Abstract

An 83-year-old woman presented with intermittent fever for 2 weeks. Chest radiography and computed tomography images showed multiple nodules and masses scattered in both lung fields. Tissue samples obtained by computed tomography-guided needle biopsy revealed extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKL). The lung is the major site of involvement and the skin may be the primary site. The radiological imaging of this case is different from the cases reported before. Besides, we reviewed the medical records of our hospital and searched the Pubmed database and found 12 cases altogether (include the case presented), which were diagnosed with pulmonary ENKL, and the features of chest images were studied. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the chest imaging features of pulmonary ENKL were reviewed. We conclude that if the radiographic manifestations are multiple patchy consolidations or multiple nodules and masses in both lungs with or without bilateral pleural effusions, the diagnostic considerations should include ENKL.

INTRODUCTION

ENKL is a newly recognized distinctive entity in the World Health Organization classification of lymphomas.1 It accounts for <1% of all lymphomas in Western countries and ∼3% to 9% of all lymphomas in Asia.2–4 ENKL of the lung is extremely rare. To our knowledge, there are only a few reports about pulmonary ENKL written in English to date.5–8 Radiological features especially on computed tomography (CT) imaging of pulmonary ENKL are still not well known because there are few reported cases available. Here, we describe a case of pulmonary ENKL with multiple masses in both lung fields, which is different from previously reported cases. Furthermore, we reviewed the medical records of our hospital and the literatures published previously and summarize the chest CT features of pulmonary ENKL. To our knowledge, it is the first time that chest imaging of pulmonary ENKL was reviewed.

Case Report

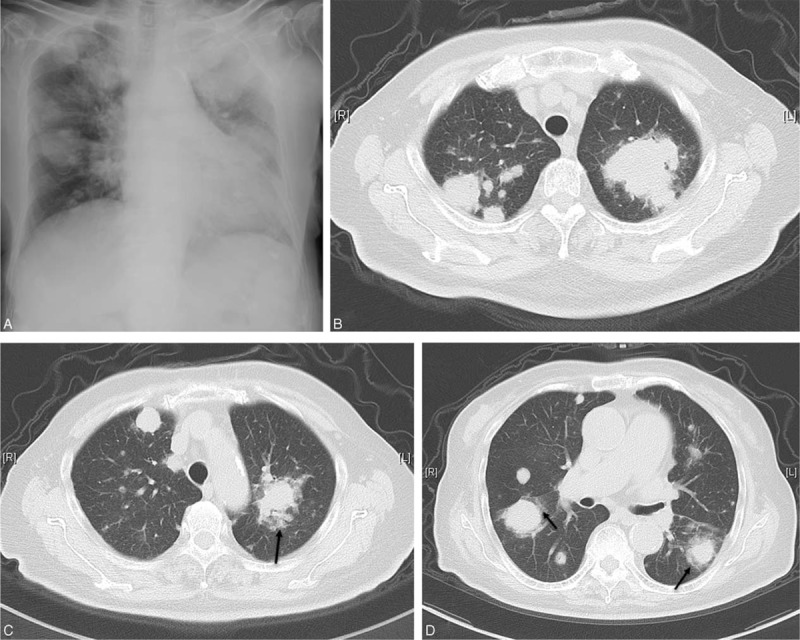

An 83-year-old woman presented with intermittent fever for 2 weeks. She had no cough, sputum, or chest pain. Laboratory test results showed white blood cell count of 5.39 × 109/L with a neutrophil percentage of 81.4%, hemoglobin of 115 g/L, and platelet count of 244 × 109/L. She was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics without improvement. The chest plain radiography and CT revealed multiple nodules and masses in both lung fields (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Chest radiograph showing multiple bilateral masses, the margins of which are relatively well defined; no cavitation is observed. (B–D) CT images on admission show multiple randomly distributed nodules and masses of variable size in both lung fields. Halo signs can be seen in some of the masses (arrows). CT = computed tomography.

The patient had been diagnosed with “panniculitis” because of lower limb skin ulceration 1 year before and prescribed prednisone 30 mg/day for 6 months.

