Abstract

Background and Purpose

Statins have pleiotropic effects of potential neuroprotection. However, because of lack of large randomized clinical trials, current guidelines do not provide specific recommendations on statin initiation in acute ischemic stroke (AIS). The current study aims to systematically review the statin effect in AIS.

Methods

From literature review, we identified articles exploring prestroke and immediate post-stroke statin effect on imaging surrogate markers, initial stroke severity, functional outcome, and short-term mortality in human AIS. We summarized descriptive overview. In addition, for subjects with available data from publications, we conducted meta-analysis to provide pooled estimates.

Results

In total, we identified 70 relevant articles including 6 meta-analyses. Surrogate imaging marker studies suggested that statin might enhance collaterals and reperfusion. Our updated meta-analysis indicated that prestroke statin use was associated with milder initial stroke severity (odds ratio [OR] [95% confidence interval], 1.24 [1.05-1.48]; P=0.013), good functional outcome (1.50 [1.29-1.75]; P<0.001), and lower mortality (0.42 [0.21-0.82]; P=0.0108). In-hospital statin use was associated with good functional outcome (1.31 [1.12-1.53]; P=0.001), and lower mortality (0.41 [0.29-0.58]; P<0.001). In contrast, statin withdrawal was associated with poor functional outcome (1.83 [1.01-3.30]; P=0.045). In patients treated with thrombolysis, statin was associated with good functional outcome (1.44 [1.10-1.89]; P=0.001), despite an increased risk of symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation (1.63 [1.04-2.56]; P=0.035).

Conclusions

The current study findings support the use of statin in AIS. However, the findings were mostly driven by observational studies at risk of bias, and thereby large randomized clinical trials would provide confirmatory evidence.

Keywords: Statins, Acute ischemic stroke, Stroke severity, Outcome, Mortality, Symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation

Introduction

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that statins are effective for primary and secondary stroke prevention, and the benefit of statins might be largely driven by lipid-lowering effect. Beyond lipid-lowering effect, experimental studies have shown that statins have pleiotropic effects of anti-inflammatory action, antioxidant effect, antithrombotic action and facilitation of clot lysis, endothelial nitric oxide synthetase upregulation, plaque stabilization, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation reduction, and angiogenesis [1-8]. These pleiotropic effects potentially benefit in acute ischemia of the brain and heart. In addition, animal experiments have shown angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis in acute cerebral ischemia [9]. Thereby, statins are potentially neurorestorative as well as neuroprotective in acute cerebral ischemia.

In patients with acute coronary syndrome acute coronary syndrome or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, large observational studies, RCTs, and meta-analyses showed that statins improved the outcome [10-17]. Reflecting these evidences, the current cardiology guidelines recommend that 1) for patients with acute coronary syndrome, high-intensity statin therapy should be initiated or continued in all patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction and no contraindications (Class I; Level of Evidence B) [18], 2) statins, in the absence of contraindications, regardless of baseline LDL-C and diet modification, should be given to post-unstable angina/non-ST elevation myocardial infarction patients, including postrevascularization patients. (Class I; Level of Evidence A) [19], and 3) for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, administration of a high-dose statin is reasonable before percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce the risk of periprocedural MI (Class IIa; Level of Evidence A for statin naïve patients and LOE B for those on chronic statin therapy) [20].

Despite the anticipated benefit of statins in acute ischemic stroke (AIS), no large randomized trial has been conducted as in acute coronary syndrome. The current systematic review aims to systematically review the statin effect in AIS.

Methods

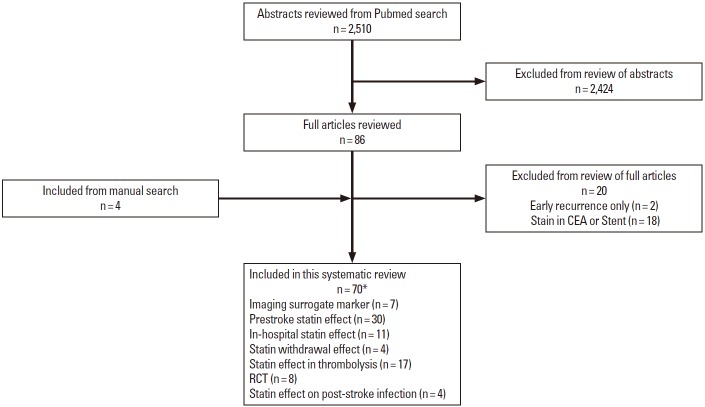

Using search terms of acute stroke and statin, 2,510 abstracts published until 31 December 2014 (including Epub ahead of print) were identified from PubMed search and reviewed by one author (Hong KS.). Then, we selected articles of human beings and AIS written in English. Manual review of references in articles identified 4 additional articles. As a results, the current systematic review included 70 articles: 30 articles of prestroke statin effect, 11 of in-hospital statin effect, 4 of statin withdrawal effect, 17 of statin effect in patients treated with thrombolysis, 8 of RCTs, 4 of prestroke statin effect on poststroke infection, and 7 studies with imaging surrogate markers (11 articles overlapped) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of study selection. *11 articles were overlapped. CEA, carotid endarterectomy; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

For a descriptive overview, we tabulated articles according to each subject. If plausible, we conducted meta-analysis to estimate a pooled effect of statin effect in AIS. For this meta-analysis, only the original publications (excluding meta-analysis articles), which provided relevant odds ratio (OR) or hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), were included. We did not contact authors of studies to request incomplete or unpublished data. To generate a pooled-estimate using a random-effect model, we used multivariable adjusted ORs or HRs and 95% CIs. However, if adjusted ORs were not provided, unadjusted ORs were used in limited cases (1 study for prestroke statin effect on functional outcome, 2 studies for prestroke statin effect on mortality, 2 studies for prestroke statin effect on initial stroke severity, 1 study for prestroke statin effect on mortality in patients with thrombolysis, and 1 study for statin effect on post-stroke infection).

We explored for sources of inconsistency (I2) and heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed by the P value of χ2 statistics and by the I2 statistics. Heterogeneity was considered significant if the P value of χ2 statistics was <0.10. For I2 statistics, we regarded I2 of <40% as minimal, 40%-75% as modest, and >75% as substantial [21]. Publication bias was assessed graphically with a funnel plot and statistically with the Begg’s test when 5 or more studies were available.

Results

Imaging surrogate marker studies

We identified 7 studies of prestroke statin effect on imaging surrogate markers in AIS: collaterals on conventional or CT angiography in 4, infarction volume on diffusion-weighted image (DWI) in 2, and reperfusion on perfusion MRI in 1 study (Table 1) [22-28]. Among the 4 studies assessing collaterals in patients with acute large artery occlusion within 8 to 12 hours [23,26-28], 1 CT-based study showed that prestroke statin was associated with less collaterals [27]. However, on the contrary, 3 conventional angiography-based studies showed that prestroke statin use was associated with more collaterals [23,26,28]. Statin might enhance collaterals by inducing endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and angiogenesis as shown in human coronary arteries [1,2,4,29].

Table 1.

Studies of pre-stroke statin effect on surrogate markers in acute ischemic stroke

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Age | Women (%) | Stroke type | Prestroke statin use (%) | Surrogates | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shook et al.[22] | 2006 | 143 | USA | Single | 66 | 48 | MCA infarction < 48 hr | 26.6 | DWI infarct volume | Smaller infarct volume: adjuste P = 0.033 |

| Ovbiagele et al. [23] | 2007 | 96 | USA | Single | 66 | 48 | Acute LAO < 8 hr | 19.8 | Collaterals, angiography-based | Higher collateral scores: adjusted P = 0.003 |

| Nicholas et al. [24] | 2008 | 285 | USA | Single | NR | 51 | AIS | 36.8 | DWI infarct volume | infarct volume less than median, non-significant among all patients, but higher with statin users among diabetes |

| Ford et al. [25] | 2011 | 31 | USA | Single | 61 | 45 | AIS < 4.5 hr (74%, IV-TPA treated) | 37.8 | Reperfusion on MRI | Greater reperfusion: adjusted P = 0.021 |

| Sargento-Freitas et al. [26] | 2012 | 118 | Portugal | Single | 70 | 45 | Acute LAO with IA therapy | 38.3 | Collaterals, angiography-based | More good collaterals: adjusted OR, 6.0 (1.34-26.81) |

| Malik et al. [27] | 2014 | 82 | Switzerland, USA | Multicenter | 41 | 60 | M1 occlusion < 12 hr | 28.0 | Collaterals, CT-based | Less collaterals: adjusted P = 0.001 |

| Lee et al. [28] | 2014 | 98 | South Korea, USA | Multicenter | 71 | 62 | M1 occlusion < 12 hr+AF | 22.4 | Collaterals, angiography-based | More excellent collaterals: adjusted OR, 7.84 (1.96-31.36) |

Prestroke statin effect on infarction volume was inconsistent across the 2 studies. In 1 study undergoing DWI evaluation within 48 hour (median time, 24 hours) of onset in patients with non-lacunar middle cerebral artery territory infarct, the prestroke statin group versus the no statin group had a significantly smaller infarct volume (median volume, 25.4 cm3 vs. 15.5 cm3, P=0.033 after adjusting covariates) [22]. In another study, prestroke statin was not associated with infarction volume [24]. However, the latter study had major limitations in that about 45% of patients had lacunar infarction and less than 40% performed DWI within 24 hours [24].

