Abstract

The tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) is recommended for all adults in both Canada and the United States. There are few data on the proportion of Canadian adults vaccinated with Tdap; however, anecdotal reports indicate that uptake is low. This study aimed to explore the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of Canadian health care providers (HCPs) in an attempt to identify potential barriers and facilitators to Tdap uptake. HCPs were surveyed and a geographic and practice representative sample was obtained (N =1,167). In addition, 8 focus groups and 4 interviews were conducted nationwide. Results from the survey indicate that less than half (47.5%) of all respondents reported being immunized with Tdap themselves, while 58.5% routinely offer Tdap to their adult patients. Knowledge scores were relatively low (63.2% correct answers). The best predictor of following the adult Tdap immunization guidelines was awareness of and agreement with those recommendations. Respondents who were aware of the recommendations were more likely to think that Tdap is safe and effective, that their patients are at significant risk of getting pertussis, and to feel that they have sufficient information (p < 0.0001 for each statement). Focus group data supported the survey results and indicated that there are substantial gaps in knowledge of pertussis and Tdap among Canadian HCPs. Lack of public knowledge about adult immunization, lack of immunization registries, a costing differential between Td and Tdap, workload required to deliver the vaccine, and vaccine hesitancy were identified as barriers to compliance with the national recommendations for universal adult immunization, and suggestions were provided to better translate recommendations to front-line practitioners.

Keywords: adult immunization, attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, pertussis, pertussis vaccine, Tdap, vaccine coverage

Introduction

Despite widespread childhood vaccination against Bordetella pertussis, pertussis (whooping cough) continues to be an important cause of morbidity in pediatric, adolescent, and adult populations in Canada and elsewhere. Universal immunization with 5 doses of pertussis-containing vaccine before school entry dramatically reduced the incidence of pertussis in preschool-aged children but shifted the burden of pertussis disease to adolescents and adults. The occurrence of B. pertussis infection among adolescents and adults reflects waning immunity in these populations, improvements in diagnostic methods, and better recognition of pertussis- like syndromes by health care providers (HCPs).1-7 Adults, who may not present with classical whooping cough symptoms and may go undiagnosed, play an important role in the transmission of infection to infants who are at highest risk of severe disease.8-13

Currently, the Canadian National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommends a dose of pertussis vaccine be given during adolescence and that all adults who have not had a dose of acellular pertussis should receive a single dose.6 All provinces and territories administer a dose of the adolescent/adult formulation of tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) to adolescents; most do so in school-based programs, with high levels of vaccine coverage in most jurisdictions.14 In contrast, as with most adult vaccination programs, there is great variability among the provinces/territories regarding adult Tdap vaccination programs. There has been little assessment of the implementation of the adult Tdap vaccination strategy in Canada. Anecdotal reports indicate that uptake of Tdap is very low.11

This study aimed to explore the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of Canadian HCPs regarding pertussis and pertussis vaccination. The goal of the study was to identify potential barriers and facilitators of Tdap uptake in order to improve adult Tdap vaccination programs.

Results

Environmental scan

Interviews were conducted with public health officials in all 10 provinces and 3 territories. Seven of the 10 provinces and all 3 territories followed the NACI guidelines in recommending that all adults receive a single dose of Tdap vaccine and provided publicly funded Tdap vaccination for adults (Table 1). Implementation and education strategies in jurisdictions that funded Tdap vaccination consisted mostly of providing information in brochures and on government websites. Additional targeting to immunize parents of newborns and provide information about cocooning to prevent pertussis in young infants was undertaken in 3 provinces. Most respondents reported that no surveillance program to record vaccine receipt in adults was in place and therefore Tdap coverage rates in their jurisdictions were not known.

Table 1.

Canadian provincial and territorial adult Tdap vaccination programs: funding and promotion as of 2012

| Adult Tdap vaccination |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Single dose | Funding | Promotion |

| Yukon | Yes | Full | Considering multistrategy program involving front-line provider education, roll-out of Tdap program (e.g., at flu clinics, visits to parents of newborns) |

| Nunavut | Yes | Full | No |

| North west Territories | Yes | Full | Unclear |

| British Columbia | No | Partial | Vaccination schedule information posted on government website; information provided by front-line staff; routine immunization by HCPs of children <12 years and residents in outbreak areas |

| Alberta | No | Partial | Vaccination schedule provided to HCPs; information program delivered by nurses under development; considering cocooning strategy |

| Saskatchewan | Yes | Full | Vaccination schedule information posted on government website; cocooning strategy for new mothers, health workers, all adults |

| Manitoba | Yes | Full | Vaccination information posted on government website; information fact sheets available |

| Ontario | Yes | Full | Vaccination information posted on government website; Information fact sheets available |

| Quebec | Yes | Full | No formal program; information provided to HCPs |

| New Brunswick | Yes | Full | Educational/information resources available in hard copy and on-line being developed |

| Nova Scotia | Yes | Full | Information directed at adults and parents of newborns, educational and informational material; campaign targeted to general adult population and families with newborns, family doctors, family resource centers, public health offices, maternity hospitals; Information available in hard copy and on-line |

| Prince Edward Island | Yes | Full | Tdap vaccination free for all adults and at-risk individuals; cocooning program |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | No | No | No |

Participants (survey)

A total of 1,167 health care providers completed the survey. Of these, 42.8% were family physicians, 5.6 % were internists, 34.3% were pharmacists, and 17.3% were nurses (Table 2). The majority of respondents (83.9%) practised in an urban/suburban setting. Ninety-three percent of physicians, 41% of pharmacists and 54% of nurses provided direct patient care at least 75% of the time. Less than one-half (47.5%) of all respondents reported being immunized with Tdap themselves, while 58.5% stated that they routinely offer Tdap to their adult patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of respondents to the national survey of health care providers (HCP)

| Characteristic | Nurses | Family Physicians | Internists | Pharmacists | All HCPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession; n (%) | 202 (17.3) | 500 (42.8) | 65 (5.6) | 400 (34.3) | 1,167 (100) |

| Female sex % | 186 (92.1) | 170 (34.0) | 16 (24.6) | 199 (49.8) | 571 (48.9) |

| Age | |||||

| ≤24 | 3 (1.5) | — | — | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) |

| 25–34 | 53 (26.2) | 45 (9.0) | 2 (3.1) | 104 (26.0) | 204 (17.5) |

| 35–44 | 54 (26.7) | 118 (23.6) | 24 (36.9) | 164 (41.0) | 360 (30.8) |

| 45–54 | 57 (28.2) | 210 (42.0) | 25 (38.5) | 99 (24.8) | 391 (33.5) |

| ≥55 | 35 (17.3) | 127 (25.4) | 14 (21.5) | 32 (8.0) | 208 (17.8) |

| Province | |||||

| British Columbia | 41 (20.3) | 81 (16.2) | 5 (7.7) | 53 (13.1) | 180 (15.4) |

| Alberta | 35 (17.3) | 56 (11.2) | 7 (10.8) | 45 (11.3) | 143 (12.3) |

| Saskatchewan | 12 (5.9) | 18 (3.6) | 1 (1.5) | 19 (4.8) | 50 (4.3) |

| Manitoba | 12 (5.9) | 18 (3.6) | 5 (7.7) | 17 (4.3) | 52 (4.5) |

| Ontario | 60 (29.7) | 168 (33.6) | 25 (38.5) | 125 (31.3) | 378 (32.4) |

| Quebec | 16 (7.9) | 123 (24.6) | 17 (26.2) | 82 (20.5) | 238 (20.4) |

| New Brunswick | 10 (5.0) | 8 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | 23 (5.8) | 42 (3.6) |