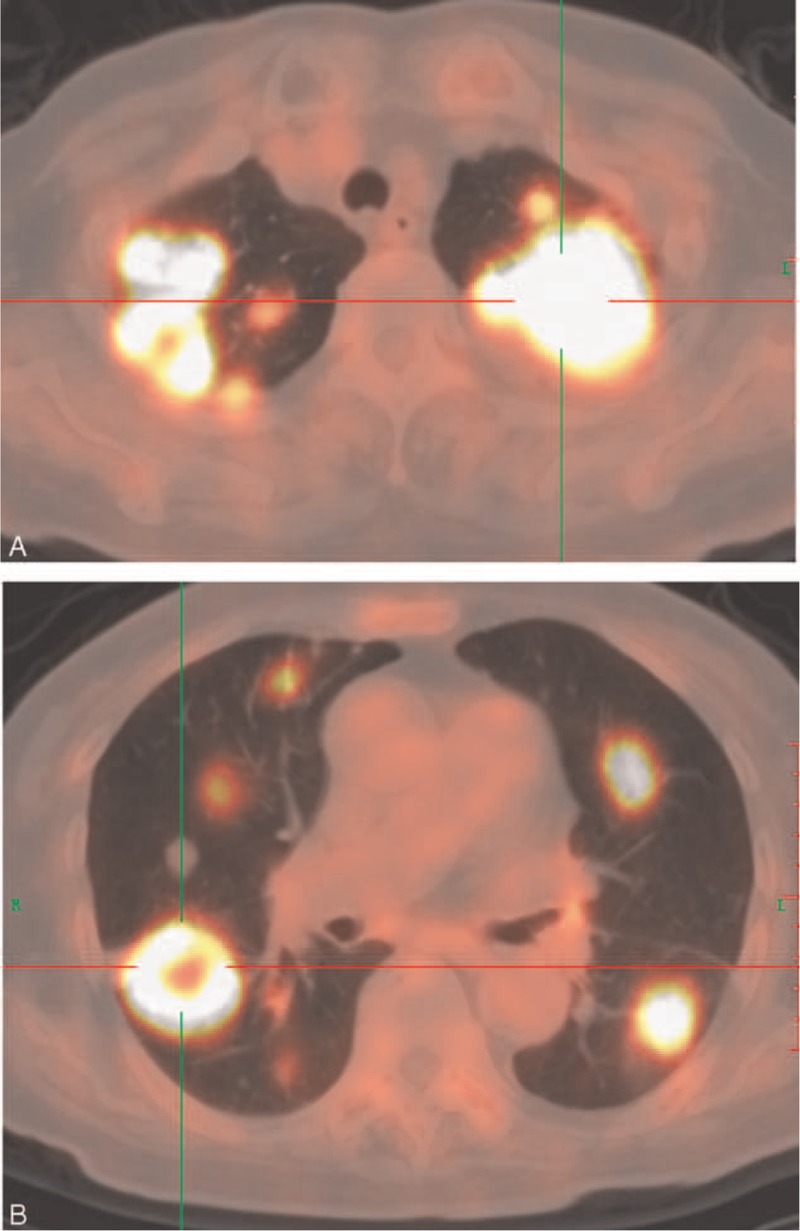

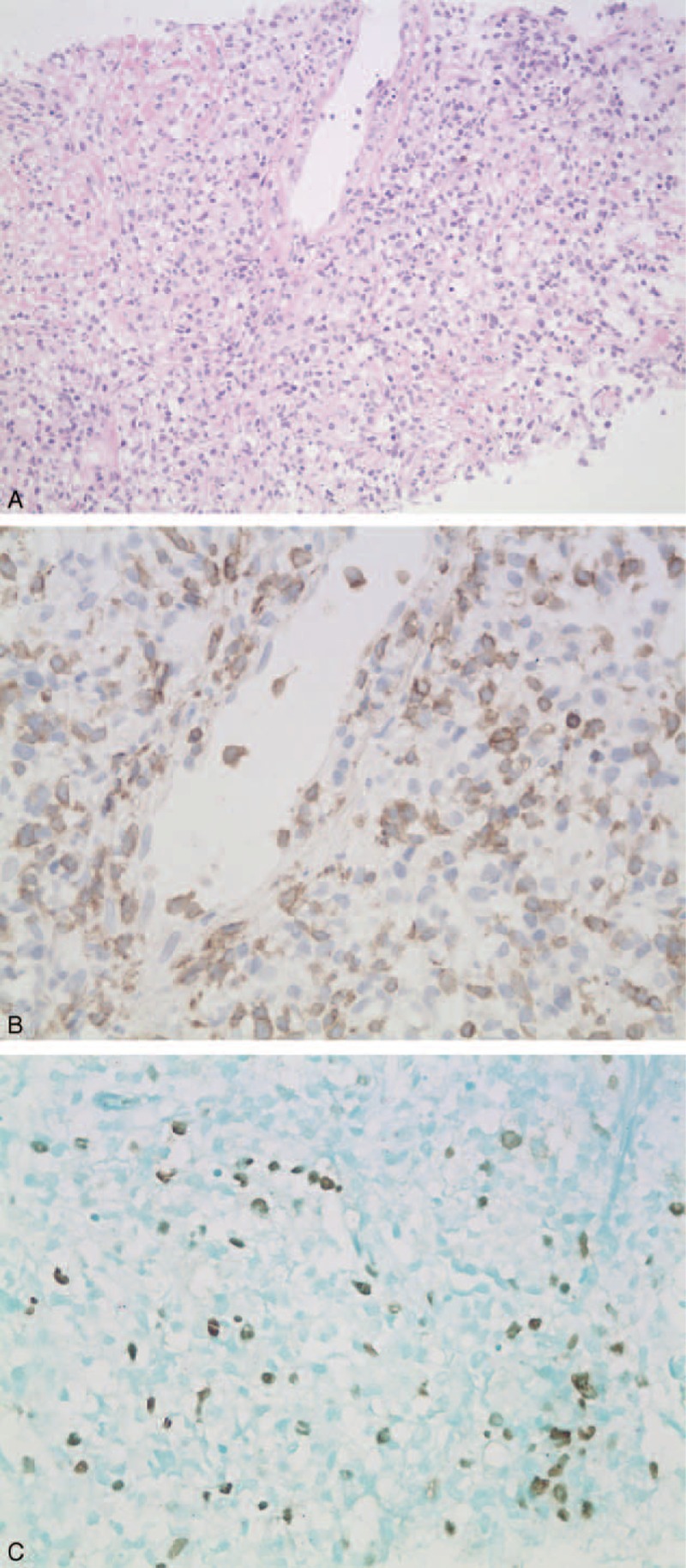

Laboratory tests including two sets of blood cultures, and tumor markers, including SCC, Cyfra21-1, CEA, Pro-GRP, NSE, CA15-3, and CA19-9 were all normal. The G test and GM test were both negative. Antinuclear antibody, anti-ENA antibodies, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were all negative. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose -positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET/CT) scan revealed multiple intense hypermetabolic uptake in both lung fields (SUVmax 21; Fig. 2). A CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsy was undertaken. The final biopsy revealed CD3 + , CD5 + , CD20 − , and CD56 ± cells. In situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-encoded RNA showed a positive reaction. The cells were angiocentric and angioinvasive (Fig. 3). Based on the neoplastic morphology and the immunohistochemical examination of the atypical lymphocytes, the pathological diagnosis was ENKL (nasal type). The patient refused to undergo chemotherapy and her clinical condition continued to deteriorate. Repeat blood tests showed the white blood cell count of 2.43 × 109/L with a neutrophil percentage of 69.6%, hemoglobin of 76 g/L, and platelet count of 86 × 109/L. Ferritin in the serum was increased to >2000 ng/mL and the triglyceride level was 6.29 mmol/L, and 2% hemophagocytes were detected in the bone marrow. The patient died of multiple organ failure on the 35th day after admission.

FIGURE 2.

PET image showing multiple intense hypermetabolic uptake in both lung fields. PET = positron emission tomography.

FIGURE 3.

Histological sections of the lung show proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells infiltrating the alveolar septa and invading blood vessels. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (×40). (B) Positive staining for CD3 (×40). (C) EBV-encoded small RNA is seen on immunohistochemical analysis (×40). EBV = Epstein–Barr virus.