In 1 small study (n = 31) which performed serial perfusion MRIs within 4.5 hours and at 6 hours after stroke onset, prestroke statin use was associated with 2- to 3-fold greater early reperfusion in all patients as well as subgroup of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV-TPA) treated patients (74%) [25]. Statin effect of enhancing collaterals, antithrombotic effect, and facilitating fibrinolysis might lead to better early reperfusion in acute cerebral ischemia [1,3,5].

Prestroke statin effect in acute ischemic stroke

We identified 30 articles (28 original articles, 3 meta-analyses, and 1 article providing both original data and meta-analysis findings) evaluating prestroke statin effect on initial stroke severity, functional outcome or short-term mortality (Table 2) [30-59].

Table 2.

Studies of prestroke statin effect in acute ischemic stroke

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Age | Women (%) | Prestroke statin (%) | Effect on hitial stroke severity | Time point | Effect on functional outcome | Effect on mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jonsson et al. [30] | 2001 | 375 | Sweden | Population-based | 66 | 26 | 33.3 | NR | 7 days | Non-significant, discharge to home OR, 1.42 (0.90-2.22) | NR |

| Martí-Fàbregas et al. [31] | 2004 | 167 | Spain | Multicenter | 71 | 44 | 18.0 | Non-significant, median NIHSS P=0.76 (unadjusted) | 90 days | Significant, BI 95-100 OR, 5.55 (1.42-17.8) | NR |

| Greisenegger et al. [32] | 2004 | 1,691 | Austria | Population-based | 71 | 47 | 9.0 | NR | 7 days | Significant, mRS 0-4 OR, 2.27 (1.09-4.76) | NR |

| Yoon et al. [33] | 2004 | 433 | USA | Single | 75 | 52 | 21.9 | NR | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 2.9 (1.2-6.7) | NR |

| Elkind et al. [34] | 2005 | 650 | USA | Population-based | 70 | 55 | 8.8 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS <15 OR, 1.67(0.70-4.00) | 90 days | NR | Significant reduction Unadjusted OR, 0.13 (0.02-0.94) |

| Moonis et al. [35] | 2005 | 852 | International | RCT, post-hoc | 68 | 48 | 15.1 | Non-significant, mean NIHSS NR, unadjusted | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.03 (0.54-1.27) | NR |

| Aslanyan et al. [36] | 2005 | 615 | Scotland | Single | 68 | 52 | 33.3 | Non-significant, mean NIHSS P= 0.8 (unadjusted) | 30 days | NR | Significant reduction OR, 0.24 (0.09-0.67) |

| Bushnell et al. [37] | 2006 | 217 | International | RCTs, post-hoc | NR | 33 | 29.0 | Non-significant, CNS score unadjusted P=0.13 | 28 days | NR | Non-significant Unadjusted P=0.84 |

| Chitravas et al. [38] | 2007 | 716 | Austria | Population-based | 75 | 53 | 7.0 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS <8 unadjusted OR, 0.69 (0.67-3.13); adjusted OR, NS | 28 days | NR | Non-significant Unadjusted OR, 1.21 (0.53-2.78); adjusted OR, NS |

| Reeves et al. [39] | 2008 | 1,360 | USA | Multicenter | NR | 52 | 22.7 | NR | Discharge | Non-significant, mRS 0-3 OR, 1.35 (0.98-1.89) | NR |

| Goldstein et al. [40] | 2009 | 412 | International | RCT, post-hoc | 65 | 34 | 43.7 | NR | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS distribution P= 0.0647 | NR |

| Yu et al. [41] | 2009 | 339 | Canada | Single | 73 | 48 | 21.8 | Non-significant, proportion of CNS >7 OR, 1.29 (0.70-2.38) | 10 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 2.00 (1.00-4.00) | NR |

| Martínez-Sánchez et al. [42] | 2009 | 2,742 | Spain | Single | 69 | 44 | 10.2 | Significant, Canadian Stroke Scale mean 7.39 vs. 7.16, P= 0.045 | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 2.08 (1.39-3.10) for all, 2.79(1.33-5.84) for LAA, 2.28 (1.15-4.52) for SVO | NR |

| Cuadrado-Godia et al. [43] | 2009 | 591 | Spain | Single | 73 | 46 | 23.0 | NR | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 2.56 (0.95-6.67) | NR |

| Stead et al. [44] | 2009 | 207 | USA | Single | 72 | 40 | 48.3 | Non-significant, median NIHSS P=0.183 | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-2 Adjusted OR, 1.91 (1.05-3.47) (adjusted P<0.0001) | NR |

| Arboix et al. [45] | 2010 | 2,082 | Spain | Single | 75 | 53 | 18.3 | NR | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.32 (1.01-1.73) | Significant reduction OR, 0.57 (0.36-0.89) |

| Sacco et al. [46] | 2011 | 2,529 | Italy | Multicenter | 71 | 43 | 9.1 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS <8 OR, 1.10 (0.80-1.57) | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.57 (1.09-2.26) | NR |

| Ní Chróinín et al. [47] | 2011 | 445 | Ireland | Population-based | 71 | 49 | 30.1 | Non-significant, median NIHSS 5 vs. 5 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 2.21 (1.00-4.90) | Significant reduction OR, 0.23 (0.09-0.58) |

| Tsai[48] | 2011 | 172 | Taiwan | Single | 65 | 37 | 25 | Significant, Lower MIHSS, but unadjusted | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 4.82 (1.22-19.03) | NR |

| Biffi et al. [49] | 2011 | 893 | USA | Single | 66 | 40 | 14.1 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS >8 P=0.39 (unadjusted) | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.51 (0.94-2.44) | NR |

| Hassan et al. [50] | 2011 | 386 | Malaysia | Single | 64 | 38 | 29.3 | NR | Discharge | NR | Significant reduction Unadjusted P= 0.013 |

| Flint et al. [51],[52] | 2012 | 12,689 | USA | Multicenter | 75 | 53 | 29.5 | NR | Discharge or 1 year | Significant, discharge to home OR 1.21 (1.11-1.32) at discharge | Significant reduction at 1 year HR, 0.85 (0.79-0.93) |

| Hjalmarsson et al. [53] | 2012 | 799 | Sweden | Single | 78 | 52 | 22.9 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS <8 OR, 1.32 (0.80-2.17) | 30 days | NR | Non-significant HR, 0.56 (0.23-1.33) |

| Aboa-Eboulé et al. [54] | 2013 | 953 | France | Multicenter | 75 | 56 | 13.3 | Non-significant, median NIHSS 4 vs.4 | Discharge | Non-significant, mRS distribution OR 0.76 (0.53-1.09) | NR |

| Phipps et al. [55] | 2013 | 804 | USA | Single | 86 | 64 | 41.5 | Non-significant, proportion of NIHSS <8 OR 1.08 (0.71-1.66) | Discharge | Non-significant, in-hospital mortality/hospice OR, 1.08 (0.60-1.94) | NR |

| Martínez-Sánchez et al.[56] | 2013 | 969 | Spain | Single | 69 | 38 | 27.1 | Significant, NIHSS <6 OR, 1.249 (0.915-1.703) for low-to moderate-dose statin, 2.501 (1.173-5.332) for high-dose statin | Discharge | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, not provided | Non-significant OR, not provided |

| Moonis et al. [57] | 2014 | 1,618 | USA | Multicenter | 67 | 52 | 14.3 | NR | Discharge | Significant, discharge to home OR, 1.67 (CI, 1.12-2.49) | NR |

| Cordenier et al. [58] | 2011 | 1,179/9,337* | Meta-analysis, 11 studies | NR | NR | 16.3 | NR | Discharge or 90 days | Non-significant mRS 0-2 outcome OR, 1.01 (0.64-1.61) at 90 days | Significant redcution at discharge OR, 0.56 (0.40-0.78) | |

| Biffi et al. [49] | 2011 | 11,695 | Meta-analysis, 12 studies | NR | NR | 17.2 | NR | discharge to 90 days | Significant, favorable outcome OR, 1.62 (1.39-1.88) for all, 2.01 (1.14-3.54) for LAA, 2.11 (1.32-3.39) for SVO | NR | |

| Ní Chróinín et al. [59] | 2013 | 17,606/101,615* | Meta-analysis, 27 studies | 64-76 | 33-61 | 4-48 | NR | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.41 (1.29-1.55) | Significant reduction OR, 0.71 (0.62-0.82) |

Provided ORs (95% CIs) are adjusted ORs otherwise indicated, and ORs from meta-analyses are pooled ORs.

Numerator for mRS outcome sample size and denominator for mortality outcome sample size.