| Nova Scotia | 10 (5.0) | 18 (3.6) | 3 (4.6) | 22 (5.5) | 53 (4.5) |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | — | 2 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 5 (2.5) | 8 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | 12 (3.0) | 26 (2.2) |

| Nature of practice | |||||

| Urban | 116 (57.4) | 285 (57.0) | 38 (58.5) | 219 (54.8) | 658 (56.4) |

| Suburban | 46 (22.8) | 132 (26.4) | 18 (27.7) | 125 (31.3) | 321 (27.5) |

| Rural | 40 (19.8) | 83 (16.6) | 9 (13.8) | 53 (13.3) | 185 (15.9) |

| Involved in direct patient care >75% | 109 (54.0) | 469 (93.8) | 56 (86.2) | 164 (41.0) | 798 (68.4) |

| Number of years providing vaccines; mean (SD) | 9.7 (7.3) | 19.5 (8.9) | 15.9 (4.5) | 6.1 (7.5) | 15.4 (9.9) |

| Vaccines administered to adults/month | |||||

| None | 13 (7.1) | 5 (1.0) | 3 (4.7) | 14 (4.2) | 35 (3.3) |

| 1–5 | 61 (33.5) | 46 (9.3) | 19 (29.7) | 106 (32.1) | 232 (21.7) |

| 6–10 | 38 (20.9) | 101 (20.4) | 17 (26.6) | 95 (28.8) | 251 (23.4) |

| 11–20 | 32 (17.6) | 165 (33.3) | 14 (21.9) | 82 (24.8) | 293 (27.4) |

| 21–50 | 26 (14.3) | 131 (26.5) | 6 (9.4) | 25 (7.6) | 188 (17.6) |

| >50 | 12 (6.6) | 47 (9.5) | 5 (7.8) | 8 (2.4) | 72 (6.7) |

| Routinely offer Tdap to adults | 70 (47.6) | 305 (69.8) | 12 (50.0) | 28 (27.5) | 415 (58.5) |

| Immunized with Tdap themselves | 97 (48.0) | 222 (44.4) | 35 (53.8) | 200 (50.0) | 554 (47.5) |

| Live with someone at higher risk of pertussis | 68 (33.7) | 183 (36.6) | 29 (44.6) | 160 (40.0) | 440 (37.7) |

Knowledge

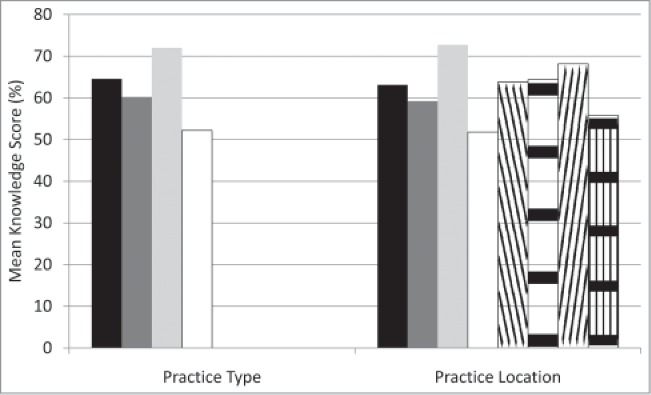

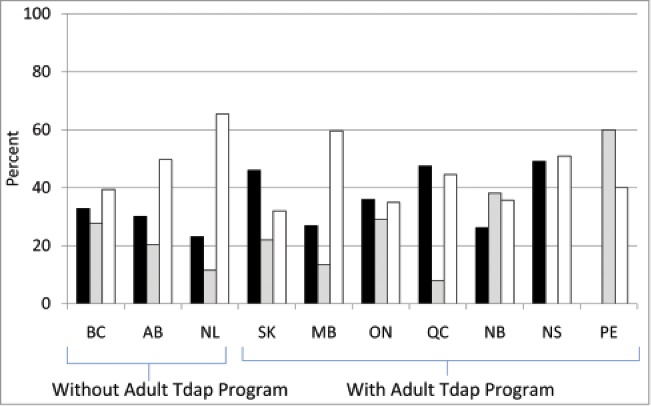

The mean proportion of correct responses to knowledge questions was 63.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) 61.8–64.6) correct answers out of a total of 9 knowledge questions (Fig. 1). Physicians had the highest knowledge score, followed by nurses and then pharmacists (Table 3; p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in knowledge between urban/suburban and rural practitioners or for urban/suburban versus rural practitioners by profession (Fig. 1). Awareness of recommendations for Tdap vaccination and whether the province had a program for universal adult Tdap vaccination tended to be higher in provinces with universal programs than in provinces without programs (Fig. 2). Higher knowledge scores were associated with increased number of vaccinations administered per month by the practitioner (p < 0.001), with a greater likelihood of being aware of (p < 0.001) and agreeing with (p< 0.001) the NACI Tdap recommendations, and planning to receive or having received Tdap themselves (p < 0.001). Higher knowledge scores were also associated with trusting the scientific information about Tdap (p = 0.01), with either agreeing or disagreeing that the vaccine is effective (p < 0.001), and with feeling that they have sufficient information in order to make a recommendation to their patients about Tdap vaccination (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Mean knowledge scores (% correct response) of 9 questions by practice type and by practice location. In practice type, the black bar depicts all health care providers, the dark gray bar depicts nurses, the light gray bar physicians (general practitioners and internists), and the white bar pharmacists. For practice location the black bar depicts urban/suburban practitioners, the dark gray bar urban/suburban nurses, the light gray bar urban/suburban physicians, the white bar urban/suburban pharmacists, the bar cross-hatched down to the right depicts rural practitioners, the bar cross-hatched horizontaly rural nurses, cross-hatched up to the right rural physicians, and cross-hatched vertically rural pharmacists.

Table 3.

Knowledge of pertussis, Tdap vaccine, and programs, by health care providers

| Percent Correct Answer |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synopsis of Knowledge Questions | Correct Answer | Nurses | Physicians | Pharmacists | p value |

| Infants <1 mo of age are immunized against pertussis | False | 61.4 | 72.6 | 40.3 | <0.01 |

| Only infants < 6 mo of age are at risk of pertussis complications | False | 81.7 | 82.7 | 69.3 | <0.01 |

| Duration of immunity post-childhood vaccination leaves adolescents and adults susceptible to pertussis | True | 72.8 | 90.4 | 72.5 | <0.01 |

| Adults can get pertussis even if they had it as a child | True | 66.8 | 75.6 | 60.0 | <0.01 |

| Pertussis only transmitted during paroxysmal stage | False | 50.5 | 67.1 | 36.8 | <0.01 |

| Adults usually present without classical pertussis symptoms | True | 37.1 | 58.9 | 40.8 | <0.01 |

| There are increased adverse events from adults receiving Tdap if they received a Td within 2 years | False | 32.7 | 44.6 | 31.3 | <0.01 |

| Tdap can be administered at the same time as other vaccines | True | 52.0 | 69.4 | 48.8 | <0.01 |

| Outbreaks of pertussis continue to occur in Canada | True | 87.1 | 86.5 | 70.5 | <0.01 |

| Aware of NACI guidelines for Tdap in adults | — | 75.7 | 77.7 | 54.5 | <0.01 |

Figure 2.