Since this is a retrospective study and would not influence the diagnosis and treatment process of the patient, the ethical review is not necessary. When we prepared the manuscript, the patient had passed away, so the informed consent was not signed. We concealed the patient's personal information carefully in the manuscript and would never reveal it.

DISCUSSION

ENKL is rare and the nose and paranasal areas including the upper aerodigestive tract are the most commonly affected sites, followed by the skin and gastrointestinal tract. Lung involvement as the main manifestation is especially rare.9 In the present case, the lung may not have been the primary site of ENKL because a review of the patient's pathological sections from her lower limb skin and re-examination of the immunohistochemical staining by the pathologists confirmed that the pathological diagnosis was also ENKL. No other organ involvement was found by PET/CT. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that the skin was the primary site and the lung was the secondary site. It has been found that once the tumor develops outside the primary site, the disease progresses rapidly.5 The patient's clinical course seemed in accord with this finding. However, it is curious that the patient's lower limb skin was intact and the lesion was stable, while the patient was in hospital, and that there was no hypermetabolic uptake in her lower limb skin seen on the PET/CT scan. Zhou et al demonstrated that PET/CT presented high sensitivity (0.98) and specificity (0.99) in detecting the ENKL-related lesions.10 Therefore, it is reasonable to state that skin to lung is not a metastatic phenomenon but a multicentric involvement.

EBV Infection

EBV infection has been found to be associated with ENKL and hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS).11,12 Some research has suggested that NK/T-cell and T-cell peripheral lymphomas are responsible for the majority of lymphoma-associated HPS, and about half of lymphoma-associated HPS is associated with EBV infection.13 Our patient had EBV RNA positive and peripheral blood cytopenia, significantly elevated levels of ferritin and triglycerides, and a hemophagocytic phenomenon in the bone marrow, so she could have been diagnosed with HPS associated with EBV infection.

Imaging of Pulmonary ENKL

The CT findings of pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma are varied and nonspecific. It can be seen as patchy shadows, consolidations, nodules, and segmental or lobar atelectasis.14 Herein the CT scan of this case showed multiple nodules and masses in both lung fields (Fig. 1), which was different from the imaging findings in previous cases.5–7,15,16 The maximum diameter of the masses was ∼5 cm. In some masses, air bronchograms were visible and the margins were ill-defined and halo signs could be seen, whereas in other masses, the boundaries were quite distinct. The halo sign could raise concern for bleeding of surrounding tissue caused by invasion of vessels by lymphoma cells. However, it is difficult to differentiate lymphoma from fungal infection and vasculitis on CT images.

