM, Minor T, Amialchuk A. Estimating the biases associated with self-perceived, self-reported, and measured BMI on mental health. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elgar FJ, Roberts C, Tudor-Smith C, Moore L. Validity of self-reported height and weight and predictors of bias in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(5):371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss RS. Comparison of measured and self-reported weight and height in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(8):904–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Himes JH, Hannan P, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Factors associated with errors in self-reports of stature, weight, and body mass index in Minnesota adolescents. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(4):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm/. Accessed April 10, 2014.

- 33.Duncan JS, Duncan EK, Schofield G. Associations between weight perceptions, weight control and body fatness in a multiethnic sample of adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(1):93–100. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim H, Wang Y. Body weight misperception patterns and their association with health-related factors among adolescents in South Korea. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(12):2596–2603. doi: 10.1002/oby.20361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigby AS. Statistical methods in epidemiology. v. Towards an understanding of the kappa coefficient. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22(8):339–344. doi: 10.1080/096382800296575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin MA, May AL, Frisco ML. Equal weights but different weight perceptions among US adolescents. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):493–504. doi: 10.1177/1359105309355334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Haver J, Szalacha LA, Kelly S, et al. The relationships among body size, biological sex, ethnicity, and healthy lifestyles in adolescents. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011;16(3):199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Seo DC, Kolbe L, et al. Comparison of overweight, weight perception, and weight-related practices among high school students in three large Chinese cities and two large U.S. cities. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(4):366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin BC, Dalton WT, III, Williams SL, et al. Weight status misperception as related to selected health risk behaviors among middle school students. J School Health. 2014;84(2):116–123. doi: 10.1111/josh.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins JM, Perkins HW, Craig DW. Peer weight norm misperception as a risk factor for being over and underweight among UK secondary school students. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(9):965–971. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo WS, Ho SY, Mak KK, et al. Adolescents' experience of comments about their weight - prevalence, accuracy and effects on weight misperception. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:271. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foti K, Lowry R. Trends in perceived overweight status among overweight and nonoverweight adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):636–642. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]