Health care provider awareness of provincially funded programs for vaccination of adults with Tdap. Black bars depict correct responses, gray bars incorrect responses, and white bars those who responded that they did not know the answer to the question “In my province, the Tdap vaccine is publicly funded (free of charge) for adults.”

Attitudes and beliefs

Attitudes and beliefs were, for the most part, similar among nurses, physicians, and pharmacists (Table 4). Physicians tended to believe more in the safety and effectiveness of Tdap than nurses or pharmacists and were less likely to think it important to discuss the risks and benefits of the disease and vaccine with their patients. Pharmacists were less likely to feel that it was important to them to administer Tdap and that administering Tdap was the right thing to do, more likely to feel that they don't have enough information about Tdap, to be confused about the NACI recommendations, and less likely to agree with the NACI recommendations. Nurses were least likely to cite convenience as a factor in whether or not they administered Tdap and most likely to feel it was important to discuss the risks and benefits of Tdap vaccine and pertussis infection. Pharmacists were most likely and physicians least likely to be comfortable with and support administration of Tdap by pharmacists. Respondents who were aware of the NACI recommendations were more likely to think that Tdap is safe and effective, that their patients were at significant risk of getting pertussis, and to feel that they had sufficient information (p<0.0001 for each statement).

Table 4.

Attitudes and beliefs about pertussis, Tdap vaccine, and programs by health care providers

| Percent |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synopsis of statements | Agreement | Nurses | Physicians | Pharmacists | p value |

| Pertussis serious threat to adults | Strongly agree/agree | 69.8 | 68.3 | 67.5 | 0.74 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20.3 | 21.1 | 23.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 9.9 | 10.6 | 8.8 | ||

| Pertussis serious threat to young infants | Strongly agree/agree | 93.6 | 90.3 | 87.0 | 0.03 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2.0 | 6.4 | 8.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 4.5 | 3.4 | 4.3 | ||

| Pertussis so rare, vaccination no longer needed | Strongly agree/agree | 5.4 | 11.0 | 13.8 | 0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14.9 | 16.6 | 19.3 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 79.7 | 72.4 | 67.0 | ||

| Tdap is effective in preventing pertussis | Strongly agree/agree | 62.4 | 81.9 | 69.0 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 33.2 | 14.7 | 28.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 4.5 | 3.4 | 2.5 | ||

| Providing Tdap to adults is important to me | Strongly agree/agree | 62.4 | 66.9 | 54.5 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29.2 | 27.3 | 37.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 8.4 | 5.8 | 8.0 | ||

| I want to protect my patients from getting pertussis | Strongly agree/agree | 87.6 | 87.8 | 88.3 | 0.96 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 7.9 | 8.5 | 8.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 | ||

| Providing adult Tdap is the right thing to do | Strongly agree/agree | 70.8 | 77.3 | 66.3 | 0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24.3 | 18.9 | 28.3 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 5.0 | 3.8 | 5.5 | ||

| I can easily provide Tdap if I want to | Strongly agree/agree | 45.5 | 72.2 | 40.0 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 32.2 | 16.1 | 34.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 22.3 | 11.7 | 26.0 | ||

| Convenience is a factor in my decision to provide Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 25.2 | 48.0 | 37.5 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 40.1 | 34.5 | 44.3 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 34.7 | 17.5 | 18.3 | ||

| I don't have time to provide Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 14.4 | 17.3 | 20.5 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 31.2 | 23.4 | 39.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 54.5 | 59.3 | 39.8 | ||

| I trust the NACI Tdap recommendations | Strongly agree/agree | 80.7 | 81.4 | 79.5 | 0.73 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 16.3 | 17.0 | 18.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 3.0 | 1.6 | 2.5 | ||

| Some of my patients are at significant risk of pertussis because they have not received Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 49.5 | 63.9 | 47.8 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 40.1 | 28.5 | 40.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 10.4 | 7.6 | 11.8 | ||

| I do not trust current scientific knowledge about Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 4.0 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 0.11 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29.7 | 23.7 | 28.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 66.3 | 69.2 | 63.5 | ||

| Tdap is safe for adults | Strongly agree/agree | 62.9 | 76.8 | 66.8 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 36.1 | 22.8 | 32.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | ||

| I am confused about whether I should provide Tdap to patients | Strongly agree/agree | 25.7 | 25.7 | 35.8 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 32.7 | 26.4 | 35.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 41.6 | 48.0 | 28.5 | ||

| Public health officials don't provide enough information about Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 49.5 | 52.4 | 59.0 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24.3 | 23.2 | 26.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 26.2 | 24.4 | 14.5 | ||

| I don't have enough information to decide whether to provide Tdap to my patients | Strongly agree/agree | 34.2 | 30.3 | 50.5 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25.2 | 21.8 | 28.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 40.6 | 48.0 | 21.5 | ||

| It is important to inform patients about the benefits/risks of Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 88.1 | 81.4 | 86.0 | 0.09 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 9.9 | 16.8 | 13.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | ||

| It is important to inform patients about the risks of pertussis | Strongly agree/agree | 90.6 | 79.8 | 83.3 | 0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 8.4 | 17.9 | 13.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.0 | 2.3 | 3.3 | ||

| It is important to comply with the NACI recommendations on Tdap | Strongly agree/agree | 83.7 | 82.1 | 83.8 | 0.11 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14.9 | 17.7 | 14.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.5 | 0.2 | 1.5 | ||

| NACI guidelines on Tdap recommendations in adults are not promoted adequately | Strongly agree/agree | 66.8 | 70.1 | 67.0 | 0.34 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 23.3 | 21.1 | 26.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 9.9 | 8.8 | 7.0 | ||

| NACI guidelines on Tdap recommendations in adults are confusing | Strongly agree/agree | 22.8 | 31.7 | 26.0 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 49.5 | 42.1 | 58.8 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 27.7 | 26.2 | 15.3 | ||

| Healthcare workers should receive Tdap vaccine in order to protect themselves and their patients | Strongly agree/agree | 71.3 | 80.0 | 74.5 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 21.8 | 18.9 | 23.3 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 6.9 | 1.1 | 2.3 | ||

| I agree with the NACI recommendation for adult Tdap vaccine | Yes | 70.8 | 74.7 | 61.0 | <0.01 |

| Don't know | 22.3 | 21.9 | 33.3 | ||

| No | 6.9 | 3.4 | 5.8 | ||

| I feel comfortable receiving vaccines from a pharmacist | Strongly agree/agree | 48.5 | 35.8 | 78.8 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11.9 | 19.5 | 11.0 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 39.6 | 44.8 | 10.3 | ||

| I support pharmacists providing vaccines to adults | Strongly agree/agree | 57.4 | 38.9 | 82.3 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 10.4 | 15.4 | 8.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 32.2 | 45.7 | 9.3 | ||

| I would refer my patients to pharmacists for vaccine administration | Strongly agree/agree | 40.1 | 26.5 | 72.0 | <0.01 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 15.3 | 17.5 | 18.5 | ||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 44.6 | 56.0 | 9.5 | ||

In the univariate analysis, agreeing that pertussis is a threat to adults and having patients at risk for pertussis were associated with an increased likelihood of routinely administering Tdap to adults as per NACI recommendations (Table 5). Counter intuitively, the attitude that pertussis is rare and vaccination is no longer needed, not having time to administer Tdap, and confusion with the recommendations were also positively associated both with being more likely to routinely offer Tdap to patients as well as with not offering Tdap. Neither agreeing nor disagreeing with the attitudinal statements was most correlated with not routinely offering Tdap to patients.