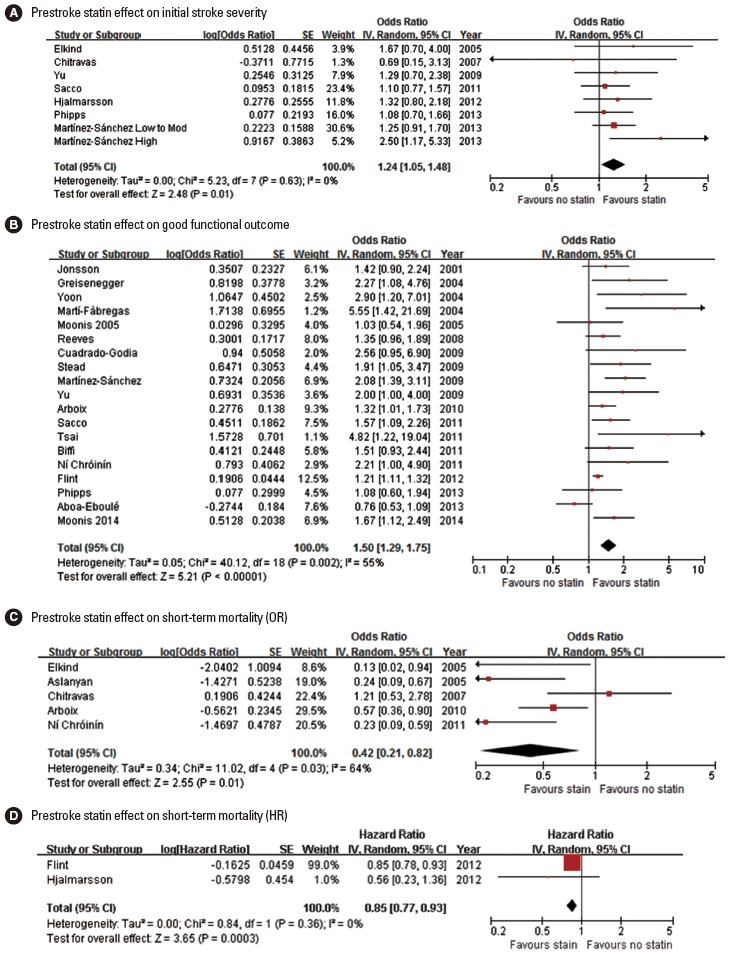

Prestroke statin effect on initial stroke severity

Seventeen original articles were identified and summarized in Table 2. Most studies used the NIHSS score to measure initial stroke severity except for 3 studies, but the employed analytic methods were highly variable across studies, comparing median NIHSS scores or proportion of mild stroke with variable thresholds. In 3 of the 17 studies, prestroke statin was significantly associated with milder initial stroke severity or higher proportion of mild stroke [42,48,56]. Seven studies provided ORs with 95% CI (adjusted ORs in 5 studies and unadjusted ORs in 2 studies) [34,38,41,46,53,55,56]. Pooling 7 studies involving 6,806 patients showed that prestroke statin use was associated with milder stroke severity at stroke onset (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05-1.48; P= 0.013). Heterogeneity across studies was not found (P= 0.63, I2=0%) (Figure 2A). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.322) (Supplemental Figure 1). Pooling 5 studies providing adjusted ORs also showed a significant prestroke statin effect on initial stroke severity (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04-1.48; P=0.018) (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Association of prestroke statin use and initial stroke severity (A), good functional outcome (B), and short-term mortality (C, pooling studies providing OR; D, pooling studies providing HR). Values of OR or HR greater than 1.0 indicate that prestroke statin use was associated with milder initial stroke severity (A), good functional outcome (B), and higher risk of mortality (C and D). SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Prestroke statin effect on functional outcome

Three meta-analyses (outcome at 90 days outcome in 2 studies and discharge or 90 days in 1 study) [49,58,59] and 21 original articles (outcome at discharge or 7-10 days in 14 studies and at 90 days in 7 studies) [30-33,35,39-49,51,54,55,57] were identified and summarized in Table 2. For functional outcome endpoint, modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 0-2 was most widely employed as a good outcome (12 studies: 10 original articles and 2 meta-analyses). In 14 (12 original article and 2 meta-analyses) of the 24 studies, patients with prestroke statin were more likely to achieve good functional outcome. Pooling 19 original publications (involving 30,942 patien ts) [30-33,35,39,41-49,51,54,55,57], which provided adjusted ORs (95% CI), showed that prestroke statin use was associated with good functional outcome (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.29-1.75; P<0.001). There was a significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies (P=0.002, I2=55%). However, the heterogeneity was related to the magnitude of effect rather than the direction of effect (Figure 2B). A significant publication bias was found (P=0.001), but it was mainly attributed to studies with relatively small sample sizes (Supplemental Figure 3). Regarding ischemic stroke subtypes, 1 meta-analysis showed that the association of prestroke statin use and good functional outcome was significant in patients with large artery atherosclerosis and small vessel occlusion, but not in cardioembolic stroke [49].

Prestroke statin effect on short-term mortality

Two meta-analyses (90-day mortality) [58,59] and 10 original articles (mortality at discharge in 3 studies, 20-30 days in 4 studies, 90 days in 2 studies, and 365 days in 1 study) [34,36-38,45,47,50,52,53,56] were identified and summarized in Table 2. In 8 (6 original articles and 2 meta-analyses) of the 12 studies, patients with prestroke statin had a lower mortality. Pooling 5 original publications (involving 4,508 patients), which provided ORs with 95% CI (adjusted ORs in 3 studies [36,45,47] and unadjusted ORs in 2 studies [34,38]), showed that prestroke statin use was associated with lower mortality (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.82; P=0.011). A significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies was found (P=0.03, I2=64%), but the treatment effect was in the same direction except for 1 study (Figure 2C). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.624) (Supplemental Figure 4). Pooling 3 studies providing adjusted ORs also showed a significant association of prestroke statin use with reduced mortality (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.18-0.70; P=0.003) (Supplemental Figure 5). Two studies (involving 13,488 patients) reported adjusted HRs instead of ORs [52,53]. Pooling these 2 studies also showed that prestroke statin use was associated with lower mortality (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93; P=0.0003). There was no significant heterogeneity across the studies (P=0.36, I2=0%) (Figure 2D).

In-hospital statin effect in acute ischemic stroke

We identified 11 articles (10 original articles and 1 meta-analysis) that assessed the in-hospital statin effect on functional outcome or short-term mortality (Table 3) [35,47,51-53,57,59-63].

Table 3.

Studies of in-hospital statin effect in acute ischemic stroke

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Age | Women (%) | In-hospital statin use (%) | Time point | Effect on functional outcome | Effect on mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moonis et al. [35] | 2005 | 852 | International | RCT, post-hoc | 68 | 48 | 14.4 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.57 (1.04-2.38) | NR |

| Ní Chróinín et al. [47] | 2011 | 445 | Ireland | Population-based | 71 | 49 | 71 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.88 (0.971-3.91) | Significant reduction OR, 0.19 (0.07-0.48) |

| Hjalmarsson et al. [53] | 2012 | 799 | Sweden | Single | 78 | 52 | 60.9 | 90 or 365 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 at 90 days OR, 2.09 (1.25-3.52) | Significant reduction at 365 days |

| Tsai et al. [60] | 2012 | 100 | Taiwan | Single | 63 | 35 | 50 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 Data not shown | NR |

| Yeh et al. [61] | 2012 | 514 | Taiwan | Single | 74 | 52 | 23.5 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 0.81 (0.43-1.51) | Non-significant increase HR, 1.68 (0.79-3.56) |

| Flint et al. [51,52] | 2012 | 12,689 | USA | Multicenter | 75 | 53 | 49.6 | Discharge or 1 year | Significant, discharge to home OR, 1.18 (1.08-1.30) | Significant reduction at 1 year HR, 0.55 (0.50-0.61) |

| Song et al. [62] | 2014 | 7,455 | China | Multicenter | 64 | 39 | 43.3 | Discharge or 3 months | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.05 (0.90-1.23) at 3 months | Significant reduction OR, 0.51 (0.38-0.67) at discharge |

| Al-Khaled et al. [63] | 2014 | 12,781 | Germany | Population-based | 73 | 49 | 59 | Discharge | Significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 1.25 (1.11-1.43) | Significant reduction OR, 0.39 (0.29-0.52) |

| Moonis et al. [57] | 2014 | 1618 | USA | Multicenter | 67 | 52 | 11.6 | Discharge | Significant, discharge to home OR, 2.63 (1.61-4.53) | NR |

| Ní Chróinín et al. [59] | 2013 | 4,066/5,083* | Meta-analysis | 5 studies | 71.3 | 33-61 | 14-71 | Discharge or 30 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.9 (1.59-2.27) | Significant reduction OR, 0.15 (0.07-0.31) |

Provided ORs (95% CIs) are adjusted ORs otherwise indicated, and ORs from meta-analyses are pooled ORs.

Numerator for mRS outcome sample size and denominator for mortality outcome sample size.