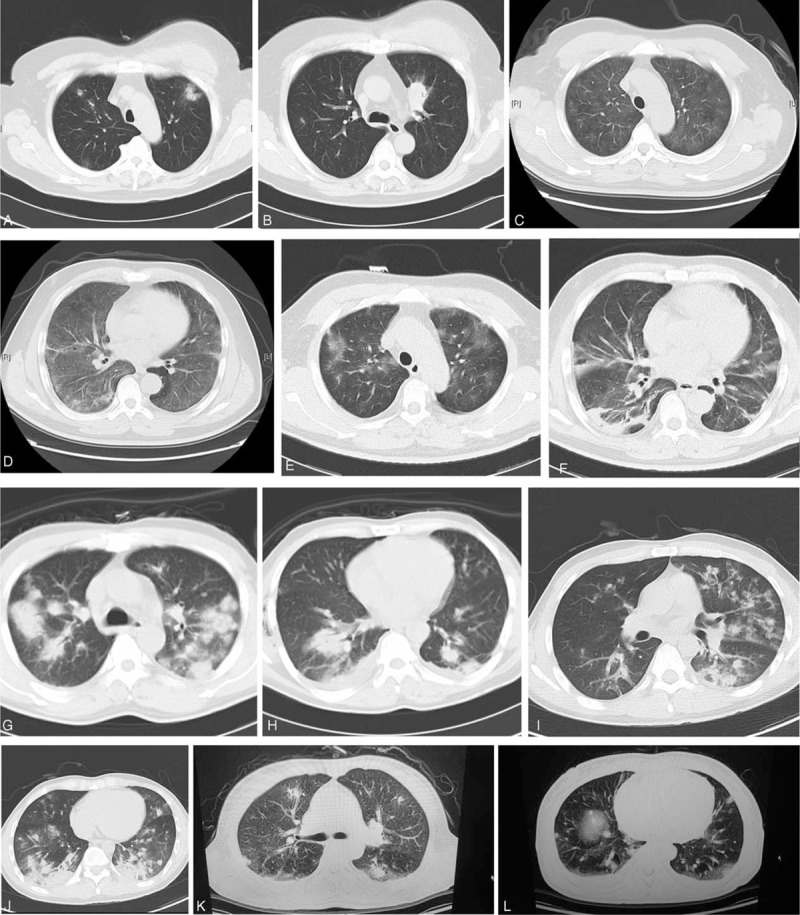

We hoped to be able to find some clues from radiographic imaging of pulmonary ENKL to shed light on this devastating disease because radiographic data is the first and the most convenient data that the physicians could get. We reviewed the medical records of our hospital for the previous 10 years and found 5 other cases of pulmonary ENKL, which were diagnosed through CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy or thoracoscopic lung biopsy. The chest images showed diffuse ground-glass opacity in both lung fields in 1 patient, bilateral multiple patchy infiltrations and consolidations in 2 patients, and bilateral multiple nodules in 2 patients. Bilateral pleural effusion was also seen in 2 patients. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy were not found (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Chest CT images of patients with pulmonary ENKL. (A,B) Patient 1: bilateral scattered patchy infiltrates and consolidation. (C,D) Patient 2: diffuse ground-glass opacity in both lung fields. (E,F) Patient 2: ∼2 weeks later. (G,H) Patient 3: bilateral multiple nodules and masses with bilateral effusion. (I,J) Patient 4: bilateral multiple nodules, infiltrates, and consolidations. (K,L) Patient 5: scattered multiple nodules, patchy infiltrates, and ground-glass opacity in both lung fields with bilateral effusion. CT = computed tomography, ENKL = extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma.

We also searched the PubMed database using the search terms “NK/T cell lymphoma AND lung” or “natural killer/T cell lymphoma AND lung”. We finally found 6 case reports with the diagnosis of pulmonary ENKL written in English or Chinese and with chest CT images.5–7,15,16 The chest images showed multiple infiltrations and patchy consolidations in both lung fields in 3 patients, unilateral pulmonary consolidation in 1 patient, and multiple nodules and masses in both lung fields in 2 patients. Bilateral pleural effusion could also be seen in 2 patients. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy were not found.

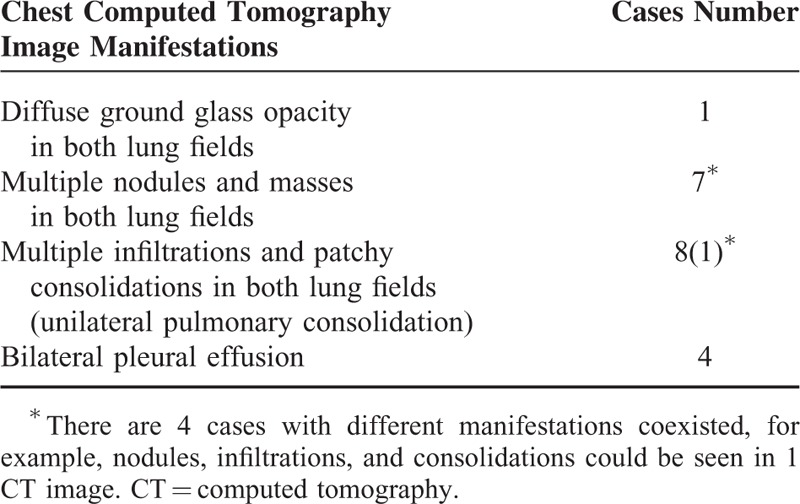

The chest imaging findings from a total of 12 patients are summarized in Table 1. We can draw some conclusions concerning the imaging features of pulmonary ENKL: diffuse or multiple lesions in both lung fields can be seen in almost all patients; patchy consolidations, nodules, and masses are the most frequent CT findings and infiltrations can also be seen; ground-glass opacity is relatively rare and may represent a relatively early stage of the disease because some areas of ground-glass opacity in this patient developed into consolidations at the end stage; and bilateral pleural effusion can accompany other lesions. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the chest imaging features of pulmonary ENKL were reviewed.