Table 5.

Predictors of a health care provider routinely offering (✓) or not offering (x) all adult patients the Tdap vaccine according to provincial guidelines, in univariate analysis

| Synopsis of statements | Strongly agree/agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree/strongly disagree | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pertussis serious threat to adults | ✓ | 0.01 | ||

| Pertussis so rare, vaccination no longer needed | ✓ | x | ✓ | <0.01 |

| Tdap is effective in preventing pertussis | x | <0.01 | ||

| Providing Tdap to adults is important to me | x | x | <0.01 | |

| I want to protect my patients from getting pertussis | x | <0.01 | ||

| Providing adult Tdap is the right thing to do | x | <0.01 | ||

| I can easily provide Tdap if I want to | x | <0.01 | ||

| I don't have time to provide Tdap | ✓ | x | ✓ | <0.01 |

| I trust the NACI Tdap recommendations | x | <0.01 | ||

| Some of my patients are at significant risk of pertussis because they have not received Tdap | ✓ | <0.01 | ||

| Tdap is safe for adults | x | <0.01 | ||

| I am confused about whether I should provide Tdap to patients | ✓ | x | ✓ | <0.01 |

| Public health officials don't provide enough information about Tdap | ✓ | ✓ | <0.01 | |

| I don't have enough information to decide whether to provide Tdap to my patients | ✓ | ✓ | <0.01 | |

| It is important to inform patients about the benefits/risks of Tdap* | 0.01 | |||

| It is important to inform people about the risks of pertussis* | <0.01 | |||

| NACI guidelines on Tdap recommendations in adults are not promoted adequately | ✓ | x | ✓ | <0.01 |

| NACI guidelines on Tdap recommendations in adults are confusing | ✓ | x | ✓ | <0.01 |

| Healthcare workers should receive Tdap vaccine in order to protect themselves and their patients | x | <0.01 | ||

| I agree with the NACI recommendation for adult Tdap vaccine | x | <0.01 | ||

| I feel comfortable receiving vaccines from a pharmacist | ✓ | ✓ | <0.01 | |

| I support pharmacists providing vaccines to adults | ✓ | ✓ | <0.01 | |

| I would refer my patients to pharmacists for vaccine administration | ✓ | ✓ | <0.01 |

this item was significant in the univariate model but the direction of the effect was not discernible

In the multivariate analysis, providers who disagreed that they were confused about whether they should offer Tdap to their patients, who disagreed that they did not have enough information to decide whether or not to provide Tdap to their patients, who disagreed that they would feel comfortable receiving vaccines from a pharmacists, and who neither agreed nor disagreed that they would refer their patients to pharmacist for vaccine administration were more likely to routinely offer all patients Tdap according to the NACI guidelines. Providers who disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed that providing Tdap to adults was important to them, and who disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed that they could easily provide Tdap if they wanted to were less likely to routinely offer Tdap according to the NACI guidelines.

Qualitative stage (focus groups)

A total of 45 health care providers participated in the focus groups/interviews. Of these, 16 (36%) were family physicians, 12 (27%) pharmacists, 11 (24%) nurses, 2 (4%) general internists, and 2 (4%) pediatricians. One public health physician and 1 emergency room physician were also interviewed. Themes that emerged from the focus groups were both practice facilitators and practice barriers to providing Tdap to adults. HCPs preferences regarding an intervention plan to promote the Tdap vaccine were described.

Practice facilitators

Participants identified collaboration, access to an electronic database, and advocacy for and education about vaccination as facilitators to Tdap uptake among adults (Table 6). Many participants stated that, along with offering Tdap through family physicians' offices and public health clinics, additional vaccination locations such as pharmacies, travel and walk-in clinics, and other special clinics should be provided, and that Tdap should be administered during other vaccination campaigns. The majority of participants felt that tracking of adult immunization and record keeping is poor among adults and that an electronic database would help to decrease some of the confusion about adult vaccine recommendations, improve patient safety, and enhance interprofessional collaboration. Finally, the majority of participants believed that HCPs need to actively advocate and provide education to patients to improve adult vaccination uptake. Many HCPs believed that they were trusted by the public and it was their responsibility to provide vaccines and that they must remind people of what vaccines they are eligible for and when they should receive them. Many believed that they have an obligation to keep informed of the NACI guidelines and to discuss these openly with their patients. Education was also deemed to be necessary in order to improve trust in vaccines. Some participants stated that opportunities for teaching need to take place during routine physical examination visits, through travel clinics, and by contact with high-risk clients.

Table 6.

Summary of practice facilitators and barriers identified during focus groups of health care providers

| Facilitators | Collaborative efforts among HCPs: improving accessibility | |

| “I think the more people you can get on board to administer the Tdap vaccine, the easier access the patient will have to get it. They can book an appointment, or they can get it as a part of their routine visit, if the pharmacy starts giving it when they go pick up their monthly medications they could have it administered there, so it's not hours of waiting … .” (PEI) | ||

| “I would as long as they (pharmacists) got the appropriate training by a credited source.” (BC) | ||

| “With training for pharmacists, it's a good idea” (QC) | ||

| “So first of all there has to be an availability of the vaccine to supply the demand” (PEI) | ||

| Electronic databases and the importance of immunization tracking | ||

| “If there was an electronic record where you could go in and say: Oh look, their vaccines aren't up to date. Then it could be something you could bring up.” (PEI) | ||

| “In our clinic we are very up to date with our MMR for instance. Our RN is very good; he goes through the system and highlights the patients for each physician who is in need of vaccinations, so it is very proactive. I think with our new Pharmanet, with us giving some injections, there is now an electronic record that follows patients so that people could actually be followed through the electronic registry by their physicians as to what their immunization statuses are.” (BC) | ||

| “When I was a child in school I got all my shots so I am ok.” (ON) | ||

| “For routine immunizations adults assume it is done.” (NS) | ||

| Advocacy and education | ||

| “I think physicians need to have a role in advocacy. Their opinions to their patients are highly valued. Their recommendations sway people who are on the fence.” (QC) | ||

| “I think appropriate care would say that it's my responsibility to be aware of disease preventable adult vaccinations, with respect to travel for patients, and with respect to the Canadian and provincial recommendations for immunization “I think a lot of times if we have a good talk with the patient, they've been our patient for 10 y and they trust us and we haven't killed them yet- they often make the leap and get the vaccine-because they see us as a trusted authority figure with their best interest at heart.” (ON) | ||

| “In case of my clinic or during my physical I make it a point when I am doing physicals to ask them about immunizations.” (SK) | ||

| “I identify high risk people, like new mothers.” (NS) | ||

| Barriers | ||

| Current fee structure | ||

| “They're expensive so one of the big barriers I see is people will say: Oh yeah I could get a tetanus pertussis but it will cost me $30.00.” (BC). | ||

| “Provincially a tetanus is provided free of charge, and most people will opt for that because of the cost.” (BC). | ||

| Public/provider lack of knowledge and engagement with the Tdap vaccine | ||

| “Basically my observation on adult vaccinations is that there is a whole lot of room to go with vaccines; they're not aware of when to get boosters.” (ON) | ||