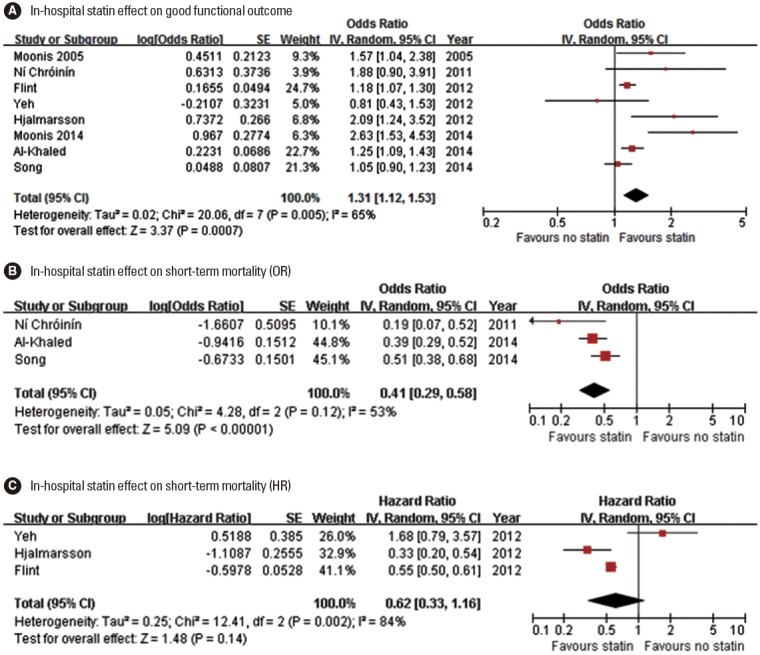

In-hospital statin effect on functional outcome

One meta-analysis (at discharge or 30 days) [59] and 9 original articles (at discharge in 4 studies and at 90 days in 5 studies) [35,47,51,53,57,60-63] assessed the in-hospital statin effect on functional outcome (Table 3). For functional outcome endpoint, mRS 0-2 outcome was most commonly used as a good functional outcome (in 7 studies: 6 original articles and 1 meta-analysis). In 7 (6 original article and 1 meta-analysis) of the 10 studies, patients with in-hospital statin had a better functional outcome. Pooling 8 studies (involving 37,153 patients) [35,47,51,53,57,61-63], which provided adjusted ORs (95% CI), showed that in-hospital statin use was associated with good functional outcome (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.12-1.53; P=0.001). There was a significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies (P=0.005, I2=65%), but the treatment effect was generally in the same direction except for 1 study (Figure 3A). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.322) (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Association of in-hospital statin use and good functional outcome (A), and short-term mortality (B, pooling studies providing ORs; C, pooling studies providing HRs). Values of OR or HR greater than 1.0 indicate that in-hospital statin use was associated with good functional outcome (A), and higher risk of mortality (B and C). SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

In-hospital statin effect on short-term mortality

One meta-analysis (at discharge or 30 days) and 6 original articles (at discharge in 2 studies, 90 days in 2 studies, and 365 days in 2 studies) assessed the in-hospital statin effect on shortterm mortality (Table 3). Of the 7 studies, 6 studies (5 original article and 1 meta-analysis) showed that patients with in-hospital statin use had a significantly lower mortality, whereas 1 study reported non-significant increase in mortality with in-hospital statin use. Three original articles provided adjusted ORs with 95% CI, and pooling these 3 studies involving 20,681 patients showed that in-hospital statin use was associated with lower mortality (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.29-0.58; P<0.001). A non-significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies was found across the studies (P= 0.12, I2=53%) (Figure 3B). Three original articles provided adjusted HRs with 95% CI, and pooling these 3 studies involving 14,002 patients showed that in-hospital statin use was not significantly associated with lower mortality (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.33-1.16; P=0.138). A significant and substantial heterogeneity across the studies was found (P=0.002, I2=84%) (Figure 3C).

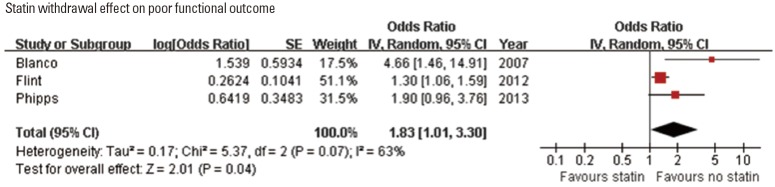

Statin withdrawal effect in acute ischemic stroke

Statin withdrawal effect was tested in one RCT performed in a single center [64], and explored in three observational studies (Table 4) [51,52,55]. Of 3 studies assessing functional outcome (adjusted ORs for 90-day mRS 3-6 outcome in one study and for poor discharge disposition in 2 studies) [51,55,64], 2 studies showed that statin withdrawal was associated with poor outcome [51,64]. Pooling the 3 studies involving 13,583 patients showed that statin withdrawal was associated with poor functional outcome (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.01-3.30; P=0.045). A significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies was found (P=0.07, I2=63%) (Figure 4). In one study, statin withdrawal was associated with an increased risk of 1-year mortality (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 2.1-2.9; P<0.001) [52].

Table 4.

Studies of statin withdrawal effect in acute ischemic stroke

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Age | Women (%) | Stroke type | Statin withdrawal (%) | Time point | Effect on functional outcome Findings for functional outcome | Effect on mortality Findings for mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanco et al. [64] | 2007 | 89 | Spain | Single/RCT | 67 | 49 | AIS | 51.7 | 90 days | mRS 3-6 OR, 4.66 (1.46, 14.91) | NR |

| Flint et al. [51,52] | 2012 | 12,689 | USA | Multicenter | 75 | 53 | AIS | 3.7 | Discharge or 1 year | Significant, discharge to rehab, nursing care, or death OR, 1.30 (1.06-1.59) at discharge | Significant increase at 1 year HR, 2.5 (2.1-2.9) |

| Phipps et al. [55] | 2013 | 804 | USA | Single | 86 | 64 | AIS | NR | Discharge | Non-significant, discharge to hospice or death OR, 1.90 (0.96-3.75) | NR |

Provided ORs (95% CIs) are adjusted ORs otherwise indicated.

Figure 4.

Association of statin withdrawal during hospitalization and poor functional outcome. Values of ORs greater than 1.0 indicate that statin withdrawal during hospitalization was associated with poor functional outcome. SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Statin effect in patients with thrombolysis

We identified 17 studies (15 original articles, 4 meta-analyses, and 2 article providing both original data and meta-analysis findings) exploring statin effect on functional outcome, mortality, or symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation (SHT) in patients with thrombolysis (IV-TPA only in 12 studies, intra-arterial thrombolysis [IA] only in 2 studies, and IV-TPA or IA in 3 studies) (Table 5) [58,59,65-79].

Table 5.

Studies of statin in patients with thrombolysis

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center | Age | Women (%) | NIHSS | Thrombolysis | Pre-stroke or in-hospital statin use (%) | Time point | Effect on functional or mortality outcome | Effect on SHT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez-Sabín et al. [65] | 2007 | 145 | Spain | Single | 72 | 48 | 17 | IV-TPA | 17.9 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 5.26 (1.48-18.72) | Non-significant data not shown |

| Bang et al. [66] | 2007 | 104 | USA | Single | 70 | 51 | 16 | IV-TPA or IA | 25 | NR | Non-significant P= 0.566 | |

| Uyttenboogaart et al. [67] | 2008 | 252 | Netherlands | Single | 68 | 46 | 12 | IV-TPA | 12.3 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 0.70 (0.25-1.94) | Non-significant OR, 0.99 (0.18-5.43) |

| Meier et al. [68] | 2009 | 311 | Switzerland | Single | 63 | 43 | 14 | IA | 17.7 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 (P= 0.728) Mortality (P= 0.861) | Significant, more any ICH OR, 2.70 (1.16-6.44) |

| Restrepo et al. [69] | 2009 | 142 | USA | Single | 69 | 49 | 17 | IA | 14.8 (pre- and post-stroke) | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 3.22 (0.57-18.03) | Non-significant Unadjusted OR, 1.1 |

| 31.7 (post-stroke) | Non-significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 2.091 (0.71-6.13) | NR | ||||||||||

| Miedema et al.[70] | 2010 | 476 | Netherlands | Single | 69 | 46 | 13 | IV-TPA | 20.6 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.11 (0.61-2.01) | Non-significant OR, 1.60 (0.57-4.37) |

| Engelter et al. [71] | 2011 | 4,012 | Europe | Multicenter | 68 | 44 | 12.4 | IV-TPA | 22.9 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1: OR, 0.89 (0.74-1.06) Mortality: unadjusted OR, 1.29 (0.86-1.94) | Non-significant R, 1.32 (0.94-1.85) for ECASS II, 1.16 (0.87-1.56) for NINDS |

| Cappellari et al. [72] | 2011 | 178 | Italy | Single | NR | 42 | NR | IV-TPA | 24.2 (pre- and post-stroke) | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 P=NS | Significant, more SHT OR, 6.65 (1.58-29.12) |

| 35.4 (post-stroke) | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 6.18 (1.43-26.62) | Non-significant P=NS | ||||||||||

| Meseguer et al. [73] | 2012 | 606 | France | Single | 67 | 43 | 13 | IV-TPA or IA | 24.8 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1, 1.55 (0.99-2.44) Mortality 0.80 (0.43-1.46) | Non-significant OR, 0.57 (0.22-1.49) |

| Rocco et al. [74] | 2012 | 1,066 | Germay | Single | 73 | 47 | 12 | IV-TPA | 20.5 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1, 1.14 (0.76-1.73) Mortality 1.32 (0.82-2.10) | Non-significant OR, 1.18 (0.56-2.48) |

| Martinez-Ramirez et al. [75] | 2012 | 182 | Spain | Single | 68 | 46 | 14 | IV-TPA | 16.3 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 OR not provided | Non-significant OR not provided |

| Cappellari et al. [76] | 2013 | 2,072 | Italy | Multicenter | 67 | 42 | 12.6 | IV-TPA | 40.5 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2, 1.63 (1.18-2.26) Mortality 0.48 (0.28-0.82) | Non-significant OR, 0.52 (0.20-1.34) |

| Zhao et al. [77] | 2014 | 193 | China | Single | 65 | 36 | 8.8 | IV-TPA | 24.4 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1 P=0.913 (unadjusted) | Non-significant P=0.965 (unadjusted) |

| Scheitz et al. [78] | 2014 | 1,446 | Germany, Switzerland | Multicenter | 75 | 46 | 11 | IV-TPA | 21.9 | 90 days | Significant, mRS 0-2 OR, 1.80 (1.29-2.51) | Significant, more SHT with medium- and high-dose statin OR, 2.4 (1.1-5.3) for medium and 5.3 (2.3-12.3) for high |