TABLE 1.

Chest Computed Tomography Image Manifestations of Pulmonary Extranodal Natural Killer/T-Cell Lymphoma

Treatment of ENKL

Concerning the treatment strategy, there is no essential difference whether the lung is the primary site or not. CHOP-based chemotherapy has been used for the treatment of ENKL, but with unsatisfactory results. However, in recent years, novel therapeutic approaches such as simultaneous chemoradiotherapy and l-asparaginase-based regimens including SMILE (steroid, methotrexate, ifosfamide, l-asparaginase, and etoposide) have improved the response to therapy and survival of ENKL patients. In patients with advanced ENKL, this regimen showed a complete remission rate of 35% to 50%, and an overall response rate of 74%.17 Nevertheless, due to the rarity of the ENKL, the best treatment strategy is still unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, pulmonary ENKL is rare. As this disease is rapidly progressive with a poor prognosis, it is important to fully understand it. Chest imaging in our patient showed multiple masses and nodules in both lung fields, which is different from previous findings. To our knowledge, it is the first time that pulmonary images of ENKL were studied and if the radiographic manifestations are diffuse or multiple patchy consolidations or nodules and masses in both lungs with or without bilateral pleural effusions, the diagnostic considerations should include ENKL. CT-guided core needle biopsy is helpful for diagnosis in patients with mass shadows in the lung and especially in the patients who cannot tolerate surgical lung biopsy and tissue sampling is essential to establish a diagnosis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, EBV = Epstein–Barr virus, ENKL = extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, HPS = haemophagocytic syndrome, PET/CT18 = F-fuorodexoyglucose-positron emission tomography computed tomography.

The work supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81300250).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. xHematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009; 1:523–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au WY, Ma SY, Chim CS, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcome of mature T-cell and natural killer-cell lymphomas diagnosed according to the World Health Organization classification scheme: a single center experience of 10 years. Ann Oncol 2005; 16:206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Health Organization classification of malignant lymphomas in Japan: incidence of recently recognized entities. Lymphoma Study Group of Japanese Pathologists. Pathol Int. 2000; 50:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CY, Yao M, Tang JL, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities of 200 Chinese patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Taiwan: with special reference to T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2004; 15:1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laohaburanakit P, Hardin KA. NK/T cell lymphoma of the lung: a case report and review of literature. Thorax 2006; 61:267–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee BH, Kim SY, Kim MY, et al. CT of nasal-type T/NK cell lymphoma in the lung. J Thorac Imaging 2006; 21:37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oshima K, Tanino Y, Sato S, et al. Primary pulmonary extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: nasal type with multiple nodules. Eur Respir J 2012; 40:795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morovic A, Aurer I, Dotlic S, et al. NK cell lymphoma, nasal type, with massive lung involvement: a case report. J Hematopathol 2010; 3:19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki R. Pathogenesis and treatment of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol 2014; 51:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou XX, Lu K, Geng LY, et al. Utility of PET/CT in the diagnosis and staging of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014; 93:e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Au WY, Pang A, Choy C, et al. Quantification of circulating Epstein-Barrvirus (EBV) DNA in the diagnosis and monitoring of natural killer cell and EBV-positive lymphomas in immunocompetent patients. Blood 2004; 104:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki R, Yamaguchi M, Izutsu K, et al. Prospective measurement of Epstein-Barr virus-DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Blood 2011; 118:6018–6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawa K. Epstein–Barr virus-associated diseases in humans. Int J Hematol 2000; 71:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KS, Kim Y, Primack SL. Imaging of pulmonary lymphomas. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su X, Song Y, Shi Y, et al. Primary pulmonary extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma: report of one case and a brief review of the literature. Linchuang Nei Ke Za Zhi (Chinese) 2006; 23:106–109. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao MS, Cai HR, Yin HL, et al. Primary natural killer/T cell lymphoma of the lung: two cases report and clinical analysis. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi (Chinese) 2008; 31:120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi M, Kwong YL, Kim WS, et al. Phase II study of SMILE chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage IV, relapsed, or refractory extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: the NK Cell Tumor Study Group study. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:4410–4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]