| “We need to be doing boosters … . But people don't care.” (ON) | ||

| “Tetanus, diphtheria, and what's the one on the end?” (NS) | ||

| “It has multiple tetanus, diphtheria, umm I'm not sure what's the other part, I'd have to look them up, I'm not sure what the other stand for. I'm not sure how frequently it's given, and what it is given for.” (BC) | ||

| Vaccine hesitancy | ||

| “I had a lot of people at the Community Pharmacy who would come in and ask: “Is this vaccine bad?” And I'm like well, have you ever seen somebody with this condition? I mean, you have to explain, but it's annoying, because they're more willing to agree with the easy information source rather than the right information” (SK) | ||

| “Ok, any kind of medical treatment is a personal choice, but from my standpoint there is a lot of anti-vaccine information, and I don't think that Health Canada or practitioners are doing a great job in terms of countering the myths with correct information.” (SK) | ||

| Workload | ||

| “I think that Public Health people are committed to disseminate vaccine information to the public. I am neither paid, nor do I have time to pull someone aside to say ‘Hey have you heard about this vaccine?’(PEI) | ||

| “Physicians' offices are the default primary care places for vaccines to be done. But it's inappropriate because it costs millions and millions of dollars every year; it's a waste…” (NS) | ||

| “So in writing, yes, we support the recommendations, but we're not trying to find these people, probably the vaccine, it's a catch 22. It's passive. We're not actively seeking out people to give it.” (SK). | ||

Practice barriers

Participants identified numerous practice barriers related to providing the adult Tdap vaccine to the public, including the fee structure, public and provider lack of knowledge of the Tdap vaccine, vaccine hesitancy, and workload (Table 6). In provinces where adult Tdap was not funded, participants raised a concern that patients were deterred by the Tdap vaccine cost and opted to receive the provincially funded Td vaccine instead. There was a consensus that the public is more likely to receive the vaccine if it is funded as the vaccine is then perceived to be important and supported politically. However, in some cases, HCPs did not support public funding for Tdap, citing limited budgets for the full range of vaccines and, in some cases, categorizing Tdap as a travel vaccine. Some focus group participants stated that they had little knowledge about the pertussis component of the vaccine and lacked knowledge of NACI guidelines for the Tdap vaccine. Many HCPs were aware of pertussis outbreaks in certain cohorts and understood the seriousness of the disease for infants. Some alluded to the fact that vaccinating the younger adult population may be of some benefit. Many HCPs felt that patients lack adequate knowledge about Tdap and the timing of a booster dose. Lack of knowledge was linked to lack of caring about the issue; when knowledge is limited, motivation to receive the vaccine is low. In contrast to pertussis, HCPs perceive public awareness about tetanus and tetanus vaccine to be high. Some providers feel that patients need to be better informed and believe the patients make irrational decisions based on anecdotal evidence and emotional responses to media reports. Others believe that Public Health and HCPs do not dispel the myths of the antivaccination movement and suggest that more should be done in this regard. Some HCPs themselves were skeptical about the efficacy and safety of Tdap. Some mistrusted “Big Pharma” or industry recommendations and believed that adult vaccination guidelines are biased opinions by “so called experts.” Finally, some physicians believe that they are not paid or trained sufficiently to deliver vaccinations. Some insist that it is not their job and that it is more economical for other HCPs to administer the vaccine. While HCPs value advocacy and education, some reported that, due to workload issues and time constraints, they do not discuss adult vaccination unless the patient initiates the discussion.

Strategies for Tdap promotion: An intervention plan

HCPs generally feel that the NACI guidelines for Tdap in adults are not promoted adequately. Most participants stated that they have not noticed any advertising and they generally feel that the public is not aware of Tdap. Furthermore, they believe that a national campaign to improve uptake of Tdap should be done both through HCPs and directly to the public: “Health care professionals need to be educated first of all and they could obviously use that information in their practices, but I think public awareness is important, the patients themselves can request the immunization, both ways.” Participants described several elements of an effective, regionally viable public adult Tdap vaccination program (Table 7).

Table 7.

Interventions proposed by focus group participants to improve Tdap uptake among adults

| Message to convey | Tdap vaccine is effective in protecting the person who is vaccinated as well as others around him/her | |

| Tdap vaccine protects the spread of disease | ||

| Information about whooping cough including incidence, prevalence, severity, and consequences. | ||

| Information about the Tdap vaccine (necessity of the vaccine, effectiveness, and safety profile) | ||

| Information about availability, process, and cost | ||

| Benefits of vaccine protection | ||

| Responsibility to society and respect for others | ||

| Message should be tailored to the target audience | ||

| How to communicate the message | ||

| In a serious way: using facts and an informational tone to educate the population and increase the credibility of the message | ||

| An emotional tone to get the attention of Canadians without creating panic | ||

| Fear and humor less appropriate | ||

| Visuals | ||

| Images involving emotion | ||

| Images of children being affected (negative and dark images showing the consequences of the disease) | ||

| Spokesperson/authority figures | ||

| People related to the health industry, credible and serious: doctors, provincial and national public health officers | ||

| Famous people known and respected | ||

| Local people held in high esteem | ||

| Ordinary citizen affected by pertussis | ||

| No pharmaceutical companies or politicians | ||

Discussion

Despite national recommendations in Canada since 2003 for universal immunization of adults with Tdap6 and 7 of 10 provinces and all 3 territories having publicly funded programs at the time the surveys and focus groups were undertaken, implementation of the recommendations has been unsuccessful. Tdap vaccine coverage is thought to be low (<10 %), although accurate assessments of coverage are lacking. The most recent Canadian adult National Vaccine Coverage Survey estimates adult Tdap coverage at 6.7%; however, problems with respondents knowing whether they received Td or Tdap likely make those estimates unreliable.15 Vaccine coverage rates in adults in general are suboptimal and in need of improvement.16

In this study, we found that knowledge among HCPs about pertussis in adults and the recommendations for Tdap use in adults was generally low, and the likelihood of being immunized oneself and routinely providing Tdap to patients correlated with being aware of and agreeing with the national recommendations. Only 58.5% of the HCP respondents routinely offered Tdap to their patients; although this is low, it exceeds the 58% who had never prescribed a pertussis vaccine to an adult reported by Hoffait.17 A number of barriers to adhering to the recommendations for Tdap use were identified and potential solutions were proposed. As is the case for any vaccination program, an HCP's level of knowledge, his/her personal perspectives, and national/provincial recommendations are critical for a program's success. In our study, knowledge of pertussis and Tdap were relatively low among all HCPs, similar to the findings of Staes18 who reported that only one-half of the providers correctly answered questions about pertussis vaccine recommendations for adolescents, but different from Laserre19 who found 83% awareness of the National French vaccination guidelines. We found the level of knowledge varied by type of provider, with physicians knowing the most, followed by nurses and then pharmacists. At the time of the survey, pharmacists were not permitted to provide Tdap immunization, which might explain their lower level of knowledge. In most Canadian jurisdictions, pharmacists who wish to administer vaccines are required to undertake formal training which includes education about the specific vaccines to be provided. We anticipate that Tdap knowledge would improve among pharmacists if Tdap were added to their list of approved vaccines. We also found a strong association between knowledge and increased intention to vaccinate, similar to other studies.20 Awareness of Tdap and Tdap recommendations was also linked closely to knowledge levels and was higher in provinces/territories with publically funded adult Tdap programs. However, despite public funding, promotional activities were minimal and vaccine coverage remains low.