| Scheitz et al. [79] | 2015 | 481 | Germany | Single | 74 | 50 | 11 | IV-TPA | 17.2 | 90 days | Non-significant mRS 0-2, 1.22 (0.68-2.20) Mortality 0.64 (0.30-1.37) | Non-significant P=0.63 (unadjusted) |

| Cordenier et al. [58] | 2011 | 1,039 | Meta-analysis | 3 studies | NR | NR | NR | IV- or IA | 18.5 | NR | Significant, more SHT OR: 2.34 (CI 1.31-4.17) | |

| Ní Chróinín et al.[59] | 2013 | 4,993 | Meta-analysis | 5 studies | 68.6 | 44 | NR | IV-TPA | 22.3 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-1 OR, 1.01 (0.88-1.15) | NR |

| Significant mortality increase OR, 1.25 (1.02-1.52) | ||||||||||||

| Meseguer et al. [73] | 2012 | 6,263/6,899 | Meta-analysis | 11 studies | NR | NR | NR | IV-TPA or IA | 22.1 | Variable | Non-significant, favorable outcome OR, 0.99 (0.88-1.12) | Significant, more SHT OR, 1.55 (1.23-1.95) |

| Non-significant for studies (n=5524) with adjustment OR, 1.31 (0.97-1.76) | ||||||||||||

| Martinez-Ramirez et al. [75] | 2012 | 1,055/910 | Meta-analysis | 3 studies | NR | NR | NR | IV-TPA | 18.4 | 90 days | Non-significant, mRS 0-2 and mortality mRS 0-2, OR, 1.09 (0.73-1.61); mortality OR, 1.32(0.84-2.07) | Significant, more SHT |

Provided ORs (95% CIs) are adjusted ORs otherwise indicated, and ORs from meta-analyses are pooled ORs.

*Numerator for mRS or mortality outcome sample size and denominator for SHT outcome sample size.

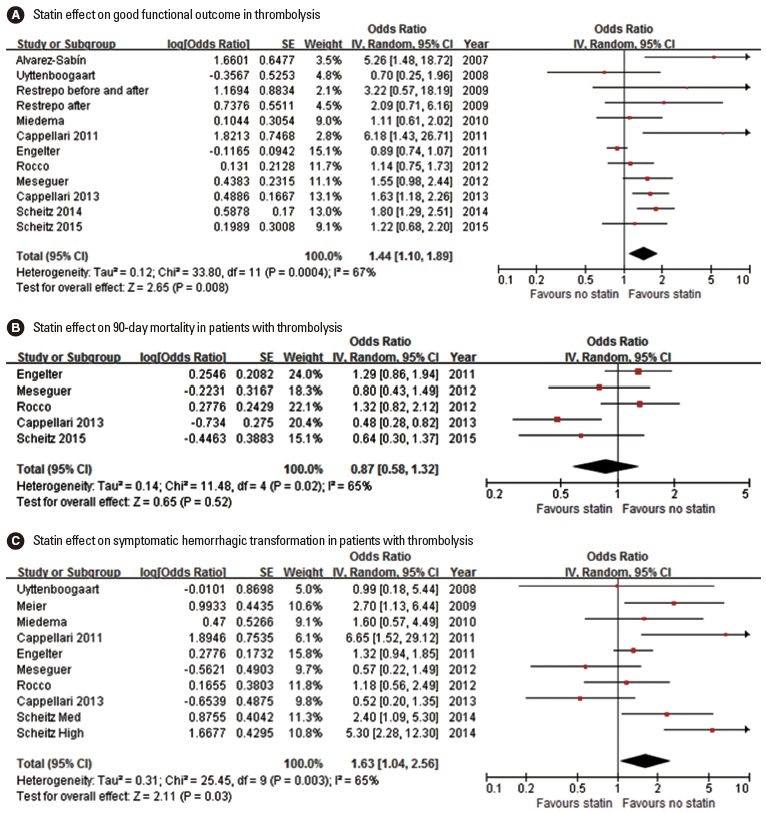

Statin effect on functional outcome in patients with thrombolysis

Fifteen studies (14 original articles, 3 meta-analyses, and 2 article providing both original data and meta-analysis findings) reported the statin effect on functional outcome [59,65,67-74,76-79]. Good functional outcome was defined as mRS 0-1 in 6 studies and mRS 0-2 in 8 studies, and mix-up of variable criteria in 1 meta-analysis. In earlier 3 meta-analyses [59,73,75], statin was not associated with good functional outcome, whereas 5 studies among the 14 original articles showed that statin was associated with good functional outcome [65,67,72,76,78]. Pooling 11 original articles (involving 10,876 patients, 1 article providing 2 ORs for both statin before and after and statin after only) [65,67,69-74,76,78,79], which provided adjusted ORs with 95% CI, showed that statin use in patients treated with thrombolysis was associated with good functional outcome (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.10-1.89; P=0.008). A significant and modest heterogeneity was found across the studies (P<0.001, I2=67%), but the direction of treatment effect was generally consistent except for 2 studies (Figure 5A). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.493) (Supplemental Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Association of statin use and good functional outcome (A), 90-day mortality (B), and symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation (C). Values of ORs than 1.0 indicate that statin use was associated with good functional outcome (A), higher risk of mortality (B), and higher risk of symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation (C). SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Statin effect on mortality in patients with thrombolysis

Statin effect on the 90-mortality in patients with thrombolysis was assessed in 2 meta-analyses and 6 original articles (Table 5) [58,59,68,71,73,74,76,79]. Among the 3 meta-analyses, 1 meta-analysis showed that statin use was associated with increased mortality [59]. Of the 6 original articles, 1 study showed that, statin use was significantly associated with lower mortality [76], but the other studies found no significant effect. Pooling 5 original articles (involving 8,237 patients) [71,73,74,76,79], which provided ORs with 95% CI (adjusted OR in 4 studies and unadjusted OR in 1 study), showed that statin use in patients treated with thrombolysis neither increased nor decreased mortality (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.58-1.32; P=0.518). A significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies was found (P=0.02, I2=65%) (Figure 5B). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.142) (Supplemental Figure 8). Pooling 4 studies providing adjusted ORs also showed that statin use was not associated with mortality in patients with thrombolysis (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.48-1.25; P=0.289) (Supplemental Figure 9).

Statin effect on symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation in patients with thrombolysis

Sixteen studies (15 original articles, 3 meta-analyses, and 2 article providing both original data and meta-analysis findings) reported the statin effect on SHT (Table 5) [58,65-79]. In 2 [58,75] of the 3 meta-analyses and 3 [68,72,78] of the 15 original articles, statin use was associated with an increased risk of SHT. Pooling 9 original articles (involving 10,419 patients) [67,68,70-74,76,78], which provided adjusted ORs with 95% CI, showed that statin use in patients treated with thrombolysis was associated with an increased risk of SHT (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.04-2.56; P=0.035). A significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies was found (P=0.003, I2=65%) (Figure 5C). There was no significant publication bias (P=0.655) (Supplemental Figure 10).

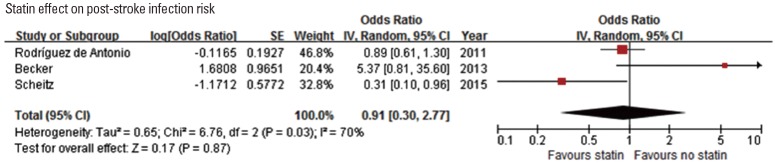

Statin effect on post-stroke infection

Since statins have immunomodulatory effect, several studies assessed the association of statin use with post-stroke infection. Among 4 studies [79-82], 1 study [79] showed that post-stroke pneumonia was less frequent in patients with prestroke statin use among IV-TPA treated patients (Table 6). Pooling 3 original articles (involving 2,638 patients) [79,80,82], which provided ORs with 95% CI (adjusted OR in 2 studies and unadjusted OR in 1 study), showed that the effect of statin on post-stroke infection was not significant (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.30-2.77; P=0.867). There was a significant and modest heterogeneity across the studies (P=0.03, I2=70%) (Figure 6). Pooling 2 studies providing adjusted ORs also showed that statin use was not associated with post-stroke infection (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.07-18.87; P=0.916) (Supplemental Figure 11).

Table 6.

Studies of statin effect on post-stroke infection

| Study | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Age | Women (%) | Population | Prestroke statin use (%) | Effect on infection Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodríguez de Antonio et al. [80] | 2011 | 2,045 | Spain | Single | 69 | 43 | AIS | 15.0 | Non-significant unadjusted OR, 0.89 (0.61-1.29) |

| Rodríguez-Sanz et al. [81] | 2013 | 1,385 | Spain | Single | 68 | 40 | AIS | 26.5 | Non-significant OR not provided |

| Becker et al. [82] | 2013 | 112 | USA | Single | 57 | 35 | AIS | 70.5 | Non-significant OR, 5.37 (0.81-35.37) |

| Scheitz et al. [79] | 2015 | 481 | Germany | Single | 74 | 50 | AIS with IV-TPA | 17.3 | Significant, less pneumonia OR, 0.31 (0.10-0.94) |

Figure 6.

Association of statin use and post-stroke infection risk. Values of ORs greater than 1.0 indicate that statin use was associated with an increased risk of post-stroke infection. SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval.