The best predictor of following the NACI adult Tdap immunization guidelines in the multivariate analysis was an awareness of and agreement with those recommendations. The awareness to adherence model supports the notion that in order for HCPs to comply with practice guidelines, they must first be aware of the guidelines, then intellectually agree with them, then decide to adopt them in the care that they provide, and, finally, regularly adhere to them at appropriate times.21 Therefore, our results underscore the need to increase HCPs' awareness of these recommendations through effective promotion. Our focus groups also revealed a lack of knowledge of the NACI Tdap recommendations. Some participants suggested a number of interventions for general Tdap promotion among HCPs, including having available briefing notes that outline the differences between benefits and potential risks and brochures and pamphlets that provide clear and supporting documentation about the importance of the vaccine. There is little published information evaluating strategies to increase awareness of vaccine recommendations among HCPs;22 this was evident with our participants, who focused more on strategies targeted toward the public rather than toward themselves.

Understanding the facilitators and barriers that impact the implementation of vaccination programs and uptake of national vaccine recommendations is critical in order to move best evidence to front-line practitioners. Evidence, target audience, resources, and organization-related factors must be identified in order to add strength to and support for implementation of practice recommendations and guidelines.23 In our study, lack of public knowledge about adult immunization, lack of immunization registries, a costing differential between Td and Tdap, workload required to deliver the vaccine, and vaccine hesitancy were identified as significant barriers to Tdap immunization.

Focus group participants also identified that adults generally have little knowledge about the vaccines recommended by NACI and the vaccines that they had received. This confusion is compounded by the lack of a national vaccine registry in Canada that would enable practitioners to track immunization status, including the identification of what vaccines were missed, who requires boosters, and new vaccines that are available.24 Lack of a registry also prevents HCPs from tracking immunizations when people move from one jurisdiction to another. Although provincial vaccine registries are being developed in Canada, these focus on pediatric vaccines; tracking of adults vaccines is lacking.

Cost was also identified as a barrier to improving Tdap uptake although, since most Canadian jurisdictions publicly fund adult Tdap vaccination, this barrier should not be widespread for this adult vaccine. Top,25 in her study on pertussis immunization in pediatric HCPs, noted that cost was a potential barrier to vaccine uptake and that less than one-third of respondents were willing to pay $40 for the vaccine; other studies support this observation.26-30 However, the differential cost to the provinces of using Tdap compared to Td is less than $1/dose. Participants also suggested that workload barriers such as time constraints and lack of immunization education and expertise affect Tdap uptake rates. These barriers resulted in practitioners failing to be proactive in educating and delivering the vaccine to the public. In a recent study,31 physicians identified the time commitment associated with both vaccine delivery and inventory management as their main obstacle to vaccine administration. While vaccine hesitancy was also identified by participants as being a barrier to vaccine uptake, given these other provider-specific, system-wide issues which more likely influence vaccine rates, its contribution to the current low levels of Tdap vaccination among adults may be limited.

The current study reveals that there are substantial gaps in knowledge of pertussis and Tdap among Canadian HCPs and identified barriers to compliance with the national recommendations for universal adult immunization with Tdap. The strength of this study is that it was a large, nationally representative sampling of health care practitioners involved in adult immunization. The sample included public health nurses, family physicians, internal medicine specialists, and also pharmacists who are increasingly becoming involved in the delivery of vaccine programs. An additional strength of the study is that a mixed methodology approach was used, combining the broad reach of a national survey and the in-depth discussion of focus groups.32 However, the study is limited by its “point in time” analysis; infectious disease is an ever-evolving field, and vaccine recommendations change continually to address new realities. Pertussis outbreaks continue to occur in Canada and throughout the world;33-38 as of September 2014, all provinces and territories except British Columbia have funded adult Tdap programs.39 However, there is no sense of a dramatic change in vaccine coverage.

The goal of the adult pertussis vaccination recommendations is to decrease the substantial burden of infection in adults for their own benefit as well as to potentially provide collateral benefit by decreasing the transmission of infection to young infants who suffer most of the morbidity and all of the mortality.6 The availability of a safe and effective Tdap vaccine which could be substituted for the Td vaccine seemed like an easily implemented strategy. However, compliance with the recommendation to receive a tetanus booster every 10 y is also low,40,41 and little public health resources are expended to improve compliance with this recommendation. In part this is due to a general lack of focus on adult immunization along with decreased confidence in acellular pertussis vaccines in general and Tdap specifically. Data from the recently developed baboon model of pertussis suggest that acellular pertussis vaccines are effective in preventing pertussis disease but not transmission (in contrast to whole cell vaccines that prevent both disease and transmission).42 As well, recent analysis of pertussis outbreaks in the US states of Washington34 and Wisconsin35 have suggested that the duration of protection after the adolescent Tdap booster may be as short as 3–5 years, further dampening enthusiasm for routine Tdap boosters. In Canada and the US, only a single Tdap booster in adulthood is recommended.6,43 Multiple doses of Tdap are only recommended in the US for women during every pregnancy.44 Maternal immunization is an effective strategy to prevent pertussis in infants too young to be immunized.45,46

While it is increasingly clear that improved pertussis vaccines are required, currently available vaccines are safe and effective albeit with an appparently shorter duration of protection than previously anticipated. While development of more effective vaccines with sustained efficacy is a research priority,47 it will be some time before they are available. In the interim, control of pertussis must be achieved with the currently available vaccines and their use must be optimized by better compliance with existing recommendations. The results of this study improve our understanding of the barriers to compliance with current Tdap recommendations for adult immunization and provide guidance for ways to improve vaccine coverage with Tdap until better tools are available.

Methods

Research design

We used a mixed method, sequential, explanatory design consisting of 3 distinct phases: an initial environmental scan, quantitative data collection and analysis (survey), and thirdly, qualitative data collection and analysis (focus groups).32 The rationale for this approach is that the quantitative data and their subsequent analysis provide general understanding of the research problem; the qualitative data and their analysis refine and explain the statistical results by exploring participants' views in greater depth.48 The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the IWK Health Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Environmental scan

Immunization coordinators were identified using publicly available directories of each provincial/territorial Department of Health. A request for a telephone interview was sent by email with instructions to forward the request if the recipient was not the appropriate individual. Structured telephone interviews lasting 15–30 minutes were undertaken to determine whether the province/territory followed the NACI guidelines for Tdap vaccination of adults, whether the province/territory had a Tdap program for adults, whether Tdap for adults was funded by the province/territory, and whether and how Tdap for adults was promoted. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Quantitative stage (survey)

As a pilot for development of the national survey, a Web-based self-administered questionnaire modified from previous, validated surveys was distributed to a convenience sample of 299 of the 1,250 HCP attendees at the 2010 Canadian Immunization Conference held in Quebec City. Participants were queried about their knowledge of pertussis in adults and about the funding and delivery of pertussis programs in their jurisdictions. The survey also explored the attitudes of HCPs about pertussis in adults and Tdap and the characteristics of HCPs who either did or did not adhere to the NACI recommendations. The survey was developed using the Awareness Adherence Model.21 Authors of this model propose that when HCPs comply with practice guidelines, they must first become aware of the guidelines, then intellectually agree with them, then decide to adopt them in the care they provide, and then regularly adhere to them at appropriate times. Prior to distributing the survey, the content validity of individual questions as well as the entire questionnaire was evaluated by a panel of experts comprised of infectious diseases physicians. Each item was rated using a standard content validity index with a 4-point ordinal rating scale, where 1 indicated irrelevance and 4 high relevance. Items that received a score of 3 or 4 were judged to have content validity. The content validity index for the entire instrument was the proportion of items judged to have content validity. Items that did not achieve the required minimum agreement of experts were eliminated or revised. Test-retest reliability was assessed by having 5 HCPs complete the questionnaires at 2 different points in time. A correlation co-efficient was calculated to compare the 2 sets of responses; a coefficient > 0.70 was interpreted as an indication that the questionnaire responses were consistent.