Randomized controlled trials

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) study randomized patients at 1 to 6 months after stroke. Therefore, the trial results cannot be considered as a reliable guide for statin use in AIS. Literature search identified 6 RCTs (statin withdrawal effect on functional outcome in 1, statin effect on functional outcome in 1, recurrent stroke within 90 days in 1, early neurological improvement in 1, and surrogate markers in 2 studies) [64,83-87], and one meta-analysis (Table 7) [88]. In addition, one phase 1B dose-finding single arm trial using an adaptive design of increasing lovastatin up to 10 mg/kg/day assessed the safety of high-dose statin, which showed that the final model-based estimate of toxicity was 13% (95% CI 3%-28%) for a dose of 8 mg/kg/day [89]. There has been no large RCT, and the sample sizes of the published RCTs were small (ranging between 33 and 392), not adequately powered to assess the statin effect in AIS.

Table 7.

Clinical trials of statin in acute ischemic stroke

| RCT | Publication | N | Region | Center/design | Intervention | Stroke type | Interval | Age | Women (%) | NIHSS | Primary endpoint | Primary endpoint Finding | Effect on functional outcome | Effect on mortality | DRE | ICH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanco et al. [64] | 2007 | 89 | Spain | Single | Statin withdrawal for 3 days | AIS with prestroke statin | <24 hr | 67 | 49 | 13 | mRS 3-6 at 3 months | Significant | Significant more mRS 3-6 with withdrawal OR, 4.66 (1.46, 14.91) | NR | NR | NR |

| FASTER [83] | 2007 | 392 | International | Multicenter | Simvastath 40 mg/day | AIS | <24 hr | 68 | 47 | NR | Recurrent stroke within 90 days | Non-significant | NR | NR | Non-significant for myositis or LFT abnormality | NR |

| MISTICS [84] | 2008 | 60 | Spain | Multicenter, single arm trial | Simvasatin 40 mg/day | AIS | 3-12 hr | 73 | 48 | 12 | Inflammatory biomarkers | Non-significant | Non-significant, mRS distribution at 90 days P=0.86 | Non-significant data not shown | More infection | NR |

| NeuSTART [89] | 2009 | 33 | USA | Multicenter, single arm trial | Lovastatin, 1-10 mg/kg/day for 3 days | AIS | <24 hr | 62 | 52 | 5 | Muscle or hepatotoxicity | Estimated toxicity of 13% at 8 mg/kg/day | NR | NR | Estimated toxicity of 13% at 8 mg/kg/day | NR |

| Muscari et al. [85] | 2011 | 62 | Italy | Single | Aton/astatin 80 mg/day | AIS | <24 hr | 75 | 68 | 12.5 | NIHSS improvement ≥4 at 7 days | Non-significant, P=0.59 | Non-significant, mRS 0-1 at 90 days OR, 4.2 (0.8-22.3) | Non-significant 6.5% vs. 6.5% | Non-significant except for more LFT abnormalities | Non-significant |

| Beer et al. [86] | 2012 | 40 | Australia | Multicenter | Aton/astatin 80 mg/day | AIS | <96 hr | 69 | 29 | 7 | Infarct size at days 3 and 30 | Non-significant, P=0.786 at 3 days and P=0.630 at 30 days | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Zare et al. [87] | 2012 | 55 | Iran | Single | Lovastatin, 20 mg/day | MCA infarction | NR | 66 | 47 | 15 | Not specified | Non-significant, BI at 90 days P=0.22 | Non-significant at 90 days P=0.26 | NR | NR | |

| Squizzato et al. [88] | 2011 | 431 | Meta-analysis | 7 studies | Statins | AIS | <2 weeks | NR | NR | NR | NR | Non-significant OR, 1.51 (0.60-3.81) | Can not be estimated | NR |

Provided ORs (95% CIs) are adjusted ORs otherwise indicated, and ORs from meta-analyses are pooled ORs.

Markers of Inflammation after Simvastatin in Ischemic Cortical Stroke (MISTICS) was a pilot, double-blind, randomized, multicenter clinical trial, comparing inflammatory biomarkers between simvastatin versus placebo in patients with cortical AIS [84]. The trial failed to demonstrate the anti-inflammatory effect of statin in human stroke despite rapid and sustained reduction of total and LDL-C levels with simvastatin. For clinical endpoints, patients on simvastatin compared to those on placebo were more likely to achieve NIHSS improvement 4 or more at 3 days, but did not achieve better 90-day mRS outcome.

Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack to Prevent Early Recurrence (FASTER) was a relatively large RCT comparing simvastatin 40 mg versus placebo in 392 patients with a transient ischemic attack or minor stroke within the previous 24 hours [83]. Because of the slow enrollment rate, the trial was early terminated after enrolling only 392 patients and thereby substantially underpowered. The rate of the primary endpoint of recurrent stroke within 90 days was 10.6% for the simvastatin group versus 7.3% for the placebo group (relative risk [RR], 1.3; 95% CI, 0.7-2.4; P=0.64).

Although the benefit of early statin initiation in AIS has not been demonstrated in RCTs, the harmful effect of statin withdrawal was demonstrated in a small, single center, randomized trial [64]. In the trial, 89 patients with prestroke statins and hemispheric ischemic stroke within 24 hours were randomized to either transient statin withdrawal for the first 3 days or to continuation of statin treatment with atorvastatin 20 mg daily. The withdrawal group versus the continuation group was more likely to have poor functional outcome at 90 days (mRS 3-6, primary endpoint) (60.0% vs. 39.0%; adjusted OR [95% CI], 4.66 [1.46 to 14.91]), to experience early neurological deterioration of worsening NIHSS score 4 or more (65.2% vs. 20.9%; adjusted OR [95% CI], 8.67 [3.05 to 24.63]), and to have a greater infarct volume increase between 4 and 7 days. Based on this trial results, the American Stroke Association guidelines recommend the continuation of statin therapy during the acute period among patients already taking statins at the time of ischemic stroke (Class IIa; LOE B). However, the American Stroke Association guidelines do not provide specific recommendations regarding when to start statins in AIS patients with no prior statin treatment [90].

In a recent meta-analysis including 7 published and unpublished RCTs involving 431 patients with AIS or transient ischemic attack within 2 weeks, all-cause mortality did not differ between the statin and placebo groups (OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.60 to 3.81) [88].

Discussion

Our systematic review could not find the evidence of statin benefit in AIS from RCTs although a small RCT demonstrated the harm of statin withdrawal. The results from observational studies were inconsistent. However, our updated meta-analysis using available data from original publications suggests that 1) prestroke statin use might reduce stroke severity at stroke onset, functional disability, and short-term mortality, 2) immediate post-stroke statin treatment might reduce functional disability and short-term mortality, whereas statin withdrawal might lead to worse outcome, and 3) in patients treated with thrombolysis, statins might improve functional outcome despite of an increased risk of SHT.

Imaging surrogate maker studies would provide a proof-of-concept for potential mechanisms of statin benefit in AIS. In general, surrogate marker studies suggest that statin benefit might be mediated by more collaterals and better reperfusion in AIS, and the findings in human with AIS are consonant with animal experiment study findings of improved cerebral flow secondary to upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, enhanced fibrinolysis, and reducing infarct size with statin treatment [3-5].

Investigating the prestroke statin effect would be a useful approach to assess the neuroprotective effect of statins in AIS. However, an RCT testing prestroke statin effect is not practically feasible because it requires a tremendous sample size. Given the neuroprotective effect of statins from animal experiment studies and imaging surrogate marker studies in human stroke, prestroke statin might limit ischemic brain damage and lead to mild stroke severity, and this effect, in part, might contribute to the better functional outcome with prestroke statin use. However, most published articles failed to show that prestroke statin was associated with less severe stroke. Since the statin benefit would not be substantial, the small sample sizes of the most published articles might account for the negative results. Previously, no meta-analysis has explored this statin effect. In our meta-analysis including data from 6,806 patients, pre-stroke statin use was associated with a 1.24-fold greater odds of stroke with milder severity, suggesting statin’s neuroprotective effect during acute cerebral ischemia in human. A recent Korean large retrospective study (n=8,340) using propensity score matching analysis showed that prestroke stroke use was associated with mild stroke severity at presentation [91].

An earlier post-hoc analysis of the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels study explored statin effect on functional outcome in patients with recurrent stroke (i.e., prestroke statin effect on recurrent stroke), which had an advantage of randomizing patients either to statin or placebo. The authors suggested that the outcome of recurrent ischemic cerebrovascular events might be improved among statin users as compared with patients on placebo. However, the result was significant for the overall cohort, including patients with event-free as well as those with recurrent stroke. The analysis restricted patients with recurrent ischemic stroke outcome did not show a significant benefit of statin on functional outcome [40].

For the statin effect on functional outcome, 2 previous meta-analyses (patients included in functional outcome analysis: n=11,965 in one study by Biffi et al. [49] and n = 17,152 in another by Ní Chróinín et al. [59]) showed the association of prestroke statin use with good functional outcome. In accord with previous results, the finding of our updated meta-analysis including more patients (n=30,942) strongly suggests that prestroke statin use might improve functional outcome. It is unclear whether, in addition to neuroprotection during ischemia, statin’s facilitation of recovery after stroke as shown in animal experiments [9], leads to the better functional outcome. In a recent large observational study in Korea, even after adjusting initial stroke severity as well as other covariates, prestroke statin users compared to non-users were more likely to achieve good outcome (mRS 0-2 outcome) at discharge, suggesting statin’s dual effect of neuroprotection and neurorestoration [91].