The results of the pilot survey were used as the basis for the design of the national survey. The national survey was undertaken by Leger Marketing (Montreal, QC), which maintains email addresses for 350,000 Canadian adults (150,000 in Quebec) aged 18 and older who are representative of the Canadian general population of adults and who have provided contact information to Leger for the purpose of participating in market and other research. A national, purposeful sampling of the subset of HCPs within this database was invited to participate in this study. Sampling was based on regional representation across the country, age, gender, urban and rural practice, and specialty (general practice physicians, internal medicine specialists, nurses, pharmacists). Inclusion criteria were being in practice for a minimum of 3 years, responsibility for immunization delivery and/or patient consultation concerning vaccines in his/her province or territory, internet or telephone access, and willingness/ability to complete the interview. Exclusion criteria were failure to provide informed consent, inability to complete the interview or the conference web-based questionnaire, or prior participation in the pilot survey. Participants received an email invitation to the survey outlining the purpose of the study, its voluntary nature, and the time commitment involved. The cover information letter was formatted to reflect what the web-panel members were used to seeing. Consent to participate was implied by completion of the web-based survey.

A sample size of 500 family physicians and 400 pharmacists was calculated to provide an acceptable precision (95% CI around the point estimate) of ±5 %; a sample size of 100 internal medicine specialists and 200 nurses was calculated to provide an acceptable precision of ±5–10% for each practitioner type. Point estimates with 95% CIs were calculated. The first level of analysis comprised a review of the descriptive, summative statistics for trends in the data. The second level of analysis involved tests of association. Data were divided by HCP's profession (physician, nurse, pharmacist) and then by professions and locale (province/territory). Tests of association compared the HCP's profession and locale to the awareness of and agreement with the NACI recommendations and to mean knowledge scores of Tdap vaccine and pertussis. In general, continuous variables were presented by summary statistics (i.e., mean and standard error) and the categorical variables by frequency distributions (i.e., frequency counts, percentages, and their 2-sided 95% exact binomial confidence intervals). Differences in survey responses between groups of HCPs were assessed using Fisher's exact tests. For continuous variables, logistic regression was used. Overall knowledge scores were compared using t-tests. Associations between attitude questions, behavioral responses, and demographics were estimated using ordinal logistic regression or Fisher's exact tests. Logistic regression was used to predict attitudinal responses and the likelihood of the HCP routinely offering Tdap to his/her patients. Attitudinal responses were used in a backward elimination stepwise procedure to develop a multiple regression model. Those predictor variables remaining at the termination of the stepwise procedure were summarized and p-values indicated. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Qualitative stage (focus groups)

Focus groups were administered by Leger Marketing in multiple locations across Canada using a semistructured facilitation guide. Six traditional face-to-face focus groups, 2 “virtual,” web-based focus groups, and 4 one-on-one interviews were undertaken. Regional representation was sought with a balance of large and small urban areas, suburban, and rural practices. Traditional focus groups were done in Prince Edward Island (Charlottetown), British Columbia (Vancouver), Ontario (Toronto and Sudbury), Quebec (Montreal), and Saskatchewan (Regina). Virtual focus groups included HCPs from Ontario, Saskatchewan, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta. One-on-one interviews included physicians from Nova Scotia, Ontario, and British Columbia. HCPs invited to participate in the focus groups included physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Inclusion criteria for participation included being an HCP who routinely provides immunizations or advice about immunization to his/her patients and in practice for a minimum of 3 y. HCPs included nurses, pharmacists, and physicians (including general practitioners, internists, and emergency room physicians). A maximum quota of 2 pharmacists and one physician per group was imposed.

All focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. A debriefing with the moderator team took place immediately following the focus group. Data collection and analysis were concurrent.50 Data were examined using thematic analysis51 as described by Aronson.52 Initially, the data were collected via audio-tapes and transcribed. Using the N9 version of the NUD*IST software (Sage Publications Ltd, London, UK), transcripts were then labeled and categorized according to similarities and related patterns as well as differences, followed by combining and cataloguing similar patterns into subthemes. Responses that did not fit with any of the identified themes were discussed separately. The data were searched specifically for barriers and facilitators of Tdap uptake. Two investigators coded the data, and consensus was achieved through discussion in regards to the themes and subthemes, using literature to support the themes identified in the study. Field notes were also taken in addition to the recordings in order to document impressions or interesting ideas. Focus groups were continued until saturation (no additional themes identified) was achieved.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

SH, JL, and SM serve on ad hoc scientific advisory boards of vaccine manufacturers including GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Sanofi Pasteur Ltd. They hold grants and contracts from vaccine manufacturers to conduct vaccine-related clinical trials and other studies. BH, DM, and DM-C have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Bruce Smith for his assistance with the statistical analysis and Kristine Webber for her assistance with the thematic analysis of the focus groups.

Funding

This study was funded by unrestricted research grants from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Sanofi Pasteur Ltd. The funders played no role in the collection or analysis of the data.