Our updated meta-analyses showed that statin whether administered prior to stroke or immediately after stroke was associated with better survival, as observed in earlier meta-analyses [58,59]. In addition to better functional outcome, preventing recurrent vascular event might account for the statin benefit of reducing short-term mortality. In a meta-analysis of 7 RCTs in patients with acute coronary syndrome, statin initiation during acute period was associated with reduced mortality [92]. Therefore, statin therapy might have beneficial effect of reducing mortality in patients with acute ischemia in the brain as well as in the heart. In patients with recent acute coronary syndrome, high intensity statin versus moderate intensity statin had a greater benefit in reducing mortality [93]. For patients with AIS, a large observational study showed that 1-year survival benefit with statin during AIS was greater with high-dose statins than with low-dose statins [52]. However, there has been no evidence from RCTs.

Worse outcome with statin withdrawal in a small RCT might indirectly indicate the statin benefit in AIS [64]. Supporting the RCT finding, a large observational study [51] and our meta-analysis showed the harmful effect of statin withdrawal during AIS. In the RCT, statin withdrawal even for a brief period of 3 days led to early neurological deterioration and greater infarct volume increase as well as 90-day worse functional outcome. Therefore, the potential mechanisms might be related to, rather than LDL-lowering, pleiotropic effects on endothelial function, inflammation, platelet, and fibrinolytic system [1,3-5].

Statins have antithrombotic and fibrinolytic effects, and in the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels trial patients on high-dose atorvastatin compared to those on placebo had more hemorrhagic strokes. Therefore, among neurologists, there has been concern on the increased risk of hemorrhagic transformation with statin use in AIS, particularly for patients treated with thrombolysis. The current meta-analysis showed that statin was associated with an increased risk of SHT after thrombolysis, as shown in a previous meta-analysis [58]. However, despite the increased risk of SHT, the functional outcome was better with statin use in our meta-analysis, which was not observed in earlier meta-analyses [59,73,75]. Therefore, prestroke statin use would not be a contraindication for thrombolysis. However, whether statin therapy should be initiated immediately after reperfusion therapy in AIS as in acute coronary syndrom needs to be tested with RCTs.

This study has several limitations. Our findings were almost exclusively driven from data of observational studies, which are at risk of bias. In most outcomes, we found a large amount of heterogeneity in the results among the included studies. However, in general, the heterogeneity was brought by the magnitude of effect rather than the direction of effect. For several outcomes, unadjusted ORs as well as adjusted ORs were combined to generate pooled estimates. However, unadjusted ORs used were from limited articles with relatively small sample sizes. Therefore, the effect on our findings was not substantial as shown in additional analyses pooling adjusted ORs only. The current study did not assess the statin effect on early recurrent stroke, which would be of interest of topics on future investigation. Finally, if the literature search fails to find out all relevant articles, the result of meta-analysis is at risk of bias. As we only searched PubMed, several relevant articles might be missed. However, to minimize this risk, we performed additional hand search by reviewing references listed in the included original publications and meta-analyses.

In conclusion, the current systematic review supports the benefit of statins in AIS. However, the findings were largely driven by observational studies, and thereby the benefit needs to be confirmed by well-designed, large RCTs.

Footnotes

Hong KS has received lecture honoraria from Pfizer Korea related to the current topic.

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Endres M, Laufs U, Huang Z, Nakamura T, Huang P, Moskowitz MA, et al. Stroke protection by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA reductase inhibitors mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laufs U, Gertz K, Huang P, Nickenig G, Böhm M, Dirnagl U, et al. Atorvastatin upregulates type III nitric oxide synthase in thrombocytes, decreases platelet activation, and protects from cerebral ischemia in normocholesterolemic mice. Stroke. 2000;31:2442–2449. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amin-Hanjani S, Stagliano NE, Yamada M, Huang PL, Liao JK, Moskowitz MA. Mevastatin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, reduces stroke damage and upregulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase in mice. Stroke. 2001;32:980–986. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asahi M, Huang Z, Thomas S, Yoshimura S, Sumii T, Mori T, et al. Protective effects of statins involving both eNOS and tPA in focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:722–729. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein LB. Statins and ischemic stroke severity: cytoprotection. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2009;11:296–300. doi: 10.1007/s11883-009-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:977–987. doi: 10.1038/nrd1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon GJ, Kim SJ, Cho YH, Ryoo S, Bang OY. Antioxidant effects of statins in patients with atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease. J Clin Neurol. 2014;10:140–147. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2014.10.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang L, Jiang H, et al. Statins induce angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and synaptogenesis after stroke. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:743–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenestrand U, Wallentin L, Swedish Register of Cardiac Intensive Care (RIKS-HIA) Early statin treatment following acute myocardial infarction and 1-year survival. JAMA. 2001;285:430–436. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonarow GC, Wright RS, Spencer FA, Fredrick PD, Dong W, Every N, et al. Effect of statin use within the first 24 hours of admission for acute myocardial infarction on early morbidity and mortality. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenderink T, Boersma E, Gitt AK, Zeymer U, Wallentin L, Van de Werf F, et al. Patients using statin treatment within 24 h after admission for ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes had lower mortality than non-users: a report from the first Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1799–1804. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagashima M, Koyanagi R, Kasanuki H, Hagiwara N, Yamaguchi J, Atsuchi N, et al. Effect of early statin treatment at standard doses on long-term clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction (the Heart Institute of Japan, Department of Cardiology Statin Evaluation Program) Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1523–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, Ganz P, Oliver MF, Waters D, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, Lewis EF, Fox KA, White HD, et al. Early intensive vs a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes: phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.11.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winchester DE, Wen X, Xie L, Bavry AA. Evidence of pre-procedural statin therapy a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1099–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e663–e828. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828478ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:2574–2609. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823a5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. West Sussex, UK: Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shook SJ, Gupta R, Vora NA, Tievsky AL, Katzan I, Krieger DW. Statin use is independently associated with smaller infarct volume in nonlacunar MCA territory stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2006;16:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ovbiagele B, Saver JL, Starkman S, Kim D, Ali LK, Jahan R, et al. Statin enhancement of collateralization in acute stroke. Neurology. 2007;68:2129–2131. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264931.34941.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholas JS, Swearingen CJ, Thomas JC, Rumboldt Z, Tumminello P, Patel SJ. The effect of statin pretreatment on infarct volume in ischemic stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31:48–56. doi: 10.1159/000140095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ford AL, An H, D’Angelo G, Ponisio R, Bushard P, Vo KD, et al. Preexisting statin use is associated with greater reperfusion in hyperacute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:1307–1313. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargento-Freitas J, Pagola J, Rubiera M, Flores A, Silva F, Rodriguez-Luna D, et al. Preferential effect of premorbid statins on atherothrombotic strokes through collateral circulation enhancement. Eur Neurol. 2012;68:171–176. doi: 10.1159/000337862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malik N, Hou Q, Vagal A, Patrie J, Xin W, Michel P, et al. Demographic and clinical predictors of leptomeningeal collaterals in stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2018–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MJ, Bang OY, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Lee KH, et al. Role of statin in atrial fibrillation-related stroke: an angiographic study for collateral flow. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37:77–84. doi: 10.1159/000356114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pourati I, Kimmelstiel C, Rand W, Karas RH. Statin use is associated with enhanced collateralization of severely diseased coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 2003;146:876–881. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonsson N, Asplund K. Does pretreatment with statins improve clinical outcome after stroke? A pilot case-referent study. Stroke. 2001;32:1112–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.5.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marti-Fàbregas J, Gomis M, Arboix A, Aleu A, Pagonabarraga J, Belvis R, et al. Favorable outcome of ischemic stroke in patients pretreated with statins. Stroke. 2004;35:1117–1121. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000125863.93921.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greisenegger S, Mullner M, Tentschert S, Lang W, Lalouschek W. Effect of pretreatment with statins on the severity of acute ischemic cerebrovascular events. J Neurol Sci. 2004;221:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon SS, Dambrosia J, Chalela J, Ezzeddine M, Warach S, Haymore J, et al. Rising statin use and effect on ischemic stroke outcome. BMC Med. 2004;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253–258. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171746.63844.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298–1300. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165920.67784.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aslanyan S, Weir CJ, McInnes GT, Reid JL, Walters MR, Lees KR. Statin administration prior to ischaemic stroke onset and survival: exploratory evidence from matched treatment-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bushnell CD, Griffin J, Newby LK, Goldstein LB, Mahaffey KW, Graffagnino CA, et al. Statin use and sex-specific stroke outcomes in patients with vascular disease. Stroke. 2006;37:1427–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221315.60282.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chitravas N, Dewey HM, Nicol MB, Harding DL, Pearce DC, Thrift AG. Is prestroke use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors associated with better outcome? Neurology. 2007;68:1687–1693. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261914.18101.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeves MJ, Gargano JW, Luo Z, Mullard AJ, Jacobs BS, Majid A, Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Michigan Prototype Investigators Effect of pretreatment with statins on ischemic stroke outcomes. Stroke. 2008;39:1779–1785. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein LB, Amarenco P, Zivin J, Messig M, Altafullah I, Callahan A, et al. Statin treatment and stroke outcome in the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial. Stroke. 2009;40:3526–3531. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu AY, Keezer MR, Zhu B, Wolfson C, Côté R. Pre-stroke use of antihypertensives, antiplatelets, or statins and early ischemic stroke outcomes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:398–402. doi: 10.1159/000207444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martínez-Sánchez P, Rivera-Ordóñez C, Fuentes B, Ortega-Casarrubios MA, Idrovo L, Díez-Tejedor E. The beneficial effect of statins treatment by stroke subtype. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:127–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuadrado-Godia E, Jiménez-Conde J, Ois A, Rodríguez-Campello A, García-Ramallo E, Roquer J. Sex differences in the prognostic value of the lipid profile after the first ischemic stroke. J Neurol. 2009;256:989–995. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stead LG, Vaidyanathan L, Kumar G, Bellolio MF, Brown RD, Jr, Suravaram S, et al. Statins in ischemic stroke: just low-density lipoprotein lowering or more? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arboix A, García-Eroles L, Oliveres M, Targa C, Balcells M, Massons J. Pretreatment with statins improves early outcome in patients with first-ever ischaemic stroke: a pleiotropic effect of statins or a beneficial effect of hypercholesterolemia? BMC Neurol. 2010;10:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacco S, Toni D, Bignamini AA, Zaninelli A, Gensini GF, Carolei A, SIRIO Study Group Effect of prior medical treatments on ischemic stroke severity and outcome. Funct Neurol. 2011;26:133–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ní Chróinín D, Callaly EL, Duggan J, Merwick Á, Hannon N, Sheehan Ó, et al. Association between acute statin therapy, survival, and improved functional outcome after ischemic stroke: the North Dublin Population Stroke Study. Stroke. 2011;42:1021–1029. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai NW, Lin TK, Chang WN, Jan CR, Huang CR, Chen SD, et al. Statin pre-treatment is associated with lower platelet activity and favorable outcome in patients with acute non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke. Crit Care. 2011;15:R163. doi: 10.1186/cc10303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biffi A, Devan WJ, Anderson CD, Cortellini L, Furie KL, Rosand J, et al. Statin treatment and functional outcome after ischemic stroke: case-control and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;42:1314–1319. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hassan Y, Al-Jabi SW, Aziz NA, Looi I, Zyoud SH. Statin use prior to ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased inhospital mortality. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2011;25:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2010.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flint AC, Kamel H, Navi BB, Rao VA, Faigeles BS, Conell C, et al. Inpatient statin use predicts improved ischemic stroke discharge disposition. Neurology. 2012;78:1678–1683. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182575142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flint AC, Kamel H, Navi BB, Rao VA, Faigeles BS, Conell C, et al. Statin use during ischemic stroke hospitalization is strongly associated with improved poststroke survival. Stroke. 2012;43:147–154. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.627729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hjalmarsson C, Bokemark L, Manhem K, Mehlig K, Andersson B. The effect of statins on acute and long-term outcome after ischemic stroke in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aboa-Eboulé C, Binquet C, Jacquin A, Hervieu M, BonithonKopp C, Durier J, et al. Effect of previous statin therapy on severity and outcome in ischemic stroke patients: a populationbased study. J Neurol. 2013;260:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phipps MS, Zeevi N, Staff I, Fortunato G, Kuchel GA, McCullough LD. Stroke severity and outcomes for octogenarians receiving statins. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;57:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martínez-Sánchez P, Fuentes B, Martínez-Martínez M, Ruiz-Ares G, Fernández-Travieso J, Sanz-Cuesta BE, et al. Treatment with statins and ischemic stroke severity: does the dose matter? Neurology. 2013;80:1800–1805. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918d38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moonis M, Kumar R, Henninger N, Kane K, Fisher M. Pre and post-stroke use of statins improves stroke outcome. Indian J Community Med. 2014;39:214–217. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.143021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cordenier A, De Smedt A, Brouns R, Uyttenboogaart M, De Raedt S, Luijckx GJ, et al. Pre-stroke use of statins on stroke outcome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Acta Neurol Belg. 2011;111:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ní Chróinín D, Asplund K, Åsberg S, Callaly E, Cuadrado-Godia E, Díez-Tejedor E, et al. Statin therapy and outcome after ischemic stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized trials. Stroke. 2013;44:448–456. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.668277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai NW, Lee LH, Huang CR, Chang WN, Chen SD, Wang HC, et al. The association of statin therapy and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level for predicting clinical outcome in acute non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1861–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yeh PS, Lin HJ, Chen PS, Lin SH, Wang WM, Yang CM, et al. Effect of statin treatment on three-month outcomes in patients with stroke-associated infection: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:689–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song B, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang C, Wang A, et al. Association between statin use and short-term outcome based on severity of ischemic stroke: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:84389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Khaled M, Matthis C, Eggers J. Statin treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:597–601. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blanco M, Nombela F, Castellanos M, Rodriguez-Yáñez M, García-Gil M, Leira R, et al. Statin treatment withdrawal in ischemic stroke: a controlled randomized study. Neurology. 2007;69:904–910. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269789.09277.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvarez-Sabín J, Huertas R, Quintana M, Rubiera M, Delgado P, Ribó M, et al. Prior statin use may be associated with improved stroke outcome after tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2007;38:1076–1078. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258075.58283.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bang OY, Saver JL, Liebeskind DS, Starkman S, Villablanca P, Salamon N, et al. Cholesterol level and symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2007;68:737–742. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252799.64165.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uyttenboogaart M, Koch MW, Koopman K, Vroomen PC, Luijckx GJ, De Keyser J. Lipid profile, statin use, and outcome after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol. 2008;255:875–880. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meier N, Nedeltchev K, Brekenfeld C, Galimanis A, Fischer U, Findling O, et al. Prior statin use, intracranial hemorrhage, and outcome after intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1729–1737. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Restrepo L, Bang OY, Ovbiagele B, Ali L, Kim D, Liebeskind DS, et al. Impact of hyperlipidemia and statins on ischemic stroke outcomes after intra-arterial fibrinolysis and percutaneous mechanical embolectomy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:384–390. doi: 10.1159/000235625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miedema I, Uyttenboogaart M, Koopman K, De Keyser J, Luijckx GJ. Statin use and functional outcome after tissue plasminogen activator treatment in acute ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:263–267. doi: 10.1159/000275500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Engelter ST, Soinne L, Ringleb P, Sarikaya H, Bordet R, Berrouschot J, et al. IV thrombolysis and statins. Neurology. 2011;77:888–895. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c9135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cappellari M, Deluca C, Tinazzi M, Tomelleri G, Carletti M, Fiaschi A, et al. Does statin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke improve outcome after intravenous thrombolysis? A retrospective study. J Neurol Sci. 2011;308:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meseguer E, Mazighi M, Lapergue B, Labreuche J, Sirimarco G, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, et al. Outcomes after thrombolysis in AIS according to prior statin use: a registry and review. Neurology. 2012;79:1817–1823. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318270400b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rocco A, Sykora M, Ringleb P, Diedler J. Impact of statin use and lipid profile on symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage, outcome and mortality after intravenous thrombolysis in acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:362–368. doi: 10.1159/000335840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez-Ramirez S, Delgado-Mederos R, Marin R, Suárez-Calvet M, Sáinz MP, Alejaldre A, et al. Statin pretreatment may increase the risk of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage in thrombolysis for ischemic stroke: results from a case-control study and a meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2012;259:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cappellari M, Bovi P, Moretto G, Zini A, Nencini P, Sessa M, et al. The THRombolysis and STatins (THRaST) study. Neurology. 2013;80:655–661. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281cc83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao HD, Zhang YD. The effects of previous statin treatment on plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 level in chinese stroke patients undergoing thrombolysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2788–2793. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scheitz JF, Seiffge DJ, Tütüncü S, Gensicke H, Audebert HJ, Bonati LH, et al. Dose-related effects of statins on symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and outcome after thrombolysis for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:509–514. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scheitz JF, Endres M, Heuschmann PU, Audebert HJ, Nolte CH. Reduced risk of poststroke pneumonia in thrombolyzed stroke patients with continued statin treatment. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodríguez de Antonio LA, Martínez-Sánchez P, Martínez-Martínez MM, Cazorla-García R, Sanz-Gallego I, Fuentes B, et al. Previous statins treatment and risk of post-stroke infections. Neurologia. 2011;26:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodríguez-Sanz A, Fuentes B, Martínez-Sánchez P, Prefasi D, Martínez-Martínez M, Correas E, et al. High-density lipoprotein: a novel marker for risk of in-hospital infection in acute ischemic stroke patients? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:291–297. doi: 10.1159/000347077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Becker K, Tanzi P, Kalil A, Shibata D, Cain K. Early statin use is associated with increased risk of infection after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM, FASTER Investigators Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961–969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Montaner J, Chacón P, Krupinski J, Rubio F, Millán M, Molina CA, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muscari A, Puddu GM, Santoro N, Serafini C, Cenni A, Rossi V, et al. The atorvastatin during ischemic stroke study: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:141–147. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182206c2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beer C, Blacker D, Bynevelt M, Hankey GJ, Puddey IB. A randomized placebo controlled trial of early treatment of acute ischemic stroke with atorvastatin and irbesartan. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zare M, Saadatnia M, Mousavi SA, Keyhanian K, Davoudi V, Khanmohammadi E. The effect of statin therapy in stroke outcome: a double blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:68–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Squizzato A, Romualdi E, Dentali F, Ageno W. Statins for acute ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD007551. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007551.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]