References

- 1.Guris D, Strebel P, Bardenheir B, Brennan M, Tachdjian R, Finch E, Wharton M, Livengood JR. Changing epidemiology of pertussis in the United States: increasing reported incidence among adolescents and adults, 1990–1996. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:230-7; PMID:10064232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentsi-Enchill AD, Halperin SA, Scott J, MacIsaac K, Duclos P. Estimates of the effectiveness of a whole-cell pertussis vaccine from an outbreak in an immunized population. Vaccine. 1997; 15:301-6; PMID:9139490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Serres G, Shadmani R, Duvall B, Boulianne N, Dery P, Douville F, Rochette L, Halperin SA. Morbidity of pertussis in adolescents and adults. J Infect Dis. 2000; 182:174-9; PMID:10882595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skowronski DM, De Serres G, MacDonald D, Wu W, Shaw C, MacNabb J, Champagne S, Patrick DM, Halperin SA. The changing age and seasonal profile of pertussis in Canada. J Infect Dis. 2002; 185:1448-53; PMID:11992280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control . Pertussis–United States, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005; 54:1283-6; PMID:16371944 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Advisory Committee on Immunization . Prevention of pertussis in adolescents and adults. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2003; 29:1-9; PMID:14526692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendelboe AM, Van Rie A, Salmaso S, Englund JA. Duration of immunity against pertussis after natural infection or vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005; 24(Suppl):S58-61; PMID:15876927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Baughman AL, Murphy TV. Increase in deaths from pertussis among young infants in the United States in the 1990s. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003; 22:628-34; PMID:12867839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisgard KM, Pascual FB, Ehresmann KR, Miller CA, Cianfrini C, Jennings CE, Rebmann CA, Gabel J, Schauer SL, Lett SM. Infant pertussis: who was the source? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23:985-9; PMID:15545851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halperin SA, Wang EE, Law B, Morris R, Dery P, Lebel M, MacDonald N, Jadavji T, Vaudry W, Scheifele D, et al.. Epidemiological features of pertussis in hospitalized patients in Canada, 1991–1997: report of the Immunization Monitoring Program–Active (IMPACT). Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:238-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkins MD, McNeil SA, Laupland K. Routine immunization of adults in Canada: Review of the epidemiology of vaccine-preventable diseases and current recommendations for primary prevention. Can J Infec Dis Med Microbiol. 2009; 20:e81-e90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halperin S. Canadian experience with implementation of an acellular pertussis vaccine booster-dose program in adolescents: Implications for the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005; 24:S141-6; PMID:15931142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikelova LK, Halperin SA, Scheifele D, Smith D, Ford-Jones E, Vaudry W, Jadavji T, Law B, Moore D; Members of the Immunization Monitoring Program, Active (IMPACT) . Predictors of death in infants hospitalized with pertussis: a case-control study of 16 pertussis deaths in Canada. J Pediatr. 2003; 143:576-81; PMID:14615725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Public Health Agency of Canada Vaccine coverage in Canadian children: Results from the 2011 Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/nics-enva/vccc-cvec-eng.php. Accessed 9February2015 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Public Health Agency of Canada Vaccine coverage amongst adult Canadians: Results from the 2012 adult National Immunization Coverage (aNIC) survey. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/nics-enva/vcac-cvac-eng.php. Accessed 13February2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams WW, Lu PJ, O'Halloran A, Bridges CB, Kim DK, Pilishvili T, Hales CM, Markowitz LE. Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination - United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:95-102; PMID:25654611 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffait M, Hanlon D, Benninghoff B, Calcoen S. Pertussis knowledge, attitude and practices among European health care professionals in charge of adult vaccination. Hum Vaccin. 2011; 2:197-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staes CJ, Gestelan P, Allison M, Mottice S, Rubin M, Shakib J, Boulton R, Wuthrich A, Carter M, Leecaster M, et al.. Urgent care providers' knowledge and attitude about public health reporting and pertussis control measures: Implications for informatics. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2009; 15:471-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasserre A, Tison C, Turbelin C, Arena C, Guiso N, Blanchon T. Pertussis prevention and diagnosis practices for adolescents and adults among a national sample of French general practitioners. Preventive Medicine. 2010; 51:90-1; PMID:20381518; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog R1, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers' intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:154; PMID:23421987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Freed GL, Freeman VA, Koch GG. The awareness to adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance. The case of pediatric vaccine recommendations. Med Care. 1996; 34:873-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayward RSA, Guyatt GH, Moore K-A, McKibbon KA, Carter AO. Canadian physicians' attitudes about and preferences regarding clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997; 156:1715-23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Registered Nurses Association of Ontario Toolkit: implementation of best practice guidelines. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/Researchers/if-res-rnao-guide.pdf; accessed February13, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eggertson L. Experts call for national immunization registry, coordinated schedules. CMAJ. 2011; 183:e143-4; PMID:21242267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1503/cmaj.109-3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Top K, Halperin B, Baxendale D, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Halperin S. Pertussis immunization in paediatric healthcare workers: Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behavior. Vaccine. 2010; 28:2169-73; PMID:20056190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark SJ, Adolphe S, Davis MM, Cowan AE, Kretsinger K. Attitudes of US obstetricians toward a combined tetanus- diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine for adults. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006:2006:87040(1-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrag SJ, Fiore AE, Gonik B Malik T, Reef S, Singleton JA, Schuchat A, Schulkin J. Vaccination and perinatal infection prevention practices among obseterician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101:704-710; PMID:12681874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis MM, Ndiaye SM, Freed GL, Kim CS, Clark SJ. Influence of insurance status and vaccine cost on physicians' administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics. 2003; 11:521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McEwen M, Farren E. Actions and beliefs related to hepatitis B and influenza immunization among registered nurses in Texas. Public Health Nurse. 2005; 22:230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huot C, Sauvageau C, Tremblay G, Dubé E, Ouakki M. Adult immunization services: steps have to be done. Vaccine. 2010; 28:1177-80; PMID:19945413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omura J, Buxton J, Kaczorowski J, Catterson J, Li J, Derban A, Hasselbeck P, Machin S, Linekin M, Morgana T, et al.. Immunization delivery in British Columbia: Perspectives of primary care physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2014; 60:e187-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivankova NV, Stick SL. Students' persistence in a distributed doctoral program in educational leadership in higher educ: a mixed methods study. Res High Edu. 2007; 48:93-135. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, Chavez G. California pertussis epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr. 2012; 161:1091-6; PMID:22819634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Pertussis epidemic–Washington, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012. July 20; 61(28):517-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koepke R, Eickhoff JC, Ayele RA, Petit AB, Schauer SL, Hopfensperger DJ, Conway JH, Davis JP. Estimating the effectiveness of tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) for preventing pertussis: evidence of rapidly waning immunity and difference in effectiveness by Tdap brand. J Infect Dis. 2014; 210:942-53; PMID:24903664; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/infdis/jiu322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amirthalingam G, Gupta S, Campbell H. Pertussis immunisation and control in England and Wales, 1957 to 2012: a historical review. Euro Surveill. 2013. September 19; 18(38). pii:20587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith T, Rotondo J, Desai S, Deehan H. Pertussis surveillance in Canada: trends to 2012. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2014; 40(3):21-30. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/14vol40/dr-rm40-03/dr-rm40-03-per-eng.php [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on immunization, April 2014 – conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemioll Rec. 2014; 89:221-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Public Health Agency of Canada Publicly-funded immunization programs in the provinces and territories of Canada: Routine and high risk schedule for adults (as of September 2014). www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/im/ptimprog-progimpt/table-3-eng.php; Accessed 8February2015 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skowronski DM, Pielak K, Remple VP, Halperin BA, Patrick DM, Naus M, McIntyre C. Adult tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis immunization: knowledge, beliefs, behavior and anticipated uptake. Vaccine. 2004. 23(3): 353-61; PMID:15530680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duclos P, Arruda H, Dessau JC, Dion R, Dupony M, Gaulin C, Grenier JL, Savard M, Trudeau G, Douville-Fradet M, et al.. Immunization survey of non-institutionalized adults–Quebec (as of May 30, 1996). Can Commun Dis Rep. 1996; 22: 177-81; PMID:8972960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warfel JM, Zimmerman LI, Merkel TJ. Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111:787-92; PMID:24277828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60(1):13-5; PMID:21228763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women–Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62:131-5; PMID:23425962 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, Kara E, Donegan K, Fry NK, Miller E, Ramsay M. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet. 2014; 384:1521-8; PMID:25037990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, Kara E, Fry NK, Ramsay M. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meade BD1, Plotkin SA, Locht C. Possible options for new pertussis vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2014; 209:S24-7; PMID:24626868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creswell JW. Education research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative approaches to research. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Pearson Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pathman DE, Konrad TR. The awareness-to-adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance. The case of pediatric vaccine recommendations. Med Care. 1996; 34:873-89; PMID:8792778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morse JM., Field PA. Qualitative research methods for health professionals 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. The Qualitative Report 2(1), 1-3. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/BackIssues/QR2-1/aronson.html. Accessed 18October2014 [Google Scholar]